Abstract

Background

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is an iatrogenic and potentially life threatening condition resulting from excessive ovarian stimulation. Reported incidence of moderate to severe OHSS ranges from 0.6% to 5% of in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles. The factors contributing to OHSS have not been completely explained. The release of vasoactive substances secreted by the ovaries under human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) stimulation may play a key role in triggering this syndrome. This condition is characterised by a massive shift of fluid from the intravascular compartment to the third space, resulting in profound intravascular depletion and haemoconcentration.

Objectives

To assess the effect of withholding gonadotrophins (coasting) on the prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in assisted reproduction cycles.

Search methods

For the update of this review, we searched the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group Trials Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE (PubMed), CINHAL, PsycINFO, Embase, Google, and clinicaltrials.gov to 6 July 2016.

Selection criteria

We included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in which coasting was used to prevent OHSS.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials and extracted data. They resolved disagreements by discussion. They contacted study authors to request additional information or missing data. The intervention comparisons were coasting versus no coasting, coasting versus early unilateral follicular aspiration (EUFA), coasting versus gonadotrophin releasing hormone antagonist (antagonist), coasting versus follicle stimulating hormone administration at the time of hCG trigger (FSH co‐trigger), and coasting versus cabergoline. We performed statistical analysis in accordance with Cochrane guidelines. Our primary outcomes were moderate or severe OHSS and live birth.

Main results

We included eight RCTs (702 women at high risk of developing OHSS). The quality of evidence was low or very low. The main limitations were failure to report live birth, risk of bias due to lack of information about study methods, and imprecision due to low event rates and lack of data. Four of the studies were published only as abstracts, and provided limited data.

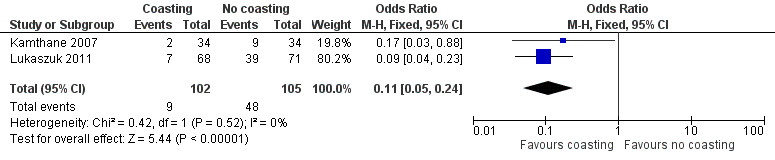

Coasting versus no coasting

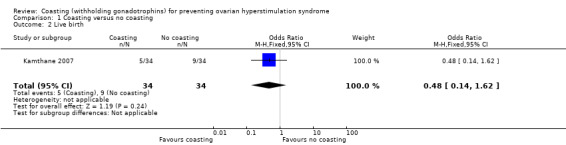

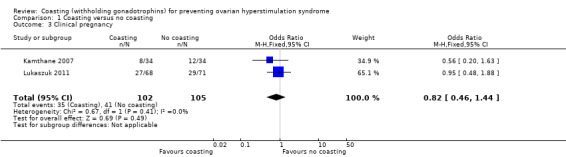

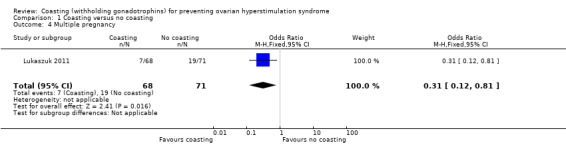

Rates of OHSS were lower in the coasting group (OR 0.11, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.24; I² = 0%, two RCTs; 207 women; low‐quality evidence), suggesting that if 45% of women developed moderate or severe OHSS without coasting, between 4% and 17% of women would develop it with coasting. There were too few data to determine whether there was a difference between the groups in rates of live birth (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.62; one RCT; 68 women; very low‐quality evidence), clinical pregnancy (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.44; I² = 0%; two RCTs; 207 women; low‐quality evidence), multiple pregnancy (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.81; one RCT; 139 women; low‐quality evidence), or miscarriage (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.86; I² = 0%; two RCTs; 207 women; very low‐quality evidence).

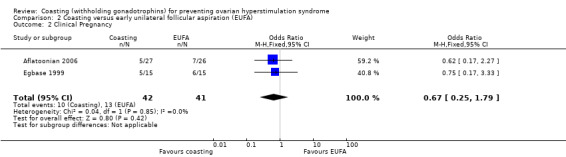

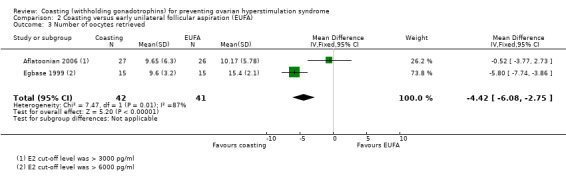

Coasting versus EUFA

There were too few data to determine whether there was a difference between the groups in rates of OHSS (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.34 to 2.85; I² = 0%; 2 RCTs; 83 women; very low‐quality evidence), or clinical pregnancy (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.79; I² = 0%; 2 RCTs; 83 women; very low‐quality evidence); no studies reported live birth, multiple pregnancy, or miscarriage.

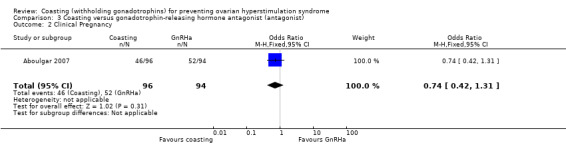

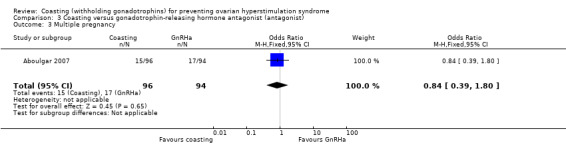

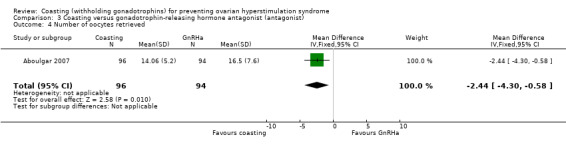

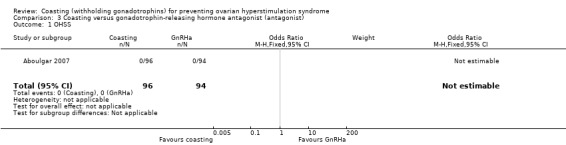

Coasting versus antagonist

One RCT (190 women) reported this comparison, and no events of OHSS occurred in either arm. There were too few data to determine whether there was a difference between the groups in clinical pregnancy rates (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.31; one RCT; 190 women; low‐quality evidence), or multiple pregnancy rates (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.43 to 2.32; one RCT; 98 women; very low‐quality evidence); the study did not report live birth or miscarriage.

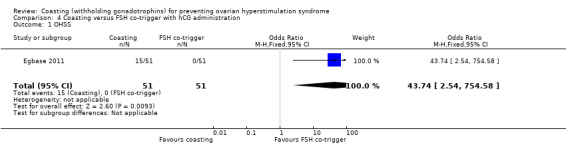

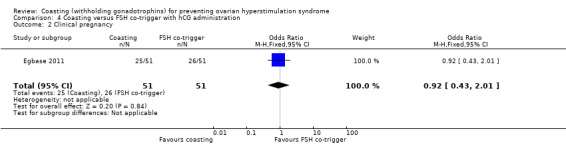

Coasting versus FSH co‐trigger

Rates of OHSS were higher in the coasting group (OR 43.74, 95% CI 2.54 to 754.58; one RCT; 102 women; very low‐quality evidence), with 15 events in the coasting arm and none in the FSH co‐trigger arm. There were too few data to determine whether there was a difference between the groups in clinical pregnancy rates (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.43 to 2.10; one RCT; 102 women; low‐quality evidence). This study did not report data suitable for analysis on live birth, multiple pregnancy, or miscarriage, but stated that there was no significant difference between the groups.

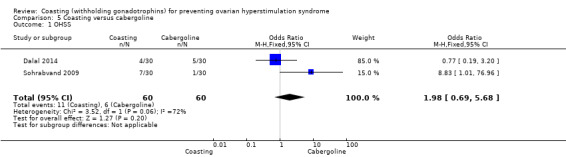

Coasting versus cabergoline

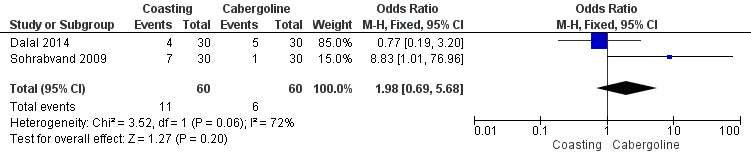

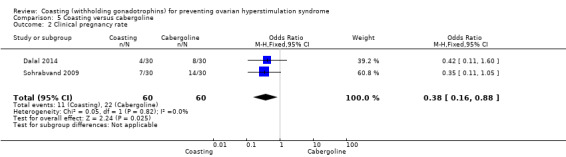

There were too few data to determine whether there was a difference between the groups in rates of OHSS (OR 1.98, 95% CI 0.09 to 5.68; P = 0.20; I² = 72%; two RCTs; 120 women; very low‐quality evidence), with 11 events in the coasting arm and six in the cabergoline arm. The evidence suggested that coasting was associated with lower rates of clinical pregnancy (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.88; P = 0.02; I² =0%; two RCTs; 120 women; very low‐quality evidence), but there were only 33 events altogether. These studies did not report data suitable for analysis on live birth, multiple pregnancy, or miscarriage.

