Abstract

Background

Many people with schizophrenia do not achieve a satisfactory treatment response with their initial antipsychotic drug treatment. Sometimes a second antipsychotic, in combination with the first, is used in these situations.

Objectives

To examine whether:

1. treatment with antipsychotic combinations is effective for schizophrenia; and 2. treatment with antipsychotic combinations is safe for the same illness.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's register which is based on regular searches of CINAHL, BIOSIS, AMED, Embase, PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and registries of clinical trials. There are no language, time, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records in the register. We ran searches in September 2010, August 2012 and January 2016. We checked for additional trials in the reference lists of included trials.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials comparing antipsychotic combinations with antipsychotic monotherapy for the treatment of schizophrenia and/or schizophrenia‐like psychoses.

Data collection and analysis

We independently extracted data from the included studies. We analysed dichotomous data using risk ratios (RR) and the 95% confidence intervals (CI). We analysed continuous data using mean difference (MD) with a 95% CIs. For the meta‐analysis we used a random‐effects model. We used GRADE to complete a 'Summary of findings' table and assessed risk of bias for included studies.

Main results

Sixty‐two studies are included in the review, 31 of these compared clozapine monotherapy with clozapine combination. We considered the risk of bias in the included studies to be moderate to high. The majority of trials had unclear allocation concealment, method of randomisation and blinding, and were not free of selective reporting.

There is some limited evidence that combination therapy may be superior to monotherapy in reducing the risk of no clinical response (RR 0.73 CI 0.64 to 0.83; participants = 2398; studies = 29; very low‐quality evidence), subgroup analyses show that the positive result was due to the studies with clozapine in both the monotherapy and combination groups (RR 0.66 CI 0.53 to 0.83; participants = 1127; studies = 17) and typical in both groups (RR 0.64 CI 0.49 to 0.84; participants = 597; studies = 5). The subgroup with atypical antipsychotics in both groups did not showed a difference between the two interventions (RR 0.95 CI 0.83 to 1.09; participants = 674; studies = 7). Three studies provided data regarding relapse, the pooled data showed high heterogeneity (I² = 82%) and therefore the results were not pooled. Two studies showed no difference between the interventions and one study showed that antipsychotics combination might decrease the risk of relapse. A combination of antipsychotics was not superior or inferior to antipsychotic monotherapy in reducing the number of participants discontinuing treatment early (RR 0.90 CI 0.76 to 1.07; participants = 3137; studies = 43, low‐quality evidence). No difference was found between treatment groups in the number of participants hospitalised (RR 0.96 CI 0.36 to 2.55; participants = 202; studies = 3, very low‐quality evidence). We did not find evidence of a difference between treatment groups in serious adverse events or those requiring discontinuation (RR 1.05 CI 0.65 to 1.69; participants = 2398; studies = 30, very low‐quality evidence). There is a lack of evidence on clinically important change in quality of life, with only four studies reporting average endpoint or change data for this outcome on three different scales, none of which showed a difference between treatment groups.

Authors' conclusions

Currently, most evidence regarding the use of antipsychotic combinations comes from short‐term trials, limiting the assessment of long‐term efficacy and safety. We found very low‐quality evidence that a combination of antipsychotics may improve the clinical response. We also found very low‐quality evidence that a combination of antipsychotics may make no difference at preventing participants from leaving the study early, preventing relapse and/or causing more serious adverse events than monotherapy.

Plain language summary

Combining antipsychotic medication for the treatment of schizophrenia

Background

Antipsychotic medication was introduced in the 1950s to reduce or alleviate the symptoms of schizophrenia, such as the psychotic states of hearing voices, visual hallucinations and strange thoughts such as paranoia (feeling singled‐out or put upon by others). Medication for mental illness also helped to establish care in the community, because people could take medication in their homes or by regularly visiting the hospital. But this also led to new issues such as the effectiveness of different medication (taken alone or in combination) and compliance (the willingness of service users to take their medication without being supervised).

The range of antipsychotic medication available is wide and their effectiveness can also vary from individual to individual. In addition, not all patients fully respond to a single antipsychotic, and in these situations, a combination of antipsychotics are often prescribed. The evidence for the benefits of taking one or more antipsychotics in combination is often unclear. There are also differing profiles of typical (first generation) and atypical (second generation) antipsychotics adding to a confusing array of terminology and dilemma of what is the best medication for service users.

Searches

This review investigates the effects of different antipsychotic combinations compared with single antipsychotics for people with schizophrenia. Searches for randomised controlled trials have now been run by the Information Specialist of the Cochrane Schizophenia Group in 2010, 2012 and 2016. Sixty‐two trials, reporting useable data, are included in the review.

Main results

The review of available evidence found that combinations of antipsychotics may be more effective in treating symptoms of schizophrenia compared with taking one antipsychotic. In particular, combination treatments that included clozapine and typical antipsychotic in both groups were found to be effective. Few studies reported on this central issue of relapse rates (service users becoming unwell again), but this was because most of the studies were of short length (whereas schizophrenia is a long‐term health problem that requires studies of an equally long duration). No real differences were found between combinations of antipsychotics and single antipsychotics for preventing relapse and roughly equal numbers of people discontinued their treatment. There was also no difference between combination therapy and monotherapy regarding hospital admission and/or occurrence of serious adverse events. Numbers leaving the studies early were similar. Clinically meaningful data for quality of life were not reported.

Conclusions

These results show that there may be some clinical benefit for combination therapy in that more people receiving a combination of antipsychotic showed an improvement in symptoms. For other important outcomes such as relapse, hospitalisation, adverse events, discontinuing treatment or leaving the study early, no clear differences between the two treatment options were observed. However, these results are based on very low or low‐quality evidence and more research providing high‐quality evidence is needed before firm conclusions can be made.

This plain language summary has been adapted from an original summary by Benjamin Gray, Service User and Service User Expert, Rethink Mental Illness. Email: ben.gray@rethink.org

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Combinations of antipsychotic drugs compared to single antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia.

| Combinations of antipsychotic drugs compared to single antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: schizophrenia or related disorders Setting: outpatients and inpatients Intervention: combinations of antipsychotic drugs Comparison: single antipsychotic drugs | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with single antipsychotic drugs | Risk with combinations of antipsychotic drugs | |||||

| Clinical response: No clinically important response ‐ as defined by each of the studies follow up: range 4 weeks to 52 weeks |

Study population | RR 0.73 (0.64 to 0.83) | 2398 (29 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 4 | ||

| 512 per 1,000 | 374 per 1,000 (328 to 425) | |||||

| Relapse ‐ as defined by each of the studies follow up: range 2 months to 36 | Study population | ‐ | 512 (3 RCTs) | ‐ | Data were not pooled due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 82%). Two studies showed no difference between the interventions and one study favoured antipsychotic combinations. | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Leaving the study early follow up: range 6 weeks to 52 weeks | Study population | RR 0.90 (0.76 to 1.07) | 3137 (43 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 5 7 | ||

| 183 per 1,000 | 164 per 1,000 (139 to 195) | |||||

| Service utilisation: Hospital admission follow up: range 12 weeks to 26 weeks | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.36 to 2.55) | 202 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 5 6 | ||

| 69 per 1,000 | 67 per 1,000 (25 to 177) | |||||

| Service utilisation: Change in hospital status ‐ not reported | Study population | not estimable | ( studies) | ‐ | No studies provided data for this outcome. | |

| 0 per 1,000 | 0 per 1,000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Adverse events: Serious event or requiring discontinuation follow up: range 6 weeks to 8 months | Study population | RR 1.05 (0.65 to 1.69) | 2398 (30 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 5 7 | ||

| 47 per 1,000 | 49 per 1,000 (31 to 80) | |||||

| Quality of life assessed with: QLS, SWN and SF‐36 follow up: range 6 weeks to 16 | see comment | see comment | ‐ | 398 (4 RCTs) | ‐ | Data were not pooled, as they were presented in both change and endpoint data for 3 different scales. None of the scales showed a difference between the two groups. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level due to risk of bias.

