Abstract

The World Health Organization Atlas reveals lower bed and mental health professionals ratio per population in India. This may be due to a poor allocation of funding in the mental health sector by the Government. This resulted in a lack of complete and comprehensive care ranging from acute treatment to long-term rehabilitation throughout the country. The spiral of specialist care needs such as deaddiction, child psychiatric needs, and rehabilitation facility are available only to a handful of the population in metropolitan cities in India. The launching or establishment of new Mental Health Establishments (MHEs) and upgrading mental health service may provide strategies to bridge this gap from the private mental health sector. Following the inception of “Mental Healthcare Act 2017” (MHCA 2017), the process of setting up MHEs and their operations comes with new legal and healthcare aspects that remain debatable and unsettled. We put forth the basic measures that can be considered and undertaken to establish an exemplary MHE under the MHCA 2017.

Keywords: India, Mental Healthcare Act 2017, mental health establishment, mental health professional, psychiatrist

INTRODUCTION

The Mental Health Atlas 2017, from the World Health Organization (WHO), showed that India has an extremely low bed allocation to mental health (2.04 beds/100,000 population) compared to the rest of the world. However, in high-income countries like the United States, there are 30.6 beds for psychiatric care per 100,000 populations; in France 125.55, in Australia 41.08, in Malaysia 24.85, in Thailand 8.32, and in China 24.29.[1] The recent National Mental Health Survey 2016 revealed an overall treatment gap of 83% for any mental health problem. This was consistent with earlier reports from India. Gap reported for common mental disorders (85.0%) was higher compared to that for severe mental disorders (73.6%). In addition, the gap was >80% for any suicidal behavior and >90% in the case of substance abuse.[2] Causes attributed to the treatment gap are poor awareness and perceived need, stigma, sociocultural beliefs, and values; with additional factors, including insufficient, inequitably distributed, and inefficiently used resources.[3,4,5] Initiation of the Mental Health Establishments (MHEs) by qualified mental health professionals (MHP) would not only assist in reducing the mental healthcare burden but also provide the MHPs with a timely role in considerably contributing to mental health from the private sector. However, changing times and wake of the new Mental Healthcare Act (MHCA), 2017 has impacted setting up an MHE in India. We discuss the process of initiating, founding the framework, and managing an MHE in India.

THE WHY? WHEN? WHERE? AND WHO? QUARTET

With growing mental health concerns, there is an immense need in the community for mental health services. Mental health needs in the country can be classified into (i) Out-patient care; (ii) In-patient care for acute psychiatric conditions; (iii) Community rehabilitation for chronic mental disorders; (iv) Primary care psychiatry in primary health care; (v) Women's mental health; (vi) Children and adolescents mental health (vii) Disaster mental health for special groups such as refugees and survivors of disasters, (viii) Suicide helpline for persons attempting suicide and farmer suicide (ix) Hospital-based rehabilitation for institutionalized patients; (x) Preventive and promotive mental health (xi) Geriatric mental health (xii) Forensic and legal mental health and (xiii) Deaddiction care.[6,7,8,9,10,11] Furthermore, the professional need concerning the ratio of psychiatrists to the burden of mental illness in the country remains skewed, with a national deficit value of 77%. The WHO reports 43 government-funded hospitals in India which cater to an estimated 70 million plus people with mental disorders. For every million population, there are three psychiatrists, and even fewer psychologists.[1,12] The WHO data also suggests that in India, the number of psychiatric beds per 10,000 patients in psychiatric hospitals is 1.490, and in general hospitals, it is 0.823. Underfunding in terms of government allocated expenditure for health is 1.4% of the gross domestic product (GDP), tagged as one of the lowest in the global scale, and although the private sector accounts for double of the contribution of the public sector, the total remains 5%–6% of GDP, with mental health receiving 1%–2% only.[13] Among the trained psychiatrists in India, approximately 3/4th work in the private sector serving in out-patient and in-patient settings. Bed strength for psychiatric care is currently low even in the private sector; however, if more professionals apply this impetus to bring about well-functioning MHE's, we can hope for improvements in future. The MHCA 2017 emphasizes mental health for all, and founding more MHE's would be a step in this spirit.

WHO CAN START?

