Abstract

Background

Despite substantial improvements in myocardial preservation strategies, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is still associated with severe complications. It has been reported that remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) reduces reperfusion injury in people undergoing cardiac surgery and improves clinical outcome. However, there is a lack of synthesised information and a need to review the current evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of remote ischaemic preconditioning in people undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting, with or without valve surgery.

Search methods

In May 2016 we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and Web of Science. We also conducted a search of ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). We also checked reference lists of included studies. We did not apply any language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs in which people scheduled for CABG (with or without valve surgery) were randomly assigned to receive RIPC or sham intervention before surgery.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion, extracted data and checked them for accuracy. We calculated mean differences (MDs), standardised mean differences (SMDs) and risk ratios (RR) using a random‐effects model. We assessed quality of the trial evidence for all primary outcomes using the GRADE methodology. We completed a ’Risk of bias’ assessment for all studies and performed sensitivity analysis by excluding studies judged at high or unclear risk of bias for sequence generation, allocation concealment and incomplete outcome data. We contacted authors for missing data. Our primary endpoints were 1) composite endpoint (including all‐cause mortality, non‐fatal myocardial infarction or any new stroke, or both) assessed at 30 days after surgery, 2) cardiac troponin T (cTnT, ng/L) at 48 hours and 72 hours, and as area under the curve (AUC) 72 hours (µg/L) after surgery, and 3) cardiac troponin I (cTnI, ng/L) at 48 hours, 72 hours, and as area under the curve (AUC) 72 hours (µg/L) after surgery.

Main results

We included 29 studies involving 5392 participants (mean age = 64 years, age range 23 to 86 years, 82% male). However, few studies contributed data to meta‐analyses due to inconsistency in outcome definition and reporting. In general, risk of bias varied from low to high risk of bias across included studies, and insufficient detail was provided to inform judgement in several cases. The quality of the evidence of key outcomes ranged from moderate to low quality due to the presence of moderate or high statistical heterogeneity, imprecision of results or due to limitations in the design of individual studies.

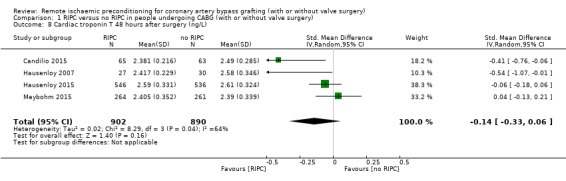

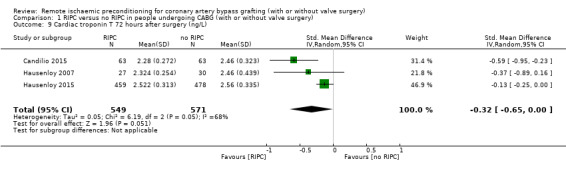

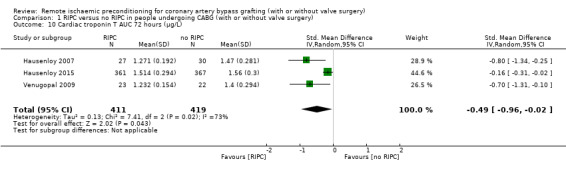

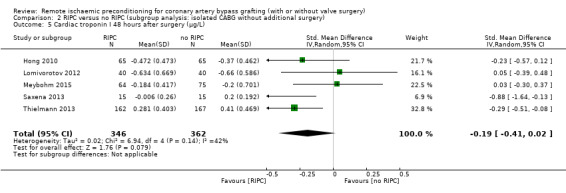

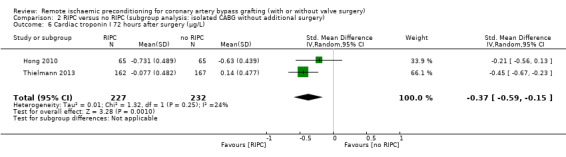

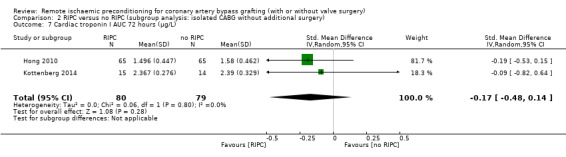

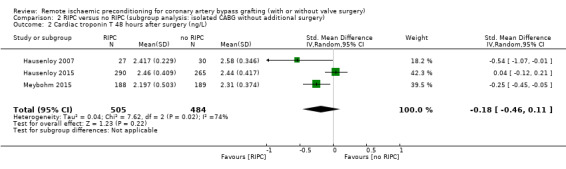

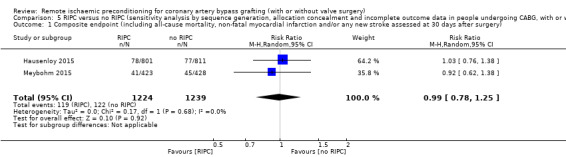

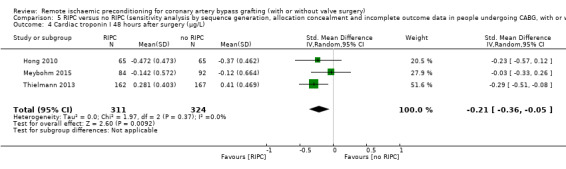

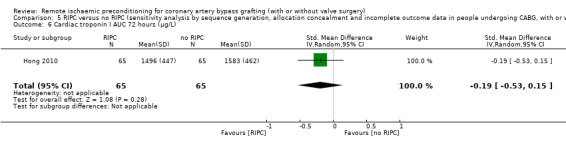

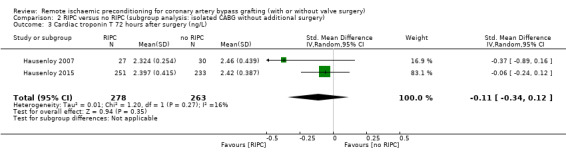

Compared with no RIPC, we found that RIPC has no treatment effect on the rate of the composite endpoint with RR 0.99 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78 to 1.25); 2 studies; 2463 participants; moderate‐quality evidence. Participants randomised to RIPC showed an equivalent or better effect regarding the amount of cTnT release measured at 72 hours after surgery with SMD ‐0.32 (95% CI ‐0.65 to 0.00); 3 studies; 1120 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; and expressed as AUC 72 hours with SMD ‐0.49 (95% CI ‐0.96 to ‐0.02); 3 studies; 830 participants; moderate‐quality evidence. We found the same result in favour of RIPC for the cTnI release measured at 48 hours with SMD ‐0.21 (95% CI ‐0.40 to ‐0.02); 5 studies; 745 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; and measured at 72 hours after surgery with SMD ‐0.37 (95% CI ‐0.59 to ‐0.15); 2 studies; 459 participants; moderate‐quality evidence. All other primary outcomes showed no differences between groups (cTnT release measured at 48 hours with SMD ‐0.14, 95% CI ‐0.33 to 0.06; 4 studies; 1792 participants; low‐quality evidence and cTnI release measured as AUC 72 hours with SMD ‐0.17, 95% CI ‐0.48 to 0.14; 2 studies; 159 participants; moderate‐quality evidence).

We also found no differences between groups for all‐cause mortality after 30 days, non‐fatal myocardial infarction after 30 days, any new stroke after 30 days, acute renal failure after 30 days, length of stay on the intensive care unit (days), any complications and adverse effects related to ischaemic preconditioning. We did not assess many patient‐centred/salutogenic‐focused outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

We found no evidence that RIPC has a treatment effect on clinical outcomes (measured as a composite endpoint including all‐cause mortality, non‐fatal myocardial infarction or any new stroke, or both, assessed at 30 days after surgery). There is moderate‐quality evidence that RIPC has no treatment effect on the rate of the composite endpoint including all‐cause mortality, non‐fatal myocardial infarction or any new stroke assessed at 30 days after surgery, or both. We found moderate‐quality evidence that RIPC reduces the cTnT release measured at 72 hours after surgery and expressed as AUC (72 hours). There is moderate‐quality evidence that RIPC reduces the amount of cTnI release measured at 48 hours, and measured 72 hours after surgery. Adequately‐designed studies, especially focusing on influencing factors, e.g. with regard to anaesthetic management, are encouraged and should systematically analyse the commonly used medications of people with cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: Adult; Aged; Aged, 80 and over; Female; Humans; Male; Middle Aged; Coronary Artery Bypass; Area Under Curve; Cause of Death; Heart Valves; Heart Valves/surgery; Ischemic Preconditioning; Ischemic Preconditioning/adverse effects; Ischemic Preconditioning/methods; Ischemic Preconditioning/mortality; Myocardial Infarction; Myocardial Infarction/epidemiology; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Stroke; Stroke/epidemiology; Troponin I; Troponin I/metabolism; Troponin T; Troponin T/metabolism

Plain language summary

Effects of remote ischaemic preconditioning in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery (with or without valve surgery)

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about the effect of remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC, the temporary blockage of arterial blood flow to one arm or one leg before surgery after induction of anaesthesia) in people undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery with or without additional valve surgery.

Background

Coronary artery disease (CAD) results from progressive blockage of the coronary arteries. If coronary arteries are partly or fully blocked, they cannot supply the heart with enough oxygen. Symptoms of CAD include shortness of breath, pain in the upper body (e.g. arms, left shoulder, back, etc). CAD can be treated with medical therapy, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Despite substantial improvements in surgical strategies, cardiac surgery is associated with severe complications. Several approaches have been implemented to reduce the risk during surgery (hypothermia, cardioplegic solutions, and the limitation of procedure times). These strategies have led to a pronounced reduction in mortality and morbidity, however, biomarkers of ischaemia indicate persisting postoperative myocardial damage. RIPC has been reported to reduce these biomarkers of ischaemia in people who undergo cardiac surgery. The aim of this systematic review was to assess whether this practice improves clinical outcomes.

