Abstract

This Data Descriptor announces the submission to public repositories of the monoterpene indole alkaloid database (MIADB), a cumulative collection of 172 tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) spectra from multiple research projects conducted in eight natural product chemistry laboratories since the 1960s. All data have been annotated and organized to promote reuse by the community. Being a unique collection of these complex natural products, these data can be used to guide the dereplication and targeting of new related monoterpene indole alkaloids within complex mixtures when applying computer-based approaches, such as molecular networking. Each spectrum has its own accession number from CCMSLIB00004679916 to CCMSLIB00004680087 on the GNPS. The MIADB is available for download from MetaboLights under the identifier: MTBLS142 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/MTBLS142).

Subject terms: Metabolomics, Data acquisition, Natural products

| Design Type(s) | mass spectrometry data transformation objective • mass spectrometry data analysis objective • data integration objective |

| Measurement Type(s) | mass spectrum |

| Technology Type(s) | liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| Factor Type(s) | |

| Sample Characteristic(s) | Strychnos usambarensis • Picralima nitida • Geissospermum laeve • Pleiocarpa mutica • Alstonia • Callichilia inaequalis • Chimarris cymosa • Mostuea brunonis • Gonioma < moth > • Cinchona • Catharanthus roseus • Voacanga grandifolia |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data (ISA-Tab format)

Background & Summary

Monoterpene indole alkaloids (MIAs) constitute a broad class of nitrogen-containing plant-derived natural products composed of more than 3000 members1. This natural product class is found in hundreds of plant species from the Apocynaceae, Loganiaceae, Rubiaceae, Icacinaceae, Nyssaceae, and Gelsemiaceae plant families. Throughout the six past decades, the structural intricacies and biological activities of these molecules have captured the interest of many researchers all over the world2. Examples of MIAs are the antimalarial drug of choice till the mid of the last century, quinine; the antihypertensive reserpine, and vincristine and vinblastine, which are used directly or as derivatives for the treatment of several cancer types. Recently, much effort was directed toward understanding and manipulating the underlying biosynthetic pathways of MIAs in order to engineer them in microorganisms to allow industrial production of medicinally relevant compounds3–5. Although a large amount of knowledge has been accumulated concerning the early steps6–8 and the assembly of key intermediates, many questions are still unanswered, and the discovery of new members of this family may illuminate unexpected enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of this intriguing group of natural products.

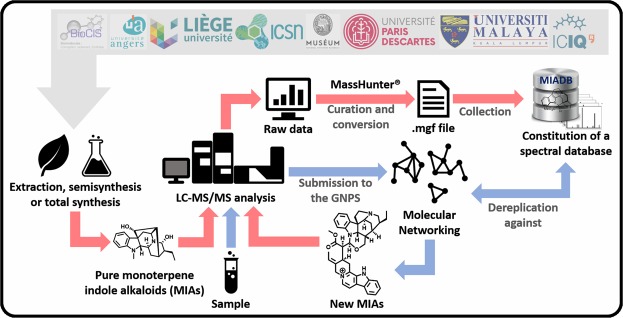

As part of our continuing interest in MIA chemistry9–12, we developed a streamlined molecular networking13 dereplication pipeline based on the implementation of an in-house MS/MS database, constituted of a cumulative collection of MIAs14. In order to enrich this database, seven prominent practitioners from the global natural products research community shared their historical collections, leading to the construction of the largest MS/MS dataset of MIAs to date, that we named: Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids DataBase (MIADB) (Fig. 1). The MIADB contains MS/MS data of 172 standard compounds, comprising 128 monoindoles and 44 bisindoles (these compounds are presented in Supplementary Table 1) and covers more than 70% of the known (30/42) MIA skeletons. The information that can be drawn from this dataset is valuable for the scientific community that envisages the isolation of new MIAs.

Fig. 1.

Construction of the MIADB (red arrows) and application in a molecular networking-based dereplication workflow (blue arrows).

The purpose of this Data Descriptor is to announce the deposition of the MIADB on the Global Natural Product Social Molecular Networking (GNPS15) and MetaboLights16. Each spectrum of the MIADB has its own accession number from CCMSLIB00004679916 to CCMSLIB00004680087 on GNPS (accessed via: https://gnps.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/static/gnps-splash.jsp). The spectral collection is also is available for download from MetaboLights under the identifier: MTBLS14217.

