Abstract

Background

Scalpels or electrosurgery can be used to make abdominal incisions. The potential benefits of electrosurgery may include reduced blood loss, dry and rapid separation of tissue, and reduced risk of cutting injury to surgeons. Postsurgery risks possibly associated with electrosurgery may include poor wound healing and complications such as surgical site infection.

Objectives

To assess the effects of electrosurgery compared with scalpel for major abdominal incisions.

Search methods

The first version of this review included studies published up to February 2012. In October 2016, for this first update, we searched the Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Ovid MEDLINE (including In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations), Ovid Embase, EBSCO CINAHL Plus, and the registry for ongoing trials (www.clinicaltrials.gov). We did not apply date or language restrictions.

Selection criteria

Studies considered in this analysis were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared electrosurgery to scalpel for creating abdominal incisions during major open abdominal surgery. Incisions could be any orientation (vertical, oblique, or transverse) and surgical setting (elective or emergency). Electrosurgical incisions were made through major layers of the abdominal wall, including subcutaneous tissue and the musculoaponeurosis (a sheet of connective tissue that attaches muscles), regardless of the technique used to incise the skin and peritoneum. Scalpel incisions were made through major layers of abdominal wall including skin, subcutaneous tissue, and musculoaponeurosis, regardless of the technique used to incise the abdominal peritoneum. Primary outcomes analysed were wound infection, time to wound healing, and wound dehiscence. Secondary outcomes were postoperative pain, wound incision time, wound‐related blood loss, and adhesion or scar formation.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently carried out study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment. When necessary, we contacted trial authors for missing data. We calculated risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous data, and mean differences (MD) and 95% CI for continuous data.

Main results

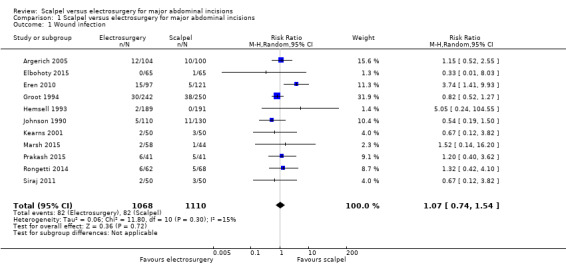

The updated search found seven additional RCTs making a total of 16 included studies (2769 participants). All studies compared electrosurgery to scalpel and were considered in one comparison. Eleven studies, analysing 2178 participants, reported on wound infection. There was no clear difference in wound infections between electrosurgery and scalpel (7.7% for electrosurgery versus 7.4% for scalpel; RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.54; low‐certainty evidence downgraded for risk of bias and serious imprecision). None of the included studies reported time to wound healing.

It is uncertain whether electrosurgery decreases wound dehiscence compared to scalpel (2.7% for electrosurgery versus 2.4% for scalpel; RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.58 to 2.50; 1064 participants; 6 studies; very low‐certainty evidence downgraded for risk of bias and very serious imprecision).

There was no clinically important difference in incision time between electrosurgery and scalpel (MD ‐45.74 seconds, 95% CI ‐88.41 to ‐3.07; 325 participants; 4 studies; moderate‐certainty evidence downgraded for serious imprecision). There was no clear difference in incision time per wound area between electrosurgery and scalpel (MD ‐0.58 seconds/cm2, 95% CI ‐1.26 to 0.09; 282 participants; 3 studies; low‐certainty evidence downgraded for very serious imprecision).

There was no clinically important difference in mean blood loss between electrosurgery and scalpel (MD ‐20.10 mL, 95% CI ‐28.16 to ‐12.05; 241 participants; 3 studies; moderate‐certainty evidence downgraded for serious imprecision). Two studies reported on mean wound‐related blood loss per wound area; however, we were unable to pool the studies due to considerable heterogeneity. It was uncertain whether electrosurgery decreased wound‐related blood loss per wound area. We could not reach a conclusion on the effects of the two interventions on pain and appearance of scars for various reasons such as small number of studies, insufficient data, the presence of conflicting data, and different measurement methods.

Authors' conclusions

The certainty of evidence was moderate to very low due to risk of bias and imprecise results. Low‐certainty evidence shows no clear difference in wound infection between the scalpel and electrosurgery. There is a need for more research to determine the relative effectiveness of scalpel compared with electrosurgery for major abdominal incisions.

Plain language summary

Scalpel versus electrosurgery for surgical operations on the abdomen

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about the effect of using either a scalpel (knife) or electrosurgery in surgical operations on the abdomen.

Background

During abdominal surgery, surgeons need to cut through several layers of abdominal wall tissue before reaching the target operation site. To do this, surgeons can use either a sharp‐bladed scalpel or an electrosurgical device that burns through tissue using a precise high‐frequency current (known as electrosurgery). It is thought that, compared to using a scalpel, electrosurgery may result in less blood loss, more rapid tissue separation, and a lower risk of surgeons cutting themselves. We wanted to find out about the benefits and risks of these two techniques, and to compare them in terms of safety and other measures such as risk of infection and pain.

Study characteristics

In October 2016, we searched for randomised controlled trials (RCTs; clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) comparing scalpel‐based surgery with electrosurgery for abdominal incisions (cuts). We found seven new trials for this update, allowing us to include a total of 16 RCTs involving 2769 participants. The majority of participants were adults, although one trial included children over the age of 15 years. There were slightly more female participants than male as some trials looked exclusively at caesarean sections (an operation to deliver a baby through a cut made in the abdomen and womb) and gynaecological (female reproductive system) surgery.

Key results

There was no clear difference between scalpel and electrosurgery in the number of people whose wounds became infected. It is uncertain whether electrosurgery prevents wound breakdown (a complication that involves the breaking open of the surgical incision along the stitches/staples) following surgery, while the difference in blood loss and time required for incision between electrosurgery and scalpel was not clinically important. There was not enough information available to determine how electrosurgery compared with scalpel‐based surgery in relation to time required for wounds to heal, amount of pain during healing, and appearance of scars. More studies need to be conducted before conclusions can be drawn as to whether one method is better for pain after an operation and time to wound healing following abdominal surgery.

Quality of the evidence

We judged the certainty of evidence to be moderate to very low for all outcomes. This is because the studies were often small with a low number of events and, in many cases, were not reported in a way that meant we could be sure they had been conducted robustly. The certainty of the evidence means that we cannot make conclusive statements and better quality research is needed to form stronger conclusions.

This plain language summary is up to date as of October 2016.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Scalpel versus electrosurgery for major abdominal incisions.

| Scalpel versus electrosurgery for major abdominal incisions | ||||||

|

Participant or population: people undergoing surgery involving major abdominal incisions Setting: university hospital, general hospital, and cancer hospital Intervention: electrosurgery Comparison: scalpel | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with scalpel | Risk with electrosurgery | |||||

| Wound infection | 79 per 1000 (55 to 114) | 74 per 1000 | RR 1.07 (0.74 to 1.54) | 2178 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | No clear difference in risk of wound infection between groups. The 95% CI crossed the line of no effect spanning estimates consistent with possible benefit and possible harm. |

| Time to wound healing (days) | Not reported | |||||

| Wound dehiscence | 27 per 1000 (14 to 55) | 24 per 1000 | RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.58 to 2.50 | 1064 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low2 | Uncertain whether electrosurgery decreased wound dehiscence between wounds compared with scalpel. The 95% CI crossed the line of no effect spanning estimates consistent with possible benefit and possible harm. |

| Postoperative pain | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 949 (9 RCTs) | ‐ | Postoperative pain reported as pain score (mostly assessed using VAS) in 9 RCTs, based on the need for analgesia in 6 RCTs and PEFR in 2 RCTs. Data pooling not feasible, therefore, no further analysis carried out. Therefore, insufficient evidence to determine the effect of scalpel and electrosurgery on postoperative pain. |

| Wound incision time (seconds) | The mean wound incision time ranged from 126 seconds to 540 seconds | The mean wound incision time in the electrosurgery group was 45.74 seconds fewer (88.41 fewer to 3.07 fewer) | ‐ | 325 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 | 3 RCTs (282 participants) reported wound incision time per wound area. The mean wound incision time per wound area in the electrosurgery group was 0.58 seconds/cm2 less (1.26 less to 0.09 more) and the quality of evidence was low. No clinically important difference in wound incision time between electrosurgery and scalpel. |

| Wound‐related blood loss (mL) | The mean wound‐related blood loss ranged from 23.4 mL to 105.5 mL | The mean wound‐related blood loss in the electrosurgery group was 20.10 mL less (28.16 less to 12.05 less) | ‐ | 241 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate4 | 2 RCTs (182 participants) reported wound‐related blood loss. Due to considerable heterogeneity, we were unable to pool the studies and quality of evidence for the outcome in both studies was low. No clinically important difference in wound‐related blood loss between electrosurgery and scalpel. |

| Adhesion or scar formation | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 84 (1 RCT) | ‐ | 1 RCT reported scar formation; however, no further analysis was carried out. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; PEFR: peak expiratory flow rate; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; VAS: visual analogue scale. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels: serious limitation due to lack of information on randomisation and allocation concealment in three studies contributing more than 50% to the analysis; serious imprecision as 95% CIs around the estimate were wide ranging including the probability of a reduction as well as an increase in wound infection.

