Abstract

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by defective Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) protein. Morbidity is mainly due to early airway infection. We hypothesized that S. aureus clearance during the first hours of infection was impaired in CF human Airway Surface Liquid (ASL) because of a lowered pH. The ASL pH of human bronchial epithelial cell lines and primary respiratory cells from healthy controls (WT) and patients with CF was measured with a pH microelectrode. The antimicrobial capacity of airway cells was studied after S. aureus apical infection by counting surviving bacteria. ASL was significantly more acidic in CF than in WT respiratory cells. This was consistent with a defect in bicarbonate secretion involving CFTR and SLC26A4 (pendrin) and a persistent proton secretion by ATP12A. ASL demonstrated a defect in S. aureus clearance which was improved by pH normalization. Pendrin inhibition in WT airways recapitulated the CF airway defect and increased S. aureus proliferation. ATP12A inhibition by ouabain decreased bacterial proliferation. Antimicrobial peptides LL-37 and hBD1 demonstrated a pH-dependent activity. Normalizing ASL pH might improve innate airway defense in newborns with CF during onset of S. aureus infection. Pendrin activation and ATP12A inhibition could represent novel therapeutic strategies to normalize pH in CF airways.

Subject terms: Cell biology, Microbiology

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a lethal autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the CF Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) gene encoding for a cAMP-activated anionic channel, secreting mainly chloride (Cl−) and bicarbonate (HCO3−) at the apical surface of epithelia. Most patients are homozygous for p.Phe508del mutation (F508del). The main cause of morbidity and mortality is an obstructive lung disease1,2. This is characterized by exacerbated inflammation and bacterial infection of airway surface liquid (ASL), a thin layer coating the luminal face of the airway epithelium3–6.

ASL bacterial colonization begins within the first hours of life with evidence of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) in airway secretions pointing to impaired local defense. However, the mechanism responsible for this defective bacterial clearance is not clearly understood. Proposed explanations relate to decreased mucociliary clearance7 and abnormal inflammatory responses3, but recent studies also suggested reduced antimicrobial capacity of CF ASL1,8. Studies in newborn pigs with CF highlighted an abnormally low ASL pH in association with defective short-term S. aureus antimicrobial activity1. Restoring normal pH improved the ability to eradicate the bacteria, suggesting that reduced ASL pH is central to disease pathogenesis1. An abnormally low ASL pH might indeed alter local antibacterial defense by impairing mucin hydration and solubilization, resulting in hyper-viscous mucus, which impedes mucociliary clearance9–11. It also reduces the activity of antimicrobial peptides by modulating their native charges1,5,12–15.

The value of ASL pH in patients with CF has been questioned in a recent study which showed similar ASL pH in young children with and without CF16. Most importantly, there is no clear understanding of the initial host response, when S. aureus bacteria infiltrate the pristine surface of the newborn airway, with prolonged time of contact and continuous reseeding from infected mucus plugs. It is therefore crucial to clarify the pathogenesis of these very early steps to counteract the pro-infectious vicious circle and to establish the optimal therapeutic strategy in newborns with CF.

We hypothesized that S. aureus clearance during the first hours of infection is impaired in human CF ASL because of lowered ASL pH. We designed bacterial infection experiments within human airway epithelia to mirror the onset of initial S. aureus infection. We then studied the relationship between local bacterial clearance and ASL pH in WT and F508del homozygous human bronchial epithelial cells, with a specific emphasis on physiologically relevant HCO3− and protons (H+) transporters.

Materials and Methods

Human bronchial epithelial cell cultures

Immortalized CFBE41o− bronchial epithelial cells, with expression of wild-type and F508del-CFTR were provided by Dr. Gruenert17. Human primary bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells were obtained from lobectomies of non-CF donors and lung explants of patients with CF after written informed consent from all the patients. Cells were differentiated and grown at air-liquid interface (ALI) for 3 to 4 weeks, as previously described18. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations described by the Declaration of Helsinki and the Huriet-Serusclat and Jardet law on human research ethics. The study was approved by the Ile de France 2 Ethics Committee.

Measurement of ASL pH with a microelectrode in a controlled atmosphere

To measure ASL pH reliably under physiological conditions, we designed a system with a controlled atmosphere enclosure allowing the regulation and monitoring of gas atmosphere, temperature and hygrometry to maintain physiological ASL conditions (Tech Systèmes, Ris-Orangis, Ile-de-France, France). This enclosure enabled to maintain pCO2 at 5% and temperature at 37 °C.

pH was measured in the controlled enclosure with a micro-combination pH electrode (Thermo Scientific Orion 9810BN, Illkirch, Grand Est, France). The pH microelectrode was calibrated before each experiment with buffer at pH 4 and 7. In a preliminary validation study, we measured the pH values of Ringer’s solutions containing 10 or 25 mM HCO3− in the controlled enclosure at 5% pCO2 and 37 °C after 2 hours incubation. We checked that in this set-up, the measured pH value did not differ by more than 0.03 pH unit from the theoretical one, calculated according to the Henderson Hasselbalch equation, i.e pH = 7.4 for 25 mM HCO3 and pH = 7.1 for 10 mM HCO3.

As the measurements obtained by positioning the pH microelectrode directly in contact to the epithelium were not reproducible, possibly because of epithelium disruption, measurements required the addition at the apical side of the cell culture of 50 µl Ringer’s solution, this volume being the minimal volume to homogeneously cover the filter, and allow reliable measurements.

Respiratory cell cultures were bathed at the basal face with culture medium displaying a 25 mM HCO3− concentration. The solution added at the apical face was a Ringer’s solution (115 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 2.4 mM K2HPO4, 0.4 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM Glucose), whose pH was equilibrated beforehand with 25 mM HCO3− in 5% CO2. This 50 µL solution, representing diluted ASL, was recovered after 15 minutes to 6 hours incubation. pH was measured immediately, directly in the enclosure with a micro-combination pH-electrode. To investigate pH regulation, cell cultures were incubated with a 10 mM HCO3− solution in 5% CO2 (see supplemental material for composition), to mimic a moderate extracellular normocapnic acidosis or with agonists or inhibitors of targeted transporters.

Short-circuit current measurement

Short-circuit current (SCC) was measured under a voltage clamp with an EVC4000 Precision V/I Clamp (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, Florida, United States). Culture inserts with differentiated bronchial epithelial cells were mounted in Ussing chambers (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, California, United States). Experiments were performed at 37 °C, by bubbling epithelia with a pCO2 = 5% and a pO2 = 95%.

