Abstract

Background

Previous systematic reviews have found that nurses and pharmacists can provide equivalent, or higher, quality of care for some tasks performed by GPs in primary care. There is a lack of economic evidence for this substitution.

Aim

To explore the costs and outcomes of role substitution between GPs and nurses, pharmacists, and allied health professionals in primary care.

Design and setting

A systematic review of economic evaluations exploring role substitution of allied health professionals in primary care was conducted. Role substitution was defined as ‘the substitution of work that was previously completed by a GP in the past and is now completed by a nurse or allied health professional’.

Method

The following databases were searched: Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. The review followed guidance from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

Results

Six economic evaluations were identified. There was some limited evidence that nurse-led care for common minor health problems was cost-effective compared with GP care, and that nurse-led interventions for chronic fatigue syndrome and pharmacy-led services for the medicines management of coronary heart disease and chronic pain were not. In South Korea, community health practitioners delivered primary care services for half the cost of physicians. The review did not identify studies for other allied health professionals such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Conclusion

There is limited economic evidence for role substitution in primary care; more economic evaluations are needed.

Keywords: allied health personnel, cost–benefit evaluation, general practitioners, nurses, primary health care, role substitution, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

General practice in the UK faces challenges due to an ageing population and the increasing prevalence of chronic conditions. Additional pressures also come from advances in treatments and technologies, and increased public expectations. As demand for general practice rises, workload pressures on GPs and their teams increase. There is also a recruitment and retention crisis in the GP workforce. In 2016, it was estimated that the NHS in England was approximately 6500 GPs short — this shortage is estimated to rise to 12 100 by 2020.1 The use of nurses and non-medical health professionals substituting for GPs has been proposed as a potential solution.2 Physician assistants are a new development in the NHS and have also been presented as a solution to medical staff shortages as they can diagnose, treat, and refer patients autonomously.

Previous systematic reviews have found that nurses can provide equivalent, or in some instances higher, quality of care compared with GPs in primary care.3–6 Furthermore, previous reviews have also reported positive results for pharmacists substituting for GPs in primary care.7,8 Previous reviews have explored the economic impact of task shifting in primary care,3–6 but the majority of studies did not include full economic evaluations. A previous systematic review of economic evaluations explored the substitution of skills between healthcare professionals across a variety of settings including general practice, hospital, and the community,9 but most of the evidence included was of nurses substituting for GPs and only one study was in a general practice setting. Given the limited evidence for full economic evaluations and the use of allied health professionals, this systematic review focused on full economic evaluations of role substitution including all allied health professionals with a focus on primary care, and serves as a timely update of the evidence.

The aims of this systematic review were to review economic evaluations of nurses, pharmacists, and other allied health professionals working in primary care as substitutes for some of the tasks performed by GPs.

METHOD

Selection of studies

For this systematic review of economic evaluations exploring role substitution of allied health professionals in primary care, role substitution was defined as ‘the substitution of work that was previously completed by a GP in the past and is now completed by a nurse or allied health professional’. Studies were excluded if the authors did not explicitly state within the article that role substitution was taking place. To be included in the review, the study design of the included articles had to be a full economic evaluation, either cost-effectiveness, cost-benefit, cost-utility, cost-minimisation, or cost-consequence analysis. The population assessed was patients consulting in primary care; the intervention was role substitution by allied health professionals including nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists; the comparator was GP-led care; the outcomes were economic evaluations; and the setting was primary care.

How this fits in

Previous systematic reviews have found that nurses can provide equivalent, or higher, quality of care for some tasks performed by GPs. Evidence is lacking for role substitution in other allied health professional groups such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists. There is also a lack of economic evidence for this role substitution, and a number of reviews have concluded that future research should address this. Despite the shortage of evidence, role substitution is becoming commonplace in primary care.

