Abstract

Background

Diabetic macular oedema (DMO) is a common complication of diabetic retinopathy. Antiangiogenic therapy with anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor (anti‐VEGF) modalities can reduce oedema and thereby improve vision and prevent further visual loss. These drugs have replaced laser photocoagulation as the standard of care for people with DMO.

Objectives

The 2014 update of this review found high‐quality evidence of benefit with antiangiogenic therapy with anti‐VEGF modalities, compared to laser photocoagulation, for the treatment of DMO.The objective of this updated review is to compare the effectiveness and safety of the different anti‐VEGF drugs in preserving and improving vision and quality of life using network meta‐analysis methods.

Search methods

We searched various electronic databases on 26 April 2017.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared any anti‐angiogenic drug with an anti‐VEGF mechanism of action versus another anti‐VEGF drug, another treatment, sham or no treatment in people with DMO.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane methods for pair‐wise meta‐analysis and we augmented this evidence using network meta‐analysis methods. We focused on the relative efficacy and safety of the three most commonly used drugs as interventions of direct interest for practice: aflibercept and ranibizumab, used on‐label; and off‐label bevacizumab.

We collected data on three efficacy outcomes (gain of 15 or more Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) letters; mean change in best‐corrected visual acuity (BCVA); mean change in central retinal thickness (CRT)), three safety outcomes (all severe systemic adverse events (SSAEs); all‐cause death; arterial thromboembolic events) and quality of life.

We used Stata 'network' meta‐analysis package for all analyses. We investigated the risk of bias of mixed comparisons based on the variance contribution of each study, having assigned an overall risk of bias to each study.

Main results

Twenty‐four studies included 6007 participants with DMO and moderate vision loss, of which two studies randomised 265 eyes of 230 participants and one was a cross‐over study on 56 participants (62 eyes) that was treated as a parallel‐arm trial. Data were collected on drugs of direct interest from three studies on aflibercept (975 eyes), eight studies on bevacizumab (515 eyes), and 14 studies on ranibizumab (1518 eyes). As treatments of indirect interest or legacy treatment we included three studies on pegaptanib (541 eyes), five studies on ranibizumab plus prompt laser (557 eyes), one study on ranibizumab plus deferred laser (188 eyes), 13 studies on laser photocoagulation (936 eyes) and six studies on sham treatment (793 eyes).

Aflibercept, bevacizumab and ranibizumab were all more effective than laser for improving vision by 3 or more lines after one year (high‐certainty evidence). Approximately one in 10 people improve vision with laser, and about three in 10 people improve with anti‐VEGF treatment: risk ratio (RR) versus laser 3.66 (95% confidence interval (CI) 2.79 to 4.79) for aflibercept; RR 2.47 (95% CI 1.81 to 3.37) for bevacizumab; RR 2.76 (95% CI 2.12 to 3.59) for ranibizumab. On average there was no change in visual acuity (VA) with laser after one year, compared with a gain of 1 or 2 lines with anti‐VEGF treatment: laser versus aflibercept mean difference (MD) −0.20 (95% CI −0.22 to −0.17) logMAR; versus bevacizumab MD −0.12 (95% CI −0.15 to −0.09) logMAR; versus ranibizumab MD −0.12 (95% CI −0.14 to −0.10) logMAR. The certainty of the evidence was high for the comparison of aflibercept and ranibizumab with laser and moderate for bevacizumab comparison with laser due to inconsistency between the indirect and direct evidence.

People receiving ranibizumab were less likely to gain 3 or more lines of VA at one year compared with aflibercept: RR 0.75 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.94), moderate‐certainty evidence. For every 1000 people treated with aflibercept, 92 fewer would gain 3 or more lines of VA at one year if treated with ranibizumab (22 to 148 fewer). On average people receiving ranibizumab had worse VA at one year (MD 0.08 logMAR units, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.11), moderate‐certainty evidence; and higher CRT (MD 39 µm, 95% CI 2 µm to 76 µm; low‐certainty evidence). Ranibizumab and bevacizumab were comparable with respect to aflibercept and did not differ in terms of VA: RR of gain of 3 or more lines of VA at one year 1.11 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.43), moderate‐certainty evidence, and difference in change in VA was 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.03) logMAR, moderate‐certainty evidence. CRT reduction favoured ranibizumab by −29 µm (95% CI −58 µm to −1 µm, low‐certainty evidence). There was no evidence of overall statistical inconsistency in our analyses.

The previous version of this review found moderate‐certainty evidence of good safety of antiangiogenic drugs versus control. This update used data at the longest available follow‐up (one or two years) and found that aflibercept, ranibizumab and bevacizumab do not differ regarding systemic serious adverse events (SSAEs) (moderate‐ or high‐certainty evidence). However, risk of bias was variable, loop inconsistency could be found and estimates were not precise enough on relative safety regarding less frequent events such as arterial thromboembolic events or death (low‐ or very low‐certainty evidence).

Two‐year data were available and reported in only four RCTs in this review. Most industry‐sponsored studies were open‐label after one year. One large publicly‐funded study compared the three drugs at two years and found no difference.

Authors' conclusions

Anti‐VEGF drugs are effective at improving vision in people with DMO with three to four in every 10 people likely to experience an improvement of 3 or more lines VA at one year. There is moderate‐certainty evidence that aflibercept confers some advantage over ranibizumab and bevacizumab in people with DMO at one year in visual and anatomic terms. Relative effects among anti‐VEGF drugs at two years are less well known, since most studies were short term. Evidence from RCTs may not apply to real‐world practice, where people in need of antiangiogenic treatment are often under‐treated and under‐monitored.

We found no signals of differences in overall safety between the three antiangiogenic drugs that are currently available to treat DMO, but our estimates are imprecise for cardiovascular events and death.

Keywords: Humans; Angiogenesis Inhibitors; Angiogenesis Inhibitors/therapeutic use; Antibodies, Monoclonal; Antibodies, Monoclonal/therapeutic use; Antibodies, Monoclonal, Humanized; Antibodies, Monoclonal, Humanized/therapeutic use; Aptamers, Nucleotide; Aptamers, Nucleotide/therapeutic use; Bevacizumab; Diabetic Retinopathy; Diabetic Retinopathy/complications; Laser Coagulation; Laser Coagulation/methods; Macular Edema; Macular Edema/drug therapy; Macular Edema/surgery; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Ranibizumab; Receptors, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; Receptors, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor/therapeutic use; Recombinant Fusion Proteins; Recombinant Fusion Proteins/therapeutic use; Triamcinolone; Triamcinolone/therapeutic use; Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A; Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A/antagonists & inhibitors

Anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor (anti‐VEGF) drugs for diabetic macular oedema

What is the aim of this review? The aim of this Cochrane Review was to find out which is the best type of anti‐VEGF drug for diabetic macular oedema (DMO). Cochrane researchers collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question and found 24 studies.

Key messages Anti‐VEGF drugs given by injection into the eye improve vision in people with diabetic macular oedema as compared to no average improvement with laser photocoagulation. One of these drugs, aflibercept, probably works slightly better after one year. There did not appear to be important harms from any of these drugs.

What was studied in the review? The light‐sensitive tissue at the back of the eye is known as the retina. The central area of the retina is called the macula. People with diabetes can develop problems in the retina, known as retinopathy. Some people with diabetic retinopathy can also develop oedema (swelling or thickening) at the macula. DMO is a common complication of diabetic retinopathy and can lead to visual loss.

One type of treatment for DMO is anti‐VEGF. This drug is given by means of an injection into the eye. It can reduce the swelling at the back of the eye and prevent visual loss. There are three main types of anti‐VEGF drugs in use: aflibercept (EyeleaTM), bevacizumab (Avastin) and ranibizumab (LucentisTM). Only aflibercept and ranibizumab have received marketing authorisation for the treatment of DMO. All three drugs are used to prevent visual loss and improve vision. They do this by slowing down the growth of new blood vessels and thereby reducing the swelling at the back of the eye. They may have adverse effects, particularly related to effects on blood vessels in the rest of the body. These effects may include stroke and heart attack.

What are the main results of the review? Cochrane researchers found 24 relevant studies. Fourteen of these studies were industry‐sponsored studies from USA, Europe or Asia. Ten studies were independent of industry funding and were from USA, Europe, Middle East and South America.

These studies investigated ranibizumab, bevacizumab and aflibercept. These anti‐VEGF drugs were compared with no treatment, placebo treatment, laser treatment, or each other. The drugs were given every month, every two months, as needed or 'treat and extend', which means that the time period between treatments is extended if the condition has stabilised. Decisions about re‐treating were based on visual acuity or by looking at the back of the eye.

The review reveals the following results.

• All three anti‐VEGF drugs prevent visual loss and improve vision in people with DMO (high‐certainty evidence).

• People receiving ranibizumab were probably slightly less likely to improve vision compared with aflibercept at one year after the start of treatment (moderate‐certainty evidence). Approximately three in 10 people improve vision by 3 or more lines with ranibizumab and one in 10 additional people can achieve this with aflibercept.

• People receiving ranibizumab and bevacizumab probably have a similar visual outcome at one year after the start of treatment (moderate‐certainty evidence).

• Aflibercept, ranibizumab and bevacizumab are similar for common and serious systemic harms (such as any disease leading to hospitalisation, disability or death) (moderate‐ or high‐certainty evidence) but is less certain for arterial thromboembolic events (mainly stroke, myocardial infarction and vascular death) and death of any cause (very low‐certainty evidence).

