Abstract

Time until all-cause treatment discontinuation was the primary outcome of the CATIE trial. We discuss the advantages and disadvantages of this outcome, and evaluate its association with clinical correlates through graphical response profiles. We investigate the characteristics of patients who discontinued for patient decision, including a reclassification of patient decision into other reasons. All-cause discontinuation is compared to a related outcome, time until treatment failure. Patients who discontinued had lower quality of life scores than other patients. Patients discontinuing for lack of efficacy had worsened efficacy scores compared with an improvement for other patients. Those who discontinued for patient decision had lower compliance. Blinded reclassification of discontinuation for patient decision identified 5% of cases as lack of efficacy and 21% as intolerable side effects. Reclassified patients participated in the next study phase at a higher rate than those remaining as patient decision (67% vs. 10%). Treatment group differences for time to discontinuation due to patient decision were attenuated after censoring the reclassified patients, but were still suggestive. Treatment comparisons for time to treatment failure were consistent with all cause discontinuation, although somewhat smaller. All-cause discontinuation is recommended as a simple and comprehensive outcome for pharmaceutical Phase II-IV clinical trials.

Keywords: drop-out, informative missing data, graphical response profiles, lost to follow-up, treatment failure

1. INTRODUCTION

The CATIE (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness) schizophrenia study was a multi-phase NIH-funded clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of five antipsychotic medications (Lieberman, 2005). In the first study phase, 1432 patients were randomized and received double-blind treatment with one of five antipsychotic medications. Patients were followed for up to 18 months. If the Phase 1 treatment was found to be unsatisfactory for any reason, subjects discontinued Phase 1 and could be re-randomized to a new double-blind treatment in a subsequent phase. Over a quarter of the subjects discontinued Phase 1 by three months, and 74% (n= 1061) discontinued by 18 months: 24% (n=340) for lack of efficacy, 15% (n=213) for intolerability, 30% (n=428) due to patient decision, and 5% (n=80) for administrative reasons. Patient decision included all cases where the subject chose to stop treatment against the investigator’s recommendation such as loss to follow-up, withdrawal of consent, lack of compliance, and may also have reflected latent dissatisfaction with efficacy or side effects that was not clearly expressed. Low compliance itself was not a separate reason for treatment discontinuation. Administrative reasons included incarceration, moving from the geographic area, or protocol violations. Of the 1061 who discontinued, 609 (57%) continued the study in a subsequent treatment phase. The primary outcome was time until all-cause Phase 1 discontinuation, defined as stopping participation in Phase 1 for any reason, including intolerable side effects, lack of efficacy, patient decision, or administrative reasons. Discontinuation did not necessarily mean stopping the study since patients were encouraged to enter a subsequent phase of the trial in which they would be re-randomized to different treatment options. Overall treatment group differences were found for time until all-cause Phase 1 discontinuation, as well as for the secondary outcomes of time to discontinuation due to lack of efficacy and due to patient decision. One of the five treatment groups showed superiority over several but not all of the others (Lieberman, 2005).

In this paper, we discuss the advantages of all-cause treatment discontinuation as the primary effectiveness outcome. We further examine this outcome through its association with relevant clinical correlates using graphical response profile cohort graphs, and through a detailed evaluation of discontinuation due to patient decision. We perform a post-hoc reclassification of patient decision into other reasons for discontinuation, and we compare all-cause discontinuation to a related outcome, time until treatment failure.

2. DISCUSSION OF TIME TO TREATMENT DISCONTINUATION

Prior to study unblinding, the primary analyses for CATIE were specified in a statistical analysis plan (Davis, 2003). The primary outcome domain was specified as overall treatment effectiveness in Phase 1. Within this domain, we chose all-cause Phase 1 treatment discontinuation as the single primary outcome. Treatment discontinuation was defined as withdrawal from Phase 1 randomized treatment for any reason, including intolerable side effects, lack of efficacy, patient decision, or administrative reasons. The analysis population included all 1432 patients who took at least one dose of double-blind medication. Kaplan Meier survival estimates were produced for time to treatment discontinuation. Subjects who completed 18 months in Phase 1 (n= 371) were censored in the analysis. Hypothesis tests for assessing treatment differences were based on proportional hazards regression models (Cox 1972).

Applicable descriptive statistics include median time on treatment and probability of staying on treatment for a specified duration. Treatment group comparisons were based on hazard ratios, which can sometimes be complex for general audiences to interpret. The outcome was further simplified for descriptive purposes into the proportion of subjects who discontinued Phase 1 from each treatment group.

Time until all-cause discontinuation was an attractive primary effectiveness measure for the CATIE investigators because of its simplicity and comprehensiveness. A patient’s response to treatment can often be a complex combination of efficacy and tolerability, which can either be affected by lack of compliance and/or be a cause of lack of compliance. The efficacy, tolerability, and compliance components of effectiveness can be difficult to independently quantify, especially for schizophrenia. By including all reasons, time to all-cause discontinuation encompassed lack of efficacy, intolerable side effects, any combination of the two, patient decision, plus any other reason that led to substantial dissatisfaction with the medication, without having to specifically identify these reasons. In addition, it can be easily understood by clinicians and health care administrators and policy makers, without, for instance, needing to know details of specific scoring instruments. Due to its generalizability and ease of data collection, it can be incorporated into the analysis of many Phase II—IV clinical trials.

Time to discontinuation would not be an appropriate effectiveness outcome for acute illnesses that can be completely healed within a short time period, or intermittent illnesses with symptoms that come and go. In these cases, subjects who discontinued the drug because it was no longer required would need to be carefully separated from those for whom the drug was ineffective or intolerable. This scenario is not applicable to schizophrenia, however, because of its long-term course and need for long-term treatment. Patients with schizophrenia commonly stop taking their medication due to adverse effects, lack of treatment response, or failure to perceive a need for treatment. For schizophrenia, staying on a treatment for a longer time can in itself be considered a success in as much as it may lead to greater symptom reductions, fewer hospitalizations, or improved quality of life. Similarly, time until all-cause treatment discontinuation could be an appealing effectiveness outcome for other long-term incurable illnesses such as AIDS and Hepatitis C.

