Abstract

Innate immune factors, such as TRIM5α and cyclophilin A (CypA), act as a major restriction factor of retroviral infection among species. When HIV1 infects human cells, HIV1 capsid binds to human CypA to escape from human TRIM5α restriction. However, in rhesus cells, the mismatch between HIV1 capsid and rhesus CypAis recognized by rhesus TRIM5α to reduce HIV1 infectivity through proteasomal degradation. To circumvent this block, we previously developed a chimeric HIV1 vector(χHIV) that substituted HIV1 capsid with SIV capsid, and it significantly increased transduction efficiency for nonhuman primate cells. In this study, we evaluatedwhether the χHIV vector efficiently transduces human cells, and the transduction efficiency might increase by a CypA inhibitor (cyclosporine) and a proteasome inhibitor (MG132). The χHIV vector could transduce human CD34+ cells, as efficiently as the HIV1 vector, in vitro and in xenograft mice, even in the mismatch between SIV capsid and human CypA. Cyclosporine decreased transduction efficiency with the HIV1 vector, whereas it slightly increased transduction efficiency with the χHIV vector in human CD34+ cells. MG132 increased transduction efficiency with both χHIV and HIV1 vectors in the same manner. However, MG132 was toxic to human CD34+ cells at high concentrations, and both drugs had a small range of effective dosage. These findings demonstrate that both χHIV and HIV1 vectors have similar transduction efficiency for human hematopoietic repopulating cells, suggesting that the χHIV vector escapes from TRIM5α restriction, which is independent of human CypA.

Hematopoietic stem cell (HSC)-targeted gene therapy is potentially curative for hereditary immunodeficiency diseases and hemoglobin disorders [1–7]. However, the transduction efficiency in human HSCs is currently insufficient to drive protein at therapeutic levels for a number of diseases, especially for sickle cell disease. Therefore, improvement of transduction efficiency in human HSCs remains crucial. Because innate immunity plays an important role in the defense against retroviral infection [8–10], an escape from restriction of innate immune factors might be required to achieve the goal for improving transduction efficiency in human HSCs with retrovirus-based vectors.

These factors include the tripartite motif-containing protein 5α (TRIM5α) and cyclophilin A (CypA), which restrict retroviral infections across species [11]. When human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV1) enter human cells in an initial step of viral transduction, HIV1 capsid binds to human CypA to escape from human TRIM5a restriction. On the other hand, when HIV1 enters nonhuman primate cells, the mismatch between HIV1 capsid and simian CypA is recognized by simian TRIM5a of the target cells, which then reduces the infectivity of HIV1 [9,12–15]. The species-specific retroviral restriction of TRIM5α has slowed the development of gene therapy models in nonhuman primates with HIV1-based lentiviral vectors. To overcome this mismatch, we previously developed a chimeric HIV1 vector (χHIV vector), which substituted HIV1 capsid with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) capsid and was able to infect simian cells [16] by escaping from the inhibitory effects of simian TRIM5α. These previous findings were consistent with TRIM5α functions operating in a CypA-dependent pathway.

