Abstract

Objective/background

Increasingly, reports show that compliance rates with endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) surveillance are often suboptimal. The aim of this study was to determine the safety implications of non-compliance with surveillance.

Methods

The study was carried out according to the Preferred Items for Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. An electronic search was undertaken by two independent authors using Embase, MEDLINE, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases from 1990 to July 2017. Only studies that analysed infrarenal EVAR and had a definition of non-compliance described as weeks or months without imaging surveillance were analysed. Meta-analysis was carried out using the random-effects model and restricted maximum likelihood estimation.

Results

Thirteen articles (40,730 patients) were eligible for systematic review; of these, seven studies (14,311 patients) were appropriate for comparative meta-analyses of mortality rates. Three studies (8316 patients) were eligible for the comparative meta-analyses of re-intervention rates after EVAR and four studies (12,995 patients) eligible for meta-analysis for abdominal aortic aneurysm related mortality (ARM). The estimated average non-compliance rate was 42.0% (95% confidence interval [CI] 28–56%). Although there is some evidence that non-compliant patients have better survival rates, there was no statistically significant difference in all cause mortality rates (year 1: odds ratio [OR] 5.77, 95% CI 0.74–45.14; year 3: OR 2.28, 95% CI 0.92–5.66; year 5: OR 1.81, 95% CI 0.88–3.74) and ARM (OR 1.47, 95% CI 0.99–2.19) between compliant and non-compliant patients in the first 5 years after EVAR. The re-intervention rate was statistically significantly higher in compliant patients from 3 to 5 years after EVAR (year 1: OR 6.36, 95% CI 0.23–172.73; year 3: OR 3.94, 85% CI 1.46–10.69; year 5: OR 5.34, 95% CI 1.87–15.29).

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that patients compliant with EVAR surveillance programmes may have an increased re-intervention rate but do not appear to have better survival rates than non-compliant patients.

Keywords: Abdominal aortic aneurysm, Endovascular procedures, Epidemiology, Meta-analysis, Review, Stents

Introduction

Despite endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) being the modern preferred first choice for repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA),1,2 studies show that re-interventions after EVAR are common and are undertaken in around 20% of patients within 5 years.3,4 Consequently, guidelines from learned societies recommend lifelong annual imaging in order to identify and treat aortic complications to prevent aneurysm rupture and death.5–7 However, published population and observational studies show that patients are not always compliant with their surveillance programmes.8,9 A number of studies have attempted to evaluate patient characteristics that may be associated with poor compliance rates.8,10 Despite this, little is known about the consequence of non-compliance with surveillance. Thus, a systematic review and meta-analysis was undertaken to study the implications of non-compliance with EVAR surveillance programmes. The primary outcomes were overall compliance, all cause mortality (ACM), and re-intervention rates and the secondary outcome was aneurysm related mortality (ARM).

Methods

The study was carried out according to the Preferred Items for Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.11 An electronic search was undertaken by two independent authors using the Embase, Medline, and Cochrane databases from 1990 to July 2017. Studies that assessed the compliance rate with surveillance after EVAR and analysed the relationship of re-intervention and mortality rates with compliance rates were identified. The search terms (including medical subject sub-headings) “abdominal aortic aneurysm”,“aneurysm”,“AAA”,“EVAR”,“endovascular repair”, “compliance”, “surveillance”, “follow-up”, and “survey” were used in combination with Boolean operators AND or OR. The reference lists of articles obtained were investigated to identify relevant citations. Conference abstracts from major vascular meetings, when published online, were also scrutinised through the Web of Science database (full search history is available in the Supplementary Material).

Inclusion criteria encompassed all studies describing endovascular repair of infrarenal AAA. The studies needed to have a definition of non-compliance described as weeks or months without imaging surveillance. Exclusion criteria included non-English language papers, thoraco-abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, suprarenal AAA, fenestrated grafts, parallel grafts, iliac aneurysms, and patients treated with the endovascular aneurysm sealing technique.

Studies that provided follow-up data using statistical methods for survival analysis were used for comparative meta-analyses of ACM and re-intervention rates. Quality assessment was carried out independently by two authors using Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE),12 and differences were resolved through discussion between the two authors. Outcome data were obtained from at risk scores provided with the tables and graphs when available, but if not, data were extracted from Kaplane–Meier curves. Attempts were made to contact the authors whenever data required were not readily available.

ARM was standardised by Chaikof et al. as deaths secondary to aneurysm rupture, EVAR to open conversion, and the index or secondary procedure (see Table 7).13

Table 7. Aneurysm related mortality (ARM), overall data, and definitions of ARM.

| Study | Compliant patients | Non-compliant patients | Definition | Length of follow-up (y) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients (n) | Mortality (n) | Total number of of patients (n) | Mortality (n) | |||

| Garg et al.19 | 3944 | 24 | 3944 | 13 | “Aneurysm related in hospital mortality” | 10 |

| Sarangarm et al.42 | 107 | 3 | 19 | 0 | “[D]ied from post-EVAR open conversion complications” | 7 |

| Leurs et al.41 | 1538 | 21 | 2895 | 26 | “[D]eaths due to aneurysm rupture, a primary or secondary procedure, or surgical conversion” | 7 |

| Waduud et al.20 | 301 | 8 | 247 | 8 | “AAA related death” | 5 |

Note. EVAR = endovascular aneurysm repair; AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm.

As different institutions and studies used different definitions for non-compliance, a laxity index was developed by the authors at the outset of the study. The laxity index is a measure of the stringency of the studies’ definition of non-compliance. The laxity index was based on the number of scans missed and the number of months without imaging. A laxity value (from 0 to 1) was attributed to studies. A low laxity index suggests a very rigid application of the surveillance protocol, such that minimal deviation was labelled as non-compliance (detailed explanation is available in the Supplementary Material).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using ‘R package meta-for’. Random effects meta-analyses were performed using restricted maximum likelihood estimation.14 The meta-analysis for the non-compliance rates was performed using the observed rates and standard methods for a non-comparative proportion. For four of the papers,8,15–17 reported longer-term compliance rates were used to determine the necessary outcome data.

