Abstract

Background

Among subfertile women undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART), hormone pills given before ovarian stimulation may improve outcomes.

Objectives

To determine whether pretreatment with the combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) or with a progestogen or oestrogen alone in ovarian stimulation protocols affects outcomes in subfertile couples undergoing ART.

Search methods

We searched the following databases from inception to January 2017: Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group Specialised Register, The Cochrane Central Register Studies Online, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL and PsycINFO. We also searched the reference lists of relevant articles and registers of ongoing trials.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of hormonal pretreatment in women undergoing ART.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures recommended by Cochrane. The primary review outcomes were live birth or ongoing pregnancy and pregnancy loss.

Main results

We included 29 RCTs (4701 women) of pretreatment with COCPs, progestogens or oestrogens versus no pretreatment or alternative pretreatments, in gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist or antagonist cycles. Overall, evidence quality ranged from very low to moderate. The main limitations were risk of bias and imprecision. Most studies did not describe their methods in adequate detail.

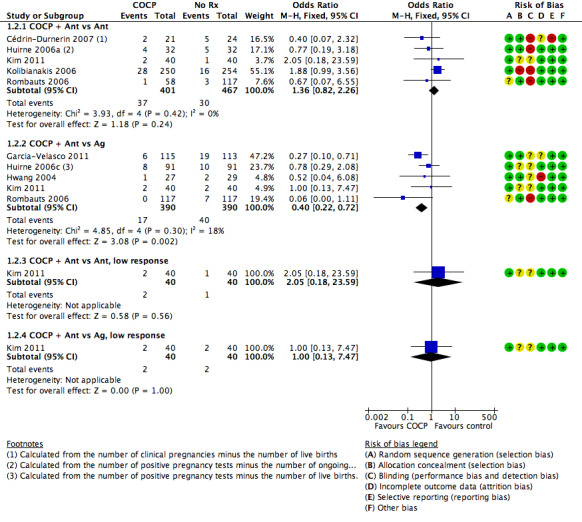

Combined oral contraceptive pill versus no pretreatment

With antagonist cycles in both groups the rate of live birth or ongoing pregnancy was lower in the pretreatment group (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.95; 6 RCTs; 1335 women; I2 = 0%; moderate quality evidence). There was insufficient evidence to determine whether the groups differed in rates of pregnancy loss (OR 1.36, 95% CI 0.82 to 2.26; 5 RCTs; 868 women; I2 = 0%; moderate quality evidence), multiple pregnancy (OR 2.21, 95% CI 0.53 to 9.26; 2 RCTs; 125 women; I2 = 0%; low quality evidence), ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS; OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.28 to 3.40; 2 RCTs; 642 women; I2 = 0%, low quality evidence), or ovarian cyst formation (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.08 to 2.75; 1 RCT; 64 women; very low quality evidence).

In COCP plus antagonist cycles versus no pretreatment in agonist cycles, there was insufficient evidence to determine whether the groups differed in rates of live birth or ongoing pregnancy (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.25; 4 RCTs; 724 women; I2 = 0%; moderate quality evidence), multiple pregnancy (OR 1.36, 95% CI 0.85 to 2.19; 4 RCTs; 546 women; I2 = 0%; moderate quality evidence), or OHSS (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.96; 2 RCTs; 290 women, I2 = 0%), but there were fewer pregnancy losses in the pretreatment group (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.72; 5 RCTs; 780 women; I2 = 0%; moderate quality evidence). There were no data suitable for analysis on ovarian cyst formation.

One small study comparing COCP versus no pretreatment in agonist cycles showed no clear difference between the groups for any of the reported outcomes.

Progestogen versus no pretreatment

All studies used the same protocol (antagonist, agonist or gonadotrophins) in both groups. There was insufficient evidence to determine any differences in rates of live birth or ongoing pregnancy (agonist: OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.69 to 2.65; 2 RCTs; 222 women; I2 = 24%; low quality evidence; antagonist: OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.18 to 2.54; 1 RCT; 47 women; low quality evidence; gonadotrophins: OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.09 to 4.23; 1 RCT; 42 women; very low quality evidence), pregnancy loss (agonist: OR 2.26, 95% CI 0.67 to 7.55; 2 RCTs; 222 women; I2 = 0%; low quality evidence; antagonist: OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.06 to 2.09; 1 RCT; 47 women; low quality evidence; gonadotrophins: OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.06 to 17.12; 1 RCT; 42 women; very low quality evidence) or multiple pregnancy (agonist: no data available; antagonist: OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.06 to 17.76; 1 RCT; 47 women; low quality evidence; gonadotrophins: no data available). Three studies, all using agonist cycles, reported ovarian cyst formation: rates were lower in the pretreatment group (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.32; 374 women; I2 = 1%; moderate quality evidence). There were no data on OHSS.

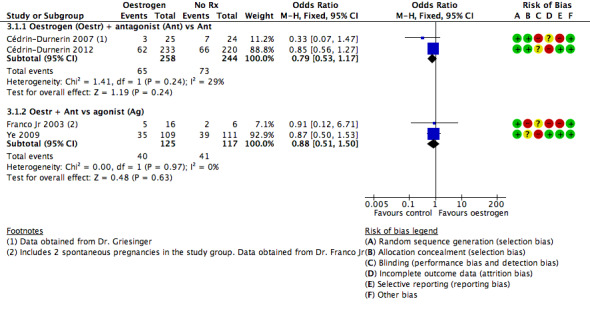

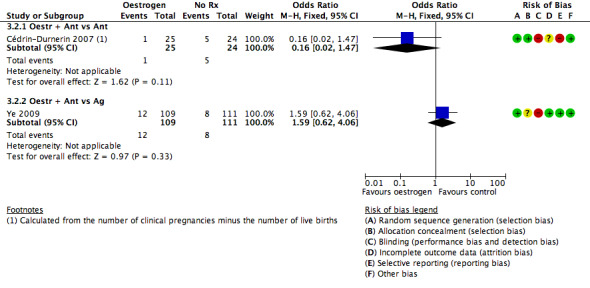

Oestrogen versus no pretreatment

In antagonist or agonist cycles, there was insufficient evidence to determine whether the groups differed in rates of live birth or ongoing pregnancy (antagonist versus antagonist: OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.17; 2 RCTs; 502 women; I2 = 0%; low quality evidence; antagonist versus agonist: OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.50; 2 RCTs; 242 women; I2 = 0%; very low quality evidence), pregnancy loss (antagonist versus antagonist: OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.47; 1 RCT; 49 women; very low quality evidence; antagonist versus agonist: OR 1.59, 95% CI 0.62 to 4.06; 1 RCT; 220 women; very low quality evidence), multiple pregnancy (antagonist versus antagonist: no data available; antagonist versus agonist: OR 2.24, 95% CI 0.09 to 53.59; 1 RCT; 22 women; very low quality evidence) or OHSS (antagonist versus antagonist: no data available; antagonist versus agonist: OR 1.54, 95% CI 0.25 to 9.42; 1 RCT; 220 women). Ovarian cyst formation was not reported.

Head‐to‐head comparisons

COCP was compared with progestogen (1 RCT, 44 women), and with oestrogen (2 RCTs, 146 women), and progestogen was compared with oestrogen (1 RCT, 48 women), with an antagonist cycle in both groups. COCP in an agonist cycle was compared with oestrogen in an antagonist cycle (1 RCT, 25 women). Data were scant but there was no clear evidence that any of the groups differed in rates of live birth or ongoing pregnancy, pregnancy loss or other adverse events.

Authors' conclusions

Among women undergoing ovarian stimulation in antagonist protocols, COCP pretreatment was associated with a lower rate of live birth or ongoing pregnancy than no pretreatment. There was insufficient evidence to determine whether rates of live birth or ongoing pregnancy were influenced by pretreatment with progestogens or oestrogens, or by COCP pretreatment using other stimulation protocols. Findings on adverse events were inconclusive, except that progesterone pretreatment may reduce the risk of ovarian cysts in agonist cycles, and COCP in antagonist cycles may reduce the risk of pregnancy loss compared with no pretreatment in agonist cycles.

Plain language summary

Pretreatments in in vitro fertilisation/intra‐cytoplasmic sperm injection cycles

Review question

The aim of this review was to assess whether pretreatment with a combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) or with progestogen or oestrogen alone influences pregnancy outcomes in couples with low fertility undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART)

Background

In vitro fertilisation (IVF; where an egg is mixed with sperm outside the body) and intra‐cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI; where one sperm is injected directly into the egg) are important techniques for women who have trouble getting pregnant. IVF and ICSI cycles consist of a few steps. First the woman receives hormone therapy to stimulate her ovaries in producing egg cells (called ovarian stimulation). When a few egg cells are mature enough to be fertilised, the woman receives a single hormone injection. This triggers the ovaries to release the egg cells, so they can be gathered by the clinician. The eggs are then fertilised outside the woman's body and become embryos. One or two embryos are then transferred into the womb.

