Abstract

Choroid plexus epithelial cells (CPECs) secrete cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). They express Na+-K+-ATPase and Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) on their apical membrane, deviating from typical basolateral membrane location in secretory epithelia. Given this peculiarity, the direction of basal net ion fluxes mediated by NKCC1 in CPECs is controversial, and cotransporter function is unclear. Determining the direction of basal NKCC1-mediated fluxes is critical to understanding the function of apical NKCC1. If NKCC1 works in the net efflux mode, it may be directly involved in CSF secretion. Conversely, if NKCC1 works in the net influx mode, it would have an absorptive function, contributing to intracellular Cl− concentration ([Cl−]i) and cell water volume (CWV) maintenance needed for CSF secretion. We resolve this long-standing debate by electron microscopy (EM), live-cell-imaging microscopy (LCIM), and intracellular Na+ and Cl− measurements in single CPECs of NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− mouse. NKCC1-mediated ion and associated water fluxes are tightly linked, thus their direction is inferred by measuring CWV changes. Genetic or pharmacological NKCC1 inactivation produces CPEC shrinkage. EM of NKCC1−/− CPECs in situ shows they are shrunken, forming large dilations of their basolateral extracellular spaces, yet remaining attached by tight junctions. Normarski LCIM shows in vitro CPECs from NKCC1−/− are ~17% smaller than NKCC1+/+. CWV measurements in calcein-loaded CPECs show that bumetanide (10 μM) produces ~16% decrease in CWV in NKCC1+/+ but not in NKCC1−/− CPECs. Our findings suggest that under basal conditions apical NKCC1 is continuously active and works in the net inward flux mode maintaining [Cl−]i and CWV needed for CSF secretion.

Keywords: apical NKCC1, cell volume, choroid plexus epithelial cells, NKCC1−/−, ultrastructure

INTRODUCTION

The choroid plexuses (CPs) are highly vascularized epithelial structures that reside in the brain ventricles, where they float in the surrounding cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) they secrete. Forming the blood-CSF barrier, CPs are composed of a monolayer of cuboidal epithelial cells held together by junctional complexes at their apical side and surrounding a core of fenestrated capillaries facing the basolateral membrane (68). Choroid plexus epithelial cells (CPECs) secrete most of the CSF and regulate its ionic composition through poorly understood mechanisms (9, 71). CPECs are unique among Cl− secretory epithelial cells because the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter NKCC1 (SLC12A1) and the Na+-K+ transporting adenosine triphosphatase (Na+-K+-ATPase) are located on their apical membrane (CSF-facing), deviating from typical basolateral membrane (blood-facing) location (3, 15). Given this noncanonical location, NKCC1 function in CPECs is not understood, and the direction of net ion fluxes mediated by this cotransporter and associated water fluxes under basal physiological conditions is controversial (10, 28, 71).

Understanding NKCC1 function in CPECs is clinically relevant because this protein and the kinases involved in its regulation are potential pharmacological targets to control CSF secretion (52, 103, 105). Pharmacological tools for modulation of CSF secretion are critically needed for the treatment of neurological disorders in which there is an uncontrolled increase in intracranial pressure, such as idiopathic intracranial hypertension (38), hydrocephalus (43, 44), and traumatic and ischemic brain injury (12, 51). If under basal physiological conditions NKCC1 works in the net efflux mode, it may be directly involved in CSF secretion as suggested by some investigators (36, 46, 72, 81, 91, 92). Two sets of observations have been taken as evidence backing up this hypothesis: first, intraventricular bumetanide, an inhibitor of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporters (NKCCs), significantly reduces CSF secretion; and, second, estimated intracellular Na+ is higher in CPECs than in other epithelial cells, making NKCC1-mediated net ion efflux thermodynamically feasible.

The evidence for the first assumption originated from experiments showing that intraventricular bumetanide in canines significantly reduced (50%) CSF secretion (35) and Cl− fluxes associated with CSF secretion (37). In these early studies, NKCC was assumed to be localized to the basolateral membrane of CPECs (34), contributing to CSF secretion as in the classic models of Cl− secretory epithelia (23, 24, 87, 88). A new study shows that intraventricular bumetanide (100 µM) in mice decreases CSF production by ~50%, confirming earlier observations in canines (92). The second argument proposed for NKCC1 working in the net efflux mode stems from estimates of intracellular Na+ concentration ([Na+]i) in CPECs, derived from whole CP tissue measurements (36, 46, 62, 90, 92). The relatively high estimates of [Na+]i (30–50 mM) and the observations that bumetanide (10–30 µM) causes 75% inhibition of K+ efflux in rat CP in vitro and that cerebroventricular bumetanide inhibits CSF and Cl− secretion at concentrations of 100 and 10 µM, respectively (35, 37), have been taken together as functional evidence for an apical NKCC that contributes to CSF secretion by working in the net efflux, secretory, mode (46, 92).

Following the cloning of NKCCs, it was definitely established that the cotransporter expressed in CP was NKCC1 (70). Immunolabeling microscopy revealed that NKCC1 was located to the apical membrane of rat (70), mouse (69), and human CPECs (72). This finding required a total reappraisal of the mechanism of CSF secretion and the functional role of apical NKCC1 in this Cl− secretory epithelium. The debate about the directionality of NKCC1-mediated net solute fluxes reached a high point with the proposal by Wu and coworkers (98) that apical NKCC1 is “constitutively active” and mediates net influx of ions in CPECs. They proposed that NKCC1 functions as a K+-reabsorption mechanism from CSF to blood. Accordingly, inhibition of NKCC1 should produce shrinkage of CPECs due to unbalanced solute and water efflux pathways. They tested these hypotheses using isolated single CPECs from rat and estimating cell volume changes by differential interference contrast (DIC) measurement of cross-sectional areas (CSAs). They found that bumetanide at high concentrations (100 µM) caused a 9% decrease in cell volume, whereas increasing external K+ concentration to 25 mM produced a 33% increase in cell volume that was blocked by bumetanide (100 µM) or external Na+ removal.

The experiments of Wu and coworkers (98) have been criticized because of the high concentration of bumetanide used, which, admittedly, can have effects in other transporters expressed in the CP (10). The possibility of nonspecific actions of bumetanide was tested by Brown and coworkers (10, 30). They concluded that the decrease in cell volume reported by Wu and coworkers (98) could be replicated using bumetanide at concentrations of 100 µM but not at 10 µM (10, 30), a concentration known to produce selective and complete block of NKCC1 (3, 83). Thus, based on their results, Brown and coworkers (10, 30) questioned the conclusions of Wu et al. (98) regarding a role of NKCC1 in cell volume maintenance.

In the present study, we address the apical NKCC1 debate reviewed above, by using a combined methodological approach in dissociated CPECs and in in situ CP of NKCC1 knockout (KO) models. Changes in cell water volume (CWV) were measured in single CPECs loaded with the fluorescent dye calcein, a live-cell-imaging fluorescence microscopy method that, unlike DIC, is independent of changes in cell shape and allows “real-time” measurements of CWV in single CPECs with time resolution of <1 Hz and sensitivity of ~1% (4, 5, 14, 79). Intracellular Na+ and Cl− concentrations were measured in single CPECs with fluorescent indicators. DIC live-cell images were also used to measure steady-state CSAs and immunoelectron microscopy was used to determine the subcellular location of NKCC1. Our results show that genetic and pharmacological inactivation of apical NKCC1 produces significant shrinkage of choroid plexus epithelial cells, both in vitro and in situ. Measured [Na+]i and [Cl−]i energetically favor NKCC1 net solute uptake under basal conditions. Inactivation of NKCC1 results in a significant decrease in [Cl−]i. Taken together, these results demonstrate that under basal physiological conditions the cotransporter is continuously active and works in the net inward flux mode maintaining cell water volume and [Cl−]i needed for CSF secretion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Husbandry, Treatment, Euthanasia, and Tissue Collection

The use and handling of all animals in this study were approved by the Wright State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, in accordance with the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Two NKCC1−/− mouse lines were used. One line was generated by deletion of exon 9 of the Slc12a2 gene on C57 black background animals (17). These animals were kindly donated by Prof. Eric Delpire (Vanderbilt University School of Medicine) and were used for electron microscopy (EM) and initial immunolabeling studies. The second line, on a 129 Black Swiss mixed background, came from a colony raised at Wright State University Laboratory Animal Resources facility from breeding pairs generously donated by Prof. Gary Shull (University of Cincinnati College of Medicine). Mice from this colony lacked exon 6 of the Slc12a2 gene (22). These animals were also used in some immunofluorescence experiments and in all of the functional experiments described in this study.

Animals were housed in an American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (now Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International)-certified facility, and procedures were completed in accordance with federal guidelines and regulations. Food (Teklad; Envigo, Madison, WI) and tap water were provided ad libitum with water removed at the time of the experiment. Aspen chip bedding (Teklad; Envigo) and nesting material (Nestlets; Ancare, Bellmore, NY) were provided. Lighting was maintained on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle, and ambient temperature was maintained at 23.3 ± 2.2°C. It has been reported that NKCC1−/− mice exhibit hyposalivation in response to muscarinic agonists (21). This condition might become a problem after weaning. To avoid this potential discomfort, most animals were used on or before postnatal day 21 (P21). Animals older than P21 were supplied with moist food after weaning.

To optimize tissue preservation for immunofluorescence and EM microscopy studies, fixation was done in animals that were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg ip). In subsequent histological experiments, animals were anesthetized with Euthasol (pentobarbital sodium and phenytoin sodium), injected intraperitoneally (270 mg/kg). In all cases, deep anesthesia was continuously monitored before thoracotomy, exsanguination, and perfusion. Depth of anesthesia was assessed regularly by testing withdrawal reflexes by pinching of the toes, ears, and tail. Mice for experiments on dissociated CPECs, or those in excess/ill/moribund, were euthanized by CO2 anesthesia followed by decapitation, in accordance with AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2013 Edition (American Veterinary Medical Association, Schaumburg, IL).

Antibodies and Immunofluorescence Microscopy

For immunofluorescence microscopy, deeply anesthetized animals were perfused transcardially with 200 ml of 2–4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.3. The brain and other tissues were extracted and postfixed for 1–2.5 h in the same fixative solution and stored at 4°C in 0.1 M PBS with 15% sucrose until used. Frozen sections (cryostat, 20 µm thick or freezing sliding microtome, 50 µm thick) were collected on gelatinized slides (cryostat) or processed free floating (freezing sliding). After wash (3 × 5 min) in 0.01 M PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBS-T; pH 7.4), sections were blocked with 10% normal donkey or horse serum for 60 min and incubated overnight at 4°C with the corresponding primary antibodies diluted in PBS-T. For detection of NKCC1, we used an affinity-purified polyclonal antibody raised in rabbits against a fusion protein fragment encompassing amino acids 938–1,011 of the carboxy terminus (CT) of mouse NKCC1 (41). We refer to this antibody provided by Prof. Delpire as Kaplan-CT. It recognizes both NKCC1 variants, long (NKCC1a) and short (NKCC1b), when tested with maltose-binding fusion proteins with or without exon 21 (56).

