Abstract

Consent is a process that allows for free expression of an informed choice, by a competent individual. The consent is considered as one of the important components of health-care delivery and biomedical research today. Informed consent involves clinical, ethical, and legal dimensions and is believed to uphold an individual's autonomy and the right to choose. It is very important in Indian mental health care as the Mental Healthcare Act (MHCA) 2017 mandates informed consent in admission, treatment, discharge planning, and research intervention/procedures. In 2017, the Indian Council of Medical Research laid down the National Ethical Guidelines for BioMedical and Health Research involving Human Participant for research protocols, which the MHCA advocates. This article gives an overview on the evaluation of consent in clinical practice and also highlights the approach and challenge in psychiatric practice in India.

Keywords: Consent, Ethics, India, Law, Psychiatry

INTRODUCTION

Consent is a process that allows for free expression of an informed choice, by a capable person to participate in a treatment or a study.[1] The primary purpose of consent is to uphold an individual's autonomy and the right to choose by rational decision-making. It is one of the most important components of health-care delivery and biomedical research today.[2] Informed consent involves clinical, ethical, and legal dimension pertaining to all the medical intervention.[3,4] Consent is a process of communication between two parties, in which a person grants permission for the proposed treatment or research intervention based on realistic expectations of the potential risks and benefits. It is an obligation on a service provider to communicate to service seeker about the need for such medical or surgical intervention, and other alternate options, realistic expectations of each intervention, based on the potential risks and benefits and helping the service seeker to choose an appropriate intervention without undue influence or coercion. Consent is believed to improve the autonomy of the individual, the therapeutic alliance and treatment compliance.

EVOLUTION OF CONSENT IN INTERNATIONAL SCENARIO

In the Hippocratic era, benevolent paternalism was practiced, he preached “speak to the patient carefully and adroitly, concealing most things.”[5] Providing benefit to the patient and avoiding harm were chief concerns while full disclosure was considered harmful. However, research of historical sources has indicated that Hippocrates advocated seeking the patient's co-operation in order to treat. Later Plato, in ancient Greece, connected consent with the quality of a free person.[6,7] In Alexander the Great's era and in Byzantine times, not only was the consent of the patient necessary, but physicians were demanding more safeguards before undertaking a difficult operation due to fear of consequences. Consent was an important part of the process of treatment and a few physicians sought permission, perhaps due to respect for their patients or fear of consequences.[6]

In the 1940s, a series of research abuses took place in Tuskegee, Alabama.[8] In a study of the natural history of untreated syphilis in impoverished African-American males, the participants were not informed of their disease and denied medication even after a treatment became available in 1947. The abuses and unethical methods were revealed in 1972 which led to the Congress of the United States of America to pass the National Research Act[9] and create a commission to study and frame regulations governing studies involving the human participants.

In 1947, Nazi physicians were tried at Nuremberg, Germany, for research atrocities such as drug trials performed without consent, on prisoners of the war and captives at concentration camps. This resulted in permanent physical or mental damage and even death of the participants. This is famously known as “Doctors’ trial.” The United States Military court and tribunal laid down ten points of the Nuremberg Code for a legitimate clinical trial.[10] It was the first internationally recognized code of ethics in research. The heart and soul of the Nuremberg code were that, it made voluntary consent from the participant mandatory before the drug trial/research. The code is considered to be one of the most important documents in the history of clinical research ethics, which had a great influence on human rights globally.

However, it was felt that the Nuremberg Code was skeletal, inadequate, and needed an update. Hence, the World Medical Association formulated ethical guidelines for medical research which is famously known as “Declaration of Helsinki” on June of 1964 in Helsinki, Finland.[11] The declaration emphasized the distinction between medical care that benefits the patient and research that may or may not provide benefit. The original text of the Declaration of Helsinki had 11 principles and later had a total of 36 principles in it. The Nuremberg Code and the Declaration of Helsinki are the basis for the Code of Federal Regulations[12] which are the regulations issued by the United States Department of Health and Human Services for the ethical treatment of human subjects.

In addition, the idea of informed consent is universally accepted and now constitutes Article 7 of the United Nations’ International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This also served as the basis for the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research involving human subjects proposed by the World Health Organization, in collaboration with the Council for International Organization for Medical Sciences (CIOMS).[13] In 1976, the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioural Research published the Belmont report. It outlines the basic ethical principles that should be respected while conducting biomedical and behavioral research involving human subjects. It mainly revolves around three governing principles of respect for participants, beneficence, and justice.[14] Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research by CIOMS[15] are the ethical standards for informed consent. These are universally applicable today in research.

