Abstract

Background

Little is known about the hepatitis C virus (HCV) epidemic among HIV-infected men who have sex with men (HIV+ MSM) in the United States. In this study, we aimed to determine the incidence of primary HCV infection among HIV+ MSM in San Diego, California.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis of HCV infection among HIV+ MSM attending 2 of the largest HIV clinics in San Diego. Incident HCV infection was assessed among HIV+ MSM with a negative anti-HCV test and subsequent HCV test between 2000 and 2017, with data censored to 2015. HCV reinfection was assessed among HIV+ MSM successfully treated for HCV between 2008 and 2015. Infection/reinfection rates were calculated using person-time methods.

Results

Among 3068 initially HCV-seronegative HIV+ MSM, 178 new infections occurred over 15 796 person-years, giving an incidence of 1.13 per 100 person-years (/100py; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.97–1.31). Incidence was stable from 2000 to 2014 (0.83/100py; 95% CI, 0.41–1.48), with an increase to 3.01/100py (95% CI, 1.97–4.42) in 2015 (P = .02). Among 43 successfully treated patients, 3 were reinfected.

Conclusions

HCV incidence is high among HIV+ MSM in San Diego, with evidence suggesting a recent increase in 2015. Strong HCV testing guidelines and active prevention efforts among HIV+ MSM are urgently needed that include rapid diagnosis, treatment, and risk reduction.

Keywords: HCV, HIV, incidence, men who have sex with men

Viral hepatitis was the seventh leading cause of mortality worldwide in 2013, with half of these deaths attributable to hepatitis C virus (HCV) [1]. In response, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued HCV elimination targets, including a 90% reduction in HCV incidence by 2030 [2]. Among HIV-infected individuals, ~2.3 million (6.2%) are coinfected with HCV [3]. These individuals experience accelerated liver disease progression [4] and death [5]; liver-related death is a leading cause of non-AIDS mortality among HIV+ individuals [6, 7].

An epidemic of HCV among HIV-infected men who have sex with men (HIV+ MSM) has been documented in urban centers in the United States, Europe, and Australia [8–13] that is associated with injecting drug use (IDU), but also high-risk sexual practices and substance use associated with sex among those with no history of IDU [8–10, 14]. In Europe, dramatic increases in HCV incidence and prevalence among HIV+ MSM have been documented [10–13, 15, 16], yet data from the Netherlands demonstrating a large reduction in HCV incidence among HIV+ MSM concomitant with widespread scale-up of HCV treatment have renewed optimism that elimination is possible [17]. Additionally, high rates of HCV reinfection have been reported in Europe (5–10 times the primary incidence) [18–20]. No published studies have reported HCV reinfection rates among HIV+ MSM in the United States.

As data on HCV incidence among HIV+ MSM from the United States are limited, it is unclear what level of intervention is required to achieve the WHO elimination targets in this population. San Diego is the eighth largest US city, with ~13 200 HIV-diagnosed individuals [21, 22]. To inform clinical and public health strategies, we aimed to determine HCV primary incidence among HIV+ MSM in San Diego from 2000 to 2015.

METHODS

Study Population

We performed a retrospective cohort study of HIV+ MSM identified at 2 of the largest HIV clinics: (1) the University of California San Diego Owen Clinic (Owen Clinic) and (2) the Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospital in San Diego, California. Together, these clinics care for approximately 3400 HIV+ MSM (~one-third of all HIV-diagnosed MSM in San Diego) [22]. Individuals were included in this study if they were male, HIV-infected, had ever received care at the Owen Clinic or the VA Hospital, and were recorded as having acquired HIV through sex between men. Demographic data on age and ethnicity were collected. This retrospective HCV cohort study was approved by the UCSD Human Research Protection Program and the VA Institutional Review Board.