2 Downgraded three levels: serious limitation due to attrition in one of two studies contributing more than 50% to the analysis; very serious due to inadequate number of events and imprecision as 95% CIs around the estimate are wide ranging including the probability of a reduction as well as an increase in wound infection.

3 Downgraded one level: serious imprecision as studies were small with inadequate sample size.

4 Downgraded one level: serious imprecision as studies were few with small sample size.

Background

This review is an update of a previously published version in the Cochrane Library (2012, Issue 6) on 'Scalpel versus electrosurgery for abdominal incisions'.

Description of the condition

Millions of surgical procedures on the abdomen are conducted around the world each year. Most of these are considered 'major abdominal surgery', which require an incision to be made through abdominal wall layers including the skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia (aponeurosis), muscle, and peritoneum to reach the abdominal cavity. Conventionally, scalpels have been used to make such surgical incisions by manually cutting through tissue using a sharp blade. However, since its introduction in the early part of the 20th century, electrosurgery has been used as an alternative tool for creating incisions (Anderson 2015). When creating a wound, key aims are to have a precise incision while minimising blood loss and the risk of surgical site infection (SSI). Based on the nature of the underlying conditions requiring surgery and degree of contamination, operative wounds are classified, with a progressive increase in risk of wound infection, into clean (class I), clean‐contaminated (class II), contaminated (class III), and dirty or infected (class IV).

Description of the intervention

Electrosurgery involves manipulation of electrons through living tissue using an alternating current density sufficient to create heat within tissue cells to destroy them (Soderstrom 2003). Two different surgical effects can be achieved with electrosurgery, namely cutting (of tissue) and coagulating. In the cutting mode, a continuous current rapidly produces extreme heat causing intracellular water to boil and cells to explode into steam (vaporisation). By moving the electrode quickly, more cells vaporise and the tissue is divided with minimal devitalised or charred tissue left along the margin of the cut surface. Thermal damage is minimal since heat evaporates as steam and is not conducted through the cut tissues, which would dry out the adjacent cells. In the coagulating mode, short bursts of electrical current are applied with a pause between each burst. As a result, the heat produced in the cells dries up the tissue but is not intense enough to evaporate intracellular water. The coagulating mode results in a greater degree of thermal damage and necrosis of adjacent tissues (Soderstrom 2003). Generally, if a surgeon chooses to make an incision using electrosurgery, it is recommended that the cutting mode is selected with a small tip or needle electrode that is activated just prior to making contact with the target tissue (Soderstrom 2003). However, many surgeons avoid using electrosurgery to divide the skin because of the concern of excessive scarring. More recently, a newer type of electrosurgery has been introduced which uses pulsed radiofrequency to produce a plasma‐mediated discharge along the exposed rim of an insulated blade. This mechanism results in effective cutting with a blade, which remains near body temperature. Studies comparing the radiofrequency approach with conventional electrosurgery and scalpels for creating incisions in animal models have reported favourably for the radiofrequency approach in terms of wound tensile strength, scar formation, and minimising blood loss and tissue damage (Loh 2009; Chang 2011).

How the intervention might work

The potential benefits of electrosurgery have been suggested to include reduced blood loss, dry and rapid separation of the tissue, and a possible decrease in the risk of accidental injury caused by the scalpel blade to operative personnel (Soderstrom 2003). However, there are concerns about the impact of electrosurgery on wound infection, wound healing, scarring, and adhesion formation, which have limited the use of electrosurgery for surgical wound creation. Data from animal studies have consistently shown that wounds created by electrosurgery (especially using the coagulation current) have more extensive tissue necrosis and inflammatory response, and a significant reduction in tensile strength during healing (Rappaport 1990). In addition, the use of electrosurgery may be associated with increased adhesion formation (i.e. scar formation between two smooth gliding surfaces) between the incision and abdominal viscera due to an out‐flowing of blood and formation of fibrin clots in the more traumatised animal tissue (Kumagai 1991; Madden 1970; Rappaport 1990). In rat and guinea pig models, necrotic tissue is an important contributory factor to the increased susceptibility of electrosurgical incisions to infection, particularly in contaminated wounds (Keenan 1984; Kumagai 1991; Madden 1970). Additionally, the use of electrosurgery has been related to an increase in the incidence of bacteraemia and death (Kumagai 1991). However, more recently, these concerns have been lowered with new‐generation electrosurgical instruments.

However, unlike animal studies which are executed under controlled conditions, there are many biological and environmental contributing factors that could affect outcomes from the use of electrosurgery in the clinical setting, although data are limited. One 10‐year prospective observational study of 62,939 surgical wounds suggested that the risk of infection for wounds resulting from clean surgery (i.e. non‐infective operative wounds with no inflammation, and none of the respiratory, alimentary, genitourinary tract, or the oropharyngeal cavity is entered) was similar for people with electrosurgery‐ and scalpel‐generated surgical incisions (Cruse 1980), although the results to support this conclusion were not presented.

Why it is important to do this review

Several prospective randomised trials have examined the effects of scalpel versus electrosurgery for wound creation on the abdomen, which have necessitated an update of the original version of this Cochrane Review which was published in 2012 (Charoenkwan 2012). We aimed to identify and assess relevant studies systematically to present a comprehensive summary of current evidence regarding the relative effectiveness of electrosurgery for making surgical incisions compared with scalpels. Importantly, this synthesis also involves assessment of evidence quality using the GRADE process (GRADE 2013). Such an evidence synthesis is important in contributing to informed decision‐making around the use of electrosurgery in practice. Current National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the prevention of SSI do not recommend the use of electrosurgery; however, the recommendation was based on data available approximately 10 years ago (NICE 2008).

Objectives

To assess the effects of electrosurgery compared with scalpel for major abdominal incisions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

This review included randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We excluded quasi‐randomised controlled studies.

Types of participants

People undergoing major open abdominal surgery for any reason, regardless of the orientation of the incision (vertical, oblique, or transverse) and surgical setting (elective or emergency). 'Major open abdominal surgery' is defined as any abdominal surgical procedures that require an incision to be made through abdominal wall layers including the skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia, muscle, and peritoneum to reach the abdominal cavity. For herniorrhaphy (surgical repair of a hernia; see Appendix 1 for glossary of terms), we considered wound creation to be complete if the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and external/internal oblique aponeurosis had been divided.

Types of interventions

Main intervention: wound creation using electrosurgery

The use of electrosurgery to incise major layers of abdominal wall including subcutaneous tissue and musculoaponeurosis (see Appendix 1 for glossary of terms), regardless of the techniques used to incise the abdominal skin and peritoneum.

Comparison intervention: wound creation using a scalpel

The use of a scalpel to incise all major layers of abdominal wall including skin, subcutaneous tissue, and musculoaponeurosis, regardless of the techniques used to incise the abdominal skin and peritoneum.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Wound infection.

Time to wound healing.

Wound dehiscence.

Secondary outcomes

Postoperative pain.

Wound incision time.

Wound‐related blood loss.

Adhesion or scar formation.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

In October 2016, we updated the searches of the following electronic databases to find reports of relevant RCTs:

Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register (searched 10 October 2016);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library 2016, Issue 9) (searched 10 October 2016);

Ovid MEDLINE including In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (1946 to 10 October 2016);

Ovid Embase (1974 to 10 October 2016);

EBSCO CINAHL Plus (searched 10 October 2016).

The search strategies for the Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register, CENTRAL, Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase and EBSCO CINAHL Plus can be found in Appendix 2. We combined the Ovid MEDLINE search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximising version (2008 revision) (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the Embase search with the Ovid Embase filter developed by the UK Cochrane Centre (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the CINAHL Plus searches with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN 2015). Details of the search strategies used for the previous version of the review are given in Charoenkwan 2012. We also searched the following trials registries:

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov); a service of the US National Institutes of Health (searched 28 June 2016)

Searching other resources

We searched the citation lists of relevant publications, systematic reviews, review articles, and included studies. We contacted experts, specialists in the field, and the authors of relevant publications for information about possible unpublished studies. For publications in non‐English languages, we obtained a translation of the methods and results if the content of the abstract was thought to be relevant.

Data collection and analysis

We carried out data collection and analysis according to methods stated in the published protocol (Charoenkwan 2006), which were based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Selection of studies

Any two of three review authors (KC, KR, and ZIE) independently undertook study selection and screened the titles and abstracts of articles found in the search while the third review author arbitrated if there were disagreements. We discarded studies that were clearly ineligible. One review author (KC) obtained copies of the full‐text articles that appeared to be eligible. Both review authors independently assessed whether the studies met the inclusion criteria and resolved discrepancies by discussion. We contacted authors for additional information to enable decisions regarding eligibility. Excluded studies are described in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

We extracted and summarised details of the included studies on the data extraction form. One review author (ZIE) extracted data and a second review author (KC) checked these for accuracy. We attempted to contact trial authors to obtain missing information where necessary.