CONSENT AND INDIA

The Medical Council of India, Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics Regulations, 2002[16] discusses about consent for treatment intervention and surgical procedure and requirement of consent for various medical interventions such as obstetric care, surgical procedure, sterilization procedure, abortion, in vitro fertilization, and artificial insemination. To consent for any above-mentioned medical/surgical intervention, it is required that the patient is competent to enter a contract. This gives rise to contractual obligations during the consenting process. Hence, in accordance with the Indian Majority Act, parties are considered competent if (i) they have attained the age of 18 years, (ii) they are of sound mind, and (iii) they are not disqualified by any law to which they are subject to. Furthermore, there is a stipulation in the contract law stating that the consent of any party (in our case it is the patient) that is obtained by coercion, undue influence, mistake, misrepresentation, or fraud, will render the agreement invalid. In addition, the Supreme Court of India (Samira Kohli vs. Dr. Prabha Manchanda and Another (2008) 2 Supreme Court Cases 1)[17] defines consent in the context of a doctor–patient relationship, as “the grant of permission by a patient for an act to be carried out by a doctor, such as a diagnostic, surgical, or therapeutic procedure.”

The Mental Healthcare Act (MHCA), 2017 in section 22 has specified the details of the information a person with mental illness (PMI) is entailed while obtaining informed consent. It entitles the patient to seek the information on the nature of mental illness and the proposed treatment plan, including the known side effects of the proposed treatment, prognosis of the disorder with and without the treatment offered, right to refusal of treatment, criteria of admission and related provision/section, and the right to withdraw consent. He/she should receive the information in a language and form that they can understand.[18] However, it does not mention the extent of information on the mental illness and the required intervention to be disclosed to patients, but earlier Supreme Court Judgement (Samira Kohli) says that “When a doctor is specifically questioned by the patient about the risks involved in a particular treatment proposed, the doctor's duty is to answer truthfully and completely answer the patient's doubts. Remote risk of harm (referred to as, risk with a probability of 1%–2%) need not be disclosed, but if the risk of harm is substantial (with a probability of 10% or more), it may have to be disclosed.”[19]

TYPES OF CONSENT

Informed versus real consent

The law of consent in medicine is governed by two major schools of thought. One is the doctrine of “informed consent,” according to which it is the doctor's responsibility to disclose all the necessary information to the patient to secure consent. This is the “reasonably prudent patient” test[20] which was evolved in Canterbury. According to the prudent person rule, a patient must know and understand the diagnosis. The nature and purpose, known risks, and consequences of the proposed treatment, excluding those consequences that are too remote and improbable or too well known to bear on the treatment decision. It also requires that the patient is made aware of success and failure rates with the proposed treatment and “judgment errors made in the course of care if such information affects the care of the patient.” The benefits expected of the proposed treatment and the likelihood of their being realized. They also need to know of all alternative treatments, with all the information about them including the risks, consequences, and success rate of the doctor and the hospital. The patient should be made aware of the prognosis if no treatment is given and all costs and burdens of the treatment and of the alternatives offered.[21]

Under the doctrine of “real consent” which is derived from the Bolam's test, the doctor must warn his patient of the risks inherent in the recommended treatment and the terms of giving such warning must be in accordance with the practice accepted at that time as considered proper by a responsible body of medical practitioners skilled in that particular field.[19] According to the Bolam's test, to term an act of a doctor as negligent, we should consider the act of another doctor in the similar circumstances and facilities as existed with the treating doctor. Furthermore, the professional knowledge and skill of the treating doctor should be compared with another doctor having same educational background.[22] In simple terms, it means doctors will be held to a standard of care that is commonly practiced by an average doctor at that particular time.

Implicit versus explicit consent

Implied or implicit consent – Here, the consent is not expressed but is implied through an act of the consented (e.g., A person entering a consultation chamber on their own volition; submitting themselves for clinical examination)

-

Explicit consent: The consent is expressed in clear terms either verbally or in writing

- Verbal explicit consent is needed to conduct an intimate noninvasive examination (e.g., Vaginal examination, breast examination, etc.)