Study characteristics

We searched scientific databases for randomised trials in which people scheduled for CABG (with or without valve surgery) were randomly assigned to receive RIPC or sham intervention before surgery. The evidence is current to May 2016. We did not identify any source of bias related to the funding of included studies.

Key results

We identified 29 studies involving 5392 participants (mean age = 64 years, age range 23 to 86 years, 82% male). RIPC does not improve clinical outcome in people undergoing CABG with or without valve surgery (measured as a composite endpoint including all‐cause mortality, non‐fatal myocardial infarction or any new stroke, or both, assessed at 30 days after surgery, moderate‐quality evidence). There is moderate‐quality evidence that RIPC reduces the amount of cardiac troponin T release measured at 72 hours and measured as AUC (72 hours). There is moderate‐quality evidence that cardiac troponin I release measured at 48 hours and 72 hours after surgery is lower in the RIPC group than in the control group. Regarding troponin T measured at 48 hours and troponin I measured as AUC 72 hours after surgery there was no difference between groups (low‐ and moderate‐quality evidence). However, this effect on biomarkers does not result in improved clinical outcome.

Quality of the evidence

We used reliable methods to assess the quality of the trial evidence. The quality of the evidence of key outcomes ranged from moderate to low quality due to the presence of moderate or high statistical heterogeneity, imprecision of results or due to limitations in the design of individual studies.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery).

| RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery)

Settings: hospital

Intervention: RIPC Comparison: no RIPC | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk no RIPC | Corresponding risk RIPC | |||||

| Composite endpoint (including all‐cause mortality, non‐fatal myocardial infarction and/or any new stroke assessed at 30 days after surgery) | 98 per 1000 | 97 per 1000 (77 to 123) | RR 0.99 (0.78 to 1.25) | 2463 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate1 | |

| Cardiac troponin T (cTnT) 48 h after surgery (ng/L) | The mean cTnT 48 h after surgery (ng/L) ranged across control groups from 2.39 to 2.61 | The mean cTnT 48 h after surgery (ng/L) in the intervention groups was 0.04lower (0.1 lower to 0.01 higher) | SMD ‐0.14 (‐0.33 to 0.06) | 1792 (4) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ low2 | A lower troponin value indicates improvement |

| cTnT 72 h after surgery (ng/L) | The mean cTnT 72 h after surgery (ng/L) ranged across control groups from 2.457 to 2.563 | The mean cTnT 72 h after surgery (ng/L) in the intervention groups was 0.1lower (0.21 to 0 lower) | SMD ‐0.32 (‐0.65 to ‐0.00) | 1120 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate3 | A lower troponin value indicates improvement |

| cTnT AUC 72 h (ng/L) | The mean cTnT AUC 72 h after surgery (ng/L) ranged across control groups from 1.399 to 1.562 | The mean cTnT AUC 72 h (µg/L) in the intervention groups was 0.12lower (0.23 to 0.02 lower) | SMD ‐0.49 (‐0.96 to ‐0.02) | 830 (3) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ moderate3 | A lower troponin value indicates improvement |

| Cardiac troponin I (cTnI) 48 h after surgery (ng/L) | The mean cTnI 48 h after surgery (ng/L) ranged across control groups from ‐0.663 to 0.41 | The mean cTnI 48 h after surgery (µg/L) in the intervention groups was 0.11 lower (0.17 lower to 0.05 lower) | SMD ‐0.21 (‐0.40 to ‐0.02) | 745 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate3 | A lower troponin value indicates improvement |

| cTnI 72 h after surgery (ng/L) | The mean cTnI 72 h after surgery (ng/L) ranged across control groups from ‐0.631 to 0.141 | The mean cTnI 72 h after surgery (µg/L) in the intervention groups was 0.18 lower (0.29 lower to 0.06 lower) | SMD ‐0.37 (‐0.59, ‐0.15) | 459 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate4 | A lower troponin value indicates improvement |

| cTnI AUC 72 h (ng/L) | The mean cTnI AUC 72 h after surgery (ng/L) ranged across control groups from 1.583 to 2.394 | The mean cTnI AUC 72 h (µg/L) in the intervention groups was 0.07lower (0.19 lower to 0.06 higher) | SMD ‐0.17 (‐0.48 to 0.14) | 159 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate1 | A lower troponin value indicates improvement |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AUC: area under the curve; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CI: confidence interval; RIPC: remote ischaemic preconditioning; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference (we used the SMD to combine data of troponin values as these biomarkers were most likely measured by using different laboratory assays.) | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Downgraded one step due to imprecision of results as shown in wide confidence intervals crossing line of no effect 2Downgraded two steps due to presence of moderate or substantial heterogeneity and imprecision of results as shown in wide confidence intervals crossing line of no effect 3Downgraded one step due to presence of moderate or substantial heterogeneity 4Downgraded one step due limitations in the design and implementation of the two available studies suggesting high likelihood of bias (one study was planned with 80 participants, during the course of the study it was decided to include another 50 participants "to increase power"; general small sample size n = 459)

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the major contributor to the burden of disease and the number one cause of death worldwide. In 2008, 30% of all global deaths (17.3 million) were attributed to CVD (World Health Organization 2015). Of these deaths, an estimated 7.3 million were due to coronary artery disease (World Health Organization 2011).

Despite substantial improvements in myocardial preservation strategies, cardiac surgery is still associated with severe complications. This includes atrial arrhythmias, a very common and most often benign complication, with little influence on the postoperative course or long‐term outcome (Bojar 2011). However, less common complications (such as stroke, mediastinitis, tamponade, renal failure, or an acute abdomen) may be catastrophic and lead to death or prolonged hospitalisation with multisystem organ failure (Bojar 2011). The incidence of complications will further increase in the future as cardiac surgery is increasingly being performed on an aging population with increased numbers of comorbid conditions and complex coronary lesions. Analyses of large patient databases indicate that major complications including death, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest and failure, renal failure, stroke, gastrointestinal complications and respiratory failure occur in up to 16% of all people during the initial hospital stay (Ghosh 2004).

Description of the condition

Worldwide, an estimated 800,000 to 1,000,000 CABG procedures are performed annually, with about 400,000 in the USA alone (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015). Most commonly, the procedure is performed through a median sternotomy with the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and cardioplegic arrest. Revascularisation during CABG is obtained by creating new routes for the blood (bypasses) around narrowed or blocked coronary arteries. Autologous venous or arterial graft material is harvested from the patients' internal thoracal wall or from the patients' extremities and re‐implanted in aortocoronary position. In addition to the open surgical procedure under circulatory arrest, both minimally‐invasive and beating‐heart strategies exist.

Several approaches have been implemented to reduce the perioperative risk of myocardial ischaemia. Among the most commonly applied are hypothermia, cardioplegic solutions and the general limitation of procedure times. These strategies have led to a pronounced reduction in procedural mortality and morbidity (Estafanous 2001). Nevertheless, postoperative elevated creatine kinase or troponin levels indicate persisting myocardial damage due to intraoperative ischaemia reperfusion (I/R) injury. Methods of pre‐ and post conditioning have been proven to reduce I/R damage in vitro, however the translation into a clinically relevant protective strategy is still challenging.

Description of the intervention

Ischaemic preconditioning is an experimental method to increase the body's resistance to a projected reduced oxygen supply. In the heart, ischaemic preconditioning is an intrinsic process whereby repeated short episodes of ischaemia protect the myocardium against successive ischaemic insults by decreasing the infarct size.

Since the mid‐1980s, the existence of preconditioning as a protective mechanism has been known from animal models (Murry 1986). A brief stimulus of sub‐lethal ischaemia was able to induce at least two time windows in which the myocardium is protected from otherwise deleterious noxa. In recent decades, several alternative stimuli (e.g. opioids, volatile anaesthetics, noble gases) have been shown to induce at least a partially similar effect. Amazingly, the effect can also be induced by a remotely applied temporary ischaemia. The term remote ischaemic preconditioning was first coined by Przylenk in 1993 (Przyklenk 1993). The remote ischaemic preconditioning intervention is performed by temporary inflation of a blood pressure cuff above the systolic arterial pressure on one chosen extremity. The blood flow from and to this extremity is blocked and local ischaemia occurs. Reperfusion washes released mediators from the isolated tissue into the circulation aiming to enhance the circulating level of cardioprotective substances.

Within the past decade, remote ischaemic preconditioning has been rapidly translated from experimental studies to promising proof‐of‐principle clinical trials. Various studies have demonstrated that RIPC reduces myocardial injury in various surgical settings (Ali 2007; Cheung 2006; Hausenloy 2007; Hausenloy 2010; Hausenloy 2012; Heusch 2010; Thielmann 2010). In contrast, other reports have not confirmed the positive effects of RIPC (Karuppasamy 2011; Young 2012). The underlying reasons might be the RIPC protocol itself or the use of volatile anaesthetics in several of these studies, which in itself is known to protect the heart against ischaemia/reperfusion injury (Karuppasamy 2011; Kottenberg 2012).

Currently, adverse events associated with RIPC are not known. The repeated pumping up of the blood pressure cuff is considered to be safe, and since the intervention occurs after the induction of anaesthesia, additional pain or feelings of stress through the actual intervention are unlikely. The potential risk of thrombosis, plaque rupture or embolisation in people with pre‐existing atherosclerosis in the upper extremities is also regarded as low.

How the intervention might work

In remote ischaemic preconditioning, temporal ischaemia of a distant compartment positively affects the human heart. The humoral factors involved are unclear, but it is largely agreed upon that the effect is mediated via the blood stream. Suspected mediators are nitrites (Corti 2014; Rassaf 2014), microRNA (Li 2014; Slagsvold 2014), and other chemokines. Within the myocardium, the effect is supposedly mediated via the reperfusion injury salvage kinase (RISK) and survivor activating factor enhancement (SAFE) pathways (Hausenloy 2011), and preserves mitochondrial function (Slagsvold 2014) and myocardial performance (Illes 1998; Li 1999; Lu 1997) in ischaemia/reperfusion.

