Abstract

Purpose of Review

To review the effectiveness of remission induction strategies compared to single csDMARD-initiating strategies according to current guidelines in early RA.

Recent Findings

Twenty-nine studies, heterogeneous on, e.g., specific treatment strategy and remission outcome used, were identified. Using DAS28-remission over 12 months, 13 (76%) of 17 remission induction strategies showed significantly more patients achieving remission. Pooled relative “risk” was 1.73 [95%CI 1.59–1.88] for bDMARD-based remission induction strategies and 1.20 [95%CI 1.03–1.40] for combination csDMARD-based remission induction strategies compared to single csDMARD-initiating strategies. When additional glucocorticoid “bridging therapy” was used in single csDMARD-initiating strategies, the higher proportion patients achieving remission in remission induction strategies was no longer statistically significant (pooled RR 1.06 [95%CI 0.83–1.35]). For other remission outcomes, results were in line with above.

Summary

Remission induction strategies are more effective in achieving remission compared to single csDMARD-initiating strategies, possibly more so in bDMARD-based induction strategies. However, compared to single csDMARD-initiating strategies with glucocorticoids, induction strategies may not be more effective.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11926-019-0821-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Early rheumatoid arthritis, Induction therapy, Standard care, bDMARDs, csDMARDs, GCs

Introduction

In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), early initiation of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment, preferably within the “window of opportunity,” is thought to optimally prevent joint damage, improving long-term outcome and quality of life [1, 2].

Accordingly, current international guidelines advice to start treatment in early RA as soon as possible after diagnosis. Initial therapy is started with a conventional synthetic (cs)DMARD, most frequently methotrexate (MTX), in a “tight-controlled” manner, aiming for low disease activity or, preferably, remission [1, 3].

Initial MTX therapy is sometimes combined with short-term use of moderate-high dose glucocorticoids (GCs), which are then tapered as soon as possible: GC bridging therapy. The treatment strategy has to be intensified if the treatment target is not achieved within 6 months [1, 3]. This next step is often to add a biological (b) or targeted small molecule (ts) DMARD [4••, 5].

Previous research shows that approximately 30–50% of early RA patients need additional b/tsDMARD therapy [6].

Patients who initiate a more intensive DMARD strategy as first-line treatment than that according to current guidelines as described above have sometimes shown superior effectiveness outcomes, and achieve remission more often and earlier, sometimes also including sustained remission (SR) and even sustained drug-free remission (sDFR), which may thus become achievable treatment targets [4••, 7].

Achieving remission earlier has been found to be related to improved long-term outcomes [7].

Furthermore, SR and sDFR may become future treatment targets for early RA within the window of opportunity. This may lead to a paradigm shift towards the above described so called remission induction strategies.

For this reason, it would be interesting to investigate the effectiveness of initiating in early RA more intensive treatment strategies, compared to single csDMARD-initiating strategies according to current guidelines; these more intensive strategies herein are designated remission induction strategies.

The aim of the study is to provide a systematic summary of these remission induction strategies and their effectiveness.

Methods

Systematic Literature Search and Study Selection

A systematic review of the literature was performed according to current standards and reported according to the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement protocol [8]. In October 2018, we performed a literature search in Medline and Embase. The search combined terms relating to early RA, terms for cs-, b-, and tsDMARD and remission, and publications limited to the last 5 years and English language. More details about the research question and search terms can be found in the Supplementary file.

We defined more intensive, remission induction strategies as initiating treatment with a bDMARD or a tsDMARD, both with and without a csDMARD, or initiating a csDMARD with moderately or high-dosed GCs, with delayed tapering (not “bridging therapy”) or starting ≥ 2 csDMARDs.

The single csDMARD-initiating strategy was defined as starting treatment with a single csDMARD, with or without GCs as bridging therapy, according to the current guidelines.

All titles and abstracts were screened by MMAV. If the reviewer was unsure about in-/excluding an abstract, it was discussed with one other co-author (PMJW) and one co-investigator (MdH) to reach consensus, and in case of remaining doubt based on title/abstract, the publication was included for full text evaluation. Full text screening was performed using the same strategy.

The following selection criteria were used: (1) human studies, (2) (very, DMARD-naive) early RA patients, (3) remission induction strategy arm (according to definition of remission induction strategy, see above), (4) single csDMARD-initiating strategy arm (according to definition of single csDMARD-initiating strategy, see above) and, (5) results presented regarding the comparison of a remission induction strategy and a single csDMARD-initiating strategy on an outcome of remission.

Remission was defined as remission according to a validated disease activity index or the Boolean definition [1].

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) as well as cohort studies with appropriate correction for multiple confounders were selected. Long-term extension studies of trials satisfying the above criteria were also selected to investigate long-term effects of remission induction strategies on, e.g., radiographic progression.

Data Extraction and Outcome Assessment

The following data of studies was extracted: publication year, study design, patients’ baseline characteristics (age, gender, rheumatoid factor (RF) status, Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), symptom duration, Disease Activity Score assessing 28 joints (DAS28), a description of the single csDMARD-initiating strategy and the remission induction strategy, the number of patients per arm, a description of the remission outcome, the number of patients achieving remission per arm, a description of missing data, and other remarks deemed necessary. In case of a study evaluating long-term outcomes of a remission induction strategy, we extracted additional information (if available) for the follow-up duration, outcome for disease activity, medication use and radiographic progression.

A quality assessment of all selected publications was performed using “The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias” [9]. Information about random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome assessment, and selective reporting was evaluated.

