Abstract

Background

Dementia is a clinical syndrome with a number of different causes which is characterised by deterioration in cognitive, behavioural, social and emotional functions. Pharmacological interventions are available but have limited effect to treat many of the syndrome's features. Less research has been directed towards non‐pharmacological treatments. In this review, we examined the evidence for effects of music‐based interventions as a treatment.

Objectives

To assess the effects of music‐based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia on emotional well‐being including quality of life, mood disturbance or negative affect, behavioural problems, social behaviour, and cognition at the end of therapy and four or more weeks after the end of treatment.

Search methods

We searched ALOIS, the Specialized Register of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group (CDCIG) on 14 April 2010 using the terms: music therapy, music, singing, sing, auditory stimulation. Additional searches were also carried out on 3 July 2015 in the major healthcare databases MEDLINE, Embase, psycINFO, CINAHL and LILACS; and in trial registers and grey literature sources. On 12 April 2016, we searched the major databases for new studies for future evaluation.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials of music‐based therapeutic interventions (at least five sessions) for people with dementia that measured any of our outcomes of interest. Control groups either received usual care or other activities.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers worked independently to screen the retrieved studies against the inclusion criteria and then to extract data and assess methodological quality of the included studies. If necessary, we contacted trial authors to ask for additional data, including relevant subscales, or for other missing information. We pooled data using random‐effects models.

Main results

We included 17 studies. Sixteen studies with a total of 620 participants contributed data to meta‐analyses. Participants in the studies had dementia of varying degrees of severity, but all were resident in institutions. Five studies delivered an individual music intervention; in the others, the intervention was delivered to groups of participants. Most interventions involved both active and receptive musical elements. The methodological quality of the studies varied. All were at high risk of performance bias and some were at high risk of detection or other bias. At the end of treatment, we found low‐quality evidence that music‐based therapeutic interventions may have little or no effect on emotional well‐being and quality of life (standardized mean difference, SMD 0.32, 95% CI −0.08 to 0.71; 6 studies, 181 participants), overall behaviour problems (SMD −0.20, 95% CI −0.56 to 0.17; 6 studies, 209 participants) and cognition (SMD 0.21, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.45; 6 studies, 257 participants). We found moderate‐quality evidence that they reduce depressive symptoms (SMD −0.28, 95% CI −0.48 to −0.07; 9 studies, 376 participants), but do not decrease agitation or aggression (SMD −0.08, 95% CI −0.29 to 0.14; 12 studies, 515 participants). The quality of the evidence on anxiety and social behaviour was very low, so effects were very uncertain. The evidence for all long‐term outcomes was also of very low quality.

Authors' conclusions

Providing people with dementia with at least five sessions of a music‐based therapeutic intervention probably reduces depressive symptoms but has little or no effect on agitation or aggression. There may also be little or no effect on emotional well‐being or quality of life, overall behavioural problems and cognition. We are uncertain about effects on anxiety or social behaviour, and about any long‐term effects. Future studies should employ larger sample sizes, and include all important outcomes, in particular 'positive' outcomes such as emotional well‐being and social outcomes. Future studies should also examine the duration of effects in relation to the overall duration of treatment and the number of sessions.

Keywords: Aged, Humans, Music Therapy, Dementia, Dementia/rehabilitation, Dementia/therapy, Mental Disorders, Mental Disorders/therapy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Music‐based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia

Background

People with dementia gradually develop difficulties with memory, thinking, language and daily activities. Dementia is often associated with emotional and behavioural problems and may lead to a reduction in a person's quality of life. In the later stages of dementia it may be difficult for people to communicate with words, but even when they can no longer speak they may still be able to hum or play along with music. Therapy involving music may therefore be especially suitable for people with dementia. Music therapists are specially qualified to work with individuals or groups of people, using music to try to help meet their physical, psychological and social needs. Other professionals may also be trained to provide similar treatments.

Purpose of this review

We wanted to see if we could find evidence that treatments based on music improve the emotional well‐being and quality of life of people with dementia. We were also interested in evidence about their effects on emotional, behavioural, social or cognitive (e.g. thinking and remembering) problems in people with dementia.

What we did

We searched for trials in which people with dementia were randomly allocated to a music‐based treatment or to a comparison group, and in which any of the outcomes we were interested in were measured. The comparison groups might have had no special treatment, or might have been offered a different activity. The trials had to have offered at least five sessions of treatment because we thought fewer sessions than this were unlikely to have much effect. If we judged that the trials were similar enough, then we combined their results in order to estimate the effect of the treatment as accurately as possible.

What we found

We found seventeen trials to include in the review and we were able to combine results for at least some outcomes from 620 people. All of the people in the trials were living in care homes. People with all severities of dementia were included. Some trials compared music‐based treatments with usual care, and some compared it with other activities, such as cooking or painting. The quality of the trials and how well they were reported varied, and this affected our confidence in the results. First, we looked at outcomes immediately after a course of therapy ended. From our results, we could be moderately confident that music‐based treatments improve symptoms of depression, but do not help with agitated or aggressive behaviour. We were less confident in our results on emotional well‐being including quality of life, overall behavioural problems, and cognition, but music‐based treatments may have little or no effect on these outcomes. We had very little confidence in our results on anxiety and social interaction. Some studies also looked to see whether there were any lasting effects four weeks or more after treatment ended. However, there were few data and we were very uncertain about the results. Further trials are likely to have a significant impact on what we know about the effects of music‐based treatments for people with dementia, and so continuing research is important.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Music‐based therapeutic interventions compared to usual care or other activities for people with dementia: end of treatment effects

| Music‐based therapeutic interventions compared to usual care or other activities for people with dementia: end of treatment effects | |||

| Patient or population: people with dementia (all resided in institutional settings) Intervention: music‐based therapeutic interventions Comparison: usual care or other activities | |||

|

Outcomes (end of treatment) measured with a variety of scales except for social behaviour |

Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Score with music therapy compared with usual care or other activities | |||

| Emotional well‐being including quality of life | The score in the intervention group was 0.32 SDs higher (0.08 lower to 0.71 higher) | 181 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 |

| Mood disturbance or negative affect: depression | The score in the intervention group was 0.28 SDs lower (0.48 lower to 0.07 lower) | 376 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 |

| Mood disturbance or negative affect: anxiety | The score in the intervention group was 0.50 SDs lower (0.84 lower to 0.16 lower) | 365 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 5 |

| Behavioural problems: agitation or aggression | The score in the intervention group was 0.08 SDs lower (0.29 lower to 0.14 higher) | 515 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 |

| Behavioural problems: overall | The score in the intervention group was 0.20 SDs lower (0.56 lower to 0.17 higher) | 209 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 |

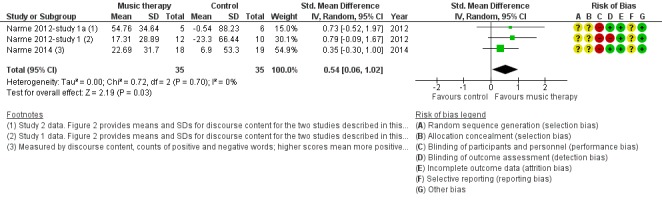

| Social behaviour: music vs other activities | The score in the intervention group was 0.54 SDs higher (0.06 higher to 1.02 higher) | 70 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 4 |

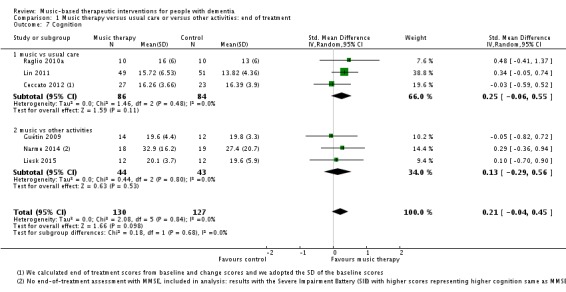

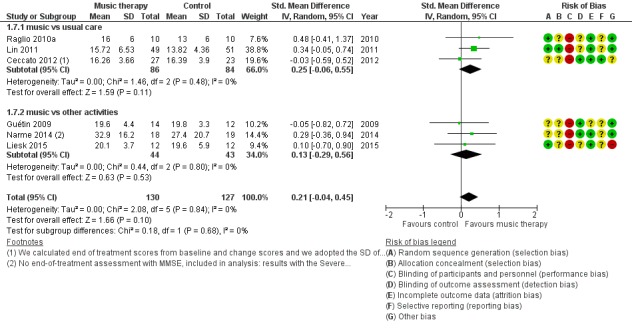

| Cognition | The score in the intervention group was 0.21 SDs higher (0.04 lower to 0.45 higher) | 257 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 |

| *Interpretation of SMD: a difference of < 0.40 standard deviations can be regarded as a small effect, 0.40 to 0.70 a moderate effect, and > 0.70 a large effect. CI: Confidence interval; SMD: standardised mean difference; SD: standard deviation | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||

1 Risk of bias: no blinding of therapists and patients (not possible), and often no blinding of outcome assessment

2 Imprecision: small number of participants and rather broad confidence interval

3 Inconsistency: more non‐overlapping confidence intervals

4 Imprecision: very small number of participants and broad confidence interval

5 Publication bias: funnel plot is based on a limited number of studies but suggests there may be publication bias

Summary of findings 2.

