Abstract

BACKGROUND

Research examining the role of second opinions in pathology for diagnosis of melanocytic lesions is limited.

OBJECTIVE

To assess current laboratory policies, clinical use of second opinions, and pathologists’ perceptions of second opinions for melanocytic lesions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cross-sectional data collected from 207 pathologists in 10 US states who diagnose melanocytic lesions. The web-based survey ascertained pathologists’ professional information, laboratory second opinion policy, use of second opinions, and perceptions of second opinion value for melanocytic lesions.

RESULTS

Laboratory policies required second opinions for 31% of pathologists and most commonly required for melanoma in situ (26%) and invasive melanoma (30%). In practice, most pathologists reported requesting second opinions for melanocytic tumors of uncertain malignant potential (85%) and atypical Spitzoid lesions (88%). Most pathologists perceived that second opinions increased interpretive accuracy (78%) and protected them from malpractice lawsuits (62%).

CONCLUSION

Use of second opinions in clinical practice is greater than that required by laboratory policies, especially for melanocytic tumors of uncertain malignant potential and atypical Spitzoid lesions. Quality of care in surgical interventions for atypical melanocytic proliferations critically depends on the accuracy of diagnosis in pathology reporting. Future research should examine the extent to which second opinions improve accuracy of melanocytic lesion diagnosis.

Although histopathologic examination remains the reference standard for the diagnosis of melanocytic neoplasms, these lesions are often diagnostically challenging and subject to diagnostic disagreement.1–3 Second opinions are often obtained for these lesions and may be helpful for lesions considered borderline due to histopathologic criteria that bridge two or more taxonomic categories of melanocytic lesion diagnosis.

Although second opinions may be obtained at the discretion of the primary pathologist, many laboratories have implemented policies mandating second opinion consultations to improve diagnostic accuracy and patient care.1,4–8 Previous research examining second opinions in dermatopathology has been limited to single-institution studies and has largely focused on the influence of specialized dermatopathologic training in reducing diagnostic errors.1,2,9–11 In two single-institution studies of referred skin lesion cases subsequently reviewed by dermatopathology experts, diagnoses changed after second opinions in 22%1 and 35% of cases.2 In another single-institution study, the discordance rate between the first and second readings of melanomas and nevi was 14%.9 Although pathologists and dermatologists have been found to have similar second opinion referral patterns, dermatopathologists refer to a much larger proportion of melanocytic lesions for second opinions.10

The extent to which second opinions improve diagnostic accuracy will influence the quality of care when surgical intervention is deemed indicated for atypical melanocytic proliferations from pathology reporting. Currently, little is known about the frequency of use of second opinion consultations within pathology groups in the evaluation of melanocytic neoplasms. To address these knowledge gaps, the authors conducted a national survey of pathologists to assess the existence of second opinion policies in the current clinical practice and perceptions of pathologists currently in practice in the United States.

Materials and Methods

Overview and Recruitment

The Melanoma Pathology Study (M-Path) was designed to investigate the extent and potential impact of diagnostic variability among pathologists interpreting melanocytic lesions in 10 US states. A detailed description of this study has been reported elsewhere.12,13 Pathologists eligible for participation had completed their pathology training (residency and/or fellowship), diagnosed melanocytic lesions in practice within the previous year, and expected to continue diagnosing melanocytic lesions for the next 2 years. Eligible pathologists were invited to take part in the study through electronic mail. Institutional Review Board approval for this study was obtained from the University of Washington, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Oregon Health & Sciences University, Rhode Island Hospital, and Dartmouth College.

Data Collection Procedures and Materials

Participants completed a web-based informed consent form and baseline survey. Investigators developed the survey content in consultation with a panel of dermatopathologists and dermatologists. The survey was extensively pilot tested before administration. The final baseline survey asked pathologists about general professional information (demographics, training, and clinical practice) and collected data about second opinion policies in their laboratories, as well as their clinical use and perceptions of second opinion for melanocytic skin lesions (MSLs).

Key Measures

The authors collected data on age, sex, and professional training and background including type of residency, type of fellowship, board certification, and current affiliation with an academic medical center. The authors also obtained information on participants’ experiences interpreting melanocytic neoplasms. These included total number of years spent interpreting melanocytic neoplasms, percentage of usual caseload comprising melanocytic lesions, number of melanoma cases interpreted per typical month, number of second opinions sought for melanocytic lesions in a typical month, number of second opinions requested of the participant in a typical month, and whether participants’ colleagues considered them experts in the assessment of melanocytic neoplasms.