Primary Incidence Calculation

Primary incident HCV infection was assessed among a subset of HIV+ MSM with a baseline-negative HCV serology and at least 1 more anti-HCV or HCV RNA test during the follow-up period between 2000 and 2017. Results were censored at the end of 2015 to reduce the bias arising from the selection criteria requiring 2 HCV tests, resulting in lower total person-years in 2016 and 2017, given a median testing interval (interquartile range [IQR]) of 1.18 (0.59–2.25) years. Follow-up time was calculated from the baseline negative anti-HCV date to the date of first positive anti-HCV or HCV RNA test, or last negative HCV test. The person-time incidence rate was calculated as the number of incident infections (any positive anti-HCV or HCV RNA test) divided by the number of person-years (py) of follow-up. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated using exact Poisson confidence limits for the estimated rate. As the period between the last negative and first positive test could have been long, a sensitivity analysis was performed calculating the time of infection as the midpoint between the last negative and first positive HCV test. Univariate analysis was performed to compare the incidence rates with the following characteristics (age [≤30, 31–40, 41–50, >50 years], race [white/black/other], Hispanic [yes/no]) using the chi-square test. To evaluate the evolution of incidence over the study period, we calculated the annual incidence rate and assessed statistical differences in incidence over time using a chi-square test for trend in proportions and logistic regression.

Reinfection Incidence Calculation

HCV reinfection was assessed among HIV+ MSM who attended the Owen Clinic and achieved sustained viral response (SVR) with HCV therapy between 2008 and 2014 and had at least 1 subsequent HCV RNA measurement before the end of 2015. No data were available for individuals who attended the VA Hospital. Follow-up time was calculated from the date of HCV SVR documentation until their first subsequent positive HCV RNA or their last HCV test at the Owen Clinic. HCV reinfection was defined as having a new detectable HCV viral load after documented SVR. Most individuals within our analysis were treated with interferon-based regimens; patients who were treated in 2014 received interferon-free direct-acting antiviral (DAA) medications. HCV SVR was defined as having an undetectable HCV viral load after 24 weeks after HCV treatment completion with interferon-based regimens and after 12 weeks in the interferon-free DAA era. The reinfection rate was calculated using person-time methods.

RESULTS

Incidence of Primary HCV Infection

A total of 3068 HIV+ MSM (2652 and 416 from the Owen Clinic and the VA Hospital, respectively) who initially had a negative HCV serology and had at least 1 subsequent HCV test during follow-up (median [IQR], 4.2 [1.7–7.9] years of follow-up) were included in the analysis of primary incidence. Baseline characteristics for both centers are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Their median age (IQR) was 39 (31–46) years. Individuals who attended the VA Hospital were older (median, 42 years and 38 years in VA and Owen, respectively; P < .001), less likely to be of Hispanic ethnicity (11.6% vs 26.1%; P < .001), and more likely to be black (25% vs 9.3%; P < .001).

