Abstract

Aims

Electrical cardioversion is commonly performed to restore sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), but it is unsuccessful in 10–12% of attempts. We sought to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of a novel cardioversion protocol for this arrhythmia.

Methods and results

Consecutive elective cardioversion attempts for AF between October 2012 and July 2017 at a tertiary cardiovascular centre before (Phase I) and after (Phase II) implementing the Ottawa AF cardioversion protocol (OAFCP) as an institutional initiative in July 2015 were evaluated. The primary outcome was cardioversion success, defined as ≥2 consecutive sinus beats or atrial-paced beats in patients with implanted cardiac devices. Secondary outcomes were first shock success, sustained success (sinus or atrial-paced rhythm on 12-lead electrocardiogram prior to discharge from hospital), and procedural complications. Cardioversion was successful in 459/500 (91.8%) in Phase I compared with 386/389 (99.2%) in Phase II (P < 0.001). This improvement persisted after adjusting for age, body mass index, amiodarone use, and transthoracic impedance using modified Poisson regression [adjusted relative risk 1.08, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05–1.11; P < 0.001] and when analysed as an interrupted time series (change in level +9.5%, 95% CI 6.8–12.1%; P < 0.001). The OAFCP was also associated with greater first shock success (88.4% vs. 79.2%; P < 0.001) and sustained success (91.6% vs 84.7%; P=0.002). No serious complications occurred.

Conclusion

Implementing the OAFCP was associated with a 7.4% absolute increase in cardioversion success and increases in first shock and sustained success without serious procedural complications. Its use could safely improve cardioversion success in patients with AF.

Clinical trial number

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Cardioversion, Defibrillation, Protocol, Quality improvement

What’s new?

Electrical cardioversion is the most common method used to restore sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), but it is often unsuccessful, even with modern defibrillators. Modifiable procedural factors may contribute to cardioversion failure, yet existing guidelines disagree on the optimal cardioversion technique due to a lack of data.

In our study of 889 cardioversion attempts, implementing a four-step cardioversion protocol for AF as an institutional initiative was associated with a 7.4% absolute increase in cardioversion success (91% relative reduction in cardioversion failure) and with improvements in first shock and sustained success without any serious complications.

The proposed cardioversion protocol has the potential to improve the care of patients with AF.

Introduction

Electrical cardioversion (ECV) is frequently used to restore sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF),1 but is unsuccessful in 10–12% of attempts.2,3 Despite being increasingly performed,1 existing guidelines provide limited evidence-based direction on how to maximize ECV success. Current European Society of Cardiology guidelines explicitly encourage positioning electrodes in an anteroposterior configuration.4 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society recommendations suggest starting with a ‘higher-energy shock’ and, in cases of ECV failure, re-attempting ECV using different electrode positioning (e.g. changing from anteroposterior to anterolateral) or applying pressure to the electrodes.5 The 2010 International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation consensus recommendations state that placing electrodes in an anterolateral position is reasonable, whereas the anteroposterior approach is an ‘acceptable alternative’ and that there is insufficient evidence to make specific recommendations on energy levels or energy escalation strategies using biphasic defibrillators for AF.6 Indeed, existing recommendations are predominantly based on a small number of studies using monophasic waveform defibrillators,7,8 which are now rarely used.1,4,5 The value of these strategies in contemporary practice is less clear and, in some instances, has been challenged.2,9

The paucity of evidence and the degree of ambiguity in existing guidelines likely contribute to the high variability in ECV technique observed, including in electrode placement, initial shock energy used, rate of energy escalation, and application of pressure to electrodes.1,10 Thus, identifying and adopting optimal ECV techniques have the potential to substantially improve patient care. We, therefore, developed and implemented an ECV protocol for AF then evaluated its effectiveness and safety in real-world, contemporary practice.

Methods

The Ottawa AF cardioversion protocol

Details of the development of the Ottawa AF cardioversion protocol (OAFCP) have been published.10 In brief, the protocol was developed in four stages. A full literature review of ECV techniques was performed by two authors (F.D.R. and D.H.B.). The summarized data were presented to the steering committee for discussion and voting. An experimental model was then used to determine the optimal method of applying force to self-adhesive electrodes using handheld paddles. A negative correlation was observed between the force applied to electrodes placed in an anterolateral configuration and transthoracic impedance (TTI), with 80% of the total reduction in TTI achieved with 8 kg force (∼80 N). Prompting physicians with a ‘push-up’ force analogy was found to be most effective in achieving this force.10 The steering committee unanimously approved the final version of the protocol, which was then reviewed by an independent panel of experienced cardiologists.

