Abstract

Background: Researchers and other key stakeholders in biobanking often do not have a thorough understanding of the true costs and challenges associated with initiating, running, and maintaining a biobank. The National Cancer Institute's Biorepositories and Biospecimen Research Branch (BBRB) commissioned the Biobanking Financial Sustainability survey to better understand the challenges that biobanks face in supporting ongoing operations. A series of interviews with biobanking managers and an international focus group session informed the content of the survey.

Methods: The design of the survey included five main sections, each containing questions related to primary topics as follows: general demographics, operations, funding sources, costs, and financial challenges. While the survey focused on financial issues and challenges, it also explored staffing and strategic planning as these issues relate to the sustainability of operations and financial support. U.S. and international biobanks were included in the survey.

Results: Biobanks in general are dependent on public funding and most biobanks do not have formal plans for the long-term stewardship of their collections. Respondents are working at a critical level of personnel and are not in a position to further reduce staffing. Smaller biobanks in particular need assistance in defining reasonable cost recovery user fees for biospecimens and related services.

Conclusions: The survey results highlight several issues that are important for long-term biobank sustainability. It is critical to prepare for such issues as effective biobanking practices have increasingly been recognized as a key component for the advancement of precision medicine.

Keywords: biobanking, biobank, economics, biobanking economics, financial sustainability, repositories

Introduction

The United States (U.S.) National Institutes of Health (NIH) funds a large variety of biospecimen collections in biobanks and biorepositories across the U.S., both in its intramural program and among extramural grantees and contractors.1,2 The biobanks support clinical trials as well as epidemiologic, basic, and translational research programs. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) manages one of the largest of the NIH biobanking programs, with millions of samples stored on the NIH campus and in large contract biobanks near Washington, DC.3 Many NCI grantees in the U.S. also manage biobanks of various sizes.4

Traditionally, academic and government biobanks have been funded through central institutional or departmental budgets, often with little attention paid to the cost of their development or operation. This approach can lead to inefficient economic practices and a general lack of accountability for effective management of biospecimen collections.5 During 2008–2011, the NCI Biorepositories and Biospecimen Research Branch6 (BBRB) performed a comprehensive investigation into the economics and business planning of biobanking, which resulted in a Journal of the National Cancer Institute (JNCI)7 Monograph. The monograph included planning surveys and background research and contained two articles concerning “biobankonomics.”8,9 These articles outlined various aspects of determining the costs of starting and operating a complex biospecimen program, developing a cost recovery program, and estimating the economic benefits of standardizing biobank operations through the implementation of best practices and cost-effective practices. The JNCI articles became the starting point for additional work in the area of biobanking economics. In the years since publication of the JNCI Monograph, many other studies have been conducted and published about biobanking economics.5,10–12 These studies demonstrated an increased awareness of the importance of understanding biobanking economics and sustainability in the U.S. and internationally.13–19 Biobanking conferences such as the annual meetings of the International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories20 (ISBER) and the European, Middle Eastern, and African Society for Biopreservation and Biobanking21 (ESBB) now routinely schedule sessions on biobank sustainability.22,23

As a continuum to the above studies, the NCI's BBRB commissioned the Biobanking Financial Sustainability project to conduct primary research into the challenges that biobanks face in sustaining the funding needed to support current operations. A survey was designed during the first phase of work. The content of the survey was produced with input from biobanking managers taken from a series of interviews and an international focus group session. There were preliminary discussions on how to structure the survey with the team commissioned to conduct it as well as in a workshop at a meeting in Europe with biobanking colleagues with a variety of related expertise. The survey was approved by the White House Office of Management and Budget and executed online.

Materials and Methods

The Financial Biobank Sustainability Survey (Supplementary Data; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/bio) was conducted from February to May 2014 by Life Data Systems, Inc. (LDS), a contractor to the NCI. The study was approved by the White House Office of Management and Budget under Control Number 0925–0679. The survey included five main sections, each containing questions related to the primary topics covered in the survey, including general demographics, operations, funding sources, costs, and financial challenges. Each section included approximately 10–15 questions presented to respondents in a web-based electronic form. For some questions, there was more than one possible answer, and some questions were answered in part. The survey also contained additional demographic questions specifically tailored to U.S. and international biobanks. These region-specific sections were presented to respondents after they identified their biobank as domestic or international on the general demographics form.

Invitations were sent to approximately 350 U.S. domestic and 150 international biobanking contacts, with a recommendation to invitees that they forward the invitation to colleagues within their personal networks. In addition, the survey was promoted on social networking sites, on the ISBER website, and on various biobanking-related listservs. The survey was designed with a self-registration process, enabling organizations that were not in the original contact list to self-register and participate.

The contact list was initially developed using a list provided by the NCI and supplemented by additional research that identified a variety of biobank registry sites and registries for research projects that utilized a biobank for their work. These additional biobanks were added to the contact list. To ensure that there was no selection bias in the response data, no known contact in the invitation process was excluded.