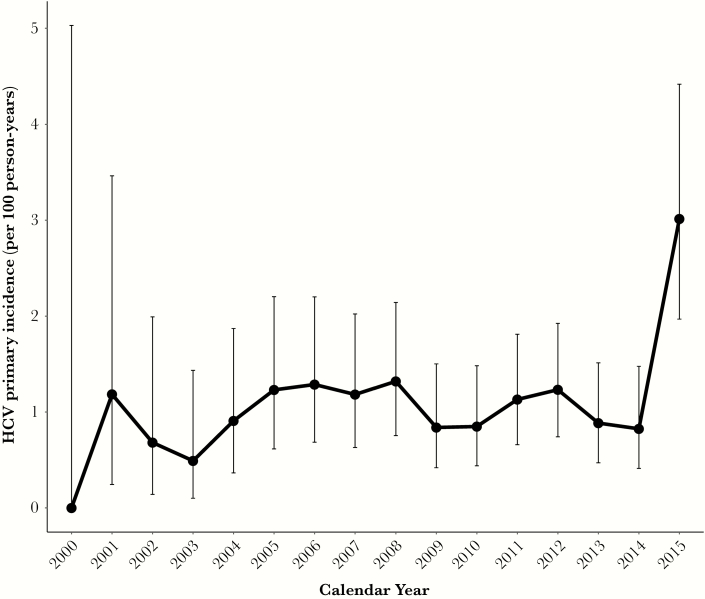

Overall, from 2000 to 2015, 178 new incident HCV infections occurred over 15 796 person-years of follow-up (incidence rate, 1.127/100py; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.967–1.305) with no difference between sites (1.151/100py; 95% CI, 0.977–1.347; and 0.987/100py; 95% CI, 0.626–1.481; at the Owen Clinic and the VA Hospital, respectively) (Table 1). Annual incidence trends are presented in Figure 1. From 2000 to 2014, incidence fluctuated slightly (between 0.49 and 1.32/100py) but there was no evidence of a changing trend in incidence across this time period (P = .92). However, incidence was higher in 2015 (3.01/100py; 95% CI, 1.97–4.42) compared with 2014 (P = .016) and most previous years (Supplementary Table 2)). Indeed, there were 26 incident infections in 2015, compared with only 11 in 2014. Individuals were tested for HCV a median (IQR) of 2 (1–4) times, with a median testing interval (IQR) of 1.18 (0.59–2.24) years. There was a trend toward more frequent testing across the entire period (Supplementary Table 3), with the median testing interval exceeding 2 years in the early 2000s and declining to <1 year in 2014. Annual estimates for HCV incidence from 2000–2015 were similar if assuming the time of infection to be the midpoint between the last negative and first positive HCV tests (overall incidence, 1.14/100py; 95% CI, 0.979–1.321), and an increase in incidence was still observed in 2015 compared with previous periods. No differences in incidence were found by age, race, or ethnicity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Incident Hepatitis C Virus Infection Among HIV-Positive Men who Have Sex With Men in San Diego Stratified by Baseline Demographics

| No. of Events | Person-years | Incidence/100py [95% CI] | IRR (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 178 | 15 796 | 1.127 [0.967–1.305] | - | - |

| Cohort | |||||

| Owen | 155 | 13 466 | 1.151 [0.977–1.347] | 1 | - |

| VA | 23 | 2301 | 0.987 [0.626–1.481] | 0.858 (0.528–1.334) | .493 |

| Age | |||||

| 30 y | 41 | 3382 | 1.212 [0.870–1.645] | 1 | - |

| 31–40 y | 67 | 5719 | 1.171 [0.908–1.488] | 0.966 (0.646–1.462) | .864 |

| 41–50 y | 57 | 4855 | 1.174 [0.889–1.521] | 0.968 (0.637–1.484) | .876 |

| >50 y | 13 | 1840 | 0.707 [0.376–1.208] | 0.583 (0.287–1.109) | .087 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 119 | 9775 | 1.217 [1.008–1.457] | 1 | - |

| Black | 21 | 1816 | 1.157 [0.716–1.768] | 0.950 (0.567–1.519) | .829 |

| Other | 35 | 3779 | 0.926 [0.645–1.288] | 0.761 (0.506–1.117) | .156 |

| Hispanic | |||||

| No | 135 | 11 645 | 1.159 [0.972–1.372] | 1 | - |

| Yes | 43 | 4104 | 1.048 [0.758–1.411] | 0.904 (0.626–1.282) | .565 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IDU, injection drug use; IRR, incidence rate ratio; VA, Veteran Affairs Hospital.

Figure 1.

Incidence of primary hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection over calendar time among HIV-infected men who have sex with men in San Diego. Whiskers present 95% confidence intervals of the point estimate.

