Abstract

Background

Glandular trichomes found in vascular plants are called natural cell factories because they synthesize and store secondary metabolites in glandular cells. To systematically understand the metabolic processes in glandular cells, it is indispensable to analyze cellular proteome dynamics. The conventional proteomics methods based on mass spectrometry have enabled large-scale protein analysis, but require a large number of trichome samples for in-depth analysis and are not suitable for rapid and sensitive quantification of targeted proteins.

Results

Here, we present a high-throughput strategy for quantifying targeted proteins in specific trichome glandular cells, using selected reaction monitoring (SRM) assays. The SRM assay platform, targeting proteins in type VI trichome gland cells of tomato as a model system, demonstrated its effectiveness in quantifying multiple proteins from a limited amount of sample. The large-scale SRM assay uses a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer connected online to a nanoflow liquid chromatograph, which accurately measured the expression levels of 221 targeted proteins contained in the glandular cell sample recovered from 100 glandular trichomes within 120 min. Comparative quantitative proteomics using SRM assays of type VI trichome gland cells between different organs (leaves, green fruits, and calyx) revealed specific organ-enriched proteins.

Conclusions

We present a targeted proteomics approach using the established SRM assays which enables quantification of proteins of interest with minimum sampling effort. The remarkable success of the SRM assay and its simple experimental workflow will increase proteomics research in glandular trichomes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13007-019-0427-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Tomato type VI glandular trichome, Secondary metabolism, Plant defense mechanism, Targeted proteomics, Mass spectrometry, Selected reaction monitoring, Proteotypic peptide, Protein quantification, AQUA peptide, QconCAT

Background

Approximately 30% of vascular plants have epidermal protrusions called trichomes on their aerial parts [1]. Multicellular trichomes that produce and store various secondary metabolites are classified as glandular-type trichomes [2, 3]. Glandular trichomes are commonly composed of the base, stalk, and head units, and are further classified into several subtypes based on their morphology. The glandular trichomes have one or more secretory cells, called trichome glandular cells (TGCs), on the head, and various types of secondary metabolites including terpenoids, flavonoids, and alkaloids are synthesized in TGCs [4–9]. TGCs rapidly secrete intracellular components in response to external physical stimulation, and the secreted components play important roles, such as plant defense against insects and pathogens [10], protection against desiccation [11], and as a barrier against atmospheric oxidative stress [12]. Glandular trichomes are called natural cell factories because of their production of special metabolites, and they have high commercial value as food and pharmaceutical products [13–15].

Several molecular omics studies have been conducted to better understand metabolite production processes in TGCs [16–20]. In particular, mass spectrometry (MS)-based analytical techniques have been used for highly sensitive and high-throughput detection of cellular molecules in TGCs. MS systems combined with separation techniques, e.g., gas chromatography [20, 21] or liquid chromatography (LC) [22], are used extensively to gain insights into the metabolomic profiles of various TGCs. Besides the analysis of cellular metabolomes, the effectiveness of MS has also been demonstrated in large-scale analyses of proteins related to metabolite production in TGCs [23–28]. Current proteomics research is mostly based on an experimental approach using an LC-tandem MS (MS/MS), called shotgun proteomics [29]. Shotgun proteomics is performed by sequencing the peptides derived from the protease digestion of proteins in biological samples, enabling large-scale identification of protein components. However, the complexity of the cellular proteome is high, and it is generally difficult to detect trace components reproducibly using shotgun proteomics. The amount of sample used for single shotgun analysis depends on the capacity of the LC–MS system, but a minimum of 10 μg of total protein as starting material is generally required to identify more than 100 proteins. Therefore, for in-depth proteome analysis, it is necessary to recover a large amount of TGCs, which makes the analysis difficult when the available sample is limited.

In addition to the shotgun approach, which aims to analyze as many proteins as possible, an alternative approach to quantify only the targeted proteins with minimum steps in a sensitive manner is required in TGC proteomics research. In this study, we focused on a novel MS-based proteomics strategy using selected reaction monitoring (SRM), also known as multiple reaction monitoring (MRM), to obtain accurate quantitative information of target proteins from a small amount of TGC sample. SRM has high sensitivity in terms of selectively quantifying target molecules in complex analytical samples [30]. Currently, for protein quantification, the LC-SRM assay using triple quadrupole MS combined with LC is used; with this approach multiple target proteins can be simultaneously detected with a single LC run [31–34]. Quantitative analysis using a large-scale SRM assay covering a group of cellular proteins involved in a specific biological process is now called “targeted” proteomics [35, 36], and its effectiveness has been demonstrated in various model organisms [37–40]. Here, we established an experimental workflow to develop a large-scale SRM assay for monitoring the TGC proteome and implemented targeted proteomics studies. We selected cultivated tomato Solanum lycopersicum, for which high-quality genome sequence information is available [41], and analyzed TGCs for type VI trichomes, which is the most abundant type in tomato [3]. By using an established workflow, comprehensive quantitative information on the targeted proteome can be easily acquired using a small amount of TGC sample. In the present study, we assessed whether established SRM assays could be used for comparative proteomic analysis of TGCs in three different tomato organs. Further, we evaluated whether a combination of established assays and internal standards could be used to quantify the absolute amounts of multiple target proteins in TGCs.

Results

Experimental strategies for SRM assay development

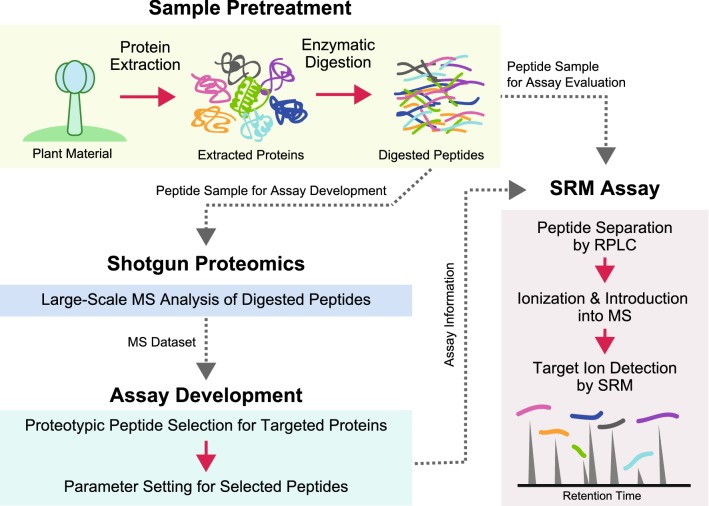

Figure 1 shows the workflow of the SRM assay developed to target TGC proteins. In the SRM assay, the biological samples are fragmented by digestion with a site-specific protease, trypsin or Lys-C, and the derived peptides are used in the SRM assay. The mixture of digested peptides is primarily separated by LC, followed by high selective detection of the peptides derived from the target proteins by quadrupole MS filters based on their mass to charge ratio. Therefore, the selection of target peptides with high ionization efficiency and reproducible detection, called “proteotypic peptides” [42], is indispensable for developing reliable assays. Due to the difficulty of theoretical prediction, it is desirable to select proteotypic peptides based on the datasets from shotgun proteomics analysis. In this study, we first conducted a shotgun proteomics analysis of TGCs by a gel electrophoresis-assisted LC–MS/MS (GeLC–MS/MS) approach [43] and surveyed the peptide candidates suitable for high-throughput SRM. Based on the obtained peptide information, we next established a large-scale SRM assay targeting TGC proteins with proteotypic peptides.