- Written explicit consent is needed when an invasive procedure is to be done (e.g., Drawing of body fluids and procedures which require an incision of skin).[23]

ELEMENTS OF A VALID CONSENT PROCEDURE

A valid consent should have the following three elements such as (a) voluntariness, (b) information, and (c) competency

Voluntariness: Voluntariness encompasses the individual's ability and autonomy to act on his/her own accord, with one's sense of what is best in light of one's situation, values, and history. It is participation by their own volition, that is, freedom to decide without being subject to undue influence. For the consent to be considered legally voluntary, it must be given freely by the patient and without the presence of any form of coercion, fraud, or duress that impinges on the patient's decision-making capacity. In evaluating, the court typically examines all the relevant circumstances, including the doctor's manner, the environmental conditions, and the mental state at the time of obtaining consent

Information: A clinician must provide the following minimum information before obtaining consent: information on nature of the disorder, prognosis of the disorder with and without treatment offered, alternate treatment options available, why a specific treatment is being offered and drawbacks of the same.[20,24] He/she should be made aware of their right of withdrawal of consent, that is, the patient understands that the consent could be withdrawn at their will

Competency: Competency is a broad multidimensional construct which encompasses many different legal issues and contexts. There are no firmly established criteria to determine a patient's competence, as it is task specific and not a global entity. However, McArthur's Competency Assessment Tool for treatment (MacCAT-T)[25] is an option the clinicians can use to assess competency for treatment. While assessing competency, a clinician should make an effort to examine whether a person has comprehension of the information provided, understanding of being ill, need for treatment, and understanding the nature of each treatment option and its consequences. After which, he/she has to finally weigh the risk and benefit of each treatment modality by rational decision-making process and communicate back the choice of decision to the clinician.[26]

ALTERNATIVES TO CONSENT

In health-care delivery, various “methods” are being utilized to obtain permission from the patient to administer a particular treatment or procedure. Although not ideal or ethical, they are commonly practiced. They are (a) assent, (b) persuasion, and (c) coercion.

Assent is the acceptance of an approach or positive action that is offered without the full and comprehensive exploration of the alternatives[24]

Persuasion is defined as the clinician's aim “to utilize the patient's reasoning ability to arrive at a desired result”[21]

Coercion occurs “when the doctor aims to manipulate the patient by introducing extraneous elements which have the effect of undermining the patient's ability to reason.”[27] Coercion in psychiatric care is common[28] and usually seen in use of restraints, involuntary treatment, involuntary admission, seclusion, outpatient commitment, and surreptitious treatment.[29] The MHCA, through its emphasis on autonomy, aims to improve the coercive practices in psychiatric care.

CONSENT IN INDIAN MENTAL HEALTH CARE AND RESEARCH

Definition of consent: MHCA 2017 has an elaborate definition of consent and introduces the concept of “Informed Consent.” According to section 2 of the MHCA, “informed consent” means consent given for a specific intervention, without any force, undue influence, fraud, threat, mistake or misrepresentation, and obtained after disclosing to person adequate information including risks and benefits of and alternatives to the specific intervention in a language and manner understood by the person[20]

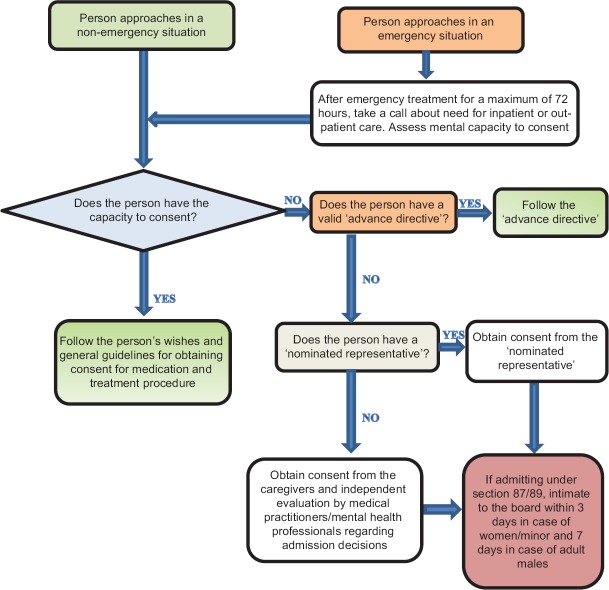

Informed consent in admission and treatment: Through the concepts of mental capacity and informed consent, MHCA 2017 emphasizes the patient's autonomy and meaningful participation in all treatment-related decisions. MHCA presumes that all the persons with mental illness (PMI) have the capacity to make decisions regarding their mental health care. The onus is on the mental health professional (MHP) to prove otherwise. MHCA mandates the procedure of informed consent for indoor admission, ECT (Electroconvulsive therapy), and discharge planning. As per section 96 of MHCA, in case of psychosurgery and ablative procedures, in addition to the informed consent, an opinion from an independent expert board, and permission from the Mental Health Review Board (MHRB) is also required. Table 1 describes the related sections and the consenting person and Figure 1 details the process of informed consent for admission and treatment as per the MHCA. However, as per section 94 of MHCA, a registered medical practitioner is allowed to provide/administer emergency treatment for PMI, after obtaining an informed consent from the nominated representative (NR) if available