Identification of studies and quality assessment

A comprehensive search was performed in Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database. Search dates were from 19 May 2017 to 31 July 2017. The search strategy performed in Ovid MEDLINE is available from the authors on request. In order to recover a comprehensive set of relevant literature and to increase sensitivity, the searches were purposely broad. The search strategy included the terms ‘role substitution’, ‘task shifting’, ‘general practice’, and ‘primary care’. The ‘population’, ‘comparator’, and ‘outcome’ elements were not included in the search strategy to avoid narrowing the strategy and subsequently limiting the search results. The search was not restricted by age, date, or country of origin. Additional studies were identified through hand searching the reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews. This review conformed to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance10 (the PRISMA checklist is available from the authors). Following the removal of duplicates, two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts for relevance, and full-article screening was subsequently conducted to retrieve eligible articles. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. The same two reviewers independently assessed the quality of the included studies using Drummond and colleagues’11 checklist for economic evaluations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Quality appraisal of economic evaluations of role substitution in primary care

| Drummond question | Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project Evaluation Team (2007)12 | Dierick-van Daele et al, 201013 | Lee et al, 200414 | Neilson et al, 201515 | Richardson et al, 201316 | Turner et al, 200817 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was a well-defined question posed in an answerable form? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Was a comprehensive description of the competing alternatives given? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ |

| Was the effectiveness of the programmes or services established? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Were all the important and relevant costs and consequences for each alternative identified? | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Were costs and consequences measured accurately in appropriate physical units? | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Were costs and consequences valued credibly? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Were costs and consequences adjusted for differential timing? | n/a | – | n/a | n/a | ✓ | ✓ |

| Was an incremental analysis of costs and consequences of alternatives performed? | n/a | n/a | n/a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Was allowance made for uncertainty in the establishments of costs and consequences? | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | |

| Did the presentation and discussion of study results include all issues of concern to users? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Quality assessment score out of a possible 10 (including questions answered n/a)a | 7 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 |

Quality rating based on the number of Drummond questions answered: 0–5 = poor quality, 6–8 = moderate quality, >9 = good quality.11 ✓ = yes. ✗ = no. – = can’t tell. n/a = not applicable.

Data extraction

Key characteristics from the included study were extracted including: sample size of the intervention groups being compared, number and location of practices, type of economic evaluation and perspective, outcomes measured, and main findings.

RESULTS

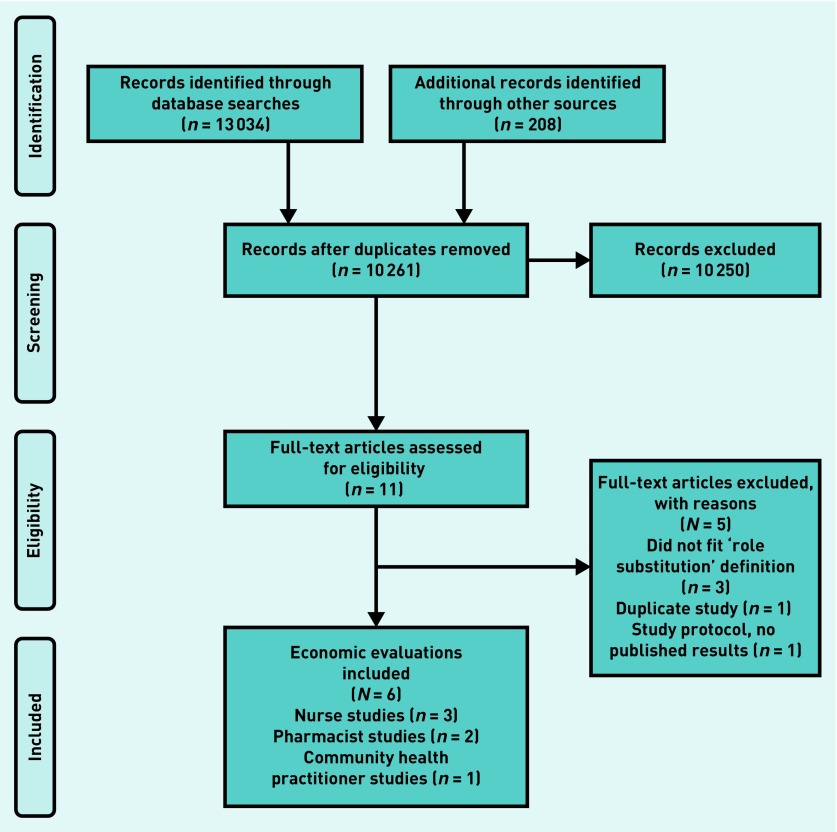

After the removal of duplicates, the search identified 10 261 studies (Figure 1). Most of these were excluded because they did not explicitly state that role substitution had occurred, were not conducted in a primary care setting, or were not full economic evaluations. Six studies were included in the review (N = 6), four studies were of good quality, and two were of moderate quality (Table 1), three used cost-minimisation, two cost-utility, and one cost-effectiveness analysis (Table 2). Due to the heterogeneity of included studies, a narrative review is presented.

