Abstract

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic auto‐immune disorder that causes widespread and persistent inflammation of the synovial lining of joints and tendon sheaths. Presently, there is no cure for rheumatoid arthritis and treatment focuses on managing symptoms such as pain, stiffness and mobility, with the aim of achieving stable remission and improving mobility. Celecoxib is a selective non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID) used for treatment of people with rheumatoid arthritis.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of celecoxib in people with rheumatoid arthritis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase and clinical trials registers (ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization trials portal) to May 18, 2017. We also searched the reference and citation lists of included studies.

Selection criteria

We included prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared oral celecoxib (200 mg and 400 mg daily) versus no intervention, placebo or a traditional NSAID (tNSAID) in people with confirmed rheumatoid arthritis, of any age and either sex. We excluded studies with fewer than 50 participants in each arm or had durations of fewer than four weeks treatment.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by The Cochrane Collaboration.

Main results

We included eight RCTs with durations of 4 to 24 weeks, published between 1998 and 2014 that involved a total of 3988 adults (mean age = 54 years), most of whom were women (73%). Participants had rheumatoid arthritis for an average of 9.2 years. All studies were assessed at high or unclear risk of bias in at least one domain. Overall, evidence was assessed as moderate‐to‐low quality. Five studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies.

Celecoxib versus placebo

We included two studies (N = 873) in which participants received 200 mg daily or 400 mg daily or placebo. Participants who received celecoxib showed significant clinical improvement compared with those receiving placebo (15% absolute improvement; 95% CI 7% to 25%; RR 1.53, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.86; number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) = 7, 95% CI 5 to 13; 2 studies, 873 participants; moderate to low quality evidence).

Participants who received celecoxib reported less pain than placebo‐treated people (11% absolute improvement; 95% CI 8% to 14%; NNTB = 4, 95% CI 3 to 6; 1 study, 706 participants) but results were inconclusive for improvement in physical function (MD ‐0.10, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.10; 1 study, 706 participants).

In the celecoxib group, 15/293 participants developed ulcers, compared with 4/99 in the placebo group (Peto OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.44 to 3.63; 1 study, 392 participants; low quality evidence). Nine (of 475) participants in the celecoxib group developed short‐term serious adverse events, compared with five (of 231) in the placebo group (Peto OR 0.87 (0.28 to 2.69; 1 study, 706 participants; low quality evidence).

There were fewer withdrawals among people who received celecoxib (163/475) compared with placebo (130/231) (22% absolute change; 95% CI 16% to 27%; RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.72; 1 study, 706 participants).

Cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke) were not reported. However, regulatory agencies warn of increased cardiovascular event risk associated with celecoxib.

Celecoxib versus tNSAIDs

Seven studies (N = 2930) compared celecoxib and tNSAIDs (amtolmetin guacyl, diclofenac, ibuprofen, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, pelubiprofen); one study included comparisons of both placebo and tNSAIDs (N = 1149).

There was a small improvement, which may not be clinically significant, in numbers of participants achieving ACR20 criteria response in the celecoxib group compared to tNSAIDs (4% absolute improvement; 95% CI 0% less improvement to 8% more improvement; RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.23; 4 studies, 1981 participants). There was a lack of evidence of difference between participants in the celecoxib and tNSAID groups in terms of pain or physical function. Results were assessed at moderate‐to‐low quality evidence (downgraded due to risk of bias and inconsistency).

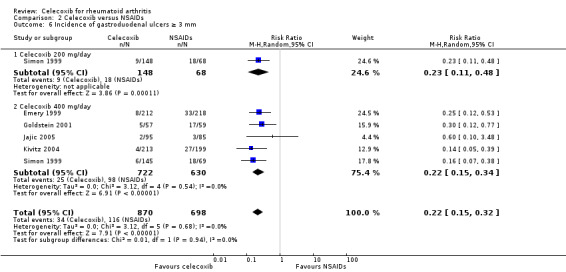

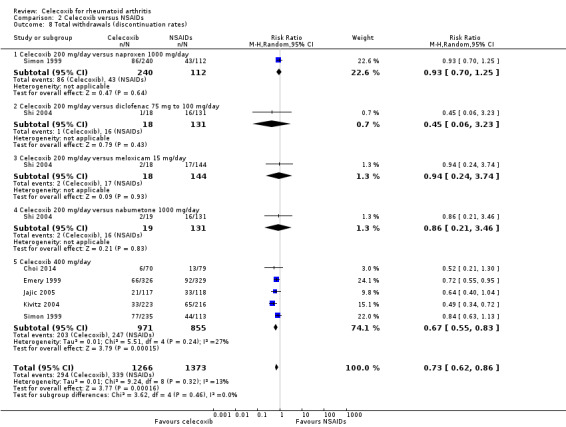

People who received celecoxib had a lower incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm (34/870) compared with those who received tNSAIDs (116/698). This corresponded to 12% absolute change (95% CI 11% to 13%; RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.32; 5 studies, 1568 participants; moderate quality evidence). There were 7% fewer withdrawals among people who received celecoxib (95% CI 4% to 9%; RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.86; 6 studies, 2639 participants).

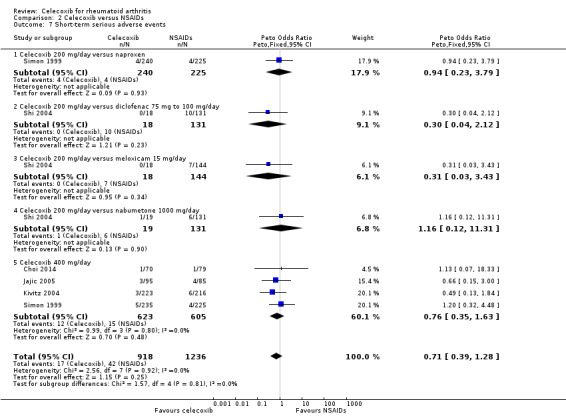

Results were inconclusive for short‐term serious adverse events and cardiovascular events (low quality evidence). There were 17/918 serious adverse events in people taking celecoxib compared to 42/1236 among people who received placebo (Peto OR 0.71; 95% CI 0.39 to 1.28; 5 studies, 2154 participants). Cardiovascular events were reported in both celecoxib and placebo groups in one study (149 participants).

Authors' conclusions

Celecoxib may improve clinical symptoms, alleviate pain and contribute to little or no difference in physical function compared with placebo. Celecoxib was associated with fewer numbers of participant withdrawals. Results for incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers (≥ 3 mm) and short‐term serious adverse events were uncertain; however, there were few reported events for either.

Celecoxib may slightly improve clinical symptoms compared with tNSAIDs. Results for reduced pain and improved physical function were uncertain. Particpants taking celecoxib had lower incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers (≥ 3 mm) and there were fewer withdrawals from trials. Results for cardiovascular events and short‐term serious adverse events were also uncertain.

Uncertainty about the rate of cardiovascular events between celecoxib and tNSAIDs could be due to risk of bias; another factor is that these were small, short‐term trials. It has been reported previously that both celecoxib and tNSAIDs increase cardiovascular event rates. Our confidence in results about harms is therefore low. Larger head‐to‐head clinical trials comparing celecoxib to other tNSAIDs is needed to better inform clinical practice.

Keywords: Humans; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/adverse effects; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/therapeutic use; Arthritis, Rheumatoid; Arthritis, Rheumatoid/drug therapy; Celecoxib; Celecoxib/adverse effects; Celecoxib/therapeutic use; Myocardial Infarction; Myocardial Infarction/chemically induced; Myocardial Infarction/epidemiology; Pain Measurement; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Stomach Ulcer; Stomach Ulcer/chemically induced; Stomach Ulcer/epidemiology; Stroke; Stroke/chemically induced; Stroke/epidemiology; Treatment Outcome

Plain language summary

Benefits and harms of celecoxib for treating people with rheumatoid arthritis

Review question

We aimed to assess the benefits (improvement in pain, stiffness, physical function) and harms (gut and heart problems) of celecoxib compared with other similar drugs or a fake drug (placebo) for adults with rheumatoid arthritis.

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis is an auto‐immune disease that causes the lining of joints to become inflamed making them painful, stiff and swollen. The small joints of hands and feet are usually affected first. Presently, there is no cure; treatment aims to achieve remission or delay disease progression to improve mobility and reduce pain, swelling and stiffness. Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are used to treat people with rheumatoid arthritis. Celecoxib is a selective NSAID which may help to relieve symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

Search date

We searched for evidence up to May 18, 2017.

Study characteristics

We included eight studies published between 1998 and 2014 that involved 3988 adults (average age 54 years), most of whom were women (73%). Participants had rheumatoid arthritis for an average of 9.2 years.

Studies compared celecoxib with another treatment; 1786 participants received celecoxib and 2202 received either placebo or a traditional NSAID (tNSAID).

Five studies were supported or funded by the pharmaceutical industry.

Key results

When compared with placebo, of every 100 people who received celecoxib, 15 had symptom improvement after 4 to 12 weeks. People who took celecoxib rated their pain 11 points lower (on a scale of 0 to 100) after 12 weeks.

Results were inconclusive about improvements in physical function and numbers of people who developed gastroduodenal ulcers over 3 mm diameter when we compared celecoxib and placebo. Evidence was also inconclusive about harms that appear shortly after use of the drugs. None of the studies that compared celecoxib and placebo reported heart attacks or strokes.

Results about improvement in pain and physical function were inconclusive when celecoxib was compared with tNSAIDs. A small improvement was found in relation to a scoring system (ACR20) used by doctors to assess people with rheumatoid arthritis. Of every 100 people who took celecoxib: 13 fewer developed gastroduodenal ulcers over 3 mm diameter; and 7 fewer withdrew from studies compared with people receiving tNSAIDs.

Celecoxib may improve rheumatoid arthritis symptoms and alleviate pain more than placebo, but probably provides little or no difference in physical function improvement.

