Abstract

Background

Studies have reported high tumour response rates for platinum‐containing regimens in the treatment of women with metastatic breast cancer. Most of these studies were conducted prior to the 'intrinsic subtype' era, and did not specifically focus on metastatic triple‐negative breast cancers (mTNBCs).

Objectives

To identify and review the evidence from randomised trials comparing platinum‐containing chemotherapy regimens with regimens not containing platinum in the management of women with metastatic breast cancer.

Search methods

For this review update, we searched the Cochrane Breast Cancer Group's Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, the World Health Organization's International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov on 28 May 2015. We identified further potentially relevant studies from handsearching references of previous trials, systematic reviews, and meta‐analyses. Prior to this review update, the most recent search for studies was conducted in May 2003 for the original 2004 review.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials comparing platinum‐containing chemotherapy regimens with regimens not containing platinum in women with metastatic breast cancer.

Data collection and analysis

At least two independent reviewers assessed studies for eligibility and quality, and extracted all relevant data from each study. Hazard ratios (HRs) were derived for time‐to‐event outcomes, where possible, and fixed‐effect models were used for meta‐analyses. Objective tumour response rates (OTRRs) and toxicities were analysed as binary (dichotomous) outcomes with risk ratios (RRs) used as measures of effects. Quality of life data were extracted where available. GRADE was used to rate the quality of evidence for survival and tumour response outcomes at the level of subgroups selected and unselected for mTNBC, and for toxicity outcomes based on combining data from selected and unselected populations.

Main results

This update includes 15 new eligible treatment‐comparisons from 12 studies. In total, 28 treatment‐comparisons, involving 4418 women, from 24 studies are now included in one or more meta‐analyses. Of the 28 treatment‐comparisons, 19 and 16 had published or provided extractable time‐to‐event data on overall survival (OS) or progression‐free survival/time to progression (PFS/TTP), respectively. All 28 treatment‐comparisons provided OTRR data that could be included in meta‐analyses. Most women recruited to the studies were not selected on the basis of mTNBC status.

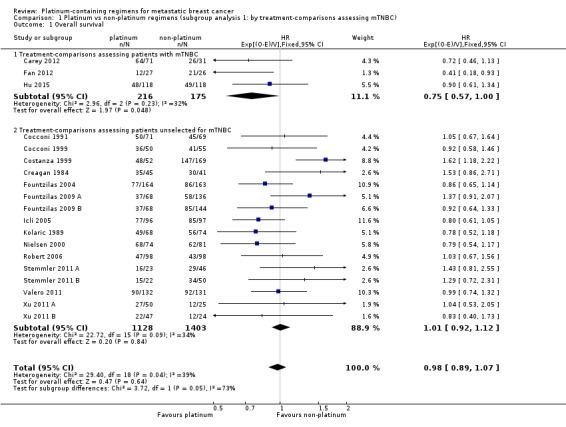

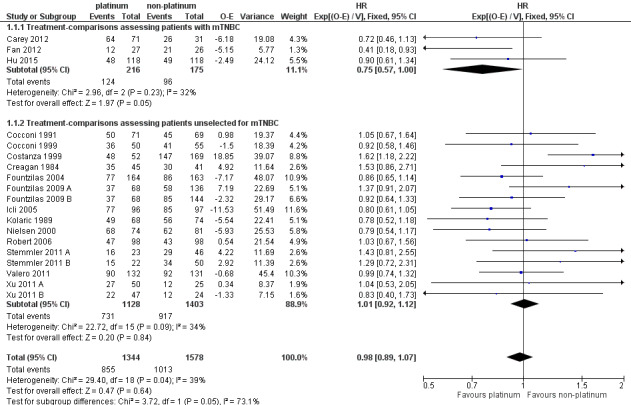

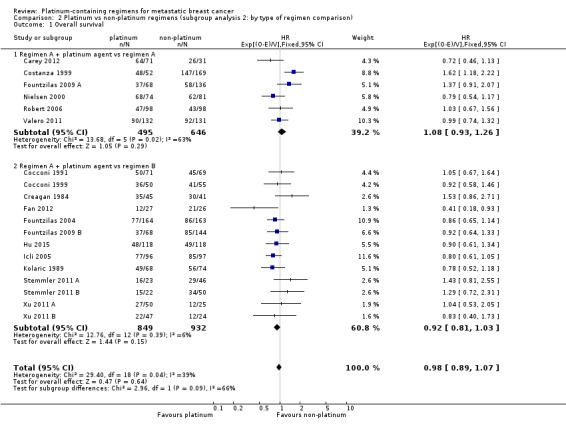

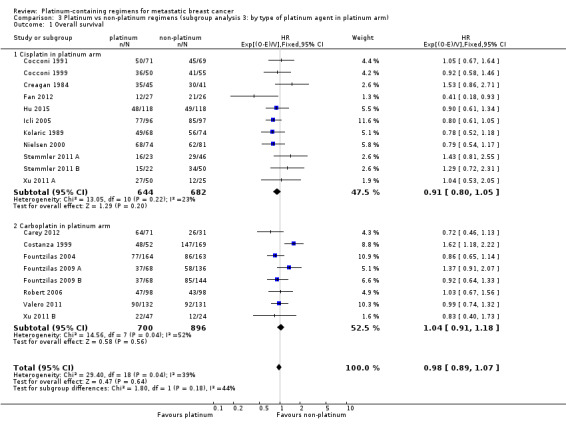

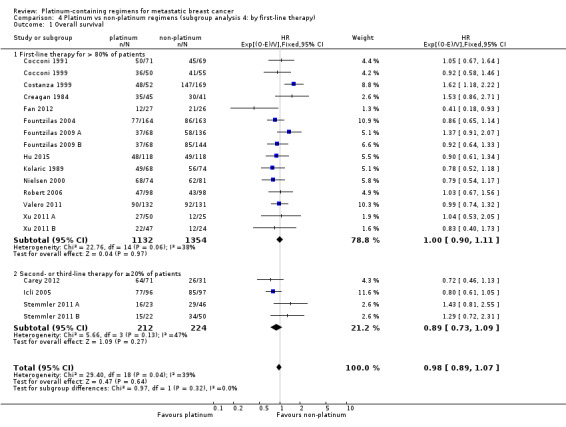

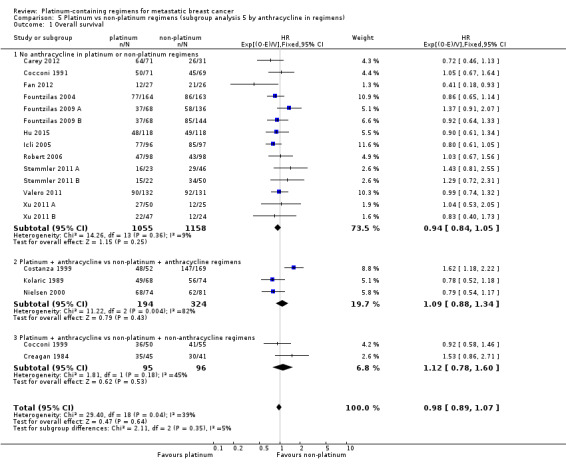

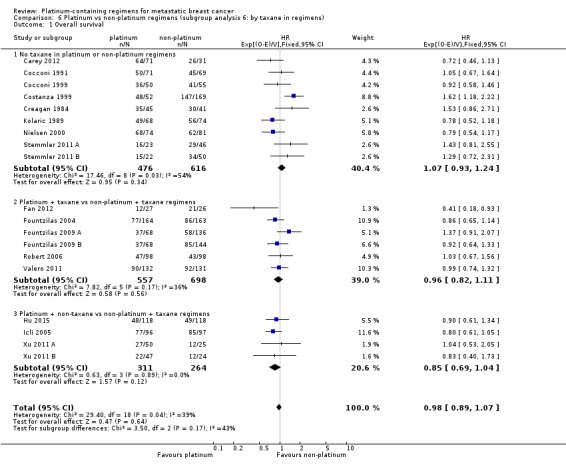

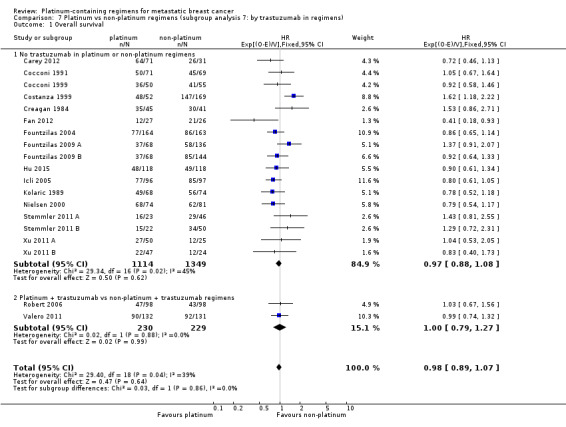

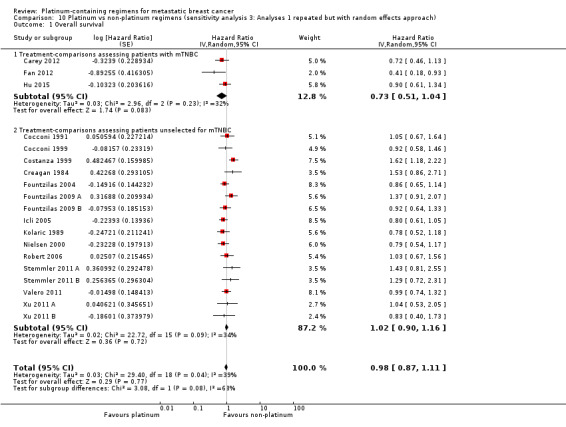

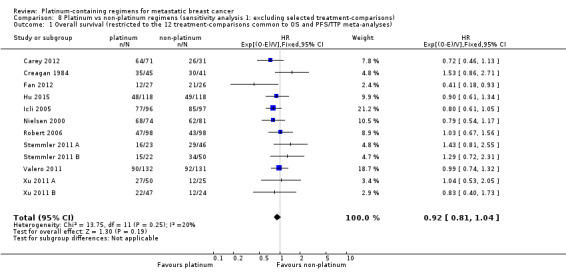

In a subgroup of three treatment‐comparisons assessing women with mTNBC, platinum‐containing regimens may have provided a survival benefit (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.00; low‐quality evidence). In women unselected for intrinsic subtypes such as mTNBC, there was little or no effect on survival (HR 1.01, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.12; high‐quality evidence). This effect was similar to the combined analysis of survival data for both populations (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.07; I2 =39%, 1868 deaths, 2922 women; 19 trials). The difference in treatment effects between mTNBC women compared with unselected women was of borderline statistical significance (P = 0.05).