Methods

Sample preparation

Each of the collected MIA was diluted to a concentration of 1 mg/mL using HPLC-grade (High Performance Liquid Chromatography) with MeOH (Methanol) as solvent. The solution was then transferred in 1.5 mL HPLC vials and analyzed by LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-tandem Mass Spectrometry). Chemicals and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Data acquisition

Samples were analyzed using an Agilent LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry) system composed of an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC coupled to an Agilent 6530 ESI-Q-TOF-MS (ElectroSpray Ionization Quadrupole Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry) operating in positive mode. A Sunfire® analytical C18 column (150 × 2.1 mm; i.d. 3.5 μm, Waters) was used, with a flow rate of 250 μL/min and a linear gradient from 5% B (A: H2O + 0.1% formic acid, B: MeOH) to 100% B over 30 min. The column temperature was maintained at 25 °C. ESI conditions were set with the capillary temperature at 320 °C, source voltage at 3.5 kV, and a sheath gas flow rate of 10 L/min. Injection volume was set at 5 µL. The mass spectrometer was operated in Extended Dynamic Range mode (2 GHz). The divert valve was set to waste for the first 3 min. There were four scan events: positive MS, window from m/z 100–1200, then three data-dependent MS/MS scans of the first, second, and third most intense ions from the first scan event.

MS/MS settings were: three fixed collision energies (30, 50, and 70 eV), default charge of 1, minimum intensity of 5000 counts, and isolation width of m/z 1.3. Purine C5H4N4 [M + H]+ ion (m/z 121.050873) and hexakis(1 H,1 H,3H-tetrafluoropropoxy)-phosphazene C18H18F24N3O6P3 [M + H]+ ion (m/z 922.009798) were used as internal lock masses. Full scans were acquired at a resolution of 11 000 (at m/z 922) and 4000 at (m/z 121). A permanent MS/MS exclusion list criterion was set to prevent oversampling of the internal calibrant.

Database constitution

The analysis of each of these substances resulted in 172 files with the standard.d format (Agilent standard data-format). A list of individual compounds for each sample was generated from an Auto MS/MS data mining process implemented in MassHunter® software on every single file. Averaged as well as monocollisional energy MS/MS spectra were generated from the three retained collision energies (30, 50, and 70 eV). Within this list, the molecular formula (as well as the exact mass) of the expected compound (in its charged state) was identified. Then, depuration of the other features was carried out. Finally, each spectrum was converted into the.mgf (Mascot Generic Format) using the export tool of the MassHunter® software.

Data Records

All data described in this article have been uploaded to GNPS and MetaboLights. Each spectrum of the 172 compounds of the MIADB has its own accession number from CCMSLIB00004679916 to CCMSLIB00004680087 on the Global Natural Product Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) (accessed via: https://gnps.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/static/gnps-splash.jsp). The spectral collection in its two versions (i.e. averaged and separate collision energy MS/MS spectra at 30, 50, and 70 eV) is available for download from MetaboLights under the identifier: MTBLS14217.

Metadata

The MS/MS spectra of the MIADB library are recorded with a variety of details including: LC-MS/MS acquisition parameters, instrument details, organism, organism part, smiles and Inchi codes, CAS numbers, CHEBI IDs, retention times, and chemical formula. These metadata are available on the GNPS and MetaboLights websites.

Technical Validation

Spectroscopic validation of MIADB compounds

The structural identity of the alkaloids being implemented in the MIADB reference metabolite index was established through extensive spectroscopic analyses, including, NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) and HRMS (High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry). The analyses were carried out by the various collaborators having contributed to the establishment of the database. The obtained mass spectra were individually inspected to verify the occurrence of either the protonated molecular or molecular ion as the precursor mass.

Selected strategies for the validation of the MIADB

The validation of the MIADB was achieved following two strategies: (i) dereplication of the profiled compounds from a methanol extract of the leaves of Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don. (Apocynaceae) (see supplementary Tables 2 and 3), and (ii) the dereplication of the MIADB against the MIAs previously available on the GNPS library before the upload of the MIADB.