Why it is important to do this review

Several randomised trials comparing RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG have been conducted, but the results have varied and most trials were too underpowered to reach a conclusion on clinically relevant outcome measures. Following the conduct of several small trials, two major trials on remote ischaemic preconditioning have now completed recruitment and provided data on 3012 people undergoing CABG/cardiac surgery (Hausenloy 2015; Meybohm 2015). Final consensus is needed on the effectiveness of RIPC for cardiac patients scheduled for CABG.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of remote ischaemic preconditioning in people undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting, with or without valve surgery.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), studies reported in full text, those published as an abstract only and unpublished data.

Types of participants

We included adults (people aged 18 years or more) scheduled for CABG (with or without valve surgery).

Types of interventions

We included trials comparing remote ischaemic preconditioning before CABG (with or without valve surgery) with no remote ischaemic preconditioning before CABG (with or without valve surgery).

Types of outcome measures

As no core outcome set for clinical studies investigating CABG is available, we have chosen the list of outcomes based on outcome measures from possible matching studies.

Primary outcomes

Composite endpoint (including all‐cause mortality, non‐fatal myocardial infarction or any new stroke, or both) assessed at 30 days after surgery

Cardiac troponin T (cTnT, ng/L) at 48 hours, 72 hours, and as area under the curve (AUC) 72 hours (µg/L) after surgery

Cardiac troponin I (cTnI, ng/L) at 48 hours, 72 hours, and as area under the curve (AUC) 72 hours (µg/L) after surgery

Secondary outcomes

All‐cause mortality after 30 days

Non‐fatal myocardial infarction after 30 days

Any new stroke after 30 days

Acute renal failure after 30 days

Length of stay on the intensive care unit (days)

Any complications and adverse effects related to ischaemic preconditioning, as reported by trial authors

Any patient‐centred/salutogenic‐focused outcome, as reported in included study

Cardiac troponin T (cTnT, ng/L) at 6 hours, 12 hours, and 24 hours after surgery

Cardiac troponin I (cTnI, ng/L) at 6 hours, 12 hours, and 24 hours after surgery

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials through systematic searches of the following bibliographic databases on 4 May 2016:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, 2016, Issue 4) in the Cochrane Library;

MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to April week 3 2016);

Embase (Ovid, 1980 to 2016 week 18);

Web of Science Core Collection (Thomson Reuters, 1900 to 3 May 2016).

We used the search strategies developed by Cochrane Heart for the database searches. The preliminary search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid) was adapted for use in the other databases (Appendix 1). We applied the Cochrane sensitivity‐maximising RCT filter (Lefebvre 2011) to MEDLINE (Ovid) and adaptations of it to the other databases, except CENTRAL.

We also conducted a search of ClinicalTrials.gov (www.ClinicalTrials.gov) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) in May 2016, for possible matching studies using the search terms "remote" and "preconditioning OR pre‐conditioning".

We searched all databases from their inception to the present, and we imposed no restriction on language of publication.

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We contacted study authors for missing data. We also contacted principal investigators of identified studies to ascertain if they were aware of any other relevant published or unpublished matching clinical studies.

Data collection and analysis

The methods used in this review are in accordance with the recommendations provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a).

Selection of studies

We imported citations from each database into the reference management software Papers (Version 3.4.0) and removed duplicates. Two authors (CB, CS) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search and coded them as 'retrieve' (eligible or potentially eligible/unclear) or 'do not retrieve'. In two cases of disagreements, we asked a third author to arbitrate (AG).

We retrieved the full‐text study reports/publication and two authors (CB, AG) independently screened the full text and identified studies for inclusion. We identified and recorded reasons for the exclusion of ineligible studies (see 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables). We resolved any disagreement through discussion. We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) (Moher 2009) and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

1.

Study flow diagram

Data extraction and management

We used a purposely pre‐developed data collection form for study characteristics and outcome data, which we piloted on one study in the review. Two review authors (CB, JN) extracted the following study characteristics from the included studies (also compare Table 2).

1. Overview characteristics of included studies.

| Type of publication | Type of data included in this review | Number of participants randomised (total n = 5409) | Type of surgery | Off or on‐pump procedure | Anaesthestetic gas used | Location of RIPC and number of cycles of RIPC | RIPC intervention | Control/comparison intervention | |

| Ahmad 2014 | Journal article | Published data only | 67 | CABG | On‐pump | Sevoflurane/ isoflurane anaesthesia | Right upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Deflated cuff |

| Ali 2010 | Journal article | Published data only | 100 | CABG | Not reported | Not reported | Right or left upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Deflated cuff (30 min) |

| Candilio 2015 | Journal article | Published and unpublished data | 180 | CABG and/or valve surgery | On‐pump | Isoflurane, sevoflurane, propofol anaesthesia | Upper arm + upper thigh, 2 cycles | 200 mmHg or 15 mmHg above systolic blood pressure for 5 min | Deflated cuff (20 min) |

| Gallagher 2015 | Journal article | Published data only | 86 | CABG with or without aortic valve replacement | On‐pump | 85% isoflurane anaesthesia, rest unknown | Forearm, 3 cycles | Not reported | Deflated cuff (30 min) |

| Gegouskov 2009 | abstract | Published data only | 40 | CABG | Not reported | Not reported | Upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Not reported |

| Günaydin 2000 | Journal article | Published data only | 8 | CABG | On‐pump | Fentanyl anaesthesia | Right upper arm, 2 cycles | 300 mmHg for 3 min | Deflated cuff |

| Hausenloy 2007 | Journal article | Published data only | 57 | CABG | On‐pump | Propofol anaesthesia | Right upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Deflated cuff (30 min) |

| Hausenloy 2015 | Journal article | Published and unpublished data | 1612 | CABG with or without valve surgery | On‐pump | Propofol and volatile anaesthesia | Upper arm, 4 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Simulated RIPC |

| Hong 2010 | Journal article | Published data only | 130 | CABG | Off‐pump | Sevoflurane anaesthesia | Upper arm, 4 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Simulated RIPC |

| Joung 2013 | Journal article | Published data only | 98 | CABG | Off‐pump | Propofol anaesthesia | Upper arm, 4 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Deflated cuff |

| Karuppasamy 2011 | Journal article | Published data only | 54 | CABG | On‐pump | Propofol anaesthesia | Left upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Deflated cuff (30 min) |

| Kottenberg 2014 | Journal article | Published data only | 24 | CABG | On‐pump | Propofol anaesthesia | Left upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Deflated cuff |

| Krawczyk 2010 | abstract | Published data only | 14 | CABG | Off‐pump | Not reported | Right upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Not reported |

| Krawczyk 2011 | abstract | Published data only | 19 | CABG | Off‐pump | Not reported | Right upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Not reported |

| Krawczyk 2012 | abstract | Published data only | 30 | CABG | Off‐pump | Not reported | Right upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Not reported |

| Krogstad 2015 | Journal article | Published data only | 92 | CABG | On‐pump | Propofol and isoflurane anaesthesia | Upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Deflated cuff |

| Lomivorotov 2012 | Journal article | Published and unpublished data | 80 | CABG | On‐pump | isoflurane anaesthesia | Upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Deflated cuff (30 min) |

| Lucchinetti 2012 | Journal article | Published data only | 55 | CABG | On‐pump | Isoflurane anaesthesia | Lower limb, 4 cycles | 300 mmHg for 5 min | Not reported |

| Meybohm 2013 | Journal article | Published and unpublished data | 180 | Cardiac surgery | On‐pump | Propofol anaesthesia | Upper arm, 4 cycles | 200 mmHg or 15 mmHg above systolic blood pressure for 5 min | Deflated cuff |

| Meybohm 2015 | Journal article | Published and unpublished data | 1385 | Cardiac surgery | On‐pump | Propofol anaesthesia | Upper arm, 4 cycles | 200 mmHg or 15 mmHg above systolic blood pressure for 5 min | Dummy arm used for similar cycles of inflation and deflation |

| Rahman 2010 | Journal article | Published data only | 162 | CABG | On‐pump | Propofol anaesthesia | Upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Dummy arm used for similar cycles of inflation and deflation |

| Saxena 2013 | Journal article | Published data only | 30 | CABG | On‐pump | Not reported | Upper arm, 3 cycles | 20 mmHg above systolic blood pressure for 5 min | Deflated cuff |

| Shmyrev 2011 | abstract | Published data only | 31 | CABG | On‐pump | Not reported | Upper arm, 3 cycles | Not reported | Not reported |

| Slagsvold 2014 | Journal article | Published data only | 60 | CABG | On‐pump | Isoflurane anaesthesia | Upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Deflated cuff |

| Sosorburam 2014 | abstract | Published data only | 268 | CABG | On‐pump | Not reported | 3 cycles | Not reported | Deflated cuff |

| Thielmann 2013 | Journal article | Published and unpublished data | 329 | CABG | On‐pump | Isoflurane or propofol anaesthesia | Upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Deflated cuff |

| Venugopal 2009 | Journal article | Published data only | 45 | CABG with or without aortic valve replacement | On‐pump | Isoflurane/sevoflurane or propofol anaesthesia | Right upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Deflated cuff (30 min) |

| Yildirim 2016 | Journal article | Published data only | 60 | CABG | On‐pump | Fentanyl anaesthesia | Left lower limb, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Deflated cuff (25 min) |

| Young 2012 | Journal article | Published and unpublished data | 96 | CABG and/or valve surgery | On‐pump | Volatile anaesthesia | Upper arm, 3 cycles | 200 mmHg for 5 min | Dummy arm used for similar cycles of inflation and deflation |

CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; RIPC: remote ischaemic preconditioning

