Abstract

Background

Worldwide, hormonal contraceptives are among the most popular reversible contraceptives. Despite high perfect‐use effectiveness rates, typical‐use effectiveness rates for shorter‐term methods such as oral and injectable contraceptives are much lower. In large part, this disparity reflects difficulties in ongoing adherence to the contraceptive regimen and low continuation rates. Correct use of contraceptives to ensure effectiveness is vital to reducing unintended pregnancy.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of strategies aiming to improve adherence to, and continuation of, shorter‐term hormonal methods of contraception compared with usual family planning care.

Search methods

We searched to July 2018 in the following databases (without language restrictions): The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 7), PubMed via MEDLINE, POPLINE, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing strategies aimed to facilitate adherence and continuation of shorter‐term hormonal methods of contraception (such as oral contraceptives (OCs), injectable depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA or Depo‐Provera), intravaginal ring, or transdermal patch) with usual family planning care in reproductive age women seeking to avoid pregnancy.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures recommended by Cochrane. Primary outcomes were continuation or discontinuation of contraceptive method, rates of discontinuation due to adverse events (menstrual disturbances and all other adverse events), and adherence to method use as indicated by missed pills and on‐time/late injections. Pregnancy was a secondary outcome.

Main results

We included 10 RCTs involving 6242 women. Six trials provided direct in‐person counseling using either multiple counseling contacts or multiple components during one visit. Four trials provided intensive reminders of appointments or next dosing, of which two provided additional educational health information as well as reminders. All trials stated 'usual care' as the comparison.

The certainty of the evidence ranged from very low to moderate. Main limitations were risk of bias (associated with poor reporting of methodological detail, lack of blinding, and incomplete outcome data), inconsistency, indirectness, and imprecision.

Continuation of hormonal contraceptive methods

It is uncertain whether intensive counseling improves continuation of hormonal contraceptive methods compared with usual care (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.54; 2624 participants; 6 studies; I2 = 79%; very low certainty evidence). The evidence suggested: if the chance of continuation with usual care is 39%, the chance of continuation with intensive counseling would be between 41% and 50%. The overall pooled OR suggested continuation of improvement, however, when stratified by contraceptive method type, the positive results were restricted to DMPA.

It is uncertain whether reminders (+/‐ educational information) improve continuation of hormonal contraceptive methods compared with usual care (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.73; 933 participants; 2 studies; I2 = 69%; very low certainty evidence).The evidence suggested: if the chance of continuation with usual care is 52%, the chance of continuation with reminders would be between 52% and 65%.

Discontinuation due to adverse events

The evidence suggested that counseling may be associated with a decreased rate of discontinuation due to adverse events compared with usual care, with a lower rate of discontinuation due to menstrual disturbances (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.37; 350 participants; 1 study; low certainty evidence), but may make little or no difference to all other adverse events (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.47; 350 participants; 1 study; low certainty evidence). The evidence suggested: if the chance of discontinuation with usual care due to menstrual disturbances is 32%, the chance of discontinuation with intensive counseling would be between 5% and 15%; and that if the chance of discontinuation with usual care due to other adverse events is 55%, the chance of discontinuation with intensive counseling would be between 30% and 64%.

Discontinuation was not reported among trials that investigated the use of reminders (+/‐ educational information).

Adherence

Adherence was not reported among trials that investigated the use of intensive counseling.

Among trials that investigated reminders (+/‐ educational information), there was no conclusive evidence of a difference in adherence as indicated by missed pills (MD 0.80, 95% CI ‐1.22 to 2.82; 73 participants; 1 study; moderate certainty evidence) or by on‐time injections (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.29; 350 participants; 2 studies; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence). The evidence suggested: if the chance of adherence to method use as indicated by on‐time injections with usual care is 50%, the chance of adherence with method use as indicated by on‐time injections with reminders would be between 35% and 56%.

Pregnancy

There was no conclusive evidence of a difference in rates of pregnancy between intensive counseling and usual care (OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.57; 1985 participants; 3 studies; I2 = 0%, very low certainty evidence). The evidence suggested: if the chance of pregnancy with usual care is 18%, the chance of pregnancy with counseling would be between 18% and 25%.

Pregnancy was not reported among trials that investigated the use of reminders (+/‐ educational information).

Authors' conclusions

Despite the importance of this topic, studies have not been published since the last review in 2013 (nine studies) with only one study added in 2019 that neither changed the results nor improved the certainty of evidence.

Overall, the certainty of evidence for strategies to improve adherence and continuation of contraceptives is low. Intensive counseling and reminders (with or without educational information) may be associated with improved continuation of shorter‐term hormonal contraceptive methods when compared with usual family planning care. However, this should be interpreted with caution due to the low certainty of the evidence. Included trials used a variety of shorter‐term hormonal contraceptive methods which may account for the high heterogeneity. It is possible that the effectiveness of strategies for improving adherence and continuation are contingent on the contraceptive method targeted. There was limited reporting of objectively measurable outcomes (e.g. electronic monitoring device) among included studies. Future trials would benefit from standardized definitions and measurements of adherence, and consistent terminology for describing interventions and comparisons. Further research requires larger studies, follow‐up of at least one year, and improved reporting of trial methodology.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Counseling; Family Planning Services; Contraception; Contraception/methods; Contraceptive Agents, Female; Contraceptive Agents, Female/administration & dosage; Contraceptives, Oral, Hormonal; Pregnancy, Unplanned

Plain language summary

Ways to improve use of hormonal birth control

What is the question?

What is the effectiveness of methods focused on improving proper and continued use of shorter‐term hormonal methods of contraception (such as counseling techniques, or educational, motivational, or reminder messages) compared with usual family planning care (such as routine counseling or no reminder messages).

Why does it matter?

Shorter‐term hormonal types of birth control are used by many women worldwide. The most common shorter‐term hormonal methods are birth control pills and injections. These methods often do not work as well as they could. Women may have problems using the birth control as intended, such as missing some pills or returning late for their next injection. Women may also stop using a method due to bleeding changes. We looked at whether counseling or reminders helped women use these types of birth control correctly.

Incorrect use of shorter‐term hormonal types of birth control may lead to unplanned pregnancy. As many as 20% of the unplanned pregnancies in the United States of America (USA) are related to incorrect oral contraceptive use alone. There are considerable health and financial consequences for women and healthcare systems of unplanned pregnancies. Identifying ways to improve use and continuation of shorter‐term hormonal contraceptive methods is important to reduce unplanned pregnancies.

What did we find?

We searched for evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) through July 2018. This updated review now includes 10 RCTs involving 6242 women. Six studies focused on counseling and four studies involved reminders of next dose or appointments (+/‐ educational health information). All studies were conducted either in the USA or Mexico. The one study that was added neither changed the results nor improved the certainty of evidence.

Counseling may:

· improve continuation of contraception (6 studies; 2624 participants; very low certainty evidence)

· reduce discontinuation due to menstrual problems (1 study; 350 participants; low certainty evidence)

· reduce discontinuation due to adverse events (1 study; 350 participants; low certainty evidence)

· have no effect on pregnancy outcomes (3 studies, 1985 participants; very low certainty evidence)

Reminders:

· may improve continuation of contraception (2 studies, 933 participants; very low certainty evidence)

· may make little or no difference to adherence to pills (1 study, 73 participants; moderate certainty evidence)

· may make little or no difference to on‐time injections for injectable contraception (2 studies, 350 participants; low certainty evidence).

What does this mean?

