Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the rate of progression from seroconversion to symptomatic disease in adults infected with HIV-1, and to establish whether the background level of signs and symptoms commonly associated with HIV-1 in uninfected controls are likely to affect progression rates.

Design

Longitudinal, prospective cohort study of people infected with HIV-1 and randomly selected subjects negative for HIV-1 antibodies identified during population studies.

Setting

Study clinic with basic medical care in rural Uganda.

Subjects

275 patients infected with HIV-1 (107 prevalent cases and 168 incident cases) and 246 controls negative for HIV-1 antibodies.

Main outcome measures

Signs and symptoms of HIV disease, as determined by stages 2 and 3 of the World Health Organization clinical staging system.

Results

The median time from seroconversion to WHO stage 2 was 25.4 months and to stage 3 was 45.5 months. 43% of the participants infected with HIV-1 had signs or symptoms by two years after seroconversion. The most common clinical conditions used to define progression of disease were weight loss, mucocutaneous manifestations, bacterial infections, chronic fever, and chronic diarrhoea. Although the rates of these conditions (apart from minor weight loss) were significantly higher in the participants infected with HIV-1, they were also relatively frequent in the control group. Herpes zoster, oral candidiasis, and pulmonary tuberculosis were not common events in the control group and therefore were more indicative of infection with HIV-1.

Conclusions

Disease progression associated with infection with HIV-1 seems to be rapid in rural Uganda. This is most likely due to the high prevalence of conditions in the general population that could be taken as symptoms and signs of infection with HIV-1.

What is already known on this topic

The few studies that have reported time from seroconversion to HIV-1 symptomatic disease in poor countries suggest that this interval is shorter than in rich countries

What this study adds

Progression from seroconversion to symptomatic disease seems to be rapid in rural Africa

The apparent rapid disease progression in rural Africa is most likely to be due to the high prevalence of what could be taken as symptoms and signs of HIV-1 in the general population

Introduction

Although some studies have found that progression of disease in patients infected with HIV-1 is more rapid in African people living in sub-Saharan Africa,1–4 most studies have found rates of progression similar to those in rich countries.5–9 However, in Africa it is rare to find cohorts for whom tests negative for HIV-1 antibody and positive HIV-1 tests (and hence an estimated date of seroconversion) are documented.

We report rates of, and reasons for progression to, early symptomatic disease in adults for whom estimated dates of HIV-1 seroconversion were available in a cohort in rural Uganda. We also assessed the rates of conditions commonly associated with HIV-1 infection in participants infected with HIV-1 before they developed AIDS compared with those in participants not infected with HIV-1.

Methods

Participants and design

We established a clinical cohort in rural south western Uganda in 1990 by recruiting participants from a large study that followed the dynamics of HIV-1 infection with annual HIV-1 serosurveys of the general population.10 The cohort comprised prevalent cases of HIV-1 infection diagnosed in 1989 and 1990 and incident cases detected during annual serosurveys; we used randomly selected people who were negative for HIV-1 antibodies, as controls.11 The estimated date of seroconversion for the incident cases was taken as the midpoint between the last test negative result and first positive result for antibodies to HIV-1.

All participants gave informed written consent (signature or thumbprint), and they were reviewed by a study doctor every three months. The participants were asked about their medical history, were given a full physical examination, and underwent basic laboratory investigations. Any complaints or medical findings were investigated and treated with drugs from the World Health Organization's list of essential drugs. Participants could also attend the clinic at any time when they were ill during the study. At each routine visit, participants infected with HIV-1 were categorised according to the clinical and performance scale of the staging system for patients infected with HIV-1 proposed by the WHO (see box).12

Proposed WHO staging system for patients infected with HIV-112

Stage 1:

Asymptomatic

Persistent generalised lymphadenopathy

Stage 2:

Weight loss between 5% and 10% of body weight

Minor mucocutaneous manifestations (seborrhoeic dermatitis, prurigo, fungal nail infections, recurrent oral ulcerations, angular stomatitis)

Herpes zoster within the past five years

Recurrent upper respiratory tract infections (for example, bacterial sinusitis)