Duration on treatment, however, is not a direct measure of the efficacy or safety of a treatment, since longer treatment does not necessarily correspond with positive outcomes, and some side effects can take a long time to develop. For this reason, it is not an appropriate primary measure to confirm efficacy or safety of new treatments. In the effectiveness setting, it is of interest to supplement all-cause discontinuation with an evaluation of individual clinical outcomes of efficacy, safety, quality of life and compliance for comparisons of specific treatment outcomes.

Perhaps one of the most striking benefits of time until all-cause treatment discontinuation is the fact that the outcome is defined by whether a subject discontinued. This is a benefit compared to many clinical outcomes which are missing, biased, or hard to interpret when a subject discontinues from a trial. Most clinical outcome data in CATIE were collected in the form of repeated measurements over time, such as the efficacy and side effect scales, quality of life, and laboratory assessments. When a subject discontinues a clinical trial, outcome data left missing for this person is generally not missing completely at random. For example, a subject who discontinued for lack of efficacy would likely have demonstrated high PANSS scores had they continued.

Standard analysis methods for outcomes measured at scheduled intervals are negatively impacted by non-ignorable missing data, and the impact increases with the amount of data that is missing. In CATIE, over a quarter of subjects had discontinued by 3 months, and 74% discontinued by 18 months. Mixed models for repeated measures, multiple imputation, analysis at fixed time points, last observation carried forward (LOCF) analysis, and adjustment for duration of exposure are all methods of addressing the missing data caused by early clinical trial discontinuation, although none adequately addresses the fact that a very large amount of data was simply not present. Mixed models are used frequently, and are increasingly used as primary analyses in pharmaceutical regulatory submissions (Ohidul 2009). However, when a substantial percentage of patients discontinue early, the assumptions required for the mixed model become more uncertain. Correctly specifying the covariance structure between the repeated measurements becomes more challenging as the amount of missing data increases. One cutting edge methodology for analyzing clinical outcomes measured at multiple visits is based on co-modeling of the repeated measures and the time to discontinuation (Saville 2010, Wulfsohn 1997, Hogan 1997, Henderson 2000, Gueorguieva 2010). This method has our primary outcome, time to all-cause discontinuation, as one of its fundamental components, and was evaluated for the CATIE efficacy PANSS data by Gueorguieva (2010).

Time to all-cause discontinuation has not often been used as a primary outcome in clinical trials. Its simplicity, comprehensiveness, and applicability under large amounts of missing data due to patient discontinuation make it an attractive primary outcome for effectiveness studies. For these same reasons, it is also an informative secondary outcome for most randomized Phase II-IV pharmaceutical clinical trials. To further characterize all-cause discontinuation, in this paper we evaluate its association with relevant clinical outcomes collected in the study.

3. METHODS

3.1. Response Profiles of Clinical Correlates

One FDA recommendation to evaluate the impact of patient discontinuation on clinical outcomes is a graphical display of the mean of the outcome measure over time. Cohorts are defined either by time of discontinuation or by reason for discontinuation. A separate segmented line graph for each cohort is overlaid on one figure (Hung 2004). This provides a graphical display of the response profile, allowing a visual comparison of the cohorts similar in spirit to the approach of pattern mixture models (Little 1993). If the time of discontinuation or the reason for discontinuation had no relationship with the outcome, then all cohorts would have overlapping profiles (similar trajectories). The greater the difference between cohorts, the stronger the relationship between the clinical outcome and the patient discontinuation characteristic that defined the cohort. In a regulatory setting, the focus of such graphical response profiles would be to evaluate whether the treatment groups display different patterns, suggesting a different relationship between the clinical outcome and discontinuation by treatment group. Therefore in a regulatory setting, the treatment groups would form separate cohorts.

Use of graphical response profiles provides a way to evaluate the association of time to discontinuation with other clinical outcomes, by visually showing if those who discontinued for a specific reason had changes in relevant clinical outcomes at the time of the discontinuation. Since our purpose was to look at the outcome itself and not compare treatments, our evaluations combine all treatment groups together. With the large sample size in CATIE, there were enough discontinuations to define cohorts encompassing both time until discontinuation and a specific reason for discontinuation simultaneously. Most discontinuations occurred in the first six months, and so cohorts were created for patients who discontinued at each month between one and six. Starting at month seven, cohorts were defined by discontinuations occurring within 3-month intervals, for 7– 9, 10–12, 13–15, and 16–18 months. Many of the assessments were scheduled to be measured at the quarterly visits. When the sample size in a cohort was less than 20, the cohort was not evaluated and does not appear on graphs.

In addition to the cohort response profile graphs, it was also of descriptive interest to assess statistical differences between cohorts. Our interest was to compare the mean outcome at the last visit of a cohort versus the mean outcome of all other cohorts at that same visit, including patients who discontinued at that visit for some other reason, and those that continued to the next visit regardless of eventual time or reason for discontinuation. For example, for the cohort of patients who discontinued due to lack of efficacy at month 6, we compare the mean PANSS score at month 6 of this cohort versus the mean PANSS score at month 6 for all patients who either discontinued for some other reason at month 6, or discontinued at a later visit for any reason. A t-statistic comparing the means was used as a tool to describe the strength of the difference. Thinking back to the cohort response profile graph, we are comparing the last point on the graph for one cohort versus the average of all patients comprising the other data points on the graph at that same visit. In a series of t-statistics for each visit, each cohort of patients switches comparison groups at the visit in which they discontinue. The series of comparisons can be displayed via a plot of means together with 95% confidence intervals. This testing strategy compares clinical outcomes between those who discontinue and those who do not at the same time. Comparisons need to be made at the same time so that any effect of differing durations of exposure is taken into account. This is needed since most clinical outcomes change over time during a trial, and so comparisons between cohorts can only be made at consistent time points.