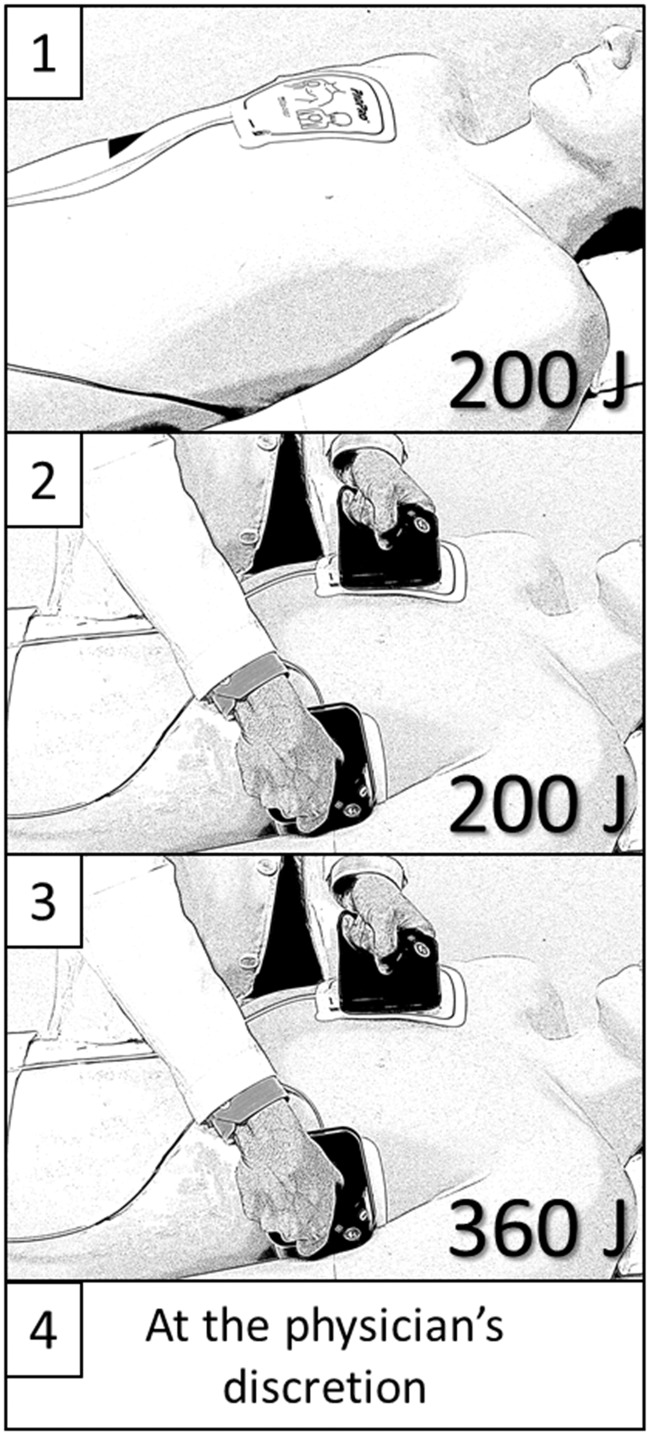

The OAFCP consists of four sequential steps: (Step 1) 200 J shock delivered using self-adhesive electrodes in an anteroposterior position; (Step 2) 200 J shock delivered with self-adhesive electrodes in an anterolateral position with manual force applied to the electrodes using standard, disconnected, handheld defibrillation paddles (operator instructed to apply a force equivalent to a ‘push-up’); (Step 3) 360 J shock delivered with self-adhesive electrodes in an anterolateral position with the same prompt as in Step 2; and (Step 4) further shock(s) at the treating physician’s discretion. Anterior electrode placement was prescribed as immediately adjacent to the sternum, below the right clavicle (Figure 1). Posterior electrode placement was prescribed as immediately to the left of the spine, at the level of the heart.

Figure 1.

The Ottawa AF cardioversion protocol. Step 1: 200 J shock delivered using self-adhesive electrodes in an anteroposterior configuration. Step 2: 200 J shock delivered using self-adhesive electrodes in an anterolateral configuration while applying pressure over the electrodes with disconnected standard handheld paddles. Step 3: 360 J shock delivered using the same technique as in Step 2. Step 4: as per the treating physician’s discretion. AF, atrial fibrillation.