Methods: study design, total duration of study, details of any 'run‐in' period, number of study centres and location, study setting, withdrawals and date of study

Participants: number (N), mean age, age range, gender, severity of condition (e.g. number of affected vessels, left ventricular ejection fraction), inclusion and exclusion criteria, reported differences between intervention and comparison groups

Interventions: intervention, comparison, concomitant medications and excluded medications, types of anaesthesia

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, and time points reported

Notes: funding for trial and notable conflicts of interest of trial authors

Two authors (CB, JN) independently extracted outcome data from the included studies. We resolved disagreements by consensus. One author (CB) transferred data into the Cochrane statistical software Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) (RevMan 2014). We double‐checked that data were entered correctly (CB, AG, JN) by comparing the data presented in the systematic review with the study reports. A second author (JN) checked the study characteristics for accuracy against the trial report.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

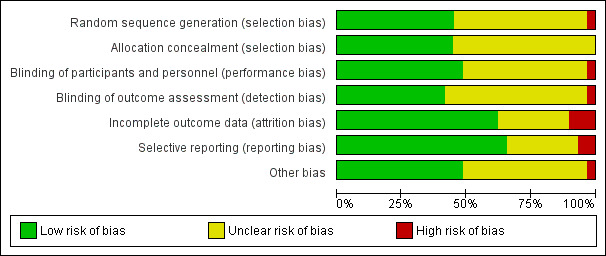

Two authors (CB, JN) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by involving another author (AG, CS). We summarised the results of the 'Risk of bias' assessment in both a 'Risk of bias' graph (Figure 2) and a 'Risk of bias' summary (Figure 3). Seven 'Risk of bias' domains (random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias); blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias); blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias); allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias); incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations); selective reporting (checking for reporting bias); and other bias (checking for other biases)) have been identified and we outline in Appendix 2 how we assessed the risk in relation to each of these domains.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

We summarised the risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). Where information on risk of bias relates to unpublished data or correspondence with a trialist, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table. We interpreted the results of the systematic review and meta‐analyses in light of the findings with respect to risk of bias. When considering treatment effects, we took into account the risk of bias for the studies that contributed to that outcome.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted the review according to the published protocol of the review (Benstoem 2015a) and report any deviations from it in the Differences between protocol and review section of this review.

Assessment of the quality of the evidence

For this review we assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach (Schunemann 2009). The GRADE approach considers five areas (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from ’high quality’ by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations. We assessed the quality of the body of evidence for our primary outcomes for the comparison RIPC versus no RIPC to create a Table 1.

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed dichotomous data as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For continuous data, we used the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI for outcomes measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI to combine data of troponin values, as these biomarkers are typically measured by using different laboratory assays. As the distribution of troponin values is heavily skewed, approximate normal distribution is only existent on a logarithmic (log) scale. Following statistical advice, we therefore asked all included trials to provide data (means and standard deviation) on a log scale. In the case where this data could not be provided, we used the existing mean and standard deviation on a linear scale to approximately estimate the log scaled mean and standard deviation. eWe have described the formula for this in the Data synthesis section.

Unit of analysis issues

As we only included RCTs with a parallel design, unit of analysis issues did not occur.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted investigators (see Characteristics of included studies/Characteristics of excluded studies tables) to verify key study characteristics and to obtain missing numerical outcome data where possible (e.g. when a study was identified as an abstract only). Where this was not possible, and the missing data was thought to introduce serious bias, we explored the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results by a sensitivity analysis. We carried out analyses on an intention‐to‐treat basis for all outcomes, as far as possible.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Where we pooled data using meta‐analysis, we assessed the presence heterogeneity by visual inspection of forest plots and by examining the Chi² test for heterogeneity (Deeks 2009). We also assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² (Higgins 2003) and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if:

the I² value was high (exceeding 30%); and either

there was inconsistency between trials in the direction or magnitude of effects (judged visually), or there was a low P value (< 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity; or

the estimate of between‐study heterogeneity (Tau²) was above zero.

Assessment of reporting biases

As we were not able to pool more than 10 trials, we did not create a funnel plot to explore possible small study biases for the primary outcomes by assessing funnel plot asymmetry visually and by using formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry (Egger 1997; Harbord 2006).

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using RevMan 5 (RevMan 2014). We undertook meta‐analyses only where this was meaningful, that is, the treatments, participants and the underlying clinical questions were similar enough for pooling to make sense.

As previously mentioned, in the case of missing log scale data, we transformed the linear scale mean m and variance v using the following formula: m(log) = log(m) ‐ v(log)/2 and v(log) = log(exp(log(v) ‐ 2log(m)) + 1). We then transformed data to a base of 10 for better readability of data. As all troponin data are presented on a log scale, a value of 1 therefore represents a raw value of 10, a value of 2 represents a raw value of 100 and a value of 0 represents a raw value of 1. Negative values represent raw values between 0 and 1. For transparency, we included the extracted untransformed data from the original studies in additional tables (Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7).

2. 1st Comparison, untransformed data for troponins.

| RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery) | ||||||

| RIPC | No RIPC | |||||

| 1.5 cTnT 6 h after surgery (ng/L) | Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total |

| Candilio 2015 | 614 | 306 | 66 | 780 | 491 | 64 |

| Hausenloy 2007 | 310 | 290 | 27 | 590 | 450 | 30 |

| Hausenloy 2015 | 960.49 | 862 | 580 | 984.54 | 838 | 606 |

| Meybohm 2015 | 870 | 848 | 276 | 879 | 734 | 263 |

| Young 2012 | 1533 | 1784 | 48 | 837 | 547 | 46 |

| 1.6 cTnT 12 h after surgery (ng/L) | ||||||

| Candilio 2015 | 543 | 344 | 66 | 694 | 428 | 64 |

| Hausenloy 2007 | 370 | 190 | 27 | 690 | 480 | 30 |

| Hausenloy 2015 | 859 | 911 | 579 | 887.39 | 748 | 592 |

| Meybohm 2015 | 714 | 820 | 271 | 729 | 761 | 255 |

| Young 2012 | 1608 | 2361 | 48 | 725 | 589 | 46 |

| 1.7 cTnT 24 h after surgery (ng/L) | ||||||

| Meybohm 2015 | 560 | 1146 | 280 | 510 | 588 | 275 |

| Hausenloy 2015 | 695.56 | 949 | 604 | 689 | 657 | 605 |

| Hausenloy 2007 | 300 | 140 | 27 | 520 | 330 | 30 |

| Candilio 2015 | 370 | 213 | 66 | 494 | 304 | 64 |

| 1.8 cTnT 48 h after surgery (ng/L) | ||||||

| Candilio 2015 | 272 | 144 | 65 | 379 | 278 | 63 |

| Hausenloy 2007 | 300 | 170 | 27 | 520 | 490 | 30 |

| Hausenloy 2015 | 588 | 1,566 | 546 | 557 | 592 | 536 |

| Meybohm 2015 | 374 | 520 | 264 | 339 | 317 | 261 |

| 1.9 cTnT 72 h after surgery (ng/L) | ||||||

| Candilio 2015 | 232 | 161 | 63 | 378 | 325 | 63 |

| Hausenloy 2007 | 250 | 160 | 27 | 480 | 640 | 30 |

| Hausenloy 2015 | 440 | 419 | 459 | 501 | 502 | 478 |

| 1.10 cTnT AUC 72 h (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hausenloy 2007 | 20.58 | 9.58 | 27 | 36.12 | 26.08 | 30 |

| Hausenloy 2015 | 32.7 | 0 | 801 | 36.4 | 0 | 811 |

| Venugopal 2009 | 18.16 | 6.67 | 23 | 31.53 | 24.04 | 22 |

| 1.11 cTnI 1 h after surgery (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 65 | 1.19 | 2.06 | 65 |

| Thielmann 2013 | 5.33 | 4 | 162 | 7.24 | 10 | 167 |

| 1.12 cTnI 6 h after surgery (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 1 | 1.68 | 65 | 2.25 | 4.1 | 65 |

| Krawczyk 2011 | 0.62 | 0.43 | 9 | 3.73 | 2.25 | 10 |

| Krawczyk 2012 | 0.78 | 0.55 | 15 | 3.56 | 1.89 | 15 |

| Lomivorotov 2012 | 2.13 | 1.38 | 40 | 2.37 | 2.19 | 40 |

| Meybohm 2015 | 6 | 6 | 104 | 8 | 12 | 108 |

| Saxena 2013 | 10.14 | 7 | 15 | 14.17 | 8 | 15 |

| Thielmann 2013 | 10.78 | 78 | 162 | 12.45 | 17 | 167 |

| 1.13 cTnI 12 h after surgery (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 1.14 | 1.66 | 65 | 1.54 | 2.13 | 65 |

| Krawczyk 2011 | 0.56 | 0.34 | 9 | 4.03 | 2.68 | 10 |

| Krawczyk 2012 | 0.66 | 0.44 | 15 | 3.38 | 2.39 | 15 |

| Meybohm 2015 | 4 | 4 | 103 | 6 | 11 | 112 |

| Saxena 2013 | 4.79 | 2.69 | 15 | 6.55 | 4 | 15 |

| Thielmann 2013 | 8.07 | 5 | 162 | 11.18 | 14 | 167 |

| 1.14 cTnI 24 h after surgery (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 0.76 | 1.2 | 65 | 1.05 | 1.54 | 65 |

| Krawczyk 2011 | 0.42 | 0.23 | 9 | 2.46 | 2.14 | 10 |

| Krawczyk 2012 | 0.42 | 0.23 | 15 | 2.33 | 1.77 | 15 |

| Lomivorotov 2012 | 0.93 | 2.67 | 40 | 0.87 | 1.9 | 40 |

| Meybohm 2015 | 3 | 5 | 114 | 5 | 16 | 108 |

| Saxena 2013 | 2.28 | 2 | 15 | 2.94 | 1 | 15 |

| Thielmann 2013 | 5.41 | 5 | 162 | 7.71 | 9.95 | 167 |

| 1.15 cTnI 48 h after surgery (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 0.61 | 0.92 | 65 | 0.76 | 1.1 | 65 |

| Lomivorotov 2012 | 0.76 | 2.37 | 40 | 0.54 | 1.23 | 40 |

| Meybohm 2015 | 2 | 3.7 | 84 | 2 | 7 | 92 |

| Saxena 2013 | 1.18 | 0.773 | 15 | 1.75 | 0.811 | 15 |

| Thielmann 2013 | 2.94 | 3 | 162 | 4.6 | 7 | 167 |

| 1.16 cTnI 72 h after surgery (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 0.35 | 0.56 | 65 | 0.39 | 0.52 | 65 |

| Thielmann 2013 | 1.55 | 2 | 162 | 2.53 | 4 | 167 |

| 1.17 cTnI AUC 72 h (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 53.2 | 72.9 | 65 | 67.4 | 97.7 | 65 |

| Kottenberg 2014 | 285 | 201 | 15 | 330 | 290 | 14 |

AUC: area under the curve; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; cTnI: cardiac troponin I; cTnT: cardiac troponin T; RIPC: remote ischaemic preconditioning