Using these two types of graphical displays, we evaluated if patients who discontinued Phase 1 were different from patients who continued to the next visit. For all-cause discontinuation, we expected that there would be differences between those who discontinued versus those who stayed in the trial for the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life (QOL) score (Heinrichs 1984), and the MOS SF-12 mental health score, which encompassed broad aspects of well-being. We expected no differences on the SF-12 physical score due to the nature of schizophrenia and the side effect profile of the treatments. For discontinuation due to lack of efficacy, we expected that there would be differences between those who discontinued for lack of efficacy and those who did not on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score, and the Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S). For patients who discontinued due to intolerability, there was no global intolerability measurement repeated across visits, so we could not graph a response profile. Instead we compared the percentage of patients who reported any moderate or severe adverse events for patients who discontinued due to intolerability versus all other patients using a chi-squared statistic. We postulated that subjects who discontinued for patient decision would have lower compliance at the discontinuation visit relative to all others who did not discontinue for patient decision at that visit.

3.2. Further Evaluation of Patient Decision

In order to further describe treatment group differences in all-cause discontinuation, secondary evaluations were planned a priori for three specific reasons for discontinuation: lack of efficacy, intolerability, and patient decision. Patient decision encompassed all reasons for Phase 1 discontinuation other than lack of efficacy, intolerability, or administrative reasons. Discontinuing for administrative reasons (n=80, 5%) such as incarceration, subject moving or protocol violations was included in all-cause discontinuation, but not analyzed as a secondary outcome. In these analyses (Lieberman 2005, McEvoy 2006, Stroup 2006, Stroup 2007), subjects who discontinued due to a reason other than the one of interest were considered censored at the time of discontinuation. The main CATIE results paper reported statistically significant treatment group differences in time to discontinuation for lack of efficacy and patient decision (Lieberman, 2005). One of the treatments, olanzapine, had numerically longer time to Phase 1 discontinuation for patient decision than the other four treatments, with significant (p< 0.01) pair-wise differences compared to quetiapine and risperidone.

Further exploration of the discontinuation for patient decision was warranted for a number of reasons. First, it was the largest reported reason for discontinuation. Second, due to its broad definition, evaluation of the level of overlap or potential miss-classification between patient decision and the other reasons for discontinuation was of interest. Could the differences between treatments be extracted from non-treatment related events such as withdrawal of consent? Third, further description of the characteristics of people who discontinued for patient decision was relevant. Patient discontinuation from pharmaceutical clinical trials causes a serious missing data problem for assessing efficacy and safety outcomes. With such a large sample size of patients who discontinued for patient decision, CATIE offered a unique opportunity to compare clinical characteristics for those who chose to discontinue versus those who did not.

If a patient’s decision to discontinue Phase 1 was completely unrelated to the treatment, and instead was uninformative drop-out, as might be expected for discontinuation for patient decision, then treatment group differences for time to discontinuation for patient decision would not be expected. Since significant treatment group differences were identified, there appeared to be some aspects of a patient’s satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the treatment that was not recognized by the site investigator and therefore not classified as lack of efficacy or intolerability. To investigate if we could separate the useful information for treatment group comparisons versus non-informative patient discontinuation, subjects who had discontinued for patient decision were re-classified based on a blinded review of comment fields.

If patient decision was selected as the primary reason for Phase 1 discontinuation, the case report form collected a free-text “specify” field to record a description explaining the patient’s decision to discontinue. In the first step of the blinded review, a psychiatrist (TSS) and a statistician (SMD) independently reviewed blinded text strings and classified them into new categories for lack of efficacy, intolerability, or remaining as patient’s decision. Those remaining as patient decision were further subdivided into poor compliance, lack of patient’s insight regarding the need for treatment, administrative reasons unrelated to the study such as incarceration or relocation, and withdrew consent with no specific reason given/otherwise unable to classify. When the psychiatrist’s and statistician’s classification fell into different categories, the blinded text strings were reviewed by a second psychiatrist (JAL) to determine the final reclassification.

With this re-classification, characteristics of the newly identified cases of lack of efficacy and intolerability and the remaining cases of patient decision were investigated. For evaluation of whether the remaining non-reclassified patients were informative for treatment group comparisons, an exploratory analysis repeated the original treatment group comparisons of time to discontinuation for patient decision using the reclassified definition.

3.3. All cause Discontinuation Contrasted with Treatment Failure

A similar outcome to all cause discontinuation is treatment failure, defined as discontinuation for lack of efficacy or intolerability. In the analysis of treatment failure, discontinuations for patient decision or administrative reasons are censored. This strategy assumes that all cases of patient decision or administrative reasons are completely non-informative (i.e., unrelated to the treatment assignment or the treatment failure outcome). If all such cases are indeed unrelated to treatment, then analysis of treatment failure might have better power than all-cause discontinuation, by excluding the noise caused by the non-informative cases. Yet compared to all-cause discontinuation, this potential gain in power could be offset by the loss of power from the reduced number of total events. On the other hand, although noise is introduced to all-cause discontinuation by non-informative drop-outs, no discontinuation event that is potentially informative for treatment group comparisons is excluded. Since the CATIE trial had many discontinuations for patient decision, we felt it would be informative to perform an analysis of time to treatment failure in comparison to all cause discontinuation. However, since the CATIE protocol-specified classification of patient decision was broad and specifically not designed to capture only those events that seemed to be non-informative for treatment comparisons, a definition of treatment failure that excluded all cases of patient decision would be inappropriate. As a rational alternative, we defined the reclassified discontinuations for lack of efficacy and intolerability as events, and censored the non-reclassified cases of patient decision along with patients originally identified as discontinuing for administrative reasons.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Response Profiles of Clinical Correlates