Authors' conclusions

There was low‐quality evidence to suggest that coasting reduced rates of moderate or severe OHSS more than no coasting. There was no evidence to suggest that coasting was more beneficial than other interventions, except that there was very low‐quality evidence from a single small study to suggest that using FSH co‐trigger at the time of HCG administration may be better at reducing the risk of OHSS than coasting. There were too few data to determine clearly whether there was a difference between the groups for any other outcomes.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Chorionic Gonadotropin; Abortion, Spontaneous; Abortion, Spontaneous/epidemiology; Cabergoline; Ergolines; Fertilization in Vitro; Follicle Stimulating Hormone; Follicle Stimulating Hormone/administration & dosage; Follicle Stimulating Hormone/adverse effects; Gonadotropin‐Releasing Hormone; Gonadotropin‐Releasing Hormone/antagonists & inhibitors; Live Birth; Live Birth/epidemiology; Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome; Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome/epidemiology; Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome/etiology; Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome/prevention & control; Pregnancy Rate; Pregnancy, Multiple; Pregnancy, Multiple/statistics & numerical data; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Withholding Treatment

Plain language summary

Coasting (withholding gonadotrophins) to prevent ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

Review question

To assess the effect of withholding gonadotrophins (coasting) to prevent ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in assisted reproduction cycles.

Background

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is a complication of using hormones to induce ovulation (the release of eggs) in IVF (in vitro fertilization). The hormones can sometimes over stimulate the ovaries. Severe OHSS can be life threatening. One method used to try and reduce the risk of OHSS is 'coasting' or 'prolonged coasting'. This involves withholding one hormone (gonadotrophin) before ovulation.

Search Date

We included studies up to 6th of July 2016.

Study characteristics

Eight randomised controlled trials (702 women) were identified that compared withholding gonadotrophins (coasting) with another intervention to prevent ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. The other interventions included no coasting, early unilateral follicular aspiration (taking follicles from one ovary 10 to 12 hours after the administration of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG)), gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist (drugs that block the release of luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle‐stimulating hormone (FSH), and FSH co‐trigger (extra dose of FSH given at the same time as the hCG).

Key results

There was low‐quality evidence to suggest that coasting reduced rates of moderate or severe OHSS more than no coasting. There was no evidence to suggest that coasting was more beneficial than other interventions, except that there was very low‐quality evidence from a single small study to suggest that using FSH co‐trigger at the time of HCG administration may be better at reducing the risk of OHSS than coasting. There were too few data to determine clearly whether there was a difference between the groups for any other outcomes.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of evidence was low or very low. The main limitations were failure to report live birth, risk of bias due to lack of information about study methods, and imprecision due to low event rates and lack of data. Four of the studies were published only as abstracts, and provided limited data.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Coasting versus no coasting for prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.

| Coasting versus no coasting for prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) | ||||||

| Population: Women undergoing assisted reproduction Setting: Assisted reproduction clinics Intervention: Coasting Comparison: No coasting | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no coasting | Risk with coasting | |||||

| OHSS | 457 per 1000 | 85 per 1000 (40 to 168) | OR 0.11 (0.05 to 0.24) | 207 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,2 | |

| Live birth | 265 per 1000 | 147 per 1000 (48 to 368) | OR 0.48 (0.14 to 1.62) | 68 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW1,3 | |

| Clinical pregnancy | 390 per 1000 | 344 per 1000 (228 to 480) | OR 0.82 (0.46 to 1.44) | 207 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,2 | |

| Multiple pregnancy | 268 per 1000 | 102 per 1000 (42 to 228) | OR 0.31 (0.12 to 0.81) | 139 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ LOW1,2 | |

| Miscarriage | 57 per 1,000 | 49 per 1,000 (15 to 148) |

OR 0.85 (0.25 to 2.86) |

207 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ VERY LOW1,3 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the mean risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for serious risk of bias: one study did not clearly describe the methods used, studies not blinded

2 Downgraded one level for serious imprecision: few events, wide confidence intervals, or both

3 Downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision: very few events, very wide confidence intervals, or both

Summary of findings 2. Coasting versus early unilateral follicular aspiration for preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.

| Coasting versus early unilateral follicular aspiration for preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) | ||||||

| Population: Women undergoing assisted reproduction Setting: Assisted reproduction clinics Intervention: Coasting Comparison: Early unilateral follicular aspiration (EUFA) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with early unilateral follicular aspiration (EUFA) | Risk with coasting | |||||

| OHSS | 244 per 1000 | 240 per 1000 (99 to 479) | OR 0.98 (0.34 to 2.85) | 83 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW1,2 | |

| Live birth | No data available | |||||

| Clinical Pregnancy | 317 per 1000 | 237 per 1000 (104 to 454) | OR 0.67 (0.25 to 1.79) | 83 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW1,2 | |

| Multiple pregnancy | No data available | |||||

| Miscarriage | No data available | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the mean risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for serious risk of bias: one study did not clearly describe methods, lack of blinding

2 Downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision: very few events and very wide confidence intervals

Summary of findings 3. Coasting versus gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonist for preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.

| Coasting versus gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonist for preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) | ||||||

| Population: Women undergoing assisted reproduction Setting: Assisted reproduction clinics Intervention: Coasting Comparison: Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonist | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonist | Risk with coasting | |||||

| OHSS | Not estimable | Not estimable | not estimable | 190 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ VERY LOW1,2 | |

| Live birth | No data available | |||||

| Clinical Pregnancy | 553 per 1000 | 478 per 1000 (342 to 619) | OR 0.74 (0.42 to 1.31) | 190 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,3 | |

| Multiple pregnancy | 181 per 1000 | 156 per 1000 (79 to 284) | OR 0.84 (0.39 to 1.80) | 98 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ VERY LOW1,2 | |

| Miscarriage | No data available | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the mean risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level due to serious risk of bias: method of sequence generation not reported, lack of blinding

2 Downgraded two levels due to very serious imprecision: no OHSS occurred in either group. Few events for multiple pregnancy.

3 Downgraded one level due to serious imprecision. Wide confidence intervals, few events

Summary of findings 4. Coasting versus follicle stimulating hormone administration at time of hCG for preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.

| Coasting versus follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) administration at time of hCG trigger in preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) | ||||||

| Population: Women undergoing assisted reproduction Setting: Assisted reproduction clinics Intervention: Coasting Comparison: FSH co‐trigger with hCG administration | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with FSH co‐trigger with hCG administration | Risk with Coasting | |||||

| OHSS | Not estimable | Not estimable | OR 43.74 (2.54 to 754.58) | 102 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW1,2 | |

| Live birth | No data available | |||||

| Clinical Pregnancy | 510 per 1000 | 489 per 1000 (309 to 676) | OR 0.92 (0.43 to 2.01) | 102 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝1,3 LOW | |

| Multiple pregnancy | No data available | |||||

| Miscarriage | No data available | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the mean risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; hCG: human chorionic gonadotrophin | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level due to serious risk of bias: method of sequence generation not reported, lack of blinding

2 Downgraded two levels due to very serious imprecision: only 15 events, all in one arm.

3 Downgraded one level due to serious imprecision: very wide confidence intervals

Summary of findings 5. Coasting compared to cabergoline for preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.

| Coasting compared to cabergoline for preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) | ||||||

| Population: Women undergoing assisted reproduction Setting: Assisted reproduction clinics Intervention: Coasting Comparison: Cabergoline | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with cabergoline | Risk with Coasting | |||||

| OHSS | 100 per 1000 | 180 per 1000 (71 to 387) | OR 1.98 (0.69 to 5.68) | 120 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1,2 VERY LOW | |

| Live birth | Not reported | |||||

| Clinical pregnancy rate | 367 per 1000 | 180 per 1000 (85 to 338) | OR 0.38 (0.16 to 0.88) |

120 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝1 VERY LOW | |

| Multiple pregnancy | Not reported | |||||

| Miscarriage | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the mean risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels due to very serious risk of bias: one study did not clearly define method, method of sequence generation not reported, lack of blinding

2 Downgraded one level due to serious imprecision: very few events and/or wide confidence interval.

Background

Description of the condition

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is an iatrogenic, potentially life threatening condition resulting from excessive ovarian stimulation. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) noted that the incidence of OHSS is difficult to determine, as there is no consensus definition. Estimates of the incidence of moderate to severe OHSS range from 0.6% to 5% of assisted reproduction cycles (ASRM 2016; Calhaz‐Jorge 2016; Kawwass 2015). Studies of risk factors for OHSS have identified younger age, black race, ovulation, tubal factor, unexplained infertility, younger age, and possibly a lower body mass index (ASRM 2016).