The comparative meta-analyses of ACM and re-intervention rates were performed at five time points (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years) after intervention. The outcome data were empirical log-odds ratios (ORs) that compare the all cause mortality and re-intervention rates of the compliant and non-compliant patients. In order to include outcome data where Kaplane–Meier curves indicated that the event rate was negligible, the corresponding outcome data were analysed using the rate where half a person had experienced the event. Random effects meta-analyses were done using standard methods, where a conservative sample size was used for calculating the within study variances, so that censoring resulted in the maximum possible loss of information.18 This sample size calculation requires the number at risk at each time point. Most papers gave these or values at adjacent time points that could be used for interpolation. Where numbers at risk were not given in study reports, for the purposes of calculating within study variances, the sample sizes were reduced by the average percentage reduction across the other studies that contribute to the analysis. Pooled estimates were transformed to the OR scale, where an OR that is > 1 indicates that the mortality or re-intervention rate is higher in compliant patients. To account for confounding factors, matched cohorts were used where possible. This included the studies by Garg et al. and Hicks et al. for comparative meta-analyses of mortality,16,19 and the study by Garg et al. for comparative meta-analyses of re-intervention rates.19

Five random effects meta-regression models were fitted where the overall survival log-ORs were regressed on the laxity index. Here the regression coefficient is a log-OR that is associated with a change in the laxity index from its minimum (0) to its maximum (1). A positive regression coefficient indicates that a greater laxity index is associated with larger ORs. A single comparative meta-analysis of the rates of ARM was performed. Here a random effects meta-analysis was performed, using empirical log-ORs as outcome data, and as in the other comparative meta-analyses.

For three studies,16,20,21 Kaplane–Meier curves for “non-compliant” groups and “lost to follow-up” were provided separately. It was agreed that, although the “lost to follow-up” group is a more non-compliant group, this particular survival curve would not be analysed for meta-analysis. This decision was taken as this provides a more conservative analysis and avoids statistical issues involved in reconstructing Kaplane–Meier curves de novo (which would be a combination of non-compliant and lost to follow-up). Thus, the results produced will be more transparent and easily reproducible.

Elective and emergency cases of AAA repair could not be distinguished to statistically assess the impact of survival and re-intervention rate. Thus, the statistical outcomes do not refer to elective or rupture patients independently.

In the study by Hicks et al.,16 an assumption was agreed by the authors, whereby patients who had telephone follow-up were considered as non-compliant, whereas patients who attended clinic for follow-up were considered as compliant. This was done in order to resemble the current real world scenario where patients physically attend follow-up sessions. Given that the recorded follow up in the Vascular Quality Initiative register is only for 1 year after EVAR, a sensitivity analysis for all cause mortality excluding the study by Hicks et al. was carried out.16

