Abstract

Background

Various nerve blocks with local anaesthetic agents have been used to reduce pain after hip fracture and subsequent surgery. This review was published originally in 1999 and was updated in 2001, 2002, 2009 and 2017.

Objectives

This review focuses on the use of peripheral nerves blocks as preoperative analgesia, as postoperative analgesia or as a supplement to general anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery. We undertook the update to look for new studies and to update the methods to reflect Cochrane standards.

Search methods

For the updated review, we searched the following databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 8), MEDLINE (Ovid SP, 1966 to August week 1 2016), Embase (Ovid SP, 1988 to 2016 August week 1) and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCO, 1982 to August week 1 2016), as well as trial registers and reference lists of relevant articles.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving use of nerve blocks as part of the care provided for adults aged 16 years and older with hip fracture.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed new trials for inclusion, determined trial quality using the Cochrane tool and extracted data. When appropriate, we pooled results of outcome measures. We rated the quality of evidence according to the GRADE Working Group approach.

Main results

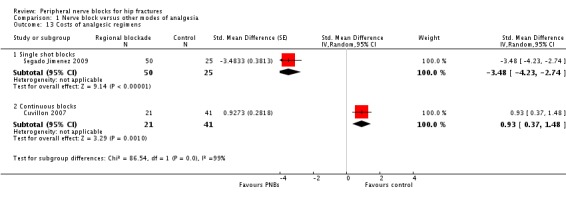

We included 31 trials (1760 participants; 897 randomized to peripheral nerve blocks and 863 to no regional blockade). Results of eight trials with 373 participants show that peripheral nerve blocks reduced pain on movement within 30 minutes of block placement (standardized mean difference (SMD) ‐1.41, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐2.14 to ‐0.67; equivalent to ‐3.4 on a scale from 0 to 10; I2 = 90%; high quality of evidence). Effect size was proportionate to the concentration of local anaesthetic used (P < 0.00001). Based on seven trials with 676 participants, we did not find a difference in the risk of acute confusional state (risk ratio (RR) 0.69, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.27; I2 = 48%; very low quality of evidence). Three trials with 131 participants reported decreased risk for pneumonia (RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.89; I2 = 3%; number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) 7, 95% CI 5 to 72; moderate quality of evidence). We did not find a difference in risk of myocardial ischaemia or death within six months, but the number of participants included was well below the optimal information size for these two outcomes. Two trials with 155 participants reported that peripheral nerve blocks also reduced time to first mobilization after surgery (mean difference ‐11.25 hours, 95% CI ‐14.34 to ‐8.15 hours; I2 = 52%; moderate quality of evidence). One trial with 75 participants indicated that the cost of analgesic drugs was lower when they were given as a single shot block (SMD ‐3.48, 95% CI ‐4.23 to ‐2.74; moderate quality of evidence).

Authors' conclusions

High‐quality evidence shows that regional blockade reduces pain on movement within 30 minutes after block placement. Moderate‐quality evidence shows reduced risk for pneumonia, decreased time to first mobilization and cost reduction of the analgesic regimen (single shot blocks).

Plain language summary

Local anaesthetic nerve blocks for people with a hip fracture

Background: Peripheral nerve blocks consist of an injection of local anaesthetics close to the nerves to transiently block pain transmission to the brain. This review examined evidence from randomized controlled trials that evaluated the use of peripheral nerve blocks to manage pain for people with a hip fracture.

Search dates: This is an update of a previously published review. We updated the search in August 2016.

Study characteristics: We included 31 trials (1760 adult participants: 897 randomized to peripheral nerve blocks and 863 to no regional blockade) performed in various countries and published between 1980 and 2016.

Study funding sources: Trials were funded by a charitable organization (n = 3), by a governmental organization (n = 1) or by departmental resources (n = 5), or did not specify the source of funding.

Key results: Compared with other modes of analgesia, peripheral nerve blocks used to treat hip fracture pain reduce pain on movement better within 30 minutes (equivalent to a difference of ‐3.4 on a scale from 0 to 10 between the two analgesic regimens). The risk of pneumonia is also reduced when peripheral nerve blocks are used to treat hip fracture pain. For every 7 people with a hip fracture, one less person will suffer from pneumonia. Studies noted no major complications related to peripheral nerve blocks and reported reduced time to first mobilization after hip fracture surgery (approximately 11 hours earlier). We did not identify enough trial participants to determine if regional blockade makes a difference in terms of acute confusion, myocardial ischaemia and death within six months after surgery. Peripheral nerve block given as a single injection led to reduced cost of analgesic drugs.

Quality of evidence: We rated the quality of evidence as high for reduction of pain on movement within 30 minutes, and as moderate for pneumonia, time to first mobilization and costs of analgesic drugs. We would need more information before we could draw final conclusions on effects of peripheral nerve blocks on the risk of acute confusional state, myocardial ischaemia and mortality.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Peripheral nerve blocks for hip fracture.

| Peripheral nerve blocks for hip fracture | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with hip fracture Settings: trials performed in Argentina (n = 1), Austria (n = 1), Chile (n = 1), China (n = 2), Denmark (n = 2), France (n = 2), Geece (n = 3), Germany (n = 1), India (n = 1), Iran (n = 1), Ireland (n = 1), Israel (n = 1), Korea (n = 1), South Africa (n = 1), Spain (n = 2), Sweden (n = 1), Thailand (n = 1), Turkey (n = 2), United Kingdom (n = 5) and United States of America (n = 1) Intervention: peripheral nerve blocks Comparison: systemic analgesia | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Systemic analgesia | Peripheral nerve blocks | |||||

| Pain on movement at 30 minutes after block placement Follow‐up: 20‐30 minutes | Mean pain on movement at 30 minutes after block placement in the intervention groups was 1.41 standard deviations lower (2.14 to 0.67 lower) | 373 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ higha,b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i | Equivalent to ‐ 3.4 on a scale from 0 to 10 | ||

| Acute confusional state | Study population | RR 0.69 (0.38 to 1.27) | 676 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowc,f,h,j,k,l,m,n | ||

| 198 per 1000 | 136 per 1000 (75 to 251) | |||||

| Low | ||||||

| 150 per 1000 | 104 per 1000 (57 to 190) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 250 per 1000 | 172 per 1000 (95 to 317) | |||||

| Myocardial ischaemia | Study population | RR 0.2 (0.03 to 1.42) | 20 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowb,c,j,m,n,o,p,q | ||

| 500 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (15 to 710) | |||||

| Low | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (3 to 142) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 500 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (15 to 710) | |||||

| Pneumonia | Study population | RR 0.41 (0.19 to 0.89) | 131 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatec,f,h,k,l,n,r,s,t | ||

| 269 per 1000 | 110 per 1000 (51 to 239) | |||||

| Low | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (9 to 44) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 82 per 1000 (38 to 178) | |||||

| Death Follow‐up: 0‐6 months | Study population | RR 0.72 (0.34 to 1.52) | 316 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowc,f,m,n,o,q,s,u | ||

| 98 per 1000 | 70 per 1000 (33 to 149) | |||||

| Low | ||||||

| 25 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (9 to 38) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 150 per 1000 | 108 per 1000 (51 to 228) | |||||

| Time to first mobilisation | Mean time to first mobilisation in intervention groups was 11.25 hours lower (14.34 to 8.15 lower) | 155 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea,c,d,e,h,k,n,p,s,v,w | |||

| Cost of analgesic regimens for single shot blocks | Mean cost of analgesic regimens for single shot blocks in intervention groups was 3.48 standard deviations lower (4.23 to 2.74 lower) | 75 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea,c,l,n,p,q,s,v | |||

| The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

a50% or more of studies were rated as having unclear or high risk for allocation concealment or blinding of outcome assessor bWe did not downgrade the evidence on inconsistency because we found a reasonable explanation for heterogeneity cDirect comparisons in studies performed on the population of interest and the outcome measured is not a surrogate marker dOptimal information size achieved eWide confidence interval around effect size fNo evidence of publication bias, or applying a correction for the possibility of one would not modify the conclusion gLarge effect size (SMD > 0.8) hNo study used ultrasound guidance, which could have increased success rate of blocks iEffect size was proportional to the concentration of local anaesthetic used in lidocaine equivalent j75% of studies or more were judged at unclear or high risk of bias for allocation concealment or blinding of outcome assessor kModerate amount of heterogeneity or clinical heterogeneity lOptimal information size not achieved mNo evidence of a large effect nNo evidence of a dose response oEstimate included both absence of effect and important benefit pCould not be assessed qNo evidence of confounding factors that would justify upgrading rGroups heterogenous for preoperative characteristics sNo heterogeneity or ≤ 25% tWe upgraded the level of evidence by one owing to a large effect size (RR < 0.5) uWe did not downgrade for risk of bias vWe upgraded the level of evidence on the basis of a large effect size (equivalent to SMD > 0.8) wWe upgraded the level of evidence on the basis of a large effect size (equivalent to SMD of ‐1.87)

Background

Description of the condition

Among women aged 55 years and older in the USA, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) for 2000 to 2010 reported 4.9 million hospitalizations for osteoporotic fractures (2.6 million for hip fractures), 2.9 million for myocardial infarction, 3.0 million for stroke and 0.7 million for breast cancer (Singer 2015). Osteoporotic fractures accounted for more than 40% of hospitalizations for these four outcomes, with an age‐adjusted rate of 1124 admissions per 100,000 person‐years. The annual total population facility‐related hospital cost was highest for hospitalizations due to osteoporotic fractures (USD 5.1 billion), followed by myocardial infarction (USD 4.3 billion), stroke (USD 3.0 billion) and breast cancer (USD 0.5 billion) (Singer 2015). Costs of care for hip fractures are high and, when both acute care and the care needed for subsequent dependency were included, exceeded GBP 2 billion in 2012 for the UK as a whole. That same year, the overall rate of return home by 30 days was 44.6% in the UK (http://www.nhfd.co.uk/20/hipfractureR.nsf/). In the USA, from 2003 to 2005, 5.3% (95% confidence interval (CI) 5.2% to 5.4%) of patients with hip fracture returned home in 30 days , and 52.8% of patients with hip fracture (95% CI 52.5% to 53.2%) were discharged to a skilled nursing facility (Brauer 2009). Hip fractures reduce life expectancies when they occur in individuals over 50 years of age. Pooled data from cohort studies revealed that the relative hazard for all‐cause mortality during the first three months after hip fracture was 5.75 (95% CI 4.94 to 6.67) in women and 7.95 (95% CI 6.13 to 10.30) in men (Haentjens 2010).