In addition, participants were asked to indicate the percentage of cases for which they sought second opinions in actual practice for 9 categories of melanocytic lesions (melanocytic lesions in general; dysplastic nevus, mild; dysplastic nevus, moderate; dysplastic nevus, severe; melanocytic tumors of uncertain malignant potential [MELTUMP]; melanoma in situ; invasive melanoma; Spitz nevus conventional; atypical Spitzoid lesion). For each category, participants were also asked to report the percentage of cases for which their laboratories required obtaining second opinions. Participants who reported greater than 0% were considered as having a policy for second opinions.

Participants were also provided with the following hypothetical scenario related to second opinions: “You are reviewing a skin specimen from a 45-year- old woman with no family history of melanoma. You are uncertain how to diagnose the lesion because it appears to be intermediate between melanoma in situ and invasive melanoma, but you favor diagnosing as melanoma in situ.” Participants were asked to respond to the following 2 questions: “In situations like this, in what percentage of cases would you get a second opinion (either in house or external review)?” and “If you were to obtain a second opinion, would your second pathologist usually be blinded to your opinion on the case?”

Then, as an extension of the above scenario, the authors presented pathologists with the follow-up question: “If you were to obtain a second opinion on a case you considered to be melanoma in situ, and the second reviewer favored a diagnosis of invasive melanoma, how frequently would you use the following strategies to come to consensus?” Participants were provided with 6 possible responses to the hypothetical situation (full survey available in Supplemental Digital Content 1, Appendix 1, http://links.lww.com/DSS/A79 ).

Statistical Analyses

Comparisons across groups were performed using Pearson’s Chi-square test. Analysis of continuous data included determination of means and comparisons. For the perception questions, data were collected using a 6-point Likert scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” which the authors collapsed into the following 4 categories: (1) strongly disagree or disagree; (2) slightly disagree; (3) slightly agree; and (4) agree or strongly agree. Responses to the hypothetical scenario were collected using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from “never or almost never” to “always or almost always” and were collapsed for analysis into 3 categories: (1) never or almost never, infrequently; (2) about half the time; and (3) frequently, almost always, or always.

Responses to questions about policy requirements and actual practice were analyzed both as continuous (medians and interquartile ranges [IQRs]) and categorical variables. The authors dichotomized continuous responses for each of the 9 melanocytic diagnoses, where a response of more than 0% was considered “policy,” whereas “no policy” was the absence of any policy for all diagnoses, then the authors combined the responses to indicate “policy” and “no policy” across all diagnoses. Pearson Chi-square test was used for unpaired data, and the McNemar test of agreement for paired data. The association between expert and nonexpert responses on Likert scales was tested using the Mantel-Haenszel statistic with modified ridit scores to account for ordered categories. For paired continuous data, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare responses of policy versus actual practice. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and results were considered statistically significant if p < .05. SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

A total of 207 pathologists participated in the study, representing 69% of eligible respondents. Most participants were not affiliated with an academic medical center (71%), were not board certified in dermatopathology (61%), worked in laboratories with less than 5 pathologists (68%), and had practices in which MSLs comprised 10% or more of their usual caseloads (57%) (Table 1). Forty-three percent reported that they were considered an expert in MSLs by their colleagues.

TABLE 1.

Training and Experience of Participating Pathologists Overall and by Whether or Not Their Laboratory Has a Second Opinion Policy

| Pathologist Training and Experience | Total n (col %) | No Policy n (row %) | Policy* n (row %) | p† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 207 (100) | 142 (69) | 65 (31) | |

| Affiliation with academic medical center | .49 | |||

| No | 148 (71) | 104 (70) | 44 (30) | |

| Yes, adjunct/affiliated | 38 (18) | 23 (61) | 15 (40) | |

| Yes, primary appointment | 21 (10) | 15 (71) | 6 (29) | |

| Residency training | .29 | |||

| Pathology only | 186 (90) | 125 (88) | 61 (94) | |

| Dermatology only | 17 (8) | 13 (9) | 4 (6) | |

| Both pathology and dermatology | 4 (2) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Board certified and/or fellowship trained in dermatopathology‡ | .29 | |||