Figure 1.

Systematic review flow diagram.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies (N = 6)

| Characteristic | Studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project Evaluation Team12 | Dierick-van Daele et al13 | Lee et al14 | Neilson et al15 | Richardson et al16 | Turner et al17 | |

| Country of origin | England | Netherlands | South Korea | UK | England | UK |

| Aims | To assess the cost-effectiveness of a comprehensive community pharmacy medicines management (MEDMAN) service for patients with coronary heart disease | To assess the difference in costs between GPs and nurse practitioners (NPs) in treating common conditions | To assess community health practitioner services in primary care, and to assess the economic impact of these services | To measure the differences in mean costs and effects of a pharmacy-led service for the management of chronic pain in primary care | To assess the cost-effectiveness of nurse-led self-help treatments for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalitis in primary care | To assess health service resource use of nurse-led disease management for secondary prevention in patients with chronic heart disease and heart failure in primary care |

| Type of allied health professional substituting | Pharmacists | Nurse practitioners | CHPs | Pharmacists | Nurses | Nurses |

| Setting | Nine general practice sites | 15 general practices | Random sampling of CHPs working in community health posts | Six general practices | 186 general practices | 20 general practices |

| Length of follow-up | 12 months | 2 weeks | 6 months | 6 months | 70 weeks | 12 months |

| Type of economic evaluation analysis conducted | Cost-minimisation | Cost-minimisation | Cost-minimisation | Cost-utility | Cost-effectiveness | Cost-utility |

| Primary outcome measure | Appropriate treatment and health status (measured using the SF-36 and EQ-5D) | Direct costs within the healthcare sector and costs outside the healthcare sector (productivity losses) | Activity measures, for example, consultations and cost measures | Differences in mean total costs and effects QALYs | Costs and HRQoL, measured using QALYs | QALYs measured using EQ-5D |

| Quality assessment scorea | 7 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 |

Quality rating based on the number of Drummond questions answered: 0–5 = poor quality, 6–8 = moderate quality, > 9 = good quality.11 CHPs = community health practitioners. EQ-5D = European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions measure. HRQoL = health-related quality of life. QALYS = quality-adjusted life years. SF-36 = Short Form-36 Health Survey.

Substitution by nurses

Three economic evaluations investigated the cost-effectiveness of nurses substituting for GPs (two evaluations examining nurses and one evaluation examining nurse practitioners)13,16,17 (Table 2). A good-quality cost-utility analysis assessed health service resource use of a nurse-led disease management programme for secondary prevention in patients with chronic heart disease and heart failure in primary care, compared with usual GP care.17 Length of follow-up was 12 months. The nurse-led group was associated with higher costs relating to all categories of resource use, compared with the usual care group (P<0.01). A difference of 0.03 quality-adjusted life years (QALY) value was reported between the nurse-led group and usual care, and the cost per QALY gained in the nurse-led group was 13 158 GBP (17 694 GBP, inflated to 2016/2017 prices).18 It is unclear whether there was a statistically significant difference in QALYs between the nurse-led disease management programme and usual care, as confidence intervals were not reported in the article (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of included studies (N = 6)a

| Evaluation | Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project Evaluation Team12 | Dierick-van Daele et al13 | Lee et al14 | Neilson et al15 | Richardson et al16 | Turner et al17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of publication and country | 2007, England | 2010, Netherlands | 2004, South Korea | 2015, UK | 2013, England | 2008, UK |

| Intervention groups compared; size, type of role substitution, and setting | Intervention: pharmacist (n= 62). Control: GPs (n= 164); pharmacist-led medicines management versus standard care from the GP in nine general practices | Intervention: nurse practitioners (n= 12). Control: GPs (n= 15); role substitution of nurse practitioners by GPs in 15 general practices | Intervention: CHP (n= 600). Control: care delivered by physician; CHP services versus no-CHP services in primary health care. Postal survey questionnaire sent to a sample of CHPs nationwide | Intervention 1: pharmacists medication review with pharmacist prescribing (n= 70). Intervention 2: pharmacist review only (n= 63). Control: TAU from GP (n = 63); pharmacy-led care versus TAU for the management of chronic pain in six general practices | Intervention 1: nurse-led PR (n= 85). Intervention 2: nurse-led SL (n= 97). Control: TAU from GP (n= 92); nurse-led supported self-management compared with TAU in 186 general practices | Intervention: nurse-led care (n= 505). Control: TAU from GP (n= 658); nurse-led disease management versus standard GP care in 20 general practices |