How up to date is this review? Cochrane researchers searched for studies that had been published up to 26 April 2017.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Antiangiogenic therapy versus control

| Antiangiogenic therapy versus control | |||||

| Patient or population: people with diabetic macular oedema Settings: ophthalmology clinics Interventions: laser photocoagulation, aflibercept, bevacizumab, ranibizumab | |||||

| Outcomes | Assumed risk* | Corresponding risk and relative risk** (95% CI) , mixed evidence | Certainty of evidence and reason for downgrading | ||

| Laser photocoagulation | Aflibercept | Bevacizumab | Ranibizumab | ||

| Gain 3+ lines of visual acuity at 1 year | 100 per 1000 |

366 per 1000 (279 to 479) RR: 3.66 (2.79 to 4.79) |

247 per 1000 (181 to 337) RR: 2.47 (1.81 to 3.37) |

276 per 1000 (212 to 359) RR: 2.76 (2.12 to 3.59) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

|

Visual acuity change at 1 year Measured on the logMAR scale, range −0.3 to 1.3. Higher values represent worse visual acuity. |

On average visual acuity improved by −0.01 logMAR units in the laser group between the start of treatment and 1 year (effectively no change) | Average change in visual acuity was −0.20 (−0.22 to −0.17) logMAR units better with aflibercept compared with laser photocoagulation | Average change in visual acuity was −0.12 (−0.15 to −0.09) logMAR units better with bevacizumab compared with laser photocoagulation | Average change in visual acuity was −0.12 (−0.14 to −0.10) logMAR units better with ranibizumab compared with laser photocoagulation | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high for aflibercept and ranibizumab ⊕⊕⊕ moderate for bevacizumab (−1 for inconsistency of indirect versus direct evidence) |

|

Central retinal thickness μm (CRT) change at 1 year The aim of treatment is to reduce central retinal thickness so thinner is better. |

On average CRT changed by −64 μm in the laser group between the start of treatment and 1 year (became thinner) | Average change in CRT was −114 (−147 to −81) μm more (thinner) with aflibercept compared with laser photocoagulation | Average change in CRT was −46 (−78 to −14) μm more (thinner)with bevacizumab compared with laser photocoagulation | Average change in CRT was −75 (−100 to −50) μm more (thinner) with ranibizumab compared with laser photocoagulation | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

|

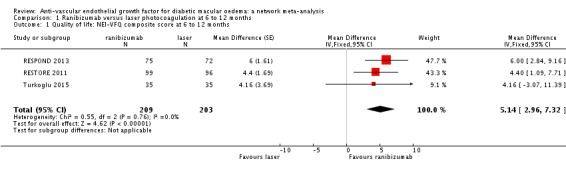

Quality of life: NEI‐VFQ composite score at 6 to 12 months An improvement by 5 units is clinically significant. |

On average the composite score improved by +2 units in the laser group between the start of treatment and 6 to 12 months | Average change in composite score was 5.14 (2.96 to 7.32) with ranibizumab compared with laser photocoagulation | ⊕⊕⊕ moderate (−1 for risk of bias) | ||

| All serious systemic adverse events at 1 to 2 years | 200 per 1000 |

196 per 1000 (166 to 232) RR: 0.98 (0.83 to 1.16) |

186 per 1000 (146 to 238) RR: 0.93 (0.73 to 1.19) |

194 per 1000 (160 to 234) RR: 0.97 (0.80 to 1.17) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Arterial thromboembolic events at 1 to 2 years | 45 per 1000 |

38 per 1000 (16 to 94) RR: 0.88 (0.37 to 2.13) |

41 per 1000 (15 to 117) RR: 0.94 (0.33 to 2.66) |

48 per 1000 (23 to 101) RR: 1.09 (0.52 to 2.29) |

⊕⊕ low (−2 for imprecise estimates) |

| Death at 1 to 2 years | 20 per 1000 |

20 per 1000 (7 to 61) RR: 1.01 (0.34 to 3.03) a |

32 per 1000 (9 to 114) RR: 1.61 (0.45 to 5.69) |

18 per 1000 (8 to 40) RR: 0.90 (0.40 to 2.01) |

⊕⊕ low for bevacizumab and aflibercept (−2 for imprecise estimates) ⊕ very low for aflibercept (additional −1 direct evidence inconsistent, higher risk) |

| The assumed risk in the laser group was estimated as the row sum of the events divided by the row sum of the participants (eyes) for dichotomous variables, and as the (unweighted) median change of visual acuity or central retina thickness. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ** The risk ratio was estimated from mixed (direct and indirect) comparisons. CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate‐certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low‐certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low‐certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

Summary of findings 2.

Ranibizumab versus aflibercept for diabetic macular oedema

| Ranibizumab versus aflibercept for diabetic macular oedema | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with diabetic macular oedema Settings: ophthalmology clinics Interventions: aflibercept, ranibizumab | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI), mixed evidence** | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Reason for downgrading certainty of evidence | ||

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Aflibercept | Ranibizumab | |||||

| Gain 3+ lines of visual acuity at 1 year | 370 per 1000 | 278 per 1000 (222 to 348) | RR: 0.75 (0.60 to 0.94) | ⊕⊕⊕ moderate | −1 for imprecision as confidence intervals include both clinically important and clinically unimportant effects | |

|

Visual acuity change at 1 year Measured on the logMAR scale, range −1.3 to 1.3. Higher values represent worse visual acuity. |

On average visual acuity improved by−0.23 logMAR units in the aflibercept group between the start of treatment and 1 year | Average change in visual acuity was 0.08 (0.05 to 0.11) logMAR units worse with ranibizumab compared with aflibercept |

⊕⊕⊕ moderate | −1 for imprecision as confidence intervals include both clinically important and clinically unimportant effects | ||

|

Central retinal thickness μm (CRT) change at 1 year The aim of treatment is to reduce central macular thickness so thinner is better. |

On average CRT changed by −181 μm in the aflibercept group between the start of treatment and 1 year (became thinner) | Average change in CRT was 39 (2 to 76) μm more (thicker) with ranibizumab compared with aflibercept |

⊕⊕ low | −1 for high heterogeneity in two direct comparisons and large predictive intervals −1 for imprecision |

||

| Quality of life at 1 year | No data available. | |||||

| All serious systemic adverse events at 1 to 2 years | 345 per 1000 |

338 per 1000 (283 to 411) |

RR 0.98 (0.82 to 1.19) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| Arterial thromboembolic events at 1 to 2 years | 60 per 1000 |

74 per 1000 (29 to 191) |

RR 1.24 (0.48 to 3.19) |

⊕ very low | Inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence (−1), and imprecise estimates (−2) | |

| Death at 1 to 2 years | 30 per 1000 |

35 per 1000 (11 to 108) |

RR 1.16 (0.38 to 3.58) |

⊕ very low | Inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence (−1), and imprecise estimates (−2) | |

| The assumed risk in the aflibercept group was estimated as the row sum of the events divided by the row sum of the participants (eyes) for dichotomous variables, and as the (unweighted) median change of visual acuity or central retina thickness. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ** The risk ratio was estimated from mixed (direct and indirect) comparisons. CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. |

||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate‐certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low‐certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low‐certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Summary of findings 3.

Ranibizumab versus bevacizumab for diabetic macular oedema

| Ranibizumab versus bevacizumab for diabetic macular oedema | |||||

| Patient or population: people with diabetic macular oedema Settings: ophthalmology clinics Interventions: bevacizumab, ranibizumab | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI), mixed evidence** | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Reason for downgrading certainty of evidence | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Bevacizumab | Ranibizumab | ||||

| Gain 3+ lines of visual acuity at 1 year | 300 per 1000 | 333 per 1000 (261 to 429) | RR 1.11 (0.87 to 1.43) | ⊕⊕⊕ moderate | Imprecise estimate (−1) |

|

Visual acuity change at 1 year Measured on the logMAR scale, range −1.3 to 1.3. Higher values represent worse visual acuity. |

On average visual acuity improved by −0.19 logMAR units in the bevacizumab group between the start of treatment and 1 year | Average change in visual acuity was0.00 (−0.02 to 0.03) logMAR units (same) with ranibizumab compared with bevacizumab | ⊕⊕⊕ moderate | Unclear risk of bias (−1) | |

|

Central retinal thickness (CRT) change at 1 year The aim of treatment is to reduce central macular thickness so thinner is better. |

On average CRT changed by −98 μm in the bevacizumab group between the start of treatment and 1 year (became thinner) | Average change in CRT was −29 (−58 to −1) μm more (thinner) with ranibizumab compared with bevacizumab | ⊕⊕ low | Unclear risk of bias (−1) Imprecise estimate (−1) | |

| Quality of life at 1 year | No data available | ||||

| All serious systemic adverse events at 1 to 2 years | 240 per 1000 |

250 per 1000 (202 to 307) |

RR 1.04 (0.84 to 1.28) |

⊕⊕⊕ moderate | Unclear risk of bias (−1) |

| Arterial thromboembolic events at 1 to 2 years | 60 per 1000 |

70 per 1000 (26 to 189) |

RR 1.17 (0.43 to 3.13) |

⊕ very low | Unclear risk of bias (−1) Imprecise estimate (−2) |

| Death at 1 to 2 years | 40 per 1000 |

29 per 1000 (9 to 95) |

RR 0.73 (0.22 to 2.37) |

⊕ very low | High risk of bias (−2) Imprecise estimate (−2) |

| The assumed risk in the bevacizumab group was estimated as the row sum of the events divided by the row sum of the participants (eyes) for dichotomous variables, and as the (unweighted) median change of visual acuity or central retina thickness. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ** The risk ratio was estimated from mixed (direct and indirect) comparisons. CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate‐certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low‐certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low‐certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

Background

Description of the condition

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the most frequent and severe ocular complication of diabetes mellitus (DM) and the leading cause of blindness in the working age population in developed countries (Frank 2004; Klein 1984; Tranos 2004).

Diabetic macular oedema (DMO) is the swelling of the retina resulting from the exudation and accumulation of extracellular fluid and proteins in the macula (Ciulla 2003), due to the breakdown of the blood‐retina barrier with an increase in vascular permeability (Antcliff 1999). About a third of people with diabetes have DR and one in 10 is affected by DMO (Yau 2012). The prevalence of DMO increases with diabetes duration, haemoglobin A1c, and blood pressure levels and is higher in people with type 1 compared with type 2 diabetes (Yau 2012).

Intraretinal fluid accumulation results in significant reduction in visual acuity that may be reversible in the short term, but prolonged oedema can cause irreversible damage resulting in permanent visual loss. Blurred vision represents the most common clinical symptom of DMO. Other symptoms can include metamorphopsia (distortion of visual image), floaters, changes in contrast sensitivity, photophobia (visual intolerance to light), changes in colour vision and scotomas (a localised defect of the visual field).

During the last decades, the clinical gold standard to detect macular oedema has been fundus examination with contact lens, but non‐contact lenses can also be used for this purpose with good sensitivity. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has progressively been used as an objective and reproducible tool to measure retinal thickness and has been suggested to be the new gold standard for diagnosing DMO (Olson 2013; Ontario HTA 2009). The most severe form of DMO is CSMO, which was defined by the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) as: retinal oedema within 500 µm of the centre of the fovea; hard exudates within 500 µm of the centre of the fovea, if associated with adjacent retinal thickening (which may be outside the 500 µm limit); and one disc area of retinal oedema (1500 µm) or larger, any part of which is within one disc diameter of the centre of the fovea (ETDRS 1985). Since its introduction, OCT was found to be in good agreement with the clinical gold standard (slit‐lamp examination with a contact lens) for detecting the presence of macular oedema and was found to be potentially more sensitive in cases of mild foveal thickening (Brown 2004). A simple OCT‐based classification of DMO is often used as centre‐involving or non‐centre‐involving DMO (Browning 2008).

