Abstract

Background

The projected rise in the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) could develop into a substantial health problem worldwide. Whether dipeptidyl‐peptidase (DPP)‐4 inhibitors or glucagon‐like peptide (GLP)‐1 analogues are able to prevent or delay T2DM and its associated complications in people at risk for the development of T2DM is unknown.

Objectives

To assess the effects of DPP‐4 inhibitors and GLP‐1 analogues on the prevention or delay of T2DM and its associated complications in people with impaired glucose tolerance, impaired fasting blood glucose, moderately elevated glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) or any combination of these.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; MEDLINE; PubMed; Embase; ClinicalTrials.gov; the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform; and the reference lists of systematic reviews, articles and health technology assessment reports. We asked investigators of the included trials for information about additional trials. The date of the last search of all databases was January 2017.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with a duration of 12 weeks or more comparing DPP‐4 inhibitors and GLP‐1 analogues with any pharmacological glucose‐lowering intervention, behaviour‐changing intervention, placebo or no intervention in people with impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, moderately elevated HbA1c or combinations of these.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors read all abstracts and full‐text articles and records, assessed quality and extracted outcome data independently. One review author extracted data which were checked by a second review author. We resolved discrepancies by consensus or the involvement of a third review author. For meta‐analyses, we planned to use a random‐effects model with investigation of risk ratios (RRs) for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences (MDs) for continuous outcomes, using 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for effect estimates. We assessed the overall quality of the evidence using the GRADE instrument.

Main results

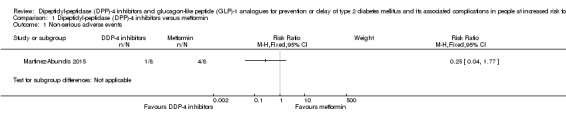

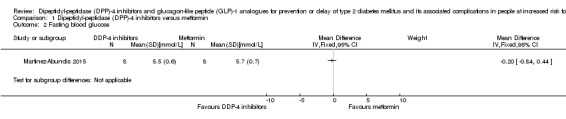

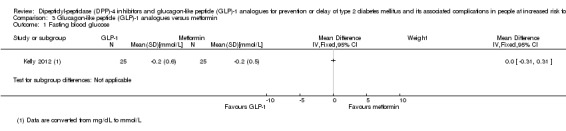

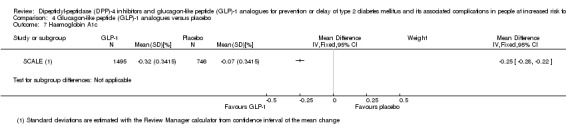

We included seven completed RCTs; about 98 participants were randomised to a DPP‐4 inhibitor as monotherapy and 1620 participants were randomised to a GLP‐1 analogue as monotherapy. Two trials investigated a DPP‐4 inhibitor and five trials investigated a GLP‐1 analogue. A total of 924 participants with data on allocation to control groups were randomised to a comparator group; 889 participants were randomised to placebo and 33 participants to metformin monotherapy. One RCT of liraglutide contributed 85% of all participants. The duration of the intervention varied from 12 weeks to 160 weeks. We judged none of the included trials at low risk of bias for all 'Risk of bias' domains and did not perform meta‐analyses because there were not enough trials.

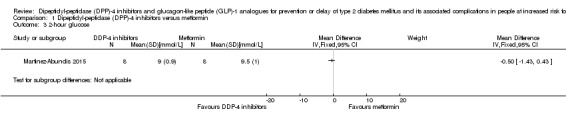

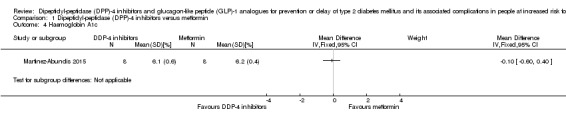

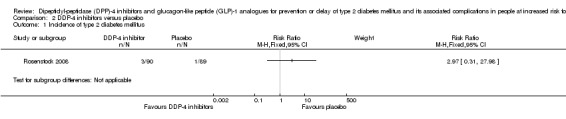

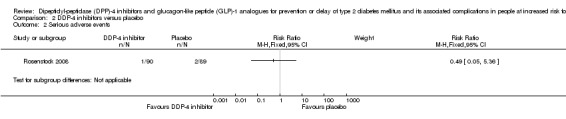

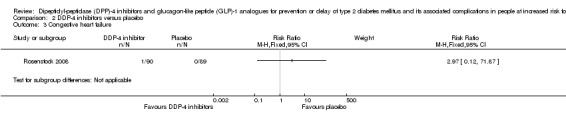

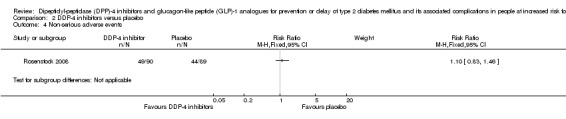

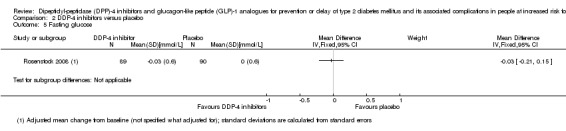

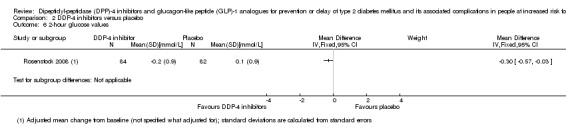

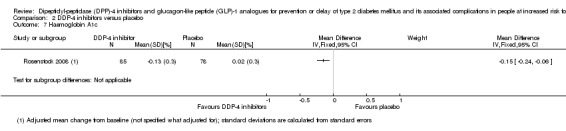

One trial comparing the DPP‐4 inhibitor vildagliptin with placebo reported no deaths (very low‐quality evidence). The incidence of T2DM by means of WHO diagnostic criteria in this trial was 3/90 participants randomised to vildagliptin versus 1/89 participants randomised to placebo (very low‐quality evidence). Also, 1/90 participants on vildagliptin versus 2/89 participants on placebo experienced a serious adverse event (very low‐quality evidence). One out of 90 participants experienced congestive heart failure in the vildagliptin group versus none in the placebo group (very low‐quality evidence). There were no data on non‐fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, health‐related quality of life or socioeconomic effects reported.

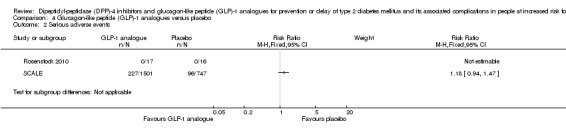

All‐cause and cardiovascular mortality following treatment with GLP‐1 analogues were rarely reported; one trial of exenatide reported that no participant died. Another trial of liraglutide 3.0 mg showed that 2/1501 in the liraglutide group versus 2/747 in the placebo group died after 160 weeks of treatment (very low‐quality evidence).

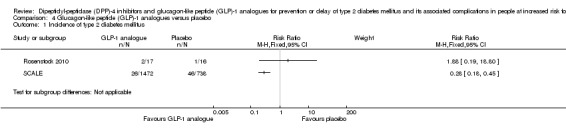

The incidence of T2DM following treatment with liraglutide 3.0 mg compared to placebo after 160 weeks was 26/1472 (1.8%) participants randomised to liraglutide versus 46/738 (6.2%) participants randomised to placebo (very low‐quality evidence). The trial established the risk for (diagnosis of) T2DM as HbA1c 5.7% to 6.4% (6.5% or greater), fasting plasma glucose 5.6 mmol/L or greater to 6.9 mmol/L or less (7.0 mmol/L or greater) or two‐hour post‐load plasma glucose 7.8 mmol/L or greater to 11.0 mmol/L (11.1 mmol/L). Altogether, 70/1472 (66%) participants regressed from intermediate hyperglycaemia to normoglycaemia compared with 268/738 (36%) participants in the placebo group. The incidence of T2DM after the 12‐week off‐treatment extension period (i.e. after 172 weeks) showed that five additional participants were diagnosed T2DM in the liraglutide group, compared with one participant in the placebo group. After 12‐week treatment cessation, 740/1472 (50%) participants in the liraglutide group compared with 263/738 (36%) participants in the placebo group had normoglycaemia.