The term 'hip fracture' refers to a fracture of the proximal femur down to about 5 cm below the lower border of the lesser trochanter.

Description of the intervention

Regional blockade refers to injection of local anaesthetics around neural structures to transiently prevent pain transmission to the brain and may also produce motor blockade of the muscle in a specific area, depending on the type and concentration of local anaesthetic used. Local anaesthetics can be used at the spine level (neuraxial block = epidural or spinal) or around the nerves outside the spine (plexus blocks or peripheral nerve blocks). Local anaesthetic may also be infiltrated directly into wound tissues. All of these blocks can be given as single injections or by continuous infusion through a catheter to prolong their beneficial effects. Regional blockade may be used as a replacement for general anaesthesia during surgery, as adjunctive treatment for preoperative and postoperative pain or to decrease the use of intraoperative systemic drugs during general anaesthesia. Use of regional blockade as a replacement for general anaesthesia is treated in another review (Guay 2016).

How the intervention might work

Most hip fractures occur in an elderly population; more than 30% of individuals are 85 years of age or older (Brauer 2009). Opioid‐related respiratory depression may result in severe brain damage or death (Lee 2015). By reducing the quantity of opioids used before, during and after surgery (Guay 2006), regional blockade may improve the mobility of persons with hip fracture (Saunders 2010), potentially facilitating person's participation in rehabilitation.

Why it is important to do this review

Despite their claim advantages, peripheral nerve blocks still are not widely used for people with hip fracture (Haslam 2013). We therefore decided to re‐evaluate the beneficial/harmful effects of peripheral nerve blocks for hip fracture.

This is an update of a previously published review (Parker 2002).

Objectives

This review focuses on the use of peripheral nerve blocks as preoperative analgesia, as postoperative analgesia or as a supplement to general anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery. We undertook the update to look for new studies and to update the methods to reflect Cochrane standards.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomized controlled trials comparing peripheral nerve blocks inserted preoperatively, operatively or postoperatively versus no regional blockade (control group).

We excluded quasi‐randomized trials (e.g. alternation).

Types of participants

We included adults aged 16 years of age and older with a proximal femoral fracture (hip fracture).

Types of interventions

Peripheral nerve blocks of any type versus no regional blockade added to general or neuraxial anaesthesia.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Pain (study author's scale) at rest and on movement 30 minutes after block placement and at 6 to 8, 24, 48 and 72 hours after surgery

Acute confusional state (study author's definition and time points)

Myocardial infarction (study author's definition and time points)

Secondary outcomes

Pneumonia (study author's definition and time points)

Mortality (all death from any cause at any time points chosen by study authors)

Time to first mobilization after surgery

Costs of analgesic regimens (at any time points chosen by study authors)

Pressure sores (study author's definition and time points)

Number of participants transfused in hospital

Myocardial ischaemia (study author's definition and time points)

Opioid consumption in hospital up to 48 hours

Wound infection (study author's definition in hospital)

Participant satisfaction (study author's scale)

Complications related to pain treatment in hospital

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 8), MEDLINE (Ovid SP, 1966 to August week 1 2016), Embase (Ovid SP, 1988 to August week 1 2016) and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCO, 1982 to August week 1 2016). We applied no language or publication status restrictions.

For MEDLINE (Ovid SP), we designed a subject‐specific search strategy and used this as a basis for search strategies used in Embase, CENTRAL and CINAHL. When appropriate, we supplemented the search strategy with search terms used to identify randomized controlled trials. All search strategies can be found in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We also looked at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (May 2015), http://isrctn.org (May 2015), http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index.htm (May 2015), http://www.anzctr.org.au (May 2015), http://www.trialregister.nl/ (May 2015) and http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/ (May 2015) to identify trials in progress. We screened the reference lists of all studies retained (during data extraction) and from the recent meta‐analysis and reviews related to the topic (June 2015). We also screened conference proceedings of anaesthesiology societies for 2012, 2013 and 2014, published in three major anaesthesiology journals: British Journal of Anaesthesiology (May 2015), European Journal of Anaesthesiology (May 2015) and Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (May 2015). We looked for abstracts on the website of the American Society of Anesthesiologists for the same years (2012 to 2014; http://www.asaabstracts.com/strands/asaabstracts/search.htm;jsessionid=4A977E1C98F0AE8995CFF248FE862490) (May 2015).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (JG and SK) independently assessed potentially eligible trials for inclusion. We resolved disagreements by discussion.

Data extraction and management

At least two review authors (JG and SK) independently extracted data for the outcomes listed above for all new trials and resolved differences through discussion. For trials included in the previously published version (Parker 2002), one review author (JG) double‐checked all data against the original articles. When we were unable to extract the data in any form, we contacted the study authors for whom we could find an email address.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (JG and SK) evaluated all included studies for risk of bias using the Cochrane tool (Higgins 2011) and entered this information into RevMan. We resolved all differences by discussion. When reports did not provide enough information, we judged the item as unclear.

Measures of treatment effect

We presented results as risk ratio (RR) or risk difference (RD) along with the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for dichotomous data, and as mean difference (MD) and 95% CI for continuous data. If some of the continuous data were given on different scales, or when results were not provided as mean and standard deviation (SD) (therefore extracted as P values), we produced the results as standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI. For SMD, we considered 0.2 a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect and 0.8 a large effect (Pace 2011). When data showed an effect, we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) using the odds ratio. We provided results for dichotomous data as RR as often as was feasible, as the odds ratio (OR) is not easily understood by clinicians (Deeks 2002; McColl 1998). We used OR for calculation of NNTB and NNTH (http://www.nntonline.net/visualrx/), as this value is less likely to be affected by the side (benefit or harm) on which data are entered (Cates 2002; Deeks 2002). When we noted no effect, we calculated the optimal information size to make sure that enough participants were included in the retained studies to justify a conclusion on the absence of effect (Pogue 1998) (http://www.stat.ubc.ca/˜rollin/stats/ssize/b2.html). We considered a difference of 25% (increase or decrease) as the minimal clinically relevant difference.

Unit of analysis issues

We included only parallel‐group trials. If a trial included more than two groups, we fused two groups (by using the appropriate formula for adding standard deviations when required) when we thought that they were equivalent according to the criteria chosen a priori for heterogeneity exploration; we separated them and split the control group in half if we thought that they were different.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to ask for apparently missing data. We did not consider medians as equivalent to means. Instead, we used the P value and the number of participants included in each group to calculate the effect size. We did not use imputed results. We entered data as intention‐to‐treat (ITT) as much as was feasible. If this was not possible, we entered the data on a per‐protocol basis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered clinical heterogeneity before pooling results and examined statistical heterogeneity before carrying out any meta‐analysis. We quantified statistical heterogeneity by using the I2 statistic with data entered in the way (benefit or harm) that yielded the lowest amount. We qualified the amount as low (< 25%), moderate (50%) or high (75%), depending on the value obtained for the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

We examined publication bias by using a funnel plot, then performed Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill technique for each outcome. When publication bias is present, this technique yields an adjusted point of estimate that takes into account the number of theoretically missing studies.

Data synthesis

We analysed the data using RevMan 5.3 and ComprehensiveMeta‐Analysis Version 2.2.044 (www.Meta‐Analysis.com) with fixed‐effect (I2 ≤ 25%) or random‐effects models (I2 > 25%). We presented study characteristics in relevant tables (Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies). We presented risk of bias assessments in graphs and results for each comparison as forests plots or as a narrative review (comparisons with fewer than two available trials or with a high level of heterogeneity after heterogeneity exploration).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We focused specifically on comparisons with more than a small amount of heterogeneity (I2 > 25%) (Higgins 2003) and explored heterogeneity by using Egger’s regression intercept (to assess the possibility of a small‐study effect; Rucker 2011); by visually inspecting forest plots with trials placed in order according to a specific moderator, by subgrouping (categorical moderator) or by meta‐regression (continuous moderator). We considered the following factors when exploring heterogeneity: type of block (psoas compartment, fascia iliaca, femoral nerve (we considered three‐in‐one and triple nerve blocks as femoral nerve blocks), femoral lateral cutaneous, obturator etc.), single shot versus continuous block (and duration of use), technique of localization (landmark, nerve stimulator or ultrasound), local anaesthetic concentration in lidocaine equivalent (calculated as follows: lidocaine = 1, bupivacaine = 4, chloroprocaine = 1.5, dibucaine = 4, etidocaine = 4, levobupivacaine = 3.9, mepivacaine = 0.8, prilocaine = 0.9, procaine = 0.5, ropivacaine = 3 and tetracaine = 4) (Berde 2009), time when the block was performed in relation to surgery, ages of participants included, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status of participants, year the study was published, delay from fracture (or hospital admission) to surgery, percentage of female participants, percentage of arthroplasty among participants and route of analgesia in the control group.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis that was based on risk of bias of the study or, if a study was a clear outlier as long as a reason differentiating this study from the other studies could be found.