Description of the intervention

Antiangiogenic therapy has been believed a standard of care for treatment of DMO and has largely replaced laser photocoagulation (Jampol 2014), than which it was proven to be more effective (Virgili 2014). Anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor (anti‐VEGF) treatments inhibit VEGF angiogenic activity, binding to VEGF protein and thus preventing its receptor activation or interaction. These drugs were originally hypothesised as an alternative adjunctive treatment for DMO (Cunningham 2005), following evidence that VEGF‐A plays a key role in the occurrence of increased vascular permeability in ocular diseases such as DMO (Aiello 2005).

Grid or focal laser photocoagulation could not be used in all patients with DMO; thus, either laser or sham procedures were current practice comparators in initial studies on the efficacy of antiangiogenic drugs for DMO (Macugen 2005; RESOLVE 2010; RESTORE 2011; Soheilian 2007), and only recently have directly comparative RCTs been conducted (DRCRnet 2015).

Safety of intravitreal antiangiogenic therapy is acceptable; endophthalmitis, the major adverse event (< 1/1000 injections) is related to the surgical injection procedure, rather than the drug itself. These drugs were shown not to increase systemic adverse events such as arterial thromboembolic events, but differences between drugs are not well known (Virgili 2014).

Another therapeutic option for DMO treatment is represented by steroids, administered as intravitreal injections or sustained release implants in order to obtain high local concentrations, maximising their anti‐inflammatory, angiostatic and anti‐permeability effects while minimising systemic toxicity (Ciulla 2004; Haller 2010; Kuppermann 2010). However, intravitreal steroids may cause cataract and ocular hypertension and the visual outcome is dependent on the lens status or the need for cataract surgery after about one year (Haller 2010; Campochiaro 2010). Currently, some investigators think intravitreal steroids are preferred in patients with anti‐VEGF resistant and chronic DMO (Hussain 2015), as an alternative to switching between anti‐VEGF drugs. This is also consistent with the EU label of the only approved dexamethasone intravitreal implant in Europe: "Ozurdex is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with visual impairment due to diabetic macular oedema (DME) who are pseudophakic or who are considered insufficiently responsive to, or unsuitable for non‐corticosteroid therapy" (accessed on EMA on 4 December 2016).

For ranibizumab, the EU label prescribes a 0.5 mg dosage, and that "treatment is initiated with one injection per month until maximum visual acuity is achieved and/or there are no signs of disease activity i.e. no change in visual acuity and in other signs and symptoms of the disease under continued treatment. In patients with wet AMD, DME and RVO, initially, three or more consecutive, monthly injections may be needed. Thereafter, monitoring and treatment intervals should be determined by the physician and should be based on disease activity, as assessed by visual acuity and/or anatomical parameters" (accessed on EMA on 4 December 2016). In the USA, ranibizumab "0.3 mg is recommended to be administered by intravitreal injection once a month (approximately 28 days)" (accessed on FDA on 4 December 2016).

Aflibercept has been approved in the USA, as accessed on FDA on 4 December 2016, and "the recommended dose for EYLEA is 2 mg (0.05 mL) administered by intravitreal injection every 4 weeks (monthly) for the first 5 injections followed by 2 mg (0.05 mL) via intravitreal injection once every 8 weeks (2 months)". The EU label is similar (accessed on EMA on 4 December 2016).

Bevacizumab is widely used off‐label although its use has been questioned based on regulatory or safety issues (Banfi 2013), but is still key for treating chorioretinal vascular disease in low‐ and middle‐income countries thanks to its low cost (Stewart 2016).

How the intervention might work

VEGF plays a key role in the occurrence of increased vascular permeability in ocular diseases such as DMO (Aiello 2005). Anti‐VEGF agents inhibit VEGF angiogenic activity, binding to VEGF protein thus preventing its receptor activation and interaction.

Why it is important to do this review

DMO results in a significant burden of low vision and blindness, thus the extent of the existing evidence base for the effectiveness and safety of these agents needs to be assessed and updated. There is a continuing clinical need to establish evidence‐based recommendations regarding anti‐VEGF agents.

Objectives

The 2014 update of this review found high‐quality evidence of benefit with antiangiogenic therapy with anti‐VEGF modalities, compared to laser photocoagulation, for the treatment of DMO. As was concluded in the previous version (Virgili 2014), the objective of this updated review is to compare the effectiveness and safety of the different anti‐VEGF drugs in preserving and improving vision and quality of life using network meta‐analysis methods.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

People with DMO for whom anti‐VEGF treatment is indicated. We expected to include most of the studies also included in Virgili 2014.

Types of interventions

Any antiangiogenic drug with anti‐VEGF modalities compared with another drug with anti‐VEGF modalities, laser treatment, sham treatment or no treatment. The reasons for selecting treatments of direct and indirect treatment have been discussed in the Description of the intervention section. As explained above, we remark that steroids may be compared with anti‐VEGF drugs but this needs a different approach, specifically patient subgroups and timing, and their inclusion could lead to violation of similarity in a review aiming to compare different anti‐VEGF drugs such as this.

Regarding drug dose and monitoring/retreatment regimen, in efficacy analyses we included schemes that are either on‐label or commonly used in clinical practice, such as the PRN regimen, as presented in the Description of the intervention section. Particularly, both 0.3 mg and 0.5 mg ranibizumab dose are included as available in studies. These two ranibizumab doses were merged into one group in our NMA since studies suggest no difference between them when used monthly (Heier 2016). Regarding aflibercept, we selected the bi‐monthly retreatment regimen since this is the approved label in the USA. We used all available data regardless of safety and dose for safety analyses as previously done in Moja 2014.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Best‐corrected visual acuity (BCVA) expressed as the proportion of participants with at least 15 ETDRS letters (3 ETDRS lines or 0.3 logMAR) of improvement in BCVA from baseline to 12 months.

Secondary outcomes

Mean change in BCVA from baseline to 12 months, measured using ETDRS charts.

Mean change in central retinal thickness (CRT), from baseline to 12 months, measured using optical coherence tomography (OCT).

Mean change in quality of life from baseline to 12 months, measured using a validated instrument.

Measurements at varying lengths of follow‐up were pooled at annual intervals, plus or minus six months, the primary analysis being that at 12 months. The time point closer to 12 months, or the latest time point in the window frame in the case of symmetry, was chosen where multiple time points were available.

Adverse events

The following adverse events were considered.

All‐cause mortality.

Arterial thromboembolic events (ATC 1994).

Systemic serious adverse events (SSAEs).

Adverse events were analysed at the longest available follow‐up time (Moja 2014).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials. There were no language or publication year restrictions. The date of the search was 26 April 2017.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 3) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) in the Cochrane Library (searched 26 April 2017) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 26 April 2017) (Appendix 2);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 26 April 2017) (Appendix 3);

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database (1982 to 26 April 2017) (Appendix 4);

ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch; searched 26 April 2017) (Appendix 5);

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 26 April 2017) (Appendix 6);

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp; searched 26 April 2017) (Appendix 7).

Searching other resources

We handsearched the reference lists of the included trials for other possible trials. We accessed the Novartis Clinical Trials database (www.novctrd.com/ctrdWebApp/clinicaltrialrepository/public/main.jsp) on 28 May 2014 and checked all trials indexed under the headings: Ophthalmic Disorders and ranibizumab.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently selected the studies for inclusion. The titles and abstracts of all reports identified by the electronic searches and handsearching were examined by the review authors. We classified the abstracts as (a) definitely include, (b) unsure and (c) definitely exclude. We obtained and re‐assessed full‐text copies of those classified as either (a) definitely include or (b) unsure. Having reviewed the full‐text copies, we classified the studies as (1) included, (2) awaiting assessment and (3) excluded. Studies identified by both review authors as 'excluded' were excluded and documented in the review. Studies identified as 'included' were included and assessed for methodological quality. The review authors were unmasked to the report authors, institutions and trial results during this assessment. Disagreements between the two review authors were resolved by a third review author.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted the data for the primary and secondary outcomes onto paper data extraction forms developed by the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group. A pilot test of this form was carried out using a small number of studies. We resolved discrepancies by discussion. One review author entered all data into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 5 2014). The entered data were checked by a second author. In case standard deviations were not available in the publication, and could not be obtained from the authors, these were imputed from standard deviations of other studies with the same comparison.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the included trials for bias according to the methods described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). The following parameters were assessed: sequence generation; allocation concealment; masking (blinding) of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting. We evaluated these parameters for each outcome measure or class of outcome measure. We classified each parameter as low risk of bias, high risk of bias or unclear.

If the information available in the published trial reports was inadequate to assess methodological quality, we contacted the trial authors for clarification. We had planned that if they did not respond within six months we would assess the trial based on the available information. However, in the latest update of this review we assessed the trial had the authors not responded within one month.

We followed Salanti 2014 to assess the risk of bias of mixed evidence (mixed evidence not defined previously).

Summary risk of bias for each trial: we considered all domains but gave more importance to allocation concealment and masking of outcome assessor.

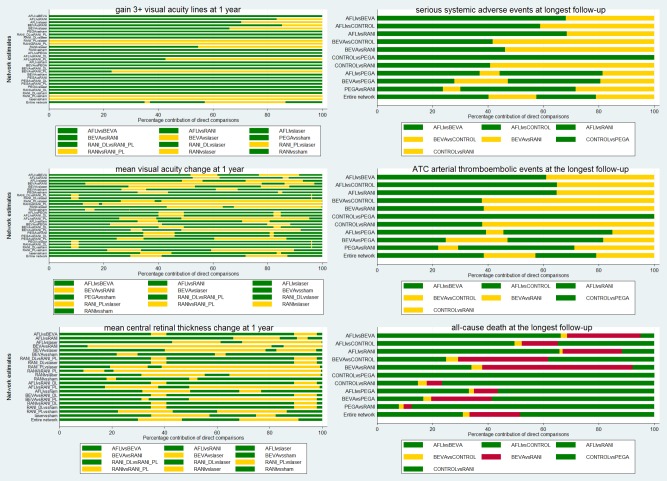

Summary risk of bias for the mixed evidence: based on the percentage contribution of each direct comparison to each network estimate using the contribution plot (Chaimani 2013).

We finally integrated the risk of bias of a given comparison with the assessment of transitivity, or similarity of the characteristics of the studies. We expected the transitivity assumption would hold as long as treatment comparisons were not related to:

acute versus chronic DMO, defined using the cut‐off of three or more years of duration;

average severity of DMO using OCT CRT of 400 micrometres as a cut‐off;

treatment regimen, such as monthly versus less than monthly and number of injections in the first year;

drug dose for ranibizumab, since this is commercially available in two doses (0.3 mg in the USA, 0.5 mg otherwise);

whether the trial was industry sponsored.

