Abstract

Background

Cancer cells possess a common metabolic phenotype, rewiring their metabolic pathways from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis and anabolic circuits, to support the energetic and biosynthetic requirements of continuous proliferation and migration. While, over the past decade, molecular and cellular studies have clearly highlighted the association of oncogenes and tumor suppressors with cancer-associated glycolysis, more recent attention has focused on the role of microRNAs (miRNAs) in mediating this metabolic shift. Accumulating studies have connected aberrant expression of miRNAs with direct and indirect regulation of aerobic glycolysis and associated pathways.

Scope of review

This review discusses the underlying mechanisms of metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells and provides arguments that the earlier paradigm of cancer glycolysis needs to be updated to a broader concept, which involves interconnecting biological pathways that include miRNA-mediated regulation of metabolism. For these reasons and in light of recent knowledge, we illustrate the relationships between metabolic pathways in cancer cells. We further summarize our current understanding of the interplay between miRNAs and these metabolic pathways. This review aims to highlight important metabolism-associated molecular components in the hunt for selective preventive and therapeutic treatments.

Major conclusions

Metabolism in cancer cells is influenced by driver mutations but is also regulated by posttranscriptional gene silencing. Understanding the nuanced regulation of gene expression in these cells and distinguishing rapid cellular responses from chronic adaptive mechanisms provides a basis for rational drug design and novel therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: Metabolism, Warburg effect, microRNA, Aerobic glycolysis, Cancer

Highlights

-

•

Various oncogenes and tumor suppressors are associated with cancer cell metabolism.

-

•

Metabolic reprogramming involves pathways that rely upon microRNA regulation.

-

•

MicroRNAs ensure post-transcriptional buffering of adaptive metabolic responses.

-

•

Dysregulated microRNAs can impact energy flux in cancer cells.

-

•

Cancer metabolism may be disrupted by novel, multi-target, therapeutic interventions.

1. Introduction

In the 1920s, Otto Warburg reported for the first time that while cells under normal conditions utilize glucose to derive 70% of required ATP through mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), cancer cells metabolize glucose by glycolysis even in the presence of adequate oxygen supply [1], [2]. Since then, aerobic glycolysis has been regarded as a hallmark of cancer that provides bioenergetic, biosynthetic and redox balance advantages for cancer cells [3].

Although Warburg's seminal studies resulted in a misinterpretation that irreversible inactivation of mitochondrial respiration is the primary and sole cause of aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells, later it was reported that impaired respiration is inadequate to explain the metabolic shift [4]. The study of cancer cell glycolysis continues to surprise, revealing further associations between a metabolic switch in cancer cells, mutations in mitochondrial metabolic enzymes and altered mitochondrial function [5], [6]. In addition, discoveries that associate oncogene and tumor suppressor gene dysfunction with metabolic reprogramming suggest that both environmental and genetic factors underlie the metabolic heterogeneity of tumors [7], [8]. Moreover, in light of numerous microRNA-related studies, it is now important to consider the roles of these small non-coding RNAs in fine-tuning gene expression at different stages of tumourigenesis. Accumulating evidence supports the involvement of miRNAs in modulating cancer cell metabolism by directly and indirectly regulating genes associated with aerobic glycolysis [9].

microRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs that canonically play a major role in post-transcriptional gene repression. Themselves the products of RNA polymerase II or III dependent transcription, primary (pri)-miRNA transcripts are 5′-7-methylguanosine capped, spliced and 3′-polyadenylated and may give rise to one or more mature miRNAs. Some miRNAs may also derive from processed intronic sequences [10]. In the nucleus, pri-miRNAs are subjected to cleavage by Drosha releasing precursor (pre)-miRNA hairpin structures. Pre-miRNAs are then transported to the cytoplasm where cleavage by Dicer results in a 19–24 nucleotide double-stranded miRNA of which one strand, the mature miRNA, is transferred to the Argonaute (AGO) component of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). AGO acts as a RISC effector protein modulating mRNA stability and translation [11], [12].

This review summarizes recent knowledge of the causes and consequences of the Warburg effect, paying particular attention to the contribution of miRNAs. It also aims to further discuss complex interactions between metabolic pathways and mitochondrial function, as well as oncogenic and tumor suppressor mutations. Finally, in view of recent findings, future approaches that can be exploited for therapeutic benefit are discussed.

2. Metabolic reprogramming

Proliferating cells and, indeed, cancer cells require constant cell division. In order to maintain this, there is an urgent need to provide a consistent energy source, macromolecular biosynthesis, and controlled redox status. Therefore, to optimize proliferation, growth, and survival, cancer cells redirect their metabolic pathways and alter the production and consumption of numerous metabolites [13], [14].

To support cancer cell proliferation, glycolysis provides the precursors for major macromolecules including the carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids needed to produce a new cell. Therefore, aerobic glycolysis imbues cancer cells with ribose, amino acids and fatty acids [15], [16]. The upregulation of glycolysis is mostly due to the increased expression of enzymes and transporters involved in glucose uptake, lactate production, and lactate secretion. These proteins include glucose transporters (GLUT1-4), hexokinase 2 (HK2), glyceraldehyde-3- phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), 6-phosphofructo-1-kinase (PFK1), aldolase (ALDO), triose-phosphate isomerase (TPI), phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1), phosphoglycerate mutase (PGM), enolase 1 (ENO1), pyruvate kinase (PKM2), lactate dehydrogenase (LDHA) and monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs).

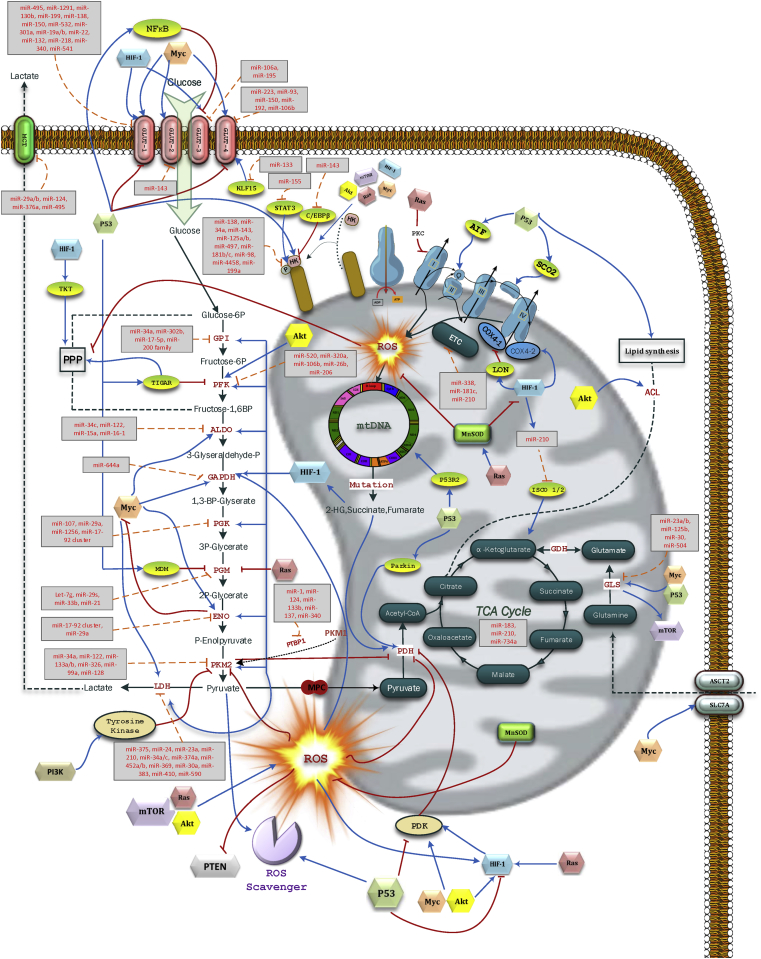

There is substantial evidence regarding the importance of aberrant expression of oncomiRs and tumor suppressor miRNAs targeting key players in aerobic glycolysis to give proliferation, growth, and invasion advantages to cancer cells (Figure 1). Such changes in miRNA activity reflect a mechanism by which cancer cells bypass checkpoints that determine thresholds of biosynthetic enzyme activities.

Figure 1.

miRNAs targeting glycolytic and mitochondrial enzymes.

In addition to miRNAs directly targeting genes involved in cancer cell glycolysis, summarized in Table 1, several indirect mechanisms have been reported for miRNA-mediated regulation of glycolytic genes. Horie et al. [17] showed that forced expression of miR-133 decreases GLUT4 expression by directly targeting Kruppel-like factor 15 (KLF15) in cardiomyocytes. KLF15 is a transcription factor required for GLUT4 transcription. Also, miR-155 was reported to upregulate HK2 through signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) activation, as well as through miR-143 repression by targeting CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ). Moreover, miR-143 was found to target HK2 directly, linking inflammatory miR-155-related signaling with cancer-associated changes in metabolism [18], [19]. PKM is one of the rate limiting enzymes in glycolysis. While PKM1 expression was shown to be active in normal cells, cancer cells switch PKM1 to the tumor-associated PKM2. Also, some miRNAs were reported to regulate polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 (PTB-1), which processes PKM transcripts and is involved in PKM1 to PKM2 conversion in tumor cells. These miRNAs, including miR-1, miR-124, miR-133b, miR-137 and miR-340 were shown to directly inhibit cancer cell proliferation and may also explain the repressed PTB-1 expression associated with tumor progression in vivo [20], [21], [22], [23], [24].

Table 1.

