Abstract

Background:

Ceramides have been implicated in the pathophysiology of HIV infection and cardiovascular disease (CVD). However, no study, to our knowledge, has evaluated circulating ceramide levels in association with subclinical CVD risk among HIV-infected individuals.

Methods:

Plasma levels of four ceramide species (C16:0, C22:0, C24:0 and C24:1) were measured among 398 women (73% HIV+) and 339 men (68% HIV+) without carotid artery plaques at baseline from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study and the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. We examined associations between baseline plasma ceramides and risk of carotid artery plaque formation, assessed by repeated B-mode carotid artery ultrasound imaging over a median 7 year follow-up.

Results:

Plasma levels of C16:0, C22:0 and C24:1 ceramides were significantly higher in HIV-infected individuals compared to those without HIV infection (all P<0.001), and further analysis indicated that elevated ceramide levels were associated with antiretroviral therapy (ART) use, particularly protease inhibitor use, in HIV-infected individuals (all P<0.001). All four ceramides were highly correlated with each other (r=0.70 to 0.94; all P < 0.001) and significantly correlated with total-cholesterol (r=0.42 to 0.58; all P<0.001) and LDL-cholesterol (r=0.24 to 0.42; all P< 0.001) levels. Of note, C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides, rather than C22:0 and C24:0 ceramides, were more closely correlated with specific monocyte activation and inflammation markers (e.g., r=0.30 between C16:0 ceramide and soluble CD14; P<0.001) and surface markers of CD4+ T cell activation. A total of 112 participants developed carotid artery plaques over 7 years, and higher levels of C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides were significantly associated with increased risk of carotid artery plaques (relative risk [95% CI]=1.55 [1.29, 1.86] and 1.51 [1.26, 1.82] per standard deviation increment, respectively; both P<0.001), after adjusting for demographic and behavioral factors. After further adjustment for CVD risk factors and immune activation markers, these associations were attenuated but remained significant. Results were consistent between men and women, and between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected participants.

Conclusions:

In two HIV cohorts, elevated plasma levels of C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides, correlating with immune activation and inflammation, were associated with ART use and progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis.

Keywords: association study, atherosclerosis, HIV infection, lipid metabolites

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has become one of the major health problems in people living with HIV, since survival has improved due to antiretroviral therapy (ART) use.1 Although accumulating evidence suggests that traditional CVD risk factors, treatment-related metabolic changes, HIV viremia, and chronic immune activation and inflammation may contribute to HIV-related CVD risk, a complete understanding of its pathophysiology remains to be elucidated.2–3 Recently, there has been an increased interest in the role of ceramides, a class of bioactive lipids composed of sphingosines and fatty acids, in the development of CVD.4 Elevated circulating levels of ceramides have been shown to be associated with increased risk of CVD events5–6 and CVD death,7 even after adjusting for other CVD risk factors, although differences in the associations with CVD risk were observed for ceramide species with different numbers of carbon atoms and/or double bonds in the fatty acid chain. In addition, the presence of ceramides has been detected in human coronary plaques and has been associated with plaque vulnerability, which may predict the fate of the plaque and subsequent CVD events.8 It has been suggested that modulating ceramide metabolism might lessen the burden of atherosclerosis,9 but studies on the relationship between ceramides and CVD risk in HIV-infected populations are still lacking.

Interestingly, ceramide metabolism has long been noted to be closely related to HIV infection, but the relationship has not been fully understood.10–13 HIV-1-infected cells may cause enhancement of sphingomyelin breakdown and accumulation of intracellular ceramides,10 whereas intracellular ceramide accumulation is associated with enhanced replication of HIV-1.11 Furthermore, elevated levels of ceramides in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) have been observed in HIV-1-infected individuals compared to uninfected individuals.12 On the other hand, enhancement of intracellular ceramides by pharmacological agents, by treatment with sphingomyelinase, or by exogenous addition has been found to inhibit HIV-1 infection.13

Although ceramides have been implicated separately in the pathophysiology of CVD and HIV infection, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have evaluated circulating ceramide levels and their relationships with progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis in HIV-infected individuals. In the present study, plasma levels of four ceramide species (C16:0, C22:0, C24:0 and C24:1), which have been investigated in previous studies of non-HIV populations,5–7 were measured in 737 women and men (520 HIV-infected and 217 HIV-uninfected) from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) and Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS).14 We examined their associations with HIV infection and related parameters (e.g., ART use), and progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis, assessed by repeated B-mode carotid artery ultrasound imaging over a median 7-year period.

Methods

The data, analytic methods, and study materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study participants

This study included participants from two prospective multicenter cohort studies of women and men with or at risk for HIV infection, the WIHS15 and MACS.16 Every six months, WIHS and MACS participants undergo a core visit with a comprehensive physical examination, providing biological specimens, and completing interviewer-administered questionnaires. Since 2004, the WIHS and MACS have collaborated on a uniform carotid artery imaging protocol,17 scanning the cohorts at 2–4 year intervals to ascertain progression of subclinical carotid artery atherosclerosis.14 The primary exclusion criterion was a history of coronary heart disease. In 2015, a plasma metabolomics study, which aimed to examine plasma metabolites in relation to cardiometabolic risk in the context of HIV infection, was initiated among participants aged ≥35 years who underwent carotid artery imaging for plaque assessment at a baseline visit (2004–2006) and at a follow-up visit (2011–2013).18 The current analysis included 737 women and men without prevalent carotid artery plaques and prevalent diabetes at baseline. All individuals provided informed consent, and the studies were approved by each site’s Institutional Review Board.