Measures of treatment effect

Data analysis followed the guidelines set out in Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011). For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated a summary risk ratio (RR). For continuous outcome, we calculated the mean difference (MD). We planned to calculate a standardised mean difference (SMD) had different scales been used to measure the same continuous outcome.

We did not use ranking measures in this review, since our main interest was to compare only three drugs: aflibercept, bevacizumab and ranibizumab.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of randomisation was the eye of individual participants. We included one cross‐over study comparing ranibizumab and bevacizumab and treated this as a parallel arm study (Wiley 2016), which equals to assume a moderate (0.5) correlation within‐person. However, relative drug safety is impossible to assess with a paired design.

We accepted studies presenting systemic adverse events as the unit of analyses, i.e. when an individual suffers from more than one severe adverse event in the study.

Dealing with missing data

Where data were missing due to dropping out of participants, we conducted a primary analysis based on participants with complete data (available case analysis). Following the guidance available in Chapter 16 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a), we considered that missing outcome data are missing at random if the reasons for loss to follow‐up are documented and judged to be unrelated to outcome in both study arms.

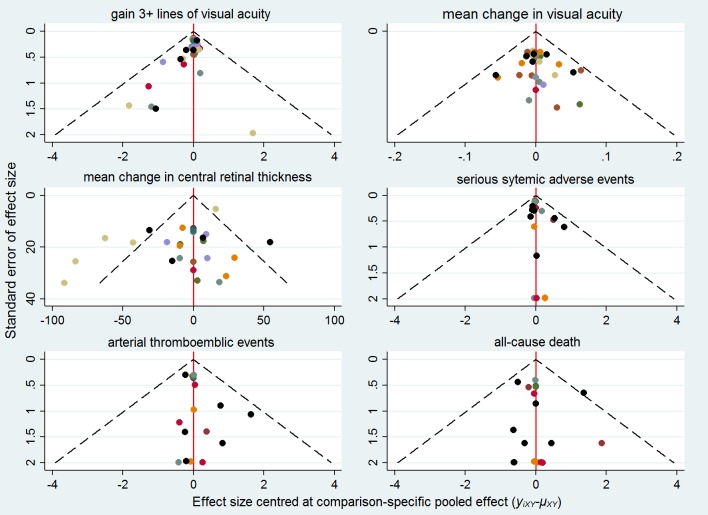

Assessment of reporting biases

To investigate small‐study bias at the network level we employed the comparison‐adjusted funnel plot, which is an adaptation of the funnel plot. We subtracted from each study‐specific effect size the mean of meta‐analysis of the study‐specific comparison and plotted it against the study’s standard error (Chaimani 2013).

Data synthesis

Methods for direct treatment comparisons

If there was no substantial statistical heterogeneity, and if there was no clinical heterogeneity between the trials, we combined the results in a meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model. A fixed‐effect model was used if the number of trials was three or less. In the case of substantial statistical heterogeneity (that is I² value more than 50%) or clinical heterogeneity, we combined the results in a meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model if the individual trial results were all consistent in the direction of the effect (that is the RR or MD and confidence intervals largely fall on one side of the null line); when the individual trial results were inconsistent in the direction of the effect, we did not combine study results but presented a narrative or tabulated summary of each study.

Methods for indirect and mixed comparisons

We performed network meta‐analysis using the methodology of the multivariate meta‐analysis model where different treatment comparisons are treated as different outcomes (Salanti 2012). For this analysis, we used the 'network' suite of commands available in STATA (StataCorp, 2011; Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX) (White 2015).

We presented mixed effects as RRs or MDs against laser photocoagulation as a single comparison. We prepared league tables presenting mixed comparisons in the inferior‐left part and direct comparisons in the superior‐right part of the table in order to allow for the inspection of both types of evidence. The same information was presented graphically. We also presented the contribution of direct and indirect evidence to mixed evidence using contribution plots (Chaimani 2013).

Assessment of statistical heterogeneity

In standard pairwise meta‐analyses, we estimated heterogeneity variances for each direct comparison. We assessed statistically the presence of heterogeneity within each pairwise comparison using the I² statistic (Higgins 2011b). The I² statistic measures the percentage of variability that cannot be attributed to random error. In network meta‐analysis, we assumed a common estimate for the heterogeneity variance across the different comparisons. The assessment of statistical heterogeneity in the entire network was based on the magnitude of the heterogeneity variance parameter (τ²) estimated from the network meta‐analysis models.

Assessment of statistical inconsistency

Local approaches for evaluating inconsistency

To evaluate the presence of inconsistency locally, we used the node‐splitting approach (Dias 2010). We assumed a common heterogeneity estimate within each loop.

Global approaches for evaluating inconsistency

To check the assumption of consistency in the entire network, we used the 'design‐by‐treatment' model using the 'network' command in STATA (White 2015). This method accounts for different sources of inconsistency that can occur when studies with different designs (two‐arm trials versus three‐arm trials) give different results as well as disagreement between direct and indirect evidence. Using this approach, we judged the presence of inconsistency from any source in the entire network based on a Chi² test.

'Summary of findings' table and GRADE assessment

We prepared one 'Summary of findings' table for each relevant comparison, including all seven outcomes in a table (GRADEpro 2014). As originally intended, the primary analysis was conducted at 12 months. Relevant comparisons were identified to answer the question of which antiangiogenic drug is most effective among on‐label (aflibercept, ranibizumab) and off‐label (bevacizumab) drugs that are currently available. Because most of the available evidence is around ranibizumab, we reported on the comparison of aflibercept and bevacizumab with ranibizumab. Analyses conducted at 24 months were presented textually because a network meta‐analysis was not feasible.

We graded the certainty of the evidence for mixed estimates as explained above. We started from the premise that RCTs provide high‐certainty evidence and downgraded for each GRADE parameter to get an overall certainty for each outcome as high, moderate, low or very low (Higgins 2014; Salanti 2014; Schünemann 2011). We estimated the absolute risk in the control group from the data in the included studies as the raw proportion with event for dichotomous outcomes and the median value for continuous outcomes.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

We had not planned sensitivity analyses but we decided post‐hoc to conduct one excluding studies which were assessed as being at overall high or unclear risk of bias. Moreover, we acknowledge that DRCRnet 2015 emphasised that the differences in absolute benefit between aflibercept, bevacizumab and ranibizumab at one year were dependent on baseline visual acuity, but when we considered this post hoc subgroup analysis we did not find enough study data to conduct such meta‐regression analyses.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

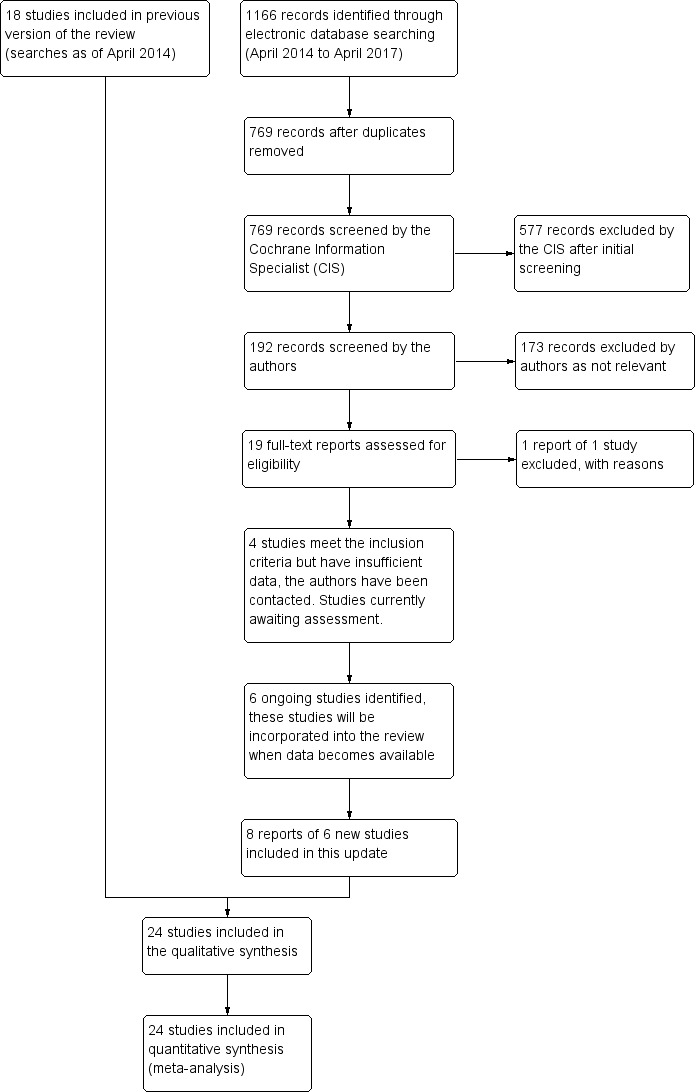

The previous version of this review included 18 trials. Update searches run in April 2017 yielded a further 1166 records (Figure 1). After 397 duplicates were removed, the Cochrane Information Specialist screened the remaining 769 records and removed 577 references that were not relevant to the scope of the review. We screened the remaining 192 references and obtained 19 full‐text reports for further assessment. We identified eight reports of six new trials for inclusion in the review (DRCRnet 2015, Ishibashi 2014, Lopez‐Galvez 2014, REVEAL 2015, Turkoglu 2015, Wiley 2016). A further four trials were deemed eligible but did not provide sufficient data for analysis (Chen 2016; Huang 2016; Jovanovic 2015;Fouda 2017. We have contacted these authors to ask for further information and will assess these studies if we receive additional data. We excluded one study (NCT02985619 (BEVATAAC)) and have identified six new ongoing studies and will assess these for inclusion in the review when data becomes available (NCT02194634;NCT02259088; NCT02348918; NCT02645734; NCT02699450; NCT02712008).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included a total of 24 studies in this updated systematic review and network meta‐analysis. BOLT 2010, DA VINCI 2011, Ishibashi 2014, Korobelnik 2014, Macugen 2005, Macugen 2011, READ2 2009, RELATION 2012, RESOLVE 2010, RESPOND 2013, RESTORE 2011, and RISE‐RIDE were industry‐sponsored, multicentre RCTs conducted in the USA or Europe, whereas REVEAL 2015 was industry‐sponsored but conducted in Asia. Ahmadieh 2008, Azad 2012, Ekinci 2014, LUCIDATE 2014, Nepomuceno 2013, Soheilian 2007, and Turkoglu 2015 were independent studies conducted in Brazil, India, Iran, Turkey, and the UK, five of which included bevacizumab. DRCRnet 2010, DRCRnet 2015, Wiley 2016 were publicly‐sponsored studies, mainly by the US National Eye Institute, and conducted in the USA or UK. DRCRnet 2015 was the only large parallel‐arm study that compared all commercially available drugs (aflibercept, bevacizumab, ranibizumab) and was a large publicly‐funded trial comparing aflibercept, bevacizumab and ranibizumab with monthly monitoring and treatment as needed (PRN). Wiley 2016 was a cross‐over trial comparing the same three drugs. Lopez‐Galvez 2014 was an open‐label trial comparing ranibizumab with laser; it was conducted in Spain and results were available only in abstract form.