Informed consent in clinical research: The MHCA in section 99 describes the requirements of the informed consent procedure related to clinical research. It mandates a specification of the nature of study as in psychological, physical, chemical, or medical intervention, and also gives the participant the right to withdraw the consent at any time during the research period. It mandates that informed consent should be obtained from the patient under his/her free will. In the case of persons who do not resist the participation but are unable to give free, informed consent, permission should be obtained from concerned state authority.

Table 1.

Type of admission and consenting person

| Section | Details | Consenting person | Inform to MHRB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Section 86 | Independent admission and treatment | PMI himself | No need to inform MHRB |

| Section 87 | Admission of minor | Guardian/Nominated Representative | Inform the board within 72 h |

| Section 89 | Admission and treatment of persons with mental illness, with high support needs, in mental health establishment, up to 30 days (supported admission) | Nominated representative | Inform the board within 72 h in case of women, minor. 7 days for others |

| Section 90 | Admission and treatment of persons with mental illness, with high support needs, in mental health establishment, beyond 30 days (supported admission beyond 30 days) | Nominated representative and permission from MHRB | Inform the board within 7 days |

MHRB – Mental Health Review Board; PMI – Person with mental illness

Figure 1.

Informed consent for admission and treatment as per Mental Healthcare Act

NR is allowed to give consent, in cases where the patient is not able to give informed consent, if the state authority is satisfied with the necessity, intention, interest, guidelines, and regulation of the study. It also allows using the case records of such patients, as long as the anonymity of the patient is maintained.[18]

In addition, the MHCA 2017 mandates scientist/researcher to adhere to the “National Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical and Health Research Involving Human Participant,” 2017, laid down by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR).[30] Any violation of the existing ICMR guidelines, including not obtaining a valid informed consent constitutes misconduct. For research in vulnerable population, ICMR guidelines place more responsibility on all stakeholders, that is, researchers, ethics committees, and sponsors, be it, an appropriate government, an institution, or a pharmaceutical company. Justification has to be provided about the need for inclusion of the vulnerable groups, assent and consent from caregivers/NR need to be obtained. Additional care needs to be taken to preserve the confidentiality and the data of such population as any unauthorized disclosures might lead to increase in the vulnerability.

According to the ICMR, the ethical committee may grant waiver of consent in the following situations:[30]

(a) If the research cannot practically be carried out without the waiver and the waiver is scientifically justified; (b) In retrospective studies, where the participants are de-identified or cannot be contacted; (c) In research involving anonymized biological samples/data; (d) In certain types of public health studies/surveillance programs/program evaluation studies; (e) In research on data available in the public domain; or (f) In research during humanitarian emergencies and disasters, when the participant may not be in a position to give consent [Box 1].

Box 1.

An informed consent form for clinical research must include the following: As per the Indian Council of Medical Research guidelines

| • Statement mentioning that it is research |

| • Purpose and methods of the research in simple language |

| • Expected duration of the participation and frequency of contact with estimated number of participants to be enrolled, types of data collection, and methods |

| • Benefits to the participant, community, or others that might reasonably be expected as an outcome of research |

| • Any foreseeable risks, discomfort, or inconvenience to the participant resulting from participation in the study |

| • Extent to which confidentiality of records could be maintained, such as the limits to which the researcher would be able to safeguard confidentiality and the anticipated consequences of breach of confidentiality |

| • Payment/reimbursement for participation and incidental expenses depending on the type of study |

| • Free treatment and/or compensation of participants for research-related injury and/or harm |

| • Freedom of the individual to participate and/or withdraw from research at any time without penalty or loss of benefits to which the participant would otherwise be entitled |

| • The identity of the research team and contact persons with addresses and phone numbers (for example, Principal Investigator (PI)/Co-PI for queries related to the research and Chairperson/Member Secretary/or helpline for appeal against violations of ethical principles and human rights). |

| The Indian Council of Medical Research guidelines also mention that the following may be required depending on the type of study: |

