Abstract

Background

The circadian clock governs a large variety of fundamentally important physiological processes in all three domains of life. Consequently, asynchrony in timekeeping mechanisms could give rise to cellular dysfunction underpinning many disease pathologies including human neoplasms. Yet, detailed pan-cancer evidence supporting this notion has been limited.

Methods

In an integrated approach uniting genomic, transcriptomic and clinical data of 21 cancer types (n = 18,484), we interrogated copy number and transcript profiles of 32 circadian clock genes to identify putative loss-of-function (ClockLoss) and gain-of-function (ClockGain) players. Kaplan–Meier, Cox regression and receiver operating characteristic analyses were employed to evaluate the prognostic significance of both gene sets.

Results

ClockLoss and ClockGain were associated with tumour-suppressing and tumour-promoting roles respectively. Downregulation of ClockLoss genes resulted in significantly higher mortality rates in five cancer cohorts (n = 2914): bladder (P = 0.027), glioma (P < 0.0001), pan-kidney (P = 0.011), clear cell renal cell (P < 0.0001) and stomach (P = 0.0007). In contrast, patients with high expression of oncogenic ClockGain genes had poorer survival outcomes (n = 2784): glioma (P < 0.0001), pan-kidney (P = 0.0034), clear cell renal cell (P = 0.014), lung (P = 0.046) and pancreas (P = 0.0059). Both gene sets were independent of other clinicopathological features to permit further delineation of tumours within the same stage. Circadian reprogramming of tumour genomes resulted in activation of numerous oncogenic pathways including those associated with cancer stem cells, suggesting that the circadian clock may influence self-renewal mechanisms. Within the hypoxic tumour microenvironment, circadian dysregulation is exacerbated by tumour hypoxia in glioma, renal, lung and pancreatic cancers, resulting in additional death risks. Tumour suppressive ClockLoss genes were negatively correlated with hypoxia inducible factor-1A targets in glioma patients, providing a novel framework for investigating the hypoxia-clock signalling axis.

Conclusions

Loss of timekeeping fidelity promotes tumour progression and influences clinical outcomes. ClockLoss and ClockGain may offer novel druggable targets for improving patient prognosis. Both gene sets can be used for patient stratification in adjuvant chronotherapy treatment. Emerging interactions between the circadian clock and hypoxia may be harnessed to achieve therapeutic advantage using hypoxia-modifying compounds in combination with first-line treatments.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12967-019-1880-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Circadian clock, Hypoxia, Oncogene, Tumour suppressor, Gain-of-function, Loss-of-function, Pan-cancer, Glioma, Renal cancer

Background

Circadian timekeeping is an essential biological process that influences most, if not all, aspects of eukaryotic and prokaryotic physiology. When its fidelity is compromised, circadian dysregulation may not only result in increased disease risks but could also have an effect on patients’ response to therapy. The core oscillator is coordinated by a set of interlocking transcriptional-translational feedback loop. CLOCK and BMAL1 heterodimerise and bind to E-box elements in PERs and CRYs to drive their rhythmic transcription [1–3]. PER and CRY proteins, in turn, inhibit the CLOCK–BMAL1 complex and inhibition is released upon PER and CRY proteolytic degradation [4–6]. Along with additional epigenetic and post-translational modification processes, core clock proteins within the suprachiasmatic nucleus serve to sustain the oscillations of peripheral clocks and rhythmic expression of downstream targets [7].

The effect of circadian asynchrony in tumorigenesis was first reported in the 1960s [8]. Studies in the 1980s demonstrated that endocrine rhythm disruption could accelerate mammary tumour growth in rats [9, 10]. Numerous studies have since shed light on the role of the circadian clock in cancer development in humans. Shift working is thought to be a carcinogen because of dysregulated circadian homeostasis [11, 12]. Circadian dysfunction is also thought to be a cancer risk factor in many organ systems [13–19]. Aberration in circadian homeostasis is also linked to poor performance in anti-tumour regimes [15, 20, 21].

Circadian dysregulation is widespread in cancer, yet, tumour-specific abnormalities of clock genes are far from being understood. To help unravel the intricacies of circadian regulation in diverse cancer types, we employed a comparative approach triangulating genomic, transcriptomic and clinical data to discover molecular underpinnings of circadian dysregulation and their effects on patient prognosis. Our pan-cancer integrated analyses demonstrated that the circadian clock had both tumour-promoting and tumour-suppressing qualities that were cell-type dependent. Tumour hypoxia is linked to disease aggression and therapeutic resistance [22]. Hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs), the master regulators of hypoxia signalling, are transcription factors containing PER-ARNT-SIM domains and are structurally analogous to core clock proteins BMAL1 and CLOCK [23–25], suggesting that both pathways can be coregulated. Indeed, past reports have shown that hypoxic responses are gated by the circadian clock [26, 27]. We found that the crosstalk between tumour hypoxia and circadian dysregulation harboured clinically relevant prognostic information. Overall, we demonstrated that circadian reprogramming of tumour genomes influences disease progression and patient outcomes. This work could provide a key staging point for exploring personalised cancer chronotherapy and potential adjuvant treatment with circadian- and hypoxia-modifying drugs to improve clinical outcomes.

Methods

We retrieved 32 circadian clock genes, which included core clock proteins from the Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database listed in Additional file 1.

Cancer cohorts

Datasets generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas were downloaded from Broad Institute GDAC Firehose [28]. Genomic, transcriptomic and clinical profiles of 21 cancer types and their non-tumour counterparts were downloaded (Additional file 2).

Copy number alterations analyses

Firehose Level 4 copy number variation datasets were downloaded. GISTIC gene-level tables provided discrete amplification and deletion indicators [29]. Samples with ‘deep amplifications’ were identified as those with values higher than the maximum copy-ratio for each chromosome arm (+ 2). Samples with ‘deep deletions’ were identified as those with values lower than the minimum copy-ratio for each chromosome arm (− 2). ‘Shallow amplifications’ and ‘shallow deletions’ were identified from samples with GISTIC indicators of + 1 and − 1 respectively.

Defining ClockLoss and ClockGain gene sets and calculating clock and hypoxia scores

Recurrently deleted/amplified genes were identified from genes that were deleted/amplified in at least 20% of samples within a cancer type and at least one-third of cancers (> seven cancers). Putative loss-of-function genes (ClockLoss) were defined as genes that were recurrently deleted and downregulated in tumour versus non-tumour samples. Putative gain-of-function genes (ClockGain) were defined as genes that were recurrently amplified and upregulated in tumour versus non-tumour samples. ClockLoss genes were CLOCK, CRY2, FBXL3, FBXW11, NR1D2, PER1, PER2, PER3, PRKAA2, RORA and RORB. Clockgain genes were ARNTL2 and NR1D1. For each patient, ClockLoss and ClockGain scores were calculated from the mean log2 expression values of genes within each set. Molecular assessment of tumour hypoxia was performed using a 52-hypoxia gene signature [30]. Hypoxia scores were determined from the mean log2 expression of the 52 genes.

Survival, differential expression and multidimensional scaling analyses

We have published detailed methods for the aforementioned analyses [31], hence, the methods will not be repeated here. Briefly, for survival analyses, patients were separated into survival quartiles based on their ClockLoss and ClockGain scores. Cox proportional hazards regression, Kaplan–Meier and receiver operating characteristic analyses were performed using the R survcomp, survival and survminer packages according to previous methods. For analyses in Fig. 5 investigating the crosstalk between hypoxia and the circadian clock, patients were separated into four groups based on their median clock and hypoxia scores. Nonparametric Spearman’s rank-order correlation analyses were performed to determine the relationship between clock and hypoxia scores in Fig. 5. Circular heatmaps in Fig. 6 were generated from ClockLoss scores and HIF-target genes (CA9, VEGFA and LDHA) log2 expression values in glioma patients. ClockLoss scores were ranked from high (purple) to low (yellow) in the heatmap. HIF-target genes were ranked by decreasing order of ClockLoss scores. Spearman’s correlation analyses were performed on ClockLoss scores and HIF-target genes expression values. Differential expression analyses between tumour and non-tumour samples and between the 4th and 1st quartile patients determined using ClockLoss and ClockGain scores were performed using the Bayes method and linear model followed by Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for adjusting false discovery rates. Multidimensional scaling analyses in Fig. 2 were performed using the R vegan package (Euclidean distance) and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was used to determine statistical difference between tumour and non-tumour samples.

