Abstract

Aim

The objective of this research was to estimate the dose distribution delivered by radioactive gold nanoparticles (198AuNPs or 199AuNPs) to the tumor inside the human prostate as well as to normal tissues surrounding the tumor using the Monte-Carlo N-Particle code (MCNP-6.1.1 code).

Background

Radioactive gold nanoparticles are emerging as promising agents for cancer therapy and are being investigated to treat prostate cancer in animals. In order to use them as a new therapeutic modality to treat human prostate cancer, accurate radiation dosimetry simulations are required to estimate the energy deposition in the tumor and surrounding tissue and to establish the course of therapy for the patient.

Materials and methods

A simple geometrical model of a human prostate was used, and the dose deposited by 198AuNPs or 199AuNPs to the tumor within the prostate as well as to the healthy tissue surrounding the prostate was calculated using the MCNP code. Water and A-150 TEP phantoms were used to simulate the soft and tumor tissues.

Results

The results showed that the dose due to 198AuNPs or 199AuNPs, which are distributed homogenously in the tumor, had a maximal value in the tumor region and then rapidly decreased toward the prostate–tumor interface and surrounding organs. However, the dose deposited by 198Au is significantly higher than the dose deposited by 199Au in the tumor region as well as normal tissues.

Conclusions

According to the MCNP results, 198AuNPs are a promising modality to treat prostate cancer and other cancers and 199AuNPs could be used for imaging purposes.

Keywords: Dose distribution, Radioactive gold nanoparticles, Prostate tumor, MCNP

1. Background

Prostate cancer is more commonly diagnosed than any other non-skin cancer in the United States,1 and is the second leading cause of cancer death in men.2, 3 At present, there are many different clinical modalities used to treat this malignant disease.4 Nevertheless, there has been an increasing interest in radioactive nanotechnology as a prostate cancer therapy and for imaging.5 The major reason for clinical interest in this particular application is the notion that therapeutic nanoparticles may be synthesized with a custom size, designed to match the size of the tumor microvasculature or some other feature (for a review see Cho and Krishnan6).7, 8, 9 Tailoring the nanoparticle size to individual tumor microvasculature allows oncologists to achieve optimal therapeutic payload with minimum leakage from the target site.10, 11 For instance, in our previous paper, we synthesized MGF-198AuNPs having a core size of 35 nm and the hydrodynamic size of 55 nm that can match the size of the tumor microvasculature. These radioactive gold nanoparticles were spherical, nearly mono-disperse and had a homogenous distribution.12

The neutron activation products of stable 197Au and 198Pt, shown in the reactions below

| (1) |

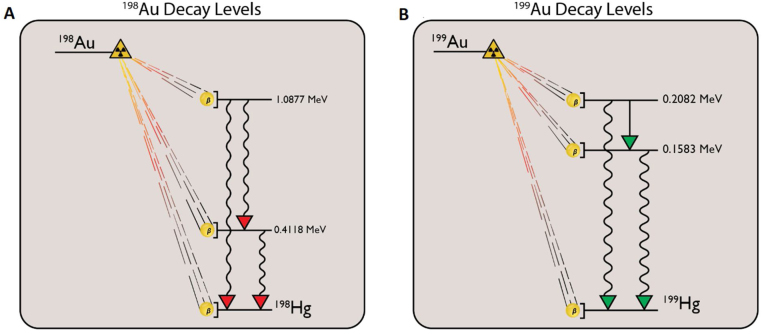

are preferred for this application due to their radioactive characteristics,13 as noted in Table 1. Note that the effective removal properties of these radionuclides are dominated by radiological decay rate, largely leaving the decay product stable mercury in the tumor. Additional properties may be found in the literature14, 15 (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Some radioactive properties of 198Au and 199Au.

| Property | 198Au | 199Au |

|---|---|---|

| Radiological half-life | 64.6842 h | 75.33 h |

| R. mean lifetime | 93.3194 h | 108.7 h |

| R. decay constant | 2.97663 s−1 | 2.556 s−1 |

| Specific activity | 9.05484 PBq g−1 | 7.735 PBq g−1 |

| Emax of β | 0.96 MeV | 0.294 MeV |

| E of γ | 0.41 MeV | 0.1584 MeV |

| Stable product | 198Hg | 199Hg |

Fig. 1.