Statistics

Relative risks (RR) for achieving remission with 95% confidence intervals (CI) per study were calculated, separate for each remission outcome definition and graphically displayed in forest plots. When appropriate, results were pooled using a random-effect model according to the Mantel-Haenszel method. To explore the effects of specific remission induction strategy used (e.g., use of a b/tsDMARD, the use of GC bridging therapy in the single csDMARD-initiating strategy) and the effect of symptom duration at start of therapy (within the window of opportunity, arbitrarily defined as symptom duration ≤ 3 months, versus outside the window of opportunity, arbitrarily defined as symptom duration > 3 months) [2], group analyses were performed.

Outcomes of studies evaluating the longer term effectiveness of remission induction strategies were only summarized descriptively.

All analyses were performed in Review manager version 5.3 [10].

Results

After screening, 23 articles and 6 conference abstracts were included, involving 6319 patients treated according to a remission induction strategy and 4647 according to a single csDMARD-initiating strategy (see flowcharts in Supplementary figure 1). Four specific groups were defined based on characteristics of the drug regime and study duration, and comparisons made: (1) b/tsDMARD-based remission induction strategy versus single csDMARD-initiating strategy without GC bridging, (2) combination csDMARD-based remission induction strategy versus single csDMARD-initiating strategy without GC bridging, (3) remission induction strategy (either combination csDMARD-based strategy or bDMARD-based strategy) versus single csDMARD-initiating strategy with GC bridging, and (4) studies evaluating long-term effects of remission induction strategies (follow-up > 4 years). An overview of patient and study characteristics of the included studies is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and disease characteristic of included studies

| First author, publication year, reference | Design | Mean age in years (SD) | Female (%) | RF+ (%) | Mean HAQ score (SD) | Mean symptom duration in weeks (SD) | Mean DAS28 (SD) | Single csDMARD-initiating strategy | N in single csDMARD-initiating strategy | Remission induction strategy | N in remission induction strategy | Time of assessments in years | Treatment characteristics (both arms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b/tsDMARD-based remission induction strategy versus single csDMARD-initiating strategy without GC bridging | |||||||||||||

| Atsumi 2016 [11] | RCT | 49 (11) | 81 | 95 | 1.1 (0.7) | 16 (11) | 5.5 (1.2) | MTX+PBO | 157 | CZP+MTX | 159 | 1 | T2T |

| Bijlsma 2016 [4] | RCT | 54 (§) | 67 | 72 | 1.2 (0.6) | 4 (§) | 5.2 (1.1) | MTX+PBO | 108 |

TCZ+MTX TCZ+PBO |

106 103 |

0.5 | T2T |

| Burmester 2016 [12••] | RCT | 50 (13) | 78 | 89 | 1.6 (0.7) | 26 (26) | 6.7 (1.0) | MTX+PBO | 289 |

TCZ+MTX TCZ+MTX (reduced dose) TCZ+PBO |

291 290 292 |

1 | T2T |

| Dougados 2014 [13] | RCT | 52 (14) | 72 | § | § | 34 (22) | 6.5 (1.0) | MTX | 178 | ETN+MTX | 213 | 1 | T2T |

| Emery 2017 [14••] | RCT | 51 (14) | 77 | 97 | 1.6 (0.6) | 12 (17) | 6.7 (0.9) | MTX+PBO | 213 | CZP+MTX | 655 | 1 | T2T |

| Horslev-Petersen 2014 [15] | RCT | 55 (§) | 66 | 72 | 1.1 (§) | 12 (§) | 5.6§ | MTX+PBO | 91 | ADA+MTX | 89 | 1 | T2T |

| Keystone 2017 [16] | RCT | § | § | § | § | § | MTX+PBO | 210 |

BARI+MTX BARI |

215 159 |

1 | T2T | |

| Keystone 2017a [17] | RCT | 52 (14) | 84 | 73 | 1.5 (0.7) | 39 (44) | 6.3 (0.9) | MTX+PBO | 257 | ADA+MTX | 268 | 0.5 | T2T |

| Kirchgsner 2018 [18] | RCT | 48 (12) | § | § | § | § | § | PBO | 15 | INF | 15 | 1 |

No adjustments INF until 22w |

| Nam 2014b [19] | RCT | 48 (13) | 76 | 55 | 1 (0.4) | 28 (§) | 4.1 (1.1) | MTX+PBO | 55 | ETN+MTX | 55 | 1 | T2T |

| Smolen 2015 [20] | RCT | 49 (13) | 78 | 97 | 1.7 (0.7) | 26 (29) | 6.3 (1.0) | MTX+PBO | 209 | ADA+MTX | 210 | 1 | T2T |

| Stamm 2018 [21] | RCT | 53 (14) | 73 | 35 | 0.9 (0.7) | 10 (2) | 4.9 (1.4) | MTX+PBO | 36 | INF+MTX | 38 | 1 | Step up MTX |

| Takeuchi 2014 [22] | RCT | 54 (13) | 81 | 84 | 1.2 (0.8) | 16 (21) | 6.6 (1.0) | MTX+PBO | 163 | ADA+MTX | 171 | 0.5 | T2T |

| Combination csDMARD-based remission induction strategy versus single csDMARD-initiating strategy without GC bridging | |||||||||||||

| Brunekreef 2017 [23] | Cohort | 59 (14) | 62 | 65 | § | § | § | MTX | 297 | MTX+HCQ+GCim | 156 | 1 |