Quality of evidence

Evidence was rated as moderate or low quality due to methodological shortcomings and few observed events indicating harms.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Celecoxib versus placebo.

|

Patient or population: people with rheumatoid arthritis Setting: ambulatory Intervention: celecoxib 200 mg daily and 400 mg daily Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with celecoxib | |||||

| Clinical improvement: American College of Rheumatology 20% improvement criteria (ACR20) follow up: range 4 weeks to 12 weeks | 288 per 1000 | 441 per 1000 (360 to 536) | RR 1.53 (1.25 to 1.86) | 873 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | 15% absolute improvement (95% CI 7% to 25%), 53% relative improvement (95% CI 25% to 86%), NNTB 7 (95% CI 5 to 13)² |

| Pain: self‐reported visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 to 100 points (where 0 is no pain) follow up: 12 weeks | Mean pain = 60 | Mean pain in the celecoxib group was 11 points lower (14.04 lower to 7.96 lower) | ‐ | 706 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | 11% absolute improvement (95% CI 8% to 14%), 18% relative improvement (95% CI 13% to 23%), MD ‐11.00 (95% CI ‐14.04 to ‐7.96), NNTB 4 (95% CI 3 to 6)³ |

| Physical function: Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ) scale 0 to 3; higher scores means worse functional ability; follow up: 12 weeks | Mean change in physical function = ‐0.1 | Mean change in physical function in the intervention group was 0.1 point better (0.29 better to 0.1 worse) | ‐ | 706 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low¹4 | 3.3% absolute improvement (95% CI 9.6% better to 3.3% worse); 1% relative improvement (2.9% better to 1% worse), MD = ‐0.10 (95% CI ‐0.29 to 0.10) (NNTB = NA) |

| Cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke) | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | (0 studies) | No studies reported this outcome | |

| Incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm follow up: 12 weeks | 40 per 1000 | 51 per 1000 (17 to 142) | Peto OR 1.26 (0.44 to 3.63)⁶ | 392 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low¹ 7 | Celecoxib group had more participants with gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm, but CI is wide. 1% absolute change (95% CI 4% less to 6% more), 26% relative change (95% CI 56% less to 263% more) (NNTH = NA) |

| Short‐term serious adverse events follow up: 12 weeks | 22 per 1000 | 19 per 1000 (6 to 55) | Peto OR 0.87 (0.28 to 2.69)⁶ |

706 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low¹ 7 | Celecoxib group had fewer SAEs, but CI is wide. 0% absolute change (95% CI 2% less to 2% more), 13% relative change (95% CI 72% less to 169% more) (NNTH = NA) |

| Total withdrawals; follow up: 12 weeks | 563 per 1000 | 343 per 1000 (293 to 405) | RR 0.61 (0.52 to 0.72) | 706 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low¹ 7 | Celecoxib group had fewer withdrawals. 22% absolute change (95% CI 16% to 27% less), 39% relative change (28% to 48% less), NNTH⁵ (95% CI 4 to 7)⁵ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; NA: not applicable; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to harm; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SAE: serious adverse event; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

¹ Downgraded one level for study limitations: all trials had high or unclear risk of at least one type of bias.

² Number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) calculated using online calculator: http://www.nntonline.net/visualrx/.

³ Number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) for continuous outcomes calculated using the Wells calculator (from the CMSG Editorial office; http://musculoskeletal.cochrane.org/).

⁴ Downgraded one level due to inconsistency: high heterogeneity..

⁵ Number needed to harm (NNTH) calculated using online calculator: http://www.nntonline.net/visualrx/.

⁶ Report Peto OR which can be interpreted as an RR due to the low event rate.

⁷ Downgraded one level due to imprecision: few events

Summary of findings 2. Celecoxib versus traditional NSAIDs.

|

Patient or population: people with rheumatoid arthritis Setting: ambulatory Intervention: celecoxib Comparison: NSAIDs | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with NSAIDs | Risk with celecoxib | |||||

| Clinical improvement: American College of Rheumatology 20% improvement criteria (ACR20) follow up: range 6 weeks to 24 weeks | 457 per 1000 | 503 per 1000 (453 to 562) | RR 1.10 (0.99 to 1.23) | 1981 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | 4% absolute improvement (95% CI 0% to 8% more), 10% relative improvement (1% less to 23% more) (NNTB = NA) |

| Pain: self‐reported visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 to 100 (where 0 is no pain) follow up: range 6 weeks to 24 weeks | Mean pain = 47 | Mean pain in the intervention group was 1.59 points lower (3.83 better to 0.65 worse) | ‐ | 1504 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | 2% absolute improvement (95% CI 3.83% better to 0.65% worse), 3% relative improvement (95% CI 8% better to 1% worse), MD = ‐1.59 (95% CI ‐3.83 to 0.65) (NNTB = NA) |

| Physical function: Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ) scale 0 to 3; higher scores means worse functional ability; follow up: range 6 weeks to 12 weeks | Mean physical function = ‐0.2 points | Mean physical function in the intervention group was not different (0 points) (0.13 better to 0.13 worse) | ‐ | 849 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low¹ 2 | 0% absolute change (95% CI 4% better to 4% worse), 0% relative change (95% CI 65% better to 65% worse), MD = 0.00 (95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.13) (NNTB = NA) |

| Cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke) follow up: 6 weeks | 13 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (1 to 191) | Peto OR 1.13 (0.07 to 18.33)⁴ | 149 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low¹ 5 | Celecoxib group had more cardiovascular events, but CI was wide. 0% absolute change (95% CI 4% less to 4% more), 13% relative change (95% CI 93% less to 1733% more) (NNTH = NA) |

| Incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm follow up: range 12 weeks to 24 weeks | 155 per 1000 | 34 per 1000 (24 to 50) | RR 0.21 (0.14 to 0.32) | 1568 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | 12% absolute change (95% CI 11% to 13%), 21% relative change (95% CI 14% to 32%), NNTH 9 (95% CI 8 to 10)³ |

| Short‐term serious adverse events follow up: range 6 weeks to 24 weeks | 34 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (15 to 48) | Peto OR 0.71 (0.39 to 1.28)⁴ | 2154 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low¹5 | 1% absolute change (95% CI 2% less to 1% more), 29% relative change (95% CI 61% less to 28% more), (NNTH = NA) |

| Total withdrawals; follow up: range 6 weeks to 24 weeks | 247 per 1000 | 180 per 1000 (153 to 212) | RR 0.73 (0.62 to 0.86) | 2639 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | 7% absolute change (95% CI 4% to 9%), 27% relative change (95% CI 14% to 38%), NNTH = 14 (95% CI 11 to 23)³ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; NA: not applicable; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to harm; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

¹ All trials had high or unclear risk of at least one type of bias.

² Downgraded one level due to inconsistency: high heterogeneity

³ Number needed to harm (NNTH) calculated using online calculator: http://www.nntonline.net/visualrx/.

⁴ Report Peto OR which can be interpreted as an RR due to the low event rate.

⁵ .Few events.

Background

Description of the condition

Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic auto‐immune disorder that causes widespread and persistent inflammation of the synovial lining of the joints and tendon sheaths. Persistent inflammation results in many systemic and extra‐articular manifestations involving most organ systems, leading to severe complications and comorbidities such as rheumatoid lung, carditis, vasculitis, cachexia, anemia, accelerated atherosclerosis, myocardial and cerebrovascular disease, lymphoma, osteoporosis, and depression. Complications and comorbidities lead to disability, social dysfunction and premature death (McInnes 2011). Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis focuses on managing symptoms such as pain, stiffness and limited mobility (Aletaha 2005). Incidence is related to environmental factors such as smoking, infections, immunizations, obesity and socio‐economic status (Myasoedova 2010). Smoking is the principal risk for development of rheumatoid arthritis (Scott 2010).

The global prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in 2010 was estimated to be 0.24% and was approximately twice as high in women than men (Cross 2014). There has been no discernible change in prevalence since 1990 (Cross 2014). Rheumatoid arthritis prevalence peaks in older age; it is expected that the number of people living with rheumatoid arthritis will increase in the future (Cross 2014).

Description of the intervention

At present, there is no cure for rheumatoid arthritis; treatment focuses on management of symptoms. Current treatments include pharmacological interventions, physical therapy and balneotherapy (bathing in mineral‐rich water). Pharmacotherapeutic options for people with rheumatoid arthritis include disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), both synthetic and biologics; nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); glucocorticoids; analgesics; and, rarely, cytostatics (drugs that inhibit cell growth).

In recent years several Cochrane Reviews have assessed various pharmacological interventions for people with rheumatoid arthritis including methotrexate (Lopez‐Olivo 2014), rituximab (a biologic agent) (Lopez‐Olivo 2015), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐alpha inhibitor certolizumab pegol (CDP870) (Ruiz Garcia 2014), etanercept (a soluble TNF‐alpha receptor disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug) (Lethaby 2013), opioids (Whittle 2011), muscle relaxants (Richards 2012a) and neuromodulators (Richards 2012b). Non‐drug interventions have also been assessed. Cramp 2013 analysed interventions for self‐reported fatigue in adults with rheumatoid arthritis; Hurkmans 2009 investigated dynamic exercise programs; and Verhagen 2015 assessed balneotherapy. Reported benefits and harms vary for both drug and non‐drug interventions.

NSAIDs are commonly prescribed for people with rheumatoid arthritis. The analgesic effect of NSAIDs is traditionally explained primarily by inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme. COX has two isoforms (COX‐1 and COX‐2). Although COX‐1 is part of normal cells, COX‐2 is usually specific to inflamed tissue, so has a role in mediating pain, inflammation and fever (Conaghan 2012).

Traditional NSAIDs (tNSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, diclofenac and naproxen, are non‐selective and inhibit both COX‐1 and COX‐2. Celecoxib is a COX‐2 inhibitor.

How the intervention might work

NSAIDs are a heterogeneous group of drugs with common pain‐relieving, antipyretic, and anti‐inflammatory actions, and are thought to relieve pain by inhibiting cyclooxygenases and consequently the production of prostaglandins (Hawkey 1999). Considering the influence of COX on normal metabolism and inflammatory response, it became important to find ways to regulate inflammation, but without interrupting the normal body processes. Selective COX‐2 inhibitors were developed to avoid gastro‐intestinal toxicity of nonselective NSAIDs. This led to the development of the group of NSAIDs known as the coxibs, including the drugs celecoxib, etoricoxib, lumiracoxib, parecoxib, rofecoxib and valdecoxib. Celecoxib is a highly selective reversible COX‐2 inhibitor, which prevents transformation of arachidonic acid to prostaglandin precursors, important mediators of pain and inflammation. Thus, inhibiting production of these prostaglandins through COX‐2 inhibition alleviates pain and swelling (Süleyman 2007). Celecoxib is currently marketed in most countries in doses that were evaluated in this review (200 mg and 400 mg daily) (FDA 2016; TGA 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

Use of NSAIDs is associated with varying degrees of cardiovascular and gastro‐intestinal risk, such as upper gastro‐intestinal bleeding, and these risks should be considered in treatment decisions (Conaghan 2012; Trelle 2011). However, proton pump inhibitors can reduce risk of upper gastro‐intestinal bleeding (Lanas 2014). Use of selective COX‐2 inhibitors is associated with risk of serious vascular events, due to a twofold increased risk of myocardial infarction (Kearney 2006). A 2013 meta‐analysis conducted by the Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’ (CNT) Collaboration analyzed vascular and upper gastro‐intestinal effects of NSAIDs, based on individual participant data from randomized controlled trials. It was shown that celecoxib significantly increased major cardiovascular event risk, but with less proportional excess risk of major vascular events associated with lower celecoxib doses in placebo‐controlled trials (CNT 2013).

In an era when many effective treatments are available, the need for continuous NSAID use is decreasing and requires justification. Clinical studies, rather than laboratory assay studies, are the best way to determine if people benefit from the use of more selective NSAIDs (Chou 2006). We therefore examined the benefits and harms of celecoxib for people with rheumatoid arthritis by analyzing results of randomized controlled trials.

This Review was conducted according to guidelines recommended by the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group Editorial Board (Ghogomu 2014).

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of celecoxib in people with rheumatoid arthritis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reported in full‐text reports with no language restrictions. Studies with fewer than 50 participants in each arm or involving treatment of less than four weeks' duration were excluded.

Types of participants

We included studies involving participants of any age and either sex with clinical confirmation of rheumatoid arthritis or who met the rheumatoid arthritis criteria of the 1987 American College of Rheumatology Classification (ACR) (Arnett 1988), or the 2010‐2009 ACR criteria for classification of rheumatoid arthritis (Aletaha 2010), whichever was used by study authors. People with juvenile arthritis were excluded.