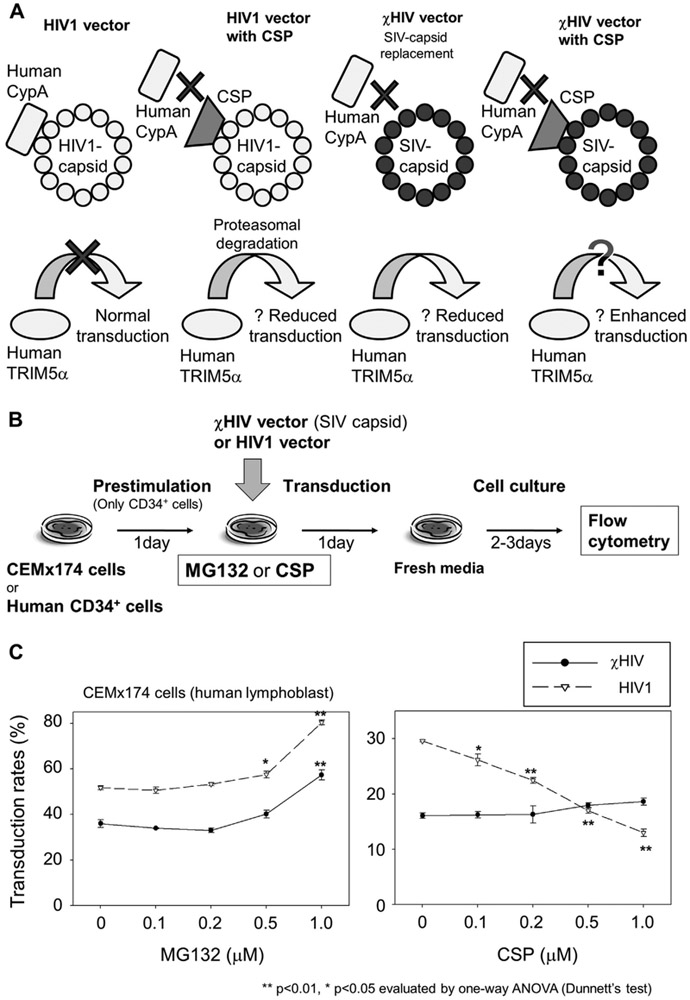

We then investigated whether the χHIV vector would transduce human cells as well as the HIV1 vector, because the mismatch between human CypA and SIV capsid in the χHIV vector should be recognized by human TRIM5α, and transduction efficiency might be theoretically reduced (Fig. 1A). However, competitive inhibitors, such as cyclosporine (CSP), can disrupt this interaction between the χHIV vector and human CypA, and this clinically available drug could potentially improve transduction efficiency with the χHIV vector. In addition, retroviral proteins replicated in infected cells can be degraded by the proteasome pathways in the cytoplasm, and the proteasome degradation is thought to have an important role in TRIM5α restriction [17]. A nonspecific proteasome inhibitor, MG132, might increase transduction efficiency with χHIV and HIV1 vectors because of potentially blocking TRIM5a restriction. In this study, we sought to evaluate whether the χHIV vector can efficiently transduce human cells compared with the HIV1 vector, and whether the χHIV vector transduction can be improved by CSP and MG132 treatment.

Figure 1.

MG132 and CSP effects on transduction in CEMx174 cells. (A) In human cells, HIV1-capsid binds to human CypA to escape from human TRI-M5α restriction, resulting in normal transduction (left side). CSP blocks interaction between CypA and HIV1 capsid, and the HIV1 capsid is recognized by TRIM5a to induce degradation with proteasomes, resulting in reduced transduction (middle left). A cHIV vector with SIV capsid substituted for HIV1 capsid is presumed to function independently of the interaction between CypA and the capsid (right two figures). (B) In media containing MG132 or CSP, we transduced CEMx174 cells (human lymphoblast cell line) at an MOI of 1 and human CD34+ cells at an MOI of 10 with GFP-expressing χHIV vector, including SIV capsid, and HIV1 vector. After an additional 2–3 days culture, transduction efficiency was evaluated by GFP-positive rates (%GFP) in flow cytometry. (C) In CEMx174 cells, the χHIV vector had lower %GFP compared with the HIV1 vector. MG132 showed an increase in %GFP for both vectors at high concentrations. On the other hand, CSP decreased %GFP of the HIV1 vector, but had little effect on %GFP by the χHIV vector.

Methods

Lentiviral vector preparation

The self-inactivating HIVl-based lentiviral vectors were prepared as described previously [16,18,19]. The HIV1 vectors were produced by four plasmid cotransfections of gag-pol plasmid, rev-tat plasmid, vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein envelope plasmid, and enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) expressing HIV1 vector plasmid, which were provided by Dr. Arthur Nienhuis (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, USA) [20,21]. The χHIV vector, which included SIVMAC capsid instead of HIV1 capsid, were prepared using a chimeric gag-pol plasmid in the same manner, as described previously [16,22,23].

‘Lentiviral transduction of a human lymphoblast cell line and CD34+ cells

The CEMx174 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were transduced with both HIV1 and χHIV vectors at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. These vectors were added to 12-well dishes containing 1 × 105 cells/mL of Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 8 μg/mL polybrene, and various concentrations of MG132 and CSP (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After 1 day of exposure, the media were changed to fresh media without vectors, MG132, and CSP. After an additional 2 days of culture, GFP-positive rates (%GFP) were evaluated using flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Human peripheral blood stem cells were mobilized by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and the CD34+ cells were selected by the specific antibody, under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease as described previously [18]. Rhesus CD34+ cells were mobilized by G-CSF and stem cell factor, as described previously [16]. The CD34+ cells were cultured on fibronectin-coated (RetroNectin; Takara, Shiga, Japan) plates using serum free X-VIVO10 medium containing cytokines of stem cell factor, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand, and throm-bopoietin (all 100 ng/mL; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). After 1 day of prestimulation in culture, the media were changed to fresh media containing the same cytokine mixture with lentiviral vectors (MOI = 10) and various concentrations of MG132 and CSP. After 1 day of exposure, the media were changed to fresh media containing the same cytokines (without vectors, MG132, and CSP). An additional 2 days later (Figs. 2, 4, and 5) or 3 days later (Fig. 3), %GFP was evaluated using flow cytometry. The GFP intensity in transduced CD34+ cells at 3 days after medium change was higher than 2 days after medium change, whereas % GFP was similar in both time points (data not shown).

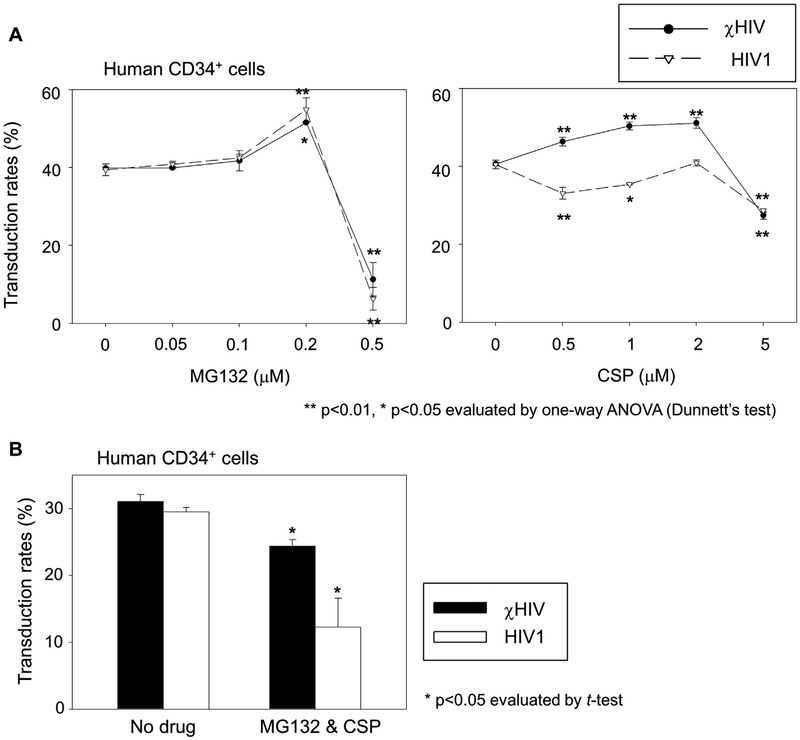

Figure 2.