Only six trials maintained the randomisation scheme at two years' follow‐up (BOLT 2010; DRCRnet 2010; DRCRnet 2015; Macugen 2011; READ2 2009; RISE‐RIDE). Two industry‐sponsored trials used randomisation up to two years (Macugen 2011; RISE‐RIDE), while three others obtained follow‐up data but allowed anti‐VEGF treatment in the control arm after one year (Korobelnik 2014; RESOLVE 2010; RESTORE 2011).

We did not extract data on comparisons of antiangiogenic therapy with triamcinolone and other intravitreal steroids, which were study arms in Ahmadieh 2008, Azad 2012, DRCRnet 2010 and Soheilian 2007, for reasons presented above and also because this comparison is the subject of another Cochrane Review (Grover 2008). Standard deviations of change in CRT were imputed from other studies in REVEAL 2015.

Types of participants

Trials included participants with DMO diagnosed clinically, and often these trials used OCT for confirming macular centre involvement. Baseline visual acuity of participants was generally between 20/200 and 20/40. Most trials required a three‐ to six‐month interval from previous central or peripheral laser, and a few small studies required that participants had not received previous antiangiogenic treatment.

Types of interventions

Eleven studies assessed ranibizumab (DRCRnet 2010; Lopez‐Galvez 2014; LUCIDATE 2014; READ2 2009; RELATION 2012; RESOLVE 2010; RESPOND 2013; RESTORE 2011; REVEAL 2015; RISE‐RIDE; Turkoglu 2015), six investigated bevacizumab (Ahmadieh 2008; Azad 2012; BOLT 2010; Ekinci 2014; Nepomuceno 2013; Soheilian 2007), two pegaptanib (Macugen 2005; Macugen 2011), and three aflibercept (DA VINCI 2011; and two studies conducted in the USA and Europe using the same protocol, which we will refer to as a single study (Korobelnik 2014). DRCRnet 2015 and Wiley 2016 were the only studies comparing ranibizumab, bevacizumab or aflibercept directly. The drug dose was the same in most studies (0.5 mg ranibizumab, 1.25 mg bevacizumab, 0.3 mg pegaptanib, 2 mg aflibercept) except for RESOLVE 2010 where dose adjustment was allowed for ranibizumab, and also RISE‐RIDE, DRCRnet 2015 and Wiley 2016 where 0.3 mg ranibizumab was also delivered.

Anti‐VEGF treatment regimens were monthly in RISE‐RIDE, in one arm of Korobelnik 2014 and in Wiley 2016. Monthly, bimonthly and 'as needed' or pro re nata (PRN) regimens were adopted in four arms of DA VINCI 2011, and we selected PRN for efficacy data extraction because this is current practice with other anti‐VEGF drugs. Ahmadieh 2008 was a short‐term study which delivered only the first three injections. Most other studies adopted three initial injections followed by various maintenance regimens. Two studies on aflibercept, reported in Korobelnik 2014 (VISTA and VIVID), compared laser photocoagulation with both monthly injections (2q4) and a regimen of five initial monthly injections followed by bimonthly injections (2q8) followed by a 'treat‐and‐extend' regimen in year two.

PRN retreatment criteria were based on: visual acuity only in Nepomuceno 2013 and REVEAL 2015; OCT only in BOLT 2010, Macugen 2011 and READ2 2009; OCT and visual acuity in Azad 2012, DRCRnet 2010, DRCRnet 2015, Ekinci 2014, RESOLVE 2010 and in the PRN arm of DA VINCI 2011; inclusion of clinical examination or at the examiners' discretion in Macugen 2005, RESTORE 2011 and Soheilian 2007. They were unclear in Lopez‐Galvez 2014, RELATION 2012 and RESPOND 2013.

Types of outcomes

The data structure of our efficacy and safety outcomes can be seen in Table 5 where the sum of cases for each outcome is shown.

Table 1.

Reporting of all outcomes across studies

| Study |

Gain 3+ VA lines |

Mean VA change |

Mean CMT change |

QOL | SSAE | ATC | Death | |||||||

| Follow‐up year | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Ahmadieh 2008 | 78 | 78 | ||||||||||||

| Azad 2012 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | ||||||||||

| BOLT 2010 | 80 | 65 | 80 | 65 | 80 | 65 | 80 | 80 | 80 | |||||

| DA VINCI 2011 | 89 | 89 | 87 | 89 | 89 | 89 | ||||||||

| DRCRnet 2010 | 668 | 486 | 668 | 486 | 617 | 483 | 240 | 505 | 505 | |||||

| DRCRnet 2015 | 620 | 577 | 620 | 577 | 620 | 577 | 660 | 660 | 660 | |||||

| Ekinci 2014 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||||||||

| Ishibashi 2014 | 233 | 233 | 233 | 233 | 233 | 233 | ||||||||

| Korobelnik 2014 | 573 | 573 | 573 | 865 | 865 | 865 | ||||||||

| LUCIDATE 2014 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | ||||||||

| Macugen 2005 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 86 | |||||||||

| Macugen 2011 | 260 | 207 | 260 | 236 | 286 | 286 | 286 | |||||||

| Nepomuceno 2013 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | ||||||||||

| READ2 2009 | 115 | 115 | 117 | 117 | ||||||||||

| RELATION 2012 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | ||||||||||

| RESOLVE 2010 | 151 | 151 | 151 | 151 | 151 | 151 | ||||||||

| RESPOND 2013 | 203 | 203 | 202 | 237 | 237 | |||||||||

| RESTORE 2011 | 343 | 343 | 343 | 299 | 345 | 345 | 345 | |||||||

| REVEAL 2015 | 390 | 390 | 268 | |||||||||||

| RISE‐RIDE | 509 | 504 | 500 | 500 | ||||||||||

| Soheilian 2007 | 87 | 85 | 85 | 96 | ||||||||||

| Turkoglu 2015 | 70 | 70 | 70 | |||||||||||

| Wiley 2016 | 124 | 124 | ||||||||||||

| Total studies | 17 | 5 | 21 | 3 | 16 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 12 | 5 |

| Total participants | 4031 | 1844 | 4489 | 1128 | 3491 | 1125 | 838 | 504 | 1598 | 2631 | 1322 | 2396 | 1639 | 2816 |

Numbers in the table are the total number of eyes for each study,as available by follow‐up year (1 or 2) and outcome measure.

Studies awaiting assessment

Several trials were included as ongoing in the previous version of this review. We checked the completion status on the study trial register and tried to contact the authors, but were not able to obtain additional information (NCT00387582; NCT00997191 (IBeTA); NCT01445899 (MATISSE); NCT01565148 (IDEAL)).

Two Chinese trials (Chen 2016, 72 participants; Huang 2016, 78 participants) compared ranibizumab plus laser or, respectively, ranibizumab to grid laser. These trials provided baseline and final CRT data at six months as well as the proportion with visual improvement, but the improvement cut‐off was unclear, as was the measurement tool.

Jovanovic 2015 included 72 participants (120 eyes) randomised to either bevacizumab (one or more injections with or without macular laser photocoagulation depending on results after four to six weeks) or macular laser alone to treat DMO. However, results were not provided at desired fixed follow‐up times by each randomisation group.

Fouda 2017 included 42 participants (70 eyes) randomised to aflibercept or ranibizumab and treated with three initial injections and then PRN. The authors did not find any significant difference between the two drugs in terms of BCVA, but used decimal rather than logMAR visual acuity and we could not use these data in analyses (authors contacted). The authors reported no difference regarding CRT and a smaller but statistically significant number of injections with aflibercept versus ranibizumab.

Excluded studies

See 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table for the list of exclusions with reasons.

Risk of bias in included studies

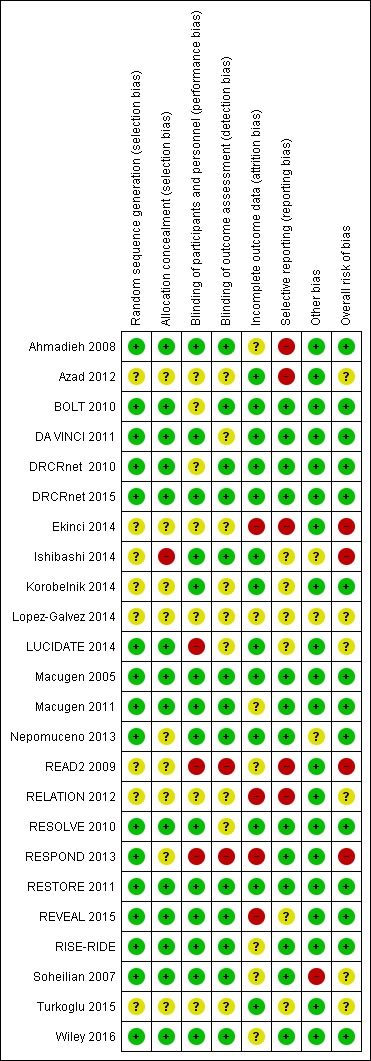

See 'Risk of bias in included studies'; Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation was judged at low risk of bias in 12 studies and was unclear in nine (Azad 2012; Ekinci 2014; Lopez‐Galvez 2014; Ishibashi 2014; Korobelnik 2014; READ2 2009; RELATION 2012; RESPOND 2013; Turkoglu 2015). Method for allocation concealment was also unclear in these studies, as they were in Nepomuceno 2013. Allocation concealment was judged at high risk of bias in Ishibashi 2014.

Blinding

Masking of participants and outcome assessors was obtained in 14 and 12 trials respectively, and was unclear in seven and nine trials respectively. LUCIDATE 2014, READ2 2009 and RESPOND 2013 were unmasked.

Incomplete outcome data

Eleven trials were judged at low risk of attrition bias (Azad 2012; BOLT 2010; DA VINCI 2011; DRCRnet 2010; DRCRnet 2015; Korobelnik 2014; LUCIDATE 2014; Macugen 2005; Nepomuceno 2013; RESOLVE 2010; RESTORE 2011); and eight trials were judged at unclear risk of bias in which some participants were missing but reasons for missingness were not fully reported (Ahmadieh 2008; Ishibashi 2014; Macugen 2011; READ2 2009; RISE‐RIDE; Soheilian 2007; Turkoglu 2015; Wiley 2016). Five trials were judged at high risk of attrition bias: Ekinci 2014 excluded 15 participants after randomisation due to ocular and systemic complications; Lopez‐Galvez 2014 lost about 20% of participants in each arm and did not report the reasons; RELATION 2012, RESPOND 2013 and REVEAL 2015 lost many more participants in the laser arm than in the ranibizumab arms.