2 Downgraded one level due to inconsistency.

3 Although there is a concern about the timeframe to measure the outcome we decided not to downgrade due to overall quality assessment.

4 Downgraded one level due to publication bias.

5 Downgraded one level due to imprecision.

6 Downgraded one level due to indirectness.

7 Although there is a concern about the influence on industry we decided not to downgrade due to overall quality assessment.

8 Downgraded two levels due to inconsistency.

Please see Checklist to aid consistency and reproducibility of GRADE assessments Appendix 1.

Background

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia is a chronic disorder with a lifetime prevalence of four per 1000 persons (McGrath 2008). It is characterised by emotional, cognitive, and behavioural dysfunctions. In order to meet the diagnostic criteria of schizophrenia, patients require two or more positive, disorganised, or negative symptoms that persist for at least six months, with at least one of them being a positive symptom or disorganised speech (APA 2013). Positive symptoms include delusions (e.g. a false belief that is resistant to change, immune to contradictory evidence, and without correlation to the sociocultural background) and hallucinations (e.g. a sensory experience in the absence of external stimulus to the corresponding sensory organ). Negative symptoms are characterised by deficits in normal behaviour, which consist of five domains: blunted affect, alogia, asociality, anhedonia, and avolition (Kirkpatrick 2006).

Schizophrenia is difficult to treat and significantly burdens an individual's daily life. Despite the introduction of antipsychotics in the 1950s and the reintroduction of clozapine to the Western world, the mean recovery rate of schizophrenia is 13.5% (Jääskeläinen 2012). In clinical practice, multiple augmentation strategies such as adding another antipsychotic, mood‐stabiliser, benzodiazepines, lithium, electroconvulsive therapy, or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation have been used for these patients in order to improve their clinical state, but the evidence for the use of these interventions is lacking (Hasan 2012).

Description of the intervention

Antipsychotic medications are the cornerstone for the treatment of schizophrenia. They were originally classified on the basis of their risk for the development of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) as typical (e.g. chlorpromazine, haloperidol, fluphenazine) or atypical (e.g. clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone) if the risk for the development of EPS is low (Grunder 2009).

Antipsychotic polypharmacy/combination treatment, e.g. concurrent treatment with more than one antipsychotic medication, is a common strategy for the management of disturbed behaviour, poor response to antipsychotic monotherapy, or acute positive symptom exacerbation (Paton 2008). Concerning this practice, recommendations are varied. While some countries justify this practice (e.g. Finland, France, the UK), others recommend against it (e.g. Canada, Denmark, Spain), and many abstain from making any recommendation (Gaebel 2005). Regardless of the recommendations and lack of evidence, this practice has shown a trend towards increased use over time (Gangluy 2004). It is estimated that 19.6% of patients with schizophrenia across the world receive antipsychotic polypharmacy/combination treatment (Gallego 2009).

How the intervention might work

Currently, there is not a current understanding of how the combination of antipsychotics might work. Plausible hypotheses include (Freudenreich 2002):

achieving optimal receptor occupancy;

targeting different receptors with the added drug (Kapur 2001); and

reducing the dose‐related side‐effects by using lower doses of the two drugs.

Why it is important to do this review

A number of potential concerns regarding antipsychotic combinations have been identified. These include the possibility of unnecessarily high doses, an increased acute and/or chronic side‐effect burden, adverse pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic interactions, increased rates of non‐compliance, difficulties in determining cause and effect of multiple treatments, potential increased mortality, higher costs and poorly documented risks and benefits of this practice (Centorrino 2005; Meltzer 2000; Misawa 2011; Rupnow 2007; Waddington 1998; Weiden 1999). In this review, we examine the evidence for the efficacy and safety of antipsychotic combinations in the treatment of schizophrenia and schizophrenia‐like psychoses. We are aware of the sister Cochrane review investigating the effects of different clozapine‐antipsychotic combinations (Barber 2017). However, this review is different in its scope as it investigates any combinations of antipsychotic therapy versus any antipsychotic monotherapy.

Objectives

To examine whether:

treatment with antipsychotic combinations is effective for schizophrenia; and

treatment with antipsychotic combinations is safe for the same illness.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs. Where a trial was described as 'double‐blind' and it implied that the study was randomised and the demographic details of each group were similar, those trials were also included. After debate we decided to maintain the same inclusion criteria determined by previous authors to include quasi‐RCTs (see Differences between protocol and review).

Types of participants

Adults, however defined, with schizophrenia or related disorders, including schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder and delusional disorder, again, by any means of diagnosis.

Types of interventions

1. Treatment with more than one antipsychotic medication

Any dose and route of administration.

2. Treatment with only one antipsychotic medication

Any dose and route of administration.

Types of outcome measures

We grouped outcomes into long term (over 26 weeks, A), medium term (13 to 26 weeks, B) and short term (up to 12 weeks, C).

Primary outcomes

1. Clinical response

1.1 No clinically important response ‐ as defined by each of the studies

1.2 Relapse ‐ as defined by each of the studies

2. Leaving the study early

Secondary outcomes

1. Service utilisation

1.1 Hospital admission 1.2 Days in hospital 1.3 Change in hospital status

2. Clinical response

2.1 No clinically important improvement of global state 2.2 Average score/change in global state 2.3 No clinically important improvement in mental state ‐ as defined by each of the studies 2.4 Average score/change in mental state 2.5 No clinically important response on positive symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 2.6 Average score/change in positive symptoms 2.7 No clinically important response on negative symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 2.8 Average score/change in negative symptoms 2.9 No clinically important response on aggression/agitation symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 2.10 Average score/change in aggression/agitation symptoms

3. Behaviour

3.1 General behaviour 3.2 Specific behaviours 3.2.1 Social functioning 3.2.2 Employment status during trial (employed / unemployed) 3.2.3 Occurrence of violent incidents (to self, others, or property) 3.2.4 Level of substance abuse

4. Adverse events

4.1 Serious adverse events 4.2 Adverse events requiring hospitalisation 4.3 Specific adverse events 4.3.1 Allergic reactions 4.3.2 Blood dyscrasia such as agranulocytosis 4.3.3 Central nervous system (ataxia, nystagmus, drowsiness, fits, diplopia, tremor) 4.3.4 Death (suicide and non‐suicide deaths) 4.3.5 Endocrinological dysfunction (hyperprolactinaemia) 4.3.6 Weight gain 4.3.7 Movement disorders (extrapyramidal side effects (EPS))

5. Quality of life

6. Economic burden (cost of care)

'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2011), and used GRADE profiler (GRADEPRO) to import data from RevMan 5 (Review Manager) in order to create a 'Summary of findings' table. This table provides outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important to patient care and decision‐making. Also, we prepared an appendix (Appendix 1) to help with the standardisation of the 'Summary of findings' table (please see Differences between protocol and review). We aimed to select the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' table.

