Abstract

Background

Electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait‐training devices are used in rehabilitation and might help to improve walking after stroke. This is an update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2007.

Objectives

To investigate the effects of automated electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait‐training devices for improving walking after stroke.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched 9 August 2016), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library 2016, Issue 8), MEDLINE in Ovid (1950 to 15 August 2016), Embase (1980 to 15 August 2016), CINAHL (1982 to 15 August 2016), AMED (1985 to 15 August 2016), Web of Science (1899 to 16 August 2016), SPORTDiscus (1949 to 15 September 2012), the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) (searched 16 August 2016), and the engineering databases COMPENDEX (1972 to 16 November 2012) and Inspec (1969 to 26 August 2016). We handsearched relevant conference proceedings, searched trials and research registers, checked reference lists, and contacted authors in an effort to identify further published, unpublished, and ongoing trials.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials and randomised controlled cross‐over trials in people over the age of 18 years diagnosed with stroke of any severity, at any stage, in any setting, evaluating electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training versus normal care.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials for inclusion, assessed methodological quality and risk of bias, and extracted the data. The primary outcome was the proportion of participants walking independently at follow‐up.

Main results

We included 36 trials involving 1472 participants in this review update. Electromechanical‐assisted gait training in combination with physiotherapy increased the odds of participants becoming independent in walking (odds ratio (random effects) 1.94, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.39 to 2.71; P < 0.001; I² = 8%; moderate‐quality evidence) but did not significantly increase walking velocity (mean difference (MD) 0.04 m/s, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.09; P = 0.08; I² = 65%; low‐quality evidence) or walking capacity (MD 5.84 metres walked in 6 minutes, 95% CI ‐16.73 to 28.40; P = 0.61; I² = 53%; very low‐quality evidence). The results must be interpreted with caution because 1) some trials investigated people who were independent in walking at the start of the study, 2) we found variations between the trials with respect to devices used and duration and frequency of treatment, and 3) some trials included devices with functional electrical stimulation. Our planned subgroup analysis suggested that people in the acute phase may benefit, but people in the chronic phase may not benefit from electromechanical‐assisted gait training. Post hoc analysis showed that people who are non‐ambulatory at intervention onset may benefit, but ambulatory people may not benefit from this type of training. Post hoc analysis showed no differences between the types of devices used in studies regarding ability to walk, but significant differences were found between devices in terms of walking velocity.

Authors' conclusions

People who receive electromechanical‐assisted gait training in combination with physiotherapy after stroke are more likely to achieve independent walking than people who receive gait training without these devices. We concluded that seven patients need to be treated to prevent one dependency in walking. Specifically, people in the first three months after stroke and those who are not able to walk seem to benefit most from this type of intervention. The role of the type of device is still not clear. Further research should consist of large definitive pragmatic phase III trials undertaken to address specific questions about the most effective frequency and duration of electromechanical‐assisted gait training as well as how long any benefit may last.

Plain language summary

Automated training devices for improving walking after stroke

Review question

Do machine‐ and robot‐assisted walking training devices improve walking after stroke?

Background

Many people who have had a stroke have difficulties walking, and improving walking is one of the main goals of rehabilitation. Automated training devices assist walking practice.

Search date

The review is current to August 2016.

Study characteristics

We included 36 studies involving a total of 1472 participants over the age of 18 years with acute, postacute, or chronic ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke. The mean age in the included studies ranged from 48 years to 76 years. The majority of studies were conducted in an inpatient setting.

Key results

We found moderate‐quality evidence that electromechanical‐assisted gait training combined with physiotherapy when compared with physiotherapy alone may improve recovery of independent walking in people after stroke.

We determined that for every seven patients treated with electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training devices, just one prevention of dependency in walking occurs.

Specifically, people in the first three months after stroke and those who are not able to walk appear to benefit most from this type of intervention. The importance of the type of device is still not clear. Further research should address what frequency or duration of walking training might be most effective and how long the benefit lasts. It also remains unclear how such devices should be used in routine rehabilitation.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence for automated electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait‐training devices for improving walking after stroke was moderate. The quality of evidence was low for walking speed, very low for walking capacity, and low for adverse events and people discontinuing treatment.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy compared to physiotherapy (or usual care) for walking after stroke.

| Electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy compared to physiotherapy (or usual care) for walking after stroke | ||||||

| Patient or population: walking after stroke Setting: inpatient and outpatient setting Intervention: electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy Comparison: physiotherapy (or usual care) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with physiotherapy (or usual care) | Risk with electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy | |||||

| Independent walking at the end of intervention phase, all electromechanical devices used Assessed with FAC | Study population | OR 1.94 (1.39 to 2.71) | 1472 (36 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 457 per 1000 | 615 per 1000 (530 to 693) | |||||

| Recovery of independent walking at follow‐up after study end Assessed with FAC | Study population | OR 1.93 (0.72 to 5.13) | 496 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 551 per 1000 | 703 per 1000 (469 to 863) | |||||

| Walking velocity (metres per second) at the end of intervention phase Assessed with timed measures of gait Scale: 0 to infinity | The mean walking velocity (metres per second) at the end of intervention phase was 0. | MD 0.04 higher (0 to 0.09 higher) | ‐ | 985 (24 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Walking velocity (metres per second) at follow‐up Assessed with timed measures of gait Scale: 0 to infinity | The mean walking velocity (metres per second) at follow‐up was 0. | MD 0.07 higher (0.05 lower to 0.19 higher) | ‐ | 578 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Walking capacity (metres walked in 6 minutes) at the end of intervention phase Assessed with timed measures of gait Scale: 0 to infinity | The mean walking capacity (metres walked in 6 minutes) at the end of intervention phase was 0. | MD 5.84 higher (16.73 lower to 28.40 higher) | ‐ | 594 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 4 | |

| Walking capacity (metres walked in 6 minutes) at follow‐up | The mean walking capacity (metres walked in 6 minutes) at follow‐up was 0. | MD 0.82 lower (32.17 lower to 30.53 higher) | ‐ | 463 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 4 | |

| Acceptability of electromechanical‐assisted gait‐training devices during intervention phase Assessed with number of dropouts | Study population | OR 0.67 (0.43 to 1.05) | 1472 (36 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 5 | ||

| 131 per 1000 | 92 per 1000 (61 to 136) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; FAC: Functional Ambulation Category; MD: mean difference; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

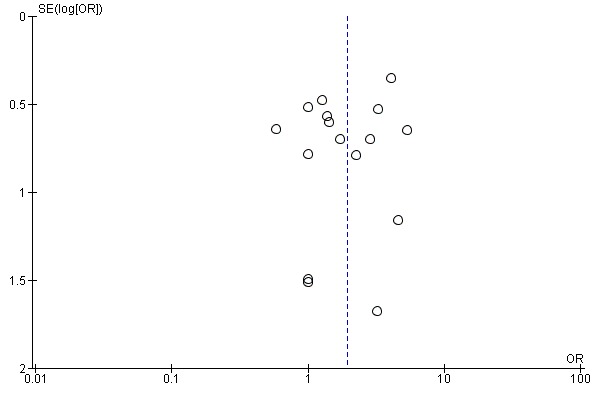

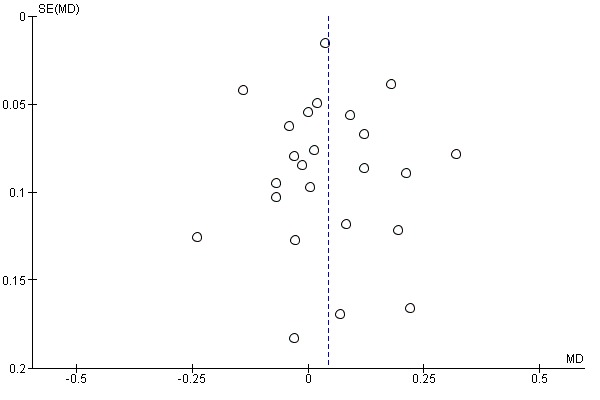

1Downgraded due to several ratings of 'unclear' and 'high' risk of bias. 2Downgraded due to statistical heterogeneity and no overlap of several confidence intervals. 3Downgraded because the 95% confidence interval includes no effect and the upper confidence limit crosses the minimal important difference. 4Downgraded due to funnel plot asymmetry. 5Downgraded because the total number of events (157) is less than 300 (a threshold rule‐of‐thumb value).

Background

Description of the condition

A stroke is a sudden, non‐convulsive loss of neurological function due to an ischaemic or haemorrhagic intracranial vascular event (WHO 2006). In general, cerebrovascular accidents are classified by anatomic location in the brain, vascular distribution, aetiology, age of the affected individual, and haemorrhagic versus non‐haemorrhagic nature (Adams 1993). Stroke is a leading cause of death and serious long‐term disability in adults. Three months after stroke, 20% of people remain wheelchair bound, and approximately 70% walk at a reduced velocity and capacity (Jorgensen 1995). Restoration of walking ability and gait rehabilitation are therefore highly relevant for people who are unable to walk independently after stroke (Bohannon 1991), as well as for their relatives. To restore gait, modern concepts of rehabilitation favour a repetitive task‐specific approach (Carr 2003; French 2007). In recent years it has also been shown that higher intensities of walking practice (resulting in more repetitions trained) resulted in better outcomes for people after stroke (Kwakkel 1999; Van Peppen 2004).

Description of the intervention

As an adjunct to overground gait training (States 2009), in recent years treadmill training has been introduced for the rehabilitation of people after stroke (Mehrholz 2014). Treadmill training with and without partial body weight support enables the repetitive practice of complex gait cycles for these people. However, one disadvantage of treadmill training might be the effort required by therapists to set the paretic limbs and to control weight shift, thereby possibly limiting the intensity of therapy, especially in more severely disabled people. Automated electromechanical gait machines were developed to reduce dependence on therapists. They consist of either a robot‐driven exoskeleton orthosis or an electromechanical solution, with two driven foot plates simulating the phases of gait (Colombo 2000; Hesse 1999).