| Type of economic evaluation analysis | Cost-minimisation | Cost-minimisation | Cost-minimisation | Cost-utility | Cost-effectiveness | Cost-utility |

| Main outcomes measured, type of costs measured, type of outcomes measured | Total NHS costs; direct costs of delivering the intervention and NHS treatment costs (for example, cost of medicines), and indirect costs of training (for example, attendance fees); and appropriate treatment and health status (SF-36 and EQ-5D) | Costs of GP versus nurse practitioner consultation; direct costs within the healthcare sector and costs outside of the healthcare sector (productivity losses); and process outcomes and outcomes of care | Total costs of care between CHP services model and no-CHP services model of care; direct costs (for example, personnel costs, materials) and indirect costs (operational and depreciation costs) of CHP services. Direct costs (for example, outpatient costs) and indirect costs (travel and loss of earnings) of no-CHP services; outcomes not assessed. The efficacy of the intervention was based on previous findings | Differences in mean total costs and effects of pharmacist-led management versus GP-led management of chronic pain; direct costs, other costs borne by patients, and productivity losses; and health utility derived from SF-6D | QALYs derived from the EQ-5D; cost to the NHS (for example, resource use and unit costs), private expenditures, informal care costs, and loss of production costs; health utility measured using EQ-5D | QALYs derived from the EQ-5D; direct costs (including travel costs); health utility measured with EQ-5D |

| Perspective of analysis | Not stated | Practice and societal | Not stated | NHS | NHS and personal social services | Patient and NHS |

| Currency and cost year | GBP derived from general practice-held records. Cost year not reported | Euros derived using the price index of Statistics Netherlands for cost year 2006 | South Korean Won converted to USD derived from national unit costs for cost year 1999 | GBP derived from PSSRU and British National Formulary for prices at cost year 2009/2010 | GBP derived from NHS reference costs and PSSRU at 2008/2009 prices | GBP derived from HRGs for cost year 2002 to 2003 and inflated to 2003/2004 prices |

| Discounting and sensitivity analysis | Follow-up period 12 months, no discounting, no sensitivity analysis | Sensitivity analysis varying GP salary, no discounting | 6-month time horizon, no discounting, no sensitivity analysis | 6-month time horizon, no discounting. Three sensitivity analyses were conducted with imputed values for SF-36 scores | Costs and outcomes were discounted at a rate of 3.5% per year. A complete case analysis as part of sensitivity analysis was conducted | Follow-up period 12 months, no discounting, discount rate of 6% for equipment and training that would have an expected lifespan of more than 1 year. No sensitivity analysis |

| Intervention costs and main findings | Total NHS costs at baseline: intervention group, 852 GBP; control group, 738 GBP. Total NHS costs at follow-up: intervention, 971 GBP; control, 835 GBP. Statistically significant difference (P<0.01) in total NHS costs, due to the costs of providing pharmacists’ training. Mean difference in costs of 135 GBP (164 GBP inflated to 2016/2017 prices)18 | Cost per NP consultation, 32 Euros; cost per GP consultation, 40 Euros; lower direct consultation costs for NP compared with GP (P= 0.01) mean difference 8 Euros (7 GBP inflated to 2016/2017 prices)18 | Mean direct costs: CHP, 2424 USD (SD 566) (2520 GBP inflated to 2016/2017 prices).18 Physician, 5188 USD (SD 3262.5 USD) (5394 GBP inflated to 2016/2017 prices).18 Mean indirect costs CHP (500 USD, SD 258 USD) physician (1269 USD, SD: 952 USD); t-test found a significant difference in the average costs of care between the groups (P= 0.01 cost ratio of 2.16, with a range of 0.09 to 9.63) | Unadjusted total mean costs: prescribing group 452 GBP (509 GBP in 2016/2017 prices18); medication review group 570 GBP (642 GBP in 2016/2017 prices18); TAU group 1333 GBP (1500 GBP in 2016/2017).18 After adjusting for baseline costs, TAU was more costly than both pharmacy-led interventions (P= 0.01); cost differences relative to TAU was 78 GBP (87 GBP inflated to 2016/2017 prices)18 for prescribing group and 54 GBP (61 GBP inflated to 2016/2017 prices).18 However, once ICERs were calculated, both pharmacy-led interventions were more costly, with slightly higher QALY gains than TAU | Excluding intervention costs of SL and PR, at 70-week follow-up, total NHS cost of chronic fatigue syndrome 789 GBP for PR, 916 GBP for SL, and 710 GBP for TAU; TAU was slightly more effective than PR and SL, at a lower cost, when baseline differences in EQ-5D were adjusted. The nurse-led PR intervention produced a cost per QALY of 39 583 GBP (inflated to 44 812 GBP in 2016/2017)18 | Total mean NHS delivery costs nurse 1108 GBP and GP 661 GBP (P<0.01); a difference of 0.03 QALY value was reported between the nurse-led group and usual care, and the cost per QALY gained in the nurse-led group was 13 158 GBP (17 694 GBP inflated to 2016/2017 prices)18 |