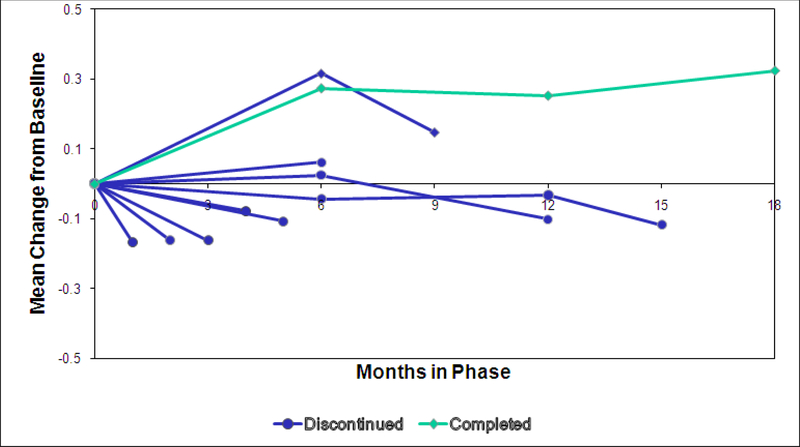

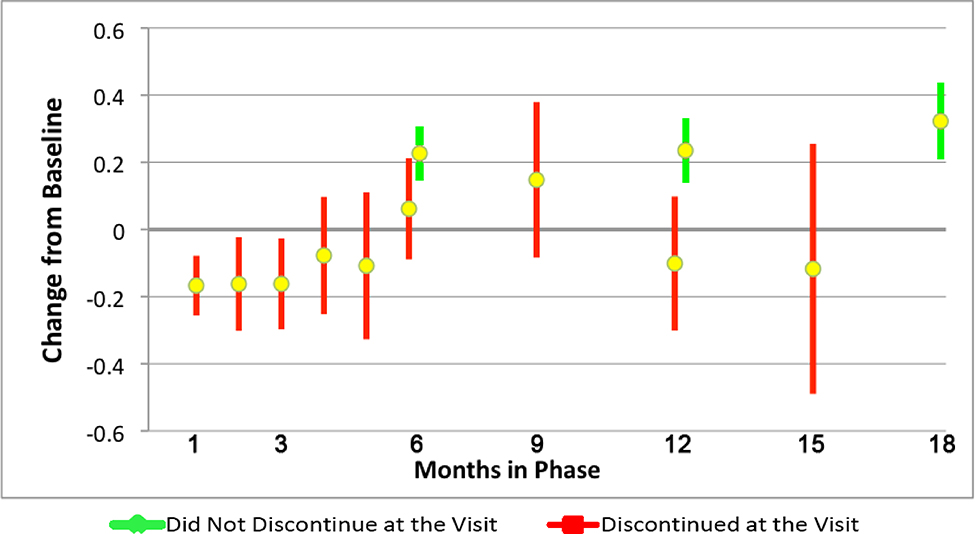

Figure 1 displays the QOL score change from baseline response profiles by cohorts defined by month of all-cause discontinuation. Patients who discontinued Phase 1 generally had lower QOL scores than Phase 1 month 18 completers, and had decreases rather than improvements in QOL in all but one cohort. QOL was measured at months 6, 12, 18, and early discontinuation, where feasible. Therefore, QOL scores for discontinuers could only be compared to patients who did not discontinue at the same visit at months 6 and 12. The means of patients discontinuing versus not discontinuing at each visit are shown in Figure 2. Discontinuers had a lower mean QOL score than all other patients at month 12 (0.10 decrease vs. 0.24 increase, mean difference = 0.34, 95% CI = [0.10, 0.57] p=0.005), with a trend at month 6 (mean difference= 0.17, 95% CI= [−0.02, 0.35], p=0.056). SF-12 Mental Functioning scores were measured at the same time points, and also showed differences at month 12 (mean difference = 3.1, 95% CI= [0.2, 5.9], p=0.037) and a trend at month 6 (mean difference= 2.0, 95% CI= [−0.3, 4.3], p=0.086). As expected, no difference was seen for SF-12 physical functioning (month 6 mean difference =1.4, p=0.15, month 12 mean difference = 0.08, p=0.95).

Figure 1. Quality of Life Score Mean Change from Baseline by Cohorts Based on Duration of Phase Participation.

QOL score is the mean of 21 items, and ranges from 0 (worst) to 6 (best). QOL was measured at months 6, 12, 18, and early phase discontinuation (as available).

Sample size of QOL by cohort based on last visit: month 1: n=168, month 2: n=109, month 3: n=107, month 4: n=62, month 5: n=46, month 6: n=108, months7– 9: n=75, months 10–12: n=76, months 13– 15: n=26, month 18 completers, n=363.

Figure 2. Quality of Life Score Mean Change from Baseline and 95% CIs by Discontinuation Status per Month.

Month 6: Mean difference = 0.17, 95% CI= [−0.02, 0.35], p=0.056.

Months 9–12: Mean difference = 0.34, 95% CI= [0.10, 0.57], p=0.005.

Sample sizes: Discontinued at the visit: month 1: n=168, month 2: n=109, month 3: n=107, month 4: n=62, month 5: n=46, month 6: n=108, months7– 9: n=75, months 10–12: n=76, months 13– 15: n=26, Did not discontinue at the visit: month 6: n=540, month 12: n=401,month 18 completers, n=363.