3. 2nd Comparison, untransformed data for troponins.

| RIPC versus no RIPC (subgroup analysis: isolated CABG without additional surgery) | ||||||

| RIPC | No RIPC | |||||

| Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | |

| 2.2 cTnT 48 h after surgery (ng/L) | ||||||

| Hausenloy 2007 | 300 | 170 | 27 | 520 | 490 | 30 |

| Hausenloy 2015 | 449.017 | 537.042 | 290 | 439.049 | 539.901 | 265 |

| Meybohm 2015 | 308 | 517 | 188 | 295 | 309 | 189 |

| 2.3 cTnT 72 h after surgery (ng/L) | ||||||

| Hausenloy 2007 | 250 | 160 | 27 | 480 | 640 | 30 |

| Hausenloy 2015 | 393.952 | 480.83 | 251 | 391.335 | 431.575 | 233 |

| 2.4 cTnT AUC 72 h (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hausenloy 2007 | 20.58 | 9.58 | 27 | 36.12 | 26.08 | 30 |

| 2.5 cTnI 48 h after surgery (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 0.61 | 0.92 | 65 | 0.76 | 1.1 | 65 |

| Lomivorotov 2012 | 0.76 | 2.37 | 40 | 0.54 | 1.23 | 40 |

| Meybohm 2015 | 1.037 | 1.277 | 64 | 2.308 | 8.167 | 75 |

| Saxena 2013 | 1.18 | 0.773 | 15 | 1.75 | 0.811 | 15 |

| Thielmann 2013 | 2.94 | 3.436 | 162 | 4.6 | 6.849 | 167 |

| 2.6 cTnI 72 h after surgery (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 0.35 | 0.56 | 65 | 0.39 | 0.52 | 65 |

| Thielmann 2013 | 1.55 | 2.418 | 162 | 2.53 | 3.876 | 167 |

| 2.7 cTnI AUC 72 h (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 53.2 | 72.9 | 65 | 67.4 | 97.7 | 65 |

| Kottenberg 2014 | 285 | 201 | 15 | 330 | 290 | 14 |

AUC: area under the curve; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; cTnI: cardiac troponin I; cTnT: cardiac troponin T; RIPC: remote ischaemic preconditioning

4. 3rd Comparison, untransformed data for troponins.

| RIPC versus no RIPC (subgroup analysis in people undergoing CABG, with or without valve surgery and a high preoperative risk status, EuroSCORE ≥ 6) | ||||||

| RIPC | No RIPC | |||||

| Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | |

| 3.2 cTnT 48 h after surgery (ng/L) | ||||||

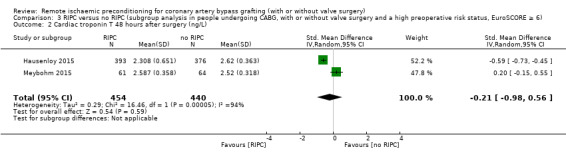

| Hausenloy 2015 | 625.659 | 1822.498 | 393 | 592.255 | 596.452 | 376 |

| Meybohm 2015 | 543 | 536 | 61 | 433 | 365 | 64 |

| 3.3 cTnT 72 h after surgery (ng/L) | ||||||

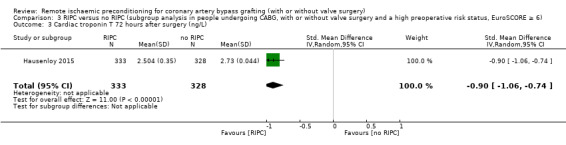

| Hausenloy 2015 | 441.336 | 421.671 | 333 | 538.079 | 54.254 | 328 |

| 3.4 cTnI 48 h after surgery (µg/L) | ||||||

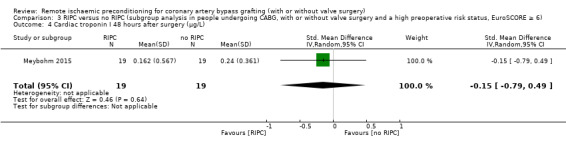

| Meybohm 2015 | 3.409 | 7.224 | 19 | 2.429 | 2.423 | 19 |

AUC: area under the curve; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; cTnI: cardiac troponin I; cTnT: cardiac troponin T; RIPC: remote ischaemic preconditioning

5. 4th Comparison, untransformed data for troponins.

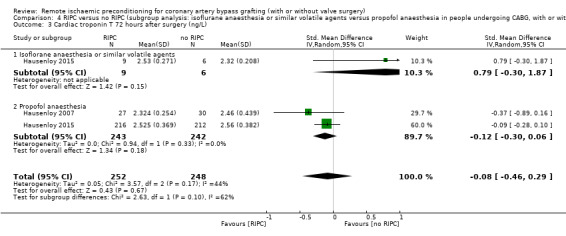

| RIPC versus no RIPC (subgroup analysis: isoflurane anaesthesia or similar volatile agents versus propofol anaesthesia in people undergoing CABG, with or without valve surgery) | ||||||

| RIPC | No RIPC | |||||

| Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | |

| 4.2 cTnT 48 h after surgery (ng/L) | ||||||

| 4.2.1 Isoflurane anaesthesia or similar volatile agents | ||||||

| Hausenloy 2015 | 448.4 | 309.462 | 10 | 304.167 | 127.589 | 6 |

| 4.2.2 Propofol anaesthesia | ||||||

| Hausenloy 2007 | 300 | 170 | 27 | 520 | 490 | 30 |

| Hausenloy 2015 | 578.383 | 652.856 | 256 | 582.749 | 628.337 | 235 |

| Meybohm 2015 | 375 | 525 | 259 | 337 | 318 | 258 |

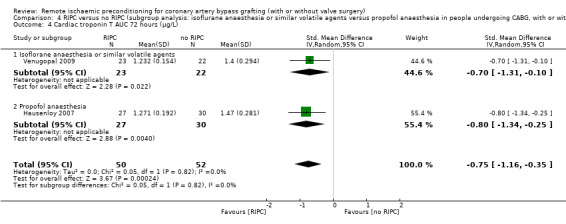

| 4.3 cTnT 72 h after surgery (ng/L) | ||||||

| 4.3.1 Isoflurane anaesthesia or similar volatile agents | ||||||

| Hausenloy 2015 | 411.778 | 283.678 | 9 | 235.333 | 119.652 | 6 |

| 4.3.2 Propofol anaesthesia | ||||||

| Hausenloy 2007 | 250 | 160 | 27 | 480 | 640 | 30 |

| Hausenloy 2015 | 480.421 | 494.477 | 216 | 533.91 | 576.106 | 212 |

| 4.4 cTnT AUC 72 h (µg/L) | ||||||

| 4.4.1 Isoflurane anaesthesia or similar volatile agents | ||||||

| Venugopal 2009 | 18.16 | 6.67 | 23 | 31.53 | 24.04 | 22 |

| 4.4.2 Propofol anaesthesia | ||||||

| Hausenloy 2007 | 20.58 | 9.58 | 27 | 36.12 | 26.08 | 30 |

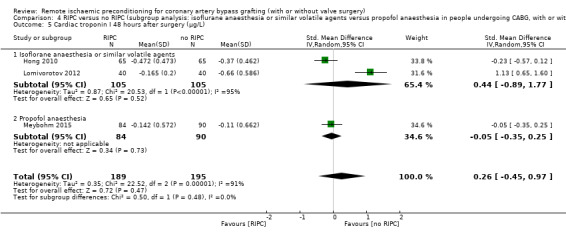

| 4.5 cTnI 48 h after surgery (µg/L) | ||||||

| 4.5.1 Isoflurane anaesthesia or similar volatile agents | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 0.61 | 0.92 | 65 | 0.76 | 1.1 | 65 |

| Lomivorotov 2012 | 0.76 | 0.37 | 40 | 0.54 | 1.23 | 40 |

| 4.5.2 Propofol anaesthesia | ||||||

| Meybohm 2015 | 1.715 | 3.7 | 84 | 2.478 | 7.524 | 90 |

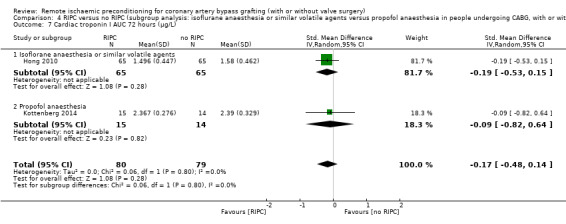

| 4.6 cTnI 72 h after surgery (µg/L) | ||||||

| 4.6.1 Isoflurane anaesthesia or similar volatile agents | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 0.35 | 0.56 | 65 | 0.39 | 0.52 | 65 |

| 4.6.2 Propofol anaesthesia | ||||||

| ‐ | ||||||

| 4.7 cTnI AUC 72 h (µg/L) | ||||||

| 4.7.1 Isoflurane anaesthesia or similar volatile agents | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 53.2 | 72.9 | 65 | 67.4 | 97.7 | 65 |

| 4.7.2 Propofol anaesthesia | ||||||

| Kottenberg 2014 | 285 | 201 | 15 | 330 | 290 | 14 |

AUC: area under the curve; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; cTnI: cardiac troponin I; cTnT: cardiac troponin T; RIPC: remote ischaemic preconditioning