There is some evidence to suggest that both intensive counseling and reminders (provided with or without educational information) may improve continuation of shorter‐term hormonal contraception compared with usual family planning care.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Intensive counseling compared to usual family planning care for improving adherence and continuation of shorter‐term hormonal methods of contraception.

| Intensive counseling compared to usual family planning care for improving adherence and continuation of shorter‐term hormonal methods of contraception | ||||||

| Patient or population: Women of reproductive age seeking to avoid pregnancy Setting: Family planning clinics in middle‐ to high‐income countries Intervention: Intensive counseling Comparison: Usual family planning care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with usual family planning care | Risk with intensive counseling | |||||

| Continuation of hormonal contraceptive method | 392 per 1,000 | 452 per 1,000 (408 to 498) | OR 1.28 (1.07 to 1.54) | 2624 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | I2 = 79% |

| Rate of discontinuation due to menstrual disturbances | 320 per 1,000 | 86 per 1,000 (49 to 148) | OR 0.20 (0.11 to 0.37) | 350 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | |

| Rate of discontinuation due to all other adverse events | 549 per 1000 | 470 per 1000 (304 to 641) | OR 0.73 (0.36 to 1.47) | 350 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | |

| Adherence to method use | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Pregnancy | 18 per 100 | 21 per 100 (18 to 25) | OR 1.24 (0.98 to 1.57) | 1985 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 4 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the median risk in the comparison group (usual care) and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Calculations were done using GRADEpro. CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for serious risk of bias as included trials had high risk of bias due to lack of blinding and/or rates of attrition > 20%

2 Downgraded one level for very serious inconsistency due to considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 79% indicating large variation between point estimates due to among‐study differences)

3 Downgraded one level for serious indirectness as differences in intervention or comparison could be sufficient to make a difference to the outcome

4 Downgraded one level for serious imprecision as 95% Confidence Interval included the null effect, and included appreciable benefit or harm

Summary of findings 2. Reminders (+/‐ educational information) compared to usual family planning care for improving adherence and continuation of shorter‐term hormonal methods of contraception.

| Reminders (+/‐ educational information) compared to usual family planning care for improving adherence and continuation of shorter‐term hormonal methods of contraception | ||||||

| Patient or population: Women of reproductive age seeking to avoid pregnancy Setting: Family planning clinics in middle‐ to high‐income countries Intervention: Reminders (+/‐ educational information) Comparison: Usual family planning care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with usual family planning care | Risk with reminders (+/‐ educational information) | |||||

| Continuation of hormonal contraceptive method | 516 per 1000 | 587 per 1000 (524 to 649) |

OR 1.33 (1.03 to 1.73) |

933 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | High unexplained heterogeneity (I2 = 69%) (unable to determine whether heterogeneity was due to differences in type of contraception, or in type of intervention) |

| Rates of discontinuation due to adverse events | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Adherence to method use as indicated by missed pills per cycle | The mean adherence was 5.8 | MD 0.8 higher (1.22 lower to 2.82 higher) | ‐ | 73 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 4 5 | |

| Adherence to method use as indicated by on‐time injections overall | 50 per 100 | 46 per 100 (35 to 56) | OR 0.84 (0.54 to 1.29) | 350 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 5 | |

| Pregnancy | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the median risk in the comparison group (usual care) and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Calculations were done using GRADEpro. CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for serious risk of bias as included trials were at high risk of bias due to lack of blinding and/or rates of attrition > 20%

2 Downgraded one level for serious inconsistency due to some heterogeneity (I2 > 50% indicating some variation between point estimates due to between‐study differences)

3 Downgraded one level for serious indirectness as differences in intervention or comparison could be sufficient to make a difference to the outcome

4 Downgraded one level for small sample size

5 Downgraded one level for serious imprecision as 95% confidence interval included the null effect, and included appreciable benefit or harm

Background

Description of the condition

Worldwide, shorter‐term hormonal contraceptives are among the most popular reversible methods of family planning. More than 166 million married or in union women report using shorter‐term hormonal contraceptives (UN 2016). In the United States of America (USA), about 16% of married or in union women (UN 2015) and 25% of all women aged 15 to 44 years (Kavanaugh 2018) report using oral contraceptives (OCs) compared with 9% globally and 7% in lower‐resource areas (UN 2015). The injectable depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA or Depo‐Provera) is used by an estimated 4.6% of women globally (UN 2015), including 4.5% of women in the USA (Daniels 2015).

Contraceptive effectiveness is vital to reducing unintended pregnancy. Effectiveness is measured with 'perfect use', when the method is used correctly and consistently as directed, and with 'typical use', which incorporates actual use of the method including inconsistent and incorrect use (Trussell 2011). The failure rate for perfect use is less than 1%; typical use has less favorable results. For example, in the USA, the first‐year failure rate for typical use of OCs is about 7%, whereas it is only 0.3% for perfect use (Sundaram 2017). The wide gap between perfect‐use rates and actual effectiveness is attributed to human factors. Several types of shorter‐term hormonal contraceptives depend on adherence to the regimen. Consistent and correct use by the woman is critical for successful use of OCs, progestin‐only pills, the transdermal patch, the vaginal ring, and, to some extent, injectable contraceptives.

Shorter‐term hormonal contraceptives in general are characterized by both poor adherence (Molloy 2012) and relatively high discontinuation rates, both of which may lead to unintended pregnancy. In developing countries, both OCs and injectables have discontinuation rates greater than 40% at 12 months (Ross 2017). Among women in the USA who had ever used OCs, Depo‐Provera, or the contraceptive patch, discontinuation rates ranged from 30% to 49% (Daniels 2013). Side effects were the most commonly reported reason for discontinuation of these methods (63%, 74%, and 45% respectively), with 31% of Depo‐Provera users also reporting that they did not like the change in their menstrual cycles (Daniels 2013). Other reasons for discontinuation included problems with access (White 2011) and confusion about pill‐taking instructions (Martinez‐Astorquiza‐Ortiz de Zarate 2013; Westhoff 2007). Nearly two‐fifths of OC users in one study missed one or more pills in the three months prior to the interview (Frost 2008) and 52% of college women in the USA reported missing their OC at least once or more per month (Molloy 2012).

OCs containing 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol had higher discontinuation rates, which were related to more irregular bleeding (Gallo 2013). For the combined monthly injectable containing depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) and estradiol cypionate, discontinuation in the first year due to all reasons was 42% (Ross 2017).

Analysis of an insurance claims database in the USA indicated that more than 35% of new OC users did not refill their prescriptions at three months (Murphy 2008). Also in the USA, prescription refills for shorter‐acting hormonal contraceptives were analyzed (Nelson 2008); by three months, only 48% to 61% of women had timely prescription refills, depending on the specific method. Furthermore, women participating in studies have overestimated their continuation rates by self‐report compared to actual pharmacy claims data (Triebwasser 2015). A randomized trial showed an OC discontinuation rate of 51% for adolescents provided with seven pill packs and 35% for those given three packs (White 2011). In Brazil, 45% of pill users discontinued in the first 12 months, including 12% due to side effects (Leite 2007). For DMPA, multinational data indicate 50% discontinuation for DMPA at one year (NICE 2005). In Brazil, the discontinuation rate for injectables was 64% for the first 12 months, with 27% related to side effects (Leite 2007). About 15% of treatment cycles while using the vaginal ring were not consistent with the dosing regimen (Dieben 2002). The women had ring‐free time periods that were longer, shorter, or more frequent than recommended (Dieben 2002).