For measurements of transepithelial HCO3− secretion, SCC experiments were conducted in an apical and basolateral solution without Cl− and with 25 mM HCO3− (125 mM Na isethionate, 25 mM NaHCO3, 2.4 mM K2HPO4, 0.6 mM KH2PO4, 3.0 mM Ca-gluconate, 2.4 mM Mg-gluconate and 10 mM Dextrose, pH 7.4). During continuous recording of SCC, the following inhibitors and activators were added: the ENaC-channel blocker amiloride (100 µM), cAMP agonists forskolin (10 µM) and IBMX (100 µM) to activate the transepithelial cAMP-dependent current, VX-770 (10 µM) to potentiate CFTR activity, and the specific CFTR inhibitor Inh-172 (5 µM).

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis

qRT-PCR were performed following standard protocols (See Supplemental Material and Supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

ASL antibacterial growth capacity study

S. aureus CIP 76.25 (Collection of lnstitut Pasteur) was cultured in antibiotic-free cell culture medium. Epithelia were apically infected with 50 µL of different inocula. ASL was collected at 2 or 6 hours after incubation at 5% CO2, 37 °C, and plated on Petri dishes. Surviving bacteria were evaluated by counting colony-forming units (CFUs) and expressed as % from inoculum or control condition. To determine effect of ASL pH on bacterial growth, bacterial culture medium was set at various pH by modifying HCO3− concentrations or incubated for 6 hours with 25 µM specific SLC26A4 (pendrin) inhibitor A0119 or 1 mM ATP12A (H+/K+ ATPase) inhibitor ouabain and infected for 2 hours with S. aureus CIP 76.25. S. aureus CIP 76.25 adhesion and internalization capacities on airway epithelium were evaluated by CFU counting and immunostaining20 (See Supplemental Material).

LL-37 and hBD1 antimicrobial peptides antimicrobial capacity study at different pH

S. aureus CIP 76.25 was cultured in antibiotic-free cell culture medium. Bacterial cultures were initiated with OD600 nm = 0.05 and left under agitation at 37 °C, 5% CO2.

To determine the impact of pH change on LL-37 (Invivogen, San Diego, California, United States) or on hBD1 (Eurogentec, Liège, Bruxelles) antimicrobial capacity, bacterial cultures were diluted 2-fold (final inoculum 100,000 CFU/mL) with Ringer’s solutions containing the required HCO3− concentrations to get at pCO2 5% and at 37 °C the following pH values: 7.00, 7.40 and 7.70.

A stock solution of 1 mg/mL LL-37 or hBD1 was prepared in sterile water with 0.02% acetic acid and 0.4% BSA (bovine serum albumin); 5 µL of the LL-37 stock was added to 95 µL of inoculum to obtain a final LL-37 or hBD1 concentration of 50 µg/mL for 2 hours incubation at 5% CO2, 37 °C. Solutions were collected after the 2 hours incubation and plated on Petri dishes. Surviving bacteria were evaluated by CFU counting.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) of each experiment. Statistical significance was assessed by non-parametric Wilcoxon test, Kruskal Wallis test or t-test when appropriate; p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed with StatView software.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Results

pH is abnormally low in the ASL of CF bronchial epithelial cells

In this experimental series, ASL pH was measured at various time intervals after the addition of 50 µL of physiological Ringer’s solution (25 mM HCO3−, 5% CO2) at the apical face of CFBE41o− cell lines and primary cells from 3 F508del homozygote donors and 1 N1303K/4005 + 1G > A patient (Fig. 1A,B). The pH was significantly reduced in CF cells compared to WT cells. This difference was apparent from 15 minutes after addition of Ringer’s solution (Supplemental Fig. 1A) and was significant at 2 hours and 6 hours of incubation in cell lines and primary cells.

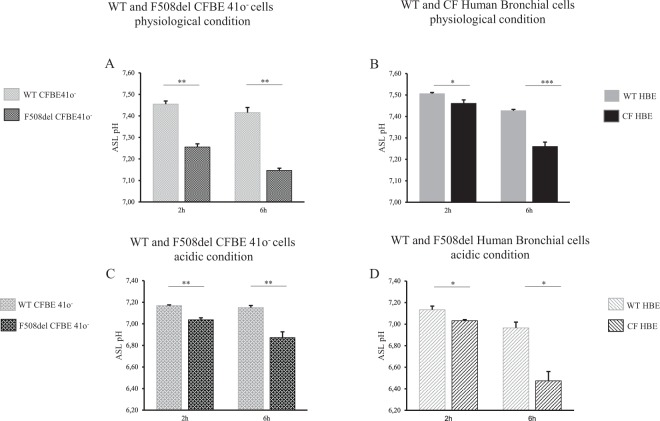

Figure 1.

Airway surface liquid pH measurements under physiological and normocapnic acidosis conditions in WT and F508del bronchial epithelia at 2 and 6 hours. Apical fluid pH was measured after apical addition for 2 hours or 6 hours of 50 µL of physiologic Ringer’s solution (25 mM HCO3−, 5% CO2) (upper panel) or acidic Ringer’s (10 mM HCO3−, 5% CO2) (lower panel). (A) WT vs. F508del CFBE41o− cells. 2 h: pH = 7.45 ± 0.01 vs. pH = 7.26 ± 0.01, p = 0.008; 6 h: pH = 7.42 ± 0.02 vs. pH = 7.15 ± 0.01, p = 0.008. (B) WT vs. CF Human Bronchial Epithelial (HBE) primary cells. 2 h: pH = 7.51 ± 0.004 vs. pH = 7.46 ± 0.02, p = 0.036; 6 h: pH = 7.43 ± 0.006 vs. pH = 7.26 ± 0.02, p < 0.001. (C) WT vs. F508del CFBE41o− cells. 2 h: pH = 7.17 ± 0.01 vs. pH = 7.04 ± 0.02, p = 0.008; 6 h: pH = 7.15 ± 0.02 vs. pH = 6.87 ± 0.05, p = 0.008. (D) WT vs. F508del HBE primary cells. 2 h: pH = 7.13 ± 0.03 vs. pH = 7.03 ± 0.01, p = 0.028; 6 h: pH = 6.97 ± 0.05 vs. pH = 6.47 ± 0.09, p = 0.028. For all conditions, n = 3 in triplicate except for figure B where CF bronchial primary cells were derived from 3 F508del homozygote donors (triplicate for each patient) and 1 N1303K/4005 + 1G > A patient (12 filters). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance from unpaired nonparametric Wilcoxon test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; NS: non significant.

