Abstract

Background

Urinary incontinence has been shown to affect up to 50% of women. Studies in the USA have shown that up to 80% of these women have an element of stress urinary incontinence. This imposes significant health and economic burden on society and the women affected. Colposuspension and now mid‐urethral slings have been shown to be effective in treating patients with stress incontinence. However, associated adverse events include bladder and bowel injury, groin pain and haematoma formation. This has led to the development of third‐generation single‐incision slings, also referred to as mini‐slings.

It should be noted that TVT‐Secur (Gynecare, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) is one type of single‐incision sling; it has been withdrawn from the market because of poor results. However, it is one of the most widely studied single‐incision slings and was used in several of the trials included in this review. Despite its withdrawal from clinical use, it was decided that data pertaining to this sling should be included in the first iteration of this review, so that level 1a data are available in the literature to confirm its lack of efficacy.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of mini‐sling procedures in women with urodynamic clinical stress or mixed urinary incontinence in terms of improved continence status, quality of life or adverse events.

Search methods

We searched: Cochrane Incontinence Specialised Register (includes: CENTRAL, MEDLINE, MEDLINE In‐Process) (searched 6 February 2013); ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP (searched 20 September 2012); reference lists.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials in women with urodynamic stress incontinence, symptoms of stress incontinence or stress‐predominant mixed urinary incontinence, in which at least one trial arm involves one of the new single‐incision slings. The definition of a single‐incision sling is “a sling that does not involve either a retropubic or transobturator passage of the tape or trocar and involves only a single vaginal incision (i.e. no exit wounds in the groin or lower abdomen).”

Data collection and analysis

Three review authors assessed the methodological quality of potentially eligible trials and independently extracted data from individual trials.

Main results

We identified 31 trials involving 3290 women. Some methodological flaws were observed in some trials; a summary of these is given in the 'Risk of bias in included studies' section.

No studies compared single‐incision slings versus no treatment, conservative treatment, colposuspension, laparoscopic procedures or traditional sub‐urethral slings. No data on the comparison of single‐incision slings versus retropubic mid‐urethral slings (top‐down approach) were available, but the review authors believe this did not affect the overall comparison versus retropubic mid‐urethral slings.

Types of single‐incision slings included in this review: TVT‐Secur (Gynecare); MiniArc (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, USA); Ajust (CR Bard Inc., Covington, USA); Needleless (Mayumana Healthcare, Lisse, The Netherlands); Ophira (Promedon, Cordoba, Argentina); Tissue Fixation System (TFS PTY Ltd, Sydney, Australia) and CureMesh (DMed Co. Inc., Seoul, Korea).

Women were more likely to remain incontinent after surgery with single‐incision slings than with retropubic slings such as tension‐free vaginal tape (TVTTM) (121/292, 41% vs 72/281, 26%; risk ratio (RR) 2.08, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.04 to 4.14). Duration of the operation was slightly shorter for single‐incision slings but with higher risk of de novo urgency (RR 2.39, 95% CI 1.25 to 4.56). Four of five studies in the comparison included TVT‐Secur as the single‐incision sling.

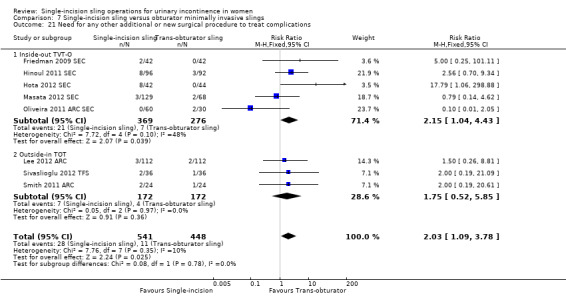

Single‐incision slings resulted in higher incontinence rates compared with inside‐out transobturator slings (30% vs 11%; RR 2.55, 95% CI 1.93 to 3.36). The adverse event profile was significantly worse, specifically consisting of higher risks of vaginal mesh exposure (RR 3.75, 95% CI 1.42 to 9.86), bladder/urethral erosion (RR 17.79, 95% CI 1.06 to 298.88) and operative blood loss (mean difference 18.79, 95% CI 3.70 to 33.88). Postoperative pain was less common with single‐incision slings (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.43), and rates of long‐term pain or discomfort were marginally lower, but the clinical significance of these differences is questionable. Most of these findings were derived from the trials involving TVT‐Secur: Excluding the other trials showed that high risk of incontinence was principally associated with use of this device (RR 2.65, 95% CI 1.98 to 3.54). It has been withdrawn from clinical use.