Description of the intervention

An important component of family planning services is providing the client with objective and frank information about contraceptive methods. The quality of family planning services may affect contraceptive acceptability and continuation (Dehlendorf 2014; RamaRao 2003). Quality of services is defined by provider skills, quality of information provided, client‐provider interactions, and continuity of care (ARHP 2004; Blanc 2002; Jain 1989). Various strategies are aimed at improving knowledge gaps about correct contraceptive use (Hall 2014; Little 1998) and typical side effects (Blanc 2002) to improve the woman's understanding of the method and the consequences of imperfect use. Such methods may include counseling or the provision of reminder messages. Counseling may be delivered directly in person, online, or via the telephone, either by medical or nursing staff, or peers, in individual or group settings. The counseling strategies may consist of a single component or multiple components delivered in a single session, or in multiple sessions at various time points. Reminder messages may be sent daily to remind women using OCs to take their pill, while women using the DMPA injection may be sent reminders when their next injection is due.

How the intervention might work

Within the first year of starting a method, 7% to 27% of women stop using contraception for reasons that could be addressed during family planning counseling, including side effects and health concerns related to the contraceptive method (Belete 2018; Blanc 2002; Dehlendorf 2013; Frost 2012). A Canadian survey indicated that women who had counseling also had more accurate responses on the majority of questions about OC use, benefits, and side effects (Gaudet 2004). Women who do not have an established routine for taking their OCs have been found to be at greater risk of missing pills (Martinez‐Astorquiza‐Ortiz de Zarate 2013; Rosenberg 1998). Sending reminder messages may improve adherence by helping to establish such a routine (Hall 2013; Tomaszewski 2017). An individualized approach to family planning services, including counseling about correct use and providing reminders, would focus on individual needs assessment and interpersonal relations between the consumer and the provider, possibly reducing errors and discontinuation rates (ARHP 2004; Rudy 2003).

Why it is important to do this review

Unintended pregnancies related to OC use alone are estimated to account for 20% of the 3.5 million annual unintended pregnancies in the USA (Rosenberg 1995; Rosenberg 1999; Sonfield 2014). Unintended pregnancy has substantial health and financial implications for women (Bhutta 2014; Canning 2012) and healthcare systems (Ahmed 2012; Rosenberg 1995). Effective strategies that promote adherence and continuation of shorter‐term hormonal contraceptives are difficult to identify, but are critical to improve contraceptive use and prevent unintended pregnancy. This review is an update to Halpern 2013, Cochrane reviews are of most use in practice when the literature included is up to date. This review aimed to identify effective strategies to help women continue the use of shorter‐term hormonal contraceptives and prevent unwanted pregnancies.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of strategies aiming to improve adherence to, and continuation of, shorter‐term hormonal methods of contraception compared with usual family planning care.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included published or unpublished randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in full‐text or abstract format. Cluster‐randomized trials were eligible for inclusion. Quasi‐experimental and cross‐over trials were not eligible for inclusion. Conference abstracts were handled in the same way as full‐text publications.

Types of participants

Women of reproductive age seeking shorter‐term hormonal contraception (OCs, injectable depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA or Depo‐Provera), intravaginal ring, or transdermal patch) to avoid pregnancy. Trials that recruited women using long‐acting reversible contraceptives such as intrauterine devices and hormonal implants were not eligible.

Types of interventions

We included RCTs of strategies (as defined by individual trials) aiming to facilitate adherence and continuation of shorter‐term hormonal methods of contraception compared with usual family planning care (as defined by individual trials).

Strategies could include:

motivational or educational telephone calls;

structured, peer or multi‐component counseling (guidance or assistance);

intensive reminders of follow‐up appointments or next dosing;

multimedia, including computer‐based contraceptive assessment modules and video materials; and

a combination of these strategies.

Trials that investigated the effect of counseling on initiation or uptake (rather than adherence and continuation) of various methods of hormonal contraception were not eligible for inclusion.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Continuation or discontinuation of contraceptive method (as defined by individual trials).

Rates of discontinuation due to adverse events ‐ overall rate, and rate for specific adverse events as defined by individual trials.

Adherence to method use, as indicated by missed pills (among pill users) and on‐time/late injections (among injectable users), consistent patch and ring use, or as defined by individual trials.

Secondary outcomes

Pregnancy (as defined by individual trials).

Search methods for identification of studies

We conducted an updated search of the Halpern 2013 Cochrane Review (September 2013 to July 2018) for all published and unpublished RCTs of strategies to improve adherence and continuation of hormonal contraceptive use, without language restrictions.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases for relevant trials:

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (searched September 2013 to July 2018; Issue 7);

PubMed via MEDLINE (searched September 2013 to July 2018);

POPLINE (https://www.popline.org/advancedsearch) (searched September 2013 to July 2018);

Web of Science (searched September 2013 to July 2018); and

International trial registers for ongoing trials:

'ClinicalTrials.gov', a service of the US National Institutes of Health (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home) (searched September 2013 to July 2018); and

'The World Health Organization International Trials Registry Platform search portal' (www.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx) (searched September 2013 to July 2018).

Search strategies are available in Appendix 1.

Search strategies for previous versions of this review are available in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We examined the reference lists of identified articles for additional trials. For the initial review, experts in the field were contacted to seek trials that may have been missed.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

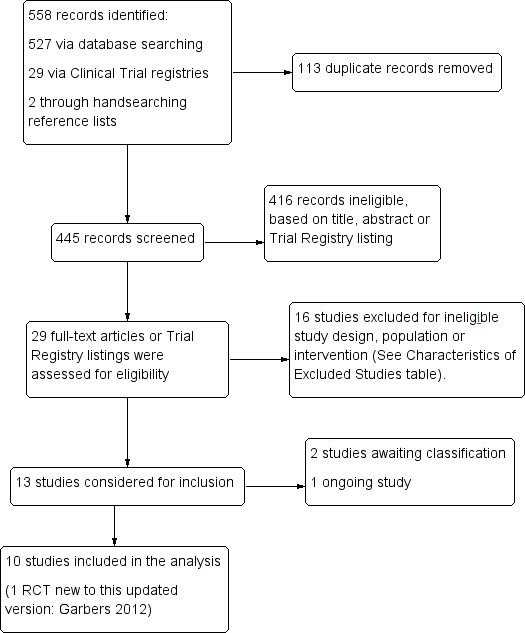

One review author initially screened titles and abstracts retrieved by the search against eligibility criteria and retrieved full texts of potentially eligible trials (NM). Two review authors independently examined these full text articles for compliance with the inclusion criteria (NM and TWG). Correspondence with trial investigators was undertaken as necessary to clarify study eligibility. The selection process is documented in the study flow chart (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram (2019)

Data extraction and management

Two authors independently extracted data from eligible studies using a data extraction form designed for this review (NM and TWG) and discrepancies were resolved by discussion or by involving a third person (MC). Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked for accuracy. Data extracted included study characteristics and outcome data. We have included this information and presented it in the Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables. Where trials had multiple publications, the authors collated multiple reports of the same under a single study identification with multiple references.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (NM and TWG) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included trials using the Cochrane 'risk of bias' assessment tool and using criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion or by involving a third person (MC).

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study, we described the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); and

unclear risk of bias

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study, we described the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomization; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth); and

unclear risk of bias.

(3) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

For each included study, we described the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at high risk of bias if participants and personnel were not blinded, or where such lack of blinding would be likely to affect the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high, or unclear risk of bias for participants; and

low, high, or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(4) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

For each included study, we described the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at high risk of bias if outcome assessors were not blinded, or where such lack of blinding would be likely to affect the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high, or unclear risk of bias.

(5) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. loss to follow‐up of greater than 20%, numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomization); and

unclear risk of bias

(6) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

For each included study, we described how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all of the study’s prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported); and

unclear risk of bias.

(7) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by 1) to 6) above)

For each included study, we described any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias, that is, self‐reported outcomes, or data unavailable on an objective outcome.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias; and

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we used the numbers of events in the intervention and control groups for each trial to calculate the Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, if all trials reported exactly the same outcomes, we calculated the mean difference (MD) between groups. If similar outcomes were reported on different scales, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD).