6. 5th Comparison, untransformed data for troponins.

| RIPC versus no RIPC (sensitivity analysis by sequence generation, allocation concealment and incomplete outcome data in patients undergoing CABG, with or without valve surgery) | ||||||

| RIPC | No RIPC | |||||

| Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | |

| 5.2 cTnT 48 h after surgery (ng/L) | ||||||

| Hausenloy 2015 | 587.624 | 1566.324 | 546 | 556.907 | 591.826 | 536 |

| Meybohm 2015 | 374 | 520 | 264 | 339 | 317 | 261 |

| 5.3 cTnT 72 h after surgery (ng/L) | ||||||

| Hausenloy 2015 | 440.166 | 418.592 | 459 | 500.646 | 502.244 | 478 |

| 5.4 cTnI 48 h after surgery (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 0.61 | 0.92 | 65 | 0.76 | 1.1 | 65 |

| Meybohm 2015 | 1.715 | 3.7 | 84 | 2.432 | 7.447 | 92 |

| Thielmann 2013 | 2.94 | 3.436 | 162 | 4.6 | 6.849 | 167 |

| 5.5 cTnI 72 h after surgery (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 0.35 | 0.56 | 65 | 0.39 | 0.52 | 65 |

| Thielmann 2013 | 1.55 | 2.418 | 162 | 2.53 | 3.876 | 167 |

| 5.6 cTnI AUC 72 h (µg/L) | ||||||

| Hong 2010 | 53.2 | 72.9 | 65 | 67.4 | 97.7 | 65 |

AUC: area under the curve; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; cTnI: cardiac troponin I; cTnT: cardiac troponin T; RIPC: remote ischaemic preconditioning

Given the clinical heterogeneity in the modus operandi of RIPC, the heart surgery performed (CABG with or without valve surgery) and during the postoperative course, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary of average treatment effect across trials. We treated the random‐effects summary as the average range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials. We present results as the average treatment effect with its 95% confidence interval, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We identified potential sources of heterogeneity a priori in relation to:

differences in concomitant or no concomitant cardiovascular procedure to CABG (with or without valve surgery);

differences in the number of RIPC cycles or their length;

differences in the localisation of RIPC (upper or lower limb);

differences in surgical techniques (off‐pump versus on‐pump CABG).

However, during the course of this systematic review, no noteworthy differences became apparent between included studies with regard to 1) differences in the number of RIPC cycles or their length; 2) differences in the localisation of RIPC (upper or lower limb); or 3) differences in surgical techniques (off‐pump versus on‐pump CABG) (for a detailed description see Characteristics of included studies and Table 2). Therefore, to explain heterogeneity among study results, we performed three subgroup analyses:

RIPC versus no RIPC (subgroup analysis: isolated CABG without additional surgery);

RIPC versus no RIPC in participants with a high preoperative risk status (EuroSCORE 6 or more) versus no RIPC (CABG with or without valve surgery versus isolated CABG) in participants with a high preoperative risk status (EuroSCORE 6 or more); and

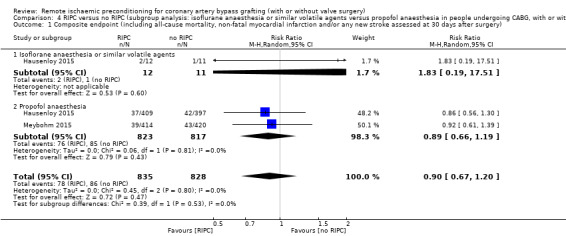

RIPC versus no RIPC (in participants undergoing CABG, with or without valve surgery, subgroup analysis: isoflurane anaesthesia or similar volatile agents versus propofol anaesthesia).

We used random‐effects analysis to produce it and restricted them to the primary outcomes. We used the formal test for subgroup interactions in RevMan 5 (RevMan 2014) and reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² test and P value, and the I² value of the interaction test.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis by limiting analyses to studies at low risk of bias. This was done by excluding studies judged at high or unclear risk of bias for sequence generation, allocation concealment and incomplete outcome data. We give the criteria for these judgements in the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section for each included study. We limited sensitivity analyses to primary outcomes (see Types of outcome measures).

Reaching conclusions

We based our conclusions only on findings from the quantitative or narrative synthesis of included studies for this review. We avoided making recommendations for practice and our implications for research suggest priorities for future research and outline what the remaining uncertainties are in the area.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies as well as overview of baseline characteristics of included studies (Additional tables).

Results of the search

We performed the database searches in May 2016 and identified 700 citations with potential for inclusion. We had knowledge of two additional, recently published possibly matching studies (Gallagher 2015; Zarbock 2015) on RIPC that were not included in the initial search results and a further nine were identified through other sources. After removal of duplicates, we excluded 321 citations during the initial screening of titles and abstracts. Nine studies were ongoing at the time of this review, and results were not yet published; we contacted the study authors. Those that responded wished to withhold results until after publication (see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Overall, we assessed 76 records on the basis of a full‐text review. We found seven studies (Candilio 2015; Meybohm 2015; Walsh 2016; Young 2012; Zarbock 2015; Zimmerman 2011; Zitta 2014 (Meybohm 2013) that randomised people scheduled CABG with or without valve surgery and valve surgery alone, which does not correspond with our inclusion criteria. However, we contacted the study authors to ask if they could provide data on CABG with or without valve surgery only. Of these, three studies (Candilio 2015; Meybohm 2015; Young 2012) provided data sets excluding valve‐only participants from the analysis and were therefore included in our review. The authors of Zitta 2014 (Meybohm 2013) informed us that the study is a subgroup analysis as part of the pilot study Meybohm 2013. The authors of the remaining three studies (Walsh 2016; Zarbock 2015; Zimmerman 2011) did not respond. In total 22 studies failed to meet the inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of excluded studies) and one study is awaiting classification (Gasparovic 2014a). Thus, 29 studies (reported in 50 publications) are included in this review (please refer to the PRISMA chart for overview of the selection process, Figure 1).

Included studies

A total of 29 RCTs are included in this review (Ahmad 2014; Ali 2010; Candilio 2015; Gallagher 2015; Gegouskov 2009; Günaydin 2000; Hausenloy 2007; Hausenloy 2015; Hong 2010; Joung 2013; Karuppasamy 2011; Kottenberg 2014; Krawczyk 2010; Krawczyk 2011; Krawczyk 2012; Krogstad 2015; Lomivorotov 2012; Lucchinetti 2012; Meybohm 2013; Meybohm 2015; Rahman 2010; Saxena 2013; Shmyrev 2011; Slagsvold 2014; Sosorburam 2014; Thielmann 2013; Venugopal 2009; Yildirim 2016; Young 2012). We provided detailed descriptions of these individual studies in the Characteristics of included studies tables. These studies involved 5392 participants (mean age = 64 years, age range 23 to 86 years, 82% male) randomly assigned to either receive remote ischaemic preconditioning or sham remote ischaemic preconditioning before cardiac surgery. All trials that met the inclusion criteria used a standard parallel‐group design. For a detailed account of the criteria required for inclusion, see Criteria for considering studies for this review. Six citations (Gegouskov 2009; Krawczyk 2010; Krawczyk 2011; Krawczyk 2012; Shmyrev 2011; Sosorburam 2014) referred only to an abstract. We contacted the study authors (if contact details were obtainable) to get further information on the studies, but they did not respond. We also contacted the authors of three studies (Lomivorotov 2012; Thielmann 2013; Young 2012), who provided us with additional information, as in their final reports data were only presented as a graph, and absolute figures (e.g. on troponin values) were missing.

The majority of studies were single‐centre studies. Only two studies were performed as multicentre trials (Hausenloy 2015, Meybohm 2015). Most studies were performed in Europe (seven studies in the UK (Candilio 2015; Gallagher 2015; Hausenloy 2007; Hausenloy 2015; Karuppasamy 2011; Rahman 2010; Venugopal 2009), five studies in Germany (Gegouskov 2009; Kottenberg 2014; Meybohm 2013; Meybohm 2015; Thielmann 2013), three studies in Poland (Krawczyk 2010; Krawczyk 2011; Krawczyk 2012), two studies in Turkey (Günaydin 2000; Yildirim 2016), two studies in Norway (Krogstad 2015; Slagsvold 2014)). The other studies were performed in North America, Australia and in Asia (one study each in Canada (Lucchinetti 2012), Australia (Saxena 2013) and New Zealand (Young 2012); two studies each in Pakistan (Ahmad 2014; Ali 2010), Korea (Hong 2010; Joung 2013), and Russia (Lomivorotov 2012; Shmyrev 2011)). Only half of the studies provided details on funding (e.g. institutional funding or funding by an independent Health Department or Research Foundation). No study reported details that would raise concern for bias with regard to funding.