Radio-gold decay levels: the beta decay levels are shown for both 198Au and 199Au. Note that the decay level diagrams are to scale within themselves, but not with each other. Level data was taken from Chunmei for 198Au,16 and Artna-Cohen for 199Au.17

The β-particles range is sufficiently long to deliver a high dose to kill the tumor cells within the prostate gland while being short enough to reduce a considerable radiation dose to the healthy tissues near the tumor periphery (their penetration range is up to 0.4 cm in water and A-150 tissue).18 The respective half-lives of 198Au and 199Au are long enough for radioactive gold nanoparticles to saturate the tumor and deposit radiation dose.19 Conversely, the half-lives are short enough to decay the radioisotopes into stable daughter products via the reactions listed below:15

| (2) |

Indeed, 198Au has been used in brachytherapy application as a permanent seed implant.20 However, there is a clinical difficulty in using 198Au seeds for brachytherapy because of a resulting heterogeneous dose distribution, with a higher dose near the seeds and lower doses between them.21 Experiments have shown that the use of 198Au-nanoparticles can enable overcoming of this limitation, and that radioactive gold nanoparticles can deliver dose with a homogeneous distribution due to their small sizes.21

Before using radioactive gold nanoparticles as a new therapeutic modality to treat human prostate cancer, accurate radiation dosimetry simulations are required to estimate the energy deposition in the tumor and surrounding tissue and to establish the course of therapy for the patient. Monte-Carlo simulation is a technique that can be used to accurately estimate dose distributions within the prostate tumor as well as to the normal tissues surrounding the tumor.22

The objective of this research was to use the MCNP-6.1.1 code to build a simple geometrical model of a human prostate, and then to estimate the dose due to radioactive gold nanoparticles (198AuNPs or 199AuNPs) to the tumor inside the human prostate as well as to the normal tissues surrounding the tumor (using water and A-150 TEP computational phantoms). The models, simulations and the results are described in the following sections.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Physical model

Only a few researchers have used Monte-Carlo simulation to estimate the dose distribution deposited by radioactive nanoparticles and they have built simple geometrical models of the tumors and organs to estimate the dose distribution.23, 24 For instance, Bouchat et al.23 hypothesized that the solid tumor was a sphere which was subdivided into small cubes, and then they calculated the doses deposited by radioactive 90Y-nanoparticles of 5 nm diameter inside and around the spherical solid tumor using MCNPX. Nuttens et al.24 have also built a simple geometrical model for the MCNP simulation. They assumed the solid tumor was a sphere with a radius R, and then they estimated the dose distribution inside the tumor and in the surrounding healthy tissues.

In the present study as guided by the previous work,23, 24 a simple geometrical model of the tumor, prostate, bladder, and rectum was built. The prostate gland and solid tumor were assumed to be spherical. The radius of the prostate was taken as 2 cm with a tumor of radius 0.4 cm inside (the size of the prostate was taken according to the actual size of the human prostate).25 Since the urethra passes through the center of the prostate, the tumor was assumed to be (left) off-center within the prostate (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of phantom geometry: schematic representation of the simple geometrical model of the tumor, human prostate, and organs at risk. The geometry shown in this figure is not drawn to scale.

Radioactive gold nanoparticles were assumed to be homogeneously distributed inside the tumor tissue. For prostate cancer beta therapy, the organs at risk for excess dose are the prostate (healthy tissue), the bladder, and the rectum. The organs at risk were assumed to be spherical with radii of 3.5 cm, and 1.5 cm, respectively (the size of the bladder and rectum were taken according to the actual size of the human bladder and rectum).26 Water and A-150 TEP phantoms were used to simulate the soft as well as the tumor tissues. More sophisticated phantoms could be considered, but using a simplified geometry initially would allow an easier experimental validation.