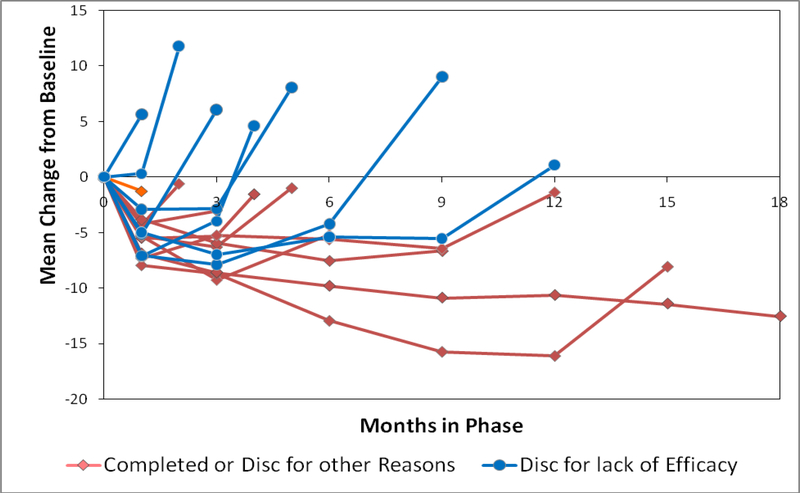

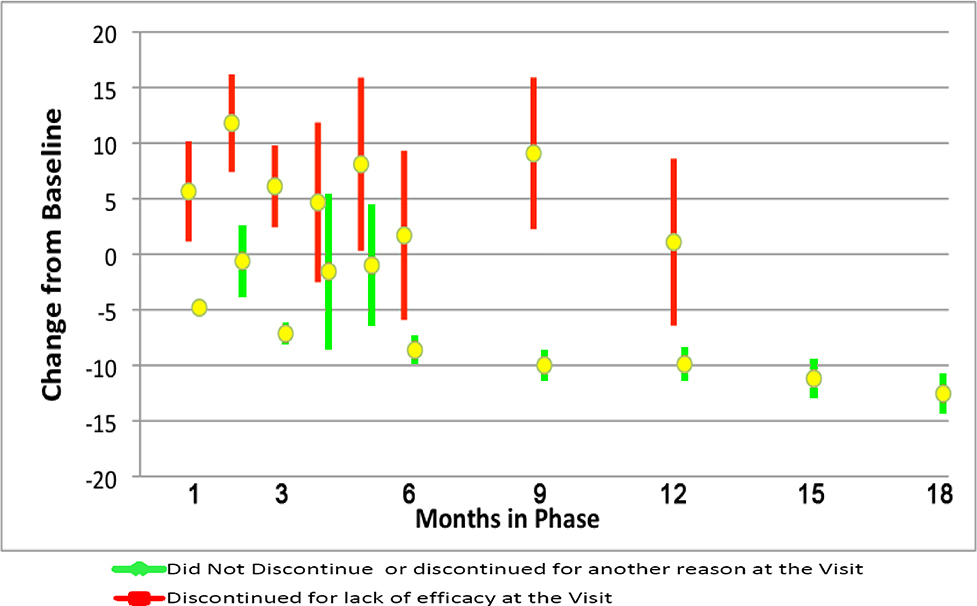

The PANSS response profile graphs by cohort based on time to discontinuation and reason of discontinuation (efficacy versus all other reasons) is shown in Figure 3. Figure 4 displays the mean PANSS change at the discontinuation visit for patients discontinuing for lack of efficacy compared to all patients who did not discontinue for efficacy at the same visit. Since PANSS was not routinely measured at months 2, 4 and 5, these months compare PANSS scores only to patients who discontinued for a reason other than efficacy (intolerability, patient decision, administrative); continuing patients had no scores at these months. Across all visits, patients discontinuing for lack of efficacy had worsened mean change from baseline in the PANSS total score at the discontinuation visit (mean worsening ranged from 1.1 to 8.1 points) relative to a mean improvement of 0.6 to 12.5 for all patients not discontinuing for efficacy at the visit. Differences were noteworthy (p< 0.01) for all months except months 4 and 5. The mean difference [95% CI] at month 6 was −10.3 [−16.6, −4.1], and at month 12 was −11.0 [−17.8, −4.2]. The pattern of CGI-S scores was similar to PANSS (data not shown).

Figure 3. PANSS Mean Change from Baseline by Cohorts Based on Reason for Discontinuation and Duration of Phase Participation.

PANSS Total score is the sum of 30 items, and ranges from 30 (best) to 210 (worst). PANSS was measured at month 1, quarterly from months 3–18, and early phase discontinuation.

Sample size of PANSS cohorts: Discontinued for lack of efficacy at: month 1: n=49, month 2: n=55, month 3: n=64, month 4: n=36, month 5: n=21, month 6: n=26, months 7–9: n=40, months 10–12: n=24, Discontinued for other reasons: month 1: n=216, month 2: n=60, month 3: n=100, month 4: n=29, month 5: n=26, month 6: n=62, months 7–9: n=59, months 10–12: n=43, months 13–15: n=24, month 18 completers, n=371.

Figure 4. PANSS Mean Change from Baseline and 95% CI by Month for Patients Discontinuing for Lack of Efficacy Versus Discontinuing for Another Reason or Not Discontinuing at the Visit.

P< 0.01 at months 1, 2, 3, 6, 7–9, 10–12. Mean differences [95% CI] by month are: 1: −10.5 [−13.9, −7.0], 2: −12.4 [−17.7, −7.1], 3: −13.3 [−16.8, −9.7], 4: −6.2 [−16.2, 3.8], 5: −9.1 [−18.1, −0.1], 6: −10.3 [−16.6, −4.1], 7–9: −19.1 [−24.3, −13.8], 10–12: −11.0 [−17.8, −4.2].

Sample size of PANSS cohorts: Discontinued for lack of efficacy at: month 1: n=49, month 2: n=55, month 3: n=64, month 4: n=36, month 5: n=21, month 6: n=26, months 7–9: n=40, months 10–12: n=24, Discontinued for other reason or did not discontinue at: month 1: n=1263, month 2: n=60, month 3: n=856, month 4: n=29, month 5: n=26, month 6: n=633, months 7–9: n=531, months 10–12: n=458, months 13–15: n=396, month 18 completers, n=371.

Compared to all other patients, a substantially higher percent of patients who discontinued for intolerability reported a moderate to severe adverse event by systematic inquiry (87% vs. 65%, p < 0.001) or spontaneous report (51% vs. 32%, p < 0.001).

Patients who discontinued for patient decision had substantially lower compliance at their discontinuation visit (ranging from 37% to 77%) than all other patients at the same visit (ranging from 87% to 93%, p< 0.005 at all months except 4 and 5). At month 1, the mean difference in compliance was 49% (95% CI= [44, 54]), at month 12 the difference was 21% (95% CI= [15, 27]).

4.2. Reclassification of Patient Decision

We reviewed 428 cases of patient decision from the Phase 1 intent-to-treat population (randomized subjects who took at least one dose of study medication). The two initial raters’ blinded reclassifications did not agree for 8% of the cases, and these were subsequently reviewed by the second psychiatrist. In the resulting reclassification, 19 (5%) were reclassified as lack of efficacy, 91 (21%) were reclassified into intolerability, and 318 (74%) remained as patient decision. Patient decision was comprised of lack of compliance (8% of all cases), lack of insight (2%), administrative (1%), and withdrew consent/could not classify (63%).

Text strings classified as lack of efficacy generally indicated patients with hallucinations, paranoia, or delusions. Intolerability reclassification identified 30 cases of sedation, 8 extra-pyramidal symptoms, 4 sexual dysfunctions, and 2 weight gain. Many of the remaining 47 cases were not specified other than “side effects” in the text string, or were a conglomeration of several side effects. Text strings that were not reclassified from patient decision mostly contained no specific information other than patient withdrew consent, or lost to follow-up, but some contained vague descriptions that crossed several categories, such as: “Patient refuses due to subjective side effects that are likely delusionally based” and “Patient did not like the way he felt with the study medication.”