Studies involving participants with conditions other than rheumatoid arthritis (i.e. mixed populations) were included only if outcomes for participants with rheumatoid arthritis were presented as a separate data subset or if separate data were available from the study authors.

Types of interventions

We included trials comparing oral celecoxib (200 mg and 400 mg daily) with no intervention, placebo or another traditional nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (tNSAID).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

ACR20/30 (Felson 1995). ACR20/30 was defined as a 20% and 30% improvement, respectively, in the number of tender and swollen joints and a corresponding improvement in at least three of the following items: observer evaluation of overall disease activity, the individual's evaluation of overall disease activity, the individual's evaluation of pain, a score of physical disability, or improvements in blood acute‐phase responses (Felson 1998).

Pain.

Self‐reported function as measured on the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) Disability Index (Gardiner 1993) or modified HAQ. HAQ scores range from 0 to 3, with 3 indicating a worse health state; therefore negative change indicates health improvement.

Cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke).

Incidence of gastroduodenal ulcer ≥ 3 mm.

Short‐term serious adverse events from trials.

Long‐term adverse events or toxicity from observational studies.

Secondary outcomes

Total withdrawals (discontinuation rates).

Withdrawals due to adverse events.

Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE and Embase. We also searched trials registers (www.ClinicalTrials.gov and www.who.int/ictrp/en/). We searched databases from inception dates to May 18, 2017. We imposed no restrictions on language of publication. See Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE, Embase and The Cochrane Library search strategy. The MEDLINE search strategy combined the subject search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying reports of randomized controlled trials (as published in Box 6.4.c in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0, updated March 2011) and was modified for other databases (Higgins 2011).

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists and citations of all included primary studies and relevant review articles for additional references. We searched for errata or retractions from included studies published in full‐text on PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

For assessments of adverse effects, we searched the websites of regulatory agencies: USA Food and Drug Administration‐MedWatch (http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/default.htm); European Medicines Evaluation Agency (http://www.emea.europa.eu); Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin (http://www.tga.gov.au/adr/aadrb.htm); and UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) pharmacovigilance and drug safety updates (http://www.mhra.gov.uk).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three review authors (MF, AJK, MR) independently screened titles and abstracts for inclusion of all the potential studies we had identified as a result of the search and coded them as 'retrieve' (eligible or potentially eligible/unclear) or 'do not retrieve'. We retrieved the full‐text study reports/publications and two review authors (MF, AJK) independently screened the full‐text and identified studies for inclusion, and identified and recorded reasons for exclusion of ineligible studies. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third author (LP). We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the Review. All studies were published in English so translation was unnecessary. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram and Characteristics of excluded studies table. Study authors were contacted for clarifications and to obtain additional data whenever necessary.

Data extraction and management

We used a data collection form for study characteristics and outcome data which had been piloted on one study in the Review. Two review authors (MF, AJK) extracted study characteristics from included studies. We extracted the following study characteristics:

Methods: study design, total duration of study, number of study centers and location, study setting, withdrawals, and date of study.

Participants: number, mean age, age range, sex, disease duration, severity of condition, diagnostic criteria, important rheumatoid arthritis‐specific baseline data, inclusion criteria, and exclusion criteria.

Interventions: intervention, comparison, concomitant medications, and excluded medications.

Outcomes: major and minor outcomes specified and collected, and time points reported.

Characteristics of the design of the trial as outlined in the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section.

Notes: study funding sources, notable declarations of interest of study authors, co‐interventions that participants were permitted to take.

Two review authors (MF, AJK) independently extracted outcome data from included studies. Numbers of events and participants per treatment group for dichotomous outcomes, means, standard deviations and number of participants per treatment group for continuous outcomes, were extracted. We resolved disagreements by consensus or by involving a third author (LP). One review author (MF) transferred data into the Review Manager (RevMan) file (Review Manager 2014). Two authors (AJK, LP) checked whether all data were entered correctly. We double‐checked that data were entered correctly by comparing data presented in the systematic review with the study reports. Whenever necessary, we attempted to obtain or clarify data from relevant individuals or organizations.

For numeric data present only in figures or graphs, authors of the original report were contacted and data requested. When necessary, numeric data were extracted from figures in the reports using Plot Digitizer software (Vucic 2015). Whenever possible, we used results from intention‐to‐treat analyses.

If a study had reported multiple time‐point measurements we extracted data from the end of the study for analysis.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (MF, AJK) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by involving another author (LP). We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains:

random sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of participants and personnel;

blinding of outcome assessment;

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting; and

other biases (relating to particular aspects of study design and conflicts of interest).

We graded each potential source of bias as high, low or unclear and provided a quote from the study report together with a justification for our judgment in the 'Risk of bias' table. We summarized the risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed. We considered blinding separately for different key outcomes where necessary (e.g. for unblinded outcome assessment, risk of bias for all‐cause mortality may be different than for a patient‐reported pain scale). We also considered the impact of missing data for key outcomes.

Attrition in either study arm above 30% and imbalance in attrition between study arms over 10% was considered high risk of bias, regardless of the data imputation method. Attrition between 10% and 30% in either arm, and imbalance between groups between 5% and 10% was considered unclear risk of bias.

Where information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with an author, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table.

When considering treatment effects, we took into account the risk of bias for the studies that had contributed to that outcome.

We presented figures generated by the 'Risk of bias' tool to provide summary assessments of the risk of bias.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted the review a priori according to the protocol published in the Cochrane Library (Fidahic 2016).

Measures of treatment effect

We analyzed dichotomous data as risk ratios (RR) or Peto odds ratio (Peto OR) when the outcome was a rare event (approximately less than 10%), and used 95% confidence intervals (CI). Continuous data were analyzed as mean difference and 95% CI. We entered data presented as a scale with a consistent direction of effect across studies.

We provided the absolute per cent difference, the relative per cent change from baseline, and the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) in Effects of interventions and the 'Comments' columns of 'Summary of findings' tables. The NNTB was provided only when the outcome showed a statistically significant difference.

For dichotomous outcomes, such as serious adverse events, the NNTB was calculated from the control group event rate and the risk ratio using the Visual Rx NNT calculator (Cates 2008). The NNTB for continuous measures was calculated using the Wells calculator (http://musculoskeletal.cochrane.org/).

For dichotomous outcomes, the absolute risk difference was calculated using the Risk Difference statistic in RevMan and the result expressed as a percentage. For continuous outcomes, the absolute benefit was calculated as the improvement in the intervention group minus the improvement in the control group, in the original units.

The relative per cent change for dichotomous data was calculated as the RR and expressed as a percentage. For continuous outcomes, the relative difference in the change from baseline was calculated as the absolute benefit divided by the baseline mean of the control group.

Unit of analysis issues

Where multiple arms were reported in a single trial, we included only the relevant arms. For studies containing more than two relevant intervention groups, to make multiple pair‐wise comparisons between all possible pairs of intervention groups possible, we included the same group of participants more than once in the meta‐analysis, but divided the number of participants proportionally, following the procedure recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If the meta‐analyses resulted in statistically significant overall estimates, we transformed these results back into measures which are clinically useful in daily practice, such as the NNTB and the absolute or relative improvement on the original units, to express the final results of the review (Akl 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We did not encounter any missing data for analysis of outcomes. To obtain missing information for risk of bias analysis we contacted study authors via e‐mail.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Clinical and methodological diversity were assessed in terms of participants, interventions, outcomes and study characteristics for the included studies to determine if meta‐analysis was appropriate. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by visual inspection of the forest plot to assess for obvious differences in results among studies, and using the I² and Chi² statistical tests.

As recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011), the interpretation of an I² value of 0% to 40% might 'not be important'; 30% to 60% may represent 'moderate' heterogeneity; 50% to 90% may represent 'substantial' heterogeneity; and 75% to 100% represents 'considerable' heterogeneity. As noted in the Handbook, we kept in mind that the importance of I² depends on magnitude and direction of effects and strength of evidence for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to create a funnel plot to explore possible small study biases. However, there were too few included studies to analyze potential publication bias.

We checked trial protocols against published reports to assess outcome reporting bias. For studies published after 1 July 2005, we screened the Clinical Trial Register at the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform of the World Health Organization (apps.who.int/trialsearch) for a priori trial protocols. We evaluated if selective reporting of outcomes was present.

Data synthesis

We undertook meta‐analyses only where this was meaningful, that is, if the treatments, participants and the underlying clinical question were sufficiently similar for pooling to make sense. We planned to categorize studies as short‐term and long‐term, where long‐term studies were defined as those with duration of more than six months for analyses. However, we did not find any studies longer than six months.

We used a random‐effects model and performed sensitivity analyses using the fixed‐effect model.

Summary of findings table

We created 'Summary of findings' tables that included the following outcomes:

ACR20/30 improvement;

pain;

Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) change from baseline;

cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke);

incidence of gastroduodenal ulcer ≥ 3 mm;

short‐term serious adverse events from trials; and

discontinuation rates.

'Summary of findings' tables present comparisons for:

Two authors (LP, MF) independently assessed evidence quality. We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the quality of a body of evidence as it related to the studies which contributed data to the meta‐analyses for the pre‐specified outcomes. We used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5, 8.7 and Chapter 11 and Chapter 13 section 13.5 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT 2014; Higgins 2011; Schünemann 2011a). We justified all decisions to downgrade the quality of studies in footnotes and we made comments to aid readers' understanding of the review where necessary.

We provided the absolute per cent difference, the relative per cent change from baseline, NNTB and NNTH (NNTB and NNTH were provided only when the outcome showed a statistically significant difference) in the 'Comments' columns of 'Summary of findings' tables.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses:

participants’ age (< 65 years versus ≥ 65 years);

participants’ sex;

duration of rheumatoid arthritis (< 3 years versus ≥ 3 years);

drug dose (200 mg to 400 mg); and

methodological quality (studies with low risk of bias on all domains versus all the other studies).

However, we were able to conduct a subgroup analysis only for drug dose.

We used the formal test for subgroup interactions in Review Manager 2014, and applied caution to interpret subgroup analyses as advised in section 9.6 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011). The magnitude of the effects was compared between subgroups by means of assessing the overlap of the confidence intervals of the summary estimated. No overlap of the confidence intervals indicated statistical significance.

Sensitivity analysis

Primary meta‐analysis was restricted to studies assessed at low risk of bias. Because no studies were assessed at low risk of bias on all seven domains, we considered a study to be at overall low risk of bias when three domains (randomization sequence, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel) were assessed as low risk of bias. All studies were included in meta‐analyses. Sensitivity analysis was performed to assess how the results of the meta‐analysis might be affected if studies at unclear and high risk of bias were included. If assessment of heterogeneity found one or more outlying studies with results that conflicted with the rest of the studies, sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the influence on the results of the meta‐analysis. Sensitivity analysis was also performed for potential differences between random‐effects and fixed‐effect meta‐analyses.

Interpreting results and reaching conclusions

We followed the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Chapter 12 for interpreting results (Schünemann 2011b); and were aware of distinguishing a lack of evidence of effect from a lack of effect. We based our conclusions only on findings from the quantitative synthesis of included studies for this review. The Implications for research section of this review provides suggested priorities for future research and we outlined what the remaining uncertainties were in the area.