One example of automated electromechanical gait rehabilitation is the Lokomat (Colombo 2000). A robotic gait orthosis combined with a harness‐supported body weight system is used together with a treadmill. The main difference from treadmill training is that the patient's legs are guided by the robotic device according to a preprogrammed gait pattern. A computer‐controlled robotic gait orthosis guides the patient, and the process of gait training is automated.

A second example is the Gait Trainer GT I, which is based on a double crank and rocker gear system (Hesse 1999). In contrast to a treadmill, the electromechanical Gait Trainer GT I consists of two foot plates positioned on two bars, two rockers, and two cranks, which provide the propulsion. The harness‐secured patient is positioned on the foot plates, which symmetrically simulate the stance and swing phases of walking (Hesse 1999). A servo‐controlled motor guides the patient during walking exercise. Vertical and horizontal movements of the trunk are controlled in a phase‐dependent manner. Again, the main difference from treadmill training is that the process of gait training is automated and is supported by an electromechanical solution.

Other similar electromechanical devices that have been developed in recent years include the Haptic Walker (Schmidt 2005), the Anklebot (MIT 2005), and the LOPES (Lower Extremity Powered Exoskeleton) (Veneman 2005). More recently, new so‐called powered mobile solutions, Buesing 2015, Stein 2014, Watanabe 2014, and ankle robots, Forrester 2014, Waldman 2013, to improve walking have been described in the literature.

How the intervention might work

Electromechanical devices (such as those previously described) can be used to give non‐ambulatory patients intensive practice (in terms of high repetitions) of complex gait cycles. The advantage of these electromechanical devices compared with treadmill training with partial body weight support may be the reduced effort required of therapists, as they no longer need to set the paretic limbs or assist trunk movements (Hesse 2003).

Why it is important to do this review

Scientific evidence for the benefits of the above‐mentioned technologies may have changed since our Cochrane Review was first published in 2007 (Mehrholz 2007), and so an update of the review was required to justify the large equipment and human resource costs needed to implement electromechanical‐assisted gait devices, as well as to confirm the safety and acceptance of this method of training. The aim of this review was therefore to provide an update of the best available evidence about the above‐mentioned approach.

Objectives

To investigate the effects of automated electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait‐training devices for improving walking after stroke.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We searched for all randomised controlled trials and randomised controlled cross‐over trials for inclusion in this review. If we included randomised controlled cross‐over trials, we planned to analyse only the first period as a parallel‐group trial.

Types of participants

We included studies with participants of any gender over 18 years of age after stroke, using the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of stroke or a clinical definition of stroke if the WHO definition was not specifically stated (WHO 2006).

Types of interventions

We included all trials that evaluated electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy versus physiotherapy (or usual care) for regaining and improving walking after stroke. We also included automated electromechanical devices that were used in combination with therapies such as functional electrical stimulation applied to the legs during gait training (compared with therapies not using electromechanical devices). We defined an automated electromechanical device as any device with an electromechanical solution designed to assist stepping cycles by supporting body weight and automating the walking therapy process in people after stroke. This category included any mechanical or computerised device designed to improve walking function. We also searched for electromechanical devices such as robots for gait training after stroke (MIT 2005; Schmidt 2005; Veneman 2005).

Electromechanical devices can principally be differentiated into end‐effector and exoskeleton devices. Examples of end‐effector devices are the LokoHelp (Freivogel 2009), the Haptic Walker (Schmidt 2005), and the Gait Trainer GT I (Hesse 1999). The definition of an end‐effector principle is that a patient's feet are placed on foot plates, whose trajectories simulate the stance and swing phases during gait training (Hesse 2010). An example of exoskeleton devices is the Lokomat (Colombo 2000). Such exoskeletons are outfitted with programmable drives or passive elements, which move the knees and hips during the phases of gait (Hesse 2010).

We did not include non‐weight‐bearing interventions such as non‐interactive devices that deliver continuous passive motion only (Nuyens 2002). We excluded trials testing the effectiveness of treadmill training or other approaches such as repetitive task training in physiotherapy or electrical stimulation alone (French 2016; Pollock 2014), to prevent duplication with other Cochrane Reviews and protocols (e.g. Mehrholz 2014).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Regaining the ability to walk is a very important goal for people after stroke (Bohannon 1988). We therefore defined the primary outcome as the ability to walk independently. We measured the ability to walk with the Functional Ambulation Category (FAC) (Holden 1984). A FAC score of 4 or 5 indicated independent walking over a 15‐metre surface, irrespective of aids used such as a cane. A FAC score of less than 4 indicates dependency in walking (supervision or assistance, or both must be given in performing walking).

If the included studies did not report FAC scores, we used alternative indicators of independent walking, such as:

a score of 3 on the ambulation item of the Barthel Index (Wade 1988); or

a score of 6 or 7 for the walking item of the Functional Independence Measure (Hamilton 1994); or

a 'yes' response to the item 'walking inside, with an aid if necessary (but with no standby help)' or 'yes' to 'walking on uneven ground' in the Rivermead Mobility Index (Collen 1991).

Secondary outcomes

We defined secondary outcomes as measures of activity limitations. We used walking speed (in metres per second), walking capacity (metres walked in 6 minutes), and the Rivermead Mobility Index score as relevant measures of activity limitations, if stated by the trialists. Additionally, we used death from all causes as a secondary outcome.

Adverse outcomes

We investigated the safety of electromechanical‐assisted gait‐training devices with the incidence of adverse outcomes such as thrombosis, major cardiovascular events, injuries, pain, and any other reported adverse events. To measure the acceptance of electromechanical‐assisted gait‐training devices in walking therapies, we used visual analogue scales or withdrawal from the study for any reason (dropout rates), or both during the study period, depending on data provided by the study authors.

Depending on the above‐stated categories and the availability of variables used in the included trials, we discussed and reached consensus on which outcome measures should be included in the analysis.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module. We searched for trials in all languages and arranged for translation of relevant papers published in languages other than English.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched August 2016) and the following electronic bibliographic databases:

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library, Issue 8, 2016) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE in Ovid (1950 to 15 August 2016) (Appendix 2);

Embase (1980 to 15 August 2016) (Appendix 3);

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) in EBSCO (1982 to 15 August 2016) (Appendix 4);

AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database) (1985 to 15 August 2016) (Appendix 5);

Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts and Humanities Citation Index) (1899 to 16 August 2016) (Appendix 6);

PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database) (searched 16 August 2016) (Appendix 7);

COMPENDEX (1972 to 16 November 2012) (Appendix 8);

SPORTDiscus (1949 to 15 September 2012) (Appendix 9); and

Inspec (1969 to 26 August 2016) (Appendix 10).

We developed the search strategies with the help of the Cochrane Stroke Group Information Specialist and adapted the MEDLINE search strategy for the other databases.

We identified and searched the following ongoing trials and research registers:

International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register at www.isrctn.com/ (searched August 2016);

ClinicalTrials.gov at www.clinicaltrials.gov (searched 27 August 2016);

Stroke Trials Register at www.strokecenter.org (searched 27 August 2016); and

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) at apps.who.int/trialsearch/ (searched 27 August 2016) (Appendix 11).

Searching other resources

We also:

-

handsearched the following relevant conference proceedings:

World Congress of NeuroRehabilitation (2002, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016);

World Congress of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, and 2015);

World Congress of Physical Therapy (2003, 2007, 2011, and 2015);

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurotraumatologie und Klinische Neurorehabilitation (2001 to 2015);

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie (2000 to 2016);

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurorehabilitation (1999 to 2016); and

Asia‐Oceanian Conference of Physical & Rehabilitation Medicine (2008 to 2016).

screened reference lists of all relevant articles; and

contacted trialists, experts, and researchers in our field of study.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (JM, BE) independently read the titles and abstracts of the identified references and eliminated obviously irrelevant studies. We obtained the full text for the remaining studies. Based on our inclusion criteria (types of studies, participants, aims of interventions, outcome measures), the same two review authors independently ranked these studies as relevant, irrelevant, or possibly relevant. We excluded all trials ranked initially as irrelevant but included all other trials at this stage. We excluded all trials of specific treatment components, such as electrical stimulation as stand‐alone treatment, treadmill training, and continuous passive motion treatment, because these have been the subject of other Cochrane Reviews (e.g. Mehrholz 2014). We resolved any disagreements through discussion between all four review authors. If we required further information to reach consensus, we contacted trialists in an attempt to obtain the missing information. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram, and listed all studies that did not match our inclusion criteria regarding types of studies, participants, and aims of interventions in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (JM, BE) independently extracted trial and outcome data from the selected trials. We established the characteristics of unpublished trials through correspondence with the trial co‐ordinator or principal investigator. If any review author was involved in any of the selected studies, another review author not involved in the study extracted the study information. If there was any doubt as to whether a study should be excluded, we retrieved the full text of the article. In cases of disagreement between the two review authors, a third review author (JK) reviewed the information to decide on inclusion or exclusion of a study. We used checklists to independently record the following details.

Methods of generating the randomisation schedule.

Method of concealment of allocation.

Blinding of assessors.

Use of an intention‐to‐treat analysis (all participants initially randomly assigned were included in the analyses as allocated to groups).

Adverse events and dropouts for all reasons.

Important imbalance in prognostic factors.

Participants (country, number of participants, age, gender, type of stroke, time from stroke onset to entry to the study, inclusion and exclusion criteria).

Comparison (details of the intervention in treatment and control groups, details of co‐intervention(s) in both groups, duration of treatment).

Outcomes and time points of measures (number of participants in each group and outcome, regardless of compliance).

The two review authors checked all of the extracted data for agreement, with a third review author (JK) arbitrating any items for which consensus could not be reached. If necessary, we contacted trialists to request more information, clarification, and missing data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (JM, MP) independently evaluated the methodological quality of the included trials using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool, as described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a).

We checked all methodological quality assessments for agreement between review authors. We resolved disagreements by discussion. If one of the review authors was a co‐author of an included trial, another review author (BE or JK) conducted the methodological quality assessment for this trial in this case.