Characteristics of reclassified patients compared to other patient groups are shown in Table 1. Of note, reclassified patients participated in the next phase of the study at a substantially higher rate (67%) than those remaining in the patient decision category (10%), and a fairly similar rate to those originally classified as discontinuing for lack of efficacy or intolerability (80%). The fact that continuation in subsequent phases of the study was high for those originally and subsequently classified to lack of efficacy or intolerability suggests that these discontinuation events were informative for treatment group comparisons. Since most of the patients were willing to continue the study with an alternate medication, this suggests the reason for phase 1 discontinuation was due to dissatisfaction with the treatment and not dissatisfaction with general study procedures/participation. On the other hand, the low rate of continuation in subsequent study phases for those who remained classified as patient decision suggests that, although the phase 1 treatment discontinuation may be treatment-related, there is also an evident component of general study discontinuation that may be unrelated to the randomized treatment. Reclassified patients had a shorter time to discontinuation than all other groups, with a median of 1.8 months compared to 3.2 months for patients who remained patient decision (p< 0.001). Compliance for reclassified patients was not significantly different from non-reclassified patients (63% vs. 59%, mean difference = 4, 95% CI= [−4, 13], p=0.32); both groups had substantially lower compliance than Phase 1completers or those discontinuing for lack of efficacy or intolerability.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Reclassified Patients

| Remained Patient Decision (N=318) | Reclassified to Lack of Efficacy or Intolerability (N=110) | Discontinue d for Other Reason (N=633) | Completed Study in Phase 1 (N=371) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age mean (SD)1 | 40.1 (11.1) | 41.1 (10.3) | 39.6 (11.1) | 42.5 (11.1) |

| Gender (% Male) 2 | 76% | 81% | 71% | 76% |

| Race (% non-white) 3 | 50% | 45% | 36% | 36% |

| Years treated with antipsychotics mean (SD) 4 | 14.6 (10.2) | 16.3 (10.2) | 13.5 (10.4) | 15.1 (11.6) |

| Continued into next Phase (1B or 2) 5 | 31 9.7% | 74 67.3% | 504 79.6% | N/A |

| Time to discontinuation, months (median)6 | 3.2 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 18.2 |

| Compliance mean (SD)7 | 58.7 (37.3) | 63.0 (34.3) | 85.2 (22.7) | 92.2 (10.1) |

Note: N=1432 Intent to Treat Population. Discontinued for Other Reason = lack of efficacy, intolerability, administrative. P-values are for descriptive purposes.

p< 0.01 completed vs. disc for other reasons and remained, t-test

p< 0.05 reclassified vs. disc for other reasons, chi-squared test

p< 0.001 completed and disc for other reasons vs. remained, chi-squared test

p< 0.05 disc for other reasons vs. reclassified and completed, t-test

all 3 pair-wise p< 0.01, chi-squared test

p<0.001 for reclassified vs. other groups, Wilcoxon rank sum test

all pair-wise p < 0.001 except reclassified vs. remained (p=0.13), t-test

A comparison of the 19 patients reclassified to lack of efficacy versus the patients originally classified as lack of efficacy (Table 2) found that the reclassified patients had a shorter time to Phase 1 discontinuation (median 1.8 months vs. 3.5 months, p < 0.05) and lower compliance (70% vs. 86%, mean difference = 16, 95% CI=[1, 31], p=0.03), but demonstrated a worsening in PANSS total scores similar to those discontinuing for efficacy (4.1 versus 6.2, mean difference = 2.1, 95% CI=[−6.5, 10.8] ).

Table 2.

Outcome Characteristics for Patients Reclassified to Lack of Efficacy

| Lack of Efficacy (N=340) | Reclassified to Lack of Efficacy (N=19) | All Reasons Other than Lack of Efficacy (N=702) | Completed Study in Phase 1 (N=371) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to discontinuation, months (median)1 | 3.5 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 18.2 |

| Compliance Mean (SD)2 | 86.4 (21.7) | 70.3 (29.8) | 69.9 (34.0) | 92.2 (10.10 |

| PANSS change from baseline at last visit Mean (SD)3 | 6.2 (17.8) | 4.1 (16.3) | −2.9 (14.6) | −12.6 (17.7) |

Note: N=1432 intent-to-treat population. P-values are for descriptive purposes.

p < 0.05 except for Reclassified and Lack of Efficacy vs. Other Reasons, Wilcoxon rank sum test

p<=0.01 except for Reclassified vs. Other reasons, t-test

p<0.001 except for Reclassified vs. Other reasons and lack of efficacy, t-test

In spite of the fact that those reclassified to intolerability had a shorter duration in Phase 1 (median 1.8 months vs. 3.0 months, p=0.03) and lower compliance (62% vs. 87%, p < 0.001) than those classified as intolerability by the site investigator, a fairly similar percentage of patients reported moderate to severe AEs in these two groups compared to other patients not discontinuing for intolerability (spontaneously reported AEs 40% and 51%, compared to 27%, systematic inquiry AEs 69% and 87%, compared to 58%, Table 3).

Table 3.

Outcome Characteristics for Patients Reclassified to Intolerability

| Intolerability (N=213) | Reclassified to Intolerability (N=91) | All Reasons Other Than Intolerability (N=757) | Completed Study in Phase 1 (N=371) | |

| Time to discontinuation, months (median) 1 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 18.2 |

| Compliance Mean (SD) 2 | 86.7 (20.5) | 61.6 (35.1) | 73.7 (32.5) | 92.2 (10.1) |

| Any moderate or severe AE by spontaneous report (%) 3 | 51% | 40% | 27% | 40% |

| Any moderate or severe AE by systematic Inquiry (%) 4 | 87% | 69% | 58% | 78% |

Note: N=1432 intent-to-treat population. P-values are for descriptive purposes.

p<0.05 for reclassified vs. each other group

p<=0.01 for all comparisons

p=0.01 for reclassified vs. discontinued for other reasons

p<0.01 for intolerability vs. each other group, p=0.04 for reclassified vs. discontinued for other reasons