Quality of evidence and summary of findings

We used the principles of the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008; Guyatt 2011) to assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with all of our primary outcomes (pain on movement 30 minutes after block placement, acute confusional state, myocardial infarction, pneumonia, death, time to first mobilization and cost of analgesic regimen for single shot blocks) and constructed Table 1 using GradePro (http://tech.cochrane.org/revman/gradepro). For risk of bias, we judged the quality of the evidence as presenting low risk of bias when most information came from studies at low risk of bias; we downgraded quality by one level when most information came from studies at high or unclear risk of bias (allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors) and by two levels when the proportion of information from studies at high risk of bias was sufficient to affect interpretation of results. For inconsistency, we downgraded the quality of evidence by one when the I2 statistic was 50% or higher without satisfactory explanation, and by two levels when the I2 statistic was 75% or higher without an explanation. We considered clinical heterogeneity as a factor for inconsistency. We did not downgrade the quality of evidence for indirectness, as all outcomes were based on direct comparisons, were performed on the population of interest and were not surrogate markers (Guyatt 2011a). For imprecision (Guyatt 2011b), we downgraded the quality of evidence by one when the CI around the effect size was large or overlapped with absence of effect and failed to exclude an important benefit or harm (when the number of participants was lower than the optimal information size); and we downgraded quality by two levels when the CI was very wide and included both appreciable benefit and harm. For publication bias, we downgraded the quality of evidence by one when correcting for the possibility of publication bias as assessed by Duval and Tweedie’s fill and trim analysis changed the conclusion. We upgraded the quality of evidence by one when the effect size was large (RR ≤ 0.5 or ≥ 2.0), and by two when the effect size was very large (RR ≤ 0.2 or ≥ 5) (Guyatt 2011c). We applied the same rules for OR when the basal risk was less than 20%. For SMD, we used 0.8 as the cutoff point for a large effect (Pace 2011). We also upgraded the quality by one when we found evidence of a dose‐related response. The quality was upgraded by one when a possible effect of confounding factors would reduce a demonstrated effect or suggest a spurious effect if results show no effect. When the quality of the body of evidence is high, further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. When the quality is moderate, further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. When the quality is low, further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. When the quality is very low, any estimate of effect is very uncertain (Guyatt 2008).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

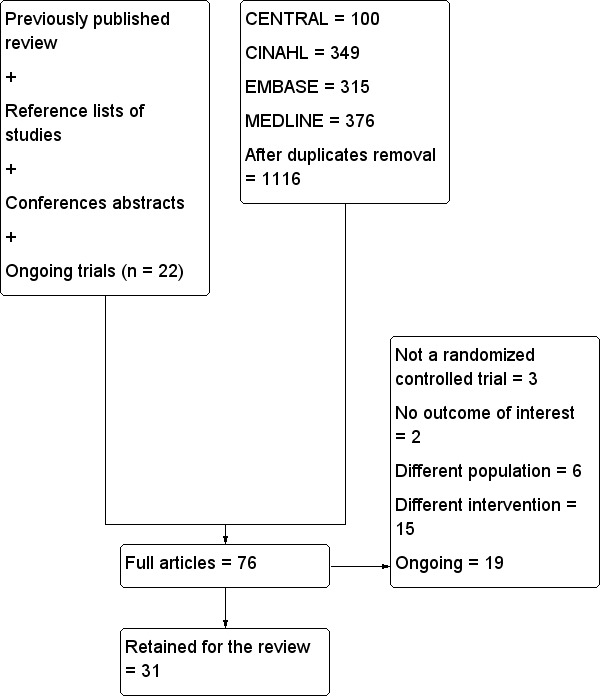

Details of the search for this update can be found in Figure 1.

1.

Flow diagram for this update.

n: number.

Included studies

We included 31 trials with 1760 participants: 897 randomized to regional blockade and 863 to no regional blockade. Trials published between 1980 and 2016 were funded by a charitable organization (n = 3; Beaudoin 2013; Cuvillon 2007; Foss 2007), by a governmental organization (n = 1; Nie 2015) or by departmental resources (n = 5; Domac 2015; Gille 2006; Jones 1985; Kullenberg 2004; Luger 2012). Remaining trials did not specify the source of funding. Trials were performed in Argentina (n = 1; Godoy 2010), Austria (n = 1; Luger 2012), Chile (n = 1; Altermatt 2013), China (n = 2; Graham 2008; Nie 2015), Denmark (n = 2; Foss 2007; Spansberg 1996), France (n = 2; Cuvillon 2007; Murgue 2006), Greece (n = 3; Antonopoulou 2006; Diakomi 2014; Mouzopoulos 2009), Germany (n = 1; Gille 2006), India (n = 1; Jadon 2014), Iran (n = 1; Mossafa 2005), Ireland (n = 1; Szucs 2012), Israel (n = 1; Chudinov 1999), Korea (n = 1; Yun 2009), South Africa (n = 1; White 1980), Spain (n = 2; De La Tabla 2010; Segado Jimenez 2009), Sweden (n = 1; Kullenberg 2004), Thailand (n = 1; Iamaroon 2010), Turkey (n = 2; Domac 2015; Tuncer 2003), United Kingdom (n = 5; Coad 1991; Fletcher 2003; Haddad 1995; Hood 1991; Jones 1985) and United States of America (n = 1; Beaudoin 2013). Participants were aged from 59.2 to 88 years (mean or median age of participants included in retained studies) and had an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status between 1.75 and 2.87; the proportion of females included varied between 27% and 95%. The proportion of arthroplasty varied between 0 and 82.5%. Delay from admission to surgery varied between 11 and 283 hours.

Blocks performed included a femoral nerve block (femoral or three‐in‐one block or triple nerve block) (Beaudoin 2013; Coad 1991; Cuvillon 2007; De La Tabla 2010; Fletcher 2003; Gille 2006; Graham 2008; Haddad 1995; Iamaroon 2010; Jadon 2014; Kullenberg 2004; Luger 2012; Murgue 2006; Spansberg 1996; Szucs 2012; Tuncer 2003), a femoral nerve block plus an infiltration above the iliac crest (Hood 1991), a fascia iliaca compartment block (Diakomi 2014; Domac 2015; Foss 2007; Godoy 2010; Mossafa 2005; Mouzopoulos 2009; Nie 2015; Yun 2009), a lateral cutaneous nerve block (Coad 1991; Jones 1985), a lateral cutaneous nerve block plus an obturator nerve block (Segado Jimenez 2009), an obturator nerve block (Segado Jimenez 2009) and a psoas compartment block (Altermatt 2013; Chudinov 1999; White 1980). Blocks were single shot blocks or continuous blocks (infusion or repeated) (Altermatt 2013; Chudinov 1999; Cuvillon 2007; De La Tabla 2010; Gille 2006; Luger 2012; Mouzopoulos 2009; Nie 2015; Spansberg 1996; Szucs 2012; Tuncer 2003) given for a duration ranging from 15 to 92 hours. Techniques of localization used for peripheral nerve blocks included loss of resistance (Chudinov 1999), use of nerve stimulator (Cuvillon 2007; Gille 2006; Graham 2008; Hood 1991; Iamaroon 2010; Jadon 2014; Kullenberg 2004; Spansberg 1996; Szucs 2012; Tuncer 2003), paraesthesia (Haddad 1995), ultrasound (Beaudoin 2013; De La Tabla 2010; Luger 2012) and landmarks (Coad 1991; Diakomi 2014; Domac 2015; Fletcher 2003; Foss 2007; Godoy 2010; Jones 1985; Mossafa 2005; Mouzopoulos 2009; Nie 2015; Segado Jimenez 2009; White 1980). Investigators performed blocks before surgery (Altermatt 2013; Beaudoin 2013; Chudinov 1999; De La Tabla 2010; Diakomi 2014; Domac 2015; Fletcher 2003; Foss 2007; Gille 2006; Godoy 2010; Graham 2008; Haddad 1995; Iamaroon 2010; Jadon 2014; Kullenberg 2004; Luger 2012; Mossafa 2005; Mouzopoulos 2009; Murgue 2006; Szucs 2012; Yun 2009), intraoperatively (Hood 1991; Spansberg 1996; Tuncer 2003; White 1980) or after surgery (Coad 1991; Cuvillon 2007; Jones 1985; Nie 2015; Segado Jimenez 2009). Concentrations of local anaesthetic used in the lidocaine equivalent ranged from 5 to 22.5 mg/mL.

Details of the blocks and of anaesthetic techniques used for the surgery are included in Table 2.

1. Anaesthetic techniques.

| Study | Purpose of blockade | Surgical anaesthesia | Block technique | Comparison |

| Altermatt 2013 | Preoperative and postoperative analgesia | Unspecified | Continuous lumbar plexus with 0.1% bupivacaine in a patient‐controlled analgesia mode | IV morphine |

| Antonopoulou 2006 | Postoperative analgesia | Spinal anaesthesia | Continuous femoral nerve block, nerve stimulator, loaded with 18 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine followed by an infusion of 0.125% levobupivacaine at 3‐4 mL/h | IM pethidine |

| Beaudoin 2013 | Preoperative analgesia | Unspecified | Ultrasound‐guided femoral nerve block performed by an experienced operator with a 7.5 MHz linear probe, participant in Trendelenburg position, cross‐sectional view, 22 G Whitacre needle in‐plane and 25 mL of bupivacaine 0.5% and distal manual pressure for 5 minutes | IM morphine |

| Chudinov 1999 | Preoperative and postoperative analgesia Surgery for some participants |

Treatment group: psoas block alone (3/20) with a sciatic block (5/20), a spinal (11/20) or general anaesthesia (1/20) Control group: neuraxial block (19/20) or general anaesthesia (1/20). |

Psoas, loss of resistance, Chayen's technique 0.8 mL/kg of bupivacaine 0.25%, operated side up (1 epidural spread) | IM meperidine and diclofenac |

| Coad 1991 | Postoperative analgesia | General anaesthesia for all participants with etomidate, nitrous oxide, enflurane, fentanyl and vecuronium | Lateral cutaneous: 15 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine, Eriksson's technique Femoral (3‐in‐1): 15 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine, Winnie's technique |