Evidence was insufficient to reveal a difference in incontinence rates with other single‐incision slings compared with inside‐out or outside‐in transobturator slings. Duration of the operation was marginally shorter for single‐incision slings compared with transobturator slings, but only by approximately two minutes and with significant heterogeneity in the comparison. Risks of postoperative and long‐term groin/thigh pain were slightly lower with single‐incision slings, but overall evidence was insufficient to suggest a significant difference in the adverse event profile for single‐incision slings compared with transobturator slings. Evidence was also insufficient to permit a meaningful sensitivity analysis of the other single‐incision slings compared with transobturator slings, as all confidence intervals were wide. The only significant differences were observed in rates of postoperative and long‐term pain, and in duration of the operation, which marginally favoured single‐incision slings.

Overall results show that TVT‐Secur is considerably inferior to retropubic and inside‐out transobturator slings, but additional evidence is required to allow any reasonable comparison of other single‐incision slings versus transobturator slings.

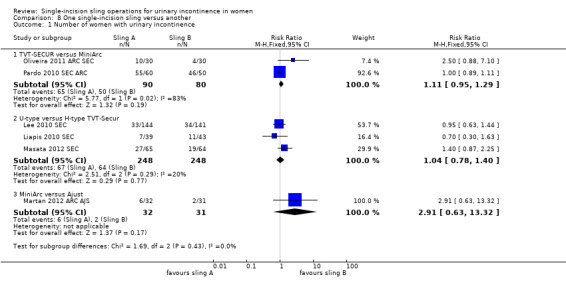

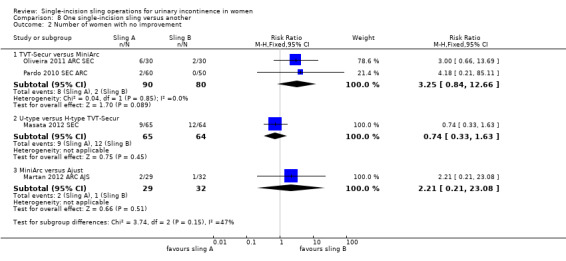

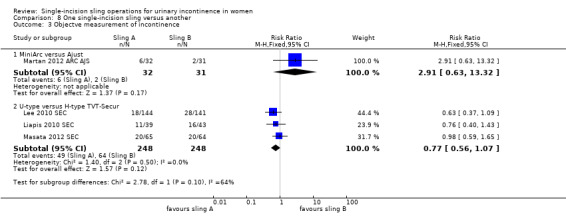

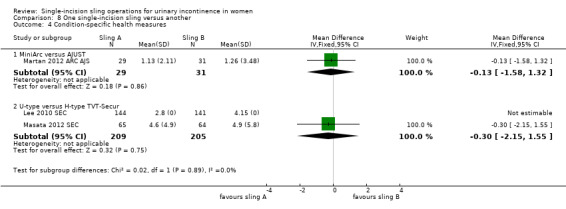

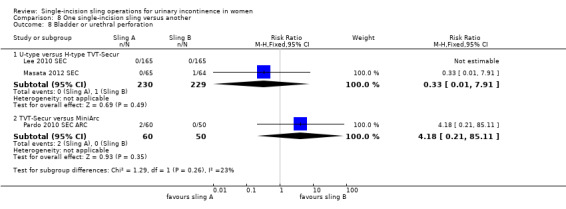

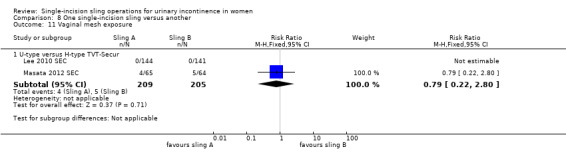

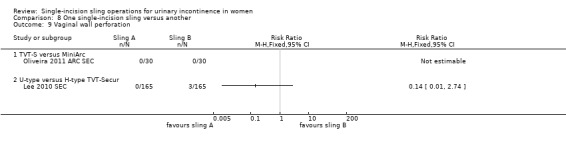

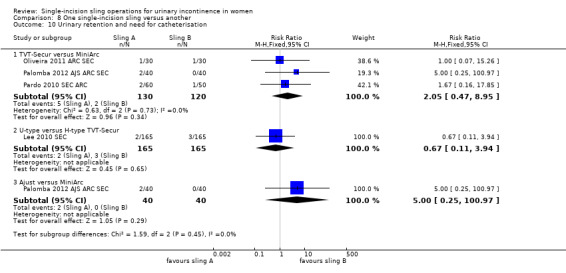

When one single‐incision sling was compared with another, evidence was insufficient to suggest a significant difference between any of the slings in any of the comparisons made.

Authors' conclusions

TVT‐Secur is inferior to standard mid‐urethral slings for the treatment of women with stress incontinence and has already been withdrawn from clinical use. Not enough evidence has been found on other single‐incision slings compared with retropubic or transobturator slings to allow reliable comparisons. A brief economic commentary (BEC) identified two studies which reported no difference in clinical outcomes between single‐incision slings and transobturator mid‐urethral slings, but single‐incision slings may be more cost‐effective than transobturator mid‐urethral slings based on one‐year follow‐up. Additional adequately powered and high‐quality trials with longer‐term follow‐up are required. Trials should clearly describe the fixation mechanism of these single‐incisions slings: It is apparent that, although clubbed together as a single group, a significant difference in fixation mechanisms may influence outcomes.

Plain language summary

Single‐incision sling operations for urinary incontinence in women