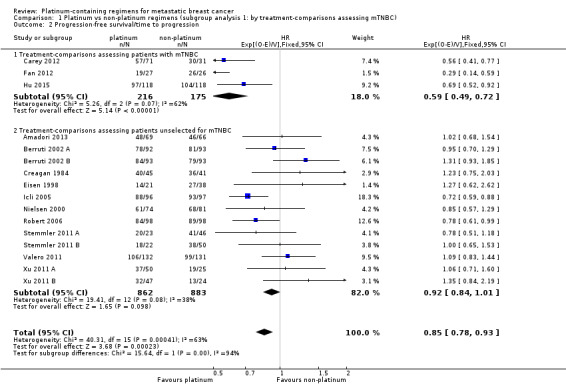

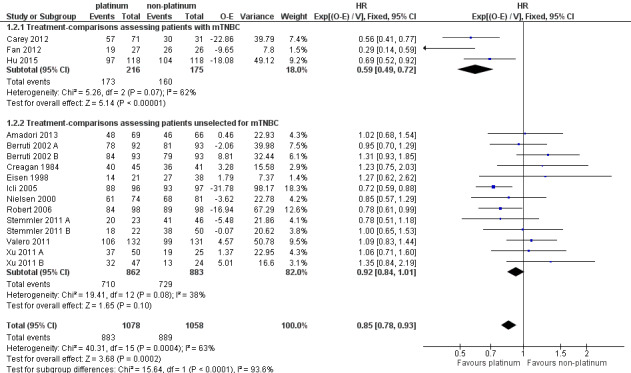

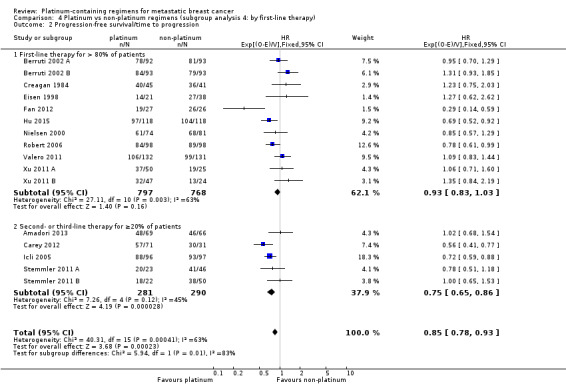

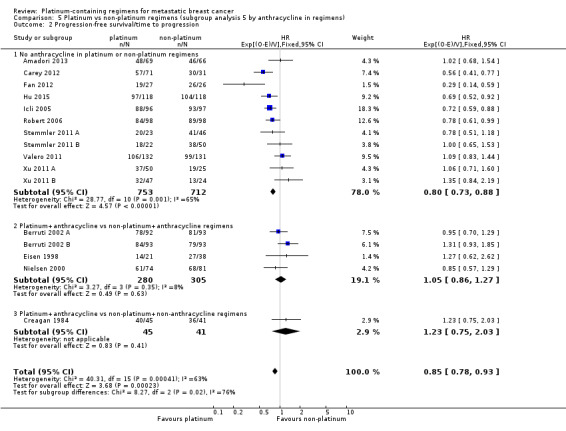

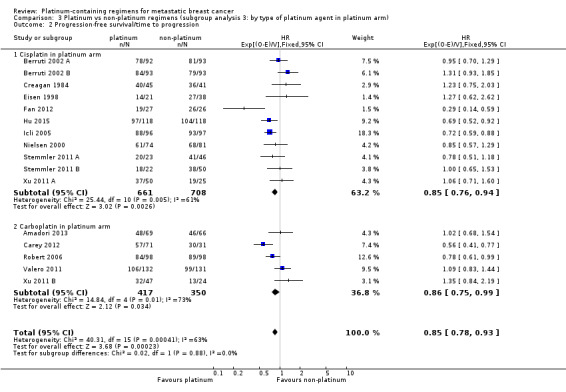

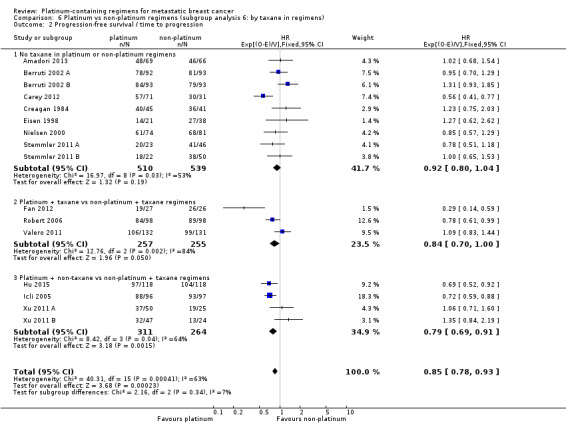

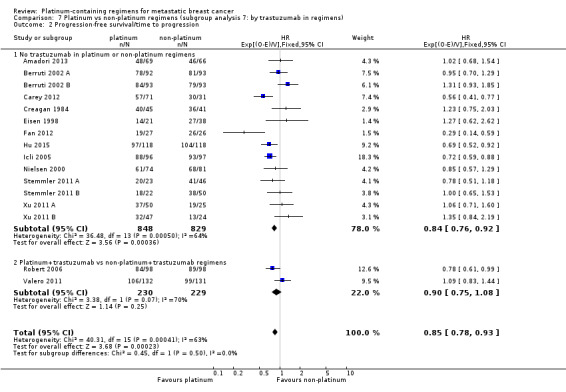

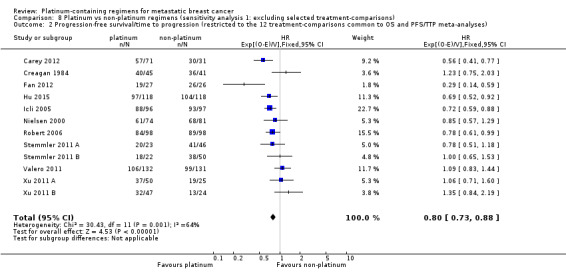

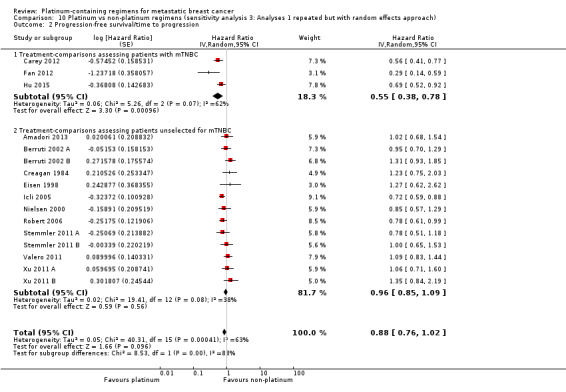

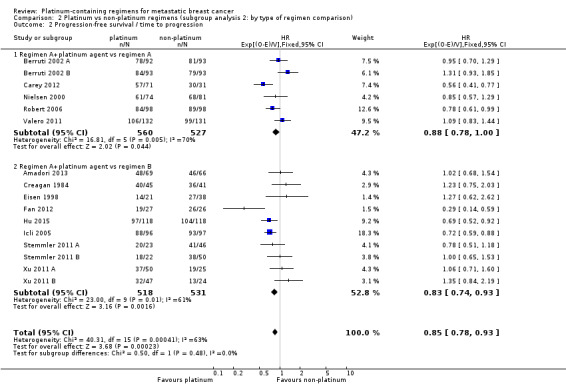

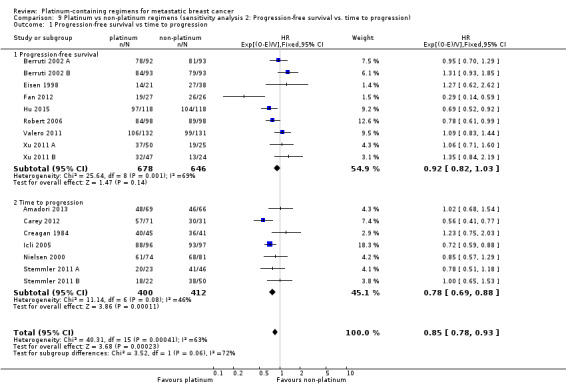

Data from three treatment‐comparisons with mTNBC participants showed that platinum regimens may improve PFS/TTP (HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.72; low‐quality evidence). Thirteen treatment‐comparisons of unselected metastatic participants showed that there was probably a small PFS/TTP benefit for platinum recipients, although the confidence interval included no difference (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.01; moderate‐quality evidence). Combined analysis of data from an estimated 1772 women who progressed or died out of 2136 women selected or unselected for mTNBC indicated that platinum‐containing regimens improved PFS/TTP (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.93). There was marked evidence of heterogeneity (P = 0.0004; I2 = 63%). The larger treatment benefit in mTNBC women compared with unselected women was statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