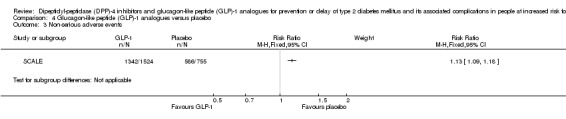

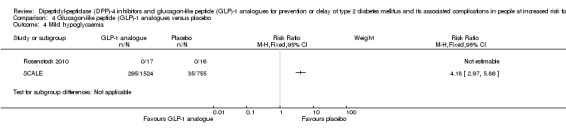

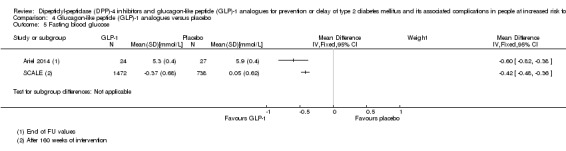

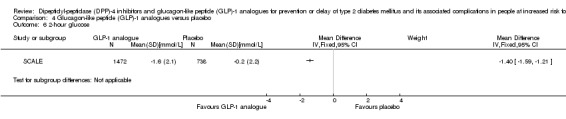

One trial used exenatide and 2/17 participants randomised to exenatide versus 1/16 participants randomised to placebo developed T2DM (very low‐quality evidence). This trial did not provide a definition of T2DM. One trial reported serious adverse events in 230/1524 (15.1%) participants in the liraglutide 3.0 mg arm versus 96/755 (12.7%) participants in the placebo arm (very low quality evidence). There were no serious adverse events in the trial using exenatide. Non‐fatal myocardial infarction was reported in 1/1524 participants in the liraglutide arm and in 0/55 participants in the placebo arm at 172 weeks (very low‐quality evidence). One trial reported congestive heart failure in 1/1524 participants in the liraglutide arm and in 1/755 participants in the placebo arm (very low‐quality evidence). Participants receiving liraglutide compared with placebo had a small mean improvement in the physical component of the 36‐item Short Form scale showing a difference of 0.87 points (95% CI 0.17 to 1.58; P = 0.02; 1 trial; 1791 participants; very low‐quality evidence). No trial evaluating GLP‐1‐analogues reported data on stroke, microvascular complications or socioeconomic effects.

Authors' conclusions

There is no firm evidence that DPP‐4 inhibitors or GLP‐1 analogues compared mainly with placebo substantially influence the risk of T2DM and especially its associated complications in people at increased risk for the development of T2DM. Most trials did not investigate patient‐important outcomes.

Plain language summary

Dipeptidyl‐peptidase (DPP)‐4 inhibitors and glucagon‐like peptide (GLP)‐1 analogues for prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus

Review question

Are the glucose‐lowering medicines, DPP‐4 inhibitors (e.g. linagliptin or vildagliptin) and GLP‐1 analogues (e.g. exenatide or liraglutide) able to prevent or delay the development of type 2 diabetes and its associated complications in people at risk for the development of type 2 diabetes?

Background

DPP‐4 inhibitors and GLP‐1 analogues are widely used to treat people with type 2 diabetes. People with moderately elevated blood glucose are said to be at an increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes (often referred to as 'prediabetes'). It is currently not known whether DPP‐4 inhibitors or GLP‐1 analogues should be prescribed for people with raised blood glucose levels who do not have type 2 diabetes. We wanted to find out whether these medicines could prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people at increased risk. We also wanted to know the effects on patient‐important outcomes such as complications of diabetes (e.g. kidney and eye disease, heart attacks, strokes), death from any cause, health‐related quality of life (a measure of a person's satisfaction with their life and health) and side effects of the medicines.

Study characteristics

Participants had to have blood glucose levels higher than considered normal, but below the glucose levels that are used to diagnose type 2 diabetes mellitus. We found seven randomised controlled trials (clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) with 2702 participants. The duration of the treatments varied from 12 weeks to 160 weeks. One study investigating liraglutide dominated the evidence (2285/2702 participants). The participants in this study were overweight or obese.

This evidence is up to date as of January 2017.

Key results

DPP‐4 inhibitors did not reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared with placebo (a dummy medicine). In the big study investigating the GLP‐1‐analogue liraglutide, given in a dose used for obese people (3.0 mg), the development of type 2 diabetes was delayed: 26/1472 (1.8%) participants randomised to liraglutide compared with 46/738 (6.2%) participants randomised to placebo developed type 2 diabetes after 160 weeks. On the other side, 970/1472 (66%) participants randomised to liraglutide compared with 268/738 (36%) participants randomised to placebo switched back to normal glucose levels. This study was extended for another 12 weeks without treatment and five additional participants developed diabetes in the liraglutide group, compared with one participant in the placebo group. After the 12 weeks without treatment, 740/1472 (50%) participants in the liraglutide group compared with 263/738 (36%) participants in the placebo group had glucose levels considered as normal. This means that to keep chances high to prevent type 2 diabetes in people at risk one probably needs to continuously take this drug. Of note, serious adverse events (e.g. defined as hospitalisation or a hazard putting the participant at risk, such as an interaction with another medicine) happened more often following liraglutide treatment (230/1524 (15%) participants in the liraglutide group and 96/755 (13%) participants in the placebo group) and it is unclear whether taking this drug is safe in the long term.

We detected neither an advantage nor a disadvantage of DPP‐4 inhibitors or GLP‐1 analogues in relation to non‐fatal heart attacks, non‐fatal strokes or heart failure. Our included studies did not report on other complications of diabetes such as kidney or eye disease. The effects on health‐related quality of life were inconclusive. In the included studies, very few participants died and there was no apparent relation to treatment.

Future studies should investigate more patient‐important outcomes like complications of diabetes and especially the side effects of the medications, because we do not know for sure whether 'prediabetes' is just a condition arbitrarily defined by a laboratory measurement, is in fact a real risk factor for type 2 diabetes mellitus and whether treatment of this condition translates into better patient‐important outcomes.

Quality of the evidence

All included trials had deficiencies in the way they were conducted or how key items were reported. For the individual comparisons, the number of participants was small, resulting in a high risk of random errors (play of chance).

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

'Prediabetes', 'borderline diabetes', the 'prediabetic stage', 'high risk of diabetes', 'dysglycaemia' or 'intermediate hyperglycaemia' are often characterised by various measurements of elevated blood glucose concentrations, such as isolated impaired fasting glucose (IFG), isolated impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), isolated elevated glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) or combinations thereof (WHO/IDF 2006). These elevated blood glucose levels that indicate hyperglycaemia are too high to be considered normal, but are below the diagnostic threshold for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Therefore, due to the continuous glycaemic spectrum from the normal to the diabetic stage, a sound evidence base is needed to define glycaemic thresholds for people at high risk of T2DM. The different terms used to describe various stages of hyperglycaemia may cause people to have different emotional reactions. For example, the term 'prediabetes' may imply (at least for lay people) that the disease diabetes is unavoidable, whereas (high) risk of diabetes has the positive connotation of possibly being able to avoid the disease altogether. In addition to the disputable construct of intermediate health states termed 'prediseases' (Viera 2011), many people may associate the label 'prediabetes' with dire consequences. Alternatively, any diagnosis of 'prediabetes' may be an opportunity to review, for example, eating habits and physical activity levels, thus enabling affected people to actively change their way of life.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) established the most commonly used criteria to define people who are at a high risk of developing T2DM. IGT was the first glycaemic measurement used by the US National Diabetes Data Group to define the prediabetes stage (NDDG 1979). It is based on the measurement of plasma glucose two hours after ingestion of glucose 75 g. The dysglycaemic range is defined as plasma glucose concentrations between 7.8 mmol/L and 11.1 mmol/L (140 mg/dL and 200 mg/dL) two hours after the glucose load. Studies indicate that IGT is caused by insulin resistance and defective insulin secretion (Abdul‐Ghani 2006; Jensen 2002). In 1997, the ADA and later the WHO introduced the IFG concept to define 'prediabetes' and intermediate hyperglycaemia (ADA 1997; WHO 1999). The initial definition of IFG was fasting blood glucose concentrations between 6.1 mmol/L and 6.9 mmol/L (110 mg/dL and 125 mg/dL). Later, the ADA reduced the lower threshold for defining IFG to 5.6 mmol/L (100 mg/dL) (ADA 2003). However, the WHO did not endorse this lower cut‐off point for IFG to define 'prediabetes' (WHO/IDF 2006). IFG seems to be associated with β‐cell dysfunction (impaired insulin secretion) and an increase in the hepatic glucose output (DeFronzo 1989). More recently, HbA1c has been introduced to identify people at high risk of developing T2DM. In 2009, the International Expert Committee (IEC) suggested certain HbA1c ranges to identify people at a high risk of T2DM. People with HbA1c measurements between 6.0% and 6.4% fulfilled this criterion (IEC 2009). Shortly afterwards, the ADA redefined this HbA1c level as 5.7% to 6.4% to identify people at a high risk of developing T2DM (ADA 2010), a decision not endorsed by WHO, IEC or other organisations. Unlike IFG and IGT, HbA1c reflects longer‐term glycaemic control, that is how a person's blood glucose concentrations have been during the preceding two to three months (Inzucchi 2012).