Carotid artery plaque ascertainment

High-resolution B-mode carotid artery ultrasound was used to image six locations in the right carotid artery of participants: the near and far walls of the common carotid artery (CCA), carotid bifurcation, and internal carotid artery. A standardized protocol was used at each visit by all sites.14, 17 Focal plaque and intima-media thickness (IMT) measures were obtained at a centralized reading center (the University of Southern California). Coefficients of variation of repeated measurements at the CCA have been published previously,19 and replicate image acquisition and interpretation studies were repeated to ensure consistency over time. A focal plaque was defined as an area with localized IMT > 1.5 mm in any of the six imaged carotid artery locations.20

Plasma ceramide measurement

Plasma levels of ceramides were profiled from stored frozen plasma specimens that had been collected at the core study visit closest to the baseline carotid artery imaging study visit using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS). The current method identified 4 ceramide species, including ceramide (d18:1/16:0), ceramide (d18:1/22:0), ceramide (d18:1/24:0), and ceramide (d18:1/24:1). For short, we labeled the 4 ceramide species as C16:0 (number of carbon atoms:number of double bonds in the fatty acid chain), C22:0, C24:0, and C24:1, respectively. Details on sample extraction, separation and MS settings have been described elsewhere.21 Briefly, LC-MS data were acquired using a Nexera X2 U-HPLC (Shimadzu Corp.; Marlborough, MA) coupled to an Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA). Lipid metabolites were extracted from plasma (10 μL) using 190 μL of isopropanol containing 1,2-didodecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (Avanti Polar Lipids; Alabaster, AL). After centrifugation, supernatants were injected directly onto a 100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm ACQUITY BEH C8 column (Waters; Milford, MA). The column was eluted isocratically with 80% mobile phase A (95:5:0.1 vol/vol/vol 10mM ammonium acetate/methanol/formic acid) for 1 minute followed by a linear gradient to 80% mobile-phase B (99.9:0.1 vol/vol methanol/formic acid) over 2 minutes, a linear gradient to 100% mobile phase B over 7 minutes, then 3 minutes at 100% mobile-phase B. MS analyses were carried out using electrospray ionization in the positive ion mode using full scan analysis over 200–1100 m/z at 70,000 resolution and 3 Hz data acquisition rate. Other MS settings were: sheath gas 50, in source CID 5 eV, sweep gas 5, spray voltage 3 kV, capillary temperature 300°C, S-lens RF 60, heater temperature 300°C, microscans 1, automatic gain control target 1e6, and maximum ion time 100 ms. Lipid identities were denoted by total acyl carbon number and total number of double bond number. Ceramide peaks were identified and confirmed using authentic reference standards and quantified using area-under-the-curve of the peaks. Raw data were processed using TraceFinder software (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA) and Progenesis QI (Nonlinear Dynamics; Newcastle upon Tyne, UK).

Assessment of HIV infection and other variables

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory variables were collected using standardized protocols at semi-annual core study visits of the WIHS and MACS.14 HIV infection was ascertained by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and confirmed by Western blot. HIV-specific parameters included CD4+ T cell counts, HIV-1 viral load, and detailed information on specific classes of ART drugs including protease inhibitors (PI), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI). Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection status was based on antibody or viral RNA testing. Demographic and behavioral variables included age, race/ethnicity, income, education, current smoking, history of injection drug use, and current crack/cocaine and alcohol use. CVD risk factors included body-mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure (SBP), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and current use of antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medications. In a subsample of men and women, serum levels of sCD14, sCD163, Galectin-3, Gal-3BP, C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), were measured.22 In addition, CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T-cell activation (CD38+HDL-DR+) and senescence (CD28-CD57+) markers were measured in a subsample of women using methods that have been previously described.23

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of participants were compared by HIV serostatus in women and men separately. Raw values of the plasma ceramides were inverse-normal transformed using a rank-based method before analysis. General linear models were used to compare ceramide levels between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected participants; and across three groups according to HIV serostatus and baseline viral load (HIV-, HIV+ viral load <80 copies/mL, or HIV+ viral load ≥80 copies/mL), HIV serostatus and baseline CD4+ T cell count (HIV-, HIV+ <500 cells/mm3, or HIV+ ≥500 cells/mm3) and HIV serostatus and current ART use at baseline (HIV-, HIV+ ART user, HIV+ ART non-user) respectively, adjusting for age and sex. In addition, the associations between ceramide levels and three different classes of ART use, including PI, NNRTI and NRTI use, were also examined. Age- and sex- adjusted Partial Spearman correlation analyses were used to estimate correlation coefficients among four ceramides, CD4+ T cell counts (HIV+ individuals only), baseline viral load (HIV+ individuals with detectable viral load only), inflammation and immune activation markers, markers of CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T-cell activation and senescence (WIHS women only), TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, SBP and DBP.