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of the development of selected reaction monitoring (SRM) assays. All mass spectrometry (MS) analyses were conducted using a triple quadrupole/linear ion trap hybrid MS instrument connected with nanoflow reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC). First, the glandular cell samples collected from the target trichome were subjected to a shotgun proteomics analysis. Based on proteomics information, suitable peptides for an SRM experiment were selected and SRM assays targeting selected peptides were designed. The established assay performance was assessed using the rest of the peptide samples used in the shotgun analysis

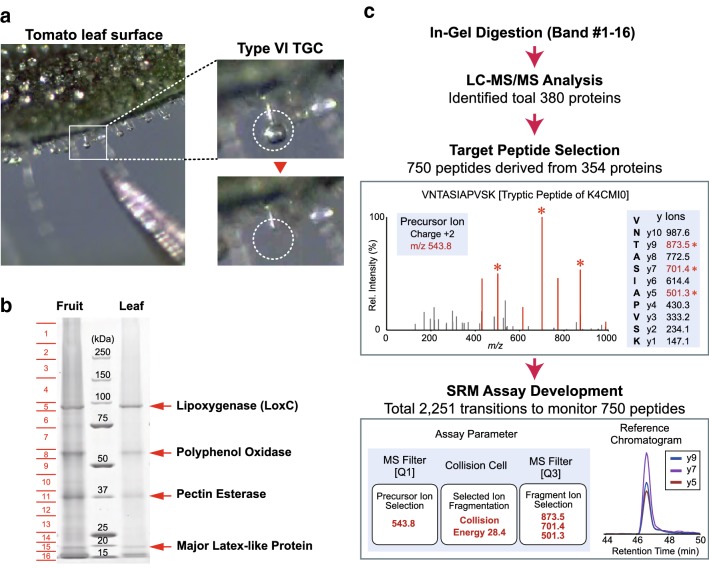

GeLC–MS/MS analysis of TGC proteomes

Shotgun proteomics analysis was performed using glandular cells from type VI trichomes of tomato collected from different organs (the fruits and leaves). TGCs were collected manually under a stereo microscope using a pair of forceps (Fig. 2a). TGCs were stably placed at the tip of the forceps, enabling easy recovery of cellular components by immersing the tip rapidly in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) lysis buffer. The amount of protein contained in glandular cells/trichomes was different among the organs; for example, 2.3 ng in the leaf and 6.1 ng in the green fruit (Additional file 1: Figure S1). In the GeLC–MS/MS analysis, the sample amount required for fractionation by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was approximately 5 μg, which was obtained by TGC sampling from 800 glandular trichomes. The extracted TGC proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 2b). The SDS-PAGE gel image showed four major protein bands in the sample lane; the band at ~ 90 kDa was lipoxygenase (LoxC), known as a type VI TGC-specific protein [23]. The sample lane was divided into 16 pieces and in-gel protein digestion using trypsin was carried out with each gel piece. Half of the digested peptides were subjected to LC–MS/MS with data-dependent acquisition. As a result of a database search with the MS/MS data obtained, 380 proteins were identified from fruit TGCs (Additional file 2: Table S1). A total of 168 proteins were identified to be involved in cellular metabolic processes (GO: 0008152 and GO: 0044237) (Additional file 3: Figure S2). Many proteins (34) involved in response to stimulation (GO: 0050896) were also observed, as expected from the physiological function of the glandular trichomes.

Fig. 2.

Development of a large-scale selected reaction monitoring (SRM) system targeting the tomato trichome gland cell (TGC) proteome. a Images of the TGC sampling procedure. The target TGCs from the head of type VI trichomes of tomato were manually recovered with a pair of fine forceps under a stereoscopic microscope. b Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) of the TGC proteins. After sampling TGCs from 800 trichomes, cellular protein components were extracted. Protein extracts were separated using a 4–12% NuPAGE gel and protein bands were visualized with Bio-safe CBB. c Experimental workflow of the SRM assay development. Proteins separated by PAGE were digested in the gel; the resulting peptide digests were analyzed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) and their sequences were identified by a database search. Based on the obtained MS information, the combination of a precursor ion and the fragment ions (SRM transition) was selected. Finally, for monitoring 750 peptides, 2 251 transitions were chosen in this study

Assay development for the targeted proteins

Among the identified peptides from shotgun proteomics, we selected 750 peptides derived from 354 proteins as the target candidates for the SRM assays (Fig. 2c). In the MS/MS analysis, many digested peptides were generally observed from high-abundance proteins. On the contrary, only 1–3 peptides were observed from low-abundance proteins. Therefore, the number of peptides that can be monitored by SRM varies depending on the protein. In this study, up to five peptides per protein were selected as candidates. Peptides containing methionine residues are known to be unsuitable for quantitative analysis due to their oxidative modification. Therefore, peptide sequences containing methionine were excluded as much as possible. We then developed the SRM assays targeting peptide candidates. In the SRM assay, the combination of a precursor ion and the fragment ions, called SRM transition, enables the detection of targets with high specificity (Fig. 2c). In this study, we used Skyline software [44] to design 2251 transitions to monitor 750 peptides based on the MS/MS spectral information, and a large-scale SRM assay was developed using a triple quadrupole MS system connected online to a nanoflow LC. At least three transitions were set for monitoring the targeted peptide ion in the SRM assay. The workability of the established assays was verified using the remaining half of the in-gel digested peptide sample. Among the transitions designed in this study, 1587 transitions targeting 298 proteins (Additional file 4: Table S2) had peptide ion peaks with sufficient strength to be successfully detected.