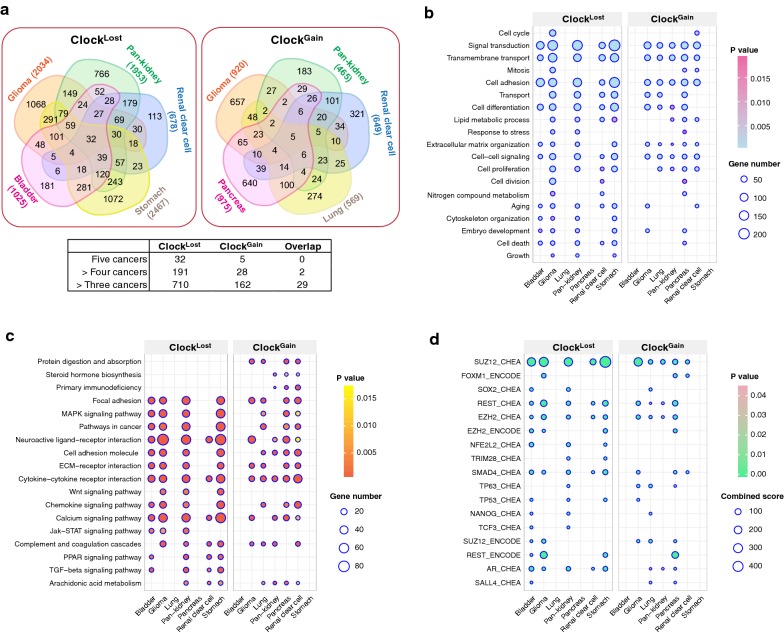

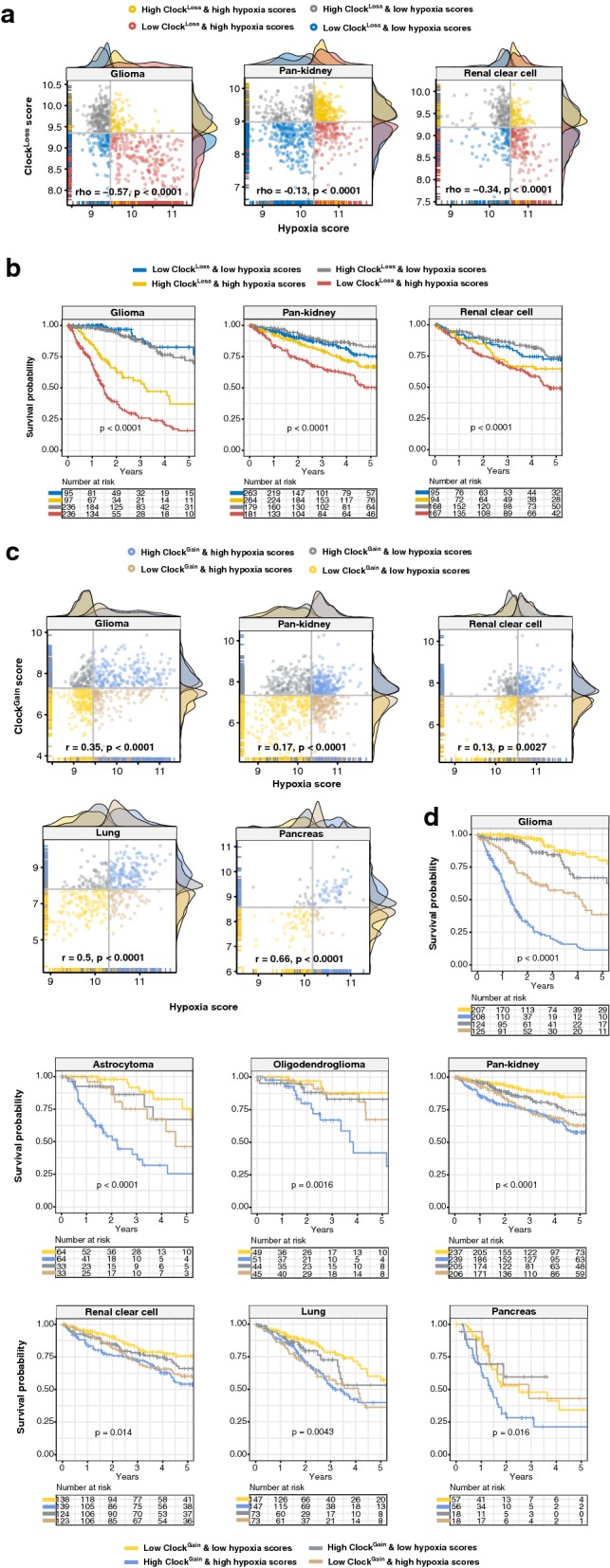

Fig. 5.

Prognostic relevance of the hypoxia and clock crosstalk. Scatter plots depict a significant negative correlations and b significant positive correlations between hypoxia and ClockLoss or ClockGain scores respectively. Patients are grouped into four categories based on median clock and hypoxia scores. At the x- and y-axes, density plots depict the distribution of clock and hypoxia scores. Kaplan–Meier analyses are performed on the four patient groups to determine the effects of crosstalk between hypoxia and c ClockLoss and d ClockGain on overall survival in multiple cancers including glioma histological subtypes

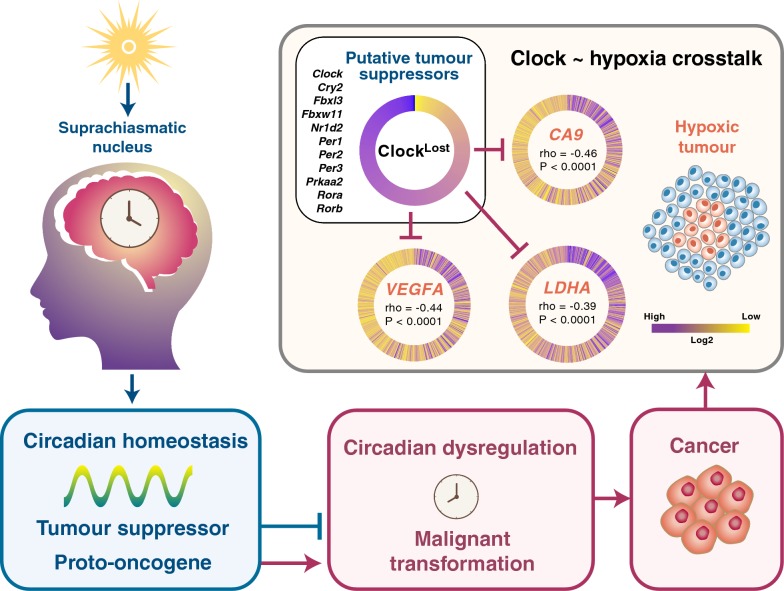

Fig. 6.

Model of the hypoxia-clock signalling axis in glioma. The circadian clock exerts tumour promoting or tumour suppressing qualities that are dependent on cellular types. Tumour suppressive ClockLoss genes are negatively correlated with HIF-1A target genes (CA9, VEGFA and LDHA) in glioma. ClockLoss scores are plotted such that each spoke of the circular heatmap represents individual patients that are sorted in descending order. Circular heatmaps for HIF-1A target genes are plotted with patients sorted in descending order of ClockLoss scores. Spearman’s correlation coefficients between ClockLoss and individual HIF-1A genes are depicted in the centre of the heatmap

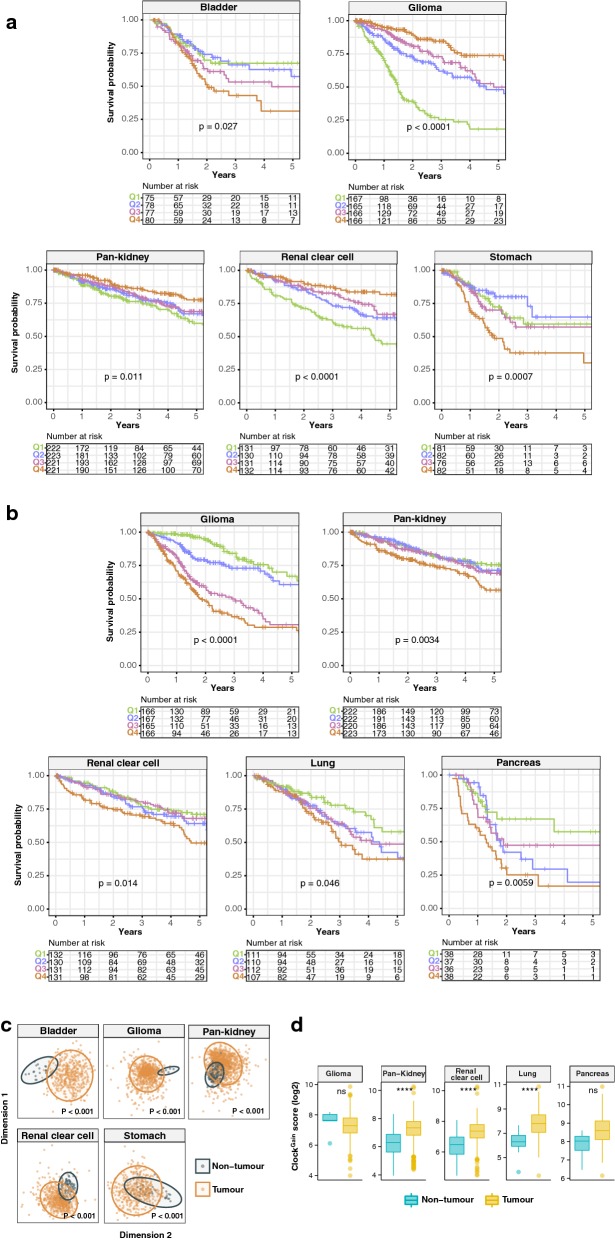

Fig. 2.