| • Any alternative procedures or courses of treatment that might be as advantageous to the participant as the ones to which she/he is going to be subjected |

| • If there is a possibility that the research could lead to any stigmatizing condition, for example, HIV and genetic disorders, provision for pretest and posttest counseling |

| • Insurance coverage if any, for research-related or other adverse events |

| • Foreseeable extent of information on possible current and future uses of the biological material and of the data to be generated from the research. Other specifics are as follows: |

| i. Period of storage of the sample/data and probability of the material being used for secondary purposes |

| ii. Whether material is to be shared with others, this should be clearly mentioned |

| iii. Right to prevent use of her/his biological sample, such as DNA, cell-line, and related data at any time during or after the conduct of the research |

| iv. Risk of discovery of biologically sensitive information and provisions to safeguard confidentiality |

| v. Post research plan/benefit sharing, if research on biological material and/or data leads to commercialization |

| vi. Publication plan, if any, including photographs and pedigree charts[30] |

An attempt should be made to obtain the participant's consent at the earliest.

-

d.

Informed consent in special populations:

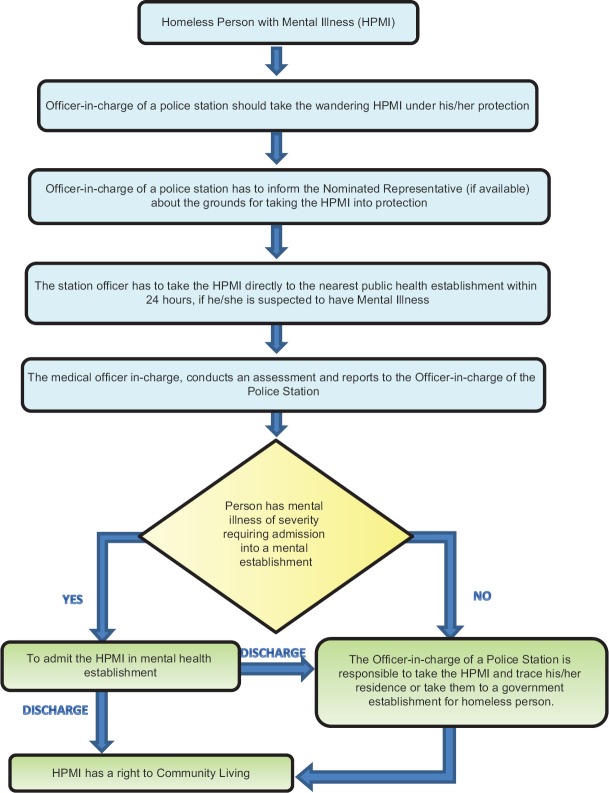

- Homeless person with mental illness: The following Figure 2 explains the protocol in the care of homeless person with mentally illness (HPMI) and the role of the police and medical officer/psychiatrist under the section 101 of MHCA. The officer-in-charge of a police station can produce a HPMI, who has a risk of causing harm to self, others and inability to care of himself/herself; to the magistrate. The law also accords the public, a privilege to report about PMI who are being ill-treated or neglected by their caregiver. The magistrate, if satisfied, can issue a written order to admit and treat such person to a mental health establishment (MHE) for a period of maximum 10 days. The medical officers should assess, treat the PMI, and submit a report to the magistrate at the end of their stay at the establishment

- Mentally ill prisoners: In MHCA 2017, there is no clarity on the consenting procedure for prisoners who lack capacity. Should they be treated like other PMI as per MHCA when it comes to treatment-related decisions? What are the rights of prisoners with mental illness? These are some of the questions which need to be answered by appropriate authorities. However, there is a need to keep prison authority, MHRB in the loop in cases where prisoner with MI loses capacity

- Minors: MHCA places the responsibility of decision-making of minors on the NR. The NR has to make all admission-, treatment-, and discharge-related decisions. For admission of a minor in a MHE, a written request has to come from the NR. The medical officer in-charge/MHP will take a call regarding the admission after individual assessments from two psychiatrists or a psychiatrist and a MHP/medical practitioner. The same has to be informed to the MHRB within 72 h. The MHRB may review the case record/interview and examine the minor if it so desires. MHCA does not clarify the role of assent in the minors between 12 and 18 years of age. What if an adolescent with some decision-making ability is in conflict with the NR with regard to admission- and treatment-related decisions? The role and rights of an adolescent in choosing a NR, are not clarified. Perhaps, in such situations, one can rely on MHRB for conflict resolution.[24]

Figure 2.