Cells were then subjected to extracellular normocapnic acidosis (10 mM HCO3−, 5% CO2). As expected, ASL pH decreased in both WT and F508del CFBE41o− cell lines, and the ASL pH of CF cultures remained significantly lower than the ASL pH of WT cells (Fig. 1C,D; Supplemental Fig. 1B). These results allowed us to determine that, in physiological conditions, there was a net proton secretion flux in the F508del cells averaging 1.8 µeq/hr/cm2 at 15 minutes in the F508del CFBE41o− cell lines and 4 µeq/hr/cm2 in the F508del HBE cells. Both values are significantly higher than corresponding fluxes in WT cells (See Supplemental results, Supplemental Table 3).

ATP12A-mediated H+ secretion is present in CF and non-CF bronchial epithelial cells

Transcripts of the non-gastric H+/K+ adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) ATP12A, were detected in CFBE41o− and bronchial primary cells of both WT and F508del genotypes (Supplemental Fig. 2).

To evaluate the contribution of ATP12A to ASL pH, 1 mM ouabain was applied on the apical side of the epithelium to selectively inhibit apical ATP12A8. In physiological conditions, ouabain induced a significant alkalinization of the apical fluid both in WT and in F508del HBE (Fig. 2). This increase (~0.1 pH unit) was similar in both genotypes. WT and F508del HBE were then incubated at the basal side in a nominally CO2/HCO3− free solution which was buffered at pH 7.4 with Hepes/NaOH and at the apical side in a nominally CO2/HCO3− free, Hepes free-solution whose pH equilibrated at 7.25. In these conditions, ouabain induced a significant increase in ASL pH in both WT (ΔpH = 0.15; p = 0.01) and F508del CFBE41o− (ΔpH = 0.12; p = 0.01) (Supplemental Fig. 3). This increase in both genotypes was similar to that obtained in physiological conditions.

Figure 2.

Airway surface liquid pH measurements upon ATP12A, NBC1 and SLC26A4 activity inhibition in WT and F508del Human Bronchial Epithelial primary cells. pH changes (ΔpH) in Human Bronchial Epithelial (HBE) primary cells after incubation with vehicle or specific inhibitor are shown in WT HBE cells (grey bars) or F508del HBE (black bars). Apical fluid pH was measured after apical addition of 50 µL of physiologic Ringer’s solution (25 mM HCO3−, 5% CO2) for 2 hours. Ouabain 1 mM (or Ringer as vehicle) was added at the apical side for 2 hours, as ATP12A inhibitor; S0859 100 µM (or DMSO as vehicle) was added at the basal side for 2 hours, as NBC1 inhibitor; A01, 25 µM (or DMSO as vehicle) was added at the basal side for 6 hours, as SLC26A4 inhibitor. Ouabain. WT HBE: ΔpH (Ouabain-Ringer) = 0.095 ± 0.009 (p = 0.002); F508del HBE: ΔpH = 0.09 ± 0.013 (p = 0.028); WT vs. F508del HBE ΔpH: NS. For all conditions, n = 4 in triplicate. S0859. WT HBE: ΔpH (S0859-DMSO) = −0.02 ± 0.014 (NS); F508del HBE: ΔpH = −0.02 ± 0.011 (NS); WT vs. F508del HBE ΔpH: NS. For all conditions, n = 3 in triplicate. A01. WT HBE ΔpH (A01-DMSO) = −0.10 ± 0.022 (p = 0.043); F508del HBE ΔpH = 0.068 ± 0.041 (NS); WT vs. F508del HBE ΔpH: p = 0.04. For all conditions, n = 3 in triplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance from unpaired nonparametric Wilcoxon test. Level of significance is shown for ΔpH in each genotype as well as the comparison between genotypes. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; NS: non significant.

HCO3− secretion is defective in CF epithelial cells and involves CFTR and SLC26A4

Since inhibition of ATP12A-dependent H+ secretion did not fully restore CF ASL pH in CF airway epithelium, we evaluated the contribution of HCO3− transport impairment to explain abnormal ASL pH.

Transcripts of the basolateral Cl−/HCO3− exchanger AE2, the Na+/HCO3− co-transporter NBC1, and the apical Cl−/HCO3− exchanger pendrin were detected by qRT-PCR. AE2 transcript level was not significantly different between WT and F508del CFBE41o−. Pendrin and NBC1 transcripts were significantly more elevated in F508del CFBE41o− or HBE vs. WT cells (Supplemental Fig. 2).

To evaluate the contribution of HCO3− transepithelial secretion to apical pH, we first investigated the basolateral HCO3− uptake. Selective inhibition of NBC1 did not significantly modify ASL pH neither in WT nor in F508del HBE (Fig. 2). NBC1 inhibition slightly decreased ASL pH in WT CFBE41o− cell lines, but there was no change in F508del CFBE41o− (Supplemental Fig. 4).

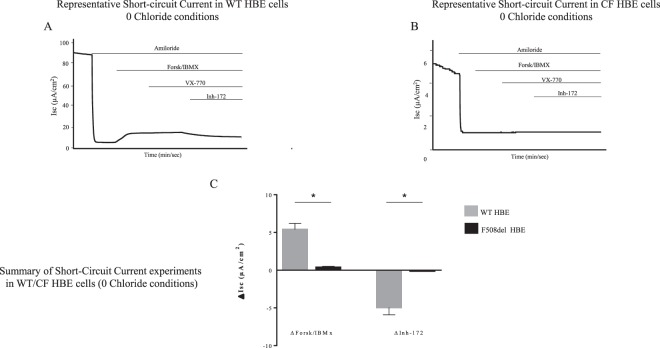

We then investigated the apical transporters involved in HCO3− secretion. The CFTR, cAMP-dependent, HCO3− transport was evaluated by short-circuit current (SCC) in a solution depleted of Cl−. In these conditions, the CFTR-dependent SCC signal is due to the active transport of anions other than Cl−, mainly HCO3−. There was a significant response to forskolin/IBMX in WT primary cells, with a further inhibition by the CFTR inhibitor Inh-172. By contrast, in F508del homozygous primary cells, cAMP stimulation did not induce any HCO3− transport (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Short-circuit current measurements under 0 Chloride conditions in WT and CF Human Bronchial Epithelial primary cells. Experiments were done in a solution with 0 Cl− and 25 mM HCO3−, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at the apical and basal faces. Short-circuit current variation were induced by successive addition of amiloride (100 µM), Forskolin/IBMX (10 µM/100 µM), VX770 (10 µM), Inh-172 (5 µM). (A) Representative experiment from WT Human Bronchial Epithelial (HBE) primary cells. (B) Representative experiment from CF HBE primary cells (N1303K/4005 + 1G > A). (C) Summary of results obtained from 3 WT subjects (n = 3; 14 filters) (grey bars) and 1 CF patient (N1303K/4005 + 1G > A; 2 independent experiments; 7 filters) (black bars). ΔForsk/IBMX: 5.4 ± 0.8 µA/cm2 in WT HBE vs. 0.4 ± 0.1 /cm2 in CF HBE; p = 0.012. ΔInh-172: −4.9 ± 0.97 µA/cm2 in WT HBE vs. −0.1 ± 0.05 µA/cm2 in F508del HBE; p = 0.02. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance from unpaired nonparametric Wilcoxon test. *p < 0.05.