Before the first step in IVF or ICSI cycles (hormone therapy), a pretreatment with a COCP can be given. A COCP contains both progestogen and oestrogen. Pretreatment with a progestogen or oestrogen alone could also be used before the hormone therapy. These pretreatments suppress the woman's own hormone production. This might improve the woman's response to the hormone therapy in IVF/ICSI cycles. In this way, side events such as cyst formation (fluid‐filled sac that develops on a woman's ovary) and the number of pregnancy losses might be reduced and pregnancy outcomes might be improved.

Study characteristics

This Cochrane Review included 30 randomized controlled trials (clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) assessing pretreatment with COCP, progestogen or oestrogen in 5096 women undergoing ART. The evidence is current to January 2017.

Key results

Among women undergoing ovarian stimulation in antagonist protocols, COCP pretreatment was associated with a lower rate of live birth or ongoing pregnancy than no pretreatment. There was insufficient evidence to determine whether rates of live birth or ongoing pregnancy were influenced by pretreatment with progestogens or oestrogens, or by COCP pretreatment using other stimulation protocols. Findings on adverse events were inconclusive, except that progesterone pretreatment may reduce the risk of ovarian cysts in agonist cycles, and COCP in antagonist cycles may reduce the risk of pregnancy loss compared with no pretreatment in agonist cycles.

Quality of the evidence.

Overall evidence quality ranged from very low to moderate. The main problems were risk of bias and imprecision. Most studies did not describe their methods in adequate detail.

Summary of findings

Background

For definitions of terminology see our Glossary (Appendix 1).

Description of the condition

For subfertile women, assisted reproductive techniques (ART) such as in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and intra‐cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) can be a way to achieve pregnancy. Pregnancy and live birth rates are higher with IVF than with expectant management (Pandian 2005).

An IVF cycle has the following stages: ovarian stimulation, oocyte retrieval, fertilisation of the egg and transfer of the embryo. Ovarian stimulation involves the administration of gonadotrophins. These hormones stimulate growth and maturation of the follicle. Gonadotrophins include follicle‐stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH). There are two different gonadotrophin preparations; human menopausal gonadotrophin (hMG) which consists of both FSH and LH, and a more recent therapy, recombinant follicle‐stimulating hormone (rFSH). There is insufficient evidence of a difference between these treatments in ongoing pregnancy or live birth rate and other aspects with relation to IVF (Van Wely 2003).

There are a number of undesirable events associated with gonadotrophin therapy that can complicate treatment and outcomes: ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), premature LH‐surge and multiple pregnancy (Dodson 1989). In some women undergoing IVF therapy, these problems occur because the endogenous FSH and LH production is too dominant (Awadalla 1987). Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone analogues (GnRHa) are administered to inhibit the production of endogenous FSH and LH (Awadalla 1987; Dodson 1989). Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) is a hormone that occurs naturally in the woman's body and that regulates the production of gonadotrophins. There are two different types of GnRHa: agonists or antagonists. The difference lies in their mechanism of action. GnRH agonists bind to the GnRH receptors in the pituitary gland and initially stimulate the release of gonadotrophins ('flare‐up'). Negative feedback causes a decrease in the number of GnRH receptors, which results in the release of fewer gonadotrophins. In a traditional treatment protocol, GnRH agonists are administered prior to commencing gonadotrophins, ensuring that the flare‐up will be over by the time gonadotrophins are injected. Conversely, GnRH antagonists can be started after gonadotrophin therapy has been administered because they bind competitively to the receptor, causing immediate suppression of the endogenous production of FSH and LH (Tarlatzis 2006). Therefore, GnRHa can prevent a premature LH‐surge and synchronise the follicle cohort.

The authors of one Cochrane Review comparing GnRH agonist cycles with GnRH antagonist cycles concluded that GnRH antagonists are associated with a substantial reduction in OHSS without reducing the likelihood of achieving live birth (Al‐Inany 2016).

When a few follicles reach maturity after gonadotrophin stimulation and GnRHa treatment, human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) is administered to trigger ovulation and 34 to 36 hours later, oocyte retrieval is undertaken and the egg is fertilised outside the body. Following fertilisation, the embryos are either transferred on day two or three (cleavage stage) or on day five or six (blastocyst stage). Luteal phase support is typically provided as a progestogen or a hCG treatment, or as a combination.

Description of the intervention

Oral contraceptive pills (OCP) are widely used by women of different ages to prevent pregnancy. They are also indicated for a range of menstrual and gynaecological conditions, such as acne vulgaris, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and menorrhagia (Arowojolu 2007; Harwood 2007; Irvine 1999). Combined oral contraceptive pills (COCP) consisting of oestrogen and progestogen reduce the women's own production of FSH and LH by way of a negative feedback (Cohen 1979; Gaspard 1984). The COCP suppresses gonadal function and, in the absence of an LH‐surge, no flare‐up or premature ovulation will occur. Only progestogen has a contraceptive effect (Erkkola 2007). Progestogen has the ability to slow GnRH pulsatility of the pituitary gland, thereby reducing gonadotrophin surges and, according to dose, inhibiting ovulation (Anderson 1990; Erkkola 2007; Le Nestour 1993; Moudgal 1985). Oestrogen is added to the COCP to regulate the bleeding patterns, though it is also capable of reducing FSH levels (De Ziegler 1998; Le Nestour 1993).

Most of progestogen‐only pills do not inhibit ovulation although higher doses of progestogen may do so (Erkkola 2007).

How the intervention might work

The COCP given prior to gonadotrophin in an IVF cycle assists synchronisation of follicular development and prevents occurrence of spontaneous LH‐surges (Gonen 1990). Huirne reported similar data as well as a reduction of the occurrence of large follicles prior to day eight (Huirne 2006a). In another study, both the COCP and progestogen had a suppressive effect on LH and FSH secretion. However, oestrogen administration (at 4 mg/day) did not suppress serum LH and FSH concentrations (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007).

The resulting pituitary suppression of COCPs in GnRH antagonist cycles is associated with slower follicular growth and lower serum oestradiol levels than in antagonist cycles with no pretreatment in the early part of the cycle. This results in a longer duration of rFSH stimulation and a higher total rFSH consumption than in antagonist cycles without pretreatment (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007).

COCP pretreatment in an ovarian stimulation protocol before IVF can reduce cyst formation, shorten the length of GnRHa treatment and reduce the amount of gonadotrophin needed, without negatively affecting the pregnancy rate (Biljan 1998a). Pituitary suppression seems to occur earlier with progestogen pretreatment and fewer ovarian cysts are formed, when compared with no pretreatment (Engmann 1999). COCP pretreatment can be used for scheduling oocyte retrieval on days of the working week, which is important with antagonist cycles (Barmat 2005; Gonen 1990; Huirne 2006b). Scheduling is of benefit for the clinicians and people in the laboratory, since these people usually do not work on weekends.

Why it is important to do this review

There is some debate regarding the effects of the COCP upon pregnancy rate. Higher rates of clinical pregnancy and live birth have been reported when dual suppression protocols and GnRHa were compared to a GnRHa protocol without the use of oral contraceptives in non‐randomised studies (Damario 1997; Keltz 2007). However, other non‐randomised studies have found no evidence of effect with regard to pregnancy rate (Bellver 2007; Galera 2004).

There is a lack of consensus regarding whether pretreatment with COCP in ovarian stimulation protocols improves rates of pregnancy and live birth. Furthermore, the effects of pretreatment with progestogen or oestrogen alone on IVF outcomes is unclear. The results of many small RCTs can be pooled in a systematic review and may provide a more definitive answer regarding the role of the COCP, progestogens or oestrogens in ART.

Objectives

To determine whether pretreatment with the combined oral contraceptive pill or with a progestogen or oestrogen alone in ovarian stimulation protocols affects outcomes in subfertile couples undergoing ART.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in this review. We included both published and unpublished studies and we excluded trials with quasi‐randomisation.

We excluded cross‐over trials unless pre‐crossover data were available; this type of design is inappropriate in this context.

Types of participants

Women of any age with subfertility, regardless of any cause, undergoing ART.

We only excluded two types of participants from this review. The first was women with premature ovarian failure, because these women require a different ovarian stimulation protocol. The second was women who participated in ovarian stimulation protocols as oocyte donors.

Types of interventions

Pretreatment with COCPs, progestogens or oestrogens versus no pretreatment or alternative pretreatments, in GnRH agonist or antagonist cycles. We excluded studies that compared different doses of the same pretreatment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Live birth or ongoing pregnancy (in studies not reporting live birth) per woman randomized.

Live birth defined as the delivery of a foetus with signs of life after 20 completed weeks of gestational age, counted as live birth event. When there were multiple live births (e.g. twins or triplets), we counted these as one live birth event (Griffin 2002).

Ongoing pregnancy defined as evidence of a gestational sac with foetal heart motion at 12 weeks or later, confirmed with ultrasound. When there were multiple gestational sacs in one woman, we counted these as one ongoing pregnancy (Griffin 2002).