Protocol for the care of Homeless Person with Mental Illness

LAW AND INFORMED CONSENT

Law looks at the medical practitioner as someone who has power over the patient and hence any intervention done without a valid informed consent will be interpreted as negligence by the law, even if it was in the best interest of the person. In such cases, medical practitioner can be held liable both by tort and criminal law. A lot of cases of medical negligence have been due to failure to obtain a valid written informed consent. With so much at stake for a medical practitioner, guidelines for assessment of mental capacity and to obtain informed consent will go a long way in making their jobs easier.

CHALLENGES IN OBTAINING INFORMED CONSENT IN PSYCHIATRIC CARE

Consent is a complex procedure which requires the person to have a certain level of competency and decision-making ability. This task is further complicated by the fact that in people with mental illness, especially those with chronic illnesses, there is some cognitive dysfunction, absent insight into illness, and influence of psychopathology which may impair the decision-making ability. The task of clinician in obtaining a valid informed consent becomes more challenging and a herculean task in PMI.

Role of psychopathology

A person with acute psychosis with ability to understand, retain, and comprehend the information offered might have psychopathology which colors his/her decisions. Just the presence of a delusion is not enough to declare a person incapacitated, the onus is on the clinician to demonstrate that the delusion affects his/her decision-making ability. Similarly, a person with nihilism may not weigh all the consequences and give consent for a procedure, for which he/she may not have consented otherwise. How does a MHP demonstrate conclusively that the PMI does not have mental capacity to consent? How does one demonstrate that PMI has psychopathology which is affecting their decisions? Perhaps, these are some of the many questions which need to be answered.

Role of insight

Insight plays a major role in informed decision-making process, as the person has to recognize his/her illness and make a rational decision based on the risks and benefits. In person with absent insight or partial insight, their decision-making ability will be impaired due to poor recognition of illness symptoms. It will be more challenging in persons with delusional disorder and chronic PMI who have poor treatment response. Despite knowing this, the lawmakers have not made special provisions to address capacity assessment for treatment decision under MHCA 2017. Therefore, it is important for the central mental health authority to make provision/guideline addressing this burning issue in the treatment process.

Emergency treatment

The MHCA allows emergency treatment of mentally ill under section 94, without his/her consent; however, it is required to obtain consent from the NR if available. Getting an informed consent from the NR in an emergency situation might be a challenge for both the MHP and the NR because of the nature of emergency. The act, while discouraging the use of physical restraints, gives the MHP the power to apply physical restraint before obtaining the consent of the NR; the MHE has to inform the NR about the use of restraints within a period of 24 h and also give a monthly report to the MHRB mentioning all the instances of restraints.

Guardianship among homeless person with mental illness

Care of homeless person with mentally illness (HPMI) is a multifaceted social problem with multiple stakeholders. The MHCA is not clear about the role of consent and capacity assessment when it comes to admission- and treatment-related decisions, when HPMI lose the capacity. Furthermore, there is no clear hierarchical structure of public stakeholders responsible for the care of HPMI with absent capacity. In the absence of which the HPMI are at the mercy of various stakeholders who may pass the buck from one to another which may result in inadequate care of HPMI. The Central Mental Health Authority/State Mental Health Authority has to come up with clear rules and guidelines with a clear hierarchical structure of public stakeholders responsible for the care of HPMI.

Guardianship of adolescents with mental illness

When it comes to treatment-related decisions of the adolescents, the act is unclear as who has the final say. What if the assent of the adolescent is in conflict with the consent of the guardian/NR? The MHRB has some role in conflict resolution, but it may be a drawn out process that can result in loss of quality time and resources.

Guardianship of people with mental retardation

The section 14 (provisions for guardianship) of RPW act,[31] articulates the provisions of limited guardianship and total guardianship in person with mental disability like mental retardation. A person with a mental disability can seek “guardianship” depending on the extent of support they require which is based on their legal capacity. If a person with mental retardation is unable to take legally binding decisions due to incapacity, then he/she may be provided with further support of a limited guardian to take legally binding decisions on his/her behalf in consultation with such person with disability. In certain other situations, the designated authority may grant total guardianship.[32,33]

Persons with dementia and other major neurocognitive disorder

In person with dementia and major neurocognitive disorder (MNCD) associated with cognitive decline and poor cognitive reserve, the impairment in retention of information and rational decision-making process may impact the consenting procedure. They may need support in decision-making, either partially or completely by NR/guardian and caregivers; in some instances, conflicts between the caregivers and NR may arise. The MHRB has to play a role in conflict resolution, but it may lead to loss of quality time and resources [Box 2].