We extracted the following data:

names of study authors;

year of publication;

country where study was performed;

study design;

method of randomisation;

unit of randomisation;

overall sample size and methods used to estimate statistical power;

outcome measures;

setting of operation;

participant selection criteria;

details of interventions for each study group;

number of participants in each study group;

baseline characteristics of participants in each study group;

statistical methods used for data analysis;

number of and reason for withdrawal in each study group;

outcomes

type of wound (clean, clean‐contaminated, contaminated or dirty).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Methodological quality of the included trials was assessed using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). The tool addresses six specific domains of potential bias: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and 'other issues'. Studies were judged to be at high, low, or unclear risk of bias for each of the domains. The methodological quality assessment is presented in the 'Risk of bias' section of the Characteristics of included studies table and summarised graphically.

Measures of treatment effect

We displayed dichotomous data for each study as a risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous data, we expressed results from each study as a mean difference (MD) with a 95% CI. We planned to express time‐to‐event data (e.g. time‐to‐complete wound healing) as hazard ratios (HR) (with their 95% CI), in accordance with the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011). In future updates, if such studies do not report an HR, we plan to estimate this using other reported data, such as the numbers of events, with application of available statistical methods (Parmar 1998; Tierney 2007; Wang 2013). In the absence of these measures, if there are any studies in which all wounds healed, we will consider the mean or median time to healing without survival analysis as a valid outcome (i.e. if the trial authors regarded time to healing as a continuous measure because there was no censoring). In this review, we were unable to report time to wound healing as none of the studies met these criteria.

Unit of analysis issues

Studies included in the primary analysis consisted of simple parallel‐group designs where participants were individually randomised to one of two intervention groups, and a single measurement from each participant collected and analysed. Split body studies and studies where the unit of analysis was the wound would have been analysed with parallel group studies or alone had sufficient data been reported.

Dealing with missing data

We analysed the data on an intention‐to‐treat basis. We contacted investigators from the original trials to request missing data. Where we were unable to obtain missing data from trial authors, we outlined results in additional tables and reported them as a narrative summary.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Assessment of heterogeneity comprised the initial assessment of clinical and methodological heterogeneity and the appropriateness of combining study results: that is, the degree to which the included studies varied in terms of participant, intervention, outcome, and characteristics such as length of follow‐up. This assessment of clinical and methodological heterogeneity was supplemented by information regarding statistical heterogeneity of the results. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by visual inspection of the overlap of CIs on the forest plots alongside Chi2 tests and quantified using the I2 statistic. I2 statistic thresholds were interpreted according to Higgins 2011 as follows: 0% to 40% (may not be important), 30% to 60% (moderate heterogeneity), 50% to 90% (substantial heterogeneity), and 75% to 100% (considerable heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Most reporting biases were avoided by conducting a broad literature search and adding search filters on year of publication or language. For studies where the protocols were published at www.clinicaltrials.gov, we examined consistency between planned and the reported outcomes. We used a funnel plot to assess publication bias.

Data synthesis

We performed statistical analyses in accordance with Cochrane guidelines using Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014). For dichotomous data (e.g. proportion of wounds developing infection), we expressed results for each study as RR with a 95% CI. For continuous data, we expressed results from each study as MD with 95% CI, and combined for meta‐analysis where appropriate. Since meta‐analytic methods for continuous data assume that the underlying distribution of the measurements is normal, in instances where data were clearly skewed, and the results were reported in the publication as 'median' and 'range' with non‐parametric tests of significance, we reported the results in narrative form. For a study which included participants undergoing thoracic surgery as well as those undergoing abdominal surgery, all participants were included in the analysis. For a study which included two clinically different abdominal procedures, the dichotomous data were included in meta‐analyses as a single study, while continuous data were treated and included in meta‐analyses as data from two separate studies. In terms of meta‐analytical approach, when meta‐analysis was considered viable in the presence of clinical heterogeneity (review author judgement) or there was evidence of statistical heterogeneity, or both, we used a random‐effects model. We considered a fixed‐effect approach only when clinical heterogeneity was thought to be minimal and statistical heterogeneity was estimated as non‐statistically significant for the Chi2 value and 0% for the I2 assessment (Kontopantelis 2013). This approach recognises that statistical assessments can miss potentially important between‐study heterogeneity in small samples hence the preference for the more conservative random‐effects model (Kontopantelis 2013). We decided against pooling studies with considerable heterogeneity (75% or more).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform subgroup analysis based on cutting versus coagulating modes of electrical current used in the electrosurgery group since different mechanisms of tissue separation may have impact on outcomes. However, this was not possible as the interventions were not sufficiently homogenous nor well reported to carry out this analysis. To evaluate the effect of wound contamination on the outcomes, we carried out a post hoc analysis on (class I vs. class II vs. class III vs. class IV wounds).

Sensitivity analysis

We intended to perform a sensitivity analysis to assess whether the findings of the review were robust to the decisions made during the review process. We would have excluded studies at high or unclear risk of bias from the analyses to assess whether this affected the findings of the review. However, this was not possible as none of the included studies were at low risk of bias.

'Summary of findings' tables

Two review authors (ZIE and KC) assessed the certainty of the evidence generated from the review according to GRADE methodology (GRADE 2013). We presented the main results in a 'Summary of findings' table produced using GRADEpro software. The certainty of the evidence was initially considered to be high because of the study design (RCT). We subsequently downgraded this depending on whether there were study limitations (which we judged based on the risk of bias in studies which contributed at least 50% of the weight in the analysis), whether the results were inconsistent, imprecise, the evidence was indirect or there was publication bias. The 'Summary of findings' table presents the following outcomes:

wound infection

time to wound healing

wound dehiscence

postoperative pain

wound incision time

wound‐related blood loss

adhesion or scar formation.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

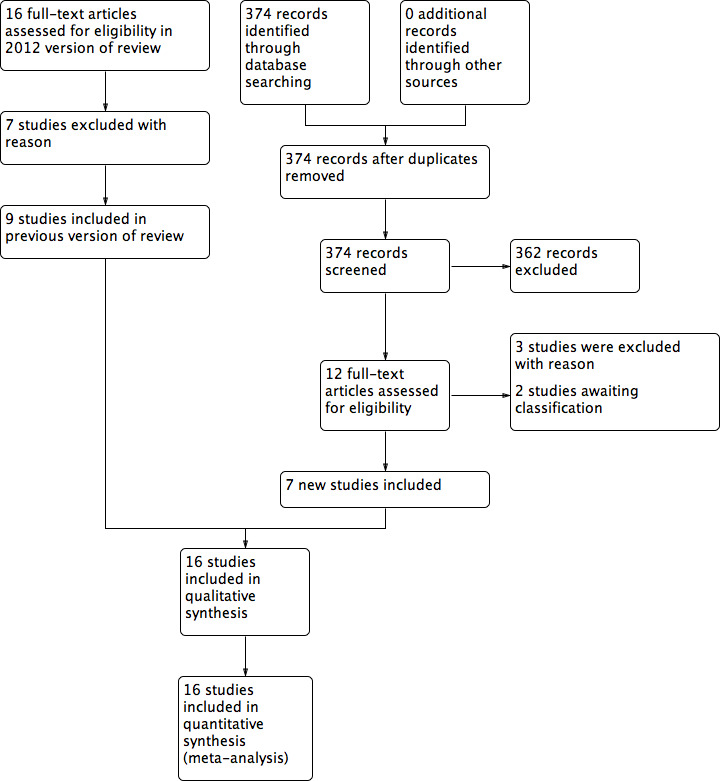

The summary of the search results is presented in a PRISMA study flow diagram (Figure 1). At the time of the original review, we included nine RCTs that met the inclusion criteria (Argerich 2005; Dixon 1990; Groot 1994; Hemsell 1993; Hussain 1988; Johnson 1990; Kearns 2001; Pearlman 1991; Telfer 1993), and excluded seven studies (Chrysos 2005; Duxbury 2003; Franchi 2001; Ji 2006; Keel 2002; Miller 1988; Porter 1998). For this updated review, we identified 12 additional potentially eligible studies (Aird 2015; Elbohoty 2015; Eren 2010; Husnain 2006; Marsh 2015; Prakash 2015; Rongetti 2014; Shamim 2009; Shivagouda 2010; Siraj 2011; Stupart 2016; Upadhyay 2013). Seven studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the updated analysis (Elbohoty 2015; Eren 2010; Marsh 2015; Prakash 2015; Rongetti 2014; Shivagouda 2010; Siraj 2011; Characteristics of included studies table). Three studies were excluded from the new search for failing to meet the inclusion criteria (Aird 2015; Shamim 2009; Stupart 2016; Characteristics of excluded studies table). Two studies are still awaiting further assessment (Husnain 2006; Upadhyay 2013; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table).

1.

Study flow diagram of review update.

Included studies

Participants

A total of 2769 people participated in the 16 included studies. The number of participants within each study ranged from 60 (Shivagouda 2010) to 492 (Groot 1994). All studies were conducted in a single hospital setting except for Pearlman 1991, which took place at two university‐affiliated institutions. The countries represented in these studies were the UK (Dixon 1990; Johnson 1990; Marsh 2015; Telfer 1993), Brazil (Argerich 2005; Rongetti 2014), India (Prakash 2015; Shivagouda 2010), USA (Hemsell 1993; Pearlman 1991), Canada (Groot 1994), Egypt (Elbohoty 2015), Ireland (Kearns 2001), Pakistan (Siraj 2011), Saudi Arabia (Hussain 1988), and Turkey (Eren 2010).

