Abstract

Objective:

Inadequate healthcare quality may contribute to Native American health disparities through racial/ethnic discrimination by healthcare professionals. Nursing approaches to relationships and caring offer a means to understand health disparities through an unconventional lens. The study objective was to examine health disparities within the context of patient/nurse relationships.

Design:

A descriptive-qualitative method guided data collection and analysis. Eleven nurses who serve Native Americans were interviewed. They described attitudes, meaningful relationships, and nurse leadership.

Results:

Nurses discussed their perceptions of and experiences with Native American patients. Four themes emerged: shared patient/nurse values, patient-centered care, external forces, and stereotype-driven care.

Conclusions:

Are we ready for the challenge to advocate for, build, and sustain organizational structures that support caring relationships? Implications for public health nursing include being intentional about recognizing implicit biases and ethnocentrism; examining nurses’ complicit roles in perpetuating racism; and developing mechanisms to collectively advocate for improved Native American health.

Keywords: Native Americans, health disparities, relationships, public health nursing practice, qualitative research

Background

Native Americans experience disproportionate health disparities related to chronic diseases, unintentional and intentional injuries, and violent crimes as evidenced by higher morbidity and mortality (Indian Health Service, 2017; Hall et al., 2015). Many Native Americans reside in rural areas and, for rural minorities, disproportionate health problems are associated with insufficient access to and quality of care (Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2016). Among other factors, inadequate healthcare quality contributes to health disparities through racial/ethnic prejudice of healthcare professionals (Hall et al, 2015) and related discrimination (Smith, 2007). Healthcare professionals, however, tend to dismiss their role in discrimination and may believe racism is no longer an issue, too political to discuss, or too difficult to resolve (Johnstone & Kanitsaki, 2010). Consequently, providers may only discuss health disparities within the context of less personally threatening factors, e.g. low health literacy, cultural and language challenges, and lack of cultural competency (Johnstone & Kanitsaki, 2010). Understanding healthcare quality and related health disparities is multifaceted and inherent to public health nursing care. Therefore, a culturally-competent approach to the patient/nurse relationship is essential.

Socializing culturally-competent nurses begins with nursing education (Tilki et al., 2007) and is an important aspect of nursing curriculum (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2008). However, many rural nursing faculty perceive themselves as culturally aware but lacking cultural knowledge (Diaz, Clarke, & Gatua, 2015). In addition, the issue of racism is often avoided in nursing education (Lancellotti, 2008). Nurse education is conceptualized through a “White lens” (Scammell & Olumide, 2012, p. 545) in spite of intentional efforts to diversify faculty and students. Many nurses remain complicit in perpetuating racism within the healthcare environment (Hall & Fields, 2013). In rural areas, it is important to understand how nurses and nurse educators view cultural competence in order to prepare a workforce that effectively delivers quality healthcare (Diaz, Clarke, & Gatua, 2015).

Moreover, nurses are socialized within the larger societal context. Smith (2007) proposed a lack of caring within society is foundational to the perpetuation of discrimination and health disparities. Within this context, implicit racial/ethnic bias negatively affects patient/healthcare provider relationships (Hall et al., 2015). As caring and ethical mandates are inherent to nursing practice (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2015, pp. 8, 18), nurses have the potential to lead health disparities reduction efforts (Hall & Fields, 2013; Smith, 2007). The purpose of this study was to examine health disparities within the context of patient/nurse relationships, nurse perspectives of their patients, and nursing-care actions. The impetus for this study was anecdotal evidence suggesting that racism negatively impacts nursing care of the Native American patient.

Methods

Design and Sample

A descriptive-qualitative methodology was used for understanding the parameters of the patient/nurse relationship in the context of Native American health. The university institutional review board approved the research procedures.

A targeted sampling approach was applied to the recruitment process. The population from which the sample was selected included nurses employed at public (public health nursing, Women, Infants, and Children [WIC], and a community college nursing department) and Native American owned or managed (tribal health, home health and hospice, dialysis, K-12 schools, and a nurse-run casino employee clinic) healthcare institutions/facilities located either within the boundaries of a western reservation or had a service area within this boundary. Nurses were recruited with the assistance of community health leaders. Researchers mailed letters to explain the purpose of the study and included a postage-paid postcard. Nurses responded with the following information: interest in participation, convenient days and times for a phone interview, and contact information. Letters were sent to a total of 17 nurses; zero letters were returned as “return to sender”, one response card was returned indicating no interest in the study, and three response cards were returned indicating interest in the study (however, these nurses did not respond to contact attempts).