2.2. MCNP model

Dosimetry calculations for radioactive gold nanoparticles were performed using the MCNP code (version 6.1.1). Specifically, this code was used to estimate the dose distribution of 198Au and 199Au nanoparticles from a homogenously distributed source both inside the tumor and in the surrounding healthy tissues of the human. This approach allowed the computation of dose as a function of position.

Both 198Au and 199Au isotopes emit gamma and beta radiation which deposit dose in tissue. In each decay of a 198Au or 199Au nucleus, 1 beta and 1 gamma are emitted. Both of these particles deposit energy in tissue. However, the beta particle deposits most or all of its energy in the local tissue due to its short range and high linear energy transfer; there will be some gamma interactions locally, but the vast majority of the photons will be transported outwards.

In this work, the gammas and betas emitted per decay of 198Au and 199Au and their intensities were used to estimate the dose distribution via the MCNP simulation model. Only those betas with energies higher than 15 eV are counted for the simulations, as MCNP-6 does not support general beta interactions at low energies, as each material requires a separate interaction model (in any case, these low energies are less important for dose estimations). Photons were tracked and tallied at energies above 15 eV.

The source was assumed to be spherical with a radius similar to that of the tumor because radioactive nanoparticles are assumed to spread homogenously throughout tumor tissues. Computationally, an MCNP F6 tally and spherical mesh tally (SMESH) were used to estimate the dose distribution of both betas and gammas that are emitted by the gold nanoparticles and deposited within the tumor and neighboring healthy tissues of the bladder and rectum.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. MCNP simulations of 198AuNPs

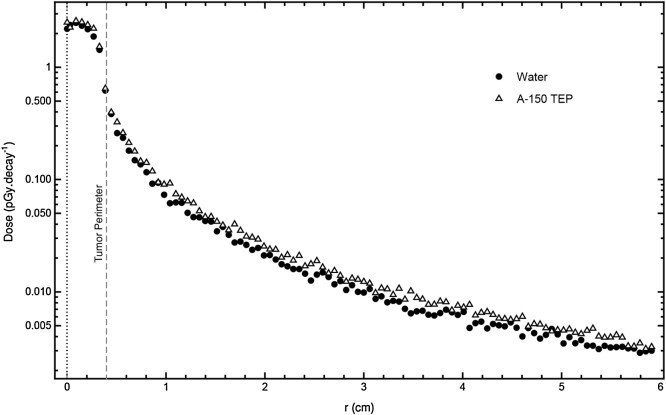

198Au emits both gammas and betas. Fig. 3 shows the dose profile as a function of distance. The maximum dose was delivered at the center of the tumor (r = 0) and then decreased with distance moving from the center to the outer edges.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of deposited dose as a function of distance r from the tumor center for 198AuNP.

Distribution of deposited dose as a function of distance r from the tumor center for 198AuNPs. r = 0 refers to the center of the tumor, r = 0.4 cm refers to the periphery of the tumor, r = 2 refers to the periphery of the prostate, and r = 2.5 cm refers to the periphery of the bladder or rectum that is close to the prostate. Water and A-150 phantoms were used.

Fig. 3 represents the dose delivered by each decay of 198Au to tissues. In this figure, it can be observed that the dose distribution curves of both water and A-150 phantoms are similar and have nearly the same values. As can be seen, the dose at the center of the tumor is approximately 9 pGy/decay and decreases rapidly to 1.1 pGy/decay at the periphery of the tumor, whereas the dose at the periphery of the prostate is only 0.08 pGy/decay. Furthermore, the dose decreases to 0.04 pGy/decay at the periphery of the bladder or rectum that is close to the prostate, whereas the dose at the center of the bladder is only 0.01 pGy/decay.