Results

Invitations and response rates

A total of approximately 12% responses were received, including 7% from the U.S. and 5% from international biobanks, representing a response rate typical for this type of survey and target population. Not all respondents were able to complete all sections of the survey. A total of 6% of surveys were fully completed, half of which were from the U.S. and half from international biobanks. The remaining surveys varied in the portions that were completed, with most containing only one or two incomplete answers.

Feedback from respondents who did not complete the survey indicated that some of the requested information was not readily available or required additional analysis to be completed on time. Other respondents indicated that they would not be able to complete the survey due to competing obligations at their biobank, but that they would provide as much information as possible in the time available.

Geographic distribution

Biobanks from 32% of U.S. states responded to the survey. The invitation process was not designed to favor geographic coverage, but rather invitations were sent with the intention of including as many respondents as possible. Although biobanks were invited without regard to their location, respondents were primarily located on the east and west coast, which was probably indicative of the denser populations of research institutions and biobanks in these locations. The highest number of international responses came from Canada, where the greatest number of invitations per non-U.S. country was sent. Notably, responses were received from several countries that did not receive invitations, including Luxembourg, Latvia, and Sweden. These respondents learned of the survey by professional referral.

Biobank age and affiliations

The majority of the survey respondents were associated with health care providers or part of a clinical research organization and came from more experienced biobanking organizations. Approximately, half of the survey respondents indicated that their biobank has been in operation for longer than 10 years. Only five responses were received from biobanks in operation for less than 3 years, including four domestic and one international.

Life cycle

While the length of time in operation is one indicator of where a biobank may be in its overall life cycle, respondents were asked to self-identify their phase of operation by selecting an option given below:

Start-up: Staff is putting the biobank in operation. There is no collection or distribution of specimens at this time.

Build Up: Biobank is operational. Collection has started, but there has been no specimen distribution.

Operate: Stable collection and distribution of specimens have started.

Expand: Distribution of specimens has started, and the collection processes are expanding. The biobank may be pursuing new users.

Shut-down was a fifth option that was not a factor in the analyses and therefore not further discussed. The categorization of phases was intended to provide a more descriptive view of the maturity of each respondent's biobank and further described in Supplementary Figure 1.

Accreditation and certification

The majority of the respondents indicated that their biobank was not currently accredited. However, 44% of these biobanks reported that they are planning to participate in the Biorepository Accreditation Program offered by the College of American Pathologists.24,25 In addition, these biobanks are actively pursuing or planning to obtain certification, particularly ISO 9001, a set of international quality management standards related to biobanking, which can lead to certification.26–28

Specimen holdings

Most of the survey respondents were biobanks with a sizeable number of biospecimens. As shown in Supplementary Figure 2, biobanks were grouped according to their phase in operation and number of biospecimens collected. Additional data in Figures 1A and 2B also incorporate the number of biospecimens (size) in the analysis. The nomenclature used is Small (1–100,000 biospecimens), Medium (100,001–500,000 biospecimens), and Large (> 500,000 biospecimens).

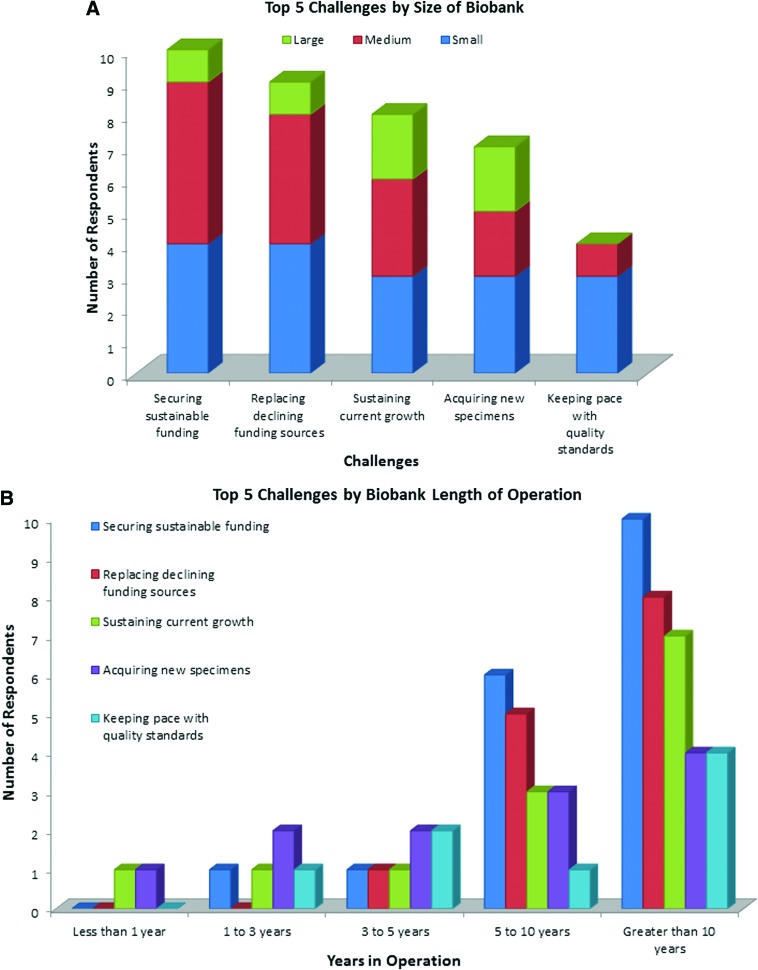

FIG. 1.