MG132 and CSP effects on transduction in human CD34+ cells. (A) We transduced human CD34+ cells with escalating doses of MG132 (0.05–0.5 μmol/L) or CSP (0.5–5.0 μmol/L) at an MOI of 10. Both χHIV and HIV1 vectors had similar transduction efficiency (%GFP) for human CD34+ cells with no drug treatment. MG132 increased %GFP with both vectors at 0.2 μmol/L, but decreased %GFP at the highest concentration of MG132 with severe cell toxicity. CSP treatment modestly increased %GFP of the χHIV vector, but decreased %GFP of the HIV1 vector. (B) We then evaluated the combination of MG132 at 0.2 μmol/L and CSP at 1.0 μmol/L for human CD34+ cell transduction. MG132 and CSP decreased %GFP with both χHIV and HIV1 vector transduction.

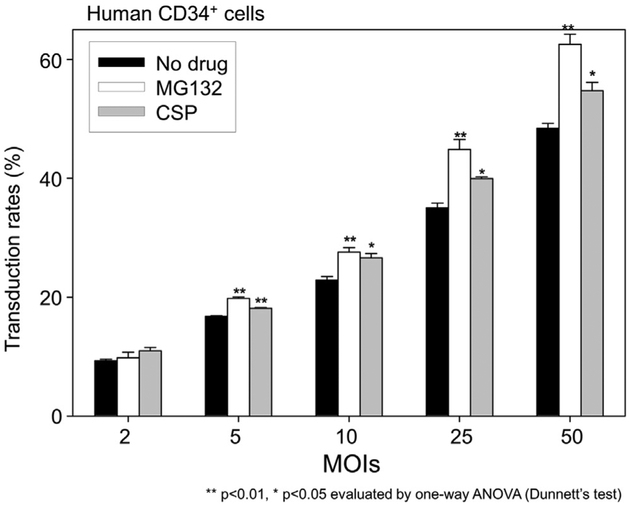

Figure 4.

The equivalent effects of MG132 and CSP in various MOIs. To evaluate whether viral concentration might affect the effects of MG132 and CSP, we transduced human CD34+ cells in MOI escalation of the cHIV vector. A linear increase in transduction efficiency (%GFP) was observed during MOI escalation. Both MG132 and CSP increased %GFP at MOIs 5, 10, 25, and 50; MG132 increased %GFP more than CSP.

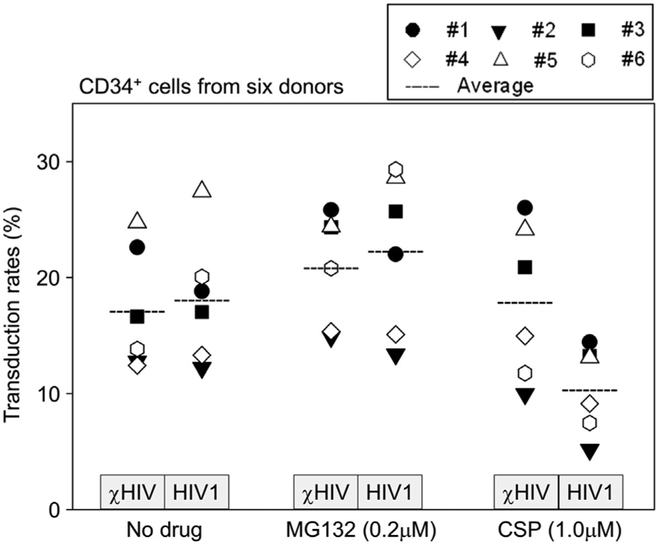

Figure 5.

Individual variations in the enhanced effects of MG132 and CSP. We transduced human CD34+ cells from six healthy donors in the presence of MG132 (0.2 μmol/L) or CSP (1.0 χmol/L). Average data indicated the same trends in which MG132 increased transduction efficiency (%GFP) with both vectors. CSP showed slightly higher %GFP with the χHIV vector and lower %GFP in the HIV1 vector. Large variations of %GFP among individuals were also observed.

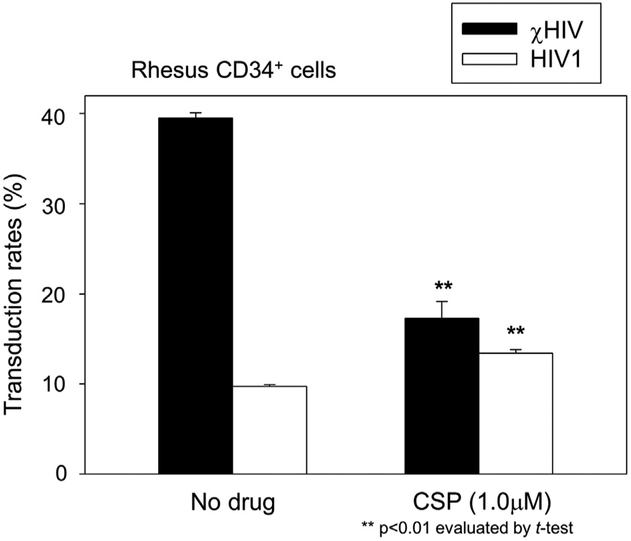

Figure 3.