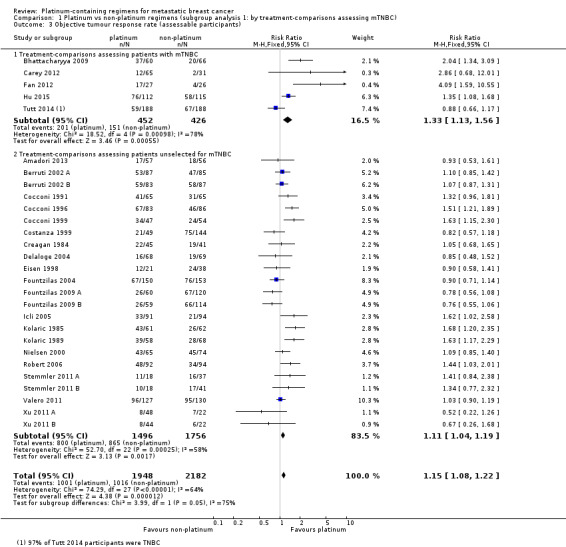

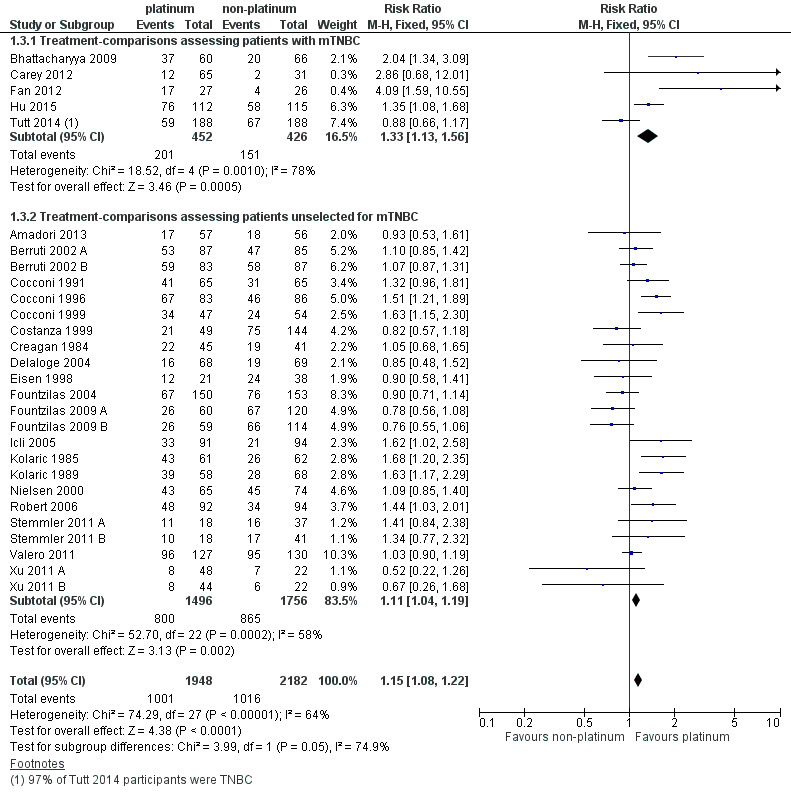

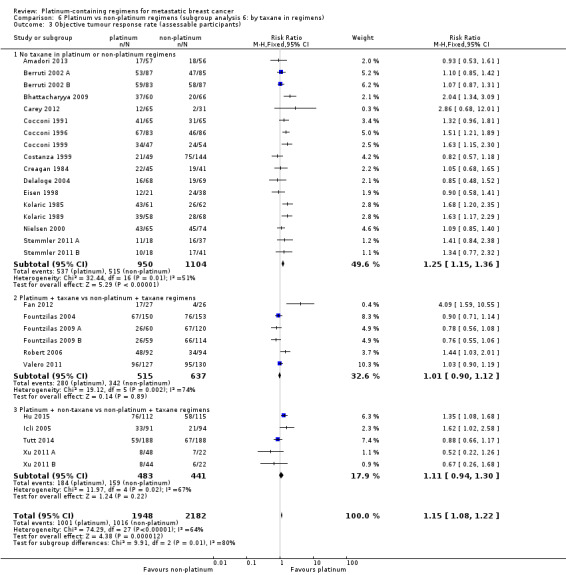

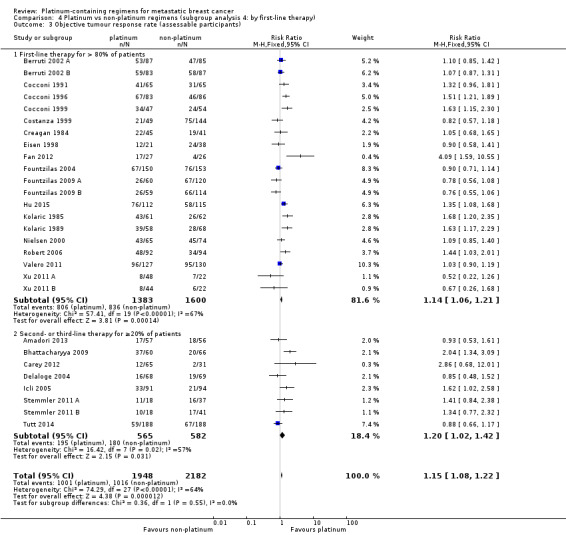

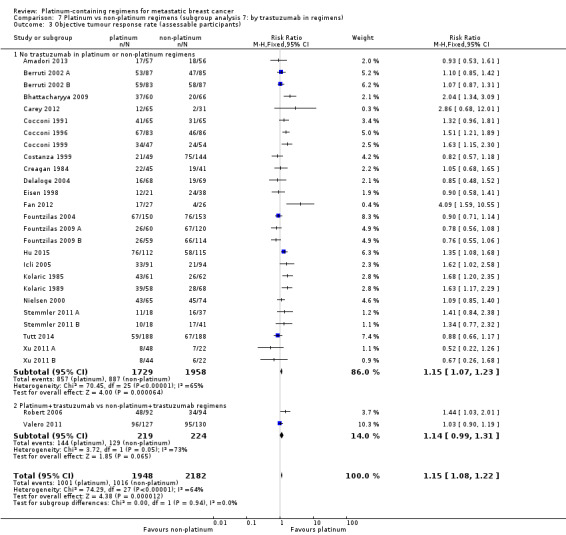

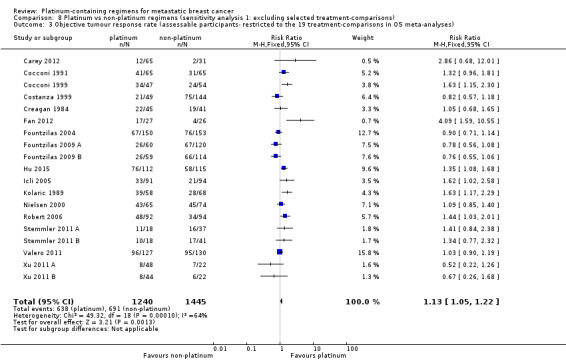

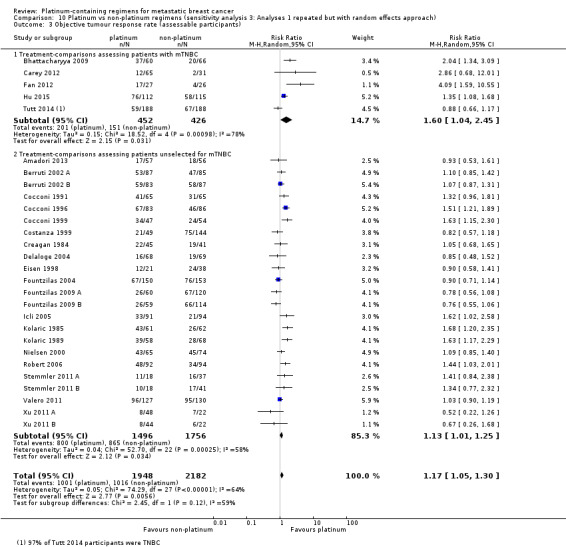

There was low‐quality evidence of better tumour response in both subgroups of women with mTNBC and unselected women (RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.56; RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.19, respectively). Combined analysis of both populations was closer to the effect in unselected women (RR 1.15, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.22; 4130 women). There was considerable evidence of heterogeneity (P < 0.0001; I2 = 64%), which may reflect between‐study differences and general difficulties in assessing response, as well as the varying potencies of the comparators.

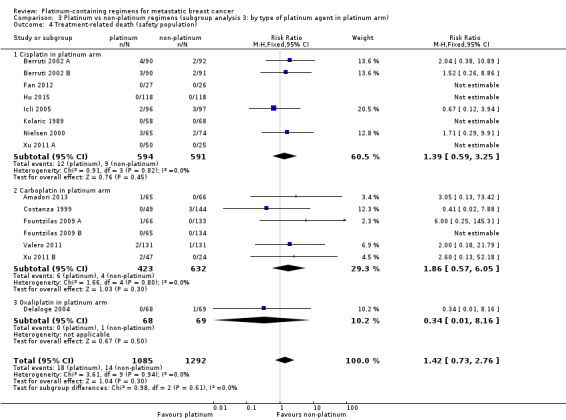

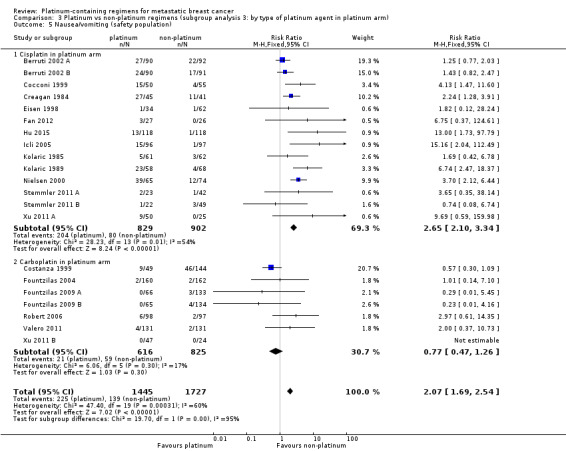

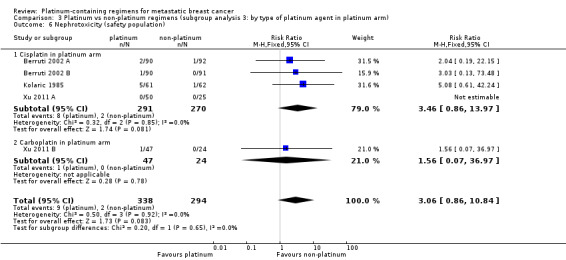

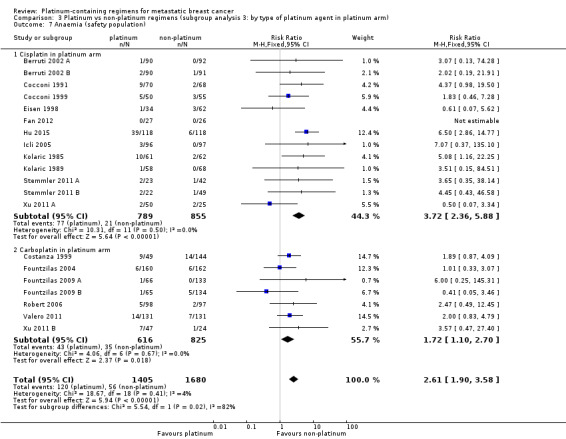

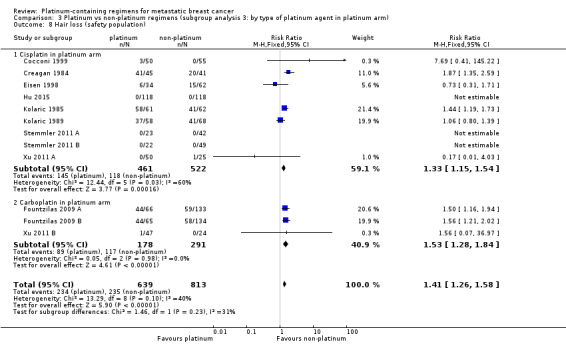

Compared with women receiving non‐platinum regimens: rates of grade 3 and 4 nausea/vomiting were probably higher among women receiving cisplatin‐ (RR 2.65, 95% CI 2.10 to 3.34; 1731 women; moderate‐quality evidence) but the effect from carboplatin‐containing regimens was less certain (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.26; 1441 women; moderate‐quality evidence); rates of grade 3 and 4 anaemia were higher among women receiving cisplatin‐ (RR 3.72, 95% CI 2.36 to 5.88; 1644 women; high‐quality evidence) and carboplatin‐containing regimens (RR 1.72, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.70; 1441 women; high‐quality evidence); rates of grade 3 and 4 hair loss (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.26 to 1.58; 1452 women; high‐quality evidence) and leukopenia (RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.57; 3176 women; moderate‐quality evidence) were higher among women receiving platinum‐containing regimens (regardless of platinum agent).

Authors' conclusions

In women with metastatic breast cancer who do not have triple‐negative disease, there is high‐quality evidence of little or no survival benefit and excess toxicity from platinum‐based regimens. There is preliminary low‐quality evidence of a moderate survival benefit from platinum‐based regimens for women with mTNBC. Further randomised trials of platinum‐based regimens in this subpopulation of women with metastatic breast cancer are required.

Plain language summary

Platinum‐containing regimens for metastatic breast cancer

What is the issue? Metastatic breast cancer occurs when the cancer has spread to areas of the body beyond the breast and nearby lymph nodes. Although metastatic breast cancer is generally not curable, it is widely accepted that women with metastatic disease should receive some form of chemotherapy to help ease the severity of disease symptoms, while hopefully extending survival time. Chemotherapy containing platinum is known to be effective for treating a number of cancer types including lung, testicular, head and neck, bladder and ovarian cancers, but it also known to cause more adverse effects (such as nausea and vomiting, hair loss, anaemia, kidney damage and leukopenia (low white blood cells)) than other chemotherapy options. The two platinum agents most commonly used for treating metastatic breast cancer are carboplatin and cisplatin.

The original version of this review (2004) concluded that chemotherapy containing platinum did not increase survival time for women treated for metastatic breast cancer. Since then, however, researchers have discovered that there are a variety of subtypes of breast cancer which may respond differently to different types of chemotherapy. One of these subtypes — triple‐negative breast cancer (TNBC) — makes up approximately 12 to 17% of breast cancers and is associated with shorter survival and higher likelihood that the cancer returns. Some researchers have speculated that chemotherapy containing platinum might be more effective in treating metastatic TNBC (mTNBC) than other chemotherapy options.

Why does it matter? There are at least two reasons why it is important to update the evidence on this topic. First, it is important to assess whether our 2004 conclusions — based on 12 early studies — are representative of the 24 studies who have now published or provided results through to 2015. Second, it is important to assess whether chemotherapy containing platinum increases survival for women with mTNBC more than other chemotherapy options.

We asked whether chemotherapy treatments containing a platinum agent are more or less effective for treating women with metastatic breast cancer than chemotherapy treatments not containing a platinum agent. We also asked the same question, but with a focus on women with mTNBC.

We found 24 studies involving 4418 women. The evidence is current to May 2015. Five of the 24 studies specifically assessed women with mTNBC while the other 19 studies assessed women with metastatic breast cancer in general (mainly women without mTNBC). This review found that, compared to chemotherapy without platinum, chemotherapy with platinum did not increase survival time by any important degree for women with metastatic breast cancer in general (mainly women without mTNBC). The quality of the evidence for this was considered to be high, meaning that we are confident about the results. For women with mTNBC, however, this review found that chemotherapy containing platinum may increase survival time over chemotherapy without platinum, but the quality of the evidence for this is low at this point in time (largely due to the small number of studies that have assessed mTNBC). This review also found that chemotherapy including platinum reduced the number of breast cancer recurrences compared to chemotherapy that did not contain platinum in women with mTNBC, however these findings also currently come from low‐quality evidence. There was no difference in the number of breast cancer recurrences for women receiving platinum or non‐platinum chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer in general. Chemotherapy with platinum was more likely to shrink tumours compared to chemotherapy without platinum, but this result needs to be considered cautiously.

Compared with women receiving chemotherapy without platinum, women receiving chemotherapy with platinum experienced higher rates of nausea/vomiting, anaemia, leukopenia and hair loss.

This means it is difficult to justify using chemotherapy containing platinum for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer that is not mTNBC, given that similarly effective but less toxic chemotherapy is commonly available. Chemotherapy containing platinum may provide a survival benefit to mTNBC participants of sufficient magnitude to justify its use, but the quality of the evidence for this is low at this point in time. Further studies are required before a more definitive conclusion can be made.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Platinum‐containing regimens for women with metastatic breast cancer unselected for triple‐negative disease.

| Platinum compared to non‐platinum chemotherapy regimens for women with metastatic breast cancer unselected for triple‐negative disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with metastatic breast cancer unselected for triple‐negative breast cancer (TNBC) Setting: hospital Intervention: platinum Comparison: non‐platinum chemotherapy regimens | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (treatment‐ comparisons) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐platinum chemotherapy regimens | Risk with platinum | |||||

| Overall survival ‐ trials of metastatic breast cancer participants unselected for TNBC | 1‐year risk of death | HR 1.01 (0.92 to 1.12) | 2531 (16) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH3 | Heterogeneity: P = 0.09, I2=34% | |

| 310 per 1,000 1 | 313 per 1,000 (289 to 340)2 | |||||

| 2‐year risk of death | ||||||

| 540 per 1,000 1 | 543 per 1,000 (510 to 581)2 | |||||

| Progression‐free survival/time to progression (randomised participants) ‐ trials of metastatic breast cancer participants unselected for TNBC | 1‐year risk of progression or death | HR 0.92 (0.84 to 1.01) | 1745 (13) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE4 | Heterogeneity: P = 0.08, I2=38% | |

| 737 per 1,000 1 | 707 per 1,000 (674 to 740)2 | |||||

| 2‐year risk of progression or death | ||||||

| 891 per 1,000 1 | 869 per 1,000 (844 to 893)2 | |||||

| Objective tumour response rate (assessable participants) ‐ trials of metastatic breast cancer participants unselected for TNBC | 493 per 1,000 5 | 547 per 1,000 (512 to 586) | RR 1.11 (1.04 to 1.19) | 3252 (23) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW4,6 | Heterogeneity: P = 0.0002, I2=58% |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Estimated from the average of non‐platinum group Kaplan‐Meier probabilities from the three highest weighted non‐TNBC treatment‐comparisons for this outcome

2 Estimated as 1000*(1‐S(t)HR) where S(t) is the estimated probability of survival for non‐platinum participants and HR is the pooled hazard ratio (Davies 1998)

3 Quality of evidence for OS was not downgraded for blinding because this outcome is unlikely to be affected by non‐blinding.