Neither CFTR activation by the forskolin/IBMX cocktail, even under extracellular normocapnic acidosis conditions (Supplemental Fig. 5), nor addition of the specific CFTR inhibitor PPQ-102 (2 µM) (Supplemental Fig. 6), significantly modified ASL pH in the WT CFBE41o− cells. CFTR inhibition by Inh-172, after its preactivation by forskolin and IBMX, induced a significant pH decrease in normocapnic acidosis conditions, showing a significant involvement of CFTR in pH regulation (Supplemental Fig. 7). However, the fact that this pH modulation is observed only in non-physiological acidic conditions, and most importantly, that CFTR activation is not sufficient to restore pH upon mild acidosis (Supplemental Fig. 5) points to the role of other transporters in ASL pH regulation.

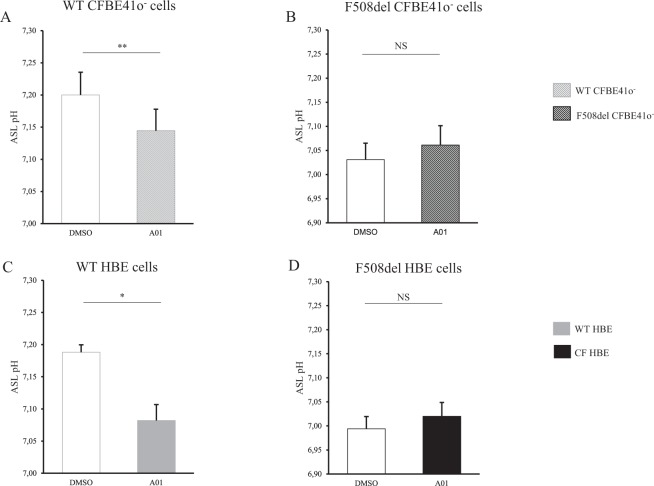

Inhibition of pendrin activity with its specific inhibitor A01 induced a significant ASL acidification in both WT CFBE41o− cell lines and primary cells but not in F508del cells (Figs 2 and 4).

Figure 4.

Airway surface liquid pH measurements upon SLC26A4 inhibition in WT and F508del bronchial epithelia. CFBE41o− cells and Human Bronchial Epithelial (HBE) primary cells were incubated with DMSO vehicle (empty bars) or specific pendrin inhibitor A01 (filled bars) for 6 h. ASL pH was measured after apical addition of 50 µL Ringer’s solution (25 mM HCO3−, 5% CO2). DMSO induces a slight ASL acidification in both WT and F508del cells reaching a decrease of 0.2 pH units after 6 h incubation. (A) WT CFBE41o− cells. pH = 7.20 ± 0.04 (DMSO) vs. pH = 7.14 ± 0.03 (A01), p = 0.008. (B) F508del CFBE41o− cells. pH = 7.03 ± 0.03 (DMSO) vs. pH = 7.06 ± 0.04 (A01), NS. (C) WT HBE primary cells. pH = 7.19 ± 0.01 (DMSO) vs. pH = 7.08 ± 0.02 (A01), p = 0.04. (D) F508del HBE primary cells. pH = 6.99 ± 0.03 (DMSO) vs. pH = 7.02 ± 0.03 (A01), NS. For all conditions, n = 3 in triplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance from unpaired nonparametric Wilcoxon test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; NS: non significant.

Pendrin inhibition by A01 was associated with a significant decrease in the SCC variation in WT HBE cells in response to forskolin/IBMX and Inh-172 (Supplemental Fig. 8). These effects were not detected in F508del cell lines and primary cells (Figs 2 and 4).

S. aureus clearance is defective in ASL of CF respiratory epithelium and is pH-dependent

We first determined the optimal conditions for infection by finding a middle ground between intense bacterial proliferation overwhelming the cells and too low or too short infection period that would not allow us to detect any difference (Supplemental Fig. 9). Those experimental conditions were meant to reflect the bacterial exposition of human CF airways to the environment. As a whole, primary cells displayed a more potent antimicrobial capacity against S. aureus than did CFBE41o−. This is illustrated by the significant decrease in the number of surviving bacteria after 2 h infection with 3,000 CFU/mL S. aureus in WT primary cells, whereas it remained almost stable in WT CFBE41o− (Fig. 5).

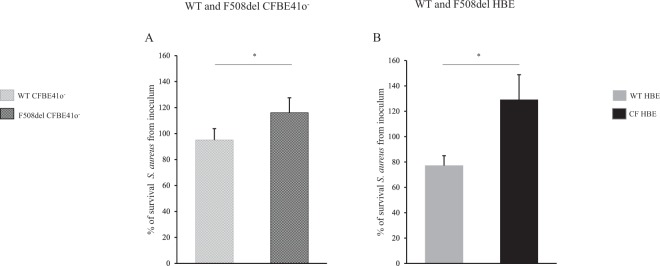

Figure 5.

Clearance of S. aureus CIP 76.25 in airway surface liquid of WT and F508del bronchial epithelia. Epithelia were apically infected with S. aureus CIP 76.25 (3,000 CFU/mL). ASL was collected after 2 hours and plated on Petri dishes to count the surviving bacteria expressed as % from the inoculum. (A) CFBE41o− cells. % of surviving bacteria at 2 h: 95 ± 9% in WT vs. 116 ± 11% in F508del, p = 0.04. For all conditions, n = 5 in triplicate. (B) Human Bronchial Epithelial (HBE) primary cells. % of surviving bacteria at 2 h: 77 ± 8% in WT (n = 9 in triplicate) vs. 129 ± 20% in F508del (n = 3 in triplicate), p = 0.04. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance from unpaired nonparametric Wilcoxon test. *p < 0.05.