CSP effects on transduction in rhesus CD34+ cells. We transduced rhesus CD34+ cells after exposure to CSP for 1 day (1.0 μmol/L) with the χHIV or HIV1 vectors at an MOI of 10. The χHIV vector has higher transduction efficiency (%GFP) for rhesus CD34+ cells compared with the HIV1 vector. CSP treatment decreased %GFP of the χHIV vector, whereas it slightly increased %GFP of the HIV1 vector.

Viability of human CD34+ cells

Human CD34+ cells were prestimulated for 1 day in the same cytokine mixture, and the cells were cultured in fresh media containing the same cytokines and various concentrations of MG132 or CSP without the vectors. After 1 day of exposure, the cell viability was evaluated using the annexin V and propidium iodine assay (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA).

Humanized xenograft mouse model

We previously developed a humanized xenograft mouse model with efficient human cell engraftment and transduction using GFP-expressing HIV1 vectors, which allowed evaluation of % GFP in peripheral blood cells in several time points after trans-plantation [17]. We also demonstrated similar %GFP between peripheral blood cells and bone marrow cells 3 months after transplantation [24]. We used male NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull mice (NOD.Cg-Prkdscid Il2rgtmlWjl/SzJ; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA), following the guidelines of the Public Health Services Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under a protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, as described previously [18]. Busulfan (35 mg/kg; Busulfex; PDL BioPharma, Redwood City, CA, USA) was administered to the mice 2 days before transplantation. Human CD34+ cells (2 × 106 cells per mouse) were prestimulated for 1 day, and the cells were transduced with the GFP-expressing χHIV vector (or HIV1 vector) at an MOI of 50 in the media containing MG132 (0.2 μmol/L) or CSP (1.0 μmol/L). After 1 day of exposure, the cells were injected into the tail vein. Following transplantation, human CD45 expression (human CD45-phycoerythrin antibody, clone HI30; BD Biosciences) and % GFP in peripheral blood cells were evaluated by flow cytometry over 6 months after transplantation (N = 3–5).

Colony-forming unit assay

Human CD34+ cells were prestimulated for 1 day, and the cells were transduced with the GFP-expressing χHIV vector at an MOI of 10 in the X-VIVO10 media containing the same cytokine mixture with MG132 (0.2 μmol/L) or CSP (1.0 μmol/L). After 1 day of exposure, the cells were split into methylcellulose media (1000 cells per dish for no drug control and CSP, and 5000 cells per a dish for MG132) and cultured for 1 week [16,25]. GFP-positivity in myeloid colonies was evaluated by ultraviolet microscopy, whereas vector signals in myeloid colonies (24 colonies for each group) were evaluated using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The vector-specific sequences were amplified using LV2 probe and primers and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) probe and primers for 50 cycles [23]. PCR-positive was defined by both positive LV2 signals and positive rRNA signals, whereas PCR-negative was defined by both negative LV2 signals and positive rRNA signals.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the JMP 9 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The averages in various conditions were evaluated using the Dunnett test (one-way analysis of variance for one control value). Two averages were evaluated using the Student t test; p < 0.01 or 0.05 was deemed significant. Standard errors of the mean are shown as error bars in all figures. All in vitro experiments (except for colony-forming unit [CFU] assay) were performed in triplicate (N = 3).

Results

MG132 and CSP increased χHIV vector transduction in human CD34+ cells

To evaluate the effects of MG132 and CSP on lentiviral transduction, we first performed a 1-day transduction of a human lymphoblast cell line (CEMx174) with GFP-expressing χHIV or HIV1 vectors in media containing various concentrations (0.1–1.0 μmol/L) of MG132 or CSP at MOI of 1 (Fig. 1B). The transduction efficiency was evaluated by %GFP in flow cytometry. Two days after transduction, MG132 increased %GFP of both χHIV and HIV1 vectors at higher concentrations (1.0 μmol/L; p < 0.01; Fig. 1C). On the other hand, CSP had little effect on %GFP in χHIV vector (0.1–1.0 μmol/L, not significant), but decreased %GFP of the HIV1 vector (0.1–1.0 μmol/L; p < 0.05, Fig. 1C). In addition, when there was no drug treatment, the χHIV vector showed lower %GFP in the human lymphoblast cell line compared with the HIV1 vector (p < 0.01). These data suggest that both χHIV and HIV1 vectors were restricted by proteasomes, and this restriction could be blocked by MG132. In the human lymphoblast cells, the mismatch between human CypA and SIV capsid in the χHIV vector might be detected by human innate immune factors including TRIM5α, and this restriction was not efficiently blocked by CSP. That the HIV1 capsid in the HIV1 vector could escape from this restriction may be due to interaction between HIV1 capsid and human CypA, and it was blocked by CSP.

