Abstract

The plant-specific transcription factor TCPs play multiple roles in plant growth, development, and stress responses. However, a genome-wide analysis of TCP proteins and their roles in salt stress has not been declared in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.). In this study, 42 PvTCP genes (PvTCPs) were identified from the switchgrass genome and 38 members can be anchored to its chromosomes unevenly. Nine PvTCPs were predicted to be microRNA319 (miR319) targets. Furthermore, PvTCPs can be divided into three clades according to the phylogeny and conserved domains. Members in the same clade have the similar gene structure and motif localization. Although all PvTCPs were expressed in tested tissues, their expression profiles were different under normal condition. The specific expression may indicate their different roles in plant growth and development. In addition, approximately 20 cis-acting elements were detected in the promoters of PvTCPs, and 40% were related to stress response. Moreover, the expression profiles of PvTCPs under salt stress were also analyzed and 29 PvTCPs were regulated after NaCl treatment. Taken together, the PvTCP gene family was analyzed at a genome-wide level and their possible functions in salt stress, which lay the basis for further functional analysis of PvTCPs in switchgrass.

1. Introduction

The TCP gene family is a class of plant-specific genes encoding proteins with the conserved TCP domain, a 59 amino acid motif that allows DNA binding and protein interaction. The so-called “TCP” is named from four initially identified transcription factors: TEOSINTE BRANCHED1 (TB1) from maize (Zea mays), which involved in apical dominance regulation [1, 2]; CYCLOIDEA (CYC) from snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus), which controlled floral asymmetry [3]; and the PROLIFERATING CELL FACTORS 1 and 2 (PCF1 and PCF2) from rice (Oryza sativa), which are essential for meristematic tissue-specific expression [4]. To date, TCP genes have been identified in a number of plant species. For example, there are 24 TCP members that were found in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) genome, and 28 in rice genome, 30 in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), 21 in medicago (Medicago truncatula), 36 in poplar (Populus trichocarpa), and 39 in turnips (Brassica rapa ssp. rapa) [5–10]. TCP proteins can be divided into two main classes according to their sequences of TCP conserved domain and phylogenetic relationships, which were referred to as class I (also called PCF class or TCP-P class) and class II (also named as TCP-C class) [11, 12]. In angiosperms, class II can be further classified into two clades based on their differences within the TCP domain, which were named as clade CYC/TB1 and clade CIN (CINCINNATA) [5].

TCP proteins play vital roles in plant growth, development, and responses to biotic/abiotic stresses [5, 13]. Class I TCP members were mainly involved in promoting cell proliferation and differentiation by regulating plant hormone signaling, such as gibberellin, auxin, cytokinin, and abscisic acid [13–18]. Class II TCP members were approximately reported to participate in lateral organ development. Furthermore, the origin of clade CYC/TB1 members has occurred later than clade CIN members in angiosperms, and they are primarily involved in shoot branching and apical dominance regulation [5]. TB1 functions as a transcriptional regulator of strong apical dominance and controls the tillering in maize [2]. AtTCP18 (BRANCHED1, BRC1) and AtTCP12 (BRANCHEND2, BRC2) in Arabidopsis, two orthologs of maize TB1, are highly expressed in axillary buds and negatively regulate shoot branching [19, 20]. Additionally, jaw-TCPs, the targets of miR319 are almost a cluster of CIN members, and microRNA319- (miR319-) targeted TCPs take part in plant cell wall biosynthesis, abiotic stress response, and flowering time regulation in Arabidopsis and rice [21–23]. It was also reported that miR319-targeted TCPs play a role in plant response to salt stress in bentgrass [24, 25]. Besides, some of the TCP genes in Phaseolus vulgaris which are identified can respond under salt stress [26]. However, the regulation mechanism of TCP transcriptional factors involved in the salt stress has not been elucidated.

Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) is a perennial C4 warm-season tall grass used as a bioenergy and animal feedstock for its impressive biomass yield and can confer tolerance to drought, salinity, and poor nutrition [27]. Due to the recent study on high-throughput genome sequencing and assembling, establishment of gene expression atlas, genetic-linkage mapping, and high-efficiency transformation system [28, 29], switchgrass has been developed into the model species as energy grass. The function of numerous genes in switchgrass has been gradually clarified, especially on stress response and development regulation. Until now, WRKY, CCCH, SPL, and ARF gene families had been comprehensively analyzed at the whole-genome level in switchgrass [30–33]. Furthermore, transcriptome microRNAs and long noncoding RNAs exposed to drought stress had been sequenced and analyzed to study the systematic regulatory mechanism of drought response in switchgrass [34–36].

Large amounts of switchgrass will be cultivated on marginal land to avoid competing with food crops for the use of arable fields. Thus, switchgrass regularly faces adverse growth conditions, such as salinity, drought, and extreme temperatures. Analysis has indicated that the TCP gene family can respond to salt tolerance, while still little is known about the response of TCP genes in switchgrass under a salt stress condition [24, 25]. In this study, a total of 42 TCP members were identified in the switchgrass genome. Genome-wide analysis was carried out, including biochemical characterization, phylogenetic analysis, gene structure arrangement, chromosome location, expression profiles of tissue-specific pattern, and responsive pattern under salt stress. Therefore, this work would help us to study the profound functions of the PvTCPs in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sequence Retrieval and Identification of PvTCPs

The hidden Markov model (HMM) profile of the conserved TCP domain (pfam06507) was retrieved from the Pfam protein family database (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/) and used as a query for BLAST searches against the switchgrass genome database in Phytozome v12.0 (Panicum virgatum v4.0, DOE-JGI, http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/). The candidates were selected for further analysis if the E value was less than 1e −10. Subsequently, we corrected some errors in annotation of TCP coding sequences on the basis of the switchgrass unitranscript (PviUTs) database (https://switchgrassgenomics.noble.org/) [28]. Finally, all putative PvTCPs were confirmed to be TCP proteins by the Pfam program (http://pfam.xfam.org/), and the peptide length, molecular weight, and isoelectric point parameters of each PvTCP were calculated by the online ExPASy program (https://www.expasy.org/tools/).

2.2. Chromosomal Location and Gene Duplication of PvTCPs

The lowland switchgrass cultivar, Alamo, is allotetraploid (2n = 4x = 36) and consists of two highly homologous subgenomes, designated as ChrN and ChrK (Panicum virgatum v4.0, DOE-JGI, http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/). The chromosomal location of each PvTCP was completed using MapChart2.2 based on the physical map in Phytozome v12.0 [37]. Tandem gene duplication was defined as paralogous genes located within 50 kb in tandem and was separated by fewer than five nonhomologous spacer genes [38].

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of the TCP Proteins

To comprehensively analyze the evolutionary relationships of the TCP proteins in switchgrass, we used putative PvTCPs along with TCP proteins from Arabidopsis (model species of dicots) and rice (model species of monocots) to construct a phylogenetic tree. Sequences of the Arabidopsis and rice TCP proteins were retrieved from TAIR (https://www.arabidopsis.org/) and rice genome database (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/), respectively. Clustal X1.83 was used to do the multiple alignment of the selected TCPs [39]. The neighbor-joining tree (bootstrap value = 1000) was constructed using MEGA5.0 [40] and then manually improved by the online program EvolView (http://www.evolgenius.info/evolview/).