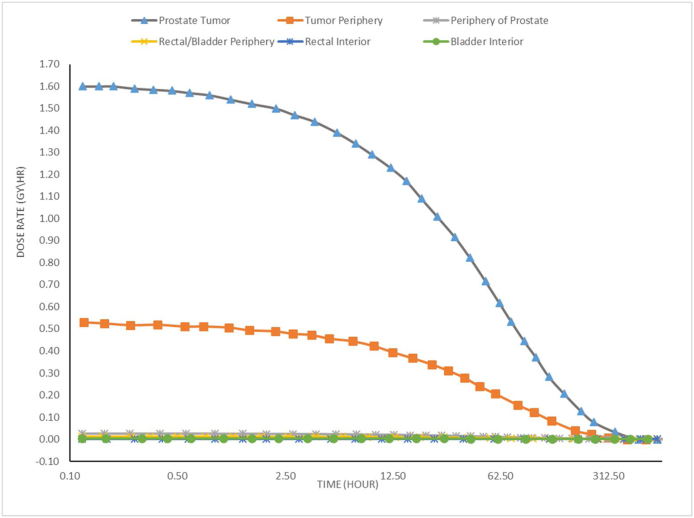

The ratio of deposited dose in the tumor center to deposited dose in the tumor periphery is (9/1.1) = 8.18. Likewise, the ratio of deposited dose in the tumor center to deposited dose in the prostate periphery is (9/0.08) = 112.5. In addition, the ratio of deposited dose in the center of the tumor to deposited dose in the center of the bladder is (9/0.01) = 900. If we suppose that a patient was injected in the tumor with radioactive 198AuNPs that have an initial activity of 10 mCi (3.7 × 108 Bq), then the deposited dose rates would be 12 Gy/h at the center of the tumor, 1.46 Gy/h at the periphery of the tumor, and 0.1 Gy/h at the periphery of the prostate, as can be seen in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Dose rate to the tumor and to other normal tissues after administration of 10 mCi of 198AuNPs.

3.2. MCNP simulations of 199AuNPs

Simulation results showed that the dose was the highest at the center of the tumor and decreased significantly toward the periphery of the tumor and normal tissues. The dose distribution of 199Au is like that of 198Au. However, the dose deposited by 199Au is significantly lower than the dose deposited by 198Au. It is known that the energies of betas and gammas that are emitted by 199Au are lower than those that are emitted by 198Au. Hence, the dose deposited by 199Au must be lower than the dose deposited by 198Au, even though they have the same activity, and MCNP results are in good agreement with this.

Distribution of deposited dose as a function of distance r from the tumor center for 199AuNPs. r = 0 refers to the center of the tumor, r = 0.4 cm refers to the periphery of the tumor, r = 2 cm refers to the periphery of the prostate, and r = 2.5 cm refers to the periphery of the bladder or rectum that is close to the prostate. Water and A-150 TEP phantoms were used.

Fig. 5 represents the dose delivered by each decay of 199Au to tissues. It can be seen from this figure that the dose distribution curves of both water and A-150 TEP phantoms are similar and have nearly the same values in the tumor region but beyond that, the dose in the A-150 TEP phantom is slightly higher than the dose in the water phantom. The dose distribution curve in the water phantom will be explained below.

Fig. 5.

Distribution of deposited dose as a function of radial distance from the tumor center for 199AuNPs.

In Fig. 5, it is observed that the dose at the center of the tumor is approximately 1.2 pGy/decay and decreases rapidly to 0.4 pGy/decay at the periphery of the tumor, whereas the dose at the periphery of the prostate is only 0.02 pGy/decay. Furthermore, the dose decreases to reach only 0.01 pGy/decay at the periphery of the bladder or rectum that is close to the prostate, whereas the dose at the center of the bladder is only 0.001 pGy/decay. As in the previous section, we consider the scenario in which a patient is injected in the tumor with 10 mCi of 199AuNPs. Then, the deposited dose rate would be 1.6 Gy/h at the center of the tumor, 0.53 Gy/h at the periphery of the tumor, and 0.026 Gy/h at the periphery of the prostate as can be seen in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Dose rate to the tumor and to other normal tissues after administration of 10 mCi of 199AuNPs.

