Abstract

Background

Historically, women have generally been attended and supported by other women during labour. However, in hospitals worldwide, continuous support during labour has often become the exception rather than the routine.

Objectives

The primary objective was to assess the effects, on women and their babies, of continuous, one‐to‐one intrapartum support compared with usual care, in any setting. Secondary objectives were to determine whether the effects of continuous support are influenced by:

1. Routine practices and policies in the birth environment that may affect a woman's autonomy, freedom of movement and ability to cope with labour, including: policies about the presence of support people of the woman's own choosing; epidural analgesia; and continuous electronic fetal monitoring.

2. The provider's relationship to the woman and to the facility: staff member of the facility (and thus has additional loyalties or responsibilities); not a staff member and not part of the woman's social network (present solely for the purpose of providing continuous support, e.g. a doula); or a person chosen by the woman from family members and friends;

3. Timing of onset (early or later in labour);

4. Model of support (support provided only around the time of childbirth or extended to include support during the antenatal and postpartum periods);

5. Country income level (high‐income compared to low‐ and middle‐income).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (31 October 2016), ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (1 June 2017) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

All published and unpublished randomised controlled trials, cluster‐randomised trials comparing continuous support during labour with usual care. Quasi‐randomised and cross‐over designs were not eligible for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and risk of bias, extracted data and checked them for accuracy. We sought additional information from the trial authors. The quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included a total of 27 trials, and 26 trials involving 15,858 women provided usable outcome data for analysis. These trials were conducted in 17 different countries: 13 trials were conducted in high‐income settings; 13 trials in middle‐income settings; and no studies in low‐income settings. Women allocated to continuous support were more likely to have a spontaneous vaginal birth (average RR 1.08, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.04 to 1.12; 21 trials, 14,369 women; low‐quality evidence) and less likely to report negative ratings of or feelings about their childbirth experience (average RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.79; 11 trials, 11,133 women; low‐quality evidence) and to use any intrapartum analgesia (average RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.96; 15 trials, 12,433 women). In addition, their labours were shorter (MD ‐0.69 hours, 95% CI ‐1.04 to ‐0.34; 13 trials, 5429 women; low‐quality evidence), they were less likely to have a caesarean birth (average RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.88; 24 trials, 15,347 women; low‐quality evidence) or instrumental vaginal birth (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.96; 19 trials, 14,118 women), regional analgesia (average RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.99; 9 trials, 11,444 women), or a baby with a low five‐minute Apgar score (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.85; 14 trials, 12,615 women). Data from two trials for postpartum depression were not combined due to differences in women, hospitals and care providers included; both trials found fewer women developed depressive symptomatology if they had been supported in birth, although this may have been a chance result in one of the studies (low‐quality evidence). There was no apparent impact on other intrapartum interventions, maternal or neonatal complications, such as admission to special care nursery (average RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.25; 7 trials, 8897 women; low‐quality evidence), and exclusive or any breastfeeding at any time point (average RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.16; 4 trials, 5584 women; low‐quality evidence).

Subgroup analyses suggested that continuous support was most effective at reducing caesarean birth, when the provider was present in a doula role, and in settings in which epidural analgesia was not routinely available. Continuous labour support in settings where women were not permitted to have companions of their choosing with them in labour, was associated with greater likelihood of spontaneous vaginal birth and lower likelihood of a caesarean birth. Subgroup analysis of trials conducted in high‐income compared with trials in middle‐income countries suggests that continuous labour support offers similar benefits to women and babies for most outcomes, with the exception of caesarean birth, where studies from middle‐income countries showed a larger reduction in caesarean birth. No conclusions could be drawn about low‐income settings, electronic fetal monitoring, the timing of onset of continuous support or model of support.

Risk of bias varied in included studies: no study clearly blinded women and personnel; only one study sufficiently blinded outcome assessors. All other domains were of varying degrees of risk of bias. The quality of evidence was downgraded for lack of blinding in studies and other limitations in study designs, inconsistency, or imprecision of effect estimates.

Authors' conclusions

Continuous support during labour may improve outcomes for women and infants, including increased spontaneous vaginal birth, shorter duration of labour, and decreased caesarean birth, instrumental vaginal birth, use of any analgesia, use of regional analgesia, low five‐minute Apgar score and negative feelings about childbirth experiences. We found no evidence of harms of continuous labour support. Subgroup analyses should be interpreted with caution, and considered as exploratory and hypothesis‐generating, but evidence suggests continuous support with certain provider characteristics, in settings where epidural analgesia was not routinely available, in settings where women were not permitted to have companions of their choosing in labour, and in middle‐income country settings, may have a favourable impact on outcomes such as caesarean birth. Future research on continuous support during labour could focus on longer‐term outcomes (breastfeeding, mother‐infant interactions, postpartum depression, self‐esteem, difficulty mothering) and include more woman‐centred outcomes in low‐income settings.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Delivery, Obstetric; Labor, Obstetric; Personal Autonomy; Cesarean Section; Doulas; Pregnancy Outcome; Professional-Patient Relations

Plain language summary

Continuous support for women during childbirth

What is the issue?

In the past, women have been cared for and supported by other women during labour and birth, and have had someone with them throughout, which we call ‘continuous support’. However, in many countries more women are giving birth in hospital rather than at home. This has meant continuous support during labour has become the exception rather than the norm. The aim of this Cochrane Review was to understand the effect of continuous support on a woman during labour and childbirth, and on her baby. We collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question (search date: October 2016).

Why is this important?

Research shows that women value and benefit from the presence of a support person during labour and childbirth. This support may include emotional support (continuous presence, reassurance and praise) and information about labour progress. It may also include advice about coping techniques, comfort measures (comforting touch, massage, warm baths/showers, encouraging mobility, promoting adequate fluid intake and output) and speaking up when needed on behalf of the woman. Lack of continuous support during childbirth has led to concerns that the experience of labour and birth may have become dehumanised.

Modern obstetric care frequently means women are required to experience institutional routines. These may have adverse effects on the quality, outcomes and experience of care during labour and childbirth. Supportive care during labour may enhance physiological labour processes, as well as women's feelings of control and confidence in their own strength and ability to give birth. This may reduce the need for obstetric intervention and also improve women's experiences.

What evidence did we find?

We found 26 studies that provided data from 17 countries, involving more than 15,000 women in a wide range of settings and circumstances. The continuous support was provided either by hospital staff (such as nurses or midwives), or women who were not hospital employees and had no personal relationship to the labouring woman (such as doulas or women who were provided with a modest amount of guidance on providing support). In other cases, the support came from companions of the woman's choice from her own network (such as her partner, mother, or friend).

Women who received continuous labour support may be more likely to give birth 'spontaneously', i.e. give birth vaginally with neither ventouse nor forceps nor caesarean. In addition, women may be less likely to use pain medications or to have a caesarean birth, and may be more likely to be satisfied and have shorter labours. Postpartum depression could be lower in women who were supported in labour, but we cannot be sure of this due to the studies being difficult to compare (they were in different settings, with different people giving support). The babies of women who received continuous support may be less likely to have low five‐minute Apgar scores (the score used when babies’ health and well‐being are assessed at birth and shortly afterwards). We did not find any difference in the numbers of babies admitted to special care, and there was no difference found in whether the babies were breastfed at age eight weeks. No adverse effects of support were identified. Overall, the quality of the evidence was all low due to limitations in study design and differences between studies.

What does this mean?