Results

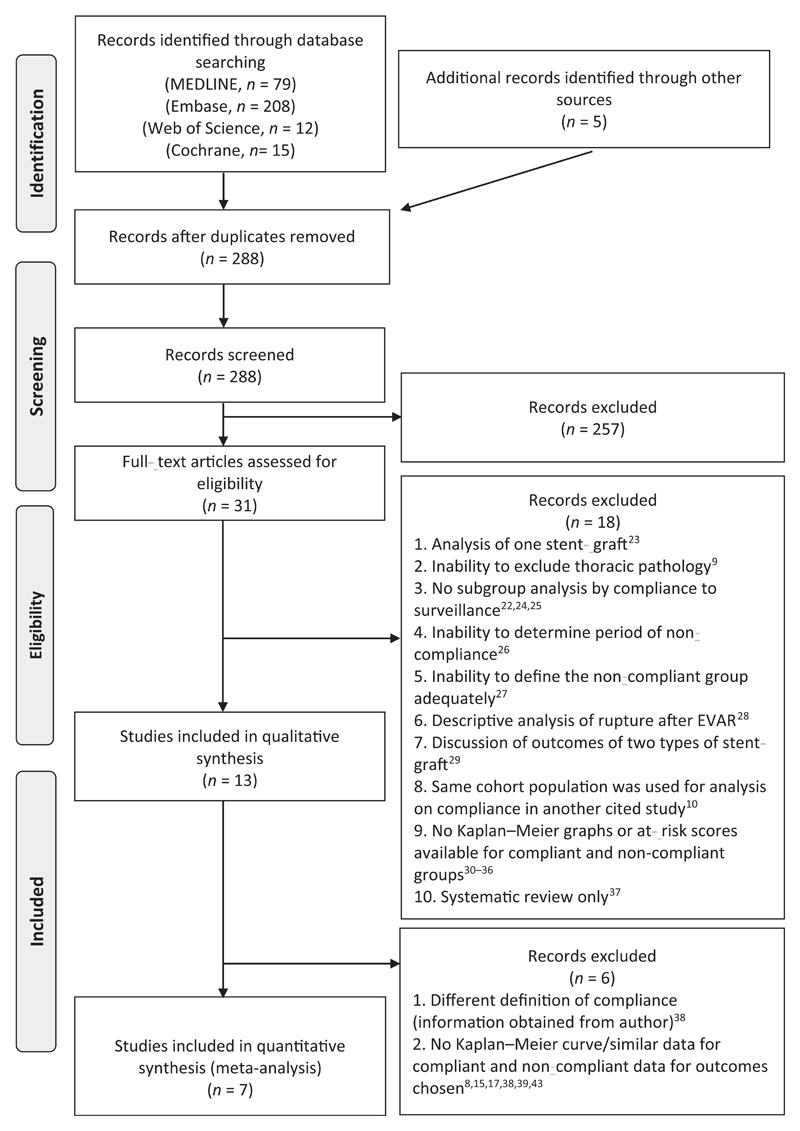

After screening, the literature search identified 31 articles that discussed compliance after EVAR. Of these 31 articles, 18 were excluded for various reasons (Fig. 1).9,10,22–37 Of the 13 articles that were suitable for systematic review,8,15–17,19–21,38–43 seven studies were eligible for comparative meta-analysis of ACM.16,19–21,40–42 Three were eligible for comparative meta-analyses of re-intervention rates after EVAR,19,40,42 whereas four studies were eligible for random effects meta-analyses of ARM.19,20,41,42 The study by God-frey et al.,38 despite providing a survival analysis curve, was not eligible for inclusion in meta-analysis owing to a different definition of non-compliance as compared with other papers. This was confirmed when the corresponding author was contacted.

Figure 1.

Preferred Items for Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart.

Note. EVAR = endovascular aneurysm repair.

Primary outcomes

Compliance

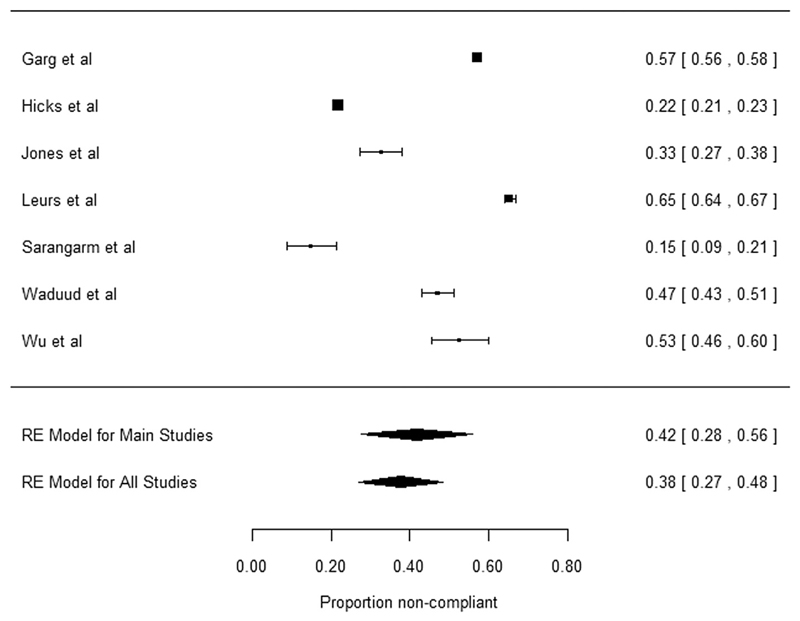

Using the seven studies that contributed to the comparative meta-analysis, the estimated average non-compliance rate (according to the papers’ specific criteria for determining this) was 42% (95% confidence interval [CI] 28–56% [26,622 patients: 15,255 compliant; 11,367 non-compliant]) (Fig. 2). This finding is consistent even if the non-compliance rates of the other four studies were included, where the non-compliance rate was 38% (95% CI 27–48%), (40,730 patients: 22,971 compliant; 17,759 non-compliant) (Fig. 2, Table 1). Overall quality of evidence is “moderate” (Table 2).12

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of proportions of non-compliance. Meta-analysis of proportions of non-compliance to endovascular aneurysm repair surveillance using data from the seven studies eligible for comparative meta-analysis, termed “main studies”, was carried out. An overall meta-analysis of proportions of non-compliance using the data from all the studies in the systematic review (even if not eligible for comparative meta-analysis) was carried out. The overall result is shown next to the “model for all studies”.

Table 1. Meta-analysis of proportions, along with definitions of, non-compliance and the overall compliant and non-compliant numbers in each study.

| Study | Definition of non-compliance | Total number of patients | Non-compliant patients (n) | Compliant patients (n) | Main study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schanzer et al.8 | Defined as “prolonged time period”: a patient who did not undergo at least one imaging study during each 2 y interval that they were alive after EVAR | 7666 | 3879 | 3787 | No |

| Godfrey et al.38 | No imaging within the preceding 12 months (±2 months) of the surveillance visits | 179 | 50 | 129 | No |

| Dias et al.15 | Non-attendance at yearly CT scans | 279 | 5 | 274 | No |

| Aburahma et al.39 | No follow-up imaging (CT and/or DUS) for 2 y at any time during follow-up and/or missed first post-EVAR imaging over 6 mo | 565 | 323 | 242 | No |

| Cohen et al.43 | Not compliant to follow-up protocol: 30 d, 1 y, and annual follow-up | 517 | 92 | 425 | No |

| De Mestral et al.17 | Defined as “minimum appropriate imaging follow-up”: CT scan or an ultrasound of the abdomen within 90 d of EVAR and every 15 mo thereafter | 4902 | 2043 | 2859 | No |

| Garg et al.19 | Defined as “incomplete surveillance” if surveillance gaps between images was longer than 15 mo | 9695 | 5526 | 4169 | Yes |

| Jones et al.40 | Any patient who missed > 2 consecutive follow-up office visits | 302 | 99 | 203 | Yes |

| Leurs et al.41 | Patients missing ≥ 1 follow-up appointments | 4433 | 2895 | 1538 | Yes |

| Sarangarm et al.42 | Any patient who missed ≥ 2 consecutive follow-up office visits | 126 | 19 | 107 | Yes |

| Waduud et al.20 | Patients who underwent no imaging in the first 12 mo after EVAR or who missed any subsequent annual imaging appointments thereafter | 569 | 268 | 301 | Yes |

| Wu et al.21 | Defined as “moderately compliant” if patients missed appointments or surveillance imaging (either one appointment or multiple ones) but continued to follow-up thereafter | 188 | 99 | 89 | Yes |

| Hicks et al.16 | Follow-up is an independent variable in the VQI registry. Patients are recorded as having only a single follow-up. If a patient had multiple follow-up visits, the latest recorded follow up status was used. (Assumption: in person follow up as compliant and telephone call follow-up as non-compliant.) | 11,309 | 2461 | 8848 | Yes |

Note. EVAR = endovascular aneurysm repair; CT = computed tomography; DUS = duplex ultrasound; VQI = vascular quality initiative.