Box 2.

General guidelines to follow while obtaining an informed consent[26]

| • Assessment of mental capacity to consent has to be done |

| • Consent process should be done in a comfortable environment, ideally in the presence of the nominated representative or a neutral witness |

| • Ensure that the person is consenting out of free will with no coercion, persuasion, and undue pressure from either the doctor, family members, nominated representative (NR), or others |

| • Adequate information about the nature of mental illness, the proposed treatment plan, including its rationale, the known side effects of the proposed treatment, prognosis, and natural progression of the disorder with and without the treatment offered, criteria of admission, and related provision/section of the Mental Healthcare Act (MHCA) 2017 has to be provided |

| • It is not sufficient to state that “the risks and benefits were discussed” without further description of the specifics |

| • Clinician should hold a neutral position while discussing about the treatment options |

| • Clinician should encourage person with mental illness (PMI) to discuss his/her concern about treatment and care |

| • Clinician should uphold the individual autonomy of PMI during the consenting procedure |

| • The treatment options offered should be in accordance with the good practice guidelines and evidence-based medicine. |

| • Information about the alternatives to the offered treatment, its risks, consequences, and costs have to be clearly mentioned |

| • The person needs to understand that the result/outcome of the treatment/procedure cannot be guaranteed and more so to their expectations. The person should also be informed that if immediate life-threatening events happen during the treatment/procedure, it will be treated accordingly |

| • The person has to be educated about the right to refusal of treatment and the right to withdraw consent |

| • The person needs to be informed that they have a right to opt for second/more medical opinion |

| • Authorization for procedural photographs/videos for academic purposes (keeping identity confidential) should be obtained. If the person does not authorize for the same, his/her wishes should be respected |

| • In case of admission, the person has to be familiarized with the infrastructure of the mental health establishment and its rules |

| • He/she should receive the information in a language and form that such person receiving the information can understand |

| • The person has to be given adequate time to contemplate and decide on the options offered |

| • The consent has to be clearly documented in the language the person understands, preferably in his/her own writing |

| • If a person is illiterate, consent form has to be read out in the language he/she understands, and the process has to be videographed. Alternatively, a |

| nominated representative or a legally appointed representative can read out the form and sign for the person. A thumb impression of the consenting person has to be recorded on the informed consent form (ICF) |

| • Signatures of the consenting person, witness, and the person conducting the process have to be documented. Any consent without the signature of the medical practitioner will be considered invalid by the law |

| • In case the consenting person is a minor, the consent has to be obtained from the parent/guardian/NR as per Section 87 of the MHCA, 2017 |

| • If the minor attains the age of 18 during his/her stay in the MHE, then the consent has to be obtained from the person and admission under Section 86 of MHCA has to be done |

| • The person needs to be informed about the estimated cost of the treatment/procedure involved in ordinary circumstances |

| • The person needs to understand that, in case of emergency during the agreed treatment/procedure (s) were to arise, the doctor will undertake such other treatment/procedure(s) as necessitated, keeping in mind their best interest, without necessarily seeking any proxy consent |

| • A copy of the informed consent form has to be given to the person, with the original form filed in the patient’s records; it is advisable to have a hard copy in places where consent process is digitalized |

| • Audio/videographic recording of the consent process can be done after informing the same to the consenting person. If they refuse, their wishes have to be honored and the resistance documented |

| • The date and time of the consent procedure have to be recorded in the ICF and questions asked by the person or concerns raised have to be documented in the ICF |

CONCLUSION

Informed consent upholds an individual's autonomy and the right to choose by rational decision-making. The MHCA places a lot of onus on the autonomy of the PMI, with informed consent being a foremost necessity. The MHCA 2017 has empowered PMI through rights, autonomy, and minimizing existing medical and social paternalism in Indian health care. Obtaining a valid informed consent becomes more challenging in PMI with absent insight, mental retardation, psychotic symptoms, cognitive dysfunction and incomplete recovery. The MHRB has a significant role to play when there is a conflict with the consent-related issue in mental health care and treatment decision.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nardini C. The ethics of clinical trials. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:387. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2014.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta UC. Informed consent in clinical research: Revisiting few concepts and areas. Perspect Clin Res. 2013;4:26–32. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.106373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar A, Mullick P, Prakash S, Bharadwaj A. Consent and the Indian medical practitioner. Indian J Anaesth. 2015;59:695–700. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.169989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nandimath OV. Consent and medical treatment: The legal paradigm in India. Indian J Urol. 2009;25:343–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.56202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Document 11276040. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 26]. Available from: https://www.studylib.net/doc/11276040/