Continuous support in labour may improve a number of outcomes for both mother and baby, and no adverse outcomes have been identified. Continuous support from a person who is present solely to provide support, is not a member of the woman's own network, is experienced in providing labour support, and has at least a modest amount of training (such as a doula), appears beneficial. In comparison with having no companion during labour, support from a chosen family member or friend appears to increase women's satisfaction with their experience. Future research should explore how continuous support can be best provided in different contexts.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Continuous support compared to usual care (all trials) for women during childbirth.

| Continuous support compared to usual care (all trials) for women during childbirth | ||||||

| Patient or population: women during childbirth Setting: Hospital settings in Australia, Belgium, Botswana, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Finland, France, Greece, Guatamala, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey, USA Intervention: continuous support Comparison: usual care (all trials) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with usual care (all trials) | Risk with Continuous support | |||||

| Spontaneous vaginal birth | Study population | Average RR 1.08 (1.04 to 1.12) | 14369 (21 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 679 per 1000 | 733 per 1000 (706 to 760) | |||||

| Negative rating of/negative feelings about birth experience | Study population | Average RR 0.69 (0.59 to 0.79) | 11133 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 177 per 1000 | 122 per 1000 (104 to 140) | |||||

| Postpartum depression | Study population | ‐ | 5716 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | Both trials (Hodnett 2002; Hofmeyr 1991) were widely disparate in populations, the hospital conditions where they were conducted, and the type of support provider. We concluded that combining the trials data would not yield meaningful information. In both trials the direction of effect was the same. Hodnett 2002 used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Inventory and reported the frequencies of scores greater than 12. Hofmeyr 1991 used the Pitt Depression Inventory and reported scores indicating mild (less than 20), moderate (20 to 34), and severe (> 34) depressive symptomatology. We combined the frequencies of moderate and severe depressive symptomatology, since Pitt scores > 19 have been considered indicative of postpartum depression (Avan 2010). Continuous support resulted in a large reduction in depressive symptomology in Hofmeyr 1991 (RR 0.18, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.36). There was little or no difference in depressive symptomatology in Hodnett 2002 (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.02) |

|

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Admission to special care nursery | Study population | Average RR 0.97 (0.76 to 1.25) | 8897 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 4 5 | ||

| 81 per 1000 | 79 per 1000 (62 to 101) | |||||

| Exclusive or any breastfeeding at any time point, as defined by trial authors | Study population | Average RR 1.05 (0.96 to 1.16) | 5584 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 6 | ||

| 601 per 1000 | 631 per 1000 (577 to 697) | |||||

| Labour length | The mean length of labour in the usual care group ranged from 5.3 to 12.7 hours. | The mean length of labour in the continuous support group was on average 0.69 hours (1.04 to 0.34 hours) shorter |

5429 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| Caesarean birth | Study population | Average RR 0.75 (0.64 to 0.88) | 15347 (24 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 7 | ||

| 146 per 1000 | 109 per 1000 (93 to 128) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Most studies contributing data had design limitations. (‐1)

2 Statistical heterogeneity (I² > 60%). Variation in size of effect. (‐1)

3 The two trials were widely disparate in populations, the hospital conditions within which they were conducted, and the type of support provider. (‐1)

4 Most studies contributing data had design limitations and two studies contributing 37.6% weight had serious design limitations. (‐1)

5 Wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect. (‐1)

6 Statistical heterogeneity (I² > 60%). Variation in direction of effect. (‐1)

7 Heterogeneity I² = 58%. Variation in effect size. (‐1)

Background

This is an update of a review last published in 2013 (Hodnett 2013).

Description of the condition

Historically and cross‐culturally, women have been attended and supported by other women during labour and birth. However, since the middle of the twentieth century, in many countries most women gave birth in hospital rather than at home, and continuous support during labour has become the exception rather than the routine. Concerns about dehumanisation of women's birth experiences (in high‐, middle‐, and low‐income countries) have led to calls for a return to continuous, one‐to‐one support by women for women during labour (Klaus 2002). Research has demonstrated that women benefit from and value the presence of a support person during labour, to provide psychological, physical, emotional, informational and practical support (Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015). This support person may act as an advocate for the woman, for example by helping to communicate her preferences to a health worker, and also provides encouragement, reassurance, and physical comfort. A support person may also help to communicate to the woman about her progress through labour, suggest coping techniques, and support her decision‐making. Two World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines recommend a companion of the woman's choice during labour and childbirth, to improve labour outcomes and women's satisfaction with services (World Health Organization 2015; World Health Organization 2016).

Description of the intervention

Common elements of continuous support during childbirth include emotional support (e.g. continuous presence, reassurance and praise), information about labour progress and advice regarding coping techniques, comfort measures (e.g. comforting touch, massage, warm baths/showers, encouraging mobility, promoting adequate fluid intake and output) and advocacy (e.g. helping the woman to articulate her wishes to others). The period of support for this intervention varies greatly across studies and contexts. For example, some doula programs may initiate support during the pregnancy, provide continuous support during labour and childbirth, and provide support through three months postpartum. Other programs focus specifically on facility‐based care, and continuous support is provided from around the time of admission through the birth. Definitions for what constitutes "continuous" support vary across trials and contexts. For example, "continuous" is defined as "no interruption" (Langer 1998), "minimum of 80% of the time" (Hodnett 2002), and "as continuously as possible" (Hofmeyr 1991) across three large trials in this review.

For the purposes of this review, we have defined continuous support as some combination of comfort measures, emotional support, provision of information, and advocacy on behalf of the woman, provided from at least early labour (before 6 cm dilation) or within one hour of hospital admission (for admission with greater than or equal to 6 cm dilation), through until at least the birth, and provided by a person whose sole responsibility is to provide support to the woman, as continuously as practical in a given context.

How the intervention might work

Two complementary theoretical explanations have been offered for the effects of labour support on childbirth outcomes. Both explanations hypothesise that labour support enhances labour physiology and mothers' feelings of control and competence, reducing reliance on medical interventions. The first theoretical explanation considers possible mechanisms when companionship during labour is used in stressful, threatening and disempowering clinical birth environments (Hofmeyr 1991). During labour, women may be uniquely vulnerable to environmental influences; modern obstetric care frequently subjects women to institutional routines, high rates of intervention, unfamiliar personnel, lack of privacy and other conditions that may be experienced as harsh. These conditions may have an adverse effect on the progress of labour and on the development of feelings of competence and confidence; this may in turn impair adjustment to parenthood and establishment of breastfeeding, and increase the risk of postpartum depression. The provision of support and companionship during labour may to some extent buffer such stressors.

The second theoretical explanation does not focus on a particular type of birth environment. Rather, it describes two pathways ‐ enhanced passage of the fetus through the pelvis and soft tissues, as well as decreased stress response ‐ by which labour support may reduce the likelihood of operative birth and subsequent complications, and enhance women's feelings of control and satisfaction with their childbirth experiences (Hodnett 2002a). Enhanced fetopelvic relationships may be accomplished by encouraging mobility and effective use of gravity, supporting women to assume their preferred positions and recommending specific positions for specific situations. Studies of the relationships among fear and anxiety, the stress response and pregnancy complications have shown that anxiety during labour is associated with high levels of the stress hormone epinephrine in the blood, which may in turn lead to abnormal fetal heart rate patterns in labour, decreased uterine contractility, a longer active labour phase with regular well‐established contractions and low Apgar scores (Lederman 1978; Lederman 1981). Furthermore, individual interventions (e.g. labour induction, epidural anaesthesia, caesarean birth) and a cascade of interventions throughout labour may disrupt hormonal physiology and introduce risks to the woman or her baby, both in the short and long term (Buckley 2015). Emotional support, information and advice, comfort measures and advocacy may reduce anxiety and fear and associated adverse effects during labour.