4 Downgraded quality of evidence one level for 'indirectness' because this outcome is a surrogate endpoint of questionable validity for assessing the more important outcome of OS in the context of metastatic breast cancer (Burzykowski 2008)

5 Estimated from all 23 non‐TNBC treatment‐comparisons in the review

6 Downgraded quality of evidence one level for 'inconsistency' because there was substantial evidence of heterogeneity across studies (P < 0.05)

Summary of findings 2. Platinum‐containing regimens for women with metastatic triple‐negative breast cancer.

| Platinum compared to non‐platinum chemotherapy regimens for women with metastatic triple‐negative breast cancer | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with metastatic triple‐negative breast cancer (mTNBC) Setting: hospital Intervention: platinum Comparison: non‐platinum chemotherapy regimens | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (treatment‐ comparisons) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐platinum chemotherapy regimens | Risk with platinum | |||||

| Overall survival ‐ trials of mTNBC participants | 1‐year risk of death | HR 0.75 (0.57 to 1.00) | 391 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW3,4,5 | Heterogeneity: P = 0.23, I2 = 32% | |

| 485 per 1,000 1 | 392 per 1,000 (315 to 485)2 | |||||

| 2‐year risk of death | ||||||

| 655 per 1,000 1 | 550 per 1,000 (455 to 655)2 | |||||

| Progression‐free survival/time to progression (randomised participants) ‐ trials of mTNBC participants | 1‐year risk of death | HR 0.59 (0.49 to 0.72) | 391 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW4,6 | Heterogeneity: P = 0.07, I2 = 67% | |

| 894 per 1,000 1 | 733 per 1,000 (667 to 801)2 | |||||

| 2‐year risk of death | ||||||

| 987 per 1,000 1 | 922 per 1,000 (879 to 955)2 | |||||

| Objective tumour response rate (assessable participants) ‐ trials of mTNBC participants | 354 per 1,0007 | 470 per 1,000 (400 to 552) | RR 1.33 (1.13 to 1.56) | 878 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW6,8 | Heterogeneity: P = 0.0010, I2 = 78% |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Estimated from the average of non‐platinum group Kaplan‐Meier probabilities from the three TNBC treatment‐comparisons contributing data for pooling on this outcome

2 Estimated as 1000*(1‐S(t)HR) where S(t) is the estimated probability of survival for non‐platinum participants and HR is the pooled hazard ratio (Davies 1998)

3 Downgraded quality of evidence one level for 'imprecision' because the confidence interval for the pooled estimate is wide and crosses or nearly crosses unity

4 Downgraded quality of evidence one level for 'suspected publication bias' because Tutt 2014 is a large study with 376 participants but has so far only reported median OS/PFS times. As a consequence, the study did not contribute to the pooled HR estimates for OS or PFS/TTP. The reported median OS/PFS times in Tutt 2014 were similar between platinum and non‐platinum regimens. Hence, it seems likely that if HRs from Tutt 2014 were able to be included in pooled HR estimates, these pooled estimates would be considerably closer to the null.

5 Quality of evidence for OS was not downgraded for blinding because this outcome is unlikely to be affected by non‐blinding.

6 Downgraded quality of evidence one level for 'indirectness' because this outcome is a surrogate endpoint of questionable validity for assessing the more important outcome of OS in the context of metastatic breast cancer (Burzykowski 2008)

7Estimated from all five TNBC treatment‐comparisons in the review

8 Downgraded quality of evidence one level for 'inconsistency' because there was substantial evidence of heterogeneity across studies (P < 0.05)

Summary of findings 3. Platinum‐containing regimens and toxicity profile.

| Platinum compared to non‐platinum chemotherapy regimens for nausea/vomiting, anaemia, hair loss and leukopenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with metastatic breast cancer Setting: hospital Intervention: platinum Comparison: non‐platinum chemotherapy regimens | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (treatment‐ comparisons) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐platinum chemotherapy regimens | Risk with platinum | |||||

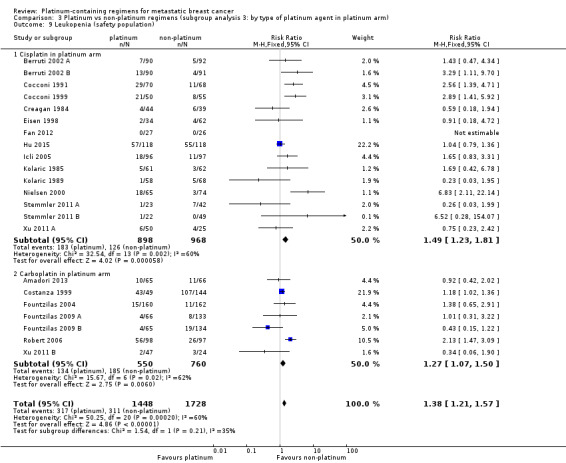

| Nausea/vomiting* grade 3 or 4 (safety population) by type of platinum agent in platinum regimen | Carboplatin | (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.26) | 1441 (7) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE2 | Test for carboplatin/cisplatin subgroup difference: P < 0.0001 Heterogeneity among carboplatin studies: P = 0.30, I2 = 17% Heterogeneity among cisplatin studies: P = 0.010, I2 = 32% |

|

| 80 per 1,000 1 | 62 per 1,000 (59 to 101) | |||||

| Cisplatin | (RR 2.65, 95% CI 2.10 to 3.34) | 1747 (14) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE3 | |||

| 80 per 1,000 1 | 210 per 1,000 (167 to 266) | |||||

| Anaemia grade 3 or 4 (safety population) by type of platinum agent in platinum regimen | Carboplatin | (RR 1.72, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.70) | 1441 (7) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Test for carboplatin/cisplatin subgroup difference: P = 0.02 Heterogeneity among carboplatin studies: P = 0.67, I2 = 0% Heterogeneity among cisplatin studies: P = 0.50, I2 = 0% |

|

| 33 per 1,000 1 | 57 per 1,000 (36 to 89) | |||||

| Cisplatin | (RR 3.72, 95% CI 2.36 to 5.88) | 1644 (13) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

|||

| 33 per 1,000 1 | 123 per 1,000 (78 to 194) | |||||

| Hair loss grade 3 or 4 (safety population) | Carboplatin or cisplatin | (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.26 to 1.58) | 1452 (13) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Test for carboplatin/cisplatin subgroup difference: P = 0.23 Heterogeneity: P = 0.10, I2 = 40% |

|

| 264 per 1,000 1 | 372 per 1,000 (333 to 417) | |||||

| Leukopenia** grade 3 or 4 (safety population) | Carboplatin or cisplatin | (RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.57) | 3176 (22) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE3 | Test for carboplatin/cisplatin subgroup difference: P = 0.22 Heterogeneity: P = 0.0002, I2 = 60% |

|

| 179 per 1,000 1 | 247 per 1,000 (217 to 281) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Estimated from all treatment‐comparisons (cisplatin and carboplatin) contributing data for pooling for this outcome

2 Downgraded quality of evidence one level for 'imprecision' because the confidence interval for the pooled estimate is wide and does not rule out 'no effect'

3 Downgraded quality of evidence one level for 'inconsistency' because there was substantial evidence of heterogeneity across studies (P < 0.05)

*data on vomiting was included if data on nausea/vomiting was reported separately

**data on neutropenia was included if data on leukopenia was not reported

Background

Description of the condition

Breast cancer is both the most common type of cancer in women and the most common cause of cancer death in women (Ferlay 2013). In 2012, there was an estimated 1.67 million estimated new cases and approximately 522,000 deaths from breast cancer worldwide, with an age standardised death rate (ASR) of 12.9 per 100,000 (Ferlay 2013). ASRs of 25 or greater were recorded that same year in Fiji (28.4), Bahamas (26.3), Nigeria (25.9), Former Yugoslav Republic (FYR) Macedonia (25.5) and Pakistan (25.2) (Ferlay 2013).

The stage of breast cancer at the time of diagnosis is an important indicator of prognosis. Once breast cancer becomes metastatic, it is not generally considered curable and most women with metastatic disease do not survive beyond five years from the time of their metastatic diagnosis (Clements 2012). Another important predictor of prognosis is the biological subtype of breast cancer. One of these subtypes — triple‐negative breast cancer (TNBC) — is characterised by a lack of expression of oestrogen and progesterone receptors (ER and PgR) and human epidermal receptor 2 (HER2). TNBC comprises approximately 12 to 17% of breast cancers and is associated with shorter survival and higher likelihood of recurrence (Foulkes 2010). The median survival time for women diagnosed with metastatic TNBC (mTNBC) is about one year from their metastatic diagnosis (Kassam 2009).

Although there is no evidence from randomised trials comparing chemotherapy with observation (no chemotherapy) in women with metastatic breast cancer, it is widely accepted that women with metastatic disease should receive some form of systemic therapy at some time during the course of their metastatic disease. Chemotherapy is considered by many to be the appropriate first treatment option for women with multiple sites of recurrence or where visceral disease is not easily treated by local modalities (Hayes 1995; Beslija 2009). Chemotherapy is also considered to be useful in women whose cancer is hormone refractory or is expected to be hormone resistant (Hortobagyi 1996).

Description of the intervention

Platinum compound, an alkylating agent, has been known to be active in metastatic breast cancer since clinical trials in the 1970s. However, it is more toxic and difficult to administer than other chemotherapy agents. The three most widely used platinum agents for treating breast cancer are cisplatin, carboplatin (both divalent complexes) and oxaliplatin (a tetravalent complex) (Sikov 2015). Cisplatin and carboplatin have demonstrated benefits in treating a number of cancer types including lung, testicular, head and neck, bladder and ovarian cancers. Oxaliplatin is often used to treat cisplatin‐ and carboplatin‐resistant tumours because it is commonly believed that cross‐resistance between oxaliplatin and cisplatin or carboplatin is incomplete (Mani 2002). More recent evidence suggests that the benefits of oxaliplatin may be due to its low toxicity and ability to be combined with other drugs rather than incomplete cross‐resistance with other platinum agents (Stordal 2007).

The use of oxaliplatin for treating breast cancers is much less common than the use of cisplatin or carboplatin, both in normal clinical practice and as an intervention in clinical trials (Sikov 2015). Cisplatin and carboplatin have been used and studied extensively as first‐line metastatic therapy in combination with other older pharmacological agents including 5‐fluorouracil and etoposide, and more recently with doxorubicin, epirubicin, vinorelbine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and gemcitabine. The potential benefits of cisplatin or carboplatin as monotherapy for metastatic breast cancer, rather than as combination therapy, are rarely studied in clinical trials.

Although platinum agents have been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of a number of cancer types, their use is often associated with a variety of side effects. The known side effects of platinum agents include nausea, vomiting, myelosuppression (thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, neutropenia and anaemia), peripheral neuropathy (symptoms include tingling in fingers and toes), nephrotoxicity, ototoxicities (hearing loss and tinnitus), hypomagnesaemia and anaphylaxis. Carboplatin is reported to be more tolerable than cisplatin with less nausea and vomiting, nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity and neurotoxicity, but worse myelosuppression, especially thrombocytopenia (Sikov 2015).

How the intervention might work

The exact mechanism of action of platinum agents is not known but deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) adducts are formed (Sikov 2015). These complexes are believed to inhibit DNA synthesis, replication and transcription by forming interstrand and intrastrand cross‐linking of DNA molecules. Interstrand cross‐links that remain intact can produce cell death, and it is this cytotoxic effect, when successful, that forms the mechanistic basis of action for cancer cell death by platinum agents (Noll 2006). For TNBC, it has been additionally hypothesised that a dysfunctional BRCA1 pathway in some TNBCs may make them more sensitive to platinum agents that selectively target cells deficient in homologous recombination DNA repair (Foulkes 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

There are a number of reasons for updating this review. First, this review was originally published in 2004 (Carrick 2004) and was based on 12 studies (13 treatment‐comparisons) identified from a May 2003 search of the literature. Although there have since been some updates to this review containing minor amendments, no new searches for relevant studies have been conducted since 2003. In the current review update, the number of included studies has increased from 12 in the original version of this review to 24 (28 treatment‐comparisons). This allows effects to be estimated with greater precision than before and provides an opportunity to conduct new subgroup analyses corresponding to emerging evidence and new hypotheses. Second, all 12 studies included in the original version of this review were conducted prior to the 'intrinsic subtype' era and thus did not specifically focus on TNBC (a term first mentioned in the medical literature in October 2006) (Foulkes 2010). Since 2009, however, five randomised control trials have published data specifically on the effects of platinum‐based regimens on survival, progression or tumour response in mTNBC participants; the inclusion of these five trials in this review update represents the first meta‐analysis of such trials. Third, some interest remains in the use of platinum agents for the treatment of women with metastatic breast cancer in general (i.e. unselected for intrinsic subtypes such as mTNBC) (Shamseddine 2012). This is notwithstanding the primary conclusion contained in the original version of this review that "...in view of the significant excess toxicity, lack of progression or survival benefit and the availability of less toxic active agents it is difficult to justify the use of platinum‐containing regimens, particularly as first‐line treatment for women with metastatic breast cancer in routine clinical practice."