Measures of treatment effect

We planned to compare electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy versus physiotherapy (or usual care) for primary and secondary outcome parameters. We used the effect measures odds ratio (OR) or mean difference (MD) in the meta‐analyses.

Unit of analysis issues

We analysed binary (dichotomous) outcomes with an OR, random‐effects model with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We analysed continuous outcomes with MDs, using the same outcome scale. We used a random‐effects model for all analyses. We used Cochrane Review Manager 5 software for all statistical comparisons, (RevMan 2014).

Dealing with missing data

In the case of missing outcome data, we attempted to analyse data according to the intention‐to‐treat approach. We contacted the trial co‐ordinator or principal investigator if data were missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I² statistic to assess heterogeneity. We used a random‐effects model, regardless of the level of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We inspected funnel plots to assess the risk of publication bias.

Data synthesis

GRADE and 'Summary of findings' table

We created two 'Summary of findings' tables using the following outcomes.

Primary outcome measure: Independent walking at the end of intervention phase, all electromechanical devices used. Scale from 0 to infinity.

Primary outcome measure: Recovery of independent walking at follow‐up after study end. Scale from 0 to infinity.

Primary outcome measure: Walking velocity (metres per second) at the end of intervention phase. Scale from 0 to infinity.

Secondary outcome measure: Walking velocity (metres per second) at follow‐up. Scale from 0 to infinity.

Secondary outcome measure: Walking capacity (metres walked in 6 minutes) at the end of intervention phase. Scale from 0 to infinity.

Secondary outcome measure: Walking capacity (metres walked in 6 minutes) at follow‐up. Scale from 0 to infinity.

Secondary outcome measure: Acceptability of electromechanical‐assisted gait‐training devices during intervention phase: number of dropouts.

We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the quality of a body of evidence as it relates to the studies that contribute data to the meta‐analyses for the prespecified outcomes (Atkins 2004). We used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b), employing GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT). We justified all decisions to down‐ or upgrade the quality of studies using footnotes, and made comments to aid the reader's understanding of the review where necessary.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

As planned in our protocol (Mehrholz 2006), we performed a formal subgroup analysis following the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011), comparing participants treated in the acute and subacute phases of their stroke (within three months) with participants treated in the chronic phase (longer than three months).

Sensitivity analysis

As planned in our protocol, we performed a sensitivity analysis of methodological quality for each included study.

We carried out the following sensitivity analyses by including only those studies:

with an adequate sequence generation process;

with adequate concealed allocation;

with blinded assessors for the primary outcome; and

without incomplete outcome data.

We considered it necessary to do a further sensitivity analysis by removing the largest study, Pohl 2007, because some of the review authors (JM, MP, and CW) were investigators in this large trial. We carried out this sensitivity analysis by including all studies without the largest study (Pohl 2007).

We performed two further (post hoc) sensitivity analyses.

Ambulatory status at start of study (including only studies that included an independent walker; including only studies that included dependent and independent walkers; and including only studies that included a dependent walker).

Type of device used in trials (including only studies that used end‐effector devices and including only studies that used exoskeleton devices).

Results

Description of studies

See the Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

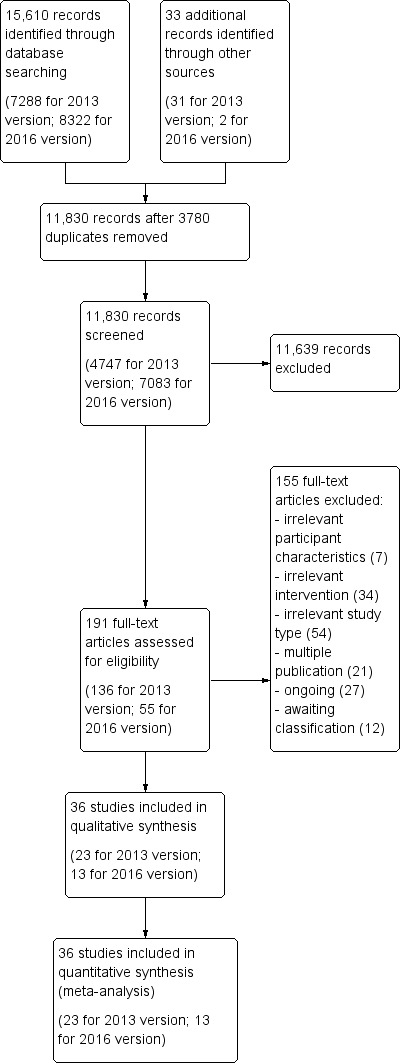

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the selection of studies for this update.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Searches of the electronic databases and trials registers generated 7083 new unique references for screening. After excluding non‐relevant citations, we obtained the full text of 55 new papers, and from these identified and included 13 new trials in the review.

Included studies

We included 36 trials involving a total of 1472 participants (see the Characteristics of included studies, Figure 1, Table 7, and Table 8). All included studies investigated the effects of electromechanical‐ or robotic‐assisted gait‐training devices in improving walking after stroke.

1. Participant characteristics in studies.

| Study ID |

Experimental: age, mean (SD) |

Control: age, mean (SD) |

Experimental: time poststroke |

Control: time poststroke |

Experimental: sex |

Control: sex |

Experimental: side paresis |

Control: side paresis |

| Aschbacher 2006 | 57 years | 65 years | ≤ 3 months | ≤ 3 months | 2 female | 4 female | Not stated | Not stated |

| Bang 2016 | 54 years | 54 years | 12 months | 13 months | 5 male, 4 female | 4 male, 5 female | 4 right, 5 left | 4 right, 5 left |

| Brincks 2011 | 61 (median) years | 59 (median) years | 56 (median) days | 21 (median) days | 5 male, 2 female | 4 male, 2 female | 5 right, 2 left | 1 right, 5 left |

| Buesing 2015 | 60 years | 62 years | 7 years | 5 years | 17 male, 8 female | 16 male, 9 female | 13 right, 12 left | 12 right, 13 left |

| Chang 2012 | 56 (12) years | 60 (12) years | 16 (5) days | 18 (5) days | 13 male, 7 female | 10 male, 7 female | 6 right, 14 left | 6 right, 11 left |

| Cho 2015 | 55 (12) years | 55 (15) years | 15 months | 13 months | Not stated | Not stated | 6 right, 4 left (4 both) | 3 right, 1 left (3 both) |

| Chua 2016 | 62 (10) years | 61 (11) years | 27 (11) days | 30 (14) days | 35 male, 18 female | 40 male, 13 female | 24 right, 29 left | 21 right, 32 left |

| Dias 2006 | 70 (7) years | 68 (11) years | 47 (64) months | 48 (30) months | 16 male, 4 female | 14 male, 6 female | Not stated | Not stated |

| Fisher 2008 | Not stated | Not stated | Less than 12 months | Less than 12 months | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Forrester 2014 | 63 years | 60 years | 12 days | 11 days | Not stated | Not stated | 9 right, 9 left | 7 right, 9 left |

| Geroin 2011 | 63 (7) years | 61 (6) years | 26 (6) months | 27 (6) months | 14 male, 6 female | 9 male, 1 female | Not stated | Not stated |

| Han 2016 | 68 (15) years | 63 (11) years | 22 (8) days | 18 (10) days | Not stated | Not stated | 20 right, 10 left | 14 right, 12 left |

| Hidler 2009 | 60 (11) years | 55 (9) years | 111 (63) days | 139 (61) days | 21 male, 12 female | 18 male, 12 female | 22 right, 11 left | 13 right, 17 left |

| Hornby 2008 | 57 (10) years | 57 (11) years | 50 (51) months | 73 (87) months | 15 male, 9 female | 15 male, 9 female | 16 right, 8 left | 16 right, 8 left |

| Husemann 2007 | 60 (13) years | 57 (11) years | 79 (56) days | 89 (61) days | 11 male, 5 female | 10 male, 4 female | 12 right, 4 left | 11 right, 3 left |

| Kim 2015 | 54 (13) years | 50 (16) years | 80 (60) days | 120 (84) days | 9 male, 4 female | 10 male, 3 female | 8 right, 5 left | 10 right, 3 left |

| Kyung 2008 | 48 (8) years | 55 (16) years | 22 (23) months | 29 (12) months | 9 male, 8 female | 4 male, 4 female | 9 right, 8 left | 4 right, 4 left |

| Mayr 2008 | Not stated | Not stated | Between 10 days and 6 months | Between 10 days and 6 months | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Morone 2011 | 62 (11) years | 62 (14) years | 19 (11) days | 20 (14) days | 15 male, 9 female | 13 male, 11 female | 13 right, 11 left | 15 right, 9 left |

| Noser 2012 | 67 (9) years | 64 (11) years | 1354 days | 525 days | 7 male, 4 female | 6 male, 4 female | Not stated | Not stated |

| Ochi 2015 | 62 (8) years | 66 (12) years | 23 (7) days | 26 (8) days | 11 male, 2 female | 9 male, 4 female | 6 right, 7 left | 5 right, 8 left |

| Peurala 2005 | 52 (8) years | 52 (7) years | 2.5 (2.5) years | 4.0 (5.8) years | 26 male, 4 female | 11 male, 4 female | 13 right, 17 left | 10 right, 5 left |

| Peurala 2009 | 67 (9) years | 68 (10) years | 8 (3) days | 8 (3) days | 11 male, 11 female | 18 male, 16 female | 11 right, 11 left | 14 right, 20 left |

| Picelli 2016 | 62 (10) years | 65 (3) years | 6 (4) years | 6 (4) years | 7 male, 4 female | 9 male, 2 female | Not stated | Not stated |

| Pohl 2007 | 62 (12) years | 64 (11) years | 4.2 (1.8) weeks | 4.5 (1.9) weeks | 50 male, 27 female | 54 male, 24 female | 36 right, 41 left | 33 right, 45 left |