2.4. Gene Structure, Conserved Motif, and cis-Acting DNA Element Analysis

The exon/intron structure of PvTCPs was determined by comparing the coding sequences and corresponding genomic sequences in the Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS, http://gsds1.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) [41]. Conserved motifs were analyzed using the MEME program (http://meme-suite.org/) [42]. The cis-acting DNA element analysis was performed in the promoter sequences (2 kb upstream region) of the PvTCPs using the online program PLACE (a database of plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements, https://sogo.dna.affrc.go.jp/). Ka/Ks calculation was analyzed by PAL2NAL [43].

2.5. Preparation for Plant Materials

Switchgrass cultivar the lowland Alamo (introduced from the USA and domesticated at Qingdao, China) was used as inbred line for the study. Tissue-cultured seedlings of switchgrass, which can eliminate the interference of genetic background, were subjected to salt stress (about vegetative 3 stage) [44, 45]. During the treatment, 1/2 MS medium supplied with 250 mM NaCl was irrigated [31]. The seedlings irrigated with 1/2 MS medium were regarded as control. Shootings were harvested from three seedlings for each point, and the collection was repeated three times as biological replicates. Samples were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C prior to analysis.

2.6. Expression Pattern Analysis of PvTCPs

Each of the PvTCPs' transcript sequence was used as a query to blast against the public database of switchgrass (https://switchgrassgenomics.noble.org/). The expression data of spatiotemporal patterns were retrieved, and pretty heatmap was constructed using the online program ImageGP (http://www.ehbio.com/ImageGP/). Total RNA of samples were extracted using the TRIzol method (Invitrogen Life Technologies, USA). The isolated RNA was subsequently treated with RNase-Free DNase I (Roche, http://www.roche.com). The first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA of each sample, using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa, http://www.takarabiomed.com.cn/) according to the protocol. The primers used in this study were showed in Table S1. PvUBQ (GenBank accession number: HM209468) was used as the reference gene. qRT-PCR was performed with real-time PCR system (LightCycler 480) using TB Green Premix EX Taq II kit (TaKaRa, Japan) and the methods described in the previous study [32]. Each PCR assay was run in triplicate for three independent biological repeats.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Chromosomal Location of PvTCPs

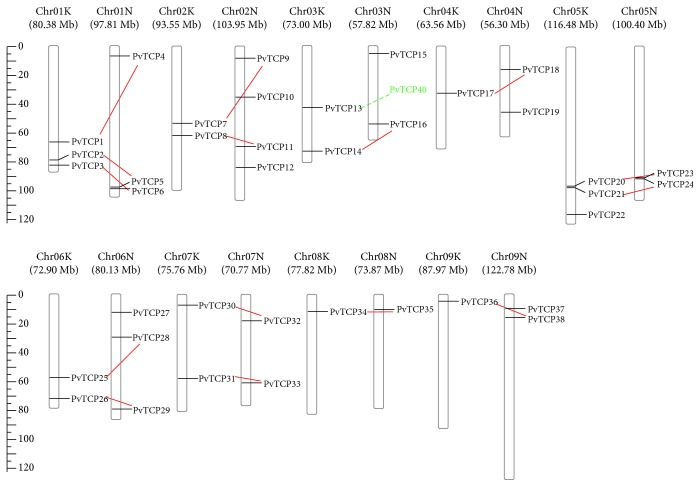

To identify TCP proteins in switchgrass, the hidden Markov model (HMM) profile of the conserved TCP domain (pfam03634) was used as a blast query to search against the public available switchgrass genome database (Phytozome v12). A total of 42 putative TCP members were identified, which were named as PvTCP1 to PvTCP42 according to their chromosomal location (Figure 1; Table 1). In general, 90.5% (38 out of 42) of PvTCPs are anchored onto the chromosomes, while the other four genes are located on an unmapped region. The distribution and density of PvTCPs on chromosomes were not uniform (Figure 1). Since switchgrass experienced a whole-genome allotetraploidization (2n = 4x = 36), the PvTCPs exist as paralogous gene pairs in the genome, and the sequence similarity between the gene pairs was larger than 90% (data not shown). 15 pairs of PvTCPs are putatively distributed on the ChrN and ChrK, respectively (Figure 1). The numbers for PvTCPs on Chr 2, 5, 6, and 7 are two pairs of PvTCPs. Chr 1 has three pairs, while Chr 3, 4, 8, and 9 each only has one pair of PvTCPs (Figure 1). In addition, according to the results of the specific location of each PvTCP, no tandem repeat gene was detected in switchgrass (Figure 1; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Chromosomal localization of switchgrass TCP genes. Chromosomal localization of PvTCPs was based on the physical map described in Phytozome v12.0. A total of 38 PvTCPs were anchored onto the chromosomes. ChrK and ChrN are two sets of subgenomes of switchgrass (2n = 4x = 36). The scale on the left represented the physical length of the chromosomes; Mb = million base pair. The red line represented a pair of paralogous TCP genes. The green character style represented putative gene pairs.

Table 1.

Overview of TCP genes in switchgrass.

| Gene namea | Gene IDb | ORF length (bp) | Deduced polypeptide | Chr | Chr location | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (aa) | MW (kDa) | pI | |||||

| PvTCP1 | Pavir.1KG397100 | 663 | 220 | 22.53 | 9.83 | 01K | 63645349-63646113 |

| PvTCP2 | Pavir.1KG510200 | 1188 | 395 | 39.93 | 9.42 | 01K | 75765762-75768115 |

| PvTCP3 | Pavir.1KG552700 | 681 | 226 | 23.00 | 9.79 | 01K | 79521775-79523415 |

| PvTCP4 | Pavir.1NG030900 | 426 | 141 | 14.49 | 10.42 | 01N | 3887213-3889118 |

| PvTCP5 | Pavir.1NG539700 | 1206 | 401 | 40.27 | 9.42 | 01N | 89471749-89473804 |

| PvTCP6 | Pavir.1NG547900 | 663 | 220 | 22.50 | 10.09 | 01N | 96987327-96989924 |

| PvTCP7 | Pavir.2KG036700 | 957 | 318 | 33.85 | 6.29 | 02K | 5031244-5036367 |

| PvTCP8 | Pavir.2KG296300 | 801 | 266 | 28.62 | 6.05 | 02K | 65347281-65349763 |

| PvTCP9 | Pavir.2NG040500 | 1293 | 430 | 45.36 | 9.32 | 02N | 5718258-5719550 |

| PvTCP10 | Pavir.2NG168500 | 933 | 310 | 32.42 | 10.10 | 02N | 32012380-32013416 |

| PvTCP11 | Pavir.2NG320400 | 795 | 264 | 28.39 | 6.21 | 02N | 59626967-59628392 |

| PvTCP12 | Pavir.2NG441900 | 990 | 329 | 33.63 | 4.95 | 02N | 81045305-81046294 |

| PvTCP13 | Pavir.3KG357500 | 870 | 289 | 30.21 | 8.93 | 03K | 28804800-28807508 |

| PvTCP14 | Pavir.3KG547300 | 870 | 289 | 30.66 | 6.38 | 03K | 69673046-69678099 |