Surgical indications and incisions varied widely among studies. Four studies were conducted in participants receiving abdominal incisions for any indication (Argerich 2005; Johnson 1990; Kearns 2001; Telfer 1993). Siraj 2011 examined participants who underwent elective midline laparotomy. Eren 2010 included participants undergoing abdominal surgery for various gastrointestinal malignancies through midline laparotomy incisions. Prakash 2015 studied participants who had a midline abdominal incision for emergency (mostly for hollow viscus perforation) and elective (most commonly for stomach cancer) abdominal surgery. One study included participants having either abdominal or thoracic operations (Groot 1994). Two studies consisted of people undergoing cholecystectomy (surgical removal of the gall bladder) (Hussain 1988; Pearlman 1991). Dixon 1990 included participants undergoing either cholecystectomy or inguinal herniorrhaphy. Shivagouda 2010 included only participants receiving inguinal herniorrhaphy. Hemsell 1993 included participants scheduled for abdominal hysterectomy for benign diseases. Rongetti 2014 examined people who underwent elective abdominal gynaecological surgery via laparotomy for diagnosis and curative or palliative cancer treatment. Elbohoty 2015 examined women with a history of one previous caesarean section who underwent planned repeat caesarean section through an existing transverse abdominal incision. Marsh 2015 considered participants who had full abdominoplasty surgery.

Four studies reported the number of participants in different levels of wound classification (class I to IV) (Argerich 2005; Groot 1994; Johnson 1990; Rongetti 2014), and three studies specified the incidences of wound infection in each level for the two study groups (Argerich 2005; Groot 1994; Johnson 1990). Studies that did not specifically report wound classification were not taken into account regardless of the nature of the procedures in order to exclude the possibility of unexpected contamination leading to misclassification.

Interventions

Electrosurgery group

Ten studies set the electrosurgical instruments in cutting mode to incise the major layers of the abdominal wall including subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and fascia (Dixon 1990; Elbohoty 2015; Hussain 1988; Johnson 1990; Kearns 2001; Pearlman 1991; Prakash 2015; Shivagouda 2010; Siraj 2011; Telfer 1993). In Hemsell 1993, although subcutaneous tissues were opened using the pure cut mode, the fascia was incised with the scalpel in all participants regardless of allocation. Four studies used coagulating mode electrosurgery instead of the cutting mode (Argerich 2005; Eren 2010; Groot 1994; Marsh 2015). In Rongetti 2014, while the subcutaneous tissue was opened to the aponeurosis with electrocoagulation, the aponeurosis and peritoneum were incised using the 'cut' mode electrosurgery.

Nine studies incised the skin by scalpel (Argerich 2005; Dixon 1990; Elbohoty 2015; Groot 1994; Hemsell 1993; Hussain 1988; Pearlman 1991; Rongetti 2014; Telfer 1993), and six studies by cutting‐mode electrosurgery (Eren 2010; Johnson 1990; Kearns 2001; Prakash 2015; Shivagouda 2010; Siraj 2011). One study did not specify the instrument used for making skin incision (Marsh 2015).

Scalpel group

For the scalpel group, a scalpel was used to create an incision through all layers in all except for two studies (Johnson 1990; Rongetti 2014). In Johnson 1990, some of the participants who required muscle cutting incision had their muscle cut using electrosurgery. In Rongetti 2014, the skin and subcutaneous tissue were divided by using scalpel to the aponeurosis. However, the aponeurosis and peritoneum were incised using the electrosurgery in 'cut' mode.

Although the technique of haemostasis and wound closure varied among studies, the same technique was used for both study groups in all trials except Elbohoty 2015 and Pearlman 1991. In those two trials, bleeding points were controlled with electrosurgery in the electrosurgery group and with ligature in the scalpel group.

Outcomes

Eleven trials reported wound infection (Argerich 2005; Elbohoty 2015; Eren 2010; Groot 1994; Hemsell 1993; Johnson 1990; Kearns 2001; Marsh 2015; Prakash 2015; Rongetti 2014; Siraj 2011). Six trials reported wound dehiscence (Dixon 1990; Elbohoty 2015; Hemsell 1993; Johnson 1990; Kearns 2001; Rongetti 2014) (see Appendix 1 for glossary of terms). The frequency of wound dehiscence reported in this review represented both total dehiscence (deep; all layers including fascia) and partial dehiscence (superficial; subcutaneous tissue only).

Seven studies reported the time taken to make the wound incision (Dixon 1990; Elbohoty 2015; Johnson 1990; Kearns 2001; Pearlman 1991; Prakash 2015; Telfer 1993). Four trials reported wound incision time as means (Dixon 1990; Kearns 2001; Pearlman 1991; Prakash 2015), and three trials as medians (Elbohoty 2015; Johnson 1990; Telfer 1993). Three trials reported mean wound incision time per wound area (seconds/cm2) (Kearns 2001; Prakash 2015; Siraj 2011).

Six studies reported wound‐related blood loss (Kearns 2001; Pearlman 1991; Prakash 2015 as means; Elbohoty 2015; Telfer 1993 as medians; Prakash 2015; Siraj 2011 as mean wound‐related blood loss per wound area). Regarding measurement of wound‐related blood loss, Elbohoty 2015, Kearns 2001, and Siraj 2011 weighed swabs used exclusively without using suction while making the incision. In Pearlman 1991, once the peritoneum was reached, the anaesthesiologist recorded incision blood loss. Telfer 1993 measured blood loss by weighing swabs using a standardised technique.

Eight studies assessed postoperative pain at different time intervals and used a variety of methods (Dixon 1990; Hussain 1988; Kearns 2001; Pearlman 1991; Prakash 2015; Shivagouda 2010; Siraj 2011; Telfer 1993). Apart from Dixon 1990, Hussain 1988, and Shivagouda 2010, all pain measurements were performed daily by using a visual analogue scale, with '0' denoting no pain and '10' denoting the most extreme pain, for the first three to five days after surgery, and were reported either as means (Kearns 2001; Siraj 2011), medians (Prakash 2015; Telfer 1993), or a three‐day sum of the scores (Pearlman 1991). Telfer 1993 also assessed peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR). Dixon 1990 assessed pain score by using a Likert scale. Hussain 1988 used a visual analogue scale to assess pain every four hours during the first 24 hours after surgery, along with the measurement of PEFR and requirement of morphine. Shivagouda 2010 employed a visual analogue scale to evaluate pain at six, 12, and 24 hours after surgery and mean dosage of analgesic requirement.

Six studies recorded analgesia requirement (Elbohoty 2015; Hussain 1988; Kearns 2001; Pearlman 1991; Shivagouda 2010; Telfer 1993).

One study reported scar formation (Dixon 1990).

None of the included studies reported time to wound healing.

Excluded studies

We excluded three studies from this updated review (Aird 2015; Shamim 2009; Stupart 2016). In Aird 2015 and Stupart 2016, the inclusion criteria with regard to comparison intervention were not met. The subcutaneous and fascial layers in all participants assigned to the scalpel group were divided using electrosurgery. Shamim 2009 was a quasi‐randomised trial. Seven studies excluded in the previous review were non‐randomised (Chrysos 2005; Franchi 2001), did not involve abdominal wound creation (Duxbury 2003; Miller 1988; Porter 1998), and compared different scalpel interventions (Ji 2006; Keel 2002).

Risk of bias in included studies

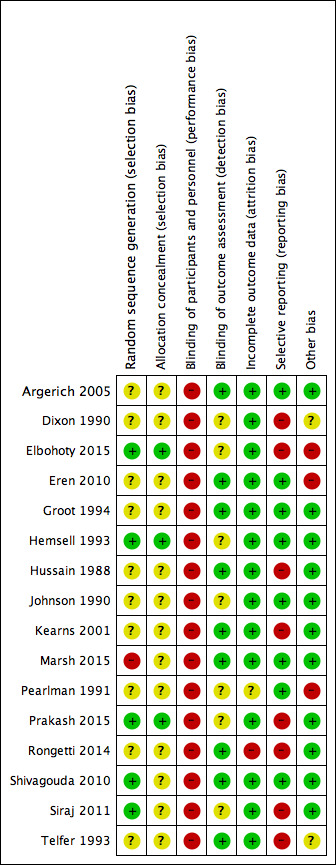

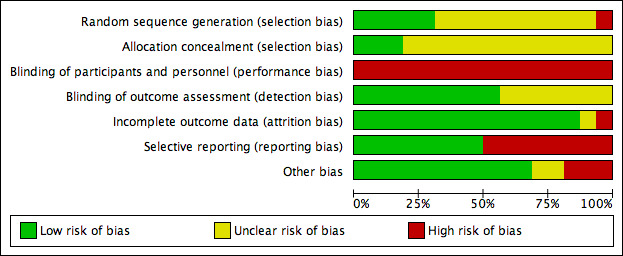

The methodological quality of the trials was assessed using the Cochrane tool and summarised in the Characteristics of included studies, the 'Risk of bias' summary (Figure 2), and the 'Risk of bias' graph (Figure 3). Incomplete reporting on various domains was evident across studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Sequence generation

Five trials reported the process of sequence generation and were at low risk of bias for this domain (Elbohoty 2015; Hemsell 1993; Prakash 2015; Shivagouda 2010; Siraj 2011). The process of sequence generation in Marsh 2015 appeared at high risk. Sequence generation was unclear for the remaining 10 studies.