The initiation of setting up an MHE may fall upon the psychiatrists and allied professionals in mental health, i.e., clinical psychologists and psychiatric social workers. Nongovernment organization (NGO) or even an individual MHP may wish to set up an MHE. In the event of an individual taking up such an endeavor, the question of when to commence is often asked. Whether a foray into founding an establishment would be fruitful right at the dawn of one's career or at the end remains a question, but we find the 40s–50s being the ideal time to venture into this. This is the period wherein the balance between fledgling tracks and skillful readiness is reached.

DO THEY NEED ADDITIONAL SKILLS APART FROM PSYCHIATRIC EXPERTISE?

While running an MHE, the professional's would require certain skill-sets apart from psychiatric expertise, namely proactiveness, determination, public speaking abilities, administrative capacity with the ability to handle financial risks, availability of financial capital, and a large investment of time and energy. The possibility of delayed rewards as well as the dual role of clinician/founder itself must be appealing to the professional. Having embarked on this journey, selecting one's area of the venture; be it rural, semi-urban or urban; then weighing the opportunities and obstacles that come with each choice are needed. The sentiment and motto behind the venture must also be clear in one's mind: For example, NGO versus private MHE, which would then reflect the legal stance, registration process to be taken, and set societal expectations from the establishment.

WHAT ARE THE PREREQUISITES FOR ESTABLISHING A MENTAL HEALTH ESTABLISHMENT IN INDIA?

The very beginning of all endeavors would involve premeditation and extensive planning. These include planning about:

Infrastructure

Decisions about converting an existent personal property into the establishment or renting the property would have to be made based on available resources. Infrastructure specific to a psychiatric setup, with adequate space for consulting rooms (ensuring privacy for the doctors and allied staff), examination rooms, provision for minor operation theater for modified electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)/space for biofeedback machines/repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) machines/transcranial direct current stimulation machines. Striving for an eco-friendly framework with a solar panel for generating electricity/heating water would be ideal. Provisions for, solid waste management and appropriate treatment of sewage should be present.

Staff recruitment

Recruitment of staff, both medical and nonmedical, ought to be done by a human resources team in association with the management and head of the establishment/psychiatrist in charge. Protocol for recruitment, qualifications, employee duties in individual capacities, duty hours, leaves and benefits, notice period, and resignation procedure have to be delineated at the time of recruitment.

Mental health facilities

Ideally, the MHP should begin with outpatient (OP) services and accumulate sufficient experience and patients, before embarking on initiating the inpatient (IP) MHE. This would ensure adequate OP and IP occupancy and better administrative sustainability.

Acute and outpatient care mental health establishment

It encompasses mental health services which would cater to the OPs, emergency care (facilities for observation and treatment of emergency cases for a period of ≤72 h).[14] Staff requirements should include a qualified psychiatrist and ideally allied MHP's. Functioning of staff should be such that at any given time (all 24 h) at least one doctor, one nurse, and one ward assistant are available. Infrastructure requirements for OP setting are, ideally, separate, and organized consultation rooms/cubicles with facilities for physical examination. Ready access to emergency services must be recommended. Waiting space with seating arrangements, a board room, reception, inquiry, and registration counters along with drinking water and toilet facilities should be available. Display the Registration certificate/licenses at the reception area, along with costs of treatment, as per the private establishment act.

Inpatient care

Ideal in-patient mental health facility should include varied living accommodation such as single-bedded rooms/double-bedded rooms/family accommodation. Long dormitory wards are best avoided. For safety concerns, do not house more than 20 patients in a dormitory. The facility should be safe, well ventilated and well lit at all times with easy accessibility. Separate accommodation for males and females, with a separate cot for the patient and the attendant is necessary. The overall design of doors/windows/fixtures/furniture should ensure patient safety. A furnished nursing station, examination room, and interview room are advised. Adequate bathing and toilet provisions are needed. Emphasis on safety with adequate supervision, installing surveillance systems in needed areas but keeping in mind patients, “need for privacy and dignity is the key.” All MHE's with more than 100 beds must have dedicated ambulance service.

High-dependency unit

Supported facilities may include a high-dependency unit (HDU) to tackle violence/deliberate self-harm/catatonia/medical comorbidities. An exclusive HDU would need suction apparatus, oxygen supply, and crash cart with lifesaving drugs. Patient care involving daily in-person Clinician-patient interaction/therapeutic intervention is essential. Clinical notes of these interactions must be maintained. Interventions should be clearly explained to the patient and family. Recovery, adverse situations, and compliance must be supervised and documented.