In 2010, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimated the prevalence of IGT to be 343 million people, and this is predicted to increase to 642 million people by 2040 (IDF 2015). Studies have shown poor correlations between HbA1c and IFG/IGT (Gosmanov 2014; Selvin 2011). Notably, the various glycaemic tests do not seem to identify the same people, as there is an imperfect overlap among the glycaemic modalities available to define intermediate hyperglycaemia (Gosmanov 2014; Selvin 2011). The risk of progression from people at risk to T2DM depends on the diagnostic criteria used to identify the risk. Some people with intermediate risk will never develop T2DM, and some people will return to normoglycaemia. IGT is often accepted as the best glycaemic variable for risk to predict progression to T2DM. However, studies indicate that less than half of the people defined as 'prediabetic' by means of IGT will develop T2DM in the following 10 years (Morris 2013). IFG and HbA1c are thought to predict a different risk spectrum for developing T2DM (Cheng 2006; Morris 2013). Most importantly, dysglycaemia is commonly an asymptomatic condition, and naturally often remains 'undiagnosed' (CDC 2015).

It has not been clarified whether any particular intervention, especially glucose‐lowering drugs, should be recommended for people at risk for T2DM (Yudkin 2014). Trials have indicated that the progression to T2DM is reduced, or possibly only delayed, with behavioural interventions (increased physical activity, dietary changes, or both) (Diabetes Prevention Program 2009; Knowler 2002; Tuomilehto 2001). One meta‐analysis of 22 trials with interventions that changed behaviour in people at high risk of T2DM concluded that the effect of these interventions on longer‐term diabetes prevention is unclear (Dunkley 2014). Therefore, more research is needed to establish optimal strategies for reducing T2DM with behavioural approaches (Dunkley 2014).

International diabetes associations and clinicians do not generally accept the prescription of pharmacological glucose‐lowering interventions for the prevention of T2DM. Several groups of pharmacological glucose‐lowering interventions have been investigated for people at risk of T2DM. Some findings indicate that the progression to T2DM is reduced or may only be delayed (Knowler 2002; Diabetes Prevention Program 2009). However, the ADA recommends metformin for people at risk of T2DM, especially for those with a body mass index (BMI) over 35 kg/m², aged less than 60 years, women with prior gestational diabetes mellitus, people with rising HbA1c despite lifestyle intervention, or a combination of these (ADA 2017).

Description of the intervention

Sitagliptin was the first dipeptidyl‐peptidase (DPP)‐4 inhibitor approved as a glucose‐lowering intervention for people with T2DM (FDA 2006). Since then, several other types of DPP‐4 inhibitors have been approved for T2DM, such as alogliptin, anagliptin, linagliptin, saxagliptin, teneligliptin and vildagliptin. The DPP‐4 inhibitors are administered orally.

Exenatide was the first glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) analogue approved as a glucose‐lowering intervention for people with T2DM (FDA 2005). Since then, several other types of GLP‐1 analogues have been approved. The GLP‐1 analogues can be categorised as either short‐acting (e.g. exenatide) or long‐acting (e.g. liraglutide). Currently available GLP‐1 analogues are administered subcutaneously. Peroral GLP‐1 analogues are in the pipeline (NCT02161588).

For people with T2DM, GLP‐1 analogues and DPP‐4 inhibitors can be prescribed as monotherapy or in combination with existing glucose‐lowering interventions (ADA 2014). Currently, the GLP‐1 analogues or DPP‐4 inhibitors are not recommended for people with intermediate hyperglycaemia (ADA 2014). However, it has been shown that people with IGT have alterations in circulating incretin hormones (Rask 2004).

Adverse effects of the intervention

The most common adverse effects of GLP‐1 analogues are gastrointestinal disturbances and nausea. Nausea and vomiting associated with the GLP‐1 analogues are dose‐dependent and appear to decrease over time (Reid 2014). For DPP‐4 inhibitors, the most common adverse effects reported are gastrointestinal disturbances (Reid 2014).

Both the GLP‐1 analogues and the DPP‐4 inhibitors have been suggested to increase risk of pancreatitis and potentially pancreatic cancer (Nagel 2015). The incidence of acute pancreatitis has been low in large‐scale randomised controlled trials (RCTs), and was slightly increased compared with placebo (Scirica 2013; Zannad 2015). The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have made comprehensive evaluations of the safety of the incretin‐based interventions based on post‐marketing reports of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer in people with T2DM. These post‐marketing data have not been convincing regarding these adverse effects (Egan 2014). Nevertheless, current opinion holds that DPP‐4 inhibitors should not be prescribed to people at risk of or having existing pancreatitis (De Heer 2014). Besides, the DPP‐4 inhibitors have been reported to increase the risk of heart failure; however, this is still not clarified (Elgendy 2017; Rehman 2017). However, one large‐scale trial investigating the DPP‐4 inhibitor, saxagliptin, was associated with an increased risk of heart failure leading to hospitalisation (hazard ratio (HR) 1.27, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07 to 1.51) (Scirica 2013).

Results of systematic reviews are conflicting and adverse effects could vary with the type of DPP‐4 inhibitor used (Elgendy 2017).

An increased risk of thyroid cell neoplasm has been observed in rodents exposed to GLP‐1 analogues. However, this increased risk has not been observed in people (Reid 2014).

How the intervention might work

A two‐ to three‐fold greater increase in plasma insulin is observed when glucose is administered orally compared with an intravenous application (Nauck 1986). This phenomenon is called the incretin effect and accounts for approximately 70% to 80% of total insulin release after orally administered glucose (Nauck 1986). The incretin effect is mediated mainly by GLP‐1 and glucose‐dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) (Nauck 1986). GLP‐1 is a 30‐amino acid polypeptide produced in the intestinal L cell upon processing of the precursor proglucagon (Bell 2013). GLP‐1 and GIP exert powerful and strictly glucose‐dependent insulinotropic activity via specific GLP‐1 and GIP receptors in the plasma membrane of pancreatic β‐cells (Holst 2007). In addition, GLP‐1 reduces glucagon secretion, an effect that might be as clinically important as the insulinotropic effect of GLP‐1 (Holst 2007; Orskov 1988). Furthermore, GLP‐1 reduces food intake (most likely via activation of GLP‐1 receptors in the central nervous system) and delays gastric emptying, whereby postprandial glucose excursions and food intake are reduced (Holst 2007). Lastly, in animal models GLP‐1 promotes β‐cell growth and inhibits β‐cell apoptosis (Holst 2007; Holz 1993). During the progression from normal glucose tolerance to insulin resistance and eventually to T2DM, some studies have shown that plasma GLP‐1 concentrations decline (Rask 2004; Toft‐Nielsen 2001). However, one meta‐analysis suggested that people with T2DM do not exhibit reduced GLP‐1 secretion in response to an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) or meal test (Calanna 2013).

Native GLP‐1 and GIP are rapidly inactivated (half‐life: GLP‐1: 2 minutes; GIP: 5 to 7 minutes) by the enzyme DPP‐4, expressed in many tissues (e.g. kidney and intestine) (Creutzfeldt 1979). DPP‐4 inhibitors exert competitive inhibition of DPP‐4 and thereby increase the concentrations of active (endogenous) GLP‐1 and GIP (Holst 2007). GLP‐1 analogues are resistant to DPP‐4 degradation (Holst 2007).

Why it is important to do this review

There has been an increased focus on the prevention or delay of T2DM with non‐pharmacological interventions and glucose‐lowering medications. Currently, several trials are being conducted to clarify whether the progression from an at‐risk status to T2DM can be stopped or postponed with glucose‐lowering agents (ClinicalTrials.gov). However, a more important issue for people with dysglycaemia is whether these interventions reduce the risk of death or complications ‐ especially cardiovascular disease ‐ related to T2DM.