Incidence of HCV Reinfection

A total of 43 HIV+ MSM achieved SVR after HCV treatment between 2008 and 2014 at the Owen Clinic and had at least 1 subsequent HCV test before the end of 2015. Among these, 3 became reinfected during 102.5 person-years of follow-up (Table 2), leading to an HCV reinfection rate of 2.89/100py (95% CI, 0.60–8.44). All 3 reinfected individuals had previously been treated with interferon-containing regimens and were initially infected with HCV genotype 1, and all were reinfected with HCV genotype 1a. Reinfections occurred at 2.5, 2.7, and 5.9 years post-SVR. All 3 had at least 1 negative RNA test after SVR and before reinfection. Despite behavioral counseling, at reinfection diagnosis, 2 reported ongoing IDU, and the third reported ongoing unprotected high-risk sexual behaviors such as ongoing condomless anal receptive or insertive intercourse with multiple occasional partners that were engaged through the Internet, potentially under the influence of illicit nonintravenous stimulant use.

Table 2.

Characteristics of HCV Reinfection Among HIV-Infected Men who Have Sex With Men who Attained SVR With HCV Treatment at Owen Clinic

| All Individuals With SVR | Individuals With HCV Reinfection | Individuals Without HCV Reinfection | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 43 | 3 | 40 |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 50 (42–54) | 33 (32–51) | 50 (43–55) |

| Follow-up duration, median (IQR), y | 1.8 (1.1–3.5) | 2.7 (2.5–5.9) | 1.7 (0.9–3.4) |

| HCV genotype, No. (%): | |||

| –1 | 34 (79.0) | 3 (100) | 31 (77.5) |

| –2 | 4 (9.3) | 0 | 4 (10.0) |

| –3 | 4 (9.3) | 0 | 4 (10.0) |

| –4 | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; IQR, interquartile range; SVR, sustained viral response.

Discussion

This study found the incidence of HCV infection among HIV+ MSM in San Diego to be high during 2000–2015, with evidence of a recent increase to 3/100 person-years in 2015.

Our study points to the crucial need for frequent HCV testing among HIV+ MSM. Additionally, our work highlights the importance of developing interventions to prevent HCV infection and reinfection among MSM. Unfortunately, data on behavioral interventions to prevent HCV infection/reinfection among MSM are limited. Methamphetamine or chemsex interventions may be relevant to this population and should be explored [23]. The Swiss HCVree Trial is examining the impact of coupled HCV treatment with behavioral risk reduction among MSM [24]. More studies on these and other interventions are warranted.

Comparison With Other Studies

To our knowledge, we present the largest study of HCV incidence among HIV+ MSM in the United States (>3000 HIV+ MSM) and the only estimate of HCV reinfection in this population. Our overall incidence estimate of 1.13/100py (95% CI, 0.97–1.31) is comparable to estimates among 1171 HIV+ MSM in Boston from 1997–2009 (1.6/100py; 95% CI, 0.97–2.30) [25] and 1184 HIV+ MSM in the multicenter HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS) from 2000–2013 (1% overall, 1.3% in 2011–2013) [26]. However, our primary incidence is higher than the 0.4–0.5/100py incidence reported among the 2041 HIV+ MSM in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) cohort (Baltimore, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Los Angeles) [27] and among the 1830 HIV-infected male participants of the AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG) cohort [28]. These differences may be due, in part, to potential differences in testing. In the MACS and ACTG studies, the mean testing intervals were 2.5–2.8 years, whereas ours was 1.18 years, so our shorter testing interval could have led to earlier detection of infections and therefore a higher incidence rate. Indeed, among a study exploring HCV testing rates among 7 US sites between 2000 and 2011, the UCSD Owen Clinic had one of highest HCV study entry screening rates and the second highest for HCV incidence [29]. Additionally, the MACS and ACTG studies were from earlier time periods, when there was less awareness of the HCV epidemic, so it is possible that more recent estimates from those cohorts could show more frequent testing and higher incidence. Similarly, our result is higher than estimates from case notification data from New York, indicating HCV diagnosis rates among non-IDU HIV+ MSM of 0.6/100py, but the New York rates may underestimate true incidence as they are calculated from notified cases to the state [30] compared with our cohort study. Overall, HCV incidence rates reported among HIV+ MSM were lower than those reported among people who inject drugs (8%–25% per year) [31, 32].