1. Clinical response

1.1 No clinically important response ‐ as defined by each of the studies

1.2 Relapse ‐ as defined by each of the studies

2. Leaving the study early

3. Service utilisation

3.1 Hospital admission 3.2 Change in hospital status

4. Adverse events: clinically important ‐ as defined by individual studies*

5. Quality of life: clinically important response ‐ as defined by individual studies*

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register

The Information Specialist searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Study‐Based Register of Trials (June 2010, August 2012 and 25 January, 2016) using the following search strategy, which has been developed based on literature review and consulting with the authors of the review:

(((antipsychot* or neuroleptic* or drug*) and combin*) or *add‐on* or *addition*or *supplement*or *supplementation*or *cotreatment*or *co‐treatment*or *adjunctive* or *concurrent* or *concomitant* or *simultaneous* or *parallel* or *polypharmacy) in title, abstract or index terms of REFERENCE or (*polytherapy* or *augmentation* or *parallel* or *combined*) in interventions of STUDY

In such a study‐based register, searching the major concept retrieves all the synonym keywords and relevant studies because all the studies have already been organised based on their interventions and linked to the relevant topics.

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Register of Trials is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (including AMED, BIOSIS, CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and registries of clinical trials) and their monthly updates, handsearches, grey literature, and conference proceedings (see Group’s Module). There is no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected references of all included studies for further relevant studies.

2. Personal contact

Where necessary, we contacted the first author of each included study for information regarding unpublished trials. We noted the outcome of this contact in the Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification tables.

Data collection and analysis

The text below describes data collection and analysis for the 2016 search; the previous data collection and analysis can be seen in Appendix 2.

Selection of studies

Two review authors JO and SC inspected all abstracts of studies identified as above and identified potentially relevant reports. YH screened the Chinese language studies, and one study in Korean language was inspected by HH. We resolved disagreements by discussion, or where there was still doubt, we acquired the full‐text article for further inspection. We acquired the full‐text articles of relevant reports/abstracts meeting initial criteria for reassessment and carefully inspected for a final decision on inclusion (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). JO and SC were not blinded to the names of the authors, institutions or journal of publication. Where difficulties or disputes arose, we asked author LC for help, and where it was impossible to decide or if adequate information was not available to make a decision, we added these studies to those awaiting assessment and contacted the authors of the papers for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

Review authors JO and SC independently extracted data from all included studies and YH extracted data for Chinese studies. In addition, to ensure reliability, LC extracted data from a random sample of these studies, comprising 10% of the total. Again, we discussed any disagreement and documented decisions. With any remaining problems, LC helped clarify issues and we documented these final decisions. We extracted data presented only in graphs and figures whenever possible, but included only if two review authors independently had the same result. We attempted to contact authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain missing information or for clarification whenever necessary. If studies were multi‐centre, where possible, we extracted data relevant to each component centre separately.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We adapted the 'Data collection form for intervention reviews' provided by Cochrane to collect data.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if: a) the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument have been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and b) the measuring instrument has not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial. Ideally, the measuring instrument should either be: i. a self‐report or ii. completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly, therefore we noted in Description of studies if this was the case or not.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint), which can be difficult in unstable and difficult to measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided primarily to use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were not available. We did not combined endpoint data and change data, we decided to present the data in the analysis separately (see Differences between protocol and review).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we applied the following standards to relevant data before inclusion.

Please note, we entered data from studies of at least 200 participants in the analysis irrespective of the following rules, because skewed data pose less of a problem in large studies. We also entered all relevant change data, as when continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not.

For endpoint data:

(a) when a scale started from the finite number zero, we subtracted the lowest possible value from the mean, and divided this by the standard deviation (SD). If this value was lower than 1, it strongly suggests a skew and we excluded these data. If this ratio was higher than one but below 2, there is suggestion of skew. We entered these data and tested whether their inclusion or exclusion changed the results substantially. Finally, if the ratio was larger than 2 we included these data, because skew is less likely (Altman 1996; Higgins 2011).

(b) if a scale starts from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), (Kay 1986)) which can have values from 30 to 210), we modified the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2 SD > (S‐S min), where S is the mean score and 'S min' is the minimum score.

2.5 Common measure

Where relevant, to facilitate comparison between trials, we converted variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, we converted continuous outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962), or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), this can be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005; Leucht 2005a). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for treatment with antipsychotic combinations. Where keeping to this made it impossible to avoid outcome titles with clumsy double‐negatives (e.g. 'Not un‐improved'), we presented data where the left of the line indicates an unfavourable outcome and noted this in the relevant graphs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Review authors, JO and SC independently assessed the risk of bias of each trial published in English and YH assessed trials published in Chinese by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to assess trial quality (Higgins 2011a). This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

If the raters disagreed, we made the final rating by consensus, with the involvement of LC. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. If non‐concurrence occurred, we reported this.

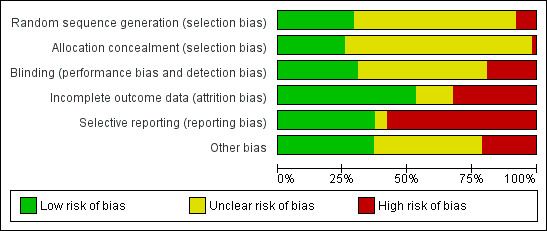

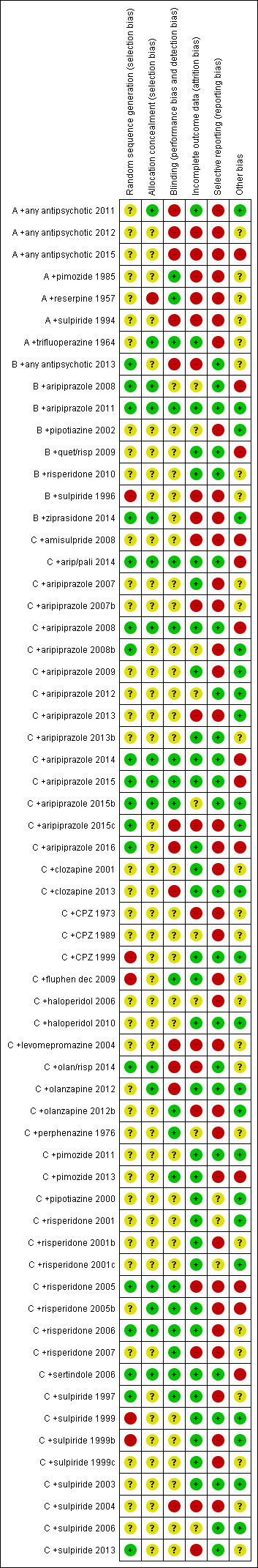

We noted the level of risk of bias in the text of the review and in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Table 1.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes, we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000).

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes, we estimated mean difference (MD) between groups. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (standardised mean difference (SMD)). However, if scales of very considerable similarity were used, we presumed there was a small difference in measurement, and calculated the effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice), but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992), whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we presented such data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjust for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (Bm) and the ICC [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC is not reported it will be assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies have been appropriately analysed taking into account ICCs and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would be possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, we only used data from the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. If data were binary, we simply added and combined within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous, we combined data following the formula in section 7.7.3.8 (Combining groups) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We did not use data where the additional treatment arms were not relevant.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). We chose that, for any particular outcome, should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for, we would not reproduce these data or use them within analyses. If, however, more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we addressed this within the 'Summary of findings' table by down‐rating quality. We also downgraded quality within the 'Summary of findings' table should loss be 25% to 50% in total.

2. Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50% and where these data were not clearly described, we presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis). We assumed all those leaving the study early to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed ‐except for the outcomes of death and adverse effects‐ for these outcomes we used the rate of those who stayed in the study (in that particular arm of the trial) for those who did not. We undertook a sensitivity analysis to test how prone the primary outcomes were to change by comparing data only from people who completed the study to that point to the ITT analysis using the above assumptions.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

We reported and used data where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50%, and data only from people who completed the study to that point were reported.

3.2 Standard deviations

If standard deviations (SDs) were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and confidence intervals available for group means, and either P value or T value available for differences in mean, we calculated them according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011). When only the SE is reported, SDs) are calculated by the formula SD = SE * square root (N). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011) present detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P values, t or F values, confidence intervals, ranges or other statistics. If these formulae did not apply, we calculated the SDs according to a validated imputation method, which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information. We nevertheless examined the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

3.3 Assumptions about participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up

Various methods are available to account for participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up. Some trials just present the results of study completers, others use the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF), while more recently methods such as multiple imputation or mixed‐effects models for repeated measurements (MMRM) have become more of a standard. While the latter methods seem to be somewhat better than LOCF (Leon 2006), we feel that the high percentage of participants leaving the studies early and differences in the reasons for leaving the studies early between groups is often the core problem in randomised schizophrenia trials. We therefore did not exclude studies based on the statistical approach used. However, we preferred to use the more sophisticated approaches. (e.g. MMRM or multiple‐imputation) and only presented completer analyses if some kind of ITT data were not available at all. Moreover, we addressed this issue in the item "incomplete outcome data" of the 'Risk of bias' tool.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations which we had not predicted would arise and discussed in the text if they arose.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods which we had not predicted would arise and discussed in the text if they arose.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I² statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I² method alongside the Chi² P value. The I² provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I² depends on i. magnitude and direction of effects and ii. strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from Chi² test, or a confidence interval for I²). An I² estimate greater than or equal to around 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi² statistic, can be interpreted as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Section 9.5.2 ‐ Deeks 2011). We explored and discussed in the text potential reasons for substantial levels of heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Section 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there are 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In future versions of this review, if funnel plots are possible, we will seek statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. There is, however, a disadvantage to the random‐effects model. It puts added weight onto small studies which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We chose random‐effects model for all analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses

We presented data in the analyses grouped by the type of antipsychotic used: trials with clozapine in both the monotherapy and combination arm, trials with other atypical drugs in both the monotherapy and combination arms, trials with typical antipsychotic drugs in both arms, or any antipsychotics in both groups, in order to facilitate subgroup analyses (see Differences between protocol and review).

1.1 Primary outcomes

In addition, we also undertook subgroup analyses comparing the results for the following:

enrolment of acutely exacerbated or chronically ill patients;

treatment duration <12 weeks vs ≥12 weeks;

clozapine vs non‐clozapine combinations; and

drug added to clozapine treatment.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

If inconsistency was high first, we investigated whether data were entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, we visually inspected the graph and successively removed outlying studies to see if homogeneity was restored. For this review, we decided that should this occur with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than around 10% of the total weighting, we would present data. If not, we would not pool such data but discuss issues. We know of no supporting research for this 10% cut‐off but are investigating use of prediction intervals as an alternative to this unsatisfactory state.

We performed a meta‐regression for the primary outcome 'No clinically important response' (Please see Differences between protocol and review).

When unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity were obvious, we simply discussed these. We did not undertake sensitivity analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

1. Implication of randomisation

If trials were described in some way as to imply randomisation, we undertook a sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes. We included these studies in the analyses and if there was no substantive difference when the implied randomised studies were added to those with better description of randomisation, then we used relevant data from these studies.

2. Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumption compared with completer data only. If there was a substantial difference, we reported and discussed these results, but continued to employ our assumption.

Where assumptions had to be made regarding missing SDs data (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumption compared with completer data only. We undertook a sensitivity analysis to test how prone results were to change when 'completer' data only were compared to the imputed data using the above assumption. If there was a substantial difference, we reported and discussed these results, but continued to employ our assumption.

3. Risk of bias

We analysed the effects of excluding trials that we judged to be at high risk of bias across one or more of the domains of randomisation (implied as randomised with no further details available) allocation concealment, blinding and outcome reporting for the meta‐analysis of the primary outcome. If the exclusion of trials at high risk of bias did not substantially alter the direction of effect or the precision of the effect estimates, we included data from these trials in the analysis

4. Imputed values

We undertook a sensitivity analysis to assess the effects of including data from trials where we used imputed values for ICCs in calculating the design effect in cluster‐randomised trials.

If we found substantial differences in the direction or precision of effect estimates in any of the sensitivity analyses listed above, we did not pool data from the excluded trials with the other trials contributing to the outcome, but presented them separately

5. Fixed and random effects

We synthesised data using a random‐effects model, however, we also synthesised data for the primary outcome using a fixed‐effect model to evaluate whether this altered the significance of the results

Results

Description of studies

Please also see Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification, and Characteristics of ongoing studies. To try and aid clarity, we have named the studies in an unusual manner. The study tag starts with the duration category (A = long term (over 26 weeks); B = medium term (13 to 26 weeks) and C = short term (up to 12 weeks); the remainder of the tag is the additional drug in the combination antipsychotic group (chlorpromazine has to be shortened to 'CPZ'). Finally, if two studies had similar names an alphabetical tag ( ‐ b, ‐ c) was added.