Pregnancy loss (miscarriage) per woman randomized ‐ defined as the sum of the number of spontaneous abortions (pregnancy loss before 20 completed weeks of gestation) and the number of stillbirths (pregnancy loss after 20 completed weeks of gestation) (Griffin 2002).

Secondary outcomes

Clinical pregnancy rate per woman randomized ‐ defined as evidence of a gestational sac with foetal heart motion at six weeks or later, confirmed with ultrasound. When there were multiple gestational sacs in one woman, we counted these as one clinical pregnancy (Griffin 2002).

Multiple pregnancy rate per woman randomized.

OHSS rate per woman randomized, as defined in the included studies.

Number of oocytes retrieved per woman randomized.

Days of gonadotrophin treatment per woman randomized.

Amount of gonadotrophins administered per woman randomized.

Ovarian cyst formation rate per woman randomized ‐ defined as any intraovarian sonolucent structure with a mean diameter of 15 mm or more confirmed with ultrasound at least one week after start pituitary suppression (Biljan 1998a).

Search methods for identification of studies

We obtained all studies that described (or might have described) RCTs of pretreatment with COCP, progestogen or oestrogen therapy prior to GnRHa (agonists or antagonists) and gonadotrophins or gonadotrophins alone in women undergoing IVF, using the following search strategies.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases:

the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group (CGF) Specialised Register, searched on Procite platform from inception to 16 January 2017 (Appendix 2);

Cochrane Central Register of Studies Online (CENTRAL CRSO) searched 16 January 2017 on web platform (Appendix 3);

MEDLINE; searched on Ovid platform 1946 to 16 January 2017 (Appendix 4). We combined this search with the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomized trials (Higgins 2011);

Embase; searched on Ovid platform 1980 to 16 January 2017 (Appendix 5). We combined this search with trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN);

PsycINFO; searched on the Ovid platform from 1806 to 16 January 2017 (Appendix 6);

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL Plus); searched on the Ebsco platform from 1982 to 16 January 2017 (Appendix 7). We combined this search with trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN).

We place no restrictions by language. We managed output of these searches with the reference manager, Endnote (EndNote). Through this program, duplicates can be found and removed.

Searching other resources

In addition, we searched some other resources than the electronic databases mentioned above to obtain more relevant trials. We accessed all the websites on 13 January 2017, except for OpenSIGLE.

Trial registers for ongoing and registered trials: Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com), ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov), and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Trials Registry Platform Search Portal (www.who.int/trialsearch) (Appendix 8).

The Virtual Health Library.

Citation indexes (scientific.thomson.com/products/sci).

PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed); we combined this search with random control filters for PubMed (Higgins 2011).

Conference abstracts on the ISI Web of Knowledge (isiwebofknowledge.com).

Open System for Information on Grey Literature (opensigle.inist.fr, accessed on 16 January 2017).

Reference lists of appropriate studies.

Handsearching of the abstracts of the 32nd annual meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology in Helsinki (Finland), 3 to 6 July 2016 (ESHRE 2016).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (ROA, AL) independently scanned the titles and abstracts of all the studies found with the search to exclude those that did not meet the inclusion criteria. We discussed any disagreement or doubt, whether a study was eligible for inclusion or not, with a third review author (CF) to achieve consensus. We obtained the full text of those RCTs deemed eligible for inclusion where possible, and subjected them to critical appraisal of their risk of bias. Where appropriate, we included them in this systematic review.

Subsequently, we constructed a Characteristics of included studies table for those trials considered suitable for inclusion. We produced a Characteristics of excluded studies table for those that did not satisfy the inclusion criteria. In this table, we listed the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (ROA, AL) independently extracted the data using data extraction forms, which we designed for this particular review (Appendix 9; Appendix 10). We resolved any discrepancies by discussion and the help of a third review author (CF).

The data extraction forms included risk of bias criteria and methodological details. The information about the studies is included in the review and presented in the Characteristics of included studies table. We managed the data using Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed and reported on the risk of bias of included studies in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), which recommends the explicit reporting of the following domains.

Sequence generation

Was sequence generation adequate (e.g. use of a random number table, a computer random number generator or coin tossing) or unclear (insufficient information about the process of sequence generation)?

Allocation concealment

Was allocation concealment adequate (e.g. use of central allocation or opaque sealed envelopes), inadequate (e.g. use of an open random allocation schedule, date of birth or case record number) or unclear (insufficient information about the process of allocation concealment)?

Blinding of participants, providers and outcome assessors

Was blinding adequate (e.g. participants and researchers were all blinded and it was unlikely that blinding could have been broken, either participants or some researchers were not blinded but outcome assessment was blinded or no blinding was used but this was not likely to influence outcomes), inadequate (e.g. no blinding or incomplete blinding and outcomes were likely to be influenced by this) or unclear (insufficient information about the process of blinding)?

Incomplete outcome data

Were outcome data addressed adequately (e.g. there were no missing outcome data, reasons for missing outcome data were unlikely to be related to true outcome or missing outcome data were balanced in numbers across intervention groups), inadequate (e.g. reasons for missing outcome data were likely to be related to true outcome) or unclear (insufficient information about the process of addressing outcome data)?

Selective outcome reporting

Was the study free of selective reporting? Adequate (e.g. the study protocol was available and all prespecified outcomes were reported or the study protocol was not available but it was clear that all prespecified outcomes were reported), inadequate (e.g. not all prespecified primary outcomes were reported) or unclear (insufficient information about the process of outcome reporting).

Other sources of bias for RCTs

Was the study free of other bias? Adequate (the study seemed to be free of other bias, e.g. comparable demographic characteristics between treatment groups), inadequate (e.g. extreme baseline imbalance, a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used or early stopping) or unclear (insufficient information about other sources of bias).

By using a simple form (Appendix 9; Appendix 10), two review authors separately assessed these domains as 'low' (indicating a low risk of bias), 'unclear' (indicating an uncertain risk of bias) or 'high' (indicating a high risk of bias).

The assessments of the two review authors (ROA, AL) were compared and we resolved any discrepancies in the interpretation of the risk of bias of a study by discussion with a third review author (CF). We did not exclude any study as a result of a rating of 'Unclear' or 'High'. Where it was unclear, we contacted authors of studies about the methods used and also sought any missing data.

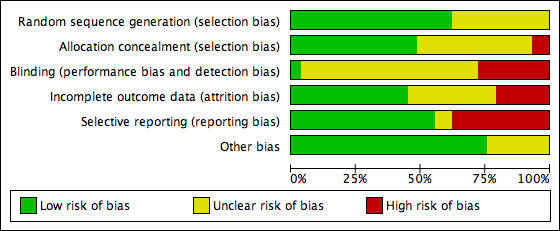

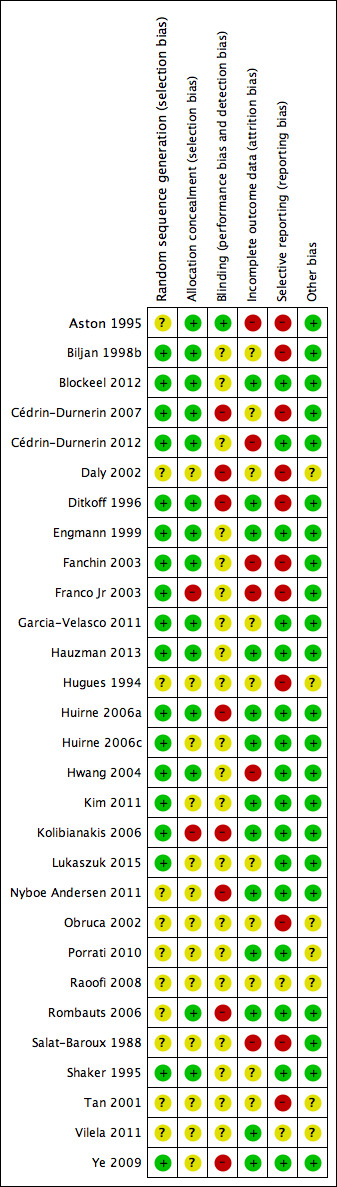

We presented the results of the risk of bias assessment in the Characteristics of included studies table, including commentary about each of the domains. This led to a methodological quality summary (Figure 1; Figure 2).

1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, we expressed results for each study as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For continuous variables, we reported the data as mean differences (MD) with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

To avoid analysis errors, we only pooled data that reported outcomes per woman randomized. Studies that reported 'per cycle' data were eligible for inclusion but were not included in the analyses; however, additional information was provided on such studies narratively.

Dealing with missing data

In case of missing data in the included studies, we contacted the original investigators by e‐mail or post to request relevant missing information. If we did not receive a reply, we sent a reminder to the authors two weeks later. Furthermore, we contacted the members of the CGF group to ask if they know any of the authors personally or have contact details.