Table 2. Overall GRADE quality assessment for each outcome.12.

| Studies (n) | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall compliance | |||||||

| 13 | Observational studies | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected/not tested | ⊕⊕⊕◯ MODERATE |

| ACM | |||||||

| 7 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Undetected/not tested | ⊕⊕⊕◯ MODERATE |

| Re-interventions | |||||||

| 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Serious | Undetected/not tested | ⊕⊕⊕◯ LOW |

| Aneurysm related mortality | |||||||

| 4 | Observational studies | Serious | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Undetected/not tested | ⊕◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

Note. GRADE = Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations; ACM = all cause mortality.

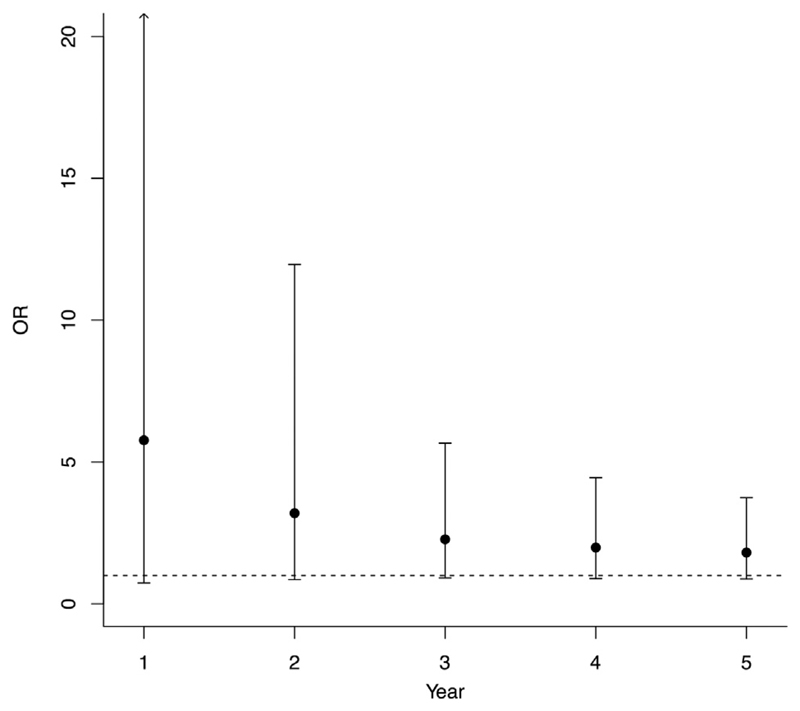

ACM

In total, 14,311 patients (6947 compliant and 7364 non-compliant) contributed to meta-analysis of ACM. There is some evidence that compliant patients have higher ACM rates in the 5 years after EVAR (year 1, OR 5.77 [95% CI 0.74–45.14]; year 3, OR 2.28 [95% CI 0.92–5.66]; year 5, OR 1.81 [95% CI 0.88–3.74]); however, this did not reach statistical significance (Table 3, Fig. 3). Overall quality of evidence is “moderate” (Table 2).12

Table 3. Comparative meta-analyses of all cause mortality.

| Time point (y) | OR | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | p-value | I2 | τ2 | Q | p value (Q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.77 | 0.74 | 45.14 | 0.10 | 92.95 | 6.48 | 36.71 | <0.01 |

| 2 | 3.20 | 0.86 | 11.96 | 0.08 | 97.16 | 2.75 | 279.09 | <0.01 |

| 3 | 2.28 | 0.92 | 5.66 | 0.08 | 95.87 | 1.27 | 218.82 | <0.01 |

| 4 | 1.99 | 0.89 | 4.45 | 0.10 | 94.43 | 0.95 | 133.21 | <0.01 |

| 5 | 1.81 | 0.88 | 3.74 | 0.11 | 90.60 | 0.71 | 89.77 | <0.01 |

Note. Odds ratio (OR) > 1 indicates that the mortality rate is higher in compliant patients.

Figure 3.

Summary of estimated average all cause mortality rates from five meta-analyses. (odds ratio [OR] > 1 indicates that the average mortality rate is higher in compliant patients). Forest plots for each of the five meta-analyses that contribute to this figure are shown in the Supplementary Material.

ACM and laxity index

Meta-regressions generally suggest that larger laxity indices are associated with larger ORs for overall survival (Tables 4 and 5, Figs. S11–S15). This observation strengthens the conclusions that ACM may be higher in more compliant patient groups, although no regression was statistically significant.

Table 4. Laxity index criteria and explanation.

| Study | Laxity index | Surveillance protocol | Definition of non-compliance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leurs et al.41 | 0 | Surveillance 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 mo, then annually | Incomplete = missing ≥1 |

| Wu et al.21 | 0.125 | Surveillance 1 and 12 months then annually (but can vary by surgeon or case) | Moderate compliance = missed ≥ 1 |

| Jones et al.40 | 0.25 | Surveillance: 1 wk, 1 mo, every 6 mo for 2 y, then annually | Incomplete= missed ≥ 2 follow-up appointments |

| Sarangarm et al.42 | 0.5 | Surveillance: 1 mo, every 6 mo for 2 y, then annually | Incomplete=missed > 2 consecutive appointments |

| Garg et al.19 | 0.63 | Surveillance: 1 mo (6 mo if abnormal 1 mo scan), 12 mo, then annually | Incomplete = gaps of 15 mo without surveillance |

| Hicks et al.16 | 1 | Last recorded visit in 1 y follow-up. SVS guidelines: 30 d, 1 y, and annually after EVAR | Did not attend any in person follow-up after EVAR |

| Waduud et al.20 | 1 | Surveillance varies | Incomplete = no imaging in the first 12 mo or missed any subsequent annual imaging surveillance |

Note. Non-compliance in terms of months without scan (every 0.5 = 12 month gap). SVS = Society for Vascular Surgery; EVAR = endovascular aneurysm repair.