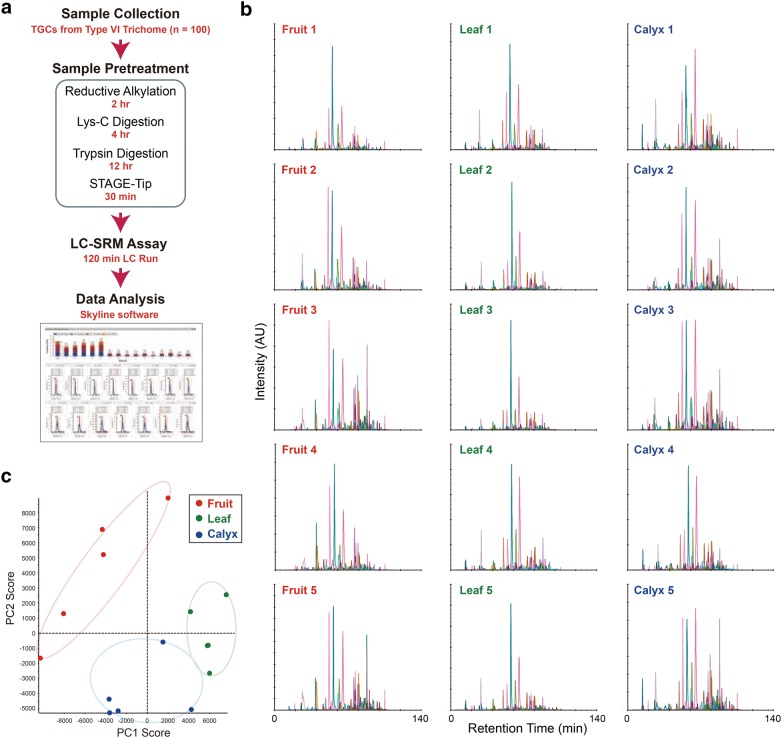

Targeted TGC proteomics using SRM

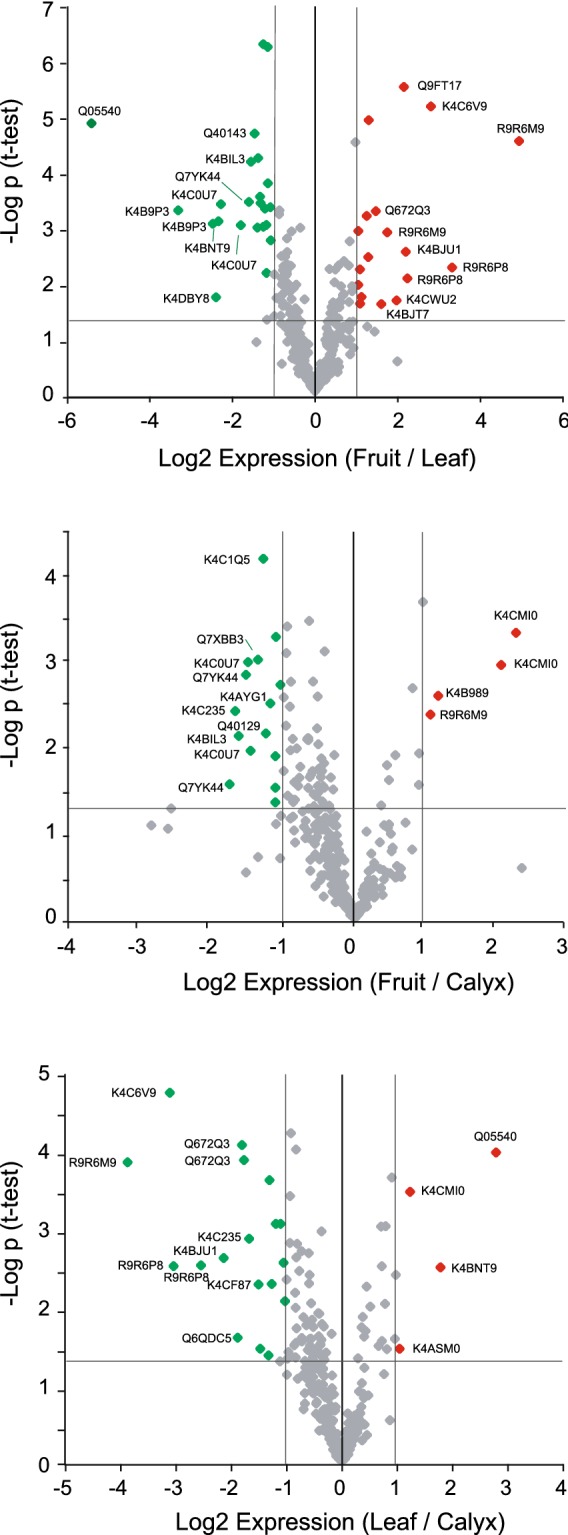

In general, nanoflow LC-SRM can detect targeted proteins with high sensitivity from a smaller amount of sample than that used for LC–MS/MS analysis, which reduces the sample amount used for a single experiment. However, conventional sample preparation for shotgun proteomics using LC–MS/MS (assuming hundreds of micrograms) has a risk of sample loss and is not suitable for small sample volumes. Therefore, in this study we developed a sample pretreatment method suitable for trace amounts of TGCs. The experimental workflow for our sample pretreatment is shown in Fig. 3a. TGCs recovered using a pair of forceps were directly collected in 8 M urea solution and the protein sample extracted by sonication was subjected to protease digestion with trypsin and Lys-C. To reduce sample loss, all processes were completed in a single low-adsorption tube. To evaluate the established method, sample pretreatment for SRM was performed using TGCs that were recovered from green tomato fruits. We were able to recover ~ 400 TGCs from 100 trichomes in 5–10 min, and the recovery of TGC samples necessary for all experiments with five replicates was completed within 60 min. We performed the SRM assay using half of the obtained peptide samples and succeeded in detecting 221 proteins within a 120-min LC run (Fig. 3b). Using the established system, we further performed a comparative quantitative analysis of targeted proteome levels in TGCs derived from different organs (the leaves, green fruits, and calyx) of tomato (Fig. 3b and Additional file 5: Table S3). Each biological replicate contained TGCs collected from 100 trichomes. Principal component analysis (PCA) using the quantitative data obtained revealed organ-specific differences in TGC proteomes (Fig. 3c). Statistical analysis showed that proteins related to plant defense mechanisms, secondary metabolic processes, and anti-oxidative stress response are differentially expressed (Fig. 4 and Additional file 6: Table S4).

Fig. 3.

Targeted tomato trichome gland cell (TGC) proteomics by large-scale selected reaction monitoring (SRM) quantification. a Experimental workflow of tomato TGC proteomics using SRM. TGCs of type VI trichomes from tomato were recovered from different organs (the green fruits, leaves, and calyx). TGCs were collected directly into urea lysis buffer, and then subjected to an in-solution digestion treatment with trypsin/Lys-C. The peptide ions of interest were selectively monitored by the liquid chromatography (LC)-SRM assay and the peak intensities of the detected ions of the different organs were compared using Skyline software. b SRM profiles of the targeted TGC proteome in the different organs. Five biological replicates were used for each organ type. In our SRM system, 221 proteins were quantified. c Principal component analysis was performed based on the peak intensity of the peptides identified in the five replicates

Fig. 4.

Volcano plots representing tomato trichome gland cell (TGC) protein expression profiles in three different organs of tomato. In the relative quantification with label-free selected reaction monitoring (SRM) assays, 331 peptides representing 221 proteins were quantified and used for t-tests to generate the volcano plot indicating the log2 expression ratio on the X-axis and − log p value on the Y-axis for each peptide. Detailed information of organ-enriched proteins is shown in Additional file 6: Table S4

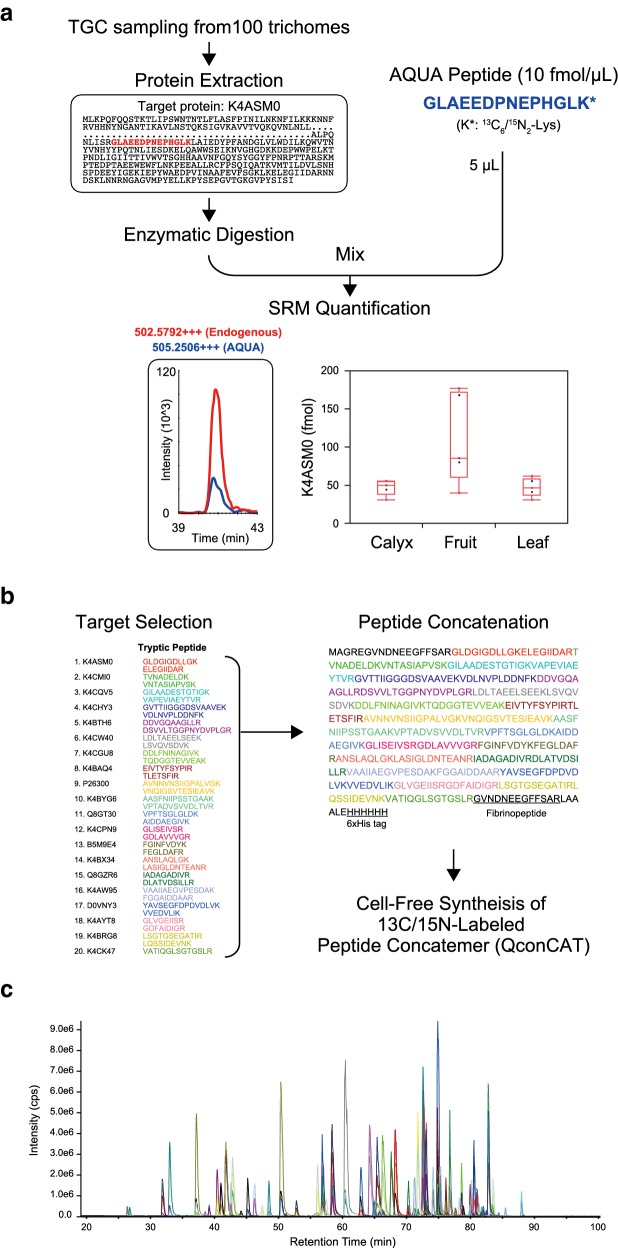

Quantitative strategies using stable-isotope dilution MS

Combining established assays with stable isotope-labeled peptides of known concentration (AQUA peptides [45]) as an internal standard enables the measurement of the absolute amounts of target proteins (Fig. 5a). In this study, the absolute amount of major TGC protein components (K4ASM0, K4CMI0, K4D062, and K4BNH6) was analyzed using the AQUA peptide labeled with 13C/15N at the C-terminal lysine residue. Based on the heavy (internal standard) and light (endogenous) peak area ratio in the SRM chromatograph, the absolute amounts of the target proteins were calculated. The estimated amounts of target TGC proteins contained in 100 trichomes, assuming that all four TGCs in the tomato trichome head were recovered without loss, are shown in Additional file 7: Figure S3.