Data Collection/Measures

A member of the research team scheduled interviews with nurses who were interested in the study, met the inclusion criteria (18 years of age or older and had direct contact with Native American individuals who seek health services), and willing to engage in an audio-recorded semi-structured phone interview lasting 30 to 60 minutes. Two faculty members conducted all interviews during a six-month time period. Five interviews were conducted independently, and six interviews were conducted together. Prior to the interview, nurses read and verbally consented to the interview and to be audio recorded. A researcher-assigned participant ID number and a participant-provided pseudonym was used in all documents and interviews. An interview guide was used during all interviews to ensure consistent inquiries and interview format (see Figure I). Interview questions were created by investigators based on concepts within relevant literature. Follow up questions were used to clarify and explore respondents’ answers. The two interviewers continually reviewed interview content and notes and met regularly to discuss data saturation points. The interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and verified for accuracy.

Figure I.

Interview Question Set

Nurses provided information about highest level of nursing education, number of years worked in nursing, details of current job (type of health care setting, length of employment, nursing role/title), approximate number of patients seen per week, approximate number of Native American patients seen per week, and length of time worked with Native American patients. Nurses also provided demographic information including age, gender, and race/ethnicity.

Analytic Strategy

Two faculty members coded the interviews using thematic analysis (Harding, 2013). Researchers independently read each interview transcript and wrote a summary of each interview. Main concepts were identified from comparison of interview summaries. Interview texts were reviewed to find quotes and data segments to support the main concepts. Next, selective and conceptual decisions about larger segments of data were made by refining main concepts, creating categories, comparing categories with associated data, comparing data to associated categories, refining categories, and determining key themes. After key themes were identified, the analysis was verified by returning to the interview texts and evaluating the accuracy of associated key categories. Thematic analysis involved constant-comparison through the examination of (a) similarities and differences and (b) relationships between concepts.

Trustworthiness was addressed through credibility, validity, and confirmability. Credibility was addressed through investigator triangulation during each phase of the process, including periodic discussion of findings and relationships (Polit & Beck, 2004). Techniques used to address validity included (a) developing an evidence-based interview tool, (b) developing and implementing a written analysis process (Harding, 2013), (c) independent reading and summarizing of each interview transcript prior to analysis (Schmidt, 2004), (d) rereading transcripts subsequent to analysis and comparing to findings (Harding, 2013), and (e) creating diagrams to understand relationships among concepts and themes (Straus & Corbin, 1998). Confirmability was evidenced by reviewing interview content with participants at the end of each interview as well as documentation of raw data, analysis notes and products, and interview development information.

Results

Eleven nurses in a western, rural county were interviewed for this study. Nurses ranged in age from 39–67, were mostly female, and lived in the county for an average of 30 years (range = 4–67). Nurses served in a variety of direct (service at point-of-care) and indirect (judgment and action provided on behalf of patients) care roles (Suby, 2009; Upenieks, Akhavan, Kolterman, Esser, & Ngo, 2007). Nurses worked in for an average of 21 years (range = 5–30) and with Native Americans for an average of 19 years (range = 4–30).