Objectives

To identify and review the evidence from randomised trials comparing platinum‐containing chemotherapy regimens with regimens not containing platinum in the management of women with metastatic breast cancer.

Additional objectives of this review were to investigate whether or not women in selected subgroups of studies benefited more or less from platinum‐based chemotherapy. Some subgroup analyses included in this review update were conducted in the original version of this review, while others have been added in response to new hypotheses and the availability of new subgroups.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Properly randomised controlled clinical trials (i.e. where the trial report asserts that the trial was randomised and there was no evidence to suggest otherwise).

Types of participants

Women with advanced (metastatic) breast cancer, either newly diagnosed or recurrent. Treatment‐comparisons that included both women with metastatic disease and women with loco‐regionally recurrent disease only were eligible for inclusion if it was possible to distinguish between the two groups (i.e. data were reported separately) or if women with isolated locoregional recurrence were less than 20% of the total group. There were no age restrictions. In the protocol for this review, it was proposed that treatment‐comparisons would be included if the women randomised to receive chemotherapy, were to receive it as first‐line treatment (i.e. no previous chemotherapy given except as adjuvant therapy). As few treatment‐comparisons assessing first‐line treatment were identified for inclusion in the original version of this review, those meeting the remaining eligibility criteria but which involved participants who were not first‐line naive were included. This modification of the inclusion criteria was maintained for this review update, with subgroup analysis by treatment being performed (treatment‐comparisons with first‐line therapy for > 80% of participants vs other treatment lines).

Types of interventions

Interventions were any chemotherapy regimen containing a platinum agent (see Table 4 and Table 5). Comparators were any chemotherapy regimen without a platinum agent. Endocrine therapy may also have been given to participants if it was planned to be given to both treatment groups. Studies may or may not have specified recommended treatment upon disease progression or initial treatment failure or both. This recommended treatment may have included cross‐over to the alternative treatment arm of the treatment‐comparison.

1. Platinum agents.

| Generic name | Other names |

| Carboplatin | Blastocarb, Carboplat, Carboplatin Hexal, Carboplatino, Carbosin, Carbosol, Carbotec, CBDCA, Displata, Ercar, Nealorin, Novoplatinum, Paraplat, Paraplatin AQ, Paraplatin, Paraplatine, Platinwas, Ribocarbo |

| Cisplatin | Abiplatin, Blastolem, Briplatin,CACP, CDDP, cis‐DDP, cis‐diamminedichloridoplatinum, cis‐diamminedichloro platinum (II), cis‐diamminedichloroplatinum, Cis‐dichloroammine Platinum (II), Cismaplat, Cisplatina, cis‐platinous diamine dichloride, cis‐platinum II diamine dichloride, cis‐platinum II, cis‐platinum, Cisplatyl, Citoplatino, Citosin, CPDD, Cysplatyna, DDP, DDP, Lederplatin, Metaplatin, Neoplatin, PDD, Peyrone's Chloride, Peyrone's Salt, Placis, Platamine, Platiblastin, Platiblastin‐S, Platinex, Platinol‐ AQ, Platinol, Platinol‐AQ VHA Plus, Platinol‐AQ, Platinoxan, platinum diamminodichloride, Platiran, Platistin, Platosin |

| Oxaliplatin | Ai Heng, Aiheng, diaminocyclohexane oxalatoplatinum, oxalatoplatin, oxalatoplatinum, oxaliplatine, Eloxatin, Dacotin, Dacplat, Eloxatine, 1‐OHP, L‐OHP, oxaliplatin medac |

2. Chemotherapeutic Agents (adapted from Table 1.1 in The Chemotherapy Source Book).

| Type of Agent | Action | Includes |

| Agents that damage the DNA template | by alkylation: nitrogen mustards | cyclophosphamide, melphalan, ifosfamide, chlorambucil |

| by alkylation: nitrosureas | carmustine (BCNU), lomustine (CCNU) | |

| by alkylation: other agents | thiotepa, mitomycin C | |

| by platinum coordination cross‐linking | cisplatin, carboplatin | |

| antibiotics | doxorubicin, daunorubicin, mitoxantrone, idarubicin, epirubicin, amsacrine | |

| podophyllotoxins | etoposide, teniposide | |

| by intercalation | dactinomycin, mithramycin | |

| by uncertain mechanisms | bleomycin | |

| Spindle poisons | vinca alkaloids | vincristine, vinblastine, vendesine, vinorelbine |

| taxanes | taxol, taxotere | |

| Antimetabolites | thymidylate synthase | 5‐fluorouracil |

| dihydrofolate reductase | methotrexate |

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Overall survival (OS)

Progression‐free survival/time to progression (PFS/TTP)

Secondary outcomes

Time to treatment failure (TTF)

Objective tumour response rate (OTRR)

Toxicity rates (multiple condition‐specific outcomes)

Quality of life measures (multiple outcomes)

The definitions of some outcomes varied slightly across studies included in this review. Outcomes were commonly defined as:

Overall survival (OS): time elapsed between randomisation (or study enrolment or treatment initiation) to date of death from any cause.

Progression‐free survival (PFS): time elapsed between randomisation (or study enrolment or treatment initiation) and event, with event defined as disease progression or death from any cause.

Time to progression (TTP): time elapsed between randomisation (or study enrolment or treatment initiation) and event, with event defined as disease progression (which sometimes included cause‐specific death from the study disease).

Time to treatment failure (TTF): time elapsed between randomisation (or study enrolment or treatment initiation) to treatment discontinuation for any reason, including disease progression, treatment toxicity, participant preference, or death.

Objective tumour response rate (OTRR): the proportion of participants who experienced a complete or partial tumour response (versus stable disease or no response).

Toxicity rates (multiple condition‐specific outcomes): the proportions of participants who experienced a grade 3 or 4 adverse event of nausea and vomiting, nephrotoxicity, anaemia, hair loss and leukopenia based on WHO criteria or individual protocol‐based definitions. We also investigated treatment‐related death which, for the purpose of this review, was defined as death due to the toxicity of the drug and not to disease progression. If an individual trial did not include their definition of a treatment‐related death but used the terms 'toxic death' or 'lethal toxicity', then these deaths were still included in the pooled analysis of treatment related deaths.

Quality of life measures (QoL) (multiple outcomes): various validated instruments for measuring various quality of life domains.

For the purposes of this review, PFS and TTP were analysed as the same outcome (referred to as PFS/TTP), with preference given to PFS for studies reporting both PFS and TTP extractable data.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update of the review, we searched the following databases and registries on the 28 May 2015.

(a) The Cochrane Breast Cancer Specialised Register maintained by the Cochrane Breast Cancer Group (searched 1 June 2015). Details of the search strategies used by the Cochrane Breast Cancer Group for the identification of studies and the procedure used to code references are outlined in their module (www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clabout/articles/BREASTCA/frame.html). Trials coded with the key words 'advanced', 'Cisplatin', 'cisplatinum', 'carboplatin', 'carboplatinum', 'platin', 'platinum', 'platinum diamminodichloride', 'cis‐diamminedichloroplatinum', 'cis‐dichlorodiammineplatinum', 'biocisplatinum', 'dichlorodiammineplatinum', 'nsc‐119875', 'platidiam', 'platino', 'Platinol', 'cis‐diamminedichloroplatinum', 'cis‐platinum', 'cis‐diammine (cyclobutanedicarboxylato) platinum', 'cbdca', 'jm‐8', 'nsc‐241240', 'paraplatin' were extracted for consideration. (b) Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015, Issue 4) in the Cochrane Library (searched 28 May 2015). See Appendix 1. (c) MEDLINE (via OvidSP; July 2008 to 28 May 2015). Searches were conducted from 2008 due to the Cochrane Breast Cancer Group's Specialised Register being out‐of‐date for an interim period. See Appendix 2. (d) Embase (Via Embase.com; July 2008 to 28 May 2015). Searches were conducted from 2008 due to the Cochrane Breast Cancer Group's Specialised Register being out‐of‐date for an interim period. See Appendix 3. (e) The WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx) for all prospectively registered and ongoing trials. See Appendix 4. (f) ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home). See Appendix 5.

No restrictions were applied based on language.

Searching other resources

In addition, we searched the reference lists of other, related literature reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

In the original version of this review and in this review update, two reviewers applied the selection criteria (including the quality of randomisation) to each reference identified by the search strategy while masked to the study results. Any discrepancies regarding eligibility or quality were resolved by consensus or adjudication from a third reviewer. Studies that may appear to have met the eligibility criteria, but which were deemed ineligible are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

In the original version of this review and in this review update, data on the relevant outcomes were extracted by at least two reviewers, with discrepancies resolved by consensus or adjudication from another reviewer. Data were also extracted on information relating to outcome definitions, study accrual, randomisation methods, baseline characteristics of participants (e.g. age, first‐line/second‐line treatment, prior anthracyclines/anthracycline‐naïve), chemotherapy regimens (number of cycles and duration), follow‐up time and analytical methods used. Where available, multiple publications on the same study were obtained and the most complete report was assigned as the primary reference. In instances where a more recent publication was used in this review update for a study that was included in the original version of this review, the year of the reference ID was also updated. Data were entered into the Cochrane Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 5.3) software, and RevMan 5.3 was used for most statistical analyses.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

In this review update, potential sources of bias for all included studies (including those in the original version of this review) were assessed using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011). Risk of bias for each treatment‐comparison was evaluated independently by at least two reviewers and discrepancies were resolved by consensus or adjudication from an additional reviewer. Clarification from authors was sought if the published data provided inadequate information for the review. The 'risk of bias' domains that were assessed were 'random sequence generation', 'allocation concealment', 'blinding of participants and personnel', 'blinding of outcome assessment', 'incomplete outcome data', 'selective reporting' and 'other bias'. For each included study, ratings of 'high', 'low', or 'unclear' risk of bias were assigned for each risk of bias domain following criteria outlined in the 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011).

Open‐label studies are common in phase III oncology trials because it is often difficult to conceal treatments from participants, care‐providers and outcome assessors (due to differences in toxicities and treatment schedules of various treatments, for example). However, because a lack of blinding can affect risk of bias in different ways for different outcomes, we assessed 'blinding of outcome assessment' by dividing outcomes into two outcome classes: 1) OS and 2) outcomes other than OS and quality of life. This division was made because, unlike other outcomes, assessment of OS is unlikely to be affected by non‐blinding.

We also divided the 'incomplete outcome data' risk of bias domain into two outcome classes: 1) time‐to‐event outcomes and 2) binary (i.e. dichotomous) outcomes. For time‐to‐event outcomes, risk of bias was deemed low, unclear, and high risk if time‐to‐event analysis was intention‐to‐treat (ITT), modified intention‐to‐treat (mITT) or per‐protocol, respectively. For the binary outcomes (OTRRs and toxicity rates), risk of bias was deemed low, unclear, and high risk if the highest percentage of randomised participants excluded from effect estimation was less than 10%, between 10% and 15%, or more than 15%, respectively.

For 'risk of bias' domains that were divided into outcome classes, assessments were made for all studies known to be measuring the outcomes, regardless of results being reported in sufficient detail to be included in meta‐analysis or reported at all (e.g. a study might specify OS as an outcome in the study protocol but not report any results).

Measures of treatment effect

OS, PFS/TTP and TTF were analysed as time‐to‐event outcomes, for which the hazard ratio (HR) is the most appropriate measure of treatment effect. If reported, the HR and associated variance were extracted directly from the trial publication(s), and these were used to calculate observed (O) minus expected (E) numbers of events and logrank variance (V) for each treatment‐comparison using the methods described by Tierney 2007 or Parmar 1998. If not reported, O ‐ E and V were obtained indirectly from other available summary statistics or from data extracted from published Kaplan‐Meier curves using the methods described by Tierney 2007 or Parmar 1998. For studies that did not report the relevant effect estimates and required curve extraction, the numbers at risk were based on reported minimum and maximum follow‐up times. If these were not reported, minimum follow‐up was estimated as the time taken to complete treatment, and maximum follow‐up was estimated using the last event reported in the relevant time‐to‐event curve. These follow‐up estimates were recorded in the Characteristics of included studies table under 'Notes'. For the purposes of data extraction, preference was given to time‐to‐event effect estimates derived from ITT analysis, followed by mITT analysis, then per‐protocol analysis.

Pooled HRs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained from the O ‐ E and V statistics for each treatment‐comparison using the fixed‐effect model (Yusuf 1985). The pooled HR represented the instantaneous risk of an event (such as death, disease progression or treatment failure) for women receiving platinum divided by the corresponding risk for those not receiving platinum. HRs less than 1.00 favoured the platinum‐containing regimens and values greater than 1.00 favoured non‐platinum regimens.