Poisson regression models with robust variance estimates were used to calculate risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of incident carotid artery plaque per standard deviation (SD) increase in ceramides and by quartiles of individual ceramides. Poisson regression models were multivariable adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, study site, current smoking, HIV serostatus, ART use, baseline viral load level, and CVD risk factors (including BMI, SBP, TC, HDL-C, antihypertensive medication and lipid-lowering medication). We further adjusted for sCD14, sCD163, Gal-3, Gal-3-BP, and IL-6 in regression models within the subgroup with these measures. Among all participants, we examined the associations between ceramides and risk of carotid artery plaque stratified by sex and HIV serostatus, and among HIV-infected individuals only, by dichotomous baseline viral load (<80 copies/mL vs ≥80 copies/mL), CD4+ T cell count (<500 cells/mm3 vs ≥500 cells/mm3) and ART use (yes vs no). All statistical analyses were performed using R (3.3.1).

Results

Participant characteristics

Baseline demographic, socioeconomic and behavioral variables between the HIV-infected (291 women and 229 men) and HIV-uninfected groups (107 women and 110 men) were generally similar and comparable, although HIV-infected participants were more likely to be current smokers, and have histories of injection -drug use (in men only) and hepatitis C virus infection, but less likely to be current crack/cocaine use (in women only) (Table 1). In both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected groups, men were older and had higher socioeconomic levels compared to women. Among the major CVD risk factors, HIV-infected participants were more likely to use lipid-lowering medications (in women only), and have lower levels of BMI (in women only), total cholesterol (in men only) and HDL cholesterol, compared to those without HIV infection. The majority of HIV-infected individuals (74% of women and 83% of men) reported of ART use at baseline, and 46% of women and 66% of men had undetectable HIV-1 viral load (≤80 copies/mL).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by HIV serostatus, 2004–2006

| Women | Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+ (n=291) | HIV− (n=107) | HIV+ (n=229) | HIV− (n=110) | |

| Age, years | 42 (38–46) | 42 (38–46) | 46 (43–50) | 47 (45–54) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White/Other | 26 (9) | 5 (5) | 129 (56) | 70 (64) |

| Hispanic | 90 (31) | 29 (27) | 26 (11) | 11 (10) |

| African American | 175 (60) | 73 (68) | 74 (32) | 29 (26) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 119 (41) | 35 (33) | 20 (9) | 5 (5) |

| High school | 86 (30) | 33 (31) | 32 (14) | 16 (15) |

| College and above | 86 (30) | 39 (36) | 177 (77) | 89 (81) |

| Annual income <$30,000/year | 245 (84) | 89 (83) | 108 (47)* | 33 (30) |

| Current smoking | 138 (47)* | 64 (60) | 82 (36)* | 25 (23) |

| Current crack/cocaine use | 22 (8)* | 19 (18) | 35 (15) | 9 (8) |

| History of injection drug use | 90 (31) | 28 (26) | 26 (11)* | 3 (3) |

| History of hepatitis C infection | 99 (34)* | 23 (21) | 35 (15)* | 7 (6) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27 (24–32)* | 29 (25–34) | 25 (23–28) | 26 (24–28) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 115 (106–124) | 116 (106–126) | 122 (115–129) | 126 (117–132) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 74 (67–81) | 72 (66–80) | 73 (68–78) | 74 (69–80) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 175 (152–206) | 182 (160–202) | 187 (156–213)* | 198 (172–222) |

| HDL cholesterol , mg/dL | 47 (38–57)* | 56 (46–66) | 43 (36–52)* | 49 (42–58) |

| Anti-hypertensive medication use | 50 (17) | 11 (10) | 36 (16) | 19 (17) |

| Lipid-lowering medication use | 12 (4)* | 0 (0) | 52 (23) | 15 (14) |

| HIV infection-related factors | ||||

| CD4+ T cell count, cells/mm3 | 438 (290–618) | n/a | 519 (359–689) | n/a |

| HIV-1 viral load, copies/mL | 160 (80–4550) | n/a | 40 (40–1280) | n/a |

| Undetectable viral load (≤80 copies/mL) | 134 (46) | n/a | 152 (66) | n/a |

| ART use in past 6 months | 215 (74) | n/a | 191 (83) | n/a |

Data are median (IQR) or n (%), assessed at baseline unless otherwise noted.

P<0.05 for comparisons between HIV positive and HIV negative participants (data were analyzed in women and men separately). The P-values for continuous and categorical variables were generated by Mann-Whitney U test and chi-square test, respectively, except for lipid-lowering medication, which was generated by Fisher-exact test.

ART = antiretroviral therapy, HDL, High-density lipoprotein, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus, IQR = interquartile range.

