Abstract

Homeless persons with mental illness (HPMI) suffer indignities due to shirking of all obligations by the society. In addition, the HPMI is denied all rights available to citizens, such as confidentiality, privacy, safety, right to practice religion, health, and the right to not suffer from inhuman treatment. In this context, the new Mental Healthcare Act (MHCA), 2017 has brought in a list of rights for HPMI, and this is a welcome sign. The MHCA has also taken away the mandated involvement of judiciary to provide care for the HPMI. However, the ground realities in terms of the systems and the existent infrastructure are far from satisfactory to handle the issue in India. The onus of providing care for the HPMI has shifted to the state, and the public agencies are responsible for ensuring the same. The article aims to look at various sections of the MHCA relevant in regard to providing care for the HPMI.

Keywords: Homeless persons with mental illness, homelessness, illness, Mental Healthcare Act 2017

INTRODUCTION

One of the greatest diseases is to be nobody to anybody.

–Mother Teresa.

Every society has an obligation to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, shelter the homeless, care for sick, help the helpless, and finally protect their rights. The role of the society and the responsibility of the state are often diluted, and homeless persons with mental illness (HPMI) suffer indignities due to shirking of obligations by the society. Often, while providing care of the HPMI, there are violations of the fundamental rights such as confidentiality, privacy, safety, right to practice religion, health, and the right not to suffer from inhuman treatment. Homeless persons in our country end up living on the streets, in jails, in beggar homes, or incarcerated in mental hospitals life-long.[1] HPMI represents the end point of a life of suffering from severe mental illness. It is a reflection of the failure of the family and the society to care for such individuals. Homelessness and wandering among those with mental illness are the signs of failure of the system to provide adequate and constant support to such families.

Homelessness, defined as house-less-ness (Census India, 2011), is a state in which persons live in places other than a house with a roof. Although the reasons for these circumstances are many, the combination of mental illness and homelessness is bi-directionally associated. The issue gets entangled with so many other social and economic factors that turn into a vicious cycle, driving the said person into the bottom strata of the society. Considering the population of India and the prevalence of severe mental disorders (which are likely associated with homelessness), the issue becomes one with public health significance.

The number of people who are homeless in India is around 1.77 million based on the 2011 Census.[2] The National Mental Health Survey (NMHS) guestimates the number of HPMIs across various states to be “nil” or “almost minimal” to “1% of mentally ill.” The NMHS estimates the number of HPMI in some states to be as high as “15,000.” The estimates of HPMI varied across districts, cities, and/or states across India according to the NMHS. This not only reflects the key informants’ lack of awareness but also signifies the difficulties in data quantification.[3] Approximately one-fifth of this population has diagnosable severe mental disorders which are severely incapacitating for the individuals, resulting in very poor quality of life.[4]

The NMHS[3] looked at the extent, pattern, and outcome of mental, behavioral, and substance use disorders and the available resources and services. It revealed that mental morbidity above the age of 18 years is 10.6% with a lifetime prevalence of 13.7%. This means that 150 million Indians need active intervention. The treatment gap ranged from 28% to 83% for mental disorders and 86% for alcohol use disorders. Multiple factors such as awareness, affordability, and accessibility that vary in rural and urban areas influence the wide treatment gap. However, when it comes to the human resources and infrastructure, India lags well behind the expected norms. For example, the number of psychiatrists is about 9000[5] which is far from adequate. The Mental Health Atlas of 2017[6] reported a median number of less than two mental health workers per 100,000 population in low-income countries like India. According to the Mental Health Atlas of 2014, the number of clinical psychologists and psychiatric social workers in India was reported to be 0.07 per 100,000, and the number of psychiatric nurses was 0.12 per 100,000.[7] The number of public funded long-stay facilities in India is nil.