| PvTCP15 | Pavir.3NG031100 | 1200 | 399 | 40.43 | 5.99 | 03N | 2368139-2370112 |

| PvTCP16 | Pavir.3NG279000 | 864 | 287 | 30.06 | 5.96 | 03N | 52604278-52608164 |

| PvTCP17 | Pavir.4KG172900 | 1197 | 398 | 40.38 | 8.97 | 04K | 10928170-10929640 |

| PvTCP18 | Pavir.4NG098900 | 1173 | 389 | 39.50 | 7.83 | 04N | 13829961-13832629 |

| PvTCP19 | Pavir.4NG231900 | 978 | 325 | 34.15 | 6.29 | 04N | 19989691-19991909 |

| PvTCP20 | Pavir.5KG544700 | 1251 | 416 | 44.33 | 6.38 | 05K | 94391370-94392775 |

| PvTCP21 | Pavir.5KG556600 | 837 | 278 | 29.62 | 8.08 | 05K | 95365227-95369286 |

| PvTCP22 | Pavir.5KG742600 | 978 | 325 | 33.98 | 6.37 | 05K | 113279411-113281724 |

| PvTCP23 | Pavir.5NG501800 | 1272 | 423 | 45.00 | 6.41 | 05N | 86933569-86934999 |

| PvTCP24 | Pavir.5NG508900 | 531 | 176 | 18.87 | 9.75 | 05N | 87491419-87493406 |

| PvTCP25 | Pavir.6KG270000 | 849 | 282 | 30.48 | 6.80 | 06K | 55905938-55907215 |

| PvTCP26 | Pavir.6KG395100 | 1065 | 354 | 36.50 | 5.51 | 06K | 70566109-70567758 |

| PvTCP27 | Pavir.6NG051800 | 1215 | 404 | 42.02 | 9.02 | 06N | 10745904-10747230 |

| PvTCP28 | Pavir.6NG140000 | 711 | 236 | 25.40 | 5.61 | 06N | 58122711-58123421 |

| PvTCP29 | Pavir.6NG344700 | 1329 | 442 | 45.95 | 8.82 | 06N | 77613527-77615377 |

| PvTCP30 | Pavir.7KG023900 | 525 | 174 | 18.14 | 8.25 | 07K | 23221010-23224633 |

| PvTCP31 | Pavir.7KG255700 | 606 | 201 | 20.79 | 10.01 | 07K | 56383609-56384723 |

| PvTCP32 | Pavir.7NG066100 | 285 | 94 | 9.70 | 4.59 | 07N | 15663289-15674390 |

| PvTCP33ζ | Pavir.7NG333200 | 603 | 200 | 20.79 | 9.82 | 07N | 55200631-55201233 |

| PvTCP34 | Pavir.8KG079400 | 1209 | 402 | 41.22 | 8.77 | 08K | 9383778-9386025 |

| PvTCP35 | Pavir.8NG062800 | 1191 | 396 | 40.65 | 9.13 | 08N | 8490834-8493093 |

| PvTCP36 | Pavir.9KG031700 | 1110 | 369 | 39.15 | 8.55 | 09K | 2411064-2412737 |

| PvTCP37 | Pavir.9NG079800 | 1158 | 385 | 39.42 | 9.32 | 09N | 5336448-5340260 |

| PvTCP38 | Pavir.9NG142700 | 1116 | 371 | 39.78 | 8.39 | 09N | 13496559-13498279 |

| PvTCP39 | Pavir.J125500 | 582 | 193 | 19.25 | 10.19 | scaffold14987 | 1395-1995 |

| PvTCP40 | Pavir.J227000 | 888 | 295 | 31.09 | 8.91 | scaffold20 | 54419-56973 |

| PvTCP41 | Pavir.J362100 | 1335 | 444 | 46.34 | 6.78 | scaffold276 | 1-2111 |

| PvTCP42 | Pavir.J675700 | 1353 | 450 | 46.78 | 6.67 | scaffold7087 | 83-2442 |

aGene name referred to the identified PvTCP genes in switchgrass in this study. bGene ID in Phytozome v12.0 database. ζCorrected TCP genes by PCR and PviUTs database (https://switchgrassgenomics.noble.org/).

Biochemical properties of PvTCP members were globally analyzed. Based on the detailed information, lengths of these predicted PvTCP peptides ranged from 94 (PvTCP32) to 450 (PvTCP42) amino acids and molecular weight from 9.70 (PvTCP32) to 46.79 (PvTCP42) KDa (Table 1). The isoelectric point varied from 4.59 (PvTCP32) to 10.42 (PvTCP4) (Table 1).