The specificity of the Kaplan-CT antibody toward NKCC1 has been thoroughly validated in NKCC1−/− tissues, including choroid plexus epithelium (56, 69, 93). In the present study, we verified once more that NKCC1 immunoreactivity detected with this antibody in the apical membrane of NKCC1+/+ CPECs disappeared in NKCC1−/−. As positive controls, the same antibody was tested in other cell types where NKCC1 expression is well established. These positive controls included mouse and rat dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons (56, 93), the basolateral membrane of α-intercalated cells in the outer medullary collecting duct of kidney (56), and the basolateral membrane of mouse salivary glands (69). The Kaplan-CT NKCC1 antibody was used at dilutions of 1:50 to 1:400 in PBS-T. Sections were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C in a humid chamber and washed 3 × 5 min with PBS-T followed by incubation (2.5 h) with FITC anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) diluted 1:50 in PBS-T. The sections were coverslipped with VECTASHIELD.

NKCC1 was also detected using affinity-purified monoclonal antibody (MAb) T4. The unpurified T4 MAb supernatant came from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa and was affinity-purified as previously described (6). This MAb was raised against a fusion protein fragment of the CT of the human colonic NKCC1 (55). NKCC1 immunoreactivity detected with this MAb in the apical membrane of NKCC1+/+ CPECs disappeared in NKCC1−/−. Further tests of NKCC1-specific immunodetection using T4 MAb have been recently reported by another group (47). Further, we observed the same pattern of NKCC1 immunoreactivity in CPECs with an antibody (data not shown) raised against the NH2 terminus of NKCC1: α-wNT (56). The α-wNT NKCC1 antibody was also validated against NKCC1−/− CPECs. The Kaplan-CT antibody targeted sequences of amino acids in the COOH terminus of mouse NKCC1, whereas α-wNT targeted an amino acid sequence located in the NH2 terminus of rat NKCC1. All confocal immunofluorescence and ultrastructural studies (see below) were done in CPs of lateral ventricles. Unpublished studies in our laboratory using the α-wNT NKCC1 antibody reveal the same pattern of immunoreactivity in the CP of the third and fourth ventricles.

Electron Microscopy

Two NKCC1−/− mice lacking exon 9 of the Slc12a2 gene (17) and their corresponding controls were perfusion-fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.3) and postfixed for 1 h in the same fixative solution. After thorough washes in PBS, pH 7.2, we obtained 50-µm-thick brain sections using a vibratome. The sections were treated with freshly made 2% OsO4 in 0.1 M PB with 5% sucrose for 1 h. After washing the OsO4 with PB, the sections were dehydrated 2 × 5 min in ascending ethanol (EtOH) diluted in double-distilled water (50, 70, and 95%) and 3 × 10 min in 100% EtOH, ending in propylene oxide (2 × 5 min). The dehydrated sections were then infiltrated overnight in resin made up of a mixture of 1:1 propylene oxide and Epon-Araldite. The next day, the sections were flat-embedded in Epon-Araldite between two Teflon-coated coverslips. One percent of “depleted” uranyl acetate was added to the first 70% alcohol step and left staining “en bloc” for 20 min before proceeding with subsequent alcohol dehydration steps. The “wafer” embedded sections were cured at 64°C for 4–6 days and then examined in a microscope. Areas containing choroid plexus were recut and “Super Glued” to the top of an EM beam capsule, and ultrathin sections were obtained (silver-gold approximately 80–90 nm thick) in a Sorvall MT-5000 Ultra Microtome and collected in 200 mesh nickel grids. The sections were then counterstained with standard Reynolds lead citrate and observed in a Phillips EM208S transmission electron microscope at 70 kV. Imaging was done with standard photographic 4 × 5 EM plates. For presentation, all photographic images were scanned in a conventional Hewlett-Packard scanner.

Pre-Embedding Immunoelectron Microscopy

To study the subcellular localization of NKCC1 in CPECs, we used pre-embedding immunoperoxidase avidin-biotin complex (ABC)-diaminobenzidine (DAB) electron microscopy, a method in which immunolabeling is done before embedding, having the advantage that antigenic sites are not modified by osmication and embedding in hydrophobic resins used for maximal ultrastructural definition (73). For pre-embedding immunoelectron microscopy, the animals were perfusion-fixed with a lower concentration of glutaraldehyde to maximize antigen preservation. The fixative mixture thus consisted of 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.25% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M PB. After extraction, the brains were postfixed for an additional 1–2.5 h in the same fixative and then washed overnight in 15% sucrose in 0.01 M PBS. The following day, 50-µm-thick sections were obtained with a vibratome. To reduce glutaraldehyde fixation and increase antibody penetration, the sections were treated for 15 min with 1% NaBH4 and then thoroughly washed in PBS. After the sections were blocked with normal goat serum (1:10 in 0.1 M PBS), they were incubated overnight at room temperature and under constant agitation with one of two different primary antibodies (Abs) against NKCC1: Kaplan-CT diluted 1:50 in PBS without Triton X-100 or T4 MAb diluted 1:100 in PBS without Triton X-100. The following day, immunoreactive sites were revealed with rabbit or mouse ABC kits (all diluted in 0.01 M PBS; Vector, Burlingame, CA), and peroxidase histochemistry was performed using 0.02% DAB and 0.01% H2O2 diluted in 0.5 M Tris buffer (pH 7.4). Then, the sections were osmicated, dehydrated, and flat-embedded as described above for conventional EM. Ultramicrotomy was performed as for conventional EM, but the ultrathin sections were not counterstained with lead citrate; they were only stained with uranyl acetate in the 70% alcohol step to maximize contrast visualization in the EM of the DAB precipitate labeling of immunoreactivity sites. Thus contrast between EM images in Fig. 1, C and D, and those in Figs. 3 and 4 is different. The sections were observed in the same transmission electron microscope but this time at 60 kV. Photography was done as for conventional EM but using higher-contrast photographic paper to visualize more clearly ultrastructural details below the immunoreaction. The Abs used for pre-embedding immunoelectron microscopy confirmed that NKCC1 immunoreactivity was restricted to the apical membrane of CPECs from NKCC1+/+ and was absent in CPECs of NKCC1−/−.

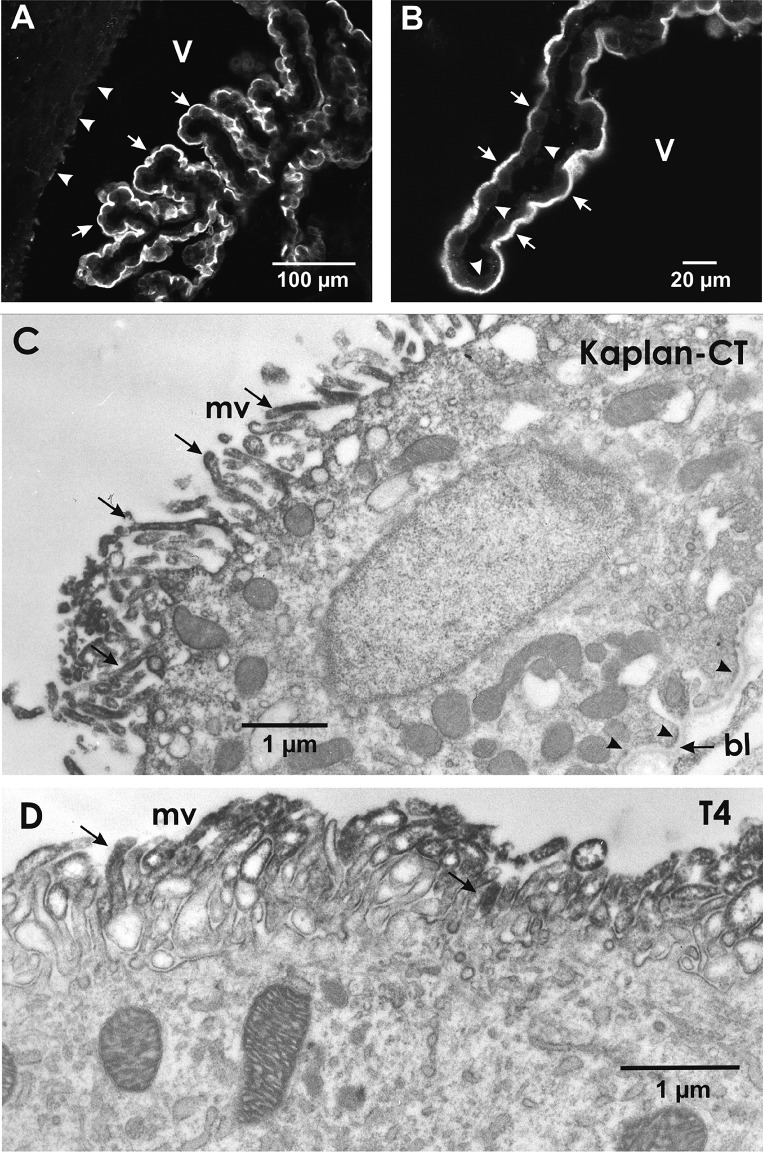

Fig. 1.

Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) immunolocalization in mouse choroid plexus epithelium (CPE). A: low-magnification confocal image of CPE. NKCC1 immunoreactivity is localized in the apical surface (arrows) of CPE. Apical side of CPECs faces the ventricle (V) and is in direct contact with cerebrospinal fluid. Top left shows adjacent brain tissue facing the ventricle. NKCC1 immunoreactivity is barely detectable in ependymal cells lining the ventricular surface (arrowheads). B: high-magnification confocal image of a segment of CPE showing NKCC1 immunoreactivity in the apical surface (arrows). Note the profiles of cuboidal CPECs. NKCC1 immunoreactivity was undetectable in the basolateral side of the CPE (arrowheads). Calibration bars: A, 100 μm; B, 20 μm. Primary anti-NKCC1 was a polyclonal antibody (Ab) raised in rabbits against a fusion protein fragment of the COOH terminus (CT) of mouse NKCC1 (Kaplan-CT; 1:50), and secondary Ab was FITC anti-rabbit (1:50) in PBS-Triton X-100. C and D: ultrastructural immunolocalization of NKCC1 in mouse CPECs using pre-embedding immunoperoxidase avidin-biotin complex-diaminobenzidine methods and 2 different primary antibodies targeting NKCC1. C: Kaplan-CT Ab. D: T4 monoclonal Ab. Both antibodies reveal NKCC1 is localized in the microvilli (mv) on the apical side of the cell (i.e., the luminal side facing ventricle/cerebrospinal fluid). Examples of the NKCC1 immunoreactivity in mv are indicated by arrows in C and D. NKCC1 immunolabeling was absent in the basolateral membrane indicated by arrowheads in the lower right of C, where the basal lamina (bl) of the basement membrane is indicated with an arrow.

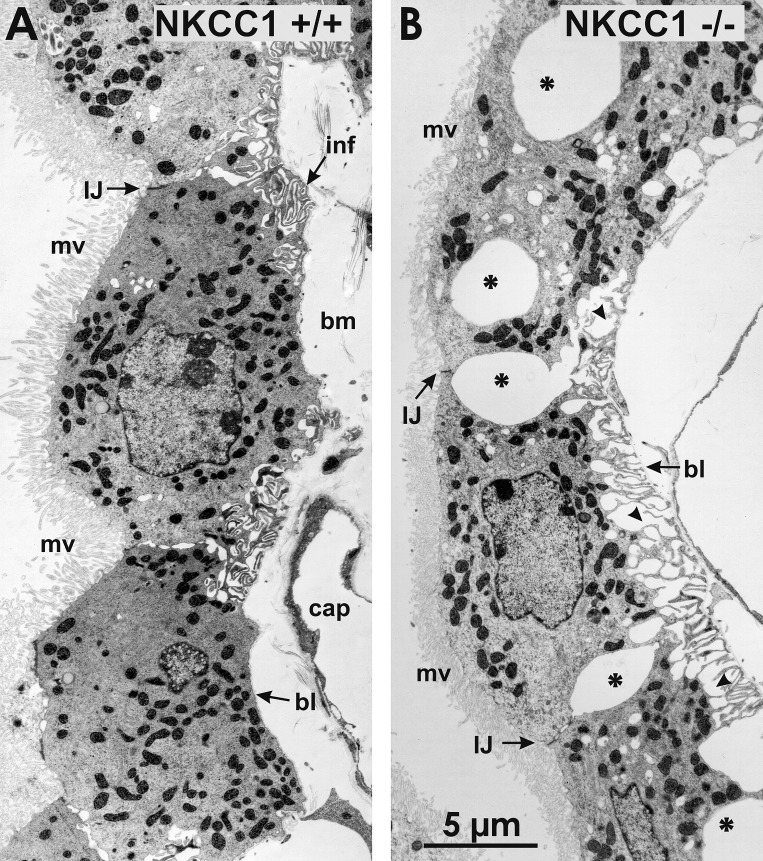

Fig. 3.