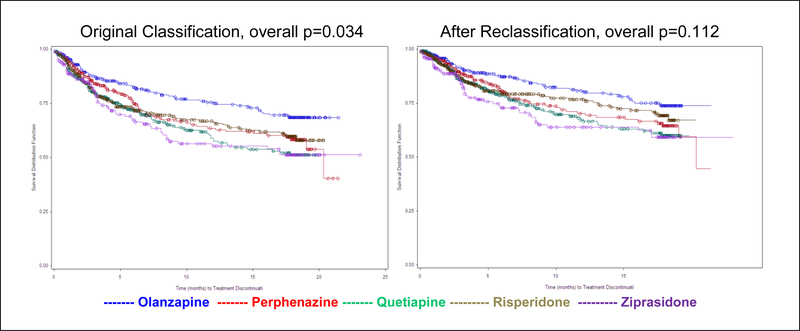

Across the five treatment groups, the percentage of patients who were reclassified was fairly similar. Reclassification to lack of efficacy ranged from 3% for olanzapine to 6% for perphenazine; reclassification to intolerability ranged from 16% for perphenazine to 27% for risperidone. An exploratory analysis comparing treatment groups for time to discontinuation due to patient decision while censoring the reclassified patients along with those discontinuing for other reasons no longer found significant treatment group differences (overall p=0.112 versus p=0.034 in the original analysis, Figure 5). Although the treatment group differences were attenuated, some differences were still suggestive.

Figure 5. Kaplan-Meier Plot of Time to Discontinuation Due to Reclassified Patient Decision.

Results were unchanged comparing treatment groups for discontinuation due to lack of efficacy when adding in the reclassified events. For discontinuation due to intolerability, a non-significant trend favoring risperidone in the original analysis (p=0.054) was no longer present after adding the reclassified intolerability events (p=0.377, data not shown).

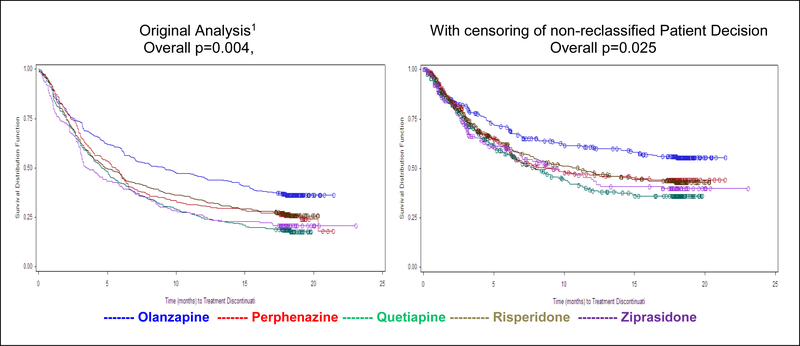

4.3. Analysis of Treatment Failure

Time to treatment failure had 663 failure events for lack of efficacy and intolerability, combined from the original and reclassified cases, 371 censored Phase 1 month 18 completers, and 398 censored cases from the patients originally classified as administrative plus those that remained classified as patient decision. Although censoring of the patient decision and administrative cases produced a weaker result compared to analysis of time to all-cause discontinuation, the overall test of treatment comparisons for treatment failure was still significant (p=0.025 compared to p=0.004 in the original analysis, Lieberman 2005). The differences between the treatment groups remained unchanged, with pair-wise hazard ratios and p-values for olanzapine compared to the other treatments essentially identical to the original analysis (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Sensitivity Analysis of Time to Discontinuation With Censoring of Non-Reclassified Events of Patient Decision.

5. DISCUSSION

The graphical evaluation of clinical outcome response profiles suggested that patients who discontinued treatment had poorer scores for relevant clinical measurements compared to other patients. This relationship was evident between all-cause discontinuation and quality of life and SF-12 mental functioning scores, as well as between each of the secondary reasons for discontinuation and corresponding outcomes (lack of efficacy: PANSS and CGI-S scores; intolerability: AE incidence; patient decision: compliance). The trends for poorer outcomes supports the appropriateness of treatment discontinuation as a meaningful measure. At the same time, the application of survival methods to all-cause discontinuation avoids the problem seen in analysis methods for repeated clinical measurements of how to handle missing data caused by discontinuations.

The three secondary outcomes of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy, intolerability, or patient decision have competing risks: any of the three may happen, and once a subject has discontinued for one reason, it is unknown if they might have discontinued for a different reason at a later time. Censoring other reasons for discontinuation when analyzing one reason assumes the three outcomes are independent; in other words, someone at high risk of discontinuing due to one reason is no more or less likely to discontinue due to one of the other reasons (Alison 2010). Valid estimation is possible for each reason for discontinuation at a specified time, given that a patient has not yet discontinued. It is plausible that the probability of the events may not be independent. For instance, a subject discontinuing for patient decision because of side effect dissatisfactions may have been at a higher risk for discontinuation for intolerability not yet recognized by the site investigator. If the events are not independent, then the competing risks analysis might not provide a valid comparison of the treatment groups for each specific discontinuation reason. An advantage of time to all-cause discontinuation (the primary CATIE outcome) is that treatment group comparisons are valid regardless of the independence of the competing risks. Some cutting-edge strategies which evaluate multivariate risks without assuming independence of the competing events are discussed by Peng (2007) and Cheng (2007). Cumulative incidence functions provide a descriptive approach which does not rely on independence of event types (Allison 2010). The cumulative incidence functions for time to each event (lack of efficacy, tolerability, patient decision) displayed the same treatment group patterns as the competing-risks Kaplan-Meier plots (data not shown).

For the patients who were reclassified from patient decision to lack of efficacy or intolerability, their reported symptoms were apparently not, in the opinion of the site investigator, of concern enough to end treatment. In general, the reclassified patients tended to have poor compliance and discontinued quickly because of moderate concerns/complaints. Since relatively few patients were reclassified to lack of efficacy, it seems that site investigators rarely missed an efficacy concern. However, the fact that 20% of patients discontinuing for patient decision (91 of 428) were reclassified to intolerability suggests it may be fairly common for patients to have side effects whose intolerability from the patient’s perspective is under-recognized by the site investigator. If a more careful description of the subject’s concern had been consistently provided in the case report form, then even more cases of patient decision might have been reclassified into lack of efficacy or intolerability.