IM meperidine |

| Cuvillon 2007 | Postoperative analgesia | Spinal anaesthesia for all participants | Continuous femoral nerve block. Nerve stimulator 0.3 to 0.5 mA. Non‐stimulating catheter passed 10‐15 cm past the needle tip loaded with 30 mL of 1.5% lidocaine followed by ropivacaine 0.2% at 10 mL/h for 48 hours | SC morphine |

| De La Tabla 2010 | Preoperative analgesia | Unspecified | Femoral nerve block under dual guidance (ultrasound and nerve stimulator), catheter loaded with 15 mL of ropivacaine 0.2% followed by an infusion of the same solution at 5 mL/h and 10 mL every 30 minutes | IV metamizole and tramadol |

| Diakomi 2014 | Preoperative analgesia (spinal positioning) | Spinal anaesthesia | Fascia iliaca block, Dalen's technique, landmarks, 40 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine | IV fentanyl |

| Domac 2015 | Preoperative analgesia (spinal positioning) plus postoperative analgesia | Spinal anaesthesia | Fascia iliaca block with 15 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine and 15 mL of 2% lidocaine; 2‐3 cm below inguinal ligament at the junction of lateral 1/3 and medial 2/3 of a line from pubis tubercle to anterior iliac spine; 2 pops | IV morphine |

| Fletcher 2003 | Preoperative analgesia | Unspecified | Fermoral (3‐in‐1 nerve block, Wiinie's technique with 20 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine and 5 minutes distal compression) | IV morphine |

| Foss 2007 | Preoperative analgesia | Unspecified | Fascia iliaca block based on Dalen's landmarks with a 24 G blunted needle and 40 mL of 1% mepivacaine with epinephrine | IM morphine |

| Gille 2006 | Preoperative and postoperative analgesia |

Treatment group: spinal anaesthesia for 37/50 and general anaesthesia for 13/50 Control group: spinal anaesthesia for 38/50 and general anaesthesia for 12/50 |

Femoral non‐stimulating catheter: needle 18 G, catheter 20 G (Brown‐Perifix‐Plexus Anaesthesia); 0.5 mA and 0.1 msec. Catheters were advanced about 10 cm past the needle tip and fixed. Loading dose was 40 mL of prilocaine 1% followed 2 hours later by ropivacaine 0.2% 30 mL, repeated every 6 hours. Amount (up to 40 mL; n = 5) and intervals (up to every 4 hours; n = 8) or both (n = 6) adjusted on pain scores | IV metamizole plus oral tilidine and naloxone |

| Godoy 2010 | Preoperative analgesia | Unspecified | Fascia iliaca compartment block, 21G long bevel needle, Dalen's technique with 0.3 mL/kg of 0.25% bupivacaine | IV non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs |

| Graham 2008 | Preoperative analgesia | Unspecified | Femoral (3‐in‐1) nerve block, Winnie's technique, nerve stimulator and 30 mL of bupivacaine 0.5% (not exceeding 3 mg/kg) | IV morphine |

| Haddad 1995 | Preoperative analgesia | Unspecified | Femoral nerve block with 0.3 mL/kg of bupivacaine 0,25%. Paraesthesia technique with a short bevel needle | IM pethidine, oral co‐dydramol and IM voltarol |

| Hood 1991 | Postoperative analgesia | General anaesthesia for all participants with etomidate, nitrous oxide, isoflurane and alfentanil | Femoral nerve block (triple nerve block) with nerve stimulator < 1.0 mA and 35 mL of prilocaine 0.75% and distal digital pressure plus infiltration above the iliac crest with 8 mL of the same solution | IM papaveratum |

| Iamaroon 2010 | Preoperative analgesia | Spinal anaesthesia | Femoral nerve block with nerve stimulator (0.2 to 0.4 mA) and 20 mL of bupivacaine 0.5% plus 10 mL of saline | IV fentanyl |

| Jadon 2014 | Preoperative analgesia | Spinal anaesthesia | Femoral nerve block with nerve stimulator (0.3 to 0.5 mA) and 15 mL of lidocaine 2% plus 5 mL of distilled water | IV fentanyl |

| Jones 1985 | Postoperative analgesia | General anaesthesia for all participants with thiopental, nitrous oxide, halothane, fentanyl and alcuronium | Lateral cutaneous nerve block with 15 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine, Eriksson's technique | IM pethidine |

| Kullenberg 2004 | Preoperative analgesia | Unspecified | Femoral nerve block with 30 mL of 0.75% ropivacaine. Winnie's approach and nerve stimulator | IM ketobemidon plus tramadol and paracetamol |

| Luger 2012 | Preoperative and postoperative analgesia | Spinal anaesthesia | Ultrasound‐guided femoral (3‐in‐1) nerve block (13‐6 MHz linear probe), catheter inserted ≥ 12‐15 cm past the needle tip) loaded with 30 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine followed by an infusion of 0.125% bupivacaine at 6 mL/h (motor blockade not evaluated) or Lumbar epidural analgesia with 0.125% bupivacaine at 8 mL/h |

IV/SC piritramide or IV paracetamol |

| Mossafa 2005 | Preoperative analgesia | Spinal anaesthesia | Fascia iliaca block with 20 mL of 1.5% lidocaine | IV fentanyl |

| Mouzopoulos 2009 | Preoperative and postoperative analgesia | Epidural anaesthesia | Fascia iliaca block daily, Dalen's technique with 0.3 mL/kg of bupivacaine (0.25%?) | IV and analgesics |

| Murgue 2006 | Preoperative analgesia | Unspecified | Femoral nerve block with nerve stimulator and 20 mL of mepivacaine | IV morphine or IV paracetamol and ketoprofen |

| Nie 2015 | Postoperative analgesia | General anaesthesia with propofol, remifentanil and atracurium | Fascia iliaca block with landmarks (2‐3 cm below the inguinal ligament); catheter inserted at least 10 cm cranially and loaded with 20 to 30 mL (weight basis) of 0.5% ropivacaine followed by 0.25% bupivacaine at 0.1 mL/kg/h for 48 hours | IV patient‐controlled analgesia with fentanyl and tropisetron |

| Segado Jimenez 2009 | Postoperative analgesia | Spinal anaesthesia | Landmarks. Obturator nerve with 15 mL of bupivacaine with a vasoconstrictive agent, proximal to the obturator orifice. Femoral lateral cutaneous (Brown) with 10 mL of the same solution | IV morphine |

| Spansberg 1996 | Postoperative analgesia | Spinal anaesthesia | Femoral nerve block with nerve stimulator, non‐stimulating catheter advanced 8‐15 cm past needle tip. Inserted just before surgery. Loaded with 0.4 L/kg of bupivacaine 0.5%; continuous infusion with 0.14 mL/kg/h of bupivacaine 0.25% for 16 hours after surgery | IM morphine |

| Szucs 2012 | Preoperative and postoperative analgesia | Spinal anaesthesia | Non‐stimulating catheter for femoral nerve block, inserted in the emergency department with a nerve stimulator, 0.4 mA and 0.1 msec, space dilated before catheter insertion with 10 mL of 2% lidocaine, catheter advanced 3 cm past the needle tip and 10 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine through the catheter followed by 0.25% bupivacaine infused at 4 mL per hour for 72 hours | IM morphine |

| Tuncer 2003 | Postoperative analgesia | General anaesthesia for all participants with propofol, nitrous oxide, isoflurane, fentanyl, morphine and atracurium | Femoral (3‐in‐1) nerve block, nerve stimulator 0.1 mA, non‐stimulating catheter advanced 4‐5 cm past the needle tip. Loaded with 30 mL of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine followed by an infusion with bupivacaine 0.125% at 4 mL/h for 48 hours | IV morphine |

| White 1980 | Intraoperative analgesia | General anaesthesia with thiopental, nitrous oxide, halothane and fentanyl or nitrous oxide and alfaxolone/alfadolone | Psoas block with 30 mL of 2% mepivacaine, side to be blocked uppermost, Chayen's technique or Spinal: 0.6 to 0.8 mL of hyperbaric cinchocaine |

Conventional general anaesthesia |

| Yun 2009 | Preoperative analgesia | Spinal anaesthesia | Fascia iliaca block, Dalen's technique with 30 mL of 0.375% ropivacaine | IV alfentanil |

G: gram

h: hour

IM: intramuscular

mA: milliAmpere

mcg/mL: microgram/millilitre

mg/kg: milligram/kilogram

MHz: megahertz

mL: millilitre

msec: millisecond

n: number

SC: subcutaneous

Excluded studies

We excluded 26 studies (Characteristics of excluded studies) because they were not randomized controlled trials (n = 3; Fujihara 2013; Irwin 2012; Luger 2012), included no outcomes of interest for this review (n = 2; Bölükbasi 2013; Hwang 2015), studied a different population (n = 6; Durrani 2013; McRae 2015; Mutty 2007; Schiferer 2007; Segado Jimenez 2010; Sia 2004) or studied a different intervention (n = 15; Bech 2011; Foss 2007; Ghimire 2015; Gorodetskyi 2007; Hussain 2014; Kang 2013; Mannion 2005; Manohara 2015; Marhofer 1998; Matot 2003; Piangatelli 2004; Reavley 2015; Scheinin 2000; Turker 2003; Van Leeuwen 2000).

Studies awaiting classification

We have no studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

We found 19 ongoing trials (ACTRN12609000526279; EUCTR2006‐004001‐26‐GB; EUCTR2008‐004303‐59‐SE; EUCTR2010‐023871‐25‐GB; EUCTR2015‐000078‐36‐DK; ISRCTN07083722; ISRCTN46653818; ISRCTN75659782; ISRCTN92946117; NCT00749489; NCT01052974; NCT01219088; NCT01547468; NCT01593319; NCT01638845; NCT01904071; NCT02381717; NCT02406300; NCT02433548). (See Characteristics of ongoing studies.)