Next, we transduced human CD34+ cells with χHIV or HIV1 vectors in media containing either MG132 or CSP at an MOI of 10 (Fig. 2A). The different concentration ranges were used as dose escalation of MG132 or CSP for human CD34+ cells. Interestingly, both cHIV and HIV1 vectors had similar %GFP in human CD34+ cells with no drug treatment (not significant). In dose-escalation studies of MG132 (0.05–0.5 μmol/L) and CSP (0.5–5.0 μmol/L), MG132 increased %GFP detected in both vectors (0.2 μmol/L; p < 0.01; Fig. 2A). However, much lower %GFP was observed at the highest concentration of MG132 (0.5 μmol/L; p < 0.01) with severe cell toxicity. CSP treatment increased %GFP in the χHIV vector (0.5–2.0 μmol/L; p < 0.01) but decreased %GFP in the HIV1 vector (except at 2.0 μmol/L; p < 0.05; Fig. 2A). These data suggest that both MG132 and CSP could increase transduction efficiency for human CD34+ cells with the χHIV vector that includes SIV capsid, but both drugs had a small range of effective dose. In human CD34+ cells, the mismatch between human CypA and SIV capsid in the χHIV vector was not significantly recognized by human innate immune factors including TRIM5α, and CSP might block this weak restriction to increase transduction efficiency slightly with the χHIV vector.

MG132 is toxic to human CD34+ cells at high concentrations

To investigate the toxicity of MG132 and CSP on human CD34+ cells, we evaluated the viability of human CD34+ cells in increasing concentrations of MG132 and CSP using annexin V (apoptosis) and propidium iodide (cell death) assays. The lentiviral vectors were not added in the toxicity evaluation for MG132 and CSP, because vector transduction itself might introduce additive or confounding toxicities. One day after drug exposure, MG132 decreased cell viability at increasing concentrations, whereas CSP did not affect cell viability (Supplementary Figure E1, online only, available at www.exphem.org). These data suggest that MG132 alone could be toxic to human CD34+ cells, especially at high concentrations, and this drug toxicity might sufficiently explain the lower transduction rates at high concentration.

We then evaluated human CD34+ cell transduction with χHIV and HIV1 vectors in the media containing both MG132 (0.2 μmol/L, optimal dose) and CSP (1.0 μmol/L; Fig. 2B). This combination decreased transduction rates in both vectors (p < 0.05). These data further support that toxicity to human CD34+ cells might be enhanced by the two-drug combination.

Next, to contrast the human CD34+ cell transduction, we transduced rhesus CD34+ cells in the presence of CSP (1.0 μmol/L) with the χHIV and HIV1 vectors (Fig. 3). The χHIV vector (no drug treatment) demonstrated higher % GFP in rhesus CD34+ cells compared with the HIV1 vector (p < 0.01), whereas both vectors had similar %GFP in human CD34+ cells (Fig. 2A and B). CSP decreased % GFP in the χHIV vector (p < 0.01, compared with no drug treatment), but modestly increased %GFP in the HIV1 vector (p < 0.01, compared with no drug treatment). These data suggest that the mismatch between rhesus CypA and HIV1 capsid could be recognized by rhesus TRIM5α, and it was slightly blocked by CSP. The cHIV vector could escape from this restriction because of an interaction between SIV capsid and rhesus CypA, and it was blocked by CSP. In addition, these data indicate that when there was no mismatch between the viral capsid and CypA (HIV 1 vector in human CD34+ cells [Fig. 2A, CSP panel] and cHIV vector in rhesus CD34+ cells [Fig. 3]), CSP actually decreased transduction efficiency. On the other hand, CSP modestly increased transduction efficiency when the mismatch was present.

Higher MOIs increases transduction more than MG132 or CSP

We next investigated whether MG132 or CSP might improve transduction efficiency at a wide range of vector concentrations, because we hypothesized that innate immune factors might be saturated by a high MOI. We transduced human CD34+ cells in MOI escalation with the χHIV vector in the media containing MG132 (0.2 μmol/L) or CSP (1.0 μmol/L; Fig. 4). Both MG132 and CSP increased %GFP at MOIs of 5, 10, 25, and 50 (p < 0.05, compared with no drug treatment); MG132 increased %GFP more than CSP. These results suggest that TRIM5α and CypA were not saturated at MOI of 50, and the linear increases in transduction efficiency were more affected by MOI escalation.

There are individual variations in human CD34+4 cell transduction modified by MG132 and CSP

To evaluate whether individual variations can affect transduction efficiency for human CD34+ cells, we transduced CD34+ cells from six healthy donors in the presence of MG132 (0.2 μmol/L) or CSP (1.0 μmol/L; Fig. 5). Large variations of %GFP were observed among individuals. Overall, the average %GFP showed the same trends: higher %GFP with exposure to MG132 (not significant). CSP treatment appeared to lower %GFP with the HIV1 vector in most of the individuals. When we compared the average data between χHIV and HIV1 vectors, the χHIV vector had higher %GFP with CSP treatment compared with the HIV1 vector (p < 0.05), and both vectors showed similar %GFP with no drug treatment and MG132 treatment (not significant). These data suggest that MG132 might enhance transduction efficiency of human CD34+ cells with both χHIV and HIV1 vectors. The addition of CSP again negatively affected only HIV1 vector transduction among human CD34+ cells.