In addition, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) or an ultrasonographic ovarian appearance of polycystic ovaries (presence of multiple, small follicles at the periphery of the ovary with echogenic stroma); establishment of pregnancy during assisted reproduction treatment (ART); human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) supplementation of the luteal phase; and high serum estradiol (E2; higher than 2500 pg/ml) were reported to be associated with OHSS.

Rabau and colleagues originally classified OHSS as mild, moderate or severe (Rabau 1967; Schenker 1978). Golan 1989 subsequently modified it by incorporating ultrasonographic measurement of the stimulated ovaries (Table 6). Navot 1992 introduced further modification by differentiating between the severe and the life threatening form of OHSS (Table 7). There was further classification from Rizk 1999 (Table 8).

1. Golan classification of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.

| Classification | Size of ovaries | Grade | Symptoms |

| Mild | 5 to 10 cm | grade 1 | abdominal tension and discomfort |

| grade 2 | grade 1 signs plus nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, or a combination | ||

| Moderate | > 10 cm | grade 3 | grade 2 signs plus ultrasound evidence of ascites |

| Severe | > 12 cm | grade 4 | grade 3 signs plus clinical evidence of ascites, pleural effusion and dyspnoea, or a combination |

| grade 5 | grade 4 signs plus haemoconcentration increased blood viscosity, hypovolaemia, decreased renal perfusion, oliguria |

2. Navot classification of severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.

| Severe | Critical |

| Variably enlarged ovary | Variably enlarged ovary |

| Massive ascites ± hydrothorax | Tense ascites ± hydrothorax |

| Hct > 45% (> 30% increment over baseline value) | Hct > 55% |

| WBC > 15,000 | WBC > 35,000 |

| Oliguria | |

| Creatinine 1.0 to 1.5 | Creatinine > 1.6 |

| Creatinine clearance > 50 ml/min | Creatinine clearance < 50ml/min |

| Liver dysfunction | Renal failure |

| Anasarca | Thromboembolic phenomena |

| Adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) |

3. Aboulghar and Rizk classification of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (1999).

| Moderate | Severe Grade A | Severe Grade B | Severe Grade C |

| Discomfort, pain, nausea, distension, ultrasonic evidence of ascites and enlarged ovaries, normal haematological and biological profile | Dyspnoea, oliguria, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, clinical evidence of ascites, marked distension of abdomen or hydro‐thorax, US showing large ovaries and marked ascites, normal biochemical profile | Grade A plus massive tension ascites, markedly enlarged ovaries, severe dyspnoea and marked oliguria, increased haematocrit, elevated serum creatinine and liver dysfunction | Complications such as respiratory distress syndrome, renal shut‐down, or venous thrombosis |

The factors leading to this syndrome have not been completely elucidated. It seems likely that the release of vasoactive substances, for example vascular endothelium growth factor (VEGF) secreted by the ovaries under hCG stimulation, play a key role in triggering this syndrome (Goldsman 1995; Tsirigotis 1994). As more follicles are recruited in response to gonadotrophin stimulation, the mass of the granulosa cells increases, while at the same time, the cells gain functional maturation. These two factors, acting synergistically, cause a concomitant increase in serum estradiol levels and vasoactive substances (as yet poorly defined (Agrawal 1999; Al‐Shawaf 2001)). This condition is characterised by a massive shift of fluid from the intra‐vascular compartment to the third space, resulting in profound intra‐vascular depletion and haemoconcentration (Rabau 1967; Schenker 1978).

Alternative strategies (embryo freezing, antagonist cycles, intravenous albumin infusion, agonist trigger, cabergoline) have been proposed for women undergoing ART who are at high risk of OHSS. Each of these strategies may reduce, but not eliminate, the risk.

Description of the intervention

Coasting, or prolonged coasting, may be defined as a process whereby: (1) gonadotrophin therapy is discontinued while administration of gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) is continued; (2) there is a delay, by a variable number of days, in administering hCG injection to trigger oocyte maturation prior to oocyte retrieval, until safe estradiol levels are attained (Sher 1993). Coasting should not be initiated too early, or too late. The effective duration of coasting is still to be determined. Many authors believe that each IVF centre should identify its own cut‐off limit of serum estradiol, follicle size, or both, at the onset of coasting, and hCG administration (Al‐Shawaf 2001; Waldenstrom 1999; Table 9).

4. Different coasting regimens.

| Authors | E2 at coasting | E2 at hCG | Number and follicle size | Coasting time |

| Sher 1995 | > 3000 pg/mL or > 11,000 pmol/L* | < 3000 pg/mL or < 11,000 pmol/L* | > 29 follicles at least 30% > 15 mm | 3 to 11 days (mean 6.1) |

| Benadiva 1997 | ≥ 3000 pg/ml or ≥ 11,000 pmol/l* | < 3000 pg/ml or < 11,000 pmol/l* | at least 3 follicles of 15.6 ± 1.4 mm | 1.9 ± 0.9 days |

| Tortoriello 1998 | > 3000 pg/ml or > 11,000 pmol/l* | < 3000 pg/mL or < 11,000 pmol/L* | 5 follicles at least 16 mm, two of which are at least 19 mm | 1 to 5 days |

| Dhont 1998 | > 2500 pg/ml or > 9000 pmol/l* | < 2500 pg/ml or < 9000 pmol/l* | ≥ 20 follicles > 15 mm | 1 to 6 days (mean 1.94) |

| Lee 1998 | > 2700 pg/ml or > 10,000 pmol/l* | no values given | many immature follicles < 3 at 18 mm | 3 days |

| VanderStraeten 1998 | > 2500 pg/ml or > 9000 pmol/l* | < 2500 pg/ml or < 9000 pmol/l* | ≥ 20 follicles > 14 mm | 1 to 6 days (mean 1.94) |

| Egbase 1999 | > 6000 pg/ml or > 22,000 pmol/l* | < 3000 pg/ml or 11,000 pmol/l* | > 15 follicles, each of > 18 mm in each ovary | 4.9 ± 1.6 days |

| Waldenstrom 1999 | > 2700 pg/ml or > 10,000 pmol/l* | < 2700 pg/ml or < 10,000 pmol/l* | > 25 follicles, at least 3 follicles > 17 mm | 3 to 6 days (mean 4.3) |

| Fluker 1999 | > 3000 pg/ml or > 11,000 pmol/l* | 25% decline < 2250 pg/ml or 8250 pmol/l* | > 3 follicles of > 18 mm | 3 to 5 days (mean 3.4 ± 0.1) |

| Al‐Shawaf 2001 | > 3600 pg/ml or > 13,000 pmol/l* | < 2700 pg/ml or < 10,000 pmol/l* | at least 25% of the follicles > 15 mm | 2 to 9 days (mean 3.4 ± 1.6) |

| Aboulghar 1998 | > 3000 pg/ml or > 11,000 pmol/l* | < 5500 pg/ml or < 20,000 pmol/l* | > 20 follicles at least 15 mm | 2.8 days |

| Ulug 2002 | > 4000 pg/ml or > 14,684 pmol/l* | < 4000 pg/ml or < 14,684 pmol/l* | > 20 follicles, at least 30% of them >15 mm | 2.9 ± 0.33 days |

| * conversion factor to SI unit, 3.671 |

It has also been postulated that follicles of varying size have a different threshold to gonadotrophins, and smaller follicles appear to be more susceptible to gonadotrophin deprivation than larger follicles (Fluker 1999). When coasting is initiated prior to 30% of follicles having attained a mean diameter of 15 mm, an abrupt arrest in follicular development and a rapid decline in plasma estradiol usually compromise the oocyte quality. But the quality of the oocytes is also compromised, and large cystic follicles are commonly encountered, if most of the follicles are larger than 15 mm in mean diameter when coasting is implemented (Sher 1995).

How the intervention might work

It was suggested that this approach prevents severe OHSS by removing the follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulation of granulosa cells, thereby inhibiting their proliferation and reducing the number of granulosa cells available for luteinization (Sher 1995). This would allow continued follicular growth and maturation, while reducing the risk of OHSS (Fluker 1999). Tortoriello 1998 also suggested that the falling FSH concentration induces an increased apoptosis of granulosa cells, which results in a reduction of chemical mediators or precursors that augment fluid extravasation.

Why it is important to do this review

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome is a potentially life threatening condition associated with super‐ovulation in ART. Coasting is a widespread practise, for which evidence is currently lacking. Therefore, it is important to establish, from the scientific literature, whether coasting can reduce the incidence of this condition.