And/or

Performance scale 2: symptomatic, normal activity

Stage 3:

Weight loss >10% body weight

Unexplained chronic diarrhoea for longer than one month

Unexplained prolonged fever (intermittent or constant) for longer than one month

Oral candidiasis

Oral hairy leukoplakia

Pulmonary tuberculosis within last year

Severe bacterial infections (for example, pneumonia, pyomyositis)

And/or

Performance scale 3: bedridden for less than 50% of the day during the last month

Clinical stage 4 (AIDS):

HIV wasting syndrome*

Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia

Toxoplasmosis of the brain

Cryptosporidiosis with diarrhoea for more than one month

Cryptococcus, extrapulmonary

Cytomegalovirus infection of an organ other than liver, spleen, or lymph nodes

Herpes simplex virus infection—mucocutaneous for more than 1 month or visceral of any duration

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Any disseminated endemic mycosis

Candidiasis of the oesophagus, trachea, bronchi, or lungs

Atypical mycobacteriosis, disseminated

Non-typhoidal salmonella septicaemia

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis

Lymphoma

Kaposi's sarcoma

HIV encephalopathy†

And/or

Performance scale 4: bedridden for more than 50% of the day during last month

*Defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as weight loss of greater than 10% body weight, plus either unexplained chronic diarrhoea (greater than 1 month) or chronic weakness and unexplained prolonged fever (greater than 1 month).

†Defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as clinical findings of disabling cognitive dysfunction and/or motor dysfunction, interfering with activities of daily living, progressing over weeks to months in the absence of a concurrent illness or condition other than infection with HIV that could explain the findings.

The staff at the clinic were not aware of the HIV status of the participants. This ensured confidentiality and reduced the risk of bias in the reports. All participants were strongly encouraged to attend the HIV counselling sessions and testing facilities that were provided as part of the study.

Statistical analysis

To minimise the number of missed events when the median time from seroconversion to symptomatic disease, represented by WHO stages 2 and 3, was estimated, we included only incident cases seen within two years of their estimated date of seroconversion. The WHO staging system is hierarchical—it is assumed that once individuals have moved to a given stage, they have passed though all previous stages. Participants who had symptoms at enrolment or who progressed directly to a higher stage were considered to be left censored (the event that defined the move to the next stage happened before the date of recording). This left censoring tends to overestimates of the time from seroconversion to a given stage. We provide the proportion of individuals who were left censored for each stage so that the degree of bias can be assessed. The date of the routine appointment at which a participant was first seen with an event that defined a WHO stage was used to estimate the time between seroconversion and the patient developing symptoms.

Kaplan-Meier survival methods were used to estimate the median probabilities (and interquartile ranges) and cumulative probabilities (95% confidence intervals by Greenwood's method) for times to the various endpoints. To estimate the background level of stage defining conditions in this population, we compared the rates of conditions during follow up—from the first visit to the last visit before the patient was classified as having AIDS—for all incident cases, prevalent cases and controls by using the Mantel-Haenszel test. All analyses were performed with the STATA 6.0 statistical package. This paper reports data from 1990 to the end of 2000.

Results

By the end of 2000, 275 patients infected with HIV-1 (107 prevalent cases and 168 incident cases) and 246 controls who tested negative for HIV-1 infection had been enrolled. We enrolled more than 80% of individuals identified for selection from the large population study into the clinical cohort, and over 92% of participants living in the area were seen during 2000. Compliance rates remained high.

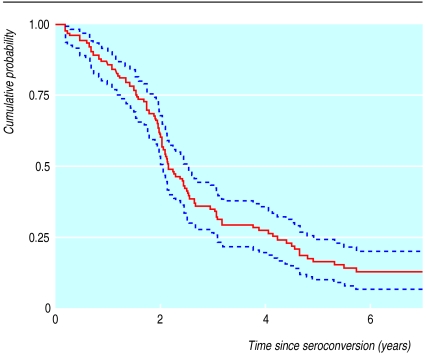

In total, 142 incident cases were seen within two years of their estimated date of seroconversion (table 1). Figure 1 shows the cumulative probabilities of remaining symptom free after seroconversion.