Specialty services

MHE's catering to specialty services would require specific provisions. Deaddiction services demand adequate staffing, judicious use of restraints, precautions to prevent violence/deliberate self-harm (DSH), and the management of drug-seeking behavior/craving. Other facilities for deaddiction centers include HDU and continuous ambulance services. Initiation of Child-Mother Unit to care for ill mothers with infants in the perinatal, intrapartum, or postpartum stage, with trained psychiatrists, adequate staffing, with facilities to keep the infant with mother would form the ideal Women's mental health service. Child and adolescent mental health centers require specialist psychiatrists, psychologists, occupational therapists, behavior therapists, speech therapists, trained nursing staff, assessment, and therapy tools. Infrastructure involving spacious, well lit, and ventilated interview setting/chambers suited to children are necessary, including a play area/sand pit. In-patient facilities that provide for parents to reside with the child patient are needed. Geriatric services focus on prevention (control of diabetes, hypertension, etc.), early identification, treatment, and rehabilitation. In addition to the regular psychiatric in-patient facilities, centers would require specialist staff and fellow medical specialists who can address physical comorbidities, physiotherapists, and support groups for caregivers. Brain modulation services in the form of modified ECT form part of most MHE settings. In addition, noninvasive modalities such as biofeedback, rTMS, and transcranial direct current stimulation should ideally be offered in conditions where these have been found effective. This would necessitate consideration into finances for the procurement of the devices, infrastructure to house the machines, and adequately trained MHP and staff. Nonpharmacological intervention offered as a standalone treatment or adjunctive treatment would provide a wholistic approach in psychiatric patient care. Qualified psychologists and psychiatrists with competence in psychodynamic psychotherapy, cognitive behavior therapy, mindfulness-based cognitive behavior therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, marital and family therapy, etc., would be ideal. Expansion of MHE services to include peripheral centers with the assistance of tele-psychiatry would be a way to serve the under-treated areas. Preventive and Promotive Mental Health, though not usually seen as part of the services, becomes important due to the minimal public awareness regarding mental health and stigma associated with psychiatric illness. The promotion of mental health should, on a priority, begin in schools through the life skills education program. Indian practices that are promotive of mental health (e.g., meditation, yoga, prayer, and social support in crisis situations) should be identified and encouraged. Rehabilitation Services are essential in MHE's, especially, those having long-term patients and bed-strength more than 50. Rehabilitation services include convalescent centers MHE categorized as (i) Daycare center (ii) Vocational training center (iii) Sheltered workshop (iv) Quarter way home (Hostel) (v) Residential halfway home (vi) Long stay home (vii) Community living centers for people with mental illnesses (PWMI).[15] Finally, complementary services such as Yoga and alternative therapies can be part of the special services offered.

Pharmacy

Addition of an in-hospital retail pharmacy can be instrumental in better patient care and generation of a new source of revenue for the MHE and in improving patient outcomes in terms of fewer medication errors, thereby reducing re-admissions. During discharge, it would ensure better medication compliance with a more accurate regimen being an in house service. Specialty pharmacy services providing for those, who require high-cost medications or other products that are not normally stocked in retail pharmacies would improve the quality of patient care.

Collaboration with other specialties and agencies/company/authority

Having professional partners from other medical specialties brings its own benefits, with a group practice being the protocol as against individual practice. Liaison with NGO's for collaboration in rehabilitation, media, police, the pharmaceutical industry, women and child welfare services, Medical council and fellow professionals will be both fruitful and necessary.

Medical record and digital data informatics

An equipped office for adequate medical record documentation is another necessity. Maintenance of records of the outpatient department (OPD) and IP, from the date of the first consultation, till a period of at least 3 years from the last date of consultation, is needed. If any request is made for medical records either by the patient or nominated representative (NR) (if the patient is incapacitated) or the court authorities, the same should be duly acknowledged and documents issued within 2 weeks.[14] A registered MHP should maintain a register of medical certificates giving full details of certificates issued, including identification marks or unique identification number or hospital number of the patient and a copy of the certificate ought to be maintained for hospital records. Efforts should be made to computerize medical records for easy retrieval. Further, registers to be maintained include OP attendance register, in-patient admissions register, census register, treatment adverse effect monitoring record, certificate register, medico-legal register, escape register, restraint register, and mortality register.