Phases I and II

The study was divided into Phases I and II, corresponding to before and after implementing the OAFCP, respectively. Consecutive patients undergoing elective ECV for AF were included in Phase I between October 2012 and May 2015. ECV attempts in Phase I were performed at the discretion of the treating physician. The OAFCP was introduced in July 2015; however, ECVs performed between 1 June 2015 and 31 August 2015 were excluded from data analysis to allow physicians to familiarize themselves with the protocol. A video demonstrating the OAFCP was circulated to clinicians and posters describing its steps were placed in visible areas. In-person training sessions for nursing staff involved in ECVs were also used. The Phase II data collection start date of 1 September 2015 was circulated to all involved clinicians and nurses, after which consecutive patients were analysed. One physician did not agree to follow the protocol prior to its implementation, therefore, his cases were excluded. All elective ECV cases of the remaining 48 cardiologists and cardiac surgeons were examined. Treating physicians completed a case report form for all AF ECV attempts in Phase II to confirm that the patient’s presenting rhythm was AF, that the OAFCP was followed, and to document whether shocks were successful. Institutional administrative records were concurrently referenced to ensure cases were not missed.

All ECVs during Phases I and II were performed using biphasic truncated exponential waveform defibrillators [LIFEPAK 20e (Physio-Control Inc., Redmond, WA, USA) or HeartStart XL (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA, USA)] in the same monitored unit of the hospital (‘day unit’). Propofol has been routinely used at our institute for procedural sedation during elective ECVs for over 10 years. However, data on the doses of sedation used and procedural times were not systematically collected.

Patient characteristics

Detailed clinical variables were collected on all patients in both phases, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), antiarrhythmic medications at the time of ECV, presence of comorbidities (heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack), CHADS2 score, and echocardiographic parameters documented within the preceding 6 months [left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), presence and severity of valvular disease, and left atrial dimensions]. Heart failure was defined as diagnosed by a physician or an LVEF <45% on echocardiogram. Obesity was defined as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Normal LVEF was defined as ≥55% and severe left atrial enlargement as a left atrial volume indexed to body surface area of >48 cm3/m2. Details of each ECV attempt, including individual shock energies and TTI were also collected.

Case and outcome adjudication

Rhythm strips and procedural notes from all ECV attempts in both phases were independently reviewed and adjudicated by a physician not involved in the procedures. ECV attempts without rhythm strips available for review, in patients with initial rhythms other than AF, or in which the OAFCP was not followed (in Phase II) were excluded. The outcome of each shock was classified as a success or failure (see definition below). All pre-discharge 12-lead electrocardiograms were similarly independently reviewed and classified as sinus/atrial-paced rhythm or not sinus rhythm.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was ECV success defined as ≥2 consecutive sinus beats, or captured atrial-paced beats in patients with implanted cardiac devices, after shock delivery. This is consistent with the clinically relevant distinction made in current guidelines between failed ECV and successful ECV with failure to maintain sinus rhythm.5 Secondary outcomes were first shock success, sustained success (defined as sustained sinus or atrial-paced rhythm documented on 12-lead electrocardiogram prior to hospital discharge), and procedural complications (defined as a requirement for temporary pacing or any sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmia).

Statistical analysis

We estimated that sample sizes of 500 and 389 for Phases I and II, respectively, would be required to detect a 50% reduction in ECV failure with 80% power. These estimates were based on a historic success rate of 88% at our centre in a retrospective review of AF ECV attempts between 2009 and 2011 (before Phase I).11

Categorical variables are reported as number (%) and were compared using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation and were compared using t-tests when normally distributed or reported as median (interquartile range) and compared using Mann-Whitney U tests when data were non-normally distributed. The impact of using the OAFCP was estimated by comparing cardioversion success before vs. after its implementation and via simple and multivariable modified Poisson regression with robust error variance to generate relative risk (RR) estimates. Covariate inclusion in multivariable models was guided by clinical judgement and results of exploratory analyses, ensuring adequate numbers of events per variable. Non-normally distributed variables were log-transformed, when required. Effect measure modification was assessed using interaction terms and comparisons of stratified effect measures. Temporal changes in ECV success per 100 consecutive attempts were also evaluated as an interrupted time series with the implementation of the OAFCP introduced as a step function in a segmented autoregressive model. The Durbin–Watson statistic confirmed that correction for autocorrelation was not required. Post hoc sensitivity analyses restricted to the first ECV attempt per patient were undertaken. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) using a two-tailed α level of <0.05 to define statistical significance for the primary outcome and a Bonferroni-corrected α level of <0.017 for secondary outcomes to account for multiple comparisons (=0.05/3). Subgroup and other analyses were considered exploratory and were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Ethics approval and consent