Additionally, our study provides evidence suggestive of an increase in incidence in 2015 among HIV+ MSM in a US setting. Recent data from France indicate an increase in incidence from 2012 to 2015 in HIV+ MSM [16], although there was a dramatic decline between 2014 and 2016 in the Netherlands [17]. Apart from 2015, we found no evidence of changing incidence in previous years from 2000–2014, similar to data from Boston [25], the MACS cohort (among participants in similar entry cohorts) [27], the HOPS cohort [26], and men in the ACTG cohort [28]. It is unclear whether the apparent increase in incidence in 2015 will continue, or if it was a statistical anomaly. This elevation could potentially be due to increases in risk behavior, possibly associated with the availability of highly effective HCV direct-acting antiviral therapies and/or HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) [33]. It is possible that the higher incidence observed in San Diego in 2015 is due to more frequent testing in 2015 (possibly as a result of DAA availability), which could have contributed to an apparent increase in incidence in our study for this year. Enhanced vigilance is needed to monitor HCV incidence and confirm whether the observed increase is sustained and, if so, what prevention efforts are needed to control the epidemic.

Of note, we observed 3 HCV infections among 43 successfully treated HIV+ MSM. All of them were treated with interferon-containing regimens. Our observed reinfection rate is possibly lower than the rates observed in other European studies, but the sample size is too small to draw meaningful conclusions. Retrospective studies in the United Kingdom [19] and the Netherlands [20] showed that HIV+ MSM who cleared HCV infection remain at high risk of reinfection, with an overall rate of 7.8/100py and 15.2/100py, respectively. More recently, a large retrospective analysis of reinfections in HIV+ MSM in 8 centers across Europe found a reinfection rate of 7.3/100py (95% CI, 6.2–8.6) [34]. Additional studies from across the United States examining HCV reinfection, particularly in the DAA era, will allow for a more precise estimate of reinfection in this population. Regardless, the observation of reinfection points toward the importance of frequent retesting post-treatment and the support needed to reduce reinfection risk.

Limitations

Our study was limited by several potential factors. First, as mentioned above, our incidence estimate could be biased by frequency and targeting of HCV testing. If individuals are infrequently tested, this could underestimate HCV incidence. However, individuals at our clinics had an average test interval of 1.1 years, indicating relatively frequent testing among the HIV+ MSM population but many who were tested less frequently than the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for annual testing. Alternatively, if higher-risk (or lower-risk) individuals are tested, this could lead to an overestimation (or underestimation) of HCV incidence. However, within our study, we did not find evidence that individuals were selectively targeted for testing (testing interval was similar between groups). Additionally, our unpublished data indicate an HCV prevalence among newly HIV-diagnosed MSM of 1% in San Diego, which indicates that few HIV+ MSM are infected with HCV before their HIV diagnosis, and therefore that our study is not excluding a potential higher-risk cohort already infected.

Second, we lacked detailed data on sexual risk behaviors among MSM that could be associated with HCV acquisition. Various studies have found associations with fisting [13, 35–37], rectal trauma with bleeding [37], condomless receptive anal intercourse [14, 35, 38], group sex [35, 38], and recreational use of a variety of drugs before or during sexual contact [36], but we did not have data on these behaviors.

Third, our estimate of HCV reinfection was limited by a very small sample size of patients assessed mostly before the interferon-free DAA era. It is possible that the risk of infection/reinfection could decrease due to scale-up of curative treatment and fewer infections or that it could increase due to heightened risk associated with awareness of curative, short-duration, tolerable treatments.