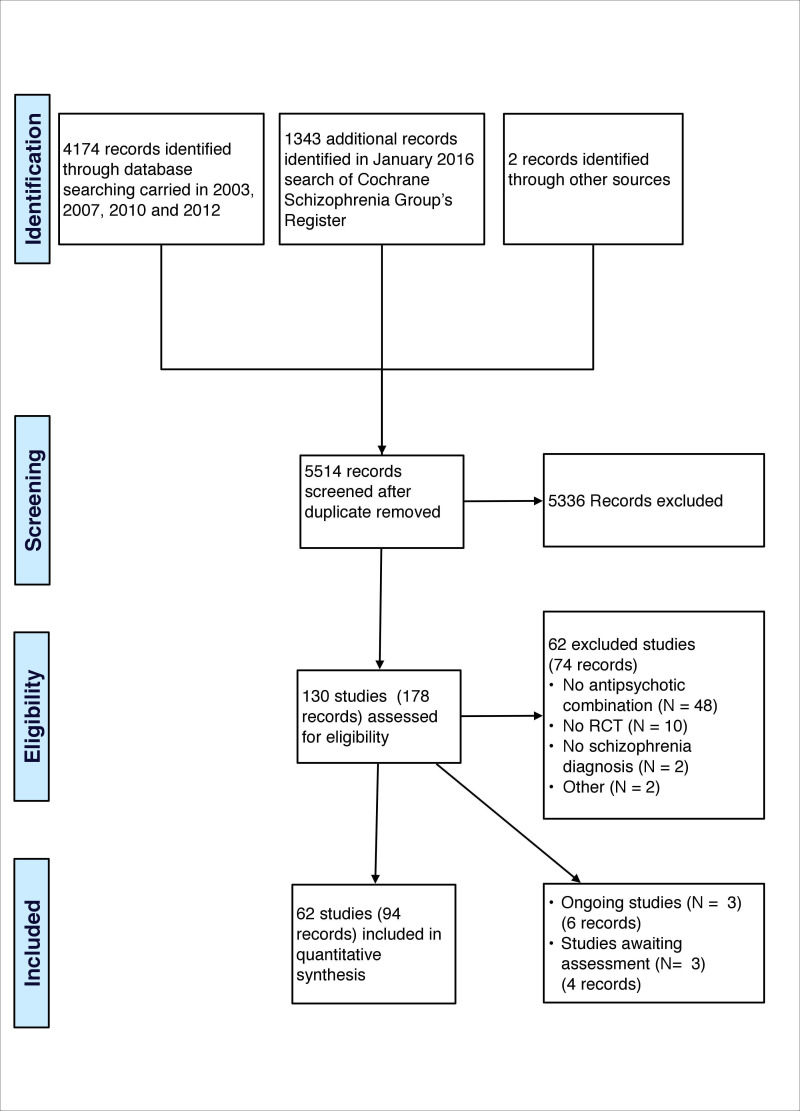

Results of the search

Searches were originally carried out in 2010 and 2012. We supplemented these with a January 2016 search of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Register of trials. Another trial (Xu 2006) was added as it appeared as a reference in one of the included trials (C +aripiprazole 2014). We included one trial (C +aripiprazole 2015b) that was found by methods not described in the protocol (please see Differences between protocol and review). From these searches 62 trials met the inclusion criteria. Sixty‐two trials were excluded. There are three trials awaiting assessment (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification) and there are three ongoing studies (Figure 3).

3.

Naming of the subgroups: The studies were arranged into four subgroups according to the type of antipsychotics used in both arms: clozapine, atypical antipsychotics other than clozapine, typical antipsychotics and any antipsychotics. Naming of the studies: The study tag starts with the duration category (A = long term (over 26 weeks); B = medium term (13 to 26 weeks) and C = short term (up to 12 weeks); the remainder of the tag is the additional drug in the combination antipsychotic group.

Included studies

The current review includes 94 reports describing 62 trials (4833 participants); 41 studies were two‐arm trials comparing an antipsychotic monotherapy with a combination therapy; 12 trials were three‐arm studies comparing two monotherapies with the combination therapy; four were three‐arm trials comparing one monotherapy with two combinations, and three studies were four‐arm trials comparing two monotherapies with two combinations. C +aripiprazole 2015 was a four‐arm trial comparing one combination therapy at three different doses against monotherapy, and, finally, A +pimozide 1985 was an eight‐arm trial comparing two monotherapies at two different doses with one combination therapy at four different doses.

1. Study duration

Forty‐seven of the included studies were short term in duration (less than 12 weeks, C). Eight were of medium term (13 to 26 weeks, B) and seven were long term (over 26 weeks, A).

2. Design

Most of the included studies presented a parallel longitudinal design. However A +reserpine 1957 and C +olanzapine 2012b, were cross‐over trials and we only used data from the first phase of these trials until the point of the first cross‐over. Nine were multi‐centre trials; B +aripiprazole 2008 had centres across Europe and in South Africa, C +risperidone 2006 centres in Canada, Germany, China and the UK, and the other seven within their respective countries include (A +any antipsychotic 2011: USA; B +quet/risp 2009: USA; C +perphenazine 1976: Japan; C +aripiprazole 2013b: Korea; A +any antipsychotic 2015: USA; C +pimozide 2013: USA; C +olan/risp 2014; Japan).

3. Participants

A total of 4833 participants are included (average ˜78 people per study). C +haloperidol 2006 and A +any antipsychotic 2012 did not report the country of origin. See also Appendix 3.

All studies included people with schizophrenia, schizophreniform psychoses, delusional disorder and schizoaffective psychoses. Several means of diagnoses were used. See Appendix 4.

Most studies included people that had chronic schizophrenia and/or had experienced treatment failure while taking monotherapy antipsychotics. The average age was about 36 years old.

4. Settings

Thirty studies included inpatients, 16 studies included outpatients and seven studies both inpatients and outpatients. Two studies (C +aripiprazole 2009; C +sulpiride 1999) included participants in a community setting. Seven studies did not report the setting (C +aripiprazole 2007b, C +aripiprazole 2014, C +haloperidol 2006, C +pipotiazine 2000, C +sertindole 2006, C +sulpiride 1997, and C +sulpiride 2006).

5. Interventions

Full details of the doses used are reported in Characteristics of included studies and Appendix 5. We arranged the studies into four subgroups according to the type of antipsychotics used in both the monotherapy and combination group: clozapine, atypical antipsychotics other than clozapine, typical antipsychotics and any antipsychotics.

In order to determine if the doses used for the antipsychotics in the monotherapy groups were standard, we compared the dosages used in the clinical trials versus dosages suggested by Hasan 2012 and Gardner 2010. We decided not to appraise the interventions in the combination group since there is no evidence for the optimal regimen.

Clozapine in both groups

Thirty‐one studies tested clozapine in both the monotherapy and combination arms of the trial. In 26 of these studies an atypical antipsychotic was added to clozapine in the combination therapy, and in five studies a typical antipsychotic was added to clozapine.

Three studies (B +risperidone 2010, C +olanzapine 2012b and C +risperidone 2005) and of the 31 clozapine studies did not report the doses used. One study (C +sulpiride 2006) used below‐standard doses of clozapine in the monotherapy group. In 25 studies, standard doses of clozapine were used. C +pimozide 2013 reported blood levels and showed higher blood levels of clozapine in the combination group. All except two studies used only oral antipsychotics; B +pipotiazine 2002 and C +pipotiazine 2000 included oral clozapine and pipotiazine administered through muscle injection.

Other atypical antipsychotics in both groups

Eighteen studies tested atypical antipsychotics (other than clozapine) in both the monotherapy and combination therapy arms of the trial. In two of these trials, a typical antipsychotic was added to an atypical one in the combination therapy, and in the other 16 studies, the combination therapy consisted of two atypical antipsychotics. One study (C +clozapine 2013) did not report the doses used. The rest of the studies used a standard dose of the antipsychotic in the monotherapy group. All except one study used only oral antipsychotics; C +fluphen dec 2009 included oral olanzapine and fluphenazine decanoate administered through muscle injection.

Typical antipsychotic in both groups

Nine studies tested typical antipsychotics in both arms. In four of these trials, an atypical antipsychotic was added to the typical antipsychotic in the combination therapy, and in five studies, the combination therapy consisted of two typical antipsychotics. Three studies (C +aripiprazole 2007b; C +aripiprazole 2009; C +levomepromazine 2004) did not report the doses used. Regarding the monotherapy group, three studies used standard doses, two studies (A +pimozide 1985; C +perphenazine 1976) used below‐standard doses, and one study (C +CPZ 1973) used above‐standard doses. All except one study used only oral antipsychotics; C +CPZ 1973 included oral chlorpromazine and fluphenazine decanoate administered through muscle injection.