All patients consented to ECV prior to the procedure. Data collection and analysis were approved by the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board as a quality improvement initiative with waiver of consent. The research ethics board required that patients in Phase II be provided with an information sheet describing the OAFCP, details of the planned analysis, and the option to withdraw from the study.

Results

Patient and procedural characteristics

In Phase I, 500 consecutive AF ECV attempts between October 2012 and May 2015 were included, excepting all ECV attempts between 1 May 2013 and 18 August 2013, which had to be excluded because procedural rhythm strips were not available for adjudication. This was due to an operational error that was not immediately recognized (defibrillator internal memory capacity had been reached). In Phase II, 389 consecutive cases between September 2015 and July 2017 were included. An additional 23 ECV attempts were performed in Phase II without following the protocol at the discretion of the treating physician and were excluded from analysis (Supplementary material online, Figure).

Clinical and procedural characteristics of both groups are shown in Tables 1and2, respectively. Patients in Phase II had a higher prevalence of heart failure or reduced LVEF, a higher mean CHADS2 score, and higher rates of amiodarone use, but lower rates of flecainide use and lower TTI.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics before (Phase I) vs. after (Phase II) implementing the Ottawa AF cardioversion protocol

| Characteristics | Phase I (n = 500) | Phase II (n = 389) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and physical dimensions | |||

| Age (years) | 66.1 ± 11.3 | 65.5 ± 11.4 | 0.493 |

| Male sex | 371 (74.2) | 289 (74.3) | 0.975 |

| Height (m) | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.900 |

| Weight (kg) | 94.8 ± 23.9 | 95.6 ± 24.5 | 0.606 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.8 ± 7.0 | 31.1 ± 7.5 | 0.619 |

| Duration of AFa (months) | 24 (7–96) | 25 (6–91) | 0.933 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Obesityb | 233 (46.9) | 192 (50.3) | 0.320 |

| Heart failureb | 93 (18.6) | 116 (29.9) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 199 (39.9) | 178 (46.0) | 0.068 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 71 (14.2) | 66 (17.1) | 0.249 |

| Stroke/transient ischaemic attack | 35 (7.0) | 33 (8.5) | 0.401 |

| CHADS2 score | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 0.002 |

| Antiarrhythmic therapy | 188 (37.6) | 193 (50.1) | <0.001 |

| Amiodarone | 168 (33.6) | 188 (48.8) | <0.001 |

| Flecainide | 10 (2.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0.028 |

| Other | 10 (2.0) | 4 (1.0) | 0.291 |

| Left ventricular ejection fractionc | |||

| Normal (≥55%) | 152 (63.6) | 91 (44.0) | <0.001 |

| Mildly reduced (45–54%) | 34 (14.2) | 40 (19.3) | |

| Moderately reduced (30–44%) | 25 (10.5) | 50 (24.2) | |

| Severely reduced (<30%) | 28 (11.7) | 26 (12.6) | |

| Valvular diseasec | |||

| Mitral stenosis | 0 (0) | 6 (2.9) | 0.008 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 45 (18.8) | 40 (19.4) | 0.875 |

| Aortic stenosis | 5 (2.1) | 12 (5.8) | 0.042 |

| Aortic regurgitation | 10 (4.2) | 13 (6.3) | 0.318 |

| Other | 46 (19.3) | 49 (23.7) | 0.255 |

| Left atrial dimensionsd | |||

| Left atrial diameter (cm) | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 0.259 |

| Left atrial volume (cm3) | 88.7 ± 29.3 | 92.6 ± 29.1 | 0.198 |

| Indexed left atrial volume (cm3/m2) | 43.4 ± 14.7 | 46.9 ± 17.1 | 0.035 |

Data on height or weight were missing in 10 (1.1%); heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and stroke or transient ischaemic attack in 3 (0.3%); antiarrhythmic drug use at time of cardioversion in 4 (0.4%); and transthoracic impedance in 60 (6.6%). Duration of AF could be confidently determined in 375 (42.2%). Echocardiographic measures of left ventricular ejection fraction and valvular disease within the preceding 6 months were available in 446 (50.2%) and of left atrial size in 363 (40.8%). Electrocardiograms performed prior to discharge from hospital were available for review in 880 cases (99.0%).