Fourth, our primary incidence analysis relied on evidence of negative HCV antibody at entry and at least 1 more anti-HCV or RNA test, so we may have misclassified some individuals with absent or very delayed seroconversion. Two studies report seroconversion among HIV+ MSM with acute infection. One UK study among 54 HIV+ MSM with acute infection reported that 5% had not seroconverted within 1 year [39]. Among a recent Dutch study of 63 HIV+ MSM with acute HCV infection, 98% had seroconverted within 1 year, and all seroconverted within follow-up [40]. As such, it appears that the vast majority, if not all individuals, achieve seroconversion, but a small proportion (<5%) may require longer than 1 year. It is difficult to predict how very delayed seroconversion would affect our results. In this case, for incident infections occurring during our study, we would have overestimated person-years at risk and therefore underestimated true incidence. On the other hand, incident infections that occurred before cohort entry but resulted in seroconversion during our study would have possibly underestimated true person-years at risk. If some HIV+ MSM never achieve seroconversion, we may have misclassified individuals at risk of infection at cohort entry (leading to overestimation of person-years at risk) and also failed to observe seroconversions during our study (leading to underestimation of incident infections), thus underestimating true incidence. Nevertheless, the impact of this relatively rare phenomenon is likely small and unlikely to change the broad trends observed.

Finally, our analysis was derived from 2 of the largest HIV clinics in San Diego, providing care for approximately one-third of the estimated HIV+ MSM diagnosed in San Diego, with sociodemographic and HIV risk factor charactersitics that mirror the overall distribution of people living with HIV in San Diego County [22]. Therefore, we believe that it is generalizable to San Diego, but it is unclear whether the results of our study are applicable to the wider MSM community elsewhere and whether these trends will persist in the interferon-free DAA era. However, our population under care encompasses a high proportion of vulnerable people with ongoing barriers to care, similar to other large inner-city HIV populations burdened by a high prevalence of HCV coinfection [41]. Notably, although we noted demographic differences between the VA Hospital and the Owen Clinic, we observed a similar incidence of HCV infection, suggesting that risk is likely similar between clinics.

Conclusions

HCV incidence was high and increased in 2015 among HIV+ MSM in San Diego. There is an urgent need for strong testing guidelines in this population and active prevention efforts, including rapid diagnosis and HCV treatment, as well as behavioral risk reduction strategies. Additionally, our work provides the foundation for future analyses assessing what is required to achieve the WHO HCV elimination targets in this population. Recent epidemic modeling has indicated that scaled-up HCV treatment among HIV+ MSM, particularly if combined with behavioral risk reduction, can substantially reduce HCV primary and reinfection incidence among HIV+ MSM in the United Kingdom [15] and Switzerland [42]. Tantalizing real-world evidence from countries with universal health care systems such as the Netherlands indicating a halving in HCV incidence among HIV+ MSM over the 2-year period since widespread DAA expansion provides optimism that treatment scale-up could control the HCV epidemic among MSM [17]. Additional modeling is needed to assess optimal and cost-effective testing and treatment strategies in the MSM population in the United States and to determine what is required for HCV elimination.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christy Anderson for her helpful statistical input.

Financial support. This study was funded by the University of California San Diego Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), a National Institutes of Health (NIH)–funded program (grant number P30 AI036214), the CFAR Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (CNICS; R24 AI067039-01A1), the Pacific AIDS Education and Training Center (PAETC), and NIH grant AI106039. N.K.M. was additionally supported by the National Institute for Drug Abuse (grant number R01 DA037773-01A1). T.C.S.M. is supported by NIH training grant 5T32AI007384-28.