| Yes | 81 (39) | 59 (73) | 22 (27) | |

| No | 126 (61) | 83 (66) | 43 (34) | |

| Laboratory group practice size | .33 | |||

| <5 Pathologists | 140 (68) | 93 (66) | 47 (34) | |

| ≥5 Pathologists | 67 (32) | 49 (73) | 18 (27) | |

| Percent of caseload interpreting MSLs | .25 | |||

| <10 | 90 (43) | 56 (62) | 34 (38) | |

| 10–24 | 79 (38) | 57 (72) | 22 (28) | |

| 25–49 | 29 (14) | 21 (72) | 8 (28) | |

| ≥50 | 9 (5) | 8 (89) | 1 (11) | |

| In a typical month, how many MSLs do you receive from pathologist colleagues seeking a second opinion? | .46 | |||

| None | 52 (25) | 40 (77) | 12 (23) | |

| 1–9 | 60 (29) | 38 (63) | 22 (37) | |

| 10–24 | 63 (30) | 43 (68) | 20 (32) | |

| ≥25 | 32 (16) | 21 (66) | 11 (34) | |

| In a typical month, for how many MSLs do you request a second opinion? | .008 | |||

| None | 22 (11) | 19 (86) | 3 (14) | |

| 1 | 54 (26) | 43 (80) | 11 (20) | |

| 2–4 | 41 (20) | 30 (73) | 11 (27) | |

| 5–9 | 40 (19) | 22 (55) | 18 (45) | |

| ≥10 | 50 (24) | 28 (56) | 22 (44) | |

| For what percentage of MSLs is your final assessment that the diagnosis is borderline or uncertain? | .86 | |||

| None | 21 (10) | 16 (76) | 5 (24) | |

| 1 | 52 (25) | 33 (64) | 19 (37) | |

| 2–4 | 41 (20) | 28 (68) | 13 (32) | |

| 5–9 | 58 (28) | 41 (71) | 17 (29) | |

| ≥10 | 35 (17) | 24 (69) | 11 (31) | |

| Are you considered an expert in MSLs by colleagues? | .16 | |||

| No | 119 (57) | 77 (65) | 42 (35) | |

| Yes | 88 (43) | 65 (74) | 23 (26) |

Percentages might not add up to 100 because of rounding.

Policy was dichotomized to “no policy” (includes “not applicable” and coverage of 0%) versus having a policy requiring a second opinion for at least 1 among 9 diagnoses of melanoma (in which percentage of cases requiring a second opinion was >0%).

p-value for difference between “no policy” and “policy” using the Chi-square test.

This category consists of physicians with single or multiple fellowships that include dermatopathology. Also includes physicians with single or multiple board certifications that include dermatopathology.

MSLs, melanocytic skin lesions.

For melanocytic lesions in general, only a small-minority of pathologists (7%) were required by policy at their laboratory to obtain second opinions, whereas most pathologists (81%) sought second opinions for these lesions in practice. Across all diagnostic subcategories of melanocytic diagnoses, pathologists obtained second opinions substantially more often than required by laboratory policies (Figure 1). The discrepancy between policy and practice was most modest (2.7-fold) for invasive melanoma and exceeded 10-fold for conventional Spitzoid lesions and mild dysplastic nevi. The IQR of reported use of second opinions in clinical practice also varied among the diagnoses. For instance, there was a large range in actual practice for moderately dysplastic nevi, melanoma in situ, and invasive melanoma, whereas much less for a range for MELTUMPS and atypical Spitzoid lesions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The percent of pathologists who work in laboratories who have second opinion policies, their actual second opinion practice, and the median percent of cases requested, by diagnoses (N = 207). The reported continuous responses for policy and actual practice were dichotomized into categories of Yes when the response to each survey question was greater than 0% and No when responses included 0% or missing. All comparisons were significant for differences in paired proportions and medians of policy versus practice (p < .001). Median for policy was 100% for all diagnoses except melanocytic lesions in general which was 20%. IQR, interquartile range; MELTUMP, melanocytic tumor of uncertain malignant potential.