We reported the data according to intention‐to‐treat (ITT) where possible. We reported live birth and ongoing pregnancy as a single outcome (i.e. live birth or ongoing pregnancy due to non‐reporting of live birth data by some studies who reported data on ongoing pregnancy). However, where a study reported data on both outcomes, we only included data for live birth in the analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Before any meta‐analysis was done, we judged whether there was sufficient similarity between the eligible studies in their design and clinical characteristics to ensure that pooling was valid. We assessed statistical heterogeneity in the results of trials using the Chi2 test. A low P value (or a large Chi2 statistic relative to its degree of freedom) potentially provides evidence of heterogeneity of intervention effects and shows that results are not influenced by chance alone (Higgins 2011). We used the I2 statistic to assess the impact of the heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis. We interpreted the result of the I2 statistic as follows:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; and

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

If we found marked clinical or statistical heterogeneity (I2 more than 50%), we explored reasons for this heterogeneity using a sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulty of detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, we aimed to minimise their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible studies and by being alert for duplication of data. If there were 10 or more studies in an analysis, we intended to use a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small‐study effects (a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies), but, due to the small number of studies per analysis, this was not possible.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where studies were sufficiently similar.

Comparisons were grouped separately by type of pretreatment (COCP, progesterone, oestrogen) and type of comparator (no pretreatment or alternative pretreatment) and the primary analysis was subgrouped by type of downregulation (antagonist or agonist).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where data were available, we subgrouped the data to determine the separate evidence within the following subgroups.

-

Types of downregulating agents:

GnRH agonist in study group versus GnRH agonist in control group;

GnRH antagonist in study group versus GnRH antagonist in control group;

GnRH antagonist in study group versus GnRH agonist in control group;

GnRH agonist in study group versus GnRH antagonist in control group.

Women who were low responders (i.e. who responded poorly to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation).

Where we detected substantial heterogeneity (I2 greater than 50%), we explored possible explanations in sensitivity analyses. We took any statistical heterogeneity into consideration when interpreting the results especially if there were any variations in the direction of effect estimates.

Sensitivity analysis

We intended to conduct sensitivity analysis for the primary outcomes (live births or ongoing pregnancies and pregnancy losses) to determine whether the conclusions were robust to the choice of statistical model (fixed versus random) or summary effect measure (OR or risk ratio).

Overall quality of the body of evidence: 'Summary of findings' table

We prepared 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADEpro (GRADEpro GDT 2014) and Cochrane methods. These tables evaluated the overall quality of the body of evidence for the main review outcomes:

live birth or ongoing pregnancy;

pregnancy loss;

multiple pregnancy;

OHSS.

The tables evaluated the main review comparisons:

COCP compared to no pretreatment;

progestogen compared to no pretreatment;

oestrogen compared to no pretreatment.

We assessed the quality of the evidence using GRADE criteria: risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias). Two review authors (ROA, AL) independently made judgements about evidence quality (high, moderate, low or very low) and resolved disagreements by discussion. Judgements were justified, documented and incorporated into reporting of results for each outcome.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

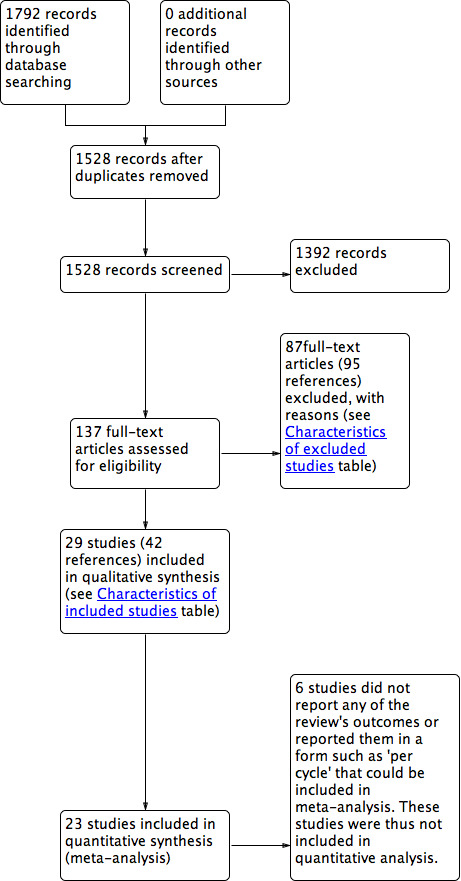

After searching the electronic databases, we found 1792 studies: 609 studies in the GF specialized register of controlled trials, 166 studies in CENTRAL, 511 studies in MEDLINE, 463 studies in Embase, 19 studies in CINAHL and 24 studies in PsycINFO. After removing the duplicates and searching other resources, there were 1528 studies left. We retrieved 137 full‐text articles of which 29 studies (42 references) were included and 87 studies (95 references) were excluded. For further details on included/excluded studies, see Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables. The process involved in the screening and selection of eligible studies for inclusion is shown in the PRISMA flow chart (Moher 2009) (Figure 3).

3.

Study PRISMA flow chart

Included studies

Nine of the included studies were identified from the searches carried out in 2015 and 2016 (Blockeel 2012; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hauzman 2013; Kim 2011; Lukaszuk 2015; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Porrati 2010; Vilela 2011). The remaining 20 studies were identified from the previous updates of the review.

The following is a summary of the methods, participants, interventions and outcomes of the included studies. Full details of these domains (for each study separately) are in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Methods

We included 29 trials, with 4702 women randomized to treatment (Aston 1995; Biljan 1998b; Blockeel 2012; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Daly 2002; Ditkoff 1996; Engmann 1999; Fanchin 2003; Franco Jr 2003; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hauzman 2013; Hugues 1994; Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Hwang 2004; Kim 2011; Kolibianakis 2006; Lukaszuk 2015; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Obruca 2002; Porrati 2010; Raoofi 2008; Rombauts 2006; Salat‐Baroux 1988; Shaker 1995; Tan 2001; Vilela 2011; Ye 2009). Two of the included studies were three‐arm parallel RCTs (Kim 2011; Rombauts 2006), one was a four‐arm RCT (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007), and the remaining 26 studies were two‐arm parallel RCTs.

The largest trials were Kolibianakis 2006 (504 women), Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012 (472 women), Nyboe Andersen 2011 (442 women), Rombauts 2006 (351 women), Lukaszuk 2015 (298 women), Garcia‐Velasco 2011 (228 women), Ye 2009 (220 women) and Vilela 2011 (210 women). The remainder included fewer than 200 women. Only one study used a cross‐over design and reported pre‐cross‐over data (Daly 2002). The remaining 28 trials used a parallel design. Four studies were conducted in multiple centres (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Rombauts 2006).

The trials took place in (or authors came from): Argentina (Porrati 2010; Vilela 2011); France (Cédrin‐Durnerin 1996; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Fanchin 2003; Hugues 1994; Salat‐Baroux 1988); UK (Aston 1995; Shaker 1995); Canada (Biljan 1998b; Tan 2001); UK and Canada (Engmann 1999); USA (Daly 2002; Ditkoff 1996); USA and Europe (Nyboe Andersen 2011); Austria (Obruca 2002); Belgium (Blockeel 2012; Kolibianakis 2006); Brazil (Franco Jr 2003); China (Ye 2009); Iran (Raoofi 2008); South Korea (Kim 2011); Taiwan (Hwang 2004); Australia, Denmark, Jordan and Norway (Rombauts 2006); the Netherlands and Belgium (Huirne 2006a); Spain (Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hauzman 2013); Poland (Lukaszuk 2015); Egypt, Iran, the Netherlands, Belgium, France and Austria (Huirne 2006c).

Of the 29 included studies, 13 performed and adhered to a power calculation (Aston 1995; Biljan 1998b; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Engmann 1999; Fanchin 2003; Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Hwang 2004; Kim 2011; Kolibianakis 2006; Lukaszuk 2015; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Rombauts 2006). Seven studies did not adhere to a power calculation (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Ditkoff 1996; Franco Jr 2003; Hauzman 2013; Raoofi 2008; Salat‐Baroux 1988; Shaker 1995), and in other studies this was unclear because there was only an abstract available or it was not reported.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Of the 29 studies, 25 RCTs included women with a regular IVF/ICSI indication while four RCTs included women who had special indications for IVF: one trial included women who were low responders (i.e. women who respond poorly to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (Kim 2011)); one included women with limited ovarian reserve (Daly 2002); one included women with PCOS (Hwang 2004); and another one included women with an ovarian cyst of over 5 mm in diameter or an endometrial thickness of over 5 mm and serum oestradiol concentration greater than 100 pmol/L after 14 days of GnRH agonist treatment (Shaker 1995).