| Conclusions | No change in numbers of patients receiving appropriate treatment. Pharmacy-led group more costly than standard care | Direct costs of consultations were lower for NPs than GPs. The differences in costs were mainly due to differences in salary | Care provided by a physician was twice as costly as the CHP services due to travel costs and loss of earnings for patients who would have had to travel to inner-city clinics to see a physician | The authors concluded that pharmacy-led management is more costly than usual treatment and produces similar QALYs compared with TAU | Nurse-led PR intervention was not cost-effective | Nurse-led disease management programme was cost-effective |

Costs are given with no decimal places and CIs and P-values to two decimal places. CHP = community health practitioner. CI = confidence interval. EQ-5D = European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions measure. HRG = healthcare resource groups. n = number of individuals. ICER = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. NP = nurse practitioner. PR = pragmatic rehabilitation. PSSRU = Personal Social Services Research Unit. SF-36 = Short Form-36 Health Survey. SF-6D = Short Form-Six Dimension health index. SL= supportive listening. TAU = treatment as usual. QALY = quality-adjusted life years.

A good-quality cost-minimisation analysis conducted alongside a randomised controlled trial (RCT) compared the differences in costs between GPs and nurse practitioners (NPs) in treating common minor health problems.13 Cost-minimisation was used because the RCT found no significant differences in effectiveness between GPs and NPs. The study had a short follow-up period of 2 weeks (Table 2). The costs of NP consultations were significantly lower than with GPs (P = 0.01) with a mean difference of 8 Euros, which equates to 7 GBP inflated to 2016/2017 prices.18 Sensitivity-analysis varying GP salary reported significantly lower costs of NP consultations when adjusting to the salary of an employed GP (P<0.007) or of a GP employed by other GPs in partnership (P = 0.02) (more information available from text in results section or from original paper13).

A good-quality cost-effectiveness analysis of nurse-led pragmatic rehabilitation (PR), and supportive listening (SL), for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome was compared with treatment as usual (TAU) by GPs.16 Costs and outcomes were discounted at a rate of 3.5% per year; however, there was no further detail of how this discounting was performed. Length of follow-up was 70 weeks and patients were asked to recall use of hospital services, day services, and contacts made with health professionals during this period. TAU was slightly more effective than PR and SL, at a lower cost, when baseline differences in European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) were adjusted. Richardson et al reported that all confidence intervals (CIs) for estimations of costs and effects crossed zero.16 Imputated results showed that PR has a mean incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) QALY of −0.01, 95% CI = −0.09 to 0.07 and SL had a mean ICER QALY of −0.04, 95% CI = −0.12 to 0.04 (more information available from text in results section or from original paper16).

SL was no more effective than PR or TAU, but costed more; therefore, SL was not found to be cost-effective. Complete case analysis as part of sensitivity analyses showed PR was associated with slightly higher QALYs than TAU, but confidence intervals crossed zero. Complete case results found that PR had a mean ICER QALY of −0.01, 95% CI = −0.08 to 0.10) and SR had a mean ICER QALY of −0.04, 95% CI = −0.13 to 0.05 (more information available from text in results section or from original paper16).