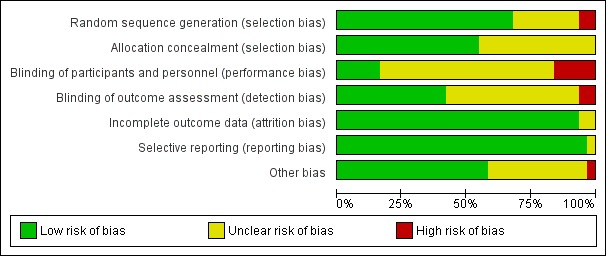

Risk of bias in included studies

We rated randomization as presenting high risk for two of the included studies because investigators provided no details on how randomization was performed and numbers of participants differed highly between groups (Antonopoulou 2006; De La Tabla 2010). We rated eight other studies as having unclear risk for randomization because the report provided no details (Altermatt 2013; Chudinov 1999; Coad 1991; Domac 2015; Mossafa 2005; Segado Jimenez 2009; Tuncer 2003; White 1980) (see Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We rated allocation concealment as introducing unclear or high risk of bias for less than 50% of the studies (see Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; Figure 3).

Blinding

We judged blinding of outcome assessors as appropriate for less than 50% of the studies (see Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; Figure 3).

Incomplete outcome data

We rated most studies as having low risk of attrition bias (see Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; Figure 3).

Selective reporting

We rated no studies as having high risk of bias for this item (see Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; Figure 3).

Other potential sources of bias

We rated only one study (Foss 2007) as having high risk of bias for other potential sources of bias because participants in the block group had higher pain scores on admission (P = 0.04) (see Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; Figure 3).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

1. Pain

1.1 Pain on movement and at rest within 30 minutes after block placement

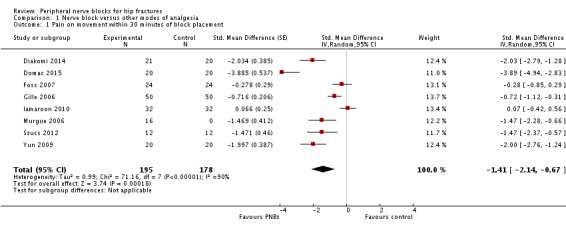

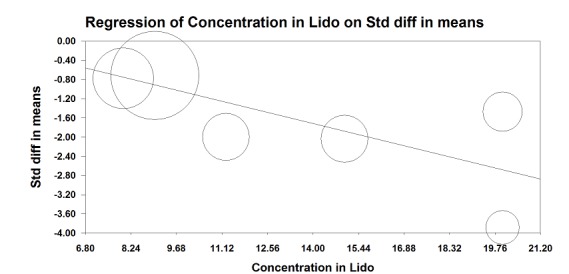

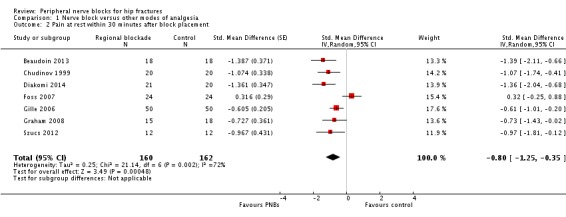

We did not retain data from two studies for this analysis. Jadon 2014 evaluated pain scores during positioning for spinal anaesthesia five minutes after a femoral nerve block performed with a nerve stimulator and 20 mL of a solution containing 15 mL of lidocaine 2% and 5 mL of distilled water. Parkinson 1989 reported that at five minutes after a femoral nerve block with lidocaine‐HCl and a nerve stimulator, only 6 and 11 participants out of 20 would have a complete or partial femoral nerve block, and 15 minutes would be required for a complete or partial femoral nerve block in all participants. Mossafa 2005 evaluated pain scores during positioning for spinal anaesthesia five minutes after a fascia iliaca block with 20 mL of lidocaine 1.5%. Although some effects on pain scores can be seen at 10 minutes after a fascia iliaca block with lidocaine, maximal effects are more likely to occur after 30 minutes or later (Dochez 2014; Gozlan 2005). We retained eight trials (Diakomi 2014; Domac 2015; Foss 2007; Gille 2006; Iamaroon 2010; Murgue 2006; Szucs 2012; Yun 2009) that included 373 participants evaluating pain on movement within 30 minutes after block placement: at 15 minutes (femoral nerve block with bupivacaine and nerve stimulator, pain during positioning for spinal anaesthesia; Iamaroon 2010), at 20 minutes (fascia iliaca with landmarks and ropivacaine, pain during positioning for spinal anaesthesia, Diakomi 2014; fascia iliaca block with landmarks and ropivacaine, pain during positioning for spinal anaesthesia, Yun 2009; femoral nerve block with a nerve stimulator and mepivacaine, pain during transfer on the radiological table for the X‐ray, Murgue 2006), at 30 minutes (fascia iliaca block with landmarks and mepivacaine, pain during passive elevation of the leg at 15 degrees, Foss 2007; non‐stimulating femoral nerve catheter with prilocaine inserted with a nerve stimulator, pain with passive anteflexion of the hip at 30 degrees, Gille 2006; non‐stimulating femoral nerve catheter with bupivacaine inserted with a nerve stimulator, pain with passive anteflexion of the hip at 30 degrees, Szucs 2012) or after 30 minutes (fascia iliaca with mixture of lidocaine and bupivacaine for pain during positioning for spinal > 30 minutes, Domac 2015). Pain scores were lower with regional blockade (standardized mean difference (SMD) ‐1.41, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐2.14 to ‐.067; I2 = 90%; Analysis 1.1). On the basis of the standard deviation in the control group of a study at low risk of bias (Diakomi 2014: 2.4), this was equivalent to ‐3.4 on a scale from 0 to 10. Egger's regression intercept showed the possibility of a small‐study effect as a source of heterogeneity (P = 0.02). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed no evidence of publication bias. Investigators in one study may have performed the evaluation before the effect of the local anaesthetic took place in most participants (15 minutes; Iamaroon 2010). When a femoral nerve block using a nerve stimulator is performed with bupivacaine, the median onset time for a complete sensory and motor block would be 30 minutes (5 to 95 percentiles; 15 to 45 minutes; Cuvillon 2009). Excluding this study (Iamaroon 2010) and one study that did not provide the exact concentration of local anaesthetic injected (Murgue 2006) led to an effect size that was correlated with the concentration of local anaesthetic used in lidocaine equivalent (P < 0.00001; Figure 4). We calculated equivalences as mentioned in the methods section (i.e. lidocaine = 1, bupivacaine = 4, chloroprocaine = 1.5, dibucaine = 4, etidocaine = 4, levobupivacaine = 3.9, mepivacaine = 0.8, prilocaine = 0.9, procaine = 0.5, ropivacaine = 3 and tetracaine = 4) (Berde 2009). Therefore, for Diakomi 2014, the concentration in lidocaine equivalent was calculated as 15 mg/mL (ropivacaine 0.5% or ropivacaine 5 mg/mL multiplied by 3 = 15 mg/mL). For Domac 2015, the concentration in lidocaine equivalent was calculated as 20 mg/mL (mixture of 15 mL bupivacaine 0.5% or bupivacaine 5 mg/mL multiplied by 4 = 20 mg/mL and 2% lidocaine or lidocaine 20 mg/mL). For Foss 2007, the equivalence was calculated as 8 mg/mL (mepivacaine 1% or mepivacaine 10 mg/mL multiplied 0.8 = 8 mg/mL). For Gille 2006, the lidocaine equivalent was calculated as 9 mg/mL (1% prilocaine or prilocaine 10 mg/mL multiplied by 0.9 = 9 mg/mL). For Szucs 2012, the equivalence was calculated as 20 mg/mL (10 mL of 2% lidocaine or lidocaine 20 mg/mL and 10 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine or bupivacaine 5 mg/mL multiplied by 4 = 20 mg/mL). For Yun 2009, the equivalence was calculated as 11.25 mg/mL (ropivacaine 0.375% or ropivacaine 3.75 mg/mL multiplied by 3 = 11.25 mg/mL). Results from Diakomi 2014 (mean and SD of the control group 7.5 and 2.4) show that 182 participants (91 per group) would be required in a simple trial to eliminate a difference of 1 on a 0 to 10 scale (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; two‐sided test) (http://stat.ubc.ca/˜rollin/stats/ssize/n2a.html).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nerve block versus other modes of analgesia, Outcome 1 Pain on movement within 30 minutes of block placement.

4.

Pain on movement in participants with hip fracture between 20 and 30 minutes after block placement. The effect size is proportionate to the concentration of local anaesthetic (mg/mL) used in lidocaine equivalent (P < 0.00001).

Local anaesthetic concentration in lidocaine equivalent (calculated as follows: lidocaine = 1, bupivacaine = 4, chloroprocaine = 1.5, dibucaine = 4, etidocaine = 4, levobupivacaine = 3.9, mepivacaine = 0.8, prilocaine = 0.9, procaine = 0.5, ropivacaine = 3 and tetracaine = 4).

Quality of evidence for pain on movement at 30 minutes after block placement

We downgraded the level of evidence by one because we rated five of the eight included studies as having unclear risk for blinding of outcome assessment. We did not downgrade the level of evidence on the basis of inconsistency because we found a reasonable explanation for heterogeneity. We used direct comparisons only with studies performed on the population of interest, and this is not a surrogate marker. The optimal information size was achieved, but we downgraded by one level for imprecision owing to a wide confidence interval around the effect size. We found no evidence of publication bias. We upgraded the level of evidence on the basis of a large effect size (SMD > 0.8). We also upgraded the level of evidence by one on the basis of confounding factors. No study used ultrasound guidance, an approach that could have increased block success (Lewis 2015). We upgraded the evidence by one on the basis of a dose‐response relationship (effect size was proportionate to the concentration of local anaesthetic used). We rated the quality of evidence as high.