Continuous support has been viewed by some as a form of pain relief, specifically, as an alternative to epidural analgesia (Dickinson 2002), because of concerns about the deleterious effects of epidural analgesia, including on labour progress (Anim‐Somuah 2011). Many labour and birth interventions routinely involve, or increase the likelihood of, co‐interventions to monitor, prevent or treat adverse effects, in a "cascade of interventions". Continuous, one‐to‐one support has the potential to limit this cascade and therefore, to have a broad range of different effects, in comparison to usual care. For example, if continuous support leads to reduced use of epidural analgesia, it may in turn involve less use of electronic fetal monitoring, intravenous drips, synthetic oxytocin, drugs to combat hypotension, bladder catheterisation, vacuum extraction or forceps, episiotomy and less morbidity associated with these, and may increase mobility during labour and spontaneous birth (Caton 2002; Anim‐Somuah 2011) and impact the experience of giving birth.

Why it is important to do this review

A systematic review examining factors associated with women's satisfaction with the childbirth experience suggests that continuous support can make a substantial contribution to women's satisfaction. When women evaluate their experience, four factors predominate: the amount of support from caregivers, the quality of relationships with caregivers, being involved with decision‐making and having high expectations or having experiences that exceed expectations (Hodnett 2002a).

Clarification of the effects of continuous support during labour, overall and within specific circumstances, is important in light of public and social policies and programs that encourage this type of care. For example, the Congress in Uruguay passed a law in 2001 decreeing that all women have the right to companionship during labour. In several low‐ and middle‐income countries (including China, South Africa, Tanzania and Zimbabwe), the Better Births Initiative promotes labour companionship as a core element of care for improving maternal and infant health (World Health Organization 2016a). In many low‐income countries, women are not permitted to have anyone with them during labour and birth. Efforts to change policies in these settings have led to questions about the effectiveness of support from spouses/partners or other support people of the woman's own choosing, particularly in settings where the cost of paid companions (e.g. doulas) would be prohibitive.

In North America, and increasingly in many other areas of the world, the services of women with special training in labour support have become available. Most commonly known as doula (a Greek word for 'handmaiden'), this new member of the caregiver team may also be called a labour companion, birth companion, labour support specialist, labour assistant or birth assistant. A number of North American organisations offer doula training, certification and professional support; according to one estimate more than 50,000 people have received this training to date (P Simkin, personal communication). Some North American hospitals have begun to sponsor doula services. In a recent national survey of childbearing women in the United States, 6% of respondents indicated that they had used doula services during their most recent labours (Declercq 2013). Many associations for doulas have been established in high‐income countries, including DONA International, Doula UK, NCT Doula, British Doula, Childbirth International, Australian Doulas, Australian Doula College and Europoean Doula Network, among others. Doula services are usually paid for out‐of‐pocket, and therefore affordable to affluent, higher‐educated women only. However, a meta‐analysis conducted by Zhang 1996a showed that socially disadvantaged populations, such as low‐income women, could benefit more from doula support. Maternal healthcare systems in dozens of high‐ and low‐ to middle‐income countries throughout the world are developing new traditions for supportive female companionship during labour (Pascali‐Bonaro 2010).

Questions have arisen about the ability of employees (such as nurses or midwives) to provide effective labour support, in the context of modern institutional birth environments (Hodnett 1997). For example, nurses and midwives often have simultaneous responsibility for more than one labouring woman, spend a large proportion of time managing technology and keeping records, ensure adherence to institutional practices and protocols, and begin or end work shifts in the middle of women's labours. They may work in short‐staffed environments or lack labour support skills.

Companions chosen by a woman from her own network, such as spouses/partners and female relatives, usually have little experience in providing labour support and are often themselves in need of support when with a loved one during labour and birth. As they are frequently available to assume the role, often without extra cost to families or health systems, it is important to understand their effectiveness as providers of continuous labour support.

In addition to questions about the impact of the type of provider of labour support, there are other questions about the effectiveness of support, including its impact under a variety of environmental conditions, and whether its effects are mediated by when continuous support begins (early versus active labour).

There are also questions about the relative impact of different models of labour support; specifically, effects of support provided only during the intrapartum period versus effects of an extended model with support during the antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum periods.

Childbearing women, policy‐makers, payers of health services, health professionals and facilities and those who provide labour support all need evidence about the effects of continuous support, overall and under specific conditions.

Objectives

The primary objective was to assess the effects, on women and their babies, of continuous, one‐to‐one intrapartum support compared with usual care, in any setting. Secondary objectives were to determine whether the effects of continuous support are influenced by the following:

-

Routine practices and policies in the birth environment that may affect a woman's autonomy, freedom of movement and ability to cope with labour, including:

policies about the presence of support people of the woman's own choosing;

epidural analgesia; and

continuous electronic fetal monitoring.

-

The provider's relationship to the woman and to the facility:

staff member of the facility (and thus may have additional loyalties or responsibilities);

not a staff member and not part of the woman's social network (present solely for the purpose of providing continuous support, e.g. a doula); or

a person chosen by the woman from family members and friends.

Timing of onset (early or later in labour).

Model of support (support provided only around the time of childbirth or extended to include support during the antenatal and postpartum periods).

Country income level (high‐income compared to low‐ and middle‐income)

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐RCTs, comparing continuous labour support by either a familiar or unfamiliar person (with or without healthcare professional qualifications) with usual care, in which there was random allocation to treatment and control groups, were considered for inclusion in the review. RCTs published in abstract form only were not eligible for inclusion (unless additional information could be obtained from the authors). Quasi‐RCTs and RCTs using a cross‐over design were not eligible for inclusion in the review.

Types of participants

Pregnant women, in labour.

Types of interventions

We evaluated continuous presence and support during labour and birth. The person providing the support could have qualifications as a healthcare professional (nurse, midwife) or training as a doula or childbirth educator, or be a family member, a spouse/partner, a friend or a stranger with some or no special training in labour support. The control group received usual care, as defined by the trialists. In all cases, 'usual care' did not involve continuous intrapartum support, but it could involve other measures, such as routine epidural analgesia, to help women to cope with labour.

Types of outcome measures

Theoretically, continuous support can have many diverse physiological and psychosocial effects (both short‐ and long‐term), and therefore, a larger than usual number of outcomes were considered.

Primary outcomes

Woman

Spontaneous vaginal birth.

Negative rating of/negative feelings about the birth experience, as defined by trial authors.

Postpartum depression (defined using a pre‐specified cutoff score on a validated instrument).

Baby

Admission to special care nursery.

Exclusive or any breastfeeding at any time point, as defined by trial authors.

Secondary outcomes

Woman

Any analgesia/anaesthesia (pain medication).

Regional analgesia/anaesthesia.

Synthetic oxytocin during labour.

Labour length.

Severe labour pain (postpartum report).

Caesarean birth.

Instrumental vaginal birth.

Perineal trauma (defined as episiotomy or laceration requiring suturing).

Delayed skin‐to‐skin contact (defined as immediately following birth), not pre‐specified.

Delayed initiation of breastfeeding (more than one hour after birth, or as defined by trial authors), not pre‐specified.

Time from birth to initiation of breastfeeding, not pre‐specified.

Unlikely to recommend birth in that institution, not pre‐specified.

Restricted mobility during labour, as defined by trial authors, not pre‐specified.

Baby

Low five‐minute Apgar score (≤7, or as defined by trial authors).

Prolonged newborn hospital stay, as defined by trial authors.

Longer‐term outcomes

Difficulty mothering, as defined by trial authors (including low confidence as mother).

Low self‐esteem in the postpartum period.

Unsatisfactory mother‐infant interactions, not pre‐specified.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (31 October 2016).

The Register is a database containing over 23,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. For full search methods used to populate Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link to the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth in the Cochrane Library and select the ‘Specialized Register ’ section from the options on the left side of the screen.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences; and

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set that has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies; Studies awaiting classification; Ongoing studies).

In addition, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (1 June 2017) for unpublished, planned and ongoing trial reports using the search terms detailed in Appendix 1

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, see Hodnett 2013. For this update, the following methods were used for assessing the 27 reports that were identified as a result of the updated search. The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted another review author.