Laboratory policies requiring second opinions were most frequently in place for melanoma in situ (26%) and invasive melanoma (30%) (Figure 1). In actual practice, 81% and 82% of pathologists sought second opinions for these 2 diagnoses, respectively. The 2 diagnoses for which most pathologists sought a second opinion were atypical Spitzoid lesions (88%) and MELTUMP (85%), whereas laboratory policy was in place for only 12% and 16% of these 2 diagnostic categories, respectively. All comparisons were statistically significant for differences in paired proportions and medians of policy versus practice (p < .001).

When pathologists were presented with the hypothetical scenario, “You are reviewing a skin specimen from a 45-year-old woman with no family history of melanoma. You are uncertain how to diagnose the lesion because it appears to be intermediate between melanoma in situ and invasive melanoma, but you favor diagnosing as melanoma in situ,” the majority (84%; SD 31%) said they would obtain a second opinion. When asked whether the second reviewer would usually be blinded to their initial opinion, 52% responded that they would blind the second reviewer to their own initial interpretation of the case. As an extension of the above scenario, pathologists were then asked the follow-up question: “If you were to obtain a second opinion on a case you considered to be melanoma in situ, and the second reviewer favored a diagnosis of invasive melanoma, how frequently would you use the following strategies to come to consensus?” Of the 6 possible (nonexclusive) consensus resolutions to this hypothetical scenario (data not shown), the 2 approaches reported most frequently were to use the most experienced pathologist’s opinion (55%) and obtain a third opinion or present the lesion at a consensus conference (54%). The third most frequently reported approach was to discuss the case with the second reviewer until agreement was reached (44%). Less frequently, participants reported that they would resolve the hypothetical scenario by diagnosing the case as invasive melanoma to go with the more severe diagnosis (20%), followed by diagnosing the case as borderline between 2 diagnoses in a report (15%). By far, the least frequent resolution was to diagnose the case as melanoma in situ to go with the less severe diagnosis (4%).

Resolution strategies differed depending on whether the participant was considered an expert by colleagues (N = 88; 43%) or not (N = 119; 57%) (Figure 2). For nonexperts, the most frequently reported resolution methods were to obtain a third opinion or present the case at a consensus conference (64%), followed by using the most experienced pathologist’s opinion (57%). Experts were statistically significantly more likely than nonexperts to discuss the case with the second reviewer until consensus was reached (50%; p = .049). The least common strategies reported by nonexperts were to diagnose as melanoma in situ to go with the less severe diagnosis (3%), followed by indicating the case as borderline between 2 diagnoses in the report (8%). By contrast, 7% of experts favored using the less severe diagnosis, and 25% favored applying a borderline diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Participating pathologists’ responses to the following hypothetical scenario, “If you were to obtain a second opinion on a case you considered to be melanoma in situ, and the second reviewer favored a diagnosis of invasive melanoma, how frequently would you use the following strategies to come to consensus?” shown by the pathologists’ response to “Do your colleagues consider you an expert in the assessment of melanocytic skin lesions.” Experts are participants who reported that their colleagues considered them an expert in the assessment of MSLs. Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding. MSLs, melanocytic skin lesions.

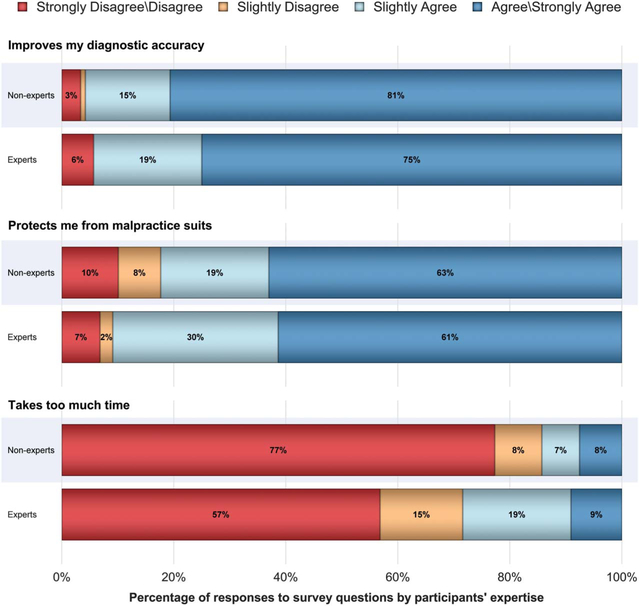

Pathologists’ perceptions of second opinions were generally favorable (Figure 3). Experts and nonexperts perceived that second opinions improve their diagnostic accuracy and protect them from malpractice suits. However, 28% of experts stated that obtaining a second opinion requires too much time, compared with 15% of the nonexpert group (p = .003).