Prognostic significance of ClockLoss and ClockGain. Kaplan–Meier plots are generated using a ClockLoss and b ClockGain. Patients are quartile stratified based on their clock gene scores. P values are obtained from log-rank tests. c Ordination plots of multidimensional scaling analyses using ClockLoss genes reveal significant differences between tumour and non-tumour samples. P values are obtained from PERMANOVA tests. d Expression distribution of ClockGain scores in tumour and non-tumour samples with statistical analyses performed using Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon tests. P values are represented by ****< 0.00001. ns non-significant

Pathway enrichment and transcription factor analyses

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were fed into GeneCodis [32] and Enrichr [33, 34]. Using GeneCodis, DEGs were mapped against the KEGG and Gene Ontology databases. To determine whether DEGs were enriched for targets of stem cell-related transcription factors, Enrichr was used to map DEGs to ENCODE and ChEA chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing profiles.

All plots were generated using R pheatmap and ggplot2 packages.

Results

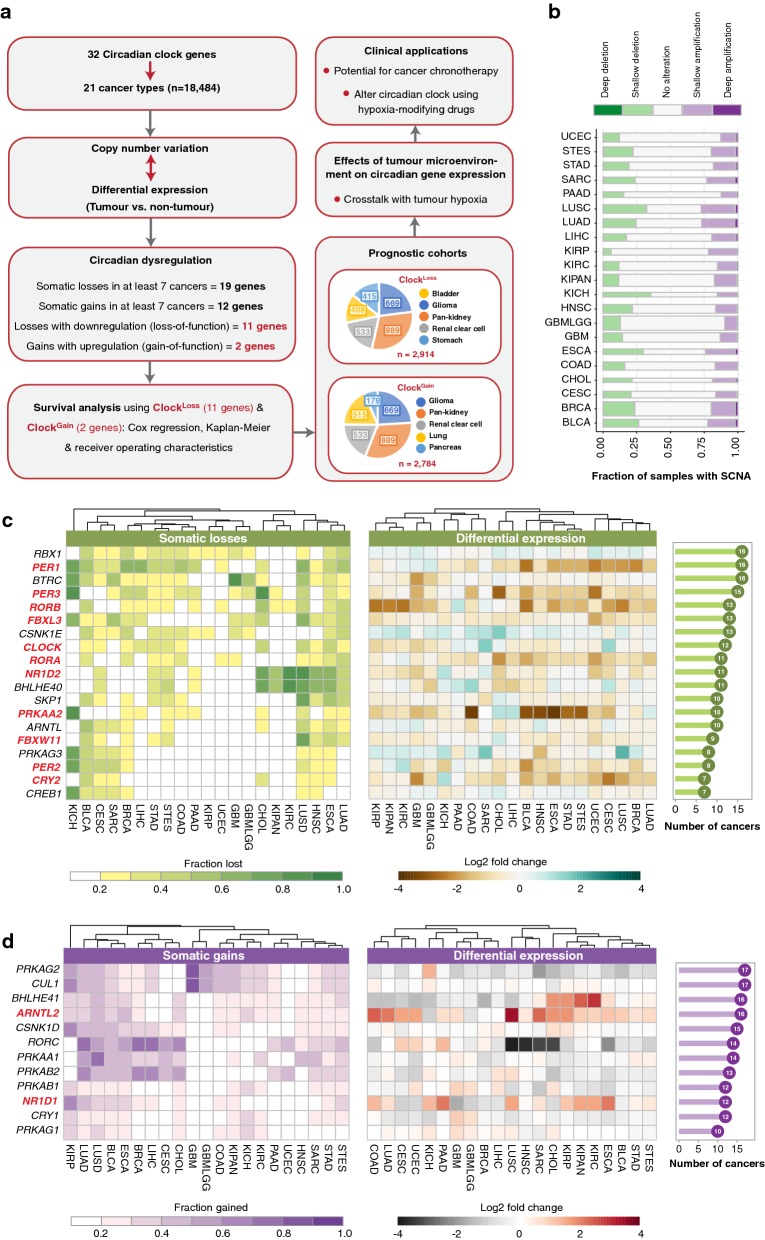

Integrated genomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal conserved patterns of putative loss-and gain-of-function mutations in circadian clock genes

We retrieved 32 genes representing core circadian clock components from Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (Additional file 1). To determine the extent of circadian dysregulation across diverse malignancies, we analysed tumour copy number and mRNA differential expression profiles (tumour versus non-tumour) of 18,484 samples across 21 cancer types (Additional file 1) (Fig. 1a). Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (KICH) exhibited the highest fraction of samples harbouring deleted clock genes (Fig. 1b). This was in contrast with another kidney cancer subtype, papillary renal cell carcinoma (KIRP), which had the lowest frequency of somatic deletions (Fig. 1b). When considering somatic amplifications, we observed that this was the highest in lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) and the lowest in glioma (GBMLGG) (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Circadian reprogramming in diverse cancer types. a Schematic diagram depicting the project design and the identification of putative loss-of-function and gain-of-function clock genes. Somatic copy number alteration (SCNA) and transcript expression of 32 clock genes are investigated in 21 cancer types. A total of 19 or 12 genes are recurrently lost or gained respectively. Of these SCNA events, 11 or two genes are also downregulated or upregulated in tumours, representing ClockLoss and ClockGain gene sets respectively. Both gene sets are prognostic in seven cancer cohorts. Pie slices indicate the number of patients within each cancer type. Crosstalk between circadian genes and tumour hypoxia is investigated. b The proportion of samples with deep and shallow somatic alterations are represented using stacked bar graphs. The number of samples within each cancer type is represented by the width of the stacked bars. c Somatic losses and differential expression profiles of 19 clock genes that are recurrently deleted in at least seven cancer types. d Somatic gains and differential expression profiles of 12 clock genes that are recurrently amplified in at least seven cancer types. Bar charts on the far right represent the number of cancers with at least 20% of samples affected by copy number alteration. Heatmaps on the far left depict the cohort fraction in which a given gene is deleted or amplified. Cancer types are ordered using Euclidean distance metric. Heatmaps in the centre represent differential expression values between tumour and non-tumour samples. ClockLoss and ClockGain genes are highlighted in red. Cancer abbreviations are listed in Additional file 2

At an individual gene level, somatic deletions were observed in 19 circadian clock genes in at least 20% of samples within a cancer type and at least one-third of cancer types (> seven cancers) (Fig. 1a, c). Global somatic losses were observed in core circadian pacemaker genes, PER1, PER2, PER3, ARNTL (BMAL1), CLOCK, NR1D2 (REV-ERBB), RORA and RORB (Fig. 1c). For instance, PER1 was deleted in 16 cancers, while PER3 and CLOCK were lost in 15 and 12 cancers respectively (Fig. 1c). On the other hand, a distinct set of 12 genes exhibited global patterns of somatic gains, which included core clock genes namely ARNTL2 (BMAL2), CRY1, NR1D1 (REV-ERBA) and RORC (Fig. 1d). ARNTL2 was one of the most amplified genes found in 16 cancers, followed by RORC in 14 cancers and NR1D1 and CRY1 in 12 cancers each (Fig. 1d).

Somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) associated with differential transcript expression may represent putative loss- or gain-of-function events. Somatic losses accompanying transcript downregulation in tumours could indicate a loss-of-function and vice versa, somatic gains linked to transcript upregulation could imply a gain-of-function. Differential expression analyses between tumour and non-tumour samples were performed to identify genes that were significantly altered in tumours (> 1.5-fold-change, P < 0.05) of at least seven cancer types (Fig. 1c, d). Of genes that exhibited SCNAs, 11 and two genes were associated with putative loss-of-function and gain-of-function phenotypes respectively (Fig. 1a, c, d).