HIV infection and plasma ceramides

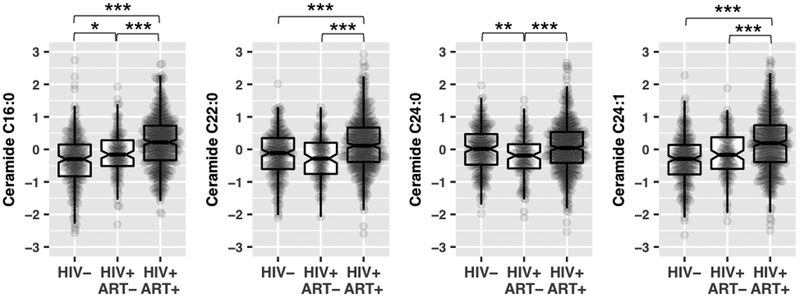

Plasma levels of all four ceramides were highly correlated with each other (r=0.70–0.94; P < 0.001, Supplemental Table 1). After adjusting for age and sex, plasma levels of C16:0, C22:0 and C24:1 ceramides (all P < 0.001), but not C24:0 ceramide (P = 0.98), were significantly higher in HIV-infected individuals compared to those without HIV infection. Of note, plasma levels of C16:0, C22:0 and C24:1 ceramides were highest in HIV-infected individuals receiving ART, while there were slight differences in plasma levels of these ceramides between HIV-infected individuals not on ART and those without HIV infection (Figure 1). Further analysis showed that PI use, but not NNRTI use, were significant associated with elevated plasma levels of ceramides (Supplemental Figure 1). The results of NRTI use and ceramide levels were the same to the overall ART use since almost all ART users had NRTI use. In addition, plasma levels of C16:0, C22:0 and C24:1 ceramides were highest in HIV-infected individuals with baseline viral load ≤80 copies/mL and those with CD4+ T cell counts > 500 cells/uL, and lowest in HIV-uninfected individuals (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Plasma levels of ceramides by HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy use.

Data are inverse-normal transformed raw values (area under the curve of metabolite peaks) of ceramides, not absolute values of ceramide concentrations in plasma, among 2405 HIV-infected individuals (HIV+) with antiretroviral therapy use (ART+), 115 HIV-infected individuals without antiretroviral therapy use (ART-), 217 HIV-uninfected individuals (HIV-). Pairwise comparisons adjusted for age and sex: ***P<0.001; **P< 0.01; *P<0.05.

Plasma ceramides, inflammation and immune activation markers, and CVD risk factors

For inflammation and immune activation markers, plasma C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides, rather than C22:0 and C24:0 ceramides, were more correlated with specific monocyte activation and macrophage inflammation markers (serum sCD14, Gal-3) and surface markers of CD4+ T cell activation and CD8+ T cell activation and senescence (all P<0.05; Supplemental Table 1). For CVD risk factors, all four ceramides were positively correlated with total cholesterol (r=0.42 to 0.58; all P<0.001) and LDL cholesterol (r=0.24 to 0.42; all P< 0.001), but not with blood pressure or BMI (Supplemental Table 1).

Plasma ceramides and risk of carotid artery plaque

Among the 737 participants (398 women and 339 men) included in the current study, 112 participants developed carotid artery plaque over a median 7-year follow-up. Higher baseline levels of all 4 ceramides, C16:0 (RR=1.47 [95% CI 1.26, 1.70] per SD increment; P<0.001), C22:0 (RR=1.26 [1.07, 1.47]; P=0.005), C24:1 (RR=1.27 [1.08, 1.49]; P=0.004) and C24:1 (RR=1.54 [1.31, 1.79]; P<0.001) ceramides were significantly associated with increased risk of carotid artery plaque in the univariate analyses. After adjusting for demographic and behavioral variables (Model 1), the associations of C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides with increased risk of carotid artery plaque slightly changed (both P<0.001), while C22:0 and C24:0 ceramides were associated with risk of carotid artery plaque at a borderline level (P=0.07 and 0.04, respectively) (Table 2). After further adjustment for CVD risk factors (Model 2), the associations of C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides with carotid artery plaque were attenuated but remained significant (P=0.002 and 0.004, respectively), while the associations of C22:0 and C24:0 ceramides with carotid artery plaque fully disappeared (P=0.96 and 0.86, respectively). Further adjustment for HIV infection and related factors did not change the association materially (Model 3). Among these analyses, the significant associations of C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides with carotid artery plaque passed the Bonferroni correction (all P<0.0125 [0.05/4]). Analyses by-quartile mimicked the linear relationships of plasma C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides with risk of carotid artery plaque (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Associations of plasma ceramides with risk of carotid artery plaque

| All | Women | Men |

P for interaction |

HIV+ | HIV− |

P for interaction |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | P-value | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | ||||

| No. of participants | 112/737 | 45/398 | 67/339 | 90/520 | 22/217 | ||||

| Ceramide (C16:0) | |||||||||

| Model 1* | 1.55 (1.29–1.86) | <0.001 | 1.75 (1.34–2.28) | 1.39 (1.08–1.78) | 0.18 | 1.46 (1.17–1.84) | 1.37 (0.93–2.02) | 0.85 | |

| Model 2† | 1.44 (1.14–1.83) | 0.002 | 1.49 (1.01–2.19) | 1.39 (1.03–1.88) | 0.21 | 1.43 (1.06–1.93) | 1.18 (0.71–1.94) | 0.99 | |

| Model 3ǂ | 1.40 (1.09–1.79) | 0.007 | 1.46 (0.98–2.17) | 1.36 (0.99–1.87) | 0.25 | 1.46 (1.08–1.97) | 1.18 (0.71–1.94) | 0.66 | |

| Ceramide (C22:0) | |||||||||

| Model 1* | 1.22 (0.99–1.51) | 0.07 | 1.31 (0.95–1.80) | 1.10 (0.82–1.48) | 0.39 | 1.17 (0.93–1.46) | 1.05 (0.62–1.77) | 0.74 | |