Figure 3.

Responses to thoughts about requesting a second opinion for MSLs shown by the pathologists’ response to “Do your colleagues consider you an expert in the assessment of melanocytic skin lesions.” Experts are participants who reported that their colleagues considered them an expert in the assessment of MSLs. Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding. MSLs, melanocytic skin lesions.

Discussion

Although only a minority of the study pathologists worked in laboratories with policies requiring second opinion consultations, most pathologists used second opinions in practice, demonstrating that they value this strategy. Similar to breast pathologists,14 most pathologists perceived that second opinions improve diagnostic accuracy and protect them from malpractice suits.

Expert and nonexpert pathologists did not always use the same strategies to resolve diagnostic disagreements between 2 pathologists in the authors’ hypothetical scenario. Experts were more likely to use a diagnosis of borderline (or a descriptive diagnosis of “uncertain”) in their reports than nonexperts. This finding may indicate that experts are more comfortable expressing uncertainty, rather than selecting one seemingly more specific term, even in the absence of adequate criteria to justify a confident interpretation. This result is supported by a small study in which 2 international experts reviewed difficult to interpret melanocytic lesions sent for consultation and used the terms MELTUMP and superficial atypical melanocytic proliferation of uncertain significance (SAMPUS) to reflect diagnostic uncertainty.11

The nomenclature used in describing and diagnosing MSLs is not standardized,11,15 and the diagnostic categories in the authors’ survey may be different from what the participating pathologists use in their practices. This discrepancy may have led to inaccurate results concerning policy and actual practice. Inconsistent use of terms may confuse the results of second opinions. The authors’ research group has recommended the adoption of simple diagnostic categories to help standardize and clarify melanocytic diagnoses.16

Pathologists who participated in this study reported valuing second opinions and using them frequently in their own practice. There are some data that suggest obtaining second opinions on melanocytic lesions would improve clinical care. In a retrospective review of 478 melanocytic skin biopsy lesions referred for surgery in a large teaching hospital, 168 cases (35%) had changes in diagnoses from the initial diagnosis on review of referral materials, with the changes in diagnoses affecting patient therapy in 64 patients (13%).

In this study, the most common diagnoses for which a second opinion was required by laboratory policy were melanoma in situ and invasive melanoma, although less than one-third of pathologists worked in laboratories with mandated policies involving these lesions. More difficult lesions such as MELTUMPs and atypical Spitzoid lesions were covered by policy at less than 20% of laboratories, and more than 80% of pathologists would submit these lesions for review. A recent large study in Australia of patients diagnosed with melanoma referred to a specialty institute was reviewed by expert melanoma pathologists. The diagnosis changed in melanoma in situ 22% of the time, with 20% upstaged to invasive melanoma and 1.5% downstaged to benign lesions.17 Future research should continue to examine the value of second opinions in clinical practice and how policies that require consultations affect the diagnostic accuracy of melanocytic lesions.

Second opinion has been shown to improve patient management2,3,6 and is probably reassuring to both patients and the referring clinicians. The use of second opinion can be educational for less experienced clinicians and those in need of more training in dermatopathology. Second opinion has also been shown to be cost effective when the correct diagnosis reduces the amount of therapy or eliminates the need for therapeutic interventions altogether.18

The true biologic nature of certain melanocytic lesions remains unclear. Because there is no obvious current gold standard for diagnosis besides histopathologic interpretation, and no single available ancillary test that is consistently helpful for diagnosing challenging melanocytic lesions, second opinions for these lesions, by contrast, may be of considerable value. The accumulated experience of particular expert consultants allows for both the expression of uncertainty and also for guidance about optimal management of ambiguous melanocytic lesions. One of the greatest threats to excellent patient care in these circumstances is the failure to recognize and appropriately manage melanocytic lesions with potential risk for recurrence and/or metastasis. Although there may be interobserver differences among experts about the interpretation of ambiguous lesions, there is often greater consensus about the diagnosis and ultimate management of such lesions. However, a second opinion may not necessarily get one close to the truth but rather closer to the truth as the pathologist rendering the second opinion sees it.