Top five challenges. (A) Distribution by challenge and biobank size. When viewing the top five critical challenges in light of the size of the biobank, most of the larger biobanks were concerned with “sustaining current growth” and “acquiring new specimens” (A). None of the largest biobanks considered “keeping pace with quality standards” as a high-priority challenge. The greatest number of medium-sized biobanks was most concerned with “securing sustainable funding” and “replacing declining funding sources”. Small biobanks were relatively uniform in their selection of the five top challenges. Some biobanks did not report the information required to determine the size of the biobank and therefore were not included. (B) The top five challenges according to biobank age. The most frequently chosen challenges for biobanks that have been in operation, the longest (>5 years) were “securing sustainable funding” and “replacing funding sources”. The main challenges for biobanks that have been in operation for less than 3 years were “sustaining current growth” and “acquiring new specimens.” In the 3–5-year range, and as the biobank continues to be in operation for a longer period, sustainable funding and replacing existing funding becomes a much more critical challenge. Color images are available online.

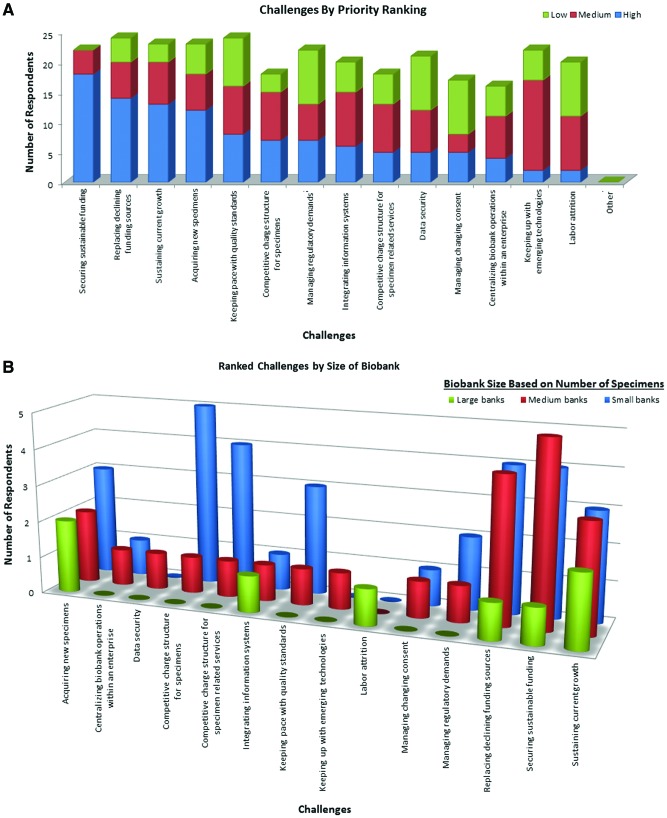

FIG. 2.

Ranked challenges. (A) Distribution by ranked challenge. There was a general agreement that funding and expanding biospecimen collections (left most four bars) are medium- or high-priority challenges for most respondents, while issues such as labor attrition, consents, and technology, (right most bars) are primarily viewed as medium or low priority. Only one challenge listed, managing changing consent processes, was rated with a low priority by more than half the respondents. (B) Large biobanks identified relatively few challenges, citing only 6 of the 14 possible challenges as important, which may be due, in part, to the relatively small number of large biobanks among the respondents. Biobanks of all sizes frequently cite growth and funding as challenges. Small biobanks cited three challenges much more frequently than medium and large biobanks. These three challenges include establishing competitive charges for specimens, charging for services, and keeping pace with new technology. Of these, the challenge indicated as most critical for small biobanks was to establish a competitive charge structure for specimen-related services. While this challenge is important to small biobanks, it is not one of the top five ranked challenges for all biobanks. Color images are available online.

Specific findings

The following sections review specific study findings related to challenges, staffing, stewardship responsibility, funding sources, and cost information from individuals who completed the survey. Survey participants were asked to indicate the criticality of the challenges that their biobank currently faces or anticipates facing in the next 12 months. The following rating scale was provided:

High: This is a critical issue

Medium: This is a challenge, but of moderate difficulty

Low: This is a challenge, but there is an approach to resolve it

Respondents could choose and rate as many challenges as they wished to report. The five most frequently chosen challenges rated as critical are shown in Figure 1A and B and were as follows: securing sustainable funding; replacing declining funding sources; sustaining current growth; acquiring new specimens; and keeping pace with quality standards.