Bacterial clearance by ASL was significantly decreased in CF cells vs. WT bronchial epithelial cells. This was observed at 2 hours post-infection in the CFBE41o− cell line and in the primary cells: the percentage of surviving bacteria in CF vs. WT ASL increased 1.5-fold in CFBE41o− cells (Fig. 5A) and 1.7-fold in primary cells (Fig. 5B) after infection with 3.000 CFU/ml. Supplemental Fig. 10 provides bacterial clearance results in conditions maximized to evidence the difference between the WT and the F508del cultures, e.g; 300 CFU/ml 2 h for CFBE41o− and 3,000 CFU/ml 6 hours for primary cells. At 6 hours post-infection with 3,000 CFU/ml, the difference in the primary cell model increased 20-fold (~1.5-fold log increase). We verified that the WT vs. CF difference was not related to a differential S. aureus adhesion or internalization capacity between the WT and CF airway epithelia (Supplemental Fig. 10).

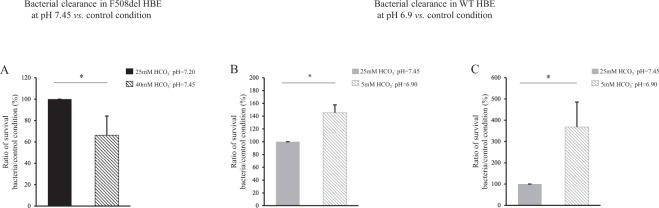

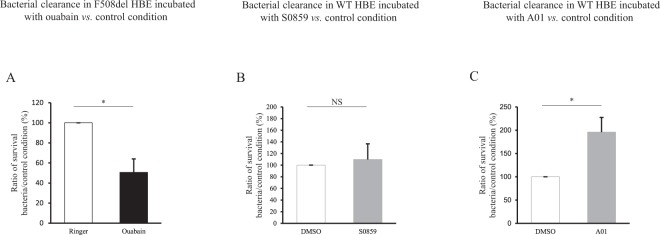

We next investigated whether pH variations could modulate bacterial clearance capacity by varying HCO3− concentrations at constant pCO2, 5%. In CF epithelia, increasing inoculum medium HCO3− concentration to 40 mM normalized infected apical fluid pH from 7.20 to 7.45. This was associated with an improved antimicrobial capacity as evinced by a significant decrease in bacterial survival in primary cells (Fig. 6A). Pharmacological modulation of ASL pH by ouabain in F508del primary cells, which tends to normalize pH, was associated with a significant 2-fold decrease in bacterial proliferation (Fig. 7A).

Figure 6.

Effect of airway surface liquid pH on clearance of S. aureus CIP 76.25 in WT and F508del Human Bronchial Epithelial primary cells. Human Bronchial Epithelial (HBE) primary cells were apically infected with S. aureus CIP 76.25 (3,000 CFU/ml). The apical fluid was collected at the end of the experiments and plated on Petri dishes to count surviving bacteria. To investigate the effect of pH on bacterial clearance, pH of inoculum medium was changed by different HCO3− concentrations. In WT HBE cells, HCO3− concentrations at 5 mM and 25 mM corresponded respectively to a pH of apical supernatant at 6.90 and 7.45. In F508del HBE cells, HCO3− concentrations at 25 mM and 40 mM corresponded respectively to a pH at 7.20 and 7.45. Surviving bacteria detected at the end of experiment in apical fluid under test conditions are expressed as ratio (%) to the control condition of 25 mM HCO3− inoculum solution. (A) F508del HBE cells. % of surviving bacteria after 2 hours in 40 mM HCO3− condition vs. 25 mM HCO3− control condition: 66 ± 18%, p = 0.02. For all conditions, n = 3 in triplicate. (B) WT HBE cells. % of surviving bacteria after 2 hours in 5 mM HCO3− condition vs. 25 mM HCO3− control condition: 145 ± 12%, p = 0.01. For all conditions, n = 3, 4 filters per experiment. (C) WT HBE cells. % of surviving bacteria after 6 hours in 5 mM HCO3− condition vs. 25 mM HCO3− control condition: 368 ± 117%, p = 0.01. For all conditions, n = 3 in triplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance from unpaired nonparametric Wilcoxon test. *p < 0.05.

Figure 7.

Effect of pH pharmacological modulation on clearance of S. aureus CIP 76.25 in airway surface liquid of WT and F508del Human Bronchial Epithelial primary cells. Human Bronchial Epithelial (HBE) primary cells were apically infected with S. aureus CIP 76.25 (3,000 CFU/ml) for 2 hours previously incubated with specific transporter inhibitors or vehicle. The apical fluid was collected at the end of the experiments and plated on Petri dishes to count surviving bacteria. Bacteria detected under test conditions were expressed as ratio to the control condition. (A) F508del HBE cells incubated with ouabain 1 mM, as ATP12A inhibitor vs. Ringer for 2 hours. % of surviving bacteria from inoculum: 50.6 ± 13%, p = 0.046. For all conditions, n = 2 in triplicate. (B) WT HBE cells incubated with S0859 100 µM, as NBC inhibitor, vs. DMSO for 2 hours. % of surviving bacteria from inoculum: 109.7 ± 27%, NS. For all conditions, n = 2 in triplicate. (C) WT HBE cells incubated with A01 25 µM, as SLC26A4 inhibitor, vs. DMSO for 6 hours. % of surviving bacteria from inoculum: 196 ± 32%, p = 0.028. For all conditions, n = 2 in triplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance from unpaired nonparametric Wilcoxon test. *p < 0.05; NS: non significant.

In WT cells, decreasing the pH of the apical supernatant to 6.9 (5 mM HCO3−) significantly increased the number of surviving bacteria at 2 hours (Fig. 6B) and 6 hours (Fig. 6C). Inhibition of NBC1 activity did not induce any change in ASL antimicrobial capacity (Fig. 7B). In contrast, application of pendrin inhibitor A01 was associated with a significant overgrowth of S. aureus in primary cells (Fig. 7C) as well as in WT CFBE41o− (Supplemental Fig. 12). Control experiments checked that neither pH change, nor ouabain, nor A01 affected bacterial growth (data not shown).

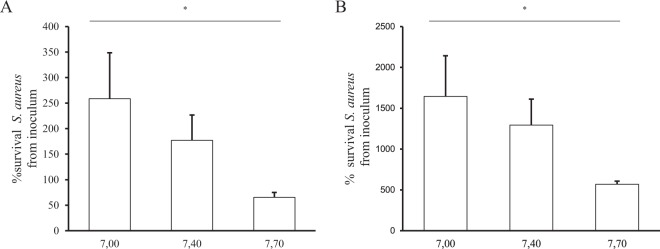

pH-dependent LL-37 and hBD1 antimicrobial capacities against S. aureus

To investigate whether enhancement of bacterial proliferation in CF airways was related to a defect in the antimicrobial peptides hBD1, hBD2 and LL-37, we first measured their expression (mRNA) and showed no difference in either CFBE41o− cells or primary cells independently of the genotype (WT or F508del) (Supplemental Fig. 13). Transcript levels did not change with pH when pH variations were similar to those observed between CF and WT epithelia (Supplemental Fig. 14).