- 6.Dalla-Vorgia P, Lascaratos J, Skiadas P, Garanis-Papadatos T. Is consent in medicine a concept only of modern times? J Med Ethics. 2001;27:59–61. doi: 10.1136/jme.27.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bury RG. Plato Laws. London: Heinemann; 1926. pp. 212–3. 238-9, 306-9, 454-7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuskegee Study – Timeline – CDC – NCHHSTP. 2018. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 26]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm .

- 9.National Research Service Award Act of 1974. United States of America, PUBLIC LAW 93-348. 1974. Jul 12, [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 11]. Available from: https://www.history.nih.gov/research/downloads/PL93-348.pdf .

- 10.Fifty Years Later: The Significance of the Nuremberg Code NEJM. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 19]. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199711133372006 .

- 11.WMA – The World Medical Association-WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 26]. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declarationof-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-humansubjects/

- 12.Policy & History. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 19]. Available from: http://www.historyandpolicy.org/index.php/policy-papers/papers/patients- r i g h t s -from-alder-hey-to-the-nuremberg-code .

- 13.Gaw A. Reality and revisionism: New evidence for Andrew C Ivy's claim to authorship of the Nuremberg code. J R Soc Med. 2014;107:138–43. doi: 10.1177/0141076814523948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Belmont Report. 2010. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 19]. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/index.html .

- 15.International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 26]. Available from: https://www.cioms.ch/shop/product/international-ethicalguidelines-for-biomedical-research-involving-human-subjects-2/ [PubMed]

- 16.The Indian medical council (professional conduct, etiquette and ethics) regulations, 2002. Issues Med Ethics. 2002;10:66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Supreme Court on Informed Consent in India. The Indian Lawyer. 2018. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 16]. Available from: http://www.theindianlawyer.in/blog/2018/03/10/supreme-court-informed-consent-india/

- 18.Mental Healthcare Act. 2017. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 19]. Available from: https://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/Mental%20Health/Mental%20Healthcare%20Act,%202017.pdf .

- 19.Rangaramanujam A. Liberalizing consent – Supreme court's preference for ‘real consent’ over ‘informed consent’. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2008;18:195–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aggarwal KK. Real consent and not informed consent applicable in India (Part III) Indian J Clin Pract. 2014;25:591–3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yadav M, Thakur PS, Rastogi P. Role of Informed Consent in India; Past, Present and Future Trends. J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 2014;36:411–20. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nandimath OV. Bengaluru: Distance Education Department Post Graduate Diploma in Medical Law and Ethics, National Law School of Indian University; 2017. Medical Professional and Patient - The Legal Relationship. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malhotra S, Subodh BN. Informed consent & ethical issues in paediatric psychopharmacology. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:19–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C. The MacCAT-T: A clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:1415–9. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.11.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Appelbaum PS, Roth LH, Lidz CW, Benson P, Winslade W. False hopes and best data: Consent to research and the therapeutic misconception. Hastings Cent Rep. 1987;17:20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okasha A. Ethics of psychiatry practice: Consent, compulsion, and confidentiality. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2000;13:693–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gowda GS, Lepping P, Noorthoorn EO, Ali SF, Kumar CN, Raveesh BN, et al. Restraint prevalence and perceived coercion among psychiatric inpatients from South India: A prospective study. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;36:10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2018.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah R, Basu D. Coercion in psychiatric care: Global and Indian perspective. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:203–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.70971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ICMR_Ethical_Guidelines_2017.pdf. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 26]. Available from: https://www.icmr.nic.in/sites/default/files/guidelines/ICMR_Ethical_Guidelines_2017.pdf .

- 31.The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, Gazette of India (Extra-Ordinary) 2016. [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 19]. Available from: http://disabilityaffairs.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/RPWD%20ACT%202016.pdf .

- 32.Fisher CB. Goodness-of-fit ethic for informed consent to research involving adults with mental retardation and developmental disabilities. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2003;9:27–31. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balakrishnan A, Kulkarni K, Moirangthem S, Kumar CN, Math SB, Murthy P. The rights of persons with disabilities act 2016: Mental health implications. Indian J Psychol Med. 2019;41:119–25. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_364_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]