Table 1.

Enrolment characteristics of the incident cases infected with HIV-1, used for estimating progression times, median time from seroconversion to WHO stages 2 and 3 and reasons for progression

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| No of participants seen within two years of seroconversion | 142 |

| Men | 70 |

| Women | 72 |

| Median (IQR) age (years) | 30 (24-38) |

| Median (IQR) time between tests negative and positive for HIV antibodies (months) | 12.1 (9.8-18.0) |

| Median (IQR) time from seroconversion to enrolment (months) | 10.6 (7.3-16.8) |

| Median (IQR) follow up from seroconversion to last visit (years) | 4.2 (2.3-6.6) |

| No of patients in each WHO stage on enrolment: | |

| 1 (asymptomatic) | 123 |

| 2 (mild disease) | 12 |

| 3 (moderate disease) | 6 |

| 4 (AIDS) | 1 |

| Median (95% CI) time from seroconversion to stage 2 (months)* | 25.4 (23.9 to 29.6) |

| No (%) of patients in WHO stage 2 | 63 |

| Reasons for progression:** | |

| Minor weight loss (5-10% baseline weight) | 38 (61) |

| Minor mucocutaneous manifestations | 16 (25) |

| Herpes zoster | 9 (14) |

| Median (95% CI) time from seroconversion to stage 3 (months)† | 45.5 (36.2 to 51.3) |

| No (%) of patients in WHO stage 3 | 72 |

| Reasons for progression:** | |

| Major weight loss (>10%) | 24 (33) |

| Severe bacterial infection | 23 (32) |

| Chronic diarrhoea | 13 (18) |

| Chronic fever | 10 (14) |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 3 (4) |

| Oral candidiasis | 2 (3) |

| Oral hairy leukoplakia | 1 (1) |

IQR=interquartile range.

Using 104 subjects in stage 2: 51 progressed from stage 1; 12 were in stage 2 and 7 were in higher stages on enrolment; and 34 went straight to stages 3 or 4. Thus 53 (51%) were left censored.

Each participant could have more than one reason for progression.

Using 80 subjects in stage 3: 66 progressed from stages 1 or 2; 6 in stage 3 and 1 in stage 4 on enrolment; and 7 went straight to stage 4. Thus 14 (18%) were left censored.

The most common clinical conditions associated with disease progression were weight loss, mucocutaneous manifestations, bacterial infections, chronic fever, and chronic diarrhoea (table 1). The number of events and the rates of these and other conditions defining a WHO stage (prior to AIDS) in all participants are shown in table 2. With the exception of minor weight loss, the rates of these conditions were significantly higher in participants infected with HIV-1 than in controls, although the conditions were also relatively frequent in the control group. Herpes zoster, oral candidiasis, and pulmonary tuberculosis were not common events in the control participants, as shown by their higher rate ratios.

Table 2.

Rates of visits to study clinic by patients with conditions defining WHO stages (pre-AIDS) in participants infected with HIV-1 compared with controls negative for HIV-1 antibodies

| Infected with HIV (total

PYO=1120.2)

|

Negative for

HIV antibodies (total PYO=1336.5)

|

Rate ratio* (95% CI) | P value† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of patients | Rate (per 100 PYO) | No of patients | Rate (per 100 PYO) | ||||

| WHO stage 2: | |||||||

| Weight loss (5%-10%) | 521 | 46.5 | 551 | 41.2 | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) | 0.045 | |

| Minor mucocutaneous disease | 197 | 17.6 | 58 | 4.3 | 4.1 (3.0 to 5.4) | <0.001 | |

| Herpes zoster | 51 | 4.6 | 6 | 0.5 | 10.1 (4.4 to 28.9) | <0.001 | |

| Recurrent upper respiratory tract infection | 21 | 1.9 | 7 | 0.5 | 3.6 (1.5 to 8.4) | 0.002 | |