Ultrastructural changes of choroid plexus epithelium (CPE) in Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) knockout mouse. A: low-magnification electron micrograph of CPE in wild-type mouse (NKCC1+/+). The CPE is formed by a monolayer of cells, the apical surface of which is packed with microvilli (mv). Cells are held together by intercellular junctions (IJ) at the apical ends of the lateral plasma membrane of contiguous cells. In basal regions, the plasma membrane forms extensive infoldings (inf). Cells are anchored to a basement membrane (bm) composed of connective tissue, capillaries (cap), and a basal lamina (bl). B: choroid plexus epithelial cells (CPECs) of NKCC1−/− mouse exhibit large dilations of the extracellular space between the lateral plasma membrane of contiguous cells (asterisks) and between the basal plasma membranes (arrowheads) and the bl of the bm. CPECs remain attached to each other through apical IJs, and their retracted basal plasma membrane remains anchored to the bl of the bm, forming fingerlike extensions (arrowheads). Microvilli (mv) of these cells appear smaller than in wild-type mice.

Fig. 4.

High-power electron micrograph of choroid plexus of wild-type mouse compared with that of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) knockout mouse. A: choroid plexus epithelial cells (CPECs) of NKCC1 wild-type mouse (NKCC1+/+) show normal ultrastructure. Their apical (cerebrospinal fluid-facing) surface exhibits abundant microvilli (mv), and the cells are joined together at their apical ends by an intercellular junctional complex: a zonula occludens or tight junction (tj) and, beneath this, a zonula adherens (za) or adherens junction. Beyond this junctional complex, the intercellular space exhibits modest dilations that gradually expand toward the basal pole, at which point the basolateral membrane forms a series of large infoldings. Basal end of the cells (e.g., left bottom corner) is relatively smooth and is anchored to the basal lamina (bl) of the basement membrane. Cytoplasm contains abundant mitochondria (mit), a nucleus (Nuc), and some vesicular bodies (vb). B: CPECs of NKCC1 knockout mouse (NKCC1−/−) are shrunken, and their mv appear less abundant and smaller than wild-type mouse. Shrunken CPECs remain joined through the tj and the za. Beneath the za, there is a large dilation of the intercellular space (asterisk) resulting from cell shrinkage. Basolateral membrane is retracted, and the extracellular spaces in between the basal infoldings are greatly enlarged (stars). Basolateral membrane forms fingerlike extensions that remain attached to the bl of the basement membrane (bm).

Genotyping and Identification of Transcripts of NKCC1 by RT-PCR

Genotyping procedures.

Mice were genotyped by PCR using genomic DNA extracted from 1 to 3 mm of tissue obtained from tail clips during P3–P6. The genotyping procedure for the NKCC1−/− mice strain lacking exon 6 of the Slc12a2 gene was as described by Shull’s group (22), using three primers in the reaction mixture: sense (5′-GGA ACA TTC CAT ACT TAT GAT AGA TG-3′); antisense (5′-CTC ACC TTT GCT TCC CAC TCC ATT CC-3′); and neo (5′-GAC AAT AGC AGG CAT GCT GG-3′). Genealogy and data for each mouse were recorded using GenoPro software (https://www.genopro.com). As for NKCC1−/− lacking exon 9 of the Slc12a2 (17), they arrived at Wright State University Laboratory Animal Resources facility already genotyped from Prof. Delpire’s laboratory.

PCR amplification of NKCC1 transcripts.

The strategy to amplify variants of the Slc12a2 gene, as well as the methods followed, were essentially the same as those described in previous work (56). These variants are the full length (18), here referred to as NKCC1a, and a shorter variant lacking exon 21, here referred to as NKCC1b. In previous work, we (56) called the long-full-length variant NKCC1-L and the short NKCC1-S. The primer sets to coamplify both variants, NKCC1a (502 bp) and NKCC1b (453 bp), were NKCC1-502a/453b: sense (5′-TGT GGT CAT TCG CCT AAA GGA AGG ACT GGA TAT ATC-3′); and antisense (5′-GGA GAA GTC TAT TCG GAA TTT ACT GAG TAA-3′). RT-PCR was done using 1–1.5 µg of total RNA extracted from juvenile/adult (P12–P29) mouse’s brain, choroid plexus, spinal cord, kidney, and DRG tissues. Negative controls were performed replacing cDNA from the respective tissues with water (H2O) and using NKCC1-502a/453b as the PCR primer set. Densitometric analysis was performed using the open source ImageJ software package v1.42 for Linux.

Isolation of Single Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cells

The method for isolation of single CPECs was adapted from that described for rat CPECs (98) and Necturus gallbladder epithelial cells (94). Mice, P10–P21, were anesthetized using CO2 and then euthanized by rapid decapitation. The brain was removed and immediately submersed into a dish containing Dulbecco’s PBS (no Ca2+, no Mg2+, pH 7.1; Life Technologies) at room temperature. The bottom of the dish had a silicone lining to affix the brain with pins and visualize it under a ×20 dissecting microscope. The CP of the fourth ventricle was dissected out with watchmaker forceps (no. 4) and incubated for 1 h in 1 ml of freshly made dissociation medium composed of culture medium (see below) supplemented with protease XIV (0.5 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and collagenase IV (0.5 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). The culture medium was prepared the day of the experiment and contained DMEM/F-12 (HyClone; Fisher), 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Gibco; Fisher), penicillin-streptavidin (10 U/ml-10 µg/ml; HyClone; Fisher), and human EGF (40 ng/ml). The medium was filtered at room temperature using a 10-ml Luer-Lock syringe attached to a sterile filter (33-mm Millex-GP Xpress PES 0.22 µm; Merck Millipore). Following the incubation period, the dissociation medium was aspirated off, and the CP was rinsed three times with culture medium and suspended in 500-µl culture medium.

To dissociate the CPECs, the CP suspended in culture medium was vigorously shaken with an electronic vortex for ~3 s, after which the cells were gently triturated with fire-polished glass Pasteur pipettes of two different bore diameters (equivalent to the inner diameter of 23- and 32-gauge needles and used in that order), 20 times per bore size. Cells were plated on 25-mm sterile coverslips (no. 72196-25; Electron Microscopy Sciences) previously degreased and cleaned with acetone, 70% EtOH, and double-distilled water and coated with laminin (5 µg/ml; no. L2020; Sigma-Aldrich) and poly-d-lysine (100 µg/ml; no. 354210; BD Bioscience). The coverslips with the plated cells were covered with culture medium (~250 µl) contained in petri dishes and placed in an incubator at 5% CO2-95% air atmosphere, 85–95% humidity, 37°C, for 2–6 h before use for live-cell-imaging experiments.

Solutions

The isosmotic physiological control (ISO) solution contained, in mM, 123.5 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.0 CaCl2, 1.25 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, and 10 glucose. The pH was adjusted to 7.3 at 25°C with NaOH, and the osmolality was adjusted with sucrose to 290 ± 1% mosmol/kgH2O.

The anisosmotic calibration solutions for CWV measurements were prepared by adjusting the amount of sucrose in the ISO solution to 261 ± 1% mosmol/kgH2O for the 10% hypoosmotic solution and to 319 ± 1% mosmol/kgH2O for the 10% hyperosmotic solution, as previously described (5). The Cl−-free ISO solution (ISO 0Cl−) was made by replacing Cl− with gluconate in the ISO control solution on a mole-for-mole basis, and the pH was adjusted to 7.3. The osmolality of all solutions was measured with a vapor pressure osmometer (model 5520; Wescor Biomedical Systems, Logan, UT). All the solutions were equilibrated with air. Stock solutions of the following chemicals were prepared using dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or water as the initial solvent and then diluted in ISO solution: bumetanide, ouabain, verapamil, calcein-acetoxymethyl ester (AM), Asante NaTRIUM Green-2 (ANG-2), and N-(ethoxycarbonylmethyl)-6-methoxyquinolinium bromide (MQAE). When DMSO was used as the solvent, its concentration in the final solutions was <1%.

Live-Cell-Imaging Microscopy

Coverslips with attached CPECs were mounted into a fluid perfusion imaging chamber (RC-21BRW; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) positioned on the stage of an epifluorescence inverted microscope (Olympus IX81; Olympus, Center Valley, PA) equipped with a Fluor oil-immersion lens (×40, 1.35 numerical aperture; Olympus) and DIC optics. Experimental solutions were perfused at a flow rate of 6 ml/min at 25°C. The fluid volume of the chamber (~300 µl) was exchanged with a half-time of <5 s. The fluorescent dyes calcein (Invitrogen), MQAE (Invitrogen), and ANG-2 (TEFLabs, Austin, TX) were used to measure CWV changes, [Cl−]i, and [Na+]i, respectively. Each dye was excited at its characteristic wavelength and bandwidth (see below) using a monochromator (OptoScan; Cairn Research, Faversham, United Kingdom) equipped with a 75-W xenon arc lamp (Ushio UXL S50A, Ultra High Stability). The excitation light passed through a liquid light guide before entering the microscope optical path and reaching the cells. The emitted fluorescence from the dye-loaded CPECs passed through emission filter cubes specific for the emission wavelength of each dye. A cooled, digital charge-coupled device camera (ORCA 2-ER C4742-95; Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan) captured the emitted fluorescence as well as the cell images. Image acquisition, digital pinhole size and position, and fluorescence recording were done using MetaFluor imaging software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Measurement of Cell Water Volume Changes in Single Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cells Using Calcein Fluorescence

The method for measuring changes in CWV in single cells with the fluorescent dye calcein has been thoroughly described since its development and subsequent refinements in our laboratory (4, 5, 14, 56, 79). CPECs were loaded by exposure to control ISO solution containing 2 μM calcein-AM along with 20 μM verapamil (Invitrogen). Verapamil was added to inhibit the multidrug-resistant P-glycoprotein 1 (MDR1-Pgp), which is known to pump out calcein and other fluorescent dyes from cells (95). Multidrug-resistant P-glycoprotein is highly expressed in CPECs (76). Verapamil significantly reduced drift due to dye efflux from CPECs. Calcein was excited at 495 ± 3 nm with 80-ms light pulses at a frequency of 0.25 Hz, and emission collected from each cell through a circular digital pinhole region (15 × 15 pixels) was recorded at 535 ± 13 nm. This pinhole area was ~4.7% of the mean cross-sectional area of wild-type (WT) CPECs (~155 µm2). Osmotic water volume calibration was performed for each individual cell with ±10% anisosmotic solutions as described previously (5, 56).