Objectives

To assess the effects of DPP‐4 inhibitors and GLP‐1 analogues on the prevention or delay of T2DM and its associated complications in people with impaired glucose tolerance, impaired fasting blood glucose, moderately elevated glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) or any combination of these.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs.

Types of participants

We included non‐diabetic people with increased risk of T2DM.

Diagnostic criteria for people at risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus development

To be consistent with changes to the classification of, and diagnostic criteria for, intermediate hyperglycaemia (IFG, IGT and elevated HbA1c) over the years, the diagnosis should be established using the standard criteria valid at the trial start (e.g. ADA 1997; ADA 2010; NDDG 1979; WHO 1999). Ideally, the diagnostic criteria should have been described. If necessary, we used the trial authors' definition of risk but we contacted trial authors for additional information. Differences in the glycaemic measurements used to define risk may introduce substantial heterogeneity. Therefore, we planned to subject the diagnostic criteria to a subgroup analysis.

Types of interventions

We planned to investigate the following comparisons of DPP‐4 inhibitors or GLP‐1 analogues versus all other pharmacological glucose‐lowering interventions, behaviour‐changing interventions, placebo or no intervention.

Intervention

DPP‐4 inhibitors as monotherapy.

DPP‐4 inhibitors as a part of a combination therapy.

GLP‐1 analogues as monotherapy.

GLP‐1 analogues as a part of a combination therapy.

Comparator

Any pharmacological glucose‐lowering intervention (e.g. acarbose, metformin, sulphonylurea) compared with DPP‐4 inhibitors as monotherapy or GLP‐1 analogues as monotherapy.

Any pharmacological glucose‐lowering agent (e.g. acarbose, metformin, sulphonylurea) compared with DPP‐4 inhibitors as a part of a combination therapy or GLP‐1 analogues as a part of a combination therapy if this glucose‐lowering agent was the same in both the intervention and comparator groups (e.g. DPP‐4 inhibitor plus metformin versus metformin).

Behaviour‐changing interventions (e.g. diet, exercise, diet and exercise) compared with DPP‐4 inhibitors as monotherapy or GLP‐1 analogues as monotherapy.

Placebo compared with DPP‐4 inhibitors as monotherapy or GLP‐1 analogues as monotherapy.

No intervention compared with DPP‐4 inhibitors as monotherapy or GLP‐1 analogues as monotherapy.

Other concomitant interventions (e.g. educational programmes or additional pharmacotherapy) had to be the same in both the intervention and comparator groups to establish fair comparisons.

Minimum duration of intervention

We included trials with a duration of the intervention of 12 weeks or more.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded trials of people diagnosed with the 'metabolic syndrome' because this is a special population which is not representative of people with only intermediate hyperglycaemia. Also, the composite of risk indicators such as elevated blood lipids, insulin resistance, obesity and hypertension which is termed 'metabolic syndrome' is of doubtful clinical usefulness and uncertain distinct disease entity. However, should we identify trials investigating participants with any definition of the metabolic syndrome, we summarised some basic trial information in an additional table.

We excluded trials evaluating participants with intermediate hyperglycaemia in combination with another condition (e.g. cystic fibrosis).

We excluded trials evaluating participants with intermediate hyperglycaemia because of other medical interventions (e.g. glucocorticoids).

We tried to include trials explicitly describing that a portion of the included participants had intermediate hyperglycaemia. We contacted the investigators to obtain separate data on the group with intermediate hyperglycaemia and include these in the meta‐analyses.

We included trials in obese people and participants with previous gestational diabetes, if trial investigators described that the participants had intermediate hyperglycaemia.

We included a trial even if it did not report one or more of our primary or secondary outcome measures in the publication. If a trial did not report any of our primary or secondary outcomes, we included this trial and contacted the corresponding trial author for supplementary data. We listed information about trials with a duration of the intervention shorter than 12 weeks in Appendix 1.

Some trials evaluated GLP‐1 analogues in doses recommended for achieving a weight‐reducing effect rather than a glucose‐lowering effect. We included such trials and performed subgroup analyses according to the dose of GLP‐1 analogues.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality.

Incidence of T2DM.

Serious adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

Cardiovascular mortality.

Non‐fatal myocardial infarction.

Non‐fatal stroke.

Congestive heart failure.

Amputation of lower extremity.

Blindness or severe vision loss.

End‐stage renal disease.

Non‐serious adverse events.

Hypoglycaemia.

Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL).

Time to progression to T2DM.

Measures of blood glucose control.

Socioeconomic effects.

Method and timing of outcome measurement

All‐cause mortality: defined as death from any cause. Measured at any time of the intervention and during follow‐up.

Incidence of T2DM and time to progression to T2DM: defined according to diagnostic criteria valid at the time the diagnosis was established using the standard criteria valid at the time of the trial commencing (e.g. ADA 2008; WHO 1998). If necessary, we used the trial authors' definition of T2DM. Measured at the end of the intervention and the end of follow‐up. We also investigated regression from intermediate hyperglycaemia back to normoglycaemia.

Serious adverse events: defined according to the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines as any event that led to death, was life‐threatening, required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability, or any important medical event which may have had jeopardised the person or required intervention to prevent it (ICH 1997), or as reported in trials. Measured at any time of the intervention and during follow‐up.

Cardiovascular mortality, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, non‐fatal stroke, congestive heart failure, amputation of lower extremity, blindness or severe vision loss, hypoglycaemia (mild, moderate, severe/serious): defined as reported in trials. Measured at the end of the intervention and at the end of follow‐up.

End‐stage renal disease: defined as dialysis, renal transplantation or death due to renal disease. Measured at the end of the intervention and at the end of follow‐up.

Non‐serious adverse events: defined as the number of participants with any untoward medical occurrence not necessarily having a causal relationship with the intervention. Measured at any time of the intervention and during follow‐up.

HRQoL: defined as mental and physical HRQoL as separate domains and combined, evaluated by a validated instrument such as the 36‐item Short‐Form (SF‐36). Measured at the end of the intervention and at the end of follow‐up.

Measures of blood glucose control: fasting blood glucose, blood glucose two hours after ingestion of glucose 75 g and HbA1c measurements. Measured at the end of the intervention and at the end of follow‐up.

Socioeconomic effects: for example, costs of the intervention, absence from work and medication consumption. Measured at the end of the intervention and at the end of follow‐up.

Specification of key prognostic variables

Age.

Gender.

Equity issues (access to health care, social determinants).

Ethnicity.

Hypertension.

Cardiovascular disease.

Obesity.

Previous gestational diabetes.

'Summary of findings' table

We present a 'Summary of findings' table to report the following outcomes, listed according to priority.

All‐cause mortality.

Incidence of T2DM.

Serious adverse events.

Cardiovascular mortality.

Non‐fatal myocardial infarction/stroke and congestive heart failure.

HRQoL.

Socioeconomic effects.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following sources from inception of each database to the specified date, and placed no restrictions on the language of publication.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (26 January 2017).

Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to 26 January 2017).

PubMed (subsets not available on Ovid) (12 February 2016).

Embase (1974 to 2017 week 4, 26 January 2017).

ClinicalTrials.gov (26 January 2017).

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) (26 January 2017).

We continuously used a MEDLINE (via OvidSP) email alert service established by the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders (CMED) Group to identify newly published trials using the same search strategy as described for MEDLINE (for details on search strategies, see Appendix 2).

We obtained evaluations of all relevant non‐English articles.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of retrieved included trials, systematic reviews, meta‐analyses and health technology assessment reports for other potentially eligible trials or ancillary publications. In addition, we contacted authors of included trials to identify any additional information on the retrieved trials and if further trials existed, that we may have missed.