Results

Description of studies

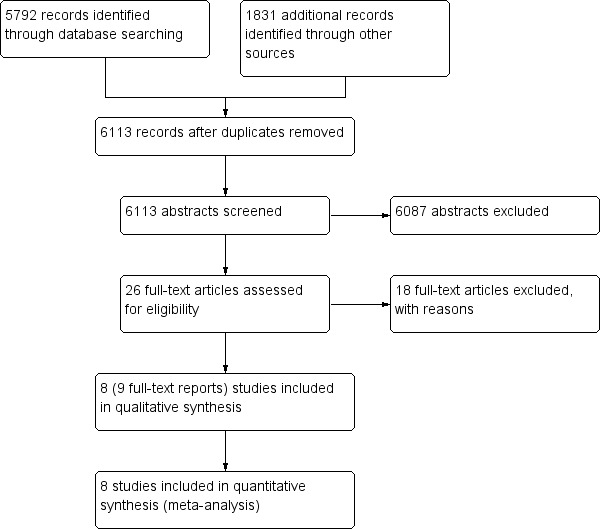

See Figure 1, Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

1.

Study flow diagram

Results of the search

We identified 5792 records from searching databases and 1831 from searching other sources. Following de‐duplication, we screened 6113 records by title and abstract. We obtained 26 full‐text papers that were potentially eligible for inclusion Of these, eight studies (9 reports) were included (Figure 1). We did not find any eligible studies that were only published as conference abstracts or were available only as unpublished data.

Included studies

We included eight double‐blinded, randomized, parallel‐group trials that were published in English language between 1998 and 2014 (Choi 2014; Emery 1999; Goldstein 2001; Jajic 2005; Kivitz 2004; Shi 2004; Simon 1998; Simon 1999). Study duration ranged from 4 weeks to 24 weeks. Only one study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Choi 2014).

Participants were randomly assigned to treatment with different doses of celecoxib (range 80 mg/day up to 800 mg/day) (N = 1786). In this review we included only participants who received celecoxib 200 mg (N = 295) and celecoxib 400 mg (N = 1322), which is in total 1617 participants who received celecoxib doses relevant for this review. Additionally, we included 2202 participants that were randomly assigned to one of the comparator groups: tNSAIDs (N = 1886) or placebo (N = 316).

Although ACR20/30 was defined as a primary outcome measure, included studies reported only ACR20.

Population

The eight included studies included a total of 3988 participants whose mean age was 54 years; 73% were women. Participants had rheumatoid arthritis for an average duration of 9.2 years; two studies did not describe duration of rheumatoid arthritis in study participants (Jajic 2005; Kivitz 2004).

Settings

All studies were conducted in ambulatory outpatient setting. Three studies were conducted in one country only, namely China (Shi 2004), Korea (Choi 2014) or USA (Goldstein 2001). One study was conducted in multiple sites in Europe (Jajic 2005), one in USA and Canada (Simon 1999), while two studies were conducted in multiple continents (Emery 1999; Kivitz 2004). For one trial study location was not described (Simon 1998). See Characteristics of included studies.

Interventions and comparators

Two studies compared celecoxib with placebo (Simon 1998; Simon 1999); seven studies compared celecoxib with another marketed tNSAID drug (naproxen amtolmetin guacyl (AMG), diclofenac, ibuprofen, lumiracoxib, meloxicam, nabumetone and pelubiprofen) (Choi 2014; Emery 1999; Goldstein 2001; Jajic 2005; Kivitz 2004; Shi 2004; Simon 1999). However, since concern over hepatotoxicity has led to market withdrawal or non approval of lumiracoxib in most markets (Singer 2010), comparison of celecoxib with lumiracoxib was not included in this review.

Study funding

Four studies were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies producing study drugs (Goldstein 2001; Kivitz 2004; Simon 1998; Simon 1999). One study reported that a pharmaceutical company provided investigational medication for the study (Choi 2014). One study reported part funding support by a state authority (Shi 2004). Two studies did not declare sources of funding or declarations of declaration of interest (Emery 1999; Jajic 2005). Five studies that provided declarations included one or more authors who were employed by the sponsor (Emery 1999; Goldstein 2001; Kivitz 2004; Simon 1998; Simon 1999).

Study registration

One study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (Choi 2014). Although it is indicated that the trial was completed in October 2011, the results were not posted in ClinicalTrials.gov (last checked on May 26, 2017). The other included studies did not provide information about study registration, but they were published in 2005 or before, when prospective registration of trials was not mandatory.

Excluded studies

Following assessment we excluded 18 studies. Of these, 11 studies did not report separate data for people with rheumatoid arthritis (Chan 2002; Chan 2004; Chan 2007; Chan 2010; Cheung 2010; Goldstein 2002; Hegazy 2011; Kellner 2012; Kellner 2013; Nissen 2016; Silverstein 2000). One study was published only as a conference abstract, from which it appears that participants with different types of arthritis were included, but results were not shown separately for rheumatoid arthritis in the abstract (Chan 2015). One study was not an RCT (Cheatum 1999). Five RCTs were excluded because they compared celecoxib with comparators that were irrelevant to this systematic review (Liu 2015; Song 2007), celecoxib was not analysed (Laine 2002; Laine 2007) or there were fewer than 50 participants in each arm (Zayat 2011). See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

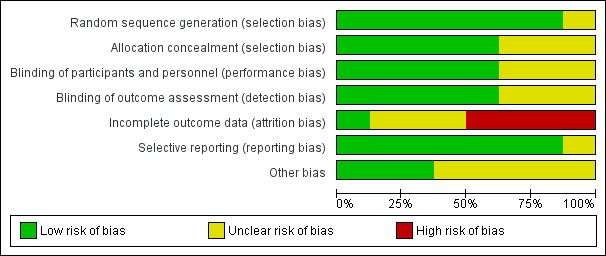

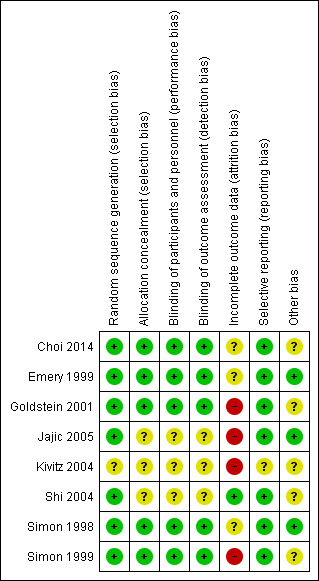

Risk of bias varied across studies (Figure 2; Figure 3). High risk of attrition bias was assessed for seven studies. Most of the studies were judged as having low risk of selection bias and reporting bias because those domains were adequately described. Among the other risk of bias domains the judgements varied more.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Random sequence generation was adequately described in seven studies (low risk of bias) (Choi 2014; Emery 1999; Goldstein 2001; Jajic 2005; Shi 2004; Simon 1998; Simon 1999). Five studies used software‐generated randomization methods (Choi 2014; Goldstein 2001; Jajic 2005; Shi 2004; Simon 1999); two used centralized random numbers methods (Emery 1999; Simon 1998). One study was assessed at unclear risk of selection bias because the method of random sequence generation was not described (Kivitz 2004).

Blinding

Three studies did not describe blinding and were assessed at unclear risk of performance and detection bias (Jajic 2005; Kivitz 2004; Shi 2004). Five studies were included adequate descriptions of blinding and were assessed at low risk of performance and detection bias (Choi 2014; Emery 1999; Goldstein 2001; Simon 1998; Simon 1999).

Incomplete outcome data

Seven studies were assessed at high or unclear risk of attrition bias because of significant numbers of participants who were lost to follow‐up or because of imbalance in attrition between study arms, or both (Choi 2014; Emery 1999; Goldstein 2001; Jajic 2005; Kivitz 2004; Simon 1998; Simon 1999). One study reported low rates of attrition and rates were similar in all study arms and was assessed at low risk of attrition bias (Shi 2004).

Selective reporting

Kivitz 2004 was the only study assessed at unclear risk of reporting bias; not all outcomes specified in methods were described in results, except for a note that there was no difference in efficacy. Seven studies were assessed at low risk of reporting bias (Choi 2014; Emery 1999; Goldstein 2001; Jajic 2005; Shi 2004; Simon 1998; Simon 1999).

Other potential sources of bias

Concomitant therapy and rescue medication were identified as potential sources of bias in five studies (Choi 2014; Goldstein 2001; Kivitz 2004; Shi 2004; Simon 1999). Acetaminophen was used as a rescue medication in four studies (Choi 2014; Goldstein 2001; Kivitz 2004; Simon 1999). The rescue treatment protocols for acetaminophen included an acetaminophen extended‐release 650 mg tablet (Choi 2014), up to 2 g daily (Kivitz 2004; Simon 1999); one study did not describe the rescue medication protocol (Goldstein 2001). Aspirin was used as a rescue medication at a stable dose of no more than 325 mg daily in Simon 1999. Methotrexate and folic acid were used as concomitant therapy as a dose of 10 mg/week of methotrexate and 5 mg daily of folic acid tablet in Shi 2004. Oral corticosteroids were permitted in one study “only if there was no change in the dosing regimen during the study”, but the dose was not specified (Goldstein 2001). None of the studies reported how many co‐interventions participants in each study arm took and how this may have affected the results. No other sources of bias were identified in three studies (Emery 1999; Jajic 2005; Simon 1998).

Effects of interventions

No studies reported ACR30 data. Although we planned to assess self‐reported function measured on the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) Disability Index, some studies reported according to the modified HAQ (MHAQ); these results were reported. No studies reported long‐term adverse events.

Comparison 1. Celecoxib versus placebo

Simon 1998 and Simon 1999 (N = 873) compared celecoxib with placebo. Simon 1998 compared 400 mg celecoxib daily with placebo and 4 weeks follow up; Simon 1999 compared two doses of celecoxib (200 mg and 400 mg daily) with placebo and 12 weeks follow up.

Primary outcomes

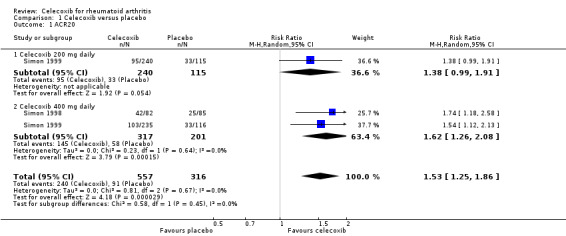

ACR20 improvement

More participants who received either 200 mg or 400 mg celecoxib daily had statistically significant and clinically important rates of meeting the ACR20 improvement criteria (RR 1.53, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.86, P < 0.001; 2 studies; N = 873; Analysis 1.1). This corresponds with a 15% absolute improvement (95% CI 7% to 25%) or 53% relative improvement (95% CI 25% to 86%). The number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) was seven (95% CI 5 to 13). No differences were found in subgroup analyses of celecoxib 200 mg (Analysis 1.1) and 400 mg (Analysis 1.1.2) daily compared with placebo (P = 0.45). Evidence quality was moderate (downgraded due to risk of bias). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.81, df = 2, P = 0.67, I² = 0%).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Celecoxib versus placebo, Outcome 1 ACR20.