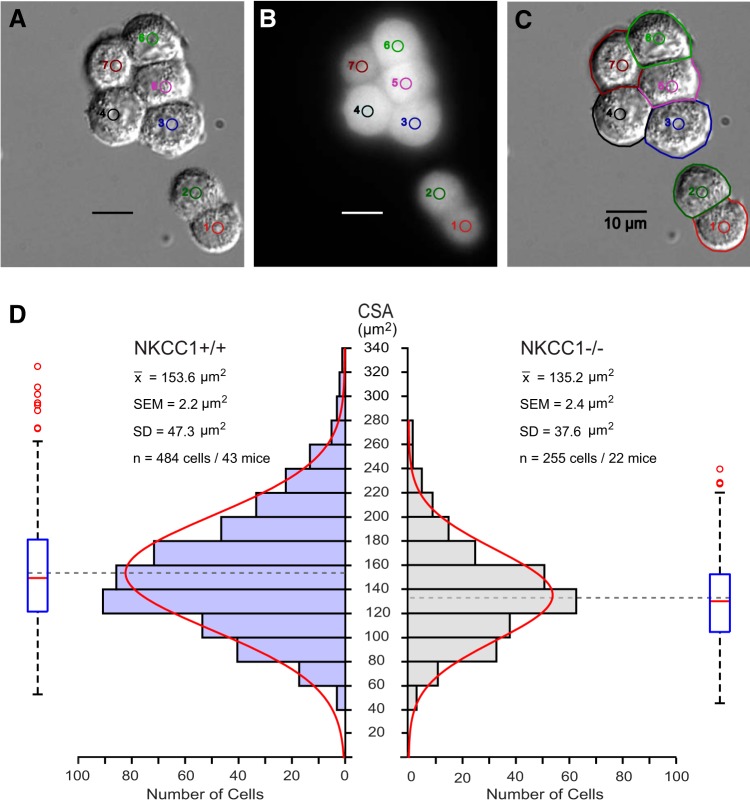

Measurement of Cross-Sectional Area of In Vitro Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cells

Freshly dissociated CPECs from NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− loaded with calcein were imaged using fluorescence and DIC optics to measure their CSA. Each cell within the field was identified with a color-coded pinhole and a number. With the use of the DIC images, the perimeter of each cell, including the brush-border edge, was outlined offline using a computer mouse. Only cells having clearly discernible borders in both DIC and calcein-fluorescent images were included (see below). Likewise, only cells that were loaded with calcein and retained the dye were measured using DIC imaging; it is well-known that cells that do not retain calcein, or do not cleave calcein-AM, are damaged or dead. To overcome the issue of the overlap of the border with the neighboring cells, deconvolution of the fluorescent images was carried out using ImageJ 1.46r (85). Fluorescent images, however, cannot be used to determine CSAs because the fluorescence intensity at the edges of the cells is very dim due to the lower concentration of dye in the thin volumes of the edges, which results in underestimates of CSAs. However, deconvolved fluorescent images were used as a guide to determine the borders between cells in the measurement of the perimeters of DIC images. The CSA of each individual CPEC was calculated using the roipoly function in MATLAB. This function yields the area of each cell in square pixels, which is then converted to square micrometers using the conversion factor 0.40484 µm2/pixel2. The latter is obtained from the imaging system calibration (10 µm/49.7 pixels = 0.201207 µm/pixel).

CSAs were measured in 484 CPECs obtained from 43 NKCC1+/+ mice (19 male and 24 female) and 255 CPECs from 22 NKCC1−/− mice (14 male and 8 female). Initially, all of the CPECs cells were divided into 3 groups according to mouse postnatal age and genotype. For NKCC1+/+, the groups were P10–P14 (108 cells/11 mice), P15–P18 (322 cells/27 mice), and P19–P21 (54 cells/5 mice). Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA showed that there were no significant differences between WT groups of different postnatal ages. For NKCC1−/−, the groups were P10–P14 (34 cells/4 mice), P15–P18 (n = 143 cells/12 mice), and P19–P21 (78 cells/6 mice). Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA showed that there were no significant differences between NKCC1 KO groups of different postnatal ages. Thus all of the cells from WT were considered as coming from the same population for statistical analysis. Likewise, all of the cells from NKCC1−/− were considered as samples from the same population.

Measurement of Intracellular Chloride in Single Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cells

The method to measure [Cl−]i in single CPECs loaded with the fluorescent indicator MQAE (96) was essentially the same that we described in detail for other cell types (56, 79). In brief, CPECs were loaded with MQAE by applying the dye to the imaging chamber at a concentration of 5 mM and with 20 μM verapamil. MQAE was excited at 350 ± 5 nm by exposure to 20-ms light pulses at a frequency of 0.1 Hz. The emission signals (460 ± 25 nm) were sampled at the same frequency. Once loaded, cells were equilibrated in isosmotic (ISO) solution before Cl− depletion by exposure to isosmotic Cl−-free solution (ISO 0Cl−). Once a new steady state was reached in the ISO 0Cl− solution, the CPECs were considered to be depleted of Cl−, i.e., apparent [Cl−]i = 0. The validity of this assumption was discussed in previous work from our laboratory (56). Following Cl− depletion, cell Cl− was recovered by exposure to the ISO control solution. At the end of the experiment, MQAE was calibrated against [Cl−]i using a double-ionophore technique in which the cells were permeabilized with the K+/H+ ionophore nigericin (5 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) and the Cl−/OH− ionophore tributyltin acetate (10 μM; Sigma-Aldrich). Besides these ionophores, the calibration solutions contained, in mM, 10 glucose, 5 HEPES, 120 K+, and [Cl−] + [] = 120. The calibration steps were 0, 20, 40, and 60 mM Cl−. MQAE was then quenched with 150 mM KSCN to determine the background fluorescence. MQAE fluorescence signal drift correction was performed offline by fitting the entire data transient to a straight line. The correlation coefficient of the fit was ≥0.99 for the cell to be included in the analysis (see below). MQAE fluorescence data measured for each individual cell was then converted to [Cl−]i using the Eq. 1 derived from the Stern-Volmer relation:

| (1) |

where F0 is the steady-state fluorescence from each cell measured in ISO 0Cl− solution, Ft is the fluorescence recorded with respect to time, and KSV is the Stern-Volmer quenching constant of MQAE for Cl−. The KSV was calculated for each cell following the four-point calibration procedure outlined above by plotting (F0/Ft) − 1 versus [Cl−]. The slope of this relation is KSV. The average KSV for the intracellular calibrations of MQAE in WT CPECs was 16.9 M−1 [standard deviation (SD) 2.7 M−1; n = 41 cells from 5 mice, 2 female and 3 male], and the average KSV of KO CPECs was 10.3 M−1 (SD 3.7 M−1; n = 45 cells from 7 mice, 3 female and 4 male). These KSV values fall within the range of 5–25 M−1 reported for other cell types (40, 56) and are large enough to obtain reliable calibration plots for [Cl−]i determinations. Furthermore, only cells fulfilling the following criteria for cell viability and MQAE performance were chosen for analysis: 1) calibration plot yielding KSV > 5 M−1; 2) correlation coefficient of calibration plot >0.99; 3) MQAE fluorescence in each calibration solution reached steady state; and 4) MQAE fluorescence in both the ISO control and ISO 0Cl− solutions reached steady state.

The Cl− equilibrium potential (ECl) for each cell was calculated using the Nernst equation:

| (2) |

where [Cl−]i and [Cl−]o are the measured concentrations of intracellular and extracellular Cl−, respectively, z (= −1) is ion valence, R is the gas constant, T is absolute temperature (in kelvin), and F is the Faraday constant.

Measurement of Intracellular Sodium in Single Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cells

Measurements of [Na+]i in single CPECs were done with the fluorescent sodium indicator dye ANG-2 (TEFLabs). Measurements were first attempted using the Na+-sensitive indicator sodium-binding benzofuran isophthalate (SBFI), but CPECs could not be adequately loaded with this indicator. ANG-2 was developed as an alternative Na+ indicator (20); we found that the in situ dissociation constant (Kd) for Na+ of this dye is in the range between 20 and 30 mM, as explained below. Kd values in this range yield reliable measurement of [Na+]i within expected physiological levels (60). ANG-2 has been successfully used in invertebrate epithelial cells (80) and in mammalian cell lines (32). Unlike SBFI that is excited in the UV spectral range (340/380 nm), ANG-2 is excited between 488 and 520 nm (peak excitation is 517 nm), therefore decreasing photodynamic cell damage. ANG-2 peak emission wavelength is between 540 and 550 nm (48). To load the cells, 5 μM ANG-2 (AM) was applied to the coverslip with the cells attached, along with an equal volume of Pluronic F-127 (20% wt/vol) and verapamil (20 μM). During data acquisition, the excitation wavelength was set at 500 ± 5 nm (80-ms excitation light pulses, at 0.1 Hz). Emitted fluorescence was detected at 535 nm and was monitored online as described above for calcein. Emitted fluorescence from each cell was measured through a digital pinhole (20 × 20 pixels) positioned at the center of each imaged cell. The fluorescence intensity of each cell was sampled until reaching a stable baseline. At the end of the observation period, cells were calibrated in situ to determine [Na+]i. At the start of calibration, cells were treated with the nonselective monovalent cation ionophore gramicidin D (7 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) to collapse the Na+ and K+ gradients across the cell membrane (78). The calibration solutions contained, in mM, 10 HEPES, 1.2 Ca2+, 57.4 Cl−, and 65 gluconic acid, with [Na+] + [K+] = 120 mM, pH 7.3, and 290 mosmol/kgH2O osmolality, adjusted with sucrose. The calibration points were 120, 90, 60, 30, 12, and 6 mM Na+. Independent measurements in calcein-loaded cells showed that changes in CWV on exposure to these calibration solutions were negligible. This is an important control inasmuch as ANG-2 is a single-wavelength excitation-emission dye. For analysis, the fluorescence data transient obtained from each individual cell was normalized to the value recorded in the 0Na+ calibration solution (after fluorescence background subtraction) using Eq. 3:

| (3) |

where Ft is the fluorescence with respect to time of the entire transient and F0 is the mean steady-state fluorescence in the 0Na+ calibration solution. The mean ANG-2 normalized fluorescence intensity (F; Eq. 3) measured for each Na+ calibration solution was used to plot the graph [1 − (Ft/F0)] versus [Na+]i, and a regression curve was fitted to the data using the Michaelis-Menten equation:

| (4) |

where the maximal normalized fluorescence (Fmax) and Kd values were obtained for each individual cell, as explained below. The normalized fluorescence data (F) was then converted into [Na+]i using the following equation:

| (5) |

where F = [1 − (Ft/F0)], Fmin is the minimal normalized fluorescence (F = 0), and Fmax and Kd were obtained from the curve fitted to the data points (see Fig. 7B). The mean Kd for Na+ in NKCC1+/+ CPECs was 26.8 mM [SD 9.4 mM, standard error of the mean (SEM) 2.0 mM, n = 21 cells, from 3 mice, 1 male and 2 female] and that in NKCC1−/− cells was 17.1 mM (SD 4.3 mM, SEM 2.0 mM, n = 21 cells, from 3 mice, 1 male and 2 female).