Stress urinary incontinence (leakage of urine on effort or exertion, or on coughing, sneezing or laughing) is a common condition that affects up to one in three women worldwide. It is usually the result of weakening of the muscular support of the pipe that conducts urine (urethra), or weakening of the sphincter (circular) muscle at the base of the bladder, which maintains continence. It is more common in women who have had children by vaginal delivery and in those who have weakness in the pelvic floor muscles for other reasons. A significant amount of the woman's and her family's income can be spent on managing the symptoms.

Historically many types of surgery have been performed to treat women with stress urinary incontinence. Over the past 10 years, the accepted standard technique has been the mid‐urethral sling operation, whereby an artificial tape or mesh is placed directly beneath the urethra and is anchored to the tissues in adjacent parts of the groin or just above the pubic bone. Examples of such slings that are commonly used are tension‐free vaginal tape (TVTTM) and transobturator tape (TOT). These operations are usually quite successful, with success rates approaching 80% or 90%. However, they have been shown to result in significant side effects, which can be bothersome and sometimes even dangerous, such as damage to the bladder caused by tape insertion, erosion of the tape into the urethra during the healing period or chronic thigh/groin pain.

In an effort to maintain efficacy while eliminating some of the side effects, a new generation of slings has been developed, called 'single‐incision slings' or 'mini‐slings'; these slings are the subject of this review. They are designed to be shorter (in length) than standard mid‐urethral slings and do not penetrate the tissues as deeply as standard slings. It was therefore thought that they would cause fewer side effects while being no less effective. Examples of single‐incision slings include TVT‐Secur, MiniArc, Ajust and Needleless slings, among others.

We looked for all trials that allocated participants at random to single‐incision slings versus any other treatment for stress incontinence in women, especially comparisons with mid‐urethral slings. We identified a total of 31 trials, involving 3290 women, all of which compared a type of single‐incision sling versus a type of mid‐urethral sling, or different types of single‐incision slings against each other. Overall the quality of the trials was moderate.

We found that subtle differences in the way individual mini‐slings work have sometimes made comparisons difficult. TVT‐Secur is a specific type of mini‐sling that has consistently been shown to provide poorer control of incontinence, along with higher rates of side effects, compared with standard mid‐urethral slings. It has already been withdrawn from clinical use.