The sample size in the included studies ranged from eight participants (Günaydin 2000) to 1612 participants (Hausenloy 2015). Most studies did not perform a power analysis. We noted a large gender imbalance across all studies in favour of male participants, ranking only from 0% (Günaydin 2000) to 31% (Hong 2010) of participants being female. The majority of studies included people scheduled for isolated CABG (Hong 2010; Joung 2013; Karuppasamy 2011; Kottenberg 2014; Krawczyk 2010; Krawczyk 2011; Krawczyk 2012; Krogstad 2015; Lomivorotov 2012; Lucchinetti 2012; Rahman 2010; Saxena 2013; Shmyrev 2011; Slagsvold 2014; Sosorburam 2014; Thielmann 2013; Yildirim 2016), seven studies (Candilio 2015; Gallagher 2015; Hausenloy 2015; Meybohm 2013; Meybohm 2015; Venugopal 2009; Young 2012) also included participants with combined procedures (CABG with or without valve surgery). Only a minority was performed as off‐pump procedure (Hong 2010; Joung 2013; Krawczyk 2010; Krawczyk 2011; Krawczyk 2012).

RIPC was performed almost exclusively on the right or left upper arm; only one included study (Candilio 2015) chose a mixed approach and performed RIPC on the upper arm and the upper thigh. The number of cycles of RIPC carried out ranked from two to four cycles, with two studies (Candilio 2015; Günaydin 2000) performing only two cycles of RIPC and six studies (Hausenloy 2015; Hong 2010; Joung 2013; Lucchinetti 2012; Meybohm 2013; Meybohm 2015) performing four cycles of RIPC. All other studies executed three cycles of RIPC. The majority of studies applied 200 mmHg pressure during one cycle of RIPC, two studies applied 300 mmHg (Günaydin 2000; Lucchinetti 2012) and one study specified that they would apply 20 mmHg above systolic blood pressure (Saxena 2013). The control intervention was in most cases a deflated cuff around the forearm, two studies (Hausenloy 2015; Hong 2010) simulated RIPC by inflating the cuff with the valve open, three studies used a dummy arm (Meybohm 2015; Rahman 2010; Young 2012). Eight studies (Ali 2010; Gegouskov 2009; Krawczyk 2010; Krawczyk 2011; Krawczyk 2012; Saxena 2013; Shmyrev 2011; Sosorburam 2014) did not report which anaesthetic gas was used during surgery. In the remaining studies, propofol anaesthesia and isoflurane anaesthesia was used equally often or a mixed approach was chosen.

Only three of the included studies considered the skew distribution of troponin values (Hausenloy 2015, Thielmann 2013, Young 2012). Due to the variation of outcomes assessed in cardiac trials and inconsistency in outcome definition and reporting (Benstoem 2015b) none of the included studies contributed data to all of the outcomes assessed in this systematic review. Two studies (Hausenloy 2015; Meybohm 2015) performed a secondary analysis tailored to the needs of this systematic review. If we needed to convert data in order to include them in one of the meta‐analyses, we described this in detail in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Excluded studies

Overall, we excluded 22 studies during the full‐text screening process. Ten studies were systematic reviews, five studies were laboratory tissue studies, four studies assessed a different study population, and three studies used a different intervention. The Characteristics of excluded studies provides full details of the excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias varied across included studies, and insufficient detail was provided to inform judgement in several included studies (see Figure 2, 'Risk of bias' summary table, and Figure 3, 'Risk of bias' graph, for an overview).

Allocation

We judged 13 included studies (Candilio 2015; Hausenloy 2015; Hong 2010; Joung 2013; Kottenberg 2014; Krogstad 2015; Lucchinetti 2012; Meybohm 2015; Rahman 2010; Slagsvold 2014; Thielmann 2013; Venugopal 2009; Young 2012) as having low risk of bias in random sequence generation. Information was insufficient to permit a decision in with regard to 15 trials. We rated one study as having high risk of bias (Ali 2010).

With regard to allocation concealment, we judged 13 studies (Ali 2010; Candilio 2015; Hausenloy 2015; Hong 2010; Kottenberg 2014; Krogstad 2015; Lucchinetti 2012; Meybohm 2013; Meybohm 2015; Rahman 2010; Slagsvold 2014; Thielmann 2013; Young 2012) as having low risk of bias. The remaining 16 studies provided insufficient information on which to base judgements.

Blinding

With regard to performance bias, we judged 14 studies (Candilio 2015; Gallagher 2015; Hausenloy 2007; Hausenloy 2015; Karuppasamy 2011; Krogstad 2015; Lucchinetti 2012; Meybohm 2013; Meybohm 2015; Rahman 2010; Saxena 2013; Thielmann 2013; Yildirim 2016; Young 2012) as having low risk of bias and one study as having high risk of bias (Ali 2010). The the remaining 14 studies provided insufficient information on which to base judgements.

As a result of the nature of the objective outcomes assessed in included studies (e.g. not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding e.g. cardiac troponin T (cTnT), cardiac troponin I (cTnI), etc.) we do not expect detection bias to have greater impact on study results, especially as we did not assess many possibly subjective outcomes that were likely to be influenced by lack of blinding (e.g. “Any patient‐centred/salutogenic‐focused outcome, as reported in included studies”), combining results in meta‐analyses was not meaningful and therefore not done. However, we only rated 12 studies (Ali 2010; Candilio 2015; Hausenloy 2015; Hong 2010; Kottenberg 2014; Krogstad 2015; Lucchinetti 2012; Meybohm 2015; Slagsvold 2014; Thielmann 2013; Yildirim 2016, Young 2012) as low risk of bias, as the level of reporting of whether outcome assessment was blinded was relatively poor across studies. We judged one study as having high risk of bias (Gallagher 2015) and the remaining 16 studies provided insufficient information on which to base judgements.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged 18 studies (Ahmad 2014; Ali 2010; Gallagher 2015; Günaydin 2000; Hausenloy 2007; Hausenloy 2015; Hong 2010; Karuppasamy 2011; Krogstad 2015; Lomivorotov 2012; Lucchinetti 2012; Meybohm 2015; Rahman 2010; Saxena 2013; Slagsvold 2014; Thielmann 2013; Venugopal 2009; Yildirim 2016) as having low risk of attrition bias and three studies as having high risk: 29% of participants dropped out of Joung 2013; 21% of participants dropped out of Kottenberg 2014; and 27% of participants dropped out of Meybohm 2013. Information was insufficient on which to base judgements in the remaining eight studies.

Selective reporting

We found no trial registration protocol for most studies to confirm whether all prespecified outcomes were reported in the publication. For two included studies (Hausenloy 2015, Meybohm 2015) a study protocol was available. However, outcomes listed in the methods section of the included studies were reported in the results section, with the exception of two studies that we judged to have high risk of reporting bias (i.e. Günaydin 2000 who did not report lactate, PO2 and pH values; and Slagsvold 2014 who did not report troponin T values for all prespecified time points). As we were not able to pool more than 10 trials, we did not include funnel plots in this review.

Other potential sources of bias

For most studies (Ahmad 2014; Ali 2010; Gegouskov 2009; Günaydin 2000; Joung 2013; Kottenberg 2014; Krawczyk 2010; Krawczyk 2011; Krawczyk 2012; Lucchinetti 2012; Shmyrev 2011; Sosorburam 2014; Thielmann 2013; Young 2012), information was insufficient on which to base judgements for low risk of bias. However, we rated one study (Hong 2010) as high risk of bias for other potential sources of bias, as the authors stated that, although the study was planned with 80 participants, during the course of the study it was decided to include another 50 participants "to increase power", which might have had impact on the study results.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See Table 1 for the comparison RIPC before CABG (with or without valve surgery) versus no RIPC before CABG (with or without valve surgery).

RIPC versus no RIPC (in participants undergoing CABG, with or without valve surgery)

For this comparison, we included all participants scheduled for CABG with or without valve surgery who were randomly assigned in the included studies and received either RIPC or no RIPC. We did not include study data on participants scheduled for isolated valve surgery (see Characteristics of included studies tables for details). We also undertook three subgroup analyses as discussed in the Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity section.

Primary outcomes

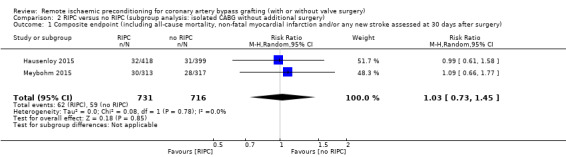

Composite endpoint (including all‐cause mortality, non‐fatal myocardial infarction and/or any new stroke) assessed at 30 days after surgery

Among the 29 trials that met the inclusion criteria of the meta‐analysis, only two (Hausenloy 2015; Meybohm 2015) made an attempt to measure the overall treatment effect by means of a composite endpoint. However, in their initial study reports the composite endpoint was not defined uniformly (ERICCA trial: death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, coronary revascularisation, or stroke, assessed 12 months after randomisation (Hausenloy 2015); and RipHEART study: death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or acute renal failure up to the time of hospital discharge (Meybohm 2015)) and a secondary analysis (unpublished, exclusively performed for this systematic review) provided the data for this meta‐analysis. Participants randomised to receive RIPC had, on average, no difference in the rate of the composite endpoint when compared to participants allocated to the control group with RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.25); 2 studies; 2463 participants; I2 = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence, Analysis 1.1. A detailed description of grading the evidence is presented in the Table 1). For this outcome, we did not observe statistical heterogeneity.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 1 Composite endpoint (including all‐cause mortality, non‐fatal myocardial infarction and/or any new stroke assessed at 30 days after surgery).