Strengths of the study include the representation of pathologists from 10 states across the United States with academic and nonacademic affiliations as well as a broad array of training and interpretive experiences. Limitations of this study include the self-reported nature of the survey data, such as perceptions of expertise and perceptions of behaviors, which would likely have more inherent bias than more objective measures. Our survey was not able to address the impact of a second opinion on the original pathologist’s interpretation.

Second opinion is used often in actual practice as it is likely viewed as a valuable asset in improving diagnostic accuracy, thus improving patient care, in particular when dermatological surgical intervention is contemplated as indicted from the pathology report.2 Use of second opinions in clinical practice by pathologists is greater than that required by laboratory policies, especially for melanocytic tumors of uncertain malignant potential and atypical Spitzoid lesions. Future research should continue to examine the extent to which second opinions affect accurate diagnosis of MSLs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA151306 and R01 CA201376). The authors have indicated no significant interest with commercial supporters. Institutional review board approval for this study was obtained from the University of Washington, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Oregon Health & Sciences University, Rhode Island Hospital, and Dartmouth College. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the full text and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.dermatologicsurgery.org).

References

- 1.Gaudi S, Zarandona J, Raab S, English JC, et al. Discrepancies in dermatopathology diagnoses: the role of second review policies and dermatopathology fellowship training. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;68: 119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawryluk E, Sober A, Piris A, Nazarian RM, et al. Histologically challenging melanocytic tumors referred to a tertiary care pigmented lesion clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:727–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Dijk M, Aben K, van Hees F, Klaasen A, et al. Expert review remains important in the histopathological diagnosis of cutaneous melanocytic lesions. Histopathology 2008;52:139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frable W Surgical pathology—second reviews, institutional reviews, audits, and correlations: what’s out there? Error or diagnostic variation? Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006;130:620–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kronz J, Westra W, Epstein J. Mandatory second opinion surgical pathology at a large referral hospital. Cancer 1999;86:2426–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manion E, Cohen M, Weydert J. Mandatory second opinion in surgical pathology referral material: clinical consequences of major disagreements. Am J Surg Path 2008;32:732–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakhleh R, Bekeris L, Souers R, Meier FA, et al. Surgical pathology case reviews before sign-out: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 45 laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010;134: 740–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swapp R, Aubry M, Salomão D, Cheville JC. Outside case review of surgical pathology for referred patients: the impact on patient care. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2013;137:233–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shoo B, Sagebiel R, Kashani-Sabet M. Discordance in the histopathologic diagnosis of melanoma at a melanoma referral center. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;62:751–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldenberg G, Camacho F, Gildea J, Golitz LE. Who sends what: a comparison of dermatopathology referrals from dermatologists, pathologists and dermatopathologists. J Cutan Pathol 2008;35:658–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pusiol T, Morichetti D, Piscioli F, Zorzi MG. Theory and practical application of superficial atypical melanocytic proliferations of uncertain significance (SAMPUS) and melanocytic tumours of uncertain malignant potential (MELTUMP) terminology: experience with second opinion consultation. Pathologica 2012;104:70–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onega T, Reisch L, Frederick P, Geller BM, et al. Use of digital whole slide imaging in dermatopathology. J Digit Imaging 2016;29:243–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elmore JG, Barnhill RL, Elder DE, Longton GM, et al. Pathologists’ diagnosis of invasive melanoma and melanocytic proliferations: observer accuracy and reproducibility study. BMJ 2017;357:j2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geller B, Nelson HD, Carney PA, Weaver DL, et al. Second opinion in breast pathology: policy, practice and perception. J Clin Pathol 2014; 67:955–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnhill R, Cerroni L, Cook M, Elder DE, et al. State of the art, nomenclature, and points of consensus and controversy concerning benign melanocytic lesions: outcome of an international workshop. Adv Anat Pathol 2010;17:73–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piepkorn MW, Barnhill RL, Elder DE, Knezevich SR, et al. The MPATH-Dx reporting schema for melanocytic proliferations and melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:131–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niebling MG, Haydu LE, Karim RZ, Thompson JF, et al. Pathology review significantly affects diagnosis and treatment of melanoma patients: an analysis of 5011 patients treated at a melanoma treatment center. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:2245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epstein J, Walsh P, Sanfilippo F. Clinical and cost impact of second-opinion pathology. Review of prostate biopsies prior to radical prostatectomy. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:851–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.