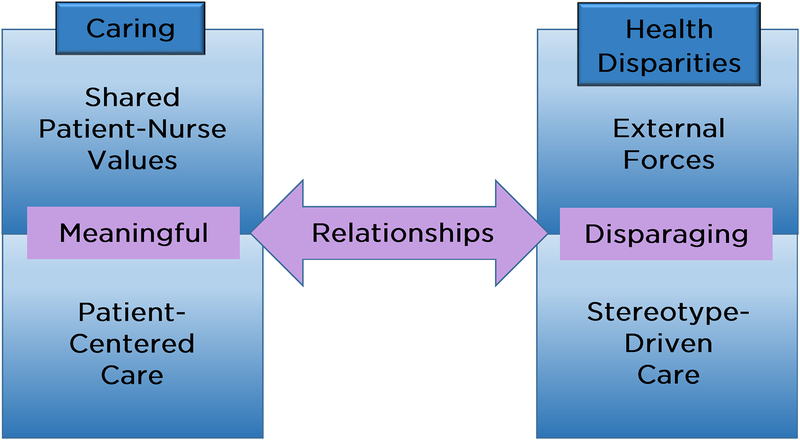

During the interviews, nurses discussed their perceptions of and experiences with Native American patients. We specifically asked about attitudes, meaningful relationships, and nurse leadership. Data analysis revealed four interrelated themes: shared patient/nurse values, patient-centered care, external forces, and stereotype-driven care. The interviews uncovered attitudes and values that impact nursing care and the patient/nurse relationship. Common attitudes and behaviors with a positive impact on nursing care included connection, trust, respect, and partnership. On the other hand, nursing care was negatively influenced by unsupportive attitudes, prejudice, and bias. Nurses also discussed their view of nurse leadership in the context of Native American health and the importance of patient advocacy. Relationships contributed to a dichotomy between the themes, shared patient/nurse values and patient-centered care, and the themes external forces and stereotype-driven care (see Figure II). In essence, the opportunity to take time contributed to trusting relationships and the lack of time contributed to disparaging. Nurses’ discussion of health disparities related to Native American health was identified throughout and within each theme. Representative quotes for each theme are labeled with a randomly assigned interview number.

Figure II.

Public Health Nursing and Native American Health: A Dichotomy that Fosters Caring and Perpetuates Health Disparities

Shared Patient-Nurse Values

Nurses’ descriptions of nursing care in the context of Native American health reflected awareness of values shared among patients, nurses, and within the health care system. Most nurses discussed that responsiveness to values would facilitate health improvements. Nurses described values such as “connection”, “respect”, “holism”, and “family” as well as the common goal of improved health. These shared values were also viewed as important to establishing meaningful relationships with patients and that meaningful relationships are developed through “cultural understanding”, “taking time”, and “listening”. “[One patient] always sticks out in my mind…She taught me to step back and listen, she was sharing a big part of her life with me and I was trying to get everything done that I needed to do, but…if you don’t listen and you’re busy trying to get all your tasks done, sometimes you miss what they want to share.” (Interview 4)

Nurses’ discussion of shared values reflected their feelings of it being a challenging yet important aspect of nursing care. “The healthcare professional relationship…the Native American knows they need care in order to get better and the nurse knows she needs to maintain professionalism and observe the patient’s rights, so that the outcome is optimal.” (Interview 6)

The integration of Native American values into nursing care was described as important to improving patient health outcomes. Most participants emphasized that Native American values should be honored and accommodated within the health care system (i.e., ceremonies, traditions). In addition, learning about patient values and culture was viewed as essential to building meaningful relationships. “We need to remember it’s not always our way [health care] that has to be done. If they [patients] were given the opportunity to work their own medicine…It’s not all about what we believe…It’s what they believe and what we do with it. Do we laugh it off or take it seriously and figure out how we can work with them?” (Interview 9)

While participants discussed the importance of considering values that are specific to the Native American culture, they also described the values that are common to various cultures. “I consider Native American values. I think they value family, children, modesty but I can’t say that those are specific things that only Native Americans value…I think respect of all people is part of being a nurse, and of their values.” (Interview 5)

Patient-Centered Care

Nurses described patient-centeredness as an important aspect of the nurse/patient relationship and many participants emphasized it as an essential part of nursing care. Specific patient-centered activities discussed by nurses included making connections, listening, and taking one’s time. “I’m always in a patient’s room. I love to visit with my patients, I like to find out who they are, where they’re from, how they’re doing holistically. I mean, they might be in for a fractured hip, but we’ve got to take the time.” (Interview 3)

The commonality between the health care culture and Native American culture was described in the context of better health. And, patient-centeredness and patient empowerment were discussed as a main component of health improvements. Incorporating Native American values into nursing care was described as important but only effective if patient-driven. “You really have to have the ability to look at yourself…know your values and stand with your values and yet accept their values, even if they’re different, and bring them together for the benefit of the patient and your goal. So how do we do this with my values and respecting theirs? How do you carry yourself so it happens for the benefit of the patient? That’s a challenge.” (Interview 1)