In terms of costs, a non‐systematic review of economic studies suggested that single‐incision slings are cheaper than mid‐urethral slings. However, no clear evidence was presented on the differences in costs and effects.

As most trials currently available for inclusion in this review assess TVT‐Secur, trials comparing other single‐incision slings versus standard mid‐urethral slings were too few to allow meaningful comparisons. Some evidence suggests that single‐incision slings were quicker to perform and may cause less postoperative pain, but more trials are needed to adequately assess whether the other types of mini‐slings are in fact as good as or safer than standard mid‐urethral slings.

Background

Urinary incontinence (UI) is an extremely common yet under‐reported, under‐diagnosed, under‐treated and potentially manageable condition that is prevalent throughout the world. It can cause a great deal of distress and embarrassment to individuals, as well as significant financial costs to those individuals and to societies. Estimates of prevalence vary from 10% to 40% depending on the definition and type of incontinence studied, with annual incidence ranging from 2% to 11% (Hunskaar 2002; Milsom 2009). Studies in the USA have shown that up to 80% of women with incontinence have an element of stress urinary incontinence (Hampel 1997). At the turn of the century, Turner estimated that the total annual cost to the United Kingdom National Health Service of treating clinically significant urinary incontinence was GBP 233 million (1999/2000 GDP), with the cost to individuals estimated at an additional GBP 178 million (Turner 2004). In the USA the annual direct costs of urinary incontinence in both men and women is over USD 16 billion (1995 USD) (Chong 2011), with a societal cost of USD 26.2 billion (1995 USD) (Wagner 1998). Approximately USD 13.12 billion (1995 USD) of the total direct costs of urinary incontinence are spent on SUI (Chong 2011; Kunkle 2015). About 70% of this USD 13.12 billion is borne by the patients, mainly through routine care (purchasing pads and disposable underwear (diapers), laundry and dry cleaning). This constitute a significant individual financial burden. Of the remaining 30%, 14% is spent on nursing home admissions, 9% on treatment, 6% on addressing complications and 1% on diagnosis (Chong 2011). Subak 2008 reported that about 1% of the median annual household income (USD 50,000 to USD 59,999) was spent by women on incontinence management. This study estimated that women spent an annual mean cost of USD 751 to USD 1277(2006 USD) on incontinence. This cost increases based on the severity of the symptoms (Subak 2008).The indirect cost associated exerts social and psychological burdens which are unquantifiable. (Chong 2011; Kilonzo 2004). Nevertheless, Birnbaum 2004 estimated that the annual average direct medical costs of SUI for one year (1998 USD) was USD 5642, and USD 4208 for indirect workplace costs.The cost of management and treatment of SUI appears to have increased over time, due to increasing prevalence and increased desire for improved quality of life. This in turn has resulted from improved recognition of the condition, as well as increased use of surgical and non‐surgical managements.

The surgical approach to stress urinary incontinence has progressed rapidly over the past one and a half decades. In the mid‐1990s, a prospective randomised study confirmed the superiority of the colposuspension over the Kelly plication and modified Pereyra needle suspension techniques, with five‐year cure rates in excess of 80% (Bergman 1995). This established the colposuspension as the standard approach to stress incontinence surgery. A colposuspension, however, entails major surgery with substantial operating time and lengthy hospital stay, as well as significant potential for morbidity (Lapitan 2012). The pubovaginal sling, which employs a fascial strip for support, is an effective alternative to the colposuspension, with similar efficacy (Rehman 2011). The incidence of severe adverse events following these procedures is high, for example, 10% after colposuspension (Lapitan 2012) and 13% after pubovaginal slings (Bezerra 2005).

Description of the condition

Classically, UI is subdivided into three main types.

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is characterised by leakage that occurs mainly during 'stress,' which can be brought about by coughing, sneezing, exercise or any manoeuvre that increases intra‐abdominal pressure. SUI is generally due to an anatomical/mechanical abnormality or weakness in the urethra/sphincter/pelvic floor support, and it is commonly treated with an anatomical/mechanical solution (i.e. surgery).

Urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) is characterised by leakage associated with a sense of urgency (defined as a sudden compelling desire to pass urine that cannot be postponed for fear of leakage). UUI is thought to be caused by involuntary detrusor contractions, which may be neurogenic or idiopathic, and it is treated with medication (most commonly anti‐muscarinic drugs), intra‐vesical botulinum toxin injections or, in extreme cases, surgery.

Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) is a combination of stress and urgency incontinence.

Surgical management of SUI or stress‐predominant MUI is most commonly achieved these days by using a mid‐urethral support in the form of a tape or mesh. A great deal of research continues to be conducted to find the best balance of efficacy and minimal adverse events in choosing the right kind of tape.

Women with SUI or stress‐predominant MUI, diagnosed clinically or on urodynamics, have been included in this review.

Description of the intervention

In 1993 Ulmsten and Petros proposed the integral theory, a new concept in the maintenance of female urinary continence (Petros 1993). This is considered to be one of the drivers for the development of “tension‐free vaginal tape” (TVT), which was the first effective minimally invasive procedure for stress incontinence in women (Ulmsten 1998). The five‐year efficacy of TVT has been shown to be comparable with that of the Burch colposuspension, with the added benefits of shorter operating time and decreased hospital stay (Ward 2008).

The major disadvantage of the TVT procedure is that it involves the “blind” passage of a retropubic needle, which poses a significant risk for bladder, bowel and major vessel damage. The incidence of bladder injury is approximately 6% (Ogah 2009). This led to the development of the next generation of sub‐urethral sling procedures with the launch of transobturator tape (TOT) (Delorme 2001). Objective and subjective cure rates for both types of mid‐urethral tape have been shown to be equivalent (Nambiar 2012), but the transobturator passage resulted in fewer injuries to the bladder and other organs. A recent Cochrane review (Ogah 2009) describes lower complication rates with TOT, including less bladder perforation and shorter operating time. The transobturator approach is not without complications, and it has been shown to be associated with significant risk of groin and hip pain following surgery. A meta‐analysis (Latthe 2007) reported an incidence of 12% for groin and hip pain following an obturator‐type sling compared with only 1% for the retropubic approach.

The significant risk of visceral injury associated with the retropubic tape and the high incidence of groin pain following the transobturator route have led to the development of a new generation of stress incontinence devices. Popularly known as the “mini‐slings” (Moore 2009), these third‐generation devices differ from previous sling procedures in that a single incision is made within the vagina with no tape exit incisions. They have also been called single‐incision slings (Molden 2008). The tape used in these devices is significantly shorter (eight to 14 cm) in length than first‐ and second‐generation slings. The insertion pass stops short of the obturator membrane or pelvic floor. This less invasive approach is thought to reduce complications, including bladder/bowel and vascular injury and groin and thigh pain, with a shorter hospital stay and less postoperative pain. Interest is gradually increasing regarding the efficacy and safety of the mini‐slings, but at present, clinical data on these procedures are lacking.

How the intervention might work

Single‐incision slings have been developed that are based on the same mechanistic principles as minimally invasive slings, that is, to restore or enhance the woman's urethral support during a sudden rise in intra‐abdominal pressure, such as during a cough or sneeze, thus preventing involuntary loss of urine. At the same time, they aim to minimise the risk of major side effects associated with minimally invasive slings, such as bladder/vaginal/urethral/vascular perforations or erosions and chronic pain. To try to achieve this, these slings have shorter tape lengths and different fixation systems compared with minimally invasive slings. The main difference in these fixation systems is that they do not penetrate the obturator fossa (hence potentially minimising the risk of groin pain) or the retropubic space (minimising the risk of major vessel or visceral injury).

Currently six minimally invasive sling devices are available, including TVT Secur, MiniArc, Ajust, Needleless, Tissue Fixation System and Ophira. Differences between the various devices include the following.

The TVT‐Secur is inserted with a metal introducer that anchors the device in the obturator membrane. It is placed snugly against the urethra.

The MiniArc has a curved introducer that clips into two plastic anchoring hooks on the ends of the sling; this is used to insert the sling and secure it into the obturator membrane.