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of TCPs

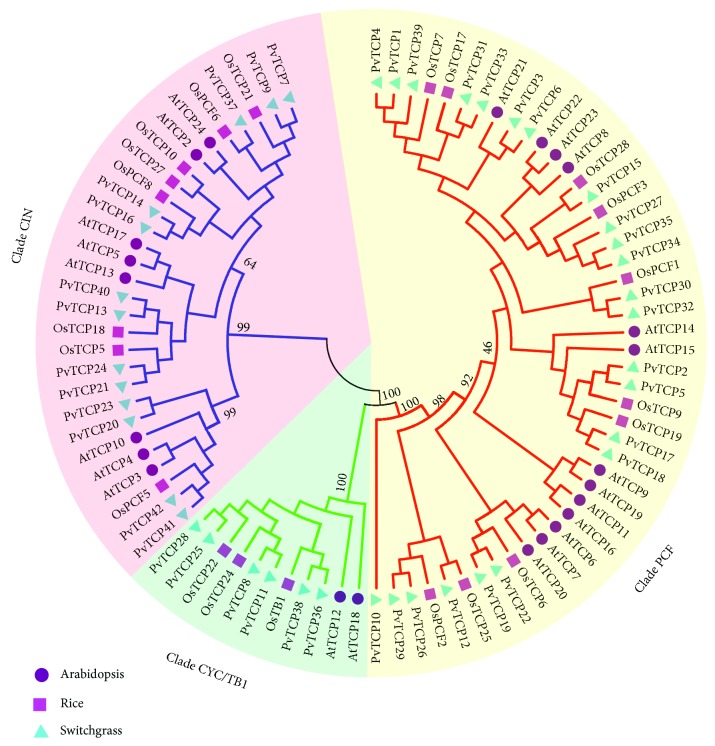

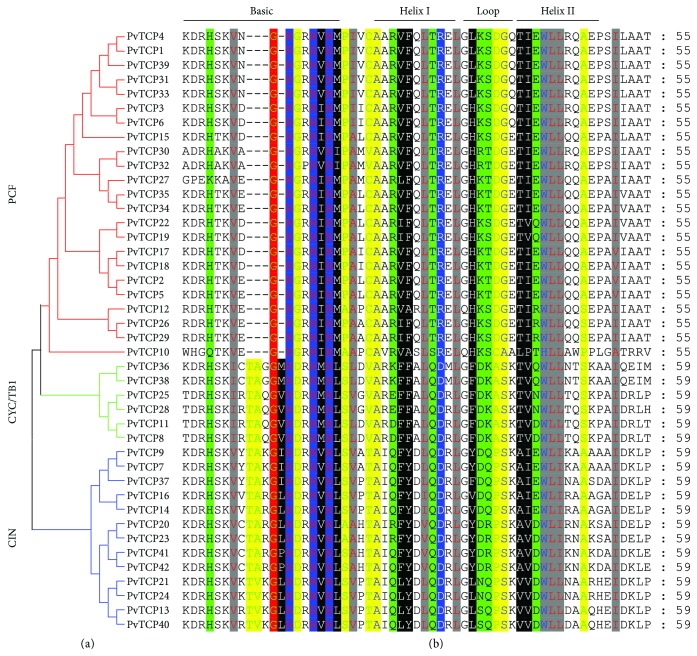

In order to comprehensively dissect the function of PvTCPs, phylogenetic relationships were firstly analyzed. An unrooted phylogenetic neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed based on the multiple sequence alignments of TCP proteins from switchgrass, Arabidopsis, (model species of dicots) and rice (model species of monocots). Two main classical subfamilies were obviously distinguished according to the NJ tree topology and bootstrap values (higher than 50%), which were referred to as class clades I and II. 23 PvTCPs are classified into clade I (PCF), and the rest 19 members are classified into class II (Figure 2; Table S2). The class II group is further divided into clade CIN (13 members) and clade CYC/TB1 (six members) (Figure 2). For the paralogous gene pairs, like PvTCP1/4, PvTCP2/5, and PvTCP3/6, they are all clustered together in the phylogenetic tree, indicating the phylogenetic signature of allotetraploidization (Figure 2). The sequence alignment analysis shows that almost all PvTCP proteins contain the conserved basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) domain, and the members that belonged to clade I (PCF) have a four amino acid deletions in the bHLH domain compared with class II (CYC/TB1 and CIN) (Figure 3). This result was consistent with the phylogenetic analysis.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of TCP proteins in switchgrass, Arabidopsis, and rice. An unrooted neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed using MEGA5.0 (bootstrap value = 1,000) after the multiple alignment of peptide sequences. All sequences used in this project were retrieved from the public genome database Phytozome v12.0 (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html#). The detailed information was listed in Table S2.

Figure 3.

Alignment of the predicted conserved basic helix-loop-helix domain sequence of switchgrass TCP members. Amino acids are expressed in the standard single-letter code. (a) Three clades were classified according to an unrooted NJ tree, which were constructed using PvTCP peptides. (b) Multiple sequence alignment was generated by GenDoc.

PvTCPs in both class I and II gathered closely with the counterparts in rice, rather than Arabidopsis, which might imply that TCP genes were duplicated after the diversification of dicot and monocot species in angiosperms (Figure 2). Ka/Ks ratios were subsequently calculated between PvTCPs and OsTCPs (Table 2). The results showed that about 1/3 orthologous genes belonged to purifying selection between the evolution of switchgrass and rice; the other 2/3 orthologous genes belonged to positive selection.

Table 2.

Ka/Ks ratio of TCP orthologous genes between switchgrass and rice.

| Orthologous genes | Ka/Ks ratio | Selection pattern |

|---|---|---|

| PvTCP1/4 vs. OsTCP7 | 0.026 | Purifying selection |

| PvTCP39 vs. OsTCP7 | 99.000 | Positive selection |

| PvTCP31/33 vs. OsTCP17 | 99.000 | Positive selection |

| PvTCP15 vs. OsTCP28 | 99.000 | Positive selection |

| PvTCP27 vs. OsPCF3 | 99.000 | Positive selection |

| PvTCP34/35 vs. OsPCF3 | 99.000 | Positive selection |

| PvTCP30/32 vs. OsPCF1 | 99.000 | Positive selection |

| PvTCP2/5 vs. OsTCP9 | 99.000 | Positive selection |

| PvTCP17/18 vs. OsTCP19 | 1.250 | Positive selection |

| PvTCP19/22 vs. OsTCP6 | 26.467 | Positive selection |

| PvTCP12 vs. OsTCP25 | 99.000 | Positive selection |

| PvTCP26/29 vs. OsPCF2 | 0.552 | Purifying selection |

| PvTCP36/38 vs. OsTB1 | 0.847 | Purifying selection |

| PvTCP8/11 vs. OsTCP24 | 0.474 | Purifying selection |

| PvTCP25/28 vs. OsTCP22 | 0.516 | Purifying selection |

| PvTCP41/42 vs. OsPCF5 | 99.000 | Positive selection |

| PvTCP21/24 vs. OsTCP5 | 99.000 | Positive selection |

| PvTCP13/40 vs. OsTCP18 | 0.665 | Purifying selection |

| PvTCP14/16 vs. OsPCF8 | 99.000 | Positive selection |

| PvTCP37 vs. OsPCF6 | 0.032 | Purifying selection |

| PvTCP7/9 vs. OsTCP21 | 99.000 | Positive selection |

3.3. Gene Structure, Conserved Motifs, and Recognition Sites of miR319

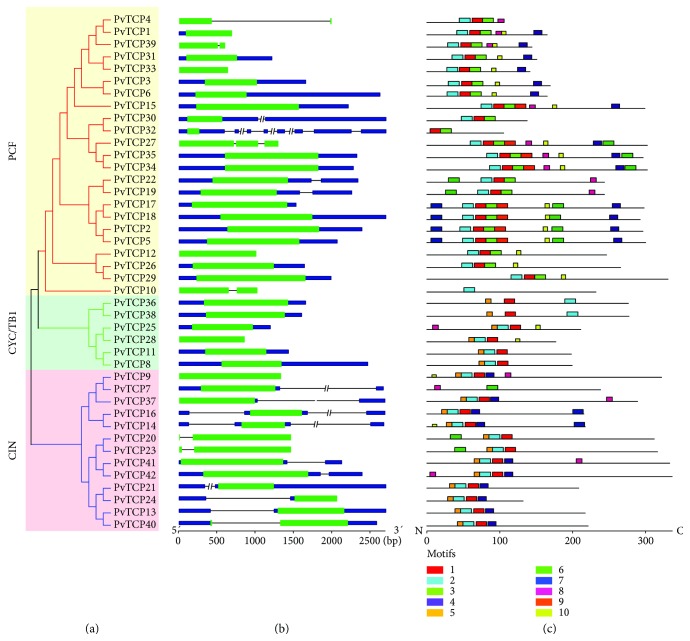

To understand the evolution of PvTCP gene family, introns in TCP genes and conserved motifs of their coding proteins were analyzed (Figure 4). All members in the CYC/TB1 group contain no introns. The intron/exon organization in the PCF clade was relatively conserved, with 14 of 23 members that had no introns, four that had one intron in the coding sequence (CDS) region, one that had two introns in the CDS region, and four that contained one or three introns in the untranslated region (UTR). Introns of PvTCPs in clade CIN was not conserved as those in other clades: three contain one intron in the CDS region, nine possessed one or two introns in the UTR region, and only one gene contain no intron (Figure 4). The conserved motifs were also analyzed and ten motifs were identified in PvTCPs using the MEME tool (Figure 4). Motifs 1 and 2 are conserved in PvTCPs except for PvTCP7, PvTCP10, PvTCP32, and PvTCP33. Proteins in the same clade of the phylogenetic tree contain similar motif arrangement. Motif 3 was conserved in all PvTCP proteins of clade PCF except for PvTCP10. Proteins in the other two clades, except for PvTCP7, PvTCP20, and PvTCP23, did not harbor motif 3. This is the same case for motifs 6 and 10. Most PvTCP proteins in clade PCF contain motifs 6 and 10, but not for proteins in clades CYC/TB1 and CIN. Motif 4 was only conserved in clades PCF and CIN, and motif 5 was conserved in clades CYC/TB1 and CIN. Only proteins in clade CIN contain the motif 7. These results implied that TCP transcription factors might take diverse roles in switchgrass due to their structure diversity.