We then tested how modification of pH may affect the activity of these antimicrobial peptides. As shown in Fig. 8A,B, LL-37 and hBD1 displayed significant pH-dependent antimicrobial activity at small pH variations, comparable to ASL pH differences observed between WT and CF epithelia.

Figure 8.

LL-37 and hBD1 antimicrobial capacities against S. aureus CIP 76.25 at different pH. LL-37 and hBD1 antimicrobial peptides were incubated at 50 µg/mL for 2 h with 100,000 CFU/mL of S. aureus CIP 76.25 in culture medium at pH = 7,00; 7.40 and 7.70. Solutions were plated at the end of the experiments on Petri dishes to count the surviving bacteria. Surviving bacteria are expressed as % from the inoculum under different conditions. (A) LL-37 activity evaluated at: pH = 7.00 (3 different cultures in duplicate), 7.40 (2 different cultures in duplicate) and 7.70 (n = 3 in duplicate), p = 0.01. (B) hBD1 activity evaluated at: pH = 7.00, 7.40 and 7.70, p = 0.03. For all conditions, n = 2 in duplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance from unpaired nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test. *p < 0.05.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that ASL pH is significantly lower in primary cultures of airway cells obtained from patients with CF than those from healthy controls. This abnormal acidification is related to a defect in cAMP-dependent HCO3− secretion involving both CFTR and pendrin, concomitant with persistent H+ secretion by ATP12A. Our experiments confirm that ASL pH is a key factor for S. aureus clearance from airways and that small pH variations, similar to those observed between CF and WT, modulate LL-37 and hBD1 antimicrobial peptide activity. Very importantly, our data show that inhibition of pendrin activity in WT airways recapitulates both the CF acidification and antimicrobial defect and that inhibition of ATP12A activity in CF epithelia improves pH regulation and significantly improves bacterial clearance.

Technical challenges

To face the technical challenge of measuring pH in epithelial cell culture models, measurements were made under steady-state conditions to mirror the in vivo airway microenvironment. This was achieved by using a humidified enclosure to avoid evaporation of the small ASL volume and allow control of CO2 content and temperature.

pH measurements were performed after at least 2 hours of incubation, as a compromise between the conditions needed for bacterial measurements (risk of bacterial overgrow after 2 hours) and the delay necessary for pH equilibration.

Because of the above limitations, instead of considering absolute values, we assessed the changes in the pH of this apical fluid and assumed that the latter reflected the changes in ASL pH. Therefore, our experimental strategy focused on the comparison between the 2 genotypes. Finally, because pH variations can not discriminate between H+ and HCO3− transport we used pharmacological modulation of targeted transport to investigate the pathways of pH regulation in ASL.

ASL pH regulation in CF airways and considerations on the specific role of pendrin

In line with previous studies21,22, we found that the ASL pH of CF epithelium was lower than that of WT epithelium, both in the F508del CFBE41o− cell line and in HBE primary cells from patients. Importantly, CF cells could not compensate for acidosis, in contrast to WT cells, suggesting a defect in pH homeostasis in CF.

Other studies, however, reported that airway surface is not more acidic in patients with CF23,24. For example, a recent study based on the use of a pH-sensitive luminescent dye-based fiber-optic probe in vivo did not show any pH difference between CF and non-CF infants16. Those differences might be related to the methodology (fiber optic probe vs. microelectrode), the model used (in vivo, during breathing vs. primary culture devoid of any shear stress) but also the time of measurements, as they were performed at steady state in our study vs. immediately after positioning of the probe in the above study.

Importantly in the other study16, the mean age of the children was 50 (12–78) months, an age where the disease has probably already evolved, including abnormal mucus production and initiation of pro-inflammatory conditions, which might modify HCO3− and H+ transporter expression levels or activity. In contrast, our model evaluates ASL virtually free of any inflammation and mucus, which very probably sets a different physio-pathological context and possibly alters transporter function. Although it can be argued that our model is artificial, we point out that it reflects the condition of the pristine neonate airways, devoid of any infection and probably inflammation-free, to best unravel the defects favoring the initial S. aureus colonization, according to our study’s hypothesis. This might therefore explain the resultant difference and accords with recent findings in the pig model where pH is lower in CF piglets at birth but tends to normalize after 3 weeks of life25. Clearly further studies are needed to clarify the discrepancies between studies and models.

In the present study, ATP12A inhibition induced a significant pH increase, at a similar level in both WT and CF airway epithelia. This points to the possible role of persistent H+ secretion in CF airways in ASL acidosis, in contrast to the WT cells where this secretion is counterbalanced by CFTR-dependent HCO3− secretion, as already reported by Shah et al.8.

The fact that in mild acidic conditions in a nominally CO2/HCO3− free, Hepes free-solution, ASL pH was not restored to WT values after ATP12A inhibition by ouabain demonstrates that ASL acidification in CF airways results from the coupling of persistent H+ secretion with a HCO3− secretion defect. Our data show that inhibiting basolateral HCO3− transport via NBC1 has a limited effect on ASL pH, suggesting that NBC1 might act indirectly as a limiting factor for HCO3− secretion and ASL pH regulation.

We hypothesized a critical role of the CFTR-dependent HCO3− secretion in ASL pH homoeostasis. In support, cAMP activated an electrogenic HCO3− apical transport in the absence of Cl− in WT airways, whereas this was defective in CF airways. This was indicated by IsC changes in response to cAMP in a solution depleted of Cl−. This confirms previous reports showing that apical HCO3− secretion is reduced when CFTR is absent26–28. However, it was impossible to discern in our model any ASL pH variations in WT or F508del cells after Forskolin/IBMX treatment and CFTR inhibition in physiological conditions. The CFTR effect on pH variation was unmasked by Inh-172 CFTR-specific inhibition only in normocapnic acidosis, whereas CFTR activation by itself was not sufficient to restore pH upon mild acidosis. This suggests that ASL HCO3− content and pH homeostasis involve transporters other than CFTR. Our results show that pendrin, an electroneutral anion exchanger, contributes to ASL pH regulation, and point to its functional defect in the context of the F508del genotype in epithelial respiratory cells19,29–31. Indeed, pendrin has an important role in airways for ASL hydration and has already been involved in asthma and other inflammatory airway diseases30,32–35.