Any antipsychotic in both groups

Four trials are included in this subgroup. All except one study included participants already on any combination of antipsychotics who were randomised to monotherapy by discontinuation of one of their current antipsychotics and therefore included any combination of two antipsychotics in the combination arm and any one antipsychotic in the monotherapy arm. Doses were reported as haloperidol, chlorpromazine or olanzapine equivalent. Two trials used standard doses, one study (A +any antipsychotic 2015), used above‐standard doses in both groups. A +any antipsychotic 2012 included participants treated with monotherapy who were randomised to switch to combination therapy by adding another antipsychotic or to continue receiving monotherapy. The medication to be added was decided by the prescriber and the patient; no doses were reported for this study.

6. Outcomes

The included studies provided data for the following outcomes: leaving the study early, clinical improvement, relapse, adverse events (serious or requiring discontinuation, death, movement disorders, prolactin level and weight gain), and used various scales to assess treatment effects in global state, mental state general and specific symptoms, movement disorders and quality of life.

6.1 Outcome scales

Only details of scales that provided usable data are shown below. Fifteen different instruments were used to collect scale data. Overall, scale data were poorly presented.

Global state

i. Clinical Global Impression Scale ‐ CGI Scale (Guy 1976) This is used to assess both severity of illness and clinical improvement, by comparing the conditions of the person standardised against other people with the same diagnosis. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores showing decreased severity and/or overall improvement. CGI‐Severity (CGI‐S) is one component of the CGI, which rates illness severity and CGI‐Improvement (CGI‐I) rates improvement. High scores indicate a worse outcome.

ii. Global Assessment Scale of Functioning Scale (GAF) (APA 2000). This is a modified version of the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (Endicott 1976), an observer‐rated scale for evaluating the overall functioning of a patient during a specified time period on a continuum from psychological or psychiatric sickness to health. Score ranges from zero to 100, where a higher score indicates a better outcome.

Mental state

i. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale ‐ PANSS (Kay 1987) This schizophrenia scale has 30 items, each of which can be defined on a seven‐point scoring system varying from one ‐ absent to seven ‐ extreme. This scale can be divided into three sub‐scales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS‐P), and negative symptoms (PANSS‐N). A low score indicates lesser severity. ii. Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962) This is used to assess the severity of abnormal mental state. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18‐item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a seven‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', scoring from zero to six or one to seven. Scores can range from zero to 126, with high scores indicating more severe symptoms.

iii. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms ‐ SAPS (Andreasen 1984) This six‐point scale gives a global rating of positive symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations and disordered thinking. Higher scores indicate more symptoms. iv.Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms ‐ SANS (Andreasen 1983) This scale allows a global rating of the following negative symptoms: alogia (impoverished thinking), affective blunting, avolition‐apathy, anhedonia‐asociality, and attention impairment. Assessments are made on a six‐point scale from zero (not at all) to five (severe). Higher scores indicate more symptoms.

Movement disorders

i. Barnes Akathisia Scale ‐ BAS (Barnes 1989) A scale consisting of four sub‐scales to assess the severity of akathisia: objective rating (zero to three), subjective awareness of restlessness (zero to three), subjective distress related to restlessness (zero to three), and global clinical assessment of akathisia (zero to five). Higher scores indicate more severe akathisia.

ii. Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale ‐ AIMS (Guy 1976) The AIMS is a 12‐item scale consisting of a standardised examination followed by questions rating the orofacial, extremity and trunk movements, as well as three global measurements. Each of these 10 items can be scored from zero (none) to four (severe). Two additional items assess the dental status. The AIMS ranges from zero to 40, with higher scores indicating greater severity.

iii. Simpson Agnus Scale ‐ SAS (Simpson 1970) This scale contains 10 items: gait, arm dropping, shoulder shaking. elbow rigidity, wrist rigidity, leg pendulousness, head dropping, glabella tap, tremor and salivation. Each item is rated between zero and four. A total score is obtained by adding the items and dividing by 10. Scores of up to 0.3 are considered within the normal range. Higher scores indicate greater severity.

iv. Udvalg for Kliniske Undersøgelser Side Effect Rating Scale ‐ UKU (Lingjaerde 1987) A comprehensive, clinician‐rated scale, designed to assess the side effects in patients treated with psychotropic medications. The UKU consists of 48 questions. Zero indicates normal; one indicates mild symptoms; two indicates moderate symptoms; and three indicates severe symptoms. Higher scores indicate greater severity.

v. Drug‐Induced Extrapyramidal Symptoms Scale ‐ DIEPSS (Kim 2002) The DIEPSS developed in Japan consists of four sub‐scales for Parkinsonism (five items), akathisia, dystonia, and dyskinesia in combination with a global evaluation. Each item of assessment is rated on a five‐point scale. The severity of each item is graded from zero (normal) to four (severe), higher scores indicate more severe symptoms. vi. Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale ‐ ESRS (Chouinard 1980) The ESRS measures movement disorders and scores range from zero to 246. There are sub‐scales for parkinsonism (zero to 108), dystonia (zero to 96), and dyskinesia (zero to 42). Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms.

Quality of life

i. Quality of Life Scale ‐ QLS (Heinrich 1984) This six‐point quality of life scale has been designed as an outcome instrument for schizophrenic deficit syndrome as well as to measure impaired functioning in studies of chronic schizophrenia, to assess the deficit syndrome's impact on the patient's life. There are seven severity steps (zero to six, six being adequately functioning and zero being deficient). The time frame is one month. Four item categories have been identified by factor analysis 1) interpersonal relationships (seven items), 2) instrumental role (four items), 3) intrapsychic function (seven items) and 4) commonplace objects and activities.

ii. Subjective well‐being under neuroleptic treatment scale ‐ SWN (Naber 1995) This 38‐item scale with five factors self‐rating scale measures subjective well‐being on neuroleptics. The 20 positively‐ and 18 negatively‐phrased items are rated on a zero to five scale, from not at all, to very much. The five factors are 1) emotional regulation, 2) self‐control, 3) mental functioning, 4) social integration and 5) physical functioning. Low scores predict non‐compliance or discontinuation of treatment in maintenance periods.

iii. Short form‐36 ‐ SF‐36 (Ware 1992) This is a 36‐item scale with two components, one measures the physical component and the other the mental component, the scores range from zero to 100. Each scale is subdivided in four factors. For the physical component: 1) physical functioning, 2) role‐physical, 3) bodily pain, and 4) general health; and for the mental component: 1) vitality, 2) social functioning, 3) role‐emotional, and 4) mental health. Lower scores indicate more disability.

Excluded studies

We excluded 62 studies from the review (Characteristics of excluded studies). Three trials (Barbui 2011, Zink 2009, JPRN‐UMIN000017047) compared two combinations of antipsychotics but did not include a monotherapy. Wu 2015 compared two combinations of antipsychotics with the addition of a systematic nursing intervention. Eighteen studies were randomised control trials testing an antipsychotic combination, but the combinations did not include two antipsychotics. Twelve studies were randomised control trials comparing different antipsychotic monotherapies with another intervention. Seven studies were randomised control trials evaluating switching strategies to a different antipsychotic. Four trials (Sukegawa 2008, Sukegawa 2014, Yamanouchi 2015 and DRKS00008018) did not evaluate the combination of antipsychotics. Semenikhin 2013, NCT01939548 and NCT02477670 did not test antipsychotic drugs. Mantovani 2013 and Mythri 2013 did not evaluate participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Ten studies were not randomised controlled trials. Henderson 2009 was a crossover trial that did not report the results separately for each phase. JPRN‐UMIN000011710 ended without enrolling any patient.