Fig. 5.

Selected reaction monitoring (SRM)-based quantitative strategies of targeted protein amount in tomato trichome gland cells (TGCs). a SRM determination of target protein abundance in the TGC sample using an AQUA peptide standard. A stable isotope-labeled AQUA peptide (GLAEEDPNEPHGLK) was used as an internal standard for the absolute quantification of the targeted K4ASM0 protein by SRM. b Biosynthesis workflow for the QconCAT peptide standards. Two QconCAT sequences covering 50 proteins involved in the synthesis of secondary metabolites (detailed information can be found in Additional file 8: Figure S4 and Additional file 9: Table S5) were designed in this study. Stable isotope-labeled QconCATs were synthesized using a wheat germ cell-free synthesis system. c SRM chromatogram of standard peptides (total 79 peptides) obtained by biosynthesis of stable isotope-labeled QconCATs. The synthesized QconCATs were purified with 6xHis-tag and digested with trypsin. The peptide mixtures derived from QconCATs were subjected to liquid chromatography (LC)-SRM. Fibrinopeptide released from the C terminus of QconCATs due to trypsin digestion was used for the absolute quantification of the synthesized QconCATs using SRM (Additional file 8: Figure S4C)

When there are many target proteins to be quantified, a quantitative strategy using a concatemer of standard peptides called QconCAT can be effective [46–48]. In particular, the QconCAT series that covers a group of target proteins categorized based on their biological functions will be useful for functional proteomic analyses. In this study, we synthesized QconCATs covering 50 TGC proteins, involved in the synthesis of secondary metabolites and observed in our proteomics analysis (Fig. 5b and Additional file 8: Figure S4). Only two types of QconCAT (SOL-01 and SOL-02) with a molecular weight of ~ 50 kDa were sufficient to cover all the peptides (Additional file 9: Table S5). The LC-SRM analysis using tryptic digests of the synthesized 13C/15N-labeled QconCATs revealed that 79 kinds of standard peptides covering all 50 target proteins were successfully synthesized (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

MS-based proteomics using the shotgun technique has been used to successfully identify various TGC proteins in several plant species [49]. However, the complexity of the TGC proteome is high, and the detection of low-abundance components requires a large number of samples and complicated fractionated processing. In addition, the amount of data obtained by the analysis is enormous and is time-consuming to analyze. Therefore, a new analytical technique is required for quick and highly-sensitive quantitation of the protein component of interest in TGC samples. Herein, we proposed an experimental strategy for high-throughput acquisition of quantitative information on target TGC proteins using the high-sensitivity SRM assay.

The information of proteotypic peptides suitable for monitoring targeted proteins is essential for SRM assay development. In the human proteome, the peptides for several proteins have already been identified and their optimized SRM assay information is publicly available [50–52]. On the contrary, publicly available SRM information for plant proteomes is currently being developed rapidly [53], but its scale has so far been limited. In this study, we conducted a search for proteotypic peptides in the tomato TGC proteome using GeLC–MS/MS analysis. The combination of PAGE separation at the protein level and reversed-phase LC separation at the peptide level was effective for collecting a large amount of peptide information from complex TGC protein extracts. Using the TGC samples obtained from 800 trichomes, reliable SRM assay construction for detecting more than 300 major TGC proteins was possible in approximately 2 weeks. Although the established assay can cover high-abundance proteins in tomato TGCs, comprehensive quantification of the TGC proteome requires peptide information on low-abundance proteins. We used a triple quadrupole/linear ion trap hybrid MS system for GeLC–MS/MS analysis, but the use of a high-end MS instrument with faster scan-speed such as quadrupole time-of-flight MS [54] will improve the number of peptides detected. Sample pre-fractionation by introducing an additional separation technique such as isoelectric focusing electrophoresis will also be effective.

For type VI gland trichomes of tomato with four TGCs in the head, manual sampling using a pair of forceps was suitable for TGC sampling. Collection of TGCs after visual confirmation avoids sample contamination, which is a problem in the conventional large-scale recovery method of scraping and mesh-filtering [16]. In addition, our method can accurately count the number of harvested cells, which is useful to estimate the accurate protein expression level per cell. On the contrary, while sampling TGCs of small size, e.g., type I trichome of tomato, it may be effective to choose other approaches that are easier to operate than the use of forceps, such as absorbing cellular components on filter paper and aspirating with a capillary. For single cell metabolome analysis of tomato trichome, an example of recovering intracellular components using a pressure probe made of quartz capillary has been reported [55], and the application of such a method to TGC proteomics would also be interesting. The TGC sample (derived from 800 trichomes) recovered for GeLC–MS/MS is rich in essential oils, and it is preferable to purify protein components by methanol/chloroform precipitation [56]. Contrarily, a trace amount of TGC sample (derived from 50 to 100 glandular trichomes) prepared for the assay is readily solubilized by sonication in 50 μL of high concentration urea solution, and the oil in the sample had no influence on subsequent protease digestion treatment and peptide purification.

Protein quantification by the SRM assay has excellent detection sensitivity and wide dynamic range, which is suitable for simultaneously monitoring multiple targets from small biological samples in a single run. For example, the detection of the major TGC proteins by our established SRM assays was possible in 1/10th the amount of sample used for GeLC–MS/MS. The high detection sensitivity of SRM greatly contributes to the reduction in the amount of TGC used for analysis, allowing minimally invasive TGC sampling. For the measurement of 221 proteins, ~ 400 TGCs (derived from 100 glandular trichomes) recovered from a single tomato plant using a pair of forceps were sufficient, and the throughput performance of the analysis was greatly improved. Establishment of this SRM assay platform with high sensitivity and high throughput enables a reliable quantitative analysis of the TGC proteome using multiple samples.

Our SRM assays targeting 200 major proteins revealed that the proteomic profile of TGCs has significant differences at the organ level. For example, some proteins related to defense response to insects and pathogens (Q05540, K4B9P3, and Q7XBB3), cold and drought stress (K4BVU7), and reactive oxygen species (Q7YK44) were abundantly expressed in the leaves and/or calyx compared with those in the green fruits. Detailed spatiotemporal analysis of their expression levels in various environmental conditions is necessary to further understand their physiological role in each organ. To this end, multipoint monitoring of targeted proteins utilizing our high-throughput SRM-based approach will greatly contribute to speeding up and simplifying this analysis. Moreover, organ specificity was also observed in nine enzymes involved in secondary metabolite production (K4AS92, K4ASM0, K4C235, K4C6Q9, K4CJ96, K4CMI0, K4CW40, K4CYV4, and Q8GT30), which suggests the presence of inter-organ differences at the secondary metabolite level in TGCs. The development of a trans-omics workflow, which analyzes the metabolites contained in the TGC sample used for protein quantification simultaneously, is important for further understanding of the intracellular metabolic production process.