| Model 2† | 1.01 (0.76–1.34) | 0.96 | 0.94 (0.56–1.56) | 1.00 (0.70–1.41) | 0.45 | 1.06 (0.77–1.46) | 0.61 (0.31–1.21) | 0.55 | |

| Model 3ǂ | 0.97 (0.73–1.29) | 0.84 | 0.87 (0.51–1.47) | 0.99 (0.71–1.39) | 0.61 | 1.05 (0.77–1.45) | 0.61 (0.31–1.21) | 0.93 | |

| Ceramide (C24:0) | |||||||||

| Model 1* | 1.25 (1.01–1.55) | 0.04 | 1.41 (1.04–1.92) | 1.06 (0.77–1.44) | 0.17 | 1.19 (0.95–1.49) | 1.28 (0.72–2.27) | 0.77 | |

| Model 2† | 1.03 (0.77–1.37) | 0.86 | 1.10 (0.65–1.88) | 0.94 (0.66–1.33) | 0.22 | 1.09 (0.78–1.41) | 0.76 (0.38–1.53) | 0.62 | |

| Model 3ǂ | 1.02 (0.76–1.36) | 0.90 | 1.06 (0.62–1.82) | 0.96 (0.68–1.35) | 0.31 | 1.09 (0.78–1.52) | 0.76 (0.38–1.53) | 0.64 | |

| Ceramide (C24:1) | |||||||||

| Model 1* | 1.51 (1.26–1.82) | <0.001 | 1.60 (1.23–2.08) | 1.47 (1.12–1.93) | 0.55 | 1.35 (1.08–1.69) | 2.06 (1.28–3.30) | 0.40 | |

| Model 2† | 1.37 (1.10–1.71) | 0.004 | 1.29 (0.90–1.86) | 1.44 (1.08–1.92) | 0.85 | 1.27 (0.98–1.65) | 2.10 (1.21–3.66) | 0.30 | |

| Model 3ǂ | 1.32 (1.06–1.65) | 0.01 | 1.26 (0.85–1.86) | 1.39 (1.04–1.85) | 0.87 | 1.28 (0.99–1.65) | 2.10 (1.21–3.66) | 0.11 | |

Data are adjusted risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of carotid artery plaque per standard deviation increment in plasma ceramides (inverse-normal transformed).

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, study site, current smoking, and history of HCV.

Further adjusted for systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, antihypertensive medication use, lipid lowering medication use, and body mass index (total sample size was reduced to 705 due to missing data on CVD risk factors).

Further adjusted for HIV serostatus, HIV treatment status, and baseline viral load level.

Figure 2.

Risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of carotid artery plaque across quartiles of plasma ceramide levels.

Data were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, study site, current smoking, history of HCV, HIV serostatus, HIV treatment status, and baseline viral load level, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, antihypertensive medication use, lipid lowering medication use, and body mass index.

Associations between the four ceramides and risk of carotid artery plaque were consistent between women and men (all P for interaction>0.05), and between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected participants (all P for interaction>0.05) (Table 2). In analyses of HIV-infected individuals stratified by baseline viral load, CD4+ T cell count and ART use, the associations of C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides with risk of carotid artery plaque were consistent across different subgroups (all P for interaction>0.05; Supplemental Table 2).

Given the observed correlations between ceramides and inflammation and immune activation markers, we further examined the associations between ceramides and incident carotid artery plaque in a subsample of 669 participants (97 incident cases) with data on 5 serum inflammation and immune activation markers including sCD14, sCD163, Gal-3, Gal-3BP, and interleukin-6. After further adjustment for these 5 biomarkers, the associations of plasma C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides with incident carotid plaque remained significant (Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

The positive associations between certain ceramide species and the composite CVD outcomes have been reported in human populations without HIV infection.5–7 In the FINRISK 2002 cohort, C16:0, C18:0 and C24:1, but not C24:0 ceramides, were associated with incident and recurrent major adverse cardiovascular events among otherwise healthy individuals, after adjustment for the Framingham Risk Score factors.5 Another study in patients with stable coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes reported that C16:0 and C 24:1 ceramides had positive associations with CVD death after adjustment for LDL-C and other blood lipids, while C24:0 ceramide had an inverse association with CVD death.7 A prospective case-cohort study nested in a diet intervention trial (the PREDIMED Trial) found that higher baseline plasma levels of all four ceramides (C16:0, C22:0, C24:0 and C24:1) were associated with increased risk of CVD.6 Despite some differences, all these previous studies reported significant associations of C16:0 and C24:1ceramides with CVD risk, which is consistent with findings of the current study. Implications of ceramides in atherosclerosis and CVD risk have also been investigated in previous experimental studies. Animal models fed with myriocin, which depletes cells of ceramides, exhibited favorable plasma lipid profiles,24 a reduction in atherosclerotic lesion area,25 a reduction in the number of macrophages infiltrating atherosclerotic plaques and an increase in plaque collagen content.26 These data suggest that not only does decreased ceramide accumulation reduce the progression of atherosclerosis, but it may also increase plaque stability.27