AF, atrial fibrillation.

n = 152 and 223 in Phases I and II, respectively.

See Methods section for definitions.

n = 239 and 207 in Phases I and II, respectively; valvular disease defined as moderate or severe lesion.

n = 175–180 and 157–184 in Phases I and II, respectively.

Table 2.

Electrical cardioversion details before (Phase I) vs. after (Phase II) implementing the Ottawa AF cardioversion protocol

| Phase I (n = 500) | Phase II (n = 389) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of shocks | |||

| 1 | 399 (79.8) | 344 (88.4) | 0.008 |

| 2 | 70 (14.0) | 30 (7.7) | |

| 3 | 25 (5.0) | 12 (3.1) | |

| 4 | 6 (1.2) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Shock energy (J) | |||

| Initial | 174 ± 39 | 200 ± 0 | <0.001 |

| Maximum | 181 ± 35 | 206 ± 30 | <0.001 |

| Cumulative | 228 ± 121 | 240 ± 133 | 0.155 |

| Transthoracic impedance (Ω) | |||

| First shock | 74 ± 18 | 70 ± 16 | 0.002 |

| Maximum | 74 ± 18 | 71 ± 16 | 0.004 |

Primary outcome

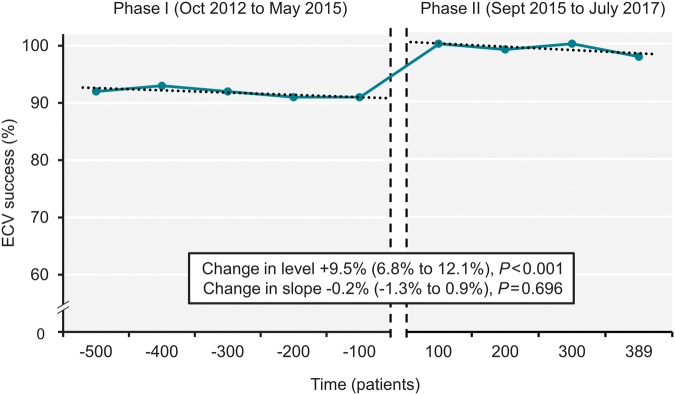

Cardioversion was successful in 459 (91.8%) in Phase I compared with 386 (99.2%) in Phase II (P < 0.001). This corresponds to an absolute increase in ECV success of 7.4% [95% confidence interval (CI) 4.9–10.0%] and a 91% relative reduction in ECV failure with the OAFCP. Interrupted time series analysis confirmed a positive level change in the primary outcome following the implementation of the protocol (Figure 2). Details of the three ECV failures with the OAFCP in Phase II are shown in Supplementary material online, Table S1.

Figure 2.

ECV success for atrial fibrillation over time. Vertical dashed lines denote 3 months during which the Ottawa AF cardioversion protocol was introduced. ECV, electrical cardioversion.

Age <65 years, obesity, and first shock TTI ≥75 Ω were positively associated with ECV failure, whereas sex, heart failure, and amiodarone use were not (Supplementary material online, Table S2). Amiodarone use was nevertheless included in multivariable regression models given its clinical relevance. Implementing the OAFCP was associated with a crude RR of 1.08 (95% CI 1.05–1.11) for ECV success relative to standard technique in Phase I, which was unchanged after adjusting for age, BMI, amiodarone use, and first shock TTI (Table 3). This improvement was consistent in subgroup analyses according to sex, age, obesity, amiodarone use, and first shock TTI (Pinteraction > 0.05 for all) and in sensitivity analyses restricted to the first ECV attempt per patient (n = 742) (Supplementary material online, Tables S3 and S4).

Table 3.

ECV outcomes and estimated impact of implementing the Ottawa AF cardioversion protocol

| Phase I, n (%) | Phase II, n (%) | P-value | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI)a | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECV success | 459/500 (91.8) | 386/389 (99.2) | <0.001 | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | <0.001 |

| First shock success | 396/500 (79.2) | 344/389 (88.4) | <0.001 | 1.12 (1.05–1.18) | 1.09 (1.02–1.15) | 0.008 |

| Sustained successb | 421/497 (84.7) | 351/383 (91.6) | 0.002 | 1.08 (1.03–1.14) | 1.08 (1.02–1.14) | 0.005 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval; ECV, electrical cardioversion; RR, relative risk.