The nurse-led PR intervention produced a cost per QALY of 39 583 GBP (44 812 GBP inflated to 2016/2017).16,18 It was concluded that the nurse-led PR intervention would not be deemed cost-effective in the UK at the current NICE threshold of 20 000 to 30 000 GBP per QALY (Table 3).

Substitution by pharmacists

Two moderate-quality economic evaluations assessed the substitution of medicines management by pharmacists instead of GPs12,15 (Table 2). A cost-minimisation analysis explored the cost-effectiveness of a comprehensive community pharmacy medicines management project service12 for patients with coronary heart disease.The study follow-up period was 12 months. Total NHS costs at baseline were 852 GBP and 738 GBP for the intervention and control group, respectively. The difference in costs between groups at baseline was 114 GBP (P<0.01) (139 GBP inflated to 2016/2017 prices).18 Total NHS costs at follow-up were 971 GBP and 835 GBP for the intervention and control groups, respectively. Total NHS costs at follow-up for the pharmacist group were significantly greater than the control group (P<0.01) with a mean difference in costs of 135 GBP (164 GBP at 2016/2017 prices18) (Table 3). This was due to the costs of providing the additional pharmacist training. The differences in QALYs between groups was 0.04 (95%, CI = −0.05 to 0.13); this was non-significant (more information available from text in results section or from original paper12). An ICER was not presented in the article.

A cost-utility analysis of a pharmacy-led service for the management of chronic pain15 as part of a three-arm RCT compared pharmacist-led medication review with face-to-face pharmacist prescribing, pharmacist-led medication review with feedback to GP, and TAU from the GP. Study follow-up was 6 months. After baseline costs were adjusted, both pharmacy-led interventions were more costly than TAU. Relative to TAU, the adjusted mean costs differences per patient was 78 GBP (87 GBP inflated to 2016/2017 prices)18 (95% CI = −82 to 237) for prescribing and 54 GBP (61 GBP inflated to 2016/2017 prices)18 (95% CI = −103 to 212) for medication review. Relative to TAU, the adjusted mean QALYs to 0.01 (95% CI = −0.01 to 0.02) for prescribing and 0.01 (95% CI = −0.01 to 0.02) for medication review (Table 3). The authors did not report an adjusted mean cost for TAU in the paper.

Community health practitioners

A good-quality cost-minimisation analysis from South Korea compared the delivery of primary care services by community health practitioners (CHPs) in remote communities with equivalent care delivered by physicians in inner-city clinics (no CHP services)14 (Table 3). CHPs were described as registered nurses responsible for the delivery of primary care, who had received 6 months of special training. The length of study follow-up was 6 months. The mean total cost of CHP services per month was 2424 USD (2520 GBP inflated to 2016/2017).18 The total mean costs of no CHP services was 5188 USD (5394 GBP in 2016/2017).18 Total mean costs were significantly lower for CHP services (P<0.01) with a cost ratio of 2.16 (SD 1.24, range 0.09 to 9.63). Indirect costs were also lower for the CHP services group, due to travel costs and loss of earnings for patients in the physician group, who had to travel to inner-city clinics to see a physician.

The review did not identify studies for other allied health professionals such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

DISCUSSION

Summary

Nurse-led care for common, minor health conditions was as effective as and less costly than GP care. Nurse-led preventive care for secondary prevention of heart disease and heart failure was more costly and similar in effectiveness as usual GP care. It is uncertain whether there was a statistically significant difference in the QALY value reported between groups as confidence intervals were not reported in the article. Nurse-led interventions for chronic fatigue syndrome were more costly and less effective. Pharmacy-led services for the medicines management of coronary heart disease were as effective as, but more costly than, GP care. For managing chronic pain, pharmacy-led care was slightly more effective than GP care for increased cost. In South Korea, community health nurse practitioners delivered primary care services for half the cost of physicians. There was a lack of economic evidence for role substitution by other groups of allied health professionals such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Strengths and limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic review that identifies full economic evaluations of the substitution of GPs by allied health professionals in a primary care setting. This review undertook extensive literature searches using a well-developed search strategy and robust methodology, and adhered to the PRISMA guidelines.10 There were no restrictions on date of publication or country of origin for the included studies. Economic evaluations conducted alongside RCTs are important as they produce reliable estimates of cost-effectiveness at low marginal cost.19 Of the six studies included in the review, five were concurrent economic evaluations alongside RCTs.12,13,15–17