Allocation concealment

Allocation concealment appeared to be unclear in all except three included studies (Elbohoty 2015; Hemsell 1993; Prakash 2015). Allocation was performed by using either opaque sealed assignment envelopes (Elbohoty 2015; Prakash 2015), or central telephone assignment according to a randomly generated number list (Hemsell 1993). In 13 studies at unclear risk of bias, there was insufficient information or it was unclear whether envelopes used were opaque and sealed.

Blinding

Nine studies clearly blinded outcome assessors to assigned interventions (Argerich 2005; Eren 2010; Groot 1994; Hussain 1988; Kearns 2001; Marsh 2015; Rongetti 2014; Shivagouda 2010; Telfer 1993). Dixon 1990 reported blinding of the outcome assessors, but only for evaluating wound cosmetic appearance; therefore blinding was unclear for the other outcomes. The five remaining studies had unclear risk of blinding outcome assessors.

Due to the nature of the intervention, the review authors decided to mark all the studies high risk for performance bias since blinding of surgeons was impossible. However, blind outcome assessment is considered more important than blinding of participants and carers (Hróbjartsson 2012).

Incomplete outcome data

Across studies, participant completion was 100% or the reason for dropping out and proportion of dropouts was balanced across study groups with two exceptions (Pearlman 1991; Rongetti 2014). Pearlman 1991 excluded 10/100 participants after randomisation due to unplanned common bile duct exploration. It was at unclear risk of attrition bias as there was no information regarding which groups the excluded participants belonged to. Rongetti 2014 had high risk of attrition bias as it had 19% attrition mainly due to "digestive tract mucosa exposure." This happened more in the scalpel group compared to the electrosurgery group (15 for scalpel versus 3 for electrosurgery).

Selective reporting

Trial registrations were not available for most of the studies; however, there was no evidence to suggest selective reporting of outcomes in eight included trials. Seven studies did not report measures of variance for continuous outcomes (Dixon 1990; Elbohoty 2015; Hussain 1988; Kearns 2001; Prakash 2015; Siraj 2011; Telfer 1993). Rongetti 2014 reported means, did not report standard deviations, and did not report most outcomes according to study groups. These eight studies were at high risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

In all studies except five (Dixon 1990; Elbohoty 2015; Eren 2010; Pearlman 1991; Telfer 1993), baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were comparable between the two study groups in each trial and no other biases were apparent. There was an imbalance in sex ratio in Telfer 1993 and baseline characteristics were not compared in Dixon 1990. Given that the method of randomisation was not clearly stated, the two studies were marked unclear as any imbalance in baseline characteristics could introduce further bias to the results. Eren 2010 reported an imbalance in number of participants assigned to the study groups and given that there was no information regarding the method of randomisation, this was considered a source of bias. The study groups varied in the way bleeding points were controlled in Elbohoty 2015 and Pearlman 1991.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Sixteen studies (2769 participants) compared scalpel versus electrosurgery (Table 1).

Primary outcomes

Wound infection

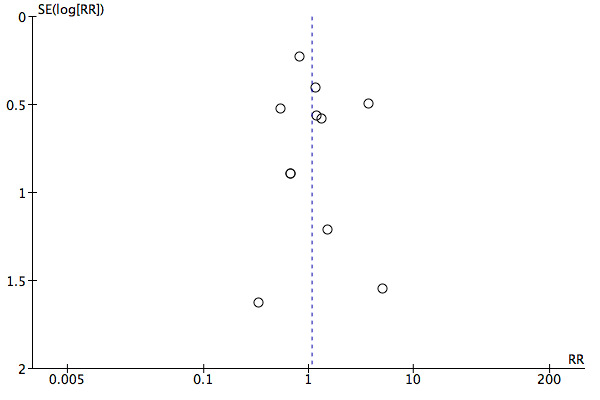

Eleven studies, analysing 2178 participants, reported on wound infection events. There was no clear difference in wound infections between electrosurgery and scalpel (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.54; I2 = 15%; Analysis 1.1). The evidence was of low certainty and was downgraded twice, once for serious risk of bias and once for imprecision. The results were assessed for publication bias (Figure 4). We tested for funnel plot asymmetry and by visual inspection found no evidence of publication bias. Therefore, the evidence was not downgraded for this. We used a random‐effects model due to the presence of statistical heterogeneity.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Scalpel versus electrosurgery for major abdominal incisions, Outcome 1 Wound infection.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Scalpel versus electrosurgery for major abdominal incisions, outcome: 1.1 Wound infection.

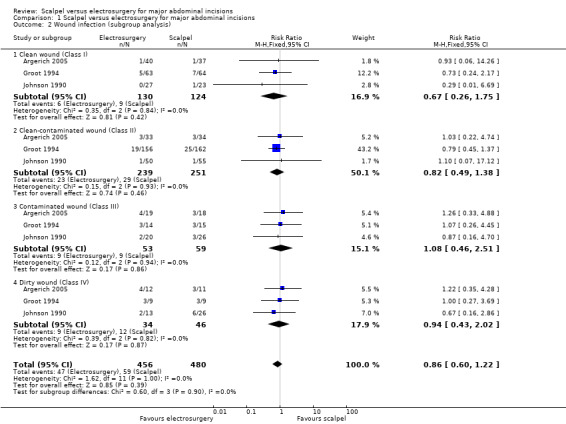

In a post hoc subgroup analysis, there were no significant difference in risk of wound infection between the scalpel group and the electrosurgery groups in all strata of wound classification based on degree of contamination (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Scalpel versus electrosurgery for major abdominal incisions, Outcome 2 Wound infection (subgroup analysis).

Time to wound healing

None of the included studies reported time to wound healing.

Wound dehiscence

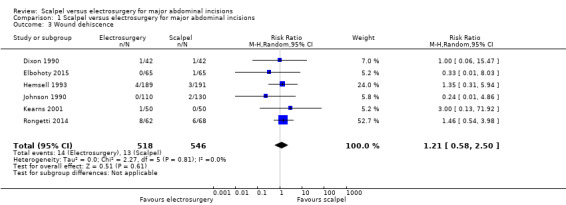

Six studies analysing 1064 participants reported on wound dehiscence. It was uncertain whether electrosurgery decreased the incidence of wound dehiscence compared to scalpel (RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.58 to 2.50; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.3). The certainty of the evidence was very low. It was downgraded once due to risk of bias and twice for very serious imprecision. Wound dehiscence is a relatively rare event and this meta‐analysis was underpowered to detect clinically important differences. In addition, the CIs included the possibility of both decreased and increased wound dehiscence. The fixed‐effect model was adopted as there was no statistical heterogeneity between the studies.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Scalpel versus electrosurgery for major abdominal incisions, Outcome 3 Wound dehiscence.

Secondary outcomes

Postoperative pain

Nine studies analysing 945 participants assessed postoperative pain at different time intervals (Dixon 1990; Elbohoty 2015; Hussain 1988; Kearns 2001; Pearlman 1991; Prakash 2015; Shivagouda 2010; Siraj 2011; Telfer 1993). The studies provided data on postoperative pain score, peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) and need for postoperative analgesia.

Given that we were unable to pool the data, we have presented the pain data in additional tables (Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5). Inconsistency in reporting, substantial heterogeneity, and failure to report measures of variance precluded the inclusion of these data in a meta‐analysis. The results were mixed with postoperative pain appearing to be reduced in the electrosurgery group in most of the studies. Pain also appeared to be similar across the study groups in some studies. As no further analyses were carried out, we are unable to draw any substantive conclusion from available data.