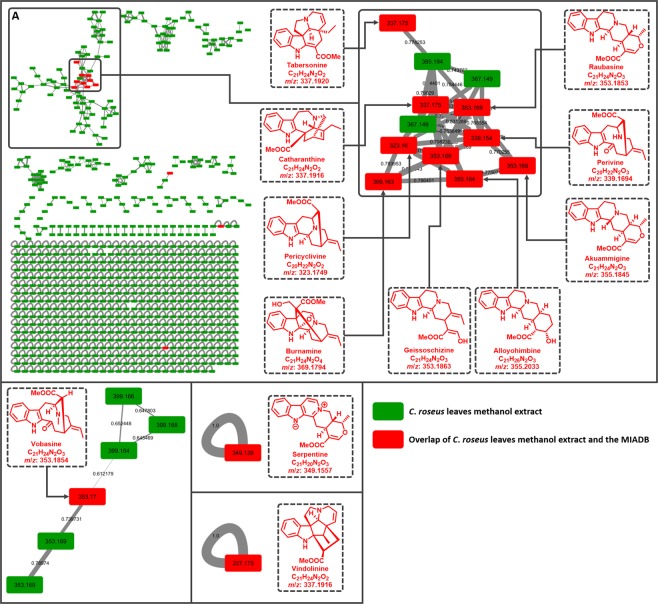

Molecular networking-based dereplication of Catharanthus roseus methanol extract

Molecular networking-based dereplication using MIADB-uploaded GNPS libraries was attempted on the methanol extract of Catharanthus roseus, the MIAs content of which was thoroughly studied. Accordingly, more than 130 different compounds were reported from the different tissues of the plant18. In the displayed network, the experimental data of C. roseus methanol extract are depicted as green rectangles and nodes representing a consensus of experimental data and database records (i.e., MIADB-uploaded in the GNPS libraries) are displayed as red rectangles (Fig. 2). As expected, molecular networking of the C. roseus leaves methanol extract allowed dereplication of previously known metabolites within this plant including: tabersonine, catharanthine, vindolinine, perivine, geissoschizine, pericyclivine, serpentine, raubasine, and akuammigine (Table 1). All the dereplicated compounds were assigned a level of confidence 1 according to Schymanski et al.19 based on HMRS, MS/MS and retention time matching, except for geissoschizine, serpentine; and alloyohimbine. The latter were attributed a level of confidence of 2, due to a delta of retention time (RT) superior to 1.5 min. The molecular networking-based dereplication provided a comprehensive coverage of C. roseus alkaloids by regards to the available standards, despite the noticeable lack of a vinblastine hit. This missing observation is likely due to the vinblastine concentration that is known to be very low in the plant (ranging from 0.0003% to 0.001% w/w dry weight)20. Conversely, some unexpected matches could also be evidenced throughout the obtained dereplication: burnamine and vobasine. Although none of these were previously described in C. roseus, both these structural assignments can be deemed reasonable based on biosynthetic considerations. Being an akuammiline-derived MIA, such as akuammine21 and the monomer precursors of the bisindoles vingramine and methylvingramine22 that have been reported to occur in C. roseus, the detection of burnamine is not unexpected. Likewise, the co-dereplication in the depicted molecular network of the formerly described vobasane-type perivine supports the identification of vobasine within this plant. Such examples emphasize the dereplicative interest of MIADB especially on such a deeply dug plant model. Prior to its GNPS upload, i.e., as an in-house database, the ability of the MIADB to pinpoint tentatively new MIAs was demonstrated through the streamlined isolation of geissolaevine along with its O-methylether derivative and 3′,4′,5′,6′-tetrahydrogeissospermine from the formerly vastly studied Geissospermum leave (Vell.) Miers (Apocynaceae)14. Altogether, the currently garnered results support the valuable contribution of MIADB either for the straightforward identification of monoterpene indole alkaloids or to highlight putative structural novelty among this privileged structural class. The topology of the obtained network also reveals that a further extent of information could yet be accessed from C. roseus extracts. Indeed, most dereplicated MIAs are tightly associated within cluster A. Since clusterization depends on structural similarity, a single match to the MIADB-implemented GNPS allows for the propagation of the structure throughout an entire molecular family, indicating that most if not all the nodes of this cluster refer to MIAs. The seminal contribution of the MIADB to the tandem mass spectrometric databanks of MIA is expected to pave the way for the upload of such data by the numerous teams involved in MIA research all over the world, thereby contributing to making this tool more and more efficient to reach a quick and sharp insight into the MIAs content of any producing organism.

Fig. 2.

Full molecular network of the profiled compounds from a methanol extract of C. roseus leaves annotated by the MIADB. The cosine similarity score cutoff for the molecular network was set at 0.6, the parent ion mass tolerance at 0.02, the fragment ion mass tolerance at 0.02, the score library threshold at 0.6 and the minimum matched peaks at 6. The cosine similarity score are depicted on the edges.