Selective reporting

Table 5 shows the reporting of all outcomes across 24 trials. Reporting was almost complete for mean VA change at one year (21 studies, 4489 complete cases). Mean CRT change was available in 16 studies (3491 cases). Gain of 3 or more VA lines was reported at one year in 17 studies (4031 cases). SSAEs at one or two years were reported from 18 studies (4229 cases). ATC thromboembolic events were reported in 15 (3718 cases) and death in 17 (4455 cases).

Other potential sources of bias

The baseline visual acuity was not balanced in Soheilian 2007; the visual acuity was around 20/100 in the bevacizumab and bevacizumab‐triamcinolone arms and 20/70 in the laser arm, suggesting that milder CSMO was included in the laser arm. The trial investigators adjusted for baseline values in the analyses, which also took into account the within‐participant correlation (150 eyes of 129 participants, 16% of participants with both eyes in the analyses). However, we could not take within‐participant correlation into account when analysing dichotomous visual acuity.

Three studies included both eyes of some participants in analyses: Ahmadieh 2008 14 out of 101 participants; Nepomuceno 2013 15 out of 48 participants; Wiley 2016 6 out of 56 participants.

RELATION 2012 was terminated early when ranibizumab was approved for DMO in Germany. Early termination was unlikely to be associated with treatment effect.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Antiangiogenic drugs versus laser photocoagulation or control: efficacy and safety

Table 1 presents the evidence on the comparison of each drug with laser photocoagulation (efficacy at one year) or control (laser photocoagulation or sham at the longest available follow‐up of one or two years).

Efficacy at one year

As found in the previous version of this review based on direct meta‐analyses (Virgili 2014), there was high‐certainty of evidence of benefit for aflibercept, bevacizumab and ranibizumab compared to laser photocoagulation at one year. Specifically, aflibercept, bevacizumab and ranibizumab were all more effective than laser for improving vision by 3 or more lines after one year, since about one in 10 people improve vision with laser, and about three in 10 people improve with anti‐VEGF treatment: risk ratio (RR) versus laser was 3.66 (95% CI 2.79 to 4.79) for aflibercept; 2.47 (95% CI 1.81 to 3.37) for bevacizumab; and 2.76 (95% CI 2.12 to 3.59) for ranibizumab. Regarding change of mean BCVA, on average there was no change with laser after one year, compared with a gain of 1 or 2 lines with anti‐VEGF treatment: laser versus aflibercept mean difference (MD) −0.20 (95% CI −0.22 to −0.17) logMAR; versus bevacizumab −0.12 (95% CI −0.15 to −0.09) logMAR; versus ranibizumab −0.12 (95% CI −0.14 to −0.10) logMAR (negative logMAR in favour of anti‐VEGF group).

The certainty of evidence was moderate for bevacizumab versus laser regarding mean BCVA change due to inconsistency of direct and indirect evidence.

Safety at the longest available follow‐up

This network meta‐analysis confirms that aflibercept, bevacizumab and ranibizumab do not increase the risk of all SSAEs compared to laser photocoagulation or sham at one year. We considered this evidence of high‐certainty. (Table 1), Of notice, SSAEs are a generic indicator of harm, mostly including hospitalisation or death for any cause and unrelated to antiangiogenic effect.

Regarding 'Antiplatelet Trialists Collaboration arterial thromboembolic events' and all‐cause death, no statistically significant difference was found between any anti‐VEGF drug and control, but the certainty of the evidence was generally low due to imprecision (large 95% CIs).

Quality of life

Only RESTORE 2011, RESPOND 2013 and Turkoglu 2015 presented quality of life data for ranibizumab versus laser photocoagulation at six to 12 months (3 studies, 412 participants). Ranibizumab improved NEI‐VFQ composite score by 5.14 units (95% CI 2.96 to 7.32) compared to laser (Table 1). The certainty of the evidence was moderate due to risk of bias issues (RESPOND 2013 was unmasked and Turkoglu 2015 was unclear for most items).

Macugen 2011 obtained QOL data at two years and we did not include these data since pegaptanib was not of direct interest and sham, rather than laser, was the comparator. RISE‐RIDE obtained QOL data at two years and was not included since sham, rather than laser, was the control group.

Ranibizumab versus aflibercept and bevacizumab

Efficacy at one year

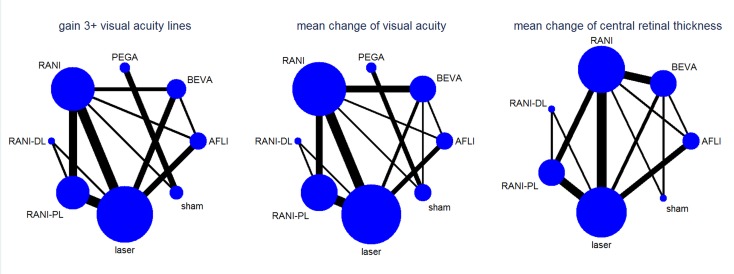

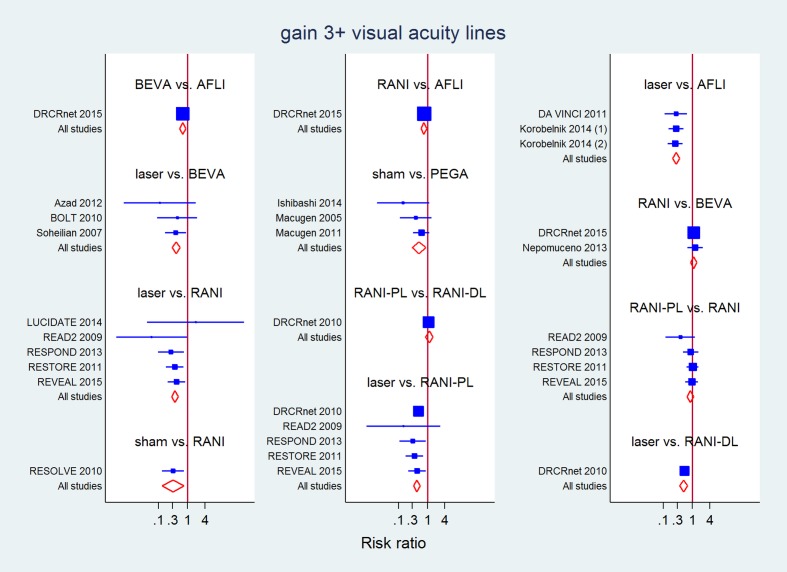

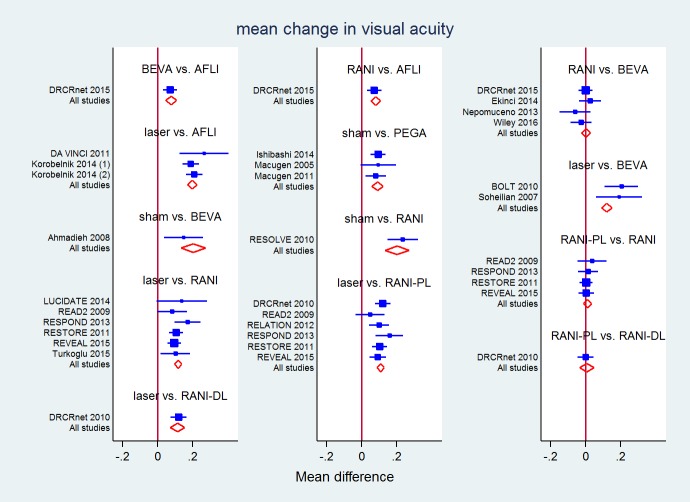

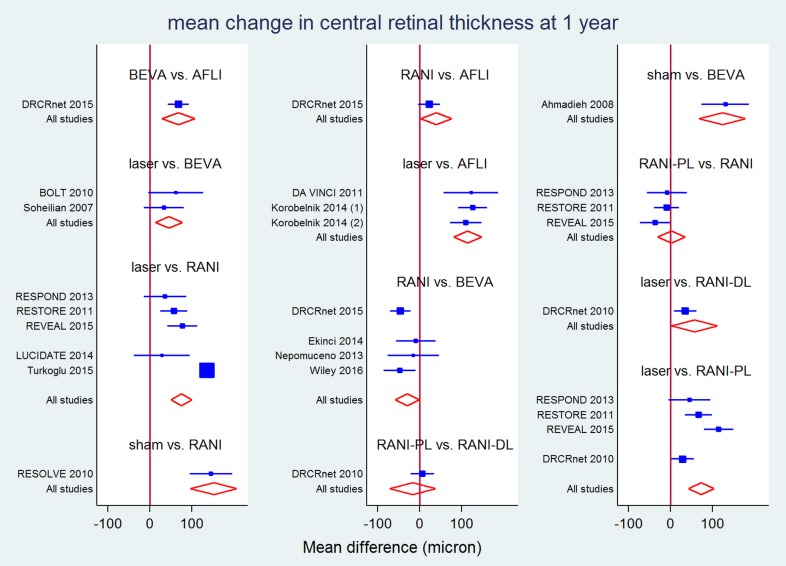

Table 6 presents the number of studies (participants/eyes) in all treatment arms of the network for the efficacy outcomes at one year. Figure 3 presents the corresponding networks' structure. As seen, more data was available for ranibizumab, alone or combined with laser, with respect to aflibercept and bevacizumab. Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 present forest plots with effects for each study, estimates from direct pairwise meta‐analysis and mixed estimate from the network meta‐analysis. Table 2 and Table 3 present comparisons of ranibizumab versus aflibercept and bevacizumab.

Table 2.

Network structure: efficacy at 12 months

| Laser | Aflibercept | Bevacizumab | Pegaptanib | Ranibizumab | Ranibizumab deferredlaser | Ranibizumab prompt laser | Sham | Overall | |

| Gain 3+ lines | 12 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 17 |

| 1074 | 539 | 344 | 410 | 713 | 188 | 545 | 218 | 4031 | |

| Mean VA change | 13 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 11 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 21 |

| 1131 | 539 | 476 | 410 | 861 | 188 | 629 | 255 | 4489 | |

| Mean CRT change | 11 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 16 | |

| 986 | 538 | 476 | 779 | 175 | 451 | 86 | 3491 | ||

| QOL | 4 | 4 | |||||||

| 838 | 838 |

For each efficacy outcome, numbers in the table are the total number of studies (upper line for each outcome) and the total number of eyes (lower line for each outcome), as available by treatment and measured at one year.