Music‐based therapeutic interventions compared to usual care or other activities for people with dementia: long‐term effects (scores 4 weeks or more after treatment ended)

|

Music‐based therapeutic interventions compared to usual care or other activities for people with dementia: long‐term effects (scores 4 weeks or more after treatment ended) Interpretation of SMD: a difference of < 0.40 standard deviations can be regarded as a small effect, 0.40 to 0.70 a moderate effect, and > 0.70 a large effect. | |||

| Patient or population: people with dementia (all resided in institutional settings) Intervention: music‐based therapeutic interventions Comparison: usual care or other activities | |||

|

Outcomes (long‐term) measured with a variety of scales except for social behaviour |

Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Score with music therapy compared with usual care or other activities | |||

| Emotional well‐being including quality of life | The score in the intervention group was 0.47 SDs higher (0.10 lower to 1.05 higher) | 48 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 |

| Mood disturbance or negative affect: depression | The score in the intervention group was 0.01 SDs lower (0.27 lower to 0.24 higher) | 234 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 |

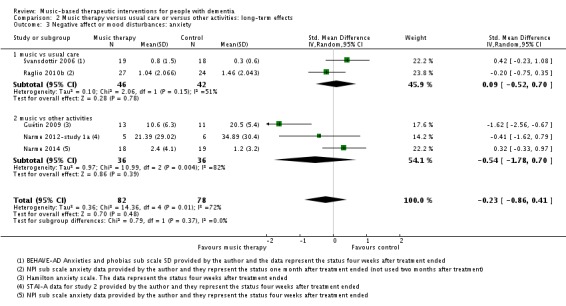

| Mood disturbance or negative affect: anxiety | The score in the intervention group was 0.23 SDs lower (0.86 lower to 0.41 higher) | 160 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 4 |

| Behavioural problems: agitation or aggression | The score in the intervention group was 0.02 SDs lower (0.36 lower to 0.33 higher) | 225 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 4 |

| Behavioural problems: overall | The score in the intervention group was 0.05 SDs higher (0.30 lower to 0.41 higher) | 125 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 |

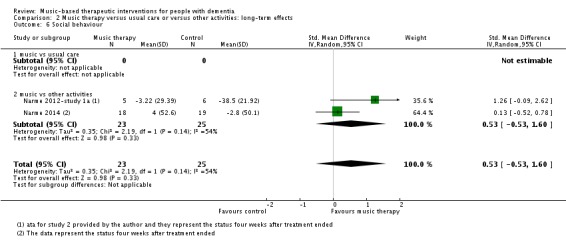

| Social behaviour ‐ music vs other activities | The score in the intervention group was 0.53 SDs higher (0.53 lower to 1.6 higher) | 48 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 |

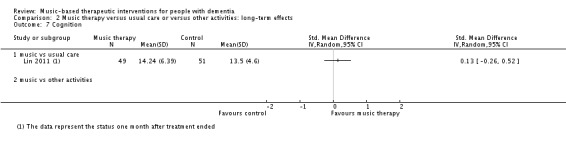

| Cognition ‐ music vs usual care | The score in the intervention group was 0.13 SDs higher (0.26 lower to 0.52 higher) | 100 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 |

| *Interpretation of SMD: a difference of < 0.40 standard deviations can be regarded as a small effect, 0.40 to 0.70 a moderate effect, and > 0.70 a large effect. CI: Confidence interval; SMD: standardised mean difference; SD: standard deviation | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||

1 Risk of bias: no blinding of therapists and patients (not possible), and no blinding of outcome assessment

2 Imprecision: very small number of participants and broad confidence interval includes both benefit and harm

3 Imprecision: small number of participants and rather broad confidence interval

4 Inconsistency: multiple non‐overlapping confidence intervals

Background

Description of the condition

Dementia is a clinical syndrome characterised by progressive decline in cognitive functions. Dementia of the Alzheimer's type is the most common form of dementia, followed by vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia and frontotemporal dementia (ADI 2015).

Dementia is a collective name for progressive degenerative brain syndromes which affect memory, thinking, behaviour and emotion (ADI 2015). Symptoms may include:

loss of memory;

difficulty in finding the right words or understanding what people are saying;

difficulty in performing previously routine tasks;

personality and mood changes.

Alzheimer’s Disease International estimates that worldwide currently 46.8 million people are suffering from dementia; and that this figure will increase to 74.7 million by 2030 and to 131.5 million people by 2050 (ADI 2015).

Research is pursuing a variety of promising findings related to describing the causes of dementia and for the treatment of dementia. Pharmacological interventions are available but have limited ability to treat many of the syndrome's features. Little research has been directed towards non‐pharmacological treatments.

As dementia is due to damage to the brain, one approach is to limit the extent and rate of progression of the pathological processes producing this damage. At present the scope of this approach is limited and an equally important approach is to help people with dementia and their caregivers to cope with the syndrome's social and psychological manifestations. As well as trying to slow cognitive deterioration, care should aim to stimulate abilities, improve quality of life, and reduce problematic behaviours associated with dementia. The therapeutic use of music might achieve these aims.

Description of the intervention

Many treatments of dementia depend on the client's ability to communicate verbally. When the ability to speak or understand language has been lost, music might offer alternative opportunities for communication. People who cannot speak anymore may still be able to hum or play along with music.

Music therapy is defined by the World Federation of Music Therapy (WFMT) as "the professional use of music and its elements as an intervention in medical, educational, and everyday environments with individuals, groups, families, or communities who seek to optimize their quality of life and improve their physical, social, communicative, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual health and wellbeing". Research, practice, education, and clinical training in music therapy are based on professional standards according to cultural, social, and political contexts (WFMT, 2011). The American Music Therapy Association (AMTA) defines music therapy as "the clinical and evidence‐based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy program" (AMTA). It describes assessment of the client, interventions ("including creating, singing, moving to, and/or listening to music"), benefits and research, and explains that music therapy is used "within a therapeutic relationship to address physical, emotional, cognitive, and social needs of individuals". We reviewed music‐based interventions, which may share these therapeutic goals even if not provided by an accredited music therapist.

Two main types of music therapy can be distinguished — receptive (or passive) and active music therapy — and these are often combined (Guetin 2013). Receptive music therapy consists of listening to music by the therapist who sings, plays or selects recorded music for the recipients. In active music therapy, recipients are actively involved in the music‐making, by playing on small instruments for instance. The participants may be encouraged to participate in musical improvisation with instruments or voice, with dance, movement activities or singing.

Music may also be used in ways which are less obviously therapy or therapeutic, for example playing music during other activities such as meals or baths, or during physiotherapy or movement, or as part of an arts programme or other psychosocial interventions. 'Music as therapy' includes more narrowly defined music therapy provided by "a formally credentialed music major with a therapeutic emphasis" (Ing‐Randolph 2015). In order to benefit people with dementia, those providing music‐based interventions with a therapeutic goal may need to draw on the skills of both musicians and therapists to select and apply musical parameters adequately, tailored to a recipient's individual needs and goals.

How the intervention might work

Music‐based therapeutic interventions, including interventions provided by a certified music therapist, mostly consist of singing, listening, improvising or playing along on musical instruments. Music and singing may stimulate hemispheric specialization. Clinical observations indicate that singing critically depends upon right‐hemisphere structures. By contrast, people suffering from aphasia due to left‐hemisphere lesions often show strikingly preserved vocal music capabilities. Singing may be exploited to facilitate speech reconstruction when suffering from aphasia (Riecker 2000). Singing can further help the development of articulation, rhythm, and breath control. Singing in a group setting can improve social skills and foster a greater awareness of others. For those with dementia, singing may encourage reminiscence and discussions of the past, while reducing anxiety and fear. For individuals with compromised breathing, singing can improve oxygen saturation rates. For individuals who have difficulty speaking following a stroke, music may stimulate the language centres in the brain promoting the ability to sing. In sum, singing may improve a range of physical and psychosocial parameters (Clift 2016). Playing instruments may improve gross and fine motor coordination in individuals with motor impairments or neurological trauma related to a stroke, head injury or a disease process (Magee 2017; WFMT, 2010).

Whereas cognitive functions decline during disease progression, receptivity to music may remain until the late phases of dementia (Adridge 1996; Baird 2009; Cowles 2003 ). Even in the latest stage of the disease, they may remain responsive to music where other stimuli may no longer evoke a reaction (Norberg 1986).This may be related to musical memory regions in the brain being relatively spared in Alzheimer's disease (Jacobsen 2015). Possibly, the fundamentals of language are musical, and precede lexical functions in language development (Adridge 1996). Listening to music itself may decrease stress hormones such as cortisol; and helps patients to cope with, for instance, pre‐operative stress (Spintge 2000). Music therapy can bring relaxation and has a positive effect on enhancing communication and emotional well‐being (Brotons 2000). Music therapy enables the recall of life experiences and the experience of emotions. Many important life events are accompanied by music; most of the time these 'musical memories' are stored for a longer time than the ones from the same period that were not accompanied by music (Broersen 1995; Baird 2009). If words are not recognized any longer, familiar music may provide a sense of safety and well‐being, which in turn may decrease anxiety.Musical rhythm may help people with Alzheimer's disease to organize time and space. Patients are able to experience group contact through musical communication with other participants, without having to speak. Owing to its non‐verbal qualities, music‐based interventions might help people with dementia at all levels of severity to cope with the effects of their illness.

Why it is important to do this review

In this review we examine current research literature to assess whether music‐based therapeutic interventions, including music therapy, are an efficacious approach to the treatment of emotional, behavioural, social, and cognitive problems in people with dementia. We also investigate whether, in the absence of specific problems, these interventions have an effect on emotional well‐being, including quality of life, or social behaviour in people with dementia. Quality of life is often an appropriate goal of care for people with dementia (ADI 2016), and it is important to assess evidence as to whether music‐based therapeutic intervention can contribute to quality of life or related outcomes.