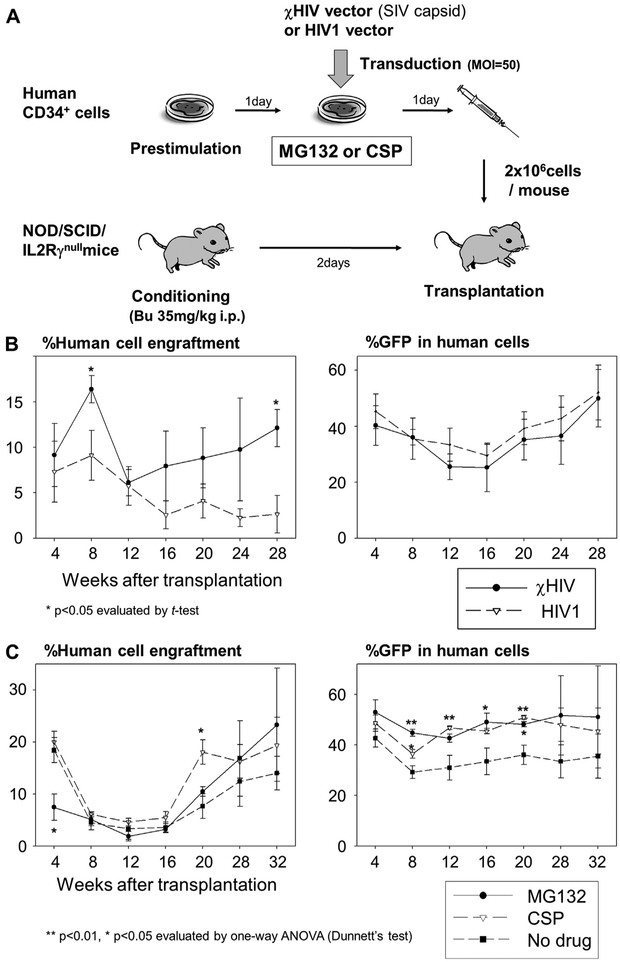

MG132 and CSP increased transgene expression rates of the χHIV vector in human hematopoietic repopulating cells

To evaluate whether the χHIV vector (containing SIV capsid) can efficiently transduce human hematopoietic repopulating cells compared to the HIV1 vector, we transduced human CD34+ cells with the χHIV and HIV1 vectors and injected the transduced cells into sublethally conditioned immunodeficient mice (Fig. 6A). We evaluated human cell engraftment and %GFP in peripheral blood cells over 6 months. Both vectors showed similar %GFP in human cells and similar human cell engraftment over 6 months (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that the χHIV vector could efficiently transduce human hematopoietic repopulating cells as well as the HIV1 vector.

Figure 6.

The enhanced effects of MG132 and CSP on transduction efficiency in hematopoietic repopulating cells. (A) To assess transduction efficiency in hematopoietic repopulating cells in vivo, we transduced human CD34+ cells (B) with the GFP-expressing χHIV vector (containing SIV capsid) and HIV1 vector and (C) with the χHIV vector alone in media containing MG132 (0.2 μmol/L) or CSP (1.0 μmol/L). The transduced cells were transplanted into sublethally conditioned NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull mice. Human cell engraftment and GFP-positive rates (%GFP) in the peripheral blood cells were evaluated using flow cytometry. (B) To evaluate whether the χHIV vector can efficiently transduce human hematopoietic repopulating cells as well as the HIV1 vector, we compared the two vectors in the humanized mouse model. Both vectors showed similar human cell engraftment and %GFP in human cells over 6 months. (C) To evaluate the enhanced effects on transduction efficiency in human repopulating cells, we transduced human CD34+ cells with MG132 or CSP treatment, and the cells were transplanted into immunodeficient mice. MG132 and CSP increased %GFP expressed in the human cells, whereas there was no difference in human cell engraftment among MG132, CSP, and control groups (no drug treatment). Bu = busulfan.

To evaluate the enhanced effects on transduction efficiency in long-term hematopoietic repopulating cells in vivo, we transduced human CD34+ cells with the χHIV vector in media containing MG132 (0.2 μmol/L) or CSP (1.0 μmol/L), and the transduced cells were transplanted into immunodeficient mice. Although there was no difference in human cell engraftment (Fig. 6C), MG132 and CSP increased %GFP expressed within the human cells by approximately 20% (Fig. 6C; MG132 at 8, 16, and 20 weeks and CSP at 8, 12, and 20 weeks; p < 0.05). These data suggest that both MG132 and CSP could increase transduction efficiency with the χHIV vector in long-term hematopoietic repopulating cells, but could not change engraftment ability of long-term repopulating cells.

Discussion

In this study, our χHIV vector (containing SIV capsid) demonstrated similar transduction efficiency (evaluated by %GFP) in human CD34+ cells in vitro (Figs. 2A and5) and in humanized xenograft mouse transplantation (Fig. 6B) as compared with the HIV1 vector overall, whereas the χHIV vector produced lower transduction efficiency in the human lymphoblast cell line. Interestingly, MG132 increased transduction efficiency similarly with both vectors, but CSP decreased transduction efficiency with only the HIV1 vector. TRIM5α is an important factor for species-specific retroviral defense, and it targets viral capsid through CypA and restricts HIV1 infectivity [9,10]; therefore, we then investigated the interaction between viral capsid and CypA in the matched and mismatched species settings to understand the effects of CSP in χHIV and HIV1 vector transduction.