The results show that 198AuNPs/199AuNPs, which are distributed homogenously in the tumor, deposit most of their energy in the tumor region. The dose deposited by 198Au is significantly higher than the dose deposited by 199Au at the tumor region as well as normal tissues. Table 2 summarizes results for the deposited dose by 198Au/199Au nanoparticles in tumor, prostate, and normal organs in a human model.

Table 2.

The computed initial dose rate from nanoparticle administration in the tumor and surrounding tissues, renormalized for a 10 mCi source.

| Tissue | Dose rate (Gy/h) |

|

|---|---|---|

| 198AuNPs | 199AuNPs | |

| Center of tumor | 12 | 1.6 |

| Periphery of tumor | 1.46 | 0.53 |

| Periphery of prostate | 0.1 | 0.026 |

| Periphery of bladder and rectum that is close to the prostate | 0.053 | 0.013 |

| Center of bladder | 0.013 | 0.0013 |

| Center of rectum | 0.026 | 0.004 |

In our previous research,12 we performed detailed in vivo evaluations demonstrating tumor retention and therapeutic efficacy and the overall effectiveness of radioactive gold nanoparticles (MGF-198AuNPs) as unprecedented therapeutic probes for the treatment of prostate tumors using prostate tumor-bearing SCID mice. The results showed that most of the injected dose of radioactive gold nanoparticles was retained in the prostate tumor up to 24 h, and there was minimal/no leakage of these radioactive gold nanoparticles, away from the tumor site, causing no adverse accumulation in non-target organs at different time points. Also, the results proved that radioactive gold nanoparticles are capable of reducing the volume of the tumor in comparison with the control group.

The results of our previous animal study and the current MCNP simulations, both show that the radioactive gold nanoparticles (198AuNPs) deposit most of their energy within the prostate tumor site with minimal or no leakage to the surrounding normal tissues. The results of the current study further show that the radioactive gold nanoparticles could be transferred from the animal experiments to the clinical trials and hold potential as a new therapeutic modality to treat human prostate cancer.

4. Conclusions

The MCNP simulations showed that the radioactive gold nanoparticles deposited most of their energy within the tumor while depositing marginal amounts of energy within organs at risk, such as the bladder and rectum. Since the 198Au decay energy is high and its radiation energy would be delivered to the tumor site without harming normal tissues or organs at risk, it can be concluded that 198AuNPs are a promising modality to treat prostate cancer and other cancers. As expected due to the low beta and gamma energy for 199Au, MCNP calculations showed that doses to the organs at risk (rectum and bladder) were acceptable and less than the reported value of maximum tolerated dose. Therefore, 199AuNPs could be used for imaging purposes.

Authors’ contribution

Loyalka conceived the original idea. AL-Yasiri designed the model and the computational framework. White performed the MCNP simulations. AL-Yasiri and White contributed to the interpretation of the results. AL-Yasiri wrote the manuscript with support from White, Loyalka, and Katti. Loyalka and Katti supervised the project and gave the final approval of the version to be submitted. All authors analyzed and discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript preparation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

Acknowledgements

During the course of this research, Amal Al-Yasiri was supported by the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research in Iraq, and the Nuclear Science and Engineering Institute. Nathan White was supported by a GAANN grant from the U.S. Department of Education and a grant from the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