There were a number of limitations in the included studies. Consultation length was not considered in two of the economic evaluations that found role substitution to be cost-effective.14,17 Although the results reported lower unit costs in these studies, nurse and CHP consultations may have been significantly longer than GP consultations, so actual costs may have been higher for the allied health professional groups. Only one of the included studies explicitly provided information on patient recall including contacts made with healthcare professionals over the study period.16 There was a lack of information regarding patient recall in the other included studies, making it difficult to ascertain how information on services used by patients was gathered, whether the appropriate perspective was chosen to include all relevant costs, and whether the length of time horizon patients were asked to recall was appropriate. The South Korean study may not be directly comparable with the UK and other countries with highly developed primary care services. There was a lack of explanatory detail when describing the intervention and control treatments, which might be improved by the inclusion of a concurrent process evaluation. For example, two studies provided only minimal information about usual GP care12,16 (the economic evaluation appraisal tool responses are available from the authors on request). In addition, the economic evaluation method can be criticised where no significant differences in outcomes were found between groups, and a cost-minimisation analysis was conducted.12 Given the lack of a statistically significant effect, a cost-consequence analysis may have been more appropriate. There were inconsistencies in the reporting of findings of the included studies, for example, ICER calculations and CIs around small differences in QALYs that make interpretation of results difficult. In one study17 authors’ conclusions are not supported by their findings. Despite the higher service use costs reported substituting nurses for GPs, the authors concluded that the nurse-led disease management programme was cost-effective as it fell below the NICE cost-effectiveness threshold of 20 000 to 30 000 GBP per QALY.20 However, this finding does not provide clear evidence of cost-effectiveness for this intervention given it was more costly than GP-led care. Furthermore, there was a lack of clarity about the perspective adopted, with two studies not providing this information (economic evaluation appraisal tool responses are available from the authors on request). This lack of clarity makes it difficult to ascertain whether all pertinent costs and outcomes were included in the analysis. Additionally, only two of the included studies16,17 produced a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve.

There were disparities between the country and the type of role substitution that took place in the included studies. This review used a specific definition of role substitution; however, there were difficulties distinguishing true role substitution in the included studies, which makes generalisability difficult. The majority of the included studies assessed novel allied health professional-led interventions; these studies represent a different kind of role substitution whereby allied health professionals are used to replace GP-led care. When reviewing the literature the definition of role substitution was used to uncover economic literature of allied health professionals performing care in place of a GP. In order to better inform current policy with regards to increasing the involvement of allied health professionals in primary care, future studies should assess the cost-effectiveness of all forms of role substitution to better understand the impact of such workforce redesign. From the included studies, generalisability of results is difficult as each study assessed different allied health professionals, and used different interventions, outcome measures, and time horizons. There is a larger evidence base for role substitution with nurses; in order to improve the generalisability of role substitution with other allied health professionals further evidence is needed. Finally, the majority of articles were within a 1-year time horizon (70-week time horizon in one study); none of the studies extrapolated beyond this. Given the range of interventions it would have been useful for the authors to justify their chosen time horizon in order to assess if this was appropriate and relevant for expected outcomes resulting from the intervention. A new, innovative service redesign such as role substitution in primary care may not necessarily show changes in the immediate term; therefore, future studies with longer time horizons are recommended.

Comparison with existing literature

The evidence reported by previous systematic reviews only reported the economic impact of role substitution of GPs by nurses and pharmacists in terms of their costs. These are not considered full economic evaluations as they do not synthesise costs and outcomes.3–8

In 2008, Dierick-van Daele et al reviewed economic evaluations of the substitution of skills between health professionals in a variety of settings including general practice, hospital, and community settings. However, the majority of the evidence looked at nurses and only one of the included studies took place in general practices.9 Dierick-van Daele and colleagues stated that this article was an economic evaluation, but did not compare costs and outcomes, and therefore it would not be considered a full economic evaluation. The current systematic review serves as a timely update of the evidence and identifies full economic evaluations of role substitution in primary care.