T2T IM 80-120 mg |

| Ma 2014 [24] | RCT | 54 (§) | 68 | 87 | 1.6 (§) | § | 5.8 (1.3) | MTX | 87 | CSA+MTX+GC | 90 | 2 |

T2T Bridg. 34w |

| Rannio 2017 [25] | Cohort | 57 (16) | 67 | 71 | 0.9 (§) | 24 (§) | 4.2 (1.4) | MTX (+GC) | 453 | MTX+SSZ+HCQ | 158 | 1 | T2T |

| Steunebrink 2016 [26] | 2 cohorts | 59 (13) | 62 | 54 | 1.1 (§) | § | 4.7 (1.1) | MTX+PBO | 128 | MTX+HCQ | 128 | 1 | T2T |

| Remission induction strategy (either combination csDMARD-based strategy or bDMARD-based strategy) versus single csDMARD-initiating strategy with GC bridging | |||||||||||||

| Akdemir 2018 [27] | 2 RCT | 54 (14) | 69 | 63 | 1.5 (0.7) | 20 (§) | 4.3 (0.8)** | MTX+GC | 175 | MTX+SSZ+GC | 133 | 1 |

T2T Bridg. 34w |

| De Jong 2014 [28] | RCT | 54 (14) | 68 | 71 | 1 (0.7) | 24 (13) | 3.4 (1.0)** | MTX+GC | 97 |

MTX+SSZ+HCQ+GCim MTX+SSZ+HCQ+GC |

91 93 |

1 |

T2T IM 80-120 mg or bridg. 10w |

| Nam 2014a* [29] | RCT | 53 (13) | 69 | 55 | 1.4 (0.5) | 5 (§) | 3.8 (1.0)** | MTX+GCiv | 57 | MTX+INF | 55 | 0.5 |

T2T IV 250 mg |

| Stouten 2017 [30] | RCT | § | § | § | § | § | § | MTX+GC | 98 |

MTX+SSZ+GC MTX+LEF+GC |

98 93 |

1 |

T2T Bridg. 34w |

| Ter Wee 2015 [31] | RCT | 52 (13) | 69 | 59 | 1.4 (0.7) | 24 (20) | 5.4 (1.2) | MTX+GC | 81 | MTX+SSZ+GC | 81 | 1 |

T2T Bridg. 34w |

| Verschueren 2017 [32] | Trial | 52 (13) | 71 | 58 | 1 (0.7) | 3 (4) | 4.7 (1.4) |

MTX+GC MTX |

141 172 |

MTX+SSZ+GC MTX+LEF+GC |

98 90 |

1 |

T2T Bridg. 34w |

| Studies evaluating long-term effects of remission induction strategies (follow-up > 4 years) | |||||||||||||

| Bergsma 2017 [33] | RCT | 55 (11) | 55 | 61 | 1.3 (0.7) | 21(§) | 4.2 (0.9) | MTX+PBO | 247 | MTX+SSZ+GC | 261 | 10 |

T2T Bridg. 34w |

| Emery 2016 [34] | RCT | § | § | § | § | § | § | MTX+PBO | 160 |

GOL GOL(reduced dose)+MTX GOL+MTX |

159 159 159 |

5 | T2T |

| Keystone 2014 [35] | RCT | § | § | § | 1.3 (0.7) | § | 5.6 (1.7) | MTX+PBO | 164 |

ADA+MTX ADA+PBO |

196 166 |

10 | T2T |

| Konijn 2017 [36] | RCT | 57 (13) | 67 | § | § | § | § | MTX+GC | 81 | MTX+SSZ+GC | 81 | 4 |

T2T Bridg. 34w |

| Markusse 2016 [37] | RCT | 54 (14) | 69 | 65 | 1.4 (0.7) | 24(§) | 4.4 (0.9)** |

MTX MTX+GC |

126 121 |

MTX+SSZ+GC INF+MTX |

133 128 |

10 |

T2T Bridg. 28w |

| Verhoeven 2018 [38] | RCT | § | § | § | § | § | § | MTX+PBO | 72 |

TCZ+MTX TCZ+PBO |

75 79 |

5 | T2T |

§(spread of) variable not available; *bDMARD-based remission induction strategy; **DAS44 (assessing 44 joints); reduced dose is 0.5 of the normal dose; RF, rheumatoid factor; HAQ, health assessment questionnaire; DAS28, disease activity score assessing 28 joints; RCT, randomized controlled trial; bridg, bridging therapy; im, intramuscular; iv, intravenous; Ada, adalimumab; BARI, baracitinib; CSA, ciclosporine; CZP, certolizumab pegol; ETN, etanercept; GC, glucocorticoid; GOL, golimumab, HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; INF, infliximab; Lef, lefunomide; MTX, methotrexate; PBO, placebo; SSZ, sulfasalazine; TCZ, tocilizumab; T2T, treat-to-target treatment strategy including step-up and step-down

Several of the 29 studies used more than 1 remission definition; in all, 46 remission definitions were used, range 1–4 per study. Most studies used at least a definition of remission where remission had to be present ≥ 1 visit within 6 to 12 months follow-up and according to one of our remission outcome definitions; we will describe the results based on these outcomes (Table 1). Seventeen studies defined remission as DAS28 < 2.6, 12 studies used the Boolean remission definition, 7 studies used CDAI ≤ 2.8, and 10 studies used SDAI ≤ 3.3; results are described separately below. Overall, for 32 of the 46 remission definitions (70%), a statistically significant effect in favor of remission induction strategy was found.