Objectives

To assess the effects of music‐based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia on emotional well‐being including quality of life, mood disturbance or negative affect, behavioural problems, social behaviour, and cognition at the end of therapy and four or more weeks after the end of treatment

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included both parallel and cross‐over randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

We included people who were formally diagnosed as having any type of dementia according to DSM‐IV or DSM‐5, ICD‐10 or other accepted diagnostic criteria. In order to be relevant to clinical practice, we also accepted a physician's diagnosis of dementia if no data on formal criteria such as DSM‐IV, DSM‐5 or comparable instruments were available. We included people living in diverse settings including in the community, hospitals or nursing homes and all severities of dementia. We did not use a criterion for age so as not to exclude studies in which some participants were below age 65.

Types of interventions

We included any music‐based interventions, either active or receptive, delivered to individuals or groups. We required a minimum of five sessions in order to ensure that a therapeutic intervention could have taken place. We defined therapeutic music‐based interventions as: therapy provided by a qualified music therapist, or interventions based on a therapeutic relationship and meeting at least two of the following criteria/indicators: (a) therapeutic objective which may include communication, relationships, learning, expression, mobilisation and other relevant therapeutic objectives; (b) music matches individual preferences; (c) active participation of the people with dementia using musical instruments or singing; (d) participants had a clinical indication for the intervention or were referred for the intervention by a clinician. We also required music to be a main element of the intervention (e.g. not merely moving with use of music). Simple participation in a choir would not meet our definition of a therapeutic intervention.

The music‐based interventions could be compared with any other type of therapy or no therapy. Control groups could not receive any music‐based therapeutic intervention (even if fewer sessions than the intervention group).

Types of outcome measures

Emotional well‐being, including quality of life and positive affect. Facial expressions (in the absence of interaction with the observer) may also indicate emotional well‐being.

Mood disturbance or negative affect: depression (depressive symptoms) or anxiety.

Behavioural problems: agitation and/or aggression, overall behavioural problems or neuropsychiatric symptoms. (We combined agitation and aggression outcomes consistent with the International Psychogeriatric Association consensus definition of agitation requiring presence of one of "excessive motor activity, verbal aggression, or physical aggression" (Cummings 2015)).

Social behaviour, such as (verbal) interaction.

Cognition.

Any other adverse effects.

For these outcomes, we accepted all assessment tools used in the primary studies. Outcomes were assessed at the end of treatment (a minimum of five sessions), irrespective of the duration and number of sessions in excess of four. If there was evidence of no different effect over time, then reported outcomes could include earlier assessments. We also looked for outcomes a minimum of four weeks after the treatment ended in order to assess long‐term effects.

Primary outcomes

The protocol did not prioritise outcomes. We prioritised the outcomes related to emotions (emotional well‐being including quality of life, and mood disturbance or negative affect) as being of critical importance because these outcomes (e.g. depression) are closely related to quality of life of people with dementia (Banerjee 2009; Beerens 2014). Depression and anxiety are also prevalent and rather persistent during the course of the dementia (van der Linde 2016; Zhao 2016). We further prioritised behavioural problems because these affect relationships and caregiver burden (e.g. van der Linde 2012); and some may also be indicators of distress.

Secondary outcomes

Social behaviour and cognition were important but secondary outcomes, as the benefit for the participants themselves was not as obvious as for outcomes more closely related to their quality of life.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched ALOIS, the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group’s Specialized Register. The search terms used were: music therapy, music, singing, sing, auditory stimulation.

ALOIS is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator for CDCIG and contains studies in the areas of dementia prevention, dementia treatment and cognitive enhancement in the healthy. Details of the search strategies used for the retrieval of reports of trials from the healthcare databases, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and conference proceedings can be viewed in the ‘Methods used in reviews’ section within the editorial information about the Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group. To view a list of all sources searched for ALOIS see About ALOIS on the ALOIS web site.

We performed additional searches in each of the sources listed above to cover the timeframe from the last searches performed for ALOIS to 3 July 2015. The search strategies for the above described databases are presented in Appendix 1.

In addition, we searched Geronlit/Dimdi, Research Index, Carl Uncover/Ingenta, Musica and Cairss in January 2006 and June 2010, with the following search terms: music therapy, music, singing, dance, dementia, alzheimer. We also searched on these dates specific music therapy databases, as made available by the University of Witten‐Herdecke on www.musictherapyworld.de, based in Germany. We checked the reference lists of all relevant articles and a clinical librarian conducted a forward search from key articles using SciSearch. In addition, conference proceedings of European and World Music Therapy conferences on www.musictherapyworld.de and European music therapy journals, such as the Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, the British Journal of Music Therapy the Musiktherapeutische Umschau and the Dutch Tijdschrift voor Vaktherapie were hand searched to find music therapy studies (RCTs) for people with dementia, in January 2006, June 2010, and July 2015. A new database search was performed on 12 April 2016 to identify new studies published after 3 July 2015. Potentially eligible new studies (based on abstract review with two independent reviewers) were included under Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed publications for eligibility by checking the title and, if available, the abstract. If any doubt existed as to an article's relevance they retrieved and assessed the full article.

Data extraction and management

Two reviewers extracted and cross‐checked outcome data independently of each other. They discussed any discrepancies or difficulties with a third reviewer. We reviewed articles in English, French, German and Dutch and searched for Cochrane collaborators to assess articles in other languages. We emailed authors for additional information when unclear (for example, about the type of control group or setting); and for additional data if that would help inclusion of the study data in meta‐analyses (for example, if estimates from graphical presentation were imprecise, SDs were lacking, or item‐level data if items of global tools represented relevant outcomes).

We first extracted data on the design (RCT), population (dementia diagnosis), the criteria for music therapy, outcomes and timing of outcome assessment, to evaluate eligibility of the study, Of the eligible studies, we subsequently recorded the following characteristics.

Data collection period.

Setting: nursing home, residential home, hospital, ambulatory care, other.

Participant characteristics: age, sex, severity and type of the dementia.

Number of participants included, randomized and lost to follow up.

Type, frequency and duration of active interventions and control interventions.

Description of activities in the control group if not usual care.

Outcomes: type of outcome measures about emotional well‐being, emotional problems (mood disturbance or negative affect), problematic or challenging behaviours (in general; and more specifically, agitation or aggression), social behaviours and cognition. Whether outcomes were being referred to as primary or secondary outcomes.

Timing of outcome measurement including the long term, after treatment ended.

Research hypotheses if specified, and a description of the results.

Any methodological problems and comments.

Funding sources.

A 'Risk of bias' assessment (below).

For each study, we extracted relevant outcome data, i.e. means, standard deviations and number of participants in each group for continuous data and numbers with each outcome in each group for dichotomous data. If needed or helpful, we contacted authors for clarification; or for data, such as from relevant subscales.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two reviewers (neither of whom was an author on any of the studies that they assessed) independently of each other assessed included studies for risk of bias according to the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, and using the 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011). They looked at the following elements of study quality: selection bias (random sequence generation, allocation concealment); performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel); detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment); attrition bias (incomplete outcome data); reporting bias (selective reporting); and other potential threats to validity. They assessed performance, detection and attrition bias for each outcome.

Measures of treatment effect

We used the risk ratio to summarize any effects on dichotomous outcome variables and the mean difference (or if different instruments or scales were used, the standardised mean difference) for continuous variables.

Unit of analysis issues

Only participant‐level outcomes were considered, and all were continuous measures. For cross‐over trials, we extracted data for the first period only because of the likelihood of carry‐over.

Dealing with missing data

We considered if there were missing outcome data, with reasons reported, for example due to participants who moved or died, and how these were dealt with (exclusion of cases for analyses or were dealt with otherwise).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We interpreted I² according to criteria in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011: chapter 9.5.2). Further, a low P value for the Chi² statistic indicated heterogeneity of intervention effects, which we evaluated against the combined 'usual care' and 'other activities' control groups. Because of small numbers of participants and studies for most outcomes, a non‐significant P value was not decisive in the evaluation of consistency, and we also considered overlap of confidence intervals in the forest plots.

Assessment of reporting biases

Selective outcome reporting is covered by the risk of bias assessment, and for this we searched the articles about included studies and related articles for references to study protocols and trial registrations. If available, we compared with outcomes and prioritisation of outcomes in the article. If no research protocol was available, risk of reporting bias was set to either unclear, or high when appropriate. To detect possible publication bias, we examined funnel plots for outcomes with at least 10 studies available.

Data synthesis

We included studies about all eligible interventions in similar groups of people in different stages of dementia, and we pooled the results of studies that examined effects on the same seven outcomes. We discriminated between effects at the end of treatment, and long‐term effects (a minimum of four weeks after treatment ended). In case of clinically homogeneous studies, results would have been combined using a fixed‐effect model. In case of statistical heterogeneity (assessed by visual inspection of the forest plots) and the availability of at least five studies, a random‐effects model was used.

We were interested in both usual care and other activity‐control interventions because usual practice with regard to activities offered is variable, and the question as to whether music‐based therapeutic interventions should be introduced and the question as to whether they are superior to other activities are both relevant in practice. We presented data by type of control intervention: usual care or other activities. A control group with other activities controls for increased social contact and stimulation. However, it is unclear whether this increases or decreases contrast with the music‐based intervention group for different outcomes (e.g. agitation, anxiety). We therefore analysed effects against all control groups as planned in the protocol, but for purposes of possible hypothesis generation we present forest plots by subgroup.