When describing nurse leadership, our participants discussed the role of patient-centered care and most commonly described leadership in terms of patient advocacy. Nurses used phrases such as “patients come first” and “I will stand up for them”. “Everything starts with advocacy. If that’s your driving force, figuring out what’s best for the patient, what do they want and how to best serve them…then actions follow and you become a leader, not because you set out to become a leader, but because you’re doing what’s best for your patient.” (Interview 10)

Challenges associated with patient-centered care in the context of Native American health were discussed in terms of culture and the health system. Participants described how nurse attitudes toward Native American individuals, such as bias and negativity, might affect nursing care. Some nurses’ comments imply how such challenges may impact the continuation of health disparities among Native American individuals. “Native-American patients can be more needy and it’s not them personally deciding that they’re going to be more needy. They’re more dependent on their health care system, which they feel doesn’t work real well for them…and because of oppression, more disease per population, more family history of diabetes and heart disease and alcoholism…things that they live with on a day-to-day basis…they tend to come in a little more needy and a little more, entitled. That puts the nurse kinda at edge I think or uncomfortable or some preconceived idea.” (Interview 1)

External Forces

Nurses described lack of time and resources as external forces that impact nursing care and leadership. Taking the time to listen and understand patient circumstances was discussed as essential to establishing a trusting nurse/patient relationship. “The nurse is so busy, or they have a one-on-one [patient] that requires a lot of their time that they don’t have the time to spend with [other] patients. One of the things that…really frustrated me as a nurse was that I couldn’t bond that relationship.” (Interview 3)

Participants discussed challenges related to advocating for Native American patients and its impact on nursing care. Nurses discussed advocacy in terms of leading the patient through the system, going beyond the limits, and bridging the gap between patients and the health care system. Specifically, patient advocacy and the behaviors that follow were described as pivotal to nurse leadership. “I think there’s a ton of hurdles to advocacy. When people advocate for patients not only is it not welcome, but then, the person who was advocating needs an advocate because they become a target or it’s a nuisance. I’ve had people that really fought policies because they believed it for the good of the patient. And, now they’re looked at as ‘well, you know, you’re just creating headaches and you’re just creating problems’.” (Interview 10)

Lack of resources within the Native American community and socioeconomic factors that contribute to health disparities were described as having an impact on nursing care and leadership. In some instances, the ways in which Native American patients utilize and have access to the health system was described as being a barrier to meaningful nurse/patient relationships. One nurse noted, “access obstacles are transportation, no minutes on their cell phone, no ride to the class, so it’s like a cycle.” (Interview 4). And stated, “I would say the population we serve, we know that there’s limited resources. There’s so much we can offer them, but the other thing is…the roles we play, time has a big portion of the care that we give. If we had more time we could look into other options…in the county or state to see what kind of programs are out there.” (Interview 4)

Stereotype-Driven Care

Nurses’ description of nursing care reflected the impact of stereotypes often associated with Native American individuals. Unsupportive attitudes, derogatory comments, and historical trauma in the region were discussed as challenges in the nursing environment. Most nurses commented that the negative attitudes were often due to politics in the region. “What I have found because I work in different settings and I have been around the Native American population is that a lot of nurses classify or group them all into one. That they’re all drunks…that almost like they’re lower human than we are.” (Interview 3)

Some nurses discussed their own lack of prejudice. For example, “I feel that I’ve got no prejudice against anyone…colored skin or sexual preference or whatever…I’m going to treat them all the same. It’s hard when you hear negativity, to stand up for it because you get targeted for being the one with rose-colored glasses.” (Interview 9)

Stereotype-driven care may also be a result of a hopelessness that nurses encounter through the nursing care experience. As many of our participants have lived and worked in the region for a long period of time, they were very aware of the trauma, hopelessness, and pain experienced by Native American individuals. Such awareness implies a sense of hopelessness shared in common with Native Americans. “I think the struggles…the trauma, the grief, the poverty, the depression, the domestic violence, the drugs, plays a big role on attitudes. The hurt and the pain you can see in the eyes of patients. Just knowing, because being in the community, the struggle…But, your work is so fast and you’re just doing your work as a nurse, if you had an extra five or ten minutes, you could get this patient’s full story.” (Interview 4)