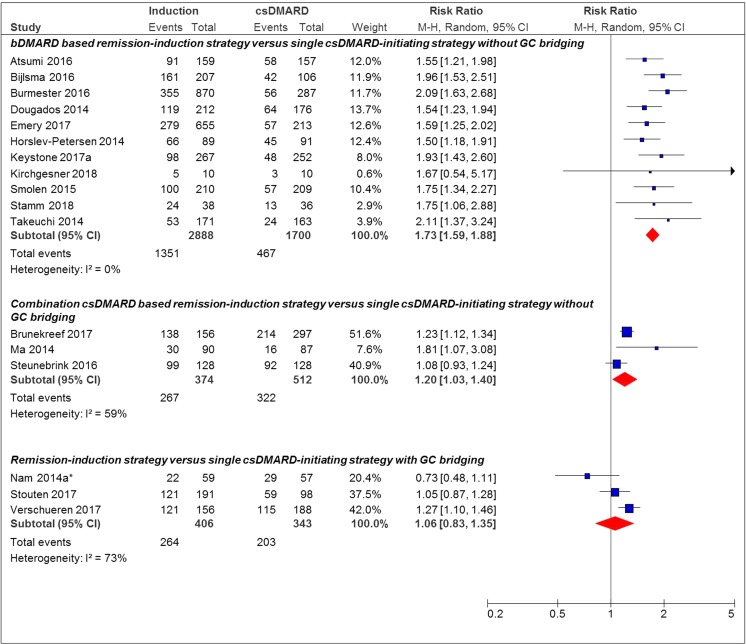

DAS28-Based Remission

When DAS28 was used for remission definition, 13/17 (76%) studies showed a statistically significant effect in favor of the remission induction strategy (Fig. 1). The pooled RR of achieving remission for strategies using a bDMARD in the remission induction strategy compared to the single csDMARD-initiating strategy without GC bridging was 1.73 [95%CI 1.59–1.88] versus 1.20 [95%CI 1.03–1.40] for studies which used a combination csDMARD-based remission induction strategy compared to the single csDMARD-initiating strategy without GC bridging. For studies using GC bridging in the single csDMARD-initiating strategy, no statistically significant additional effect for the remission induction strategy was found (pooled RR 1.06 [95% CI 0.83–1.35]). One of them used a bDMARD in the remission induction strategy arm. [29] One cohort study only provided an OR for achieving remission in patients treated with a remission induction strategy compared to a single csDMARD-initiating strategy, with or without additional GC use (without sufficient information to calculate an RR). Results were in favor of the remission induction strategy (OR 1.82 [95%CI 1.01–3.29]) [25].

Fig. 1.

Forest plot of DAS28 remission outcome in individual studies comparing remission induction strategies with single csDMARD-initiating strategies. DAS28 remission, DAS28 < 2.6; induction, remission induction strategy arm; csDMARD, single csDMARD-initiating strategy arm; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; Random, random effect; *bDMARD-based remission induction strategy. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

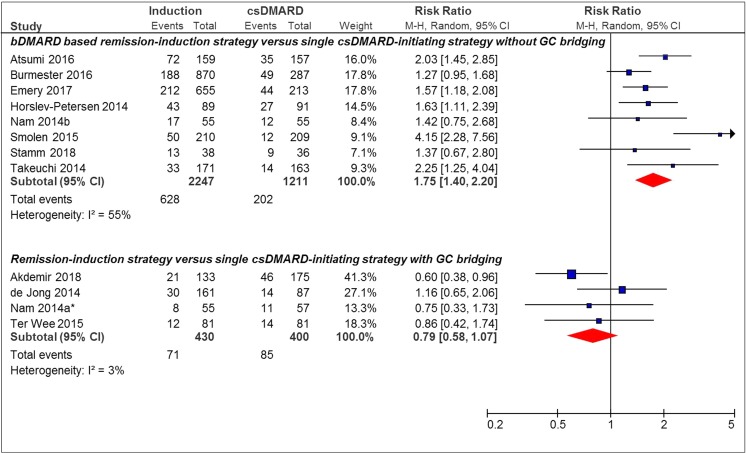

Boolean-Based Remission

For Boolean remission, 5/12 (42%) studies showed a statistically significant effect in favor of the remission induction strategy. The pooled RR of achieving Boolean remission for the bDMARD-based remission induction strategy compared to the single csDMARD-initiating strategy without GC bridging was 1.75 [95%CI 1.40–2.20], versus 0.79 [95% CI 0.58–1.07] for the remission induction strategy (1/5 bDMARD use in the remission induction strategy) [29] compared to the single csDMARD-initiating strategy with GC bridging (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of Boolean remission outcome in individual studies comparing remission induction strategies with single csDMARD-initiating strategies. Boolean remission—tender joint count ≤ 1, swollen joint count ≤ 1, CRP ≤ 1 mg/dL, patient global assessment ≤ 1 (on a 0–10 scale); induction, remission induction strategy arm; csDMARD, single csDMARD-initiating strategy arm; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; random, random effect; *bDMARD-based remission induction strategy. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