Toxicity rates and OTRRs were analysed as proportions using the risk ratio (RR) as the measure of treatment effect. OTRRs were most often calculated by trialists using only participants that were assessable for tumour response. These 'assessable participants' were generally defined as participants whose tumour response could be assessed according to prespecified criteria such as RECIST (Eisenhauer 2009), but this definition was sometimes extended to additionally exclude participants who had not received a specified minimum dose of chemotherapy. In this review update and in the original version of this review, we calculated OTRRs using the numbers of assessable participants in the OTRR denominators, but we also separately calculated OTRRs using the numbers of randomised participants in the denominators. In this review update, however, only the results from the assessable participants analyses were reported as there was almost no difference between the results obtained using assessable and randomised participant denominators (the latter are available on request). Toxicity rates were most often calculated by trialists using a 'safety population' of participants who received a specified minimum dose of chemotherapy. We calculated toxicity rates for each study using the population used by that study.

Pooled RRs and 95% confidence intervals were obtained through Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect analysis. The pooled RR represented the cumulative risk of an event for participants receiving platinum divided by the corresponding risk for those not receiving platinum. RRs greater than 1.00 favoured platinum‐containing regimens and values less than 1.00 favoured non‐platinum regimens.

Quality of life was generally reported as a continuous outcome. Hence, if sufficient quality of life data become available for meta‐analysis in future review updates, the effect measure would most likely be the mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD), depending on whether the same or different validated questionnaires (respectively) were employed.

Unit of analysis issues

Treatment‐comparisons were the unit of analysis in this review and corresponded to pairwise comparisons of platinum and non‐platinum regimens. Individual studies assessing more than one platinum‐based regimen or more than one non‐platinum regimen (or both) contributed more than one treatment‐comparison to the review. Consequently, there were more treatment‐comparisons in this review than there were studies.

Two studies each contained two non‐platinum regimen (control) groups for comparison against a single platinum‐based regimen (intervention) group. This was taken into account when treatment effect statistics were calculated by splitting each study into two treatment‐comparisons (Stemmler 2011 A, Stemmler 2011 B and Fountzilas 2009 A, Fountzilas 2009 B) and halving the number of participants in their intervention groups (for odd numbered group sizes, the additional participant was arbitrarily distributed to the treatment‐comparison with label ending with 'A'). Another study contained two platinum‐based regimen (intervention) groups for comparison against a single non‐platinum (control) group. This study was split into two treatment‐comparisons (Xu 2011 A, Xu 2011 B) with treatment effect statistics calculated by halving the number of participants in the control group (with additional participants again arbitrarily distributed to treatment‐comparisons with label ending with 'A'). One other study was a four‐armed trial and was also reported as two separate treatment‐comparisons (Berruti 2002 A, Berruti 2002 B). For these two treatment‐comparisons, no adjustments to participant numbers were required as their control and intervention groups were unique to each comparison. These methods for correcting for multiple intervention and/or control groups were suggested in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

Attempts were made to contact a number of trial investigators for additional information. Three trialists (Cocconi, Costanza and Fountzilas) provided additional time‐to‐event data which allowed HRs to be extracted.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity between trial results was assessed using the Chi2 test statistic and the I2 statistic. The Chi2 test statistic assesses the amount of variation in a set of trials. Small P values for the Chi2 test statistic suggest that there is more heterogeneity present than would be expected by chance. Chi2 is not a particularly sensitive test: a cut‐off of P value less than 0.10 is often used to indicate significance, but lack of statistical significance does not mean there is no heterogeneity. I2 is the proportion of variation that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. In conjunction with the Chi2 test, we used the I2 statistic to assess heterogeneity using the rule of thumb guide outlined in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011) (i.e. I2 between 0% to 40% might not be important; between 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity; between 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity; and between 75% to 100% considerable heterogeneity).

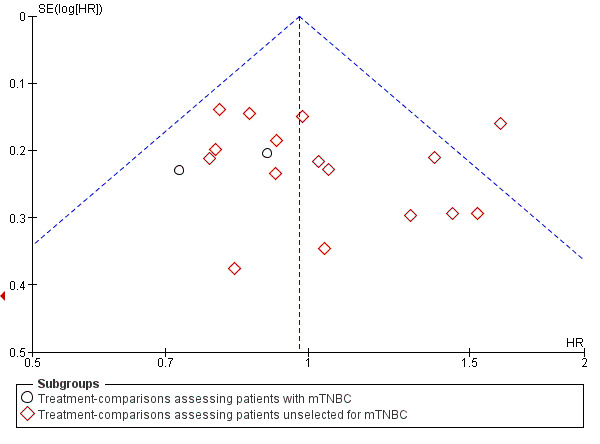

Assessment of reporting biases

In addition to assessing each treatment‐comparison individually for 'selective reporting' using the Cochrane Collaboration's 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (see Assessment of risk of bias in included studies above), publication bias and/or small‐study effects were assessed for the outcomes OS, PFS/TTP and OTRR by visual inspection of funnel plot asymmetry. Egger's statistical test was used to formally assess the degree of asymmetry (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

For time‐to‐event outcomes, RevMan 5.3 was used to estimate pooled HRs and 95% CIs using fixed‐effect models of the derived or reported observed (O) and expected (E) number of events and the variance of the log‐rank statistic (V) for each trial. For binary outcomes, RevMan 5.3 was used to estimate pooled RRs and 95% CIs using the fixed‐effect Mantel‐Haenszel method.

The standard GRADE system (Guyatt 2011) was to use to rate the quality of evidence relating to the estimated treatment effects on OS, PFS/TTP, OTRR, nausea/vomiting, anaemia, hair loss and leukopenia. GRADE criteria for assessing quality of evidence include 'study design', 'risk of bias', 'inconsistency', 'indirectness', 'imprecision', 'suspected publication bias' and 'other considerations'. Assessments of these criteria and corresponding justifications are provided in three 'Summary of findings' tables largely created using GRADEproGDT (GradeproGDT). GRADE assessments were performed separately for selected subgroups related to effect estimate heterogeneity (or 'inconsistency' as labelled in the GRADE assessment criteria).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses were performed to determine whether the results differed by:

mTNBC status: (a) mTNBC participants, (b) participants unselected for mTNBC;

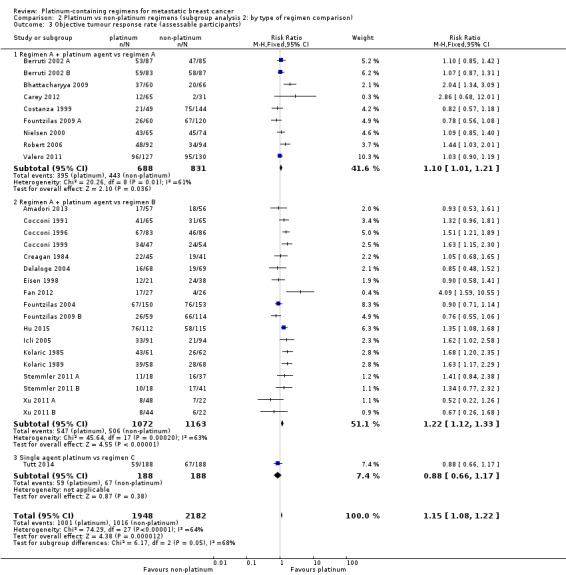

type of regimen comparison: (a) regimen A + platinum vs regimen A, (b) regimen A + platinum vs regimen B, (c) single agent platinum vs regimen C; (note that we allowed "regimen A" to differ in dosage by small amounts between intervention and control arms)

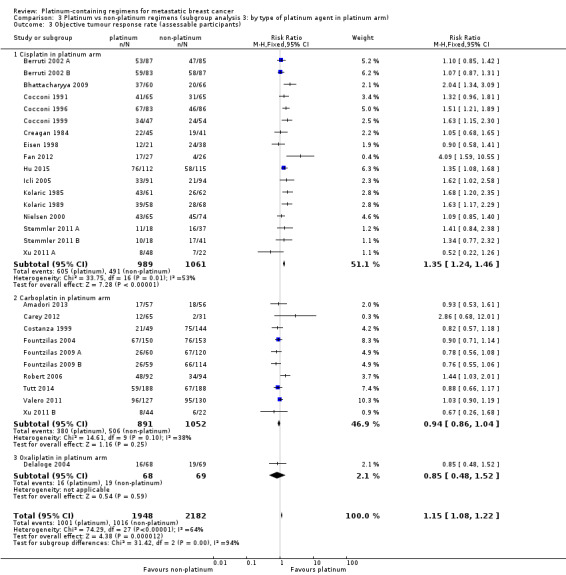

type of platinum agent in platinum arm: (a) cisplatin, (b) carboplatin, (c) oxaliplatin;

first‐line therapy: (a) first‐line therapy for > 80% of participants, (b) second‐ or third‐line therapy for ≥ 20% of participants;

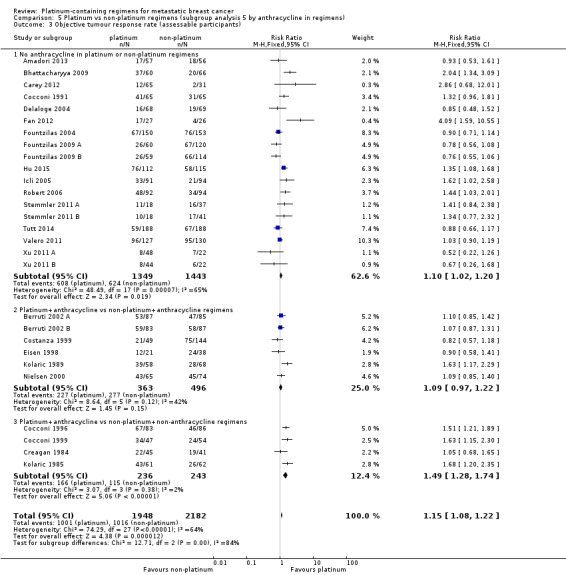

anthracycline in regimens: (a) no anthracycline in platinum or non‐platinum regimens, (b) platinum + anthracycline vs non‐platinum + anthracycline regimen, (c) platinum + anthracycline vs non‐platinum + non‐anthracycline regimens;

taxane in regimens: (a) no taxane in platinum or non‐platinum regimens, (b) platinum + taxane vs non‐platinum + taxane regimens, (c) platinum + non‐taxane vs non‐platinum + taxane regimens;

trastuzumab in regimens: (a) no trastuzumab in platinum or non‐platinum regimens, (b) platinum + trastuzumab vs non‐platinum + trastuzumab regimens

Possible subgroup differences were assessed using Chi2 tests.

Of the above seven subgroup analyses:

Subgroup analysis 2 was the only 'a priori' subgroup analysis pre‐specified in the review protocol; all other subgroup analyses were 'post hoc'.

Subgroup analyses 2, 4, 5 and 6 were conducted in the original review, although additional subgroups have been added for some of these analyses (eg. the conjugate subgroup 'second‐ or third‐line therapy for ≥ 20% of participants' has been added to the 'first‐line therapy' analysis).

In order to reduce the number of forest plots in this review update, toxicity rates were only assessed overall and by subgroup analysis 3 (as 'type of platinum agent' is known to be related to toxicity). Analyses of toxicity rates by other subgroups are available on request.

In this review update, the subgroupings of a few studies have been corrected from the original version of the review. Furthermore, the subgroup analysis 'first‐line therapy' was incorrectly labelled '100% firstline trials' in the original version of the review and the actual cut‐off that was applied was first‐line therapy for > 80% of participants.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess whether apparent inconsistencies in results relating to OS, PFS/TTP and OTRR were more likely to be due to differences in the underlying nature of these outcomes, or an artefact of the different treatment‐comparisons available for the meta‐analysis of each outcome. First, the pooled effect estimate for OTRR was recalculated restricting the meta‐analysis to the 19 treatment‐comparisons with extractable data on OS. Second, the pooled effect estimates for PFS/TTP and OS were recalculated restricting both meta‐analyses to the 12 treatment‐comparisons with extractable data on both OS and PFS/TTP.

In additional sensitivity analyses, PFS/TTP estimates were stratified according to whether the outcome was PFS or TTP. For these analyses, estimates were classified as PFS if the event of interest was defined as disease progression or death from any cause. Estimates were classified as TTP if the event of interest was defined as disease progression, which may also include cause‐specific death from breast cancer. In instances where the event of interest was ambiguously defined or not defined at all, we relied on the authors label of the outcome for classifying as PFS or TTP.