One interesting finding of our study is that all 4 ceramides were highly correlated with each other, but only C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides, not C22:0 and C24:0 ceramides, showed independent associations with risk of carotid artery plaque after adjusting for CVD risk factors. While all four ceramides were correlated with blood lipids (TC, LDL-C and HDL-C), it should be noted that C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides showed relatively stronger correlations with specific monocyte activation and macrophage inflammation markers (e.g., sCD14) compared to C22:0 and C24:0 ceramides. These differences suggest potential mechanisms that may involve inflammation and immune activation rather than known CVD risk factors (e.g., cholesterol levels) for the observed associations between C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides and carotid artery atherosclerosis. This is in line with the biological functions of ceramides, which serve as an important second-messenger in monocytes, macrophages and many other cells, in regulating immune response and inflammation process.27–29 Ceramide signaling can be initiated by many stress stimuli, the SAPK/JNK and c-Jun/NFκB signaling pathways in particular, and the stimulation of the latter directly leads to the transcription of many inflammatory cytokines.28 Ceramides are also involved in transmitting antigens secreted from macrophages to dendritic cells, leading to an enhanced T-cell response29. However, differences in biological functions of ceramide species with different numbers of carbon atoms and/or double bonds in the fatty acid chain remains largely unknown.

Another major finding of our study is that plasma levels of ceramides were elevated in HIV-infected individuals, particularly in those using ART. This is consistent with a previous study that reported elevated ceramides in the PBMCs of HIV-infected individuals,12 however the positive association between circulating ceramides and ART use has not been previously reported. Furthermore, we observed that ceramide levels were also elevated in HIV-infected individuals with viral suppression (undetectable HIV-1 viral load) and well-controlled CD4+ T cell counts (≥500 cells/mm3). This might be explained by the higher likelihood of ART use among those with viral suppression and higher CD4+ T cell counts. However, it is unknown whether elevated ceramides associated with ART use may contribute to HIV-1 viral suppression. Elevated intracellular ceramides have been found to inhibit HIV-1 infection,13 but the potential effect of ceramides on HIV infection is more related to transmission rather than replication. Abnormalities of plasma lipid profiles have been observed in ART recipients, especially in those with use of PI-based therapy, which may be due to the structural similarity between the catalytic region of the HIV-1 protease and two homologous human proteins involved in the metabolism of lipids called cytoplasmic retinoic acid-binding protein type 1 and low-density lipoprotein-receptor-related protein type 1.30–31 Consistently, our data indicated that elevated ceramide levels were most evident among HIV-infected individuals with PI use, though it is unknown whether this can be explained by similar mechanisms. Nevertheless, the observed positive associations of ceramides with both ART use and carotid artery atherosclerosis suggest that ceramides might be involved in the links of HIV infection and ART use with CVD risk. Further studies focusing on different classes of ART are need to test longitudinally whether ART use may lead to increased ceramide levels which in turn contributes to the increased risk of CVD in HIV-infected individuals.

The main strengths of this study include two well-characterized cohorts of both HIV infected and HIV-uninfected participants, longitudinal measurement of carotid artery atherosclerosis, and careful consideration of multiple covariates include HIV parameters, CVD risk factors, and serum markers of inflammation and macrophage activation. Our study has several limitations. First, information on incident CVD events was not available; however, our subclinical measure of carotid artery atherosclerosis has been validated as a surrogate outcome for clinical CVD events.17 Second, our two HIV cohorts of women and men had differences in some sociodemographic characteristics, although results were consistent between men and women. Third, only four ceramide species were measured in the current study and a previously reported ceramide species (C18:0) could not be captured by our metabolomics method; and thus future studies with targeted methods on a broad spectrum of ceramides are needed. Finally, due to a limited number of incident plaque cases in HIV-uninfected participants, the ability to assess effect modification by HIV infection may have been underpowered.

In summary, this study found that elevated plasma ceramides were associated with ART use and progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis over a 7-year follow-up in two well-established HIV cohorts, which suggest a potential role for ceramides linking HIV infection and ART with CVD risk. Of note, among 4 highly correlated ceramides species measured in this study, only C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides, which showed significant correlations with specific inflammation and immune activation markers, were independently associated with progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis. This may suggest potential distinct biological functions of different ceramide species in relation to CVD risk, especially in the context of HIV infection. Further studies are warranted to validate our findings in other HIV-infected populations and to elucidate potential mechanisms underlying the relationship between ART use and elevated ceramide levels and its implications in the development of CVD in HIV-infected individuals.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What is new?

For the first time, the associations between four ceramide species (C16:0, C22:0, C24:0 and C24:1) in plasma and progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis were examined in HIV-infected populations.

Plasma levels of ceramide were elevated in HIV-infected individuals, which might be due to antiretroviral therapy (ART) use, particularly protease inhibitor use.

Although four ceramide species were highly correlated with each other and also correlated with blood cholesterol levels, only those (C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides) correlating with specific markers of immune activation and inflammation, were significantly associated with progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis, independently of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

What are the clinical implications?

Our findings suggest a potential role for ceramides linking HIV infection and ART use with increased risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD), and ceramides may serve as new markers, reflecting the detrimental effects of ART use, for future CVD risk in people living with HIV infection.

Our study provides new information on biological mechanisms that may involve specific monocyte activation and inflammation beyond traditional CVD risk factors (e.g., cholesterol levels) for the associations between ceramides and CVD, suggesting a potential role of ceramide reduction and immunomodulation in the prevention of CVD, especially among people living with HIV infection.