As none of the existing DPP‐4 inhibitors or GLP‐1 analogues is approved in glucose‐lowering doses for intermediate hyperglycaemia, we did not search databases of the regulatory agencies (EMA, US FDA). However, GLP‐1 analogues in higher doses are approved as a weight‐reducing intervention in obese people with intermediate hyperglycaemia. Therefore, we searched EMA and FDA for GLP‐1 analogues approved as a weight‐reducing intervention.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (BH and DS) independently scanned the abstract, title, or both, of every record we retrieved in the literature searches, to determine which trials should be assessed further. We investigated the full text of all potentially relevant articles. We resolved discrepancies through consensus or by recourse to a third review author (BR). We prepared a flow diagram of the number of trials identified and excluded at each stage in accordance with the PRISMA flow diagram of trial selection (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

For trials that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, two review authors (BH and DS) independently extracted outcome data and assessed the risk of bias. Key characteristics of participants and interventions were extracted by one review author (BH) and controlled by another (DS). We reported data on efficacy outcomes and adverse events using standard data extraction sheets from the CMED Group. We resolved any disagreements by discussion or, if required, by consultation with a third review author (BR) (for details, see Characteristics of included studies table; Table 3; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8; Appendix 9; Appendix 10; Appendix 11; Appendix 12; Appendix 13; Appendix 14; Appendix 15; Appendix 17; Appendix 18).

1. Overview of trial populations.

| Trial (design) | Intervention and comparator | Description of power and sample size calculation and handling of missing data | Screened/eligible (n) | Randomised (n) | ITT (n) | Analysed (n) | Finishing trial (n) | Randomised finishing trial (%) | Follow‐up (extended follow‐up)a |

|

Ariel 2014 (parallel RCT) |

I: liraglutide 1.8 mg, once daily | "Targeted sample size of 30 subjects in each group provided 90% power to detect a 20% difference (2.2 mmol/L) in SSPG concentration. With 24 subjects per group, there was 82% power to detect a 20% difference. A difference of 20% was chosen because this is the degree of difference in SSPG concentration seen with modest weight loss of 7%." "Only subjects who had end‐of‐study testing were included in the analyses." |

161 | 35 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 68.6 | 14 weeks |

| C: placebo, once daily | 33 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 81.8 | ||||

| total: | 68 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 75 | ||||

|

Kelly 2012 (parallel RCT) |

I: exenatide 10 μg twice daily | ‐ | ‐ | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 100 | 3 months |

| C: metformin 1000 mg twice daily | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 100 | ||||

|

Martinez‐Abundis 2015 (parallel RCT) |

I: linagliptin 5 mg + placebo in the evening | ‐ | ‐ | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 100 | 90 days |

| C: metformin 500 mg twice daily | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 100 | ||||

| total: | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 100 | ||||

|

McLaughlin 2011 (parallel RCT) |

I: exenatide 10 μg twice daily | ‐ | ‐ | 32 | 32 | 32 | ‐ | ‐ | 30 weeks (1 year) |

| C: placebo | 34 | 34 | 34 | ‐ | ‐ | ||||

| total: | 66e | 66 | 66 | ‐ | ‐ | ||||

|

Rosenstock 2008 (parallel RCT) |

I: vildagliptin 50 mg once daily | ITT | 956 | 90 | 89 | 89 | 84 | 93.3 | 12 weeks |

| C: placebo | 89 | 89 | 89 | 84 | 94.4 | ||||

| total: | 179 | 178 | 178 | 168 | 93.9 | ||||

|

Rosenstock 2010 (parallel RCT) |

I: exenatide 10 μg twice daily | Includes participants that received at least 1 dose of study drug | 322b | ‐ | 17d | 17d | 17d | ‐ | 24 weeks |

| C: placebo | ‐ | 16d | 16d | 16d | ‐ | ||||

| total: | 38c | 33d | 33d | 33d | 86.8 | ||||

|

SCALE (parallel RCT) |

I: liraglutide 3.0 mg, once daily | "The power for the primary endpoint weight change is calculated based on a two sided t‐test with a significance level of 5%. The power with regard to the co‐primary dichotomous endpoints proportion of subjects with a weight loss of at least 5% or more than 10%, respectively, is calculated based on a two‐sided chi‐square test." "The large number of randomised subjects also provides sufficient power for the fourth primary endpoint new onset of diabetes among subjects with pre‐diabetes. The endpoint new onset of diabetes will be analysed using methods for analysis of interval censored failure time data. A conservative estimate of the power may be calculated as if the endpoint diabetes yes/no among completers during the 160 weeks is analysed by use of a two‐sided Chisquare test with a significance level of 5%. It is assumed that the annual conversion rate of subjects with pre‐diabetes to diabetes equals 7% among placebo treated subjects, whereas it is 60% lower, 2.1%, among liraglutide treated subjects. After 160 weeks of treatment with liraglutide/placebo, the percentage of subjects with diabetes is therefore equal to 1‐(1‐0.07)3 = 20% among liraglutide placebo treated subjects and 1‐(1‐0.021)3 = 6% among liraglutide treated subjects. It is assumed that the drop‐out during the 160 weeks may be as large as 65% in both groups. The power for conversion rates for placebo of 5, 7 and 9% and conversion rates 60 and 70% lower in the liraglutide group may be seen in Table 18‐1." From the numbers in Table 18‐1 following numbers are specified: "Based on these figures it is apparent that a sample size of 2400 liraglutide treated subjects and 1200 liraglutide placebo treated subjects will provide sufficient power also for the fourth primary endpoint onset of diabetes" "Missing values were imputed with the use of the last‐observation‐carried‐forward method for measurements made after baseline." |

4992b | Period week 0‐56: 1528 Period week 0‐172: 1505 |

1472f | 1472f | Period week 0‐56: 1110 Period week 0‐172: 783g |

Period week 0‐56: 72.6 Period week 0‐172: 52.0 |

160 weeks (172 weeks) |

| Period week 0‐56: 757 Period week 0‐172: 749 |

738f | 738f | Period week 0‐56: 505 Period week 0‐172: 327g |

Period week 0‐56: 66.7 Period week 0‐172: 43.7 |

|||||

| C: placebo | |||||||||

| total: | 2285 | 2210 | 2210 | 1110 | 48.6 | ||||

| Grand total | All interventionsh | ‐ | 1718 | 924 | ‐ | ||||

| All comparatorsh | 946 | 471 | |||||||

| All interventions and comparatorsi | 2702 | 1428j | |||||||

‐ denotes not reported.

aFollow‐up under randomised conditions until end of trial or if not available, duration of intervention; extended follow‐up refers to follow‐up of participants once the original study was terminated as specified in the power calculation. bTotal number of screened. cArticle stated that 38 participants out of the total randomised population had impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance, or both. dNumber retrieved from abstract. eOne of the abstracts reports that 68 participants were randomised and another abstract reports 66 participants. fThe SCALE had different number of participants included in the analyses depending on outcome. A full analyses set is reported in the table and was defined as: "All randomised subjects exposed to at least one dose of the trial product and with at least one post baseline assessment of any efficacy endpoint will be included. Subjects in the FAS will be analysed according to randomised treatment." Beside safety analysis set was defined as: "All randomised subjects who have been exposed to at least one dose of trial product. Subjects in the safety analysis set will be analysed "as treated" ". The number of participants started in the trial according to clinicaltrial.gov varied from the period of week 0 to week 56 and from week 0 to 172 due to misclassification of screened participants. gIn the publication reporting long‐term data, it was stated that 791 (53%) participants in the liraglutide group and 337 (15%) participants in the placebo group completed the trial (Le Roux 2017). hNot all trials described the number of participants randomised to each intervention/comparator group. iOne trial did not report the number of randomised participants per intervention group. Therefore, numbers do not add up accurately. jNot all trials reported the number of participants finishing the trial.

C: comparator; I: intervention; ITT: intention to treat; n: number of participants; N/A: not applicable; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SCALE: Satiety and Clinical Adiposity ‐ Liraglutide Evidence in Nondiabetic and Diabetic Individuals; SSPG: steady‐state plasma glucose.

We provided information about potentially relevant ongoing trials including trial identifier in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table and in Appendix 7 'Matrix of trial endpoint (publications and trial documents)'. For each included trial, we tried to retrieve the protocol. If not available from the search of the databases, reference screening or Internet searches, we asked authors to provide a copy of the protocol. Predefined outcomes were entered in a 'Matrix of trial endpoint (publications and trial documents)' (see Appendix 7).

We emailed all authors of the included trials to enquire whether they were willing to answer questions regarding their trials. We presented the results of this survey in 'Survey of trial investigators providing information on included trials' (see Appendix 14). We sought relevant missing information on the trial from the primary author(s) of the articles, if possible.

