Risk variants in the APOL1 gene on chromosome 22, which were first discovered in African Americans, confer a substantially increased risk of kidney disease, early-onset hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, although disease risk is modified by other genetic factors and by environmental factors.1 This is an important discovery for genomic medicine and has improved our understanding of disparities among ethnic groups.2 Efforts are under way to incorporate APOL1 testing in routine clinical settings, and APOL1 is under consideration as a therapeutic target for kidney disease.3 The APOL1 risk variants rose to high frequency in Western Africa in response to trypanosomal infection,4 and most studies of APOL1 have involved populations of persons who self-report as African or African American. However, other populations who also share recent ancestry from Africa, such as Hispanic populations, may be at greater risk than expected for APOL1-driven disease.

These persons may not undergo testing; however, they may still be at high risk because of the presence of APOL1 risk variants.5 Thus, it is important to understand more fully the global distribution of these variants on the basis of country of origin and genetic ancestry rather than self-reported race or ethnic group.

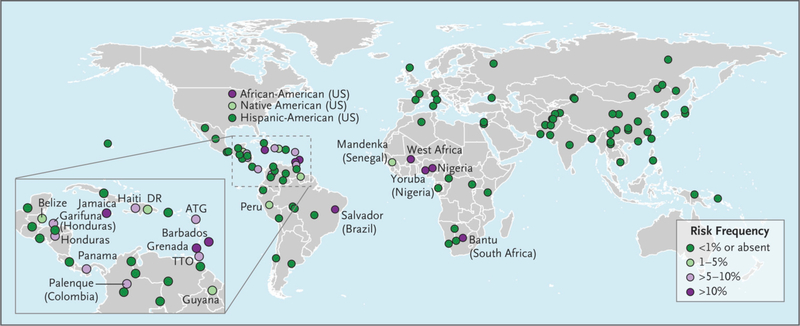

We used linked genetic and demographic data from 111 populations in two large studies, the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology Study (https://pagestudy.org) and the Consortium on Asthma among African ancestry Populations in the Americas (www.caapa-project.org), to determine the global frequencies of APOL1 risk variants (see the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org). We inferred risk-allele status using the two G1 alleles (rs60910145 and rs73885319) and the proxy single-nucleotide polymorphism commonly typed for G2 (rs12106505). The frequencies of the recessive risk genotypes according to country and population of origin are shown in Figure 1 and are available online (http://APOL1.org). Consistent with previous work, 1,2 we found elevated frequencies of the APOL1 haplotype in African-American, sub-Saharan African, and Western African populations (11 to 32%). However, we also found other populations with elevated frequencies, including Jamaican, Barbadian, Grenadian, and Brazilian from Salvador (>10 to 22%); Trinidadian, Panamanian, Honduran, Haitian, Garifunan, and Palenque (>5 to 10%); and Guyanese, Dominican, Peruvian, Belizean, and Native American (1 to 5%). These findings show that the risk alleles are present in populations of persons who are not typically screened, which may result in the underdiagnosis and undertreatment of kidney disease and related coexisting conditions.

Figure 1.

APOL1 G1/G2 risk in 111 global populations.

We inferred risk-allele status using the two G1 alleles (rs60910145 and rs73885319) and the proxy single-nucleotide polymorphism commonly typed for G2 (rs12106505) on APOL1. Only populations with a risk allele status of 1% or higher are labeled (with the exception of Hispanic Americans). Where possible, precise geographic region or ethnic group labels are used on the map; otherwise, populations are labeled according to country or general geographic region. A more detailed map is available at http://APOL1.org. ATG denotes Antigua, DR Dominican Republic, and TTO Trinidad and Tobago.

In conclusion, APOL1 risk variants exist at appreciable frequencies among many populations of persons in the Americas who share Western African genetic ancestry but who may not self-identify as African or African American. This finding underscores the importance of disseminating diverse variant frequencies in genetic studies and of screening a broader group of patients beyond those who have traditionally been identified as being of African descent. Such persons may also be at significant risk for kidney disease, early-onset hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, which is important in the consideration of genetic testing, population management, clinical trials, and health policy decisions.

Supplementary Material

References:

- 1.Parsa A, Kao WHL, Xie D, et al. APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2013;369(23):2183–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nadkarni GN, Galarneau G, Ellis SB, et al. Apolipoprotein L1 Variants and Blood Pressure Traits in African Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69(12):1564–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ito K, Bick AG, Flannick J, et al. Increased burden of cardiovascular disease in carriers of APOL1 genetic variants. Circ Res 2014;114(5):845–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kruzel-Davila E, Wasser WG, Aviram S, Skorecki K. APOL1 nephropathy: from gene to mechanisms of kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc - Eur Ren Assoc 2015; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Horowitz CR, Abul-Husn NS, Ellis S, et al. Determining the effects and challenges of incorporating genetic testing into primary care management of hypertensive patients with African ancestry. Contemp Clin Trials 2016;47:101–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heymann J, Winkler CA, Hoek M, Susztak K, Kopp JB. Therapeutics for APOL1 nephropathies: putting out the fire in the podocyte. Nephrol Dial Transplant Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc - Eur Ren Assoc 2017; 32(suppl_1):i65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behar DM, Rosset S, TzurS, et al. African ancestry allelic variation at the MYH9 gene contributes to increased susceptibility to non-diabetic end-stage kidney disease in Hispanic Americans. Hum Mol Genet 2010; 19(9):1816–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.