Twenty‐one studies mentioned an age limit as an inclusion criteria. Eight studies only included women aged 38 years or less (Blockeel 2012; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Franco Jr 2003; Hauzman 2013; Huirne 2006a; Salat‐Baroux 1988; Ye 2009). Nine studies only included women aged 39 years or less (Fanchin 2003; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Huirne 2006c; Hwang 2004; Kolibianakis 2006; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Porrati 2010; Rombauts 2006; Vilela 2011). One study included women less than 40 years (Lukaszuk 2015). The other three studies used age limits above 40 years of age: one study used an upper limit of 41 years of age (Daly 2002), one study an upper limit of 42 years of age (Cédrin‐Durnerin 1996), and one study used an upper limit of 44 years of age (Engmann 1999). Six of these 21 studies defined lower limits of 18 years of age (Engmann 1999; Hauzman 2013; Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Rombauts 2006).

Other common inclusion criteria were the presence of regular menstrual cycles (Blockeel 2012; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Fanchin 2003; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hauzman 2013; Huirne 2006a; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Rombauts 2006; Ye 2009), and a body mass index (BMI) between 18 kg/m2 and 25 kg/m2 (Ye 2009), or less than 30 kg/m2 (Blockeel 2012; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Fanchin 2003; Hauzman 2013; Huirne 2006a; Kolibianakis 2006; Rombauts 2006).

Exclusion criteria

Nine studies excluded women with an evidence of poor response. Two studies defined poor response as any previous ART cycles with less than three oocytes (Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c), Huirne 2006a also excluded women if they had a history of three or more consecutive ART cycles without a clinical pregnancy. One study defined poor response as development of fewer than four follicles in previous IVF or ICSI cycles (Blockeel 2012). Three studies defined poor response as fewer than five oocytes in a previous IVF attempt or fewer than five follicles in a spontaneous cycle (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Hauzman 2013), and one study defined poor response as more than three unsuccessful controlled ovarian stimulation cycles or a history of low or no ovarian response during FSH/hMG (Rombauts 2006). Two studies did not mention how they defined poor response to ovarian stimulation (Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Kolibianakis 2006).

Other common exclusion criteria were: a high baseline serum FSH level (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Ditkoff 1996; Engmann 1999; Huirne 2006a; Hwang 2004; Kolibianakis 2006; Nyboe Andersen 2011), evidence of ovarian cysts or endometrioma (Aston 1995; Engmann 1999; Kolibianakis 2006), and PCOS (Blockeel 2012; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hauzman 2013; Huirne 2006a; Kim 2011; Porrati 2010; Rombauts 2006; Vilela 2011).

Interventions

Three of the 29 studies had more than two study arms and were used in more than one comparison (four arms: Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; three arms: Kim 2011; Rombauts 2006).

Combined oral contraceptive pill versus placebo or no pretreatment

In 17 trials (with 19 comparisons), the study group received pretreatment with a COCP, while the control group received no pretreatment. None of these studies used a placebo in the control group. Ten trials used ethinyl oestradiol as the oestrogen component in a daily dose of 30 μg (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Kim 2011; Kolibianakis 2006; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Obruca 2002; Raoofi 2008; Rombauts 2006); seven trials used desogestrel 150 μg daily (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Kolibianakis 2006; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Obruca 2002; Raoofi 2008; Rombauts 2006); three trials used levonorgestrel 150 μg daily as the progestogen component (Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Kim 2011); one trial used Diane‐35, which contained ethinyl oestradiol 35 μg and cyproterone acetate 2 mg (Hwang 2004); and two trials used a combination of ethinyl oestradiol 20 μg and levonorgestrel 100 μg (Porrati 2010; Vilela 2011). For other studies, there were not enough data available on the type of COCP used.

The starting days of pretreatment in 10 of the trials varied from cycle day one to five. Five studies started COCP pretreatment on cycle day one (Biljan 1998b; Kolibianakis 2006; Obruca 2002; Raoofi 2008; Rombauts 2006); two studies started the pretreatment on cycle day two or three (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Huirne 2006a); one study started the pretreatment on a variable cycle day from one to five (Huirne 2006c); and one study started the pretreatment on cycle day five (Hwang 2004). There were not enough data available from five trials on the start day of pretreatment (Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Kim 2011; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Porrati 2010; Vilela 2011).

The duration of pretreatment in the 17 trials varied from 12 days to three consecutive cycles. Five studies used a fixed duration of 14 days of pretreatment (Biljan 1998b; Kolibianakis 2006; Raoofi 2008), or 21 days of pretreatment (Kim 2011; Porrati 2010); five studies used a variable duration of pretreatment of 12 to 16 days (Garcia‐Velasco 2011), 14 to 21 days (Nyboe Andersen 2011), 14 to 25 days (Vilela 2011), and 14 to 28 days (Huirne 2006a; Rombauts 2006). Three other studies used a variable duration of around two or three weeks minimum to around four weeks maximum (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007, 15 to 21 days; Obruca 2002, 18 to 28 days; Huirne 2006c, 21 to 28 days). Hwang 2004 used the longest pretreatment duration of three consecutive cycles.

Two studies used agonists in both treatment groups. One study used buserelin acetate (long protocol) (Biljan 1998b) and one used a depot of triptorelin acetate (Raoofi 2008).

Ten studies used antagonists in both treatment groups. Four studies used ganirelix acetate (Blockeel 2012; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Kolibianakis 2006; Rombauts 2006); three studies used cetrorelix acetate (Obruca 2002; Porrati 2010; Vilela 2011); one study used antide (Huirne 2006a); one study, a three‐arm parallel RCT, used cerotide in two of the treatment arms and a GnRH agonist in the second control arm (Kim 2011), and one study did not mention which GnRH antagonist was used (Nyboe Andersen 2011).

Four trials used an antagonist in the study group and an agonist in the control group. Two trials used cetrorelix acetate as antagonist and buserelin acetate as agonist (Huirne 2006c; Hwang 2004), and one used ganirelix acetate as antagonist and nafarelin acetate as agonist (Rombauts 2006). The other study did not mention which antagonists and agonists were used (Garcia‐Velasco 2011).

Progestogen versus placebo or no pretreatment

In seven trials, the study group was given a pretreatment with a progestogen, while the control group received placebo (Aston 1995), or no pretreatment (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Ditkoff 1996; Engmann 1999; Hugues 1994; Salat‐Baroux 1988; Shaker 1995). Four studies used norethisterone 10 mg daily (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Ditkoff 1996; Engmann 1999; Hugues 1994), one study used medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg daily (Aston 1995), and one study used ethynodiol acetate 4 mg daily (Salat‐Baroux 1988). Another study used a single injection of 100 mg, but did not mention what type of progestogen they used (Shaker 1995).

The starting days of pretreatment in all seven trials varied from cycle day one to 19. Two studies started the pretreatment with progestogen on cycle day one (Ditkoff 1996; Engmann 1999), two studies on cycle day 15 (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Salat‐Baroux 1988), one study on cycle day 16 or 17 (Shaker 1995), and one study on cycle day 19 (Aston 1995). There were not enough data available from one study on the start day of pretreatment (Hugues 1994).

The duration of progestogen pretreatment varied from one to 21 days. In one study, the women received one single injection (Shaker 1995). One study used a duration of pretreatment of five days (Engmann 1999), one study used seven days (Aston 1995), and one study used eight days (Ditkoff 1996). Two trials used a variable duration of 10 to 15 days (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Hugues 1994), and one trial used 11 to 17 days (Salat‐Baroux 1988).

Six trials used an agonist in both treatment groups. Three studies used buserelin acetate (Aston 1995; Engmann 1999; Shaker 1995), one study used triptorelin (Cédrin‐Durnerin 1996), one study used leuprolide acetate (Ditkoff 1996), and one study used dTRP6‐LHRH (Hugues 1994).

One trial used an antagonist (ganirelix acetate) in both treatment groups (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007).

One trial did not use GnRH analogues for pituitary desensitisation. Women that participated in this study only received pure FSH and hMG (Salat‐Baroux 1988).

Oestrogen versus placebo or no pretreatment

In five trials, the study group was given a pretreatment with oestrogen, while the control group received no pretreatment. Three studies used 17β‐oestradiol (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Fanchin 2003), and two studies used oestradiol valerate (Franco Jr 2003; Ye 2009). All these studies used 4 mg daily.

The starting days of pretreatment varied from cycle day 15 to 21. One study started the pretreatment on cycle day 20 (Fanchin 2003), and two on cycle day 21 (Franco Jr 2003; Ye 2009). One study started pretreatment seven days before the presumed onset of menses and administered up to the next Thursday after the occurrence of menstrual bleeding (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012). One remaining study started the pretreatment 10 days before the presumed menses (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007).

The duration of pretreatment varied from 10 to 17 days. In two studies the duration varied from 7 to 15 days (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012). Three studies used a fixed duration of pretreatment of 10 days (Ye 2009), 11 days (Fanchin 2003), and 14 days (Franco Jr 2003).

Three trials used an antagonist in both treatment groups, one trial used ganirelix acetate (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007), one trial used cetrorelix acetate (Fanchin 2003), and one trial did not report the name of the antagonist (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012).