Summary of miRNAs directly targeting glycolytic enzymes and transporters.

| Gene | miRNAs | Diseases | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLUT1 | miR-495, miR-1291, miR-130b, miR-199a, miR-138, miR-150, miR-532, miR-301a, miR-19a/b, miR-22, miR-132, miR-218, miR-340, miR-541 | Renal Cell Carcinoma, Glioma, Breast Cancer, Prostate Cancer, Bladder Cancer, Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Glioblastoma Multiforme | [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33] |

| GLUT2 | miR-143 | – | [34] |

| GLUT3 | miR-195, miR-106a | Bladder Cancer, Glioblastoma | [35], [36] |

| GLUT4 | miR-223, miR-93, miR-150, miR-192, miR-106b | Cardiomyocytes, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, Diabetes Mellitus | [37], [38], [39], [40] |

| HK1 | miR-138 | Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma | [41] |

| HK2 | miR-34a, miR-143, miR-125a/b, miR-497, miR-181b/c, miR-98, miR-4458, miR-199a | Colorectal Cancer, Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Breast Cancer, Lung Cancer, Glioblastoma, Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia, Primary keratinocytes, Osteocarcinoma, Prostate Cancer, Gastric Cancer | [18], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53] |

| GPI | miR-34a, miR-302b, miR-17, miR-200 family | Colorectal Cancer, Primordial Germ Cells, Breast Cancer | [42], [54], [55] |

| PFK | miR-520, miR-320a, miR-106b, miR-26b, miR-206 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Lung Adenocarcinoma, Renal Cell Carcinoma, Osteosarcoma, Breast Cancer | [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61] |

| ALDOA | miR-34c, miR-122, miR-15a, miR-16-1 | Emphysematous Lung, Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Leukemia, Lung Cancer | [62], [63], [64], [65] |

| GAPDH | miR-644a | Prostate Cancer | [66] |

| TPI1 | miR-15a, miR-16-1, miR-107, miR-195 | Leukemia, Renal Cell Carcinoma, Lung Cancer, Bladder Cancer | [63], [65], [67], [68] |

| PGK1 | miR-107, miR-29a, miR-1256, miR-17-92 cluster | Renal Cell Carcinoma, Prostate Cancer, Lung Cancer, Pancreatic Cancer, Squamous Cell Lung Carcinoma | [67], [69], [70], [71] |

| PGM | Let-7g, miR-29a, miR-33b, miR-21 | Primary Human Hepatocytes, Lung Cancer, Renal Cell Carcinoma | [60], [70], [72], [73] |

| ENO1 | miR-17-92 cluster, miR-29a | Lung Cancer | [70], [71] |

| PKM2 | miR-34a, miR-122, miR-133a/b, miR-326, miR-99a, miR-128 | Colorectal Cancer, Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Tongue, Glioblastoma, Type 2 Diabetes, Prostate Cancer | [42], [74], [75], [76], [77] |

| LDHA | miR-375, miR-24, miR-23a, miR-210, miR-30a, miR-34a/c, miR-374a, miR-383, miR-4524a/b, miR-369, miR-410, miR-590 | Maxillary Sinus Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Acute Myocardial Ischemia, Breast Cancer, Colorectal Cancer, Hypoxia-Induced Cardiomyocytes Dysfunction, Ovarian Cancer, Cervical Cancer, Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, Type2 Diabetes | [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88] |

| MCTs | miR-29a/b, miR-124, miR-376a-5p, miR-495 | Pancreatic β Cells, Medulloblastomas, Type2 Diabetes | [89], [90], [91] |

Although several decades have passed since the first report on cancer metabolism, with many studies since, a definitive mechanism underpinning the Warburg metabolic shift has remained obscure. Moreover, how individually disrupted metabolic pathways converge to coordinate a global metabolic shift and facilitate the tumor phenotype remains to be fully elucidated.

3. Inter-connection between aerobic glycolysis and mitochondria

Whilst glycolysis accounts for the generation of almost two thirds of the ATP required for tumor cells, in most cancer cells mitochondria are still functional and generate the remaining energy requirements [92]. Mitochondria also contribute to pivotal roles in controlling anaplerotic and cataplerotic pathways within cancer cells. Indeed, several roles for mitochondria in carcinogenesis, other than ATP production for cellular demands, have been established [93]. As a result, functions including hypoxia resistance, apoptosis escape, reactive oxygen species (ROS) control, and bio-synthetic contributions are attributed to mitochondria. Mutations in mitochondrial TCA cycle genes, encoded by nuclear DNA, were found in various types of cancers. Mutational inactivation of these enzymes contributed to a metabolic shift through direct adaptation to decreased OXPHOS or, alternatively, by epigenetic modification caused by cytosolic and mitochondrial accumulation of oncometabolites such as 2-hydroxyglutarate (2HG) [94], [95], [96], [97], [98].

Studies of miRNA localization from nucleus to mitochondria have led to the discovery of mitochondria-related miRNAs (mitomiRs). A considerable body of literature demonstrated the miRNA contributions to every aspect of mitochondrial metabolism, respiration, and dynamics [99]. Additionally, ROS generated within mitochondria were found to be strictly regulated by several miRNAs (reviewed in [100]). miRNAs that regulate tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle transcripts include miR-183, miR-210 and miR-734a, which target isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH), succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), and malate dehydrogenase (MDH), respectively [101], [102], [103] (Figure 1). Moreover, several electron transport chain components are reportedly regulated by miRNAs. For instance, miR-338 and miR-181c downregulate cytochrome c oxidase complex COX4 and COX1, respectively. Hypoxically regulated miR-210 represses iron-sulfur cluster scaffold (ISCU) and COX10 translation [104], [105], [106]. Glutaminase (GLS) is a rate-limiting enzyme in glutamine metabolism which converts glutamine to glutamate. An increasing number of reports revealed cooperation of c-Myc and p53 with several miRNAs such as miR-23a/b, miR-125b, miR-30 and miR-504 in modulating GLS activity [107]. Based on these reports, it is clear that miRNAs target both nuclear mRNAs and mitochondrial mRNAs. Moreover, the Crabtree effect, originally identified in fermenting yeast, enables some cancer cells to switch between glycolysis and OXPHOS in spite of functional mitochondria and also challenges the “purely glycolytic cancer cell” paradigm. The Crabtree effect is considered to be a short-term and reversible mechanism and an adaptive response of mitochondria to the heterogeneous microenvironment of cancer cells [108]. Hence, there is still a need to fully determine whether changes in mitochondrial functionality, mediated by several miRNAs, contribute to cellular transformation. Otherwise it may be considered a secondary phenomenon, which arises from changes in cell glycolysis and/or other signaling pathways also regulated by miRNAs.

4. Hypoxia and glycolysis

Hypoxia is a common feature in proliferating solid tumors. In normal cells, hypoxia leads to cellular adaptation, or p53-dependent apoptosis and cell death. However, cancer cells acquire mutations in p53 and other genes, along with changes in their metabolic pathways in order to survive and even proliferate under hypoxic stress. A key mediator of responses to hypoxia is hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), a transcription factor that plays a pivotal role in responding to decreased oxygen levels, initiating hypoxia-related processes such as OXPHOS repression and induced glycolysis [109].

Although prolyl-4-hydroxylase (PHD) and factor inhibiting HIF-1 (FIH-1; also known as HIF1AN) dependent regulation of HIF-1 is primarily thought to be the sole mechanism of HIF-1 regulation [110] it is now clear that hypoxia influences miRNA biogenesis and these miRNAs can regulate HIF-1α and HIF-1β expression [111]. HIF-1α is also regulated at the DNA, RNA, protein and DNA binding levels [112]. Translational regulation of HIF-1α could also be a consequence of activating the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway in cancer cells. Many miRNAs, such as miR-99a, were shown to repress HIF-1α expression by targeting mTOR [76]. The abnormal activation of HIF-1 under normoxia could alternatively be a result of changes in cancer-associated genes. Such tumourigenic mutations include loss of function in tumor suppressors such as P53, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) [113], Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) [114], LKB1 [115], promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) [116], and tuberous sclerosis proteins (TSC1/TSC2) [117] along with mutational activation of oncogenes such as Ras [118], V-Src [119], phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) [120], and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her2/Neu) [121]. PKM2 was also reported to enhance HIF-1 transcription, through binding to its promoter, and promote HIF-1 stabilization by inhibiting PHD interactions [122]. Mitochondria also act as both targets and effectors of HIF-1 activation [100]. To adapt to a hypoxic microenvironment and acquire lethal cancer characteristics, HIF-1 activation leads to a range of physiological responses [123]. At the transcriptional level, HIF-1α activates a variety of genes following translocation into the nucleus, dimerization with HIF-1β and binding to hypoxia response elements (HREs) upstream of target genes. Besides HRE-dependent responses, HIF-1α interacts with other signal transduction pathways including Notch [124], Wnt [125] and c-Myc [126].

Activated HIF-1 is directly and indirectly associated with increased expression of virtually all glycolytic transporters and enzymes [123]. Moreover, HIF-1 affects mitochondria through various mechanisms and stimulates glycolysis indirectly by supressing mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, which enables HIF-1 to function as a switch between glycolysis and OXPHOS [127]. HIF-1 represses mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) activity [109], which is a gate-keeping enzyme feeding the TCA cycle by converting pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. HIF-1 suppresses PDH expression by actively upregulating pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK1), a PDH suppressor [128]. By such regulation, pyruvate is converted to lactate, cytosolic NADH is re-oxidized and glycolysis is continued. As a consequence, PDH suppression by activated HIF-1 protects cells from increased ROS generated within mitochondria [129]. In addition, HIF-1 regulates mitochondrial function in response to oxygen by mediating a subunit switch in COX4. HIF-1 induces COX4I2 subunit expression under hypoxic conditions, while the normoxic COX4I1 subunit is downregulated through HIF-1-mediated activation of LON, a mitochondrial protease. This subunit switch optimizes the efficiency of respiration in response to hypoxia by influencing H2O2 levels in an oxygen-dependant manner [127]. Zhao et al. [130] showed that HIF-1α upregulates TKT and TKTL2, two transketolase enzymes of the pentose phosphate pathway, to elevate the ribose production required for nucleic acid anabolic pathways.