| WHO stage 3: | |||||||

| Weight loss >10% | 232 | 20.7 | 98 | 7.3 | 2.8 (2.2 to 3.6) | <0.001 | |

| Chronic diarrhoea | 60 | 5.4 | 22 | 1.6 | 3.3 (2.0 to 5.3) | <0.001 | |

| Prolonged fever | 56 | 5.0 | 37 | 2.8 | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.7) | 0.005 | |

| Oral candidiasis | 43 | 3.8 | 1 | 0.08 | 51.3 (7.1 to 372) | <0.001 | |

| Oral hairy leukoplakia | 6 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.08 | 7.2 (0.9 to 59.5) | 0.033 | |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 24 | 2.1 | 2 | 0.08 | 28.6 (3.9 to 212) | <0.001 | |

| Severe bacterial infection | 126 | 11.3 | 47 | 3.5 | 3.2 (2.3 to 4.5) | <0.001 | |

PYO=person years of observation.

Rate in patients infected with HIV-1 divided by rate in participants negative for HIV-1 antibodies.

Comparison of rate ratios using Mantel-Haenszel test.

Discussion

Early manifestations and progression rates of disease in patients infected with HIV-1 are particularly difficult to assess in Africa. Most reports of clinical manifestations have been in patients admitted to hospital or attending clinics; these patients are not representative of the general population, because patients tend to present late and few make it to referral centres.

Time between seroconversion and appearance of symptoms

Symptoms of infection with HIV-1 seem to developed quickly in incident cases seen within two years of their estimated date of seroconversion: only 17% of participants remained symptom-free five years after seroconversion. The median time to WHO stage 2 (25.4 months) was probably overestimated due to the effects of left censoring, but the bias for time to WHO stage 3 (45.5 months) should be negligible. Other studies in Kenya and Haiti have also reported rapid progression from seroconversion to symptomatic disease.13,14 Progression times in industrialised countries are much longer, with 78%-85% of patients infected with HIV remaining asymptomatic five years after seroconversion.15,16

Recognising progression to symptomatic disease

The most common single reason for recognising progression to symptomatic disease in our cohort was minor weight loss, but this was as common in controls who tested negative for HIV-1 antibodies as in participants infected with HIV-1. Minor mucocutaneous problems, severe bacterial infections, chronic fever, and chronic diarrhoea were also common clinical complaints that occurred before a patient was classified as having AIDS. Although participants infected with HIV-1 had significantly higher rates of these conditions, they were also frequent in the controls (see table 2). However, in agreement with other African studies,17,18 we found that herpes zoster, oral candidiasis, and pulmonary tuberculosis were highly predictive for infection with HIV-1. The small number of participants may have affected our results, but a study of women in Rwanda reported similar rates of weight loss, mucocutaneous conditions, chronic fever, and diarrhoea in groups whose test results were positive and negative for HIV-1 antibodies.6 In rich countries, the rates of these conditions, and the rate ratios, were considerably lower in groups testing positive and negative for HIV-1 antibodies.19,20

Background levels of other conditions

Most of the population in rural Uganda lives in poverty; food is often in limited supply, there is no electricity, and there is poor access to any, let alone clean, water. Malaria is endemic, and infections other than HIV, especially bacterial infections, are common. The shorter interval from seroconversion to symptomatic disease in African populations probably reflects the high background level of these conditions, rather than rapid disease progression.

CHALASANI/REX

Conclusions

The progression of disease in patients infected with HIV-1 in Africa seems to be rapid; this is most likely to be due to the high prevalence of what could be taken as symptoms and signs of infection with HIV-1 in the general population. Studies that showed rapid progression of disease in patients infected with HIV in Africa could have led to the belief that HIV disease progresses more rapidly in Africa than elsewhere.

Figure.

Cumulative probability (95% confidence intervals) of remaining symptom-free from time of seroconversion (Kaplan-Meier plot)

Acknowledgments

We thank all the staff in the study clinic and in Entebbe who supported our work. Most importantly, we thank the participants.