Table 1.

Matches between the profiled compounds from a methanol extract of C. roseus and MIADB.

| Compound | Match score | Comment | ΔRT (min) | Confidence level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| akuammigine | 0.69 | Described in C. roseus | 0.63 | 1 |

| alloyohimbine | 0.76 | Not described in C. roseus | 1.95 | 2 |

| burnamine | 0.62 | Not described in C. roseus | 1.07 | 1 |

| catharanthine | 0.67 | Described in C. roseus | 0.67 | 1 |

| geissoschizine | 0.71 | Described in C. roseus | 1.52 | 2 |

| pericyclivine | 0.79 | Described in C. roseus | 0.00 | 1 |

| perivine | 0.73 | Described in C. roseus | 0.01 | 1 |

| raubasine | 0.64 | Described in C. roseus | 0.26 | 1 |

| serpentine | 0.66 | Described in C. roseus | 6.65 | 2 |

| tabersonine | 0.80 | Described in C. roseus | 1.48 | 1 |

| vindolinine | 0.77 | Described in C. roseus | 1.44 | 1 |

| vobasine | 0.65 | Not described in C. roseus | 0.16 | 1 |

Dereplication of the MIADB against the MIAs previously available on the GNPS library

As a second validation assay, the MIADB was dereplicated against the GNPS library. For this purpose, the 172.mgf files were submitted to the GNPS online platform and all the hits between the MIADB and the GNPS were annotated. 19 of the total MIAs were identified as hits by the GNPS platform (Table 2).

Table 2.

MIADB matches with the GNPS library.

| Compounds (GNPS) | Match score | Compounds (MIADB) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| brucine | 0.78 | brucine | |

| reserpiline | 0.86 | reserpiline | |

| tabernaemontanine | 0.74 | tabernaemontanine | |

| voachalotine | 0.93 | voachalotine | |

| ajmaline | 0.75 | ajmaline | |

| vincamine | 0.78 | vincamine | |

| methyl reserpate | 0.83 | methyl reserpate | |

| camptothecin | 0.73 | camptothecin | |

| reserpine | 0.86 | reserpine | |

| strychnine | 0.80 | strychnine | |

| akuammigine | 0.86 | raubasine | epimer |

| raubasine | 0.88 | akuammigine | epimer |

| corynanthine | 0.90 | yohimbine | epimer |

| yohimbine | 0.92 | corynanthine | epimer |

| vincosamide | 0.93 | strictosamide | epimer |

| strictosamide | 0.93 | vincosamide | epimer |

| yohimbine | 0.90 | pseudoyohimbine | epimer |

| elegantissine | 0.73 | carapanaubine | isomer |

| yohimbine | 0.89 | alloyohimbine | epimer |

These results indicate that the compounds from the 19 matches were correctly identified within the GNPS library, except in the case of epimers or isomers. Indeed, it should be noted that the matching process does not take into account the stereochemistry of the compounds (Table 2).

Supplementary Information

ISA-Tab metadata file

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the productive collaborations and the fruitful contributions that allowed the generation of this natural products MS/MS database. This research was funded by FONDECYT-CONCYTEC (grant contract number 239-2015-FONDECYT), and by the French ANR grant (ANR-15-CE29-0001). We express our thanks to Séverine Amand (MNHN) for her assistance in the collection of the MIAs from the MNHN chemical library.

Author Contributions

M.A.B. conceived the project. A.E.F.R., C.A., E.O.N., G.C., and H.H. performed the acquisition of the LC-MS/MS data. P.L.P. performed the technical validation of the MIADB. M.S.K., F.M.M., M.E.M., and A.M.E., performed the total synthesis of grandilodines B and C and lundurine. M.G. and L.M. isolated and collected MNHN compounds. M.K., R.G., T.G., C.L. and S.M. isolated and collected compounds from Université Paris-Descartes. K.A. advised on the extraction aspects of the work conducted by H.H. D.B., A.-M.L., and P.R. collected compounds from Université d’Angers. M.F. isolated and collected compounds from Université de Liège. F.R. and M.L. collected and supervised the isolation of compounds from ICSN. G.L. performed isolation and structure elucidation of lanciferine and vincamajine. L.E. and E.P. conceived and performed the synthetic experimental works related to the obtention of bipleiophylline, voacalgine A, and leucoridine A. A.E.F.R., P.L.P., P.C. and M.A.B. supervised isolation work at Université Paris-Sud and wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and commented the manuscript.