Objectives

To assess the effect of withholding gonadotrophins (coasting) in the prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) in assisted reproduction cycles.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), in which coasting was used as a preventive strategy to reduce OHSS. We excluded cross‐over trials, and trials that explored ovulation induction treatment without in vitro fertilisation (IVF) or intra‐cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

Types of participants

Women of reproductive age, undergoing super‐ovulation in IVF or ICSI cycle

Types of interventions

Coasting is the withholding of gonadotrophins. A definition is provided under the Description of the intervention section of this report. Early unilateral follicular aspiration involves the aspiration of every visible follicle from one ovary between 10 to 12 hours after the administration of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG). We considered these comparisons:

Coasting versus no coasting;

Coasting versus early unilateral follicular aspiration;

Coasting versus gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonist

Coasting versus pure FSH co‐trigger;

Coasting versus cabergoline.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes of this systematic review were:

incidence of moderate or severe OHSS, as defined in the included studies;

live birth rate.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were:

clinical pregnancy rate per woman randomised, as defined in the included studies;

multiple pregnancy rate;

miscarriage rate;

number of oocytes retrieved.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases and trial registers (last searched 6 July 2016):

Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group Specialised Register (6 July 2016), Appendix 1

CENTRAL (inception to 6 July 2016), Appendix 2;

MEDLINE (2001 to 6 July 2016), Appendix 3;

Embase (2001 to 6 July 2016), Appendix 4.

CINAHL (2001 to 6 July 2016), Appendix 5

PsycINFO (2001 to 6 July 2016), Appendix 6

PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/; searched 6 July 2016)

Google (searched 6 July 2016)

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 6 July 2016)

We combined the MEDLINE search with the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials, from chapter 6 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We combined the Embase search with trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/filters.html#random).

Searching other resources

We handsearched the reference list of articles retrieved by the search, and contacted the trial authors if we required additional data. We handsearched relevant journals not included in the Cochrane register.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (NNA and ADA in the original review; ADA and JB in the 2011 update, and ADA and RH in the current (2017) update) scanned the titles and abstracts of the identified studies. They removed studies that were clearly irrelevant. For this update, ADA and RH retrieved the full texts of potentially relevant articles, and independently assessed them for inclusion. Disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Data extraction and management

The review authors (ADA and RH for this update) independently extracted data using forms designed according to Cochrane guidelines. Where studies had multiple publications, the main trial report was used as the reference, and additional details supplemented from the additional papers. We contacted authors of the original papers for additional information, if necessary. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The review authors independently assessed the included studies for risk of bias, using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool to assess: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, providers, and outcome assessors; completeness of outcome data, and selective outcome reporting. They resolved disagreements by consensus.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, we used the number of events in the control and intervention groups to calculate Mantel Haenszel odds ratios (OR), in a fixed‐effect model. For continuous data, we calculated mean differences (MD) between groups, in a fixed‐effect model. We reported the 95% confidence intervals (CI) with all treatment effects.

Unit of analysis issues

We presented data per woman randomised and not per cycle. We analyzed multiple pregnancy and miscarriage rate per woman (primary analysis) and also per pregnancy. We analyzed multiple pregnancy as one live birth.

Dealing with missing data

Where more than 20% of participants were lost to follow‐up or dropped out, we did not include the data in the meta‐analysis. Where data were missing, we contacted the original authors for further information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic (Higgins 2011). If the I² exceeded 50%, we deemed that there was substantial heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If eight or more original papers were identified, we had planned to produce a funnel plot, in an attempt to identify publication bias.

Data synthesis

For dichotomous data, we used the Mantel Haenszel method for the meta‐analysis, with a fixed‐effect model. For continuous data, we used the inverse variance method, with a fixed‐effect model.

We combined data in the following comparisons:

Coasting versus no treatment (no coasting)

Coasting versus other treatments (e.g. early unilateral follicular aspiration, antagonist, GnRHa, FSH co‐trigger, and cabergoline), each as a separate comparison.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not do any subgroup analyses. If heterogeneity had exceeded 50%, we would have conducted subgroup or sensitivity analysis, exploring clinical or methodological differences between the studies that might explain the data. When we were unable to satisfactorily explain heterogeneity, we deemed the data unsuitable to include in the meta‐analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

When heterogeneity was high (over 50%), we had planned to conduct sensitivity analysis, based on the quality of the included studies as indicated in the 'Risk of bias' table, and whether the data were from a full paper or conference proceedings. Had there been sufficient studies, we would have conducted sensitivity analyses, even if heterogeneity was not high.

Overall quality of the body of evidence: Summary of findings table

We prepared 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADEpro software and Cochrane methods (GRADEpro GDT 2014; Higgins 2011). These tables summarized the overall quality of the body of evidence for the main review outcomes (OHSS, live birth, clinical pregnancy, adverse effects), using five GRADE criteria (study limitations (i.e. risk of bias), consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias). For each outcome, we justified, documented, and incorporated into the reporting of the results, our judgements about the quality of the evidence quality (high, moderate, low, or very low).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

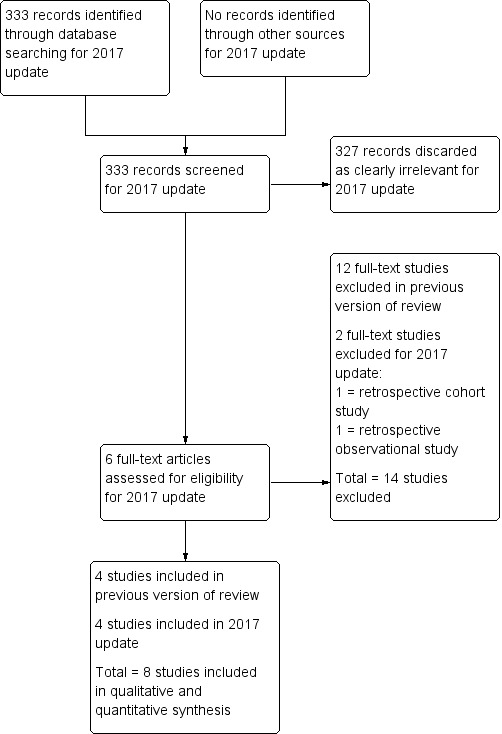

In the search conducted in 2016, we identified and assessed the full text of six potentially eligible studies. We excluded two studies and included four. The updated review now includes eight studies; 14 studies have been excluded. See the Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables and the PRISMA study‐flow chart Figure 1 for details.

1.

Study flow diagram: July 2016 search for 2017 review update

Included studies

Design

Eight RCTs, with 702 women, met the inclusion criteria (Aboulgar 2007; Aflatoonian 2006; Dalal 2014; Egbase 1999; Egbase 2011; Kamthane 2007; Lukaszuk 2011; Sohrabvand 2009). They were conducted in Egypt, Iran, India, Kuwait, Poland, and the UK. Aboulgar 2007, Egbase 1999, Lukaszuk 2011, and Sohrabvand 2009 were full publications, the other four were only reported in conference abstracts.

Participants

All eight trials included women at high risk of developing OHSS. Egbase 2011 defined this as 15 or more follicles in each ovary, E2 of at least 3500 pg/ml, and two leading follicles with at least an 18 mm diameter. Lukaszuk 2011 defined this as women who had unsuccessfully undergone a previous long protocol and ICSI procedure, complicated by moderate or severe OHSS. Aboulgar 2007 defined it as at least 20 follicles in both ovaries, 90% of which had less than a 14 mm mean diameter, and E2 of at least 3000 pg/ml. Aflatoonian 2006 used the same criteria, although they did not define the mean diameter of follicles. Kamthane 2007 defined women at risk of OHSS as having follicles larger than 10 mm in diameter, or E2 higher than 700 pg/ml on day 7 or day 8. Egbase 1999 defined risk for OHSS as an E2 threshold of 6000 pg/ml. Sohrabvand 2009 included women with at least 20 follicles in both ovaries, the majority of which had diameters less than14 mm, and a serum E2 level of 3000 pg/ml. Dalal 2014 included women with at least 20 follicles of more than 11 mm, E2 levels higher than 300ng/ml on day 9 of stimulation, or both.

Interventions

Kamthane 2007 and Lukaszuk 2011 compared coasting with no coasting; Aflatoonian 2006 and Egbase 1999 compared coasting with early unilateral follicular aspiration; Aboulgar 2007 compared coasting with antagonist administration; and Egbase 2011 compared coasting with FSH administration at the time of hCG trigger (FSH co‐trigger). Sohrabvand 2009 and Dalal 2014 compared coasting with cabergoline.

Outcomes

For our primary outcomes, all the included studies reported OHSS rates, but only one reported data suitable for analysis on live birth (Kamthane 2007). For our secondary outcomes, all trials reported clinical pregnancy, three reported multiple pregnancy (Aboulgar 2007; Egbase 2011; Lukaszuk 2011), three reported miscarriage (Egbase 2011; Kamthane 2007; Lukaszuk 2011), and all reported the number of oocytes retrieved.

Excluded studies

Fourteen studies were excluded. One was randomised but the control was matched retrospectively (Aboulghar 1998) . The other 13 studies were excluded because they were not randomised. Four were prospective observational studies (Al‐Shawaf 2001; Lee 1998; Sher 1995; Waldenstrom 1999). Six were retrospective observational studies (Benadiva 1997; Esinler 2013; Fluker 1999; Herrero 2011; Tortoriello 1998; Tortoriello 1999; Ulug 2002). Two studies were retrospective case‐control studies (Dhont 1998; VanderStraeten 1998).