In MS-based protein quantification, stable isotope-labeled peptide standards are generally required to accurately know the absolute amount of the target proteins in a crude biological sample [57]. Our study demonstrated that the combination of SRM and AQUA peptides is a powerful approach for determining the absolute abundance of protein components in TGCs. However, one of the barriers in the use of this approach for targeted proteomics is the high cost involved in the preparation of AQUA peptides. To overcome this problem, the QconCAT strategy can be a powerful alternative for the cost-effective generation of reference peptides [58, 59]. In this study, we demonstrated that two stable isotope-labeled QconCAT proteins could produce 79 standard peptides, permitting the quantification of 50 proteins. Using a similar approach, the development of standard libraries for global quantification of all proteins identified in this study can be achieved by creating 6–8 QconCATs. Further expansion of QconCAT resources will greatly contribute to the realization of global proteome quantification in TGCs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a large-scale LC-SRM assay enabled high-throughput analysis of multiple target proteins contained in TGCs, which will be a useful tool for the high-throughput quantification of proteome dynamics in biological processes. Although the experimental workflow for assay development in this study targeted the TGC proteome, a similar approach would be applicable for targeted proteome analysis in other micro-tissues of a plant. Our assay information can be accessed via a public repository server PanoramaWeb [60] (https://panoramaweb.org/tomatotgc.url), which has been developed to support the sharing of SRM assay information and measurement data. Additional sequence information, including sequence homology of the targeted peptides in other plant species (Additional file 10: Figure S5), for assay development is available from our online reference database Ehime University SRM/MRM Reference Database (ESRDB) [58] (http://esrdb.m.ehime-u.ac.jp/index.html).

Methods

Reagents

Acetonitrile, acrylamide, ammonium bicarbonate (ABC), chloroform, methanol, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), formic acid (FA), acetic acid, pure water, and sequencing grade Lys-C were obtained from Wako (Osaka, Japan). Urea was purchased from GE Healthcare (Pittsburg, PA, USA). Sequencing grade trypsin was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Dithiothreitol (DTT) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Stable isotope-labeled AQUA peptides (99% purity) as an internal standard for protein quantification were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Artificially synthesized QconCAT genes were obtained from Eurofins Genomics (Tokyo, Japan).

Plant material

The tomato cultivar, Micro-Tom (S. lycopersicum L. ‘Micro-Tom’), was used in the study. All the plants were grown on a growing medium consisting of peat moss (Sakata Seed Corp., Kanagawa, Japan) and incubated in a growth chamber (MLR-352H, Panasonic Corp., Osaka, Japan) maintained at air temperature, relative humidity, photosynthetic photon flux density, and photoperiod of 28 °C, 60%, 100 μmol/m2/s, and 16 h, respectively. Sufficient water and nutrient solutions were supplied periodically as described previously [55]. Trichome glandular cells of type VI glandular trichomes on the leaves, unripe green fruits, and calyx of approximately 8–12-week-old plants were collected with five biological replications and used in the subsequent analyses.

Gel electrophoresis

Tomato TGCs were manually harvested using a pair of forceps from type VI glandular trichomes of tomato (n = 800) under a stereoscopic microscope and were collected in 50 μL SDS lysis buffer (4% [w/v] SDS in 150 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.8). After homogenization using a BioMasher disposable homogenizer tube (Nippi, Tokyo, Japan), the extracted proteins were purified by methanol/chloroform precipitation. The precipitated proteins were solubilized in 10 μL of NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 200 mM DTT and subjected to electrophoretic separation using a NuPAGE 4–12% Bis–Tris gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in NuPAGE MOPS SDS running buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The separated proteins were stained with BioSafe Coomassie brilliant blue (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) and the stained gel images were captured using a GELSCAN transmission scanner (iMeasure Inc., Nagano, Japan).

In-gel protein digestion

A CBB-stained sample lane in the NuPAGE gel was divided into 16 pieces, and the cut gel pieces were used for in-gel trypsin digestion. Each gel piece was incubated with 100 μL of 50% (v/v) acetonitrile/50-mM ABC at 23 °C for 3 h to remove the CBB dye. The de-stained gel was incubated with 50 μL of 100 mM ABC/4 mM DTT at 37 °C for 1.5 h, and then incubated with 50 μL of 100 mM ABC/25 mM acrylamide at 23 °C for 30 min. The gel was washed with 500 μL of washing solution A (50% [v/v] methanol, 5% [v/v] acetic acid) for 1 h and further washed with 500 μL of washing solution B (50 mM ABC, 50% [v/v] acetonitrile). After washing, the gel was dehydrated with 200 μL of acetonitrile for 15 min, and then air-dried for 15 min. For in-gel protein digestion, 1 μL of trypsin solution (0.1 μg/μL) was added to the dry gel and incubated with 50 μL of 100 mM ABC at 37 °C for 16 h. The digested peptides in the gel were extracted by shaking it with 50 μL of 5% (v/v) TFA/50% (v/v) acetonitrile for 10 min. The extracted peptides were dried by vacuum centrifugation and resuspended in 10 μL of 0.1% TFA for the LC–MS/MS analysis.

LC–MS/MS analysis

For the LC–MS/MS analysis of in-gel digested peptides, a system consisting of an Eksigent nanoLC system (SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA) connected online to a Q-Trap 5500 hybrid triple quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer (SCIEX) was used. The peptide solution (5 μL) was injected into an Eksigent 200 µm i.d. × 0.5 mm cHiPLC trap column (SCIEX). The trapped peptides were then separated on a 75-µm i.d. × 15 cm C18 reversed phase cHiPLC column (SCIEX). For LC gradient separation, the mobile phase consisted of an aqueous solution of 0.1% FA as solvent A and 80% acetonitrile containing 0.1% FA and water as solvent B. The flow rate was 300 μL/min. The following gradient was used: 0–60 min, 2–18% B; 60–95 min, 18–40% B; hold at 90% B for 10 min, and equilibrate at 2% B for 15 min prior to the next run. The column temperature was maintained constant at 45 °C. The MS/MS data of the eluted peptides were acquired in the positive ion mode by information-dependent acquisition workflow as described previously [58]. The MS/MS data were processed using ProteinPilot V4.0 (SCIEX) search engine for protein identification. Peptide identification was performed against entries from the UniProt Solanum lycopersicum reference proteome (Organism ID: 4081; download date: Jun 1, 2013) using the following parameters: cys alkylation, acrylamide; digestion, trypsin; processing parameters, biological modification; search effort, through ID. Protein identities were accepted using a 1% false discovery rate.

In-solution protein digestion

Manually harvested TGCs from tomato glandular trichomes (n = 100) were placed in 50 μL of urea lysis solution (8 M urea in 50 mM ABC) in a 0.5-mL low-adsorption tube (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and were subjected to sonication in an ultrasonic bath at 20 °C for 30 s. The sample tube was immediately transferred to a deep freezer and stored at − 80 °C until in-solution digestion. After being mixed with 2 μL of 200 mM DTT, the sample solution was incubated at 37 °C for 1.5 h, followed by alkylation with 2 μL of 1.2 M acrylamide for 30 min at 23 °C. The proteins in the solution were digested with 0.2 μg of Lys-C for 4 h at 23 °C. After diluting the solution with 200 μL of 100 mM ABC, further digestion was carried out with 0.2 μg of trypsin for 12 h at 37 °C. The digested peptides were purified using a self-made SDB-XC STAGE tip. The obtained peptides were dried using vacuum centrifugation, resuspended in 10 μL of 0.1% (v/v) TFA, and subjected to LC-SRM analysis. For each run, 5 μL of sample was injected.

LC-SRM assay

The development of the SRM assays with Skyline software was performed as described previously [58]. The database search files from ProteinPilot software (SCIEX) were used to construct the MS spectral library containing only tryptic digested peptides (allowed one missed cleavage) with a confidence value of > 0.9. Up to five peptides of length 6–30 amino acids were selected per protein for the SRM analysis. SRM transitions were selected from the 3 to 4 most intense y and b product ions among + 2 or + 3 charged precursors of each peptide. The LC-SRM assay was performed using the same LC–MS system (SCIEX QT5500) used for the GeLC–MS/MS analysis. Analysis of the obtained SRM data was performed with Skyline. Endogenous peptide peaks in the acquired SRM chromatogram were selected manually based on the chromatographic elution pattern and dot product (dotp) value.

Protein quantification using the AQUA peptide

Tomato TGCs derived from 100 type VI trichomes were digested in the urea lysis solution, as described above, and the obtained digests were mixed with 5 μL of AQUA peptide solution (10 fmol/μL). After purification of the peptide sample with a STAGE tip, the target peptides in the sample were detected by SRM. The absolute amount of the target endogenous protein was estimated by comparing the light and heavy peak areas of the selected monitoring peptide.