With probable selective outcome reporting, we ran the analyses for the reported outcomes while omitting the particular study, to evaluate change and direction of change of the estimate.

Sensitivity analysis

Post hoc, we performed a series of sensitivity analyses because there are different possible criteria as to what constitutes music therapy, and because funding related to music therapy potentially involves an intellectual conflict of interest. We first reran all analyses on end‐of‐treatment effects with studies in which the intervention was probably or definitely (when mentioned explicitly) delivered by a professional music therapist only. Second, we restricted these analyses to studies definitely delivered by a music therapist. Third, we restricted the analyses to studies definitely delivered by a music therapist and with no potential conflict of interest related to funding or no reported funding source.

Presentation of results and 'Summary of findings' table

We used GRADE methods to rate the quality of evidence (high, moderate or low) behind each effect estimate in the review (Guyatt 2011). This rating refers to our level of confidence that the estimate reflects the true effect, taking account of risk of bias in the included studies, inconsistency between studies, imprecision in the effect estimate, indirectness in addressing our review question and the risk of publication bias. We produced 'Summary of findings' tables for end‐of‐treatment and long‐term outcome comparisons to show the effect estimate and the quantity and quality of the supporting evidence for outcomes for which more studies were available. The summary of findings was generated with Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) data imported into the GradePro Guideline Development Tool (2015).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

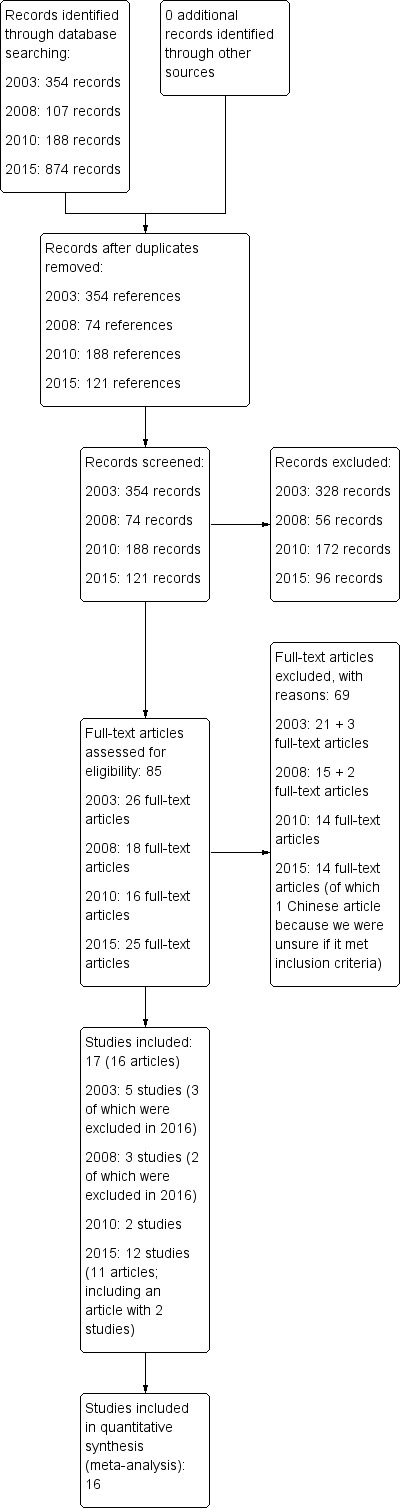

The total number of included studies was 17. For the first version of this review (Vink 2003), we identified 354 references related to music‐based interventions and dementia (Figure 1). Of those, 254 were discarded as they did not refer to a research study or were identified as anecdotal or reports of case studies on the basis of their abstracts. Hard copies were obtained for the remaining 100 studies. We then discarded a further 74 studies as they involved participant series or case studies. A total of 26 studies remained in 2003 of which five met the criteria for inclusion at that time (Groene 1993; Lord 1993; Clark 1998; Brotons 2000; Gerdner 2000). In 2008 an additional eighteen studies were reviewed, of which three studies met the criteria at that time (Sung 2006; Svansdottir 2006; Raglio 2008). For the update of 2010 we retrieved a total of 188 references of possible relevance. After a first assessment 16 references remained which were further assessed, of which two studies met the criteria of this review (Guétin 2009; Raglio 2010b). In total, 10 studies were included in the previous update. In 2015, due to clarified criteria for eligibility of interventions, randomization, and more stringent application of criteria for analyses of outcomes after a minimum number of sessions, we excluded five of the 10 previously included studies (Groene 1993; Brotons 2000; Gerdner 2000; Sung 2006; Raglio 2008; Characteristics of excluded studies). However, we included 12 new studies after evaluating 121 references including 25 full‐text evaluations, which resulted in the total of 17 included studies. A new search on 12 April 2016 identified eight potentially eligible additional studies which still warrant review against inclusion criteria for the next update of this review (Hsu 2015; Raglio 2015; Curto Prieto 2015; Hsiung 2015; Rouch 2017; Thornley 2016; 신보영, 황은영. 2015; 채경숙 2015), in addition to a study for which we are waiting for clarification from the authors about the results (Hong 2011). These are listed under Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Details of the included studies are presented in the Characteristics of included studies table. One article (Narme and colleagues 2012: Narme 2012‐study 1 and Narme 2012‐study 1a) reported on two studies with rather similar designs indicated with study 1 and study 2 in the article (note that study 2 is indicated with 1a in our analyses). More articles with additional results or background of the study were available for five studies (Cooke 2010;Raglio 2010b;Lin 2011;Vink 2013; Narme 2014).

Fourteen studies had a parallel groups design (Lord 1993; Svansdottir 2006; Guétin 2009; Raglio 2010a; Raglio 2010b; Lin 2011; Ceccato 2012; Narme 2012‐study 1 and Narme 2012‐study 1a (also referred to as study 2); Sung 2012; Sakamoto 2013; Vink 2013; Narme 2014; Liesk 2015); and three used a crossover design with first‐period data available for all (Clark 1998; Cooke 2010; Ridder 2013).

The seventeen studies were performed in 11 countries. Whereas the two oldest studies were from the USA (Lord 1993; Clark 1998), the studies published after 1998 were from a variety of other regions and countries: 11 studies conducted in seven countries in Europe (Italy, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Iceland, including also one study performed in two countries, Denmark and Norway; Ridder 2013), three studies from two countries in Asia (Taiwan and Japan), and one study from Australia. The studies were all performed in institutional settings of nursing homes, residential homes and geriatric hospital wards. Dementia severity varied.

The interventions were active (Cooke 2010; Raglio 2010a; Raglio 2010b; Sung 2012; Liesk 2015); receptive (Clark 1998; Guétin 2009); or a mixture of the two forms (the other 10 studies). Appendix 2 describes the music‐based therapeutic intervention and other activities of all studies. Music included live or recorded music that met preferences of the group or individual. The active forms often combined playing of instruments and singing activities, and some also combined with movement such as clapping hands and dance. Sessions varied in duration between half an hour and two hours. The total number of sessions ranged from six (Narme 2012‐study 1) to 156 (Lord 1993), with a median total number of 12 sessions until the end of treatment assessment. The frequency ranged between one session per week (Guétin 2009; Sakamoto 2013) and six sessions per week (Lord 1993), with a median and more typical number (mode) of two sessions per week (two per week was employed in 10 studies). These figures probably reflect number of sessions offered, as the number of attended session may be lower. There are few reports about implementation fidelity including adherence and dose received, but Ridder 2013 reports that a minimum of 12 sessions were offered, but the participants received 10 sessions on average.

In seven of the studies, we could be sure from the report that the interventions had been delivered by an accredited music therapist (Svansdottir 2006; Raglio 2010a; Raglio 2010b; Lin 2011; Ceccato 2012; Ridder 2013; Vink 2013). In four studies, it was unclear whether a music therapist was involved (no profession reported in the older studies, Lord 1993 and Clark 1998; probably delivered by trained music therapists but it was not stated explicitly in Guétin 2009; and delivered by musicians trained in the delivery of sessions and in working with older people with dementia but unclear if these were formally trained music therapists in Cooke 2010). In the other six studies, the intervention was not delivered by a music therapist (psychologist and other supervisor(s) with no training in music therapy, Narme 2012‐study 1; Narme 2012‐study 1a; Narme 2014; trained research assistants, Sung 2012; music facilitator, Sakamoto 2013; music teacher specialised in teaching older people, Liesk 2015).

Seven of the 17 studies compared the music intervention with an active control intervention, all with the same number of sessions and frequency as the music group. Two‐armed studies compared with the following interventions: reading (Cooke 2010; Guétin 2009), a cognitive stimulation intervention (Liesk 2015), painting (Narme 2012‐study 1), cooking (Narme 2012‐study 1 and Narme 2012‐study 1a — also referred to as study 2; Narme 2014), or variable recreational activities which included handwork, playing shuffleboard, and also cooking and puzzle games (Vink 2013). Two studies had three arms with the active control group working on jigsaw puzzles (Lord 1993); or receiving a passive group music intervention which did not meet our inclusion criteria for a therapeutic music‐based intervention (Sakamoto 2013).