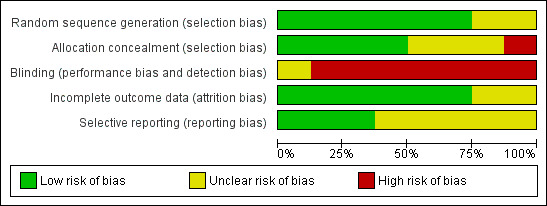

Risk of bias in included studies

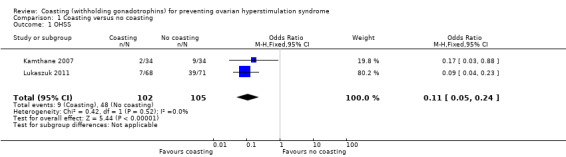

See the 'Characteristics of included studies' table for details, and Figure 2 and Figure 3 for summaries.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Egbase 1999 and Egbase 2011 reported using computer generated random allocation to the intervention groups. Sohrabvand 2009 reported using block randomization. Dalal 2014 reported using a randomization software (www.randomizer.org). There were no details on the method of randomization in the other studies.

Dalal 2014, Aboulgar 2007, and Egbase 1999 provided adequate information on allocation concealment. No details were provided by Aflatoonian 2006, Kamthane 2007, Sohrabvand 2009. or Egbase 2011.

Blinding

None of the included studies reported on blinding. Blinding of investigators and women is not possible in these interventions, which are based on timing. Outcome assessors could have been blinded to allocation of intervention.

Incomplete outcome data

All randomised participants were included in the data analyses reported by Dalal 2014, Egbase 2011, Lukaszuk 2011, Sohrabvand 2009, Aboulgar 2007, and Egbase 1999. There were no details provided by Aflatoonian 2006 or Kamthane 2007.

Selective reporting

Dalal 2014 and Aflatoonian 2006 were reported in conference abstracts, and did not report outcomes a priori. Kamthane 2007 and Egbase 2011 summarized the a priori outcomes in their conference abstracts. There was no evidence in the literature of a full paper publication for these four studies. None of the studies except Kamthane 2007 reported live birth, but they were rated as at unclear risk of selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

There were no other sources of bias that were identified.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5

'Summary of findings' tables for comparisons with usable data can be referred to in Table 1, Table 3, Table 2, and Table 4.

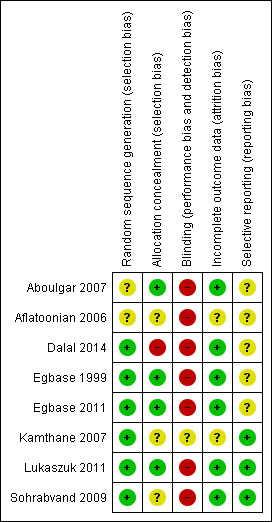

1. Coasting versus no coasting

Two trials compared coasting (N = 102) with no coasting (N = 105 (Kamthane 2007; Lukaszuk 2011)).

Primary outcomes

1.1 Moderate or severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS)

There were fewer cases of moderate or severe OHSS in the coasting group than in the no coasting group (OR 0.11, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.24; 2 RCTs; 207 women; I2 = 0%; low quality evidence; P < 0.00001; Analysis 1.1). Refer to Figure 4.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Coasting versus no coasting, Outcome 1 OHSS.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Coasting versus no coasting, outcome: 3.1 OHSS.

1.2 Live birth

One trial reported on live birth (Kamthane 2007). It was unclear whether there was any difference between coasting and no coasting for this outcome (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.62; 68 women; very low quality evidence; P = 0.24; Analysis 1.2). Refer to Figure 5.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Coasting versus no coasting, Outcome 2 Live birth.

Secondary outcomes

1.3 Clinical pregnancy

Two trials reported on the rate of clinical pregnancy (Kamthane 2007; Lukaszuk 2011). It was unclear whether there was any difference between the groups (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.44; 2 RCTs; 207 women; I2 = 0%; low quality evidence; P = 0.49; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Coasting versus no coasting, Outcome 3 Clinical pregnancy.

1.4 Multiple pregnancy

One trial reported on the rate of multiple pregnancy (Lukaszuk 2011). The evidence suggested fewer multiple pregnancies per woman in the coasting group (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.81, 139 women, low quality evidence, P = 0.02; Analysis 1.4). This finding persisted when the data were analyzed per pregnancy (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.58; 56 women).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Coasting versus no coasting, Outcome 4 Multiple pregnancy.

1.5 Miscarriage

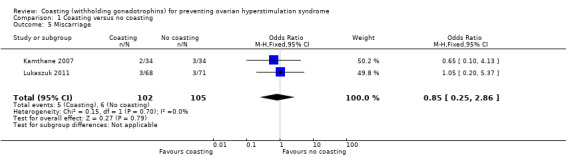

Both trials reported this outcome. It was unclear whether there was any difference between the groups in the rate of miscarriage per woman (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.86, 2 RCTs, 207 women, very low quality evidence, Analysis 1.5). This finding persisted when the data were analyzed per pregnancy (OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.28 to 3.88.; 2 RCTs; 207 women; I2 = 0%).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Coasting versus no coasting, Outcome 5 Miscarriage.

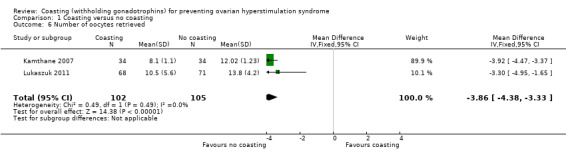

1.6 Number of oocytes retrieved

Both trials reported on the number of oocytes retrieved. The evidence suggested that fewer oocytes were retrieved in women undergoing coasting than no coasting (MD ‐3.86, 95% CI ‐4.38 to ‐333; 2 RCTs; 76 women; I2 = 0%; low quality evidence; P < 0.00001; Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Coasting versus no coasting, Outcome 6 Number of oocytes retrieved.

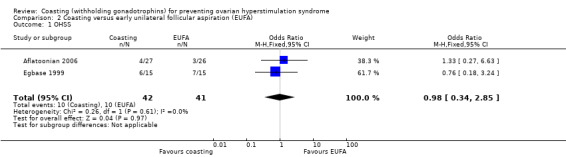

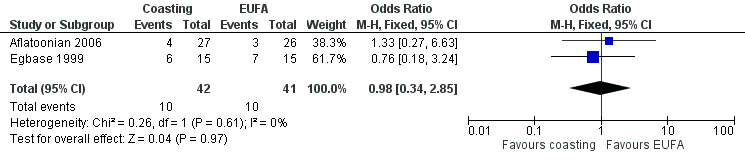

2. Coasting versus early unilateral follicular aspiration

Two studies compared coasting (N = 42) with early unilateral follicular aspiration (N = 41 (Aflatoonian 2006; Egbase 1999)).

Primary outcomes

2.1 Moderate or severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS)

It was unclear whether there was any difference between the groups (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.34 to 2.85; 2 RCTs; 83 women; I2 = 0%; very low quality evidence; P = 0.97; I² = 0%; Analysis 2.1). Refer Figure 5.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Coasting versus early unilateral follicular aspiration (EUFA), Outcome 1 OHSS.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Coasting versus EUFA, outcome: 1.1 OHSS.

2.2 Live birth

No data suitable for analysis were reported by either trial. The authors of one trial stated that there was no significant difference between the groups (Egbase 2011).

Secondary outcomes

2.3 Clinical pregnancy

It was unclear whether there was any difference between the groups (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.79; 2 RCTs; 83 women; I2 = 0%; very low quality evidence; P = 0.42; I² = 0%; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Coasting versus early unilateral follicular aspiration (EUFA), Outcome 2 Clinical Pregnancy.

2.4 Multiple pregnancy

This outcome was not reported by either trial.

2.5 Miscarriage

This outcome was not reported by either trial.

2.6 Number of oocytes retrieved

Both trials reported this outcome. Heterogeneity was evident (I² = 87%). The heterogeneity may be due to the differences in the cut‐off for oestrogen levels in the definition of high risk for OHSS. Aflatoonian 2006 used a cut‐off level of > 3000 pg/ml E2 and Egbase 1999 used a cut‐off level of > 6000 pg/ml E2.

3. Coasting versus gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonist (antagonist)

One trial compared coasting with antagonist (Aboulgar 2007).

Primary outcomes

3.1 Moderate or severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS)

There were no instances of OHSS in either group (N = 190).

3.2 Live birth

Live birth was not reported in this trial.

Secondary outcomes

3.3 Clinical pregnancy

It was unclear whether there was any difference between the groups (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.31; 190 women; low quality evidence; P = 0.31; Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Coasting versus gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonist (antagonist), Outcome 2 Clinical Pregnancy.