Cell-free synthesis of heavy-labeled QconCATs

Wheat germ cell-free synthesis of QconCAT proteins was performed using the WEPRO8240H expression kit (Cell-Free Sciences, Matsuyama, Japan) as described previously [59]. In vitro translation of the QconCAT proteins labeled with L-Arg-13C6,15N4, L-Lys-13C6, and 15N2 was performed in a bilayer system (200 μL of substrate layer and 40 μL of translation layer) at 17 °C for 20 h. The synthesized QconCAT proteins were purified using Ni-Sepharose High-Performance resin (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Statistical analysis

The PCA and t-tests were performed using MarkerView software ver. 1.2.1 (SCIEX).

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Protein assay of trichome glandular cell (TGC) samples derived from a type VI trichome of tomato. (A) Experimental workflow. The total amount of protein extracted from the TGC sample was analyzed using the Qubit protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. (B) The estimated amount of the total TGC protein derived from a single trichome from different organs (the fruits, leaves, and calyx). Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Tomato trichome glandular cell (TGC) proteins identified by gel electrophoresis-assisted liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (GeLC–MS/MS) analysis. TGC proteins were identified using ProteinPilot (SCIEX) software with a false discovery rate (FDR) of 1%. Accession: accession ID in UniProtKB database; Protein Name: name of identified protein; Identified Peptide #: number of tryptic peptide identified by MS/MS, the cut-off for peptide confidence scores was > 95; % Sequence Coverage: the percentage of the protein sequence covered by identified peptides with confidence score > 95.

Additional file 3: Figure S2. Shotgun proteomics of tomato trichome glandular cells (TGCs) using gel electrophoresis-assisted liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (GeLC–MS/MS). (A) Biological processes of the TGC proteins identified by GeLC–MS/MS. Gene ontology analysis using PANTHER 14.0 (http://pantherdb.org) was performed on the proteins identified at FDR 1%. (B) Metabolic pathways related to the proteins identified by shotgun proteomics are highlighted in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway map (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html).

Additional file 4: Table S2. Established selected reaction monitoring (SRM) assays targeting tomato trichome glandular cell (TGC) proteome. The SRM assay was developed using Skyline Software. Q1: quadrupole mass filter to select a precursor ion; Q3: quadrupole mass filter to select a fragment ion; Protein: protein targeted by the assay; Sequence: monitoring peptide sequence; Charge: charge of precursor ion selected by Q1; Fragment ion: fragment ion selected by Q3; DP: declustering potential; CE: collision energy; Verified: SRM transition which was verified using tryptic digest of tomato TGC extract.

Additional file 5: Table S3. Relative expression levels of targeted proteins in tomato trichome glandular cells (TGCs). The relative expression levels of target protein in each sample type (fruit, leaf, and calyx) was estimated based on the selected reaction monitoring (SRM) peak area of the corresponding peptide. Protein: targetedprotein name; Peptide: peptide sequence used for selected reaction monitoring (SRM) quantitative analysis.

Additional file 6: Table S4. Differential expression of trichome glandular cell (TGC) proteins between tomato organs. Fold Change: fold change for differential protein expression; p value: statistical significance; Accession: accession IDs of proteins with differential expression between different organs; Protein: targeted protein name; Peptide: peptide sequence used for selected reaction monitoring (SRM) quantitative analysis; GO - Molecular function: gene ontology annotation for molecular function; GO - Biological process: gene ontology annotation for biological process.

Additional file 7: Figure S3. Absolute quantification of targeted proteins in tomato trichome glandular cells (TGCs) using AQUA peptide. Tryptic peptides shown on the graphs were used for selected reaction monitoring (SRM) quantification.

Additional file 8: Figure S4. High-throughput generation of standard peptides for selected reaction monitoring (SRM) quantification using QconCAT strategy. (A) Experimental workflow of QconCAT biosynthesis using a wheat germ cell-free system. (B) Representative polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) images of synthesized QconCATs. For gel electrophoresis, 4%–12% NuPAGE gel was used. Separated QconCATs were visualized with CBB-R250. (C) Absolute quantification of the synthesized QconCATs. (D) SRM chromatograms of QconCATs. Tryptic digests from stable-isotope-labeled QconCATs (SOL-01 and SOL-02) were individually analyzed by liquid chromatography (LC)-SRM.

Additional file 9: Table S5. QconCAT information. Sequence: amino acid sequence of designed QconCAT; Molecular Weight: theoretical molecular weight of QconCAT; Synthesized Gene Sequence: nucleic acid sequence of artificial synthetic gene encoding QconCAT; Accession: accession ID of protein to be quantified by QconCAT; Peptide: peptide sequence used for QconCAT design; KEGG Information: information on enzymatic function from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (sly01110 Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites - Solanum lycopersicum).

Additional file 10: Figure S5. Ehime University selected reaction monitoring (SRM)/multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) reference database (ESRDB): online reference database for assays. Detailed sequence information including sequence homology of target peptides in Solanum lycopersicum and other plant species (Arabidopsis thaliana, Nicotiana tabacum, and Artemisia annua) is available.

Authors’ contributions

AT, HN, and NT designed the study. AT and NT performed most of the experiments. TN and KN provided tomato plants for TGC sampling. HO contributed to the comparative analysis of TGC profiles in different tomato organs. YT helped with QconCAT synthesis. AT and NT analyzed the data. AT and NT wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The tomato resource used in this research was provided by the National BioResource Project (NBRP), MEXT, Japan. We thank Prof Seiichi Fukai (Kagawa University) for helpful discussion. We thank Ayuko Tachibana (Dynacom) and Vagisha Sharma (University of Washington) for their excellent technical assistance.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The SRM data files (ProteomeXchange Id: PXD012250) have been deposited at PanoramaWeb (https://panoramaweb.org/tomatotgc.url).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grants (16K08937 and 18H04559 to NT). The study was also supported by grants from Ehime University (to NT and HN).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- TGC