In some cases, participants discussed that their perception of nurse negative comments and attitudes about Native American patients was due to real health issues and concerns among Native American individuals. Yet, spending additional time and education with Native American patients specific to these health issues was challenging. “We’re very much aware of the problems that Native Americans have and I spend time teaching, especially about diabetes. I know there are programs, but I’m finding that a lot of it’s not getting through.” (Interview 2)

Findings revealed the challenges of nursing care in relation to Native American health may contribute to the perpetuation of health disparities for Native American patients. For example, negative attitudes and comments were often viewed as being associated with Native American lifestyle, health issues, and health care usage. “In my years as [other occupation], I [heard] racial statements. ‘Well, here’s Mr. X, here from drinking again. This is what his blood alcohol was’. Another comment I heard frequently ‘Well this person wouldn’t have had pancreatitis if they wouldn’t have been hooked on alcohol’. Most times I hear derogatory comments from those nurses who have been nurses for quite some time and I have been quick to point out their comments and tell them they’re taking care of a person that’s still a human.” (Interview 6)

Discussion

Our study revealed nurses’ struggle to meet personal and professional expectations in delivering culturally-competent care. Insights gained from this study can advance public health nursing practice by challenging nurses to critically reflect upon their experiences and to dialogue with each other regarding their individual and collective roles in perpetuating as well as reducing health disparities.

Study findings indicate nurses’ role in reducing health disparities occurs within the context of patient-centered care and shared patient-nurse values. Based on our findings, it is evident that caring nurse behaviors and actions, e.g. connecting, listening and taking one’s time, incorporating Native American values into nursing care, and patient empowerment and advocacy, contribute to positive patient/nurse relationships. Nurses can advance patient-centered care by considering Leininger’s Theory of Culture Care Diversity and Universality. This theory describes caring as the context for practice, serving as a bridge between cultural and professional healthcare practices (Leininger &McFarland, 2002; Leininger &McFarland, 2006). For example, nurses serve an essential role in bridging cultural and professional healthcare practices through the integration of generic (learned through experiencing cultural interpersonal behaviors) and professional (learned through nursing education) approaches to caring (Leininger &McFarland, 2002; Leininger &McFarland, 2006). Culture-centered nursing care is enhanced through shared values of respect, holism, empowerment, interpersonal relationships, cultural knowledge and skills, and individualized care (Lor, Crooks, & Tluczek, 2016, p. 352). Moreover, caring results in mutual outcomes for the nurse as well as the patient, including a sense of satisfaction (Finfgeld-Connett, 2008).

In contrast, study findings suggest that nurses’ role in perpetuating health disparities is fueled by external forces and is evidenced in the provision of stereotype-driven care. Participants spoke of other nurses who demonstrated prejudicial attitudes and behaviors, and yet none of the nurses reported evidence of their own bias. However, participants may have responded in a socially desirable manner due to the nature of the questions and research. It is important for nurses to have open and honest discussions about stereotype-drive care because prejudicial attitudes and behaviors are antecedent to poor patient/nurse relationships, and related health outcomes and health disparities (Lor, Crooks, & Tluczek, 2016, p. 352). Study findings are supported by the literature as many nurses remain complicit in perpetuating racism within the healthcare environment and are unlikely to examine their own biases (Hall & Fields, 2013).

Culturally-competent caring involves self-awareness and open-mindedness (Dudas, 2012). Intentionality regarding self-awareness, purpose, and efficacy are essential in caring for patients (Pilkington, 2005). Lack of awareness of one’s implicit biases fuels negative patient-provider interactions and health outcomes (Hall et al., 2015). This intentional work begins with a self-reflective and meditative approach to preparation for a caring encounter by using multiple ways of knowing (e.g. cultural, spiritual, intuitive, aesthetic, science) and seeking to understand through patient stories, health needs, and meaning of healing (Watson, 2010).