Unit of analysis issues

The primary analysis was per woman randomized.

Where trials with multiple intervention arms were included, we avoided 'double counting' of participants by combining groups to create a single pairwise comparison, if possible. Where this was not possible, we split the 'shared' group into two or more groups with smaller sample size and included two or more (reasonably independent) comparisons.

Had we identified any cluster‐randomized trials, we planned to include them in the analyses along with individually‐randomized trials, with the appropriate cluster design considerations in the analysis; however, none was identified.

Dealing with missing data

In cases where data were missing, we wrote to the trial investigators to request additional information. In addition, and where possible, we performed analyses on outcomes on an intention‐to‐treat basis, including all the randomized participants in the groups to which they were randomized. In cases of missing data, analysis was based on the data available.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included trials were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a clinically meaningful summary. We assessed statistical heterogeneity by the measure of the I² following guidance from the Cochrane Handbook:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity*;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity*; and

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity*.

*The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on (i) magnitude and direction of effects and (ii) strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from the chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2) (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulty of detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, we aimed to minimise their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible trials without language or publication restrictions, and by being alert to duplication of data. If, in future updates, more than 10 trials are included, we will use a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small study effects (a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies).

Data synthesis

Statistical analysis of the data was carried out using Review Manager software (RevMan 2014).

Where the intervention and control groups were sufficiently similar, the data were pooled using a fixed‐effect Mantel‐Haenszel model and note made on the presence of significant heterogeneity where it occurred. Where studies utilised similar interventions, we included them in the same analysis, but stratified the analysis according to their types of delivery or utilisation of additional components, and we did not pool the stratified analysis if there was unexplained heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If there was evidence of substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), we explored methodological and clinical differences between the trials that might account for the heterogeneity. For the first primary outcome (continuation of contraceptive method), we conducted separate subgroup analyses in order to determine any differences in effect within these groups:

intervention components (multiple counseling contacts versus one‐off multi‐component counseling; reminders with educational information versus reminders without educational information); and

type of contraception (OC or injectable).

We also planned to conduct subgroup analysis by randomization unit, but as no cluster‐randomized trials were identified in this update, subgroup analysis of individually‐randomized versus cluster‐randomized trials was not undertaken. If, in future updates of this review, cluster‐randomized trials are identified, we will undertake this subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

We initially planned to explore the effect of limiting analysis to trials at low risk of bias, but, given the small number of trials, we did not do so.

Overall certainty of the body of evidence: 'Summary of findings' tables

We prepared 'Summary of Findings' tables, using GRADEpro GDT software (GRADE 2013) and Cochrane methods (EPOC 2018; Higgins 2011). These tables evaluated the overall certainty of the body of evidence for the main review outcomes (continuation of contraceptive method, rates of discontinuation due to adverse events, adherence to method use and pregnancy) for the main review comparisons (intensive counseling versus usual family planning care, and reminders (+/‐ educational information) versus usual family planning care) using GRADE criteria (study limitations (i.e. risk of bias), consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias). Judgements about evidence certainty (high, moderate, low, or very low) were made by two review authors working independently, with disagreements resolved by discussion. Judgements were justified, documented, and incorporated into reporting of results for each outcome.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

For this 2018 update, the search identified 556 references (Figure 1). An additional two items were identified from other sources such as reference lists, for a total of 558 records. We removed 113 duplicates electronically or by hand, leaving 445 de‐duplicated references that underwent initial screening for eligibility, 416 of which were judged to be ineligible. We retrieved 29 full‐text trials or trial registry listings for appraisal and 19 trials or registry listings were excluded.

Included studies

This update includes a total of 10 RCTs (17 publications) (Berenson 2012; Canto De Cetina 2001; Castaño 2012; Garbers 2012; Gilliam 2004; Hou 2010; Jay 1984; Keder 1998; Kirby 2010; Trent 2015). Only one new RCT (n = 2448) was added to this update (Garbers 2012). The nine other RCTs were included in the 2013 review publication; Trent 2015 was included as a secondary article for a previously included abstract. See Figure 1 for details of the screening and selection process.

Study Design

All of the included trials used parallel group design in a RCT.

Sample sizes

A total of 6242 women are involved in the 10 included trials. Sample sizes ranged from 33 women (Gilliam 2004), to 2448 women (Garbers 2012). Six trials had sample sizes of fewer than 500 (Canto De Cetina 2001 (n = 350); Gilliam 2004 (n = 33); Hou 2010 (n = 82); Jay 1984 (n = 57); Keder 1998 (n = 250); Trent 2015 (n = 100)).

Setting

Nine trials were conducted in the USA (Berenson 2012; Castaño 2012; Garbers 2012; Gilliam 2004; Hou 2010; Jay 1984; Keder 1998; Kirby 2010; Trent 2015), and one in Mexico (Canto De Cetina 2001). Two trials were conducted in the 1990s (Gilliam 2004; Keder 1998), five trials were conducted in the 2000s (Berenson 2012; Castaño 2012; Garbers 2012; Hou 2010; Kirby 2010) and one trial was conducted after 2010 (Trent 2015). Two trials did not provide details of their timeframe (Canto De Cetina 2001; Jay 1984).

One was multi‐site (Berenson 2012), and the others were single‐site (Canto De Cetina 2001; Castaño 2012; Garbers 2012; Gilliam 2004; Hou 2010; Jay 1984; Keder 1998; Kirby 2010; Trent 2015). Most were set in urban clinics or family planning centers.

Participants

All trials recruited women of reproductive age seeking hormonal contraceptives to avoid pregnancy, and with no medical contraindication to hormonal contraceptive use. Six trials focused on adolescents or young women up to 25 years of age (Berenson 2012; Castaño 2012; Gilliam 2004; Jay 1984; Kirby 2010; Trent 2015). One trial included women up to the age of 35 years (Canto De Cetina 2001). Three trials did not specify age limits as part of their inclusion criteria (Garbers 2012; Hou 2010; Keder 1998).

Five trials focused on the use of OCs (Berenson 2012; Castaño 2012; Gilliam 2004; Hou 2010; Jay 1984), and three trials were conducted among women using DMPA injection (Canto De Cetina 2001; Keder 1998; Trent 2015). Two trials (Garbers 2012; Kirby 2010) included any form of shorter‐term hormonal contraceptive (OCs, DMPA, transdermal patch). Garbers 2012 also included women who used long‐acting reversible contraceptives such as intrauterine devices, but the investigator provided disaggregated data for continuation at four months to allow inclusion of data specifically on shorter‐acting hormonal methods.

Gilliam 2004 was conducted in young pregnant women who intended to use oral contraceptives postpartum.

Interventions and comparisons

Interventions and comparisons varied as seen below.

Counseling

Six trials provided direct in‐person counseling (Berenson 2012; Canto De Cetina 2001; Garbers 2012; Gilliam 2004; Jay 1984; Kirby 2010). Four trials had multiple counseling contacts for each group (Berenson 2012; Canto De Cetina 2001; Jay 1984; Kirby 2010), and three trials used multiple components during one visit (Berenson 2012; Garbers 2012; Gilliam 2004). Berenson 2012 was a three‐arm trial that consisted of two intervention groups ‐ one group had a one‐off extra 45‐minute counseling session, and one had the extra 45‐minute counseling session plus follow‐up calls from a contraceptive counselor for six months. Garbers 2012 used an audio computer‐assisted self‐interview (ACASI) module (lengthier for the intervention groups than for the control group) to help women select a method. Intervention group women in this study then received additional tailored or generic materials based upon their randomized group assignment (Garbers 2012).