Nine trials (Beaudoin 2013; Chudinov 1999; Diakomi 2014; Foss 2007; Gille 2006; Godoy 2010; Graham 2008; Iamaroon 2010; Szucs 2012) including 540 participants evaluated pain at rest within 30 minutes after block placement. Of these nine trials, two evaluated a fascia iliaca block with bupivacaine at 15 minutes (Godoy 2010) or a femoral nerve block with bupivacaine with a nerve stimulator, also at 15 minutes (Iamaroon 2010). Because these trials may have evaluated pain scores before the block could be effective (Cuvillon 2009), we excluded them from this analysis. We retained one trial with an evaluation performed at 15 minutes with bupivacaine (Beaudoin 2013) because femoral nerve blocks were performed with ultrasound, and onset of a femoral nerve block may have occurred earlier with ultrasound guidance (mean 16 minutes) compared with use of a nerve stimulator (mean 27 minutes) (Marhofer 1997). We therefore retained seven trials including 322 participants for this analysis. Investigators performed evaluations at 15 minutes (femoral nerve block with bupivacaine with ultrasound guidance, Beaudoin 2013), at 20 minutes (fascia iliaca block with ropivacaine, Diakomi 2014) or at 30 minutes (psoas compartment block with bupivacaine with loss of resistance technique, Chudinov 1999; fascia iliaca block with landmarks and mepivacaine, Foss 2007; non‐stimulating femoral nerve catheter with prilocaine inserted with a nerve stimulator, Gille 2006; femoral nerve block with bupivacaine with a paraesthesia technique or nerve stimulator, Graham 2008; non‐stimulating femoral nerve catheter with bupivacaine inserted with a nerve stimulator, Szucs 2012). Regional blockade decreased pain scores at rest within 30 minutes after block placement (SMD ‐0.80, 95% CI ‐1.25 to ‐0.35; I2 = 72%; Analysis 1.2). When a study at low risk of bias is used (Diakomi 2014), this reduction would be equivalent to 1.7 on a scale from 0 to 10. Egger's regression intercept showed no statistically significant small‐study effect (two‐sided test). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that two trials might be missing to right of mean for an adjusted point of estimate of ‐0.58 (95% CI ‐1.01 to ‐0.14). Taken individually, only one trial (Foss 2007) did not favour regional blockade and for this study, pain scores before block placement were significantly higher in the regional blockade group. Excluding this trial shows that the effect favouring regional blockade would be SMD ‐0.95 (95% CI ‐1.23 to ‐0.66; I2 = 17%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nerve block versus other modes of analgesia, Outcome 2 Pain at rest within 30 minutes after block placement.

1.2 Pain on movement and at rest at six to eight hours after surgery

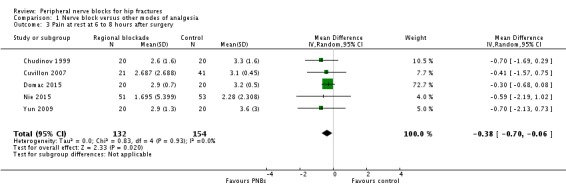

One trial (Domac 2015) gave results for pain on movement at six to eight hours after surgery (SMD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.62 to 0.62). Results from five trials with 286 participants (Chudinov 1999; Cuvillon 2007; Domac 2015; Nie 2015; Yun 2009) show that peripheral nerve blocks decreased pain scores on a scale from 0 to 10 for pain at rest at 6 to 8 hours after surgery (mean difference (MD) ‐0.38, 95% CI ‐0.70 to 0.06; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.3). Egger's regression intercept showed no statistically significant small‐study effect (P = 0.05; two‐sided test). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis calculated that three trials might be missing to right of mean for an adjusted point of estimate of MD ‐0.32 (95% CI ‐0.60 to ‐0.03).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nerve block versus other modes of analgesia, Outcome 3 Pain at rest at 6 to 8 hours after surgery.

1.3 Pain on movement and at rest at 24 hours after surgery

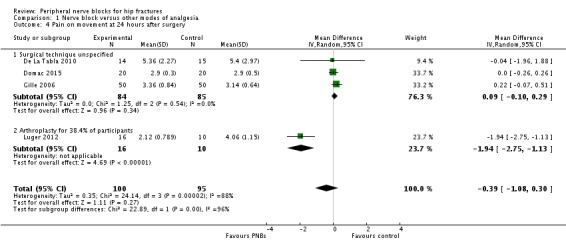

Based on four trials with 195 participants (continuous ultrasound‐guided femoral nerve block, De La Tabla 2010; single shot landmark fascia iliaca block, Domac 2015; continuous nerve stimulator‐guided femoral nerve block, Gille 2006; continuous ultrasound‐guided femoral nerve block, Luger 2012) we did not find a difference in pain scores on movement at 24 hours (MD ‐0.39, 95% CI ‐1.08 to 0.30; I2 = 95.6%; Analysis 1.4). Egger's regression intercept showed no statistically significant small‐study effect (two‐sided test). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that one study might be missing to left of mean for an adjusted point of estimate of SMD ‐0.58 (95% CI ‐1.45 to 0.30; random‐effects model).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nerve block versus other modes of analgesia, Outcome 4 Pain on movement at 24 hours after surgery.

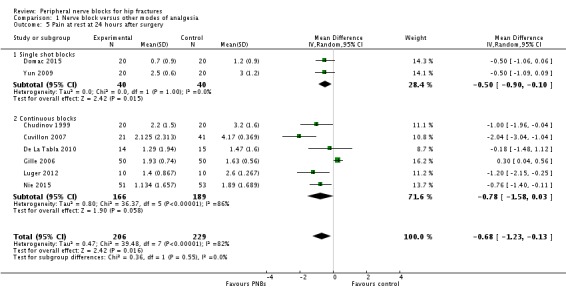

Findings of eight trials (single shot blocks, Domac 2015; Yun 2009; continuous blocks, Chudinov 1999; Cuvillon 2007; De La Tabla 2010; Gille 2006; Luger 2012; Nie 2015) including 435 participants show decreased pain scores at rest at 24 hours (MD ‐0.68, 95% CI ‐1.23 to ‐0.13; I2 = 82%; Analysis 1.5). Egger's regression intercept showed the possibility of a small‐study effect (P = 0.02; two‐sided test). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed no evidence of publication bias. The effect seems as good with a single shot block as with a continuous block: heterogeneity between subgroups was 0% (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nerve block versus other modes of analgesia, Outcome 5 Pain at rest at 24 hours after surgery.

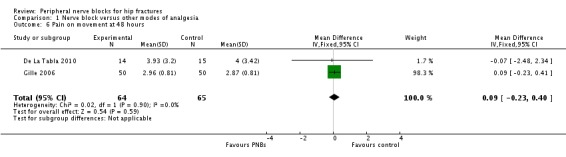

Pain on movement and at rest at 48 hours after surgery

Three trials (De La Tabla 2010; Domac 2015; Gille 2006) gave data for pain on movement at 48 hours, two of which used continuous femoral nerve blocks (De La Tabla 2010; Gille 2006). Results of these two trials (De La Tabla 2010; Gille 2006) including 129 participants show that continuous peripheral nerve blocks do not affect pain on movement at 48 hours after surgery (MD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.23 to 0.40; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nerve block versus other modes of analgesia, Outcome 6 Pain on movement at 48 hours.

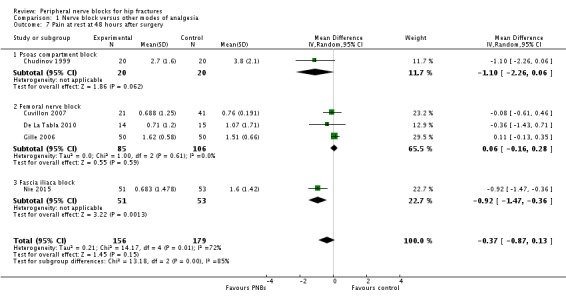

Six trials (Chudinov 1999; Cuvillon 2007; De La Tabla 2010; Domac 2015; Gille 2006; Nie 2015) gave results for pain at rest at 48 hours after surgery. Five of these studies used continuous nerve blocks (Chudinov 1999; Cuvillon 2007; De La Tabla 2010; Gille 2006; Nie 2015) and included 335 participants. Peripheral nerve blocks did not affect pain scores at rest at 48 hours (MD ‐0.37, 95% CI ‐0.87 to 0.13; I2 = 72%; Analysis 1.7). The effect may differ with the type of block used: I2 statistic for the difference between subgroups is 85% (P = 0.001). Egger's regression intercept showed no statistically significant small‐study effect (two‐sided test). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis calculated that one study might be missing to right of mean for an adjusted point estimate of MD ‐0.25 (95% CI ‐0.68 to 0.18; random‐effects model).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nerve block versus other modes of analgesia, Outcome 7 Pain at rest at 48 hours after surgery.

1.5 Pain on movement and at rest at 72 hours after surgery

One trial (Gille 2006) with 100 participants using a continuous femoral nerve block gave results for pain on movement at 72 hours after surgery (MD 0.25, 95% CI ‐0.02 to ‐0.52).

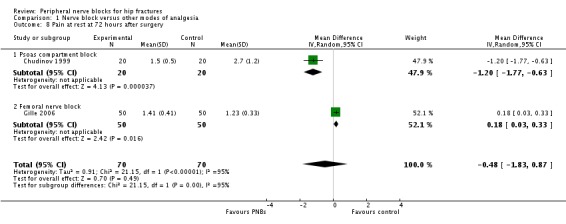

Two trials including 140 participants (psoas compartment block, Chudinov 1999; continuous femoral nerve block, Gille 2006) provided results for pain at rest at 72 hours after surgery for a continuous peripheral nerve block (MD ‐0.48, 95% CI ‐1.83 to 0.87). Data show an effect for a psoas compartment block (MD ‐1.20, 95% CI ‐1.77 to ‐0.63) but not for a femoral nerve block (MD 0.18, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.33). Heterogeneity between subgroups was statistically significant (I2 = 95%; P < 0.00001).