Table 5. Meta-regression analysis of all cause mortality using the laxity index.

| Time point (y) | Coefficient | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.63 | −4.27 | 7.54 | 0.59 |

| 2 | 0.61 | −3.17 | 4.39 | 0.75 |

| 3 | −0.09 | −2.72 | 2.55 | 0.95 |

| 4 | 0.23 | −2.09 | 2.56 | 0.84 |

| 5 | 0.98 | −0.88 | 2.84 | 0.30 |

Note. A positive regression coefficient indicates that larger laxity values are associated with larger odds ratios. CI = confidence interval.

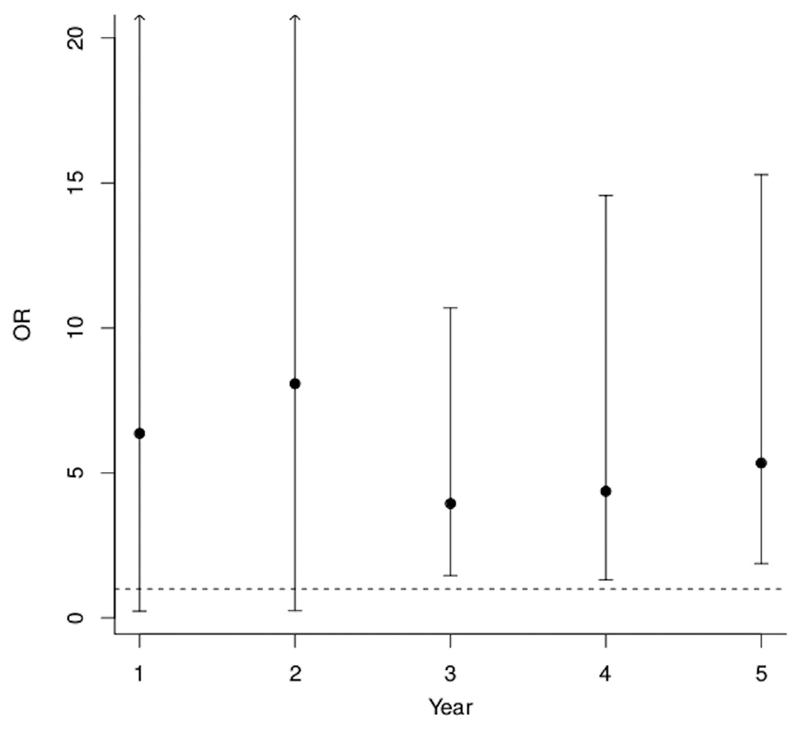

Re-intervention after EVAR

In total, 8316 (4298 compliant and 4018 non-compliant) patients contributed to meta-analysis of re-intervention after EVAR. There was no statistically significant difference in the intervention rate between the two groups for the first 2 years after EVAR (year 1, OR 6.36 [95% CI 0.23–172.73]; year 2, OR 8.08 [95% CI 0.25–262.57]). However, re-intervention rates were statistically significantly higher in compliant patients for years 3–5 after EVAR (year 3, OR 3.94 [95% CI 1.46–10.69]; year 4, OR 4.37 [95% CI 1.31–14.57]; year 5, OR 5.34 [95% CI 1.87–15.29]) (Table 6, Fig. 4). Overall quality of evidence is “low” (Table 2).12

Table 6. Comparative meta-analyses of re-intervention.

| Time point (y) | OR | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | p-value | I2 | τ2 | Q | p value (Q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.36 | 0.23 | 172.73 | 0.27 | 88.23 | 7.38 | 13.75 | <0.01 |

| 2 | 8.08 | 0.25 | 262.57 | 0.24 | 91.66 | 8.48 | 14.61 | <0.01 |

| 3 | 3.94 | 1.46 | 10.69 | 0.01 | 67.96 | 0.51 | 7.00 | 0.03 |

| 4 | 4.37 | 1.31 | 14.57 | 0.02 | 74.22 | 0.80 | 9.25 | 0.01 |

| 5 | 5.34 | 1.87 | 15.29 | <0.01 | 57.80 | 0.50 | 4.84 | 0.09 |

Note. Odds ratio (OR) > 1 indicates that the average intervention rate is higher in the compliant patients. CI = confidence interval.

Figure 4.

Summary of all estimated average re-intervention rates from five meta-analyses. (odds ratio [OR] > 1 indicates that the average re-intervention rate is higher in compliant patients). Forest plots for each of the five meta-analyses that contribute to this figure are shown in the Supplementary Material.

Secondary outcome

AAA related mortality

In total, 12,995 patients (5890 compliant and 7105 non-compliant) contributed to this analysis. Although there is some evidence that the rate of ARM is higher in compliant patients, this was not statistically significant (OR 1.47, 95% CI 0.99–2.19; p = .06) (Tables 7 and 8). Overall quality of evidence is “very low” (Table 2).12

Table 8. Random effects meta-analysis of aneurysm related mortality.

| Overall | OR | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | p-value | I2 | τ2 | Q | p-value (Q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.47 | 0.99 | 2.19 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0 | 1.82 | 0.61 |

Note. Odds ratio (OR) > 1 indicates that mortality rate is higher in the compliant patients. CI = confidence interval.