The outcomes 'emotional well‐being' including quality of life, mood disturbance or negative affect (also as part of behavioural scales), and 'behavioural problems' (agitation or aggression, and behaviour overall) and 'cognition' were often assessed. Social behaviour was less commonly assessed (Lord 1993; Narme 2012‐study 1; Narme 2012‐study 1a; Narme 2014); and the meta‐analyses of end‐of‐treatment scores included only the three studies from Narme and colleagues. The Cohen‐Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI, for agitation; Cohen‐Mansfield 1986), Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE, for cognition; Folstein 1975), and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI, for behaviour; Cummings 1994) in particular were frequently used. Item‐level NPI outcome data were reported in the article or the author additionally provided data about depression, anxiety, and agitation outcomes.

Excluded studies

We screened a total of 737 records and we excluded 652 (Figure 1). We excluded 69 of 85 records examined in full text (see Characteristics of excluded studies for a selection of excluded studies which were close but did not qualify upon careful consideration). They were often excluded because the participants did not have dementia, or because of a design other than an RCT. Further, and often less obvious, we critically reviewed whether the intervention met the inclusion criteria for a music‐based therapeutic intervention, and whether the reported outcomes included any assessments after fewer than five sessions. There are a number of studies on group music interventions such as group music in addition to movement interventions (e.g. Sung 2006): these were excluded because music was not the main or only therapeutic element, or was not provided with individual therapeutic intent. Further, some studies assessed outcomes during the treatment sessions only, combining immediate effects, for example on behaviour during the first session, with effects after multiple sessions (e.g. Gerdner 2000). Studies awaiting classification included conference abstracts, articles about studies in Asia which we could not retrieve or evaluate in time, and new studies published after the search (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

Risk of bias in included studies

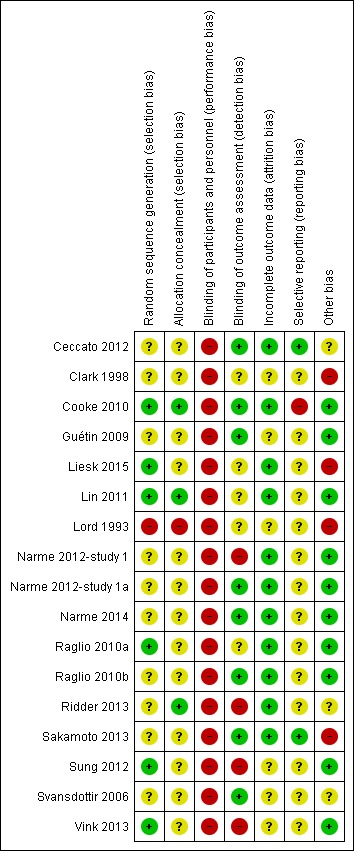

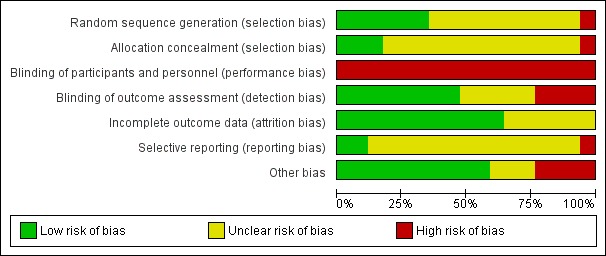

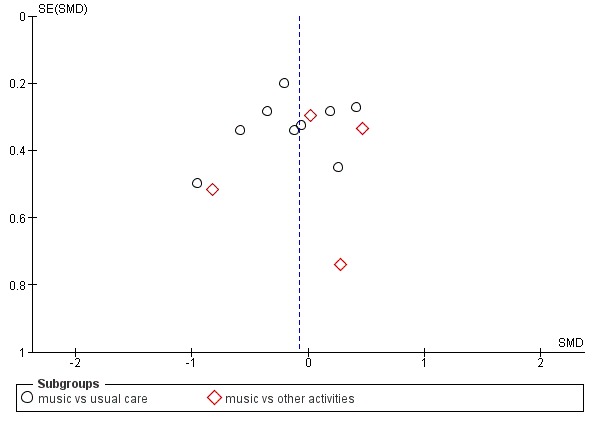

The results of the assessment of risk of bias are presented in the Risk of bias in included studies tables, in Figure 2 and Figure 3, and in funnel plots (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Figure 3.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

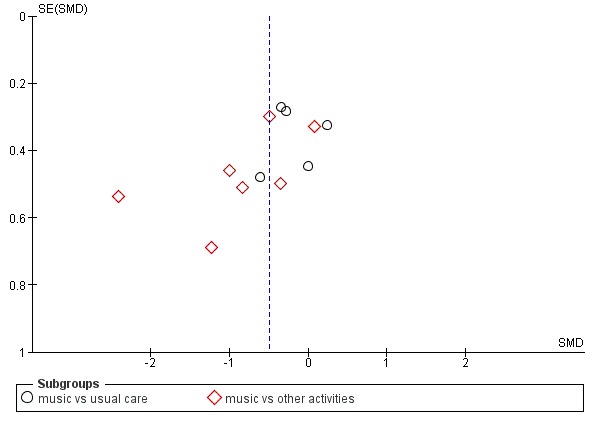

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, outcome: 1.3 Negative affect or mood disturbances: anxiety (11 studies, 12 dots because 1 study used 2 control groups, one with usual care and one with other activities)

Figure 5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, outcome: 1.4 Problematic behaviour: agitation or aggression (12 studies, 13 dots because 1 study used 2 control groups, one with usual care and one with other activities)

There were a number of possible biases and often we could not assess the risk of bias due to poor reporting. Only risk of attrition bias was either low or unclear, as often no or only few participants were lost to follow‐up and there were few missing outcome assessments. Risk of performance bias was high for all studies because participants and staff could not be blinded to the intervention. Regarding the other items, in more recent studies risk of bias was lower and the reporting in terms of interventions, rationale, chosen procedures, design and results was generally better. Still, we are unsure about the methodological quality of a number of studies because several items were rated as unclear.

Allocation

All included studies were RCTs. However, the randomization procedure was not always described in detail (Figure 2). Moreover, allocation concealment was described and adequate in detail in only three studies, all of which were published in 2010 or later (Cooke 2010; Lin 2011; Ridder 2013). One older study stated that participants were "non‐systematically separated" into groups without further detail, which we considered posed a high risk of selection bias (Lord 1993).

Blinding

Blinding of therapists and participants to the intervention is not possible. Therefore, the studies are at high risk of performance bias even though therapists do not generally assess outcomes and participants may not be aware or have no specific expectations or are unable to self‐report. The outcomes were assessed unblinded, by the research team or unblinded nurses, in at least four studies (Figure 2). For example, Narme and colleagues describe two studies differing in detection bias (Narme 2012‐study 1; Narme 2012‐study 1a). The first study involved a high risk of detection bias because the outcomes 'anxiety' (measured with the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory for adults, STAI‐A) and, as assessed from the first two minutes of filmed interviews, 'emotions' (from facial expressions) and 'social behaviour' (discourse content), were assessed by nurses who were not blinded for the interventions (music intervention or painting) (Narme 2012‐study 1). By contrast, in the second study (Narme 2012‐study 1a), risk of detection bias was low because the outcomes were assessed by five independent observers who were blinded for the type of intervention (music intervention or cooking). Risk of detection bias resulted in downgrading of the quality of the evidence for all end‐of‐treatment outcomes (to 'serious'; Table 1); and for all long‐term outcomes (to 'very serious' — all outcome assessment was unblinded; Table 2).

Incomplete outcome data

Self‐reported outcomes were rarely employed. Incomplete outcome data were not identified as problematic in any of the studies. Occasionally death, hospitalisation, acute illness, or no interest in the therapy occurred across the different study arms; and cases with no outcome data were not included in the analyses. Therefore, attrition bias was probably not highly prevalent, and probably did not affect the pooled estimates. Newer studies often visualized cases lost to follow‐up and missing outcome assessment in detail using flow diagrams. Nevertheless, in addition to the two oldest studies, some newer studies also only reported the number of cases randomized and analysed and did not explicitly report reasons for missing outcome data by study arm, or how these were handled.

Selective reporting

Most studies did not refer to initial plans, a study protocol or trial registration. Therefore, it is unclear to what extent bias due to selective outcome reporting is pertinent. We found some indication of inconsistent reporting of primary and secondary outcomes which, however, did not seem to affect the pooled estimate (Cooke 2010). Only one study clearly referred to a change in initial plans (Ceccato 2012); and one study referred to a trial registration, and outcome reporting was consistent with the registration (Sakamoto 2013). We did not downgrade the quality of the evidence because of unclear risk of selective reporting.

Regarding publication bias: funnel plots for outcomes with sufficient studies (anxiety, 11 studies of which one with both a 'usual care' and 'other activity' control group, Figure 4; and agitation or aggression, 12 studies, also one with two types of control groups, Figure 5) indicate possible publication bias for the anxiety outcome. For anxiety, the largest effects were found in studies with the largest standard error, and publications about studies with small effects and large standard error might be missing.

Other potential sources of bias

We found some potential other sources of bias. Outcome assessment may be either imprecise or biased by the use of non‐validated outcome measures with suboptimal distributions (such as skewed distributions, e.g. number of times yelling was observed; Clark 1998) and different procedures for the baseline and outcome assessment (Sakamoto 2013). Further, we found problems with the reporting of outcomes or we suspected errors (Lord 1993; and for this reason, Hong 2011 was moved to Studies awaiting classification). Implementation fidelity, including non‐adherence, was infrequently described, but Liesk 2015, the only study with null findings, reported on this in detail. Finally, there may be bias through a financial or intellectual conflict of interest when funding was provided by a source with a potential interest in the effectiveness of music therapy. This may apply to two studies (Ceccato 2012; Ridder 2013), but it should be noted that no source of funding was reported for more studies (Lord 1993; Clark 1998; Raglio 2010a; Raglio 2010b; Lin 2011; Liesk 2015). Only two studies were both definitely delivered by a music therapist and funded by a source unrelated to music or music therapy (no potential financial conflict of interest, but the music therapists (co)authored the article; Svansdottir 2006; Vink 2013). More studies did not report any funding source.