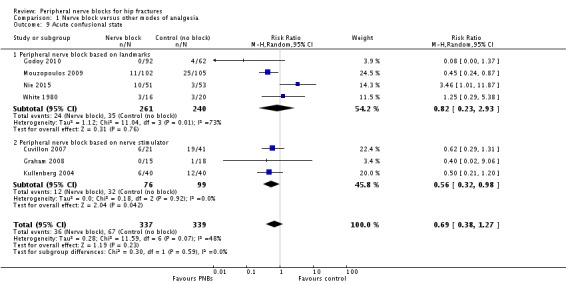

2. Acute confusional state

We have provided definitions used by study authors in Table 3. Based on seven trials (Cuvillon 2007; Godoy 2010; Graham 2008; Kullenberg 2004; Mouzopoulos 2009; Nie 2015; White 1980 with 676 participants, we did not find a difference in the incidence of acute confusional state (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.27; I2 = 48%). Egger's regression intercept showed no statistically significant small‐study effect (two‐sided test). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis calculated that one trial might be missing to right of mean for an adjusted point of estimate of RR 0.77 (95% CI 0.40 to 1.45; Analysis 1.9). Given a rate of 19%, the number of participants required to eliminate a 25% decrease would be 1518 (759 per group) (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; one‐sided test).

2. Outcome definitions for acute confusional state.

| Study | Study authors' definition |

| Cuvillon 2007 | Clinical evaluation "somnolence‐confusion" |

| Godoy 2010 | "episodes of delirium" |

| Graham 2008 | "acute confusional state" |

| Kullenberg 2004 | "transient confusion" |

| Mouzopoulos 2009 | "The primary outcome was perioperative delirium.

Diagnosis of the syndrome was defined using the Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th

edition (DSM‐IV), and Confusion Assessment Method

(CAM) criteria" "Daily patient assessments using the MMSE, DRS‐R‐ 98, and Digit Span test [assessment of attention, range 0 (no attention) to 42 (good attention)] were used to enable the DSM‐IV and CAM diagnoses and assess delirium severity" |

| Nie 2015 | "Presurgery cognitive status was estimated using the mini‐mental state examination before and after surgery. The Confusion Assessment Method was used to diagnose delirium pre‐ and postsurgery" |

| White 1980 | "confused" |

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nerve block versus other modes of analgesia, Outcome 9 Acute confusional state.

Quality of evidence for acute confusional state

We downgraded the level of evidence by two for risk of bias because we rated 75% or more of the studies as having unclear or high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessors. We downgraded the level by one for a moderate amount of heterogeneity. We included only direct comparisons performed on the population of interest, and this is not a surrogate marker. We downgraded the level by one for imprecision because the optimal information size was not achieved. We did not downgrade the level of evidence on the basis of the possibility of publication bias because applying a correction for the possibility of one would not modify the conclusion. We found no evidence of a large effect. We downgraded the level of evidence by one for confounding factors because no study used ultrasound guidance, an approach that could have increased block success (Lewis 2015). We rated the quality of evidence as very low.

3. Myocardial infarction/ischaemia

Two trials (Altermatt 2013; Luger 2012) gave results for myocardial ischaemia. Altermatt 2013, with 31 included participants, evaluated effects of a continuous psoas compartment block started preoperatively and maintained until postoperative day 3, and reported the number of ischaemic events (EKG segment analysis) recorded by participants during the observation period as 6 per participant with regional blockade (n = 17) versus 3 per participant with intravenous patient‐controlled analgesia (n = 14) (P = 0.618). Luger 2012 reported that 1 of 10 participants with an ultrasound‐guided continuous femoral nerve block had myocardial ischaemia (serum T troponin levels increased), as did 5 of 10 participants without a peripheral nerve block (RR 0.68, 95% CI ‐2.54 to 0.12). Given an incidence of 30%, 850 participants (425 per group) would be required in a simple trial, to eliminate a 25% reduction in the number of participants experiencing cardiac enzyme elevation (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; one‐sided test).

Quality of evidence for myocardial ischaemia

We downgraded the level of evidence by two for risk of bias because we judged the included study (Luger 2012) as having unclear risk for allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors. We could not assess heterogeneity. The trial performed a direct comparison. We downgraded evidence by two for imprecision owing to inclusion of very few participants/trials in the analysis. We found no evidence of a large effect or confounding factors that would justify upgrading. We found no evidence of a dose‐response effect. We rated the quality of evidence as very low.

Secondary outcomes

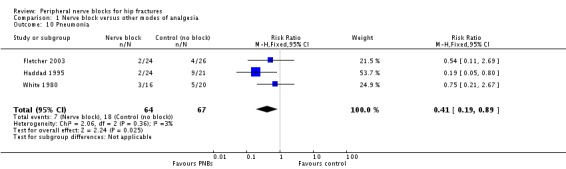

1. Pneumonia

Results of three trials (Fletcher 2003; Haddad 1995; White 1980) with 131 participants show that peripheral nerve blocks reduced the risk of pneumonia (RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.89; I2 = 3%; Analysis 1.10). Egger's regression intercept showed no significant evidence of a small‐study effect. Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis revealed no evidence of publication bias. Two trials evaluated a femoral (or three‐in‐one) nerve block (Fletcher 2003; Haddad 1995), and one trial evaluated a psoas compartment block (White 1980). Definitions and time points used included lower respiratory tract infection within six months from hospital notes (Fletcher 2003), short‐term respiratory infection (Haddad 1995) and pneumonia during hospitalization (mean duration 20 days, SD 11.5 days; White 1980). Although all three trials showed a trend towards a reduced incidence of lower respiratory tract infection when a peripheral nerve block was added to the postoperative analgesia regimen, Haddad 1995 reported the largest reduction. The complication rate observed in Haddad 1995 was extremely high compared with the actual rate (Cordero 2016). Given a basal rate of 27%, the NNTB would be 7 (95% CI 5 to 72) and the number of participants required to eliminate a 25% decrease would be 978 (489 per group) (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; one‐sided test).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nerve block versus other modes of analgesia, Outcome 10 Pneumonia.

Quality of evidence for pneumonia

We downgraded the evidence by one level for risk of bias. Statistical heterogeneity was less than 25% (I2 = 3%). We downgraded evidence by one level for clinical heterogeneity owing to the excessive rate of complications observed in Haddad 1995. We used direct comparisons only with studies performed on the population of interest, and this is not a surrogate marker. The optimal information size was not achieved. We found no evidence of publication bias. We upgraded the level of evidence by one owing to a large effect size (RR 0.41). We upgraded on the basis of confounding factors for technology because no study used ultrasound guidance or a nerve stimulator. We did not upgrade for a dose‐response effect. We rated the quality of evidence as moderate.

2. Mortality

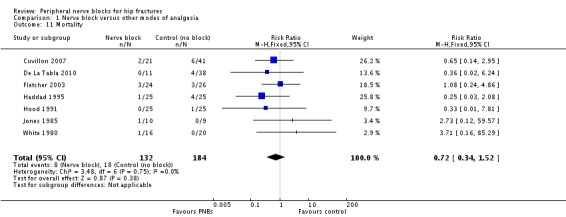

Based on seven trials (Cuvillon 2007; De La Tabla 2010; Fletcher 2003; Haddad 1995; Hood 1991; Jones 1985; White 1980) including 316 participants, we did not find a difference in short‐term (within six months) mortality (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.52; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.11). Egger's regression intercept showed no significant evidence of a small‐study effect. Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed no evidence of publication bias. Given an incidence of 9.8%, 3228 participants (1614 per group) would have been required to eliminate a 25% reduction (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; one‐sided test).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nerve block versus other modes of analgesia, Outcome 11 Mortality.

Quality of evidence for mortality within six months

We did not downgrade for risk of bias and we noted no heterogeneity. We used direct comparisons only with studies performed on the population of interest, and this is not a surrogate marker. We downgraded the level of evidence by two for imprecision because the confidence interval included both absence of effect and important benefit. We found no evidence of publication bias nor of large effect or dose‐response effect, and no confounding factors justified upgrading an absence of effect. We rated the quality of evidence as low.

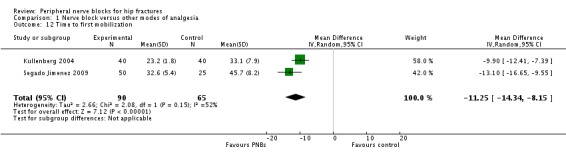

3. Time to first mobilization

Findings of two trials (Kullenberg 2004; Segado Jimenez 2009) with 155 participants show that peripheral nerve blocks reduced time to first mobilization (MD ‐11.25 hours, 95% CI ‐14.34 to ‐8.15 hours; I2 = 52%; Analysis 1.12). On the basis of the findings of Kullenberg 2004 (mean and SD 33.1 and 7.9 hours, respectively), 30 participants (15 per group) would be required to eliminate a 25% difference (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; two‐sided test) in a simple trial.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nerve block versus other modes of analgesia, Outcome 12 Time to first mobilization.

Quality of evidence for time to first mobilization

We downgraded the level of evidence by one for risk of bias because we rated one study as having unclear risk for allocation concealment and the other as having unclear risk for blinding of outcome assessors. We downgraded quality of evidence by one level for a moderate amount of heterogeneity. We used direct comparisons only with studies performed on the population of interest, and this is not a surrogate marker. The optimal information size was achieved, but we downgraded evidence by one level for imprecision owing to a wide confidence interval around the effect size. We could not assess publication bias. We upgraded the level of evidence on the basis of a large effect size (equivalent to a SMD of ‐1.87). We also upgraded the level of evidence by one on the basis of confounding factors. No study used ultrasound guidance, an approach that could have increased block success (Lewis 2015). We found no evidence of a dose‐response effect. We rated the quality of evidence as moderate.