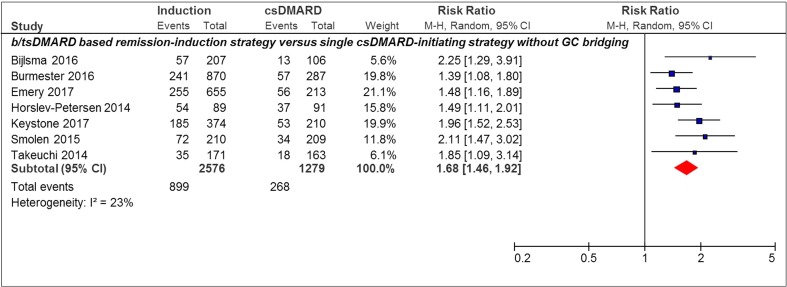

CDAI-Based Remission

Only studies with b/tsDMARD use in the remission induction strategy versus single csDMARD-initiating strategy without GC bridging were included in the analysis for CDAI remission. All studies (7/7, 100%) showed a statistical significant effect in favor of the remission induction strategy arm. The pooled RR of achieving CDAI remission was 1.68 [95%CI 1.46–1.92] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of CDAI remission outcome in individual studies comparing remission induction strategies with single csDMARD-initiating strategies. CDAI remission, CDAI ≤ 2.8; induction, remission induction strategy arm; csDMARD, single csDMARD-initiating strategy arm; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; random, random effect. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

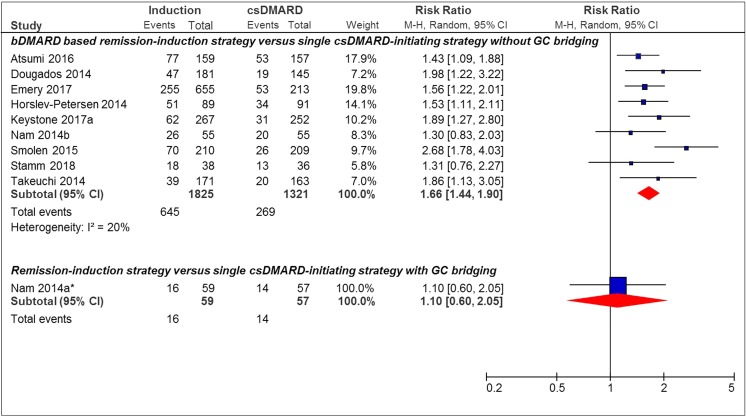

SDAI-Based Remission

Nine studies with bDMARD use in the remission induction strategy arm versus single csDMARD-initiating strategy without GC bridging, and one study using a bDMARD-based remission induction strategy versus a single csDMARD-initiating strategy with GC bridging were included in the analysis for SDAI remission [29]. A significant effect in favor of the remission induction strategy was found in 7/10 (70%) studies (Fig. 4). The pooled RR of achieving SDAI remission was 1.66 [95%CI 1.44–1.90] for bDMARD use in the remission induction strategy arm versus the single csDMARD-initiating strategy without GC bridging arm. And for the single study where a remission induction strategy was compared to a single csDMARD-initiating strategy with GC bridging, this was 1.10 [95%CI 0.60–2.05].

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of SDAI remission outcome in individual studies comparing remission induction strategies with single csDMARD-initiating strategies. SDAI remission, SDAI ≤ 3.3; induction, remission induction strategy arm; csDMARD, single csDMARD-initiating strategy arm; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; random, random effect; *bDMARD-based remission induction strategy

Symptom Duration

Regarding symptom duration, six studies started treatment “within the window of opportunity” (symptom duration ≤ 3 months). Another nine studies started treatment “outside the window of opportunity” (symptom duration > 3 months; range 4–10 months). All studies reported the DAS28-based remission outcome, and 11/15 (73%) showed a statistically significant effect in favor of the remission induction strategy. The pooled RR of achieving remission for strategies within the window of opportunity was 1.43 [95%CI 1.15–1.77] versus 1.44 [95%CI 1.12–1.86] for studies outside the window of opportunity. Five studies used a single csDMARD-initiating strategy with GC bridging (i.e., two studies within and three studies outside; Supplementary figure 2).

Longer Term Effectiveness of Remission Induction Strategies Started in Early RA

We found six studies evaluating the effect of a remission induction strategy versus a single csDMARD-initiating strategy on the long term (4 to 10 years). In four studies, DAS remission was more often achieved in the initial remission induction strategy compared to the single csDMARD-initiating strategy over time [33–35, 37]. In the remission induction strategy arm, Boolean remission, as well as SDAI remission, was less often achieved in one of two studies with no difference in the other, compared to the single csDMARD-initiating strategy arm [34, 36]. No difference was found for CDAI remission, which was reported in only one study [34]. One study reported data about SR, which was achieved in almost all patients over time, without differences between the different strategy arms [38]. However, using (s)DFR as outcome, differences were shown in favor of the remission induction strategies [37, 38]. No differences were found for radiographic progression over time between the different strategies [33–35, 37]. Details of these studies can be found in Table 1.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias of the included studies was overall low. In general, 26/29 studies were RCTs, the remaining 3 were cohort studies. An overview of the risk of bias assessment is shown in Supplementary table 1. In the studies evaluating long-term effects of a remission induction strategy, after the initial RCT [33–38], treatment was according to the treating physician and standard care, without detailed information on the initial trial and attrition, prohibiting to fully assess all items of the risk of bias assessment. Further, moderate/high risk of bias was present in the seven studies evaluating short-term effects [23, 25–27, 30–32].