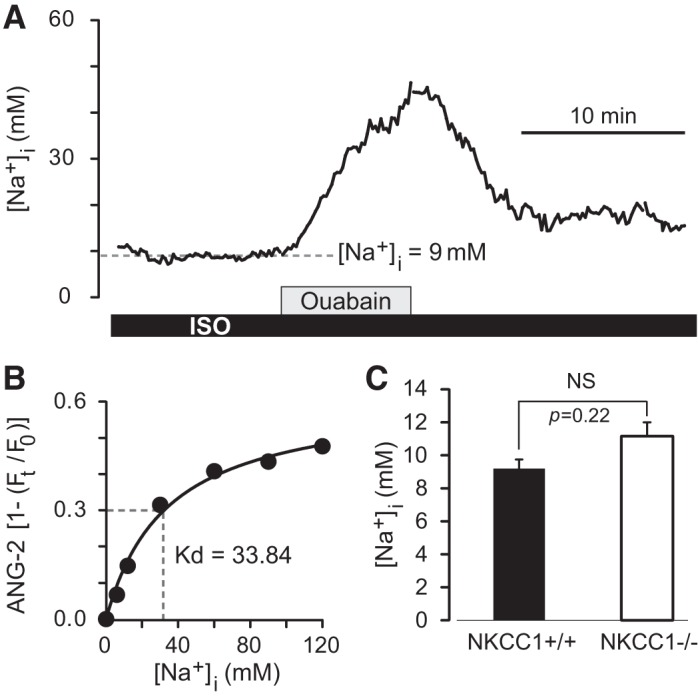

Fig. 7.

Basal intracellular Na+ concentration ([Na+]i) in single choroid plexus epithelial cells (CPECs) measured with the fluorescent indicator Asante NaTRIUM Green-2 (ANG-2). A: example of a recording of basal [Na+]i in an ANG-2-loaded CPEC from a wild-type (NKCC1+/+) mouse, (postnatal day 21, male). Na+-K+ pump was inhibited with ouabain (1 mM) to test that the dye responded to changes in [Na+]i. Basal [Na+]i in this CPEC was 9 mM and increased to ~45 mM during ouabain exposure at an initial rate (d[Na+]i/dt) of 6.5 mM·min−1. Ouabain-induced increase in [Na+]i was reversible on removal of the pump inhibitor. ISO, isosmotic control solution. B: at the end of the observation period each ANG-2-loaded CPEC was calibrated in situ to determine the apparent Kd for Na+ and the maximal normalized fluorescence intensity value Fmax by fitting the Michaelis-Menten equation to the data points. Minimal normalized fluorescence Fmin, the fluorescence recorded in the 0Na+ calibration solution, was adjusted to 0 (after background subtraction). Graph shows the relative fluorescence intensity [1(Ft/F0)] of ANG-2 as a function of [Na+]i from the CPEC in A. F0, steady-state fluorescence; Ft, fluorescence recorded with respect to time. From the Michaelis-Menten fitted to the data points the apparent Kd for Na+ (33.84 mM) and Fmax (0.61) were obtained. Parameters obtained from each cell were used to convert ANG-2 fluorescence intensities into [Na+]i using Eq. 5. C: basal [Na+]i in NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− CPECs. Average basal [Na+]i in NKCC1+/+ cells (black bar) was 9.2 mM (SD 2.5 mM, SEM 0.6 mM, n = 21 cells, 3 mice, 1 male and 2 female). Average basal [Na+]i in NKCC1−/− cells was 11.1 mM (SD 3.9 mM, SEM 0.8 mM, n = 21 cells, 3 mice, 1 male and 2 female). Difference between means was not significant (NS; P = 0.22).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using nonparametric Student’s t-test. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05. Data are presented as sample means and their corresponding standard deviation (SD). The standard error of the mean (SEM) is also reported. A two-sample two-tailed unequal-variances t-test (Mann-Whitney) was used for analyzing the statistical parameters of the NKCC1−/− versus NKCC1+/+ CPEC populations. To test the alternative hypothesis that the population means are not equal, α-significance level was 0.001. The null hypothesis that the means of KO and WT population are equal was successfully rejected with a P value (P < 0.0001) indicating that the means of the two populations were indeed different. The t-test was performed in Excel, MATLAB, and GraphPad Prism 5 for verification. Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA was used to see whether there were differences between CSAs of cells obtained from WT or KO mice of three different age groups, P10–P14, P15–P18, and P19–P21. The results showed no statistical differences (P > 0.1) between different age groups (as described above in the section dealing with measurement of CSAs of in vitro CPECs).

RESULTS

Apical Location of NKCC1 in the Microvilli of Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cells

Confocal immunofluorescence of WT mouse choroid plexus using the anti-NKCC1 polyclonal antibody Kaplan-CT (41) showed clear and specific NKCC1 immunoreactivity localized to the apical surface of the choroid plexus epithelium (CPE), i.e., the ventricular CSF-facing surface of the epithelium (Fig. 1, A and B). The specificity of the Kaplan-CT antibody was validated against NKCC1−/− CPE (negative control) and various NKCC1-immunoreactive tissues (positive control; Refs. 56, 69, 93). NKCC1 immunoreactivity of CPE was absent in NKCC1−/− mouse.

Although the localization of NKCC1 in the apical surface of CPECs is well established (56, 69, 70, 72), its subcellular localization is unknown. To address this issue, we used pre-embedding immunoperoxidase-ABC-DAB electron microscopy. NKCC1 immunolabeling was done using Kaplan-CT Ab and T4 monoclonal Ab validated for NKCC1 specificity in CP. As expected from the confocal immunofluorescence observations, both antibodies revealed that NKCC1 is localized in the apical microvilli (mv) and in the apical membrane segments between mv (Fig. 1, C and D), whereas NKCC1 immunolabeling was not detected in the basolateral membrane (Fig. 1C).

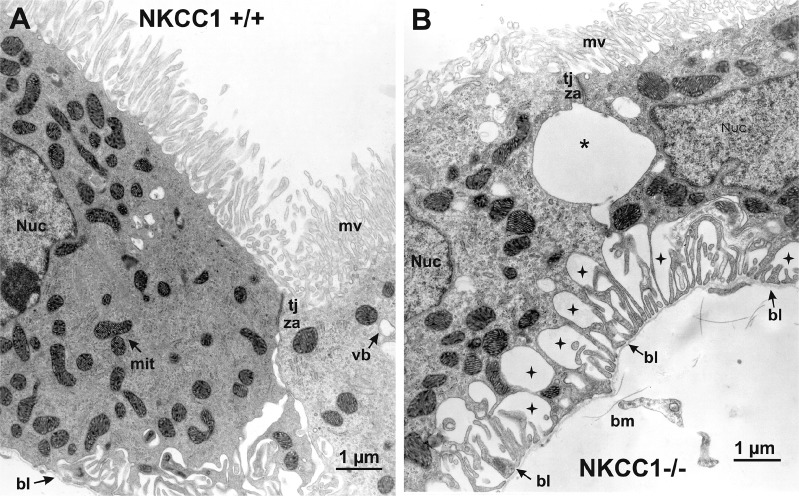

Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cells Express Two NKCC1 Splice Variants

Immunolabeling experiments establish the apical location of NKCC1 in CPECs but do not reveal the identity of the NKCC1 variant expressed because there are no variant-specific antibodies. Rat and mouse express two NKCC1 variants, one full length (NKCC1a) and a shorter one (NKCC1b) resulting from exon 21 exclusion (18, 56, 61, 75). Exon 21 encodes for 16 amino acids containing a dileucine motif that has been proposed to determine the basolateral sorting of NKCC1 in secretory epithelia (11). Disruption of this motif targets the cotransporter to the apical membrane of transfected Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. If this mechanism determines the apical polarity of native NKCC1 in CPECs, these cells should only express NKCC1b. To address this question, we used an RT-PCR strategy that allows coamplification of NKCC1a and NKCC1b transcripts (2, 56) and found that in CP, as in kidney, NKCC1b is barely detectable (Fig. 2B). In contrast, other tissues such as DRG neurons, brain, and spinal cord showed robust expression of NKCC1b (Fig. 2B). We used densitometry ratios obtained from coamplified NKCC1a and NKCC1b bands as surrogates of their relative abundance. The results showed that in CP and in kidney the NKCC1a-to-NKCC1b mRNA ratio was ~15 and ~24, respectively, and the difference between these ratios was not statistically significant (P = 0.41), whereas in brain, DRG, and spinal cord, the ratio was ≤5 (Fig. 2C). Comparison between CP and brain, DRG, and spinal cord showed that the difference in NKCC1a-to-NKCC1b mRNA ratios between CP and nervous tissues was highly significant (P < 0.0001). Interestingly, in mouse kidney, NKCC1 is most highly expressed in the basolateral membrane of the terminal inner medullary collecting duct, the afferent arteriole, and in the glomerular and extraglomerular mesangium (41), whereas NKCC1 is strictly localized to the apical membrane of CPECs. Thus, the abundant expression of NKCC1a, which comprises exon 21, cannot explain the apical polarity of the cotransporter in CPECs.

Fig. 2.

Relative mRNA expression of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) variants, long (NKCC1a) and short (NKCC1b), in brain, choroid plexus, spinal cord, dorsal root ganglion (DRG), and kidney tissues. A: representation of the primer set NKCC1-502a/453b used to coamplify NKCC1a and NKCC1b mRNAs from the tissues indicated. B: representative RT-PCR experiments showing amplicons of expected sizes corresponding to NKCC1a (502 bp) and NKCC1b (453 bp) mRNAs expressed in each tissue. Negative controls were performed using water instead of cDNA (data not shown). Original digital images captured using an UV transilluminator were inverted for clarity to obtain the positive images shown. Gels were cropped to exclude edges and other lanes used to probe for other gene fragments irrelevant to the present study or lanes showing redundant results. Thus, except for the choroid plexus gel shown, the molecular weight standards on each of the other gels were cropped and aligned to the lane showing the NKCC1a/NKCC1b amplicons. To indicate this, a space was added between the lane showing the amplicons and the molecular weight markers. Spinal cord and kidney lanes came from the same gel, and hence the molecular weight markers are the same. C: densitometry ratios obtained from coamplified NKCC1a and NKCC1b bands as a surrogate of their relative abundance. Bars show the mean and standard error of the mean of the results obtained in choroid plexus (n = 14), brain (n = 7), DRG (n = 17), spinal cord (n = 6), and kidney (n = 7), where n = number of animals.