1. Postoperative pain: pain scores.

| Study (details) | Time postoperation | ||||||||

| 4 h | 8 h | 12 h | 16 h | 1 d | 2 d | 3 d | 4 d | 5 d | |

| Dixon 1990 (n = 60; absent = 0; mild = 1; moderate = 2; severe = 3) | |||||||||

| Scalpel | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 20 | 8 | 2 | 0 |

| Electrosurgery | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 17 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Hussain 1988(n = 200; mean (range)) | |||||||||

| Scalpel | 5.75 (2.7 to 8.5) | 8.85 (6 to 10) | 6.75 (1 to 8.3) | 6.75 (1 to 8.3) | 6.75 (0.7 to 8.3) | ||||

| Electrosurgery | 3.85 (1 to 6) | 5.92 (2.3 to 9.6) | 4.36 (0.7 to 7.5) | 3 (1 to 5) | 4.35 (0.7 to 7.7) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kearns 2001(n = 100; mean (SEM)) | |||||||||

| Scalpel | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 2.7 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | 1.9 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.1) |

| Electrosurgery | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 2.3 (not reported) | 2 (0.1) | 1.6 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) |

| Pearlman 1991(n = 59; objective scale; mean (SD)) | |||||||||

| Scalpel | d 1 + d 2 + d 3 = 9 (4) | ||||||||

| Electrosurgery | d 1 + d 2 + d 3 = 8 (3) | ||||||||

| Study (details) | 6 h | 8 h | 12 h | 16 h | 1 d | 2 d | 3 d | 4 d | 5 d |

| Prakash 2015 (n = 82; median (interquartile range)) | |||||||||

| Scalpel | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 5 (0 to 8) | 4 (0 to 8) | 4 (0 to 6) | 3 (0 to 5) | 2 (0 to 5) |

| Electrosurgery | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 5 (0 to 10) | 4 (0 to 8) | 3 (0 to 8) | 2 (0 to 7) | 2 (0 to 5) |

| Shivagouda 2010(n = 60; mean (SD)) | |||||||||

| Scalpel | 6.7 (0.53) | ‐ | 3.7 (0.64) | ‐ | 2.4 (0.51) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Electrosurgery | 6.6 (0.81) | ‐ | 3.8 (0.83) | ‐ | 2.5 (0.86) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Siraj 2011(n = 100; mean): | |||||||||

| Scalpel | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 3.96 | 3 | 2.4 | 2.08 | 1.58 |

| Electrosurgery | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 3.78 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 1.94 | 1.4 |

| Telfer 1993(n = 101; median (interquartile range)) | |||||||||

| Scalpel | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 6 (4 to 8) | 5 (3.5 to 6) | 5 (4 to 6) | 4 (2 to 5) | ‐ |

| Electrosurgery | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 6 (5 to 7) | 5 (3.75 to 7) | 5 (3 to 6) | 4 (3 to 5) | ‐ |

d: day; h: hour; n: number of participants; SD: standard deviation; SEM: standard error of the mean.

2. Postoperative pain (scalpel vs electrosurgery): visual analogue scale (reported P values).

| Study (details) | Time postoperation | ||||||||

| 4 h | 8 h | 12 h | 16 h | 1 d | 2 d | 3 d | 4 d | 5 d | |

| Dixon 1990 (n = 60) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | NS | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hussain 1988 (n = 200) | < 0.02 | < 0.01 | < 0.02 | < 0.01 | < 0.02 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kearns 2001 (n = 100) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.34 | 0.43 |

| Pearlman 1991 (n = 59) | d 1 + d 2 + d 3 = NS | ||||||||

| Study (details) | 6 h | 8 h | 12 h | 16 h | 1 d | 2 d | 3 d | 4 d | 5 d |

| Shivagouda 2010 (n = 60) | 0.475 | ‐ | 0.556 | ‐ | 0.762 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Siraj 2011 (n = 100) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 0.24 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.33 | 0.13 |

| Telfer 1993 (n = 101) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | NS | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

d: day; h: hour; n: number of participants; NS: not significant (as reported by study authors).

3. Postoperative pain: need for analgesia.

| Study (details) | Scalpel | Electrosurgery | P value |

| Hussain 1988(n = 200; mean (range)) | |||

| Frequency of morphine injection per 24 h | 5 (3 to 6) | 3 (2 to 5) | < 0.05 |

| Milligrams of morphine per 24 h (mg) | 52 (30 to 60) | 30 (20 to 52) | < 0.05 |

| Kearns 2001(n = 100; mean (SEM)) | |||

| Morphine (mL) | 92 (9.1) | 66 (7.6) | 0.036 |

| Days morphine required | 2.6 (0.1) | 2.2 (0.1) | 0.011 |

| Pearlman 1991(n = 59; mean (SD)) | |||

| Narcotic injections for first 3 days | 9 (4) | 8 (3) | NS |

| Elbohoty 2015 (n = 130; median (range)) | |||

| Doses of paracetamol | 4 (4 to 4) | 3 (2 to 4) | < 0.001 |

| Shivagouda 2010(n = 60; mean (SD)) | |||

| Doses of analgesic | 1.6 (0.48) | 1.8 (0.66) | 0.499 |

| Telfer 1993(n = 101; median) | |||

| Total Morphine use (mg/kg) | 1.55 | 1.49 | NS |

h: hour; n: number of participants; NS: not significant (as reported by study authors); SD: standard deviation; SEM: standard error of mean.

4. Postoperative pain: peak expiratory flow rate.

| Study (details) | 18 h | P value | 24 h | P value | ‐ |

| Hussain 1988(n = 200; mean (range)) | |||||

| Scalpel | 1.52 (1.35 to 1.75) | NS | 1.6 (1.32 to 1.88) | < 0.05 | ‐ |

| Electrosurgery | 1.64 (1.42 to 1.85) | 2.1 (1.6 to 2.2) | |||

| Study (details) | 1 d | 2 d | 3 d | 4 d | P value |

| Telfer 1993(n = 101; median (interquartile range)) | |||||

| Scalpel | 217 (180 to 265) | 220 (190 to 280) | 260 (210 to 320) | 282 (230 to 357) | NS |

| Electrosurgery | 218 (160 to 272) | 237 (182 to 272) | 272 (220 to 310) | 293 (220 to 330) | |

d: day; h: hour; n: number of participants; NS: not significant (as reported by study authors).

Wound incision time

Eight studies reported on time to create the wound (Dixon 1990; Elbohoty 2015; Johnson 1990; Kearns 2001; Pearlman 1991; Prakash 2015; Telfer 1993; Siraj 2011);

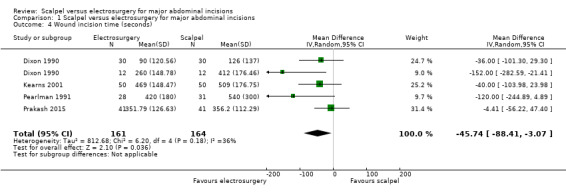

Four studies reported mean time (Dixon 1990; Kearns 2001; Pearlman 1991; Prakash 2015). There was no clinically important difference in mean incision time between electrosurgery and scalpel (MD ‐45.74 seconds, 95% CI ‐88.41 to ‐3.07; 325 participants; 4 studies; I2 = 36%; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.4), given the usual duration of the entire procedure that range from close to one hour in herniorrhaphy cases to several hours in others. The quality of the evidence was moderate. It was downgraded once for serious imprecision. In Dixon 1990 where incision time was considered separately for the two types of procedures, the MD was ‐36.00 seconds (95% CI ‐101.30 to 29.30) for herniorrhaphy cases and ‐152.00 seconds (95% CI ‐282.59 to ‐21.41) for cholecystectomy cases.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Scalpel versus electrosurgery for major abdominal incisions, Outcome 4 Wound incision time (seconds).

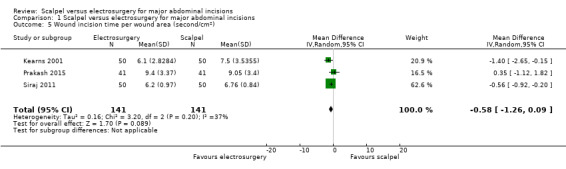

Three studies reported on wound incision time per wound area (Kearns 2001; Prakash 2015; Siraj 2011). It was unclear whether there was a difference in wound incision time per wound area between electrosurgery and scalpel (MD ‐0.58 seconds/cm2, 95% CI ‐1.26 to 0.09; 282 participants; 3 studies; I2 = 37%; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.5). The certainty of evidence was low, downgraded twice for very serious imprecision.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Scalpel versus electrosurgery for major abdominal incisions, Outcome 5 Wound incision time per wound area (second/cm2).

Three studies reported median time (Elbohoty 2015; Johnson 1990; Telfer 1993). The wound incision time was seven minutes in the electrosurgery group versus 10 minutes in the scalpel group (P value presented, however, no further information) (Elbohoty 2015); 3.3 minutes for the electrosurgery group compared with 3.5 minutes for the scalpel group (no further information) (Johnson 1990); and six minutes for the electrosurgery group compared with five minutes for the scalpel group (P value presented, however, no further information) (Telfer 1993). No further analysis was carried out.

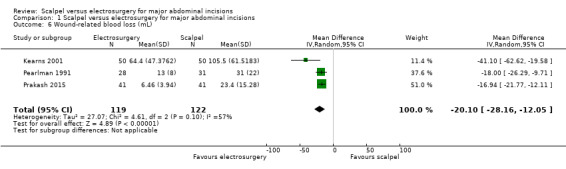

Wound‐related blood loss

Six studies reported wound‐related blood loss as mean, median, and mean per wound area. There was no clinically important difference in mean blood loss between electrosurgery and scalpel (MD ‐20.10 mL, 95% CI ‐28.16 to ‐12.05; 241 participants; 3 studies; I2 = 57%; random‐effects model; Analysis 1.6). The certainty of evidence was moderate due to serious imprecision resulting from the small sample size.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Scalpel versus electrosurgery for major abdominal incisions, Outcome 6 Wound‐related blood loss (mL).