Data extraction and management

We adapted the recommended Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth data extraction form for this review. For eligible studies, two review authors independently extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted another review author. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we contacted authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third review author.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth); or

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants; and

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation); or

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported); or

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Assessment of the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach

For this update, the quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE handbook to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparison (comparison 1: continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials).

Spontaneous vaginal birth.

Caesarean birth.

Negative rating of/negative feelings about the birth experience, as defined by trial authors.

Postpartum depression, (defined using a pre‐specified cutoff score on a validated instrument).

Admission to special care nursery.

Exclusive or any breastfeeding at any time point, as defined by trial authors.

Labour length.

GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool was used to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) to create ’Summary of findings’ tables. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes was produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

We used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. If trials measured the same outcome but used different methods, we would have used the standardised mean difference.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

Had we found cluster‐randomised trials, we would have included them in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. Our plan was: we would adjust their sample sizes or standard errors using the methods described in the Handbook (Section 16.3.4 or 16.3.6 as appropriate) (Higgins 2011) using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we had used ICCs from other sources, we planned to report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. In future updates of this review, if we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Dealing with missing data

We noted levels of attrition for included studies. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if I² was greater than 30% and either Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (< 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (> 30%), we planned to explore it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where there were 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry was suggested by a visual assessment, we planned to perform exploratory analyses to investigate the source.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged to be sufficiently similar.

If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary is treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials. When we used random‐effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% CIs, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated the source using subgroup analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, we used random‐effects analysis to produce the effect. We added two new subgroup analyses on the model of support received (D) and country income level where trials were conducted (E).

We planned the following subgroup analyses.

(A) Three subgroup analyses that concern characteristics of the childbirth environment

Trials in settings in which women were permitted to be accompanied by one or more support persons of their own choosing compared with trials in which accompaniment was not permitted.

Trials conducted in settings in which epidural analgesia was available compared with trials in settings in which it was unavailable.

Trials in which there was a policy of routine electronic fetal heart rate monitoring compared with trials in settings in which continuous electronic fetal monitoring was not routine.

(B) One subgroup analysis that concerns characteristics of the providers of labour support

Trials in which the caregivers were employees of the institution, compared with trials in which the caregivers were not employees and were not members of the woman's social network, compared with trials in which the providers were not employees and were lay people chosen by the participants (e.g. spouse/partner, friend, close relative).

(C) One subgroup analysis that concerns differences in the timing of onset of continuous support

Trials in which continuous labour support began prior to or during early labour (as defined by trial authors), compared with trials in which continuous support began in active labour.

(D) One subgroup analysis that concerns the model of support received

Trials in which support was provided solely during the intrapartum period, compared with trials in which extended support was provided during the antenatal and postpartum periods, in addition to continuously during the intrapartum period.

(E) One subgroup analysis that concerns the country income level

Trials conducted in high‐income settings, compared with trials conducted in low‐ or middle‐income settings.

The following outcomes were used in subgroup analyses:

spontaneous vaginal birth;

negative ratings of the birth experience;

postpartum depression;

admission to special care nursery;

exclusive or any breastfeeding at any time point, as defined by trial authors;

any analgesia/anaesthesia;

synthetic oxytocin during labour; and

caesarean birth.

The five primary outcomes and three common labour intervention outcomes were used in the subgroup analyses. While normally subgroup analyses are restricted to primary outcomes, we also included the outcome of caesarean birth, because there is widespread concern about escalating caesarean rates worldwide, and subgroup analyses could be helpful to policy makers in decisions about the provision of continuous labour support.

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available in RevMan (RevMan 2014). We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Because few of the trial reports contained all of the information needed for the above subgroup analyses, we contacted the trial authors in an attempt to verify the presence/absence of routine electronic fetal monitoring (EFM), hospital policy regarding the presence of a support person, the presence/absence of epidural analgesia and timing of onset of continuous support. We excluded some studies included in the primary comparisons from the subgroup analyses concerning the use of EFM, presence/absence of epidural analgesia, hospital policy regarding the presence of a support person, because their status was unknown. For tests of differences between these subgroups, we recalculated the overall analysis by including only the studies in which these characteristics were known.

We were unable to carry out subgroup analysis for subgroup (C) timing of onset of continuous support because we could not sufficiently categorise trials according to this subgroup, and in subgroup (D) there were only data for one outcome.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses, for the primary outcomes, in instances where there was a high risk of bias associated with selection bias (allocation concealment). We also performed sensitivity analyses for any outcomes where reciprocal data had to be calculated to include data in an analysis (exclusive breastfeeding; negative rating of/negative feelings about the birth experience).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

In the previous version of this review (Hodnett 2013), 23 trials met the inclusion criteria, but one trial (Thomassen 2003) provided no usable outcome data. Eight trial reports were awaiting further classification and one was ongoing.

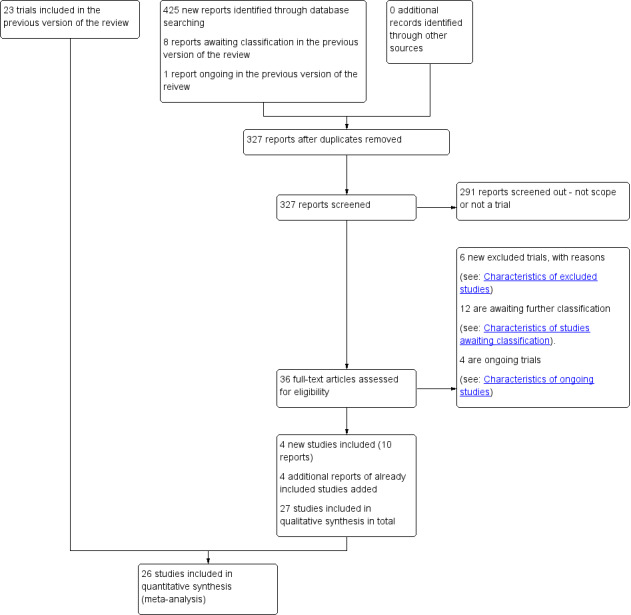

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (31 October 2016), ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (1 June 2017). We assessed 27 new reports and re‐assessed eight that were awaiting classification and one ongoing trial reported in Hodnett 2013 (see Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram

We included four new studies (10 reports) (involving 570 women) (Akbarzadeh 2014; Hans 2013; Isbir 2015; Safarzadeh 2012) and four new reports of four already included studies (Bruggemann 2007; Campbell 2006; Kashanian 2010; Morhason‐Bello 2009). We excluded six studies because: the intervention was not continuous support during labour (Dong 2009; ISRCTN33728802; Orbach‐Zinger 2012; U1111‐1175‐8408; Wan 2011); and participants were not randomly assigned to study groups (Senanayake 2013). Twelve studies are awaiting translation and classification (Aghdam 2015; Bakhshi 2015; Farahani 2005; Huang 2003; IRCT2013111710297N3; McGrath 1999; NCT00664118; Pinheiro 1996; Rahimiyan 2015; Samieizadeh 2011; Sangestani 2013; Shahshahan 2014). Of these studies, five are awaiting translation (Aghdam 2015; Bakhshi 2015; Farahani 2005; Samieizadeh 2011; Sangestani 2013), we are awaiting further information from authors for six (Huang 2003; IRCT2013111710297N3; McGrath 1999; Pinheiro 1996; Rahimiyan 2015; Shahshahan 2014), and were unable to locate contact details for the authors of NCT00664118. Four trials are ongoing (IRCT2015083123837N1; NCT01216098; NCT01947244; NCT02550730).