Thus far, no mutations within the HIF-1 genes have been associated with its activation or related regulation of glucose metabolism. However, aberrant HIF1 activity has proved to be important in the initiation and maintenance of some tumors [112].

Hypoxia is a significant mediator of miRNA biosynthesis, at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels [131]. A recently identified subset of miRNAs are known as “hypoxia regulated miRNAs” (also termed hypoxiamiRs or HRMs). Hypoxia regulates hypoxiamiRs in either a HIF-1 dependent or independent manner [132]. First reported by Kulshreshtha et al. [111], hypoxia is capable of upregulating miRNA expression (Table 2 and Figure 2). Among these hypoxia-inducible miRNAs, miR-210 and miR-26 were found to have dynamic recruitment of HIF-1 to their promoters. Upon activation, HIF-1α translocates to the nucleus and targets HREs of downstream genes, including miRNA encoding genes. Interestingly, hypoxia is also associated with miRNA downregulation. In that regard, the miR-17–92 cluster was downregulated by hypoxia in p53 wild type cells [133]. Similarly, Lei et al. [134] reported miR-20b upregulation in HIF1-knockdown cells. Other hypoxia-suppressed miRNAs are listed in Table 2. Nevertheless, contrasting reports, with miRNAs such as miR-26 and miR-19, demonstrate that hypoxia-dependent regulation of miRNAs is cell type and microenvironment dependent [111], [135]. Among downregulated hypoxiamiRs, HIF-1 was shown to downregulate miR-17 and miR-199a [136], [137]. HIF-1 also regulates miRNA expression indirectly by mediating the expression of other transcription factors, examples being activation of miR-10b by HIF-1-dependent TWIST1 expression and regulation of miR-20a/b through vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) targeting by HIF-1 [138], [139]. Beside miRNAs directly regulated by hypoxia, it is evident that hypoxia is post-transcriptionally involved in the regulation of hypoxiamiR biogenesis, processing and function in both a HIF-dependent and independent manner. It was shown that hypoxia accelerates Ago2 assembly to RISC and its translocation to stress granules by upregulating Ago2 prolyl-hydroxylation and increasing its endonuclease activity [140]. Moreover, HIF-1 regulates expression of the prolyl 4-hydroxylase, alpha polypeptide I (P4HA1) by regulating miR-124 expression [141]. In fact, stress granule formation increased in a hypoxia-dependent manner. Nonetheless, ADP-ribosylaton of Ago2 in response to oxidative stress is another mechanism that eventually leads to relief of miRNA-mediated repression. Interestingly, it was reported that some miRNA maturation that is not dependent on Dicer activity [142], might be processed by the endonuclease activity of Ago2, the levels of which are induced by hypoxia. Accordingly, Dicer was found to be downregulated by hypoxia, while miR-451 was upregulated [143], [144].

Table 2.

Summary of associations between miRNAs and hypoxia.

| miRNA | Disease/cell line | Regulation of HIF/mechanism | Regulation of miRNA by Hypoxia | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-17-92 cluster | Lung Cancer, Cervical Adenocarcinoma, Inflammation, Colon Cancer, Brest Cancer, Hepatocarcinoma | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α and HIF-2 | Downregulation | [71], [134], [136], [159], [160], [163], [166] |

| miR-15b | Hemophilia, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma | Downregulation/targeting HIF-2 | Downregulation | [166], [167] |

| miR-16 | Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma | NA | Downregulation | [166] |

| miR-19a | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Human Atherosclerotic Lesions | NA | Downregulation/Upregulation | [135], [168] |

| miR-20a/b | Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma, Lung Cancer | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α and HIF-2α | Downregulation | [71], [166] |

| miR-21 | Breast Cancer, Prostate Cancer | Upregulation | Upregulation | [111], [150], [169] |

| miR-22 | Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma, Colorectal Cancer, Heart muscle, Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α | Upregulated/Downregulated | [132], [135], [170], [171] |

| miR-23a/b | Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | NA | Upregulated | [111], [172] |

| miR-24 | Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | NA | Upregulated | [172] |

| miR-26a/b | Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma, Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | NA | Upregulated/Downregulated | [166], [172] |

| miR-27a/b | Heart Muscle, Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | NA | Upregulated | [132], [172] |

| miR-30 b/d/e | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma | NA | Downregulation/Upregulated | [135], [166] |

| miR-29b | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | NA | Downregulated | [135], [172] |

| miR-31 | Colorectal Cancer, Human Corneal Epithelial Keratinocytes, Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Upregulation/targeting FIH1 | Upregulated | [135], [145], [147], [173], [174] |

| miR-33a | Melanoma | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α | NA | [175] |

| miR-93 | Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | NA | Upregulation | [111] |

| miR-99a | Type 2 Diabetes | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α | NA | [76] |

| miR-101 | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | NA | Downregulation | [135] |

| miR-103 | Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | NA | Upregulated | [111] |

| miR-106b | Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | NA | Upregulated | [111] |

| miR-107 | Ischemic Heart Disease, Colorectal Cancer, Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1β | Upregulation | [111], [151], [152] |

| miR-122a | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | NA | Downregulation | [135] |

| miR-125b | Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | NA | Upregulated | [111] |

| miR-128 | Prostate Cancer | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α | NA | [77] |

| miR-135b | Prostate Cancer, Breast Cancer | Upregulation/targeting FIH-1 | NA | [142], [176] |

| miR-138 | Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma, Ovarian Cancer | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α | NA | [177], [178] |

| miR-141 | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | NA | Downregulation | [111] |

| miR-155 | Cervical Adenocarcinoma, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α | Upregulation | [159], [166] |

| miR-181a/b/c | Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma, Heart Muscle | NA | Upregulated/Downregulated | [111], [132], [166] |

| miR-184 | Glioma | Upregulation/targeting FIH-1 | NA | [146] |

| miR-186 | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Gastric Cancer | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α | Downregulation | [135], [179] |

| miR-192 | Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | NA | Upregulated | [111] |

| miR-195 | Hypoxic Chondrocytes, Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α | Upregulation | [111], [180] |

| miR-197 | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | NA | Downregulation | [135] |

| miR-199a/b | Ovarian Cancer, Sickle Cell Disease, Lung Cancer exposed to arsenic, Heart muscle | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α and HIF-2α | Downregulation | [132], [137], [181], [182] |

| miR-204 | Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α | NA | [183] |

| miR-206 | Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α | NA | [149] |

| miR-210 | Cervical Cancer, Head and Neck Paragangliomas, Hypotriploid Human Kidney Cell Line, Ischemia, Breast Cancer, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma, Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Heart Muscle, Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | NA | Upregulation | [111], [132], [135], [154], [166], [184], [185], [186] |

| miR-213 | Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | NA | Upregulation | [111] |

| miR-361 | Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC) | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α | Downregulation | [187] |

| miR-374 | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Breast Cancer | Upregulation/targeting TXNIP | Downregulation | [135], [188] |

| miR-422b | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | NA | Downregulation | [135] |

| miR-424 | Ovarian Cancer, Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Upregulation/targeting CUL2 | Downregulation | [134], [135], [156] |

| miR-429 | Human Endothelial Cells | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α | Upregulation | [165] |

| miR-494 | Lung Cancer | NA | NA | [157] |

| miR-519c | Hepatic Cancer | Downregulation/targeting HIF-1α | NA | [189] |

| miR-565 | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | NA | Downregulation | [135] |

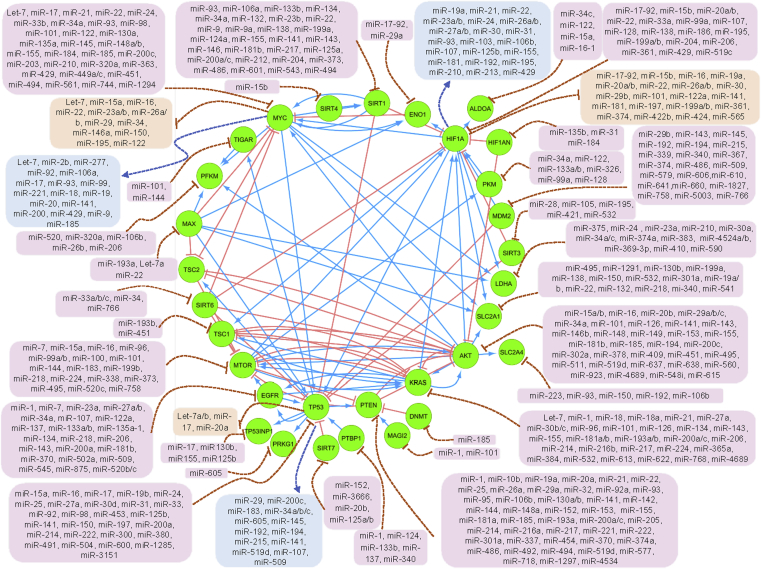

Figure 2.

Interconnections between the drivers and suppressors of glycolysis, and the role of miRNAs in these networks. Protein–protein interactions identified using String V10.0. Solid blue lines indicate protein activation while solid red lines indicate protein inhibition. Dotted blue and red lines represent transcription factor-mediated activation or inhibition of the miRNAs, respectively. miRNAs in pink boxes repress gene expression, while those in orange and blue boxes indicate miRNAs that are inhibited or activated by the transcription factors, respectively. Specific miRNAs present in both the pink boxes and either the orange or blue boxes, may represent feedback loops in particular cellular contexts.

HIF-1α may be directly targeted by miRNAs in various diseases, including cancer (Table 2). Besides direct translational repression, some miRNAs inhibit other factors that modulate HIF-1 expression and stability. As FIH-1 inhibits the transcriptional activation of HIF-1α; miRNAs that suppress FIH-1, such as miR-31, miR-135b, and miR-184, result in HIF-1 activation [142], [145], [146]. FIH-1 was also shown to regulate cell metabolism through reducing glycogen and attenuating AKT signaling [147]. miR-92-1 supresses HIF-1 degradation by targeting pVHL [148]. miR-206 targets the HIF-1/FHL-1 pathway on pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells to promote hypertension [149]. Increased expression of miR-21 was shown to increase HIF-1α and VEGF expression in prostate cancer possibly through a PTEN-dependant pathway [150]. miR-107 downregulates mRNA and protein levels of HIF-1β in endothelial progenitor cells while overexpression of HIF-1β also blocks the effects of miR-107 [151], [152]. miR-185 targets HIF-2a transcripts and, thus, indirectly moderates HIF-1 expression and stability [153].