Sensitivity analysis (excluding Hicks et al.16)

ACM

In total, 13,407 patients (6182 compliant and 7225 non-compliant) contributed. The ACM rate was statistically significantly higher in compliant patients compared with non-compliant patients in the 5 years after EVAR (year 1, OR 9.85 [95% CI 1.14–84.98]; year 2, OR 5.10 [95% CI 1.57–16.56]; year 3, OR 3.26 [95% CI 1.50–7.06]; year 4, OR 2.68 [95% CI 1.35–5.33]; year 5, OR 2.09 [95% CI 1.00–4.35]; see Table S3). These results were sensitive to the decision of whether or not to include this study.

Discussion

This study highlights the wide variation in published rates of compliance with surveillance after EVAR and confirms the previously published reports of lack of adherence to surveillance programmes.8,19 Despite the recommendation by international guidelines that EVAR surveillance is mandatory, it was found in the present review that only around 60% of patients are compliant with their surveillance programmes.

The safety implications of non-compliance have previously been ill defined. Although there was no statistically significant difference, the present results suggest that compliant patients may have higher ACM rates than noncompliant patients. However, the current analyses do not imply any causal link between surveillance and survival, and, as a result, the authors recommend that this finding be interpreted with caution and not be taken at face value.

Potential reasons for this result are likely to be multi-factorial. This may be because sicker patients have more imaging for unrelated problems and therefore show a higher rate of overall mortality in the compliant group. This phenomenon was highlighted in a multicentre European study and a US population based study.19,41 However, in the study by Schanzer et al.,8 Medicare patients with comorbidities and cardiovascular risk factors were more non-compliant. The authors hypothesised that patients with competing medical pathologies become less inclined to attend EVAR surveillance. Subsequently, given the observation of different attitudes by patients with a high comorbid status, it may indicate that surveillance programmes need to be tailored according to the catchment population.

The mode of presentation to imaging surveillance could potentially explain the results of this meta-analysis. The study by Karthikesalingam et al. showed that around 60% of patients who had re-intervention presented with symptoms,4 whereas the systematic review by Nordon et al. showed that >90% of patients presented with symptoms.3 Thus, patients who were asymptomatic and potentially healthier were less likely to attend surveillance. This may explain the trend of better survival rates in non-compliant patients and why complications were noted to be higher in compliant groups.21,41 Kret et al. analysed a mixed cohort of treated aortic pathologies and observed that complications were higher in the compliant group,9 which is in line with the results of this review.

The present study showed that the re-intervention rate was statistically significantly higher in compliant patients for years 3–5 after EVAR. In contrast to this outcome, despite no difference in re-interventions or endoleak, Jones et al. noted a significantly higher rate of major complications in non-compliant patients. Major complication was defined as any complication requiring urgent surgery; however, no definition was provided for re-intervention. This contrasts with the study by Garg et al.,19 whereby the statistical difference between the two groups persisted, even when all complications, including late rupture or re-intervention, were analysed together. The results of this meta-analysis do not come as a surprise, as the aim of surveillance is to identify asymptomatic complications to allow re-intervention in order to prevent ARM.

The present study indicates that while compliant patients had higher rates of re-intervention, compliance with surveillance was not associated with a lower ARM. This raises a number of issues, one being whether the increased reintervention rate in compliant patients is reflected in the observed trend of increased overall mortality and ARM in compliant patients. As a result, more questions arise as to whether EVAR surveillance is potentially causing unnecessary treatment with the possibility of iatrogenic harm. Another issue is whether the aim of EVAR surveillanced–that of detecting and treating asymptomatic sac size increase before causing ARM–is being reached. However, the authors acknowledge that this paper did not study the causality between these outcomes.

This meta-analysis indicates that re-intervention rates for both groups during the first 2 years after EVAR, is very low. Similarly, death events at 1 year after EVAR are low. Hicks et al. also showed that non-compliance with surveillance during the first year after EVAR had a detrimental effect on survival and explains why inferences are sensitive to the inclusion or exclusion of this study.16

Apart from this observation, as there is no statistically significant difference in mortality between the two groups during the first 5 years after EVAR, and given that some published studies show that few asymptomatic complications are detected at surveillance,4,9 this study potentially highlights the benefit of risk stratification of EVAR surveillance after the first year of surveillance. Although it is not the remit of this study to discuss ways of stratification, a model developed by this institution (St George’s Vascular Institute score44) stratified patients into high and low risk for developing complications using their pre-operative aortic sac size and iliac diameter. Bastos Gonçalves et al. showed that patients with early sac shrinkage, adequate EVAR seal and no endoleak during the first year after EVAR have low risk of late complications.45,46 As a result, resources could be directed to improving and encouraging compliance in high risk patients while subjecting asymptomatic and low risk patients to lower risks of radiation exposure and nephrotoxic effects without the increased risk of re-intervention and mortality.47,48

Limitations

Different studies had different definitions for non-compliance, whereas some studies grouped non-compliant and lost to follow-up patients together.40 An attempt to reduce this limitation effect was carried out through the introduction of the laxity index for non-compliance. Although meta-regression analyses perform better if the number of studies analysed is ≥ 10,49 meta-regression analysis was carried out to further assess whether compliance is associated with ACM. The meta-regressions using the laxity index, despite their limitations, generally support the findings of the meta-analysis.

Another limitation is the way compliance data were collected by different authors. The studies by Schanzer et al. and Garg et al.,8,19 which had the largest cohort of patients, included any imaging modality which captured EVAR. Thus, one may question whether the imaging of some patients was actually surveillance imaging. This may infer that overall non-compliance with surveillance may actually be higher than 42%.

Four studies analysed ARM. This event was rare and only a small number of studies provided data, so methods for meta-analysis cannot be expected to be very accurate in this situation.