Implications for research and practice

There is only limited evidence that nurses and allied health professionals can provide a cost-effective alternative to GPs. This evidence is most convincing for the management of common, minor health problems by nurses. However, it is worth acknowledging the majority of included studies in this review assessed novel interventions using allied health professionals to replace GP-led care. This broadens the use of role substitution, which could have implications on evidence as workforce redesign continues to grow. Role substitution is becoming commonplace throughout primary care but there is a lack of economic evidence. More high-quality economic evaluations are needed for all of the different roles that nurses and allied health professionals could perform in primary care instead of GPs. There is a particular lack of evidence for substitution by physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and physician associates in primary care.

The substitution of GPs by allied health professionals may have the potential to reduce costs, but this is greatly reliant on salary differences. Furthermore, consultation length and patient recall must also be considered. Though it may seem less costly to employ allied health professionals in general practice in terms of their unit costs, their consultation lengths may be longer, and they also might be associated with higher patient recall to general practice. Consequently, employing allied health professionals to perform roles and duties normally completed by GPs may prove more costly overall.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Maggie Hendry for her invaluable advice on the development of the search strategy and Yasmin Noorani, Academic Support Librarian at Bangor University, for her assistance with the database searches.

Funding

This research was funded by a Health and Care Research Wales PhD Studentship, awarded on 1 October 2016 to Professor Nefyn Howard Williams (reference number: HS-16-31).

Ethical approval

Not applicable as the article reports a systematic review.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

Nefyn H Williams is a GP principal in Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board and reports additional research grants from NIHR Health Technology Assessment and Health Services and Delivery Research programmes. Alun Surgey is a GP and therefore reports funds from Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board. All other authors have nothing to declare.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Hayhoe B, Majeed A, Hamlyn M, Sinha M. Primary care workforce crisis: how many more GPs do we need?. Presented at RCGP Annual Conference; Harrogate. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laurant M, Harmsen M, Wollersheim H, et al. The impact of nonphysician clinicians: do they improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of health care services? Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(Suppl 6):36S–89S. doi: 10.1177/1077558709346277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laurant MG, Reeves D, Hermens RP, et al. Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2(2):CD001271. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horrocks S, Anderson E, Salisbury C. Systematic review of whether nurse practitioners working in primary care can provide equivalent care to doctors. BMJ. 2002;324(7341):819–823. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7341.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuethe MC, Vaessen-Verberne AA, Elbers RG, Van Aalderen WM. Nurse versus physician-led care for the management of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2(2):CD009296. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009296.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martínez-González NA, Rosemann T, Tandjung R, Djalali S. The effect of physician-nurse substitution in primary care in chronic diseases: a systematic review. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145:w14031. doi: 10.4414/smw.2015.14031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chisholm-Burns MA, Lee JK, Spivey CA, et al. US pharmacists’ effect as team members on patient care: systematic review and meta-analyses. Med Care. 2010;48(10):923–933. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e57962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paudyal V, Watson MC, Sach T, et al. Are pharmacy-based minor ailment schemes a substitute for other service providers? A systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Dierick–van Daele A, Spreeuwenberg C, Derckx EW, et al. Critical appraisal of the literature on economic evaluations of substitution of skills between professionals: a systematic literature review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(4):481–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project Evaluation Team The MEDMAN study: a randomized controlled trial of community pharmacy-led medicines management for patients with coronary heart disease. Fam Pract. 2007;24(2):189–200. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dierick-van Daele AT, Steuten LM, Metsemakers JF, et al. Economic evaluation of nurse practitioners versus GPs in treating common conditions. Br J Gen Pract. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Lee T, Ko IS, Jeong SH. Is an expanded nurse role economically viable? J Adv Nurs. 2004;46(5):471–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neilson AR, Bruhn H, Bond CM, et al. Pharmacist-led management of chronic pain in primary care: costs and benefits in a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e006874. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson G, Epstein D, Chew-Graham C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of supported self-management for CFS/ME patients in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner DA, Paul S, Stone MA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a disease management programme for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and heart failure in primary care. Heart. 2008;94(12):1601–1606. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.125708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curtis L, Burns A. Unit costs of health and social care 2017. Canterbury: Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrou S, Gray A. Economic evaluation alongside randomised controlled trials: design, conduct, analysis, and reporting. BMJ. 2011;342:d1548. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence How NICE measures value for money in relation to public health interventions. 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/guidance/LGB10-Briefing-20150126.pdf (accessed 26 Mar 2019)