We demonstrate for the first time pendrin dysfunction in the context of CFTR mutations and suggest a possible relevance in the field of CF physiopathology. Importantly, pendrin seems more potent than CFTR in regulating pH ASL, as its inhibitor is able to decrease pH by ~0.1 pH unit, and HCO3− related IsC variation upon forskolin by a factor of ~2. It can be hypothesized that CFTR is important to provide the Cl− ions necessary for HCO3−/Cl− exchange by pendrin. Thus, lack of Cl− in the context of CFTR dysfunction leads to decreased pendrin activity. Our data concur with those of Garnett et al., whose results suggested that pendrin regulates ASL pH by exchanging Cl− with HCO3− 23. Another explanation is that pendrin may also interact with CFTR with a reciprocal functional activation process, which may be defective in the context of CFTR mutation, similarly to what has been described for SL26A325 or A936. Therefore, pendrin inhibition would impact CFTR activity, including HCO3− cAMP-dependent secretion as shown by IsC. Our results conflict with those of Haggie et al. who observed no significant ASL acidification in WT and F508del primary cells by pendrin activity inhibition in the absence of an inflammatory context19,37. This discrepancy may be related to experimental conditions and semi-quantitative pH measurements which may not have been sensitive enough to capture small variations in pH, as well as different levels of pendrin expression which is very sensitive to culture conditions and pro-inflammatory stimuli.

Taken together, our data show that abnormally low ASL pH in CF airways involves reduced HCO3− secretion by defective CFTR and inactivated pendrin in the presence of remaining H+ secretion by ATP12A. Those results are however cell type-specific as recently pointed out by a recent study demonstrating that most HCO3− secretion by Calu-3 cells was mediated by CFTR27.

Defective antimicrobial capacity in CF airways is related to ASL acidification

Our study set out to investigate in the human model the pattern of initial bacterial proliferation by S. aureus during the first hours of infection after bacterial seeding, to gain more insight into the innate immunity of CF airways. We designed an experimental protocol to closely mimic the infection conditions in airways, including very low amounts of S. aureus, reflecting what naturally occurs during the initial steps of airway colonization by S. aureus. In these conditions, we observed a significantly increased growth of S. aureus in the CF epithelium. We checked that the deficient antimicrobial capacity of CF airways was exclusively related to the impaired ASL host defense as only the conditions with a very high bacteria charge detected a low level of intracellular invasion, which does not correspond to a physiological state. Most importantly, our results in the human respiratory model demonstrated that this impaired host defense is pH-dependent. Increasing CF ASL pH improved its antimicrobial capacity, and conversely, decreasing ASL pH in WT epithelium recapitulated the defective bacterial clearance of CF airways. Importantly, an ouabain-induced increase in CF ASL pH, by as little as 0.1 pH unit, was able to decrease significantly bacterial proliferation.

Moreover, inhibition of H+/K+ ATPase might be clinically relevant in situations of acidic inhalations due to gastro-esophageal reflux. Indeed we show that decreasing pH to 6.9, a value far above gastric pH (usually at 4), is associated with an enhancement of bacterial proliferation. This defect is amplified by the fact that CF cells can not compensate for mild acidic stress.This points to the potential involvement of H+/K+-ATPase in the physiopathology of initial infection, as reported by Shah et al.8.

Very importantly, we also show the potential involvement of pendrin in airway bacterial clearance, as its specific inhibition in WT airways induces a CF-like bacterial clearance defect. Pendrin seems to present a functional defect in the context of the F508del genotype. A pendrin activator that would increase HCO3− secretion might be an interesting strategy for ASL pH regulation.

Such data also illustrate that very small variations in pH may be physiologically relevant for antimicrobial airway activity. Indeed, we observed the modulation of LL-37 and hBD1 antimicrobial activities at small pH variations, in the range of ASL pH differences observed between WT and CF epithelia. This may be explained by the modification of the electrical charge of antimicrobial peptides under small pH variations, and thus the modulation of their conformation, a key point in their antimicrobial properties5,13,14. The defect observed for each peptide individually may occur synergistically in ASL where peptides are expressed simultaneously.

If initiated very early, such a therapeutic strategy could therefore counteract the very first steps of the disease on pristine airways of neonates. Inhibiting S. aureus airway infection would then limit the pro-inflammatory cascade aggravated by infection. How ASL pH could be normalized is still unknown. As HCO3− aerosolization effects are transient, it would be more effective to increase ASL pH sustainably. This might be achieved by various drugs that buffer mucus, even though this might modify the physiological balance of acid/base regulation of the airway epithelia. Moreover, as CF cells can not compensate for acidic challenges, control of acidic gastro-esophageal reflux is crucial. Importantly, our results suggest that pendrin activation might offer a novel strategy, by triggering ASL alkalization38, possibly in combination with ATP12A inhibitors39,40, which should be further investigated.

Conclusion

We report evidence for defective bacterial clearance of S. aureus in human CF airways. Our results support that the reduced pH observed in CF ASL is central to innate immune defense. This adds a new mechanism by which impaired ASL properties in CF promote microbial infection. Our data strongly suggest that CF cells fail to properly regulate pH variations, and demonstrate a potential role for pendrin and ATP12A in pH-dependent bacterial clearance capacity. Translating this understanding into early ASL pH normalization is now an exciting challenge, with prospects for improved clinical care.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Alan Verkman for the kind gift of specific CFTR and pendrin inhibitors and Pr. Lucie Jeannotte for reading the manuscript. The last part of the project is funded through Vertex Innovation Award (VIA) which is an unconditional research grant provided by Vertex Pharmaceuticals (Europe) Limited. Equipment funding. supported by University Paris Descartes. Gifts of the CFTR PPQ-102 and pendrin A01 inhibitors by Dr. Alan Verkman.

Author Contributions

J.S.: co-designed the study, designed the controlled atmosphere enclosure enabling pH measurements, conducted and acquired all experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. E.B.: participated to the design and interpretation of the infection experiments. G.C.: conducted qRT-PCR experiments, interpreted pH experiments. S.N.: participated to pH measurements. E.D.: participated to antimicrobial capacities evaluation. A. Edw.: conducted flux protons evaluation. A. Ha.: conducted primary cells culture and short-circuit current experiments. I.P.: conducted primary cells culture. B.V.: conducted and interpreted qRT-PCR experiments. CH. C.: participated to the production of the controlled atmosphere enclosure. N.B.: participated to the primary cells culture. CH. C., J.P. V., A. Hi., A.G., L.T., X.N., VU., L.G; G.P.: participated to the interpretation of data. JM. S.: conducted qRT-PCR experiments, interpreted experiments. A. Ede.: participated to the conception of the study, interpretation of data, and writing. I. SG.: designed the study, participated to the design of the controlled atmosphere enclosure, analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Aleksander Edelman and Isabelle Sermet-Gaudelus jointly supervised this work.