Potential conflicts of interest. N.K.M. has received unrestricted research grants from Gilead unrelated to this work and honoraria from Merck, AbbVie, and Gilead. E.R.C. has received unrestricted research grants from Merck and Gilead unrelated to this work. D.L.W. has received research funding awarded to his institution from AbbVie, Gilead, and Merck and honoraria from AbbVie, Gilead, and Merck. All authors: no reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2016; 388:1081–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2016–2021, Towards Ending Viral Hepatitis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Platt L, Easterbrook P, Gower E, et al. Prevalence and burden of HCV co-infection in people living with HIV: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:797–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thein HH, Yi Q, Dore GJ, Krahn MD. Natural history of hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected individuals and the impact of HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: a meta-analysis. AIDS 2008; 22:1979–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen TY, Ding EL, Seage Iii GR, Kim AY. Meta-analysis: increased mortality associated with hepatitis C in HIV-infected persons is unrelated to HIV disease progression. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:1605–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosenthal E, Roussillon C, Salmon-Ceron D, et al. Liver-related deaths in HIV-infected patients between 1995 and 2010 in France: the Mortavic 2010 study in collaboration with the Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA (ANRS) EN 20 Mortalite 2010 survey. HIV Med 2015; 16:230–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet 2014; 384:241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yaphe S, Bozinoff N, Kyle R, et al. Incidence of acute hepatitis C virus infection among men who have sex with men with and without HIV infection: a systematic review. Sex Transm Infect 2012; 88:558–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bradshaw D, Matthews G, Danta M. Sexually transmitted hepatitis C infection: the new epidemic in MSM? Curr Opin Infect Dis 2013; 26:66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hagan H, Jordan AE, Neurer J, Cleland CM. Incidence of sexually transmitted hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS 2015; 29:2335–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jordan AE, Perlman DC, Neurer J, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among HIV+ men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intern J STD AIDS. 2017; 28:145–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van der Helm JJ, Prins M, del Amo J, et al. The hepatitis C epidemic among HIV-positive MSM: incidence estimates from 1990 to 2007. AIDS 2011; 25:1083–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Urbanus AT, van de Laar TJ, Stolte IG, et al. Hepatitis C virus infections among HIV-infected men who have sex with men: an expanding epidemic. AIDS 2009; 23:F1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus among HIV-infected men who have sex with men—New York City, 2005–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011; 60:945–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martin NK, Thornton A, Hickman M, et al. Can hepatitis C virus (HCV) direct-acting antiviral treatment as prevention reverse the HCV epidemic among men who have sex with men in the United Kingdom? Epidemiological and modeling insights. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:1072–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pradat P, Huleux T, Raffi F, et al. Incidence of new hepatitis C virus infection is still increasing in French MSM living with HIV. AIDS. 2018; 32(8):1077–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boerekamps A, van den Berk GE, Lauw FN, et al. Declining hepatitis C virus (HCV) incidence in Dutch human immunodeficiency virus-positive men who have sex with men after unrestricted access to HCV therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2018; 66:1360–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ingiliz P, Martin TC, Rodger A, et al. ; NEAT Study Group HCV reinfection incidence and spontaneous clearance rates in HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Western Europe. J Hepatol 2017; 66:282–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martin TC, Martin NK, Hickman M, et al. Hepatitis C virus reinfection incidence and treatment outcome among HIV-positive MSM. AIDS 2013; 27:2551–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lambers FA, Prins M, Thomas X, et al. ; MOSAIC (MSM Observational Study of Acute Infection With Hepatitis C) Study Group Alarming incidence of hepatitis C virus re-infection after treatment of sexually acquired acute hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected MSM. AIDS 2011; 25:F21–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and awareness of HIV infection among men who have sex with men—21 cities, United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010; 59:1201–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. County of San Diego Health and Human Services. HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Report. San Diego: County of San Diego; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martin NK, Skaathun B, Vickerman P, Stuart D. Modeling combination HCV prevention among HIV-infected men who have sex with men and people who inject drugs. AIDS Rev 2017; 19:97–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Salazar-Vizcaya L, Kouyos RD, Fehr J, et al. On the potential of a short-term intensive intervention to interrupt HCV transmission in HIV-positive men who have sex with men: a mathematical modelling study. J Viral Hepat. 