| Saltuari 2004 | 62 (13) years | 60 (19) years | 3.6 (4.6) months | 1.9 (0.8) months | 4 male, 4 female | 2 male, 6 female | Not stated | Not stated |

| Schwartz 2006 | 62 (9) years | 65 (8) years | 22 (9) days | 24 (10) days | 21 male, 16 female | 20 male, 10 female | 17 right, 20 left | 8 right, 22 left |

| Stein 2014 | 58 (11) years | 57 (15) years | 49 (39) months | 89 (153) months | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Tanaka 2012 | 63 (10) years | 60 (9) years | 55 (37) months | 65 (67) months | 10 male, 2 female | 9 right, 3 left | ||

| Tong 2006 | 71 (14) years | 64 (10) years | 2.5 (1.2) weeks | 2.7 (1.2) weeks | 19 male, 11 female | 12 male, 8 female | 13 right, 17 left | 7 right, 13 left |

| Ucar 2014 | 56 years | 62 years | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Van Nunen 2012 | 53 (10) years | 2.1 (1.3) months | 16 male, 14 female | Not stated | Not stated | |||

| Waldman 2013 | 51 (8) years | 53 (7) years | 41 (20) months | 30 (22) months | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Watanabe 2014 | 67 (17) years | 76 (14) years | 59 (47) days | 51 (34) days | 7 male, 4 female | 4 male, 7 female | 6 right, 5 left | 5 right, 6 left |

| Werner 2002 | 60 (9) years | 60 (9) years | 7.4 (2.0) weeks | 6.9 (2.1) weeks | 8 male, 7 female | 5 male, 10 female | 8 right, 7 left | 8 right, 7 left |

| Westlake 2009 | 59 (17) years | 55 (14) years | 44 (27) months | 37 (20) months | 6 male, 2 female | 7 male, 1 female | 4 right, 4 left | 3 right, 5 left |

SD: standard deviation

2. Demographics of studies including dropouts and adverse events.

| Criteria | Stroke severity | Electromechanical device used | Duration of study intervention | Aetiology (ischaemic/haemorrhage) | Intensity of treatment per day | Description of the control intervention | Dropouts |

Reasons for dropout and adverse events in the experimental group |

Reasons for dropout and adverse events in the control group |

Source of information |

| Aschbacher 2006 | Not stated | Lokomat | 3 weeks | Not stated | 30 minutes, 5 times a week | Described as task‐oriented physiotherapy, 5 times a week for 3 weeks (2.5 hours a week) | 4 of 23 | Not stated | Not stated | Unpublished information in the form of a conference presentation |

| Bang 2016 | Unclear | Lokomat | 4 weeks | 13/5 | 60 minutes, 5 times a week (20 sessions) | Described as treadmill training without body weight support | 0 of 18 | ‐ | ‐ | Published information |

| Brincks 2011 | Mean FIM, 92 of 126 points | Lokomat | 3 weeks | Not stated | Not stated | Physiotherapy | 0 of 13 | ‐ | ‐ | Unpublished and published information provided by the authors. |

| Buesing 2015 | Unclear | Wearable exoskeleton Stride Management Assist system (SMA) | 6 to 8 weeks | Unclear | 3 times per week for a maximum of 18 sessions | Functional task‐specific training (intensive overground training and mobility training) | 0 of 50 | ‐ | ‐ | Published information |

| Chang 2012 | Not stated | Lokomat | 10 days | Not stated | 30 minutes daily for 10 days | Conventional gait training by physical therapists (with equal therapy time and same amount of sessions as experimental group) | 3 of 40 | Not described by group (3 participants dropped out: 1 due to aspiration pneumonia, and 2 were unable to co‐operate fully with the experimental procedure) |

Unpublished and published information provided by the authors. | |

| Cho 2015 | Mean Modified Barthel Index, 36 points | Lokomat | 8 weeks (2 phases, cross‐over after 4 weeks) | 4/14 (2 both) | 30 minutes, 3 times a week for 4 weeks | Bobath (neurophysiological exercises, inhibition of spasticity and synergy pattern) | 0 of 20 | ‐ | ‐ | Published information |

| Chua 2016 | Mean Barthel Index, 49 points | Gait Trainer | 8 weeks | Not stated | Not stated | Physiotherapy including 25 minutes of stance/gait, 10 minutes cycling, 10 minutes tilt table standing | 20 of 106 | 2 death, 3 refusal, 1 medical problem, 1 transport problem (1 pain as adverse event) |

1 death, 6 refusal, 3 medical problem, 1 administrative problem (no adverse events) |

Published information |

| Dias 2006 | Mean Barthel Index, 75 points | Gait Trainer | 4 weeks | Not stated | 40 minutes, 5 times a week | Bobath method, 5 times a week for 5 weeks | 0 of 40 | ‐ | ‐ | Unpublished and published information provided by the authors. |

| Fisher 2008 | Not stated | AutoAmbulator | 24 sessions | Not stated | Minimum of 3 sessions a week up to 5 sessions; number of minutes in each session unclear | "Standard" physical therapy, 3 to 5 times a week for 24 consecutive sessions | 0 of 20 | 14 adverse events, no details provided |

11 adverse events, no details provided |

Unpublished and published information provided by the authors. |

| Forrester 2014 | Mean FIM walk 1 point | Anklebot | 8 to 10 sessions (with ca. 200 repetitions) | Not stated | 60 minutes, 8 to 10 sessions | Stretching of the paretic ankle | 5 of 34 | Total of 5 dropouts in both groups (1 medical complication, 1 discharge prior study end, 2 time poststroke > 49 days, 1 non‐compliance) | Published information provided by the authors. | |

| Geroin 2011 | Mean European Stroke Scale, 80 points | Gait Trainer | 2 weeks | Not stated | 50 minutes, 5 times a week | Walking exercises according to the Bobath approach | 0 of 30 | ‐ | ‐ | Unpublished and published information provided by the authors. |

| Han 2016 | Not stated | Lokomat | 4 weeks | 33/23 | 30 minutes, 5 times a week | Neurodevelopmental techniques for balance and mobility | 4 0f 60 | ‐ | 4 unclear reasons | Published information provided by the authors. |

| Hidler 2009 | Not stated | Lokomat | 8 to 10 weeks (24 sessions) | 47/16 | 45 minutes, 3 days a week | Conventional gait training, 3 times a week for 8 to 10 weeks (24 sessions), each session lasted 1.5 hours | 9 of 72 | Not described by group (9 withdrew or were removed because of poor attendance or a decline in health, including 1 death, which according to the authors was unrelated to study) |

Unpublished and published information provided by the authors. | |

| Hornby 2008 | Not stated | Lokomat | 12 sessions | 22/26 | 30 minutes, 12 sessions | Therapist‐assisted gait training, 12 sessions, each session lasted 30 minutes | 14 of 62 | 4 participants dropped out (2 discontinued secondary to leg pain during training, 1 experienced pitting oedema, and 1 had travel limitations) |

10 participants dropped out (4 discontinued secondary to leg pain, 1 experienced an injury outside therapy, 1 reported fear of falling during training, 1 presented with significant hypertension, 1 had travel limitations, and 2 experienced subjective exercise intolerance) |

Published information provided by the authors. |

| Husemann 2007 | Median Barthel Index, 35 points | Lokomat | 4 weeks | 22/8 | 30 minutes, 5 times a week | Conventional physiotherapy, 30 minutes per day for 4 weeks | 2 of 32 | 1 participant enteritis | 1 participant pulmonary embolism | Information as provided by the authors |

| Kim 2015 | Mean Barthel Index, 20 points | Walkbot | 4 weeks | 13/13 | 30 minutes, 5 times a week | Conventional physiotherapy (bed mobility, stretching, balance training, strengthening, symmetry training, treadmill training) | 4 of 30 | 1 rib fracture, 3 decline in health condition | Information as provided by the authors | |

| Kyung 2008 | Not stated | Lokomat | 4 weeks | 18/7 | 45 minutes, 3 days a week | Conventional physiotherapy, received equal time and sessions of conventional gait training | 10 of 35 | 1 participant dropped out for private reasons (travelling); adverse events not described |

9 participants refused after randomisation (reasons not provided); adverse events not described | Unpublished and published information provided by the authors. |

| Mayr 2008 | Not stated | Lokomat | 8 weeks | Not stated | Not stated | Add‐on conventional physiotherapy, received equal time and sessions of conventional gait training | 13 of 74 | 4 participants dropped out (reasons not provided); adverse events not described | 9 participants dropped out (reasons not provided) | Unpublished and published information provided by the authors. |

| Morone 2011 | Canadian Neurological Scale, 6 points | Gait Trainer | 4 weeks | 41/7 | 40 minutes, 5 times a week | Focused on trunk stabilisation, weight transfer to the paretic leg, and walking between parallel bars or on the ground. The participant was helped by 1 or 2 therapists and walking aids if necessary. | 21 of 48 | 12 (hypotension, referred weakness, knee pain, urinary infection, uncontrolled blood pressure, fever, absence of physiotherapist) | 9 (hypotension, referred weakness, knee pain, ankle pain, uncontrolled blood pressure, fever, absence of physiotherapist) | Information as provided by the authors |

| Noser 2012 | Not stated | Lokomat | Unclear | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | 1 of 21 | No dropouts; 2 serious adverse events (1 skin breakdown as a result of therapy, 1 second stroke during the post‐treatment phase) |

1 dropout due to protocol violation; 2 serious adverse events (1 sudden drop in blood pressure at participant's home leading to brief hospitalisation, 1 sudden chest pain before therapy leading to brief hospitalisation) |

Information as provided by the authors |

| Ochi 2015 | Not stated | Gait‐assistance robot (consisting of 4 robotic arms for the thighs and legs, thigh cuffs, leg apparatuses, and a treadmill) | 4 weeks | 10/16 | 20 minutes, 5 times a week for 4 weeks, in addition to rehabilitation treatment | Range‐of‐motion exercises, muscle strengthening, rolling over and sit‐to‐stand and activity and gait exercises | 0 of 26 | ‐ | ‐ | Published information |

| Peurala 2005 | Scandinavian Stroke Scale, 42 points | Gait Trainer | 3 weeks | 25/20 | 20 minutes, 5 times a week for 3 weeks, in addition to rehabilitation treatment | Walking overground; all participants practised gait for 15 sessions over 3 weeks (each session lasting 20 minutes) |