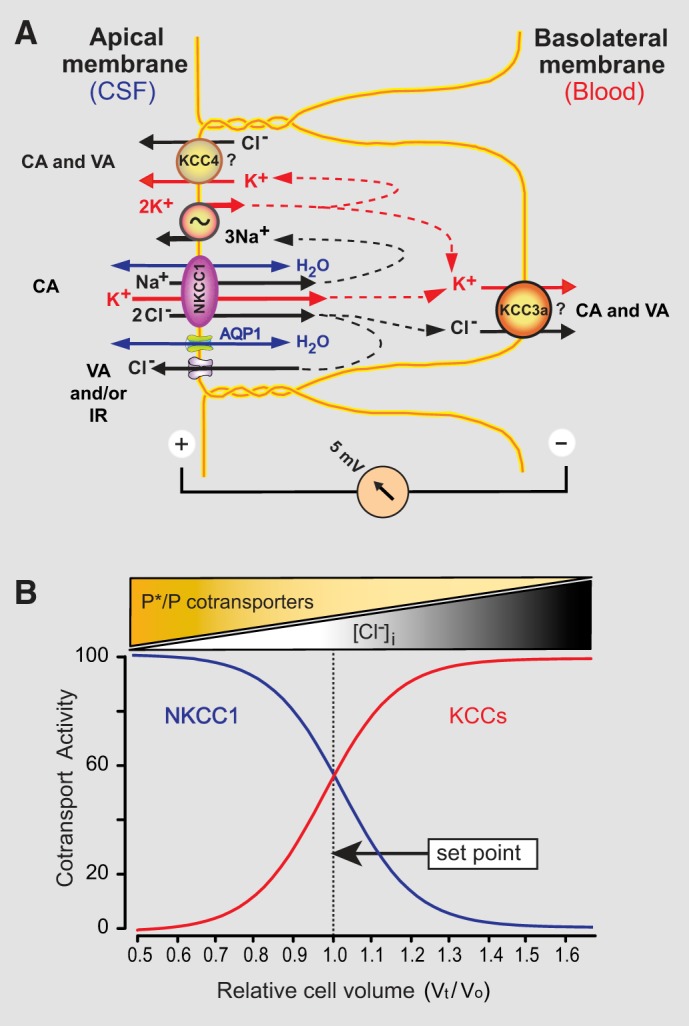

Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cells from NKCC1−/− Mice are Shrunken Both In Situ and In Vitro

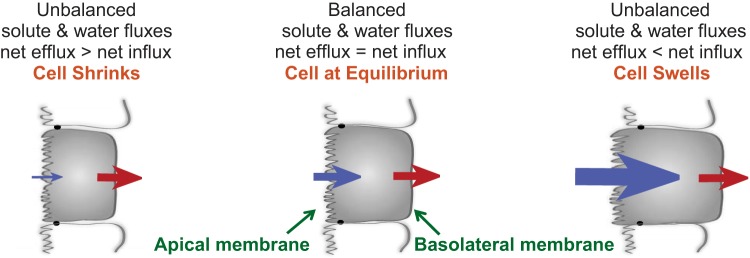

In most animal cells, whether polarized or not, NKCC1 mediates net electroneutral ion influx because the net driving force for transport is inward (3, 79, 83). NKCC1-mediated ion transport is tightly linked to transmembrane water fluxes (79). NKCC1-solute-driven osmotic water transport can occur via both aquaporins and the phospholipid bilayer (64). In addition, water translocation can be mediated by NKCC1 cotransport (25, 26, 102). We hypothesize that under basal conditions apical NKCC1 is constantly active, inwardly transporting ions and associated water, thus maintaining the normal and constant CWV needed for secretion of CSF. Hence, deletion of NKCC1 by gene disruption ought to result in CPEC shrinkage due to unbalanced net solute and water fluxes across the CP epithelium. To begin to test this hypothesis, we studied the CPE of NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− mice by transmission electron microscopy. We found that the CPE of NKCC1−/− mice undergoes substantial morphological changes, as shown in the electron micrographs of Figs. 3 and 4, obtained at low and high magnification, respectively.

At low magnification (Fig. 3), the EM images of in situ CPE from NKCC1−/− mice reveal large dilations of the extracellular space between the lateral plasma membrane of adjacent cells (Fig. 3B). The cells remain attached to each other by intercellular junctions (IJ) at the apical side (Fig. 3B). In deeper regions of the epithelium, toward the basal side, the extracellular space dilations are observed between the basal plasma membrane of CPECs and the basal lamina of the basement membrane. Examples of these extracellular space dilations are shown in Figs. 3B and 4B. The retracted basal plasma membrane of CPECs of NKCC1−/− forms fingerlike extensions that remain attached to the basal lamina of the basement membrane. Another ostensible morphological change of CPECs of NKCC1−/− is that their microvilli appear to be smaller than those of NKCC1+/+ animals. The ultrastructural morphological changes found in CPECs of NKCC1−/− can be more clearly seen in the high-power electron micrographs of NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− shown in Fig. 4, A and B, respectively.

The ultrastructural changes of CPECs of NKCC1−/− revealed by EM could be due to CPEC solute and water loss or to an increase in interstitial fluid volume that would squeeze the epithelial cells. To investigate the issue, we used live-cell-imaging microscopy of freshly dissociated CPECs obtained from NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− mice to measure their CSA and estimate their basal steady-state volume. Under these conditions, changes in CPEC volume can only be attributed to changes in cellular solute and water contents. The CPECs plated on coverslips were continuously perfused with control isosmotic solution (ISO) and imaged using DIC microscopy (Fig. 5A). Each cell was uniquely identified with a color-coded number and a digital circular region (Fig. 5, A–C). To verify their viability, the cells were loaded with the fluorescent dye calcein (Fig. 5B). The perimeter of each CPEC was manually traced from the DIC images (cell edges including microvilli) of the cells that were filled with calcein (Fig. 5C) to determine their CSA. The distribution of CSAs of both NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− were Gaussian (Fig. 5D). The mean CSA was 153.6 µm2 for the NKCC1+/+ CPECs (SD 47.3 µm2, SEM 2.2 µm2, n = 484 cells/43 mice), and 135.2 µm2 for the NKCC1−/− (SD 37.6 µm2, SEM 2.4 µm2, n = 255 cells/22 mice). The difference between the mean CSAs of NKCC1+/+ versus NKCC1−/− is 18.4 µm2 (P < 0.0001). Thus, the CSA of NKCC1−/− CPECs is ~12% smaller than that of NKCC1+/+. The percentage of NKCC1−/− cells that are less than the mean of NKCC1+/+ cells is 72.16%. Assuming that CPECs attached to coverslips adopt the shape of hemispheres, from their measured radii it is possible to calculate their volume from the expression (2/3) π r3. The estimated mean volume of CPECs from NKCC1+/+ is ~715 µm3, whereas the mean volume from NKCC1−/− is ~591 µm3. Therefore, NKCC1−/− CPEC volume is ~17% smaller than WT cells.

Fig. 5.

In vitro live-cell-imaging analysis of the cross-sectional areas (CSAs) of freshly dissociated choroid plexus epithelial cells from Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) wild-type (NKCC1+/+) and knockout (NKCC1−/−) mice. A: cells imaged using differential interference contrast were uniquely identified with a number and a small, colored, digital circle. B: same cells shown in A, loaded with the fluorescent dye calcein. The dye served as an indicator of cell viability; cells that did not load or retained the dye were considered dead and omitted from analysis. C: border of each cell was traced with a colored digital profile to determine the CSA. D: histograms of total distribution of CSAs of cells from NKCC1+/+ (left) and NKCC1−/− (right). Red curves are Gaussian approximations fitted to the histograms. Box plots illustrate the spread of CSA measurements, with the median denoted as a red line. Blue box represents the 1st and 3rd quartiles, whiskers above and below the box show the location of the minimum and maximum, and the red circles represent outliers. Mean (x̄) CSA of choroid plexus epithelial cells from NKCC1−/− cells is significantly smaller than that from NKCC1+/+. Difference between means (153.6 − 135.2 µm2) is 18.4 µm2. Thus, the CSA of NKCC1−/− is 18.4 µm2 smaller than that of NKCC1+/+. Difference between the mean CSAs is highly significant (P < 0.0001). Calibration bars in A–C are 10 µm. Examples shown in A–C came from choroid plexus epithelium of the 4th ventricle of a postnatal day 10 NKCC1+/+ mouse.

Pharmacological Inactivation of NKCC1 with Bumetanide Produces Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cell Shrinkage

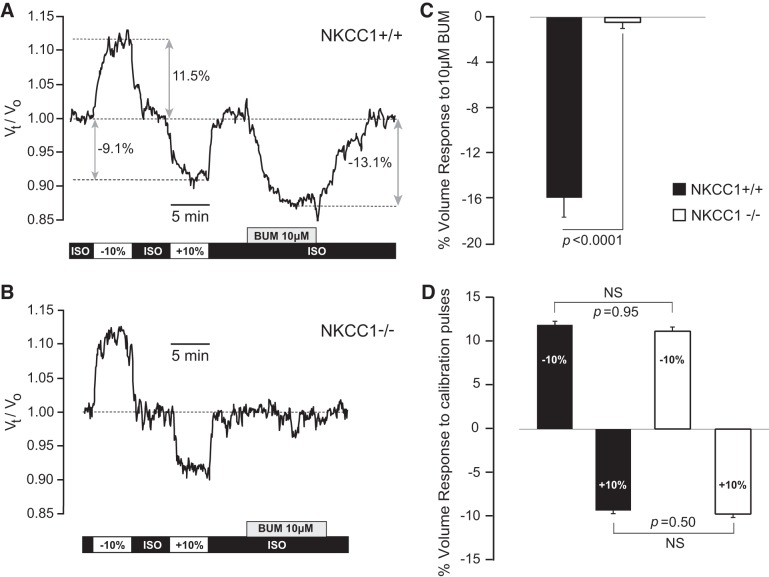

The results presented so far show that genetic deletion of NKCC1 leads to significant decrease in cell volume of CPECs, both in situ and in vitro. These observations are consistent with the hypothesis that apical NKCC1 is continuously active under basal conditions, inwardly transporting ions and associated water, thereby keeping basal CWV constant. Accordingly, specific pharmacological inhibition of apical NKCC1 with bumetanide should lead to a decrease in basal CWV of CPECs. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of bumetanide for human NKCC1 ranges between 0.16 and 0.68 µM (33, 52, 66). It is generally agreed that the inhibitory effect of bumetanide on NKCC1 is specific at concentrations ≤10 µM (3, 83). At higher concentrations (e.g., >50 µM), bumetanide cannot provide positive proof that a given function is specifically mediated by NKCC1 because it also blocks K+-Cl− cotransporters (KCCs), of which three members [K+-Cl− cotransporter 1 (KCC1; SLC12A4); K+-Cl− cotransporter 3 (KCC3; SLC12A6), splice variant a (KCC3a); and K+-Cl− cotransporter 4 (KCC4; SLC12A7)] are claimed to be expressed in CPECs (39, 42, 50, 57, 67, 92). Thus, we tested the effect of 10 µM bumetanide on basal CWV of calcein-loaded CPECs dissociated from NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− mice, respectively (Fig. 6). On exposure to 10 µM bumetanide, CPECs from NKCC1+/+ mice shrank by 16% of their initial volume (SD 6.4%, SEM 1.7%, n = 14 cells/3 animals) at an initial rate of 3.7%/min (SD 0.4%/min, SEM 0.1%/min). The bumetanide-induced shrinkage reversed during washout of the inhibitor. In contrast, CPECs from NKCC1−/− did not respond to 10 µM bumetanide [the mean CWV change on bumetanide exposure in these cells was −0.4%, (SD 1.3%, SEM 0.4%, n = 10 cells/3 animals), which falls within the noise level of the method].

Fig. 6.

Effect of bumetanide (BUM) on basal cell water volume (CWV) in choroid plexus epithelial cells (CPECs) from Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) wild-type (NKCC1+/+) and knockout (NKCC1−/−) mice. A and B: relative CWV changes with respect to time [(Vt/V0) where V0 is the cell water volume in basal control condition (V0 = 1), and Vt is the percentage change in cell water reached at time t, divided by 100] were measured in single CPECs loaded with calcein, as described in materials and methods. Cells were equilibrated in isosmotic control solution (ISO). Osmotic calibration pulses (±10% anisosmotic) preceded the exposure to BUM (10 µm). Bars at the bottom of each trace indicate the duration of exposure to each solution. All of the solutions had the same osmolality (290 ± 1 mosmol/kgH2O) except for those used for the calibration pulses, which were nominally −10% (hypoosmotic) and +10% (hyperosmotic) with respect to the ISO control solution. A: BUM (10 µm) produced shrinkage in CPECs from NKCC1+/+. In the example shown [NKCC1+/+, postnatal day 18 (P18), male], BUM produced a maximum decrease in CWV of −13.1% at an initial rate of −3.8%/min. Cell recovered its initial volume on returning to the isosmotic (ISO) control solution. BUM exposure was preceded by 2 pulses of osmotic calibration solutions nominally −10 and +10% hypoosmotic and hyperosmotic, respectively. Double-headed gray arrows indicate the points in which the maximum of each response is measured for statistical analysis. B: BUM (10 µm) had no effect on basal CWV of CPECs lacking NKCC1. Example shown is from an NKCC1−/−, P11, female. Thus BUM-induced shrinkage is due to a specific pharmacological inhibition of NKCC1. C: maximum percentage change in CWV (% volume response) produced by 10 µM BUM in NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− CPECs. In NKCC1+/+ cells, BUM produced an average CWV decrease of −16.0% (SD 6.4%; SEM 1.7%, n = 14 cells, 3 mice). BUM had no effect in CWV of NKCC1−/− (mean 0.4%, SD 1.4%, SEM 0.4, n = 10 cells, 3 mice). Difference between means is significant, P < 0.0001. D: percentage change in CWV produced by exposure to ±10% anisosmotic calibration pulses preceding BUM exposure. Amplitudes of the responses were measured as indicated by the double-headed gray arrows in A. Differences between hypoosmotic and hyperosmotic pulses recorded in NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− cells were not statistically significant (NS). Bars in C and D represent the mean % change in CWV response. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). Black bars in C and D represent data from NKCC1+/+, and white bars correspond to data from NKCC1−/−.