Acknowledgments:

Sources of funding: This study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) K01HL129892, and other funding sources for this study included R01HL140976, R01HL060712, R01HL141824, R01 HL126543, R01 HL132794, R01HL083760, R01HL095140, R01HL095129, and K01HL137557 from NHLBI.

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) and the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

WIHS (Principal Investigators): UAB-MS WIHS (Mirjam-Colette Kempf and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-AI-103401; Atlanta WIHS (Ighovwerha Ofotokun and Gina Wingood), U01-AI-103408; Bronx WIHS (Kathryn Anastos and Anjali Sharma), U01-AI-035004; Brooklyn WIHS (Howard Minkoff and Deborah Gustafson), U01-AI-031834; Chicago WIHS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-AI-034993; Metropolitan Washington WIHS (Seble Kassaye), U01-AI-034994; Miami WIHS (Margaret Fischl and Lisa Metsch), U01-AI-103397; UNC WIHS (Adaora Adimora), U01-AI-103390; Connie Wofsy Women’s HIV Study, Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt, Bradley Aouizerat, and Phyllis Tien), U01-AI-034989; WIHS Data Management and Analysis Center (Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Golub), U01-AI-042590; Southern California WIHS (Joel Milam), U01-HD-032632 (WIHS I – WIHS IV). The WIHS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects is also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. WIHS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA), UL1-TR000454 (Atlanta CTSA), and P30-AI-050410 (UNC CFAR).

MACS (Principal Investigators): Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health (Joseph Margolick, Todd Brown), U01-AI35042; Northwestern University (Steven Wolinsky), U01-AI35039; University of California, Los Angeles (Roger Detels, Otoniel Martinez-Maza), U01-AI35040; University of Pittsburgh (Charles Rinaldo), U01-AI35041; the Center for Analysis and Management of MACS, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health (Lisa Jacobson, Amber d’Souza), UM1-AI35043. The MACS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) at the National Institutes of Health, with additional co-funding from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects was also provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders (NIDCD). MACS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000424 (JHU CTSA).

Disclosures: None of the authors reported a conflict of interest related to the study. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Reference