Included studies

We included a total of 27 studies, and provided full details in the Characteristics of included studies tables. Of these, 26 studies involving 15,858 women contributed data to the analyses for primary and secondary outcomes; one included study (Thomassen 2003) met our inclusion criteria but did not report data on any of our pre‐specified outcomes. Thomassen 2003 is not described in this section, but details are provided in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Methods

We included 27 randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Settings

All 26 trials (n = 15,858) that provided usable outcome data were conducted in hospital settings. The 26 trials were conducted in 17 countries: Australia (Dickinson 2002), Belgium (Bréart ‐ Belgium 1992), Botswana (Madi 1999), Brazil (Bruggemann 2007), Canada (3 studies: Gagnon 1997; Hodnett 1989; Hodnett 2002), Chile (Torres 1999), Finland (2 studies: Hemminki 1990a; Hemminki 1990b), France (Bréart ‐ France 1992), Greece (Bréart ‐ Greece 1992), Guatemala (Klaus 1986), Iran (3 studies: Akbarzadeh 2014; Kashanian 2010; Safarzadeh 2012), Mexico (Langer 1998), Nigeria (Morhason‐Bello 2009), South Africa (Hofmeyr 1991), Thailand (Yuenyong 2012), Turkey (Isbir 2015) and USA (6 studies: Campbell 2006; Cogan 1988; Hans 2013; Hodnett 2002; Kennell 1991; McGrath 2008). The trials were conducted under widely disparate hospital conditions, regulations and routines.

Based on World Bank Development Indicators (World Bank 2017), at the time of study publication: 13 trials were conducted in high‐income settings (Bréart ‐ Belgium 1992; Bréart ‐ France 1992; Campbell 2006; Cogan 1988; Dickinson 2002; Gagnon 1997; Hans 2013; Hemminki 1990a; Hemminki 1990b; Hodnett 1989; Hodnett 2002; Kennell 1991; McGrath 2008), 13 trials were conducted in middle‐income settings (Akbarzadeh 2014; Bréart ‐ Greece 1992; Bruggemann 2007; Hofmeyr 1991; Isbir 2015; Kashanian 2010; Klaus 1986; Langer 1998; Madi 1999; Morhason‐Bello 2009; Safarzadeh 2012; Torres 1999; Yuenyong 2012), and no studies were conducted in low‐income settings. Chile (Torres 1999) and Greece (Bréart ‐ Greece 1992) are classified as high‐income settings in 2017; however, they were classified as middle‐income settings at the time of the study publications and were treated as middle‐income settings in this analysis. Two studies were conducted in lower‐middle income countries (Guatemala (Klaus 1986), and Nigeria (Morhason‐Bello 2009)).

There was remarkable consistency in the descriptions of continuous support across all trials. In most instances the intervention included continuous or nearly continuous presence, at least during active labour. One trial (Hans 2013) was a community doula intervention throughout pregnancy, labour, childbirth and three months postpartum, including continuous support during childbirth. Twenty‐four of the 26 trials that provided usable outcome data (all except Cogan 1988 and Dickinson 2002) also included specific mention of comforting touch and words of praise and encouragement.

Seventeen trials reported funding sources. The majority of these trials were funded by government or charitable grants. One study (Campbell 2006) reported to have received a "small stipend" from Johnson and Johnson to complete data analysis, though authors reported that; "Johnson & Johnson did not influence the design and conduct of the study or the analysis and interpretation of the data". The remaining nine trials (Bréart ‐ Belgium 1992; Bréart ‐ France 1992; Bréart ‐ Greece 1992; Cogan 1988; Isbir 2015; Kashanian 2010; Safarzadeh 2012; Thomassen 2003; Torres 1999) did not clearly report funding sources. Five trials declared no conflicts of interest (Akbarzadeh 2014; Bruggemann 2007; Isbir 2015; Kashanian 2010; Yuenyong 2012); this was not reported in the remaining trials.

Participants

In 20 trials, pregnant women were recruited around the time of admission to the hospital for childbirth or during the active stage of labour; whereas in six trials, women were recruited during antenatal visits, ranging from 12 to 38 weeks (Campbell 2006; Hans 2013; Hodnett 1989; McGrath 2008; Morhason‐Bello 2009; Torres 1999).

Interventions and comparisons

The interventions included continuous presence and support for women during childbirth by a member of hospital staff, a woman in a doula role, or a trained or untrained member of the woman's social network (e.g. spouse or partner, family member, or friend).

In 11 trials (Bréart ‐ Belgium 1992; Bréart ‐ France 1992; Campbell 2006; Cogan 1988; Dickinson 2002; Gagnon 1997; Hemminki 1990a; Hemminki 1990b; Hodnett 1989; Hodnett 2002; McGrath 2008), hospital policy permitted women to be accompanied by their spouses/partners or other family members during labour, while in the other 15 trials, no additional support people were allowed, or it was unclear if other support people were allowed. Epidural analgesia was not routinely available in eight trials (Bréart ‐ Greece 1992; Hofmeyr 1991; Isbir 2015; Kashanian 2010; Klaus 1986; Madi 1999; Morhason‐Bello 2009; Yuenyong 2012). We were unsuccessful in obtaining information about the availability of epidural analgesia in four trials (Akbarzadeh 2014; Cogan 1988, Hans 2013; Safarzadeh 2012). Epidural analgesia was routinely available in the other 14 trials. Electronic fetal heart rate monitoring was not routine in nine trials (Bruggemann 2007; Hofmeyr 1991; Isbir 2015; Kashanian 2010; Klaus 1986; Langer 1998; Madi 1999; Morhason‐Bello 2009; Yuenyong 2012). In nine trials (Campbell 2006; Dickinson 2002; Gagnon 1997; Hemminki 1990a; Hemminki 1990b; Hodnett 1989; Hodnett 2002; Kennell 1991; McGrath 2008) electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) was used routinely. We were unsuccessful in obtaining information about the use of EFM in eight trials (Akbarzadeh 2014; Bréart ‐ Greece 1992; Bréart ‐ Belgium 1992; Bréart ‐ France 1992; Cogan 1988; Hans 2013; Safarzadeh 2012; Torres 1999).

It was not possible to categorise most of the trials according to the pre‐specified subgroups of early versus active labour. In four trials (Cogan 1988; Hodnett 1989; Klaus 1986; Madi 1999), the support began in early labour. In the other 22 trials, the timing of onset of support was much more heterogenous, as were definitions of early and active labour, in instances in which these were defined. Women were in varying phases of labour, from elective induction to active labour.

In addition, the people providing the support intervention varied in their experience, qualifications and relationship to the labouring women. In nine trials (Bréart ‐ Belgium 1992; Bréart ‐ France 1992; Bréart ‐ Greece 1992; Dickinson 2002; Gagnon 1997; Hemminki 1990a; Hemminki 1990b; Hodnett 2002; Kashanian 2010), the support was provided by a member of the hospital staff, for example, a midwife, student midwife or nurse. In 10 trials the providers were not members of the hospital staff and were not part of the woman's social network; they were women with or without special training, such as doulas or women who had given birth before (Akbarzadeh 2014; Hans 2013; Hodnett 1989; Hofmeyr 1991; Isbir 2015; Kennell 1991; Klaus 1986; McGrath 2008); a childbirth educator (Cogan 1988), or retired nurses (Langer 1998). In seven trials they were companions of the woman's choice from her social network, with or without brief training ‐ a female relative or friend or the woman's spouse/partner (Bruggemann 2007; Campbell 2006; Madi 1999; Morhason‐Bello 2009; Safarzadeh 2012; Torres 1999; Yuenyong 2012).

The comparisons were usual care in the same setting. Usual care did not involve continuous support during childbirth, but in some cases included other coping measures, such as routine epidural analgesia.