Effects of interventions

Results at the end of treatment are summarised in Table 1 and longer term effects in Table 2.

Of the 17 included studies, 16 studies with a total of 620 participants contributed to meta‐analyses of effects. One study reported data on emotional well‐being, social behaviour and cognition, but not in enough detail for us to include it in meta‐analyses (Lord 1993). Several authors provided additional data such as SDs or item‐level outcome data of scales for general behavioural assessments. We pooled data for all end‐of‐treatment outcomes, and for all but one long‐term outcome — cognition — because there was only one study. Of note: of the 17 studies, all but one study — Liesk 2015 — reported some significant improvement in outcomes of the music intervention versus control (all outcomes, including also, e.g. physiological outcomes that we did not evaluate). The methodological quality in terms of risk of bias, but also other quality considerations, varied substantially across the studies and the particular outcomes.

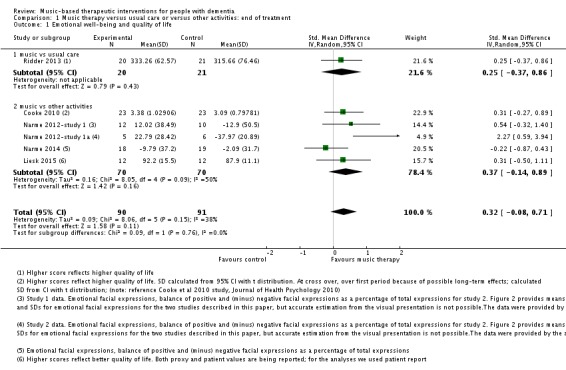

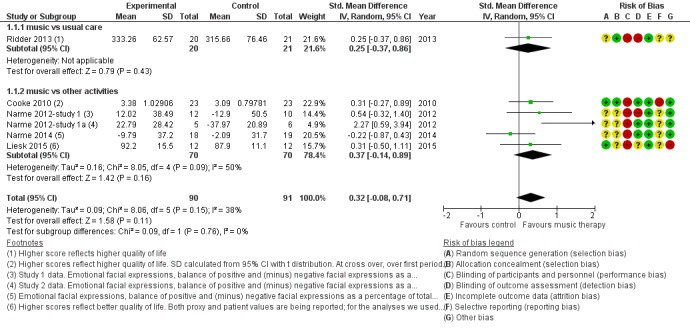

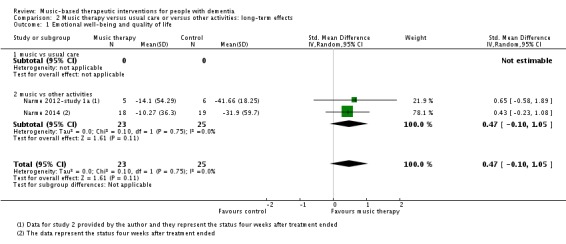

Emotional well‐being including quality of life

We included six studies with 181 participants in the analysis of end‐of‐treatment scores for the critically important outcome of emotional well‐being and quality of life. In half of the studies, a validated quality‐of‐life measure was used (the Dementia Quality of Life, DQOL (Cooke 2010), a German translation of the Dementia Quality of Life Instrument, DEMQOL (Liesk 2015), and a Danish translation of the Alzheimer’s Disease‐Related Quality of Life, ADRQL (Ridder 2013). In the three studies conducted by Narme and colleagues (Narme 2012‐study 1; Narme 2012‐study 1a; Narme 2014) emotional well‐being referred to counts of positive and negative facial expressions as assessed from the first two minutes of filmed interviews. There was no clear evidence of an effect at the end of treatment (Table 1; standardized mean difference, SMD 0.32, 95% CI −0.08 to 0.71; Analysis 1.1 and Figure 6). Heterogeneity was only low to moderate (I² = 38%; Chi² P = 0.15). There was no blinding of outcome assessment in two of the six studies. The overall quality for effects of music‐based interventions on emotional well‐being and quality of life at end of treatment was low, downgraded for serious risk of bias and imprecision (wide confidence interval). The quality was very low for long‐term outcomes for which there were only two very small studies and very serious imprecision (Narme 2012‐study 1a; Narme 2014). There was no clear evidence of an effect (SMD 0.47, 95% CI −0.10 to 1.05; Analysis 2.1; Table 2), but because of the very low quality, this is a very uncertain result.

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, Outcome 1 Emotional well‐being and quality of life.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, outcome: 1.1 Emotional well‐being and quality of life .

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: long‐term effects, Outcome 1 Emotional well‐being and quality of life.

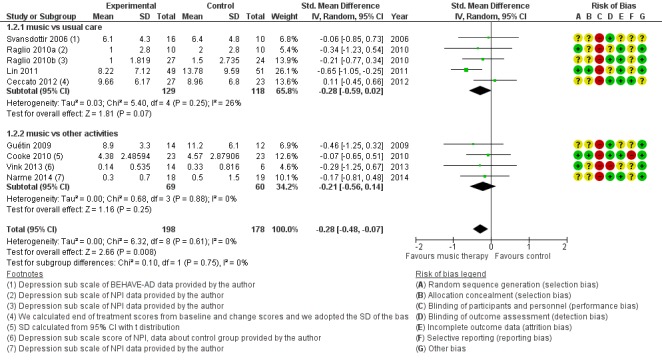

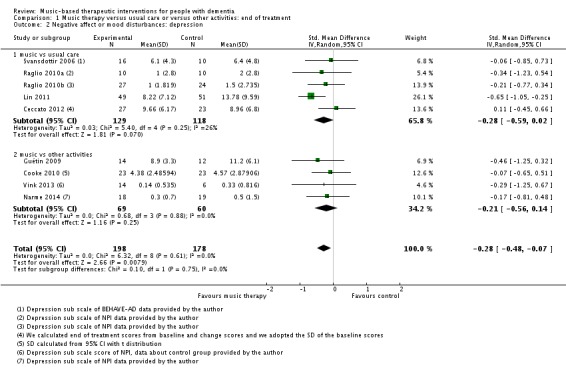

Mood disturbance or negative affect: depression

Nine studies contributed 376 participants to the analysis on end‐of‐treatment effect (Figure 7) and five studies contributed 234 participants to the analysis on long‐term effects. Depression or depressive symptoms were measured with (translated versions of) the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) or with a subscale of the Behavioural Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease (BEHAVE‐AD) or the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). Heterogeneity was not important (I² = 0%) for either end‐of‐treatment or long‐term outcomes. We downgraded both outcomes for risk of bias, due to lack of blinding in many studies. Imprecision was more of an issue for long‐term outcomes. The overall quality of the evidence was moderate for end‐of‐treatment effects and very low for long‐term outcomes. We found that music‐based therapeutic interventions probably reduced depressive symptoms at the end of treatment (SMD −0.28, 95% CI −0.48 to −0.07; Table 1; Analysis 1.2 and Figure 7). There was no evidence of a reduction in the longer term, with a smaller estimate and a confidence interval including no effect (SMD −0.01, 95% CI −0.27 to 0.24; Table 2; Analysis 2.2) although again the very low quality of the evidence made this result very uncertain.

Figure 7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, outcome: 1.2 Negative affect or mood disturbances: depression.

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, Outcome 2 Negative affect or mood disturbances: depression.

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: long‐term effects, Outcome 2 Negative affect or mood disturbances: depression.

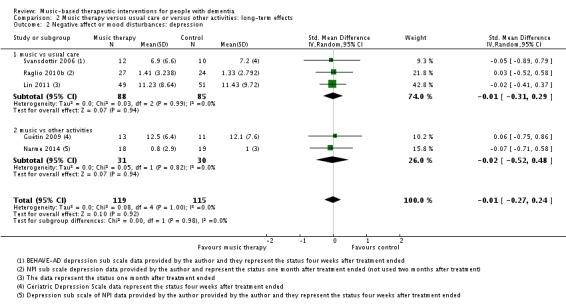

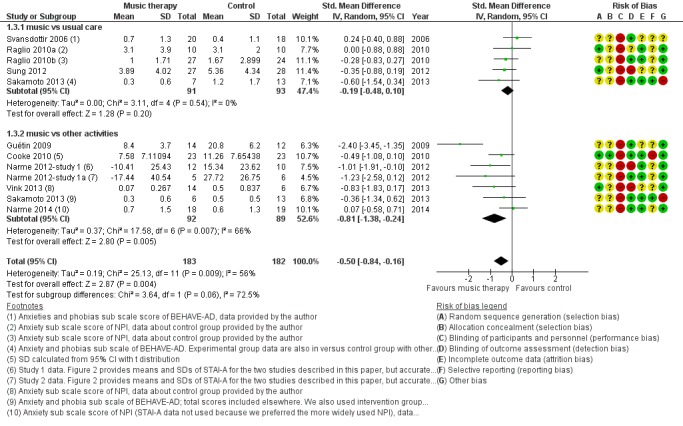

Mood disturbance or negative affect: anxiety

The other mood item we considered was anxiety. For this outcome, at the end of treatment, we included 11 studies with 365 participants. A variety of (translated) outcome measures were used; Rating Anxiety in Dementia Scale (RAID), State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults (STAI‐A), Hamilton Anxiety Scale, and subscale scores of the BEHAVE‐AD and NPI. Heterogeneity was substantial for end‐of‐treatment effects (I² = 56%; Chi² P = 0.009) and longer‐term effects (I² = 72%; Chi² P = 0.006). In addition to serious inconsistency, there was serious risk of bias, imprecision and — for the end of treatment outcome — possible publication bias (Figure 4). Hence we judged the quality of the evidence at both time points to be very low. We can therefore have very little confidence in the results. Anxiety was lower in the music intervention group at the end of treatment (SMD −0.50, 95% CI −0.84 to −0.16; 11 studies with 365 participants; Table 1; Analysis 1.3 and Figure 8), but not in the longer term (SMD −0.23, 95% CI −0.86 to 0.41; 5 studies with 160 participants; Table 2; Analysis 2.3).