Two trials used an antagonist in the intervention group and an agonist in the control group, one trial used ganirelix acetate in the intervention group and nafarelin acetate in the control group (Franco Jr 2003), and one study used cetrotide in the intervention group and triptoreline in the control group (Ye 2009).

Combined oral contraceptive pill versus progestogen

There was only one study that compared COCP with progestogen (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007). The women in the COCP group received ethinyl oestradiol 30 μg plus desogestrel 150 μg daily and the women in the progestogen group received norethisterone 10 mg daily. This study started the COCP pretreatment on cycle day two or three with a duration of 15 to 21 days. The progestogen pretreatment was started on cycle day 15 with a duration of 10 to 15 days. Both groups received the GnRH antagonist, ganirelix acetate.

Combined oral contraceptive pill versus oestrogen

Four trials compared a pretreatment of COCP with a pretreatment of oestrogen. One trial used ethinyl oestradiol 30 μg plus desogestrel 150 μg daily as a COCP and micronised 17β‐oestradiol 4 mg daily as oestrogen pretreatment (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007). The COCP pretreatment started on cycle day two or three with a duration of 15 to 21 days. The oestrogen pretreatment started 10 days before the presumed menses with a duration of 10 to 15 days and both groups received the GnRH antagonist, ganirelix acetate. Another study used ethinyl oestradiol 30 μg plus levonorgestrel 150 μg daily as a COCP and oestradiol valerate 4 mg daily as oestrogen pretreatment (Hauzman 2013). The COCP pretreatment started on cycle day one or two and continued for 12 to 16 days. The oestrogen pretreatment started from day 20 of menstrual cycle for five to 12 days until the day before starting stimulation and both groups received the GnRH antagonist, ganirelix acetate. One study used ethinyl oestradiol plus desogestrel as COCP starting from day two to four of the cycle but their doses were not reported (Lukaszuk 2015). In the control group, women were pretreated with oral oestradiol 2 mg twice daily from the day 20 of the natural cycle to day one to four of the new cycle. Both groups received the GnRH agonist, triptorelin. One study did not mention which COCP was used, but used ethinyl oestradiol 2 mg as an oestrogen pretreatment (Daly 2002). This study only described that the oestrogen pretreatment was administered in the luteal phase of the preparation cycle, but did not report the exact starting days and durations of pretreatment. The COCP group received the GnRH agonist, leuprolide acetate, and the oestrogen group received the GnRH antagonist, ganirelix acetate.

Progestogen versus oestrogen

There was only one study that compared progestogen with oestrogen (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007). The women in the progestogen group received norethisterone 10 mg daily and the women in the oestrogen group received micronised 17β‐oestradiol 4 mg daily. This study started the progestogen pretreatment on cycle day 15 with a duration of 10 to 15 days. The oestrogen pretreatment started 10 days before the presumed menses with also a duration of 10 to 15 days. Both groups received the GnRH antagonist, ganirelix acetate.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

Fifteen studies reported the number of live births or ongoing pregnancies (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Daly 2002; Ditkoff 1996; Engmann 1999; Franco Jr 2003; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hauzman 2013; Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Kim 2011; Kolibianakis 2006; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Rombauts 2006; Ye 2009). Three studies defined ongoing pregnancy as a positive heart activity at a gestational age of 12 weeks (Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Kim 2011). One study used the same definition but did not mention when they performed the ultrasound scan (Ditkoff 1996). Two studies defined ongoing pregnancy as a pregnancy developing beyond 12 weeks (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Kolibianakis 2006), and one study defined ongoing pregnancy as a pregnancy assessed by ultrasound at 12 to 16 weeks or later (Rombauts 2006). The remaining studies did not mention how they assessed ongoing pregnancy (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Daly 2002; Engmann 1999; Franco Jr 2003; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hauzman 2013; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Ye 2009).

Ten studies reported the number of pregnancy losses. One study described this as the proportion of women with initially positive hCG in whom pregnancy failed to develop beyond 12 weeks of gestation (Kolibianakis 2006). The other nine studies did not describe a definition (Daly 2002; Engmann 1999; Franco Jr 2003; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hwang 2004; Kim 2011; Rombauts 2006; Salat‐Baroux 1988; Ye 2009).

Secondary outcomes

Twenty‐one studies reported the number of clinical pregnancies. Three studies defined clinical pregnancy as the presence of one or more foetal hearts confirmed with ultrasound, performed at least four weeks after embryo transfer (Fanchin 2003 or from six weeks after embryo transfer (Franco Jr 2003; Kim 2011). Two other studies used the same definition, but one of these also included the foetal sacs without heart activity (Huirne 2006c), and the other performed the ultrasound scan at seven weeks after embryo transfer (Hwang 2004). One study defined clinical pregnancy as the presence of one or more intrauterine sacs confirmed with ultrasound, at a gestational age of six weeks (Huirne 2006a). In one study, we used a positive pregnancy test with evidence of a gestational sac to define clinical pregnancy, because no clinical or ongoing pregnancy rate was available (Engmann 1999). One study defined clinical pregnancy as the evidence of a clinical gestational sac (Ditkoff 1996). In the other 12 studies, it was unclear how they defined this outcome (Aston 1995; Blockeel 2012; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Daly 2002; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hauzman 2013; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Obruca 2002; Porrati 2010; Salat‐Baroux 1988; Ye 2009). If no clinical pregnancy rates were reported, we used the ongoing pregnancy rates (if available) for our analysis.

Ten studies reported the number of oocytes retrieved (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Ditkoff 1996; Franco Jr 2003; Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Hwang 2004; Kim 2011; Obruca 2002; Rombauts 2006; Salat‐Baroux 1988). One study only mentioned the number of cumulus‐oocyte complexes (Kolibianakis 2006), and two studies mentioned the number of mature oocytes or follicles (Engmann 1999; Fanchin 2003), but we assumed that this meant the same as the number of oocytes retrieved and, therefore, we pooled the data of these studies.

Thirteen studies reported the number of days of gonadotrophin treatment (Blockeel 2012; Ditkoff 1996; Engmann 1999; Franco Jr 2003; Hauzman 2013; Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Hwang 2004; Kim 2011; Kolibianakis 2006; Porrati 2010; Rombauts 2006; Vilela 2011).

Thirteen studies reported the amount of gonadotrophins administered (Blockeel 2012; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Fanchin 2003; Franco Jr 2003; Hauzman 2013; Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Kim 2011; Kolibianakis 2006; Porrati 2010; Rombauts 2006; Vilela 2011). Two studies reported the amount of gonadotrophins administered in the number of ampoules used, but we could not use these data in our analysis (Ditkoff 1996; Engmann 1999).

Other adverse outcomes

Six studies reported the number of women with ovarian cysts. In one study, we used the number of functional ovarian cysts with a diameter of 10 mm or more, measured after one week of GnRH agonist treatment (Engmann 1999). Three studies defined an ovarian cyst as an intraovarian sonolucent structure with a mean diameter of 14 mm or more, measured after seven days (Aston 1995) or eight days (Ditkoff 1996) of pituitary suppression, or on a day not specified (Franco Jr 2003). One study did not mention how they defined ovarian cyst formation and when they measured this (Huirne 2006a). One study only reported cyst formation as a reason for cycle cancellation, but it was unclear if there were more cysts formed that did not lead to cycle cancellation (Salat‐Baroux 1988). We did not use these data in our analysis.

Six studies reported the number of multiple pregnancies. One study defined multiple pregnancies as multiple clinical pregnancies (Huirne 2006c). One study described the number of ongoing or live born twin pregnancies (Hwang 2004). Four studies did not describe when the number of multiple pregnancies was measured (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Franco Jr 2003; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Kim 2011).

Five studies reported the number of women with OHSS. Two study used the WHO classification criteria to diagnose OHSS and divided the women in categories of mild (grade I), moderate (grade II) or severe (grade III) (Nyboe Andersen 2011; Rombauts 2006); the other three studies did not mention how they diagnosed OHSS (Franco Jr 2003; Hwang 2004; Ye 2009).

Six studies did not contribute data to the analyses: two of these studies reported 'per cycle' data and the numbers of cycles were not equivalent to the numbers of participants (Biljan 1998b; Shaker 1995); outcomes reported included clinical pregnancy rate, number of days of GnRH agonist and number of oocytes retrieved. One study reported outcome data in denominators other than 'per woman' such as 'per cycle', 'per embryo transfer' (Lukaszuk 2015), outcomes reported included clinical pregnancy, number of oocyte retrieved, multiple pregnancy, duration of stimulation days. Three studies had no available outcome data relevant to the review (Hugues 1994; Raoofi 2008; Tan 2001).