1. Awaiting classification

There are three trials awaiting classification (Studies awaiting classification):

NCT01450514 is a clinical trial, which according to the principal investigator, enrolled patients but was concluded prematurely due to funding problems. We tried to obtain the data from the patients that started the trial, but the sponsor decided to keep the data confidential.

Xu 2006 is a clinical trial that evaluated the effects of aripiprazole compared with placebo on females with hyperprolactinaemia induced by antipsychotics. The placebo used for this trial was vitamin C (100 mg/day), which might have a significant effect on the symptoms of schizophrenia (Magalhães 2016).

Yuan 2014 is a clinical trial with multiple treatment stages. In the third stage, participants were able to receive a combinations of antipsychotics. We tried to obtain data regarding the participants who were enrolled on this stage but no response was received.

2. Ongoing studies

There are three ongoing studies (Characteristics of ongoing studies). One tests amisulpiride augmentation in clozapine‐unresponsive schizophrenia (ISRCTN68824876), one olanzapine and amisulpiride (Schmidt‐Kraepelin 2013), and one aripiprazole augmentation for participants with weight problems treated with clozapine (CTRI‐02‐003397).

Risk of bias in included studies

We prepared a 'Risk of bias' assessment for each trial. For multi‐centre trials providing data for a single centre, we did not assess the risk of bias for each centre. Our judgments regarding the overall risk of bias in individual studies is illustrated in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Allocation

Of the 62 trials analysed in this review, 18 reported an adequate generation of allocation sequence. In two studies (B +sulpiride 1996; C +fluphen dec 2009) the risk of bias was high for sequence generation as a quasi‐randomised method was used, and three studies (C +CPZ 1999, C +sulpiride 1999, C +sulpiride 1999b) had a high risk of bias as they randomised according to hospital admission order or time. In all remaining studies, the method of assignment was unclear. Similarly, methods used to conceal allocation had a low risk of bias in 16 trials, high risk of bias in one and unclear in the remainder (please see Differences between protocol and review).

Blinding

In 19 studies, participants, care providers, and outcome assessors were blinded, 12 studies were high risk of bias for blinding as they were either open‐label studies or the participants and personnel were not blinded; the risk of bias was unclear for the remaining 31 trials.

Incomplete outcome data

There was a low risk of bias for incomplete data in 33 studies, an unclear risk of bias in nine studies, and a high risk of bias in 20 trials.

Selective reporting

Twenty‐three studies were free from selective reporting, 36 studies had a high risk of bias for selective reporting, and three had an unclear risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Twenty‐three studies were free from other biases, eight were subject to other biases and in the remaining studies the risk of bias was unclear.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Where data were available, they were arranged into four subgroups according to the type of antipsychotics used in both arms: clozapine, atypical antipsychotics other than clozapine, typical antipsychotics and any antipsychotics. Studies were also named according to the add‐on antipsychotic (see Description of studies), so it is possible to see in each analysis more information about the combination of antipsychotics used in each study, as well as the length of follow‐up.

Where data were missing, such as standard deviations for continuous outcomes, we imputed these data using trials with similar means for that scale. We used the mean difference and reported the data separately for different scales within an outcome (Appendix 6).

For studies with more than two comparison groups we combined data, i.e. if the study tested different antipsychotics in two monotherapy groups or two combination groups. Where studies had two monotherapy groups, for studies with typical drugs in both groups data from the monotherapy groups were combined; for studies with clozapine in both groups, only data from the clozapine monotherapy group was added to the data analysis.

1. COMPARISON 1: ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY

This particular comparison has 63 outcomes.

1.1 Clinical response: 1. No clinically important response ‐ not improved

We found twenty‐nine trials (N = 2398), with six weeks to three years follow‐up. We found that the use combination of antipsychotics may reducing the risk of no clinical response (RR 0.73 CI 0.64 to 0.83; Analysis 1.1; very low quality evidence). Results showed an important heterogeneity (I2 = 54%). When we split the trials by length of follow‐up, the results remain but there is no heterogeneity for the longer‐term trials ‐ the heterogeneity may be due to the short‐term trials.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 1 Clinical response: 1. No clinically important response ‐ not improved.

1.1.1 clozapine in both groups

Trials with clozapine (N = 1127); in both groups also favoured the combination therapy (RR 0.66 CI 53 to 0.83), but had high heterogeneity (I² = 64%) and no obviously outlying trials.

1.1.2 other atypical in both groups

Seven trials tested atypical in both groups (N = 674). There was not a clear difference between antipsychotic combinations and antipsychotic monotherapy within this subgroup (RR 0.95 CI 0.83 to 1.09).

1.1.3 typical drugs in both groups

We found five trials to be relevant to this subgroup, which included a total of 597 participants. For this outcome, we did find evidence that antipsychotic combinations reduced the risk of no response when compared with antipsychotic monotherapy (RR 0.64 CI 0.49 to 0.84). For this subgroup heterogeneity is moderately high (I2 = 47%) but when the outlying trial C +perphenazine 1976 is removed the results show no heterogeneity.

1.2 Clinical response: 2. Relapse

Three trials (N = 512), with follow‐up durations of eight weeks, one year and three years, respectively provided data regarding relapse. Results showed high heterogeneity (I² = 81%), when the outlying study (A +pimozide 1985) is removed heterogeneity is restored. But as this trial carries more than 10% of the weighting for this outcome, the results were not pooled. A +sulpiride 1994 and C +perphenazine 1976 found no difference between the two interventions. A +pimozide 1985 found that antipsychotics combinations is more effective for preventing relapse when compared to monotherapy.

1.3 Leaving the study early

Forty‐three trials (N = 3137), with six weeks to one year follow‐up found no difference in the number of people leaving the study early (RR 0.90 CI 0.76 to 1.07; Analysis 1.3, low‐quality evidence). Subgroup analysis showed no important difference between groups.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 3 Leaving the study early.

1.4 Service utilisation: Hospital admission

Three trials (N = 202), with follow‐up duration of eight, ten weeks and six months, respectively, provided data on hospital admission. Two trials tested clozapine in both groups, and the other tested any antipsychotics in both groups. A combination of antipsychotics was not superior or inferior to antipsychotic monotherapy in preventing hospital admission (RR 0.96 CI 0.36 to 2.55; Analysis 1.4, very low‐quality evidence). None of the subgroups showed different results.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 4 Service utilisation: Hospital admission.

1.5 Clinical response: 3. Global state ‐ i. average severity score (CGI‐S scale, high = bad)

For this outcome we found seven relevant studies which provided endpoint data regarding global state on the severity component of the CGI scale, with six weeks to three years follow‐up involving 496 participants. For this outcome, we did not find evidence that antipsychotic combinations was different in its effects compared with antipsychotic monotherapy (MD ‐0.13 CI ‐0.31 to 0.06, Analysis 1.5). This outcome had moderate levels of heterogeneity (I2 = 44%). None of the subgroups showed different results.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 5 Clinical response: 3. Global state ‐ i. average severity score (CGI‐S scale, high = bad).