Tumour suppressive and oncogenic potential of the circadian clock are context dependent

Given their global patterns spanning multiple cancer types, we reason that putative loss- and gain-of-function phenotypes would impact patient prognosis. We hypothesize that loss-of-function genes could have tumour suppressive qualities where gene deletions may give rise to cancer. On the contrary, gain-of-function genes are likely to harbour tumour promoting properties. If this is true, patients with low expression of loss-of-function genes (ClockLoss) would have poorer clinical outcomes. Likewise, high expression of gain-of-function genes (ClockGain) would be associated with more advanced disease states and poorer outcomes. To evaluate the effects of ClockLoss and ClockGain on overall survival, each patient was assigned a score based on the average expression values of 11 and two genes respectively: ClockLoss genes (CLOCK, CRY2, FBXL3, FBXW11, NR1D2, PER1, PER2, PER3, PRKAA2, RORA and RORB); ClockGain genes (ARNTL2 and NR1D1). For Kaplan–Meier analyses, patients were separated into survival quartiles based on their ClockLoss and ClockGain scores. Intriguingly, we found that both gene sets conferred prognostic information in seven cancer cohorts, allowing the stratification of patients into risk groups based on circadian dysregulation (Fig. 2a, b). ClockLoss was prognostic in five cohorts: bladder (P = 0.027), glioma (P < 0.0001), pan-kidney (consisting of chromophobe renal cell, clear cell renal cell and papillary renal cell carcinoma; P = 0.011), clear cell renal cell (P < 0.0001) and stomach (P = 0.0007) (Fig. 2a). Likewise, ClockGain was also prognostic in glioma (P < 0.0001), pan-kidney (P = 0.0034) and clear cell renal cell (P = 0.014) cohorts and two additional cohorts; lung (P = 0.046) and pancreas (P = 0.0059) (Fig. 2b).

Interestingly, we observed that patients within the 4th quartile (highest ClockLoss scores) had the lowest mortality rates in glioma (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.188, P < 0.0001), pan-kidney (HR = 0.520, P = 0.001) and clear cell renal cell (HR = 0.292, P < 0.0001) cohorts (Table 1). This supports our initial hypothesis that downregulation/loss-of-function of putative tumour suppressive clock genes were linked to adverse clinical outcomes while patients with high expression of these genes would perform better. However, this was not the case for bladder (HR = 2.081, P = 0.0093) and stomach (HR = 2.155, P = 0.0054) cancers, where patients with high ClockLoss scores (4th quartile) had increased death risks, suggesting that the function of ClockLoss is tumour-type dependent (Table 1). In terms of ClockGain, high expression levels were consistently associated with increased mortality rates in all five cohorts, supporting the hypothesis on tumour-promoting effects of these genes: glioma (HR = 3.961, P < 0.0001), pan-kidney (HR = 1.890, P = 0.00066), clear cell renal cell (HR = 1.755, P = 0.0062), lung (HR = 2.023, P = 0.006) and pancreas (HR = 3.034, P = 0.0022) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses demonstrating the independence of ClockLoss or ClockGain from other clinicopathological features

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| All gliomas (ClockLost) | Univariate | |

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 0.393 (0.285–0.543) | < 0.0001 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 0.274 (0.193–0.387) | < 0.0001 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 0.188 (0.127–0.278) | < 0.0001 |

| All gliomas (ClockGain) | Univariate | |

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 1.272 (0.813–1.991) | 0.29 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 2.931 (1.951–4.402) | < 0.0001 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 3.961 (2.668–5.882) | < 0.0001 |

| Astrocytoma (ClockGain) | Univariate | |

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 0.59 (0.242–1.468) | 0.26 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.423 (0.65–3.109) | 0.38 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 3.048 (1.514–6.137) | 0.0018 |

| Oligodendroglioma (ClockGain) | Univariate | |

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 0.947 (0.362–2.474) | 0.91 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.184 (0.475–2.951) | 0.72 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 2.764 (1.194–6.400) | 0.018 |

| Pan-kidney (ClockLost) | Univariate | |

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 0.783 (0.547–1.121) | 0.18 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 0.801 (0.568–1.131) | 0.21 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 0.520 (0.352–0.768) | 0.001 |

| TNM staging | 2.095 (1.858–2.361) | < 0.0001 |

| Multivariate | ||

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 0.783 (0.543–1.129) | 0.18 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 0.764 (0.537–1.089) | 0.14 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 0.569 (0.383–0.847) | 0.0055 |

| TNM staging | 2.085 (1.848–2.354) | < 0.0001 |

| Pan-kidney (ClockGain) | Univariate | |

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 1.237 (0.838–1.825) | 0.28 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.222 (0.828–1.803) | 0.31 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 1.890 (1.311–2.725) | 0.00066 |

| Multivariate | ||

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 1.177 (0.790–1.752) | 0.42 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.429 (0.961–2.124) | 0.078 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 1.941 (1.333–2.826) | 0.00054 |

| TNM staging | 2.092 (1.857–2.357) | < 0.0001 |

| Clear cell renal cell (ClockLost) | Univariate | |

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 0.608 (0.416–0.888) | 0.01 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 0.546 (0.361–0.795) | 0.0019 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 0.292 (0.179–0.474) | < 0.0001 |

| TNM staging | 1.87 (1.641–2.132) | < 0.0001 |

| Multivariate | ||

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 0.653 (0.447–0.955) | 0.027 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 0.667 (0.448–0.993) | 0.046 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 0.433 (0.265–0.708) | 0.00085 |

| TNM staging | 1.798 (1.572–2.058) | < 0.0001 |

| Clear cell renal cell (ClockGain) | Univariate | |

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 1.243 (0.799–1.933) | 0.33 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.001 (0.640–1.564) | 0.99 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 1.775 (1.177–2.678) | 0.0062 |

| Multivariate | ||

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 1.222 (0.786–1.901) | 0.37 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.284 (0.818–2.017) | 0.28 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 1.856 (1.230–2.802) | 0.0032 |

| TNM staging | 1.874 (1.642–2.138) | < 0.0001 |

| Bladder (ClockLost) | Univariate | |

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 1.088 (0.593–1.999) | 0.78 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.478 (0.828–2.640) | 0.19 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 2.081 (1.198–3.614) | 0.0093 |

| TNM staging | 1.679 (1.323–2.131) | < 0.0001 |

| Multivariate | ||

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 1.059 (0.577–1.946) | 0.85 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.357 (0.759–2.426) | 0.31 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 1.776 (1.018–3.099) | 0.043 |

| TNM staging | 1.609 (1.263–2.050) | 1.20E−04 |

| Stomach (ClockLost) | Univariate | |

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 0.761 (0.389–1.485) | 0.43 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.143 (0.615–2.127) | 0.67 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 2.155 (1.255–3.702) | 0.0054 |

| TNM staging | 1.372 (1.067–1.765) | 0.038 |

| Multivariate | ||

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 0.731 (0.374–1.428) | 0.36 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.133 (0.609–2.107) | 0.69 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 2.070 (1.205–3.557) | 0.0084 |

| TNM staging | 1.354 (1.054–1.739) | 0.018 |

| Lung (ClockGain) | Univariate | |

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 1.633 (0.987–2.699) | 0.056 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.604 (0.973–2.644) | 0.064 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 2.023 (1.224–3.343) | 0.006 |

| TNM staging | 1.597 (1.364–1.870) | < 0.0001 |

| Multivariate | ||

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 1.604 (0.971–2.652) | 0.065 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.434 (0.868–2.370) | 0.16 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 1.832 (1.108–3.029) | 0.018 |

| TNM staging | 1.584 (1.348–1.861) | < 0.0001 |

| Pancreas (ClockGain) | Univariate | |

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 1.791 (0.849–3.779) | 0.13 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.602 (0.740–3.470) | 0.23 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 3.034 (1.492–6.168) | 0.0022 |

| TNM staging | 1.339 (0.897–1.998) | 0.153 |

| Multivariate | ||

| Q2 vs. Q1 | 1.712 (0.803–3.652) | 0.16 |

| Q3 vs. Q1 | 1.584 (0.731–3.430) | 0.24 |

| Q4 vs. Q1 | 2.890 (1.399–5.970) | 0.0042 |

| TNM staging | 1.143 (0.756–1.728) | 0.52 |

Given the prognostic significance of ClockLoss and ClockGain, we predict that their expression profiles would differ between tumour and non-tumour samples in these cancers. Indeed, as confirmed by multidimensional scaling analyses using ClockLoss, there was a clear separation between tumour and non-tumour samples in all five cohorts, suggesting that circadian dysregulation is a hallmark of cancerous cells (Fig. 2c). Since ClockGain only involved two genes, we employed the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test to compare the distribution of ClockGain scores in tumour and non-tumour samples. ClockGain was significantly upregulated in pan-kidney (P < 0.00001), clear cell renal cell (P < 0.00001) and lung cancer cohorts (P < 0.00001) (Fig. 2d). Glioma and pancreatic cancer cohorts had limited number of non-tumour samples, five and four samples respectively. Because of this, we did not observe any significant upregulation of ClockGain in these tumours (Fig. 2d).