Another limitation is that definitions used for complications and re-intervention varied between studies. From the three studies that provided Kaplane–Meier curves for analysis of re-intervention, two used the term re-intervention for AAA complications,19,42 whereas the study by Jones et al. tried to differentiate between the two terms.40 Despite difficulty with this definition, the authors feel that this should not bias the result of the meta-analysis as the study by Garg et al. had a very large patient cohort compared with the study by Jones et al.27,30 This was further confirmed by the EUROSTAR registry,41 which showed significantly fewer endoleaks, graft migrations, and transfemoral secondary interventions in non-compliant patients.

A further limitation is the lack of adjustment for significant confounders across all outcomes. Elective and emergency cases of AAA repair could not be distinguished to statistically assess the impact on survival and reintervention rate. However, this may not have biased the results as the population based study by Schanzer et al. and the Medicare population study by Garg et al. showed that patients who had emergency rupture were more likely to be non-compliant.8,10 Although the authors are unaware of whether emergency AAA repairs were included in two studies,20,40 the study by Leurs et al. and Hicks et al., with large cohorts of patients, had only elective cases,16,41 whereas the compliant and non-compliant groups in the study by Wu et al. had equal proportions of emergency AAA repairs.21 Furthermore, Garg et al. and Sarangarm et al. excluded patients who had died within 30 days and those who died within the first year, respectively.19,42 Thus, the trend effect of improved survival in the non-compliant group because of fewer emergency AAAs is potentially negligible. Further to the inability to adjust for emergency procedures, it was not possible to adjust the results for other significant confounders across the outcomes. None of the studies, except the studies by Garg et al. and Hicks et al.,16,19 provided analysis after propensity matching.

Conclusion

This study suggests that although surveillance is associated with an increased rate of re-interventions, it does not appear to be associated with improved survival. Thus, improved evidence based surveillance programmes are urgently required.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2017.11.030.

What this paper adds.

Surveillance imaging is considered mandatory after endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR), but many patients are either non-compliant or lost to follow-up, and the impact of this is poorly understood. This review highlights and confirms the great variability in published EVAR surveillance compliance rates. This study also suggests that although compliance may be associated with increased re-interventions after EVAR, surveillance does not appear to confer a survival advantage to compliant patients in the first 5 years after EVAR.

Funding

Circulation Foundation Surgeon Scientist Award to A.K. P.H. is a Clinician Scientist supported financially by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR; NIHR-CS-011-008). K.S. and B.P. are NIHR funded clinical lecturers. The NIHR had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

I.L. has received research grants from Medtronic Endovascular and Endologix. K.S. is a consultant advisor for Endologix. M.M.T. is the Chief Medical Officer for Endologix.