Lastly, to assess the sensitivity of our primary results to our choice of analytical method, we repeated Analysis 1.1, Analysis 1.2 and Analysis 1.3 but using random‐effects rather than fixed‐effect methods.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Platinum vs non‐platinum regimens (subgroup analysis 1: by treatment‐comparisons assessing mTNBC), Outcome 1 Overall survival.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Platinum vs non‐platinum regimens (subgroup analysis 1: by treatment‐comparisons assessing mTNBC), Outcome 2 Progression‐free survival/time to progression.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Platinum vs non‐platinum regimens (subgroup analysis 1: by treatment‐comparisons assessing mTNBC), Outcome 3 Objective tumour response rate (assessable participants).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

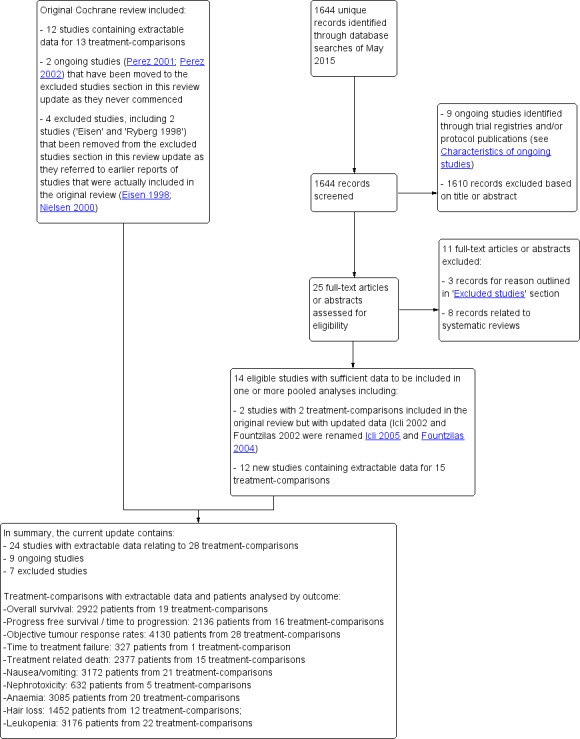

For the 2016 review update, we reviewed 1644 unique records identified by the May 2015 database searches (Figure 1). Of these, 1610 could be excluded based on information in the title or abstract, and nine records from trial registries or protocol publications were considered to be potentially relevant ongoing studies yet to publish results (see Characteristics of ongoing studies). For the remaining 25 records, we retrieved full‐text articles or abstracts for further examination. Eight of the 25 articles or abstracts were excluded because they were reviews (but these were still used to search for further studies by handsearching the bibliographies) and three other full‐text articles were excluded for reasons outlined in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

1.

Review update 2016: study flow diagram.

Included studies

Fourteen studies containing 17 treatment‐comparisons with sufficient data to be included in one or more pooled analyses were identified by this review update. Of these 17 treatment‐comparisons, two had been included in the original review but had since published updated results (Icli 2002 and Fountzilas 2002 in the original review were renamed Icli 2005 and Fountzilas 2004 in this review update), and 15 were new to the review (Amadori 2013 ;Bhattacharyya 2009; Carey 2012; Fan 2012; Delaloge 2004; Fountzilas 2009 A; Fountzilas 2009 B; Hu 2015; Robert 2006; Stemmler 2011 A; Stemmler 2011 B; Tutt 2014; Valero 2011; Xu 2011 A; Xu 2011 B). Overall, the review now includes results from 24 studies corresponding to 28 treatment‐comparisons (see Characteristics of included studies).

Of the 28 treatment‐comparisons included in this review update (Table 6):

3. Number of treatment‐comparisons included in meta‐analyses by subgroup and three outcomes.

| Outcome | ||||

| Subgroup |

Treatment‐ comparisons N |

Overall survival n (% of N) |

Progression ‐free survival/time to progression n (% of N) |

Objective response rate n (% of N) |

| Overall: | 28 | 19 (68%) | 16 (57%) | 28 (100%) |

| Type of platinum agent in platinum arm: | ||||

| Cisplatin in platinum arm | 17 | 11 (65%) | 11 (65%) | 17 (100%) |

| Carboplatin in platinum arm | 10 | 8 (80%) | 5 (50%) | 10 (100%) |

| Oxaliplatin in platinum arm | 1 | (0%) | (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| Type of regimen comparison: | ||||

| Regimen A + platinum agent vs regimen A | 9 | 6 (67%) | 6 (67%) | 9 (100%) |

| Regimen A + platinum agent vs regimen B | 18 | 13 (72%) | 10 (56%) | 18 (100%) |

| Single agent platinum vs regimen C | 1 | (0%) | (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| First‐line therapy: | ||||

| First‐line therapy for > 80% of participants | 20 | 15 (75%) | 11 (55%) | 20 (100%) |

| Second‐ or third‐line therapy for ≥ 20% of participants | 8 | 4 (50%) | 5 (63%) | 8 (100%) |

| Participant selection for mTNBC: | ||||

| Participants with mTNBC | 5 | 3 (60%) | 3 (60%) | 5 (100%) |

| Participants unselected for mTNBC | 23 | 16 (70%) | 13 (57%) | 23 (100%) |

| Anthracycline in regimens: | ||||

| No anthracycline in platinum or non‐platinum regimens | 18 | 14 (78%) | 11 (61%) | 18 (100%) |

| Platinum + anthracycline vs non‐platinum + anthracycline regimens | 6 | 3 (50%) | 4 (67%) | 6 (100%) |

| Platinum + anthracycline vs non‐platinum + non‐anthracycline regimens | 4 | 2 (50%) | 1 (25%) | 4 (100%) |

| Taxane in regimens: | ||||

| No taxane in platinum or non‐platinum regimens | 17 | 9 (53%) | 9 (53%) | 17 (100%) |

| Platinum + taxane vs non‐platinum + taxane regimens | 6 | 6 (100%) | 3 (50%) | 6 (100%) |

| Platinum + non‐taxane vs non‐platinum + taxane regimens | 5 | 4 (80%) | 4 (80%) | 5 (100%) |

| Trastuzumab in regimens: | ||||

| No trastuzumab in platinum or non‐platinum regimens | 26 | 17 (65%) | 14 (54%) | 26 (100%) |

| Platinum + trastuzumab vs non‐platinum + trastuzumab regimens | 2 | 2 (100%) | 2 (100%) | 2 (100%) |

17 (61%) used cisplatin, 10 (36%) used carboplatin and one (4%) used oxaliplatin as the platinum agent in the intervention arm;

9 (32%) compared 'regimen A + platinum vs regimen A', 18 (64%) compared 'regimen A + platinum vs regimen B' and one (4%) compared single agent platinum vs regimen C' (Table 7);

20 (71%) had more than 80% of participants receiving first‐line therapy;

5 (18%) were designed to assess participants with mTNBC;

18 (64%) had no anthracycline in the platinum or non‐platinum regimens, six (21%) had an anthracycline in both regimens, and four (14%) had an anthracycline in the platinum regimen only;

17 (61%) had no taxane in the platinum or non‐platinum regimens; six (21%) had a taxane in both regimens and five (18%) had a taxane in the non‐platinum regimen only;

26 (93%) had no trastuzumab in the platinum or non‐platinum regimens and two (7%) had a trastuzumab in both regimens.

4. Summary of regimens included in the analysis.

| Trials ID | Arm 1 (platinum‐containing) | Arm 2 (control) | First‐line therapy for > 80% of participants | Majority participants anthracycline‐naive |

| Regimen A + platinum vs regimen A | ||||

| Berruti 2002 A | Epi + Cis (epirubicin+cisplatin) | Epi (epirubicin) | Y | Y |

| Berruti 2002 B | Epi + Cis + LND (epirubicin+cisplatin+lonidamine) | Epi + LND (epirubicin + lonidamine) | Y | Y |

| Bhattacharyya 2009 | Endoxan 50 mg per day at 10 am and methotrexate 2.5 mg twice a day at 9 am and 5 pm and with 'cisplatinum' | Endoxan 50 mg per day at 10 am and methotrexate 2.5 mg twice a day at 9 am and 5 pm | N | N |

| Carey 2012 | C + Cb (Cetuximab + carboplatin) | C (Cetuximab with carboplatin added after progression) | N | N |

| Costanza 1999 | CBDA + CAF (carboplatin + cycloheximide + doxorubicin + fluorouracil + methotrexate) | CAF (cycloheximide + doxorubicin + fluorouracil) (methotrexate substituted after total doxorubicin ‐ 540 mg) |

Y | Unclear |

| Fountzilas 2009 A | PCb (paclitaxel + carboplatin) | Pw (paclitaxel) | Y | N |

| Nielsen 2000 | Epi + Cis (epirubicin + cisplatin) | Epi (epirubicin) | Y | Y |

| Robert 2006 | TPC (trastuzumab + paclitaxel + carboplatin) | TP (trastuzumab + paclitaxel) | Y | Unclear |

| Valero 2011 | TCH (trastuzumab + docetaxel + carboplatin) | TH (trastuzumab + docetaxel) | Y | N |

| Regimen A + platinum vs regimen B | ||||

| Amadori 2013 | (pemetrexed + carboplatin) | (vinorelbine + gemcitabine) | N | N |

| Cocconi 1991 | MPEPIV(a) or MPEMi (b) (a: methotrexate, leucovorin, cisplatin, epirubicin, vincristine; b: methotrexate, leucovorin, cisplatin, etoposide, mitomycin) | CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil) | Y | Y |

| Cocconi 1996 | Etop + Cis (etoposide + cisplatin) | CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil) | Y | Unclear |

| Cocconi 1999 | PE + CMF + AL (cisplatin + etoposide + doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide, methotrexate + fluorouracil, lecovorin + allopurinol) | CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil) | Y | Unclear |

| Creagan 1984 | CFP + CAP (cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin + cis‐dichlordiammine + CFP) | CFP (cyclophosphamide + fluorouracil + prednisone) | Y | Y |

| Delaloge 2004 | OXA (oxaliplatin + 5‐flurouracil) | VIN (vinorelbine) | N | N |

| Eisen 1998 | EcisF (5‐flurouracil + epirubicin + cisplatin) | EcycloF (5‐flurouracil + epirubicin + cyclophosphamide) | Y | Y |

| Fan 2012 | TP (docetaxel + cisplatin) | TX (docetaxel + capecitabine) | Y | N |

| Fountzilas 2004 | Epi + Pcb (epirubicin + carboplatin) | Epi + P (epirubicin + paclitaxel) | Y | Y (54%) |

| Fountzilas 2009 B | PCb (paclitaxel + carboplatin) | GDoc (docetaxel + gemcitabine) | Y | N |

| Hu 2015 | (cisplatin + gemcitabine) | (paclitaxel + gemcitabine) | Y | N |

| Icli 2005 | Etop + Cis (etoposide + cisplatin) | P (paclitaxel) | N | N |

| Kolaric 1985 | CAP (cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin + platinum) | CMFVP (cyclophosphamide + methotrexate + 5‐fluorouracil + vincristine + prednisone) | Y | Y |

| Kolaric 1989 | CAP (cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin +platinum) | FAC (5‐flurouracil + doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide) |

Y | Y |

| Stemmler 2011 A | GemCis (gemcitabine + cisplatin) | GemVin (gemcitabine + vinorelbine) | N | N |

| Stemmler 2011 B | GemCis (gemcitabine + cisplatin) | GemCap (gemcitabine + capecitabine) | N | N |

| Xu 2011 A | GemCis (gemcitabine + cisplatin) | GemPac (gemcitabine + paclitaxel) | Y | N |

| Xu 2011 B | GemCarb (gemcitabine + carboplatin) | GemPac (gemcitabine + paclitaxel) | Y | N |

| Single agent platinum vs regimen C | ||||

| Tutt 2014 | C (carboplatin) | D (docetaxel) | N | Unclear |

Not all the studies provided sufficient information on all outcomes for inclusion in meta‐analyses. Of the 28 treatment‐comparisons:

19 (68%), 16 (57%) and 28 (100%) had sufficient data to be included in the meta‐analyses of effect estimates for OS, PFS/TTP and OTRR, respectively (Table 6 and Figure 1);

15 (54%), 21 (75%), 5 (18%), 20 (71%), 12 (43%) and 22 (79%) had sufficient data to be included in the meta‐analyses of effect estimates for treatment‐related death, nausea/vomiting, nephrotoxicity, anaemia, hair loss, and leukopenia, respectively (Table 8 and Figure 1).