Place of institutional policies

The MHCA[14] has not made provisions for institutional policies, but it advocates to make the MHE rules and regulations with respect to patient care, treatment, and discharge. Institutional policy can include timings of admission and discharge, patient visits timing and protocol, dietary protocol, restriction of smoking/alcohol use in the premises, restriction of phone usage in sensitive areas like HDU, or any protocols necessary for safety. Policies which do not impinge or violate patient rights and are in keeping with the MHCA and constitutional law can be put in place.

Licensing

The Clinical Establishment Act 2018 is operative in a number of states for registration and regulation of all modalities of medical facilities and applies to therapeutic as well as diagnostic clinics inclusive of single-doctor clinics, the only exception being hospitals of the armed force.[16] The Clinical Establishment Act mandates medical establishments with private management to procure a trade license on an annual basis with a fee of Rs. 2000 to Rs. 50,000 (as categorized on the size and infrastructure of the establishment).[16,17] In addition, they have to pay for, a pollution control board license, fire department no objection certificate, and no objection certificate from adjoining property owners as mandatory. Miscellaneous licenses include pharmacy license, schedule X license under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act 1945 (amended)[18] which has a class of drugs such as methamphetamine and methylphenidate which cannot be sold without the prescription from a qualified doctor, and schedule H license containing 536 drugs that include many psychotropics. Possession and sale of iopiods is controlled by the Narcotics Drugs, and Psychotropic Substances Act amended in 2014,[19] wherein a class of narcotics labeled essential narcotics drugs (ENDs) were created with morphine, fentanyl, methadone, oxycodone, codeine, and hydrocodone, and are under the control of a single agency, namely the State drug controller. The State Drug Controller is responsible for the stocking and dispensing of END's and also approval of recognized medical institutions for the same. Institutions are obliged to maintain stock documentation and furnish annual statistics to the controlling body. The in-charge of the MHE needs to apply to the respective State Pollution Control Board in respect of states, or Pollution Control Committees in respect of Union Territories, for renewal of authorization, for the activities being carried out in the handling of Biomedical Waste Management by the MHE. Furthermore, lift license, permission for the use and maintenance of generator, canteen license, Employees’ State Insurance if more than 10 employees are there, and PF registration if employing >10/20 depending on the state, form the other necessary procedures.

Accreditation

National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and healthcare providers (NABH) accreditation[20] brings with it certain quality assurances that even MHE's can benefit from. It will ensure the standardization of healthcare in the hospital with easier functioning of systems. NABH guidelines include 10 chapters, namely the assessment of the patient, continuation of care, medication management, safety, hospital infection control, continued quality improvement, the responsibility of the management, etc.[20,21] Although NABH does not include specific guidelines for psychiatric practice, it does lay down guidelines for the documentation of procedures, the use of physical and chemical restraints, the use of psychotropic's and narcotics and the safety of the patient and protocol for falls. Furthermore, Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) can be tailor-made, such as SOP for violent/aggressive patients, suicide alert SOP, ECT SOP, biofeedback SOP, etc., as per the departmental policy, with an additional consent form as per need. NABH accreditation may pave the way to become an empanelled hospital for insurance.

Indemnity insurance for professionals and establishments

In India, medical practice has been brought under the Consumer Protection Act. An alleged deficiency in duty results in alleged medical negligence. The consumer can claim compensation for untoward medical consequence. Hence, indemnity coverage for psychiatrists becomes mandatory. Ensuring adequate coverage and the possible need for more than one indemnity insurance, with sufficient legal coverage is to be considered.[22]

Insurance for psychiatric care

Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India, in keeping with the spirit of section 21 (4) MHCA, requires insurance companies to make provisions for mental health insurance on par with physical illnesses.[23] However, the complexity of this issue remains in the underwriting of the policy as well as pricing issues, with exclusions from insurance cover which occur even for physical illnesses. We are yet to see insurance companies making provisions for mental healthcare.