References

- 1.Karthikesalingam A, Vidal-Diez A, Holt PJ, Loftus IM, Schermerhorn ML, Soden PA, et al. Thresholds for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in England and the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2051–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reise JA, Sheldon H, Earnshaw J, Naylor AR, Dick F, Powell JT, et al. Patient preference for surgical method of abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: postal survey. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordon IM, Karthikesalingam A, Hinchliffe RJ, Holt PJ, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. Secondary interventions following endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) and the enduring value of graft surveillance. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:547–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karthikesalingam A, Holt PJE, Hinchliffe RJ, Nordon IM, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. Risk of reintervention after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. Br J Surg. 2010;97:657–63. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaikof EL, Brewster DC, Dalman RL, Makaroun MS, Illig KA, Sicard GA, et al. SVS practice guidelines for the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm: executive summary. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:880–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wyss TR, Brown LC, Powell JT, Greenhalgh RM. Rate and predictability of graft rupture after endovascular and open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: data from the EVAR trials. Ann Surg. 2010;252:805–12. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fcb44a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker TG, Kalva SP, Yeddula K, Wicky S, Kundu S, Drescher P, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: written by the standards of practice committee for the society of interventional radiology and endorsed by the cardiovascular and interventional radiological society of europe. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:1632–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schanzer A, Messina LM, Ghosh K, Simons JP, Robinson WP, 3rd, Aiello FA, et al. Follow-up compliance after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in Medicare beneficiaries. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kret MR, Azarbal AF, Mitchell EL, Liem TK, Landry GJ, Moneta GL. Compliance with long-term surveillance recommendations following endovascular aneurysm repair or type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garg T, Baker LC, Mell MW. Adherence to postoperative surveillance guidelines after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair among medicare beneficiaries. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:23–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535–b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490–1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaikof EL, Blankensteijn JD, Harris PL, White GH, Zarins CK, Bernhard VM, et al. Reporting standards for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:1048–60. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.123763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veroniki AA, Jackson D, Viechtbauer W, Bender R, Bowden J, Knapp G, et al. Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta-analysis. Res Synth Meth. 2016;7:55–79. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dias NV, Riva L, Ivancev K, Resch T, Sonesson B, Malina M. Is there a benefit of frequent CT follow-up after EVAR? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37:425–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hicks CW, Zarkowsky DS, Bostock IC, Stone DH, Black JH, III, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, et al. Endovascular aneurysm repair patients who are lost to follow-up have worse outcomes. J Vasc Surg. 2017;65:1625–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.10.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Mestral C, Croxford R, Eisenberg N, Roche-Nagle G. The impact of compliance with imaging follow-up on mortality after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: a population based cohort study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;54:315–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2017.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson D, Turner R. Power analysis for random-effects meta-analysis. Res Synth Meth. 2017;8:290–302. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garg T, Baker LC, Mell MW. Postoperative surveillance and long-term outcomes after endovascular aneurysm repair among medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:957–63. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waduud MA, Choong WL, Ritchie M, Williams C, Yadavali R, Lim S, et al. Endovascular aneurysm repair: is imaging surveillance robust, and does it influence long-term mortality? Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38:33–9. doi: 10.1007/s00270-014-0890-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu CY, Chen H, Gallagher KA, Eliason JL, Rectenwald JE, Coleman DM, et al. Predictors of compliance with surveillance after endovascular aneurysm repair and comparative survival outcomes. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohki T, Veith FJ, Shaw P, Lipsitz E, Suggs WD, Wain RA, et al. Increasing incidence of midterm and long-term complications after endovascular graft repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a note of caution based on a 9-year experience. Ann Surg. 2001;234:323–35. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200109000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alric P, Hinchliffe RJ, Wenham PW, Whitaker SC, Chuter TAM, Hopkinson BR. Lessons learned from the long-term follow-up of a first-generation aortic stent graft. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:367–73. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang RW, Goodney P, Tucker L-Y, Okuhn S, Hua H, Rhoades A, et al. Ten-year results of endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair from a large multicenter registry. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:324–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsagkas M, Kouvelos G, Peroulis M, Avgos S, Arnaoutoglou E, Papa N, et al. Standard endovascular treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients with very short proximal necks using the endurant stent graft. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison GJ, Oshin OA, Vallabhaneni SR, Brennan JA, Fisher RK, McWilliams RG, et al. Surveillance after EVAR based on duplex ultrasound and abdominal radiography. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42:187–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noll RE, Jr, Tonnessen BH, Kim J, Money SR, Sternbergh WC., 3rd Long-term postplacement cost comparison of aneurx and zenith endografts. Ann Vasc Surg. 2008;22:710–5. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehta M, Paty PSK, Roddy SP, Taggert JB, Sternbach Y, Kreienberg PB, et al. Treatment options for delayed aaa rupture following endovascular repair. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antoniou GA, Georgiadis GS, Glancz L, Delbridge M, Murray D, Smyth JV, et al. Outcomes of endovascular aneurysm repair with 2 different endograft systems with suprarenal fixation in patients with hostile infrarenal aortic anatomy. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;47:9–18. doi: 10.1177/1538574412467859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antoniou GA, Georgiadis GS, Antoniou SA, Neequaye S, Brennan JA, Torella F, et al. Late rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysm after previous endovascular repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endovasc Ther. 2015;22:734–44. doi: 10.1177/1526602815601405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beckerman WE, Tadros RO, Faries PL, Torres M, Wengerter SP, Vouyouka AG, et al. No major difference in outcomes for endovascular aneurysm repair stent grafts placed outside of instructions for use. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64:63–74.e62. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang D, Park S, Kim HK, Lee JM, Huh S. Reintervention rate after open surgery and endovascular repair for nonruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg. 2017;43:134–43. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2017.03.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahajan A, Barber M, Cumbie T, Filardo G, Shutze WP, Jr, Sass DM, et al. The impact of aneurysm morphology and anatomic characteristics on long-term survival after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;34:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Png CYM, Tadros RO, Faries PL, Torres MR, Kim SY, Lookstein R, et al. The effect of age on post-evar outcomes. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;35:156–62. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zacharias N, Warner CJ, Taggert JB, Roddy SP, Kreienberg PB, Ozsvath KJ, et al. Anatomic characteristics of abdominal aortic aneurysms presenting with delayed rupture after endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64:1629–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roy IN, Vallabhaneni SR. Profile of secondary interventions and triggering surveillance imaging after evar. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2016;39:S153. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spanos K, Karathanos C, Athanasoulas A, Sapeltsis V, Giannoukas AD. Systematic review of follow up compliance after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2016 Nov 23; doi: 10.23736/S0021-9509.16.09628-2. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Godfrey AD, Morbi AHM, Nordon IM. Patient compliance with surveillance following elective endovascular aneurysm repair. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38:1130–6. doi: 10.1007/s00270-015-1073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.AbuRahma AF, Yacoub M, Hass SM, AbuRahma J, Mousa AY, Dean LS, et al. Compliance of postendovascular aortic aneurysm repair imaging surveillance. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63:589–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones WB, Taylor SM, Kalbaugh CA, Joels CS, Blackhurst DW, Langan EM, Iii, et al. Lost to follow-up: a potential underappreciated limitation of endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:434–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leurs LJ, Laheij RJ, Buth J. What determines and are the consequences of surveillance intensity after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair? Ann Vasc Surg. 2005;19:868–75. doi: 10.1007/s10016-005-7751-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarangarm D, Knepper J, Marek J, Biggs KL, Robertson D, Langsfeld M. Post-endovascular aneurysm repair patient out-comes and follow-up are not adversely impacted by long travel distance to tertiary vascular surgery centers. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:1075–81. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen J, Pai A, Sullivan TM, Alden P, Alexander JQ, Cragg A, et al. A dedicated surveillance program improves compliance with endovascular aortic aneurysm repair follow-up. Ann Vasc Surg. 2017;44:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2017.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karthikesalingam A, Holt PJ, Vidal-Diez A, Choke EC, Patterson BO, Thompson LJ, et al. Predicting aortic complications after endovascular aneurysm repair. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1302–11. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bastos Gonçalves F, Baderkhan H, Verhagen HJM, Wanhainen A, Björck M, Stolker RJ, et al. Early sac shrinkage predicts a low risk of late complications after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. Br J Surg. 2014;101:802–10. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bastos Goncalves F, van de Luijtgaarden KM, Hoeks SE, Hendriks JM, ten Raa S, Rouwet EV, et al. Adequate seal and no endoleak on the first postoperative computed tomography angiography as criteria for no additional imaging up to 5 years after endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:1503–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.11.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomographydan increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2277–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Solomon R, DuMouchel W. Contrast media and nephropathy. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:651–60. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000229742.54589.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson D, Riley RD. A refined method for multivariate meta-analysis and meta-regression. Stat Med. 2014;33:541–54. doi: 10.1002/sim.5957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.