Figure 6 shows representative examples of the effect of 10 µM bumetanide on basal CWV of single CPECs dissociated from NKCC1+/+ (Fig. 6A) and NKCC1−/− (Fig. 6B) mice, respectively. Figure 6, C and D, shows the statistical summary of these results. In these experiments, cells were initially equilibrated with isosmotic control solution (ISO), followed by exposure to osmotic calibration solutions (±10% anisosmotic), re-equilibrated with ISO, and then exposed to bumetanide as indicated by the gray box at the bottom of each trace (Fig. 6, A and B). In the example shown in Fig. 6A, on exposure to 10 µM bumetanide, the cell shrank by 13.1% of its initial volume, at an initial rate of −3.8%/min. On returning to isosmotic (ISO) control solution, the cell recovered its initial volume. Figure 6, B and C, shows that bumetanide did not elicit any changes in CWV in the NKCC1−/− CPECs. This demonstrates that the bumetanide-induced shrinkage of CPECs from NKCC1+/+ is specifically mediated by NKCC1. Furthermore, the nominally ±10% anisosmotic calibration pulses applied before bumetanide followed, as expected, ideal osmometric behavior, and their amplitude was not different when comparing cells from NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− mice (Fig. 6D). Thus the lack of effect of bumetanide in the NKCC1−/− cells cannot be attributed to changes in the osmotic properties of these cells.

Measured Basal Intracellular [Na+] in CPECs Energetically Favors NKCC1 Net Solute Uptake

A key point in the controversy regarding the direction of net ion fluxes mediated by NKCC1 is the basal [Na+]i of CPECs. This is because [Na+]i is a major determinant of the sign and magnitude of the net free energy driving NKCC1 transport, as discussed below. We reasoned that if the driving force for basal cotransport is inward, [Na+]i cannot be as high as previously reported in mammalian CPECs (36, 46, 62). Thus we measured [Na+]i in freshly dissociated CPECs of NKCC1 WT and KO mouse using the Na+ fluorescent indicator ANG-2 (20, 80, 92). Figure 7 shows an example of these measurements and a summary of the results. The mean [Na+]i in CPECs of NKCC1+/+ was 9.2 mM (SD 2.5 mM, SEM 0.6 mM, n = 21 cells, 3 mice), a value that is considerably lower than the 30 to >48 mM previously reported for mammalian CPECs that would energetically favor NKCC1 working in the outward (secretory) mode (36, 46, 92). Interestingly, our value is closer to that obtained from measurements of intracellular Na+ activity using ion-selective microelectrodes in single cells of amphibian CP (84). We also found that the mean [Na+]i in CPECs of NKCC1−/− was 11.1 mM (SD 3.9 mM, SEM 0.8 mM, n = 21 cells, 3 mice), a value that is not significantly different (P = 0.22) to that measured in NKCC1+/+ cells (Fig. 7C). This result shows that the mechanisms that regulate [Na+]i in CPECs remain unchanged in NKCC1−/− cells.

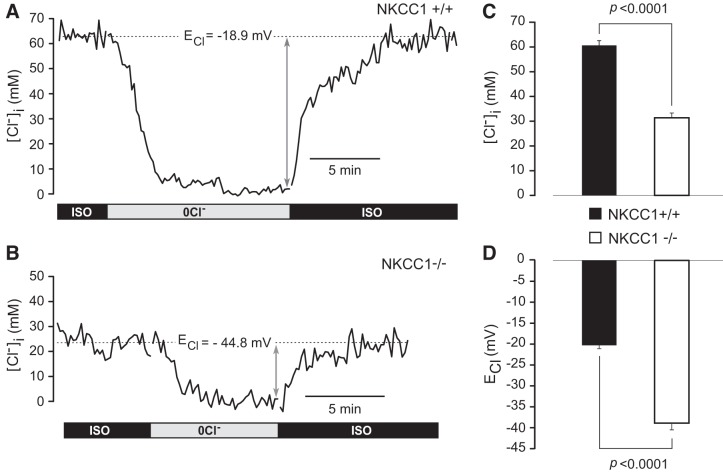

Basal Intracellular [Cl−] in CPECs of NKCC1−/− Mouse is Significantly Lower than in NKCC1+/+

A central hypothesis of the present study is that apical NKCC1 maintains a constant cell water volume of CPECs and a higher-than-equilibrium [Cl−]i needed for transepithelial solute and water transport required for CSF secretion. Accordingly, basal [Cl−]i in NKCC1+/+ should have a value commensurate with these requirements. Furthermore, genetic inactivation of NKCC1 should produce a significant drop in [Cl−]i. We tested these hypotheses by measuring basal [Cl−]i in NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− CPECs using MQAE. Figure 8, A and B, shows representative examples of these measurements. The mean basal [Cl−]i of NKCC1 WT was 60.7 (SD 12.3 mM, SEM 1.9 mM, n = 41 cells/5 mice), and the corresponding ECl calculated from Eq. 2 (see materials and methods) was −20.3 mV (SD 5.2 mV, SEM 0.8 mV). The basal [Cl−]i of NKCC1 KO was 31.4 mM (SD 12.8 mM, SEM 1.9 mM, n = 45 cells/7 mice), and the corresponding ECl was −38.9 mV (SD 10.9 mV, SEM 1.6 mV). The differences between mean [Cl−]i and ECl of NKCC1+/+ versus NKCC1−/− were significantly different (P < 0.0001), as shown in Fig. 8, C and D. The average ECl of NKCC1−/− CPECs (−38.9 ± 1.6 mV) is close to the membrane potential (Em) of NKCC1+/+ mouse CPECs (−39.5 ± 1.5 mV) kept under similar experimental conditions (81) but slightly more depolarized (8.5 mV) than the Em of −47.4 ± 2.1 mV reported by another group (13). These observations indicate that NKCC1 is the main Cl− uptake system in CPECs, maintaining [Cl−]i above its electrochemical equilibrium potential; genetic deletion of NKCC1 results in a significant reduction in [Cl−]i to values close to electrochemical equilibrium (i.e., in NKCC1−/− cells, ECl is close to Em).

Fig. 8.

Intracellular Cl− concentration ([Cl−]i) in single choroid plexus epithelial cells (CPECs) of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) wild-type (NKCC1+/+) and knockout (NKCC1−/−) mice. Shown are examples of intracellular Cl− transients recorded in single N-(ethoxycarbonylmethyl)-6-methoxyquinolinium bromide (MQAE)-loaded CPECs dissociated from NKCC1+/+ (A) and NKCC1−/− (B) mice in response to isosmotic removal and return of external Cl−. These type of transients were used to measure basal [Cl−]i and calculate the Cl− equilibrium potential (ECl) for each cell. CPECs were initially equilibrated in isosmotic control solution (ISO). Isosmotic removal of external Cl− (0Cl−) depleted the cells of Cl−. On restoration of external Cl− (ISO), the [Cl−]i recovered to initial values. Basal [Cl−]i for each cell was measured as the difference between the ISO baseline and the 0Cl− steady state, as indicated by the double-headed gray arrows. Basal [Cl−]i in the NKCC1+/+ CPEC shown in A [postnatal day 14 (P14), female] was 62.9 mM, and the ECl calculated from Eq. 2 was −18.9 mV. Basal [Cl−]i in the NKCC1−/− CPEC shown in B (P18, female) was 22.9 mM, and ECl was −44.8 mV. C: basal [Cl−]i in NKCC1+/+ and NKCC1−/− CPECs. Average basal [Cl−]i in NKCC1+/+ cells was 60.7 mM (SD 12.3 mM, SEM 1.9 mM) n = 41 cells/5 mice), and in NKCC1−/− cells it was 31.4 mM (SD 12.8 mM, SEM 1.9 mM, n = 45 cells/7 mice). Difference between means was highly significant (P < 0.0001). D: ECl for the same population of cells shown in C were −20.3 mV (SD 5.2 mV, SEM 0.8 mV) for the NKCC1+/+ and −38.9 mV (SD 10.9 mV, SEM 1.6 mV) for the NKCC1−/−. Difference between means was highly significant (P < 0.0001).

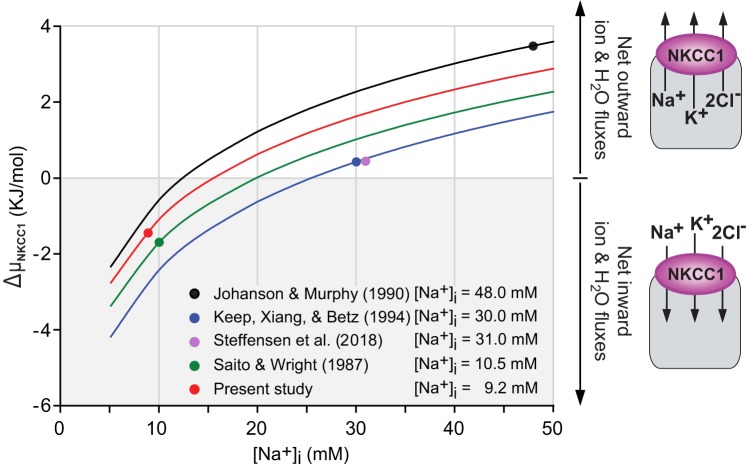

Modeling the Impact of Intracellular [Na+] on the Net Free Energy Driving NKCC1 Transport