The interventions in these trials were compared to 'usual' or 'routine' family planning counseling as defined in the individual trials.

Messages / reminders

Four trials provided intensive reminders of appointments or next dosing (Castaño 2012; Hou 2010; Keder 1998; Trent 2015), of which two provided educational health information as well as reminders (Castaño 2012; Trent 2015). The older study used mail and telephone (Keder 1998). The three newer trials sent text messages to cell phones (Castaño 2012; Hou 2010; Trent 2015). The comparison in these trials was 'usual care' as defined in the individual trials, or no reminders.

Outcomes

Seven trials reported on continuation of contraceptive method (Berenson 2012; Canto De Cetina 2001; Castaño 2012; Garbers 2012; Gilliam 2004; Jay 1984; Kirby 2010), and two trials reported on discontinuation (Canto De Cetina 2001; Keder 1998).

Eight trials assessed adherence: consistent injectable use (Keder 1998; Trent 2015); non‐compliance (Jay 1984); switched contraceptives (Gilliam 2004); missed pills (Castaño 2012; Hou 2010); consistent OC use (Berenson 2012; Garbers 2012); or consistent patch and ring use (Garbers 2012). One of the trials with injectable users asked if the women had received their second injection (Garbers 2012). Two trials used objective measures to assess pill use: Hou 2010 used an electronic monitoring device, and Jay 1984 used a biomarker (urinary fluorescence).

Three trials had pregnancy as an outcome (Berenson 2012; Gilliam 2004; Kirby 2010). Gilliam 2004 obtained pregnancy data for a limited number of participants, and Kirby 2010 presented the pregnancy rate as a percentage rather than raw data.

Follow‐up duration was three months (Hou 2010), four months (Garbers 2012; Jay 1984), six months (Castaño 2012), nine months (Trent 2015), and twelve months (Berenson 2012; Canto De Cetina 2001; Gilliam 2004; Keder 1998; Kirby 2010).

Declarations of interest in the trial reports

Seven trials did not include a declaration of interests in their manuscript (Berenson 2012; Canto De Cetina 2001; Gilliam 2004; Jay 1984; Keder 1998; Kirby 2010; Trent 2015). Three trials included declarations of interest, which included authors serving as Advisory Board members for pharmaceutical companies (Castaño 2012), authors receiving honoraria and/or payment of travel expenses from pharmaceutical companies (Hou 2010), or an author being entitled to royalties derived from a product used in the research described in the manuscript that could affect the personal financial status (Garbers 2012). This was reviewed and approved by the author's employer in accordance with its conflict of interest policies (Garbers 2012).

Sources of trial funding

Five trials reported funding from private foundations (Castaño 2012; Garbers 2012; Hou 2010; Kirby 2010; Trent 2015). Two trials reported funding from government agencies or departments (Berenson 2012; Jay 1984). One trial reported receiving funding from a combination of Professional Society and pharmaceutical company (Gilliam 2004). Two trials did not report their source of funding (Canto De Cetina 2001; Keder 1998).

Excluded studies

Nineteen trials were excluded. Four trials were excluded for non‐randomized design (IRCT201205289463N2 2012; Madden 2013; Metson 1991; Schunmann 2006). Six trials did not use an intervention or comparison included in this review (Bender 2004; Burnhill 1985; Gilliam 2010; Schwarz 2008; Torres 2014; Zhu 2009). Six trials were conducted with participants using ineligible contraceptive methods such as non‐hormonal or long‐acting reversible contraceptives (Andolsek 1982; Carneiro 2011; Langston 2010; Modesto 2014; Roye 2007; Schwandt 2013). Details are provided in Characteristics of excluded studies.

We listed two trials in Studies awaiting classification (Chuang 2015; Smith 2015), and a pilot RCT in Characteristics of ongoing studies (Royer 2016)

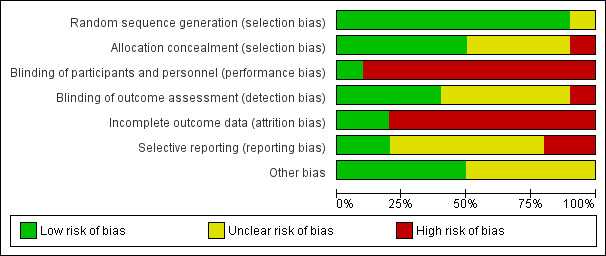

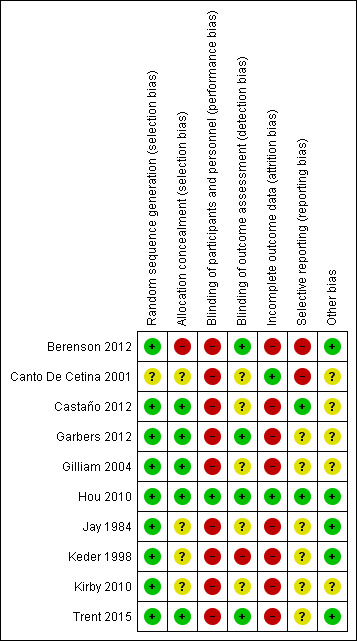

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 2 summarizes our assessments of risk of bias for the overall review; Figure 3 provides our assessment for each study.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Nine trials described the method used to generate the random sequence in sufficient detail to enable a judgement of low risk of bias. These trials reported using a computer‐generated randomization sequence (Berenson 2012; Garbers 2012; Gilliam 2004; Hou 2010; Jay 1984; Keder 1998; Trent 2015), or random number table (Castaño 2012; Kirby 2010). One trial did not provide any information on method used to generate the random sequence and was assessed as having an unclear risk of bias (Canto De Cetina 2001).

Allocation concealment

Five trials provided sufficient detail to enable an assessment of low risk of bias. These trials reported using opaque sealed envelopes (Castaño 2012; Gilliam 2004; Hou 2010; Trent 2015) or computerized allocation (Garbers 2012) to conceal the allocation to study groups.

Four trials did not provide any information on the method used to conceal allocation and were assessed as having an unclear risk of bias for this domain (Canto De Cetina 2001; Jay 1984; Keder 1998; Kirby 2010).

One trial did not conceal group allocation from the study personnel and this was assessed as having a high risk of bias (Berenson 2012).

Blinding

Performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel)

Hou 2010 was the only trial to be assessed as having a low risk of bias for this domain, as the investigator was blinded to group allocation until the primary analysis was complete.

Three trials reported blinding of the research team members, but not of the intervention providers or participants, and these trials were assessed as having a high risk of bias (Gilliam 2004; Kirby 2010; Trent 2015).

The remaining trials did not provide any details of blinding of trial participants or personnel but this was considered unlikely due to the nature of the interventions. These trials were assessed as having a high risk of bias (Berenson 2012; Canto De Cetina 2001; Castaño 2012; Garbers 2012; Jay 1984; Keder 1998).

Detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment)

Four trials were assessed as having a low risk of bias for this domain. Berenson 2012 and Garbers 2012 stated they had blinding of outcome assessors, and Hou 2010 and Trent 2015 used electronic monitoring or tracking to measure the primary outcome.

Two trials were assessed as having an unclear risk of bias despite reporting some blinding of outcome assessment. Jay 1984 reported that the independent observers who evaluated urine samples for fluorescence were blinded to group allocation, but also used a self‐reported Guttman Scale to measure pregnancy and pill count for non‐adherence. Similarly, Kirby 2010 reported that the outcome assessor was blinded to group allocation throughout the trial, except for final follow‐up which included questions about the intervention.

Three trials were assessed as having an unclear risk of detection bias due to insufficient detail on blinding of outcome assessment (Canto De Cetina 2001; Castaño 2012; Gilliam 2004).