The challenge to sustain funding is important for new biobanks to plan for as they develop their strategic plan and establish their operating charter with their host institution. A host organization may be, for example, the clinical center in which the biobank is located, the clinical or research department, or a nonprofit patient support organization. They can expect to face funding challenges after 3 years in operation. Since new funding sources take time to develop, it may be in their best interest to plan to cultivate new funding sources after their first year of operation.

Ranked challenges

Figures 2A and B show the range of challenges assigned by the biobanks ranked by priority and by biobank size, respectively. In preparatory interviews, biobanks volunteered the consent issue as a common and chronic challenge. Managing consent processes is usually a subject of vigorous discussion in biobanking conferences and forums, but was difficult for respondents to prioritize in the short term in light of the competing challenges of funding, growth, and sustained operations. Furthermore, there are key differences between small and larger biobanks that are obfuscated when only looking at the top five high-ranked challenges.

Direct and indirect cost comparison

Biobanking sizing by budget

The survey included questions about costs and budgets. Using these data, biobanks that responded were grouped by the size of their operational costs. Three categories were used for the analysis:

Small: Biobanks with operational budgets of less than $400,000

Medium: Biobanks with budgets equal to or greater than $400,000 and less than $2,000,000

Large: Biobanks with budgets equal to or greater than $2,000,000

As Table 1 indicates, the three categories demonstrated that as the operational budget increases, the percentage of direct labor decreases.

Table 1.

Direct Labor Versus Operational Budget

| Operational cost category | Average operational costs | Average direct labor | Direct labor% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small (< $400,000) | $220,115 | $147,567 | 67.0% |

| Medium ($400,000–$2,000,000) | $781,740 | $428,808 | 54.9% |

| Large (> $2,000,000) | $11,000,000 | $3,800,000 | 34.5% |

Biobanks were grouped based on the size of their operational costs.

The same holds true when looking at the direct labor percentages against the length in operation as shown in Table 2, where the respondents' average operational and direct labor costs as well as the direct labor percentages are indicated. The average proportion of the operating budget spent on direct labor for biobanks, categorized by the number of years in operation in the four different age ranges, is shown. In general, after 3 years, the direct labor costs decreased by approximately 40% or more. One reason for such a phenomenon could be because larger biobanks, and those that have been in operation longer, can be expected to have a much greater investment in infrastructure such as freezers and therefore have greater overall capital equipment costs. While staffing does appear to scale up with both the size and age of the biobank as it grows over time, the rate of staffing growth does not appear to be as closely related to length in operation or overall age when compared to the capital costs. This corroborates information gathered in presurvey interviews. An efficient and skilled staff can manage a moderately growing biobank's collection, storage, and distribution processes for years as long as these processes, the funding, and the user base remain relatively stable. Significant changes in staffing levels would be needed to handle a larger demand for specimens or to support services that would provide new sources of funding, such as information-based specimen services or other contract-based specimen services.

Table 2.

Operational and Direct Labor Costs

| Years in operation | Average operational costs | Average direct labor | Direct labor% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 year | — | — | — |

| 1–3 years | $750,000 | $650,000 | 86.7% |

| 3–5 years | $250,000 | $112,500 | 45.0% |

| 5–10 years | $497,724 | $297,481 | 59.8% |

| Greater than 10 years | $1,823,587 | $730,434 | 40.1% |

The exact operational and labor costs and the direct labor percentages are shown.

Sustainability strategies

Sustainability is a critical issue for biobanks of all sizes and ages.13–19 The survey offered three common choices for managing short-term budgetary issues: deferring acquisitions of new capital equipment, reducing the scale of operations, and reducing staff. Respondents could select any or all three options. Responses were evenly distributed between deferring acquisitions of new capital equipment and reducing operations. Notably, none of the respondents indicated that they would expect to reduce staff to compensate for a budget shortfall. Individual conversations with biobanks who participated in the survey indicated that reductions in staffing are much more disruptive in the biobanking arena than in other business areas. In addition, training and experience represent significant human resource investments that are difficult to evaluate precisely, but that biobanking teams are very reluctant to abandon.

Direct biobank and support staff

The responses concerning staffing show that, in particular, the smallest and largest biobanks employ a significant contingent of part-time staff, 35% and 39% respectively. It might be expected that reductions in part-time staff would be a common means of bridging budget shortfalls. However, our presurvey interviews indicated that most biobanking management teams felt that this would be ill advised. Even part-time staff members are highly skilled and take a significant amount of time to train. Consequently, reduction in staff would be greatly disruptive to effective operations, and therefore, respondents universally preferred other means of bridging budget gaps.