NKCC1 transport process is electroneutral; the stoichiometry in vertebrate cells is 1 Na+:1 K+:2 Cl−. The direction of cotransport is determined by the sum of the chemical potential gradients of the transported ions. Therefore the net direction of cotransport depends on the overall net free energy (ΔG) of the system. If ΔG has a negative sign, the direction of cotransport will be inward, i.e., favoring net solute and associated water uptake. When ΔG is 0, the cotransporter is at equilibrium. When ΔG is positive, the direction of cotransport will be outward, favoring net solute and associated water efflux. For a 1 Na+:1 K+:2 Cl− stoichiometry, ΔG is given by the following equation (3):

| (6) |

Thus the driving force for the electroneutral Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport (ΔµNa,K,Cl) is the sum of the chemical potential differences of Na+ (ΔµNa) and K+ (ΔµK) and twice the Cl− potential difference (ΔµCl), since two Cl− ions are translocated per cycle. From the definition of chemical potential for each of the ions involved, it follows that:

| (7) |

In most vertebrate cells under physiological conditions, ΔµNa,K,Cl is negative, thus favoring net ion and associated water uptake. Computation of ΔµNa,K,Cl for a variety of vertebrate cells ranges from −0.71 kJ/mol in bovine aortic endothelial cells to −8.86 kJ/mol in rabbit ventricular myocytes (79, 83). The rare exception may be some red blood cells that have unusually high [Cl−]i (75–100 mM), where ΔμNa,K,Cl is nearly 0, leaving little if any driving force to run the cotransporter under basal conditions (53). When ΔµNa,K,Cl = 0, the cotransporter is in equilibrium, a condition corresponding to the net flux reversal point. From Eq. 7, it is evident that variations in the chemical gradients of any of the transported ions can alter the direction of transport, but this is particularly critical for [K+]o and [Na+]i. Indeed, relatively small changes in [K+]o or [Na+]i have a major impact on ΔµNa,K,Cl. Given that the CSF [K+] is tightly regulated and kept at ~3.0 mM (7, 8, 31), we modeled the impact of [Na+]i on ΔµNa,K,Cl and thus in the direction of NKCC1-mediated net fluxes and the flux reversal point. We used the intracellular and extracellular ion concentrations reported for rat CPECs (36, 46, 62), for amphibian CPECs (84), and for mouse CPECs measured in the present study and in a recent report (92). Figure 9 shows plots of ΔµNa,K,Cl as a function of [Na+]i. The diagrams on the right of the graphs represent the predicted direction of net ion and associated water fluxes mediated by NKCC1. The filled circles superimposed on each graph correspond to the value of ΔµNa,K,Cl (in kilojoules per mole) for the average [Na+]i (in millimolar concentration) reported in each study (i.e., 48, 30, 31,10.5, and 9.2 mM), as specified at the bottom of the figure and explained in the corresponding legend. The results show that for the 48 mM [Na+]i reported by Johanson and Murphy (36) and the 30 mM [Na+]i reported by Keep et al. (46), the corresponding values of ΔµNa,K,Cl are 3.5 and 0.4 kJ/mol, thus energetically favoring outward NKCC1 cotransport. A similar conclusion was reached in a recent study in mouse CP, in which [Na+]i and ΔµNa,K,Cl were estimated to be 31 mM and 0.448 kJ/mol, respectively (92). In contrast, for the intracellular Na+ activity of 8 mM (corresponding to 10.5 mM [Na+]i) reported by Saito and Wright (84) for amphibian CPECs and the mean [Na+]i of 9.2 mM measured in the present study, the values of ΔµNa,K,Cl are −1.5 and −1.3 kJ/mol, respectively, thus favoring NKCC1 transport in the net uptake mode.

Fig. 9.

Modeling the effect of intracellular Na+ concentration ([Na+]i) on the magnitude and direction of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 (NKCC1)-mediated net fluxes in choroid plexus epithelial cells (CPECs). Graphs represent the net free energy driving NKCC1 transport (ΔμNKCC1) plotted as a function of [Na+]i (5–50 mM) by solving Eq. 7, using the reported values of extra- and intracellular ion concentrations for both mammalian (36, 46, 92) and amphibian (84) CPECs. ΔμNKCC1 computed for each of the reported values of basal [Na+]i (indicated at the bottom of the graphs) is represented by color-filled circles superimposed on each plot. Values reported for mouse CP by Steffensen et al. (92) almost overlap with those of Johanson and Murphy (36) estimated in rat and thus are not plotted for all of the range of [Na+]i. ΔμNKCC1 corresponding to the basal [Na+]i and [Cl−]i measured in the present study in single cells of mouse CP is indicated by the red filled circle. Note that the basal [Na+]i of single CPECs measured directly using the fluorescent indicator dye Asante NaTRIUM Green-2 is significantly lower than that reported by Johanson and Murphy (36), Keep et al. (46), and Steffensen et al. (92), based on flame photometry estimates. Basal [Na+]i measured in the present study, 9.2 mM, is closer to that reported for amphibian CPECs, 10.5 mM, using ion-selective microelectrodes (84). Because of the relatively low [Na+]i of amphibian and mouse CPECs (present study), ΔµNKCC1 has a negative value (green and red filled circles, respectively), indicating that under basal conditions NKCC1 is working in the inward direction and, therefore, it cannot directly contribute to cerebrospinal fluid secretion. Extracellular and intracellular ion concentrations used to compute ΔµNKCC1 were [Na+]o = 154 mM, [K+]o = 3 mM, [Cl−]o = 128 mM, [Na+]i (basal = 48 mM, 5–50 mM modeled range), [K+]i = 145 mM, [Cl−]i = 65 mM, absolute temperature (T) = 310 K, for Johanson and Murphy (36); [Na+]o = 148 mM, [K+]o = 2.9 mM, [Cl−]o = 133 mM, [Na+]i (basal = 30 mM, 5–50 mM modeled range), [K+]i = 120 mM, [Cl−]i = 50 mM, T = 310 K, for Keep et al. (46); [Na+]o = 150 mM, [K+]o = 3 mM, [Cl−]o = 100 mM, [Na+]i (basal = 31 mM), [K+]i = 141 mM, [Cl−]i = 35 mM, T = 310 K, for Steffensen et al. (92); [Na+]o = 110 mM, [K+]o = 2 mM, [Cl−]o = 89 mM, [Na+]i (basal = 10.5 mM, 5 to 50 mM modeled range), [K+]i = 89.5 [Cl−]i = 31.6 mM, T = 295 K, for Saito and Wright (84), and [Na+]o = 126 mM, [K+]o = 3 mM, [Cl−]o = 131 mM, [Na+]i (basal = 9.2 mM, 5–50 mM modeled range), [K+]i = 110 mM, [Cl−]i = 61.9 mM, T = 295 K, for the present study.

DISCUSSION

CPECs secrete CSF through mechanisms that are unclear. CPECs express Na+-K+-ATPase and NKCC1 on their apical membrane domain, diverging from the typical basolateral membrane location in secretory epithelia (3, 15). Although it is well-established that the apical Na+/K+ pump is the major source of Na+ secretion toward the luminal side of the CPE (reviewed in Ref. 71), the function of apical NKCC1 in this secretory epithelium is not understood and has been the subject of much debate (28, 71, 92). The apical location of NKCC1, the inhibitory effect of intraventricular bumetanide on CSF secretion, and the uncertainty regarding the ion gradients that determine the direction of NKCC1 cotransport are the essential points fueling the controversy about the function of NKCC1 in CPECs (71). The key issue in this debate is whether under normal physiological conditions, apical NKCC1 has a secretory versus an absorptive function or a dual absorptive and secretory function. These transport modes (secretory, absorptive, and dual) are not mutually exclusive since NKCC1 cotransport direction is reversible, i.e., net electroneutral cotransport can be inward or outward, depending on the Na+, K+, and Cl− chemical gradients across the cell membrane, as defined in Eq. 7 (3, 24, 83). Determining the direction of net ion fluxes mediated by NKCC1 and associated water fluxes under basal physiological conditions is essential for understanding the function of this cotransporter in CPE. If NKCC1 normally works in the net efflux mode, it may be directly involved in CSF secretion. Conversely, if NKCC1 works in the net influx mode, as it does in the basolateral membrane of other Cl− secreting epithelia, then it would have an absorptive function and could be involved in CSF K+ regulation and maintenance of CWV and [Cl−]i needed for secretion.

Keep and coworkers (46, 91) and, more recently, MacAulay’s group (92) proposed that although apical NKCC-mediated net fluxes could be bidirectional, NKCC1 normally works in the net outward (secretory) mode, as shown in Fig. 9. According to this view, NKCC1 directly contributes to CSF secretion. However, work by Wu et al. (98) suggested that under basal conditions apical NKCC1 functions in the inward mode, absorbing K+ from CSF to blood. In the present work, we resolve this long-standing controversy using a combined methodological approach that includes EM, live-cell-imaging microscopy, single-cell measurements of intracellular free ion concentrations and CWV, as well as pharmacological and molecular inactivation of NKCC1 in NKCC1 WT and KO mice models. The evidence obtained from both in situ and in vitro models shows that under basal conditions NKCC1 normally works in the net inward flux mode maintaining both the [Cl−]i and the water volume of CPECs. We propose that by virtue of being continuously active, transporting ions and associated water in the inward direction, apical NKCC1 maintains [Cl−]i and CWV at a certain level (set point), playing an indirect but critical role in CSF secretion. This explains the counterintuitive observation that pharmacological inhibition of NKCC1 by intracerebroventricular application of bumetanide significantly reduces basal CSF secretion (35, 92) and CSF hypersecretion following posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus (44).

NKCC1 is Densely Packed in the Microvilli of Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cells

Our confocal immunofluorescence results confirm the expression of NKCC1 to the apical domain of mouse CPE (69, 92). The observed pattern of NKCC1 expression in mouse CPE is consistent with that reported in rat and human (70, 72). With the use of immuno-EM with two different anti-NKCC1 antibodies validated against NKCC1−/− tissues, we show for the first time that NKCC1 is densely packed in the microvilli of the apical domain of CPECs (Fig. 1, C and D). NKCC1 localization in microvilli is physiologically significant; microvilli considerably increase the surface area of the apical side of the CPE interfacing with CSF. Morphometric studies show that in adult rat (P30), the total apical surface area of the CPE is 75 cm2, which is about half of the surface area of the cerebral capillaries (155 cm2) forming the blood-brain barrier (45). Besides NKCC1 and the Na+-K+-ATPase, CPECs abundantly express aquaporin 1 (AQP1) in the apical membrane (63, 72). The location of this molecular machinery indicates a vast surface area available for solute and water exchange in the apical membrane domain of CPECs.

NKCC1 Variants and Apical Sorting in Choroid Plexus Epithelium

The mechanisms of apical sorting of NKCC1 are unknown. The COOH terminus of NKCC1a, the full-length variant of NKCC1, contains a dileucine motif encoded by exon 21, which has been proposed to be essential for basolateral sorting of the cotransporter in epithelial cells (11). The shorter splice variant of NKCC1 (NKCC1b) does not have this dileucine motif in its COOH terminus. Experiments in cultured Madin-Darby canine kidney cells transfected with NKCC1 and NKCC2 chimeric constructs show that transfection with chimeras lacking the dileucine motif are targeted to the apical membrane (11). Furthermore, NKCC2 (SLC12A1), which lacks this sorting signal sequence in the COOH terminus, is targeted to the apical membrane of the thick ascending limb cells in the mammalian kidney (11, 16). We addressed the question of whether the alternative splice NKCC1 isoform (NKCC1b), which is abundantly expressed in the brain (75), spinal cord, and DRG neurons (56), is the variant localized to the apical membrane in CPECs. Our results show that mouse CPE expresses both NKCC1a and NKCC1b transcripts. Contrary to what was expected based on the dileucine motif hypothesis (11), mRNA expression analysis showed that the relative abundance of NKCC1a/NKCC1b in CPE is significantly higher than in brain, DRG, and spinal cord tissues but not significantly different to that in kidney (Fig. 2C). Thus the relative expression of NKCC1a/NKCC1b in CPE resembles that in mouse kidney, where NKCC1 is localized to the basolateral membrane of the terminal inner medullary collecting duct (41). Therefore, the predominant expression of NKCC1a over NKCC1b in CPECs cannot explain the apical sorting of the cotransporter in terms of the dileucine motif hypothesis. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the apical sorting of NKCC1 in CPECs.

Inactivation of NKCC1 Produces Isosmotic Shrinkage of Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cells Both In Situ and In Vitro