One trial was assessed as having a high risk of bias as the outcome assessor was aware of group allocation throughout the trial (Keder 1998).

Incomplete outcome data

Two trials were assessed as having a low risk of attrition bias due to losses to follow‐up of less than 20% (Canto De Cetina 2001; Hou 2010).

The remaining eight trials had losses of 20% or more and were assessed as having a high risk of bias for this domain:

Berenson 2012 lost 44%.

Castaño 2012 lost 28% from the intervention group and 30% of the control group.

In Garbers 2012, loss in the baseline analysis due to missing data was 23% in the I+T group, 20% in the I+G group, and 9% in the control group; loss or lack of information among women selected for 4‐month follow‐up was 18% in both intervention groups, and 19% in the control group.

Gilliam 2004 lost 24% overall (11% in the intervention group and 40% in the control group).

Jay 1984 reported losses of 42% and 23% in the nurse‐counselor and peer‐counselor groups, respectively, for 33% overall.

In Keder 1998, loss to follow‐up was 36% overall (34% in the reminder group and 38% in the no‐reminder group).

In Kirby 2010, overall loss was 25%.

In Trent 2015, 31% did not complete three cycles.

Selective reporting

Two trials were assessed as having a low risk of reporting bias. Castaño 2012 and Hou 2010 had trial protocols available (as trial registrations on ClinicalTrials.gov) and all prespecified outcomes were reported in the published manuscripts.

Six trials were assessed as having an unclear risk of bias for this domain. Although these trials did not have a protocol available, all outcomes prespecified in the published manuscript were reported on (Garbers 2012; Gilliam 2004; Jay 1984; Keder 1998; Kirby 2010; Trent 2015).

One trial did not report outcomes in the published manuscript that were prespecified in the protocol (Berenson 2012), and one trial reported on outcomes that had not been prespecified (Canto De Cetina 2001). These were assessed as having a high risk of bias for this domain.

Other potential sources of bias

Five trials were assessed as having a low risk of bias from other sources (Berenson 2012; Hou 2010; Jay 1984; Keder 1998; Trent 2015).

Five trials did not have objective outcome measures and were assessed as having an unclear risk of bias for this domain (Canto De Cetina 2001; Castaño 2012; Garbers 2012; Gilliam 2004; Kirby 2010).

Effects of interventions

1.0 Intensive counseling versus usual family planning care

Six studies made this comparison. Three (Canto De Cetina 2001; Jay 1984; Kirby 2010) compared multiple counseling contacts versus usual care, two (Garbers 2012; Gilliam 2004) compared multi‐component counseling versus usual care, and one made both comparisons (Berenson 2012).

Primary outcomes

1.1 Continuation of hormonal contraceptive method

Six trials reported on the outcome of continuation of hormonal contraceptive method (Berenson 2012; Canto De Cetina 2001; Garbers 2012; Gilliam 2004; Jay 1984; Kirby 2010). It is uncertain whether intensive counseling improves the continuation of contraceptive method compared to usual care (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.54; trials = 6; participants = 2624; I2 = 79%; duration of follow‐up = 3 to 18 months; Analysis 1.1) because the certainty of this evidence was very low. The evidence suggests that if the chance of continuation with usual care is 39%, the chance of continuation with intensive counseling would be between 41% and 50%. The heterogeneity was due to the different types of contraception used. When the two studies of women using depot‐medroxyprogesterone acetate (Canto De Cetina 2001; Garbers 2012) were excluded from the analysis, the heterogeneity reduced to nil (I2 = 0%) and the effect estimate no longer showed a difference between the groups.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intensive counseling versus usual family planning care, Outcome 1 Continuation of hormonal contraceptive method.

Subgroup analysis by type of intervention (Analysis 1.1.1 and Analysis 1.1.2):

The test for subgroup differences showed no evidence of a difference between the two different types of interventions (Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.80, df = 1; P = 0.37; I² = 0%).

The findings in the separate groups were as follows:

Multiple counseling contacts

There was evidence of increased rates of continuation of hormonal contraceptives among women undergoing multiple counseling contacts compared with women having usual care (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.66; trials = 4; participants = 1790; I2 = 87%; duration of follow‐up = 3 to 18 months; Analysis 1.1.1) (Berenson 2012; Canto De Cetina 2001; Jay 1984; Kirby 2010).

One‐off multi‐component counseling

There was no evidence of a difference in continuation of hormonal contraceptives between women undergoing one‐off multi‐component counseling compared with women having usual care (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.60; trials = 3; participants = 834; I2 = 56%; duration of follow‐up = 3 to 12 months; Analysis 1.1.2) (Berenson 2012; Garbers 2012; Gilliam 2004).

Subgroup analysis by type of contraceptive (Analysis 2.1):

The test for subgroup differences showed a significant difference between the subgroups (Test for subgroup differences Analysis 2.1: Chi² = 20.65, df = 1; P = 0.00001; I2 = 95.2%). The findings in the separate groups were as follows:

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subgroup analysis by contraceptive: intensive counseling versus usual family planning care, Outcome 1 Continuation of hormonal contraceptive method.

Women using depot‐medroxyprogesterone acetate

Counseling was associated with increased continuation of hormonal contraceptive method compared with usual care in women using depot‐medroxyprogesterone acetate (OR 3.78, 95% CI 2.34 to 6.10; trials = 2; participants = 374; I2 = 0%; duration of follow‐up = 3 to 4 months; Analysis 2.1.1) (Canto De Cetina 2001; Garbers 2012).

Women using oral contraceptives

There was no evidence of a difference in continuation of hormonal contraceptives between counseling and usual care in women using oral contraceptives (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.38; trials = 4; participants = 1344; I2 = 2%; duration of follow‐up = 3 to 12 months; Analysis 2.1.2) (Berenson 2012; Garbers 2012; Gilliam 2004; Jay 1984).

1.2 Rate of discontinuation of contraceptive method due to adverse events

One study reported this outcome (Canto De Cetina 2001) (Analysis 1.2). Adverse events reported included weight gain, vomiting, dizziness, depression, and loss of libido. Menstrual disturbances reported included amenorrhea, irregular bleeding, and heavy bleeding.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intensive counseling versus usual family planning care, Outcome 2 Rate of discontinuation of contraceptive method due to adverse events.

Discontinuation due to menstrual disturbances

Counseling may be associated with a lower rate of discontinuation due to menstrual disturbances (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.37; trials = 1; participants = 350; I2 = 0%; duration of follow‐up = 12 months; low certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2.1) (Canto De Cetina 2001). The evidence suggests that if the chance of discontinuation with usual care is 32%, the chance of discontinuation with intensive counseling would be between 5% and 15%.

Discontinuation due to all other adverse events

There was little or no evidence of a difference in the rate of discontinuation due to all other adverse events (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.47; trials = 1; participants = 350; I2 = 0%; duration of follow‐up = 12 months; low certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2.2) (Canto De Cetina 2001). The evidence suggests that if the chance of discontinuation with usual care is 55%, the chance of discontinuation with intensive counseling would be between 30% and 64%.

1.3 Adherence to method use

No trials included in this comparison reported adherence to method use as an outcome.

Secondary outcome

1.4 Pregnancy

There was no conclusive evidence of a difference in rates of pregnancy between counseling and usual care (OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.57; trials = 3; participants = 1985; I2 = 0%, very low certainty evidence; duration of follow‐up = 3 to 18 months; Analysis 1.3) (Berenson 2012; Gilliam 2004; Kirby 2010). The evidence suggests that if the chance of pregnancy with usual care is 18%, the chance of pregnancy with intensive counseling would be between 18% and 25%.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intensive counseling versus usual family planning care, Outcome 3 Pregnancy.