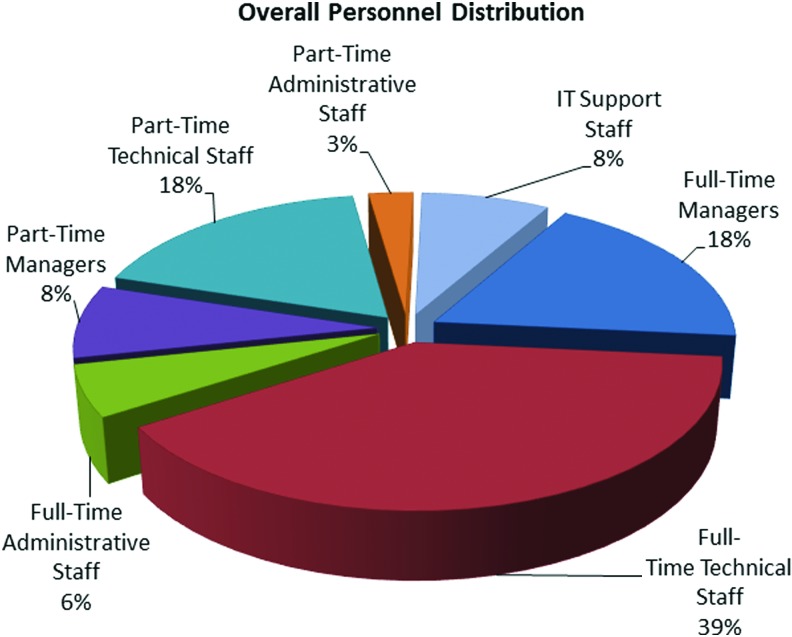

Figure 3 shows a breakdown of the typical staffing profile for the 8% of biobanks that reported personnel distributions. While several biobanks reported large staffs (>30), the vast majority of biobanks were much smaller (five to eight). With teams of a smaller size, it is easy to understand the reluctance to reduce staff, as these biobanks would generally have little spare capacity to remove staff and successfully maintain operations. In addition to the loss of the investment in skills and expertise, staff reductions require a reallocation of tasks and responsibilities that can have an enormous impact on effectiveness and morale and could lead to subsequent resignations. While the newest biobanks (<1-year-old) employ a small number of full-time staff only, all biobanks older than 1 year consistently reported that between 32% and 41% of their overall staffing are part-time employees.

FIG. 3.

Overall personnel distribution. The typical staffing profile for biobanks that reported personnel distributions is shown. The majority of staff members are full-time or part-time technical employees. Managers, administrative staff, and IT support combined account for only 25% of overall staffing. Two biobanks reported that they rely entirely on full-time staffing. Color images are available online.

Stewardship responsibility

Stewardship, also called custodianship or legacy planning, is an important best practice for biobanks. The NCI Best Practices for Biospecimen Resources provide a set of custodianship recommendations to assure that biobanks are prepared for decision-making about the fate of their collections if faced with the loss of significant funding support, or other circumstances that threaten the survival of their collections.29 Responses to stewardship for each funding source were divided on the subject of overall responsibility for long-term stewardship of the specimen collections. The majority (72% of total responses) indicated that the responsibility stays with the original sponsor(s) of each biobank. A large number of biobanks that have been in operation for 5 years or more would still hold the original sponsor responsible for the long-term stewardship of their biobank. For new biobanks creating a strategic plan, or for those revising such a plan, stewardship responsibility should be explicitly addressed.

Sources of funding most important to biobanks

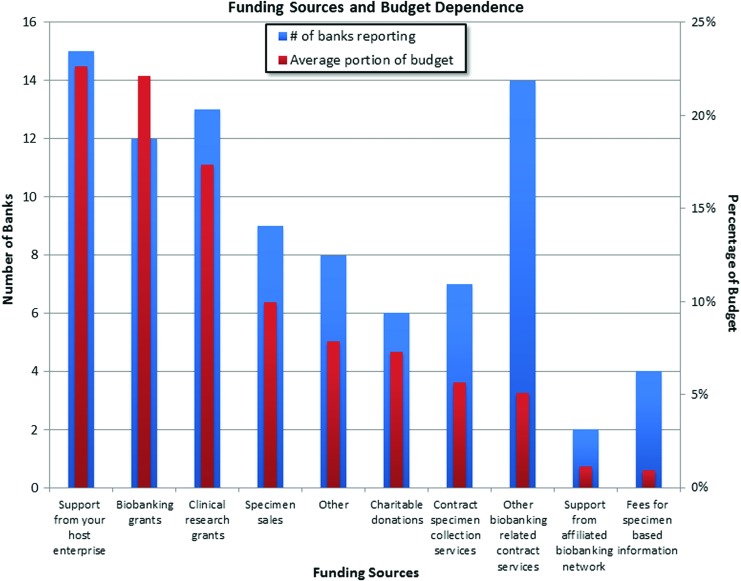

Respondents reported that managers spend a significant amount of time maintaining existing funding, while simultaneously identifying new funding sources. Figure 4 shows an analysis of the types of funding sources that the respondents use and the degree to which their budgets depend on each type.