Feedback loops have been reported in the miRNA regulation of HIF-1. miR-210 forms a positive feedback loop with HIF-1 where hypoxia-induced miR-210 further induces HIF-1α protein stability [154]. Kelly et al. [154] showed that miR-210 targets glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 like (GPD1L), a HIF-1 regulator, and overexpression of miR-210 results in decreased HIF-1 proline hydroxylation and increased accumulation during hypoxia. What's more, HIF-1 directly induces miR-210 expression, which then causes synthesis of cytochrome c oxidase 2/1 (SCO2/1) protein activation and enhanced TCA cycle function [155]. Hypoxia was shown to induce C/EBP levels, which, in turn, increase PU1 activation and binding to the miR-424 promoter to induce its expression. Upregulated miR-424 inhibits cullin 2 (CUL2) and leads to HIF-1 stabilization and nuclear translocation [156]. Overexpression of miR-494 and miR-21 significantly increases Akt phosphorylation and subsequently induces HIF-1 activity [150], [157]. Recent evidence that the activities of non-coding RNAs, including oncogenic miR-21, can be manipulated by small molecules suggests that such processes may be druggable [158].

As a predominant oncomiR, the miR-17–92 cluster has been heavily investigated for its association with hypoxia. Bertozzi et al. [159] showed that miR-17-5p reduced HIF-1α at low camptothecin exposure. miR-17 and miR-20a also target the 3′UTR of HIF-1 and HIF-2 in primary human macrophages [160]. All members of this cluster were shown to directly target HIF-1 in lung cancer [71]. miR-17 and miR-20a were downregulated by HIF-1 through a transcriptional and HIF-1β-independent manner and by downregulating c-Myc expression [136]. miR-20a is a hypoxia-responsive miRNA that targets HIF-1 in breast cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, colorectal cancer, and endometriotic stromal cells [71], [138], [160], [161], [162]. In the paralogous miR-106a∼363 cluster, miR-20b is known to target HIF-1 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and breast cancer cells [163], [164]. Also, chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses revealed that miR-20b prevents HIF-1 binding to the VEGF promoter and, thus, modulates VEGFA expression [163].

Aberrant expression of miRNAs, which can result from hypoxia encountered during tumor progression, may play a critical role in HIF-1 regulation and altered downstream effects (Figure 2). Interestingly, some miRNAs that target HIF-1 were also reported to be modulated by hypoxia in both a HIF-dependent and independent manner. However, some anomalies regarding hypoxiamiRs and miRNAs that regulate HIF-1 still exist. For instance, Bartoszewska et al. [165] showed that HIF-1 is a direct target of miR-429 in HUVEC cells and is induced during hypoxia. However, Sun et al. [157] showed that overexpression of miR-429 increases HIF-1α expression, under both hypoxia and normoxia, and couldn't find a miR-429 target sequence in the 3′UTR of HIF-1α in liver cells. These inconsistencies likely depend on cellular context and experimental conditions. Moreover, as HIF is mainly post-translationally regulated, miRNA activity may be largely redundant in some systems. Table 2 summarizes the associations between hypoxia and miRNAs in different cancers. It has been proposed [92] that the observed Warburg effect is entirely attributable to the in vivo tumor hypoxia and is, in fact, a manifestation of the Pasteur Effect.

5. Metabolic consequences of miRNA associations with driver mutations and transformation

While oncoproteins and tumor suppressor proteins are well-known for their roles in regulating cellular processes such as cell proliferation, they are also capable of affecting cancer cell metabolism. Activation of certain oncogenic signals is important for stimulating glycolysis. Various mutations in different oncogenes and tumor suppressors show that cancer cells alter metabolism to adapt to their microenvironment [190]. These fundamental genes include oncogenes such as KRAS, MYC, AKT, and MTOR, along with their inhibitors (PTEN and TSC1/2) and activator (EGFR). They also include tumor suppressor genes such as TP53, along with its negative regulator murine double mutant 2 (MDM2) and metabolic effector TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator (TIGAR). Sirtuins are further regulatory molecules that can act both as oncogenes and tumor suppressors and will be discussed later. Accumulating evidence highlights the association of miRNAs with oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Some cancer associated genes, such as HIF1, MYC and TP53, regulate both the expression and functions of some miRNAs and are regulated by miRNAs. Table 5 and Figure 2 summarize recent findings on miRNA-mediated regulation of oncogenes and tumor suppressors.

Table 5.

Summary of miRNAs targeting metabolism-related oncogenes and tumor suppressors S indicates references in Supplementary file.

| miRNAs | Gene | Disease | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Let-7 | KRAS, MYC | Breast Cancer, Colorectal Cancer, Lung Cancer, Glioma, Malignant Mesothelioma, Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Gastric Cancer, Prostate Cancer, Burkitt Lymphoma, Malignant Bronchial Epithelial Cell, Pulmonary Hypertension | S [1–8], [199], [205], [224], [234], [236] |

| miR-1 | KRAS, EGFR, PTEN | Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma, Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Cardiovascular Disease | S [9–11], [298] |

| miR-100 | mTOR | Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Bladder Cancer, Endometrioid Endometrial Carcinoma, Breast Cancer | S [12], [325], [326], [327] |

| miR-101 | KRAS, MYC, AKT, mTOR, TIGAR | Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Osteosarcoma, Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma, Prostate Cancer | S [13–15], [331], [332] |

| miR-105 | SIRT3 | Ovarian Cancer | [449] |

| miR-106a/b | SIRT1, PTEN | Pituitary Tumor, Breast Cancer | S [16–18] |

| miR-107 | EGFR | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | S [19] |

| miR-10b | PTEN | Breast Cancer | S [20] |

| miR-122/a | MYC, EGFR | Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Inflammatory Bowel Disease | S [21], [231] |

| miR-124a | SIRT1 | Neuropathic Pain | S [22] |

| miR-125a/b | SIRT1, SIRT7, TP53 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Age-Related Cataract, Multiple Myeloma, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Colorectal Cancer, Neuroblastoma, Cataract | S [23–28], [422] |

| miR-126 | KRAS, AKT | Pancreatic Cancer, Squamous Tongue Cell Carcinoma, Glioma, Colorectal Cancer | S [29,30], [204], [263] |

| miR-1285 | TP53 | Neuroblastoma, Hepatoblastoma | S [31] |

| miR-1294 | MYC | Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma | S [32] |

| miR-1297 | PTEN | Breast Cancer | S [33] |

| miR-130a/b | MYC, PTEN | Osteocarcinoma, Bladder Carcinoma, Non-small Cell Lung Cancer | S [34–36], [223] |

| miR-132 | SIRT1 | Glioma, Type2 Diabetes Mellitus, Gastric Cancer, Colitis | S [37–40] |

| miR-133a/b | EGFR, SIRT1 | Pancreatic Cancer, Ovarian Cancer, Hepatocellular Carcinoma | S [41,42] |

| miR-134 | KRAS, EGFR | Rena Cell Carcinoma, Glioblastoma, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Colorectal Cancer | S [43–45], [207] |

| miR-135a/a-1 | MYC, EGFR | Renal Cell Carcinoma, Prostate Cancer | S [46,47] |

| miR-137 | EGFR | Glioblastoma Multiforme, Thyroid Cancer | S [48,49] |

| miR-138 | SIRT1 | Diabetic Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells, Intervertebral Disc Degeneration, Pancreatic Cancer, Osteocarcinoma | S [50–53] |

| miR-141 | PTEN, AKT, TP53, SIRT1 | Esophageal Cancer, Osteosarcoma, Multiple Myeloma, Pluripotent Stem Cells, Glioma, HB infection | S [25,54–57], [272] |

| miR-142 | PTEN | Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma | S [58] |

| miR-143 | KRAS, EGFR, AKT, MDM2, SIRT1 | Colorectal Cancer, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Bladder Cancer, Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Pancreatic Cancer | S [59–63], [266], [357], [410] |

| miR-144 | PTEN, mTOR, TIGAR | Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor, Preeclampsia, Salivary Adenoid Carcinoma, Renal Cell Carcinoma, Inflammation of Microglia, Lung Cancer | S [64–67], [350] |

| miR-145 | MYC, MDM2, SIRT1 | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Ovarian Cancer, Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas, Glioblastoma, Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Pancreatic Cancer | S [68–70], [266], [357], [410] |

| miR-146b | AKT | Osteosarcoma | [272] |

| miR-148a/b | PTEN, AKT, MYC | Osteosarcoma, Renal Cell Carcinoma, Hepatocellular Carcinoma | S [71,72], [2], [229] |

| miR-149 | AKT | Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Neuroblastoma, Glioblastoma Multiforme | S [73–75] |

| miR-150 | TP53 | Lung Cancer | S [76] |

| miR-152 | PTEN, SIRT7 | Hepatic Insulin Resistance, Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells | S [77,78] |

| miR-153 | PTEN, AKT | Prostate Cancer, Lung Cancer | [275], [276] |

| miR-155 | KRAS, MYC, PTEN, AKT, SIRT5, SIRT1 | Gastric Carcinoma, hepatocellular Carcinoma, Waldenström Macroglobulinemia, Leukemia, Colorectal Cancer, Neuropathic Pain | S [22,79–81], [220], [301], [450] |

| miR-15a/b, miR-16 | TP53, mTOR, AKT, SIRT4 | Multiple Myeloma, Glioma, Ischemia, Dermal Fibroblasts | S [25,82–85] |