2.0 Reminders (+/‐ educational information) versus usual family planning care

Four studies made this comparison. They compared reminders alone (Keder 1998, Hou 2010) and reminders with educational information (Castaño 2012,Trent 2015 ) versus usual care.

Primary outcomes

2.1 Continuation of hormonal contraceptive method

Two trials (Castaño 2012; Keder 1998) reported on the outcome of continuation of hormonal contraceptive method (Analysis 3.1). Keder 1998 used depot‐medroxyprogesterone acetate injection and Castaño 2012 used oral contraceptives. There was no conclusive evidence of a difference in the continuation of hormonal contraceptive methods between usual care and reminders (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.73; trials = 2; participants = 933; I2 = 69%, very low certainty evidence). The evidence suggests that if the chance of continuation of hormonal contraceptive methods with usual care is 52%, the chance of continuation with reminders would be between 52% and 65%.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Reminders (+/‐ educational information) versus usual family planning care, Outcome 1 Continuation of hormonal contraceptive method.

Subgroup analysis by type of intervention (Analysis 3.1)

The test for subgroup differences showed a significant difference between the two subgroups (Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 3.21, df = 1; P = 0.07; I² = 68.8%) (Castaño 2012; Keder 1998).

Reminders without educational information (Analysis 3.1.1)

There was no evidence of a difference in continuation of hormonal contraceptive method in women receiving reminders without educational information compared with usual care (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.49; trials = 1; participants = 250; I2 = 0%; duration of follow‐up = 12 months; Analysis 3.1.1). This trial was conducted in women using depot‐medroxyprogesterone acetate injection (Keder 1998).

Reminders with educational information (Analysis 3.1.2)

Reminders with educational information were associated with increased continuation of hormonal contraceptive method compared with usual care (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.14 to 2.10; trials = 1; participants = 683; I2 = 0%; duration of follow‐up = 6 months; Analysis 3.1.2). This trial was conducted in women using oral contraceptives (Castaño 2012).

Further subgroup analysis was not possible as there was only one study in each group.

2.2 Discontinuation due to adverse events

No trials included in this comparison reported discontinuation due to adverse events as an outcome.

2.3 Adherence to method use

Adherence to method use as indicated by missed pills (Analysis 3.2)

There was no clear evidence of a difference in adherence to method use as indicated by missed pills in women receiving reminders (+/‐ educational information) compared with usual care (MD 0.80, 95% CI ‐1.22 to 2.82; trials = 1; participants = 73; I2 = not applicable, moderate certainty evidence; duration of follow‐up = 3 months; Analysis 3.2) (Hou 2010).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Reminders (+/‐ educational information) versus usual family planning care, Outcome 2 Adherence to method use as indicated by missed pills.

Adherence to method use as indicated by on‐time injections overall (Analysis 3.3)

There was no clear evidence of a difference in adherence to method use as indicated by on‐time injections in women receiving reminders (+/‐ educational information) compared with usual care (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.29; trials = 2; participants = 350; I2 = 0%, low certainty evidence; duration of follow‐up = 9 to 12 months; Analysis 3.3) (Keder 1998; Trent 2015).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Reminders (+/‐ educational information) versus usual family planning care, Outcome 3 Adherence to method use as indicated by on‐time injections overall.

Secondary outcome

2.4 Pregnancy

Pregnancy was not reported as an outcome in any of the trials included in this comparison.

Assessment of publication bias

We could not construct a funnel plot to test for publication bias as there were insufficient studies for any one comparison.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In the five years since the last review, no new studies have been published. The one study that was added to this review was published during the prior review search period.

Overall, the certainty of evidence for strategies to improve adherence and continuation of contraceptives is low. When analysis was performed by type of contraceptive to explore heterogeneity, it appeared that counseling may only be associated with increased continuation among women using DMPA. Counseling was also associated with a reduction in discontinuation of contraceptive method due to adverse events when compared with usual family planning care. This suggests some benefit of counseling about contraceptive side effects, which can dominate some women's decisions about family planning methods. Enhanced counseling and reminders may have some effect on contraceptive continuation, and may change the reasons women stop using contraception.

There was low certainty evidence to suggest that reminders provided along with educational information may be associated with increased continuation of hormonal contraceptive method in women using oral contraceptives, but not in women using depot‐medroxyprogesterone acetate injection.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This review has focused on strategies to improve adherence and continuation of shorter‐term hormonal contraceptive methods that included counseling and reminders, the type and intensity of which varied across the studies, compared to usual family planning care. The evidence for use of these strategies should be interpreted with caution due to the very low to moderate certainty, and considering the context of the needs of individual women.

External validity may be limited in this review, given the small number of studies and their preponderance in the USA. The individual study findings may be specific to the setting. While all were initiated within clinics, many provided outreach during the follow‐up period by telephone or text message. The content and process of counseling or reminder interventions may be appropriate for a local population or clinic and not relevant universally, so effects may differ across groups and sites.

Quality of the evidence

Using GRADE methodology, we assessed the certainty of evidence across all 10 RCTs for specific review outcomes (EPOC 2018; Higgins 2011). The overall certainty of the evidence for outcomes related to intensive counseling compared to usual family planning care ranged from very low certainty (we have very little confidence in the effect estimate) to low certainty of evidence (our confidence in the effect estimate is limited). The overall certainty of evidence for outcomes related to reminders compared to usual family planning care ranged from very low certainty (we have very little confidence in the effect estimate) to moderate certainty (we have moderate confidence in the effect estimate) (Table 1; Table 2). Main limitations were risk of bias (associated with poor reporting of methodological detail, lack of blinding and incomplete outcome data), inconsistency, indirectness and imprecision.

Potential biases in the review process

We believe that we have made every effort to minimise bias in the review process. A systematic search of the literature was conducted for RCTs. This search was not restricted by language or date of publication. When required, we attempted to contact authors of primary studies to obtain additional methodological and/or outcome data. Cochrane methods of searching, appraising, data extraction, and analysis were adhered to throughout the review process.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Other Cochrane systematic reviews have examined interventions for enhancing general self‐administered medication adherence (Nieuwlaat 2014), interventions delivered by mobile phone specific to improving contraceptive use (Smith 2015a), and educational interventions aimed at preventing unintended pregnancy among specific populations such as adolescents (Oringanje 2016).

Other reviews currently underway plan to explore the impact of social networking site‐based interventions (Jawad 2017), or structured versus routine family planning counseling (Farrokh‐Eslamlou 2014) on contraception adherence. McQueston 2013 also reviewed interventions to reduce adolescent childbearing in low‐ and middle‐income countries, but those interventions were not comparable to those included in the current Cochrane review. Zapata 2015 reviewed five studies that examined reminder systems for OC users and for DMPA users, two of which are included in the current Cochrane review. They concluded that “…the highest quality evidence yielded null findings and did not support the effectiveness of such interventions”.

Research in this area remains limited. Methodological limitations are common among trials included in systematic reviews hampering the interpretation of the evidence and the ability to draw firm conclusions (Nieuwlaat 2014; Oringanje 2016). One review of 53 studies including 105,368 participants found that a combination of interventions was associated with a reduction in unintended pregnancy among adolescents, despite limited effect on biological measures (Oringanje 2016). There is also limited evidence to suggest that interventions delivered by mobile phone may be associated with improved contraception adherence when combined with counselor support from a review of five studies, but concluded that interventions delivered by mobile phone should only be considered as a single component of broader healthcare delivery (Smith 2015).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is some evidence to suggest that both intensive counseling and reminders (provided with or without educational information) may be associated with improved continuation of shorter‐term hormonal contraceptive methods when compared with usual family planning care. However, this should be interpreted with caution due to the very low certainty of the evidence. The included trials investigated interventions in women using a variety of different shorter‐term hormonal contraceptive methods and this may account for the high heterogeneity. It is possible that the effectiveness of strategies for improving adherence and continuation are contingent on the contraceptive method they are targeting. No studies were conducted in low income settings where the health benefits of preventing unintended pregnancies could be substantial.