Footnotes

Funding: Medical Research Council and the Department for International Development.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Colebunders R, Ryder R, Francis H, Nekwei W, Bahwe Y, Lebughe I, et al. Seroconversion rate, mortality and clinical manifestations associated with the receipt of a human immunodeficiency virus-infected blood transfusion in Kinshasa, Zaire. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:450–456. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.3.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.N'Galy B, Ryder RW, Kapita B, Mwandagalirwa K, Colebunders RL, Francis H, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection among employees in an African hospital. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1123–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810273191704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whittle H, Egboga A, Todd J, Corrah T, Wilkins A, Demba E, et al. Clinical and laboratory predictors of survival in Gambian patients with symptomatic HIV-1 or HIV-2 infection. AIDS. 1992;6:685–689. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199207000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anzala OA, Nakelkerke NJD, Bwayo JJ, Holton D, Moses S, Ngugi EN, et al. Rapid progression to disease in African sex workers with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:686–689. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mann JM, Bila K, Colebunders RL, Kalemba K, Khonde N, Bosenge N, et al. Natural history of human immunodeficiency virus infection in Zaire. Lancet. 1986;ii:707–709. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leroy V, Msellati P, Lepage P, Batungwanayo J, Hitmana DG, Taelman H, et al. Four years of natural history of HIV-1 infection in African women: a prospective cohort study in Kigali (Rwanda), 1988-1993. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1995;9:415–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerlikowske KM, Katz MH, Allen S, Wolf W, Hudes HS, Karita E, et al. β2-microglobulin as a predictor of death in HIV-infected women from Kigali, Rwanda. AIDS. 1994;8:963–969. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199407000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.French N, Mujugira A, Nakiyingi J, Mulder D, Janoff EN, Gilks CF. Immunological and clinical stages in HIV-1 infected adults are comparable and provide no evidence of rapid progression but poor survival with advanced disease. J Acquir Immune Def Syndr. 1999;22:509–516. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199912150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marlink R, Kanki P, Thior I, Travers K, Eisen G, Siby T, et al. Reduced rate of disease development after HIV-2 infection as compared to HIV-1. Science. 1994;265:1587–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.7915856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamali A, Carpenter LM, Whitworth JAG, Pool R, Ruberantwari A, Ojwiya A. Seven-year trends in HIV-1 infection rates, and changes in sexual behaviour among adults in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2000;14:427–434. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgan D, Malamba S, Maude G, Okongo M, Wagner HU, Mulder D, et al. An HIV-1 natural history cohort and survival times in rural Uganda. AIDS. 1997;11:633–640. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization: acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS): interim proposal for a WHO staging system for HIV-1 infection and disease. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1990;65:221–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagelkerke NJD, Plummer FA, Holton D, Anzala AO, Manji F, Ngugi EN, et al. Transition dynamics of HIV disease in a cohort of African prostitutes: a Markov model approach. AIDS. 1990;4:743–747. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deschamps M-M, Fitzgerald DW, Pape JW, Johnson WD. HIV infection in Haiti: natural history and disease progression. AIDS. 2000;14:2515–2521. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200011100-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flegg PJ. The natural history of HIV infection: a study in Edinburgh drug users. J Infect. 1994;29:311–321. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(94)91266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee CA, Phillips AN, Elford J, Janossy G, Griffiths P, Kernoff P. Progression of HIV disease in a haemophilic cohort followed for 11 years and the effect of treatment. BMJ. 1991;303:1093–1096. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6810.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindan CP, Allen S, Serufilira A, Lifson AR, Van de Perre P, Chen-Rundle A, et al. Predictors of mortality among HIV-infected women in Kigali, Rwanda. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:320–328. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-4-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller WC, Thielman NM, Swai N, Cegielski JP, Shao J, Manyenga D, et al. Diagnosis and screening of HIV/AIDS using clinical criteria in Tanzanian adults. J Acquir Immune Def Syndr. 1995;9:408–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmberg SD, Buchbinder SP, Conley LJ. The spectrum of medical conditions and symptoms before acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in homosexual and bisexual men infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Epid. 1995;141:395–404. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brettle RP, Foreman A, Povey S. Clinical features of early HIV in the Edinburgh city cohort. Intern J AIDS STD. 1996;7:110–116. doi: 10.1258/0956462961917302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]