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, Outcome 3 Negative affect or mood disturbances: anxiety.

Figure 8.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, outcome: 1.3 Negative affect or mood disturbances: anxiety.

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: long‐term effects, Outcome 3 Negative affect or mood disturbances: anxiety.

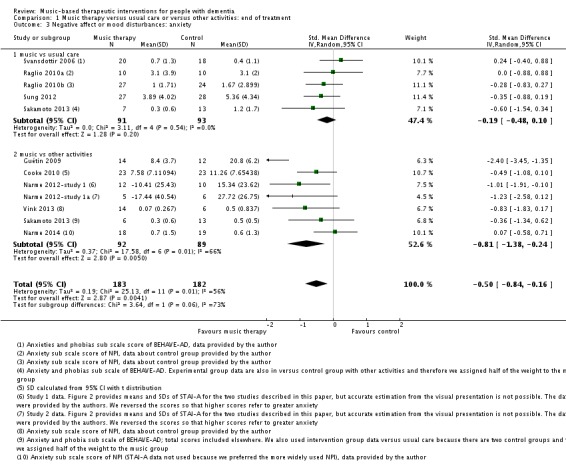

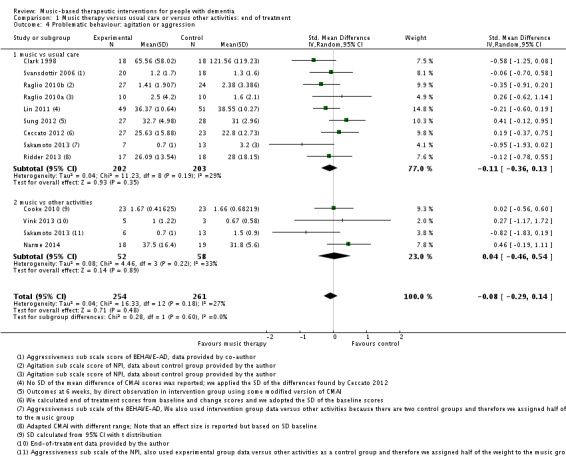

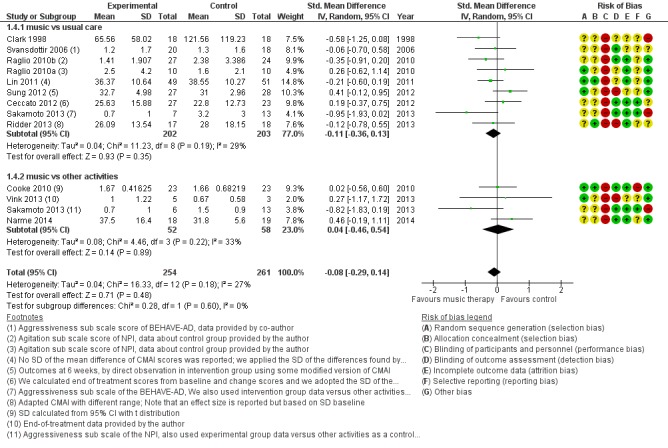

Behavioural problems: agitation or aggression

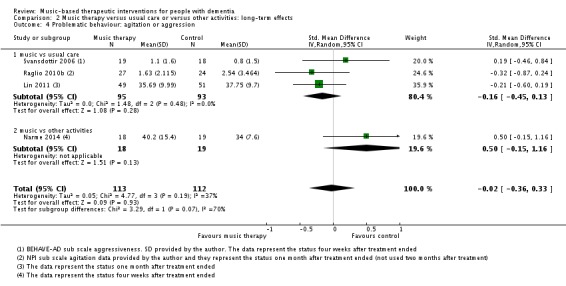

Twelve studies with 515 participants contributed to the end‐of‐treatment effect analysis, and four studies with 225 participants contributed to the long‐term effect analysis. Outcome measures used for agitation were (translated versions of) the Cohen‐Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) and the agitation subscale of the NPI; and for aggression, the aggressiveness subscale of the BEHAVE‐AD and counts of observed aggressive behaviour. Heterogeneity was low to moderate at end of treatment and longer term (I² = 27%, Chi² P = 0.18, and I² = 37%, Chi² P = 0.19, respectively). Inconsistency and imprecision were not serious for the end‐of‐treatment outcome, but inconsistency was serious for the long‐term outcome, as was imprecision. Both outcomes were downgraded for risk of bias. There was no evidence of publication bias (regarding end‐of‐treatment effect; Figure 5). We rated the quality of the evidence as moderate for the end‐of‐treatment outcome but very low for the long‐term outcome. We found no evidence of an effect on agitation or aggression at the end of treatment (SMD −0.08, 95% CI −0.29 to 0.14; Table 1; Analysis 1.4 and Figure 9) nor in the long term (SMD −0.02, 95% CI −0.36 to 0.33; ; Table 2; Analysis 2.4).

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, Outcome 4 Problematic behaviour: agitation or aggression.

Figure 9.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, outcome: 1.4 Problematic behaviour: agitation or aggression.

Analysis 2.4.

Comparison 2 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: long‐term effects, Outcome 4 Problematic behaviour: agitation or aggression.

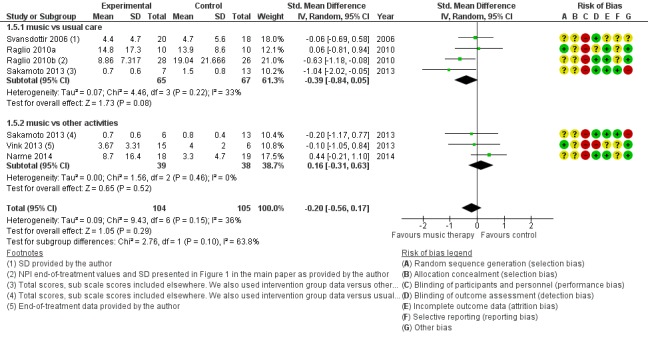

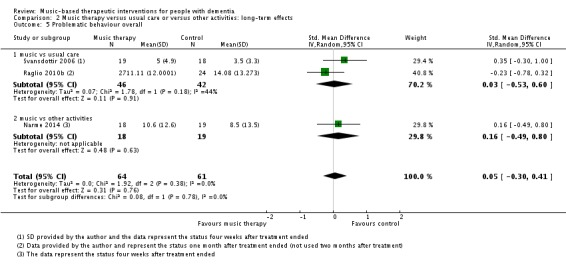

Behavioural problems overall

Six studies with 209 participants contributed to the end‐of‐treatment effect analysis, and three studies with 125 participants contributed to the analysis of longer term effects. Outcome measures were (translated versions of) the BEHAVE‐AD and NPI. Heterogeneity was low to moderate for the end of treatment effect (I² = 36%, Chi² P = 0.15). The quality of the evidence was low due to serious risk of bias and imprecision. We found no evidence of an effect of music‐based therapeutic interventions on problematic behaviour overall at the end of treatment (SMD −0.20, 95% CI −0.56 to 0.17; Table 1; Analysis 1.5 and Figure 10). There was no evidence of a long‐term effect either (SMD 0.05, 95% CI −0.30 to 0.41; I² = 0%, Chi² P = 0.38, heterogeneity was not important; Table 2; Analysis 2.5) although we considered this very low quality evidence.

Analysis 1.5.

Comparison 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, Outcome 5 Problematic behaviour overall.

Figure 10.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, outcome: 1.5 Problematic behaviour overall.

Analysis 2.5.

Comparison 2 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: long‐term effects, Outcome 5 Problematic behaviour overall.

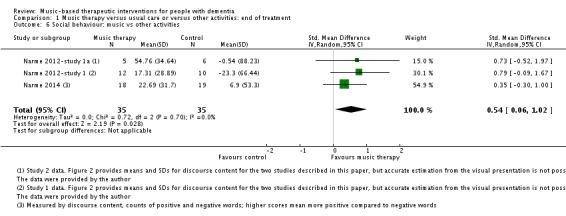

Social behaviour

The three studies of Narme and colleagues (Narme 2012‐study 1; Narme 2012‐study 1a; Narme 2014) contributed 70 participants to the end‐of‐treatment effect analysis and two of them contributed 48 participants to the analyses of longer term effects. For all, the outcome was the contents of conversation (positive versus negative expressions when interviewed about current feelings and personal history). Lord 1993 reported on effects on their self‐made questionnaire on social interaction, mood and recall (combined outcome) but there were no separate figures for social interaction and therefore we could not use the data for the meta‐analysis. We downgraded the evidence at both time points due to serious or very serious risk of bias and very serious imprecision. There was also moderate to substantial heterogeneity (I² = 54%, Chi² P = 0.14) in the long‐term analysis. We considered the quality of the evidence to be very low for both outcomes and were therefore very uncertain about the result of more positive expressions in the music‐based interventions group at the end of treatment (SMD 0.54, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.02; 3 studies; I² = 0%, Chi² P = 0.70; Table 1, Analysis 1.6 and Figure 11). There was a similar SMD but an even wider confidence interval in the analysis of long‐term effects (SMD 0.53, 95% CI −0.53 to 1.60; Analysis 2.6; Table 2).