In a review of the CATIE design, Kraemer et al (2009) concur with our use of a single primary integrative outcome such as time to all-cause discontinuation. In order to reduce site effects, they recommend that the reason for discontinuation be determined not by the site investigator, but instead by an independent adjudication committee. However, since CATIE was an effectiveness trial, we wanted the design to reflect standard medical practice to the extent possible, which would not be achieved by the use of an external adjudication committee. Kraemer also argued for the use of treatment failure instead of all-cause discontinuation. Since treatment failure assumes that all censored patient decision discontinuations are non-informative for treatment comparisons, our post-hoc review of patient reason for discontinuation suggests such a definition would indeed require careful classification of all events to determine which were treatment failures. Our experience indicates an adjudication committee would not likely be able to extract all events that are informative for treatment group comparisons from the patient decision category, especially for a psychiatric disease such as schizophrenia. On the other hand, we would argue that one of the most appealing aspects of all-cause discontinuation is that no classification of cause is required for the primary outcome. Kraemer states “in CATIE, this problem [with including non-informative cases as events] could even now be mitigated by survival analysis treating discontinuation for other reasons as censored. However, that would profoundly change the results.” Nevertheless, the analysis of time to treatment failure provided essentially similar results as the original analysis, although somewhat weaker.

While focusing on the CATIE trial, this paper has identified some topics applicable to many Phase II-IV pharmaceutical clinical trials. First, time to all-cause discontinuation is a useful outcome for many clinical trials, providing a simple all-encompassing treatment group comparison of overall effectiveness. Second, graphical evaluation of outcome response profiles by discontinuation cohorts was shown to be a helpful tool to explore the response pattern for patient drop-outs. Our evaluations showed that patients who discontinue tend to have different response profiles than completers, varying by the reason for discontinuation. We demonstrated that patients discontinuing for patient decision, including lost to follow-up or withdrawal of consent, may be a “mixed bag” of poor compliance, lack of efficacy and intolerability. It is worthwhile in a study to carefully collect a description of a patient’s reason for early discontinuation.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Evaluation of time to all-cause discontinuation supported its use as an appropriate primary outcome in the CATIE trial. While avoiding statistical concerns caused by missing data due to informative patient drop-out, it showed strong association with relevant clinical correlates such as quality of life, efficacy assessments, adverse events, and treatment compliance. Although subjects who discontinued due to patient decision had lower compliance, relevant information for treatment group comparisons was evident in these patients. Even after reclassification based on recorded comment fields, some relevant information for treatment group comparisons was still evident in those who remained classified as patient decision, as seen by a trend for treatment group differences. All-cause discontinuation provided somewhat stronger results for treatment comparisons compared to a more restrictive definition of treatment failure, although both outcomes provided similar conclusions.

Acknowledgement

Supported in part by a grant (N01 MH90001) from the NIMH.

References

- Alison P (2010), “Survival Analysis Using the SAS® System: A Practical Guide, Second Edition” Cary, N.C., SAS Institute, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Fine JP, Kosorok MR (2007), “Nonparametric Association Analysis of Bivariate Competing Risks Data,” Journal of American Statistical Association, 102(480), 1407–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Cox D (1972), “Regression models and Life Tables,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, B34, 187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Davis SM, Koch GG, Davis CE, and LaVange LM (2003), “ Statistical approaches to effectiveness measurement and outcome-driven re-randomizations in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) studies,” Schizophrenia Bulletin, 29(1), 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueorguieva R, Rosenheck R, Lin H (2010) “Joint Modeling of Longitudinal Measurements and Interval-censored competing risk data,” In submission. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT (1984), “The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome,” Schizophrenia Bulletin, 10:388–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson R, Diggle P, and Dobson A (2000), “Joint modeling of longitudinal measurements and event time data,” Biostatistics 4, 465–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan JW and Laird NM (1997). “Mixture models for the joint distributions of repeated measures and event times,” Statistics in Medicine 16, 239–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung HMJ (2004),”Management of Missing data in Clinical Trials from a regulatory Perspective”, presented at American Statistical Association Biopharmaceutical section FDA/Industry Workshop. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Glick ID, Klein DF (2009), “Clinical trials design lessons from the CATIE study,” American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(11), 1222–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, Keefe RS, Davis SM, Davis CE, Lebowitz BD, Severe J, and Hsiao JK for the CATIE investigators (2005), “Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia,”. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(12), 1209–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA (1993), “Pattern-Mixture Models for Multivariate Incomplete Data,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 88(421), 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, Davis SM, Rosenheck RA, Swartz MS, Perkins DO, Keefe RSE, Davis CE, Severe J, and Hsiao JK for CATIE Investigators (2006), “Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment,” American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 600–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohidul S, Hung HMJ, O’Neill R (2009), “MMRM vs. LOCF: A Comprehensive Comparison Based on Simulation Study and 25 NDA Datasets,” Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics, 19(2), 227–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Fine J, P. (2007), “Regression Modeling of Semi-competing Risks Data,” Biometrics 63, 96–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saville BR, Herring AH, and Koch GG (2010), “A robust method for comparing two treatments in a confirmatory clinical trial via multivariate time-to-event methods that jointly incorporate information from longitudinal and time-to-event data,” Statistics in Medicine, 29 75–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup TS, Lieberman JA, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Davis SM, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, Keefe RSE, Davis CE, Severe J, Hsiao JK for the CATIE Investigators. (2006), “Effectiveness of olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia after discontinuing a previous atypical antipsychotic,” American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 611–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup TS, Lieberman JA, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Davis SM, Capuano G, Rosenheck RA, Keefe RSE, Miller A, Belz I, Hsiao JK for the CATIE Investigators. (2007), “Effectiveness of Olanzapine, Quetiapine, and Risperidone in Patients with Chronic Schizophrenia after Discontinuing Perphenazine: A CATIE Study,” American Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 415–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulfsohn MS, and Tsiatis AA (1997) “A Joint Model for Survival and Longitudinal Data Measured with Error, “Biometrics, 53(1), 330–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]