Excluded studies

A total of 86 studies that described pretreatments with COCPs, progestogens or oestrogens were not eligible for inclusion for various reasons. Some of these studies had multiple reasons for exclusion, but we reported the most important reason. Full details of reasons for exclusion can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Twenty studies did not randomise their participants using standardized randomization procedures such as a computer or a random number table (Benadiva 1988; Cédrin‐rDurnerin 1995; Cohen 1987; Copperman 2003; Couzinet 1995; Ditkoff 1997; Forman 1991; Frydman 1986; Galera 2004; Godin 2003; Gonen 1990; Lindheim 1996; Neal 1993; Palomba 2008; Schoolcraft 1997; Surrey 1989; Tarlatzis 1993; Wang 2016; Weisman 1989; Yokota 2006).

Twenty‐four studies used a retrospective design (al‐Mizyen 2000; Bellver 2007; Bendikson 2006; Biljan 1998c; Chung 2006; Damario 1997; Dickey 2001; Duvan 2008; Frederick 2004; Gonzalez 1995; Keltz 2007; Kovacs 2001; Leondires 1999; Loutradis 2003; Min 2005; Mirkin 2003; Pados 1995; Pinkas 2008; Ramsewak 2005; Talebian 2004; Talebian 2007; Wei 2016; Yoshida 2005; Zhao 2008).

In five studies, participants served as their own controls in previous cycles (Branigan 1998; Fanchin 2003b; Fisch 1996; Mulangi 1997; Surrey 1998).

There was insufficient information in five studies to determine their true randomization status (Aghahosseini 2011; Bakas 2014; Davar 2014; Engels 2011; Merviel 2015).

Three studies used a cross‐over design and there were no available pre‐cross‐over data (Cédrin‐Durnerin 1996; Fanchin 2001; Wang 2008).

Eight studies used a single‐arm design (Brodt 1993; De Ziegler 1999; Gerli 1989; Hugues 1992; Meldrum 2002; Meldrum 2008; Sanghvi 2002; Tehraninejad 2010).

Nine studies compared two (or more) different dosages, timings or ways of administration of the same pretreatment (Davy 2004; Gomez 2000; Haydardedeoglu 2012; Karande 2004; Kreiner 2007; Lewin 2002; Liu 2011; Mashiach 1989; Russell 1997).

Two studies used interventions that were administered for luteal phase support and not for pretreatment (Ghanem 2015; Rashidi 2011).

In three studies, women only received ovarian stimulation, but no embryo transfer was performed as part of an ART cycle (Anderson 1990; Letterie 2000; Steinkampf 1991).

In two studies, the women were oocyte donors (Doody 2001; Martinez 2006).

In one study, the women had premature ovarian failure (Tartagni 2007).

In two studies, pretreatment was not stopped before oocyte retrieval, but continued to be used as luteal phase support (Greco 2016; Jung 2000).

In one study, the main comparison was mild versus standard stimulation (with pretreatment in one group) (Youssef 2017).

Risk of bias in included studies

A complete overview of classification of risk of bias domains can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table and in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Allocation

Eighteen studies were at low risk of random sequence generation: 13 of these studies used computer generated random numbers to randomise the women (Biljan 1998b; Blockeel 2012; Engmann 1999; Fanchin 2003; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hauzman 2013; Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Hwang 2004; Kim 2011; Kolibianakis 2006; Lukaszuk 2015; Ye 2009), four studies used a table of random numbers (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Franco Jr 2003; Shaker 1995), and one study accomplished the randomization by tossing a coin (Ditkoff 1996). In the remaining 11 studies, there was insufficient information on the methods used in random sequence generation; they were thus rated at unclear risk of bias with respect to random sequence generation.

If randomization is not done correctly, there might be a difference in baseline characteristics between the women in the treatment groups. This may influence the outcomes measured in the trial. Therefore, it is important that the method of randomization is reported. Due to the high number of included studies that did not report the method of randomization (15/33 studies), there might be a higher risk of bias.

Fourteen studies were at low risk of allocation concealment: eight studies used sealed envelopes to conceal the allocation (Biljan 1998b; Blockeel 2012; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hauzman 2013; Hwang 2004; Shaker 1995); in five studies the allocation was done by a third party (Aston 1995, hospital pharmacy and numbered bottles; Engmann 1999, clinic nurses and sealed envelopes; Fanchin 2003, independent person; Huirne 2006a, independent person from independent monitoring company; Rombauts 2006, central remote allocation); one study centralised the randomization process (Ditkoff 1996).

Two studies were classified at high risk of allocation concealment, because they reported that the sequence of allocation was not concealed (Franco Jr 2003; Kolibianakis 2006). In the remaining 14 studies, there was insufficient information to make a conclusive judgement with respect to allocation concealment and these were rated at unclear risk of bias in this domain.

Most of the outcomes of this review were objectively assessed; thus a poorly designed allocation concealment method is not likely to have a big influence on these outcomes. For example, the number of live births is not likely to be influenced by the clinician if he or she knows which treatment the woman receives. However, some outcomes, such as OHSS, are diagnosed on clinical symptoms and so there might be a more important risk of bias when the clinician was aware of the treatment assigned to each woman. Nevertheless, outcomes that are objectively assessed may be influenced indirectly if allocation is not concealed.

Blinding

One study was at low risk of blinding because it was described as double blind and placebo controlled (Aston 1995).

In 20 studies, there was insufficient information with respect to blinding of clinicians, participants and outcome assessors; these studies were assessed at unclear risk with regard to blinding (Biljan 1998b; Blockeel 2012; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Engmann 1999; Fanchin 2003; Franco Jr 2003; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hauzman 2013; Hugues 1994; Huirne 2006c; Hwang 2004; Kim 2011; Lukaszuk 2015; Obruca 2002; Porrati 2010; Rombauts 2006; Salat‐Baroux 1988; Shaker 1995; Tan 2001; Vilela 2011).

The remaining eight studies were at high risk of bias because they were described as either open label or not blinded with personnel and participants having knowledge of the treatment allocation.

Poor blinding is less likely to influence the objective outcomes such as live birth, but it might have a bigger influence on the diagnosis of OHSS.

Incomplete outcome data

Of the 29 studies, 13 were at low risk of attrition bias (Blockeel 2012; Ditkoff 1996; Engmann 1999; Hauzman 2013; Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Kim 2011; Kolibianakis 2006; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Porrati 2010; Rombauts 2006; Vilela 2011; Ye 2009). In these trials, the proportions of, and reasons for, withdrawals were balanced between the treatment groups or data were analyzed using an ITT basis where all women randomized at baseline were included in the analysis.

In 10 studies, there were insufficient information with respect to the proportions of, and reasons for, withdrawals or losses to follow‐up and data were not analyzed on an ITT basis; these studies were rated at unclear risk of attrition bias (Biljan 1998b; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Daly 2002; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hugues 1994; Lukaszuk 2015; Obruca 2002; Raoofi 2008; Shaker 1995; Tan 2001).

The remaining six studies were at high risk of attrition bias because the proportions of, and reasons for, withdrawals were not balanced between the treatment groups and data were not analyzed by ITT.

Incomplete outcome data can bias the results of our review, especially with regard to adverse outcomes. For example, a study might have withdrawals due to OHSS that they do not report. Also imbalances in reasons for withdrawal can occur because of differences in interventions between the study group and control group. For example, when there are more withdrawals due to OHSS in the control group, this can be in favour of the intervention used in the study group. The risk of bias might increase if authors do not report this.

Selective reporting

We were unable to retrieve the protocol of any of the included studies to examine whether all prespecified outcomes were reported. However, we examined the Methods sections of the studies to determine whether outcomes planed in the Methods section were eventually reported. In this regard, we classified 16 studies at low risk of selective reporting because these trials reported data on all the outcomes mentioned in the 'Methods' section of their publication (Blockeel 2012; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Engmann 1999; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hauzman 2013; Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Hwang 2004; Kim 2011; Kolibianakis 2006; Lukaszuk 2015; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Porrati 2010; Rombauts 2006; Shaker 1995; Ye 2009). In two studies, there was insufficient information in the 'Methods' sections to make a conclusive judgement with respect to selective reporting of outcomes; therefore, they were rated at unclear risk of reporting bias (Raoofi 2008; Vilela 2011). In the remaining 11 studies, there was evidence of selective reporting as data were not reported on all the outcomes pre‐specified in the protocol or Methods section.

Other potential sources of bias

For other potential sources of bias, we examined the baseline demographic characteristics of participants, such as age and BMI, to determine whether there was substantial imbalance in baseline demographic characteristics between the treatment groups. In this regard, 22 studies were at low risk of bias in this domain because of the absence of substantial imbalance between in baseline demographic characteristics between the treatment groups (Aston 1995; Biljan 1998b; Blockeel 2012; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Cédrin‐Durnerin 2012; Ditkoff 1996; Engmann 1999; Fanchin 2003; Franco Jr 2003; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Hauzman 2013; Huirne 2006a; Huirne 2006c; Hwang 2004; Kim 2011; Kolibianakis 2006; Lukaszuk 2015; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Rombauts 2006; Salat‐Baroux 1988; Shaker 1995; Ye 2009).