Analysis 1.6.

Comparison 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, Outcome 6 Social behaviour: music vs other activities.

Figure 11.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, outcome: 1.6 Social behaviour: music vs other activities.

Analysis 2.6.

Comparison 2 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: long‐term effects, Outcome 6 Social behaviour.

Cognition

Six studies contributed 257 participants to the end‐of‐treatment effect analysis and there was only one study, with 100 participants, that assessed long‐term effects. Outcome measures used in the analyses were (translated versions of) the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Severe Impairment Battery (SIB). We used the MMSE data if these were available in addition to other cognition measures such as Prose Memory tests, the FAS‐Test (Controlled‐Oral‐Word‐Association Test), or the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale cognitive subscale (ADAS‐cog). The end‐of‐treatment results were imprecise but not inconsistent. There was no important heterogeneity (I² = 0%; Chi² P = 0.84). There was serious risk of bias. The overall quality of the evidence was low and suggested that music‐based interventions may not affect cognition at the end of treatment (SMD 0.21, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.45; Table 1; Analysis 1.7 and Figure 12). The only study that assessed long‐term effects found a SMD of 0.13 (95% CI −0.26 to 0.52); we considered this very low quality evidence.

Analysis 1.7.

Comparison 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, Outcome 7 Cognition.

Figure 12.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Music therapy versus usual care or versus other activities: end of treatment, outcome: 1.7 Cognition.

Any other adverse effects

These were not reported.

Effects of interventions delivered by a music therapist and in studies with a potential financial conflict of interest

The sensitivity analyses with analyses restricted to studies where the intervention was definitely or possibly delivered by a qualified music therapist resulted in similar end‐of‐treatment effect estimates (there was no sensitivity analysis for the social behaviour outcome because no study remained). When restricting to studies that were definitely delivered by a music therapist, most effects were similar, but there was a smaller effect on anxiety. In the four of 11 studies in which the intervention was definitely delivered by a music therapist, the estimate for anxiety was −0.15 (SMD −0.15, 95% CI −0.54 to 0.24; with less heterogeneity; I² = 16%, Chi² P = 0.31; 129 participants).

When we restricted analyses further to studies definitely delivered by a music therapist and having no potential financial conflict of interest, or no funding source reported, we found somewhat different estimates, but there were very small numbers of studies and participants in these analyses.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The aim of this review was to evaluate the effect of music‐based therapeutic interventions on a range of outcomes relevant for people with dementia. The specific focus was to assess whether they can improve emotional well‐being including quality of life, mood disturbance or negative affect, behavioural problems, social behaviour, and cognition.

Seventeen studies have been included in this review, and we were able to perform meta‐analyses on effects at the end of treatment and longer term (mostly four weeks after treatment ended). We found moderate‐quality evidence that at the end of treatment music‐based therapeutic interventions improved depressive symptoms and did not improve agitation or aggression, and low‐quality evidence that it had no effect on emotional well‐being including quality of life, overall behavioural problems and cognition. There was very low quality evidence of benefit on anxiety and social behaviour. Sensitivity analyses suggested that the effects were not larger in studies in which the intervention was delivered by a qualified music therapist. There was no evidence of effects four weeks or more after the end of treatment, but the quality of this evidence for all outcomes was also very low.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Only three studies used social behaviour as an outcome, and these were from a single group of researchers in France (Narme 2012‐study 1; Narme 2012‐study 1a; Narme 2014). The evidence in this review applies to therapeutic effects of music‐based therapeutic interventions after at least five sessions. It excludes some group interventions which involved music, but where music was not the main or only therapeutic element. It excludes direct effects during sessions.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was moderate for depression and for agitation or aggression at the end of treatment. For all other outcomes it was low or very low. All end‐of‐treatment outcomes were downgraded for risk of bias; all except depression and agitation or aggression were downgraded for imprecision; and some outcomes were also downgraded for inconsistency.

Many studies used validated outcome measures for behaviour (e.g. the NPI (Cummings 1994) or BEHAVE‐AD (Reisberg 1987)), two widely used measures which are recommended because of favourable psychometric properties (Jeon 2011), and for cognition (e.g. the MMSE (Folstein 1975)). We included subscales of the behavioural scales as outcome measures. However, there is less evidence for validity of subscales compared to total scores (Lai 2014). We combined agitation and aggression in meta‐analyses because this is consistent with the definition given by the International Psychogeriatric Association (Cummings 2015); and these items are also combined in the widely used CMAI (Cohen‐Mansfield 1986). Some have raised conceptual issues such as overlap of a broad definition of agitation with resistance to care (Volicer 2007).

The quality of the reporting was sometimes poor which resulted in uncertainty about the exact methodological quality of the included studies and the evidence for effects. Overall, the studies had small sample sizes. Few studies reported on fidelity of the implementation of the music intervention and other activities, or on other aspects of a process evaluation. Implementation fidelity is often defined as the degree to which an intervention or programme is delivered as intended (Carroll 2007); and in music therapy trial specifically, treatment fidelity refers to "methodological strategies used to monitor the delivery of the music therapy intervention as described in the treatment manual" (Bradt 2012). Treatment fidelity includes adherence to an intervention, exposure or dose, quality of delivery, participant responsiveness, and programme differentiation to identify essential components of the intervention (Carroll 2007), and therefore includes, but is not limited to, participant (or staff) adherence and responsiveness.

Some of the included studies selected people with agitated behaviour before the intervention, or people who were more likely to be interested in music‐based interventions. On the other hand, there were studies in which people with musical knowledge were excluded (Raglio 2010a), or without such selection criteria. Dropout was mostly due to health‐related conditions such as hospitalisation, illness or mortality. Dropout due to lack of interest was reported for a control activity (cognitive stimulation programme) and dropout due to "problems in the group" in a music intervention group (Liesk 2015), but none of the other studies reported any unfavourable effects of the music‐based interventions. We do not know if there were any unreported adverse effects such as a sore throat after singing. We also do not know if, without selectively including people based on subjective judgement of whether they will probably accept the intervention, some individuals with dementia might experience disadvantages of the intervention. Possibly, effects in these studies depend on participants having problems at baseline (being selected as in need of treatment for specific problems) and hence to there being substantial room for improvement. Specific subgroups might benefit from music‐based therapeutic interventions more than others.

There may be publication bias through selective reporting of studies and selective outcome reporting in the relevant literature. Although few protocols were registered, we found inconsistencies in the reporting of outcome measures in one study that reported on the study in multiple papers (Cooke 2010). Moreover, despite most of the meta‐analyses we ran not resulting in significant pooled effects, 16 of the 17 studies (all, except for Liesk 2015) reported at least one significant effect. For some studies this included outcomes beyond the scope of this review, such as heart rate, but it could indicate selective reporting of significant findings or analytic methods that resulted in significant findings. Further, the funnel plot showing end‐of‐treatment effects on anxiety suggested possible publication bias. There may also be a financial conflict of interest if the study is funded by a source interested in the outcomes, or an intellectual conflict of interest in case the study is performed by the music therapist who authors the article, but there were insufficient data to examine possible effects of conflicts of interest.

Potential biases in the review process

Although we have done an extensive literature search in the most commonly used databases and also thoroughly handsearched music therapy journals, it may however be that not all conducted RCTs were retrieved.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A recent review on effects of music therapy on behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia found larger SMDs for behavioural problems overall (−0.49, 95% CI −0.82 to −0.17) and for anxiety (−0.64, 95% CI −1.05 to −0.24) compared with our findings (Ueda 2013). However, that review included non‐randomized trials and cohort studies and studies which we excluded because they did not meet our criteria for therapeutic interventions. They found an even larger effect for studies that lasted three months or longer (−0.93, 95% CI −1.72 to −0.13), a subgroup we did not analyse separately.

The review by Chang 2015 included 10 studies, including Raglio 2008 which we excluded in the updated version of our review because after re‐evaluation, we judged this to be a quasi‐randomized study; Sung 2006 which after re‐evaluation did not meet our criteria for a music‐based therapeutic intervention (it was music with movement); and Janata 2012 which we excluded because streaming music also did not meet our criteria for a therapeutic intervention. Chang 2015 included studies that compared with usual care, excluding other activities except for reading sessions as the comparator (Guétin 2009; Cooke 2010; perhaps also including a study on ICU patients with no dementia). Our review had a longer search period than 2000 to 2014 and we included articles in French and German. Both we and Chang 2015 found substantial heterogeneity in our analyses of anxiety, but we also found that the funnel plot indicated possible publication bias and that the quality of the evidence for an effect on anxiety was very low. Effect sizes for cognition were smaller than for mood in both reviews. However, Chang 2015 found a significant effect on "disruptive behaviours" whereas we did not find evidence of an effect on behavioural problems (agitation/aggression), and we found an effect on depression which they did not, despite a larger effect size than in our review (−0.39 and −0.28, respectively).