2018; 25:10–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garg S, Taylor LE, Grasso C, Mayer KH. Prevalent and incident hepatitis C virus infection among HIV-infected men who have sex with men engaged in primary care in a Boston community health center. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56:1480–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Samandari T, Tedaldi E, Armon C, et al. Incidence of hepatitis C virus infection in the human immunodeficiency virus outpatient study cohort, 2000–2013. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4:ofx076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Witt MD, Seaberg EC, Darilay A, et al. Incident hepatitis C virus infection in men who have sex with men: a prospective cohort analysis, 1984–2011. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Taylor LE, Holubar M, Wu K, et al. Incident hepatitis C virus infection among US HIV-infected men enrolled in clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:812–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Freiman JM, Huang W, White LF, et al. Current practices of screening for incident hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among HIV-infected, HCV-uninfected individuals in primary care. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1686–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Breskin A, Drobnik A, Pathela P, et al. Factors associated with hepatitis C infection among HIV-infected men who have sex with men with no reported injection drug use in New York City, 2000–2010. Sex Transm Dis 2015; 42:382–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Page K, Hahn JA, Evans J, et al. Acute hepatitis C virus infection in young adult injection drug users: a prospective study of incident infection, resolution, and reinfection. J Infect Dis 2009; 200:1216–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Garfein RS, Golub ET, Greenberg AE, et al. ; DUIT Study Team A peer-education intervention to reduce injection risk behaviors for HIV and hepatitis C virus infection in young injection drug users. AIDS 2007; 21:1923–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hoornenborg E, Achterbergh RCA, Schim van der Loeff MF, et al. ; Amsterdam PrEP Project Team in the HIV Transmission Elimination AMsterdam Initiative, MOSAIC Study Group MSM starting preexposure prophylaxis are at risk of hepatitis C virus infection. AIDS 2017; 31:1603–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ingiliz P, Martin TC, Rodger A, et al. HCV reinfection incidence and spontaneous clearance rates in HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Western Europe. J Hepatol. 2017; 66:282–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Danta M, Brown D, Bhagani S, et al. ; HIV and Acute HCV (HAAC) Group Recent epidemic of acute hepatitis C virus in HIV-positive men who have sex with men linked to high-risk sexual behaviours. AIDS 2007; 21:983–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Matser A, Vanhommerig J, Schim van der Loeff MF, et al. HIV-infected men who have sex with men who identify themselves as belonging to subcultures are at increased risk for hepatitis C infection. PLoS One 2013; 8:e57740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schmidt AJ, Rockstroh JK, Vogel M, et al. Trouble with bleeding: risk factors for acute hepatitis C among HIV-positive gay men from Germany—a case-control study. PLoS One 2011; 6:e17781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Witt M, Seaberg EC, Darilay A, et al. Incident hepatitis C virus infection in men who have sex with men: a prospective cohort analysis, 1984–2011. Clin Infec Dis 2013; 57:77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thomson EC, Nastouli E, Main J, et al. Delayed anti-HCV antibody response in HIV-positive men acutely infected with HCV. AIDS 2009; 23:89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vanhommerig JW, Thomas XV, van der Meer JT, et al. ; MOSAIC (MSM Observational Study for Acute Infection With Hepatitis C) Study Group Hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody dynamics following acute HCV infection and reinfection among HIV-infected men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1678–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cachay ER, Hill L, Wyles D, et al. The hepatitis C cascade of care among HIV infected patients: a call to address ongoing barriers to care. PLoS One 2014; 9:e102883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Salazar-Vizcaya L, Kouyos RD, Zahnd C, et al. ; Swiss HIV Cohort Study Hepatitis C virus transmission among human immunodeficiency virus-infected men who have sex with men: modeling the effect of behavioral and treatment interventions. Hepatology 2016; 64:1856–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.