Discussion

The current meta-analysis shows that a remission induction strategy is more effective compared to a single csDMARD-initiating strategy, possible specifically for bDMARD-based remission induction strategies. However, this superior effect over single csDMARD-initiating strategy is limited and is not statistically significant, if patients are treated initially also with GCs, short-term as “bridging therapy.” Longer term follow-up studies showed conflicting results, but a more favorable outcome with regard to (s)DFR for the remission induction strategy may be present.

No overall pooled effect estimate was given as studies were highly heterogeneous in study design regarding, e.g., specific drug regimen and remission outcome used. We therefore defined groups of more homogeneous studies based on specific remission outcomes and characteristics of drug regimen. Results within these groups show that heterogeneity is typically low, and therefore we pooled the effect estimates. However, in some of these groups, heterogeneity was moderate, based on differences in study design, medical treatment, risk of bias and/or patient characteristics (I2 > 50%, see Figs. 1 and 2).

One surprising finding was that the added value of a remission induction strategy was found to be limited and non-statistically significant when compared to a single csDMARD-initiating strategy with GC bridging therapy. This may suggest that the current early start of therapy, including a treat to target approach with swift step-up treatment adjustments, achieves already very good results when the initial delay in treatment effect is covered by the bridging therapy.

Contrary to expectation, similar beneficial outcomes for patients treated within the window of opportunity were found when compared with those for patients treated outside the window of opportunity. However, only a limited number of studies reported data on symptom duration which is notoriously difficult to define, and our study was not specifically designed to test the window of opportunity hypothesis. Outside of our study, in some papers, a difference in effectiveness of treatment has been shown in favor of patients treated within the window of opportunity [2, 39].

In general, long-term effectiveness outcomes were not different between a remission induction strategy and a single csDMARD-initiating strategy probably due to the widely applied treat to target principle [1].

Results of our systematic literature review are in line with an earlier performed systematic literature review, which included only remission induction strategies using a b/tsDMARD in the experimental arm [40]. We, uniquely include also combination csDMARD-based remission induction strategy arms, providing results applicable also for countries with limited availability of bDMARDs. Besides, we evaluated several established remission definitions according to validated disease activity indices and the Boolean definition [1].

No data on radiographic progression was reported, because of the limited study duration of most included studies; even over 2 years, radiographic progression is absent or modest at most in treat to target studies in early RA [41, 42]. Only some of the long-term extension studies reported on radiographic progression, but did not show any statistically significant differences.

The majority of all included studies, i.e., 20/29 (69%), were RCTs with no to moderate risk of bias. The longer term follow-up studies were follow ups of RCTs, in which the effectiveness was maintained, indicating the quality of keeping to the treat to target principle.

Conclusions

Remission induction strategies initiated in early RA patients are more effective in achieving remission compared to single csDMARD-initiating strategies. However, their benefit compared to that of a single csDMARD-initiating therapy strategy with GC bridging seems to be limited.

Electronic supplementary material

Flowchart of included studies (JPG 59 kb)

Forest plot of DAS remission outcome in each individual study in which patients were treated within the window of opportunity (symptom duration ≤ 3 months) and treated outside the window of opportunity (symptom duration > 3 months). (JPG 148 kb)

Quality assessment of individual studies (DOCX 17 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank M. de Hair (MdH) for her valuable input in this project during the initial phase.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Lafeber reports grants from Roche, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Bijlsma reports grants from Pfizer, grants from Merck Sharp & Dohme, grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, grants from AbbVie, grants from Roche, outside the submitted work.

Dr. van Laar reports grants from Arthrogen, grants from MSD, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees from BMS, grants from Astra Zeneca, grants from Roche-Genentech, outside the submitted work.

M.M.A. Verhoeven, P.M.J. Welsing, J. Tekstra and J.W.G. Jacobs declare they have no conflicts to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Rheumatoid Arthritis

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major importance

- 1.Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, Nam J, Ramiro S, Voshaar M, van Vollenhoven R, Aletaha D, Aringer M, Boers M, Buckley CD, Buttgereit F, Bykerk V, Cardiel M, Combe B, Cutolo M, van Eijk-Hustings Y, Emery P, Finckh A, Gabay C, Gomez-Reino J, Gossec L, Gottenberg JE, Hazes JMW, Huizinga T, Jani M, Karateev D, Kouloumas M, Kvien T, Li Z, Mariette X, McInnes I, Mysler E, Nash P, Pavelka K, Poór G, Richez C, van Riel P, Rubbert-Roth A, Saag K, da Silva J, Stamm T, Takeuchi T, Westhovens R, de Wit M, van der Heijde D. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:960–977. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raza K, Filer A. The therapeutic window of opportunity in rheumatoid arthritis: does it ever close? Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:793–794. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1–26. doi: 10.1002/art.39480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bijlsma JWJ, Welsing PMJ, Woodworth TG, et al. Early rheumatoid arthritis treated with tocilizumab, methotrexate, or their combination (U-Act-Early): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, strategy trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10042):343–355. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Chen Y-C, Greenwald M, Drescher E, Liu J, Beattie S, Witt S, de la Torre I, Gaich C, Rooney T, Schlichting D, de Bono S, Emery P. Baricitinib in patients with inadequate response or intolerance to conventional synthetic DMARDs: results from the RA-BUILD study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:88–95. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teitsma XM, Jacobs JWG, Welsing PMJ, de Jong PHP, Hazes JMW, Weel AEAM, Pethö-Schramm A, Borm MEA, van Laar JM, Lafeber FPJG, Bijlsma JWJ. Inadequate response to treat-to-target methotrexate therapy in patients with new-onset rheumatoid arthritis: development and validation of clinical predictors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1261–1267. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ajeganova S, Huizinga T. Sustained remission in rheumatoid arthritis: latest evidence and clinical considerations. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2017;9:249–262. doi: 10.1177/1759720X17720366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions : explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011; 2011. Available from www.handbook.cochrane.org.