Figure 3.

Network structure for efficacy outcomes at 1 year

Figure 4.

All direct and mixed comparisons: gain of 3 or more lines of visual acuity at 1 year

Figure 5.

All direct and mixed comparisons: mean change in visual acuity at 1 year

Figure 6.

All direct and mixed comparisons: mean change in central retinal thickness at 1 year (micron)

Comparing the available drugs as monotherapy, all efficacy outcomes significantly favoured aflibercept over ranibizumab and bevacizumab (Table 7; Table 8; Table 9). Compared with ranibizumab and bevacizumab, aflibercept increased the chances of gaining 3 or more lines (17 studies, 4031 eyes) by about 30%, since the RR for gain was 0.75 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.94) and 0.68 (95% CI 0.53 to 0.86) versus ranibizumab and bevacizumab, respectively. The corresponding figures for mean BCVA change (21 studies, 2689 eyes) were a difference of 0.08 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.11) logMAR and 0.08 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.11) logMAR and were 38.90 (95% CI 2.27 to 75.52) micron and 68.32 (95% CI 28.69 to 107.96) micron for CRT change (16 studies, 3491 eyes), all favouring aflibercept.

Table 3.

Gain of 3 or more lines of visual acuity at 12 months: direct (upper‐right triangle) and mixed (lower‐left triangle) estimates

| LASER | 3.82 (2.61 to 5.58) | 2.74 (1.34 to 5.61) | 2.82 (1.82 to 4.38) | 1.88 (1.31 to 2.70) | 2.30 (1.74 to 3.03) | ||

| 3.66 (2.79 to 4.79) | AFLI | 0.68 (0.52 to 0.90) | 0.77 (0.59 to 0.99) | ||||

| 2.47 (1.81 to 3.37) | 0.68 (0.53 to 0.86) | BEVA | 1.14 (0.88 to 1.48) | ||||

| 1.70 (0.58 to 4.94) | 0.46 (0.16 to 1.34) | 0.69 (0.24 to 1.89) | PEGA | 0.51 (0.30 to 0.89) | |||

| 2.76 (2.12 to 3.59) | 0.75 (0.60 to 0.94) | 1.11 (0.87 to 1.43) | 1.62 (0.58 to 4.57) | RANI | 0.90 (0.67 to 1.21) | 0.31 (0.13 to 0.76) | |

| 2.02 (1.46 to 2.81) | 0.55 (0.37 to 0.82) | 0.82 (0.54 to 1.24) | 1.19 (0.40 to 3.58) | 0.73 (0.51 to 1.06) | RANI‐DL | 1.10 (0.80 to 1.51) | |

| 2.33 (1.81 to 3.00) | 0.64 (0.47 to 0.86) | 0.94 (0.68 to 1.31) | 1.37 (0.47 to 3.99) | 0.85 (0.65 to 1.09) | 1.15 (0.85 to 1.56) | RANI‐PL | |

| 0.87 (0.35 to 2.17) | 0.24 (0.10 to 0.59) | 0.35 (0.14 to 0.87) | 0.51 (0.30 to 0.89) | 0.32 (0.13 to 0.76) | 0.43 (0.17 to 1.11) | 0.37 (0.15 to 0.93) | SHAM |

P value for overall inconsistency = 0.883 in the network meta‐analysis.

Values in the table are risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Values in bold are ones where the 95% confidence intervals does not include 1 (null effect).

Table 4.

Mean visual acuity change at 12 months: direct (upper‐right triangle) and mixed (lower‐left triangle) estimates

| LASER | −0.20 (−0.24 to −0.17) | −0.20 (−0.28 to −0.12)a | −0.11 (−0.13 to −0.08) | −0.12 (−0.16 to −0.075) | −0.10 (−0.13 to −0.08) | ||

| −0.20 (−0.22 to −0.17) | AFLI | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.11) | 0.04 (0.00 to 0.08) | ||||

| −0.12 (−0.15 to −0.09)a | 0.08 (0.05 to 0.11) | BEVA | −0.02 (−0.05 to 0.01) | ||||

| 0.01 (−0.09 to 0.07) | 0.19 (0.11 to 0.27) | 0.11 (0.04 to 0.19) | PEGA | 0.08 (0.03 to 0.13) | |||

| −0.12 (−0.14 to −0.10) | 0.08 (0.05 to 0.11) | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.03) | −0.11 (−0.19 to −0.04) | RANI | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.03) | 0.23 (0.15 to 0.32) | |

| −0.11 (−0.13 to −0.09) | 0.08 (0.04 to 0.13) | 0.01 (−0.04 to 0.06) | −0.11 (−0.19 to −0.02) | 0.00 (−0.04 to 0.05) | RANI‐DL | 0.00 (−0.05 to 0.05) | |

| −0.11 (−0.14 to −0.08) | 0.09 (0.06 to 0.12) | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.05) | −0.10 (−0.18 to −0.02) | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) | 0.01 (−0.04 to 0.05) | RANI‐PL | |

| 0.08 (0.01 to 0.15) | 0.28 (0.21 to 0.35) | 0.20 (0.13 to 0.27) | 0.09 (0.06 to 0.12) | 0.20 (0.13 to 0.27) | 0.20 (0.11 to 0.28) | 0.19 (0.12 to 0.26) | SHAM |

a P value for differences between direct and indirect estimates = 0.031 in the network meta‐analysis.

P value for overall inconsistency = 0.665.

Table 5.

Mean central retinal thickness change at 12 months: direct (upper‐right triangle) and mixed (lower‐left triangle) estimates

| LASER | −119 (−143 to −95) | −44 (−82 to −5) | −71 (−120 to −22)^ | −35 (−62 to −8) | −64 (−103 to −25)b* | |

| −114 (−147 to −81) | AFLI | 68 (43 to 94) | 22 (−4 to 48) | |||

| −46 (−78 to −14) | 68 (29 to 108) | BEVA | −38 (−56 to −20) | 132 (72 to 187) | ||

| −75 (−100 to −50) | 39 (2 to 76) | −29 (−58 to −1) | RANI | −19 (−39 to 2)a | 1470 (95 to 196) | |

| −57 (−111 to −2) | 57 (−6 to 120) | −11 (−73 to 51) | 18 (−40 to 76) | RANI‐DL | 6 (−22 to 34) | |

| −72.90 (−103 to −42)b | 41 (−2 to 84) | −27 (−68 to 13) | 2 (−31 to 35)a | −16 (−71 to 38) | RANI‐PL | |

| 77 (18 to 137) | 191 (127 to 256) | 123 (67 to 179) | 153 (97 to 208) | 134 (55 to 213) | 150 (87 to 214) | SHAM |

a P value for differences between direct and indirect estimates = 0.003.

b P value for differences between direct and indirect estimates = 0.044.

* P value for heterogeneity = 0.002; I² = 80% in the direct meta‐analysis.

^ P value for heterogeneity = 0.000; I² = 91% in the direct meta‐analysis.

P value for overall inconsistency = 0.209 in the network meta‐analysis.

Ranibizumab and bevacizumab did not differ in term of functional outcomes: RR of gain 1.11 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.43) and difference in mean VA change 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.03) logMAR. However, CRT reduction favoured ranibizumab by −29.4 (95% CI −58.2 to −0.70) micron.

There was no evidence of overall statistical inconsistency in our efficacy analyses (Table 7; Table 8; Table 9). We found evidence of statistical inconsistency in one comparison (bevacizumab versus laser) for mean BCVA change and in the loop connecting ranibizumab, ranibizumab plus prompt laser and laser for mean CRT change, where two direct meta‐analyses also showed high heterogeneity in the same loop.

Mean risk of bias was low for mixed and direct comparisons among aflibercept, bevacizumab and ranibizumab for all efficacy outcomes, except for the comparison between bevacizumab and ranibizumab regarding mean BCVA change and mean CRT change, which were judged at unclear risk of bias (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Contribution plot of mean overall study risk of bias to pairwise network estimates. Legends show the risk of bias of each direct comparison.

We had not pre‐planned any subgroup analyses and were unable to obtain data to carry out post hoc subgroup analyses by baseline BCVA. DRCRnet 2015, the only large study comparing the three drugs, found that aflibercept was superior to bevacizumab and ranibizumab for participants with lower vision (69 ETDRS letter or less or approximately 20/50 or 0.4 logMAR or worse), whereas differences between the three drugs were unimportant for participants with better vision.

Efficacy at two years

Three publicly funded studies (BOLT 2010; DRCRnet 2010; DRCRnet 2015) and two industry‐sponsored studies (Macugen 2011; RISE‐RIDE) provided data at two years. There was only one study for each comparison, making data unsuitable for a network meta‐analysis.

Only DRCRnet 2015 (complete cases: aflibercept n = 201, bevacizumab n = 185, ranibizumab n = 191) compared different antiangiogenic drugs, and found no VA differences between ranibizumab 0.3 mg and aflibercept (gain 3+ VA lines, RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.22; difference in mean VA change 0.01, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.06). Ranibizumab and bevacizumab did not differ in terms of gain of 3 or more VA lines (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.24) but the difference in mean VA change favoured ranibizumab (mean difference −0.05, 95% CI −0.09 to 0.00), although it was not precisely estimated. Although effects on CRT favoured aflibercept over ranibizumab and ranibizumab over bevacizumab, none was statistically significant: mean difference −22 micron (95% CI −50 to 6 micron) and −23 micron (95% CI −52 to 6 micron) respectively.

We were unable to obtain data allowing subgroup analyses by baseline BCVA. DRCRnet 2015 found that such subgroup differences were attenuated at two years.