trichome glandular cell

- MS

mass spectrometry

- SRM

selected reaction monitoring

- LC

liquid chromatography

- MS/MS

tandem MS

- GeLC–MS/MS

gel electrophoresis-assisted LC–MS/MS

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- ABC

ammonium bicarbonate

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- FA

formic acid

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

References

- 1.Fahn A. Structure and function of secretory cells. In: Hallahan DL, Gray JC, editors. Plant trichomes. New York: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 37–75. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fahn A. Secretory tissues in vascular plants. New Phytol. 1988;108:229–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1988.tb04159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergau N, Bennewitz S, Syrowatka F, Hause G, Tissier A. The development of type VI glandular trichomes in the cultivated tomato Solanum lycopersicum and a related wild species S. habrochaites. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:289. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0678-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner GJ. Secreting glandular trichomes: more than just hairs. Plant Physiol. 1991;96(3):675–679. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.3.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gershenzon J, McCaskill D, Rajaonarivony JI, Mihaliak C, Karp F, Croteau R. Isolation of secretory cells from plant glandular trichomes and their use in biosynthetic studies of monoterpenes and other gland products. Anal Biochem. 1992;200(1):130–138. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90288-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schilmiller AL, Last RL, Pichersky E. Harnessing plant trichome biochemistry for the production of useful compounds. Plant J. 2008;54(4):702–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lange BM, Turner GW. Terpenoid biosynthesis in trichomes—current status and future opportunities. Plant Biotechnol J. 2013;11(1):2–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2012.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giuliani C, Ascrizzi R, Tani C, Bottoni M, Maleci Bini L, Flamini G, et al. Salvia uliginosa Benth.: glandular trichomes as bio-factories of volatiles and essential oil. Flora. 2017;233:2–21. doi: 10.1016/j.flora.2017.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glas JJ, Schimmel BC, Alba JM, Escobar-Bravo R, Schuurink RC, Kant MR. Plant glandular trichomes as targets for breeding or engineering of resistance to herbivores. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(12):17077–17103. doi: 10.3390/ijms131217077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang JH, Liu G, Shi F, Jones AD, Beaudry RM, Howe GA. The tomato odorless-2 mutant is defective in trichome-based production of diverse specialized metabolites and broad-spectrum resistance to insect herbivores. Plant Physiol. 2010;154(1):262–272. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.160192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paiva EAS, Martins LC. Calycinal trichomes in Ipomoea cairica (Convolvulaceae): ontogenesis, structure and functional aspects. Aust J Bot. 2011;59:91–98. doi: 10.1071/BT10194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Tosens T, Harley PC, Jiang Y, Kanagendran A, Grosberg M, et al. Glandular trichomes as a barrier against atmospheric oxidative stress: relationships with ozone uptake, leaf damage, and emission of LOX products across a diverse set of species. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41(6):1263–1277. doi: 10.1111/pce.13128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner GJ, Wang E, Shepherd RW. New approaches for studying and exploiting an old protuberance, the plant trichome. Ann Bot. 2004;93(1):3–11. doi: 10.1093/aob/mch011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tissier A. Glandular trichomes: what comes after expressed sequence tags? Plant J. 2012;70(1):51–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huchelmann A, Boutry M, Hachez C. Plant glandular trichomes: natural cell factories of high biotechnological interest. Plant Physiol. 2017;175(1):6–22. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.00727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gang DR, Wang J, Dudareva N, Nam KH, Simon JE, Lewinsohn E, et al. An investigation of the storage and biosynthesis of phenylpropenes in sweet basil. Plant Physiol. 2001;125(2):539–555. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai X, Wang G, Yang DS, Tang Y, Broun P, Marks MD, et al. TrichOME: a comparative omics database for plant trichomes. Plant Physiol. 2010;152(1):44–54. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.145813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balcke GU, Bennewitz S, Zabel S, Tissier A. Isoprenoid and metabolite profiling of plant trichomes. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1153:189–202. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0606-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosh B, Westbrook TC, Jones AD. Comparative structural profiling of trichome specialized metabolites in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and S. habrochaites: acylsugar profiles revealed by UHPLC/MS and NMR. Metabolomics. 2014;10(3):496–507. doi: 10.1007/s11306-013-0585-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fridman E, Wang J, Iijima Y, Froehlich JE, Gang DR, Ohlrogge J, et al. Metabolic, genomic, and biochemical analyses of glandular trichomes from the wild tomato species Lycopersicon hirsutum identify a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of methylketones. Plant Cell. 2005;17(4):1252–1267. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.029736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie Z, Kapteyn J, Gang DR. A systems biology investigation of the MEP/terpenoid and shikimate/phenylpropanoid pathways points to multiple levels of metabolic control in sweet basil glandular trichomes. Plant J. 2008;54(3):349–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schilmiller A, Shi F, Kim J, Charbonneau AL, Holmes D, Daniel Jones A, et al. Mass spectrometry screening reveals widespread diversity in trichome specialized metabolites of tomato chromosomal substitution lines. Plant J. 2010;62(3):391–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schilmiller AL, Miner DP, Larson M, McDowell E, Gang DR, Wilkerson C, et al. Studies of a biochemical factory: tomato trichome deep expressed sequence tag sequencing and proteomics. Plant Physiol. 2010;153(3):1212–1223. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.157214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu T, Wang Y, Guo D. Investigation of glandular trichome proteins in Artemisia annua L. using comparative proteomics. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e41822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Champagne A, Boutry M. Proteomic snapshot of spearmint (Mentha spicata L.) leaf trichomes: a genuine terpenoid factory. Proteomics. 2013;13(22):3327–3332. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201300280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sallets A, Beyaert M, Boutry M, Champagne A. Comparative proteomics of short and tall glandular trichomes of Nicotiana tabacum reveals differential metabolic activities. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(7):3386–3396. doi: 10.1021/pr5002548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Champagne A, Boutry M. A comprehensive proteome map of glandular trichomes of hop (Humulus lupulus L.) female cones: identification of biosynthetic pathways of the major terpenoid-related compounds and possible transport proteins. Proteomics. 2017;17(8):1600411. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201600411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balcke GU, Bennewitz S, Bergau N, Athmer B, Henning A, Majovsky P, et al. Multi-omics of tomato glandular trichomes reveals distinct features of central carbon metabolism supporting high productivity of specialized metabolites. Plant Cell. 2017;29(5):960–983. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald WH, Yates JR., 3rd Shotgun proteomics: integrating technologies to answer biological questions. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2003;5(3):302–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Picotti P, Aebersold R. Selected reaction monitoring-based proteomics: workflows, potential, pitfalls and future directions. Nat Methods. 2012;9(6):555–566. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Picotti P, Rinner O, Stallmach R, Dautel F, Farrah T, Domon B, et al. High-throughput generation of selected reaction-monitoring assays for proteins and proteomes. Nat Methods. 2010;7(1):43–46. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbatiello SE, Mani DR, Schilling B, Maclean B, Zimmerman LJ, Feng X, et al. Design, implementation and multisite evaluation of a system suitability protocol for the quantitative assessment of instrument performance in liquid chromatography-multiple reaction monitoring-MS (LC-MRM-MS) Mol Cell Proteom. 2013;12(9):2623–2639. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.027078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbatiello SE, Schilling B, Mani DR, Zimmerman LJ, Hall SC, MacLean B, et al. Large-scale interlaboratory study to develop, analytically validate and apply highly multiplexed, quantitative peptide assays to measure cancer-relevant proteins in plasma. Mol Cell Proteom. 2015;14(9):2357–2374. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.047050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishizaki J, Takemori A, Suemori K, Matsumoto T, Akita Y, Sada KE, et al. Targeted proteomics reveals promising biomarkers of disease activity and organ involvement in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):218. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1429-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elschenbroich S, Kislinger T. Targeted proteomics by selected reaction monitoring mass spectrometry: applications to systems biology and biomarker discovery. Mol BioSyst. 2011;7(2):292–303. doi: 10.1039/C0MB00159G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsumoto M, Nakayama KI. The promise of targeted proteomics for quantitative network biology. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2018;54:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunner E, Ahrens CH, Mohanty S, Baetschmann H, Loevenich S, Potthast F, et al. A high-quality catalog of the Drosophila melanogaster proteome. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(5):576–583. doi: 10.1038/nbt1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor NL, Fenske R, Castleden I, Tomaz T, Nelson CJ, Millar AH. Selected reaction monitoring to determine protein abundance in Arabidopsis using the Arabidopsis proteotypic predictor. Plant Physiol. 2014;164(2):525–536. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.225524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takemori N, Takemori A, Matsuoka K, Morishita R, Matsushita N, Aoshima M, et al. High-throughput synthesis of stable isotope-labeled transmembrane proteins for targeted transmembrane proteomics using a wheat germ cell-free protein synthesis system. Mol BioSyst. 2015;11(2):361–365. doi: 10.1039/C4MB00556B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawless C, Holman SW, Brownridge P, Lanthaler K, Harman VM, Watkins R, et al. Direct and absolute quantification of over 1800 yeast proteins via selected reaction monitoring. Mol Cell Proteom. 2016;15(4):1309–1322. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.054288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomato Genome Consortium The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature. 2012;485(7400):635–641. doi: 10.1038/nature11119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mallick P, Schirle M, Chen SS, Flory MR, Lee H, Martin D, et al. Computational prediction of proteotypic peptides for quantitative proteomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(1):125–131. doi: 10.1038/nbt1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schirle M, Heurtier MA, Kuster B. Profiling core proteomes of human cell lines by one-dimensional PAGE and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteom. 2003;2(12):1297–1305. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300087-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacLean B, Tomazela DM, Shulman N, Chambers M, Finney GL, Frewen B, et al. Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(7):966–968. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerber SA, Rush J, Stemman O, Kirschner MW, Gygi SP. Absolute quantification of proteins and phosphoproteins from cell lysates by tandem MS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(12):6940–6945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832254100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beynon RJ, Doherty MK, Pratt JM, Gaskell SJ. Multiplexed absolute quantification in proteomics using artificial QCAT proteins of concatenated signature peptides. Nat Methods. 2005;2(8):587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pratt JM, Simpson DM, Doherty MK, Rivers J, Gaskell SJ, Beynon RJ. Multiplexed absolute quantification for proteomics using concatenated signature peptides encoded by QconCAT genes. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(2):1029–1043. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simpson DM, Beynon RJ. QconCATs: design and expression of concatenated protein standards for multiplexed protein quantification. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;404(4):977–989. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Champagne A, Boutry M. Proteomics of terpenoid biosynthesis and secretion in trichomes of higher plant species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1864(8):1039–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farrah T, Deutsch EW, Kreisberg R, Sun Z, Campbell DS, Mendoza L, et al. PASSEL: the PeptideAtlas SRMexperiment library. Proteomics. 2012;12(8):1170–1175. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deutsch EW, Lam H, Aebersold R. PeptideAtlas: a resource for target selection for emerging targeted proteomics workflows. EMBO Rep. 2008;9(5):429–434. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsumoto M, Matsuzaki F, Oshikawa K, Goshima N, Mori M, Kawamura Y, et al. A large-scale targeted proteomics assay resource based on an in vitro human proteome. Nat Methods. 2017;14(3):251–258. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodiger A, Baginsky S. Tailored use of targeted proteomics in plant-specific applications. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1204. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mata CI, Fabre B, Hertog ML, Parsons HT, Deery MJ, Lilley KS, et al. In-depth characterization of the tomato fruit pericarp proteome. Proteomics. 2017;17(1–2):1600406. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakashima T, Wada H, Morita S, Erra-Balsells R, Hiraoka K, Nonami H. Single-cell metabolite profiling of stalk and glandular cells of intact trichomes with internal electrode capillary pressure probe electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2016;88(6):3049–3057. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wessel D, Flugge UI. A method for the quantitative recovery of protein in dilute solution in the presence of detergents and lipids. Anal Biochem. 1984;138(1):141–143. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Calderon-Celis F, Encinar JR, Sanz-Medel A. Standardization approaches in absolute quantitative proteomics with mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2018;37(6):715–737. doi: 10.1002/mas.21542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takemori N, Takemori A, Tanaka Y, Ishizaki J, Hasegawa H, Shiraishi A, et al. High-throughput production of a stable isotope-labeled peptide library for targeted proteomics using a wheat germ cell-free synthesis system. Mol BioSyst. 2016;12(8):2389–2393. doi: 10.1039/C6MB00209A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takemori N, Takemori A, Tanaka Y, Endo Y, Hurst JL, Gomez-Baena G, et al. MEERCAT: multiplexed efficient cell free expression of recombinant QconCATs For large scale absolute proteome quantification. Mol Cell Proteom. 2017;16(12):2169–2183. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA117.000284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharma V, Eckels J, Taylor GK, Shulman NJ, Stergachis AB, Joyner SA, et al. Panorama: a targeted proteomics knowledge base. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(9):4205–4210. doi: 10.1021/pr5006636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Protein assay of trichome glandular cell (TGC) samples derived from a type VI trichome of tomato. (A) Experimental workflow. The total amount of protein extracted from the TGC sample was analyzed using the Qubit protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. (B) The estimated amount of the total TGC protein derived from a single trichome from different organs (the fruits, leaves, and calyx). Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Tomato trichome glandular cell (TGC) proteins identified by gel electrophoresis-assisted liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (GeLC–MS/MS) analysis. TGC proteins were identified using ProteinPilot (SCIEX) software with a false discovery rate (FDR) of 1%. Accession: accession ID in UniProtKB database; Protein Name: name of identified protein; Identified Peptide #: number of tryptic peptide identified by MS/MS, the cut-off for peptide confidence scores was > 95; % Sequence Coverage: the percentage of the protein sequence covered by identified peptides with confidence score > 95.