Figure 4.

Gene structures and motif locations of switchgrass TCP genes. (a) Three clades were classified according to an unrooted NJ tree, which were constructed using PvTCP peptides. (b) Exon/intron arrangements of the PvTCP gene. Exons, introns, and untranslated region (UTR) were represented by green boxes, black lines, and blue boxes, respectively. Nucleic acid lengths are indicated by the scale at the bottom; bp = base pair. (c) Schematic representation of conserved motifs in the PvTCP proteins predicted by the MEME program. Each motif is represented by a number in the colored box. The black lines represented the nonconserved sequences. Lengths of motifs for each PvTCP protein were displayed proportionally. aa = amino acid.

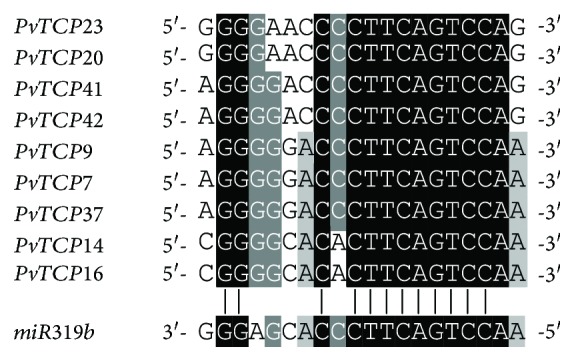

It was reported that TCP genes can be posttranscriptionally regulated by miR319 [25]. Similarly, nine PvTCP genes contain miR319 binding sites, which were located in the CDS, and all of these miR319-targeted PvTCPs were CIN family members (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Putative microRNA319-targeted binding sites of the PvTCPgenes. Alignment of complementary pairing bases was generated by GenDoc. Targeted sites were retrieved from the coding sequences of PvTCP genes, while mature sequence of miR319 was rice miR319b from miRBase (http://www.mirbase.org/).

3.4. Tissue Expression Profiles of the PvTCPs

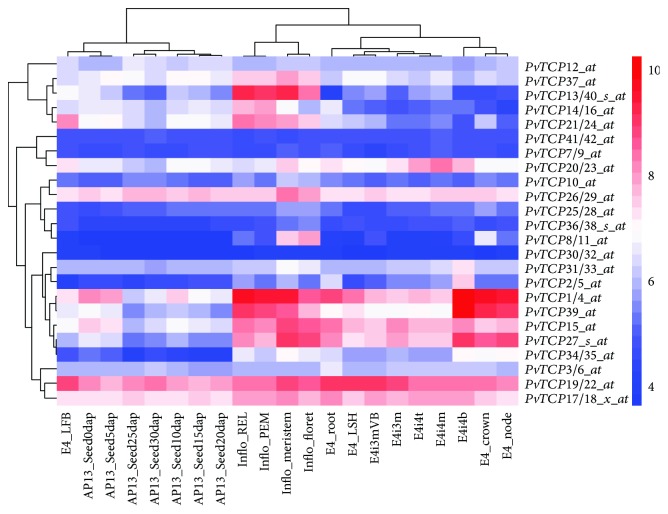

To roundly speculate the function of PvTCP proteins, cis-acting DNA elements in the promoter of each PvTCPs were retrieved and analyzed (Table S4). The results showed that 18, 15, and 13 elements were, respectively, shared in clades PCF, CYC/TB1, and CIN (Table 3). Obviously, photosynthesis, environmental stress response, and phytohormone regulation were the three major aspects in which TCP proteins were involved. In order to deeply analyze the tissue expression profiles of the PvTCP family, microarray data was obtained from the public database. As expected, both PvTCPs of the gene pair share one probe (Table S3). All PvTCPs were expressed in the examined tissues (leaf, node, internode, root, flower, and seed) (Figure 6). Part of the genes in the same clade exhibited similar expression mode. For example, members in clade CIN (PvTCP37, PvTCP13/40, PvTCP14/16, and PvTCP21/24) predominantly expressed in flowers, which might take roles in pollen development. Genes in clade PCF, like PvTCP1/4, PvTCP39, PvTCP15, and PvTCP27, represented a high expression level in flowers, node, and seed of E4 stage. Besides, PvTCP26/29, PvTCP19/22, and PvTCP17/18 displayed high expression levels in all tested tissues, while PvTCP10, PvTCP25/28, PvTCP36/38, PvTCP30/32, PvTCP7/9, and PvTCP41/42 were expressed relatively low in all tested tissues.

Table 3.

Putative cis-acting DNA elements in the promoter of PvTCP genes.

| Clade name | Element no.a | Element nameb | Signal sequencec | Putative functiond | FOe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCF | S000449 | CACTFTPPCA1 | YACT | Photosynthesis | 237 |

| S000265 | DOFCOREZM | AAAG | Photosynthesis; leaf and shoot development | 213 | |

| S000454 | ARR1AT | NGATT | Cytokinin response | 161 | |

| S000198 | GT1CONSENSUS | GRWAAW | HR reaction f ; systemic acquired resistance | 146 | |

| S000407 | MYCCONSENSUSAT | CANNTG | Abiotic stress; salinity stress | 143 | |

| S000144 | EBOXBNNAPA | CANNTG | Salinity stress; phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | 143 | |

| S000501 | CGCGBOXAT | VCGCGB | Calmodulin; auxin response | 108 | |

| S000447 | WRKY71OS | TGAC | Biotic and abiotic stress; GA response | 97 | |

| S000378 | GTGANTG10 | GTGA | Pollen development; pectin regulation | 95 | |

| S000493 | CURECORECR | GTAC | Copper; oxygen; hypoxic reaction | 92 | |

| S000245 | POLLEN1LELAT52 | AGAAA | Pollen development | 91 | |

| S000415 | ACGTATERD1 | ACGT | Photosynthesis | 74 | |

| S000462 | NODCON2GM | CTCTT | Root nodulin | 66 | |

| S000203 | TATABOX5 | TTATTT | Glutamine synthetase | 45 | |

| S000457 | WBOXNTERF3 | TGACY | Jasmonic acid response | 43 | |

| S000179 | MYBPZM | CCWACC | Flavonoid biosynthesis; seed development | 37 | |

| S000176 | MYBCORE | CNGTTR | Abiotic stress; salinity; flavonoid biosynthesis | 35 | |

|

| |||||

| CYC/TB1 | S000449 | CACTFTPPCA1 | YACT | Photosynthesis | 87 |

| S000265 | DOFCOREZM | AAAG | Photosynthesis; leaf and shoot development | 53 | |