The remaining seven studies were rated as being at unclear risk due to insufficient information to make a conclusive judgement with respect to baseline demographic characteristics in the treatment groups.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Combined oral contraceptive pill compared to no pretreatment for ovarian stimulation protocols for women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques.

| Combined oral contraceptive pill compared to no pretreatment for ovarian stimulation protocols for women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques | ||||||

|

Population: women undergoing ART Settings: ART clinic Intervention: COCP Comparison: no pretreatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk1 | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No pretreatment | COCP | |||||

|

Live birth or ongoing pregnancy (COCP + Ant vs Ant) |

270 per 1000 | 215 per 1000 (177 to 260) | OR 0.74 (0.58 to 0.95) | 1335 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 | ‐ |

|

Live birth or ongoing pregnancy (COCP + Ant vs Ag) |

296 per 1000 | 273 per 1000 (212 to 345) | OR 0.89 (0.64 to 1.25) | 724 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 | ‐ |

|

Pregnancy loss (COCP + Ant vs Ant) |

64 per 1000 | 85 per 1000 (53 to 134) | OR 1.36 (0.82 to 2.26) | 868 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 | ‐ |

|

Pregnancy loss (COCP + Ant vs Ag) |

103 per 1000 | 44 per 1000 (25 to 76) | OR 0.40 (0.22 to 0.72) | 780 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 | ‐ |

| Multiple pregnancy rate (COCP + Ant vs Ant) | 47 per 1000 | 98 per 1000 (25 to 313) | OR 2.21 (0.53 to 9.26) | 125 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low4 | ‐ |

| Multiple pregnancy rate (COCP + Ant vs Ag) | 147 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 (127 to 273) | OR 1.36 (0.85 to 2.19) | 546 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 | ‐ |

|

OHSS rate (COCP + Ant vs Ant) |

16 per 1000 |

16 per 1000 (4 to 52) |

OR 0.98 (0.28 to 3.40) |

642 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low4 | ‐ |

|

OHSS rate (COCP + Ant vs Ag) |

55 per 1000 |

35 per 1000 (11 to 102) |

OR 0.63 (0.20 to 1.96) |

290 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low4 | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Ag: agonist; Ant: antagonist; ART: assisted reproductive techniques; COCP: combined oral contraceptive pill; CI: confidence interval; OHSS: ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; OR: odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Mean baseline risk of control group. 2 Downgraded one level for serious risk of bias due to poor reporting of sequence generation and allocation concealment. 3 Downgraded one level for serious imprecision: effect estimate with wide confidence intervals or low event rate (or both). 4 Downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision: small sample size or very low event rate, and effect estimate with wide confidence intervals.

Summary of findings 2. Progestogen compared to placebo or no pretreatment for ovarian stimulation protocols for women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques.

| Progestogen compared to placebo or no pretreatment for ovarian stimulation protocols for women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques | ||||||

|

Patient or population: ovarian stimulation protocols for women undergoing ART Settings: Intervention: progestogen Comparison: placebo or no pretreatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk1 | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo or no pretreatment | Prog | |||||

|

Live birth or ongoing pregnancy (Prog + Ag vs Ag) |

170 per 1000 | 217 per 1000 (124 to 352) | OR 1.35 (0.69 to 2.65) | 222 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | ‐ |

| Live birth or ongoing pregnancy (Prog + Ant vs Ant) | 292 per 1000 | 217 per 1000 (69 to 512) | OR 0.67 (0.18 to 2.54) | 47 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | ‐ |

|

Pregnancy loss (Prog + Ag vs Ag) |

36 per 1000 | 78 per 1000 (24 to 220) | OR 2.26 (0.67 to 7.55) | 222 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | ‐ |

|

Pregnancy loss (Prog + Ant vs Ant) |

208 per 1000 | 86 per 1000 (16 to 354) | OR 0.36 (0.06 to 2.09) | 47 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | ‐ |

|

Multiple pregnancy rate (Prog + Ag vs Ag) |

No data available | ‐ | ‐ | |||

|

Multiple pregnancy rate (Prog + Ant vs Ant) |

42 per 1000 | 44 per 1000 (3 to 438) | OR 1.05 (0.06 to 17.76) | 47 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | ‐ |

|

OHSS rate (Prog + Ag vs Ag) |

No data available | ‐ | ‐ | |||

|

OHSS rate (Prog + Ant vs Ant) |

No data available | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Ag: agonist; Ant: antagonist; ART: assisted reproductive techniques; CI: confidence interval; OHSS: ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; OR: odds ratio; Prog: progestogen. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Mean baseline risk of control group. 2 Downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision: small sample size and effect estimate with wide confidence intervals.

Summary of findings 3. Oestrogen compared to no pretreatment for ovarian stimulation protocols for women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques.

| Oestrogencompared to no pretreatment for ovarian stimulation protocols for women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques | ||||||

|

Patient or population: ovarian stimulation protocols for women undergoing ART Settings: Intervention: oestrogen Comparison: no pretreatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk1 | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No pretreatment | Oestr | |||||

|

Live birth or ongoing pregnancy (Oestr + Ant vs Ant) |

299 per 1000 | 252 per 1000 (184 to 333) | OR 0.79 (0.53 to 1.17) | 502 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 | ‐ |

|

Live birth or ongoing pregnancy (Oestr + Ant vs Ag) |

350 per 1000 | 322 per 1000 (215 to 447) | OR 0.88 (0.51 to 1.5) | 242 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3,4 | ‐ |

|

Pregnancy loss (Oestr + Ant vs Ant) |

208 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (5 to 279) | OR 0.16 (0.02 to 1.47) | 49 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3,4 | ‐ |

|

Pregnancy loss (Oestr + Ant vs Ag) |

72 per 1000 | 110 per 1000 (46 to 240) | OR 1.59 (0.62 to 4.06) | 220 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3,4 | ‐ |

|

Multiple pregnancy rate (Oestr + Ant vs Ant) |

No data available | ‐ | ‐ | |||

|

Multiple pregnancy rate (Oestr + Ant vs Ag) |

Not calculable ‐ see comment | OR 2.24 (0.09 to 53.59) | 22 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3,4 | Only 2 events (both in oestrogen group) | |

|

OHSS rate (Oestr + Ant vs Ant) |

No data available | ‐ | ‐ | |||

|

OHSS rate (Oestr + Ant vs Ag) |

18 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (5 to 147) |

OR 1.54 (0.25 to 9.42) |

220 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3,4 | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Ag: agonist; Ant: antagonist; ART: assisted reproductive techniques; CI: confidence interval; Oestr: oestrogen; OHSS: ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; OR: odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Mean baseline risk of control group. 2 Downgraded one level for serious imprecision: effect estimate with wide confidence intervals. 3 Downgraded one level for serious risk of bias due to poor reporting on allocation concealment or high attrition (or both). 4 Downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision: small sample size and effect estimate with wide confidence intervals.

1. Combined oral contraceptive pill versus no pretreatment

Eight studies compared COCP versus no pretreatment (Cédrin‐Durnerin 2007; Garcia‐Velasco 2011; Huirne 2006c; Huirne 2006a; Kim 2011; Kolibianakis 2006; Nyboe Andersen 2011; Rombauts 2006).

Primary outcomes

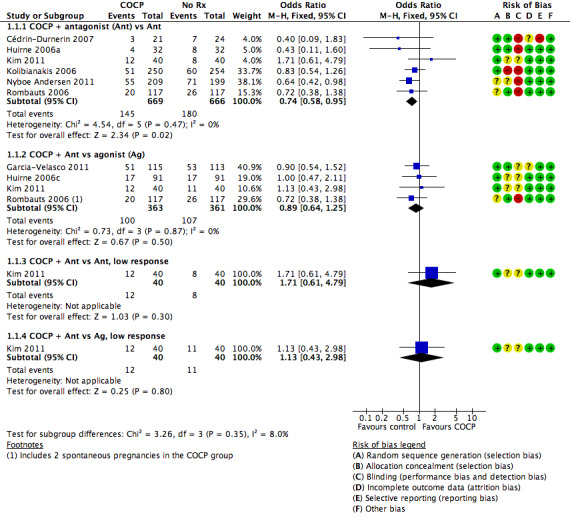

1.1. Live birth or ongoing pregnancy

See Figure 4 and Analysis 1.1.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Combined oral contraceptive pill (OCP) versus no pretreatment (Rx), outcome: 1.1 Live birth or ongoing pregnancy.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) versus no pretreatment (Rx), Outcome 1 Live birth or ongoing pregnancy.

1.1.1. Combined oral contraceptive pill plus antagonist versus antagonist

There was a lower rate of live birth or ongoing pregnancy in women pretreated with COCP compared with no pretreatment (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.95; 6 RCTs; 1335 women; I2 = 0%; moderate quality evidence). The evidence suggested that if the chance of a live birth or ongoing pregnancy following no pretreatment was assumed to be 27%, the chance following pretreatment with COCP would be between 18% and 26%.

1.1.2. Combined oral contraceptive pill plus antagonist versus agonist