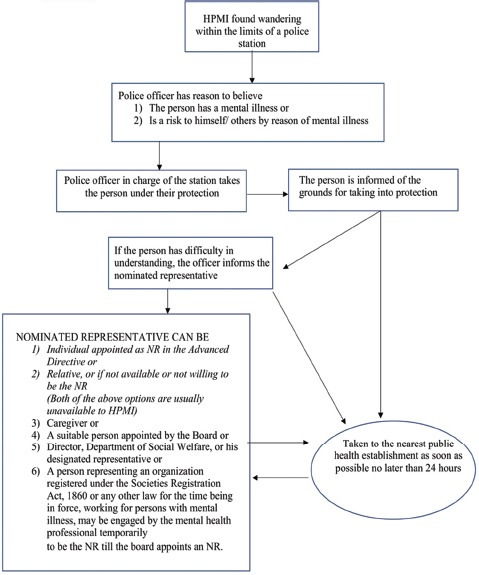

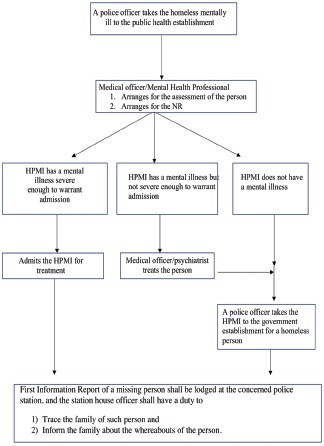

Finally, the ushering of the era of Mental Healthcare Act (MHCA), 2017 could bring in more complexities. For example, a section of the stakeholders believes that the number of HPMI may increase considerably, due to the specific lack of support mechanisms for families caring for those with severe mental illnesses. In the above context, this article discusses the provisions of MHCA, 2017 as applicable to HPMI, specifically mentioning the pathway to care for HPMI (under MHCA, 2017), and concludes by talking about future recommendations [Flowcharts 1 and 2].

Flowchart 1.

Pathways to care for homeless persons with mental illness according to the Mental Healthcare Act of 2017. HPMI – Homeless person with mental illness; NR – Nominated representative

Flowchart 2.

Stages of care of homeless persons with mental illness in the public health establishment. HPMI – Homeless person with mental illness; NR – Nominated representative

MENTAL HEALTH LEGISLATIONS AND THE HOMELESS PERSONS WITH MENTAL ILLNESS

The predecessor of the MHCA, the MHA 1987,[8] had provisions for humane treatment of HPMI: “No mentally ill person shall be subjected during treatment to any indignity (whether physical or mental) or cruelty” (Subsection 1, Section 81 – mentally ill persons to be treated without violation of human rights from Chapter VIII – Protection of human rights of mentally ill persons). However, administrative procedures of admission took precedence over medical assessment and treatment. Section 23 of the MHA 1987 specifically empowered the officer-in-charge of the police station to “take into protection” an HPMI, inform him/her of the grounds for taking him/her into protection, and produce the person before a judicial magistrate within 24 h of taking him/her into protection. The magistrate, as per Section 24, would make necessary inquiries regarding behavior, try to assess the capacity of the HPMI, as well as ask for a medical opinion from a medical officer. If convinced, the magistrate issues a reception order authorizing the detention of the said person as an inpatient in a psychiatric hospital or psychiatric nursing home.

The MHCA, 2017[9] is a rights-based legislation with a lot of obligations cast upon the state with regard to HPMI. Following are the provisions:

Duties of public agencies while delivering care to homeless persons with mental illness

Subsection 7 of Section 100 states that in case of a person with mental illness who is homeless or found wandering in the community, a First Information Report of a missing person shall be lodged at the concerned police station and the station house officer shall have a duty to trace the family of such person and inform the family about the whereabouts of the person (Chapter XIII – Responsibilities of other agencies). If, however, the family is not found, the MHCA designates the officer-in-charge of the police station to “take under protection” of the wandering HPMI in his/her jurisdiction, inform him/her of the grounds for taking him/her into protection, and later take him/her to the nearest public health establishment (not to the magistrate as in MHA1987) as soon as possible but not later than 24 h from the time of being taken into protection, for assessment of the person's healthcare needs. No person taken into protection shall be detained in the police lock-up or prison in any circumstances (Subsections 1, 2, 3, 4 of Section 100). The medical officer-in-charge of the public health establishment shall be responsible for arranging the assessment of the needs of the person (Subsection 5 of Section 100). If the medical officer, on assessment, finds that a person does not have a mental illness of a nature or degree requiring admission to the mental health establishment (MHE), he/she shall inform his/her findings to the police officer who had taken the person into protection, and the police officer shall take the person to the person's residence or, in case of homeless persons, to a government establishment for homeless persons (Subsection 6 of Section 100 – Responsibilities of other agencies; Chapter XIII).