| S000407 | MYCCONSENSUSAT | CANNTG | Abiotic stress; salinity stress | 48 | |

| S000144 | EBOXBNNAPA | CANNTG | Salinity stress; phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | 48 | |

| S000198 | GT1CONSENSUS | GRWAAW | HR reaction; systemic acquired resistance | 38 | |

| S000454 | ARR1AT | NGATT | Cytokinin response | 33 | |

| S000378 | GTGANTG10 | GTGA | Pollen development; pectin regulation | 32 | |

| S000447 | WRKY71OS | TGAC | Biotic and abiotic stress; GA response | 21 | |

| S000482 | SORLIP1AT | GCCAC | phyA; phytochrome; light response | 17 | |

| S000203 | TATABOX5 | TTATTT | Glutamine synthetase | 14 | |

| S000030 | CCAATBOX1 | CCAAT | Heat shock response | 13 | |

| S000103 | SEF4MOTIFGM7S | RTTTTTR | Seed globulin | 10 | |

|

| |||||

| CIN | S000449 | CACTFTPPCA1 | YACT | Photosynthesis | 153 |

| S000454 | ARR1AT | NGATT | Cytokinin response | 132 | |

| S000265 | DOFCOREZM | AAAG | Photosynthesis; leaf and shoot dvelopment | 103 | |

| S000407 | MYCCONSENSUSAT | CANNTG | Abiotic stress; salinity stress | 77 | |

| S000144 | EBOXBNNAPA | CANNTG | Salinity stress; phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | 77 | |

| S000501 | CGCGBOXAT | VCGCGB | Calmodulin; auxin response | 69 | |

| S000198 | GT1CONSENSUS | GRWAAW | HR reaction; systemic acquired resistance | 64 | |

| S000447 | WRKY71OS | TGAC | Biotic and abiotic stress; GA response | 49 | |

| S000493 | CURECORECR | GTAC | Copper; oxygen; hypoxic reaction | 48 | |

| S000378 | GTGANTG10 | GTGA | Photosynthesis; leaf and shoot development | 43 | |

| S000203 | TATABOX5 | TTATTT | Glutamine synthetase | 27 | |

| S000103 | SEF4MOTIFGM7S | RTTTTTR | Seed globulin | 26 | |

| S000245 | POLLEN1LELAT52 | AGAAA | Pollen development | 21 | |

a-cThe ID number, name, and signal sequences of the element in the online PLACE program (https://sogo.dna.affrc.go.jp/). dThe putative function of each element predicted by the online PLACE program and references from NCBI. eFrequency of occurrence in the promoters of TCP genes in each clade. fCharacters in bold represent those functions related to stress response.

Figure 6.

Heatmap of expression profiles of switchgrass TCP gene pairs in different tested tissues. The detailed microarray data were obtained from switchgrass gene atlas database (https://switchgrassgenomics.noble.org/). Clustering analysis was carried out using the online program pretty heatmap (http://www.ehbio.com/ImageGP/index.php/). The detailed information was listed in Table S3.

3.5. Gene Expression Response of PvTCPs under Salinity Condition

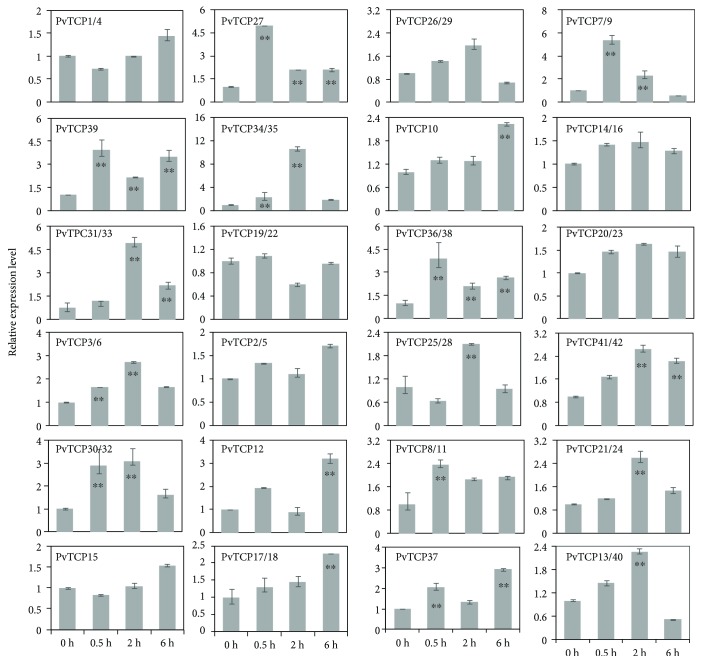

Based on the statistical results from cis-acting DNA elements, about 40% were showed to respond to environmental stress, especially to salinity (Table 3). To explore the expression profiles of PvTCPs under salinity condition, 42 PvTCPs were analyzed by qRT-PCR (Figure 7). 29 PvTCPs were regulated under salinity condition, and the other 13 PvTCPs were not statistically significant after 6 h salt stress (Figure 7). 14 out of 23 (about 60.8%) PvTCPs in clade PCF were upregulated during the 6 h salinity treatment. Of these genes, PvTCP27 and PvTCP39 were showed upregulated in all three treatment points. PvTCP3/6, PvTCP30/32, and PvTCP34/35 were upregulated at 0.5 h and exposed to salt stress for 2 h, and recovered to the normal expression level at 6 h treatment point. PvTCP10, PvTCP12, and PvTCP17/18 were upregulated at 6 h treatment point. PvTCP31/33 was induced after 2 h treatment. All PvTCPs in clade CYC/TB1 were upregulated. Similarly, nine out of 13 PvTCP genes in clade CIN were upregulated after 6 h treatment. These results showed that a large number of PvTCPs were response to salt stress and displayed different expression profiles when exposed to salinity condition.

Figure 7.

The expression of PvTCP genes in response to treatment with 250 mM NaCl for 0.5, 2, and 6 hours in seedlings. Control plants were collected before the treatment by NaCl solution. Error bars represented variability of three independent replicates. Statistically significant differences were assessed using Student's t-tests (∗∗represented p ≤ 0.01).

4. Discussion

The TCP gene family is a cluster of plant-specific transcription factors, which play pivotal roles in plant growth, development, and stress response [1]. In switchgrass, 42 TCP genes were identified from the genome and they were unevenly distributed on the chromosomes. The number of TCP genes in switchgrass is approximately twice that in Arabidopsis and rice, which have 24 and 21 TCP members, respectively [5]. No tandem repeats occurred in the evolutionary process in switchgrass TCP genes. So, large enrichment of switchgrass TCP genes was presumably due to the allotetraploid event. Furthermore, Ka/Ks analysis between the PvTCPs and OsTCPs was carried out, and the results that showed approximately 2/3 orthologous PvTCP genes, compared to OsTCP genes, are selected by natural selection pressure (Table 2), which might be due to the divergency between rice and switchgrass, at least 50 Mya [31]. As reported previously in PvC3H genes, the two sets of subgenomes of switchgrass originated from two closely diploid progenitors [31]. So, we speculated that PvTCP genes existed as paralogous gene pairs, which evolutionarily derived from the two sets of subgenomes, respectively. These results were also supported by previous studies in PvSPL genes and PvARF genes [32, 33].