Excluded studies

We excluded a total of 19 trials (Bender 1968; Bochain 2000; Brown 2007; Dalal 2006; Dong 2009; Gordon 1999; Hemminki 1990c; Lindow 1998; Manning‐Orenstein 1998; Orbach‐Zinger 2012; Ran 2005; Riley 2012; Scott 1999; Senanayake 2013; Sosa 1980; Trueba 2000; Tryon 1966; Wan 2011; Zhang 1996b). Eight trials were excluded as they were not randomised trials (Bender 1968; Dalal 2006; Ran 2005; Scott 1999; Senanayake 2013; Sosa 1980; Trueba 2000; Tryon 1966). Eight trials were excluded because the intervention was not continuous support during childbirth (Bochain 2000; Brown 2007; Dong 2009; Lindow 1998; Manning‐Orenstein 1998; Orbach‐Zinger 2012; Wan 2011; Zhang 1996b). One trial reported as an abstract provided insufficient information to assess eligibility (Riley 2012). Two further trials were excluded because they did not provide any usable data, due to post‐randomisation exclusions (Gordon 1999) and data not separated by treatment group (Hemminki 1990c). Please refer to table Characteristics of excluded studies for details.

Risk of bias in included studies

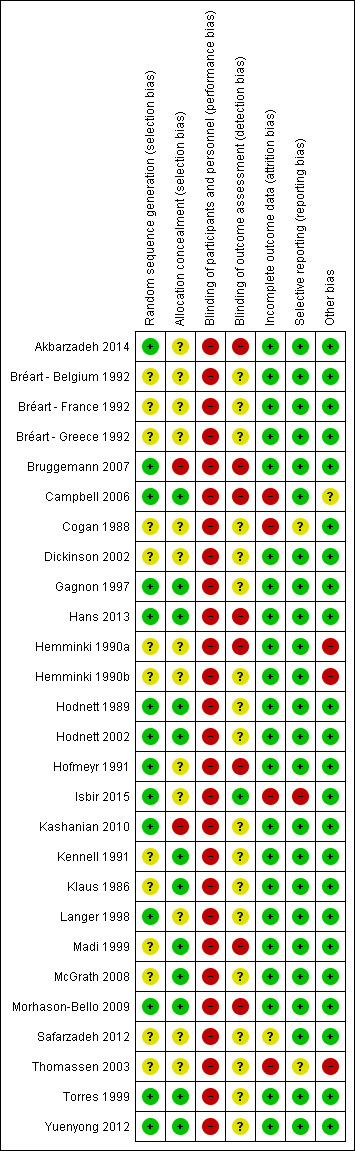

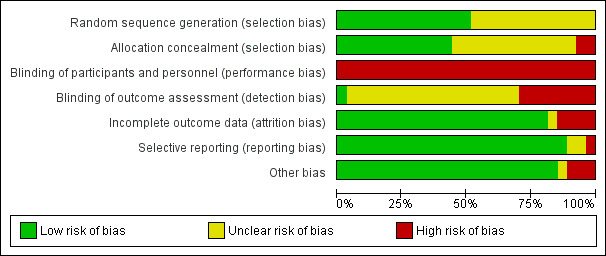

We provided details of the risk of bias in each study in the Characteristics of included studies tables and the methodological quality summary (Figure 2) and methodological quality graph (Figure 3).

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study

3.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies

Allocation

Random sequence generation: 13 trials were at unclear risk of bias (Bréart ‐ Belgium 1992; Bréart ‐ France 1992; Bréart ‐ Greece 1992; Cogan 1988; Dickinson 2002; Hemminki 1990a; Hemminki 1990b; Kennell 1991; Klaus 1986; Madi 1999; McGrath 2008; Safarzadeh 2012; Thomassen 2003) because they did not describe the method of random assignment. Fourteen trials described using a computer random number generator or referred to a random number table (Akbarzadeh 2014; Bruggemann 2007; Campbell 2006; Gagnon 1997; Hans 2013; Hodnett 1989; Hodnett 2002; Hofmeyr 1991; Isbir 2015; Kashanian 2010; Langer 1998; Morhason‐Bello 2009; Torres 1999; Yuenyong 2012) and were assessed as low risk of bias.

Allocation concealment: the risk of selection bias was high in two small trials (Bruggemann 2007; Kashanian 2010). In Bruggemann 2007, women picked their treatment allocation from an opaque container; Kashanian 2010 used block randomisation under which allocation could have been easily predicted. In 12 trials (Campbell 2006; Gagnon 1997; Hans 2013; Hodnett 1989; Hodnett 2002; Kennell 1991; Klaus 1986; Madi 1999; McGrath 2008; Morhason‐Bello 2009; Torres 1999; Yuenyong 2012), risk of selection bias was low with allocation described as either using central allocation, e.g. Hodnett 2002 used a central, computerised randomisation service accessed by telephone or other trials described using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. In the remaining trials (Akbarzadeh 2014; Bréart ‐ Belgium 1992; Bréart ‐ France 1992; Bréart ‐ Greece 1992; Cogan 1988; Dickinson 2002; Hemminki 1990a; Hemminki 1990b; Hofmeyr 1991; Isbir 2015; Langer 1998; Safarzadeh 2012; Thomassen 2003), risk of selection bias was unclear, e.g. one trial used methods that were centrally controlled but not concealed (Cogan 1988).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias): neither those providing nor receiving care could be blinded to the presence/absence of a person providing continuous support. Hodnett 2002 provided evidence to discount contamination and co‐intervention as serious threats to validity. All trials therefore were assessed as having high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): In eight trials group assignment was known and no attempt to blind outcome assessment was apparent. These trials were assessed as being at high risk of bias (Akbarzadeh 2014, Bruggemann 2007; Campbell 2006; Hans 2013; Hemminki 1990a; Hofmeyr 1991; Madi 1999; Morhason‐Bello 2009). One trial was assessed as being at low risk of bias because some blinding of outcome assessment was performed (Isbir 2015). In the remaining 18 trials, risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment was unclear, often because it was not reported who assessed outcomes and whether or not they were blinded (Bréart ‐ Belgium 1992; Bréart ‐ France 1992; Bréart ‐ Greece 1992; Cogan 1988; Dickinson 2002; Gagnon 1997; Hemminki 1990b; Hodnett 1989; Hodnett 2002; Kashanian 2010; Kennell 1991; Klaus 1986; Langer 1998; McGrath 2008; Safarzadeh 2012; Thomassen 2003; Torres 1999; Yuenyong 2012).

Incomplete outcome data

Attrition bias: we did not include data for outcomes assessed in hospital in a comparison if there was more than 20% loss to follow‐up; we did not include longer‐term outcome data if there was more than 25% loss to follow‐up. Based on these criteria, one trial (Thomassen 2003) provided no usable outcome data. Three further trials were assessed as being at high risk of bias for attrition bias (Campbell 2006; Cogan 1988, Isbir 2015). Isbir 2015 had a total of nine post‐randomisation exclusions, due to emergency caesarean sections. One trial (Safarzadeh 2012) had unclear risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

All outcomes appear to have been reported on in most trials. In two trials, it was unclear whether selective reporting had taken place (Cogan 1988; Thomassen 2003). In Cogan 1988 the outcomes had not been specified a priori. In Thomassen 2003 the sample size was based on caesarean section rate, but it is unclear why only emergency caesarean section was reported. One trial (Isbir 2015) had high risk of reporting bias, because women who underwent emergency caesarean section were excluded from the analysis of other outcomes, and caesarean section is a frequently reported outcome for continuous support during childbirth.