References

- 1.Brawley O.W. Prostate cancer epidemiology in the United States. World J Urol. 2012;30(2):195–200. doi: 10.1007/s00345-012-0824-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R., Naishadham D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsavaler L., Shapero M.H., Morkowski S., Laus R. Trp-p8, a novel prostate-specific gene, is up-regulated in prostate cancer and other malignancies and shares high homology with transient receptor potential calcium channel proteins. Cancer Res. 2001;61(9):3760–3769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pugh T.J., Nguyen B.-N., Kanke J.E., Johnson J.L., Hoffman K.E. Radiation therapy modalities in prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2013;11(4):414–421. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lammers T., Kiessling F., Hennink W.E., Storm G. Nanotheranostics and image-guided drug delivery: current concepts and future directions. Mol Pharm. 2010;7(6):1899–1912. doi: 10.1021/mp100228v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho S.H., Krishnan S. Taylor & Francis; 2013. Cancer nanotechnology: principles and applications in radiation oncology. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lammers T., Aime S., Hennink W.E., Storm G., Kiessling F. Theranostic nanomedicine. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44(10):1029–1038. doi: 10.1021/ar200019c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nyström A.M., Wooley K.L. The importance of chemistry in creating well-defined nanoscopic embedded therapeutics: devices capable of the dual functions of imaging and therapy. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44(10):969–978. doi: 10.1021/ar200097k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kievit F.M., Zhang M. Cancer nanotheranostics: improving imaging and therapy by targeted delivery across biological barriers. Adv Mater. 2011;23(36) doi: 10.1002/adma.201102313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shukla R., Chanda N., Zambre A. Laminin receptor specific therapeutic gold nanoparticles (198AuNP-EGCg) show efficacy in treating prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(31):12426–12431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121174109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satija J., Gupta U., Jain N.K. Pharmaceutical and biomedical potential of surface engineered dendrimers. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2007;24(3) doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v24.i3.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Yasiri A., Khoobchandani M., Cutler C. Mangiferin functionalized radioactive gold nanoparticles (MGF-198 AuNPs) in prostate tumor therapy: green nanotechnology for production, in vivo tumor retention and evaluation of therapeutic efficacy. Dalton Trans. 2017;46(42):14561–14571. doi: 10.1039/c7dt00383h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katti K., Kannan R., Katti K. Hybrid gold nanoparticles in molecular imaging and radiotherapy. Czech J Phys. 2006;56(1):D23–D34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell J.A., Durlacher J.J. Clinical usefulness of radioactive gold 198. J Indiana State Med Assoc. 1955;48(4):374–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Atomic Energy Agency . IAEA; Austria: January 2003. TECDOC-1340, Manual for reactor produced radioisotopes. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chunmei Z. Nuclear data sheets update for A = 197. Nucl Data Sheets. 1995;76(3):399–456. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Artna-Cohen A. Nuclear data sheets update for A = 199. Nucl Data Sheets. 1994;72(2):297–354. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Attix F.H. Wiley-VCH; 2004. Introduction to radiological physics and radiation dosimetry. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kannan R., Zambre A., Chanda N. Functionalized radioactive gold nanoparticles in tumor therapy. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2012;4(1):42–51. doi: 10.1002/wnan.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kehwar T. Use of Cesium-131 radioactive seeds in prostate permanent implants. J Med Phys. 2009;34(4):191. doi: 10.4103/0971-6203.56077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Axiak-Bechtel S.M., Upendran A., Lattimer J.C. Gum arabic-coated radioactive gold nanoparticles cause no short-term local or systemic toxicity in the clinically relevant canine model of prostate cancer. Int J Nanomed. 2014;9:5001. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S67333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duggan D.M. Improved radial dose function estimation using current version MCNP Monte-Carlo simulation: model 6711 and ISC3500 125 I brachytherapy sources. Appl Radiat Isot. 2004;61(6):1443–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2004.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouchat V., Nuttens V., Lucas S. Radioimmunotherapy with radioactive nanoparticles: first results of dosimetry for vascularized and necrosed solid tumors. Med Phys. 2007;34(11):4504–4513. doi: 10.1118/1.2791038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuttens V., Wéra A.-C., Bouchat V., Lucas S. Determination of biological vector characteristics and nanoparticle dimensions for radioimmunotherapy with radioactive nanoparticles. Appl Radiat Isot. 2008;66(2):168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee C.H., Akin-Olugbade O., Kirschenbaum A. Overview of prostate anatomy, histology, and pathology. Endocrinol Metab Clin. 2011;40(3):565–575. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.https://www.webmd.com/urinary-incontinence-oab/picture-of-the-bladder#1 [last seen 26.10.18].