5. Summary of outcomes for included trials.

| Trial ID | Extractable OS data for HR estimation1 | Median OS time2 | Extractable PFS/TTP data for HR estimation1 | Median PFS/TTP time2 | Overall response | Treatment‐related deaths | Grade III & IV Toxicity | Accrual3 |

| Regimen A + platinum vs regimen A | ||||||||

| Berruti 2002 A | NR | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Nausea/vomiting Nephrotoxicity Anaemia Leukopenia |

185 |

| Berruti 2002 B | NR | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Nausea/vomiting Nephrotoxicity Anaemia Leukopenia |

186 |

| Bhattacharyya 2009 | NR | Y | NR | Y | Y | NR | NR | 126 |

| Carey 2012 | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | NR | Not extractable | 102 |

| Costanza 1999 | Y | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia Leukopenia |

221 |

| Fountzilas 2009 A | Y | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia Hair loss Leukopenia |

204 |

| Nielsen 2000 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Nausea/vomiting Leukopenia |

155 |

| Robert 2006 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia Leukopenia |

196 |

| Valero 2011 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia |

263 |

| Regimen A + platinum vs regimen B | ||||||||

| Amadori 2013 | NR | NR | Y | Y | Y | Y | Leukopenia | 135 |

| Cocconi 1991 | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | NR | Anaemia Leukopenia |

140 |

| Cocconi 1999 | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | NR | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia Hair loss Leukopenia |

105 |

| Cocconi 1996 | NR | Y | NR | Y | Y | DU | Not extractable | 169 |

| Creagan 1984 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Nausea/vomiting Hair loss Leukopenia |

86 |

| Delaloge 2004 | NR | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | Not extractable | 137 |

| Eisen 1998 | NR | Y | Y | Y | Y | DU | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia Hair loss Leukopenia |

59 |

| Fan 2012 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia Leukopenia |

53 |

| Fountzilas 2004 | Y | NR | NR | NR | Y | NR | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia Leukopenia |

327 |

| Fountzilas 2009 B | Y | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia Hair loss Leukopenia |

212 |

| Hu 2015 | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | Y | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia Hair loss Leukopenia |

236 |

| Icli 2005 | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia Leukopenia |

193 |

| Kolaric 1985 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Y | NR | Nausea/vomiting Nephrotoxicity Anaemia Hair loss Leukopenia |

123 |

| Kolaric 1989 | Y | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia Hair loss Leukopenia |

142 |

| Stemmler 2011 A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia Hair loss Leukopenia |

69 |

| Stemmler 2011 B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Nausea/vomiting Anaemia Hair loss Leukopenia |

72 |

| Xu 2011 A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Nausea/vomiting Nephrotoxicity Anaemia Hair loss Leukopenia |

75 |

| Xu 2011 B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Nausea/vomiting Nephrotoxicity Anaemia Hair loss Leukopenia |

71 |

| Single agent platinum vs regimen C | ||||||||

| Tutt 2014 | NR | Y | NR | Y | Y | NR | NR | 376 |

1 Sufficient data reported to estimate a HR for pooling as outlined by Parmar 1998 and Tierney 2007; this includes Kapalan‐Meier curve, HR and standard error/confidence interval or logrank statistics

2 Trials that did not explicitly report median time were classified as NR here regardless of estimable median time from Kaplan‐Meier curve

3 Accrual numbers represent the maximum numbers of participants in the trial (not study) that were included in the analyses of OS, PFS/TTP or OR (assessable participants).

*NR = not reported, DU = deaths unexplained, Y = data reported.

Three studies reported treatment effects on various quality of life domains (Fountzilas 2004; Fountzilas 2009: Fountzilas 2009 A & Fountzilas 2009 B; Amadori 2013) but these results could not be pooled in a meta‐analysis. Three studies reported TTF results (Amadori 2013; Fountzilas 2004; Xu: Xu 2011 A & Xu 2011 B), but these data were only extractable for Fountzilas 2004.

Excluded studies

In this review update, seven studies may have appeared to have met the eligibility criteria, but were deemed ineligible for reasons given in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Of these seven excluded studies: two were registered trials that were previously listed as 'ongoing studies' in the original review but were reclassified as 'excluded' in this review update because the principal investigator had informed us that the trials never commenced (Perez 2001; Perez 2002); two were 'excluded studies' in the original review and remained so in this review update (Cartei 1996; Hogdall 1993); and three were newly identified in this review update (Crump 2008; Somlo 2015; Wang 2008). Two other studies listed as 'excluded' in the original review ('Eisen' and 'Ryberg 1998') were removed from the excluded studies section altogether in this review update as they referred to earlier reports of studies that were actually included in the original review (Eisen 1998; Nielsen 2000).

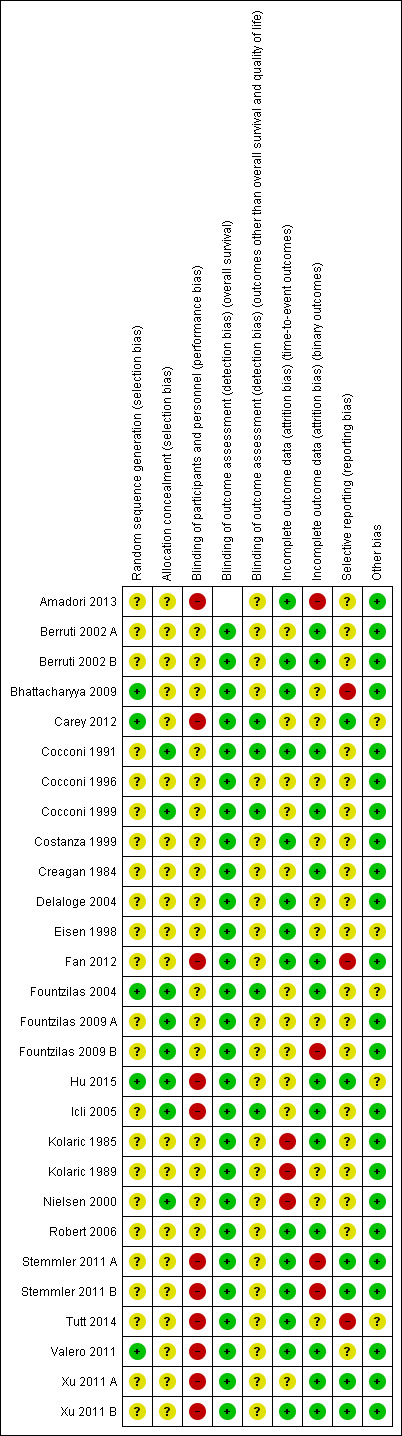

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 2 shows a summary of the 'Risk of bias' judgements for each 'Risk of bias' domain of the included treatment‐comparisons. Reasons for each judgement are detailed for each treatment‐comparison in the Characteristics of included studies table. For each 'risk of bias' domain, a summary of the general risk of bias for results of the included studies was as follows.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All 24 studies, relating to 28 treatment‐comparisons, were described as randomised (this being an inclusion criterion of the review). The method of random sequence generation was described sufficiently to be judged at low risk of bias for this domain in 5 treatment‐comparisons (Bhattacharyya 2009; Carey 2012; Fountzilas 2004; Hu 2015; Valero 2011). The remaining 23 treatment‐comparisons were judged to be at unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation as the information available was insufficient to accurately assess this domain.

Eight of the 28 treatment‐comparisons described central randomisation systems and were thus judged to be at low risk of bias for treatment allocation concealment (Cocconi 1991; Cocconi 1999; Fountzilas 2004; Fountzilas 2009 A; Fountzilas 2009 B; Hu 2015; Icli 2005; Nielsen 2000). The remaining 20 treatment‐comparisons did not adequately describe methods of concealment and were thus judged as having unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Blinding

Eleven treatment‐comparisons were described as 'nonblinded', 'not blinded', 'single blind' or 'open‐label' (Amadori 2013; Carey 2012; Fan 2012; Hu 2015; Icli 2005; Stemmler 2011 A; Stemmler 2011 B; Tutt 2014; Valero 2011; Xu 2011 A; Xu 2011 B). These 11 'unblinded' treatment‐comparisons were judged to be at high risk of 'performance bias' due to the lack of blinding of participants and personnel to the treatment being administered. The remaining 17 treatment‐comparisons were judged as at unclear risk of 'performance bias' because of a lack of information needed to make a firm conclusion. It seemed highly likely, however, that a number of these 17 treatment‐comparisons would have also been 'unblinded', as open‐label studies are common in phase III oncology trials.

All 27 treatment‐comparisons known to have OS as a study outcome (including 8 not included in OS meta‐analyses but excluding Amadori 2013 which did not assess OS as an outcome) were judged to be at low risk of bias from a lack of blinding of outcome assessors, regardless of actual blinding. This is because death certification was unlikely to be affected by any lack of blinding.

For outcomes other than OS and QoL, five treatment‐comparisons were judged to be at low risk of bias from a lack of blinding of outcome assessors due to these outcomes being measured/confirmed through formal assessments including imaging, biochemical tests and/or the involvement of an independent clinical or radiological review group (Carey 2012; Cocconi 1991; Cocconi 1999; Fountzilas 2004; Icli 2005). The remaining 23 treatment‐comparisons provided insufficient detail on outcome assessments and were thus classified as having an unclear risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Three treatment‐comparisons were judged to be at high risk of attrition bias for time‐to‐event outcomes because participants who did not receive a specified number of cycles of chemotherapy were excluded from time‐to‐event analyses (a form of per‐protocol analysis) (Kolaric 1985; Kolaric 1989; Nielsen 2000). Eleven treatment‐comparisons excluded randomised participants who never started treatment or who were subsequently found to have been 'ineligible' from time‐to‐event analyses (mITT analyses) (Berruti 2002 A; Carey 2012; Cocconi 1999; Cocconi 1996; Creagan 1984; Fountzilas 2004; Fountzilas 2009 A; Fountzilas 2009 B; Hu 2015; Icli 2005; Xu 2011 A). These 11 treatment‐comparisons were judged to be at unclear risk of attrition bias for time‐to‐event outcomes. The remaining 14 treatment‐comparisons were judged to be at low risk of attrition bias for time‐to‐event outcomes because all randomised participants were analysed in the groups to which they were randomised (ITT analysis).

Four treatment‐comparisons had more than 15% of participants not assessed/assessable for at least one binary outcome and were thus judged to be at high risk of attrition bias for binary outcomes (Amadori 2013; Fountzilas 2009 B; Stemmler 2011 A; Stemmler 2011 B; ). Fourteen treatment‐comparisons had less than 10% of participants not assessed/assessable for all binary outcomes and were thus judged to be at low risk of attrition bias for binary outcomes (Berruti 2002 A; Berruti 2002 B; Cocconi 1991; Cocconi 1999; Creagan 1984; Fan 2012; Fountzilas 2004; Hu 2015; Icli 2005; Kolaric 1985; Robert 2006; Valero 2011; Xu 2011 A; Xu 2011 B). The remaining 10 treatment‐comparisons were judged to be at unclear risk of attrition bias for binary outcomes (10 to 15% of participants not assessed/assessable for at least one binary outcome or it was unclear what proportion were not assessed).

Selective reporting

The assessment of risk of bias from selective reporting included crosschecking the outcomes for which there were published results against the stated outcomes reported in trial registers (WHO ICTRP and ClinicalTrials.gov) and published protocols. In our assessment of risk of bias from selective reporting, studies that began recruiting participants on or after July 1, 2005 were expected have a clinical registration or published protocol specifying the study outcome or they were deemed to be at high risk of bias from selective reporting. We chose July 1, 2005 as our cut‐off date because the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) made a seminal announcement in September 2004 that clinical trials that begin recruiting on or after July 1, 2005 would not be considered for publication unless they were included on a clinical trials registry (De Angelis 2005). Studies included in this review which began recruiting participants before July 1, 2005 and which did not have a trial registration or published protocol prespecifying study outcomes, were assumed to be at unclear risk of bias from selective reporting, unless additional evidence suggested otherwise.

Six treatment‐comparisons from four studies were judged to be at low risk of bias from the selective reporting of outcomes (Carey 2012; Hu 2015; Stemmler 2011 A; Stemmler 2011 B; Xu 2011 A; Xu 2011 B). Each of these studies was included on a clinical trials registry and their prespecified outcomes either matched those in the trial reports or non‐matches were considered to be relatively minor. Three treatment‐comparisons were judged to be at high risk of bias from the selective reporting of outcomes. The first of these was Tutt 2014 which specified TTP, TTF and toxicity as outcomes in the trial registration, but did not report on these outcomes in either of two conference abstracts (future publications may report in more detail and this 'risk of bias' assessment may change). The second was Fan 2012 which did not have a trial registration or published protocol and did not report the date that participants were first enrolled. However, given that Fan 2012 was first published in December 2012 and that there were only 53 study participants, it seemed highly likely that recruitment began after July 1, 2005. Consequently, there was a high expectation of trial registration which this study failed to undertake. The third of these was Bhattacharyya 2009 in which the abstract indicated that toxicity was recorded but no results were reported. In addition, for Bhattacharyya 2009, there was no trial registration or published protocol containing prespecified outcomes. The date that participant recruitment began was not reported, but given that this was first published in September 2009, it seemed likely that recruitment began after July 1, 2005. As of April 2015, there had been no further results published other than those in the conference abstract. The remaining 19 treatment‐comparisons were judged to be at unclear risk of bias from the selective reporting of outcomes either because the trial was unregistered with recruitment starting before July 1, 2005 or the stated outcomes in the registry did not match those in the trial reports, but it was unclear if these non‐matches posed a high risk of bias.