0 of 45 | ‐ | ‐ | Published information |

| Peurala 2009 | Not stated | Gait Trainer | 3 weeks | 42/14 | 20 minutes, 5 times a week for 3 weeks, in addition to rehabilitation treatment | Overground walking training; in the other control group, 1 or 2 physiotherapy sessions daily but not at the same intensity as in the other groups | 9 of 56 | 5 dropouts (2 situation worsened after 1 to 2 treatment days; 1 had 2 unsuccessful attempts in device; 1 had scheduling problems; 1 felt protocol too demanding) |

4 dropouts (1 felt protocol too demanding; 2 situation worsened after 1 to 2 treatment days; 1 death) |

Published information |

| Picelli 2016 | Not stated | G‐EO System Evolution | Experimental group (G‐EO) 30 minutes a day for 5 consecutive days | Not stated | 5 days in addition to botulinum toxin injection of calf muscles | None | 0 of 22 | ‐ | ‐ | Published information |

| Pohl 2007 | Mean Barthel Index, 37 points | Gait Trainer | 4 weeks | 124/31 | 20 minutes, 5 times a week | Physiotherapy every weekday for 4 weeks | 11 of 155 | 2 participants refused therapy, 1 increased cranial pressure, 1 relapsing pancreas tumour, 1 cardiovascular unstable |

4 participants refused therapy, 1 participant died, 1 myocardial infarction | Published information |

| Saltuari 2004 | Not stated | Lokomat | 2 weeks | 13/3 | A‐B‐A study: in phase A, 30 minutes, 5 days a week | Physiotherapy every weekday for 3 weeks (phase B) | 0 of 16 | None | None | Unpublished and published information provided by the authors. |

| Schwartz 2006 | Mean NIHSS, 11 points | Lokomat | 6 weeks | 49/67 | 30 minutes, 3 times a week | Physiotherapy with additional gait training 3 times a week for 6 weeks | 6 of 46 | 2 participants with leg wounds, 1 participant with recurrent stroke, 1 refused therapy |

1 participant with recurrent stroke, 1 with pulmonary embolism |

Unpublished and published information provided by the authors. |

| Stein 2014 | Not stated | Bionic leg device (AlterG) | 6 weeks | Not stated | 1 hour, 3 times a week for 6 weeks | Group exercises | 0 of 24 | ‐ | ‐ | Published information |

| Tanaka 2012 | Mean FIM, 79 points | Gait Master4 | 4 weeks | Not stated | 20 minutes, 2 or 3 times a week (12 sessions) | Non‐intervention (non‐training) | 0 of 12 | ‐ | ‐ | Published information |

| Tong 2006 | Mean Barthel Index, 51 points | Gait Trainer | 4 weeks | 39/11 | 20 minutes, 5 times a week | Conventional physiotherapy alone, based on Bobath concept | 4 of 50 | None | 2 participants discharged before study end, 1 participant readmitted to an acute ward, 1 participant deteriorating condition |

Published information |

| Ucar 2014 | Not stated | Lokomat | 2 weeks | Not stated | 30 minutes, 5 times a week | Conventional physiotherapy at home (focused on gait) | 0 of 22 | ‐ | ‐ | Published information |

| Van Nunen 2012 | Not stated | Lokomat | 8 weeks | Not stated | 30 minutes, twice a week | Overground therapy | 0 of 30 | ‐ | ‐ | Unpublished and published information provided by the author. |

| Waldman 2013 | Not stated | Portable rehab robot (ankle device) | 6 weeks | Not stated | 3 times a week, 18 sessions | Stretching the plantar flexors and active exercises for ankle mobility and strength | 0 of 24 | ‐ | ‐ | Published information |

| Watanabe 2014 | Not stated | Single‐leg version of the Hybrid Assistive Limb (HAL) | 4 weeks | 11/11 | 20 minutes, 12 sessions | Aimed to improve walking speed, endurance, balance, postural stability, and symmetry | 10 of 32 | 4 withdrew, 1 epilepsy, 1 technical reasons |

2 pneumonia, 2 discharged |

Published information |

| Werner 2002 | Mean Barthel Index, 38 points | Gait Trainer | 2 weeks | 13/12 | 20 minutes, 5 times a week | Gait therapy including treadmill training with body weight support | 0 of 30 | None | None | Published information |

| Westlake 2009 | Not stated | Lokomat | 4 weeks (12 sessions) | 8/8 | 30 minutes, 3 times a week | 12 physiotherapy sessions including manually guided gait training (3 times a week over 4 weeks) | 0 of 16 | None | None | Published information |

FIM: Functional Independence Measure NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

For one of the included studies published only as an abstract we obtained at least some results through correspondence with the trial co‐ordinator or principal investigator (Mayr 2008). Another study was not yet published, but the results of the trial were presented orally, and we were able to obtain a handout with information about the study from the principal investigator (Aschbacher 2006).

A detailed description of all participant characteristics can be found in Table 7 and Table 8 (see also the Characteristics of included studies). The mean age in the included studies ranged from 48 years, in Kyung 2008, to 76 years, in Watanabe 2014 (Table 7). More males than females were included the studies (approximately 60% males). More participants with ischaemic stroke than haemorrhagic stroke lesions (approximately 70% ischaemic stroke) were included, and almost as many participants with left‐sided hemiparesis compared with participants with right‐sided hemiparesis (approximately 50% left‐sided) were included in the studies (see Table 7 and Table 8).

Twelve studies provided information about baseline stroke severity (Table 8), of which seven used the Barthel Index score, ranging from 20 Barthel Index points, in Kim 2015, to 75 of 100 Barthel Index points, in Dias 2006 (Table 8). Details of all inclusion and exclusion criteria used in the studies can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table.

The duration of study intervention (time frame during which experimental interventions were applied) was heterogeneous, ranging from 10 days, in Chang 2012, to eight weeks, in Mayr 2008. The study intervention period for most studies was three or four weeks (Table 8). Fifteen of the 36 studies included participants who could walk independently at the start of the study; a further nine studies included participants who were dependent and independent walkers (Analysis 4.1); and 12 studies included only non‐ambulatory participants (Analysis 4.1). The experimental intervention in 17 studies was the robotic‐assisted device Lokomat, and the experimental intervention in nine studies was the electromechanical‐assisted device Gait Trainer; a detailed description of devices used in studies can be found in Table 8.

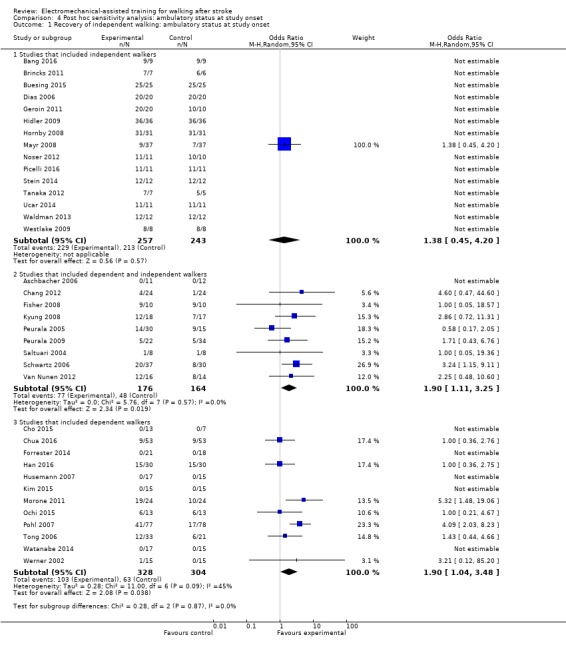

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Post hoc sensitivity analysis: ambulatory status at study onset, Outcome 1 Recovery of independent walking: ambulatory status at study onset.

Frequency (in terms of therapy provided per week) of treatment ranged from two or three times a week, in Tanaka 2012, to five times a week (Table 8). Intensity (in terms of duration of experimental therapy provided) of treatment ranged from 20 minutes, in Werner 2002, to 60 minutes, in Forrester 2014. In many studies, details of the interventions were unclear or incomplete, for example details about the intensity of the experimental treatment were unclear in some studies (Table 8). Except for Tanaka 2012 and Picelli 2016, the gait training time did not differ between control and experimental groups in the included studies. Eleven included studies used a follow‐up assessment after the study ended (Buesing 2015; Chua 2016; Dias 2006; Hidler 2009; Hornby 2008; Peurala 2005; Peurala 2009; Pohl 2007; Schwartz 2006; Stein 2014; Waldman 2013). Most studies investigated improvement in walking function as a primary outcome for analysis and used the Functional Ambulation Category (FAC) or comparable scales to assess independent walking. Furthermore, frequently investigated outcomes included assessment of walking function using gait velocity in metres per second. A more detailed description of the primary and secondary outcomes for each trial can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table.

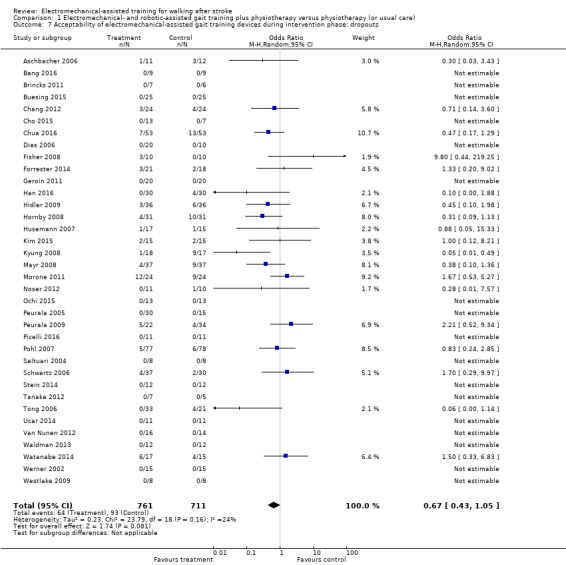

We found the highest dropout rates for all reasons at the end of the treatment phase to be 23%, in Hornby 2008, and 29%, in Kyung 2008. Seventeen trialists reported no dropouts at scheduled follow‐up (Analysis 1.7; Table 8).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy versus physiotherapy (or usual care), Outcome 7 Acceptability of electromechanical‐assisted gait training devices during intervention phase: dropouts.