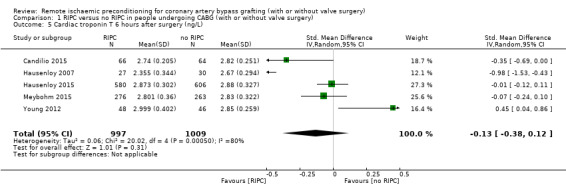

cTnT after CABG (ng/L) at 48 hours, 72 hours, and as area under the curve (AUC) 72 hours (µg/L) after surgery

A total of four trials measured cTnT 48 hours after CABG, with or without valve surgery. We found that, on average, the amount of cTnT released at 48 hours after surgery was not reduced among participants allocated to RIPC compared with those allocated to no RIPC with SMD ‐0.14 (95% CI ‐0.33 to 0.06); 4 studies; 1792 participants; I2 = 64%; low‐quality evidence, Analysis 1.8. However, measured at 72 hours after CABG, we found that participants randomised to receive RIPC showed, on average, an equivalent or better effect regarding the amount of cTnT release with SMD ‐0.32 (95% CI ‐0.65 to 0.00); 3 studies; 1120 participants; I2 = 68%; moderate‐quality evidence, Analysis 1.9. Also cTnT release measured as the AUC (72 hours) showed, on average, the same result in favour of RIPC with SMD ‐0.49 (95% CI ‐0.96 to ‐0.02); 3 studies; 830 participants; I2 = 73%; moderate‐quality evidence, Analysis 1.10. Heterogeneity identified was substantial for Analysis 1.8, Analysis 1.9 and Analysis 1.10, as Tau² was greater than zero, and in all cases, I² was greater than 30% and the P value for the Chi² test was less than 0.10. We undertook subgroup and sensitivity analyses to try to explore heterogeneity; although findings are presented later, they did not explain the high level of heterogeneity.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 8 Cardiac troponin T 48 hours after surgery (ng/L).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 9 Cardiac troponin T 72 hours after surgery (ng/L).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 10 Cardiac troponin T AUC 72 hours (µg/L).

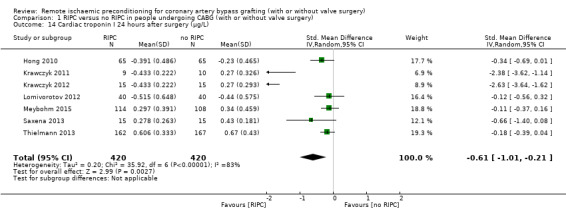

cTnI after CABG (ng/L) at 48 hours, 72 hours, and as AUC 72 hours (µg/L) after surgery

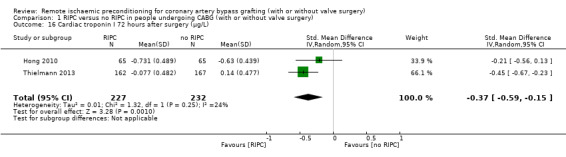

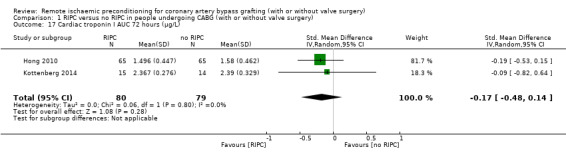

A total of five trials measured cTnI 48 hours after CABG, with or without valve surgery. We found that participants randomised to receive RIPC showed, on average, a benefit regarding the amount of cTnI release after 48 hours with SMD ‐0.21 (95% CI ‐0.40 to ‐0.02); 5 studies; 745 participants; I2 = 31%; moderate‐quality evidence, Analysis 1.15. The analysis showed that cTnI measured at 72 hours with SMD ‐0.37 (95% CI ‐0.59 to ‐0.15); 2 studies; 459 participants; I2 = 24%; moderate‐quality evidence Analysis 1.16, on average, was also reduced in favour of RIPC. In contrast, measured as AUC (72 hours) after surgery with SMD ‐0.17 (95% CI ‐0.48 to 0.14); 2 studies; 159 of participants; I2 = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence, Analysis 1.17, the analysis showed, on average, no difference among participants. The troponin I analyses measured at 48 hours and as AUC (72 hours) showed moderate presence of heterogeneity in the results obtained.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 15 Cardiac troponin I 48 hours after surgery (µg/L).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 16 Cardiac troponin I 72 hours after surgery (µg/L).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 17 Cardiac troponin I AUC 72 hours (µg/L).

Secondary outcomes

All‐cause mortality after 30 days

A total of eight studies measured all‐cause mortality 30 days after surgery. On average, no difference with regard to mortality after 30 days was reported among participants randomised to receive RIPC compared with those randomised to no RIPC with RR 1.05 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.68); 8 studies; 3288 participants; I2 = 0%, Analysis 1.2.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 2 All‐cause mortality after 30 days.

Non‐fatal myocardial infarction after 30 days

Two studies reported on the number of non‐fatal myocardial infarction after 30 days. On average, there was no difference regarding this secondary outcome between both groups with RR 0.84 (95% CI 0.62 to 1.15); 2 studies; 2463 participants; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.3.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 3 Non‐fatal myocardial infarction after 30 days.

Any new stroke after 30 days

Similar to non‐fatal myocardial infarction after 30 days, we found, on average, no difference in the number of new strokes after 30 days among participants allocated to the intervention or the comparison group with RR 1.12 (95% CI 0.60 to 2.07); 2 studies; 2463 participants; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.4.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 4 Any new stroke after 30 days.

Acute renal failure after 30 days

Only one study reported on acute renal failure after 30 days. We observed no difference between the two study groups with RR 1.37 (95% CI 0.78 to 2.40); 1 study; 851 participants; I2 not applicable; Analysis 1.18.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 18 Acute renal failure after 30 days.

Length of stay on the intensive care unit (days)

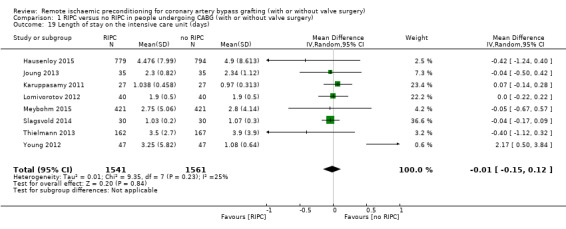

Eight studies reported on the duration of ICU stay after CABG, with or without valve surgery. On average, no difference with regard to ICU duration was reported among participants allocated to RIPC compared with those allocated to no RIPC with MD ‐0.01 (95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.12); 8 studies; 3102 participants; I2 = 25%; Analysis 1.19.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 19 Length of stay on the intensive care unit (days).

Any complications and adverse effects related to ischaemic preconditioning, as reported by trial authors

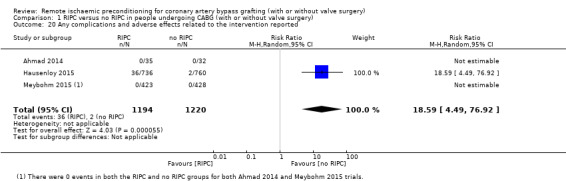

Overall, only three studies reported adverse effects related to RIPC. Two studies observed no adverse effects, neither in the intervention nor in the control group. One study observed significantly more events (skin petechiae exclusively) in the intervention group than in the control group with RR 18.59 (95% CI 4.49 to 76.92); 3 studies; 2414 participants; I2 not applicable; Analysis 1.20.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 20 Any complications and adverse effects related to the intervention reported.

Any patient‐centred/salutogenic‐focused outcome, as reported in included studies

Included studies did hardly assess patient‐centred/salutogenic‐focused outcomes. Only one study assessed health‐related quality of life as measured by the European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions score at baseline, 6 weeks, and 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months (Hausenloy 2015). They found no difference between groups with regard to quality of life. No other patient‐centred or salutogenic‐focused outcome was evaluated. Therefore, we were not able to pool data by means of meta‐analysis.

cTnT after CABG (ng/L) at 6 hours, 12 hours, and 24 hours after surgery

A total of five studies measured cTnT at 6 hours after surgery, with SMD ‐0.13 (95% CI ‐0.38 to 0.12); 5 studies; 2006 participants; I2 = 80%, Analysis 1.5; and at 12 hours after surgery, with SMD ‐0.14 (95% CI ‐0.40 to 0.13); 5 studies; 1978 participants; I2 = 82%, Analysis 1.6; and a total of four studies at 24 hours after surgery, with SMD ‐0.25 (95% CI ‐0.50 to 0.01); 4 studies; 1951 participants; I2 = 80%, Analysis 1.7, but did not find, on average, a benefit in the amount of cTnT released. In all three meta‐analyses, we identified substantial statistical heterogeneity.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 5 Cardiac troponin T 6 hours after surgery (ng/L).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 6 Cardiac troponin T 12 hours after surgery (ng/L).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 7 Cardiac troponin T 24 hours after surgery (ng/L).

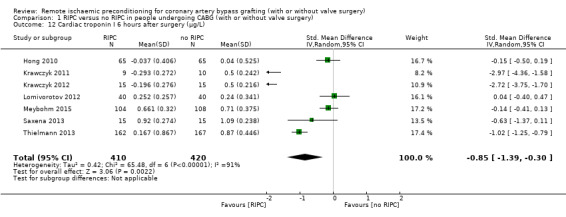

cTnI after CABG (ng/L) at 6 hours, 12 hours, and 24 hours after surgery

A total of seven studies measured cTnI at 6 hours after surgery, with SMD ‐0.85 (95% CI ‐1.39 to ‐0.30); 7 studies; 830 participants; I2 = 91%, Analysis 1.12; six studies at 12 hours after surgery, with SMD ‐0.89 (95% CI ‐1.42 to ‐0.36); 6 studies; 753 participants; I2 = 89%, Analysis 1.13; and seven studies at 24 hours after surgery, with SMD ‐0.61 (95% CI ‐1.01 to ‐0.21); 7 studies; 840 participants; I2 = 83%, Analysis 1.14, and did find, on average, a difference in the amount of cTnI released. In all three meta‐analyses, we identified substantial statistical heterogeneity.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 12 Cardiac troponin I 6 hours after surgery (µg/L).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 13 Cardiac troponin I 12 hours after surgery (µg/L).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 RIPC versus no RIPC in people undergoing CABG (with or without valve surgery), Outcome 14 Cardiac troponin I 24 hours after surgery (µg/L).

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

RIPC versus no RIPC (subgroup analysis: isolated CABG without additional surgery)