We originally thought that CSP might pharmacologically inhibit the viral capsid-CypA interaction, which might allow viral vectors to escape from TRIM5α restriction and improve transduction efficiency. To our surprise, we found that when there was species agreement between capsid and CypA (HIV1 vector in human cells or χHIV vector in rhesus cells), CSP actually decreased transduction efficiency without causing cell toxicity. These results indicate that the viral particles, when displaced from the protective effect of CypA by CSP, can then be targeted by host innate immune factors including TRIM5α. Furthermore, this inhibitory effect is not complete because transduction still occurs at high concentrations of CSP. On the other hand, when there was the mismatch between viral capsid and CypA, CSP had small, enhanced effects on transduction efficiency (χHIV vector in human cells or HIV1 vector in rhesus cells), suggesting that transduction likely occurs in a CypA-independent manner. This interpretation is supported by previous reports that HIV1 infection can occur normally in CypA-deficient experiments [10,25]. In addition, the inhibitory effect of TRIM5α and CypA is likely more complex than our original understanding, because vector transduction also occurred in the mismatched setting.

To evaluate individual variations in human CD34+ cells, we investigated how CSP would affect the transduction of both χHIV and HIV1 vectors in six individuals. We observed large individual variations without drug treatment. With CSP treatment (1.0 μmol/L), three donors had increased transduction efficiency with the χHIV vector (nos. 1, 3, and 4; Fig. 5) but not in the other three donors (nos. 2, 5, and 6). These data demonstrated that individual variations of transduction efficiency for human CD34+ cells exist, and the broader applicability of CSP in the transduction of CD34+ cells and future clinical gene therapy trials could be limited because of the possible need to optimize CSP dosages for each patient.

The proteasome degradation system is also essential for retroviral defense because viral proteins, made during replication, can be degraded. Specifically in antiviral mechanism of TRIM5α, the proteasome is thought to be important for degradation of TRIM5α-retrovirus complex [17]. This pathway can be inhibited by MG132 or other drugs [26,27]. We demonstrated that the MG132 increased lentiviral transduction efficiency in human CD34+ cells in vitro and in xenograft mice (Figs. 2A and6), which corroborates with the in vitro data reported by another group [28]. Unfortunately, MG132 has a narrow effective dose (Fig. 2) and had little benefit in four of the six donors (Fig. 5). Moreover, MG132 activated program cell death [29] to cause severe toxicity for human CD34+ cells; even in the effective dose of 0.2 μmol/L, there was approximately 30% cell death (Supplementary Figure E1, online only, available at www.exphem.org). These results are consistent with previous reports showing inhibitory effects in thymocytes, leukemic cells, natural killer cells, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells [26,27,30–32]. Collectively, MG132 has a high toxicity-to-benefit ratio, and the use of other proteasome inhibitors with lower toxicity may be required in clinical gene therapy studies.

In addition, we evaluated transduction efficiency for hematopoietic progenitor cells using CFU assay, in which human CD34+ cells were transduced with the GFP-expressing χHIV vector in the media containing MG132 (0.2 μmol/L) or CSP (1.0 μmol/L), and we evaluated GFP-positivity by ultraviolet microscopy and vector signals by PCR [25,33].MG132decreasedCFUs in both erythroid colonies (E; 0.8 per 1000 cells) and myeloid colonies (M; 7.5 per 1000 cells), compared with CSP (E: 13.3 per 1000 cells; M: 18.3 per 1000 cells) and no drug treatment (E: 24.7 per 1000 cells; M: 41.0 per 1000 cells). Expectedly, PCR-positive colonies were detected more frequently than GFP-positive colonies in all groups (Supplementary Figure E2, online only, available at www.exphem.org), because PCR detection is more sensitive with potential overestimation. MG132 and CSP slightly increased GFP-positivity in myeloid colonies, compared with no drug treatment group. Twofold more PCR-positive colonies were detected in the MG132 group, compared with CSP and no drug treatment groups. These data suggest that MG132 might increase stability of lentiviral vectors in transduced cells by inhibiting proteasomal degradation. It revealed again that MG132 is toxic for hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Our χHIV vector showed similar transduction efficiency, compared with the HIV1 vector, for human CD34+ cells in vitro (Figs. 2A and5) and human hematopoietic repopulating cells evaluated by humanized xenograft mice (Fig. 6B). On the other hand, the χHIV vector had comparatively high transduction efficiency, as opposed to the HIV1 vector, for rhesus CD34+ cells in vitro (Fig. 3) and rhesus hematopoietic repopulating cells in rhesus hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [16,33]. These data demonstrated that the χHIV vector system can efficiently transduce both human and rhesus hematopoietic repopulating cells, which allows us to evaluate efficacy and safety of HIV1-based therapeutic vectors using both human and rhesus hematopoietic cells in animal models toward successful clinical gene therapy trials.

In summary, χHIV and HIV1 vectors performed similarly in human CD34+ cells. Both MG132 and CSP increase transduction efficiency of the χHIV vector in human CD34+ cells in vitro and in vivo without compro-mising the long-term engraftment in humanized mice. These benefits should be weighed carefully against the small range of effective dosage and the toxicity of MG132.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hayato Unno for help with this study. This work was supported by the intramural research program of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases at the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.exphem.2013.04.014.

Conflict of interest disclosure

No financial interest/relationships with financial interest relating to the topic of this article have been declared.