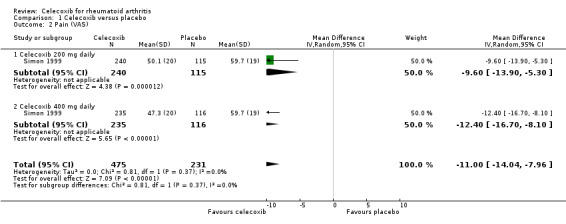

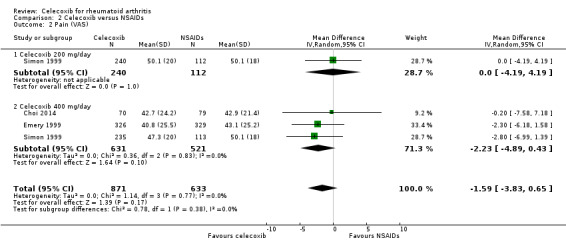

Pain

Celecoxib 200 mg and 400 mg daily significantly reduced pain compared to placebo (MD ‐11.00, 95% CI ‐14.04 to ‐7.96, P < 0.001; 1 study, N = 706; Analysis 1.2). This corresponds with an 11% absolute improvement (95% CI 8% to 14%) and 18% relative improvement (95% CI 13% to 23%), NNTB = 4 (95% CI 3 to 6), (MD 11, 95% CI 14.04 to 7.96). Subgroup analyses comparing celecoxib 200 mg (Analysis 1.2) and 400 mg (Analysis 1.2) daily with placebo had the same direction as the overall effect; there was no evidence of a difference between subgroups (P = 0.37). Evidence quality was moderate (downgraded due to risk of bias). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.81, df = 1, P = 0.37, I² = 0%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Celecoxib versus placebo, Outcome 2 Pain (VAS).

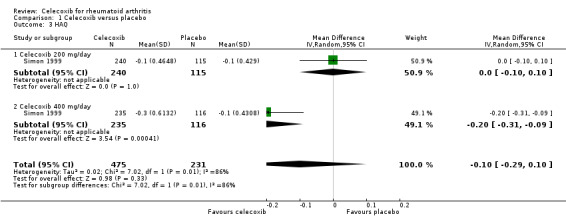

Self‐reported physical function (Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ))

We found no evidence of a difference between celecoxib and placebo for self‐reported function measured on the HAQ (95% CI crossed the line of no effect) (MD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.29 to 0.10, P = 0.33; 1 study, N = 706; Analysis 1.3). Subgroup analyses found no difference between celecoxib 200 mg (Analysis 1.3) daily and placebo, but celecoxib 400 mg daily was superior to placebo (Analysis 1.3). There was statistically significant heterogeneity (Chi² = 7.02, df = 1, P = 0.008, I² = 86%). Evidence quality was low (downgraded due to risk of bias and inconsistency).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Celecoxib versus placebo, Outcome 3 HAQ.

Cardiovascular events

No studies reported this outcome.

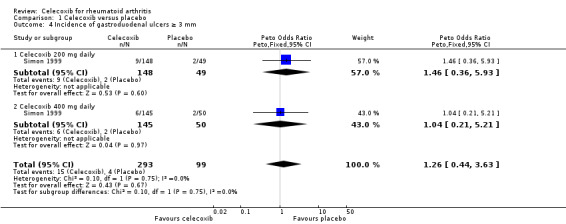

Incidence of gastroduodenal ulcer ≥ 3 mm

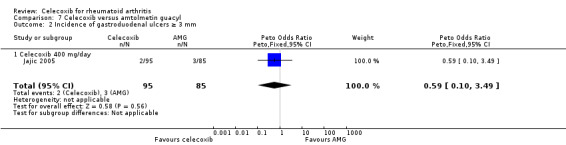

Results were inconclusive about differences in incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers between celecoxib 200 mg and 400 mg daily and placebo. In this analysis 15/293 (51 per 1000; range 17 to 142) participants in the celecoxib group developed ulcers compared with 4/99 (40 per 1000) in the placebo group (Peto OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.44 to 3.63, P = 0.67; 1 study, N = 392; Analysis 1.4). Subgroup analyses comparing celecoxib 200 mg (Analysis 1.4) and 400 mg (Analysis 1.4) daily with placebo showed no differences. Evidence quality was low (downgraded due to risk of bias and imprecision). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.11, df = 1, P = 0.74, I² = 0%).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Celecoxib versus placebo, Outcome 4 Incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm.

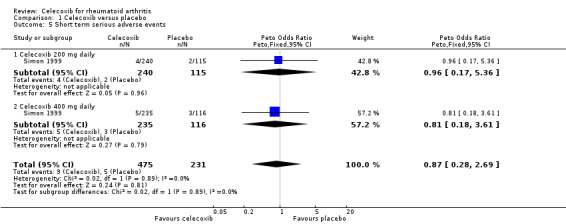

Short‐term serious adverse events

Results were inconclusive for short‐term serious adverse events like headache, dyspepsia, diarrhea and abdominal pain (Simon 1999). There were 9/475 (19 per 1000; range 6 to 55) participants in the celecoxib group who developed short‐term serious adverse events compared with 5/231 (22 per 1000) in the placebo group (Peto OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.28 to 2.69, P = 0.81; 1 study, N = 706; Analysis 1.5). Subgroup analyses of celecoxib 200 mg (Analysis 1.5) and 400 mg (Analysis 1.5) daily versus placebo indicated no differences. Evidence quality was low (downgraded due to risk of bias and imprecision). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.02, df = 1, P = 0.89, I² = 0%).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Celecoxib versus placebo, Outcome 5 Short term serious adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

Total withdrawals (discontinuation rates)

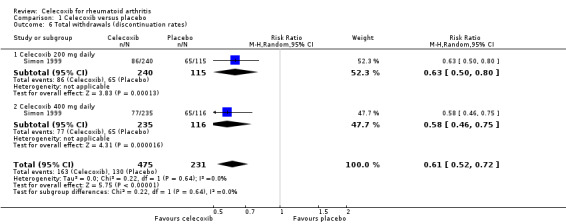

Simon 1999 showed a statistically significant higher rate of total withdrawals from the placebo group compared to celecoxib 200 mg and 400 mg daily (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.72, P < 0.001; N = 706; Analysis 1.6). There were 163/475 (343 per 1000; range 293 to 405) withdrawals from the celecoxib group compared with 130/231 (563 per 1000) in the placebo group, corresponding to 22% absolute change (95% CI 16% to 27%) and 39% relative change (28% to 48%), NNTH = 5 (95% CI 4 to 7). Subgroup analyses for celecoxib 200 mg daily and 400 mg daily versus placebo had the same direction as the overall effect; there was no evidence of difference between subgroups (P = 0.64). Evidence quality was low (downgraded due to risk of bias and imprecision). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.22, df = 1, P = 0.64, I² = 0%).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Celecoxib versus placebo, Outcome 6 Total withdrawals (discontinuation rates).

Withdrawals due to adverse events

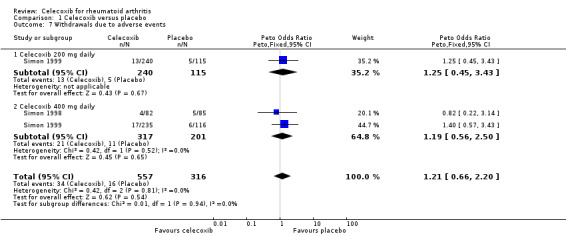

Pooled analysis results were inconclusive regarding difference between celecoxib and placebo in numbers of withdrawals due to adverse events (Peto OR 1.21, 95% CI 0.66 to 2.20, P = 0.54; 2 studies, N = 873; Analysis 1.7). Subgroup analyses for celecoxib 200 mg daily and 400 mg daily versus placebo had the same direction as the overall effect; there was no evidence of difference between subgroups (P = 0.94). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.44, df = 2, P = 0.80, I² = 0%).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Celecoxib versus placebo, Outcome 7 Withdrawals due to adverse events.

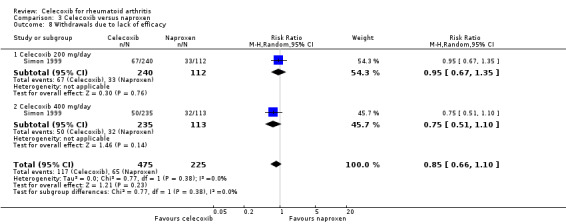

Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy

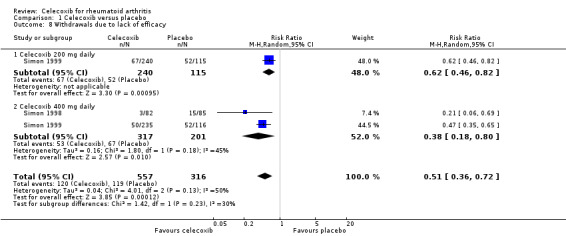

Pooled analysis showed statistically significant more withdrawals due to lack of efficacy in the placebo group compared to celecoxib (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.72, P < 0.001; 2 studies, N = 873; Analysis 1.8). Subgroup analyses for celecoxib 200 mg daily and 400 mg daily versus placebo had the same direction as the overall effect; there was no evidence of difference between subgroups (P = 0.23). Heterogeneity was moderate (Chi² = 4.01, df = 2, P = 0.13, I² = 50%).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Celecoxib versus placebo, Outcome 8 Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy.

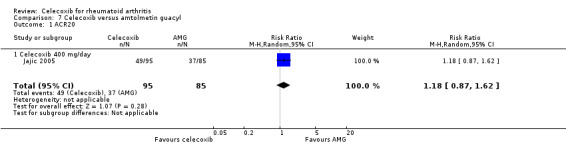

Comparison 2. Celecoxib versus tNSAIDs

Primary outcomes

ACR20

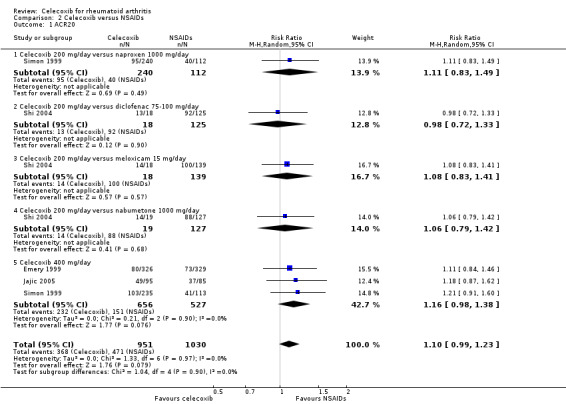

Shi 2004 and Simon 1999 compared celecoxib 200 mg daily with tNSAIDs; Emery 1999, Jajic 2005 and Simon 1999 compared celecoxib 400 mg daily with tNSAIDs. Follow‐up periods ranged from 12 weeks to 6 months. Pooled analysis showed no statistically significant difference between celecoxib and tNSAIDs in ACR20 improvement criteria (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.23, P = 0.08; 4 studies, N = 1981; Analysis 2.1). More participants receiving tNSAIDs (368/951 or 503 per 1000; range 453 to 562) had clinical improvement compared to those taking placebo (471/1030 or 457 per 1000), accounting for 4% absolute improvement (95% CI 0% less to 8% more) or 10% relative improvement (1% less to 23% more). This improvement may not be clinically significant; evidence quality was assessed as moderate due to risk of bias. There was no evidence of differences among subgroups of drugs included in this analysis (P = 0.90). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 1.33, df = 6, P = 0.97, I² = 0%).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Celecoxib versus NSAIDs, Outcome 1 ACR20.