Finance

Financial aspects, in the form of fund mobilization, loans, EMI's or wholesome investment and the use of a like-minded cohesive working group need deliberation.

MENTAL HEALTH ESTABLISHMENT AND MENTAL HEALTHCARE ACT

Definition of the mental health establishment

As per the MHCA 2017, MHE refers to any health establishment, inclusive of alternative medicine institutions, which in whole or part, caters to the care of individuals with mental illness. The entity may be established, owned, controlled or maintained by the appropriate government, local authority, trust, whether private or public, corporation, cooperative society or organization wherein individuals with mental illness are admitted and kept in for care and treatment, either temporarily or otherwise.[14]

Minimum norm for mental health establishment

Currently, the Central Mental Health Authority or State Mental Health Authority (SMHA) is yet to function and set a minimum norm for MHEs. In an ideal scenario, categorization of MHEs into Acute Care MHE, Convalescence Center, Exclusive Speciality Center, with the minimum requirements specified for each category, was thought of as an outcome of consultatory meetings of MHP's for minimum norms. Elaborate minimum norms would curtail the development of mental healthcare in the areas of need wherein the workforce, and infrastructure, are lacking in the country. Hence, local conditions are to be kept in mind when considering minimum norms. SMHA can inspect the location, infrastructure, facilities, staff, and so on. Periodic and/or random suo motto checks about the conditions of safety may be done.[14]

Registration of mental health establishment under MHCA

Registration application of MHEs under subsection (1) of Section-65[14] can be made for Provisional or Permanent, or Renewal of, registration. Application and fee are drawn in favor of SMHA, fee range depending on the category of the establishment. The application must carry details of the medical officer or psychiatrist in charge, with qualification certificates, and details of facilities, and services available at the MHE, staffing pattern, and their qualifications.[14] It is mandated that all MHEs be registered under the MHCA 2017. In the case of MHEs previously registered under the Clinical Establishment Act 2010 of the state, it is mandated that the certificate is attached stating fulfillment of the minimum requirement. After that, the authority, after confirming said facts, will issue the registration under MHCA.[14] Nonfulfilment of the condition laid down in the Act may result in refusal to grant the registration, after giving the applicant a reasonable opportunity of being heard against the proposed refusal of registration. Similar provisions have been made for the renewal process of MHE. On receipt of the application, provisional registration to the MHE is given in 10 days for which no inquiry is mandated, and particulars of the MHE have to be made available online in digital and print form within 45 days by SMHA. The provisional registration remains valid for 12 months. The permanent registration mandates the presence of minimum required standards to be met based on the categorization of MHE. Application for permanent registration should be submitted in the same manner as explained above for provisional registration. The MHE will undergo due to inspection, and the process for permanent registration will normally be complete in 45 days and can last up to 6 months if any rectification of deficiencies is required from the MHE. However, the OP services have been kept out of the purview of MHE definition and may function without registration under the MHCA. Additional Licence needs to be applied for safety precautions if the MHE wishes to treat co-morbidities and medical emergencies with liaison services as the Private Medical Establishment Act has a wider umbrella for medical care. Collaboration with other agencies, namely Mental Health Authorities (MHA) for registration, legalities, policy formation; and Mental Health review Board (MHRB) for admissions in certain categories, discharges, auditing, and inspection may be needed.

Mandated facilities as per MHCA

The MHCA 2017[14] mandates the MHEs to display helpline numbers/contact numbers of MHRB and free legal aid clinics and grievances redressal systems for patients and caregivers.

Basic medical record and MHCA

The MHCA 2017 mandates that each MHE should maintain basic medical records pertaining to OP and IP patients. The minimum medical record to be documented for MHE's as a hard copy form has been put forth in central rules. Record of only that information reported by the patients that essential for admission, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation should be documented. Recording of all the information provided is not mandatory; however, recording information that the professional deems fit to be incorporated, with ancillary information as per their training or need of the law, is acceptable. Furthermore, regulations about keeping a detailed record about restraint measures and their monthly reporting to SMHA are present.[14]