Adjusted for age, body mass index, amiodarone use, and first shock transthoracic impedance.

Based on pre-discharge electrocardiogram review.

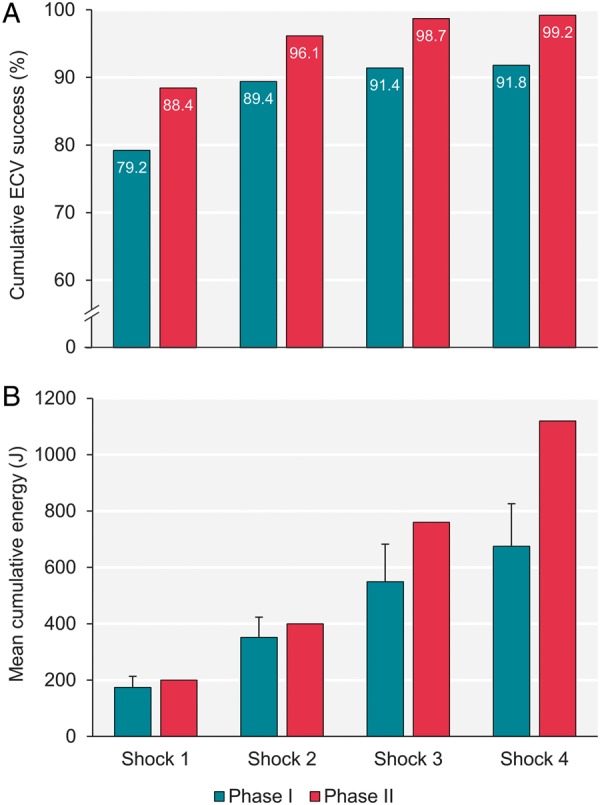

Secondary outcomes

The OAFCP was associated with a 9.2% (95% CI 4.5–14.0%) absolute increase in first shock success (44% relative reduction in first shock failure) and higher cumulative success with all subsequent shocks (Figure 3A). The protocol was also associated with a 6.9% (95% CI 2.7–11.1%) absolute increase in sustained ECV success (45% relative reduction in sustained failure), based on pre-discharge electrocardiogram review. Improvements in first shock and sustained success were similar in crude and adjusted analyses (Table 3). No procedural complications were observed in either study phase. Higher initial and maximum shock energies but fewer shocks were seen with the OAFCP, therefore cumulative shock energies were similar in Phases I and II (Table 2, Figure 3B). These findings were also similar when restricted to the first ECV attempt per patient (Supplementary material online, Tables S3 and S4).

Figure 3.

Cumulative ECV success (A) and energy delivered (B) before (Phase I) and after (Phase II) implementing the Ottawa AF cardioversion protocol, per shock. Error bars depict standard deviation. P-value ≤0.02 for all shock comparisons between Phases I and II. ECV, electrical cardioversion.

Discussion

ECV is the preferred method to restore sinus rhythm in patients with AF in whom a rhythm-control strategy is pursued.2,4 Yet, despite ECV attempts failing in a substantial number of patients, 2,3 limited contemporary data exist to provide procedural guidance. We developed a four-step protocol that can be readily executed with minimal training, implemented it at an institutional level, and evaluated its impact on procedural success at our centre. Our findings suggest that implementing the OAFCP safely reduces ECV failure with a number needed to treat of 14 and that it improves both first shock and sustained success.

Factors influencing electrical cardioversion success

Various modifiable and non-modifiable factors have been associated with ECV failure, most of which relate to two principal determinants of current delivery to the myocardium: the operator-selected shock energy and the resistance to the current reaching the heart (with TTI used as a surrogate measure). Electrode positioning is among the simplest modifiable factors, altering the direction and magnitude of the transcardiac fraction of the current delivered. The anteroposterior approach is recommended in current European and American guidelines.4,5 However, data to support the superiority of this approach are conflicting,6,12 particularly when using modern biphasic defibrillators.9 Likewise, American guidelines support the initial use of higher-energy shocks, but the data invoked for this recommendation are from patients undergoing ECV with outdated monophasic devices.5,8 Applying external force to electrodes has also been suggested as TTI has been inversely associated with ECV success11,13 and can be reduced with this manoeuvre.10,13 It is believed that 8 kg force (approximately 80 N) is optimal based on simulation experiments.10,14 Thus far, however, evidence for the clinical relevance of this manoeuvre has been limited to reports of successful ECV in few patients with AF refractory to initial shocks.15 Therefore, overall, many existing recommendations to improve AF ECV success by targeting reportedly modifiable factors are based on modest quality evidence.