3.4 Multiple pregnancy

It was unclear whether there was any difference between the groups in the rate of multiple pregnancy per woman (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.80; 190 women; very low quality evidence; P = 0.65; Analysis 3.3). This finding persisted when the data were analyzed per pregnancy (OR 1.0; 95% CI 0.43 to 2.32; 98 women).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Coasting versus gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonist (antagonist), Outcome 3 Multiple pregnancy.

3.5 Miscarriage

Miscarriage was not reported in this trial.

3.6 Number of oocytes retrieved

The evidence suggested that there were fewer oocytes retrieved in the group receiving coasting (MD ‐2.44, 95% CI 4.30 to ‐0.58; 190 women; P = 0.01; Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Coasting versus early unilateral follicular aspiration (EUFA), Outcome 3 Number of oocytes retrieved.

4. Coasting versus follicle stimulating hormone co‐trigger

One trial compared coasting versus FSH administration at the time of hCG trigger (N = 102; Egbase 2011).

Primary outcomes

4.1 Moderate or severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS)

Fifteen cases of moderate or severe OHSS occurred, all in the coasting group (OR 43.74, 95% CI 2.54 to 754.58; 102 women; very low quality evidence; P = 0.009; Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Coasting versus FSH co‐trigger with hCG administration, Outcome 1 OHSS.

4.2 Live Birth

The authors reported that there was no evidence of a difference between the groups for this outcome (data not available).

Secondary outcomes

4.3 Clinical Pregnancy

It was unclear whether there was a difference between the groups (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.43 to 2.01; 102 women; low quality evidence; P = 0.84; Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Coasting versus FSH co‐trigger with hCG administration, Outcome 2 Clinical pregnancy.

4.4 Multiple Pregnancy

The trial authors reported that there was no evidence of a difference between the groups for this outcome (data not available).

4.5 Miscarriage

The trial authors reported that there was no evidence of a difference between the groups for this outcome (data not available).

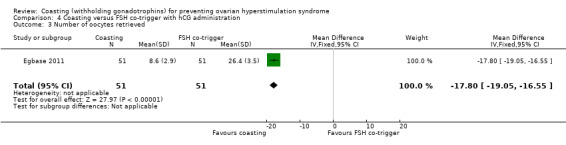

4.6 Number of oocytes retrieved

The evidence suggested that fewer oocytes were retrieved in women undergoing coasting than FSH co‐trigger (MD ‐17.80, 95% CI ‐19.05 to ‐16.55; 102 women; P < 0.00001; Analysis 3.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Coasting versus gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonist (antagonist), Outcome 4 Number of oocytes retrieved.

5. Coasting versus cabergoline

Two trials compared coasting versus cabergoline (N = 120 (Dalal 2014; Sohrabvand 2009)).

Primary outcomes

5.1 Moderate or severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS)

There was insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference between the two groups (OR 1.98, 95% CI 0.09 to 5.68; 120 women; I² = 72%; very low quality evidence; P=0.20, Analysis 5.1). Refer to Figure 6. Heterogeneity was high (72%) and there is no reason to explain this heterogeneity.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Coasting versus cabergoline, Outcome 1 OHSS.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 5 Coasting versus cabergoline, outcome: 5.1 OHSS.

5.2 Live Birth

Live birth rates were not reported in these trials.

Secondary outcomes

5.3 Clinical Pregnancy

There was evidence of a difference in clinical pregnancy favouring the cabergoline group compared to the coasting group (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.88; 2 RCTs; 120 women; very low quality evidence; P = 0.02; I² = 0%; Analysis 5.2).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Coasting versus cabergoline, Outcome 2 Clinical pregnancy rate.

5.4 Multiple Pregnancy

Multiple pregnancy rates were not reported in these trials.

5.5 Miscarriage

Miscarriage rates were not reported in these trials.

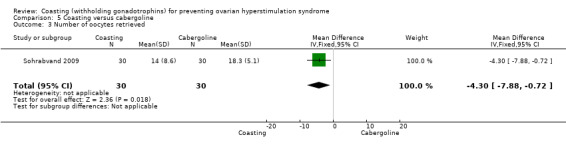

5.6 Number of oocytes retrieved

In one trial (Sohrabvand 2009) the evidence suggested that fewer oocytes were retrieved in women undergoing coasting than cabergoline (MD ‐4.3, 95% CI 7.88 to ‐0.72; 60 women; P 0.02; Analysis 5.4). The authors of one trial (Dalal 2014) stated that there was significant difference between the groups but no data were provided.

Other analyses

There were insufficient data to conduct planned sensitivity analyses or to construct a funnel plot.

Discussion

Summary of main results

There was low‐quality evidence to suggest that coasting reduced moderate or severe OHSS more than no coasting. There was very low‐quality evidence suggesting that using FSH co‐trigger prevented moderate and severe OHSS better than coasting, but the evidence was derived from only one small trial. There was no clear evidence of any difference in the rate of moderate or severe OHSS or in the achievement of clinical pregnancy when coasting was compared with early unilateral follicular aspiration (very low‐quality evidence), GnRH antagonist (low or very low quality evidence), or cabergoline (low or very low‐quality evidence). Nor was there evidence to suggest a benefit in live birth from coasting compared with no coasting, although the data were from a single trial only. It was difficult to draw any conclusions about the number of oocytes obtained due to the statistical heterogeneity of the studies. Nor was there any clear evidence of differences between the groups in clinical pregnancy, multiple pregnancies, live births or miscarriage rates.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Only eight randomised trials were identified, and four of these were conference abstracts that never became full publications. The completeness and applicability of the data were substantially limited by this factor. Authors were contacted, but did not respond directly, and some missing data were obtained from another Cochrane review. Only one of the trials reported data suitable for analysis on the outcome of live birth. There may be additional interventions that have not been compared yet with coasting, in a randomised controlled trial.

Quality of the evidence

The overall quality of the evidence was low or very low. The main limitations were failure to report live birth, risk of bias due to lack of information about study methods, and imprecision due to low event rates and lack of data. Four of the studies were published only as abstracts, with limited data and no evidence of full publication (Aflatoonian 2006; Dalal 2014; Egbase 2011; Kamthane 2007). Three to four years is longer than expected to publish a full paper. With the exception of the number of oocytes retrieved, the statistical heterogeneity between studies was acceptable. The inclusion criteria and OHSS classification used varied between the studies.

Potential biases in the review process

The authors attempted to identify all potential studies using a variety of methods. One of the main biases, as mentioned above, is that several of the trials were only published as conference abstracts. There may be other relevant data which were not reported. Therefore, the results of the review must be interpreted with caution.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

In some excluded studies, the higher the oestrogen level at the beginning of coasting, the less effective the intervention was at preventing OHSS, regardless of the duration of the coasting period (see Aboulghar 1998; Dhont 1998; Fluker 1999; Lee 1998; Sher 1995; Waldenstrom 1999). The inclusion criterion for this review was oestrogen levels higher than 2500 pg/ml. The four included trials used a cut‐off of 3000 pg/ml, and this may, in part, explain the lack of effect.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There was low‐quality evidence to suggest a benefit to using coasting rather than no coasting, to reduce rates of moderate or severe OHSS. Evidence did not suggest that coasting was more beneficial than other interventions such as early unilateral follicular aspiration, gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonist or cabergoline. There was very low‐quality evidence from a single small study to suggest that using FSH co‐trigger at the time of HCG administration may be better at reducing the risk of OHSS than coasting. There were too few data to determine clearly whether there was a difference between the groups for any other outcomes. Therefore, at present, clinicians may wish to employ other strategies for preventing OHSS rather than just coasting, until further evidence has accumulated.

Implications for research.

Given the current practice of "freeze all" and the use of antagonist protocols with agonist trigger, further research into coasting may not be relevant.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13 June 2017 | Review declared as stable | We have made this a stable review as further evidence is unlikely to change its conclusions. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2000 Review first published: Issue 3, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 May 2017 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | The addition of 4 new studies has led to a change in our conclusions. |

| 6 July 2016 | New search has been performed | Literature search updated, four additional trials included (Dalal 2014; Egbase 2011; Lukaszuk 2011; Sohrabvand 2009) |

| 23 December 2010 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Citation order changed |

| 19 July 2010 | New search has been performed | Search updated, two additional trials identified |

| 25 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 28 February 2005 | New search has been performed | Search updated; no new studies identified |

| 11 May 2002 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group editorial office staff for their advice and support through the review process.