The caring approach to relationship development requires the nurse be aware of her/his assumptions and related judgments regarding their patients and that a moral commitment be honored (Lachman, 2012). Disregard for this can create non-caring ethnocentric practices (Leininger, 2002). Nurses can begin to address the reduction of health disparities by embarking on personal journeys of self-examination. This work is inherent to caring theory through the “internal work of self-reflection and growth” (Pipe, 2008, p. 117) and is essential for culturally-competent care (Douglas et al., 2014). We propose that integrating caring and transformative learning theories can guide individual growth and effective nursing practice. Key to both theories is critical self-reflection. This entails the identification of one’s assumptions and validating (or not) these assumptions with evidence (Brookfield, 2012, Cranton, 2006). Critical reflection is aided by dialogue (Mezirow, 2000); however, it is important to seek out persons that do not simply mirror one’s assumptions (Brookfield, 2012; Cranton, 2006). A normal response to this process is discomfort and discontent, signs that learning and transformation are likely occurring (Mezirow & Taylor, 2009). Nurses, regardless of position and setting, play an important leadership role in this transformative process. Findings suggest that this process is fostered through role modeling, mentoring, and education. For example, cultural competence education focused on self-awareness and reflection can improve nurse understanding of how stereotypes and external forces can negatively impact patient-centered care.

Implications for Public Health Nursing

In spite of a rich history of cultural-competency education, study findings bring to the forefront a dichotomy within which nurses practice cultural competence. To address challenges of patient-centered care in the context of health disparities, public health nurses can utilize caring theory beginning at the point-of-care and in decisions and actions taken on behalf of the patient. Nurses can acknowledge stereotype-driven care by recognizing implicit bias and ethnocentrism as a starting place for examining one’s assumptions and improving cultural competency in nurses and nursing students. White nurses can start a dialogue with each other to help to help raise awareness regarding racism, nurses, and Whiteness (Hall & Fields, 2013). Nurses can take leadership roles in examining institutional processes and nurses’ complicit roles in perpetuating racism (Hall & Fields, 2013). Nurses can create and sustain organizational structures that support a culture of caring for the nurse and the patient (Carter et al., 2008). Lastly, public health nurses can enhance mechanisms to mobilize resources and collectively advocate to improve patient-nurse relationships, nursing care, organizational priorities and processes, and ultimately Native American health.

Study limitations include the targeted recruitment approach. While our recruitment efforts attracted nurses committed to Native Americans and their health, it may have limited the diversity of our interview pool and associated perspectives. It is likely that our sample did not include nurses uninterested in fostering Native American health. In addition, the impetus for the study, i.e. antidotal data suggesting racism among nurses, may have contributed to our own implicit biases. Upon reflection as White faculty, we may have unintentionally avoided probing deeper into the interviews in order to lessen our own discomfort. Future research is needed to compare and contrast nurse perspectives and Native Americans’ conceptualization of caring for the purpose of improving nurse/patient relationships.

Conclusion

Public health nurses are ubiquitous because they serve in a variety of settings. They are holistic and collaborative in their approach to care and are trained in areas pertinent to the reduction of health disparities. Public health nurses are in a unique position to foster a caring culture and embark in dialogue regarding racism within any setting. Are public health nurses ready to elevate their leadership role in reducing health disparities? Are we ready for the challenge to advocate for, build, and sustain organizational structures that support caring relationships? Challenging each of us to examine individual and collective roles regarding the perpetuation and/or reduction of health disparities can advance public health nursing practice.

Acknowledgements

Funding source: This research was funded, in part, by NIH/NIGMS grant # 8 P20 GM103432–12 through the Wyoming INBRE program.

Contributor Information

Mary Anne Purtzer, Fay W. Whitney School of Nursing, University of Wyoming, Dept. 3065, 1000 E. University, Laramie, WY 82071, mpurtzer@uwyo.edu, Tel: 307-766-6576, Fax: 307-766-4294.

Jenifer Thomas, Fay W. Whitney School of Nursing, University of Wyoming.