Reported electrical cardioversion practice

Published estimates of ECV success using modern biphasic defibrillators vary considerably but most are limited by small sample sizes. Our pre-intervention ECV success rate of 91.8% was stable over >2.5 years and is comparable to a previous study from our institute11 and to recent estimates from moderately sized studies using contemporary technology. For instance, the Euro Heart Survey on AF reported an ECV success rate of 91% in 424 patients2 and the Biphasic Energy Selection for Transthoracic cardioversion of Atrial Fibrillation (BEST AF) trial reported 89% success in 380 patients.3 The variability in starting shock energy and shock energy escalation observed at our centre prior to implementing the OAFCP is also consistent with reported practices elsewhere. A recent survey of 57 European centres found that nearly two-thirds of hospitals started with a 100 J biphasic shock for AF whereas the remaining third started with 200 J.1 Considerable differences in electrode placement were also reported in this survey with 58.7% of centres using an anterolateral position and the remainder using an anteroposterior approach.1 We and others have previously shown that physicians seldom apply sufficient force even when prompted to do so and even when using handheld paddles.10,16,17 ECV practices at our institute prior to implementing the OAFCP were therefore likely representative of those at most centres.

Protocol development and performance

Previous proposed AF ECV protocols have generally targeted single or few modifiable factors for ECV failure, including electrode placement, shock waveform, starting shock energy, or shock energy escalation, with varying levels of success.6,12 The OAFCP differs from such efforts by simultaneously addressing multiple potentially modifiable factors, including the use of self-adhesive electrodes (to maximize electrode-skin contact while providing continuous cardiac monitoring) and the application of force using handheld paddles (to reduce TTI).10,13,14,18 The first shock of the OAFCP is of high energy and delivered using an anteroposterior electrode configuration. The second shock is similarly of high energy but repositions the posterior electrode to the lateral position to allow practitioners to easily apply force (we previously found that using a ‘push-up’ analogy to guide the amount and direction of force application may be more effective than other prompts10). Biphasic defibrillators with the capacity to deliver 360 J shocks are now available, therefore, a 360 J shock was included in the third step, along with applying force to maximize the likelihood of success. This step was required in only 3.9% of cases and improved ECV success from 96.1% to 98.7%.

The improvement in sustained ECV success observed after the introduction of the OAFCP is likely attributable to greater immediate ECV success with the protocol. No serious acute complications were observed with the OAFCP, which is in keeping with previously reported complication rates, including in the multicentre Finnish CardioVersion (FinCV) study.19 Use of the OAFCP was associated with modestly higher initial and maximum shock energies than with standard ECV technique. However, cumulative energy delivery was similar after protocol implementation and there is little evidence that higher-energy biphasic shocks result in myocardial injury in humans.6

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. The duration of AF and echocardiographic data could only be confirmed in 41–50% of cases therefore, these parameters were not included in multivariable analyses despite being potentially influential.2 However, among cases with these data available, the parameters were either comparable between Phase I and II cohorts or the difference would be expected to have favoured ECV success in the Phase I group. The study also included only elective AF ECV cases therefore our results may not apply to patients with acute onset, severely symptomatic, or hemodynamically significant AF. Women comprised 26% of cases in our study—a population in whom breast tissue is more likely to require modified ECV techniques.20 Although no effect modification by sex was identified, the relatively small number of women studied render effect estimates in this group less precise. Physicians were not blinded to the ECV technique used; however, the primary endpoint was independently reviewed by a physician not involved in the procedure. A randomized controlled study design was not used due to concerns of the potential for contamination between treatment groups given the nature of the intervention and inability to blind physicians. The defibrillators used in the study deliver biphasic truncated exponential waveforms therefore our results may not be generalizable to ECVs with other waveforms. Lastly, for centres that routinely use handheld electrode paddles for ECVs for AF, transitioning to the use of self-adhesive electrodes may be associated with higher costs.