Other potential sources of bias

Three trials were assessed as being at high risk of other bias: in two trials the women had been told the purpose of the study differentially (Hemminki 1990a; Hemminki 1990b) and one trial was stopped early for "a range of largely organizational issues" when only a quarter of the original sample size had been enrolled (Thomassen 2003). Risk of bias was unclear in one study (Campbell 2006) and no other sources of bias were apparent in the remaining trials.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Main comparison: continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials

We considered 23 outcomes. Between one and 24 trials contributed to the analysis of each outcome. Sensitivity analyses, conducted by removing the trials (all of which were small) with a high likelihood of selection bias (Bruggemann 2007; Kashanian 2010) did not alter the conclusions. According to our pre‐specified criteria, there was statistical heterogeneity in all but three outcomes (instrumental vaginal birth, low five‐minute Apgar score, and low postpartum self‐esteem). Inspection of the forest plots did not suggest sources of heterogeneity. For the three outcomes postpartum depression, delayed initiation of breastfeeding and difficulty mothering, this statistical heterogeneity confirmed our conclusion that based on clinical heterogeneity a summary statistic would not yield meaningful results (discussed further below). We report the results of fixed‐effect analyses for instrumental vaginal birth, low five‐minute Apgar score, and low postpartum self‐esteem (the latter only contained one trial), and random‐effects analyses for all other outcomes in which summary statistics were computed.

Primary outcomes

Women who had continuous, one‐to‐one support during labour were:

more likely to have

-

a spontaneous vaginal birth (21 trials, 14,369 women, average risk ratio (RR) 1.08, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.04 to 1.12, I² = 61%, Tau² = 0.00, low‐quality evidence), Analysis 1.1;

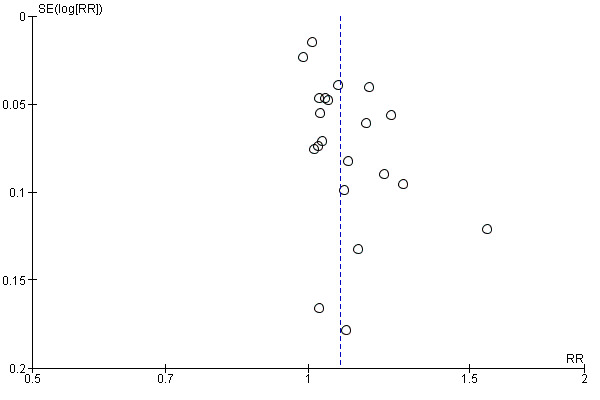

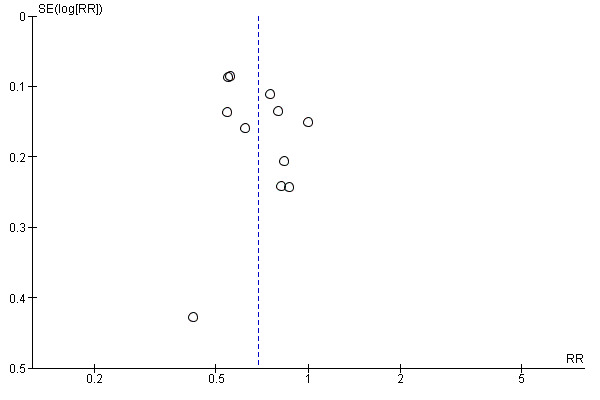

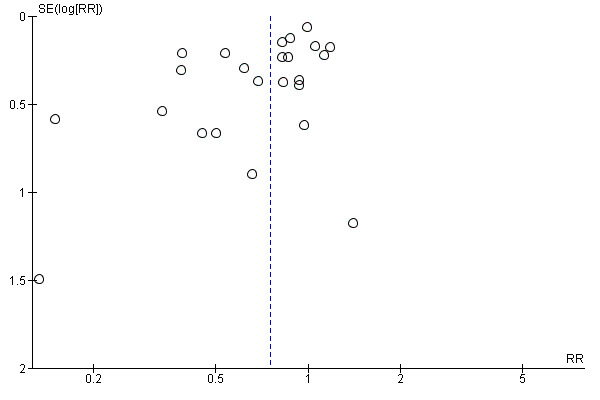

We included 21 studies that reported spontaneous vaginal birth that we assessed for small‐study effect (publication bias). For spontaneous vaginal birth, we observed that most studies clustered around the effect estimate without any obvious asymmetry, indicating a low risk of publication bias (Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, Outcome 1 Spontaneous vaginal birth.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, outcome: 1.1 Spontaneous vaginal birth

less likely to have

-

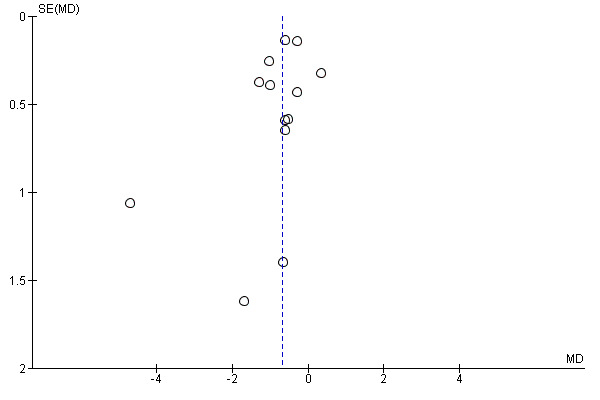

reported negative rating of or negative feelings about childbirth experience (11 trials, 11,133 women, average RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.79, I² = 63%, Tau² = 0.03, low‐quality evidence), Analysis 1.2;

we included 11 studies that reported negative rating of or negative feelings about birth experience that we assessed for small‐study effect (publication bias). For negative rating of or negative feelings about birth experience, we observed that most studies clustered around the effect estimate without any obvious asymmetry, indicating a low risk of publication bias (Figure 5). Two trials reported negative ratings or negative feelings about childbirth experience as satisfaction with care received (Bruggemann 2007) and overall rating of birth experience (Campbell 2006). We acknowledge that this is not ideal, and so carried out a sensitivity analysis to account for this. We removed Bruggemann 2007 and Campbell 2006 from the overall analysis to see if this made any difference to the result. The overall result was unchanged (9 trials, 10,427 women, average RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.84, I² = 62%,Tau² = 0.03).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, Outcome 2 Negative rating of/negative feelings about birth experience.

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, outcome: 1.2 Negative rating of/negative feelings about birth experience

and there was no apparent impact of continuous support on

admission to the special care nursery (7 trials; 8897 infants, average RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.25, I² 37%, Tau² = 0.03, low‐quality evidence), Analysis 1.4; and

-

exclusive or any breastfeeding at any time point, as defined by trial authors (4 trials, 5584 women, average RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.16, I² = 66%, Tau² = 0.01, low‐quality evidence), Analysis 1.5;

trials reported exclusive or any breastfeeding at any time point as: self‐reported breastfeeding duration at one month postpartum (Langer 1998), at six weeks postpartum (Hofmeyr 1991), and at four months postpartum (Hans 2013). Hodnett 2002 reported "not breastfeeding at all" at six weeks postpartum and we calculated the reciprocal for this outcome for this analysis (Analysis 1.5). We acknowledge that this is not ideal, and so carried out a sensitivity analysis to account for this. We removed Hodnett 2002 from the overall analysis to see if this made any difference to the result. The overall result was unchanged (3 trials, 1025 women, average RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.27, I² = 48%,Tau² = 0.01).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, Outcome 4 Admission to special care nursery.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, Outcome 5 Exclusive or any breastfeeding at any time point, as defined by trial authors.

Evidence of postpartum depression was a reported outcome in just two trials (Hodnett 2002; Hofmeyr 1991). Hodnett 2002 used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Inventory and reported the frequencies of scores greater than 12. Hofmeyr 1991 used the Pitt Depression Inventory and reported scores indicating mild (< 20), moderate (20 to 34), and severe (> 34) depressive symptomatology. We combined the frequencies of moderate and severe depressive symptomatology, since Pitt scores greater than 19 have been considered indicative of postpartum depression (Avan 2010). The two trials were widely disparate in populations, the hospital conditions within which they were conducted, and the type of support provider (Hodnett 2002 conducted in 13 tertiary and community hospitals in the USA and Canada, and Hofmeyr 1991 conducted in one community hospital in South Africa). We concluded that combining the studies would not yield meaningful information. In both trials the direction of effect was the same. In Hofmeyr 1991, eight out of 74 women (10.8%) in the group receiving continuous support had depressive symptomatology compared to 44 out of 75 women (58.6%) in the control group (RR 0.18, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.36). In Hodnett 2002, 245 out of 2816 (8.7%) in the supported group had depressive symptomatology, compared to 277 out of 2751 (10.0%) in the control group (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.02; Analysis 1.3, low‐quality evidence).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, Outcome 3 Postpartum depression.