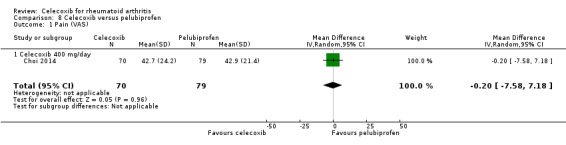

Pain

Simon 1999 compared celecoxib 200 mg daily versus tNSAIDs, and three studies compared celecoxib 400 mg daily and tNSAIDs (Choi 2014; Emery 1999; Simon 1999). Follow‐up ranged from 6 weeks to 24 weeks. Pooled analysis showed no statistically significant difference between celecoxib and tNSAIDs in reducing pain (MD ‐1.59, 95% CI ‐3.83 to 0.65, P = 0.17; 3 studies, N = 1504; Analysis 2.2). Pain intensity was slightly lower with celecoxib compared to tNSAIDs; 2% absolute improvement (95% CI 3.83% better to 0.65% worse), 3% relative improvement (95% CI 8% better to 1% worse); MD= ‐1.59 (95% CI ‐3.83 to 0.65). This improvement may not be clinically significant (moderate quality of evidence due to risk of bias). Subgroup analyses for celecoxib 200 mg daily and 400 mg daily versus tNSAIDs had the same direction as the overall effect; there was no evidence of difference among subgroups (P = 0.38). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 1.14, df = 3, P = 0.77, I² = 0%).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Celecoxib versus NSAIDs, Outcome 2 Pain (VAS).

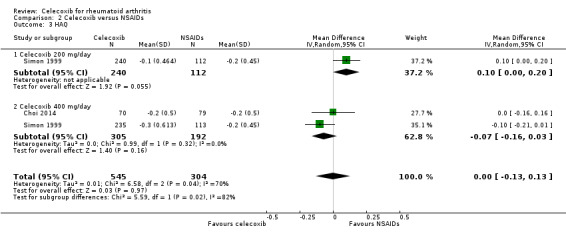

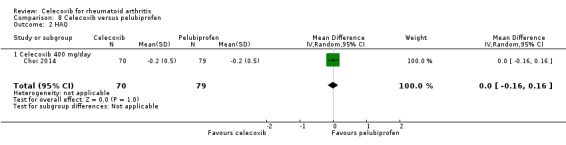

Self‐reported physical function (Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) and Modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (MHAQ)

Simon 1999 compared celecoxib 200 mg daily with tNSAIDs; Choi 2014 and Simon 1999 compared celecoxib 400 mg daily with tNSAIDs. Follow‐up periods were 6 weeks and 12 weeks. Pooled analysis showed no evidence of difference between celecoxib and tNSAIDs in self‐reported physical function assessed using the HAQ (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.13, P = 0.97; 2 studies, N = 849; Analysis 2.3); 0% absolute change (95% CI 13% better to 13% worse), 0% relative change (95% CI 65% better to 65% worse). There was statistically significant heterogeneity (Chi² = 6.58, df = 2, P = 0.04; I² = 70%). Evidence quality was assessed as low (downgraded due to risk of bias and inconsistency).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Celecoxib versus NSAIDs, Outcome 3 HAQ.

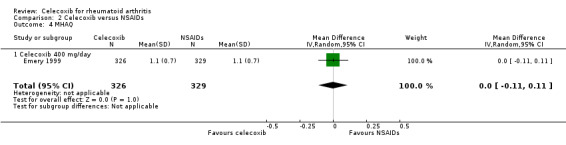

Emery 1999 compared celecoxib 400 mg daily versus tNSAIDs with 24 weeks follow‐up. There was no evidence of difference between celecoxib and tNSAIDs in self‐reported physical using the modified form of the HAQ questionnaire (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.11 to 0.11, P = 1.00; 1 study, N = 655; Analysis 2.4). Heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Celecoxib versus NSAIDs, Outcome 4 MHAQ.

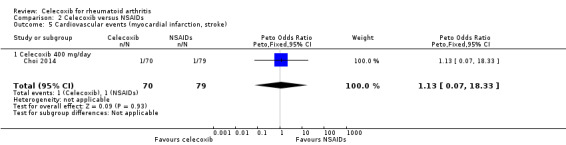

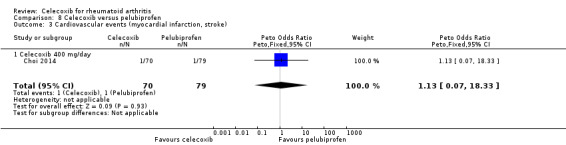

Cardiovascular events

Choi 2014 compared celecoxib 400 mg daily versus tNSAIDs. There was no evidence of difference between celecoxib and tNSAIDs in the incidence of cardiovascular events (OR 1.13, 95% CI 0.07 to 18.42, P = 0.93; 1 study, N = 149; Analysis 2.5). Only one cardiovascular event was reported in each group, 1/70 (or 14 per 1000; range 1 to 191) in the celecoxib group and 1/79 (13 per 1000) in the tNSAID group; 0% absolute change (95% CI 4% less to 4% more), 13% relative change (95% CI 93% less to 1733% more); Peto OR 1.13 (95% CI 0.07 to 18.33). These data did not enable definitive conclusions to be made because this study was short duration and there was significant risk of type 2 error due to small numbers. Furthermore, this result is uncertain because it was based on low quality evidence (downgraded due to risk of bias and imprecision). Heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Celecoxib versus NSAIDs, Outcome 5 Cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke).

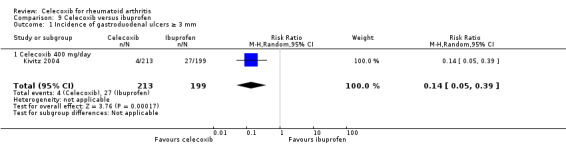

Incidence of gastroduodenal ulcer ≥ 3 mm

Simon 1999 compared celecoxib 200 mg daily versus tNSAIDs; Emery 1999, Goldstein 2001, Jajic 2005, Kivitz 2004 and Simon 1999 compared celecoxib 400 mg daily versus tNSAIDs. Follow‐up ranged from 12 weeks to 6 months. Pooled analysis showed that the incidence rate of gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm was statistically significantly lower in the celecoxib group compared to tNSAIDs (RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.32, P < 0.001; 5 studies, N = 1568; Analysis 2.6). Subgroup analyses for celecoxib 200 mg daily and 400 mg daily versus tNSAIDs had the same direction as the overall effect; there was no evidence of difference between subgroups (P = 0.94). There were 34/870 (343 per 1000; range 232 to 50) ulcers reported in the celecoxib group compared to 116/698 (or 155 per 1000) in participants taking tNSAIDs, corresponding to 12% absolute change (95% CI 11% to 13%), 22% relative change (95% CI 15% to 32%); NNTH 9 (95% CI 8 to 10), RR 0.22 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.32). This result is based on moderate quality evidence (downgraded due to risk of bias). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 3.12, df = 5, P = 0.68, I² = 0%).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Celecoxib versus NSAIDs, Outcome 6 Incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm.

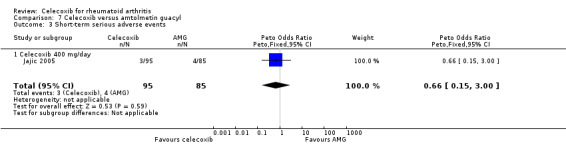

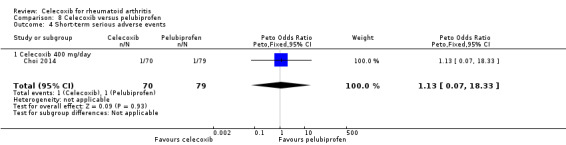

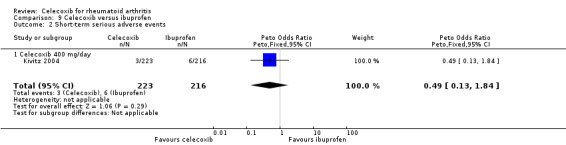

Short‐term serious adverse events

Shi 2004 and Simon 1999 compared celecoxib 200 mg daily versus tNSAIDs; Choi 2014, Jajic 2005, Kivitz 2004 and Simon 1999 compared celecoxib 400 mg daily versus tNSAIDs. Follow‐up ranged from six weeks to six months. Pooled analysis showed that there was no evidence of difference between celecoxib and tNSAIDs in the rate of short‐term serious adverse events (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.44, P = 0.42; 5 studies, N = 2154; Analysis 2.7). There was no evidence of difference in effect among subgroups (P = 0.81). There were 17/918 (26 per 1000; range 15 to 48) serious adverse events in the celecoxib group compared to 42/1236 (or 34 per 1000) in the tNSAID group, corresponding to 1% absolute change (95% CI 2% less to 1% more), 29% relative change (95% CI 61% less to 28% more); Peto OR 0.71 (0.39 to 1.28). This result is uncertain because it was based on low quality evidence (downgraded due to risk of bias and imprecision). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 1.68, df = 7, P = 0.98, I² = 0%).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Celecoxib versus NSAIDs, Outcome 7 Short‐term serious adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

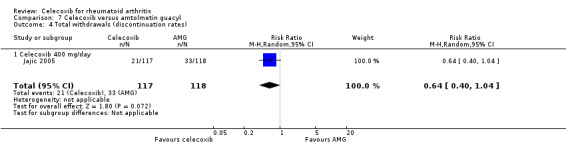

Total withdrawals (discontinuation rates)

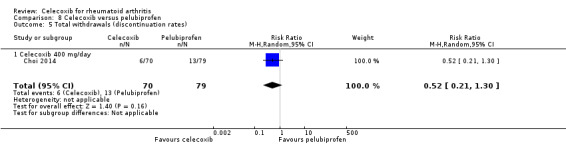

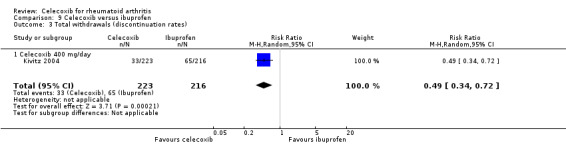

Shi 2004 and Simon 1999 compared celecoxib 200 mg daily versus tNSAIDs; five studies compared celecoxib 400 mg daily versus tNSAIDs (Choi 2014; Emery 1999; Jajic 2005; Kivitz 2004; Simon 1999). Follow‐up ranged from six weeks to six months. Pooled analysis showed that the rate of total withdrawals was statistically significantly lower in the celecoxib group compared to tNSAIDs (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.86, P < 0.001; 6 studies, N = 2639; Analysis 2.8). There was no evidence of difference in effect among subgroups (P = 0.46). There were 294/1266 (180 per 1000; range 153 to 212) withdrawals among participants taking celecoxib compared to 339/1373 (247 per 1000) in those taking tNSAIDs, corresponding with 7% absolute change (95% CI 4% to 9%), 27% relative change (95% CI 14% to 38%); NNTH 14 (95% CI 11 to 23), RR 0.73 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.86). This result is based on moderate quality evidence (downgraded due to risk of bias). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 9.24, df = 8, P = 0.32, I² = 13%).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Celecoxib versus NSAIDs, Outcome 8 Total withdrawals (discontinuation rates).