Auditing and inspection

As per section 67 of the MHCA, the state authority shall conduct an audit of all registered MHEs every 3 years to ensure that such MHE complies with the requirements of minimum standards for registration as an MHE. The authority may then raise a notice of cancellation of registration if minimum standards are found to be remiss, the persons in charge of the MHE are found to be convicted of an offense under the act, the MHE violates the right of any person under its care, or the SMHA has been instructed by the MHRB to do so. The authority shall, on cancellation of the registration, immediately restrain the MHE from carrying on its operations if there is an imminent danger to the health and safety of the persons admitted there.[14] On receipt of a complaint with respect to nonadherence of minimum standards specified by the Act or contravention of any provision thereof, the authority can order an inspection or inquiry of any MHE. Report of inquiry will be made with an order that the MHE make necessary changes within a specific period. Noncompliance under subsection (3), may lead to cancellation of the registration of the MHE. Operating an MHE without registration can bring about authorized search of the premises of the MHE for defaulting. Appeal to the High Court is permitted in case the MHE has any grievance against the authority pertaining to registration.[14]

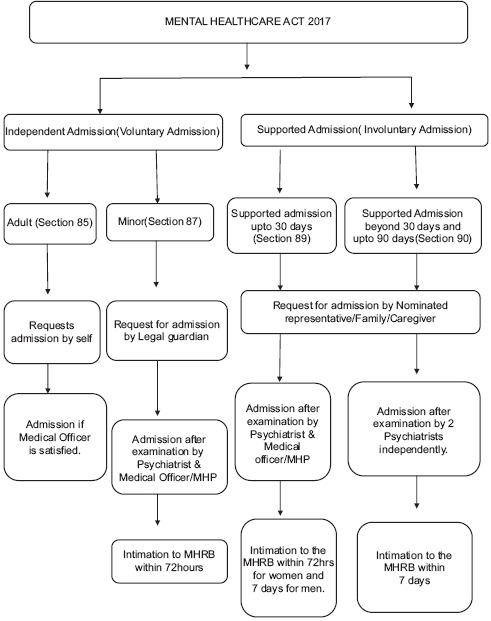

Provisions from admissions to discharge

As per the MHCA, a presenting patient needs a detailed evaluation for possible provisional psychiatric diagnosis and a suitable management plan. Available treatment and options of care and its benefits and risks have to be discussed with the clients at length, and suitable individualized care plan should be suggested. If the patient is accompanied by family members or representatives, on consent of the patient, they can be updated on the care plan. The severity of symptoms dictates the need for OP or IP care. If the medical officer feels admission to be necessary, the patient can be admitted as an independent admission as per section 86 MHCA[14] where he has the ability/capacity to decide/make the treatment-related decisions and stay in MHE as long as he desires. The patient will participate in the detailed informed consent process, choose treatment options suggested as per acceptable guidelines and be admitted on suitable applications for admission as specified in central rules. The treatment in the care plan is administered as per the wishes/desires of the client and after obtaining suitable/additional consents for any neOn completion of the treatment, the patient can request for discharge on suitable forms as per central rules, and discharge has to be made within 24 h.

If in the initial assessments, which include capacity assessments, the treating team finds that the PWMI needs further care, and the client is unwilling, the MHE has to check if the client fulfills the requirements of supported admission under section 89.[14] The NR of the client has the onus to provide a copy of the advance directive (AD), if any, that has been registered at the MHRB.[21] On receipt of the application, two independent assessments by psychiatrists and a Medical officer/another MHP is mandated, and subsequently, the patient can be admitted as a supported admission to the MHE, if it is the only available least restrictive option, for up to 30 days. The local MHRB has to be intimated of such admissions within the specified time frame for reviews and approvals (72 h for women and children, 7 days for men). The MHRB will be the appropriate authority to inspect, approve/reject admissions under section 89, to make any alterations to the AD, and to authorize any treatment that is not in accordance with the AD. For admissions under section 89, all the subsequent treatment to be given to the patients has to be in accordance with their valid AD, after obtaining suitable consents, forms/applications from the NR. Treatment and further care in accordance with suitable, acceptable guidelines can be planned in discussions with the NR and monitored daily. Further treatment and procedures planned (like rTMS, m ECTs, etc.) should be with additional consents from the NR,[24] capacity assessments have to be done weekly and the PWMI, on gaining capacity, should be moved to Section 86, after informing the change in admission status to the NR and patient and the rules of the relevant section shall prevail thereupon.