Admission and discharge guidelines for the homeless persons with mental illness

Section 2(p) of the MHCA 2017 defines MHEs as any health establishment, spanning across various systems of medicine, which are established, owned, controlled, or maintained by the appropriate government, local authority, trust, private or public, corporation, co-operative society, organization, or any other entity or person, where persons with mental illness are admitted and reside at, or kept in, for care, treatment, convalescence, and rehabilitation, either temporarily or otherwise, and includes any general hospital or general nursing home established or maintained by the appropriate government, local authority, trust, whether private or public, corporation, co-operative society, organization, or any other entity or person. This would prove beneficial to people and organizations involved in the care of homeless mentally ill, provided the person/organization is registered with the concerned authority according to the provisions laid down in Chapter X of the Act.

If the person is found to have a mental illness of a nature or degree which requires admission to the MHE, the person is admitted and the treatment part will be addressed as per other provisions of the act (Section 86: admission as independent patient, if the person agrees and if the physician thinks that the admission would benefit the patient). In case the patient does not agree for admission voluntarily, then admission can happen in line with the provisions required for admissions with high supported needs.

A key person in these Sections 89 and 90 is the nominated representative (NR). The HPMI obviously has been found wandering; there is the absence of advance directives, NRs, and relatives or caregivers. A suitable person appointed by the Mental Health Review Board, or Director of Department of Social Welfare, who are next in line to be appointed, too will not be available in the acute situation when the police brings the HPMI to a public health establishment. Hence, the absence of an NR at the time of contact with the MHE may prove an issue for admissions under Sections 89 and 90. However, another clause, subsection[4] of Section 14, states that a person representing an organization under the Societies Registration Act, 1860 or any other law for the time being in force, working for persons with mental illness, may temporarily be engaged by the mental health professional to discharge duties of a NR pending appointment of one by the concerned board. The representative from the Rogi Kalyan Samiti in the hospital can also be the NR. The doctor needs to obtain consent from such a person, indicating their willingness to act as the temporary NR. One possible interpretation of this section is that the resident/doctor who is treating the HPMI could act as the NR till a nomination is received from the Board. This could be a very temporary measure as there would be issues of conflicts of interest.

Emergency treatment may be provided for 72 h even in the absence of an NR. The Section 19 (Rights of persons with mental illness; Chapter V) clarifies that “every person with mental illness shall not continue to remain in a MHE merely because he/she does not have a family or is not accepted by his/her family or is homeless or due to absence of community-based facilities.” An HPMI who has improved with treatment and is deemed fit to be reintegrated to the community cannot be kept in the MHE.

In MHA 1987, Section 44 dealt with the discharge of such patients. “If any person detained in a psychiatric hospital or psychiatric nursing home in pursuance of a reception order made under this Act is subsequently found, on an inquisition held in accordance with the provisions of Chapter VI, to be of sound mind or capable of taking care of himself and managing his/her affairs, the medical officer-in-charge shall forthwith, on the production of a copy of such finding duly certified by the District Court, discharge such person from such hospital or nursing home.” In MHA 1987, it was not possible to discharge an HPMI without a certificate from the District Court. However, in the MHCA 2017, the medical officer “informs” the police officer, who later, in accordance with the act, reintegrates him/her to the family or a less restrictive environment or a government establishment for homeless persons (Section 100, Subsection 6). There is no involvement of the judiciary in either admission or discharge of HPMI.

Right to free legal aid

The law has enabled a person with mental illness to obtain free legal aid. This section will be useful to establishments who care for HPMI. Many institutions working and caring for HPMI find it difficult to place the HPMI back to the family, not because the family has not been found, but due to the reluctance of the family to take back the HPMI even after significant improvement in illness and disability. The reasons could be stigma, fear, or reluctance to take care or lack of resources to continue the care. Section 27 Subsection 2 mandates the treating mental health professional to educate the HPMI of his right to free legal aid. “It shall be the duty of magistrate, police officer, person in-charge of such custodial institution as may be prescribed or medical officer or mental health professional in-charge of an MHE to inform the person with mental illness that he/she is entitled to free legal services under the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 (39 of 1987) or other relevant laws or under any order of the court if so ordered and provide the contact details of the availability of services.”