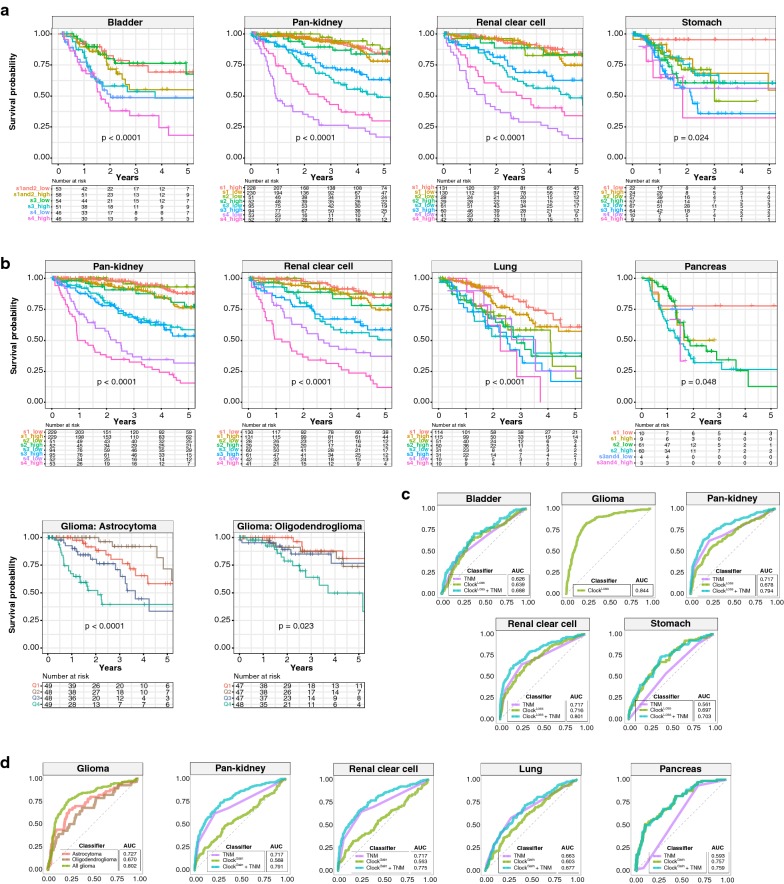

ClockLoss and ClockGain are independent prognostic factors

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression was used to determine whether ClockLoss and ClockGain were independent of other clinicopathological features. Despite accounting for tumour, node and metastasis (TNM) staging, both gene sets remained independent predictors of overall survival; ClockLoss: bladder (HR = 1.776, P = 0.043), pan-kidney (HR = 0.569, P = 0.0055), clear cell renal cell (HR = 0.433, P = 0.00085), stomach (HR = 2.070, P = 0.0084) and ClockGain: pan-kidney (HR = 1.941, P = 0.00054), clear cell renal cell (HR = 1.856, P = 0.0032), lung (HR = 1.832, P = 0.018) and pancreas (HR = 2.890, P = 0.0042) (Table 1). The glioma cohort consisted of low- and high-grade subtypes. ClockGain remained a prognostic factor in histological subtypes of astrocytoma (HR = 3.048, P = 0.0018) and oligodendroglioma (HR = 2.764, P = 0.018) (Table 1). Since both gene sets were independent of tumour stage, we evaluated their ability to improve the resolution of TNM staging. Kaplan–Meier analyses revealed that further delineation of risk groups within similarly staged tumours is afforded by both gene sets; ClockLoss: bladder (P < 0.0001), pan-kidney (P < 0.0001), clear cell renal cell (P < 0.0001), stomach (P = 0.024) (Fig. 3a) and ClockGain: pan-kidney (P < 0.0001), clear cell renal cell (P < 0.0001), lung (P < 0.0001), pancreas (P = 0.048), astrocytoma (P < 0.0001) and oligodendroglioma (P = 0.023) (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

ClockLoss and ClockGain are independent of tumour stage. Kaplan–Meier plots are generated from patients stratified according to TNM stage and a ClockLoss and b ClockGain. TNM staging is first used to stratify patients, followed by median stratification into high- and low-score groups using ClockLoss or ClockGain. b Glioma histological subtypes, astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma, are quartile stratified using ClockGain. P values are obtained from log-rank tests. ROC analyses on c ClockLoss and d ClockGain to determine the specificity and sensitivity of both gene sets in predicting 5-year overall survival rates. ROC curves generated from clock gene sets are compared to those generated from TNM staging. AUCs for TNM stage are in accordance with previous work utilising TCGA datasets [69–71]

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were employed to determine the predictive performance of ClockLoss and ClockGain in comparison to TNM staging. Circadian gene sets were superior to TNM staging in predicting 5-year overall survival; ClockLoss: bladder (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.639 vs. 0.626), stomach (AUC = 0.697 vs. 0.561) and ClockGain: pancreas (AUC = 0.757 vs. 0.593) (Fig. 3c, d). Importantly, when clock gene sets and TNM staging were considered as a combined model, predictive performance was greater than clock genes or TNM when measured separately; ClockLoss: bladder (AUC = 0.688), pan-kidney (AUC = 0.794), clear cell renal cell (AUC = 0.801), stomach (AUC = 0.703) and ClockGain: pan-kidney (AUC = 0.791), clear cell renal cell (AUC = 0.775), lung (AUC = 0.677) and pancreas (AUC = 0.759) (Fig. 3c, d). Within the glioma cohort, AUCs for ClockLoss and ClockGain were 0.844 and 0.727 respectively (Fig. 3c, d). ClockGain was a prognostic indicator in glioma subtypes and ROC analyses confirmed its predictive performance in astrocytoma (AUC = 0.727) and oligodendroglioma (AUC = 0.670) (Fig. 3d).

Dysregulated circadian timekeeping is associated with malignant progression

To further investigate the underpinning biological consequences of circadian clock dysregulation and determine how they link to unfavourable patient outcomes, we performed differential expression analyses on all transcripts to determine genes that were altered as a result of circadian perturbation by comparing patients from the 4th survival quartile to those from the 1st quartile. Interestingly, patients stratified using ClockLoss had significantly higher number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs; − 1.5 > log2 fold change > 1.5; P < 0.01) (Fisher’s exact test, P = 2.2e−16) compared to ClockGain (Fig. 4a) (Additional file 3). Many DEGs were found to be in common between cancer types, more so for ClockLoss, suggesting the existence of conserved signalling cascades associated with circadian dysregulation in driving disease pathogenesis (Fig. 4a; Additional file 3). Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG functional enrichment analyses revealed that circadian reprogramming of tumours resulted in the activation of a myriad of oncogenic pathways. Signalling pathways associated with cancer stem cell function (MAPK, Wnt, JAK-STAT [35], TGF-β and PPAR [36]), metabolism, cell adhesion, cell proliferation, cell death, transmembrane transport and extracellular matrix organisation were among some of the most altered biological processes that likely underpin tumour aggression and decreased survival in these patients (Fig. 4b, c). Interestingly, with the exception of MAPK signalling, pathways associated with cancer stem cell function were only enriched in patients stratified using ClockLoss, suggesting that ClockLoss genes are keenly linked to stem cell homeostasis (Fig. 4c). To further understand how DEGs were regulated, we analysed transcription factor (TF) binding using Enrichr and observed that DEGs were enriched for targets of TFs associated with self-renewal and cancer stem cell function (SUZ12, SOX2, REST, EZH2, SMAD4 and NANOG) (Fig. 4d). These TFs have previously been shown to promote metastasis, disease aggression and cancer stem cell maintenance [37–39].

Fig. 4.

Circadian dysregulation drives malignant progression. Differential expression analyses are performed between 4th and 1st quartile patients determined using ClockLoss or ClockGain. a Venn diagrams illustrate the number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and their overlapping patterns in five cohorts. Numbers in parentheses represent DEGs. Table inset depicts the number of genes that are found to be in common in five, > four and > three cancer types. Overlap between common ClockLoss and ClockGain genes are also depicted. Enriched b GO terms, c KEGG ontologies and d transcription factor binding associated with DEGs

Disease phenotypes of tumours with deranged circadian homeostasis are aggravated by hypoxia

Circadian oscillations of physiological processes such as metabolism, temperature and cortisol levels are affected by oxygen levels [40–42]. Hypoxic responses are gated by the circadian clock and at the genomic level, BMAL1 and HIF-1A synergistically interact to coregulate downstream genes [27]. Crosstalk between hypoxia and the clock has profound implications on cancer pathophysiology [43, 44]. We reason that tumour hypoxia could synergise with the circadian clock to impact disease progression. To determine the extent of the hypoxia-clock crosstalk, a hypoxia gene signature consisting of 52 genes was employed to calculate hypoxia scores in each patient [30]. Remarkably, we observed significant negative correlations between hypoxia and ClockLoss scores in glioma (rho = − 0.57, P < 0.0001), pan-kidney (rho = − 0.13, P < 0.0001) and clear cell renal cell (rho = − 0.34, P < 0.0001) cohorts (Fig. 5a). Patients were separated into four groups based on their hypoxia and ClockLoss scores for survival analyses. Kaplan–Meier analyses employing the joint hypoxia-ClockLoss model revealed that patients with more hypoxic tumours who concurrently had lower levels of ClockLoss genes performed the worst: glioma (HR = 7.218, P < 0.0001), pan-kidney (HR = 2.512, P < 0.0001) and clear cell renal cell (HR = 1.893, P = 0.0054) (Fig. 5b) (Table 2). This observation is consistent with the predicted tumour suppressive roles of ClockLoss.