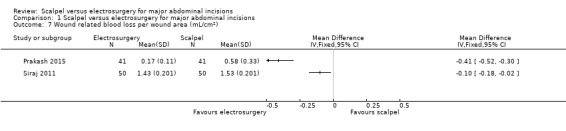

Results from two additional studies were not pooled due to insufficient data (Elbohoty 2015; Telfer 1993), therefore, it is uncertain whether electrosurgery decreases median wound‐related blood loss. Two studies reported on mean wound‐related blood loss per wound area; however, we were unable to pool the studies due to considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 95%). Therefore, it is uncertain whether electrosurgery decreases wound‐related blood loss per wound area. The evidence from the individual studies had serious imprecision (sample size ranging from 82 to 100).

Adhesion or scar formation

One study reported scar formation (Dixon 1990). Dixon 1990 rated the cosmetic appearance of scars as excellent, fair, or poor by participants, surgeon and an independent assessor. No further analysis was carried out (see Table 6).

5. Adhesion or scar formation.

| Dixon 1990 | Herniorrhaphy (60 wounds; number (%)) | Cholecystectomy (24 wounds; number) | |||||||

| Assessor | Group | Excellent | Fair | Poor | P value | Excellent | Fair | Poor | P value |

| Participant | Scalpel | 14 (47) | 13 (43) | 3 (10) | NS | 4 | 6 | 2 | NS |

| Electrosurgery | 22 (73) | 8 (27) | 0 | 8 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Surgeon | Scalpel | 6 (20) | 20 (67) | 4 (13) | < 0.001 | 3 | 8 | 1 | NS |

| Electrosurgery | 21 (70) | 9 (30) | 0 | 7 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Nurse | Scalpel | 8 (27) | 16 (53) | 6 (20) | < 0.01 | 5 | 5 | 2 | NS |

| Electrosurgery | 20 (67) | 9 (30) | 1 (3) | 6 | 3 | 3 | |||

NS: not significant (as reported by study authors).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Sixteen RCTs comparing scalpel with electrosurgery were included in this review of which nine studies were from the previous version of the review. All 16 included studies except one (Telfer 1993) were suitable for inclusion in a meta‐analysis. The studies which provided sufficient data analysed 2711 participants. The results are summarised in Table 1.

There was no clear difference in wound infection events between electrosurgery and scalpel (low‐certainty evidence).

None of the studies reported time to wound healing.

It was unclear if electrosurgery decreased wound dehiscence (very low‐certainty evidence).

There was no clinically important difference in wound incision time between electrosurgery and scalpel (moderate‐certainty evidence). There was no clear difference in incision time per wound area between electrosurgery and scalpel (low‐certainty evidence).

There was no clinically important difference in wound‐related blood loss between electrosurgery and scalpel (low‐certainty evidence).

We were unable to pool data on wound‐related blood loss per wound area, postoperative pain, and adhesion or scar formation. Therefore, it was uncertain whether electrosurgery improved these outcomes.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Sixteen RCTs met the inclusion criteria of this review. The studies recruited 2769 participants aged between 18 and 100 years with different surgical indications. There was no evident exclusion of particular patient groups from the included studies, therefore, the results of this study would apply to a wide range of people undergoing surgery requiring abdominal incision. However, due to the significant discrepancies in surgical indication, underlying pathology, surgical approach, surgical technique, surgeon type, and wound biology, the overall effects demonstrated in this review should be interpreted with caution. We encourage the reader to also examine specific included studies with surgical characteristics consistent with their particular interest. In addition, there was notable variation among studies with regard to the detailed application of the main (electrosurgery) and the comparison (scalpel) intervention for dividing specific layers of abdominal wall. Frequently, the assigned intervention was not the sole tool used for dividing all layers of the abdominal wall and both electrosurgery and scalpel were employed to divide different layers of the abdominal wall in cases assigned to one intervention. Most outcomes prespecified in the protocol were reported though we were unable to meta‐analyse data on postoperative pain and scar formation. Time to wound healing was not reported. Note that post‐hoc subgroup analysis comparing wound infection between the study groups in all strata of wound classification based on degree of contamination were carried out in an attempt to evaluate the effect of wound contamination on infection. However, wound classification was not consistently reported in most of the included studies. Other clinical factors that could affect wound outcomes such as body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, performance status, methods of wound closure, and surgeon's experience were not adequately addressed in the included studies and should be considered in the future studies.

Quality of the evidence

Following a GRADE assessment, the certainty of evidence was moderate to very low across the outcomes assessed. All the included studies were at high risk of bias mostly due to performance bias and 12 of these studies were at risk of bias for additional reasons. While participant blinding was achieved in a few studies, it would not have been feasible to blind the surgeons due to the nature of intervention. Nine of the 16 included studies reported blind outcome assessment while seven studies were at unclear risk of detection bias. As stated earlier, detection bias took precedence over performance bias when we downgraded evidence for risk of bias (see: Blinding (performance bias and detection bias)). Almost all the studies (13/16: 81%) were at high or unclear risk of selection bias. Furthermore, there were many cases of selective reporting where study authors failed to report measures of variance and when contacted failed to provide details. We rarely downgraded for inconsistency as the meta‐analyses had I2 values which suggested heterogeneity that was interpreted as either moderate or not important. However, we did not pool data for the wound‐related blood loss per wound area outcome due to considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 95%). All outcome results were imprecise due to small sample size or limited number of outcome events, or both.

There was no downgrading for indirectness as the included studies were in agreement with the review question. The only outcome assessed for publication bias was the wound infection outcome. A visual inspection of the funnel plot revealed no evidence of publication bias, therefore, the evidence was not downgraded for publication bias.

Potential biases in the review process

We made a concerted effort to prevent biases during the review process by ensuring an extensive literature search and strict adherence to the published protocol. However, following the upgrade Review Manager 5 in recent years, new methods which were not previously considered were subsequently included in the review. These changes have been highlighted under the Differences between protocol and review section. These additions only serve to ensure a more robust process and methodology, we do not therefore consider them to be of concern. Husnain 2006 met our inclusion criteria; however, this was one of a few studies which were not available on the journal website (www.jsp.org.pk). We contacted the journal editor several times and were assured that efforts would be made to retrieve and send the article; however, we did not receive it. Fifty percent of the included studies reported on postoperative pain yet we were unable to pool studies in a meta‐analysis. Efforts to contact study authors to request missing data on measures of variance were unsuccessful (Kearns 2001; Siraj 2011). The protocol was not specific with regards to which measure of postoperative pain and scar formation was preferred. We avoided selective reporting by extracting all available information for outcomes specified in the review protocol.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results of this review are in agreement with the NICE guidance published in 2008, which found no difference in SSI between electrosurgery and scalpel and does not recommend the use of electrosurgery for surgical incision (NICE 2008).

In Chrysos 2005, electrosurgery (65 participants) and scalpel (68 participants) incisions in tension‐free inguinal herniorrhaphy were compared for wound complications (wound strength, wound infection), the requirement for postoperative analgesia, and wound blood loss. The two groups were comparable in terms of wound strength, infectious complications (totally absent), and wound blood loss. Participants in the electrosurgery group required less parenteral analgesia on the first postoperative day. A higher proportion of participants in the scalpel group continued to need oral analgesics on the second postoperative day compared with participants in the electrosurgery group. The findings concerning wound complications and postoperative pain (need for analgesics) were in line with our review results. This was a prospective study comparing electrosurgery and scalpel incisions in tension‐free inguinal hernioplasty. Participants were allocated alternately to the intervention, so this was not true randomisation.

One cross‐sectional study compared electrosurgery in coagulation mode (433 participants) with cold scalpel (531 participants) for severe wound complications in participants undergoing midline abdominal incision for uterine malignancies (Franchi 2001). There was a higher incidence of severe wound complications in the scalpel group (8/531 versus 1/433; P < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences between groups after adjustment for confounding variables. These results support the safety of electrosurgery for making midline abdominal incisions.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is currently insufficient evidence on the relative effectiveness of electrosurgery compared with scalpel in abdominal surgery. While current data suggest there may be no clear difference in wound infections between the treatments, the evidence is low certainty as estimates are imprecise and span estimates consistent with both benefits and harms. Given this, decision makers are likely to follow current local and national guidelines until further evidence is available.

Implications for research.

There is a lack of high‐quality evidence on the effect of scalpel compared to electrosurgery on abdominal incisions. If this is deemed an important question to decision makers, further randomised controlled trials in the area may be warranted. Such trials should assess outcomes such as time to complete wound healing. Since incomplete outcome reporting was an important limitation in this review, future trials should follow the CONSORT statement. The reporting of outcomes such as pain should be more standardised and reported at the same time points across studies (with measures of variance) to enable data pooling. Future studies should report on wound healing as time‐to‐event data, assess clinical factors potentially affecting wound outcomes, include adequate sample sizes, and ensure complete reporting of continuous outcomes with measures of variance. Furthermore, a study designed to address the effect of coagulating‐mode electrosurgery would be worthwhile.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 June 2017 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Seven additional studies included in the review and conclusions changed. |

| 1 June 2017 | New search has been performed | First update, new search. GRADE assessment of certainty of the evidence undertaken and methodology updated. ZIE and EM joined the author team. |

| 11 April 2017 | Amended | Title changed from 'Scalpel versus electrosurgery for abdominal incisions' following peer review feedback. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2006 Review first published: Issue 6, 2012

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 December 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 13 December 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment. |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the peer referees (Jason Wong, Kurinchi Gurusamy, Jac Dinnes, Peter Moore and Jane Nadel) for their comments on the review. We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Jenny Bellorini and Anne Lawson (copy editors) of Narain Chotirosniramit who contributed to the original version of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Glossary of terms

Dehiscence: splitting open of the incision.