FIG. 4.

Most biobanks (15 respondents) rely on an average of 23% of their budget to be funded from their host enterprise. Biobanking and clinical research grants were reported as similarly common sources of funding, which also contribute to a large portion of the budget for many biobanks. A large number of biobanks reported that they generate funding by providing biobanking services for a fee. While the average indicated that only 5% of the budget comes from biobanking-related services, a small subset of biobanks (5) reported that a much larger portion of their budgets come from such services, ranging from 17% to as much as 39%. Likewise, a few biobanks (3) reported that a larger percentage of their overall budget comes from contract-related specimen collection services, ranging from 25% to 50%. Finally, a small number of biobanks (4) reported that they generate a significant portion, 10%, of their budget from specimen-based information. The blue bars reflect the number of biobanks who report that a portion of their funding comes from the given source. The red bars reflect the average portion of a biobank's budget that comes from that source. Color images are available online.

According to the survey results, 22% of the sites were completely dependent on public funding, while another 42% were at least partially dependent on public funding sources. The remaining 36% reported no dependence on public funding. Sites with partial public funding had a budget nearly double the size of the biobanks that are completely dependent on public funding.

The survey requested respondents' budgets of the current year, previous year, and the operational budget projected for the following year. Well over three-quarters of the biobanks reported growing or stable budgets for the reported 3-year horizon. Most reported growing budgets, with an overall average of a 9% growth per year. It is encouraging that only 13% reported a declining budget (data not shown).

Information technology costs

In terms of information technology (IT) costs, new biobanks and those operating in the 5–10-year range have an IT investment level that is typical for full or semiautomated administrative workflows, as occurs in most biobanks. It appears that an increased IT investment was reported in the 3–5-year range. However, the biobanks in this category also had the lowest reported average operational cost. The largest biobanks report a very low IT investment. Strikingly, the average annual IT costs consistently ranged from $32,000 to $80,000 for a population of biobanks, whose average budgets range from $250,000 to $2,500,000 (Table 3). Thus, these IT investment levels appear to be good estimates for general budget projections.

Table 3.

Operational and Information Technology Costs

| Years in operation | Average operational costs | Average IT costs | IT% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 year | — | — | — |

| 1–3 years | $750,000 | $80,000 | 10.7% |

| 3–5 years | $250,000 | $57,500 | 23.0% |

| 5–10 years | $354,800 | $32,820 | 9.3% |

| Greater than 10 years | $2,239,215 | $59,367 | 2.7% |

New biobanks and those operating in the 5-10-year range have an IT investment level that is typical for full- or semiautomated administrative workflows as occurs in most biobanks. An increased IT investment is reported in the 3-5-year range, although biobanks in this category also had the lowest reported average operational cost. The largest biobanks report a very low proportional IT investment.

IT, information technology.

Discussion

The Biobanking Financial Sustainability project produced a variety of insights into the current state of biobanking both in the U.S. and internationally. While the survey focused on financial issues and challenges, it also explored staffing and strategic planning as these issues related to the sustainability of operations and financial support. Findings in each of these areas are summarized as follows:

Biobanking is critically dependent on public funding

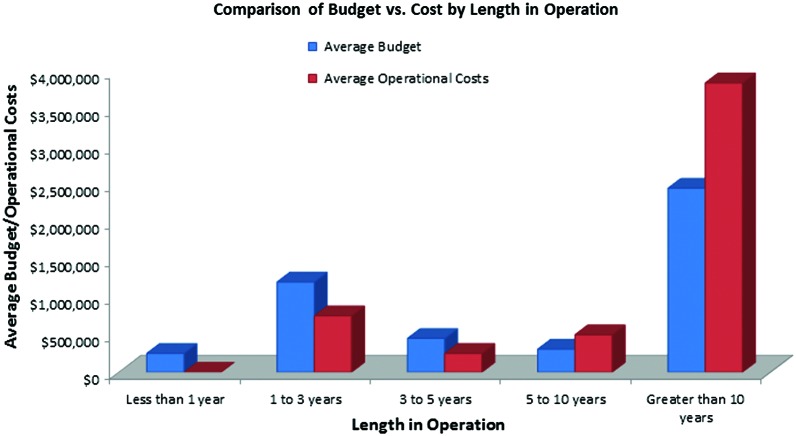

Based on the information collected in this survey, the majority of biobanks are largely dependent on publicly provided research funding and on their host organizations for on-going support, a situation that may likely continue in the foreseeable future. A minority of biobanks have generated significant revenue from specimen-related services of various kinds. As shown in Figure 5, newer biobanks appear to have a budget surplus, older biobanks (>5 years) have a deficit, and biobanks older than 10 years operate at a significant deficit. While there is evidence that biobanks are transitioning to new models of financial support, the rate of transition may be hampered by economic factors, such as difficulties in establishing competitive service fee schedules as reported by new biobanks. Public funding will be important to increasing specimen supplies and improving specimen quality. It is notable that most international respondents reported that they are funded through their national health programs, which may be a more stable and direct source of funding when compared to U.S. biobanks' dependence on publicly funded clinical research.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of budget vs. cost by length in operation. The reported operational costs were compared to the reported operational budgets, categorized by biobank age. The blue bars reflect the average budget, while the red bars reflect the average operational costs. Color images are available online.