Additional file 3: Figure S2. Shotgun proteomics of tomato trichome glandular cells (TGCs) using gel electrophoresis-assisted liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (GeLC–MS/MS). (A) Biological processes of the TGC proteins identified by GeLC–MS/MS. Gene ontology analysis using PANTHER 14.0 (http://pantherdb.org) was performed on the proteins identified at FDR 1%. (B) Metabolic pathways related to the proteins identified by shotgun proteomics are highlighted in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway map (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html).

Additional file 4: Table S2. Established selected reaction monitoring (SRM) assays targeting tomato trichome glandular cell (TGC) proteome. The SRM assay was developed using Skyline Software. Q1: quadrupole mass filter to select a precursor ion; Q3: quadrupole mass filter to select a fragment ion; Protein: protein targeted by the assay; Sequence: monitoring peptide sequence; Charge: charge of precursor ion selected by Q1; Fragment ion: fragment ion selected by Q3; DP: declustering potential; CE: collision energy; Verified: SRM transition which was verified using tryptic digest of tomato TGC extract.

Additional file 5: Table S3. Relative expression levels of targeted proteins in tomato trichome glandular cells (TGCs). The relative expression levels of target protein in each sample type (fruit, leaf, and calyx) was estimated based on the selected reaction monitoring (SRM) peak area of the corresponding peptide. Protein: targetedprotein name; Peptide: peptide sequence used for selected reaction monitoring (SRM) quantitative analysis.

Additional file 6: Table S4. Differential expression of trichome glandular cell (TGC) proteins between tomato organs. Fold Change: fold change for differential protein expression; p value: statistical significance; Accession: accession IDs of proteins with differential expression between different organs; Protein: targeted protein name; Peptide: peptide sequence used for selected reaction monitoring (SRM) quantitative analysis; GO - Molecular function: gene ontology annotation for molecular function; GO - Biological process: gene ontology annotation for biological process.

Additional file 7: Figure S3. Absolute quantification of targeted proteins in tomato trichome glandular cells (TGCs) using AQUA peptide. Tryptic peptides shown on the graphs were used for selected reaction monitoring (SRM) quantification.

Additional file 8: Figure S4. High-throughput generation of standard peptides for selected reaction monitoring (SRM) quantification using QconCAT strategy. (A) Experimental workflow of QconCAT biosynthesis using a wheat germ cell-free system. (B) Representative polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) images of synthesized QconCATs. For gel electrophoresis, 4%–12% NuPAGE gel was used. Separated QconCATs were visualized with CBB-R250. (C) Absolute quantification of the synthesized QconCATs. (D) SRM chromatograms of QconCATs. Tryptic digests from stable-isotope-labeled QconCATs (SOL-01 and SOL-02) were individually analyzed by liquid chromatography (LC)-SRM.

Additional file 9: Table S5. QconCAT information. Sequence: amino acid sequence of designed QconCAT; Molecular Weight: theoretical molecular weight of QconCAT; Synthesized Gene Sequence: nucleic acid sequence of artificial synthetic gene encoding QconCAT; Accession: accession ID of protein to be quantified by QconCAT; Peptide: peptide sequence used for QconCAT design; KEGG Information: information on enzymatic function from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (sly01110 Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites - Solanum lycopersicum).

Additional file 10: Figure S5. Ehime University selected reaction monitoring (SRM)/multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) reference database (ESRDB): online reference database for assays. Detailed sequence information including sequence homology of target peptides in Solanum lycopersicum and other plant species (Arabidopsis thaliana, Nicotiana tabacum, and Artemisia annua) is available.

Data Availability Statement

The SRM data files (ProteomeXchange Id: PXD012250) have been deposited at PanoramaWeb (https://panoramaweb.org/tomatotgc.url).