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazards regression analyses on the relationship between hypoxia and ClockLoss or ClockGain on overall survival

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Glioma (ClockLoss) | ||

| Low ClockLoss and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockLoss and low hypoxia score | 7.218 (4.234–12.304) | < 0.0001 |

| High ClockLoss and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockLoss and low hypoxia score | 3.138 (1.733–5.683) | 0.00016 |

| High ClockLoss and low hypoxia score vs. low ClockLoss and low hypoxia score | 1.114 (0.617–2.014) | 0.72 |

| Pan-kidney (ClockLoss) | ||

| Low ClockLoss and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockLoss and low hypoxia score | 2.512 (1.732–3.643) | < 0.0001 |

| High ClockLoss and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockLoss and low hypoxia score | 1.580 (1.094–2.282) | 0.0148 |

| High ClockLoss and low hypoxia score vs. low ClockLoss and low hypoxia score | 0.695 (0.423–1.122) | 0.14 |

| Clear cell renal cell (ClockLoss) | ||

| Low ClockLoss and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockLoss and low hypoxia score | 1.893 (1.207–2.969) | 0.0054 |

| High ClockLoss and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockLoss and low hypoxia score | 1.285 (0.761–2.170) | 0.35 |

| High ClockLoss and low hypoxia score vs. low ClockLoss and low hypoxia score | 0.796 (0.479–1.324) | 0.38 |

| Glioma (ClockGain) | ||

| High ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 9.210 (6.182–13.721) | < 0.0001 |

| High ClockGain and low hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 1.550 (0.917–2.622) | 0.11 |

| Low ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 3.317 (2.105–5.228) | < 0.0001 |

| Astrocytoma (ClockGain) | ||

| High ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 5.684 (2.770–11.662) | < 0.0001 |

| High ClockGain and low hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 1.451 (0.527–3.998) | 0.47 |

| Low ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 2.378 (0.985–5.736) | 0.054 |

| Oligodendroglioma (ClockGain) | ||

| High ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 4.085 (1.656–10.068) | 0.0022 |

| High ClockGain and low hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 1.218 (0.439–3.374) | 0.71 |

| Low ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 1.541 (0.581–4.091) | 0.38 |

| Pan-kidney (ClockGain) | ||

| High ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 3.079 (2.040–4.646) | < 0.0001 |

| High ClockGain and low hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 1.742 (1.089–2.785) | 0.021 |

| Low ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 2.823 (1.850–4.307) | < 0.0001 |

| Clear cell renal cell (ClockGain) | ||

| High ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 1.877 (1.222–2.884) | 0.0041 |

| High ClockGain and low hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 1.189 (0.742–1.908) | 0.47 |

| Low ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 1.630 (1.043–2.546) | 0.032 |

| Lung (ClockGain) | ||

| High ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 2.037 (1.327–3.129) | 0.0012 |

| High ClockGain and low hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 1.332 (0.755–2.351) | 0.33 |

| Low ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 1.995 (1.221–3.258) | 0.0058 |

| Pancreas (ClockGain) | ||

| High ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 1.976 (1.163–3.357) | 0.012 |

| High ClockGain and low hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 0.852 (0.344–2.110) | 0.73 |

| Low ClockGain and high hypoxia score vs. low ClockGain and low hypoxia score | 0.893 (0.397–2.009) | 0.79 |

Significant P values are marked in italics

CI confidence interval

The trend is flipped when considering ClockGain; significant positive correlations between hypoxia and ClockGain scores were observed in glioma (rho = 0.35, P < 0.0001), pan-kidney (rho = 0.17, P < 0.0001), clear cell renal cell (rho = 0.13, P = 0.0027), lung (rho = 0.50, P < 0.0001) and pancreas (rho = 0.66, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5c). Consistently, patients with more hypoxic tumours and high ClockGain scores had the poorest survival outcomes: glioma (HR = 9.210, P < 0.0001), astrocytoma (HR = 5.684, P < 0.0001), oligodendroglioma (HR = 4.085, P = 0.0022), pan-kidney (HR = 3.079, P < 0.0001), clear cell renal cell (HR = 1.877, P = 0.0041), lung (HR = 2.037, P = 0.0012) and pancreas (HR = 1.976, P = 0.012) (Fig. 5d) (Table 2). Loss of tumour suppression or increase in tumour promoting properties resulted from circadian dysregulation is further exacerbated by hypoxia. The clock-hypoxia model may be used for delineation of patients into additional risk groups to support adjuvant therapy with hypoxia-reducing drugs in combination with mainstream chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Discussion

Disruption of circadian homeostasis is frequently observed in tumour cells. In a comprehensive study of circadian clock genes in 21 cancer types that takes into account genomic, transcriptomic and phenotypic (clinical prognosis) data, we demonstrated that clock genes were substantially altered by somatically acquired deletions and amplifications. Recurrent deletions or amplifications that were accompanied by altered transcript expression in tumours could represent novel loss- or gain-of-function phenotypes. To exploit these circadian targets in a clinical setting, we analysed survival outcomes using the ClockLoss and ClockGain and confirmed the utility of both gene sets as prognostic tools in 2914 and 2784 patients involving seven diverse cancer cohorts.

Depending on cellular context, the circadian clock can exert both tumour-promoting or tumour-inhibiting properties. We observed that core clock genes, PERs, CRY2, CLOCK, NR1D2, RORA and RORB exhibited global patterns of somatic loss and downregulation across multiple tumour types (Fig. 1c). We demonstrated that loss-of-function of these genes resulted in increased death risks in patients, which highlight their protective roles (Figs. 2, 3). However, tumour suppressive qualities appear to be cancer type-specific; ClockLoss genes were associated with adverse survival outcomes in bladder and stomach cancers (Figs. 2, 3). A study on breast cancer revealed that CpG methylation on PER promoters is responsible for PER deregulation in tumours [45]. PER2 enhances estrogen receptor-α (ERα) degradation leading to growth inhibition of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer [46]. Studies on glioma [47], head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [48], lung [49], colorectal [50] and liver cancers [51] demonstrated that PERs, CRYs and BMAL1 are downregulated in tumours and are likely to harbour tumour suppressing qualities. BMAL1 overexpression increases the sensitivity of colorectal cancer cells to oxaliplatin by ATM pathway activation [15]. Overexpression of PER2 in pancreatic cancer cells inhibits cellular proliferation, increases apoptotic rates and had a synergistic effect with cisplatin [20]. BMAL1 binds to TP53 promoter to induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells in a TP53-dependent fashion [52]. Additional examples on tumour suppressive functions of clock genes are elegantly reviewed by Fu et al. [53].

We demonstrated that a non-overlapping subset of circadian clock genes, known as ClockGain, were somatically amplified and upregulated in tumours. To our knowledge, most reports on circadian dysregulation in cancer have focused on the pacemaker’s tumour suppressive roles. Nonetheless, evidence on its oncogenic potential has started to emerge. CLOCK expression levels are higher in more aggressive ERα-positive compared to ERα-negative breast tumours and estrogen promotes the binding of ERα to estrogen-response elements in the CLOCK promoter [54]. CRY2 is overexpressed in colorectal cancer samples that are resistant to chemotherapy [21]. CRY2 is linked to poor survival outcomes and its silencing could increase sensitivity to oxaliplatin [21]. Upregulation of PER2 and CRY1 in gastric cancer and CRY1 in colorectal cancer correlate with more advanced disease states and lymph node metastasis [55, 56]. CLOCK expression is increased in high-grade glioma tissues and is required for glioma progression through modulation of NF-κB activity [57]. CLOCK and BMAL1 are required for acute myeloid leukaemia cell growth and leukaemia stem cell maintenance [58].

Circadian reprogramming of tumours is closely associated with metabolic perturbations, activation of cell proliferation, induction of cancer stem cell self-renewal pathways (Wnt/β-catenin, JAK-STAT and TGF-β) and enrichment of binding targets of self-renewal TFs (Fig. 4). Circadian disruption in mouse xenograft models results in tumour progression through Wnt10A-dependent activation of angio- and stromagenesis [59]. BMAL1 overexpression promotes mouse embryonic fibroblast cell proliferation by Wnt signalling activation [60]. In acute myeloid leukaemia, maintenance of circadian homeostasis is required for leukaemia stem cell self-renewal and inhibition of BMAL1 results in the downregulation of β-catenin and other TFs involved in self-renewal [58]. BMAL1 loss also causes stem cell arrhythmia in squamous cell tumours [61]. Taken together, the role of the circadian clock in stem cell homeostasis is likely to be conserved across multiple tissue types.