Conclusion

Implementing a simple, non-pharmacologic ECV protocol for patients with AF was associated with a significant reduction in ECV failure without any procedural complications observed. The OAFCP has the potential to safely improve ECV success in patients with AF.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the University of Ottawa Heart Institute Leadership Chair in Electrophysiology, the Tier 1 University of Ottawa Chair in Electrophysiology Research, and the Cardiac Arrhythmia Network of Canada (CANet) as part of the Networks of Centres of Excellence.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Hernandez-Madrid A, Svendsen JH, Lip GY, Van Gelder IC, Dobreanu D, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C. et al. Cardioversion for atrial fibrillation in current European practice: results of the European Heart Rhythm Association survey. Europace 2013;15:915–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pisters R, Nieuwlaat R, Prins MH, Le Heuzey JY, Maggioni AP, Camm AJ. et al. Clinical correlates of immediate success and outcome at 1-year follow-up of real-world cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: the euro heart survey. Europace 2012;14:666–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glover BM, Walsh SJ, McCann CJ, Moore MJ, Manoharan G, Dalzell GW. et al. Biphasic energy selection for transthoracic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. The best AF trial. Heart 2008;94:884–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B. et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Europace 2016;18:1609–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr. et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:e1–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jacobs I, Sunde K, Deakin CD, Hazinski MF, Kerber RE, Koster RW. et al. Part 6: defibrillation: 2010 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation 2010;122(16 Suppl 2):S325–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kirchhof P, Eckardt L, Loh P, Weber K, Fischer RJ, Seidl KH. et al. Anterior-posterior versus anterior-lateral electrode positions for external cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a randomised trial. Lancet 2002;360:1275–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gallagher MM, Guo XH, Poloniecki JD, Guan Yap Y, Ward D, Camm AJ.. Initial energy setting, outcome and efficiency in direct current cardioversion of atrial fibrillation and flutter. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:1498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Walsh SJ, McCarty D, McClelland AJ, Owens CG, Trouton TG, Harbinson MT. et al. Impedance compensated biphasic waveforms for transthoracic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a multi-centre comparison of antero-apical and antero-posterior pad positions. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ramirez FD, Fiset SL, Cleland MJ, Zakutney TJ, Nery PB, Nair GM. et al. Effect of applying force to self-adhesive electrodes on transthoracic impedance: implications for electrical cardioversion. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2016;39:1141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sadek MM, Chaugai V, Cleland MJ, Zakutney TJ, Birnie DH, Ramirez FD.. Association between transthoracic impedance and electrical cardioversion success with biphasic defibrillators: an analysis of 1, 055 shocks for atrial fibrillation and flutter. Clin Cardiol 2018;41:666–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Al-Khatib SM, Allen LaPointe NM, Chatterjee R, Crowley MJ, Dupre ME, Kong DF. et al. Rate- and rhythm-control therapies in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:760–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deakin CD, Sado DM, Petley GW, Clewlow F.. Differential contribution of skin impedance and thoracic volume to transthoracic impedance during external defibrillation. Resuscitation 2004;60:171–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deakin CD, Sado DM, Petley GW, Clewlow F.. Determining the optimal paddle force for external defibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2002;90:812–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cohen TJ, Ibrahim B, Denier D, Haji A, Quan W.. Active compression cardioversion for refractory atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 1997;80:354–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deakin CD, Petley GW, Cardan E, Clewlow F.. Does paddle force applied during defibrillation meet advanced life support guidelines of the European resuscitation council?. Resuscitation 2001;48:301–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sado DM, Deakin CD, Petley GW.. Are European resuscitation council recommendations for paddle force achievable during defibrillation? Resuscitation 2001;51:287–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kirchhof P, Monnig G, Wasmer K, Heinecke A, Breithardt G, Eckardt L. et al. A trial of self-adhesive patch electrodes and hand-held paddle electrodes for external cardioversion of atrial fibrillation (MOBIPAPA). Eur Heart J 2005;26:1292–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gronberg T, Nuotio I, Nikkinen M, Ylitalo A, Vasankari T, Hartikainen JE. et al. Arrhythmic complications after electrical cardioversion of acute atrial fibrillation: the FinCV study. Europace 2013;15:1432–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pagan-Carlo LA, Spencer KT, Robertson CE, Dengler A, Birkett C, Kerber RE.. Transthoracic defibrillation: importance of avoiding electrode placement directly on the female breast. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;27:449–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.