Rights of persons with mental illness in relevance to homeless persons with mental illness

The HPMI enjoy other rights like that of fellow sufferers of mental illnesses. For example,

Section 18 (Rights of persons with mental illness; Chapter V) states: “persons with mental illness living below the poverty line whether or not in possession of a below poverty line card, or who are destitute or homeless, shall be entitled to mental health treatment and services free of any charge and at no financial cost at all MHEs run or funded by the appropriate government and at other MHEs designated by it.” This entitlement to be treated free of charge empowers volunteers and nongovernmental organization to help the HPMI by taking him to medical establishment run or funded by the government, without fear of financial commitment

Section 19 – Rights to community living: Subsection-2 – makes it mandatory for the government to ensure the reintegration of the HPMI to his/her family home. “Where it is not possible for a mentally ill person to live with his family or relatives, or where a mentally ill person has been abandoned by his/her family or relatives, the appropriate Government shall provide support as appropriate including legal aid and to facilitate exercising his/her right to family home and living in the family home.” Subsection 3 states, “The appropriate Government shall, within a reasonable period, provide for or support the establishment of less restrictive community-based establishments including half-way homes, group homes, and the likes for persons who no longer require treatment in more restrictive MHEs such as long-stay mental hospitals.” Both the above sections mandate the government to provide care and rights-based community living for HPMI. The public health system should consider other community alternatives such as shared homes or clustered group homes created in the community. These facilities are not restricted, but inclusive community living options which promote a better quality of life and participation in the community activities and help to achieve economic independence by finding work and to subsequently achieve community integration.

In addition, Section 95 (d) prohibits chaining in any manner or form whatsoever while delivering care to the person with mental illness. Further, Section 97 bans seclusion or solitary confinement and provides guidelines for the use of physical restraints. The Act is true to its nature of delivering care in the least restrictive manner and makes sure that the care is delivered with dignity to HPMI.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Even before the MHCA 2017 came into existence, its predecessor and guiding force, the National Mental Health Policy, 2014 talked about homelessness. While recognizing that the facilities are nonexistent for HPMI in India, it went on to mention universal access to mental health care and a rights-based approach to comprehensive mental health care. In continuation, MHCA 2017 has brought in a list of rights for HPMI, and this is a welcome sign. On the one hand, the MHCA 2017 has taken away the involvement of the judiciary to provide care to the HPMI. This is a welcome move and simplifies the process of providing care for the HPMI by preventing untoward delays. However, on the other hand, ground realities in terms of the systems and the existent infrastructure are far from satisfactory. Further work needs to involve all stakeholders to realize the true spirit of the Act. Apart from the speedy and strict implementation of its provisions, public–private partnerships are another way forward. There is an urgent need to invest in community facilities such as halfway homes, daycare centers, home again facilities, and clustered group homes. Further, there is a need to support families by exploring innovative approaches to strengthen them. One such effort is to incentivize care by the family. Emphasis on early treatment for all people with psychotic episodes is critical to address many problems that may arise following the onset of psychosis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.The Hindu : National : Mental Health & Homelessness. [Last accessed on 2018 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/thehindu/2004/10/10/stories/2004101002161100.htm .

- 2.Census of India: Reference Material. [Last accessed on 2018 Dec 16]. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/Ad_Campaign/Referance_material.html .

- 3.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao GN, Pathak K, Singh LK, et al. Bengaluru: National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences; 2016. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16: Prevalence, Patterns, and Outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Among Homeless, Over 1 Lakh have Mental Health Issues | Delhi News – Times of India. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 02]. Available from: https://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/67401774.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest and utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst .

- 5.Garg K, Kumar CN, Chandra PS. Number of psychiatrists in India: Baby steps forward, but a long way to go. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:104–5. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_7_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Mental Health Act. 1987. [Last accessed on 2018 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.indiankanoon.org/doc/185191195/

- 9.Mental Healthcare Act. 2017. [Last accessed on 2018 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/Mental%20Health/Mental%20Healthcare%20Act,%202017.pdf .