Equally important, we demonstrated that tumour hypoxia further aggravates the extent of circadian dysregulation resulting in increased death risks, suggesting that interactions between PER-ARNT-SIM components of both circadian and hypoxia pathways could synergistically influence disease progression. The expression of clock genes with putative tumour suppressive properties (ClockLoss) is negatively correlated with tumour hypoxia (Figs. 5a, b, 6). On the other hand, tumour promoting ClockGain genes were positively correlated with hypoxia (Fig. 5c, d). PER1 and CLOCK levels are elevated when mouse brain is exposed to hypoxia [62]. VHL, a protein involved in proteasomal degradation of HIFs, is frequently mutated in renal cancers and consequently, this results in HIF accumulation leading to the induction of pro-angiogenic factors and malignant progression [63]. HIF-1A promotes the amplitude of PER2 rhythms in renal cancer [64]. Considering the high degree of sequence similarities between HIF-1A ([A/G]CGTG) and BMAL1 (CACGTG) binding motifs, it is not surprising that HIF-1A and BMAL1 co-occupy ~ 30% of all genomic loci [27]. Indeed, we observed significant negative correlations between ClockLoss and HIF-1A targets (CA9, VEGFA and LDHA) in glioma (Fig. 6). Reduction in tumour protective effects of ClockLoss coupled with elevated HIF signalling could, together, help explain the significant increase in mortality rates in glioma patients (Fig. 6). These results are supported by another study on breast cancer where hypoxia is negatively correlated with PER2 expression and promotes PER2 degradation to stimulate epithelial-mesenchymal transition [65].

Conclusion

One of the key strengths of the comparative approach we took was that it reveals non-mutually exclusive oncogenic and tumour suppressive properties of the circadian clock. Genes that confer tumour attenuating effects in one cancer type could very well play an opposing role in another cancer type. We confirmed prognostic values of two circadian gene sets in seven cancer cohorts including difficult-to-treat cancers such as glioma and pancreatic cancer; these genes may be prioritised as new therapeutic targets. Although prospective analysis is needed, we anticipate that our findings will provide an important framework for cancer chronotherapy initiatives [66–68] by enabling patient stratification based on circadian biomarkers to enhance therapeutic success. Moreover, therapeutic modification of the clock should help lessen the damage caused by tumour hypoxia. Likewise, it will be important to investigate whether manipulating hypoxia levels could improve adjuvant chronotherapy when used in combination with first-line treatments.

Additional files

Additional file 1. List of 32 circadian clock genes.

Additional file 2. List of TCGA tumour and non-tumour samples in 21 cancer types.

Additional file 3. Differentially expressed genes between patients separated by ClockLoss or ClockGain into 4th and 1st quartiles.

Authors’ contributions

AGL designed the study and supervised the research. WHC and AGL analysed the data, interpreted the results and wrote the initial manuscript draft. AGL revised the manuscript draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- ClockLoss

putative loss-of-function clock genes

- ClockGain

putative gain-of-function clock genes

- HIF

hypoxia inducible factor

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes

- PERMANOVA

permutational multivariate analysis of variance

- DEG

differentially expressed genes

- SCNA

somatic copy number alteration

- HR

hazard ratio

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

area under the curve

- TNM

tumour, node and metastasis

- CI

confidence interval

Contributor Information

Wai Hoong Chang, Email: changwaihoong@gmail.com.