Haematoma: swelling due to an accumulation of blood.

Hernioplasty: when herniotomy is combined with a reinforced repair of the posterior inguinal canal wall with autogenous (person's own tissue) or heterogeneous material, such as Prolene mesh.

Herniorrhaphy: operation in which no autogenous or heterogeneous material is used for reinforcement.

Keloid: formation of unsightly scar tissue.

Musculoaponeurosis: layer of muscle and fibrous tissue that holds the abdominal viscera in place and controls movement of the trunk, located deep to the skin and subcutaneous tissue layer.

Seroma: swelling due to accumulation of serum.

Wound dehiscence: proportion of wounds breaking down.

Appendix 2. Search strategies

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Clinical Trials (CENTRAL)

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Electrosurgery] explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor: [Cautery] explode all trees #3 electrosurg* or electrodissect* or electrocaut* or electrocoagul*:ti,ab,kw #4 thermocaut* or thermocoagul* #5 diathermy or diathermi:ti,ab,kw #6 "cold knife":ti,ab,kw #7 scalpel*:ti,ab,kw #8 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 #9 MeSH descriptor: [Abdomen] explode all trees #10 abdomen near/5 (surg* or operation* or incision*):ti,ab,kw #11 abdominal near/5 (surg* or operation* or incision*):ti,ab,kw #12 MeSH descriptor: [Colorectal Surgery] explode all trees #13 MeSH descriptor: [Laparotomy] explode all trees #14 MeSH descriptor: [Hysterectomy] explode all trees #15 MeSH descriptor: [Appendectomy] explode all trees #16 MeSH descriptor: [Cholecystectomy] explode all trees #17 hysterectomy or laparotomy or cholecystectomy or appendectomy or appendicitis or "colorectal surgery":ti,ab,kw #18 MeSH descriptor: [Hernia] explode all trees #19 hernia:ti,ab,kw #20 #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 #21 #8 and #20 in Trials

Ovid MEDLINE

1 exp Electrosurgery/ 2 exp Cautery/ 3 (electrosurg$ or electrodissect$ or electrocaut$ or electrocoagul$).ti,ab. 4 (thermocaut$ or thermocoagul$).ti,ab. 5 (diathermy or diathermi$).ti,ab. 6 cold knife.ti,ab. 7 or/1‐6 8 exp Abdomen/ 9 (abdomen adj5 (surg$ or operation$ or incision$)).ti,ab. 10 (abdominal adj5 (surg$ or operation$ or incision$)).ti,ab. 11 exp Colorectal Surgery/ 12 exp Laparotomy/ 13 exp Hysterectomy/ 14 exp Appendectomy/ 15 exp Cholecystectomy/ 16 (hysterectomy or laparotomy or cholecystectomy or appendectomy or appendicitis or colorectal surgery).ti,ab. 17 exp Hernia/ 18 hernia.ti,ab. 19 or/8‐18 20 and/7,19 21 randomized controlled trial.pt. 22 controlled clinical trial.pt. 23 randomi?ed.ab. 24 placebo.ab. 25 clinical trials as topic.sh. 26 randomly.ab. 27 trial.ti. 28 or/21‐27 29 exp animals/ not humans.sh. 30 28 not 29 31 and/20,30

Ovid Embase

1 exp electrosurgery/ 2 exp Cauterization/ 3 (electrosurg$ or electrodissect$ or electrocaut$ or electrocoagul$).ti,ab. 4 (thermocaut$ or thermocoagul$).ti,ab. 5 (diathermy or diathermi$).ti,ab. 6 cold knife.ti,ab. 7 or/1‐6 8 exp Abdominal Surgery/ 9 (abdomen adj5 (surg$ or operation$ or incision$)).ti,ab. 10 (abdominal adj5 (surg$ or operation$ or incision$)).ti,ab. 11 exp Colorectal Surgery/ 12 exp Laparotomy/ 13 exp Hysterectomy/ 14 exp Appendectomy/ 15 exp Cholecystectomy/ 16 (hysterectomy or laparotomy or cholecystectomy or appendectomy or appendicitis or colorectal surgery).ti,ab. 17 exp Hernia/ 18 hernia.ti,ab. 19 or/8‐18 20 and/7,19 21 Randomized controlled trials/ 22 Single‐Blind Method/ 23 Double‐Blind Method/ 24 Crossover Procedure/ 25 (random* or factorial* or crossover* or cross over* or cross‐over* or placebo* or assign* or allocat* or volunteer*).ti,ab. 26 (doubl* adj blind*).ti,ab. 27 (singl* adj blind*).ti,ab. 28 or/21‐27 29 exp animals/ or exp invertebrate/ or animal experiment/ or animal model/ or animal tissue/ or animal cell/ or nonhuman/ 30 human/ or human cell/ 31 and/29‐30 32 29 not 31 33 28 not 32 34 and/20,33

EBSCO CINAHL Plus

S33 S19 AND S32 S32 S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 OR S27 OR S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 S31 TI allocat* random* or AB allocat* random* S30 MH "Quantitative Studies" S29 TI placebo* or AB placebo* S28 MH "Placebos" S27 TI random* allocat* or AB random* allocat* S26 MH "Random Assignment" S25 TI randomi?ed control* trial* or AB randomi?ed control* trial* S24 AB ( singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl* ) and AB ( blind* or mask* ) S23 TI ( singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl* ) and TI ( blind* or mask* ) S22 TI clinic* N1 trial* or AB clinic* N1 trial* S21 PT Clinical trial S20 MH "Clinical Trials+" S19 S7 and S18 S18 S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 S17 TI hernia or AB hernia S16 (MH "Hernia+") S15 TI (hysterectomy or laparotomy or cholecystectomy or appendectomy or appendicitis or colorectal surgery ) or AB ( hysterectomy or laparotomy or cholecystectomy or appendectomy or appendicitis or colorectal surgery) S14 (MH "Cholecystectomy") S13 (MH "Appendectomy") S12 (MH "Hysterectomy+") S11 (MH "Laparotomy") S10 TI (abdominal N5 surg* or abdomen N5 operation* or abdomen N5 incision* ) or AB ( abdominal N5 surg* or abdomen N5 operation* or abdomen N5 incision*) S9 TI (abdomen N5 surg* or abdomen N5 operation* or abdomen N5 incision* ) or AB ( abdomen N5 surg* or abdomen N5 operation* or abdomen N5 incision*) S8 (MH "Abdomen+") S7 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 S6 TI cold knife or AB cold knife S5 TI diatherm* or AB diatherm* S4 TI (thermocaut* or thermocoagul* ) or AB ( thermocaut* or thermocoagul*) S3 TI (electrosurg* or electrodissect* or electrocaut* or electrocoagul* ) or AB ( electrosurg* or electrodissect* or electrocaut* or electrocoagul*) S2 (MH "Cautery+") S1 (MH "Electrosurgery")

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Scalpel versus electrosurgery for major abdominal incisions.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Wound infection | 11 | 2178 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.74, 1.54] |

| 2 Wound infection (subgroup analysis) | 3 | 936 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.60, 1.22] |

| 2.1 Clean wound (Class I) | 3 | 254 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.26, 1.75] |

| 2.2 Clean‐contaminated wound (Class II) | 3 | 490 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.49, 1.38] |

| 2.3 Contaminated wound (Class III) | 3 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.46, 2.51] |

| 2.4 Dirty wound (Class IV) | 3 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.43, 2.02] |

| 3 Wound dehiscence | 6 | 1064 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.58, 2.50] |

| 4 Wound incision time (seconds) | 4 | 325 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐45.74 [‐88.41, ‐3.07] |

| 5 Wound incision time per wound area (second/cm2) | 3 | 282 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.58 [‐1.26, 0.09] |

| 6 Wound‐related blood loss (mL) | 3 | 241 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐20.10 [‐28.16, ‐12.05] |

| 7 Wound related blood loss per wound area (mL/cm2) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Scalpel versus electrosurgery for major abdominal incisions, Outcome 7 Wound related blood loss per wound area (mL/cm2).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Argerich 2005.

| Methods | Study design: prospective RCT in a single institution. Randomisation method: not stated. Number of participants randomised: 204. Number of participants analysed: 204 (100 in scalpel group, 104 in electrosurgery group). Analysis: full ITT. |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: people undergoing abdominal surgical procedures. Location: University Hospital, Santa Maria, Brazil. Enrolment period: 15 months (August 1999 to November 2000). Exclusion criteria: people with operative wounds that did not include all layers of abdominal wall (skin, subcutaneous cellular tissue, muscle, and fascia). Age: < 40 to 100 years. Sex: not stated. Time of last evaluation: 30 days after surgery. |

|

| Interventions | Scalpel group: operative wounds created with scalpel from skin to fascia. Electrosurgery group: operative wounds created with scalpel for cutaneous incision and electrocautery, in 'coagulation' mode, for the remaining layers. |

|

| Outcomes | Surgical wound infection. Surgical time. |

|