Safety at the longest available follow‐up

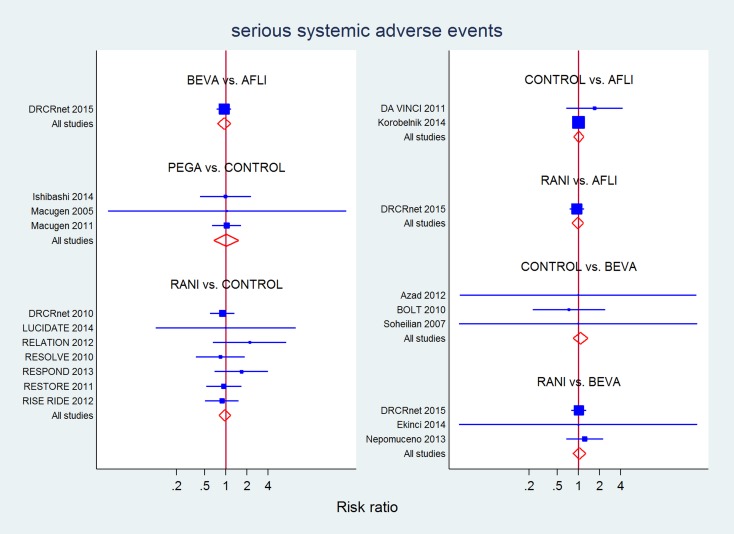

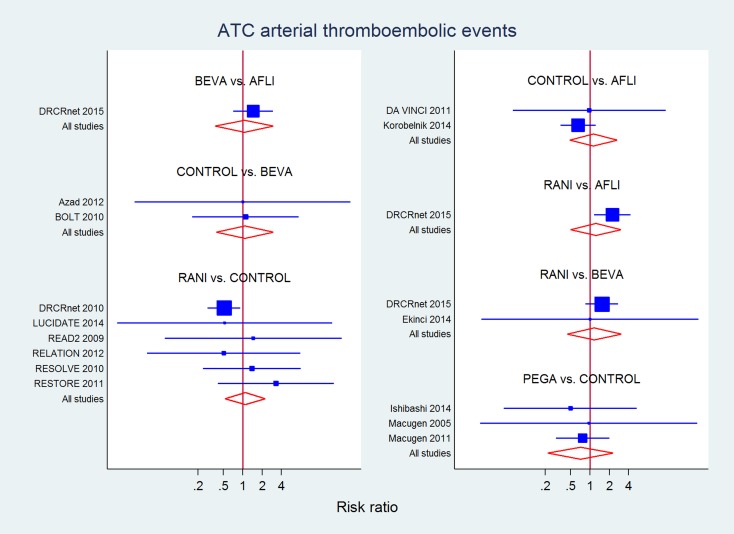

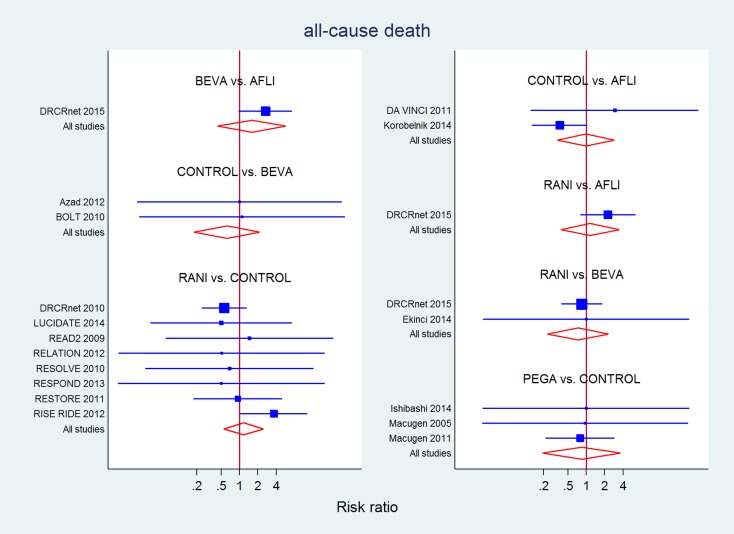

Table 10 presents the number of studies (participants/eyes) in the network for safety outcomes at the longest available follow‐up, and Figure 8 presents the corresponding network structure. Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 present forest plots for each study as well as their direct meta‐analysis and mixed estimates from the network meta‐analysis.

Table 6.

Network structure: safety at the longest available follow‐up

| Laser | Aflibercept | Bevacizumab | Pegaptanib | Ranibizumab | Sham | Overall | |

| SSAE | 9 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 18 |

| 1013 | 556 | 410 | 186 | 1303 | 528 | 4229 | |

| ATC* | 10 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 15 |

| 824 | 846 | 330 | 188 | 1113 | 184 | 3718 | |

| Death | 11 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 17 |

| 903 | 846 | 333 | 188 | 1521 | 434 | 4455 |

For each safety outcome, numbers in the table are the total number of studies (upper line for each outcome) and the total number of eyes (lower line for each outcome), as available by treatment and measured at the longest available follow‐up.

(*) combined incidence of (1) cardiovascular, hemorrhagic, and unknown death; (2) nonfatal MI; and (3) nonfatal stroke.

Figure 8.

Network structure for safety outcomes at 1 year

Figure 9.

All direct and mixed comparisons: serious systemic adverse events at the longest available follow‐up (1 or 2 years)

Figure 10.

All direct and mixed comparisons: arterial thromboembolic events at the longest available follow‐up (1 or 2 years)

Figure 11.

All direct and mixed comparisons: all‐cause death at the longest available follow‐up (1 or 2 years)

Two‐year data were available and reported in only four RCTs in this review. Most industry‐sponsored studies were open‐label after one year. Differently from efficacy analyses at one year, our safety analyses included data from RISE‐RIDE on ranibizumab with monthly treatments up to two years, as well as data from the monthly treatment arm (2q4) of Korobelnik 2014, which became PRN in the second year.

Though no analysis suggested a difference among drugs for any safety outcome, only estimates for SSAEs (18 studies, 4229 eyes) reached sufficient precision to exclude very large differences among drugs. Overall, no difference was detected in mixed evidence estimates for any drug compared to laser or sham. Moreover, RR 95% CI width excluded differences of 20% to 30% or more between aflibercept, bevacizumab and ranibizumab, while estimates for pegaptanib were less precise (Table 11). No overall (P = 0.86) or loop‐specific inconsistency was detected.

Table 7.

All serious systemic adverse events (longest available follow‐up)

| CONTROL | 0.95 (0.75 to 1.20) | 1.29 (0.43 to 3.84) | 1.02 (0.67 to 1.53) | 0.98 (0.76 to 1.25) |

| 0.98 (0.83 to 1.16) | AFLI | 0.95 (0.75 to 1.20) | 1.04 (0.83 to 1.32) | |

| 0.93 (0.73 to 1.19) | 0.95 (0.76 to 1.18) | BEVA | 0.96 (0.77 to 1.20) | |

| 1.02 (0.64 to 1.64) | 1.04 (0.63 to 1.72) | 1.09 (0.64 to 1.86) | PEGA | |

| 0.97 (0.80 to 1.17) | 0.98 (0.82 to 1.19) | 1.04 (0.84 to 1.28) | 0.95 (0.57 to 1.58) | RANI |

P value for overall inconsistency = 0.859.

Fifteen studies (3718 eyes) contributed to this analysis on 'Antiplatelet Trialists Collaboration arterial thromboembolic events' (Table 12). No difference was detected in mixed evidence estimates for any drug compared to laser or sham or between drugs, but estimates were very imprecise. No overall inconsistency was detected (P = 0.19), but direct evidence from DRCRnet 2015 showed increased risk for ranibizumab compared to aflibercept (RR 2.26, 95% CI 1.15 to 4.23) which was larger and inconsistent with indirect evidence (P = 0.002), resulting in mixed evidence showing no difference (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.50 to 3.05).

Table 8.

Antiplatelet Trialists Collaboration arterial thromboembolic events at the longest available follow‐up

| CONTROL | 1.50 (0.81 to 2.79) | 0.92 (0.17 to 5.12) | 0.78 (0.31 to 1.97) | 0.64 (0.38 to 1.07) |

| 0.88 (0.37 to 2.13) | AFLI | 1.46 (0.71 to 2.98) | 2.26 (1.15 to 4.23)a | |

| 0.94 (0.33 to 2.66) | 1.06 (0.36 to 3.11) | BEVA | 1.51 (0.85 to 2.69) | |

| 0.79 (0.20 to 3.02) | 0.89 (0.18 to 4.43) | 0.83 (0.15 to 4.61) | PEGA | |

| 1.09 (0.52 to 2.29) | 1.24 (0.48 to 3.19)a | 1.17 (0.43 to 3.13) | 1.17 (0.43 to 3.16) | RANI |

a P value for differences between direct and indirect estimates = 0.002.

P value for overall inconsistency = 0.274 in the network meta‐analysis.

Seventeen studies (4455 eyes) contributed to the analysis of 'all‐cause mortality' (Table 13). No difference was detected for direct, indirect and mixed evidence estimates for any drug compared to laser or sham or between drugs, but estimates were imprecise.

Table 9.

All‐cause mortality at the longest available follow‐up

| CONTROL | 1.69 (0.30 to 9.42)a | 0.95 (0.06 to 14.85) | 0.82 (0.25 to 2.65) | 0.64 (0.32 to 1.25)d |

| 1.01 (0.34 to 3.03)a | AFLI | 2.67 (0.97 to 7.37)b | 2.26 (0.80 to 6.40)c | |

| 1.61 (0.45 to 5.69) | 1.59 (0.43 to 5.94)b | BEVA | 0.85 (0.40 to 1.83) | |

| 0.81 (0.16 to 4.03) | 0.81 (0.12 to 5.62) | 0.51(0.07 to 3.90) | PEGA | |

| 0.90 (0.40 to 2.01) | 1.16 (0.38 to 3.58)c | 0.73 (0.22 to 2.37) | 1.44 (0.24 to 8.48) | RANI |

a P value for differences between direct and indirect estimates = 0.011.

b P value for differences between direct and indirect estimates = 0.030.

c P value for differences between direct and indirect estimates = 0.015.

d P value for differences between direct and indirect estimates = 0.022.

P value for overall inconsistency = 0.087 in the network meta‐analysis.

Mean risk of bias was low for mixed and direct comparisons between aflibercept and ranibizumab and unclear for bevacizumab versus ranibizumab for SSAEs. Regarding ATC arterial thromboembolic events and all‐cause death, risk of bias was low for aflibercept versus ranibizumab but it was unclear or high for bevacizumab versus ranibizumab (Figure 7).

Quality of the evidence

See above for the discussion of risk of bias of mixed evidence in pairwise comparisons of interest.

Statistical heterogeneity between studies

When a direct meta‐analysis was possible, no heterogeneity of effects was found for the following outcomes: gain of 3 or more BCVA lines, mean BCVA change, SSAEs, ATC arterial thrombembolic events, death. As reported above, there was high heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis of change in CRT for the comparisons of ranibizumab with laser (I² = 91%) and ranibizumab plus deferred laser versus laser (I² = 80%), but not in other two meta‐analyses in this network.

Estimates of between‐study standard deviation τ in the network meta‐analyses suggested little heterogeneity for dichotomous outcomes, except for ATC arterial thrombembolic events when it was moderate (τ = 0.51) . Values for BCVA change and CRT change were 8‐10 logMAR and 27 micron, respectively. These values mean that heterogeneity was negligible for VA change, but was compatible with a predictive intervals width increased by at least 100 micron for the CRT change.

Similarity between studies