Contrarily, if the patient needs continued care in MHE and still lacks capacity on assessment, the treating team needs to ascertain the applicability of Section 90 provisions.[14] Then obtain suitable forms, make assessments by two independent psychiatrists and then admit PWMI under section 90 for up to 60 days. MHRB has to be intimated of such admissions within the time frame suggested for approvals and also for further extensions in an IP stay, up to 180 days in total, with approvals from MHRB.[14] Discharge planning has to be done as a mandated procedure for all admissions made at the MHE. Independent admissions do not require the consent of the NR. However, supported admissions and admission of minors require consent and involvement of NR, both for admission and for planning further continued care and rehabilitation of the patient.[14]

Noncompliance with the provisions of MHCA

Failure to comply with any provisions of MHCA/violating any of the sections under the act/any complaints to MHRB with subsequent proof of guilt will incur heavy penalties ranging from Rs. 10,000 to 50,000/- and again up to Rs. 5 Lac depending on the nature of the offense or repeat of the offense (Section 107). It can also lead to imprisonment ranging from 6 months to 2 years. Any registered MHP offering services in an unregistered MHE is also liable to be punished with a fine of up to 25,000/-. We are duty-bound to verify whether an MHE is registered or not and offer our services solely in registered MHEs, except for services offered in OPD setting/treatment offered under Section 94.[14] Ignorance of the provisions of the law will not stand as a defense [Flowchart 1].

Flowchart 1.

Admission process as per MHCA 2017 (Courtesy and permission from: Dr. Suresh Bada Math). MHRB: Mental Health Review Board

CHALLENGES AND REWARDS IN THE NEW GROUNDS OF PSYCHIATRIC PRACTICE UNDER THE MHCA 2017

The functioning of an MHE has its unique challenges like compliance issues, with-holding of consent, possible risks of violence, suicide attempts, sudden deaths requiring a declaration, absconding of patients, etc. Similarly, handling difficult patients who disrupt ward functioning, intrude in fellow patients’ care, show sexual disinhibition, or struggle with craving for substances,-monitoring boundaries between staff and patients prove demanding. In addition, NRs or the patient's family members themselves having high expressed emotions/complete un-involvement, or hostility toward the treating team; making unreasonable demands or imposing their agendas on the team; lacking an understanding of mishaps that happen creating difficult situations in transactions; or having a syndromal or subthreshold psychiatric condition themselves can become increasingly trying. Ideally, all treatment conditions and special situations should have an SOP, thereby ensuring standardization of care across the treating team in an MHE. From a clinical perspective, the possibility of relapses in the illness as well as treatment resistance remains a challenge, necessitating the need for more radical treatment, though ideally within the realm of well-founded globally accepted guidelines. Over time, the roles and responsibilities of a psychiatrist managing an MHE may get diluted, with the constant requirement in juggling clinical and administrative roles, and it would necessitate summoning the art of time management to prevent stress and burnout among themselves as well as their colleagues in the MHE. Academic, clinical and legal peer group discussions, with guidance being sought from professional organizations such as Indian Psychiatric Society and Indian Medical Association, would definitely help in managing an MHE.

MHCA gives due credence to the patient's right to confidentiality. All professionals providing treatment to PWMI are obligated to keep all reports acquired during assessment or treatment confidential, with the following exceptions; sharing of information with the NR when patient is incapacitated, with allied professionals/MHP as part of the treatment process or discussion about further care, on the order of appropriate authority/high court/supreme court and as a means of safeguarding others against possible violence/harm. Only the specific information associated with risks of harm/threat to life is to be released. Inaddition, release of any picture or information of a patient to the media by MHE without the consent of the patient is strictly prohibited. This applies to all information stored as an electronic or digital format in real or virtual space.[14]

Establishing and running an MHE can serve the felt needs in the community and help reduce the treatment gap. MHCA has mandated care with an international level of quality to the PWMI, with obligations on the part of Government to provide this right to mental health. Several mandated procedures under MHCA can be an additional source of revenue to the MHE. Documentations, spending quality time, need for the second certifications, and periodic reassessments may lead to a revision of charges and consultation fees. House visit and/ambulance services now have legal backing under section 94 and will be additional obligatory services from the MHE. Furthermore, initiating an MHE can provide the professional with a way to explore new treatment options and innovative methods of psychiatric care more in tune with the local population. Physician's dual roles of professional and healer’ can be fulfilled with ensuring quality mental healthcare in their establishment and being part of promotive and preventive mental health services to the community.