- 11.Atsumi T, Yamamoto K, Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, Ishiguro N, Tanaka Y, Eguchi K, Watanabe A, Origasa H, Yasuda S, Yamanishi Y, Kita Y, Matsubara T, Iwamoto M, Shoji T, Okada T, van der Heijde D, Miyasaka N, Koike T. The first double-blind, randomised, parallel-group certolizumab pegol study in methotrexate-naive early rheumatoid arthritis patients with poor prognostic factors, C-OPERA, shows inhibition of radiographic progression. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:75–83. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burmester GR, Rigby WF, van Vollenhoven RF, et al. Tocilizumab in early progressive rheumatoid arthritis: FUNCTION, a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1081–1091. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dougados MR, van der Heijde DM, Brault Y, Koenig AS, Logeart IS. When to adjust therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after initiation of etanercept plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone: findings from a randomized study (COMET) J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1922–1934. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emery P, Bingham CO, 3rd, Burmester GR, et al. Certolizumab pegol in combination with dose-optimised methotrexate in DMARD-naïve patients with early, active rheumatoid arthritis with poor prognostic factors: 1-year results from C-EARLY, a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:96–104. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-209057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horslev-Petersen K, Hetland ML, Junker P, et al. Adalimumab added to a treat-to-target strategy with methotrexate and intra-articular triamcinolone in early rheumatoid arthritis increased remission rates, function and quality of life. The OPERA Study: an investigator-initiated, randomised, double-blind. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:654–661. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keystone EC, Dougados M, Ruderman EM, et al. Time to achieve moderate/low disease activity and remission in RA patients on baricitinib compared to a dalimumab, methotrexate, and placebo[abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69(suppl 10).