| miR-17 | MYC, TP53 | Neuroblastoma, Cervical Cancer | S [86], [361] |

| miR-18/a | KRAS | Human Squamous Carcinoma, Colorectal Cancer, Liver Cancer, Ovarian Cancer | S [87,88] |

| miR-181a/b/d | PTEN, KRAS, EGFR, AKT, SIRT1 | Colorectal Cancer, Osteosarcoma, Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Glioma, Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Glioblastoma Multiforme, Hepatic Stellate Cells, Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases | S [89–97] |

| miR-1827 | MDM2 | Colorectal Cancer | S [98] |

| miR-183 | mTOR | Neuropathic Pain | S [99] |

| miR-184 | MYC | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma | S [100,101] |

| miR-185 | MYC, PTEN, AKT | Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer, Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | S [102–104], [228], [297] |

| miR-192 | MDM2 | Colorectal Cancer, Multiple Myeloma | [358], [376] |

| miR-193a/b | PTEN, KRAS, TSC1/2 | Renal Cell Carcinoma, Colon Cancer, Breast Cancer, Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis | S [105–108], [202], [208] |

| miR-194 | AKT, MDM2 | Gall Bladder Cancer, Multiple Myeloma | S [109], [358], [376] |

| miR-195 | SIRT3 | Myocardium | [446] |

| miR-197 | TP53 | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | S [110] |

| miR-199a/b | SIRT1, mTOR | Pluripotent Stem Cells, Hyperglycemia-Induced Pancreaticβ-Cell Loss, Endometrioid Endometrial Carcinoma | S [111,112], [325] |

| miR-19a/b | PTEN, TP53 | Bladder Cancer, Osteosarcoma, Myeloma, Liver Cancer, Breast Cancer | S [113–116] |

| miR-200a/c | EGFR, TP53, KRAS, PTEN, SIRT1, MYC, AKT | Bladder Cancer, Breast Cancer, Multiple Myeloma, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma, Colorectal Cancer, Hepatic Stellate Cell, Pluripotent Stem Cell, Lung Adenocarcinoma, Renal Cell Carcinoma, Ovarian Cancer, Esophageal Cancers | S [25,117–126], [271], [334] |

| miR-203 | MYC | Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma | S [127] |

| miR-204 | SIRT1 | Osteosarcoma, Spermatogonial Stem Cell, Hepatocellular Carcinoma | S [128,129], [405] |

| miR-205 | PTEN | Ovarian Cancer | S [130] |

| miR-206 | KRAS, EGFR | Gastric Cancer, Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma | S [10,131–133] |

| miR-20a/b | PTEN, AKT, SIRT7 | Coronary Artery Disease, Diabetic Retinopathy, Diabetic Nephropathy | S [134–136] |

| miR-21 | KRAS, MYC, PTEN | Lung Cancer, Breast Cancer, Diabetic Kidney Disease, Colorectal Cancer, Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Leukemia, Vestibular Schwannomas, Glioblastoma, Bladder Cancer, Radio-resistance Lung Cancer | S [5,137–142], [296], [305] |

| miR-210 | MYC | Colorectal Cancer, Glioblastoma, Cervical Cancer, Breast Cancer | S [143] |

| miR-212 | SIRT1 | Prostate Cancer | S [144] |

| miR-214 | KRAS, PTEN, TP53 | Non-small Cell Lung Cancer, Ovarian Cancer, Breast Cancer, Ovarian Cancer Stem Cells | S [145–148], [291] |

| miR-215 | MDM2 | Colorectal Cancer, Multiple Myeloma | [358], [376] |

| miR-216a/b | PTEN, KRAS | Acute Pancreatitis, Kidney Disorders, Ovarian Cancer, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma | S [149–151], [289] |

| miR-217 | KRAS, PTEN, SIRT1 | Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Lung Cancer, Kidney Disorders, Podocyte Injury, Aging | S [152–154], [289], [411] |

| miR-218 | EGFR, mTOR | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Prostate Cancer | S [155,156] |

| miR-22 | MYC, PTEN, SIRT1 | Leukemia, Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma, Glioblastoma, Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury | S [157–161], [225] |

| miR-221 | PTEN | Radiosensitive Cancer Cells, Glioblastoma | S [162], [293] |

| miR-222 | PTEN, TP53 | Radiosensitive Cancer Cells, Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | S [162], [346] |

| miR-224 | KRAS, mTOR | Colorectal Cancer, Gastric Cancer | S [163,164] |

| miR-23a/b | EGFR, SIRT5, SIRT1 | Coronary Artery Disease, Colorectal Cancer, Diabetic Retinopathy | S [165,166], [450] |

| miR-24 | MYC, TP53 | Leukemia, Embryonic Stem Cells, Hepatocellular Carcinoma | S [167,168], [227] |

| miR-25 | PTEN, TP53 | Diabetic Nephropathy, Multiple Myeloma, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Colorectal Cancer | S [25,169,170] |

| miR-26a | PTEN | Glioblastoma | [282] |

| miR-27a/b | KRAS, TP53, EGFR, SIRT5 | Esophageal Squamous Cells Carcinoma, Colorectal Cancer, Renal Cell Carcinoma, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | S [47,171–173], [450] |

| miR-28 | SIRT3 | Primary human tenocytes | [448] |

| miR-29a/b/c | PTEN, AKT, MDM2 | Colorectal Cancer, Gastric Cancer, Prostate Cancer, Breast Cancer, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | S [174–177], [265], [288], [356] |

| miR-300 | TP53 | Lung Cancer, Colorectal Cancer | S [178,179] |

| miR-301a | PTEN | Pancreatic Cancer, Malignant Melanoma | S [180,181] |

| miR-302a | AKT | Prostate Cancer | [264] |

| miR-30b/c/d | KRAS, TP53 | Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Multiple Myeloma, Cardiac Disease | S [170,182–184], [347] |

| miR-31 | TP53 | Breast Cancer | S [185] |

| miR-3151 | TP53 | Malignant Melanoma | S [186] |

| miR-32 | PTEN | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | [287] |

| miR-320a | MYC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | S [187] |

| miR-33 | TP53 | Hematopoietic Stem Cells | S [188] |

| miR-337 | PTEN | Endometrial Carcinoma | S [189] |

| miR-338 | mTOR | Colon Cancer | S [190] |

| miR-339 | MDM2, SIRT2 | Breast Cancer, Neuroblastoma | S [191], [431] |

| miR-33a/b/c | SIRT6, MYC | Liver Cancer, Osteosarcoma | [219], [418] |

| miR-340 | MDM2 | Prostate Cancer | S [192] |

| miR-34a | MYC, EGFR, AKT, SIRT6, SIRT1 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Prostate Cancer, Renal Cell Carcinoma, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Glioma, Colorectal Cancer, Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases, Pancreatic Cancer | S [193–197], [222], [240], [268], [410] |

| miR-363 | MYC | Prostate Cancer, Hepatocellular Carcinoma | S [198], [2] |

| miR-365a | KRAS | Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma | S [106] |

| miR-3666 | SIRT7 | Breast Cancer | S [199] |

| miR-367 | MDM2 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | S [200] |

| miR-370 | EGFR, PTEN | Gastric Cancer, Colorectal Cancer, Gastric Cancer | S [45,201,202] |

| miR-373 | mTOR, SIRT1 | Fibrosarcoma | [333] |

| miR-374/a | MDM2, PTEN | Bladder Cancer, Breast Cancer | S [203,204] |

| miR-377 | SIRT1 | Obesity | S [205] |

| miR-378 | AKT | Breast Cancer | S [206] |

| miR-380 | TP53 | Neuroblastoma | S [207] |

| miR-384 | KRAS | Colorectal Cancer | S [208] |

| miR-409 | AKT | Breast Cancer | S [209] |

| miR-421 | SIRT3 | Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease | S [210] |

| miR-429 | MYC | Gastric Cancer, Breast Cancer | S [119,211] |

| miR-449a/c | MYC | Glioblastoma, Gastric Carcinoma, Osteosarcoma, Prostate Cancer | S [212–214] |

| miR-451 | MYC, AKT | Docetaxel-Resistant Lung Adenocarcinoma, Dilated Cardiomyopathy, Bladder Cancer, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Glioblastoma | S [215–220] |

| miR-451 | TSC1/2 | Multiple Myeloma, Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy | S [221], [335] |

| miR-453 | TP53 | Lung Cancer | S [222] |

| miR-4534 | PTEN | Prostate Cancer | S [223] |

| miR-454 | PTEN | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | S [224] |

| miR-4689 | KRAS, AKT | Colorectal Cancer, | [203] |

| miR-486 | PTEN, MDM2, SIRT1 | Cardiac Myocytes, Lung Cancer, Erythroleukemia | S [225,226], [283] |

| miR-491 | TP53 | Pancreatic Cancer | S [227] |

| miR-492 | PTEN | Hepatic Cancer | S [228] |

| miR-494 | MYC, PTEN, SIRT1 | Epithelial Ovarian Cancer, Cardiac Disease, Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells, Cervical Cancer, Gastric Carcinoma, Pancreatic Cancer | S [229–233], [294], [304] |

| miR-495 | AKT, mTOR | Prostate Cancer | S [234] |

| miR-496 | mTOR | Aging | S [235] |

| miR-5003 | MDM2 | Breast Cancer | S [236] |

| miR-502a | EGFR | Colorectal Cancer | S [237] |

| miR-504 | TP53 | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Colorectal Cancer, Multiple Myeloma, Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm | S [170,238], [360] |

| miR-509 | EGFR, MDM2 | Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Cervical Cancer, Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Prostate Cancer | S [239,240], [355] |

| miR-511 | AKT | Prostate Cancer | S [241] |

| miR-519d | PTENAKT | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | [286] |

| miR-520 b/c/e | EGFR, mTOR, SIRT1 | Gastric Cancer, Fibrosarcoma | S [242], [333] |