References

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). (2008). Cultural competency in baccalaureate nursing education. Washington, D.C.: Author; Retrieved from http://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/AcademicNursing/CurriculumGuidelines/Cultural-Competency-Bacc-Edu.pdf?ver=2017-05-18-143551-883 [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association (ANA). (2015). Code of ethics with interpretive statements. Silver Spring, MD: ANA; Retrieved from http://nursingworld.org/DocumentVault/Ethics-1/Code-of-Ethics-for-Nurses.html [Google Scholar]

- Brookfield SD (2012). Teaching for critical thinking: Tools and techniques to help students question their assumptions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Carter LC, Nelson JL, Sievers BA, Dukek SL, Pipe TB, & Holland DE (2008). Exploring a culture of caring. Nursing Administrative Quarterly, 32(1), 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranton P (2006). Understanding and promoting transformative learning: A guide for educators of adults (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) (2016). HHS action plan to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities. https://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdf/hhs/HHS_Plan_complete.pdf

- Diaz C, Clarke P, & Gatua M (2015). Cultural competence in rural nursing education: Are we there yet? Nursing Education Perspectives, 38, 22–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas MK, Rosenkoetter M, Pacquiao DF, Callister LC, Hattar-Pollara M, Lauderdale J, … Purnell L (2014). Guidelines for implementing culturally competent nursing care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 25(2), 109–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudas KI (2012). Cultural competence: An evolutionary concept analysis. Nursing Education Perspectives, 33(5), 317–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finfgeld-Connett D (2008). Meta-synthesis of caring in nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing 17, 196–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01824.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne K, … & Coyne-Beasley T (2015). Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), e60–e76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JM, & Fields B (2013). Continuing the conversation in nursing on race and racism. Nursing Outlook, 61, 164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding J (2013). Qualitative data analysis from start to finish. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Indian Health Service. (2017). Indian health disparities. Retrieved from https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities/

- Johnstone M, & Kanitsaki O (2010). The neglect of racism as an ethical issue in health care. Journal of Immigrant Minority Health, 12, 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman VD (2012). Applying the ethics of care to your nursing practice. Ethics, Law, and Policy, 21(2), 112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancellotti K (2008). Culture care theory: A framework for expanding awareness of diversity and racism in nursing education. Journal of Professional Nursing, 24(3), 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leininger M (2002). Culture care theory: A major contribution to advance transcultural nursing knowledge and practices. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 13(3), 189–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leininger M, & McFarland M (2002). Transcultural nursing: Concepts, theories, research, and practice. New York: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Leininger M, & McFarland M (2006). Culture care diversity and universality: A worldwide nursing theory (2ne ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett. [Google Scholar]

- Lor M, Crooks N, & Tluczek A (2016). A proposed model of person-, family-, and culture-centered nursing care. Nursing Outlook, 64, 352–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow J (Ed.). (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow J, & Taylor E (Eds.). (2009). Transformative learning in practice. Insights from community, workplace, and higher education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Pipe TB (2008). Illuminating the inner leadership journey by engaging intention and mindfulness as guided by caring theory. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 32(2), 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington FB (2005). The concept of intentionality in human science nursing theories. Nursing Science Quarterly, 18(2), 98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, & Beck CT (2004). Nursing research principles and methods (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Scammell JM, & Olumide G (2012). Racism and the mentor-student relationship: Nurse education through a white lens. Nurse Education Today, 32, 545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D (2004). The analysis of semi-structured interviews In Flick U, Von Kardoff E, and Steinke I. A Companion to Qualitative Research. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GR (2007). Health disparities: What can nursing do? Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 8(4). 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus A, & Corbin J (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Suby C (2009). Indirect care: The measure of how we support our staff. Creative Nursing, 15(2), 98–103. doi: 10.1891/1078-4535.15.2.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilki M, Dye K, Markey K, Scholefield D, Davis C, Moore T (2007). Racism: The Implications for nursing education. Diversity in Health and Social Care, 4, 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Upenieks VV, Akhavan J, Kotlerman J, Esser, & Ngo MJ (2007). Value-added care: A new way of assessing staffing rations and workload variability. Journal of Nursing Administration, 37(5), 243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J (2010). Core concepts of Jean Watson’s Theory of Human Caring/Caring Science. Watson Caring Science Institute; Retrieved from https://www.watsoncaringscience.org/files/Cohort%206/watsons-theory-of-human-caring-core-concepts-and-evolution-to-caritas-processes-handout.pdf [Google Scholar]