- 17.Keystone EC, Breedveld FC, van der Heijde D, et al. Achieving comprehensive disease control in patients with early and established rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone. RMD Open. 2017;3:e000445. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirchgesner T, Vande Berg B, Sokolova T, et al. Evaluation of MRI RAMRIS score and clinical response in patients with ACPA positive undifferentiated arthritistreated with infliximab versus placebo. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1764. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nam JL, Villeneuve E, Hensor EMA, Wakefield RJ, Conaghan PG, Green MJ, Gough A, Quinn M, Reece R, Cox SR, Buch MH, van der Heijde DM, Emery P. A randomised controlled trial of etanercept and methotrexate to induce remission in early inflammatory arthritis: the EMPIRE trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1027–1036. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smolen JS, Wollenhaupt J, Gomez-Reino JJ, Grassi W, Gaillez C,Poncet C, et al. Attainment and characteristics of clinical remission according to the new ACR-EULAR criteria in abatacept-treated patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: new analyses from the Abatacept study to gauge remission and joint damage progression in methotrexate (MTX)-naive patients with Early E rosive rheumatoid arthritis (AGREE). Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Stamm TA, Machold KP, Aletaha D, Alasti F, Lipsky P, Pisetsky D, Landewe R, van der Heijde D, Sepriano A, Aringer M, Boumpas D, Burmester G, Cutolo M, Ebner W, Graninger W, Huizinga T, Schett G, Schulze-Koops H, Tak PP, Martin-Mola E, Breedveld F, Smolen J. Induction of sustained remission in early inflammatory arthritis with the combination of infliximab plus methotrexate: the DINORA trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20:174. doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1667-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, Ishiguro N, Miyasaka N, Mukai M, Matsubara T, Uchida S, Akama H, Kupper H, Arora V, Tanaka Y. Adalimumab, a human anti-TNF monoclonal antibody, outcome study for the prevention of joint damage in Japanese patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: the HOPEFUL 1 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:536–543. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brunekreef T, Bernelot Moens H. Remission induction with methotrexate step-up therapy versus combination of hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate and triamcinolone: 3 year results. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:147–148. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma MHY, Scott IC, Dahanayake C, Cope AP, Scott DL. Clinical and serological predictors of remission in rheumatoid arthritis are dependent on treatment regimen. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1298–1303. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rannio T, Asikainen J, Hannonen P, Yli-Kerttula T, Ekman P, Pirilä L, Kuusalo L, Mali M, Puurtinen-Vilkki M, Kortelainen S, Paltta J, Taimen K, Kauppi M, Laiho K, Nyrhinen S, Mäkinen H, Isomäki P, Uotila T, Aaltonen K, Kautiainen H, Sokka T. Three out of four disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug-naïve rheumatoid arthritis patients meet 28-joint disease activity score remission at 12 months: results from the FIN-ERA cohort. Scand J Rheumatol. 2017;46:425–431. doi: 10.1080/03009742.2016.1266029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steunebrink LMM, Versteeg GA, Vonkeman HE, ten Klooster PM, Kuper HH, Zijlstra TR, van Riel PLCM, van de Laar MAFJ. Initial combination therapy versus step-up therapy in treatment to the target of remission in daily clinical practice in early rheumatoid arthritis patients: results from the DREAM registry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:60. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0962-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akdemir Gülşah, Markusse Iris M, Bergstra Sytske Anne, Goekoop Robbert J, Molenaar Esmeralda T, van Groenendael Johannes H L M, Kerstens Pit J S M, Lems Willem F, Huizinga Tom W J, Allaart Cornelia F. Comparison between low disease activity or DAS remission as treatment target in patients with early active rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open. 2018;4(1):e000649. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Jong PH, Hazes JM, Han HK, Huisman M, van Zeben D, van der Lubbe PA, Gerards AH, van Schaeybroeck B, de Sonnaville PB, van Krugten MV, Luime JJ, Weel AE. Randomised comparison of initial triple DMARD therapy with methotrexate monotherapy in combination with low-dose glucocorticoid bridging therapy; 1-year data of the tREACH trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1331–1339. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nam JL, Villeneuve E, Hensor EMA, Conaghan PG, Keen HI, Buch MH, Gough AK, Green MJ, Helliwell PS, Keenan AM, Morgan AW, Quinn M, Reece R, van der Heijde DM, Wakefield RJ, Emery P. Remission induction comparing infliximab and high-dose intravenous steroid, followed by treat-to-target: a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial in new-onset, treatment-naive, rheumatoid arthritis (the IDEA study) Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:75–85. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stouten V, Joly J, De Cock D, et al. Sustained effectiveness of methotrexate with step-down glucocorticoid remission induction (cobra slim) for early rheumatoid arthritis in a treat-to-target setting: 2-year results of the carera trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:147. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.ter Wee MM, den Uyl D, Boers M, et al. Intensive combination treatment regimens, including prednisolone, are effective in treating patients with early rheumatoid arthritis regardless of additional etanercept: 1-year results of the COBRA-light open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1233–1240. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-205143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verschueren P, De Cock D, Corluy L, et al. Effectiveness of methotrexate with step-down glucocorticoid remission induction (COBRA Slim) versus other intensive treatment strategies for early rheumatoid arthritis in a treat-to-target approach: 1-year results of CareRA, a randomised pragmatic open-la. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:511–520. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergstra AS, Landewé RB, Huizinga TW, Allaart CF. Rheumatoid arthritis patients with continued low disease activity have similar outcomes over 10 years, regardless of initial therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:160. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emery P, Fleischmann RM, Strusberg I, Durez P, Nash P, Amante EJB, Churchill M, Park W, Pons-Estel B, Han C, Gathany TA, Xu S, Zhou Y, Leu JH, Hsia EC. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous golimumab in methotrexate-naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis: five-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68:744–752. doi: 10.1002/acr.22759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keystone EC, Breedveld FC, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Florentinus S, Arulmani U, Liu S, Kupper H, Kavanaugh A. Longterm effect of delaying combination therapy with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor in patients with aggressive early rheumatoid arthritis: 10-year efficacy and safety of adalimumab from the randomized controlled PREMIER trial with open-label extension. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:5–14. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Konijn NPC, van Tuyl LHD, Boers M, den Uyl D, ter Wee MM, van der Wijden LKM, Bultink IEM, Kerstens PJSM, Voskuyl AE, van Schaardenburg D, Nurmohamed MT, Lems WF. Similar efficacy and safety of initial COBRA-light and COBRA therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: 4-year results from the COBRA-light trial. Rheumatol. 2017;56:1586–1596. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Markusse IM, Akdemir G, Dirven L, Goekoop-Ruiterman YPM, van Groenendael JHLM, Han KH, Molenaar THE, le Cessie S, Lems WF, van der Lubbe PAHM, Kerstens PJSM, Peeters AJ, Ronday HK, de Sonnaville PBJ, Speyer I, Stijnen T, ten Wolde S, Huizinga TWJ, Allaart CF. Long-term outcomes of patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis after 10 years of tight controlled treatment: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:523–531. doi: 10.7326/M15-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verhoeven M, de Hair MJH, Welsing PMJ, et al. U-act-early trial 3 years follow-up. The longer effectiveness of treat-to-target strategies in early RA with tocilizumab, methotrexate, or their combination. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:560. [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Nies JAB, Tsonaka R, Gaujoux-Viala C, Fautrel B, van der Helm-van Mil AHM. Evaluating relationships between symptom duration and persistence of rheumatoid arthritis: does a window of opportunity exist? Results on the Leiden early arthritis clinic and ESPOIR cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:806–812. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh JA, Hossain A, Mudano AS, et al. Biologics or tofacitinib for people with rheumatoid arthritis naive to methotrexate: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2017:CD012657. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teitsma XM, Jacobs JWG, Welsing PMJ, Pethö-Schramm A, Borm MEA, van Laar JM, Lafeber FPJG, Bijlsma JWJ. Radiographic joint damage in early rheumatoid arthritis patients: comparing tocilizumab- and methotrexate-based treat-to-target strategies. Rheumatol. 2018;57:309–317. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steunebrink LMM, Versteeg LGA, Vonkeman HE, ten Klooster PM, Hoekstra M, van de Laar MAFJ. Radiographic progression in early rheumatoid arthritis patients following initial combination versus step-up treat-to-target therapy in daily clinical practice: results from the DREAM registry. BMC Rheumatol. 2018;2:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s41927-018-0009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Flowchart of included studies (JPG 59 kb)

Forest plot of DAS remission outcome in each individual study in which patients were treated within the window of opportunity (symptom duration ≤ 3 months) and treated outside the window of opportunity (symptom duration > 3 months). (JPG 148 kb)

Quality assessment of individual studies (DOCX 17 kb)