4. Costs of analgesic regimens

Results of two trials (Cuvillon 2007; Segado Jimenez 2009) with 137 participants show that costs related to analgesia were reduced when regional blockade was used as a single shot block (SMD ‐3.48, 95% CI ‐4.23 to ‐2.74) but were higher when regional blockade was used as a continuous infusion (SMD 0.93, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.48; I2 for heterogeneity between subgroups = 99%).

Quality of evidence for cost of analgesic regimens

We rated the quality of evidence for single shot blocks only. We downgraded the level of evidence by one for risk of bias because we rated the included study as having unclear risk for allocation concealment. The comparison was a direct one. We downgraded the evidence by one level for the small number of trials included. We could not assess publication bias. We upgraded the level of evidence on the basis of a large effect size (SMD > 0.8). We found no confounding factors that would justify upgrading or dose‐response effect. We rated the quality of the evidence as moderate.

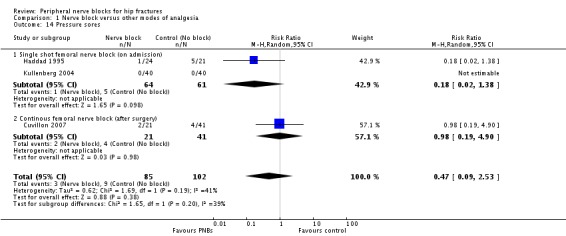

5. Pressure sores

Based on three trials (Cuvillon 2007; Haddad 1995; Kullenberg 2004) including 187 participants, we did not find a difference in the incidence of pressure sores (RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.09 to 2.53; I2 = 39.5%; Analysis 1.14). Given an incidence of 6%, 5466 participants (2733 per group) would have been required to eliminate a 25% difference (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; one‐sided test) in a large trial.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nerve block versus other modes of analgesia, Outcome 14 Pressure sores.

6. Number of participants transfused

One trial (Cuvillon 2007) including 62 participants gave results for the number of participants transfused (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.28 to 2.20). Given an incidence of 22%, 1270 participants (635 per group) would have been required to eliminate a 25% difference (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; one‐sided test) in a large trial.

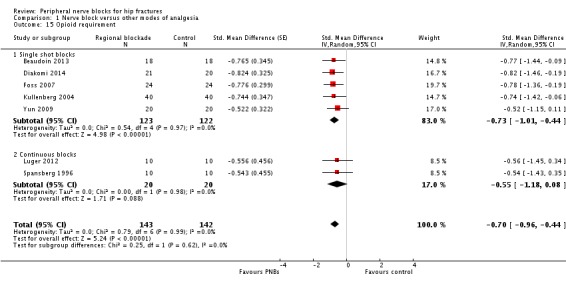

7. Opioid consumption

Results from seven trials (Beaudoin 2013; Diakomi 2014; Foss 2007; Kullenberg 2004; Luger 2012; Spansberg 1996; Yun 2009) show that peripheral nerve blocks reduced opioid consumption up to 24 hours after surgery (SMD ‐0.70, 95% CI ‐0.96 to ‐0.44; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.15). Egger's regression intercept showed no significant evidence of a small‐study effect. Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis calculated that one trial might be missing to left of mean, for an adjusted point of estimate of ‐0.73 (95% CI ‐0.97 to ‐0.49; random‐effects model). We found a reduction in opioid consumption for both single shot and continuous blocks and noted no heterogeneity between subgroups: I2 = 0%.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Nerve block versus other modes of analgesia, Outcome 15 Opioid requirement.

8. Wound infection

One trial (Haddad 1995) including 45 participants gave results for wound infection (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.24 to 7.12). Given an incidence of 11%, 2736 participants (1368 per group) would have been required to eliminate a 25% difference (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; one‐sided test) in a large trial.

9. Participant satisfaction

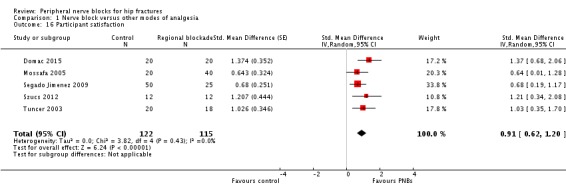

Results of five trials (Domac 2015; Mossafa 2005; Segado Jimenez 2009; Szucs 2012; Tuncer 2003) with 237 participants show that participants were more satisfied with their mode of pain treatment when regional blockade was used (SMD 0.91, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.20; I2 = 0%). Egger's regression intercept showed no significant evidence of a small‐study effect. Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis calculated that two trials might be missing to left of mean, for an adjusted point of estimate of 0.75 (95% CI 0.50 to 1.00; random‐effects model). On the basis of findings from Szucs 2012 (mean and SD of the control group 7.6 and 1.8), the difference would be equivalent to 1 on a scale from 1 to 10.

10. Complications

None of the 31 trials included in this review reported major complications related to regional blockade. A list of complications reported with both modes of pain treatment can be found in Table 4.

3. Complications of blocks and/or analgesic technique.

| Study | Complications related to regional anaesthesia | Complications related to analgesic technique |

| Altermatt 2013 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Antonopoulou 2006 | No complications such as motor block. local

haematoma or infection, inadvertent arterial puncture, direct nerve

damage and cardiovascular or neurological toxicity were observed Five participants had accidental removal or the catheter: 4 during the procedure or while the catheter was secured and 1 while in the ward |

Not reported |

| Beaudoin 2013 | No other adverse events were noted during the study period, and no other adverse events were reported to study investigators | Four‐hour oxygen saturation (%) 96 (93–99) vs (%) 98 (95–99) for regional blockade Adverse events: Hypotension, number (%) 3 (17) vs number (%) 0 (0) for regional blockade Respiratory depression, number (%) 9 (50) vs number (%) 4 (22) for regional blockade Nausea/vomiting, number (%) 5 (28) vs number (%) 5 (28) for regional blockade One participant had an episode of rapid atrial fibrillation requiring diltiazem, but the participant had a history of chronic atrial fibrillation |

| Chudinov 1999 | No major complications were described in group regional blockade. Three participants developed local erythema at the catheter insertion site at the end of the study period No signs of local anaesthetic toxicity were documented One participant developed bilateral blockade (L1‐L3 on the opposite side) |

Not reported |

| Coad 1991 | No complications related to nerve blocks and no case of prolonged motor blockade | Not reported |

| Cuvillon 2007 | Four catheters were prematurely removed: 1 by a confused participant, 2 by nurses (unexplained fever) and 1 by a surgeon (unconfirmed suspicion of local anaesthetic toxicity (ropivacaine blood level < 2 ng/mL)) | More constipation (47% vs 19% for regional blockade) |

| De La Tabla 2010 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Diakomi 2014 | Complications such as local anaesthetic toxicity recorded as well (none reported in results section) Nor did complication rates vary between groups |

Complications such as hypoventilation (breathing rate < 8 breaths/min) were recorded as well Moreover, the 2 groups did not differ in these parameters at any time point until study completion at 24 hours after surgery. Nor did complication rates vary between groups |

| Domac 2015 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Fletcher 2003 | Among study participants, none experienced adverse effects as a result of nerve block administration | No clinically important differences between groups with respect to pulse rate, oxygen saturation or respiratory rate at any time interval. Oxygen saturation 94.87% |

| Foss 2007 | No side effects attributable to femoral nerve block were noted in any participants during their hospital stay | More participants (P = 0.05) were sedated in the morphine group at 180 minutes after block placement No difference was noted between groups in nausea and vomiting, with 3 participants in each group having these side effects Tendency toward lower saturation was noted in the opioid group at 60 and 180 minutes after the block despite oxygen supplementation (P = 0.08) |

| Gille 2006 | One inadvertent arterial puncture and blood aspiration positive for 3 participants Two transient paraesthesias No catheter site infection Ten catheters accidentally removed |

No respiratory depression from systemic analgesia and no allergic reactions All complications were reversible |

| Godoy 2010 | The only complications were local bruises at the site of injection | Two participants with nausea, and 2 with nausea and vomiting |

| Graham 2008 | No immediate complications occurred in either group | No immediate complications were noted in either group |

| Haddad 1995 | No local or systemic complications of femoral nerve blocks were noted | Not reported |

| Hood 1991 | No untoward sequelae were associated with nerve blocks All plasma prilocaine concentrations (maximum 3 pg/mL) were below the suggested threshold for toxicity for prilocaine of 6 pg/mL |

Not reported |

| Iamaroon 2010 | No adverse systemic toxicity of bupivacaine, such as seizure, arrhythmia or cardiovascular collapse was noted in the femoral nerve block group Neither vascular puncture nor paraesthesia occurred No complications, such as haematoma, infection or persistent paraesthesia, were observed within 24 hours after the operation |

No participant in either group had hypoventilation (ventilatory rate < 10/min) or oxygen saturation < 95% |

| Jadon 2014 | Not reported | In participants of fentanyl group, drowsiness was observed that required the presence of more persons for holding the participant during positioning SpO2 was significantly lower in the fentanyl group (P = 0.001). However, no participant in either group had SpO2 < 90% during the procedure Mean arterial blood pressure was significantly lower in the fentanyl group (P = 0.0019) |

| Jones 1985 | No untoward sequelae associated with the nerve block were seen | Not reported |

| Kullenberg 2004 | No complications related to the nerve blockade were noted in this study | Not reported |

| Luger 2012 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Mossafa 2005 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Mouzopoulos 2009 | No complications of femoral nerve block administrations occurred, except 3 local haematomas developed at the injection site, which resolved spontaneously | Not reported |

| Murgue 2006 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Nie 2015 | No adverse effects, such as pain at the insertion site or paraesthesia, were observed No positive cultures were observed with the fascia iliaca block catheter tip, nor were any signs of infection noted in the current study |

Not reported |

| Segado Jimenez 2009 | We did not observe any complications in the realization of regional anaesthetic techniques during or subsequent to the regional anaesthetic techniques | The incidence of side effects (sleepiness, hypotension, constipation, pruritus) was greater in the group with no block than in groups with blocks (P < 0.01) |