References

- 1.Aiuti A, Cattaneo F, Galimberti S, et al. Gene therapy for immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:447–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiuti A, Slavin S, Aker M, et al. Correction of ADA-SCID by stem cell gene therapy combined with nonmyeloablative conditioning. Science. 2002;296:2410–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Garrigue A, Wang GP, et al. Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3132–3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, von Kalle C, Schmidt M, et al. A serious adverse event after successful gene therapy for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:255–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarzwaelder K, Howe SJ, Schmidt M, et al. Gammaretrovirus-mediated correction of SCID-X1 is associated with skewed vector integration site distribution in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2241–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ott MG, Schmidt M, Schwarzwaelder K, et al. Correction of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease by gene therapy, augmented by insertional activation of MDS1-EVI1, PRDM16 or SETBP1. Nat Med. 2006;12:401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavazzana-Calvo M, Payen E, Negre O, et al. Transfusion independence and HMGA2 activation after gene therapy of human beta-thal-assaemia. Nature. 2010;467:318–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wissing S, Galloway NL, Greene WC. HIV-1 Vif versus the APO-BEC3 cytidine deaminases: an intracellular duel between pathogen and host restriction factors. Mol Aspects Med. 2010;31:383–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakayama EE, Shioda T. Anti-retroviral activity of TRIM5 alpha. Rev Med Virol. 2010;20:77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luban J Cyclophilin A, TRIM5, and resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2007;81:1054–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakuma R, Noser JA, Ohmine S, Ikeda Y. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by simian restriction factors, TRIM5alpha and APOBEC3G. Gene Ther. 2007;14:185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stremlau M, Owens CM, Perron MJ, Kiessling M, Autissier P, Sodroski J. The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5alpha restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature. 2004;427:848–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keckesova Z, Ylinen LM, Towers GJ. The human and African green monkey TRIM5alpha genes encode Ref1 and Lv1 retroviral restriction factor activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10780–10785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatziioannou T, Perez-Caballero D, Yang A, Cowan S, Bieniasz PD. Retrovirus resistance factors Ref1 and Lv1 are species-specific variants of TRIM5alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10774–10779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yap MW, Nisole S, Lynch C, Stoye JP. Trim5alpha protein restricts both HIV-1 and murine leukemia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10786–10791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uchida N, Washington KN, Hayakawa J, et al. Development of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-based lentiviral vector that allows efficient transduction of both human and rhesus blood cells. J Virol. 2009;83:9854–9862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uchida N, Hsieh MM, Hayakawa J, Madison C, Washington KN, Tisdale JF. Optimal conditions for lentiviral transduction of engrafting human CD34+ cells. Gene Ther. 2011;18:1078–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uchida N, Washington KN, Lap CJ, Hsieh MM, Tisdale JF. Chicken HS4 insulators have minimal barrier function among progeny of human hematopoietic cells transduced with an HIV1-based lentiviral vector. Mol Ther. 2011;19:133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uchida N, Bonifacino A, Krouse AE, et al. Accelerated lymphocyte reconstitution and long-term recovery after transplantation of lentiviral-transduced rhesus CD34(+) cells mobilized by G-CSF and plerixafor. Exp Hematol. 2011;39:795–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanawa H, Persons DA, Nienhuis AW. Mobilization and mechanism of transcription of integrated self-inactivating lentiviral vectors. J Virol. 2005;79:8410–8421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanawa H, Kelly PF, Nathwani AC, et al. Comparison of various envelope proteins for their ability to pseudotype lentiviral vectors and transduce primitive hematopoietic cells from human blood. Mol Ther. 2002;5:242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanawa H, Hematti P, Keyvanfar K, et al. Efficient gene transfer into rhesus repopulating hematopoietic stem cells using a simian immuno-deficiency virus-based lentiviral vector system. Blood. 2004;103: 4062–4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uchida N, Hanawa H, Dan K, Inokuchi K, Shimada T. Leukemogenesis of b2a2-type p210 BCR/ABL in a bone marrow transplantation mouse model using a lentiviral vector. J Nippon Med Sch. 2009;76:134–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayakawa J, Hsieh MM, Anderson DE, et al. The assessment of human erythroid output in NOD/SCID mice reconstituted with human hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:1465–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tisdale JF, Hanazono Y, Sellers SE, et al. Ex vivo expansion of genetically marked rhesus peripheral blood progenitor cells results in diminished long-term repopulating ability. Blood. 1998;92:1131–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palombella VJ, Rando OJ, Goldberg AL, Maniatis T. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is required for processing the NF-kappa B1 precursor protein and the activation of NF-kappa B. Cell. 1994;78:773–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sutlu T, Nystrom S, Gilljam M, Stellan B, Applequist SE, Alici E. Inhibition of intracellular antiviral defense mechanisms augments lentiviral transduction of human natural killer cells: implications for gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23:1090–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santoni de Sio FR, Gritti A, Cascio P, et al. Lentiviral vector gene transfer is limited by the proteasome at postentry steps in various types of stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2142–2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meriin AB, Gabai VL, Yaglom J, Shifrin VI, Sherman MY. Proteasome inhibitors activate stress kinases and induce Hsp72. Diverse effects on apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6373–6379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz O, Marechal V, Friguet B, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Heard JM. Antiviral activity of the proteasome on incoming human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:3845–3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drexler HC. Activation of the cell death program by inhibition of proteasome function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:855–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grimm LM, Goldberg AL, Poirier GG, Schwartz LM, Osborne BA. Proteasomes play an essential role in thymocyte apoptosis. EMBO J. 1996;15:3835–3844. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uchida N, Hargrove PW, Lap CJ, et al. High-efficiency transduction of rhesus hematopoietic repopulating cells by a modified HIV1-based lentiviral vector. Mol Ther. 2012;20:1882–1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.