We thank also Dr Julie Brown for her contributions to previous versions of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CGF specialised register search strategy

From inception until 6 July 2016

Keywords CONTAINS "superovulation" or "superovulation induction" or "ovarian hyperstimulation" or "ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome" or "ovarian stimulation syndrome" or "*Ovulation Induction"or"OHSS" or Title CONTAINS "IVF" or "superovulation" or "superovulation induction" or "ovarian hyperstimulation" or "ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome" or"OHSS" or "ovarian stimulation syndrome" or "*Ovulation Induction"

AND

Keywords CONTAINS "coasting" or "reduced dose" or Title CONTAINS "coasting" or "reduced dose" (17 hits)

Appendix 2. CENTRAL search strategy

Database: EBM Reviews ‐ Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (OVID platform)

From inception until 6 July 2016

1 exp fertilization in vitro/ or exp sperm injections, intracytoplasmic/ or exp ovulation induction/ or exp superovulation/ (2137) 2 (in vitro fertili#ation or IVF).tw. (3100) 3 (intracytoplasmic sperm injection$ or ICSI).tw. (1143) 4 (ov$ induc$ or ovar$ stimulat$).tw. (1511) 5 superovulation.tw. (141) 6 OHSS.tw. (223) 7 Ovar$ hyperstimulat$.tw. (693) 8 exp Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome/ (142) 9 or/1‐8 (4860) 10 (coasting or coast).tw. (221) 11 (reduc$ adj5 gonadotrophin$).tw. (33) 12 (reduc$ adj5 gonadotropin$).tw. (70) 13 (withdraw$ adj5 gonadotropin$).tw. (7) 14 (withhold$ adj5 gonadotrophin$).tw. (2) 15 (withhold$ adj5 gonadotropin$).tw. (0) 16 (withdraw$ adj5 gonadotrophin$).tw. (2) 17 (Taper$ adj5 (gonadotrophin$ or gonadotropin$)).tw. (0) 18 ((reduc$ or withdraw$ or withhold$ or taper$) adj5 GnRH).tw. (125) 19 or/10‐18 (441) 20 9 and 19 (99)

Appendix 3. MEDLINE search strategy

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1950 to 6 July 2016>

Search Strategy:

1 exp fertilization in vitro/ or exp sperm injections, intracytoplasmic/ or exp ovulation induction/ or exp superovulation/ (36459) 2 (in vitro fertili#ation or IVF).tw. (26556) 3 (intracytoplasmic sperm injection$ or ICSI).tw. (7729) 4 (ov$ induc$ or ovar$ stimulat$).tw. (14368) 5 superovulation.tw. (1743) 6 OHSS.tw. (1274) 7 Ovar$ hyperstimulat$.tw. (4127) 8 exp Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome/ (1861) 9 or/1‐8 (55478) 10 (coasting or coast).tw. (17689) 11 (reduc$ adj5 gonadotrophin$).tw. (199) 12 (reduc$ adj5 gonadotropin$).tw. (624) 13 (withdraw$ adj5 gonadotropin$).tw. (58) 14 (withhold$ adj5 gonadotrophin$).tw. (22) 15 (withhold$ adj5 gonadotropin$).tw. (17) 16 (withdraw$ adj5 gonadotrophin$).tw. (36) 17 (Taper$ adj5 (gonadotrophin$ or gonadotropin$)).tw. (1) 18 ((reduc$ or withdraw$ or withhold$ or taper$) adj5 GnRH).tw. (1071) 19 or/10‐18 (19579) 20 9 and 19 (379) 21 randomised controlled trial.pt. (406339) 22 controlled clinical trial.pt. (91305) 23 randomized.ab. (329363) 24 placebo.tw. (171267) 25 clinical trials as topic.sh. (177494) 26 randomly.ab. (237642) 27 trial.ti. (144959) 28 (crossover or cross‐over or cross over).tw. (65362) 29 or/21‐28 (1009451) 30 (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. (3990166) 31 29 not 30 (930198) 32 20 and 31 (81)

Appendix 4. Embase search strategy

From inception until 6 July 2016 (Ovid platform)

1 exp fertilization in vitro/ or exp sperm injections, intracytoplasmic/ or exp ovulation induction/ or exp superovulation/ (55935) 2 (in vitro fertili#ation or IVF).tw. (36892) 3 (intracytoplasmic sperm injection$ or ICSI).tw. (12480) 4 (ov$ induc$ or ovar$ stimulat$).tw. (19154) 5 superovulation.tw. (1896) 6 OHSS.tw. (2064) 7 Ovar$ hyperstimulat$.tw. (5646) 8 exp Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome/ (6868) 9 or/1‐8 (77862) 10 coasting.tw. (276) 11 (reduc$ adj3 gonadotrophin$).tw. (126) 12 (reduc$ adj3 gonadotropin$).tw. (373) 13 (withdrawal adj3 gonadotropin$).tw. (48) 14 (withhold$ adj3 gonadotrophin$).tw. (24) 15 (withhold$ adj3 gonadotropin$).tw. (18) 16 (withdrawal adj3 gonadotrophin$).tw. (21) 17 (Taper$ adj5 (gonadotrophin$ or gonadotropin$)).tw. (1) 18 ((reduc$ or withdraw$ or withhold$ or taper$) adj5 GnRH).tw. (1210) 19 or/10‐18 (1994) 20 9 and 19 (428) 21 Clinical Trial/ (847849) 22 Randomized Controlled Trial/ (377981) 23 exp randomization/ (67354) 24 Single Blind Procedure/ (20623) 25 Double Blind Procedure/ (122094) 26 Crossover Procedure/ (43745) 27 Placebo/ (260138) 28 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (120388) 29 Rct.tw. (17651) 30 random allocation.tw. (1431) 31 randomly allocated.tw. (22837) 32 allocated randomly.tw. (2036) 33 randomly divided.tw. (46545) 34 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (731) 35 Single blind$.tw. (16081) 36 Double blind$.tw. (152770) 37 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (462) 38 placebo$.tw. (217599) 39 prospective study/ (299537) 40 or/21‐39 (1514455) 41 case study/ (32879) 42 case report.tw. (286546) 43 abstract report/ or letter/ (931036) 44 or/41‐43 (1244071) 45 40 not 44 (1474939) 46 20 and 45 (119)

Appendix 5. CINAHL search strategy

From inception until 6 July 2016 (EBSCO platform)

| # | Query | Results |

| S18 | S11 AND S17 | 17 |

| S17 | S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 | 52 |

| S16 | TX ((reduc* or withdraw* or withhold* or taper*) N5 GnRH*) | 19 |

| S15 | TX withhold* N3 gonadotrop?in* | 1 |

| S14 | TX (reduc* N3 gonadotropin*) | 14 |

| S13 | TX (reduc* N3 gonadotrophin*) | 2 |

| S12 | TX coasting | 18 |

| S11 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 | 6,214 |

| S10 | (MM "Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome") | 137 |

| S9 | TX Ovar* hyperstimulat* | 341 |

| S8 | TX OHSS | 77 |

| S7 | TX superovulation | 18 |

| S6 | TX (ov* induc* or ovar* stimulat*) | 3,094 |

| S5 | TX (IVF or ICSI) | 1,296 |

| S4 | TX (intracytoplasmic sperm injection) | 245 |

| S3 | TX (in vitro fertili#ation) | 2,970 |

| S2 | (MM "Ovulation Induction") | 240 |

| S1 | (MM "Fertilization in Vitro") | 1,494 |

Appendix 6. PsycINFO search strategy

From inception until 6 July 2016

1 exp reproductive technology/ (1466) 2 (in vitro fertili?ation or IVF).tw. (676) 3 (intracytoplasmic sperm injection$ or ICSI).tw. (68) 4 OHSS.tw. (6) 5 Ovar$ hyperstimulat$.tw. (10) 6 or/1‐5 (1714) 7 coasting.tw. (34) 8 (reduc$ adj3 gonadotrophin$).tw. (3) 9 (reduc$ adj3 gonadotropin$).tw. (15) 10 (withdrawal adj3 gonadotropin$).tw. (1) 11 (withhold$ adj3 gonadotrophin$).tw. (0) 12 (withhold$ adj3 gonadotropin$).tw. (0) 13 (withdrawal adj3 gonadotrophin$).tw. (0) 14 or/7‐13 (53) 15 6 and 14 (0)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Coasting versus no coasting.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 OHSS | 2 | 207 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.05, 0.24] |

| 2 Live birth | 1 | 68 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.14, 1.62] |

| 3 Clinical pregnancy | 2 | 207 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.46, 1.44] |

| 4 Multiple pregnancy | 1 | 139 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.12, 0.81] |

| 5 Miscarriage | 2 | 207 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.25, 2.86] |

| 6 Number of oocytes retrieved | 2 | 207 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.86 [‐4.38, ‐3.33] |

Comparison 2. Coasting versus early unilateral follicular aspiration (EUFA).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 OHSS | 2 | 83 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.34, 2.85] |

| 2 Clinical Pregnancy | 2 | 83 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.25, 1.79] |

| 3 Number of oocytes retrieved | 2 | 83 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.42 [‐6.08, ‐2.75] |

Comparison 3. Coasting versus gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonist (antagonist).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 OHSS | 1 | 190 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Clinical Pregnancy | 1 | 190 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.42, 1.31] |

| 3 Multiple pregnancy | 1 | 190 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.39, 1.80] |

| 4 Number of oocytes retrieved | 1 | 190 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.44 [‐4.30, ‐0.58] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Coasting versus gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonist (antagonist), Outcome 1 OHSS.