Dealing with duplicate and companion publications

In the event of duplicate publications, companion documents or multiple reports of a primary trial, we maximised the information yield by collating all available data and used the most complete data set aggregated across all known publications. Duplicate publications, companion documents or multiple reports of a primary trial would be listed as secondary references under the primary reference of the included, ongoing or excluded trial.

Data from clinical trial registers

If data of included trials were available as study results in clinical trial registers such as ClinicalTrials.gov or similar sources, we made full use of this information and extracted data. If there was also a full publication of the trial, we collated and critically appraised all available data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (BH and DS) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included trial. We resolved any disagreements by consensus, or by consultation with a third review author (BR). If adequate information was not available from the trial publication, trial protocol, or both we contacted trial authors for missing data on 'Risk of bias' items.

We used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011a; Higgins 2011b), and judged 'Risk of bias' criteria as 'low', 'high' or 'unclear' risk and evaluated individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a), where any of the specified criteria for a judgement on 'low', unclear' or 'high' risk of bias justified the associated categorisation.

Random sequence generation (selection bias due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence) ‐ assessment at trial level

We described for each included trial the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

Low risk of bias: sequence generation was achieved using computer random number generation or a random number table. Drawing of lots, tossing a coin, shuffling cards or envelopes, and throwing dice were adequate if performed by an independent person not otherwise involved in the trial. Use of the minimisation technique was considered as equivalent to being random.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information about the sequence generation process.

High risk of bias: the sequence generation method was non‐random (e.g. sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; sequence generated by some rule based on date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by some rule based on hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; allocation by preference of the participant; allocation based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; allocation by availability of the intervention). Such trials were excluded.

Allocation concealment (selection bias due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment) ‐ assessment at trial level

We described for each included trial the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment, or changed after assignment.

Low risk of bias: central allocation (including telephone, interactive voice‐recorder, web‐based and pharmacy‐controlled randomisation); sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information about the allocation concealment.

High risk of bias: used an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards; alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. Such trials were excluded.

We also evaluated trial baseline data to incorporate assessment of baseline imbalance into the 'Risk of bias' judgement for selection bias (Corbett 2014; Egbewale 2014; Riley 2013). Chance imbalances may also affect judgements on the risk of attrition bias. In the case of unadjusted analyses, we distinguished between trials we rated as at low risk of bias on the basis of both randomisation methods and baseline similarity, and trials rated as at low risk of bias on the basis of baseline similarity alone (Corbett 2014). We reclassified judgements of unclear, low or high risk of selection bias as specified in 'Selection bias decisions' (Appendix 18).

Blinding of participants and study personnel (performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the trial) ‐ assessment at outcome level

We evaluated the risk of performance bias separately for each outcome (Hróbjartsson 2013). We noted whether outcomes were self‐reported, investigator‐assessed or adjudicated outcome measures (see below).

Low risk of bias: blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken; no blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judged that the outcome was not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information about the blinding of participants and study personnel; the trial did not address this outcome.

High risk of bias: no blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome was likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of trial participants and key personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome was likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessment) ‐ assessment at outcome level

We evaluated the risk of detection bias separately for each outcome (Hróbjartsson 2013). We noted whether outcomes were self‐reported, investigator‐assessed or adjudicated outcome measures (see below).

Low risk of bias: blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken; no blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judged that the outcome measurement was not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information about the blinding of outcome assessors; the trial did not address this outcome.

High risk of bias: no blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement was likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement was likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data) ‐ assessment at outcome level

We described for each included trial, and for each outcome, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the number included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the number of randomised participants per intervention/comparator groups), if reasons for attrition or exclusion were reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. We considered the implications of missing outcome data per outcome such as high dropout rates (e.g. above 15%) or disparate attrition rates (e.g. difference of 10% or more between trial arms).

Low risk of bias: no missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD)) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; appropriate methods, such as multiple imputation, were used to handle missing data.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information to assess whether missing data in combination with the method used to handle missing data were likely to induce bias; the trial did not address this outcome.

High risk of bias: reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (MD or SMD) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; 'as‐treated' or similar analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation.

Selective reporting (reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting) ‐ assessment at trial level

We assessed outcome reporting bias by integrating the results of the appendix 'Matrix of trial endpoints (publications and trial documents' (Appendix 7) (Boutron 2014; Mathieu 2009), with those of the appendix 'High risk of outcome reporting bias according to ORBIT classification' (Appendix 8) (Kirkham 2010). This analysis formed the basis for the judgement of selective reporting.

Low risk of bias: the trial protocol was available and all the trial's prespecified (primary and secondary) outcomes that were of interest in the review were reported in the prespecified way; the study protocol was not available but it was clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes (ORBIT classification).

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information about selective reporting.

High risk of bias: not all the trial's prespecified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes was reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not prespecified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified (unless clear justification for their reporting was provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review were reported incompletely so that they could not be entered in a meta‐analysis; the trial report failed to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a trial (ORBIT classification).

Other bias (bias due to problems not covered elsewhere) ‐ assessment at trial level

Other risk of bias reflected other circumstances that may threaten the validity of the trials.

Low risk of bias: the trial appeared to be free of other sources of bias.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias existed; insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem introduced bias.

High risk of bias: had a potential source of bias related to the specific trial design used; has been claimed to have been fraudulent; had some other serious problem.

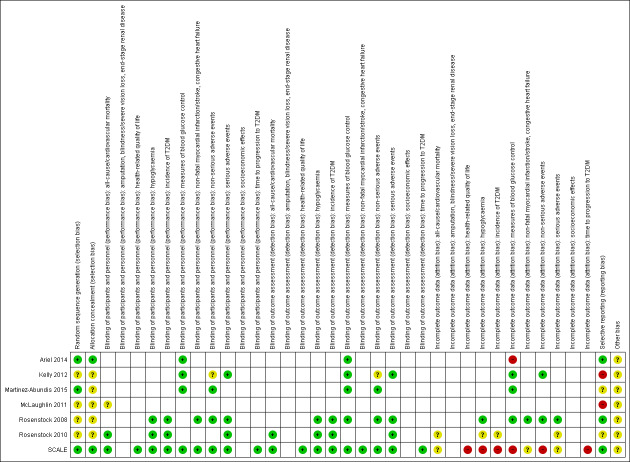

We established a 'Risk of bias' graph and a 'Risk of bias' summary figure.

We distinguished between self‐reported, investigator‐assessed and adjudicated outcome measures.

We defined the following outcomes as self‐reported.

Non‐serious adverse events.

Hypoglycaemia, if reported by participants.

HRQoL.

Measures of blood glucose control, if measured by trial participants.

We defined the following outcomes as investigator‐assessed.

All‐cause mortality.

Incidence of T2DM.

Serious adverse events.

Cardiovascular mortality.

Non‐fatal myocardial infarction.

Non‐fatal stroke.

Congestive heart failure.

Amputation of lower extremity.

Blindness or severe vision loss.

End‐stage renal disease.

Hypoglycaemia, if measured by trial personnel.

Time to progression to T2DM.

Blood glucose control, if measured by trial personnel.

Socioeconomic effects.

Summary assessment of risk of bias

Risk of bias for a trial across outcomes: some risk of bias domains, such as selection bias (sequence generation and allocation sequence concealment), affected the risk of bias across all outcome measures in a trial. Otherwise, we did not perform a summary assessment of the risk of bias across all outcomes for a trial. In case of high risk of selection bias, we excluded the trial.

Risk of bias for an outcome within a trial and across domains: we assessed the risk of bias for an outcome measure by including all entries relevant to that outcome (i.e. both trial‐level entries and outcome‐specific entries). 'Low' risk of bias was defined as low risk of bias for all key domains, 'unclear' risk of bias as unclear risk of bias for one or more key domains and 'high' risk as high risk of bias for one or more key domains.