Excluded studies

We excluded 24 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies and Figure 1 for further information).

Ongoing studies and studies awaiting assessment

We identified 16 ongoing studies (see Characteristics of ongoing studies). Thirteen studies for which we were unable to make contact with the trialists are still awaiting assessment (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

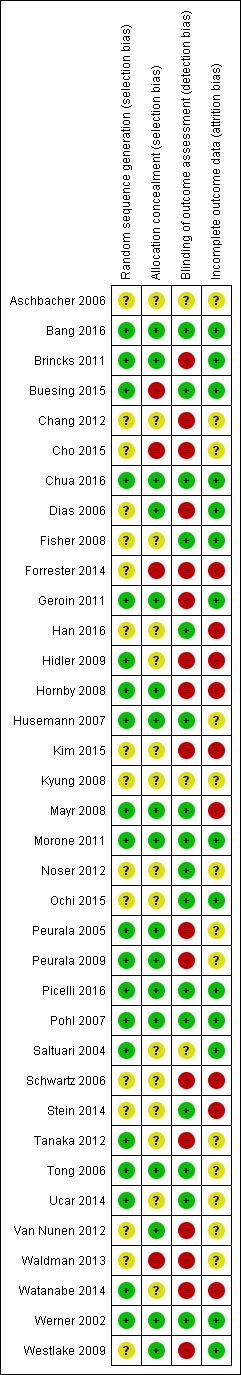

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in included studies is described in greater detail in Characteristics of included studies and Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

We wrote to the trialists of all included studies and studies awaiting assessment to request clarification of design features or for missing information to complete the quality ratings. We sent the correspondence via email or letter, followed by reminders every month if we received no response. Most trialists provided at least some of the requested data, but we were not able to obtain all of the required data.

Two review authors (JM, MP) used the 'Risk of bias' assessment tool to independently assess the methodological quality of the studies for the domains random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, and incomplete outcome data for all of the included trials except two (Pohl 2007; Werner 2002), which two other review authors (BE, JK) rated in an interview with the trialists. The review authors discussed all disagreements and sought arbitration by another review author (JK or BE) if necessary.

Allocation

Of the 36 included studies, 20 described adequate random sequence generation, and 17 described adequate allocation concealment.

Blinding

Of the 36 included studies, 6 reported blinding of the primary outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data

Of the 36 included studies, 14 reported incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting

For the majority of studies, particularly the older trials, we did not find study protocols. Where study protocols were available, there was no evidence of selective reporting of outcomes relevant to this review.

Other potential sources of bias

Five out of 36 included trials used a cross‐over design with random allocation to the order of treatment sequences (Brincks 2011; Cho 2015; Saltuari 2004; Tanaka 2012; Werner 2002). We analysed only the first intervention period as a parallel‐group trial in this review. All other included studies used a parallel‐group design with true randomisation to group allocation.

Three studies used two experimental groups and one control group (Geroin 2011; Peurala 2005; Tong 2006), and one study used one experimental group and two control groups (Peurala 2009). In the former three studies (Geroin 2011; Peurala 2005; Tong 2006), additional functional electrical stimulation of leg muscles (or transcranial stimulation of the brain in Geroin 2011) during gait training was applied in one of the treatment groups. Because functional electrical stimulation or transcranial stimulation of the brain was done as an adjunct during electromechanical‐assisted gait training, and because the results in these experimental groups did not differ significantly, we combined the results of both experimental groups into one (collapsed) group and compared this with the results from the control group. In one study, an electromechanical‐assisted device was used in the experimental group and was compared with two control groups that did not use a device (Peurala 2009). Because we were interested in the effects of electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait‐training devices for improving walking after stroke, we combined the results of both control groups without devices into one (collapsed control) group and compared this with results of the one experimental group.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

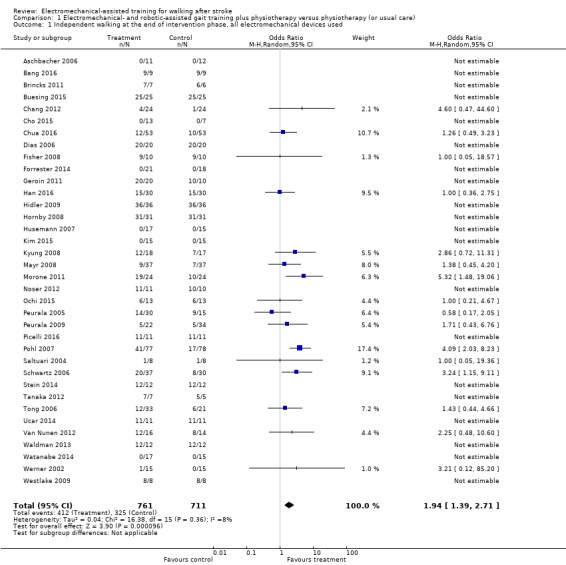

Independent walking at the end of the intervention phase, all electromechanical devices used

Thrity‐six trials with a total of 1472 participants measured independent walking at study end, but for 21 included trials, no effect estimate (odds ratio (OR)) was feasible because no events (e.g. no participant reached the ability to walk) or only events (e.g. all participants regained walking) were reported (Analysis 1.1) (Deeks 2011).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy versus physiotherapy (or usual care), Outcome 1 Independent walking at the end of intervention phase, all electromechanical devices used.

The use of electromechanical devices in gait rehabilitation for people after stroke increased the chance of walking independently (OR 1.94, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.39 to 2.71; P < 0.001; level of heterogeneity I² = 8%; moderate‐quality evidence; Table 1). However, 15 out of 36 studies investigated at least some participants who were already independent in walking at the start of the study. A further nine studies included participants who were dependent and independent walkers, and 12 studies included only non‐ambulatory participants (Analysis 4.1). Of the total population of 1472 participants, approximately 39% were independent and approximately 59% were dependent walkers at the start of the study.

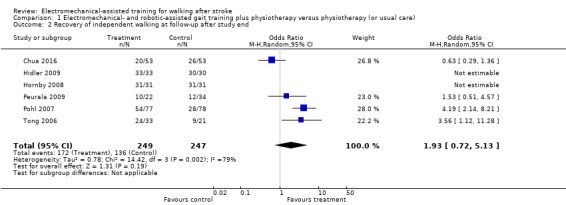

Recovery of independent walking at follow‐up after study end

Six trials with a total of 496 participants measured recovery of independent walking with follow‐up after the study end (Chua 2016; Hidler 2009; Hornby 2008; Peurala 2009; Pohl 2007; Tong 2006), but for two included trials (with 125 participants), no effect estimate (OR) was feasible because no events (e.g. no participant reached ability to walk) or only events (e.g. all participants regained walking) were reported (Analysis 1.2). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of people after stroke did not increase the chance of walking independently at follow‐up after study end (OR 1.93, 95% CI 0.72 to 5.13; P = 0.19; level of heterogeneity I² = 79%; moderate‐quality evidence). However, some included trials investigated participants who were already independent in walking at the start of the study. We could draw no definitive conclusion regarding a longer‐lasting effect of the use of electromechanical devices.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy versus physiotherapy (or usual care), Outcome 2 Recovery of independent walking at follow‐up after study end.

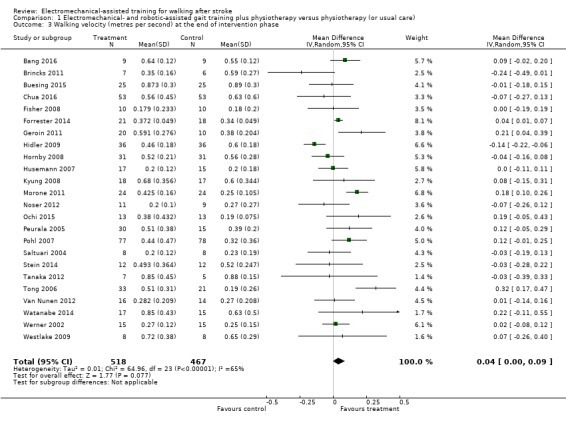

Walking velocity (metres per second) at the end of the intervention phase

Twenty‐four trials with a total of 985 participants provided data for walking velocity (m/s) at study end (Analysis 1.3). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation did not significantly increase walking velocity. The pooled mean difference (MD) (random‐effects model) for walking velocity was 0.04 m/s (95% CI 0.00 to 0.09; P = 0.08; level of heterogeneity I² = 65%; low‐quality evidence). Participants who were unable to walk were regarded as having a walking velocity of zero metres per second.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy versus physiotherapy (or usual care), Outcome 3 Walking velocity (metres per second) at the end of intervention phase.

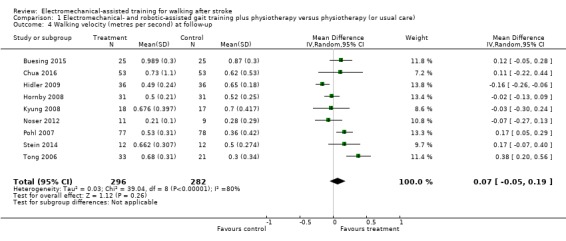

Walking velocity (metres per second) at follow‐up

Nine trials with a total of 578 participants provided data for walking velocity (m/s) at follow‐up after study end (Buesing 2015; Chua 2016; Hidler 2009; Hornby 2008; Kyung 2008; Noser 2012; Pohl 2007; Stein 2014; Tong 2006). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation did not significantly increase the walking velocity at follow‐up after study end. The pooled MD (random‐effects model) for walking velocity was 0.07 m/s (95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.19; P = 0.26; level of heterogeneity I² = 80%; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.4). Participants who were unable to walk were regarded as having a walking velocity of zero metres per second. We could draw no definitive conclusion regarding a longer‐lasting effect of the use of electromechanical devices for walking velocity.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy versus physiotherapy (or usual care), Outcome 4 Walking velocity (metres per second) at follow‐up.