- 1.Hemkens LG and Bucher HC. HIV infection and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1373–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan RC, Hanna DB and Kizer JR. Recent Insights Into Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Risk Among HIV-Infected Adults. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016;13:44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Triant V, Perez J, Regan S, Massaro J, Meigs J, Grinspoon S and D’Agostino R. Cardiovascular Risk Prediction Functions Underestimate Risk in HIV Infection. Circulation. 2018;137:2203–2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Summers S Could Ceramides Become the New Cholesterol? Cell Metab. 2018;27:276–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Havulinna AS, Sysi-Aho M, Hilvo M, Kauhanen D, Hurme R, Ekroos K, Salomaa V and Laaksonen R. Circulating Ceramides Predict Cardiovascular Outcomes in the Population-Based FINRISK 2002 Cohort. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:2424–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang DD, Toledo E, Hruby A, Rosner BA, Willett WC, Sun Q, Razquin C, Zheng Y, Ruiz-Canela M, Guasch-Ferre M, Corella D, Gomez-Gracia E, Fiol M, Estruch R, Ros E, Lapetra J, Fito M, Aros F, Serra-Majem L, Lee CH, Clish CB, Liang L, Salas-Salvado J, Martinez-Gonzalez MA and Hu FB. Plasma Ceramides, Mediterranean Diet, and Incident Cardiovascular Disease in the PREDIMED Trial (Prevencion con Dieta Mediterranea). Circulation. 2017;135:2028–2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laaksonen R, Ekroos K, Sysi-Aho M, Hilvo M, Vihervaara T, Kauhanen D, Suoniemi M, Hurme R, Marz W, Scharnagl H, Stojakovic T, Vlachopoulou E, Lokki ML, Nieminen MS, Klingenberg R, Matter CM, Hornemann T, Juni P, Rodondi N, Raber L, Windecker S, Gencer B, Pedersen ER, Tell GS, Nygard O, Mach F, Sinisalo J and Luscher TF. Plasma ceramides predict cardiovascular death in patients with stable coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes beyond LDL-cholesterol. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1967–1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uchida Y, Kobayashi T, Shirai S, Hiruta N, Shimoyama E and Tabata T. Detection of Ceramide, a Risk Factor for Coronary Artery Disease, in Human Coronary Plaques by Fluorescent Angioscopy. Circ J. 2017;81:1886–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aburasayn H, Al Batran R and Ussher JR. Targeting ceramide metabolism in obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2016;311:E423–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Famularo G, Moretti S, Marcellini S, Alesse E and De Simone C. Cellular dysmetabolism: the dark side of HIV-1 infection. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1996;48:123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivas CI, Golde DW, Vera JC and Kolesnick RN. Involvement of the sphingomyelin pathway in autocrine tumor necrosis factor signaling for human immunodeficiency virus production in chronically infected HL-60 cells. Blood. 1994;83:2191–2197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Simone C, Cifone MG, Alesse E, Steinberg SM, Di Marzio L, Moretti S, Famularo G, Boschini A and Testi R. Cell-associated ceramide in HIV-1-infected subjects. AIDS. 1996;10:675–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finnegan CM, Rawat SS, Puri A, Wang JM, Ruscetti FW and Blumenthal R. Ceramide, a target for antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15452–15457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanna D, Post W, Deal J, Hodis H, Jacobson L, Mack W, Anastos K, Gange S, Landay A, Lazar J, Palella F, Tien P, Witt M, Xue X, Young M, Kaplan R and Kingsley L. HIV Infection Is Associated With Progression of Subclinical Carotid Atherosclerosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:640–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, Sharp G, Robison E, Hessol N, Gange S, Barranday Y, Holman S, Weber K and Young MA. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1013–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaslow RA, Ostrow DG, Detels R, Phair JP, Polk BF and Rinaldo CR, Jr. The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: rationale, organization, and selected characteristics of the participants. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126:310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, LaBree L, Selzer RH, Liu CR, Liu CH and Azen SP. The role of carotid arterial intima-media thickness in predicting clinical coronary events. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi Q, Hua S, Clish CB, Scott JM, Hanna DB, Wang T, Haberlen SA, Shah SJ, Glesby MJ, Lazar JM, Burk RD, Hodis HN, Landay AL, Post WS, Anastos K and Kaplan RC. Plasma tryptophan-kynurenine metabolites are altered in HIV infection and associated with progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan RC, Kingsley LA, Gange SJ, Benning L, Jacobson LP, Lazar J, Anastos K, Tien PC, Sharrett AR and Hodis HN. Low CD4+ T-cell count as a major atherosclerosis risk factor in HIV-infected women and men. AIDS. 2008;22:1615–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Touboul PJ, Hennerici MG, Meairs S, Adams H, Amarenco P, Bornstein N, Csiba L, Desvarieux M, Ebrahim S, Hernandez Hernandez R, Jaff M, Kownator S, Naqvi T, Prati P, Rundek T, Sitzer M, Schminke U, Tardif JC, Taylor A, Vicaut E and Woo KS. Mannheim carotid intima-media thickness and plaque consensus (2004–2006–2011). An update on behalf of the advisory board of the 3rd, 4th and 5th watching the risk symposia, at the 13th, 15th and 20th European Stroke Conferences, Mannheim, Germany, 2004, Brussels, Belgium, 2006, and Hamburg, Germany, 2011. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;34:290–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paynter NP, Balasubramanian R, Giulianini F, Wang DD, Tinker LF, Gopal S, Deik AA, Bullock K, Pierce KA, Scott J, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Estruch R, Manson JE, Cook NR, Albert CM, Clish CB and Rexrode KM. Metabolic Predictors of Incident Coronary Heart Disease in Women. Circulation. 2018;137:841–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanna DB, Lin J, Post WS, Hodis HN, Xue X, Anastos K, Cohen MH, Gange SJ, Haberlen SA, Heath SL, Lazar JM, Liu C, Mack WJ, Ofotokun I, Palella FJ, Tien PC, Witt MD, Landay AL, Kingsley LA, Tracy RP and Kaplan RC. Association of Macrophage Inflammation Biomarkers With Progression of Subclinical Carotid Artery Atherosclerosis in HIV-Infected Women and Men. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1352–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan RC, Sinclair E, Landay AL, Lurain N, Sharrett AR, Gange SJ, Xue X, Hunt P, Karim R, Kern DM, Hodis HN and Deeks SG. T cell activation and senescence predict subclinical carotid artery disease in HIV-infected women. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:452–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dekker M, Baker C, Naples M, Samsoondar J, Zhang R, Qiu W, Sacco J and Adeli K. Inhibition of sphingolipid synthesis improves dyslipidemia in the diet-induced hamster model of insulin resistance: evidence for the role of sphingosine and sphinganine in hepatic VLDL-apoB100 overproduction. Atherosclerosis. 2013;228:98–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hojjati M, Li Z, Zhou H, Tang S, Huan C, Ooi E, Lu S and Jiang X. Effect of myriocin on plasma sphingolipid metabolism and atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10284–10289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park T, Rosebury W, Kindt E, Kowala M and Panek R. Serine palmitoyltransferase inhibitor myriocin induces the regression of atherosclerotic plaques in hyperlipidemic ApoE-deficient mice. Pharmacol Res. 2008;58:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aburasayn H, Al Batran R and Ussher J. Targeting ceramide metabolism in obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2016;311:E423–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruvolo PP. Intracellular signal transduction pathways activated by ceramide and its metabolites. Pharmacol Res. 2003;47:383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Y, Liu Y, Yang C, Kang L, Wang M, Hu J, He H, Song W and Tang H. Macrophages transfer antigens to dendritic cells by releasing exosomes containing dead-cell-associated antigens partially through a ceramide-dependent pathway to enhance CD4(+) T-cell responses. Immunology. 2016;149:157–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riddler SA, Smit E, Cole SR, Li R, Chmiel JS, Dobs A, Palella F, Visscher B, Evans R and Kingsley LA. Impact of HIV infection and HAART on serum lipids in men. JAMA. 2003;289:2978–2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.da Cunha J, Maselli LM, Stern AC, Spada C and Bydlowski SP. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on lipid metabolism of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: Old and new drugs. World J Virol. 2015;4:56–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.