Alvina G. Lai, Email: Alvina.Lai@ndm.ox.ac.uk, Email: alvinagracelai@gmail.com

References

- 1.Young MW, Kay SA. Time zones: a comparative genetics of circadian clocks. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:702. doi: 10.1038/35088576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowrey PL, Takahashi JS. Genetics of the mammalian circadian system: photic entrainment, circadian pacemaker mechanisms, and posttranslational regulation. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:533–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunlap JC. Molecular bases for circadian clocks. Cell. 1999;96:271–290. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kume K, Zylka MJ, Sriram S, Shearman LP, Weaver DR, Jin X, et al. mCRY1 and mCRY2 are essential components of the negative limb of the circadian clock feedback loop. Cell. 1999;98:193–205. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Der Horst GTJ, Muijtjens M, Kobayashi K, Takano R, Kanno S, Takao M, et al. Mammalian Cry1 and Cry2 are essential for maintenance of circadian rhythms. Nature. 1999;398:627. doi: 10.1038/19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vitaterna MH, Selby CP, Todo T, Niwa H, Thompson C, Fruechte EM, et al. Differential regulation of mammalian period genes and circadian rhythmicity by cryptochromes 1 and 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:12114–12119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dibner C, Schibler U, Albrecht U. The mammalian circadian timing system: organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocks. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:517–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton T. Influence of environmental light and melatonin upon mammary tumour induction. Br J Surg. 1969;56:764–766. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800561018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aubert CH, Janiaud P, Lecalvez J. Effect of pinealectomy and melatonin on mammary tumor growth in Sprague–Dawley rats under different conditions of lighting. J Neural Transm. 1980;47:121–130. doi: 10.1007/BF01670163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mhatre MC, Shah PN, Juneja HS. Effect of varying photoperiods on mammary morphology, DNA synthesis, and hormone profile in female rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984;72:1411–1416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haus EL, Smolensky MH. Shift work and cancer risk: potential mechanistic roles of circadian disruption, light at night, and sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen J, Stevens RG. Case-control study of shift-work and breast cancer risk in Danish nurses: impact of shift systems. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1722–1729. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masri S, Kinouchi K, Sassone-Corsi P. Circadian clocks, epigenetics, and cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2015;27:50. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cadenas C, van de Sandt L, Edlund K, Lohr M, Hellwig B, Marchan R, et al. Loss of circadian clock gene expression is associated with tumor progression in breast cancer. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:3282–3291. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.954454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng Z, Luo H, Yang J, Wu W, Chen D, Huang P, et al. Overexpression of the circadian clock gene Bmal1 increases sensitivity to oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1042–1052. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelleher FC, Rao A, Maguire A. Circadian molecular clocks and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;342:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Kang T-H, Reardon JT, Lee JH, Ozturk N. Circadian clock control of the cellular response to DNA damage. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2618–2625. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savvidis C, Koutsilieris M. Circadian rhythm disruption in cancer biology. Mol Med 2012;18:1. http://www.molmed.org/pdfstore/12_077_Savvidis.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Altman BJ, Hsieh AL, Sengupta A, Krishnanaiah SY, Stine ZE, Walton ZE, et al. MYC disrupts the circadian clock and metabolism in cancer cells. Cell Metab. 2015;22:1009–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oda A, Katayose Y, Yabuuchi S, Yamamoto K, Mizuma M, Shirasou S, et al. Clock gene mouse period2 overexpression inhibits growth of human pancreatic cancer cells and has synergistic effect with cisplatin. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:1201–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang L, Yang Z, Zhou J, Tung J-Y, Hsiao C-D, Wang L, et al. Circadian clock gene CRY2 degradation is involved in chemoresistance of colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:1476. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muz B, de la Puente P, Azab F, Azab AK. The role of hypoxia in cancer progression, angiogenesis, metastasis, and resistance to therapy. Hypoxia. 2015;3:83. doi: 10.2147/HP.S93413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu D, Rastinejad F. Structural characterization of mammalian bHLH-PAS transcription factors. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;43:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang N, Chelliah Y, Shan Y, Taylcxgor CA, Yoo S-H, Partch C, et al. Crystal structure of the heterodimeric CLOCK: BMAL1 transcriptional activator complex. Science (80−) 2012;122:2804. doi: 10.1126/science.1222804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erbel PJA, Card PB, Karakuzu O, Bruick RK, Gardner KH. Structural basis for PAS domain heterodimerization in the basic helix-loop-helix-PAS transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:15504–15509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2533374100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egg M, Köblitz L, Hirayama J, Schwerte T, Folterbauer C, Kurz A, et al. Linking oxygen to time: the bidirectional interaction between the hypoxic signaling pathway and the circadian clock. Chronobiol Int. 2013;30:510–529. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2012.754447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Y, Tang D, Liu N, Xiong W, Huang H, Li Y, et al. Reciprocal regulation between the circadian clock and hypoxia signaling at the genome level in mammals. Cell Metab. 2017;25:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KRM, Ozenberger BA, Ellrott K, et al. The cancer genome atlas pan-cancer analysis project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1113. doi: 10.1038/ng.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mermel CH, Schumacher SE, Hill B, Meyerson ML, Beroukhim R, Getz G. GISTIC2. 0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R41. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buffa FM, Harris AL, West CM, Miller CJ. Large meta-analysis of multiple cancers reveals a common, compact and highly prognostic hypoxia metagene. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:428–435. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang WH, Forde D, Lai AG. A novel signature derived from immunoregulatory and hypoxia genes predicts prognosis in liver and five other cancers. J Transl Med. 2019;17:14. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-1775-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabas-Madrid D, Nogales-Cadenas R, Pascual-Montano A. GeneCodis3: a non-redundant and modular enrichment analysis tool for functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W478–W483. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W90–W97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, Duan Q, Wang Z, Meirelles GV, et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang WH, Lai AG. An immunoevasive strategy through clinically-relevant pan-cancer genomic and transcriptomic alterations of JAK-STAT signaling components. bioRxiv. 2019. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2019/03/14/576645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Chang WH, Lai AG. Pan-cancer mutational landscape of the PPAR pathway reveals universal patterns of dysregulated metabolism and interactions with tumor immunity and hypoxia. bioRxiv. 2019. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2019/02/28/563676. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Suvà M-L, Riggi N, Janiszewska M, Radovanovic I, Provero P, Stehle J-C, et al. EZH2 is essential for glioblastoma cancer stem cell maintenance. Cancer Res. 2009;8:5472. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iliopoulos D, Lindahl-Allen M, Polytarchou C, Hirsch HA, Tsichlis PN, Struhl K. Loss of miR-200 inhibition of Suz12 leads to polycomb-mediated repression required for the formation and maintenance of cancer stem cells. Mol Cell. 2010;39:761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiou S-H, Yu C-C, Huang C-Y, Lin S-C, Liu C-J, Tsai T-H, et al. Positive correlations of Oct-4 and Nanog in oral cancer stem-like cells and high-grade oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4085–4095. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bosco G, Ionadi A, Panico S, Faralli F, Gagliardi R, Data P, et al. Effects of hypoxia on the circadian patterns in men. High Alt Med Biol. 2003;4:305–318. doi: 10.1089/152702903769192269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coste O, Beaumont M, Batéjat D, Van Beers P, Touitou Y. Prolonged mild hypoxia modifies human circadian core body temperature and may be associated with sleep disturbances. Chronobiol Int. 2004;21:419–433. doi: 10.1081/CBI-120038611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coste O, Van Beers P, Bogdan A, Charbuy H, Touitou Y. Hypoxic alterations of cortisol circadian rhythm in man after simulation of a long duration flight. Steroids. 2005;70:803–810. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mazzoccoli G, De Cata A, Piepoli A, Vinciguerra M. The circadian clock and the hypoxic response pathway in kidney cancer. Tumor Biol. 2014;35:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen LD. The circadian clock and hypoxia in tumor cell de-differentiation and metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1850:1633–1641. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen S-T, Choo K-B, Hou M-F, Yeh K-T, Kuo S-J, Chang J-G. Deregulated expression of the PER1, PER2 and PER3 genes in breast cancers. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1241–1246. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gery S, Virk RK, Chumakov K, Yu A, Koeffler HP. The clock gene Per2 links the circadian system to the estrogen receptor. Oncogene. 2007;26:7916. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xia H, Niu Z, Ma H, Cao S, Hao S, Liu Z, et al. Deregulated expression of the Per1 and Per2 in human gliomas. Can J Neurol Sci. 2010;37:365–370. doi: 10.1017/S031716710001026X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsu C-M, Lin S-F, Lu C-T, Lin P-M, Yang M-Y. Altered expression of circadian clock genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2012;33:149–155. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gery S, Komatsu N, Kawamata N, Miller CW, Desmond J, Virk RK, et al. Epigenetic silencing of the candidate tumor suppressor gene Per1 in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1399–1404. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mostafaie N, Kállay E, Sauerzapf E, Bonner E, Kriwanek S, Cross HS, et al. Correlated downregulation of estrogen receptor beta and the circadian clock gene Per1 in human colorectal cancer. Mol Carcinog Publ Coop with Univ Texas MD Anderson Cancer Cent. 2009;48:642–647. doi: 10.1002/mc.20510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin YM, Chang JH, Yeh KT, Yang MY, Liu TC, Lin SF, et al. Disturbance of circadian gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2008;47:925–933. doi: 10.1002/mc.20446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang W, Zhao S, Jiang X, Zhang E, Hu G, Hu B, et al. The circadian clock gene Bmal1 acts as a potential anti-oncogene in pancreatic cancer by activating the p53 tumor suppressor pathway. Cancer Lett. 2016;371:314–325. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu L, Kettner NM. The circadian clock in cancer development and therapy. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2013;119:221–282. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396971-2.00009-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiao L, Chang AK, Zang M-X, Bi H, Li S, Wang M, et al. Induction of the CLOCK gene by E2-ERα signaling promotes the proliferation of breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu H, Meng X, Wu J, Pan C, Ying X, Zhou Y, et al. Cryptochrome 1 overexpression correlates with tumor progression and poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu M-L, Yeh K-T, Lin P-M, Hsu C-M, Hsiao H-H, Liu Y-C, et al. Deregulated expression of circadian clock genes in gastric cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li A, Lin X, Tan X, Yin B, Han W, Zhao J, et al. Circadian gene Clock contributes to cell proliferation and migration of glioma and is directly regulated by tumor-suppressive miR-124. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:2455–2460. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Puram RV, Kowalczyk MS, de Boer CG, Schneider RK, Miller PG, McConkey M, et al. Core circadian clock genes regulate leukemia stem cells in AML. Cell. 2016;165:303–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yasuniwa Y, Izumi H, Wang K-Y, Shimajiri S, Sasaguri Y, Kawai K, et al. Circadian disruption accelerates tumor growth and angio/stromagenesis through a Wnt signaling pathway. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin F, Chen Y, Li X, Zhao Q, Tan Z. Over-expression of circadian clock gene Bmal1 affects proliferation and the canonical Wnt pathway in NIH-3T3 cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2013;31:166–172. doi: 10.1002/cbf.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Janich P, Pascual G, Merlos-Suárez A, Batlle E, Ripperger J, Albrecht U, et al. The circadian molecular clock creates epidermal stem cell heterogeneity. Nature. 2011;480:209. doi: 10.1038/nature10649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chilov D, Hofer T, Bauer C, Wenger RH, Gassmann MAX. Hypoxia affects expression of circadian genes PER1 and CLOCK in mouse brain. FASEB J. 2001;15:2613–2622. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0092com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shen C, Kaelin WG., Jr The VHL/HIF axis in clear cell renal carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Okabe T, Kumagai M, Nakajima Y, Shirotake S, Kodaira K, Oyama M, et al. The impact of HIF1α on the Per2 circadian rhythm in renal cancer cell lines. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e109693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hwang-Verslues WW, Chang P-H, Jeng Y-M, Kuo W-H, Chiang P-H, Chang Y-C, et al. Loss of corepressor PER2 under hypoxia up-regulates OCT1-mediated EMT gene expression and enhances tumor malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:12331–12336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222684110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li X-M, Mohammad-Djafari A, Dumitru M, Dulong S, Filipski E, Siffroi-Fernandez S, et al. A circadian clock transcription model for the personalization of cancer chronotherapy. Cancer Res. 2013;73:7176–7188. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roche VP, Mohamad-Djafari A, Innominato PF, Karaboué A, Gorbach A, Lévi FA. Thoracic surface temperature rhythms as circadian biomarkers for cancer chronotherapy. Chronobiol Int. 2014;31:409–420. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2013.864301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dulong S, Ballesta A, Okyar A, Lévi F. Identification of circadian determinants of cancer chronotherapy through in vitro chronopharmacology and mathematical modeling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;149:2154–2164. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chang WH, Lai AG. Pan-cancer genomic amplifications underlie a Wnt hyperactivation phenotype associated with stem cell-like features leading to poor prognosis. bioRxiv. 2019. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2019/01/13/519611. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Chang WH, Forde D, Lai AG. Dual prognostic role for 2-oxoglutarate oxygenases in ten diverse cancer types: implications for cell cycle regulation and cell adhesion maintenance. bioRxiv. 2018. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2018/10/14/442947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Chang WH, Lai AG. Aberrations in Notch-Hedgehog signalling reveal cancer stem cells harbouring conserved oncogenic properties associated with hypoxia and immunoevasion. bioRxiv. 2019. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2019/01/21/526202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Chang WH, Lai AG. Transcriptional landscape of DNA repair genes underpins a pan-cancer prognostic signature associated with cell cycle dysregulation and tumor hypoxia. bioRxiv. 2019. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2019/01/13/519603. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. List of 32 circadian clock genes.

Additional file 2. List of TCGA tumour and non-tumour samples in 21 cancer types.

Additional file 3. Differentially expressed genes between patients separated by ClockLoss or ClockGain into 4th and 1st quartiles.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.