1.6 Clinical response: 3. Global state ‐ ii. change in severity score (CGI‐S scale, high = bad)

Three relevant (N = 233) studies involving 233 participants only provided change data regarding this scale. For this outcome, we did not find evidence that antipsychotic combinations was clearly different in its effects compared with antipsychotic monotherapy (MD 0.11 CI ‐0.09 to 0.32; Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 6 Clinical response: 3. Global state ‐ ii. change in severity score (CGI‐S scale, high = bad).

1.7 Clinical response: 4. Global state ‐ average improvement score (CGI‐I scale, high = bad)

Four trials, with ten to 16 weeks follow‐up, measured global state on the improvement component of the CGI scale. We found that the combination therapy may improve clinical response when compared to monotherapy (MD ‐0.36 CI ‐0.58 to ‐0.13; Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 7 Clinical response: 4. Global state ‐ average improvement score (CGI‐I scale, high = bad).

1.8 Clinical response: 5. Global state ‐ i. average functioning score (GAF scale, high = good)

We identified three studies relevant to this outcome, with 6 to 12 weeks follow‐up, involving 107 participants. For this outcome heterogeneity is high (I2 = 80%). When C +risperidone 2005 is removed, heterogeneity is restored but as this trial carries more than 10% of the weighting for this outcome, the results were not pooled and we only presented the data for the subgroups:

1.8.1 Clozapine in both groups

There is a single trial in this subgroup, which included a total of 30 participants. We found evidence that antipsychotics combination is worse than monotherapy for improvement of the global state (MD ‐4.5 CI ‐8.38 to ‐0.62; Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 8 Clinical response: 5. Global state ‐ i. average functioning score (GAF scale, high = good).

1.8.2 Other atypical drugs in both groups

There are two relevant trials in this subgroup, which included a total of 77 participants. We found evidence that the use antipsychotic combinations when compared to antipsychotic monotherapy improves the global state when assessed with the GAF scale (MD 8.73 CI 1.56 to 15.9; Analysis 1.8).

1.9 Clinical response: 5. Global state ‐ ii. change in functioning score (GAF scale, high = good)

We found three studies (N = 349) which provided only change data for the GAF scale, we did not find evidence of a clear difference between the two treatments in this comparison (MD 0.27 CI ‐1.42 to 1.97; Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 9 Clinical response: 5. Global state ‐ ii. change in functioning score (GAF scale, high = good).

1.10 Mental state: 1. Overall ‐ a.i average total score (PANSS scale, high = bad)

We identified 11 studies relevant to this outcome involving 721 participants. We did not find evidence of a clear difference between the two treatments in this comparison. This outcome had important levels of heterogeneity (I2 = 58%). When B +ziprasidone 2014 and C +risperidone 2001 are removed, heterogeneity is decreased but as these trials carry more than 10% of the weighting for this outcome, the results were not pooled.

1.11 Mental state: 1. Overall ‐ a.ii change in total score (PANSS scale, high = bad)

Eight studies (N = 406) only provided change data for the PANSS scale, we did not find evidence of a clear difference between the two treatments in this comparison (MD ‐1.05 CI ‐3.42 to 1.32; Analysis 1.11). Subgroup analysis showed no difference.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 11 Mental state: 1. Overall ‐ a.ii change in total score (PANSS scale, high = bad).

1.12 Mental state: 1. Overall ‐ b.i. average total score (BPRS scale, high = bad)

We found 21 trials (N = 1082), with six weeks to six months follow‐up, who reported data for mental state on the BPRS scale, but results showed high heterogeneity (I² = 92%; Analysis 1.12). Removal of the outlying studies C +sulpiride 1999b and C +sulpiride 2003 reduces heterogeneity for the clozapine subgroup (I² = 47%), but not for the pooled results (I² = 81%). Data were, therefore, not pooled for this outcome.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 12 Mental state: 1. Overall ‐ b.i. average total score (BPRS scale, high = bad).

1.13 Mental state: 1. Overall ‐ b.ii change total score (BPRS scale, high = bad)

We identified one study which only provided change data for this outcome involving 100 participants. We did find evidence that antipsychotic combinations improved the overall mental state when evaluated with the BPRS scale (MD ‐2.72 CI ‐5.37 to ‐0.07; Analysis 1.13).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 13 Mental state: 1. Overall ‐ b.ii change total score (BPRS scale, high = bad).

1.14 Mental state: 2. Specific ‐ a. positive symptoms ‐ no clinical improvement

Two trials, with six and 10 weeks follow‐up, reported binary data for no clinical improvement on positive symptoms, but the results showed high heterogeneity (I² = 80; Analysis 1.14). Data were, therefore, not pooled for this outcome. None of the studies showed a difference between the two groups.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 14 Mental state: 2. Specific ‐ a. positive symptoms ‐ no clinical improvement.

1.15 Mental state: 2. Specific ‐ b. positive symptoms ‐ i. average score (PANSS scale, high = bad)

For this outcome we found four relevant studies involving 158 participants. We found evidence that participants assigned to antipsychotics combinations had a poorer response to the positive symptoms than patients assigned to antipsychotics monotherapy (MD 2.02 CI 0.90 to 3.14; Analysis 1.15). The results are due to the trials in the subgroup where clozapine was used in both groups.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 15 Mental state: 2. Specific ‐ b. positive symptoms ‐ i. average score (PANSS scale, high = bad).

1.16 Mental state: 2. Specific ‐ b. positive symptoms ‐ ii. change score (PANSS scale, high = bad)

We identified nine studies who reported only change data for the positive symptoms assessed with the PANSS scale. We did not find evidence of a clear difference between antipsychotic combinations and antipsychotic monotherapy (MD 0.01 CI ‐0.45 to 0.47; Analysis 1.16).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 16 Mental state: 2. Specific ‐ b. positive symptoms ‐ ii. change score (PANSS scale, high = bad).

1.17 Mental state: 2. Specific ‐ b. positive symptoms ‐ iii. average score (BPRS scale, high = bad)

We identified three studies, with a follow‐up time between eight and 16 weeks, we did not find evidence of a clear difference between antipsychotic combinations and antipsychotic monotherapy (MD ‐1.02 CI ‐2.42 to 0.38; Analysis 1.17). This outcome had moderate levels of heterogeneity (I2 = 41%). We did not find a difference in the results between subgroups.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 17 Mental state: 2. Specific ‐ b. positive symptoms ‐ iii. average score (BPRS scale, high = bad).

1.18 Mental state: 2. Specific ‐ b. positive symptoms ‐ iv. change data (BPRS scale, high = bad)

We identified one study (N = 17) which only reported change data for the positive symptoms when assessed with the BPRS scale. We did not find evidence of a clear difference between antipsychotic combinations and antipsychotic monotherapy (MD ‐0.3 CI ‐1.16 to 0.56; Analysis 1.18)

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANTIPSYCHOTIC COMBINATIONS vs ANTIPSYCHOTIC MONOTHERAPY, Outcome 18 Mental state: 2. Specific ‐ b. positive symptoms ‐ iv. change data (BPRS scale, high = bad).

1.19 Mental state: 2. Specific ‐ b. positive symptoms ‐ v. average score (SAPS scale, high = bad)

We identified one study relevant to this outcome involving 28 participants. For this outcome, we did find evidence that antipsychotic combinations is better than monotherapy for the positive symptoms when assessed with the SAPS scale (MD ‐6.76 CI ‐11.91 to ‐1.61, Analysis 1.19).

1.19. Analysis.