| miR-532 | KRAS, SIRT3 | Lung Adenocarcinoma, Ovarian Cancer | S [243], [449] |

| miR-543 | SIRT1 | Hypertension, Gastric Cancer | S [244,245] |

| miR-545 | EGFR | Colorectal Cancer | S [246] |

| miR-548i | AKT | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | S [247] |

| miR-561 | MYC | Gastric Cancer | S [248] |

| miR-577 | PTEN | Glioblastoma | [283] |

| miR-579 | MDM2 | Melanoma | S [249] |

| miR-600 | TP53 | Colorectal Cancer | S [250] |

| miR-601 | SIRT1 | Pancreatic Cancer | S [251] |

| miR-606 | MDM2 | Breast Cancer, Lung Cancer, Colorectal Cancer | [353] |

| miR-610 | MDM2 | Glioma | S [252] |

| miR-613 | KRAS | Ovarian Cancer | S [253] |

| miR-615 | AKT | Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma | S [254] |

| miR-622 | KRAS | Lung Cancer, Colorectal Cancer | S [255,256] |

| miR-637 | AKT | Glioma | [267] |

| miR-638 | AKT | Lung Cancer | S [257] |

| miR-641 | MDM2 | Lung Cancer | S [258] |

| miR-650 | AKT | Rheumatoid Arthritis | S [259] |

| miR-660 | MDM2 | Lung Cancer | [354] |

| miR-7 | EGFR, mTOR | Ovarian Cancer, Glioblastoma, Lung Cancer, Breast Cancer, Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Gastric Cancer | S [260,261], [277], [278], [279], [329], [330] |

| miR-718 | PTEN | Kaposi's Sarcoma, Inflammation | S [262], [292] |

| miR-744 | MYC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | [221] |

| miR-758 | mTOR, MDM2 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | S [263] |

| miR-766 | MDM2, SIRT6 | Breast Cancer, Dermal Fibroblast | S [264], [421] |

| miR-768 | KRAS | Lung Cancer | S [265] |

| miR-875 | EGFR | Prostate Cancer | S [266] |

| miR-9/a | SIRT1PTEN | Hepatic Stellate Cells, Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Colorectal Cancer, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | S [267–272] |

| miR-92 | TP53 | Multiple Myeloma, Pluripotent Stem Cells | S [25,55] |

| miR-923 | AKT | Lung Cancer | S [257] |

| miR-93 | MYC, PTEN, SIRT1 | Colon Cancer, Ovarian Cancer, Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion(I/R) Injury, Breast Cancer, Aging | S [18,273,274], [290], [412] |

| miR-95 | PTEN | Radioresistance Lung Cancer | S [138] |

| miR-96 | KRAS, mTOR | Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Pancreatic Cancer, Colorectal Cancer, Myocardial Hypertrophy | S [184,275–277], [206] |

| miR-98 | MYC, TP53 | Breast Cancer, Lung Cancer | S [5,222] |

| miR-99a/b | mTOR | Breast Cancer, Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Cervical Cancer, Endometrioid Endometrial Carcinoma | [324], [325], [327] |

5.1. KRAS proto-oncogene

The KRAS oncogene features as an early mutation in up to 45% of colorectal tumors, notable because it can drive many hallmarks of cancer [191]. KRAS-mediated transformation is linked with mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction and elevated NADPH oxidase (NOX)-mediated ROS generation [192], [193]. Wang et al. [194] postulated that oncogenic KRAS influences complex I activity in the electron transport chain, most likely by downregulating complex I assembly factor protein (NDUFAF1) and, as a consequence, induces mitochondrial dysfunction. However, additional oncogenic signals and/or loss of tumor suppressors, including dysregulated miRNAs, are required for tumourigenesis.

Unsurprisingly, KRAS is a target of multiple miRNAs, including let-7, miR-96, miR-134 and miR-143 (Summarized in Table 5). These miRNAs affect cancer cell metabolism, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, cell migration and invasion, especially by modulating RAS/MAPK signaling (Figure 2)

KRAS is frequently mutated in human neoplasia including pancreatic, colorectal and lung cancer. The oncogenic KRASG12V variant, which leads to higher KRAS activity, was reported to be the most frequent mutation. However, despite low KRAS mutation frequency in glioblastoma and breast cancer cells, activation of the wild-type KRAS pathway is common in these cancers. Also, sequence variants in the KRAS 3′UTR (rs712) were found in gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, papillary thyroid cancer, breast cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer, which disrupt let-7 binding site and subsequent miRNA-mediated downregulation [195], [196], [197], [198], [199].

The expression of some miRNAs such as let-7, miR-126, miR-200c, miR-193b, and miR-4689 was found to be lower in KRAS mutant cells, as compared to tumors expressing wild-type KRAS [199], [200], [201], [202], [203], confirming the context dependent activity of miRNAs, even in regulating KRAS itself. Kopp et al. [200] reported that in breast cancer cells harboring the KRASG13D mutation, miR-200c targets KRAS transcripts and inhibits proliferation and cell cycle progression, while in KRAS wild type cells miR-200c affects proliferation through other targets. Despite different miR-126 expression levels in KRAS mutant and wild type colon cancer cells, Hara et al. [201] showed that over-expression of miR-126 does not alter KRAS expression and function. In contrast, Jiao et al. [204] showed KRAS regulation by miR-126 in pancreatic cancer. Such variations suggest that the activity of some miRNAs is subjected to changes through both transcriptional and post-transcriptional processes during tumourigenesis. Examples are erythropoietin-producing hepatoma receptor A1 (EphA1) upregulating let-7 in multiple myeloma [205], EVI1 suppressing miR-96 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [206], KLF4 downregulating miR-134 in glioblastoma [207] and MYC associated factor X (MAX) inhibiting miR-193a in breast cancer [208]. Therefore, coordinated suppression of miRNAs, as is found in various cancers, would not only influence oncogenic KRAS activity but may also influence other genes involved in KRAS-related signaling to cooperatively initiate tumourigenesis, including genes in metabolic pathways.

5.2. MYC proto-oncogene

Overexpression of the c-MYC proto-oncoprotein plays pivotal roles in sustaining the transformed phenotype of most cancer cells [209]. The discovery that LDHA is among 20 putative targets of c-MYC provided evidence that c-MYC directly regulates glycolysis. Since then, other glycolytic genes including GLUTs, GAPDH, PGK, HK2, ENO1, PGM, PKM2, and MCTs are also reportedly induced by c-MYC [210].

Along with its role in glycolysis, c-MYC was found to regulate mitochondrial biogenesis, respiration, and function [211]. Upregulation of some nuclear genes that encode proteins for mitochondrial function, mitochondrial DNA replication and transcription of mitochondrial DNA are known to be direct consequences of c-MYC overexpression [212]. c-MYC also contributes to mitochondrial biogenesis and gives rise to the synthesis of acetyl-CoA and fatty acid biosynthesis required for cancer cell proliferation. In parallel, c-MYC upregulates the glutamine catabolism required for biosynthetic processes by inducing GLS and the glutamine transporters, ASCT2 and SLC7A25 [213], [214]. Overall, while c-MYC enhances glycolysis and consequently depletes pyruvate required for mitochondrial OXPHOS, it also confers the ability for cancer cells to utilize non-glucose substrates and maintain mitochondrial respiration to support cancer cell proliferation and progression.

c-MYC cooperates with HIF-1, or acts independently, to regulate glycolysis and OXPHOS [215]. In normal cells, MYC enhances glycolytic flux to OXPHOS. However, in cancer cells, c-MYC cooperates with HIF-1 and PKM2 to upregulate glycolysis and provide adequate metabolic intermediates for biomass synthesis [216]. While upregulation of HIF-1-mediated glycolysis was observed under hypoxic conditions, c-MYC regulates glycolytic genes independently under normal oxygen tension. In addition, while HIF-1 upregulates PDK1 under hypoxia, c-MYC cooperates with HIF-1 to further upregulate PDK1 and, thus, amplifies the hypoxic response. Therefore, under normoxia, c-MYC enhances glycolysis, but it cooperates with HIF-1 to upregulate PDK1 and reduce mitochondrial respiration under hypoxic conditions [217]. Intriguingly, elevated ENO1 was shown to form a negative feedback loop with activated c-MYC. c-MYC-induced ENO1 increases the expression of MBP1, a transcription factor, and suppresses c-MYC expression [218].

c-MYC both regulates miRNA expression and is, in turn, controlled by them (Table 3, Table 5). Several miRNAs have been shown to modulate c-MYC expression by different mechanisms (Figure 2). Let-7a, miR-22, miR-33b, miR-34a, miR-130a, miR-145, and miR-155 were found to suppress c-MYC after binding with canonical target sequences in the c-MYC 3′UTR [219], [220], [221], [222], [223], [224], [225], [226]. miR-24 binds to a seedless, but highly complementary, sequence while miR-18-5p and miR-774 bind to the protein coding region of c-MYC mRNA [221], [227], [228]. Some other miRNAs, such as miR-363-3p act more indirectly. In HCC, miR-363-3p destabilizes c-MYC through targeting USP28, a ubiquitin protease of MYC, and promoting the degradation of pre-existing c-MYC protein [229]. Several reports indicate a coordinated and reciprocal relationship between c-MYC and miRNA expression levels. For instance, Liao et al. [228] showed a negative feedback and auto-regulatory role for c-MYC levels, as monitored by miR-185-3p. They confirmed that miR-185-3p is a genuine transcriptional target of c-MYC but also that miR-185-3p inhibits c-MYC translation by targeting the coding region of c-MYC transcripts.

Table 3.