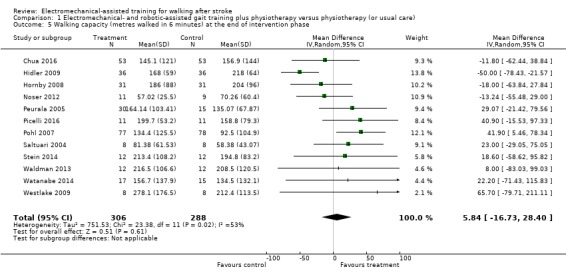

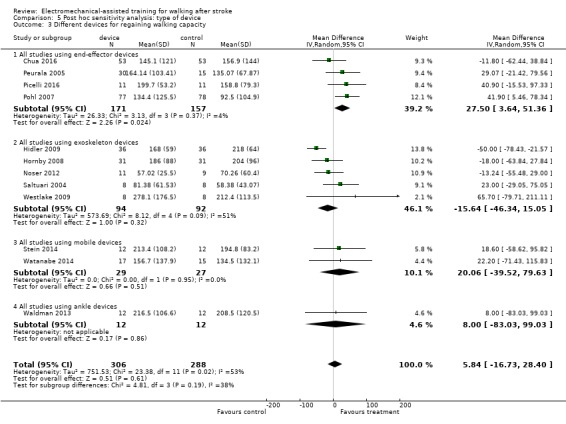

Walking capacity (metres walked in 6 minutes) at the end of the intervention phase

Twelve trials with a total of 594 participants provided data for walking capacity (metres walked in 6 minutes) at study end (Chua 2016; Hidler 2009; Hornby 2008; Noser 2012; Peurala 2005; Picelli 2016; Pohl 2007; Saltuari 2004; Stein 2014; Waldman 2013; Watanabe 2014; Westlake 2009). The use of electromechanical devices in gait rehabilitation did not increase the walking capacity of people after stroke. The pooled MD (random‐effects model) for walking capacity was 5.84 metres walked in 6 minutes (95% CI ‐16.73 to 28.40; P = 0.61; level of heterogeneity I² = 53%; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy versus physiotherapy (or usual care), Outcome 5 Walking capacity (metres walked in 6 minutes) at the end of intervention phase.

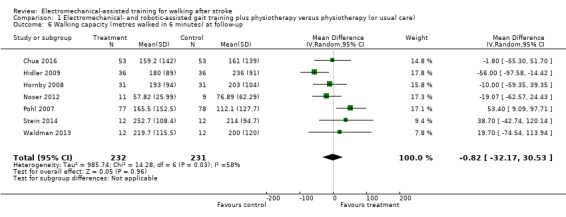

Walking capacity (metres walked in 6 minutes) at follow‐up

Seven trials with a total of 463 participants provided data for walking capacity (metres walked in 6 minutes) at follow‐up after study end (Chua 2016; Hidler 2009; Hornby 2008; Noser 2012; Pohl 2007; Stein 2014; Waldman 2013). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation did not increase walking capacity at follow‐up after study end. The pooled MD (random‐effects model) for walking capacity was ‐0.82 metres walked in 6 minutes (95% CI ‐32.17 to 30.53; P = 0.96; level of heterogeneity I² = 58%; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy versus physiotherapy (or usual care), Outcome 6 Walking capacity (metres walked in 6 minutes) at follow‐up.

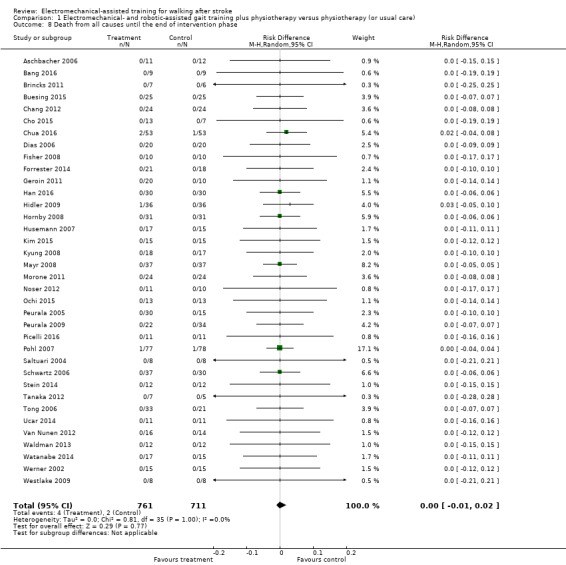

Death from all causes until the end of the intervention phase

Only three larger trials reported any deaths during the intervention period (Chua 2016; Hidler 2009; Pohl 2007). In Pohl 2007 one participant in the control group died as the result of aspiration pneumonia, and one participant in the treatment group died due to recurrent stroke. In Hidler 2009, the group in which the death occurred was not stated. We therefore used a worst‐case (conservative) scenario and counted the one death for the experimental group. In the study of Chua 2016 the deaths occurred after the treatment period. The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of non‐ambulatory people after stroke did not increase the risk of participants dying during the intervention period (risk difference (random‐effects model) 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.02; P = 0.77; level of heterogeneity I² = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Electromechanical‐ and robotic‐assisted gait training plus physiotherapy versus physiotherapy (or usual care), Outcome 8 Death from all causes until the end of intervention phase.

Adverse outcomes: acceptability of electromechanical‐assisted gait‐training devices during the intervention phase in terms of dropouts

All trialists provided information about participants who dropped out from all causes during the trial period, but for 17 of the 36 included trials, no events/dropouts were reported (Analysis 1.7). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of non‐ambulatory people after stroke did not increase the risk of participants dropping out (OR (random‐effects model) 0.67, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.05; P = 0.08; level of heterogeneity I² = 24%; low‐quality evidence). The reasons for dropouts and all adverse events are described in detail for each trial in Table 8.

Regaining independent walking ability: planned sensitivity analysis by trial methodology

To examine the robustness of the results, we specified variables in a sensitivity analysis that we believed could influence the size of the observed effect (adequate sequence generation process, adequate concealed allocation, blinded assessors for the primary outcome, incomplete outcome data, and excluding the largest study). As stated above, for some of the included trials, no effect estimate (OR) was feasible (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Planned sensitivity analysis by trial methodology, Outcome 1 Regaining independent walking ability.

Studies with adequate sequence generation process

We included 20 trials with a total of 949 participants with an adequate sequence generation process (Figure 2). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of people after stroke increased the chance of walking independently (OR (random‐effects model) 1.80, 95% CI 1.06 to 3.08; P = 0.03; level of heterogeneity I² = 38%).

Studies with adequate concealed allocation

We included 17 trials with a total of 831 participants with adequate concealed allocation (Figure 2). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of people after stroke increased the chance of walking independently (OR (random‐effects model) 1.87, 95% CI 1.12 to 3.12; P = 0.02; level of heterogeneity I² = 37%).

Studies with blinded assessors for the primary outcome

Sixteen trials with a total of 762 participants had blinded assessors for the primary outcome (Figure 2). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of people after stroke increased the chance of walking independently (OR (random‐effects model) 1.81, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.98; P = 0.02; level of heterogeneity I² = 31%).

Studies with complete outcome data

Fourteen trials with a total of 590 participants adequately described complete outcome data (Figure 2). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of people after stroke increased the chance of walking independently (OR (random‐effects model) 2.23, 95% CI 1.16 to 4.29; P = 0.02; level of heterogeneity I² = 29%).

Excluding the largest study (Pohl 2007)

After excluding the largest study (Pohl 2007), 35 trials with a total of 1317 participants remained in this analysis. The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of people after stroke increased the chance of walking independently (OR (random‐effects model) 1.65, 95% CI 1.17 to 2.34; P = 0.005; level of heterogeneity I² = 0%).

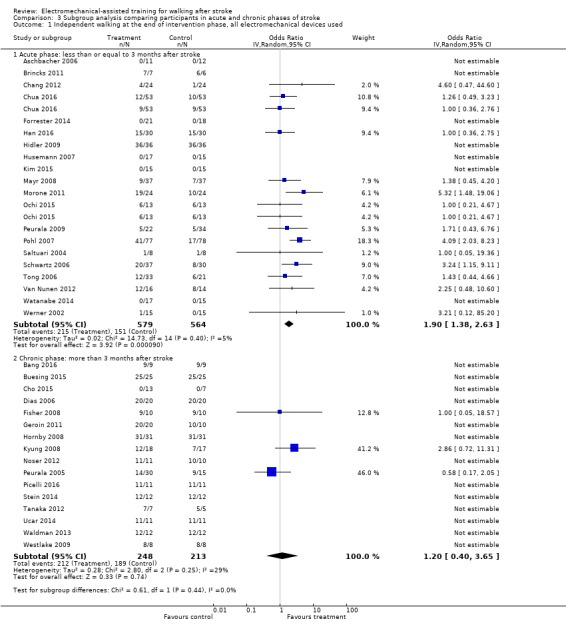

Subgroup analysis comparing participants in the acute and chronic phases of stroke

Independent walking at the end of the intervention phase, all electromechanical devices used

In our planned subgroup analysis comparing independent walking at the end of the intervention phase in people in the acute and chronic phases of stroke, we attempted to assign all included studies to one of two subgroups (acute and chronic phases).

Twenty trials with a total of 1143 participants investigated people in the acute or subacute phase, defined as less than or equal to three months after stroke (Analysis 3.1). As stated in the comparisons above, for some of the included trials no effect estimate (OR) was feasible (Analysis 3.1). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of people after stroke increased the chance of walking independently (OR (random‐effects model) 1.90, 95% CI 1.38 to 2.63; P < 0.001; level of heterogeneity I² = 5%).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis comparing participants in acute and chronic phases of stroke, Outcome 1 Independent walking at the end of intervention phase, all electromechanical devices used.