Change history

11/21/2019

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-42751-4.

References

- 1.Pezzulo AA, et al. Reduced airway surface pH impairs bacterial killing in the porcine cystic fibrosis lung. Nature. 2012;487:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature11130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith JJ, Travis SM, Greenberg EP, Welsh MJ. Cystic fibrosis airway epithelia fail to kill bacteria because of abnormal airway surface fluid. Cell. 1996;85:229–236. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen TS, Prince A. Cystic fibrosis: a mucosal immunodeficiency syndrome. Nat. Med. 2012;18:509–519. doi: 10.1038/nm.2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sly PD, et al. Lung disease at diagnosis in infants with cystic fibrosis detected by newborn screening. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009;180:146–152. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0069OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang XX, et al. Lymphocyte CFTR promotes epithelial bicarbonate secretion for bacterial killing. J. Cell. Physiol. 2012;227:3887–3894. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verrière V, et al. Lipoxin A4 stimulates calcium-activated chloride currents and increases airway surface liquid height in normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. PloS One. 2012;7:e37746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gustafsson JK, et al. Bicarbonate and functional CFTR channel are required for proper mucin secretion and link cystic fibrosis with its mucus phenotype. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:1263–1272. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah VS, et al. Airway acidification initiates host defense abnormalities in cystic fibrosis mice. Science. 2016;351:503–507. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinton PM. [No Title] Nat. Med. 2001;7:292–293. doi: 10.1038/85429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quinton PM. Cystic fibrosis: impaired bicarbonate secretion and mucoviscidosis. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2008;372:415–417. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quinton PM. Role of epithelial HCO3− transport in mucin secretion: lessons from cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C1222–1233. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00362.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alba A, López-Abarrategui C, Otero-González AJ. Host defense peptides: an alternative as antiinfective and immunomodulatory therapeutics. Biopolymers. 2012;98:251–267. doi: 10.1002/bip.22076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehrer RI, Selsted ME, Szklarek D, Fleischmann J. Antibacterial activity of microbicidal cationic proteins 1 and 2, natural peptide antibiotics of rabbit lung macrophages. Infect. Immun. 1983;42:10–14. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.10-14.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson KD, Welykyj S, Massa MC. Antibacterial activity of lidocaine in combination with a bicarbonate buffer. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 1993;19:216–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1993.tb00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie C, et al. A host defense mechanism involving CFTR-mediated bicarbonate secretion in bacterial prostatitis. PloS One. 2010;5:e15255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schultz A, et al. Airway surface liquid pH is not acidic in children with cystic fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1409. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00532-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruenert DC, et al. Characterization of human tracheal epithelial cells transformed by an origin-defective simian virus 40. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:5951–5955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pranke IM, et al. Correction of CFTR function in nasal epithelial cells from cystic fibrosis patients predicts improvement of respiratory function by CFTR modulators. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:7375. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07504-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haggie PM, et al. Inhibitors of pendrin anion exchange identified in a small molecule screen increase airway surface liquid volume in cystic fibrosis. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2016;30:2187–2197. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600223R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trouillet S, et al. A novel flow cytometry-based assay for the quantification of Staphylococcus aureus adhesion to and invasion of eukaryotic cells. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2011;86:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coakley RD, et al. Abnormal surface liquid pH regulation by cultured cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:16083–16088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2634339100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garland AL, et al. Molecular basis for pH-dependent mucosal dehydration in cystic fibrosis airways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:15973–15978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311999110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garnett JP, et al. Novel role for pendrin in orchestrating bicarbonate secretion in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-expressing airway serous cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:41069–41082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.266734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McShane D, et al. Airway surface pH in subjects with cystic fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2003;21:37–42. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00027603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ko SBH, et al. Gating of CFTR by the STAS domain of SLC26 transporters. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:343–350. doi: 10.1038/ncb1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray MA. Bicarbonate secretion: it takes two to tango. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:292–294. doi: 10.1038/ncb0404-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang, J. et al. Most bicarbonate secretion by Calu-3 cells is mediated by CFTR and independent of pendrin. Physiol. Rep. 6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Shan J, et al. Bicarbonate-dependent chloride transport drives fluid secretion by the human airway epithelial cell line Calu-3. J. Physiol. 2012;590:5273–5297. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.236893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mount DB, Romero MF. The SLC26 gene family of multifunctional anion exchangers. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:710–721. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nofziger C, Dossena S, Suzuki S, Izuhara K, Paulmichl M. Pendrin function in airway epithelia. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011;28:571–578. doi: 10.1159/000335115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scantamburlo G, et al. Interleukin-4 Induces CpG Site-Specific Demethylation of the Pendrin Promoter in Primary Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017;41:1491–1502. doi: 10.1159/000470720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakagami Y, et al. The epithelial anion transporter pendrin is induced by allergy and rhinovirus infection, regulates airway surface liquid, and increases airway reactivity and inflammation in an asthma model. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2008;181:2203–2210. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scanlon KM, et al. Epithelial anion transporter pendrin contributes to inflammatory lung pathology in mouse models of Bordetella pertussis infection. Infect. Immun. 2014;82:4212–4221. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02222-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakao I, et al. Identification of pendrin as a common mediator for mucus production in bronchial asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950. 2008;180:6262–6269. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seshadri S, et al. Increased expression of the epithelial anion transporter pendrin/SLC26A4 in nasal polyps of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;136:1548–1558.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bakouh N, et al. Characterization of SLC26A9 in patients with CF-like lung disease. Hum. Mutat. 2013;34:1404–1414. doi: 10.1002/humu.22382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cil O, Haggie PM, Phuan P-W, Tan J-A, Verkman AS. Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Pendrin Potentiate the Diuretic Action of Furosemide. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN. 2016;27:3706–3714. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015121312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garnett JP, Hickman E, Tunkamnerdthai O, Cuthbert AW, Gray MA. Protein phosphatase 1 coordinates CFTR-dependent airway epithelial HCO3− secretion by reciprocal regulation of apical and basolateral membrane Cl(-)-HCO3− exchangers. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013;168:1946–1960. doi: 10.1111/bph.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scudieri, P. et al. Increased expression of ATP12A proton pump in cystic fibrosis airways. JCI Insight3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Delpiano L, et al. Esomeprazole Increases Airway Surface Liquid pH in Primary Cystic Fibrosis Epithelial Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:1462. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.