Code Availability

The LC-MS feature detection software (MassHunter®) used in this work is commercially available from Agilent®.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

ISA-Tab metadata

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41597-019-0028-3.

Supplementary Information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41597-019-0028-3.

References

- 1.Pan Q, Mustafa NR, Tang K, Choi YH, Verpoorte R. Monoterpenoid indole alkaloids biosynthesis and its regulation in Catharanthus roseus: A literature review from genes to metabolites. Phytochemistry Rev. 2016;15:221–250. doi: 10.1007/s11101-015-9406-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pritchett BP, Stoltz BM. Enantioselective palladium-catalyzed allylic alkylation reactions in the synthesis of Aspidosperma and structurally related monoterpene indole alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2018;35:559–574. doi: 10.1039/C7NP00069C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qu Y, et al. Completion of the seven-step pathway from tabersonine to the anticancer drug precursor vindoline and its assembly in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:6224–6229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501821112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caputi L, et al. Missing enzymes in the biosynthesis of the anticancer drug vinblastine in Madagascar periwinkle. Science. 2018;360:1235–1239. doi: 10.1126/science.aat4100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dang T-TT, et al. Sarpagan bridge enzyme has substrate-controlled cyclization and aromatization modes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018;14:760–763. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0078-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miettinen K, et al. The seco-iridoid pathway from Catharanthus roseus. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3606. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salim V, Yu F, Altarejos J, Luca V. Virus-induced gene silencing identifies Catharanthus roseus 7-deoxyloganic acid-7-hydroxylase, a step in iridoid and monoterpene indole alkaloid biosynthesis. Plant J. 2013;76:754–765. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asada K, et al. A 7-deoxyloganetic acid glucosyltransferase contributes a key step in secologanin biosynthesis in Madagascar periwinkle. Plant Cell. 2013;25:4123–4134. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.115154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lachkar D, et al. Unified biomimetic assembly of voacalgine A and bipleiophylline via divergent oxidative couplings. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:793. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otogo N’Nang Obiang E, et al. Pleiokomenines A and B: Dimeric aspidofractinine alkaloids tethered with a methylene group. Org. Lett. 2017;19:6180–6183. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beniddir MA, Genta-Jouve G, Lewin G. Resolving the (19R) absolute configuration of lanciferine, a monoterpene indole alkaloid from Alstonia boulindaensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2018;81:1075–1078. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otogo N’Nang E, et al. Theionbrunonines A and B: Dimeric vobasine alkaloids tethered by a thioether bridge from Mostuea brunonis. Org. Lett. 2018;20:6596–6600. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b02961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang JY, et al. Molecular networking as a dereplication strategy. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76:1686–1699. doi: 10.1021/np400413s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox Ramos AE, et al. Revisiting previously investigated plants: A molecular networking-based study of Geissospermum laeve. J. Nat. Prod. 2017;80:1007–1014. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b01013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang M, et al. Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:828–837. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haug K, et al. MetaboLights—an open-access general-purpose repository for metabolomics studies and associated meta-data. Nucl. Acids Res. 2013;41:D781–D786. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox Ramos, A. E. et al. Collected mass spectrometry data on monoterpene indole alkaloids from natural product chemistry research. MetaboLights, http://identifiers.org/metabolights:MTBLS142 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Heijden RVD, Jacobs DI, Snoeijer W, Hallard D, Verpoorte R. The Catharanthus alkaloids: Pharmacognosy and biotechnology. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004;11:607–628. doi: 10.2174/0929867043455846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schymanski EL, et al. Identifying small molecules via high resolution mass spectrometry: Communicating confidence. Environment. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:2097–2098. doi: 10.1021/es5002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uniyal GC, Bala S, Mathur AK, Kulkarni RN. Symmetry C18 column: a better choice for the analysis of indole alkaloids of Catharanthus roseus. Phytochem. Anal. 2001;12:206–210. doi: 10.1002/pca.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramirez A, Garcia-Rubio S. Current progress in the chemistry and pharmacology of akuammiline alkaloids. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:1891–1915. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jossang A, Fodor P, Bodo B. A new structural class of bisindole alkaloids from the seeds of Catharanthus roseus: Vingramine and methylvingramine. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:7162–7167. doi: 10.1021/jo972333t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The LC-MS feature detection software (MassHunter®) used in this work is commercially available from Agilent®.