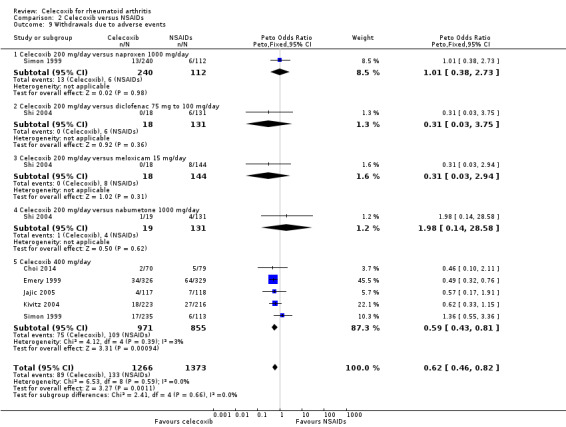

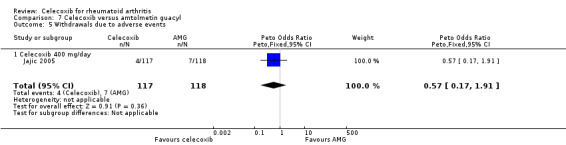

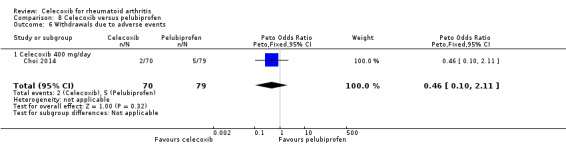

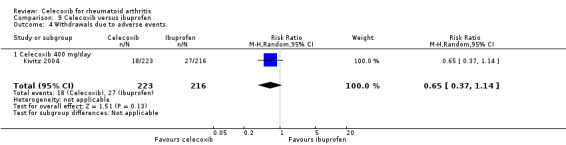

Withdrawals due to adverse events

Shi 2004 and Simon 1999 compared celecoxib 200 mg daily versus tNSAIDs; five studies compared celecoxib 400 mg daily versus tNSAIDs (Choi 2014; Emery 1999; Jajic 2005; Kivitz 2004; Simon 1999). Pooled analysis showed that the rate of total withdrawals due to adverse events was statistically significantly lower in the celecoxib group compared to tNSAIDs (Peto OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.82, P = 0.001; 6 studies, N = 2639; Analysis 2.9). There was no evidence of difference in effect among subgroups (P = 0.74). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 6.53, df = 8, P = 0.59, I² = 0%).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Celecoxib versus NSAIDs, Outcome 9 Withdrawals due to adverse events.

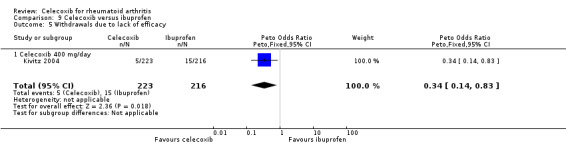

Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy

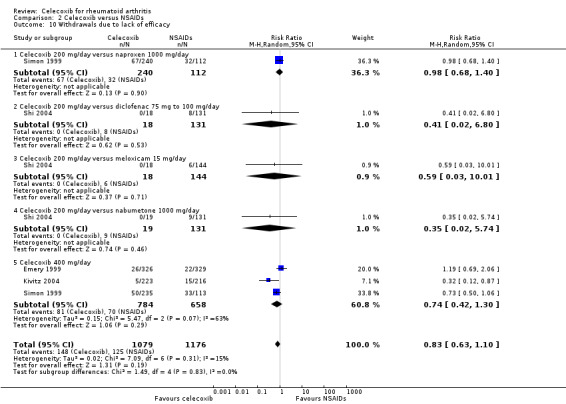

Shi 2004 and Simon 1999 compared celecoxib 200 mg daily versus tNSAIDs; three studies compared celecoxib 400 mg daily versus tNSAIDs (Emery 1999; Kivitz 2004; Simon 1999). Pooled analysis showed that there was no statistically significant difference between celecoxib and other tNSAIDs in rate of withdrawals due to lack of efficacy (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.10, P = 0.19; 4 studies, N = 2255; Analysis 2.10). There was no evidence of difference in effect among subgroups (P = 0.83). Heterogeneity was low (Chi² = 7.09, df = 6, P = 0.31, I² = 15%).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Celecoxib versus NSAIDs, Outcome 10 Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy.

Comparison 3. Celecoxib versus naproxen

Compared to all tNSAIDs, celecoxib induced fewer gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm and was associated with fewer withdrawals. There was no evidence of differences for other review outcomes.

Simon 1999 and Goldstein 2001 provided data for this comparison: Simon 1999 compared 200 mg and 400 mg celecoxib daily with naproxen 1000 mg daily and Goldstein 2001 compared celecoxib 400 mg daily with naproxen 1000 mg.

Primary outcomes

ACR20

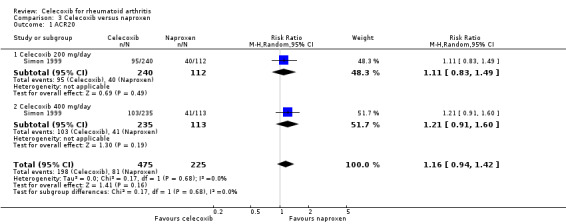

There was no statistically significant difference between celecoxib 200 mg or 400 mg daily and naproxen 1000 mg daily in ACR20 improvement criteria (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.42, P = 0.16; Analysis 3.1). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.17, df = 1, P = 0.68, I² = 0%).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Celecoxib versus naproxen, Outcome 1 ACR20.

Pain

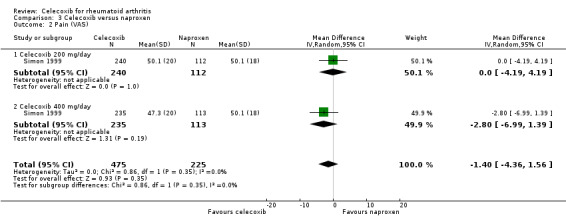

There was no statistically significant difference in pain reduction among groups receiving celecoxib 200 mg or 400 mg daily and naproxen 1000 mg daily (MD ‐1.40, 95% CI ‐4.36 to 1.56, P = 0.35; Analysis 3.2). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.86, df = 1, P = 0.35, I² = 0%).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Celecoxib versus naproxen, Outcome 2 Pain (VAS).

Self‐reported function (Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ))

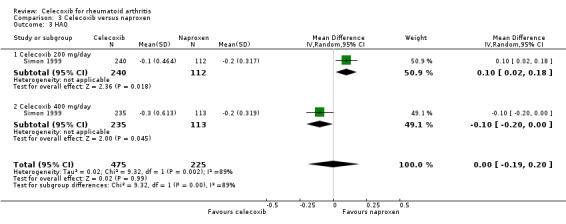

There was no statistically significant difference between celecoxib 200 mg or 400 mg daily and naproxen 1000 mg daily in self‐reported function using the HAQ (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.20, P = 0.99; Analysis 3.3). There was statistically significant heterogeneity (Chi² = 9.32, df = 1, P = 0.002, I² = 89%).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Celecoxib versus naproxen, Outcome 3 HAQ.

Cardiovascular events

No studies reported this outcome.

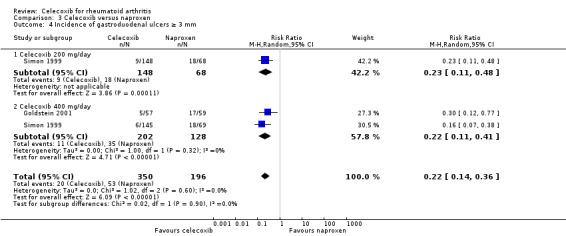

Incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm

The incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm was statistically significant lower in participants receiving celecoxib 200 mg and 400 mg daily compared to naproxen 1000 mg daily (RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.36, P < 0.001; N = 546; Analysis 3.4). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 1.02, df = 2, P = 0.60, I² = 0%).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Celecoxib versus naproxen, Outcome 4 Incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm.

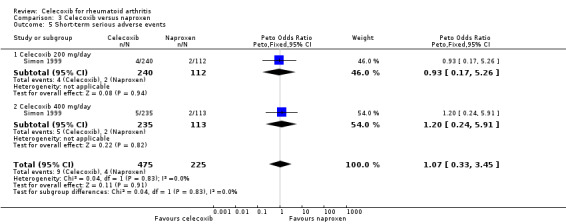

Short‐term serious adverse events

There was no statistically significant difference in incidence of short‐term serious adverse events for celecoxib 200 mg and 400 mg daily and naproxen 1000 mg daily (Peto OR 1.07, 95% CI 0.33 to 3.45, P = 0.91; Analysis 3.5). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.04, df = 1, P = 0.83, I² = 0%).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Celecoxib versus naproxen, Outcome 5 Short‐term serious adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

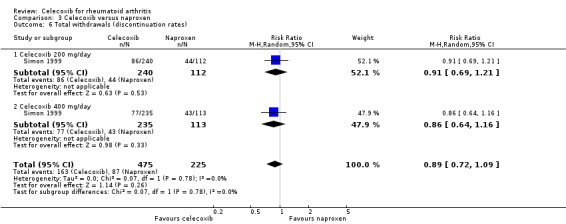

Total withdrawals (discontinuation rates)

There was no statistically significant difference between celecoxib 200 mg and 400 mg daily and naproxen 1000 mg daily in total number of withdrawals (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.09, P = 0.26; Analysis 3.6). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.07, df = 1, P = 0.78, I² = 0%).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Celecoxib versus naproxen, Outcome 6 Total withdrawals (discontinuation rates).

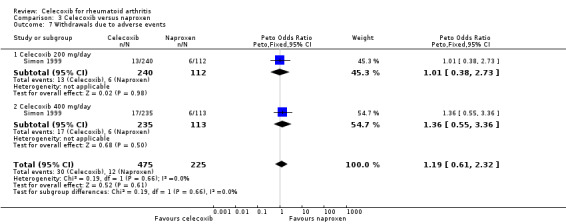

Withdrawals due to adverse events

There was no statistically significant difference between celecoxib 200 mg and 400 mg daily and naproxen 1000 mg daily in withdrawals due to adverse events (Peto OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.32, P = 0.62; Analysis 3.7). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.19, df = 1, P = 0.66, I² = 0%).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Celecoxib versus naproxen, Outcome 7 Withdrawals due to adverse events.

Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy

There was no statistically significant difference between celecoxib 200 mg and 400 mg daily and naproxen 1000 mg daily in withdrawals due to lack of efficacy (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.10, P = 0.23; Analysis 3.8). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.77, df = 1, P = 0.38, I² = 0%).

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Celecoxib versus naproxen, Outcome 8 Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy.

Comparison 4. Celecoxib versus diclofenac

Shi 2004 and Emery 1999 provided data for this comparison: Shi 2004 compared celecoxib 200 mg daily with diclofenac 75‐100 mg daily and Emery 1999 compared and celecoxib 400 mg daily with diclofenac 150 mg daily. Follow‐up duration for both studies was six months.