Sixteen trials with a total of 461 participants investigated people in the chronic phase, defined as more than three months after stroke (Analysis 3.1). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of people after stroke did not increase the chance of walking independently (OR (random‐effects model) 1.20, 95% CI 0.40 to 3.65; P = 0.74; level of heterogeneity I² = 29%).

In a formal subgroup analysis, we did not find statistically significant differences in regaining independent walking between participants treated in the acute/subacute phase compared with participants treated in the chronic phase after stroke (Chi² = 0.61, df = 1; P = 0.44).

Post hoc sensitivity analysis by ambulatory status at study onset

Independent walking at the end of the intervention phase

To examine the robustness of the results and to explore the relationship between the main effect and walking status at the start of the study, we compared independent walking rates at the end of the intervention phase by ambulatory status at start of study.

Ambulatory participants at start of study

Fifteen trials with a total of 500 participants investigated independent walkers (Analysis 4.1). As stated in the comparisons above, for some of the included trials, no effect estimate (OR) was feasible; the conclusions are therefore based on one trial. The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of people after stroke did not increase the chance of walking independently (OR (random‐effects model) 1.38, 95% CI 0.45 to 4.20; P = 0.57; level of heterogeneity I² = not applicable).

Ambulatory and non‐ambulatory participants at start of study

Nine trials with a total of 340 participants investigated a mixed population of dependent and independent walkers (Analysis 4.1). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of people after stroke increased the chance of walking independently (OR (random‐effects model) 1.90, 95% CI 1.11 to 3.25; P = 0.02; level of heterogeneity I² = 0%).

Non‐ambulatory participants at start of study

Twelve trials with a total of 632 participants investigated dependent walkers (Analysis 4.1). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of people after stroke increased the chance of walking independently (OR (random‐effects model) 1.90, 95% CI 1.04 to 3.48; P = 0.04; level of heterogeneity I² = 45%).

In a subgroup analysis, we did not find statistically significant differences between people who were dependent or independent walkers at the start of the study in regaining independent walking (Chi² = 0.28, df = 2; P = 0.87).

Walking speed at the end of the intervention phase

To examine the robustness of the results and to explore the relationship between walking velocity and ambulatory status at the start of the study, we compared achieved walking velocity at the end of the intervention phase by ambulatory status at the start of the study.

Ambulatory participants at start of study

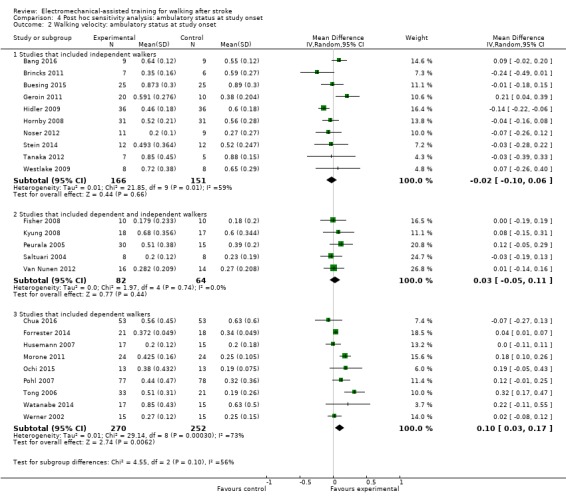

Ten trials with a total of 317 participants investigated independent walkers at the start of the study and provided data for walking velocity (m/s) at study end (Analysis 4.2). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation did not significantly increase walking velocity. The pooled MD (random‐effects model) for walking velocity was ‐0.02 m/s (95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.06; P = 0.66; level of heterogeneity I² = 59%).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Post hoc sensitivity analysis: ambulatory status at study onset, Outcome 2 Walking velocity: ambulatory status at study onset.

Ambulatory and non‐ambulatory participants at start of study

Five trials with a total of 146 participants investigated dependent and independent walkers at the start of the study and provided data for walking velocity (m/s) at study end (Analysis 4.2). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation did not significantly increase walking velocity. The pooled MD (random‐effects model) for walking velocity was 0.03 m/s (95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.11; P = 0.44; level of heterogeneity I² = 0%).

Non‐ambulatory participants at start of study

Nine trials with a total of 522 participants investigated dependent walkers at the start of the study and provided data for walking velocity (m/s) at study end (Analysis 4.2). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation significantly increased walking velocity. The pooled MD (random‐effects model) for walking velocity was 0.10 m/s (95% CI 0.03 to 0.17; P = 0.006; level of heterogeneity I² = 73%).

In a subgroup analysis, we did not find statistically significant differences in regaining independent walking between participants who were dependent or independent walkers at the start of the study (Chi² = 4.55, df = 2; P = 0.10).

Post hoc sensitivity analysis by type of electromechanical device

Independent walking at the end of the intervention phase

To examine the robustness of the results and to explore the relationship between independent walking and type of electromechanical device, we compared achieved independent walking rates at the end of the intervention phase by type of electromechanical device.

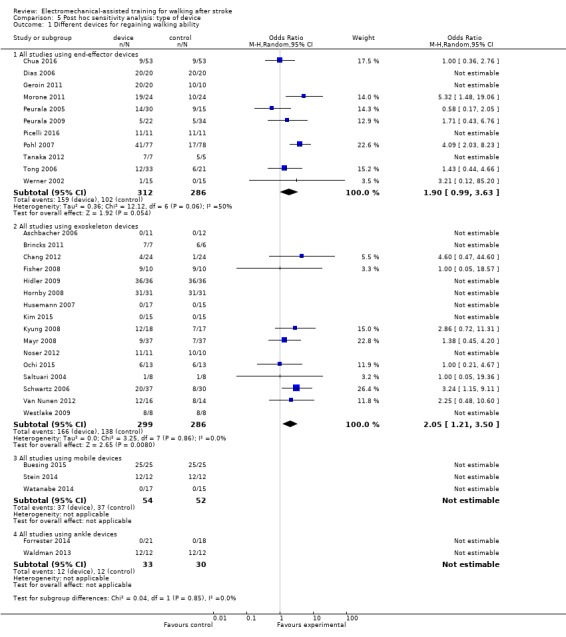

End‐effector devices

Eleven trials with a total of 598 participants used an end‐effector device as the experimental intervention (Table 8). As stated in the comparisons above, for some of the included trials, no effect estimate (OR) was feasible (Analysis 5.1). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of people after stroke did not increase the chance of walking independently (OR (random‐effects model) 1.90, 95% CI 0.99 to 3.63; P = 0.05; level of heterogeneity I² = 50%).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Post hoc sensitivity analysis: type of device, Outcome 1 Different devices for regaining walking ability.

Exoskeleton devices

Sixteen trials with a total of 585 participants used an exoskeleton device as the experimental intervention (Table 8). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation of people after stroke increased the chance of walking independently (OR (random‐effects model) 2.05, 95% CI 1.21 to 3.50; P = 0.008; level of heterogeneity I² = 0%).

We did not find statistically significant differences in regaining independent walking between participants treated with end‐effector or exoskeleton devices (Chi² = 0.04, df = 1; P = 0.85).

Mobile devices

Three trials with a total of 106 participants used powered mobile devices as the experimental intervention (Table 8), but the effects on walking ability were not estimable.

Ankle devices

Two trials with a total of 63 participants used ankle devices while sitting as the experimental intervention (Table 8), but the effects on walking ability were not estimable.

We did not find statistically significant differences in regaining independent walking by type of electromechanical device (end‐effector, exoskeleton, mobile or ankle device)(Chi² = 0.04, df = 1; P = 0.85).

Walking speed at the end of the intervention phase

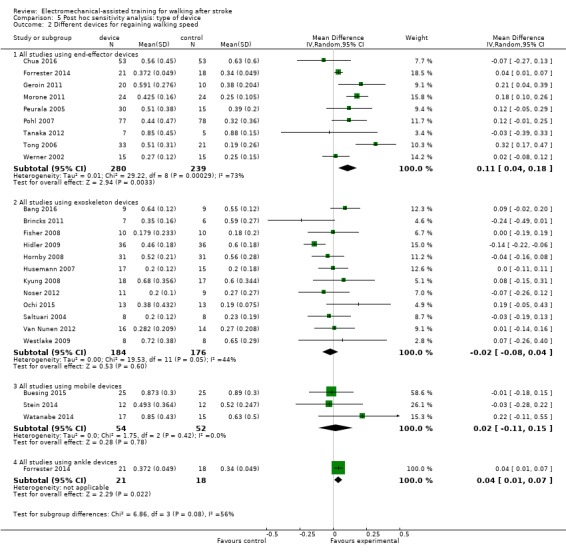

To examine the robustness of the results and to explore the relationship between independent walking and type of electromechanical device, we compared the walking speed at the end of the intervention phase by type of electromechanical device.

End‐effector devices

Nine trials with a total of 519 participants used an end‐effector device as the experimental intervention and provided data for walking velocity (m/s) at study end (Analysis 5.2). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation significantly increased walking velocity. The pooled MD (random‐effects model) for walking velocity was 0.11 m/s (95% CI 0.04 to 0.18; P = 0.003; level of heterogeneity I² = 73%).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Post hoc sensitivity analysis: type of device, Outcome 2 Different devices for regaining walking speed.

Exoskeleton devices

Twelve trials with a total of 360 participants used an exoskeleton device as the experimental intervention and provided data for walking velocity (m/s) at study end (Analysis 5.2). The use of electromechanical devices for gait rehabilitation did not increase walking velocity. The pooled MD (random‐effects model) for walking velocity was ‐0.02 m/s (95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.04; P = 0.60; level of heterogeneity I² = 44%).

In a formal subgroup analysis, we found statistically significant differences in improvement in walking velocity between participants treated with an end‐effector device or an exoskeleton device (Chi² = 6.79, df = 1; P = 0.009; I² = 85.3%).

Mobile devices