Risk of bias for an outcome across trials and across domains: these were our main summary assessments that were incorporated in our judgements about the quality of evidence in the 'Summary of findings' tables. 'Low' risk of bias was defined as most information coming from trials at low risk of bias, 'unclear' risk of bias as most information coming from trials at low or unclear risk of bias and 'high' risk of bias as sufficient proportion of information coming from trials at high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

When at least two trials were available for a comparison of a given outcome, we expressed dichotomous data as risk ratio (RR) with 95% CIs and with Trial Sequential Analysis (TSA)‐adjusted 95% CIs if the diversity‐adjusted required information size was not reached. We expressed continuous data reported on the same scale as MD with 95% CIs and with TSA‐adjusted 95% CIs if the diversity‐adjusted required information size was not reached. For trials addressing the same outcome but using different outcome measure scales, we used SMD with 95% CI. We planned to calculate time‐to‐event data as HR with 95% CI with the generic inverse variance method. Unadjusted HRs would have been preferred, as adjustment may differ among the included trials. For outcomes meta‐analysed as SMD and the generic inverse variance method, we are presently unable to conduct TSA and adjust the 95% CIs.

The scales measuring HRQoL may go in different directions. Some scales increase in values with improved HRQoL, whereas other scales decrease in values with improved HRQoL. To adjust for the different directions of the scales, we planned to multiply the scales that reported better HRQoL with decreasing values by ‐1.

Unit of analysis issues

We took into account the level at which randomisation occurred, such as cross‐over trials, cluster‐randomised trials and multiple observations for the same outcome. If more than one comparison from the same trial was eligible for inclusion in the same meta‐analysis, we would have either combined groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison or appropriately reduced the sample size so that the same participants do not contribute multiply (splitting the 'shared' group into two or more groups). While the latter approach offers some solution to adjusting the precision of the comparison, it does not account for correlation arising from the same set of participants being in multiple comparisons (Higgins 2011a).

We planned to reanalyse cluster‐randomised trials that did not appropriately adjust for potential clustering of participants within clusters in their analyses. The variance of the intervention effects was planned to be inflated by a design effect (DEFF). Calculation of a DEFF involves estimation of an intra‐cluster correlation (ICC). We planned to obtain estimates of ICCs through contact with authors, or impute using estimates from other included studies that report ICCs, or using external estimates from empirical research (e.g. Bell 2013). We planned to examine the impact of clustering using sensitivity analyses.

Dealing with missing data

We tried to obtain missing data from trial authors and carefully evaluate important numerical data such as screened, randomly assigned participants as well as intention‐to‐treat (ITT), and as‐treated and per‐protocol populations.

We investigated attrition rates (e.g. dropouts, losses to follow‐up, withdrawals), and we critically appraised issues concerning missing data and imputation methods (e.g. last observation carried forward (LOCF)).

We converted standard errors and CIs to standard deviations (SD) (Higgins 2011a). When there were no differences in means and SDs from baseline, we used the end‐of follow‐up values (Higgins 2011a). Where means and SDs for outcomes were not reported and we did not receive the needed information from trial authors, we calculated the SDs from standard errors, if possible. Otherwise, we would have imputed the values by assuming the SDs of the missing outcome to be the mean of the SDs from the trials that reported this information.

We planned to investigate the impact of imputation on meta‐analyses by performing sensitivity analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the event of substantial clinical or methodological heterogeneity, we planned not to report trial results as the pooled effect estimate in a meta‐analysis.

We investigated heterogeneity (inconsistency) by visually inspecting the forest plots and by using a standard Chi² test with a significance level of 0.1. In view of the low power of this test, we also considered the I² statistic, which quantifies inconsistency across trials to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003); an I² statistic of 75% or greater indicated a considerable level of heterogeneity (Higgins 2011a).

Assessment of reporting biases

If we included 10 or more trials investigating a particular outcome, we planned to use funnel plots to assess small‐trial effects. Several explanations may account for funnel plot asymmetry, including true heterogeneity of effect with respect to trial size, poor methodological design (and hence bias of small trials) and publication bias. Therefore, we planned to interpret results carefully (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

Unless good evidence showed homogeneous effects across trials, we would primarily summarise low risk of bias data using a random‐effects model (Wood 2008). We interpreted random‐effects meta‐analyses with consideration to the whole distribution of effects, ideally by presenting a prediction interval (Higgins 2009). A prediction interval specifies a predicted range for the true treatment effect in an individual trial (Riley 2011). In addition, we performed statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a).

Trial Sequential Analyses

In a single trial, sparse data and interim analyses increase the risk of type I and type II errors. To avoid type I errors, group sequential monitoring boundaries are applied to decide whether a trial could be terminated early because of a sufficiently small P value (i.e. the cumulative Z‐curve crosses the monitoring boundaries) (Lan 1983). Likewise, before reaching the planned sample size of a trial, the trial may be stopped due to futility if the cumulative Z‐score crosses the futility monitoring boundaries (Higgins 2011a). Sequential monitoring boundaries for benefit, harm or futility can be applied to meta‐analyses as well (termed trial sequential monitoring boundaries) (Higgins 2011c; Wetterslev 2008). In TSA, the addition of each trial in a cumulative meta‐analysis is regarded as an interim meta‐analysis and helps to clarify whether significance or futility is reached, or whether additional trials are needed (Wetterslev 2008).

TSA combines a calculation of the diversity‐adjusted required information size (cumulated meta‐analysis sample size to detect or reject a specific relative intervention effect) for meta‐analysis with the threshold of data associated with statistics. We performed TSA on all outcomes (Brok 2009; Pogue 1997; Wetterslev 2008).

The idea in TSA is that if the cumulative Z‐curve crosses the boundary for benefit or harm before a diversity‐adjusted required information size is reached, a sufficient level of evidence for the anticipated intervention effect has been reached with the assumed type I error and no further trials may be needed. If the cumulative Z‐curve crosses the boundary for futility before a diversity‐adjusted required information size is reached, the assumed intervention effect can be rejected with the assumed type II error and no further trials may be needed. If the Z‐curve does not cross any boundary, then there is insufficient evidence to reach a conclusion. To construct the trial sequential monitoring boundaries, the required information size is needed and is calculated as the least number of participants needed in a well‐powered single trial and subsequently adjusted for diversity among the included trials in the meta‐analysis (Brok 2009; Wetterslev 2008). We applied TSA as it decreases the risk of type I and II errors due to sparse data and multiple updating in a cumulative meta‐analysis, and it provides us with important information to estimate the risks of imprecision when the required information size is not reached. Additionally, TSA provides important information regarding the need for additional trials and the required information size of such trials (Wetterslev 2008).

We applied trial sequential monitoring boundaries according to an estimated clinically important effect. We based the required information size on an a priori effect corresponding to a 10% relative risk reduction (RRR) for beneficial effects of the interventions and a 30% relative risk increase for harmful effects of the interventions.

TSA for continuous outcomes was performed with MDs, by using trials applying the same scale to calculate the required sample size. For continuous outcomes, we tested the evidence for the achieved differences in cumulative meta‐analyses.

For adjustment of heterogeneity of the required information size we used the diversity (D²) estimated in the meta‐analyses of included trials. When diversity was zero in a meta‐analysis, we performed a sensitivity analysis using an assumed diversity of 20%.

Quality of evidence

We presented the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome according to the GRADE approach, which takes into account issues relating not only to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias) but also to external validity, such as directness of results. Two review authors (BH and DS) independently rated the quality of evidence for each outcome. We presented a summary of the evidence in Table 1; Table 2. This provides key information about the best estimate of the magnitude of the effect, in relative terms and as absolute differences, for each relevant comparison of alternative management strategies, the numbers of participants and trials addressing each important outcome, and rates the overall confidence in effect estimates for each outcome. We created the 'Summary of findings' tables on the basis of methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a) by means of the table editor in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014), and included two appendices (Appendix 17; Appendix 18) providing checklists as guides to the consistency and reproducibility of GRADE assessments (Meader 2014) to help with the standardisation of the 'Summary of findings' tables. Alternatively, we would have used the GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT 2015) and presented evidence profile tables as an appendix. We presented results for the outcomes as described in the Types of outcome measures section. If meta‐analysis was not possible, we presented the results in a narrative format in the 'Summary of findings' tables. We justified all decisions to downgrade the quality using footnotes, and we made comments to aid the reader's understanding of the review where necessary.