Summary of miRNAs regulated by the transcription factor MYC.

| miRNA | Regulation | Disease/cells | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-2b | Upregulation | Drosophila S2 Cells | [242] |

| miR-277 | Upregulation | Drosophila S2 Cells | [242] |

| miR-92 | Upregulation | Neuroblastoma, Burkitt Lymphoma | [233], [243] |

| miR-106a | Upregulation | Neuroblastoma, Burkitt Lymphoma | [233], [243] |

| Let-7a/c | Up/Downregulation | Neuroblastoma, Burkitt Lymphoma, Breast Cancer, Prostate cancer | [234], [235], [243], [244] |

| miR-17 | Upregulation | Neuroblastoma, Burkitt Lymphoma | [233], [243] |

| miR-93 | Upregulation | Neuroblastoma | [243] |

| miR-99 | Upregulation | Neuroblastoma | [243] |

| miR-221 | Upregulation | Neuroblastoma | [243] |

| miR-18 | Upregulation | Burkitt Lymphoma | [233] |

| miR-19 | Upregulation | Burkitt Lymphoma | [233] |

| miR-20 | Upregulation | Burkitt Lymphoma | [233] |

| miR-15a | Downregulation | Lymphoma | [245] |

| miR-16 | Downregulation | Lymphoma | [245] |

| miR-22 | Downregulation | Lymphoma | [245] |

| miR-23a/b | Downregulation | Lymphoma, Prostate Cancer | [107] |

| miR-26a/b | Downregulation | Lymphoma, Burkitt Lymphoma, Prostate Cancer | [245], [246], [247] |

| miR-29 | Downregulation | Lymphoma, lung Adenocarcinoma | [245], [248] |

| miR-34 | Downregulation | Lymphoma | [245] |

| miR-146a | Downregulation | Lymphoma | [245] |

| miR-150 | Downregulation | Lymphoma | [245] |

| miR-195 | Downregulation | lymphoma | [245] |

| miR-141 | Upregulation | Embryonic Stem Cells, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma | [249], [250] |

| miR-200 | Upregulation | Embryonic Stem Cells | [249] |

| miR-429 | Upregulation | Embryonic Stem Cells | [249] |

| miR-9 | Upregulation | Breast Cancer | [251], [252] |

| miR-185 | Upregulation | Non-small Cell Lung Cancer | [228] |

| miR-122 | Downregulation | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | [230], [231], [232] |

c-MYC activates or represses a variety of genes, including miRNA genes, mainly through interactions with different complexes and proteins. c-MYC supresses MIR122 gene transcription in liver tumors through association with a conserved promoter region upstream of the MIR122 gene. It also downregulates hepatocyte nuclear factor 3-beta (HNF3β), which normally activates miR-122 and enhances its stability [230], [231].

miR-122 was reported to supress c-MYC expression indirectly by targeting E2F1 and TFDP2 (E2F dimerization partner 2) mRNA [232]. In addition, feedback regulation was reported for miR-17-5p/c-MYC/E2F in some cancers, including breast and prostate [233]. Nadiminty et al. [234] reported a LIN28/let-7/c-MYC loop that plays an important role in some cancers. Relief of c-MYC repression occurs when LIN28, a highly conserved RNA-binding factor, binds let-7 precursors and inhibits miRNA maturation [235]. There is a direct relationship between c-MYC, its dimerization partner, MAX, and the expression of some miRNAs such as let-7a and miR-22 [225], [236]. c-MYC can also transcriptionally activate some miRNAs, including the miR-17-92 cluster, through interaction with MAX protein at the polycistronic promoter region [233], [237]. Ting et al. [225] showed that increased miR-22 limits the amount of MAX protein available for c-MYC binding by directly targeting it and, therefore, affects the expression of downstream targets of the c-MYC/MAX complex. In contrast, interaction of c-MYC with MIZ-1 represses expression of some c-MYC target genes through displacement of p300 co-activator protein [238]. There is also a miRNA/c-MYC negative feedback loop in HCC with miR-148a-5p directly targeting c-MYC and, as previously mentioned, miR-363-3p indirectly destabilizing c-MYC by targeting ubiquitin specific peptidase 28 (USP28) [229]. Other miRNAs that are repressed transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally by c-MYC are summarized in Table 3.

The activation of c-MYC alone is unable to transform cells. Therefore, there is cooperation between oncogenic partners, such as RAS, and inactivation of tumor suppressors such as p53 in c-MYC dependant tumor development [239], [240], [241]. Hence, along with passive adaptation of tumor cells, oncogenic mutations and transcriptional controls, such as the reciprocal association of c-MYC with several miRNAs, enhance the ability of cancer cells to consume non-glucose substrates and fuel mitochondria. This may explain the inefficiency of drugs which only target glycolysis and add another layer of complexity to therapeutic strategies.

5.3. PI3K/AKT pathway

The PI3K intracellular signaling pathway plays a critical role in cell apoptosis, proliferation, and protein synthesis. Its role in regulation of glucose uptake and metabolism is equally definitive. PI3K dysregulation was reported in several human cancers and several drugs targeting this pathway are currently in clinical trials [253]. Activation of PI3K leads to an upregulation of downstream effectors such as AKT and mTOR.

The evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine kinase, AKT, was reported to be one of the most prevalent and constitutively activated onco-proteins in malignant cells [254], [255]. AKT is an important activity-dependent stimulus for cancer cell metabolism, influencing glycolysis by both direct and indirect mechanisms. AKT plays a central role in the regulation of cellular energy metabolism and glucose homeostasis. It stimulates ATP generation by accelerating both glycolytic and oxidative metabolism with a concomitant increase in oxygen consumption to preserve energy. AKT activation results in ROS generation and, therefore, contributes to tumourigenesis by inducing mutations and facilitating tumor-promoting signaling pathways and inducing mutations [256]. Elevated, AKT-mediated, glycolysis plays a major role in proliferation and survival of transformed cells. AKT increases glucose uptake, directly, by increasing the expression and plasma membrane translocation of glucose transporters (GLUT1, GLUT2, and GLUT4) [257]. It also maintains MMP and promotes the association of HK2 with the mitochondrial outer membrane by mediating HK2 phosphorylation and inhibiting glucose-6 phosphate dissociation from the mitochondrial membrane [258]. This may enhance enzymatic efficiency of the kinase, promote metabolic coupling between glycolysis and OXPHOS, increase ATP synthesis through OXPHOS and decrease susceptibility to apoptosis [256]. Indirectly, AKT activates PFK1 phosphorylation and activation by inducing PFK2 and releases forkhead box O1 (FOXO)-mediated repression of glycolysis. AKT also activates mTORC1 indirectly through phosphorylating and, thus, inactivating TSC2, an mTOR inhibitor [259], [260], [261]. The ability of AKT to increase glucose uptake and glycolysis in tumor cells may also require cooperation from other cancer-associated proteins, such as c-MYC and HIF-1. Although AKT-transformed cells show elevated levels of amino acid and lipid transporters that are linked to cell growth, constitutive activation of AKT renders cells dependent on an extracellular glucose supply for survival [256]. Together these findings demonstrate the coordinated regulation of glycolysis and OXPHOS by oncogenic AKT.

AKT, which is described as “Warburg's kinase”, provides selective advantages to tumor cells by increasing both glycolysis and OXPHOS [262]. Several miRNAs were reported to modulate AKT expression directly by targeting AKT mRNA, and protein phosphorylation and/or indirectly regulating its upstream stimuli, such as EGFR and its upstream repressors, such as PTEN (Figure 2).

While some miRNAs, such as miR-637 in glioma, miR-302a and miR-29b in prostate cancer and miR-143 in bladder cancer, directly bind the AKT 3′UTR and inhibit its translation, some other miRNAs, reduce AKT phosphorylation without affecting total AKT levels. For instance, miR-126 reduces AKT phosphorylation by inhibiting by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulatory subunit beta (p85β) [263], [264], [265], [266], [267] (Table 5).

Other proteins and regulatory factors also contribute to regulating AKT activation in different cell types and conditions. For instance, the over-expression of Rictor, a target of miR-34a and mTORC2 component, causes activation of AKT in glioma stem cells [268]. Rictor activation results in mTORC2 activation and consequently, AKT is further activated by mTORC2 mediated phosphorylation [269]. In breast cancer cells miR-205, which is often downregulated in cancer, targets HER3 receptor transcripts and supresses the activation of AKT [270]. Protein phosphatase 2 scaffold subunit Abeta (PPP2R1B) is another intermediate in AKT signal transduction, directly interacting with AKT, and is a target of miR-200c in esophageal cancer cells [271]. Al-Khalaf and Aboussekhra [272] showed that miR-141 and miR-146b-5p target an RNA binding protein, AUF1, which has an important role in PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway regulation. AUF1 binds to and stabilizes PDK1 mRNA and promotes AKT phosphorylation and activation. AUF1 was also reported to negatively regulate PTEN phosphatase and activate PI3K [273], [274]. Additionally, some AKT-targeting miRNAs were shown to regulate drug sensitivity in cancer cells, such as miR-29b and miR-200c that influence chemotherapy responses in prostate and esophageal cancers, respectively [265], [271].

However, the miRNAs that regulate AKT signaling do not act to fully repress AKT and its mediators. Rather, they fine tune expression in a context-specific manner. Therefore, it is likely that AKT is not exclusively regulated by specific miRNAs and further, it is not surprising that some miRNAs, such as miR-153 which targets both PTEN and AKT [275], [276], play complex pleiotropic roles in regulating PI3K/AKT signaling.

Although a number of studies have reported EGFR gene amplification in some cancers, post-transcriptional modulation remains a significant cause of EGFR overexpression in cancer cells (Table 5). For instance, miR-7 was found to regulate expression of multiple effectors of the EGFR signaling pathway, as well as directly targeting EGFR mRNA. Zhou and Hu et al. [277] showed that miR-7 overexpression in epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC) cells results in reduced expression of EGFR without any changes in EGFR phosphorylation. A feedback loop between miR-7 and EGFR was reported [277], [278], as increased EGFR activity results in extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-mediated degradation of YAN, which is a miR-7 repressor. Further, miR-7 binds to the YAN 3′UTR and represses its expression [279].