Secondary outcomes

Women who had continuous, one‐to‐one support during labour were:

more likely to have

-

shorter labours (13 trials, 5429 women, mean difference (MD) ‐0.69 hours, 95% CI ‐1.04 to ‐0.34, I² = 66%, Tau² = 0.20, low‐quality evidence), Analysis 1.9;

we included 13 studies that reported duration of labour that we assessed for small‐study effect (publication bias). For duration of labour, we observed that most studies clustered around the effect estimate, without any obvious asymmetry, indicating a low risk of publication bias (Figure 6).

shorter time from birth to initiation of breastfeeding (1 trial, 585 women, MD ‐44.60 minutes, 95% CI ‐47.63 to ‐41.57), Analysis 1.16;

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, Outcome 9 Labour length.

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, outcome: 1.9 Labour length

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, Outcome 16 Time from birth to initiation of breastfeeding.

and less likely to have

-

any intrapartum analgesia or anaesthesia (15 trials, 12,433 women, average RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.96, I² = 73%, Tau² = 0.01), Analysis 1.6;

we included 15 studies that reported use of any analgesia or anaesthesia that we assessed for small‐study effect (publication bias). For use of any analgesia or anaesthesia, we observed that most studies fell at the top around the effect estimate without any obvious asymmetry, suggesting a low risk of publication bias (Figure 7).

regional analgesia or anaesthesia (9 trials, 11,444 women, average RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.99, I² = 81%, Tau² = 0.01), Analysis 1.7; the effect should be interpreted with caution because the forest plot suggests that the apparent small effect was caused by a large effect in one study.

-

an instrumental vaginal birth (19 trials, 14,118 women, RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.96), Analysis 1.12;

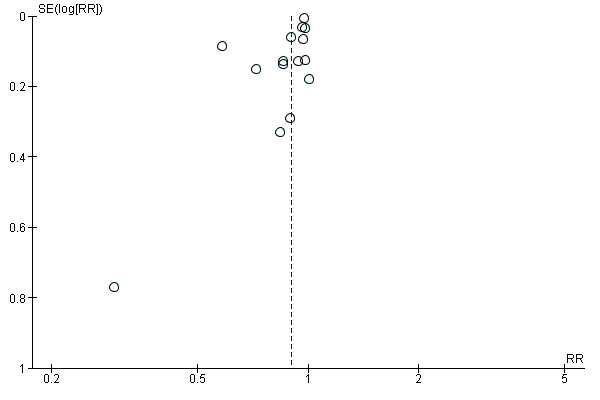

we included 19 studies that reported instrumental vaginal birth that we assessed for small‐study effect (publication bias). For instrumental vaginal birth, we observed that most studies clustered around the effect estimate without any obvious asymmetry, indicating a low risk of publication bias (Figure 8).

-

a caesarean birth (24 trials, 15,347 women, average RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.88, I² = 58%, Tau² = 0.07, low‐quality evidence), Analysis 1.11;

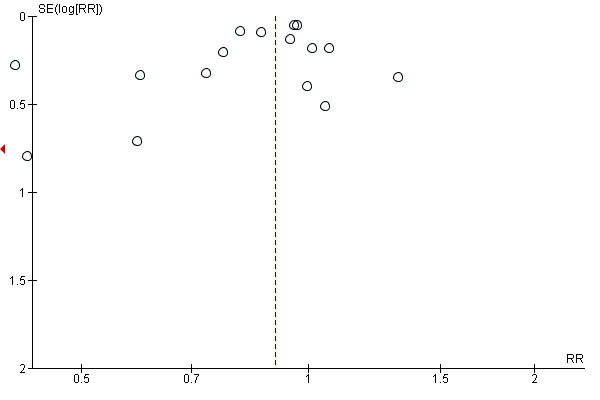

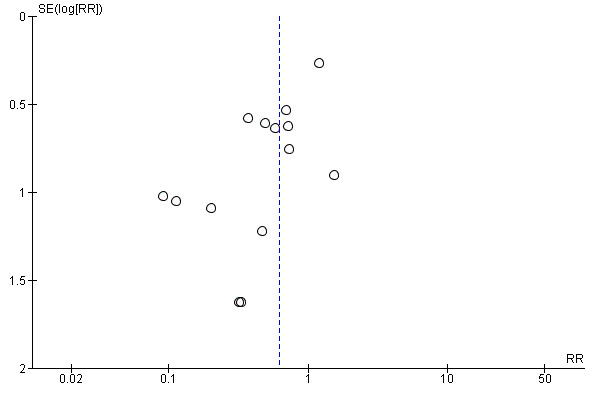

we included 24 studies that reported caesarean birth that we assessed for small‐study effect (publication bias). For caesarean birth, we observed that most studies clustered around the top of the effect estimate without any obvious asymmetry, indicating a low risk of publication bias (Figure 9).

unsatisfactory mother‐infant interactions (defined as not managing well with baby at 8 weeks postpartum, or as defined by trial authors); no trial reported this outcome. Hofmeyr 1991 reported the prevalence of women who self‐reported that they were managing well with their baby at six weeks postpartum and this was found to be higher in the continuous support group (149 women, 90.5% in support group versus 65.3% in control group, P < 0.001).

-

a baby with a low five‐minute Apgar score (14 trials, 12,615 infants, RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.85), Analysis 1.18;

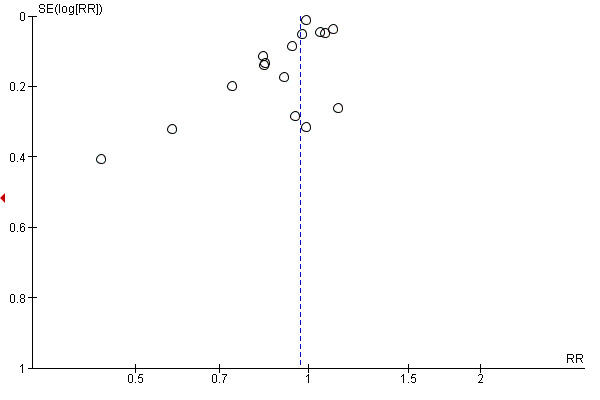

we included 14 studies that reported low five‐minute Apgar score that we assessed for small‐study effect (publication bias). For low five‐minute Apgar score, we observed that most studies clustered around the effect estimate, with a cluster to the left side, indicating a slight risk of publication bias (Figure 10).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, Outcome 6 Any analgesia/anaesthesia.

7.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, outcome: 1.6 Any analgesia/anaesthesia

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, Outcome 7 Regional analgesia/anaesthesia.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, Outcome 12 Instrumental vaginal birth.

8.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, outcome: 1.12 Instrumental vaginal birth

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, Outcome 11 Caesarean birth.

9.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, outcome: 1.11 Caesarean birth

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, Outcome 18 Low 5‐minute Apgar score.

10.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Continuous support versus usual care ‐ all trials, outcome: 1.18 Low 5‐minute Apgar score

and there was no apparent impact of continuous labour support on

the likelihood of serious perineal trauma (4 trials, 8120 women, average RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.01, I² = 44%, Tau² = 0.00), Analysis 1.13;

postpartum report of severe labour pain (4 trials; 2456 women, average RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.21, I² = 78%, Tau² = 0.03), Analysis 1.10;