The TCP gene family was classified into three clades, named as clade PCF, CYC/TB1, and CIN [5]. Similarly, PvTCP proteins were phylogenetically divided into those three clades in our study as well. Members that belonged to clade PCF have a four amino acid deletion in the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) conserved domain compared with clades CYC/TB1 and CIN (Figure 3). Exon/intron arrangement and motif location of PvTCP members were roughly conserved in the same clade but showed significant distinction among different clades (Figure 4). High similarity of the TCP members in switchgrass to other species, such as Arabidopsis and rice, suggested that TCP genes were highly conserved in plants, although there are great differences in gene numbers among different species [5]. Therefore, PvTCP genes would share similar functions with their orthologs in other species.

Previous reports about TCP roles mainly focused on cell cycle-mediated regulation of growth. TB1 is a major contributor to regulate apical dominance in maize [2]. PCF1 and PCF2 participate in DNA replication and repair, maintenance of chromatin structure, chromosome segregation, and cell-cycle progression by means of binding the promoter of the rice PROLIFERATING CELL NUCLEAR ANTIGEN (PCNA) gene, and CYC participates in the control of floral asymmetry in snapdragon [3, 4]. AtTCP4, a member in clade CIN, is critical in Arabidopsis floral organs [4]. Moreover, AtTCP4 can activate secondary cell wall biosynthesis and programmed cell death [22]. For those flower that predominantly expressed PvTCP genes in clade CIN, PvTCP37, PvTCP13/40, and PvTCP14/16, they may also take an important role in floral development, such as anther and pollen development. Not only the genes in clade CIN, but also the TCP genes belonged to clade CYC/TB1 can also control the floral asymmetry in Lotus japonicus (LjCYC2 and LjCYC3) and Pisum sativum (PsCYC2 and PsCYC3) [46, 47]. The expression levels of CYC/TB1 genes PvTCP8/11 were relatively high in flower, which may affect the flower shape. Additionally, five PCF clade genes (PvTCP1/4, PvTCP15, PvTCP27, and PvTCP39) were predominantly high in flower and stem, which indicated that they might have a special function in floral development and cell wall biosynthesis. The expression profiles in different tissues of the PvTCP genes can help us study the detailed functions during switchgrass growth and development accurately in the future.

Several studies on the relationship between TCP proteins and plant abiotic stress have been reported [24, 25]. In Agrostis stolonifera, miR319-targeted TCP genes can respond to salt and dehydration stress and Osa-miR319 overexpression transgenic creeping bentgrass improves salt and drought resistance [3]. AsTCP5 transcript increased after 0.5 h salinity stress and then decreased at 6 h treatment point [3]. OsTCP19 in shoots was upregulated under salt and drought stress in rice, and overexpression of OsTCP19 in Arabidopsis can improve the abiotic tolerance of the transgenic plants [2]. In our study, we firstly analyzed the cis-acting DNA elements of the PvTCPs' promoters. It is revealed that a lot of photosynthesis, plant hormone signaling, and organ development regulatory elements were accumulated, such as S000449, S000265, and S000454 (Table 3). In addition, about 40% of cis-acting DNA elements were related to biotic and abiotic stress response, especially to salt and drought stress, such as S000407, S000144, S000447, and S000174. Subsequently, the expression pattern of PvTCPs was tested in switchgrass seedling when exposed to 250 mM NaCl. As described here, 29 out of 42 PvTCPs showed a trend of regulation under salt treatment but seemed to follow the different response patterns. PvTCP17/18, the homologous gene of OsTCP19 in switchgrass, also can be induced under salinity condition, and their expression levels were nearly 2.3-fold higher than the control. Besides, about 69% of PvTCPs were response to salt stress, but the regulatory mechanism was not elucidated. Our study would provide great assistance for establishing the regulatory network about salt tolerance based on the transcription level in switchgrass.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we conducted a genome-wide analysis for the switchgrass TCP gene family to reveal their genome organization, phylogeny, gene structure, motif localization, function prediction, and expression profiles in different tissues and when exposed to salt treatment. A total of 42 TCP proteins were identified and phylogenetically divided into three clades; 29 of the PvTCP genes respond to salt treatment. It will provide us not only an insight of prediction and selection for TCP gene functions but also an information to exploit much more important gene resource for creating new germplasm in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31872879, 31601365, and 31601458).

Contributor Information

Zhenying Wu, Email: wu_zy@qibebt.ac.cn.

Zhen Sun, Email: sunzhen@dlpu.edu.cn.

Data Availability

No data were used to support this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Authors' Contributions

Yuzhu Huo, Zhenying Wu, and Zhen Sun conceived and designed the study. Yuzhu Huo, Wangdan Xiong, and Kunlong Su performed laboratory experiments and the data analysis. Yu Li, Yawen Yang, and Chunxiang Fu assisted in the data analysis. Yuzhu Huo and Wangdan Xiong wrote the manuscript with assistance from Zhenying Wu. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: ten conserved motifs in PvTCP analyzed by the MEME search tool. The height of each box represents the specific amino acid conservation in each motif.

Table S1: primers used in this study.

Table S2: list of TCP members used for phylogenetic relationship analysis.

Table S3: microarray data of PvTCP genes.

Table S4: the detailed information of cis-acting DNA elements of PvTCPs.