Primary outcomes

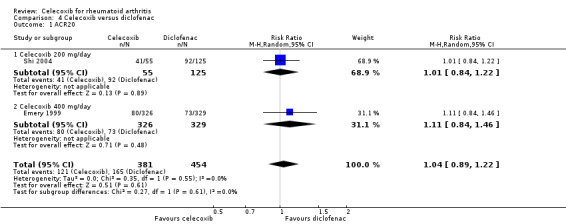

ACR20

Pooled analysis showed no statistically significant difference between 200 mg and 400 mg celecoxib daily and diclofenac in ACR20 improvement criteria (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.22, P = 0.61; 2 studies, N = 835; Analysis 4.1). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.35, df = 1, P = 0.55, I² = 0%).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Celecoxib versus diclofenac, Outcome 1 ACR20.

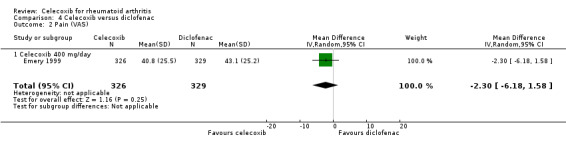

Pain

There was no statistically significant difference between 400 mg celecoxib daily and diclofenac in pain reduction (MD ‐2.30, 95% CI ‐6.18 to 1.58, P = 0.25; 1 study, N = 655; Analysis 4.2). Heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Celecoxib versus diclofenac, Outcome 2 Pain (VAS).

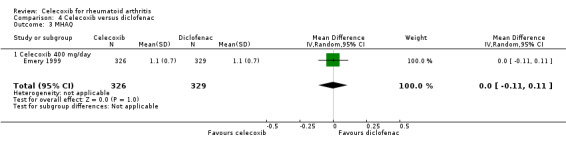

Self‐reported physical function (Modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (MHAQ))

There was no statistically significant difference between 400 mg celecoxib daily and diclofenac in self‐reported function measured on the MHAQ (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.11 to 0.11, P = 1.00; 1 study, N = 655; Analysis 4.3). Heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Celecoxib versus diclofenac, Outcome 3 MHAQ.

Cardiovascular events

No studies reported this outcome.

Incidence of gastroduodenal ulcer ≥ 3 mm

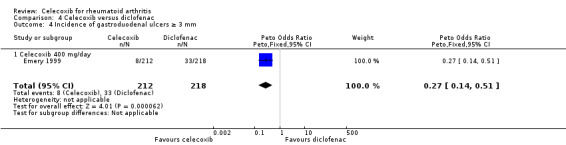

Celecoxib 400 mg daily induced fewer gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm compared to diclofenac (Peto OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.51, P < 0.001; 1 study, N = 655; Analysis 4.4). Heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Celecoxib versus diclofenac, Outcome 4 Incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm.

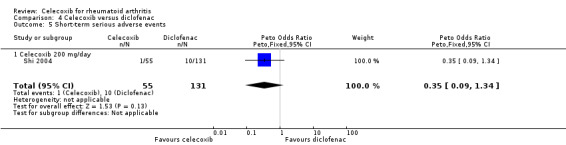

Short‐term serious adverse events

There was no statistically significant difference between celecoxib 200 mg daily and diclofenac in short‐term serious adverse events (Peto OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.09 to 1.34, P = 0.13; 1 study, N = 186; Analysis 4.5). Heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Celecoxib versus diclofenac, Outcome 5 Short‐term serious adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

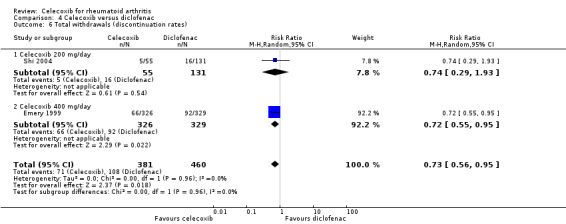

Total withdrawals (discontinuation rates)

Pooled analysis showed that the rate of total withdrawals was significantly lower with celecoxib compared to diclofenac (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.95, P = 0.02; 2 studies, N = 841; Analysis 4.6). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.00, df = 1, P = 0.96, I² = 0%).

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Celecoxib versus diclofenac, Outcome 6 Total withdrawals (discontinuation rates).

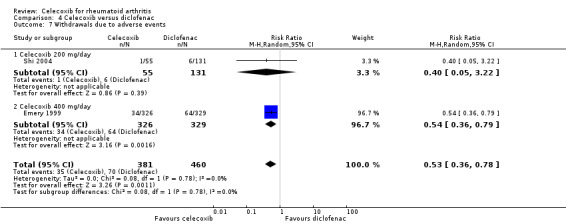

Withdrawals due to adverse events

Pooled analysis showed that the rate of total withdrawals due to adverse events was statistically significant lower with celecoxib compared to diclofenac (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.78, P = 0.001; 2 studies, N = 841; Analysis 4.7). There was no heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.08, df = 1, P = 0.78, I² = 0%).

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Celecoxib versus diclofenac, Outcome 7 Withdrawals due to adverse events.

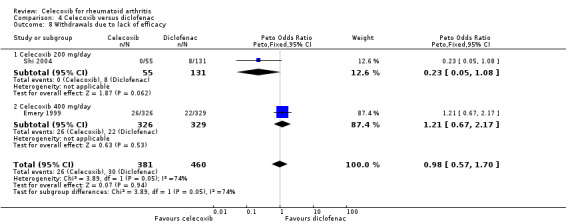

Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy

Pooled analysis showed no statistically significant difference in withdrawals due to lack of efficacy between celecoxib and diclofenac (Peto OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.7, P = 0.94; 2 studies, N = 841; Analysis 4.8). Heterogeneity was moderate (Chi² = 3.89, df = 1, P = 0.05, I² = 74.3%).

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Celecoxib versus diclofenac, Outcome 8 Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy.

Comparison 5. Celecoxib versus meloxicam

Compared with all tNSAIDs, celecoxib induced fewer gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm and fewer withdrawals. These effects were not observed in the comparison of celecoxib and meloxicam; there was no evidence of difference for any outcomes between these drugs alone.

Shi 2004 (N = 199) provided data for this comparison: 200 mg celecoxib daily compared with meloxicam 15 mg daily. Follow‐up duration was six months. Assessment of heterogeneity was not applicable for this comparison.

Primary outcomes

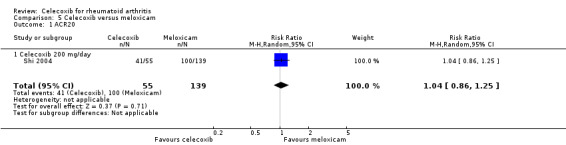

ACR20

There was no statistically significant difference between celecoxib 200 mg daily and meloxicam 15 mg daily in ACR20 criteria (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.25, P = 0.71; Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Celecoxib versus meloxicam, Outcome 1 ACR20.

Pain

No studies reported this outcome.

Self‐reported physical function (Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ))

No studies reported this outcome.

Cardiovascular events

No studies reported this outcome.

Incidence of gastroduodenal ulcer ≥ 3 mm

No studies reported this outcome.

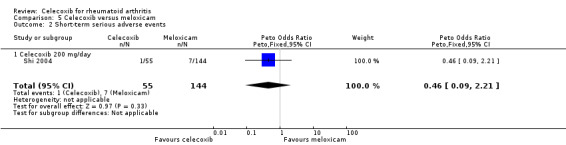

Short‐term serious adverse events

There was no statistically significant difference between celecoxib 200 mg daily and meloxicam 15 mg daily in short term serious adverse events (Peto OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.09 to 2.21, P = 0.33; Analysis 5.2).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Celecoxib versus meloxicam, Outcome 2 Short‐term serious adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

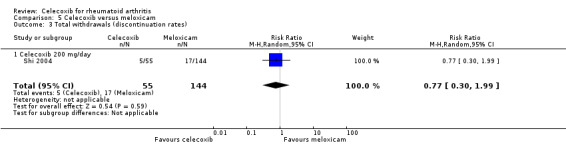

Total withdrawals (discontinuation rates)

There was no statistically significant difference between celecoxib 200 mg daily and meloxicam 15 mg daily in total withdrawals (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.99, P = 0.59; Analysis 5.3).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Celecoxib versus meloxicam, Outcome 3 Total withdrawals (discontinuation rates).

Withdrawals due to adverse events

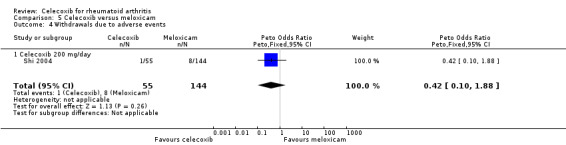

There was no statistically significant difference between celecoxib 200 mg daily and meloxicam 15 mg daily in withdrawals due to adverse events (Peto OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.10 to 1.88, P = 0.26; Analysis 5.4).

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Celecoxib versus meloxicam, Outcome 4 Withdrawals due to adverse events.

Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy

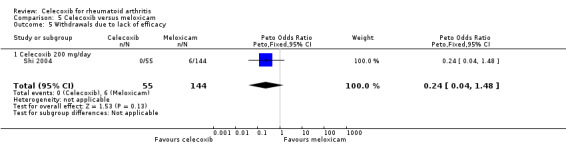

There was no statistically significant difference between celecoxib 200 mg daily and meloxicam 15 mg daily in withdrawals due to lack of efficacy (Peto OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.04 to 1.48, P = 0.13; Analysis 5.5).

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Celecoxib versus meloxicam, Outcome 5 Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy.

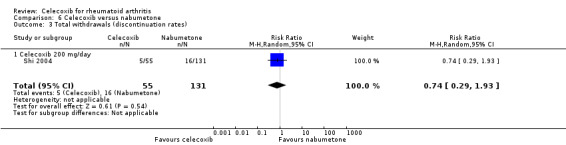

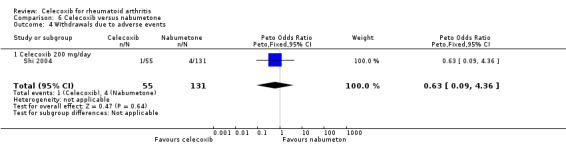

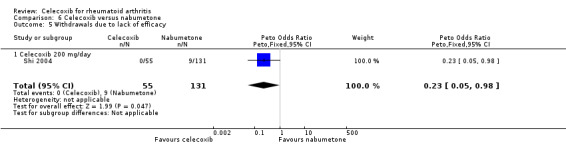

Comparison 6. Celecoxib versus nabumetone

Compared with all tNSAIDs, celecoxib induced fewer gastroduodenal ulcers ≥ 3 mm and fewer withdrawals. These effects were not observed in the comparison of celecoxib and nabumetone; there was no evidence of difference for any outcomes between these drugs alone.

Shi 2004 (N = 182) provided data for this comparison: 200 mg celecoxib daily compared with nabumetone 1000 mg daily. Follow‐up duration was six months. Assessment of heterogeneity was not applicable for this comparison.

Primary outcomes

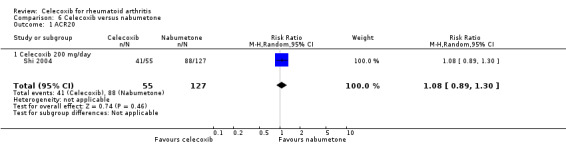

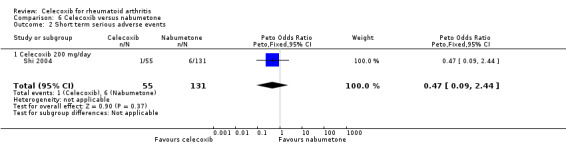

ACR20