Long-term stewardship of specimen collections is not addressed

Most biobanks do not have formal plans for the long-term stewardship of their collections. The availability of their specimen collections is entirely dependent on ongoing combined support from public research funding and their host organizations, which in turn are also largely dependent on publicly funded research programs. Short-term reductions in public funding could result in the closure of many biobanks. Without plans for stewardship of biospecimen collections, such samples could be discarded and impede progress in future clinical research. As an example, two of the biobanks, which registered for the survey, reported that they were closing, one of which was a rather sudden event and completed in less than 2 months. The disposition of the collections from these biobanks is not known.

Current literature in biobanking lacks sufficient information that describes a mechanism to handle the legacy of a collection in terms of policy or best practices. Historically, the legacy phase that, for example, follows the end of collections, expired funds, or project closure has not been considered during the planning and implementation phases of a biobank's existence. In the context of limited funds or failed mixed-model funding coupled with the time, expense, and resources required to build a biobank, it is critical to plan for the legacy of a collection and its associated data. It is perhaps even more critical when considering the ethical obligation to aptly use precious material donated for research.30–32

There is an opportunity to address some of the special needs of small/start-up biobanks

A number of smaller biobanks voiced a need for special assistance in defining competitive pricing for specimens and specimen-related services. Notably, as part of a separate biobanking economics project, the NCI released the Biobank Economic Modeling Tool (BEMT), an online financial planning tool for biobanking.33,34 The BEMT includes financial forecasting capabilities as well as the opportunity for users to browse anonymized survey results from comparable biobanks.

Human resources appear to be operating at a critical level

As noted earlier, none of the respondents indicated that they would consider staff reductions as a means to accommodate a short-term budgetary deficit. Along with comments from volunteer respondents, it appears that biobanks are operating at critical staffing levels that cannot be feasibly cut. This factor compounds the rather precarious dependence of U.S. biobanks on public funding. Specifically, continuance of specimen collection and maintenance of key technical personnel who are critical to the operation of the biobank is largely tied to public funding.

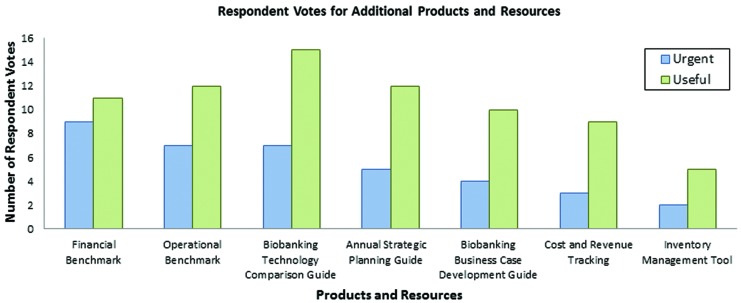

Useful follow-up work as viewed by respondents

Respondents were asked to consider what additional products and resources they would find useful by selecting any of a set of possible items and identifying the usefulness and urgency of the selected item. Figure 6 shows respondent preferences for additional products and resources, where a financial benchmark was viewed as one of the most urgent needs. An Operational Benchmark and a Biobanking Technology Guide, however, ranked as the most useful.

FIG. 6.

Respondent votes for additional products and resources. The products and resources shown had received the most “votes” by respondents. The blue bars indicate items that respondents found would currently be of most urgent need, while the green bars identify items that would currently be most useful in their current stage of operation. Color images are available online.

The findings of this survey, as well as other recent published work in the areas of biobanking economics and sustainability,5,9,13,18 indicate that issues in biobank development, management, and operations are coming to the forefront. As biobanks become even more important resources for the advancement of precision medicine, the business of biobanking has become as critical an aspect of best practices as the technical and ethical/regulatory standards that have dominated the field to date. It is now recognized that, with the introduction of business-related standards into basic and clinical research practice, the costs and economic impact of implementing such standards must be part of each biobank's strategic planning. It is important that all biobanks, especially those in the planning and development stages, make financial planning a priority. This and other recent studies of biobank cost recovery and sustainability support public funding as a critical component of an overall business plan.13,17

Supplementary Material

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Eiseman E, Haga SB. Handbook of Human Tissue Sources: A National Resource of Human Tissue Samples. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Henderson GE, Cadigan RJ, Edwards TP, et al. Characterizing biobank organizations in the U.S.: Results from a national survey. Genome Med 2013;5:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Cancer Institute Research Resources. Available at: https://resresources.nci.nih.gov/resources Accessed 23 August 2018