Summary of findings for the main comparison. DPP‐4 inhibitors for prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications in people at risk for the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

| DPP‐4 inhibitors for prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications in people at risk for the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus | ||||||

|

Population: people at risk for development of T2DM Settings: outpatients Intervention: DPP‐4 inhibitors Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trial(s)) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | DPP‐4 inhibitors | |||||

|

All‐cause mortality Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

See comment | See comment | See comment | 179 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | 1 trial on vildagliptin reported that none of the participants died (Rosenstock 2008) |

|

Incidence of T2DM Definition: WHO criteria Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

See comment | See comment | See comment | 179 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | 1 trial reported that 3/90 in the vildagliptin group vs 1/89 in the placebo group developed T2DM (Rosenstock 2008) |

|

Serious adverse events Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

See comment | See comment | See comment | 179 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | 1 trial reported that 1/90 in the vildagliptin group vs 2/89 in the placebo group experienced a serious adverse event (Rosenstock 2008) |

|

Cardiovascular mortality Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

See comment | See comment | See comment | 179 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | 1 trial reported that none of the participants died (Rosenstock 2008) |

|

(1) Non‐fatal myocardial infarction (2) Non‐fatal stroke (3) Congestive heart failure Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

See comment | See comment | See comment | (1) ‐ (2) ‐ (3) 179 (1) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | (1) + (2): not reported (3): 1 trial on vildagliptin reported 1/90 in the vildagliptin group vs 0/89 in the placebo group experienced heart failure (Rosenstock 2008) |

| Health‐related quality of life | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | Not reported |

| Socioeconomic effects | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | Not reported |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across trials) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; DPP‐4: dipeptidyl‐peptidase‐4; RR: risk ratio; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; WHO: World Health Organization. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

*Assumed risk was derived from the event rates in the comparator groups.

aDowngraded by three levels because of indirectness, imprecision (very sparse data) and risk of publication bias (see Appendix 15).

Summary of findings 2. GLP‐1 analogues for prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications in people at risk for the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

| GLP‐1 analogues for prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications in people at risk for the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus | ||||||

|

Population: people at risk for development of T2DM Settings: outpatients Intervention: GLP‐1 analogues Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Placebo | GLP‐1 analogues | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (trial(s)) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

All‐cause mortality Follow‐up: up to 172 weeks |

See comment | See comment | See comment | 2281 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | 1 trial reported that 2/1501 in the liraglutide group vs 2/747 in the placebo group died after 160 weeks of intervention. Liraglutide used in doses approved for weight‐reducing purposes (3.0 mg) (SCALE). 1 trial using exenatide reported that none of the participants died (Rosenstock 2010) |

|

Incidence of T2DM Definition/description: 1 trial established the diagnosis of T2DM defined as HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, or fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, or 2‐hour plasma glucose post‐challenge (oral glucose tolerance test) ≥ 11.1 mmol/L (SCALE). Other trial did not report how the diagnosis of T2DM was established. Follow‐up: up to 172 weeks |

See comment | See comment | See comment | 2243 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | At 160 weeks, 26/1472 (1.8%) participants in the liraglutide group vs 46/738 (6.2%) participants in the placebo group developed T2DM (SCALE). The incidence of T2DM after the 12‐week off‐treatment extension period (i.e. after 172 weeks) showed that 5 additional participants were diagnosed with T2DM in the liraglutide group, compared with 1 participant in the placebo group. Liraglutide used in doses approved for weight‐reducing purposes (3.0 mg). 1 trial reported that 2/17 in the exenatide group vs1/16 in the placebo group developed T2DM (Rosenstock 2010) |

|

Serious adverse events Follow‐up: up to 172 weeks |

See comment | See comment | See comment | 2312 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | 1 trial on liraglutide reported that 227/1501 (15.1%) participants in the liraglutide 3.0 mg group vs 96/747 (12.7%) participants in the placebo group experienced a serious adverse event after 160 weeks (SCALE). 1 trial on exenatide reported that none of the participants experienced a serious adverse event (Rosenstock 2010) |

|

Cardiovascular mortality Follow‐up: up to 172 weeks |

See comment | See comment | See comment | 2281 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | 1 trial reported that none of the participants died (Rosenstock 2010). 1 trial reported that 1/1501 participants in the liraglutide group died from cardiac arrest; no participant in the placebo group died of cardiovascular reasons (SCALE). |

|

(1) Non‐fatal myocardial infarction (2) Non‐fatal stroke (3) Congestive heart failure Follow‐up: up to 172 weeks |

See comment | See comment | See comment | (1) 2279 (1) (2) See comments (3) 2279 (1) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | (1) 1 trial reported 1/1524 participants in the liraglutide 3.0 mg group vs 0/755 participants in the placebo group (SCALE) (2) Not reported (3) 1 trial reported 1/1524 in the liraglutide 3.0 mg group vs 1/755 participants in the placebo group (SCALE) |

|

Health‐related quality of life SF‐36 scale: total score 0‐100, 8 subscales. Higher values mean better health‐related quality of life. Follow‐up: 160 weeks |

See comment | See comment | See comment | 1791 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | Physical functioning component score had mean difference of 0.87 in favour of liraglutide (SCALE) |

| Socioeconomic effects | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | Not reported |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across trials) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GLP‐1: glucagon‐like peptide‐1; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin A1c; RR: risk ratio; SF‐36: 36‐item Short Form health survey; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by three levels because of indirectness, imprecision (sparse data) and risk of attrition and publication bias (see Appendix 16). bDowngraded by two levels because of imprecision (sparse data) and risk of attrition and publication bias (see Appendix 16).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We expected the following characteristics to introduce clinical heterogeneity, and planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses with investigation of interactions.

Type of DPP‐4 inhibitor or GLP‐1 analogue.

Trials with long duration (two years or greater) versus trials with short duration (less than two years).

Diagnostic criteria (IFG, IGT, HbA1c).

Age, depending on data.

Gender.

Ethnicity, depending on data.

Comorbid conditions, such as hypertension, obesity, or both.

Participants with previous gestational diabetes mellitus.

GLP‐1 analogues dose (up to the recommended dose for a glucose‐lowering effect in people with T2DM versus higher doses).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the certain factors (when applicable) on effect sizes by restricting analysis to the following.

Published trials.

Taking into account risk of bias, as specified in the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section.

Very long or large trials, to establish the extent to which they dominated the results.

Trials using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, imputation, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other) or country.

Results

Description of studies

For a detailed description of trials, see Table 3; and the Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

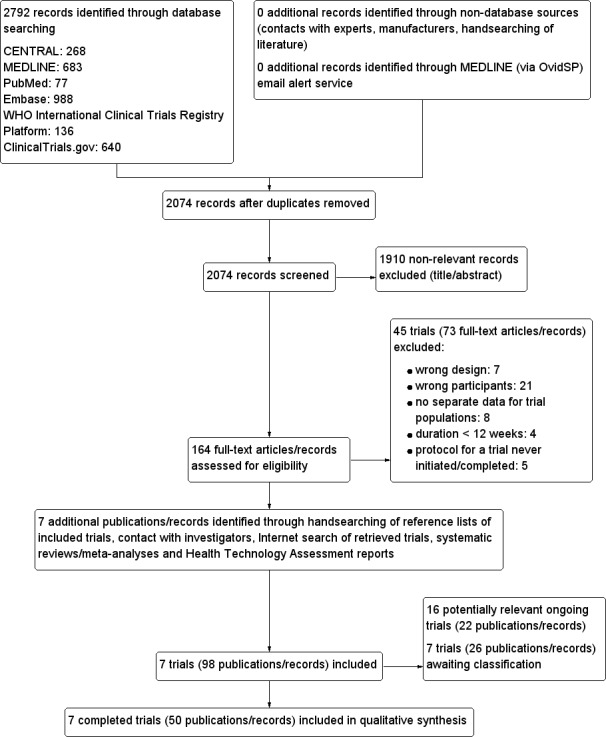

Results of the search

The initial search of the databases identified 2074 records after duplicates were removed. The applied MEDLINE (via OvidSP) email alert service established by the CMED Group to identify newly published trials using the same search strategy as described for MEDLINE (for details on search strategies, see Appendix 2) did not identify any additional references. We excluded most of the references on the basis of their titles and abstracts because they clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). We evaluated 164 references further. After screening the full texts, seven RCTs published in 50 records met our inclusion criteria. One trial published in three references did not report any of the primary or secondary outcomes of this review (McLaughlin 2011). The trial was only published in abstracts. The investigators were asked for additional data, but stated they would not provide additional data before the trial was published in full (McLaughlin 2011) (see Appendix 14).

1.

Study flow diagram.

We excluded 73 references after full‐text evaluation.