PTEN has a central role in cell cycle progression. Although mutational loss of PTEN was reported in some cancers, epigenetic factors, including miRNAs, also regulate PTEN expression [280] (Table 5). Due to the unusually long 3′UTR of PTEN, it contains binding sites for many miRNAs, which can reduce its mRNA levels (including miR-32, miR-29, miR-26a/b, miR-217, miR-486, miR-193a, miR-519d) [281], [282], [283], [284], [285], [286], [287], [288], [289] or PTEN translation without affecting its mRNA levels (miR-93, miR-214, miR-221, miR-494, miR-21) [290], [291], [292], [293], [294], [295], [296].

Furthermore, miR-185 in HCC and miR-26a in low-grade glioma alter PTEN promoter methylation and play a subordinate role in PTEN gene regulation by targeting DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) and enhancer of zeste homolog 2 histone methyltransferase (EZH2) [282], [297]. Therefore, along with direct regulation of PTEN by the aforementioned miRNAs, several miRNAs regulate PTEN through indirect mechanisms. Examples include PTEN repression via miR-101 and miR-1 both targeting the PTEN activator, membrane-associated guanylate kinase inverted 2 (MAGI-2); as well as PTEN induction following the miR-185 targeting of PTEN silencer, DNMT1 [297], [298], [299].

High glucose was shown to affect some PTEN targeting miRNAs, such as stimulating miR-21 levels in renal cancer or lowering miR-32 levels in HCC, depending on the physiological status of the cells, which results in AKT activation or suppression, respectively [300], [301].

PTEN dephosphorylates PIP3, generated by PI3K, to inhibit AKT activation. Suppression of PTEN, through miRNA-mediated mechanisms, enhances AKT phosphorylation and signaling and supports cell proliferation and survival [302]. PTEN inhibition also results in cystic vestibular schwannoma development and cancer cell invasion via induced metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) [303]. Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β) mediated AKT activation is another consequence of reduced PTEN activity [289], [304]. Decreased PTEN expression was also shown to impair p53-dependant responses in cancer cells [286]. Moreover, some miRNAs were shown to induce drug- and radio-resistance by inhibiting PTEN. For instance, miR-21 induces daunorubicin resistance in leukemia, miR-214 induces cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells and miR-221 induces TRAIL- and radio-resistance in glioma cells by inhibiting PTEN [288], [293], [305]. Breast cancer metastases in the brain also display increased aggression due to suppression of PTEN by astrocyte exosomal miRNAs [306].

5.4. Mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (mTOR)

Mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), also known as mammalian target of rapamycin, consists of two divergent complexes: complex 1 (mTORC1) and (mTORC2). mTORC1 acts as a metabolic hub, integrating extracellular stimuli with nutrient availability and cellular energy to coordinate responses. mTORC1 is mainly involved in cellular proliferation, translation and metabolic programming while mTORC2 regulates cell survival, cytoskeletal organization, and degradation of newly synthesized polypeptides [307], [308].

mTOR is stimulated by loss of function of some inhibitors including LKB1, PML, PTEN, and TSC1/2 or activation of some oncogenes such as AKT and RAS [115], [116], [262], [309]. Activated mTOR, in turn, dramatically enhances the translational machinery and ribosome biogenesis, increases cell growth in response to mitogens, growth factors and hormones, and upregulates some transcription factors [310]. It also activates several glycolytic enzymes such as GLUT1, LDHA, PKM2, and HK2 [311], [312], [313]. The connection between hypoxia and mTOR is of particular interest. Although it has been shown that mTOR is able to induce HIF-1 translation, mTOR activity is reduced in hypoxia, likely through negative feedback [314], [315]. Hypoxia-mediated inhibition of mTOR could be through activation of tuberous sclerosis protein (TSC1/2) via AMPK, REDD1 or BNIP3 activation [117], [309], [316], [317]. However, there is also evidence that hypoxia-mediated inhibition of mTOR is more prevalent in normal cells compared with cancer cells [318]. Therefore, it may be concluded that mutations in the mTOR signaling pathway account for the reduced hypoxia-mediated mTOR inhibition. It was discovered that mTOR, along with p53, spares the available serine for glutathione synthesis by stimulation of PKM2 protein synthesis, which links glycolysis to anabolic pathways [319]. Moreover, mTOR suppresses autophagy and mitophagy and, therefore, produces ROS. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), an mTOR inhibitor, plays a vital role in metabolic flux and regulates GLUT4 expression, mitochondrial biogenesis and fatty acid oxidation. Complex interaction between mTOR, AKT, and AMPK to regulate GLUT4 translation has also been shown [320]. Activated AKT phosphorylates and inhibits AS160 Rab GTPase activating protein in the cytoplasm leading to increased translocation of the insulin-responsive glucose transporter, GLUT4 to the membrane [321]. Also, ADP and ATP play a critical role in the stability of AKT phosphorylation at residues T308 and S473 and, therefore, act as on/off switches as ATP binds to these phosphorylated sites and protects them against phosphatases. Consequently, AMPK regulates AKT phosphorylation by responding to the equilibrium of the adenylate pool [320], [322]. On the other hand, Kumar et al. [323], reported that FRic−/− murine fat cells, with ablated Rictor, showed impaired insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane and decreased glucose transport.

Given the integral role that mTOR plays in oxygen and nutrient sensing, it is notable that several miRNAs may directly or indirectly influence mTOR activity. Increased expression of MTOR coexists with downregulation of several miRNAs in various types of cancer (Table 5 and Figure 2). Examples include miR-99a/b, miR-100, and miR-199b in cancers, including endometrial cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, and bladder cancer [324], [325], [326], [327]. miR-99 and miR-100 were also reported to be endogenous inhibitors of mTOR protein abundance [328]. miR-7 was found to target MTOR directly and form a negative feedback loop by also directly repressing EGFR and thus results in pleiotropic inhibition of protein translation [329], [330]. Chen et al. and Lin and Shao et al. [331], [332] reported a significant inhibition of mTOR expression, at both RNA and protein levels, by miR-101. Also, miR-373 and miR-520c were reported to reduce MTOR mRNA and protein levels and increase MMP9, which consequently results in the increased migration and invasion capability of cancer cells [333]. A negative regulator of mTOR is TSC1/2 complex. miR-451 was found to target TSC1 and stimulate the stemness phenotype of myeloma cells through activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway [334], [335]. These findings further highlight the role of mTOR, situated at the crossroads of cancer-related signaling pathways. They show the interplay between components of signaling cascades and miRNAs, with practical implications for cancer therapy.

5.5. Tumor protein p53 (TP53)

p53 is a transcription factor and tumor suppressor that plays critical roles in controlling cell cycle progression through DNA damage response and apoptosis, which has been shown to regulate both glycolysis and OXPHOS [190]. In general, p53 inhibits glycolysis transcriptionally by supressing GLUT1, GLUT3, and PGM expression. Therefore, loss of p53 function in many cancers contributes to either glycolysis or the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) [155], [336]. Mutated p53 was shown to reduce oxygen consumption and mitochondrial respiration. First, diminished p53 activity reduces OXPHOS by eliminating its suppression of SCO2, a protein essential for COX assembly and mitochondrial respiration [337]. Moreover, p53 may affect mtDNA by regulating the expression of ribonucleotide reductase subunit p53R2 and, ultimately, regulating mitochondrial oxidative respiration [338]. P53R2 plays important roles in both the biogenesis of mitochondria and mtDNA maintenance [339]. Although p53 induces oxidative stress by its pro-apoptotic function, it can also adversely impact redox maintenance [340]. Anti-oxidant roles of p53 include upregulation of GLS2 and subsequent increase in glutathione as well as enhanced stability of NRF2, an important antioxidant transcription factor, under oxidative stress [341], [342]. Other p53 functions that regulate metabolism include induced PTEN expression, which inhibits the PI3K pathway and glycolysis, cooperation with the OCT1 transcription factor to modulate the balance between glycolysis and OXPHOS and reduced fatty acid oxidation in response to metabolic flux [343], [344], [345].

The identification of several miRNAs that target p53 implies complex regulation and may explain the development of malignancies in cells with wild-type p53, where miRNA-mediated repression of TP53 and its transactivational genes, such as CDKN1A, BBC3, DNM1L, and BAX, is sufficient to cause tumourigenesis [346], [347]. p53 both regulates, and is regulated by, miRNAs. Many of these miRNAs were shown to directly target TP53 in different systems (summarized in Table 5). It is becoming clear that most of these miRNAs represent conservative regulation of p53 activity, targeting multiple components of the p53 pathway. Also, the functional overlap between these miRNAs indicates the potential for cumulative miRNA dysregulation influencing the p53 network during tumourigenesis. p53 suppresses glucose transporters and glycolytic enzymes by enhancing TIGAR [348]. TIGAR is best characterized by its negative regulation of fructose-2, 6-bisphosphatase. Eventually, TIGAR directs glucose to PPP and enhances NADPH production [349]. miR-144 targets TIGAR and modulates autophagy, apoptosis and metastasis in lung cancer cells [350]. In order to survive, cancer cells can also render p53 inactive by point mutation or through degradation induced by the E3 ubiquitin ligase, (MDM2) [351], [352]. Aside from gene mutations, promoter (de)methylation and proteolytic degradation, MDM2 is regulated by miRNAs. miRNAs such as miR-605 and miR-660 directly target MDM and modulate MDM:p53 interaction, aiding rapid stabilization and accumulation of p53. On the other hand, p53 trans-activates the expression of the miR-605 host gene PRKG1 through binding to its promoter region, which results in a positive feedback loop and increased p53 activity [353], [354]. Other miRNAs that suppress MDM2 include miR-509-5p in HCC and cervical cancer, miR-29b in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), miR-143/145 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), miR-192, miR-215, miR-194, and miR-339-5p in renal cell adenocarcinoma, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer [355], [356], [357], [358] (Figure 2).