- 4. Carrick DM, Mette E, Hoyle B, et al. The use of biospecimens in population-based research: A review of the National Cancer Institute's Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences grant portfolio. Biopreserv Biobank 2014;12:240–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vaught J. Economics: The neglected “omics” of biobanking. Biopreserv Biobank 2013;11:259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. NCI Biorepositories and Biospecimen Research Branch. Available at: http://biospecimens.cancer.gov/default.asp Accessed 23 August 2018

- 7. Human specimen biobanking and the NCI: The scientific basis of biospecimen quality standards for post-genomic medicine. Available at: http://jncimono.oxfordjournals.org/content/2011/42.toc Accessed 23 April 2018

- 8. Rogers J, Carolin T, Vaught J, et al. Biobankonomics: A taxonomy for evaluating the economic benefits of standardized centralized human biobanking for translational research. NCI Monogr 2011;42:32–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vaught J, Rogers J, Carolin T, et al. Biobankonomics: Developing a sustainable business model approach for the formation of a human tissue biobank. NCI Monogr 2011;42:24–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Caulfield T, Borry P, Gottweis H. Industry involvement in publicly funded biobanks. Nat Rev Genet 2014;15:220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McQueen MJ, Keys JL, Bamford K, et al. The challenge of establishing, growing and sustaining a large biobank: A personal perspective. Clin Biochem 2014;47:239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Warth R, Perren A. Construction of a business model to assure financial sustainability of biobanks. Biopreserv Biobank 2014;12:389–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Albert M, Bartlett J, Johnston RN, et al. Biobank bootstrapping: Is biobank sustainability possible through cost recovery? Biopreserv Biobank 2014;12:374–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carpenter JE, Clarke CL. Biobanking sustainability-experiences of the Australian Breast Cancer Tissue Bank (ABCTB). Biopreserv Biobank 2014;12:395–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matharoo-Ball B, Thomson BJ. Nottingham Health Science Biobank: A sustainable bioresource. Biopreserv Biobank 2014;12:312–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Parry-Jones A. Assessing the financial, operational, and social sustainability of a biobank: The Wales cancer bank case study. Biopreserv Biobank 2014;12:381–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Simeon-Dubach D, Henderson MK. Sustainability in biobanking. Biopreserv Biobank 2014;12:287–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Watson PH, Nussbeck SY, Carter C, et al. A framework for biobank sustainability. Biopreserv Biobank 2014;12:60–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilson GD, D'Angelo K, Pruetz BL, et al. The challenge of sustaining a hospital-based biobank and core molecular laboratory: The Beaumont experience. Biopreserv Biobank 2014;12:306–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories. Available at: www.isber.org Accessed 23 August 2018

- 21. European Middle Eastern and African Society for Biopreservation and Biobanking. Available at: www.esbb.org Accessed 23 August 2018

- 22. ISBER 2017. Program Toronto, Canada. Available at: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.isber.org/resource/resmgr/isber_2017/ISBERFinalProgram2017.pdf Accessed 23 August 2018

- 23. ESBB 2014. Programme Leipzig Germany. Available at: www.esbb.org/leipzig/programme.html Accessed 23 August 2018

- 24. College of American Pathologists. Available at: www.cap.org Accessed 23 August 2018

- 25. CAP Biorepository Accreditation Program Checklist. Available at: www.cap.org/apps/docs/laboratory_accreditation/lap_info/biorepository_accreditation_program_checklist_sample.pdf Accessed 23 August 2018

- 26. International Organization of Standards: 9001. Quality Management. Available at: www.iso.org/iso/iso_9000 Accessed 23 August 2018

- 27. International Organization of Standardization ISO/TC 276 Biotechnology. Available at: www.iso.org/iso/home/standards_development/list_of_iso_technical_committees/iso_technical_committee.htm?commid=4514241 Accessed 23 August 2018

- 28. International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Available at: www.iso.org/iso/home.html Accessed 23 August 2018

- 29. NCI Best Practices for Biospecimen Resources. Available at: http://biospecimens.cancer.gov/bestpractices Accessed 23 August 2018

- 30. Cadigan R, Lassiter D, Haldeman K, et al. Neglected ethical issues in biobank management: Results from a U.S. study. Life Sci Soc Policy 2013;9:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matzke L, Fombonne B, Watson P, et al. Fundamental considerations for biobank legacy planning. Biopreserv Biobank 2016;14:99–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ISBER 2015 Workshop, Phoenix, Arizona USA: Legacy Planning for Biobanks and Biospecimen Collections

- 33. NCI Biospecimen Economic Modeling Tool. Available at: http://biospecimens.cancer.gov/resources/bemt.asp Accessed 23 August 2018

- 34. Odeh H, Miranda L, Rao A, et al. The Biobank Economic Modeling Tool (BEMT): Online financial planning to facilitate biobank sustainability. Biopreserv Biobank 2015;13:421–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.