References

- 1.Doebley J., Stec A., Gustus C. Teosinte branched1 and the origin of maize: evidence for epistasis and the evolution of dominance. Genetics. 1995;141(1):333–346. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.1.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doebley J., Stec A., Hubbard L. The evolution of apical dominance in maize. Nature. 1997;386(6624):485–488. doi: 10.1038/386485a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luo D., Carpenter R., Vincent C., Copsey L., Coen E. Origin of floral asymmetry in Antirrhinum. Nature. 1996;383(6603):794–799. doi: 10.1038/383794a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosugi S., Ohashi Y. PCF1 and PCF2 specifically bind to cis elements in the rice proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene. The Plant Cell Online. 1997;9(9):1607–1619. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin-Trillo M., Cubas P. TCP genes: a family snapshot ten years later. Trends in Plant Science. 2010;15(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H., Wang H., Liu R., Xu Y., Lu Z., Zhou C. Genome-wide identification of TCP family transcription factors in Medicago truncatula reveals significant roles of miR319-targeted TCPs in nodule development. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2018;9:p. 774. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parapunova V., Busscher M., Busscher-Lange J., et al. Identification, cloning and characterization of the tomato TCP transcription factor family. BMC Plant Biology. 2014;14(1):p. 157. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao X., Ma H., Wang J., Zhang D. B. Genome-wide comparative analysis and expression pattern of TCP gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 2007;49(6):885–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2007.00509.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du J., Hu S., Yu Q., et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of BrrTCP transcription factors in Brassica rapa ssp. rapa . Frontiers in Plant Science. 2017;8:p. 1588. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma X., Ma J., Fan D., Li C., Jiang Y., Luo K. Genome-wide identification of TCP family transcription factors from Populus euphratica and their involvement in leaf shape regulation. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1, article 32795) doi: 10.1038/srep32795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navaud O., Dabos P., Carnus E., Tremousaygue D., Hervé C. TCP transcription factors predate the emergence of land plants. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2007;65(1):23–33. doi: 10.1007/s00239-006-0174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kosugi S., Ohashi Y. DNA binding and dimerization specificity and potential targets for the TCP protein family. The Plant Journal. 2002;30(3):337–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicolas M., Cubas P. TCP factors: new kids on the signaling block. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2016;33:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daviere J. M., Wild M., Regnault T., et al. Class I TCP-DELLA interactions in inflorescence shoot apex determine plant height. Current Biology. 2014;24(16):1923–1928. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Resentini F., Felipo-Benavent A., Colombo L., Blazquez M. A., Alabadi D., Masiero S. TCP14 and TCP15 mediate the promotion of seed germination by gibberellins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Molecular Plant. 2015;8(3):482–485. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lucero L. E., Uberti-Manassero N. G., Arce A. L., Colombatti F., Alemano S. G., Gonzalez D. H. TCP15 modulates cytokinin and auxin responses during gynoecium development in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal. 2015;84(2):267–282. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steiner E., Livne S., Kobinson-Katz T., et al. The putative O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase SPINDLY inhibits class I TCP proteolysis to promote sensitivity to cytokinin. Plant Physiology. 2016;171(2):1485–1494. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rueda-Romero P., Barrero-Sicilia C., Gomez-Cadenas A., Carbonero P., Onate-Sanchez L. Arabidopsis thaliana DOF6 negatively affects germination in non-after-ripened seeds and interacts with TCP14. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2012;63(5):1937–1949. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aguilar-Martinez J. A., Poza-Carrion C., Cubas P. Arabidopsis BRANCHED1 acts as an integrator of branching signals within axillary buds. The Plant Cell. 2007;19(2):458–472. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finlayson S. A. Arabidopsis TEOSINTE BRANCHED1-LIKE 1 regulates axillary bud outgrowth and is homologous to monocot TEOSINTE BRANCHED1. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2007;48(5):667–677. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J., Cheng X. L., Liu P., et al. MicroRNA319-regulated TCPs interact with FBHs and PFT1 to activate CO transcription and control flowering time in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genetics. 2017;13(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun X., Wang C., Xiang N., et al. Activation of secondary cell wall biosynthesis by miR319-targeted TCP4 transcription factor. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2017;15(10):1284–1294. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang S. T., Sun X. L., Hoshino Y., et al. MicroRNA319 positively regulates cold tolerance by targeting OsPCF6 and OsTCP21 in rice (Oryza sativa L.) PLoS One. 2014;9(3, article e91357) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou M., Li D., Li Z., et al. Constitutive expression of a miR319 gene alters plant development and enhances salt and drought tolerance in transgenic creeping bentgrass. Plant Physiology. 2013;161(3):1375–1391. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.208702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou M., Luo H. Role of microRNA319 in creeping bentgrass salinity and drought stress response. Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2014;9(4, article e28700) doi: 10.4161/psb.28700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ilhan E., Buyuk I., Inal B. Transcriptome-scale characterization of salt responsive bean TCP transcription factors. Gene. 2018;642:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLaughlin S. B., Kszos L. A. Development of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) as a bioenergy feedstock in the United States. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2005;28(6):515–535. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2004.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J. Y., Lee Y. C., Torres-Jerez I., et al. Development of an integrated transcript sequence database and a gene expression atlas for gene discovery and analysis in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) The Plant Journal. 2013;74(1):160–173. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xi Y. J., Fu C. X., Ge Y. X., et al. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of switchgrass and inheritance of the transgenes. Bioenergy Research. 2009;2(4):275–283. doi: 10.1007/s12155-009-9049-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rinerson C. I., Scully E. D., Palmer N. A., et al. The WRKY transcription factor family and senescence in switchgrass. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):p. 912. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan S. X., Xu B., Zhang J., et al. Comprehensive analysis of CCCH-type zinc finger family genes facilitates functional gene discovery and reflects recent allopolyploidization event in tetraploid switchgrass. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):p. 129. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1328-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Z. Y., Cao Y. P., Yang R. J., et al. Switchgrass SBP-box transcription factors PvSPL1 and 2 function redundantly to initiate side tillers and affect biomass yield of energy crop. Biotechnology for Biofuels. 2016;9(1) doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0516-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J., Wu Z., Shen Z., et al. Genome-wide identification, phylogeny, and expression analysis of ARF genes involved in vegetative organs development in switchgrass. International Journal of Genomics. 2018;2018:13. doi: 10.1155/2018/7658910.7658910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang C., Tang G., Peng X., Sun F., Liu S., Xi Y. Long non-coding RNAs of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) in multiple dehydration stresses. BMC Plant Biology. 2018;18(1):p. 79. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1288-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hivrale V., Zheng Y., Puli C. O. R., et al. Characterization of drought- and heat-responsive microRNAs in switchgrass. Plant Science. 2016;242:214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang C., Peng X., Guo X., et al. Transcriptional and physiological data reveal the dehydration memory behavior in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) Biotechnology for Biofuels. 2018;11(1):p. 91. doi: 10.1186/s13068-018-1088-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Voorrips R. E. MapChart: software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. The Journal of Heredity. 2002;93(1):77–78. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cannon S. B., Mitra A., Baumgarten A., Young N. D., May G. The roles of segmental and tandem gene duplication in the evolution of large gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biology. 2004;4(1):p. 10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeanmougin F., Thompson J. D., Gouy M., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal x. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1998;23(10):403–405. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo A. Y., Zhu Q. H., Chen X., Luo J. C. GSDS: a gene structure display server. Hereditas. 2007;29(8):1023–1026. doi: 10.1360/yc-007-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bailey T. L., Boden M., Buske F. A., et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37(Web Server):W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldman N., Yang Z. A codon-based model of nucleotide substitution for protein-coding DNA sequences. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1994;11(5):725–736. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hardin C. F., Fu C. X., Hisano H., et al. Standardization of switchgrass sample collection for cell wall and biomass trait analysis. Bioenergy Research. 2013;6(2):755–762. doi: 10.1007/s12155-012-9292-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore K. J., Moser L. E., Vogel K. P., Waller S. S., Johnson B. E., Pedersen J. F. Describing and quantifying growth stages of perennial forage grasses. Agronomy Journal. 1991;83(6):1073–1077. doi: 10.2134/agronj1991.00021962008300060027x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Z., Luo Y., Li X., et al. Genetic control of floral zygomorphy in pea (Pisum sativum L.) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(30):10414–10419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803291105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng X. Z., Zhao Z., Tian Z., et al. Control of petal shape and floral zygomorphy in Lotus japonicus . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(13):4970–4975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600681103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: ten conserved motifs in PvTCP analyzed by the MEME search tool. The height of each box represents the specific amino acid conservation in each motif.

Table S1: primers used in this study.

Table S2: list of TCP members used for phylogenetic relationship analysis.

Table S3: microarray data of PvTCP genes.

Table S4: the detailed information of cis-acting DNA elements of PvTCPs.

Data Availability Statement

No data were used to support this study.