CONCLUSION

Founding an MHE may appear a herculean endeavor, but keeping in mind the growing burden of mental health needs, this would help bridge the gap if more professionals attempt to walk this path. This endeavor would also prove to gratify for the professional in terms of conquering psychiatric challenges, furthering proficiency in varied skill-sets, and being part of the change in mental healthcare. Ensuring adequate steps such as meticulous documentation from the time of the first patient consultation, addressing consent issues, due diligence in the establishment registrations, classifying patients as independent/high support needs admission, and having SOPs for violence/DSH/suicide/escapes and falls is essential. Running an MHE requires adequate training of staff, addressing stress and burnout in staff, and liaisons with legal teams and/fellow medical professionals. Keeping in tune with MHCA will go a long way in the successful functioning of an MHE.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organisation. Mental Health Atlas. World Health Organisation. 2017. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/profiles-2017/en/#T .

- 2.Srinivas Murthy R. Mental Healthcare in India. Past, Present and Future. 2010. Jun, [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 19]. Available from: https://www.mhpolicy.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/mental-health-care-in-india-past-present-and-future-rs-murthy.doc .

- 3.National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16: Prevalence, Pattern and Outcomes. Bengaluru: NIMHANS; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/en/

- 5.Patel V, Xiao S, Chen H, Hanna F, Jotheeswaran AT, Luo D, et al. The magnitude of and health system responses to the mental health treatment gap in adults in India and China. Lancet. 2016;388:3074–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srinivasa Murthy R, Kaur R, Wig NN. Mentally ill in a rural community: Some initial experiences in case identification and management. Indian J Psychiatry. 1978;20:143–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parthasarathy R, Chandrashekar CR, Isaac MK, Prema TP. A profile of the follow up of the rural mentally ill. Indian J Psychiatry. 1981;23:139–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandrashekar CR, Isaac MK, Kapur RL, Sarathy RP. Management of priority mental disorders in the community. Indian J Psychiatry. 1981;23:174–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee S, Patel V, Chatterjee A, Weiss HA. Evaluation of a community-based rehabilitation model for chronic schizophrenia in rural India. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:57–62. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srinivasa Murthy R, Kishore Kumar KV, Chisholm D, Thomas T, Sekar K, Chandrashekari CR, et al. Community outreach for untreated schizophrenia in rural India: A follow-up study of symptoms, disability, family burden and costs. Psychol Med. 2005;35:341–51. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel V, Thara R, editors. New Delhi: Sage(India); 2003. Meeting Mental Health Needs in Developing Countries: NGO Innovations in India. [Google Scholar]

- 12. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 19]. Available from: https://www.who.int/features/2015/mental-healthcare-india/en/

- 13.Bagchi S. Rethinking India's psychiatric care, insight. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 19];Lancet. 2014 1:503–4. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00096-0. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/psychiatry . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017. Ministry of Law and Justice. New Delhi: 2017. Apr 7th, [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anthony W, Cohen M, Farkas M, Gagne C. Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Centre for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Trustees of Boston University. (2nd ed) 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Clinical Establishment (Registration and Regulations) Act, 2010. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karnataka Private Medical Establishments Act, 2018. Health and Family Welfare Secretariat. Bengaluru. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Drugs and Cosmetic Act 1945 and Drugs and Cosmetics Rules, 1945. Ch. 4. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 1945 [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (Amendment) Act' 2014 (16 of 2014) (w.e.f. 1-5-2014) doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Accreditation Standards Guidebook for Hospitals. National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers. (4th ed) 2015 Dec; [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao GP, Math SB, Raju MS, Saha G, Jagiwala M, Sagar R, et al. Mental health care bill, 2016: A boon or bane? Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58:244–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.192015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joga Rao SV. Medical negligence liability under the consumer protection act: A review of judicial perspective. Indian J Urol. 2009;25:361–71. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.56205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 19]. Available from: http://www.iradi.gov.in/

- 24.Neredumilli PK, Padma V, Radharani S. Mental healthcare act 2017: Review and upcoming issues. Arch Ment Health. 2018;19:9–14. [Google Scholar]