Implications for research.

Future trials would benefit from standardized definitions and measurements of adherence, as well as consistent terminology for describing interventions and comparisons to enhance replicability and build the evidence base. Further research in this area requires adequate statistical power to detect differences, follow‐up of at least one year, and improved reporting of trial methodology. Future research should report on objectively measurable outcomes (e.g. electronic monitoring device and biomarkers to assess pill use), and consider including a cost analysis. Future trials are also needed to explore the use of computer technologies for remote counseling, education, and reminders to improve contraceptive adherence. Lastly, future studies are needed that focus on low and middle income settings.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 April 2019 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The addition of one new study has not led to a change in the review's conclusions |

| 16 January 2019 | New search has been performed | This is an update of the Halpern 2013 publication. This update includes one new RCT. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2003 Review first published: Issue 1, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 March 2017 | Amended | 1 new study included (Garbers 2012); outcome report added for previously included abstract (Trent 2015) |

| 7 March 2017 | New search has been performed | Search updated |

| 4 September 2013 | New search has been performed | Searches were updated. |

| 24 July 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Three new trials were included (Berenson 2012; Castaño 2012; Trent 2015). One ongoing trial was added (Smith 2013a). |

| 23 July 2013 | Amended | Excluded two unpublished trials that were previously included (Andolsek 1982; Burnhill 1985). Further examination revealed they did not focus on hormonal methods of contraception. |

| 6 January 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Two new trials were added (Hou 2010; Kirby 2010), along with one ongoing study (Berenson 2010). |

| 23 November 2010 | New search has been performed | Searches were updated for MEDLINE, CENTRAL, and POPLINE. New searches were conducted for ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP. |

| 21 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 28 September 2005 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

Carol Manion of FHI 360 assisted with literature searches.

Vera Halpern of FHI 360 developed the idea of the review, did the primary data extraction, and drafted the initial review.

David A Grimes, formerly of FHI 360, participated in writing the initial review, and did the secondary data extraction for the updates in 2008 and 2010.

Laureen M Lopez, formerly of FHI 360, was an author on the initial review and conducted the updates through 2013. See below for those contributions. For the 2017 update, she did the searches, extracted data, and revised parts of the Methods and Results.

The authors and the FRG Editorial Team are grateful to the peer reviewers for their time and comments.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

2018

MEDLINE (Ovid) Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, MEDLINE (Ovid) Daily and MEDLINE (Ovid) 1946 to Present

Date Searched: July 12, 2018

| # | Searches | Results |

| 1 | Contraception/ or Contraceptive agents/ or Contraceptive agents, female/ or contraceptives, oral/ or contraceptives, oral, combined/ or ethinyl estradiol‐norgestrel combination/ or contraceptives, oral, hormonal/ or contraceptives, oral, sequential/ or contraceptives, oral, synthetic/ | 50279 |

| 2 | (contracep* or ((control* or inhibit* or prevent* or regulat* or suppress*) adj2 (ovulat* or fertili* or pregnan* or concept* or reproduct*))).tw,kf. | 96682 |

| 3 | ("depot medroxyprogesterone acetate" or "depo medroxyprogesterone acetate" or DMPA* or ((estrogen or oestrogen or intravaginal or intra‐vaginal or vaginal) adj2 (ring or rings))).tw,kf. | 2539 |

| 4 | (Depoprovera or Depo‐Provera or Depot‐Provera or Evra or Nuvaring or Nuva‐ring or Xulane or Depotext or "Contraceptive CHOICE Project").tw,kf. | 1121 |

| 5 | (Afirmelle or Alesse or Altavera or Alyacen or Amethia or Anovlar or Apri or Aranelle or Aubra or Aviane or Ayuna or Azurette or Balziva or Bekyree or Belara or Beyaz or Blisovi or Brevicon or Briellyn or Camila or Camrese or Caziant or Cerazette or Cesia or Chateal or Cilest or Cryselle or Cyclofem or Cyclafem or Cyclessa or Cycloprovera or Cyonanz or Cyred or Dasetta or Daysee or Deblitane or Delyla or Demulen or Depo‐Provera or "Depo‐subQ Provera" or Depot‐provera or Desogen or Deviry or Diane‐35 or Dianette or Elifemme or Elinest or Emoquette or Empeea or Enovid or Enovid‐10 or Enpresse or Enskyce or Errin or Estarylla or Estrostep or Estrostep‐Fe or Evra or FaLessa or Falmina or Fayosim or Femcon or Femcon‐Fe or Femhrt or Femynor or Fyavolv or Generess or Gianvi or Gildagia or Gildess or Gildess‐Fe or Heather or Incassia or Introvale or Isibloom or Jencycla or Jevantique or Jinteli or Jolessa or Jolivette or Juleber or Junel or Junel‐Fe or Kalliga or Kaitlib‐Fe or Kariva or Kelnor or Kimidess or Kurvelo or Larin or Larin‐Fe or Larissia or Layolis‐Fe or Leena or Lessina or Levlen or Levlite or Levonest or Levora or Liletta or Lillow or Litmus‐10 or Loestrin or Loestrin‐20 or Loestrin‐Fe or Logynon or Lomedia or Loryna or Lo‐Loestrin or Lo‐Minastrin or Lo‐Ovral or Low‐Ogestrel or Lo‐Seasonique or Lo‐Simpesse or Lunelle or Lutera or Lybrel or Lyndiol or Lyza or Marlissa or Marvelon or Megestrone or Meprate or Mesigyna or Mibelas‐24 or Microgestin or Microgestin‐Fe or Microgynon or Micronor or Mili or Minastrin or Mircette or Modicon or Mono‐linyah or Mononessa or Myzilra or Natazia or Necon or Nestorone or Nexesta or Nexesta‐Fe or Nikki or NOMAC‐E2 or Nor‐QD or Nora‐BE or Nordette or Norethin or Norinyl or Norlyda or Norlyroc or Nortrel or Nylia or Ocella or Ogestrel or Orgamed or Orsythia or Ortho‐Cept or Ortho‐Cyclen or Orsythia or Orthoa‐Micronor or Ortho‐Novum or Ortho‐Tri‐Cyclen or Ovcon or Ovral or Parlutal or Pimtrea or Philith or Pirmella or Portia or Previfem or Qlaira or Quartette or Quasense or Qualsense or Rajana or Rasmin or Regeeva or Rivelsa or Reclipsen or Rigevidon or Safyral or Sayana or Seasonale or Seasonique or Setlakin or Sharobel or Simlya or Simpesse or Solia or Sprintec or Sronyx or Syeda or Tarina or Tilia‐Fe or Tri‐Cyclen or Tri‐Estarylla or Tri‐Femynor or Tri‐Levlen or Tri‐lo‐Estarylla or Tri‐lo‐Marzia or Tri‐lo‐Mini or Tri‐legest or Tri‐Linyah or Tri‐Lo‐Sprintec or Tri‐Mili or Tri‐Lo‐Mili or TriNessa or TriNessa‐Lo or Tri‐Norinyl or Triphasil or Tri‐Previfem or Tri‐Sprintec or Trivora or Velivet or Vestura or Vienva or Viorele or Volnea or Vyfemla or Wera or Wymzya or Xulane or Yaela or Yarina or Yasmin or Yasminelle or Yaz or Zarah or Zenchent or Zenchent‐Fe or Zeosa or Zoely or Zovia).tw,kf. | 3939 |

| 6 | or/1‐5 | 113401 |