Comparison 4. Coasting versus FSH co‐trigger with hCG administration.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 OHSS | 1 | 102 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 43.74 [2.54, 754.58] |

| 2 Clinical pregnancy | 1 | 102 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.43, 2.01] |

| 3 Number of oocytes retrieved | 1 | 102 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐17.80 [‐19.05, ‐16.55] |

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Coasting versus FSH co‐trigger with hCG administration, Outcome 3 Number of oocytes retrieved.

Comparison 5. Coasting versus cabergoline.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 OHSS | 2 | 120 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.98 [0.69, 5.68] |

| 2 Clinical pregnancy rate | 2 | 120 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.16, 0.88] |

| 3 Number of oocytes retrieved | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.30 [‐7.88, ‐0.72] |

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Coasting versus cabergoline, Outcome 3 Number of oocytes retrieved.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Aboulgar 2007.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial, single centre. | |

| Participants | Eygpt. IVF centre. Of 1536 women undergoing IVF/ICSI, 190 were eligible and randomised. Inclusion: undergoing first IVF trial, at actual risk of developing severe OHSS with large number of follicles (≥ 20) on both ovaries, with 90% of the follicles being small (< 14 mm in mean diameter), and estradiol concentration ≥ 3000 pg/ml. Age in the coasting group was 30 ± 4.9 years, and in the antagonist group was 29.6 ± 4.6 years |

|

| Interventions | Ovarian stimulation using long GnRH agonist down‐regulation protocol. Coasting group (N = 96) hMG injections stopped and GnRH agonist continued. HmCG given when E2 ≤ 3000 pg/ml. Oocyte retrieval performed 36 hours after HCG administration. GnRHa group (N = 94) treated with subcutaneous GnRH antagonist (ganirelix acetate 250 µg) daily until day of HCG administration. GnRH agonist was discontinued with the start of antagonist and hMG injections continued daily until E2 ≤ 3000 pg/ml, then 10,000 IU of hCG given. Oocyte retrieval performed 36 hours after HCG administration. Embryo transfer on day 2 or day 3 with two to three embryos transferred. |

|

| Outcomes | The primary outcomes were number of high quality embryos. Secondary outcomes were days of intervention, number of oocytes, pregnancy rate, multiple pregnancy, number of cryopreserved embryos and incidence of severe OHSS | |

| Notes | Sample size calculation estimated N = 182 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | 'randomised' ‐ no other details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | 'dark, sealed envelopes .... created by a third party not involved in the allocation process.' 'sequentially numbered' |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | 'The patient was informed about the allocated arm' |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All those randomised were analyzed, no loss to follow‐up reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Did not report live birth |

Aflatoonian 2006.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Iran and UK study 52 women undergoing IVF treatment cycles at high risk for developing OHSS (> 20 follicles in both ovaries, serum estradiol = E2 > 3000 pg/ml). |

|

| Interventions | Induction of ovulation with long protocol beginning with pituitary desensitisation with subcutaneous buserelin and followed by hMG 3 amp from day 2. On day 9 randomised to: Coasting group (N = 27) IVF/ICSI defined as presence of > 10 follicles per ovary with a leading follicle > 17 mm and E2 > 3000 pg/ml (maximum 3 days). Then 10000 units hCG administered and oocyte retrieval 34 to 36 hours later. Aspiration follicle group (N = 26) had > 15 follicles 15 to 16mm in each ovary and E2 > 3000 pg/ml. Unilateral aspiration follicular aspiration performed before hCG administration. Oocyte retrieval performed 34 to 36 hours later in the other ovary. Embryo transfer was done 2 days later in both groups. |

|

| Outcomes | Number of follicles, number of oocytes, pregnancy rate, OHSS. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | 'randomized controlled trial' |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No details |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Outcomes not mentioned in methods ‐ this was a conference abstract. Did not report live birth. |

Dalal 2014.

| Methods | Randomised control trial | |

| Participants | India study 60 women undergoing IVF considered at risk of OHSS (> 20 follicles of more than 11 mm, serum E2 > 3000 pg/ml on day 9 of stimulation, or both). |

|

| Interventions | Coasting group (30 patients), exogenous gonadotropins were withheld to allow E2 to decrease while GnRH‐a was maintained. Then 10,000 units hCG was administrated and oocyte retrieval was performed 36 hours later Cabergoline group (30 patients) were administered with 0.5 mg cabergoline tablet on day of hCG injection, continued for 8 days. |

|

| Outcomes | Number of mature oocytes, number of embryos, clinical pregnancy rate, OHSS | |

| Notes | Source of funding not stated and no correspondence details for author. Obtained missing data from another review | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer generated randomization |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No allocation concealment |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants analyzed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Outcomes not mentioned in methods. Did not report live birth |

Egbase 1999.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial; parallel prospective design; single centre; power calculation included; randomization based on serially numbered sealed envelopes. | |

| Participants | Kuwait study 37 women recruited: 30 infertile women (consented and randomised) < 39 years, considered at risk of OHSS (15 coasting/15 EUFA); E2 (major risk factor for OHSS) was > 6000 pg/ml; Mean (± SD) age (coasting) 33.5 ± 2.8, (EUFA) 34.6 ± 3.2; Duration of infertility: not stated; Causes of infertility: unexplained (2 versus 2); anovulation (2 versus 2); tubal factor (1 versus 3); tubal + anovulation (2 versus 2); male factor (5 versus 4); male factor + anovulation (5 versus 4); BMI > 30 (13 versus 10) and > 40 (6 versus 5). |

|

| Interventions | Treatment group: coasting (hMG injections were withheld until E2 < 3000 pg/ml and GnRh‐a continued until day of hCG; duration 3 to 7 days). Control group: early unilateral follicular flushing (left ovarian follicular aspiration 10 to 12 hours after hCG administration). | |

| Outcomes | Method of diagnosing different grades of OHSS: Schenker and Weinstein (1978) and Navot criteria (1992). Moderate and severe OHSS Clinical pregnancy rate/woman Number of oocytes retrieved Fertilization rate Number of embryos transferred | |

| Notes | Source of funding: not stated. Authors contacted on two occasions ‐ extra data obtained | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "serially numbered sealed envelopes" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All patients analyzed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Outcomes not mentioned in methods. Did not report live birth |

Egbase 2011.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial, single centre, randomization based on serially numbered sealed envelopes. | |

| Participants | Kuwait study, 102 women recruited undergoing IVF cycles at risk of OHS with serum E2 ≥ 3500 pg/ml, > 15 follicles in each ovary and two leading follicles of ≥18mm in size. | |

| Interventions | Coasting group (N = 51): long protocol starting dose 225 iu hMG, hMG was withheld until E2 levels fell < 1500 pg/ml, when trigger dose HCG was administered. FSH co‐trigger group (N = 51): Long protocol, pure FSH was administered with the trigger dose of hCG, regardless of the E2 levels ≥ 3500 pg/ml. Three cleaved D3 or two D5 blastocyst embryos transferred. |

|

| Outcomes | Golan 2009 classification of OHSS used Moderate or severe OHSS Clinical pregnancy rate (48.6% versus 51.8%) Number of oocytes retrieved (8.6 ± 2.9 versus 26.4 ± 3.5) Multiple pregnancy rate, live birth rate, miscarriage rate (reported as no significant difference) |

|

| Notes | Source of funding not stated, author contacted twice, responded once with partial data. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "serially numbered sealed envelopes" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants analyzed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Outcomes not mentioned in methods. Did not report data suitable for analysis on live birth |

Kamthane 2007.

| Methods | Randomised study | |

| Participants | 68 patients at risk of developing OHSS, aged 25 to 38 years undergoing controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in IVF/ICSI. Inclusion: intermediate follicles (11 to 14mm) > 10, E2 > 700 pg/ml on day 7 or day 8 of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation, or both |

|

| Interventions | Group A (N = 16) early coasting from day 8 onwards on basis of high E2 (> 700 pg/ml). Group B (N = 18) late coasting when one of the follicles reached 15 mm; E2 < 700 pg/ml on day 8 but number of intermediate follicles were more than 10. Group C (N = 34) no coasting, E2 level of 3000 pg/ml to < 4000 pg/ml hCG day. These women had neither E2 > 700 pg/ml, nor intermediate follicles > 10mm. |

|

| Outcomes | OHSS severity, terminal E2 mean number of oocytes retrieved, endometrial thickness, clinical pregnancy, miscarriage, live birth. | |

| Notes | Women with E2 > 4000 pg/ml on hCG day had transvaginal ovum retrieval, and following fertilisation, the embryos were frozen and not transferred in that cycle. These women received prophylactic IV albumin and were excluded from the study. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | 'randomised' |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No details |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Women who were excluded due to high E2 levels were not detailed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All a priori outcomes reported |

Lukaszuk 2011.