The Ajust also has a curved introducer with plastic anchoring hooks, but it differs from the other devices in that it has a pulley‐like system that allows adjustment following insertion.

The Needleless device is 60% longer than the other mini‐slings. It has a pocket‐like fold on each end, and an artery forceps is placed onto the end of the sling in this pouch. The sling is pushed laterally and through the obturator membrane at insertion.

The Ophira mini‐sling is a type 1 polypropylene monofilament mesh with two fixation arms that penetrate the obturator internus muscle on either side with the help of a retractile insertion guide.

The TFS consists of non‐stretch multi‐filament polypropylene tape with two polypropylene soft tissue anchors at either end. The tape is passed in the same direction as standard TVT, but the anchors are embedded into the pubourethral ligament inferior to the pubic symphysis.

CureMesh is a 14‐cm polypropylene mesh similar to the MiniArc sling but manufactured domestically in South Korea.

Why it is important to do this review

Various observational trials have reported cure rates of 77% (Debodinance 2008) and 81% (Meschia 2009) for the TVT‐Secur and 77% for the MiniArc (Gauruder‐Burmester 2009). Preliminary data also suggest lower rates of bladder injury and groin or hip pain following insertion of these devices.

With the introduction of new devices, clinicians have to decide whether they are going to adopt the new technique. Studies of surgical devices can be notoriously difficult to conduct and to report and interpret. It is therefore imperative that a high‐quality review is conducted to pool relevant data from randomised controlled trials to try to answer the question of whether these new single‐incision slings are capable of providing adequate treatment for stress incontinence with a lower rate of side effects compared with currently available standard methods of treatment. This is even more important in the current clinical climate in 2014, when implantable meshes and tapes are under intense scrutiny, both in the media and in clinical circles.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of mini‐sling procedures in women with urodynamic clinical stress or mixed urinary incontinence in terms of improved continence status, quality of life or adverse events.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials in which at least one trial arm involves one of the new single‐incision slings.

Types of participants

Adult women with stress urinary incontinence due to urethral hypermobility or intrinsic sphincter deficiency diagnosed urodynamically (urodynamic stress incontinence (USI)) or clinically (stress urinary incontinence (SUI)). Trials involving women with mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) were also included, if these women were shown to have stress‐predominant symptoms.

Types of interventions

At least one arm of the trial included a single‐incision sling (as defined above) to treat stress or mixed urinary incontinence. The comparison intervention included other surgical techniques and non‐surgical interventions. The definition of a single‐incision sling was “a sling that does not involve either a retropubic or transobturator passage of the tape or trocar and involves only a single vaginal incision (i.e. no exit wounds in the groin or lower abdomen).”

The following comparisons were made.

Single‐incision slings versus no treatment.

Single‐incision slings versus conservative treatment.

Single‐incision slings versus colposuspension.

Single‐incision slings versus laparoscopic procedures.

Single‐incision slings versus traditional sub‐urethral slings.

Single‐incision slings versus retropubic minimally invasive slings (subgrouped: 'bottom‐up' and 'top‐down' approach).

Single‐incision slings versus obturator minimally invasive slings (subgrouped: medial‐to‐lateral 'inside out' approach and lateral‐to‐medial 'outside‐in' approach).

One single‐incision sling versus another.

Comparisons were made on the basis of brand of sling, as significant differences between these products have been noted.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of women who still had urinary incontinence following surgery.

Primary outcomes

Primary effectiveness outcome: number of women with urinary incontinence.

Secondary outcomes

Women’s observations

Number of women with no improvement in urinary incontinence.

Quantification of symptoms

Number of pad changes.

Incontinence episodes.

Pad tests (weights).

Clinicians’ observations

Objective measurement of incontinence (such as observation, leakage observed at urodynamics).

Quality of life

General health status measures (e.g. Short Form 36).

Condition‐specific health measures (specific instruments designed to assess incontinence).

Surgical outcome measures

Duration of the operation.

Operative blood loss.

Duration of inpatient stay.

Time to return to normal activity level.

Adverse events

Major vascular or visceral injury.

Bladder or urethral perforation.

Inadvertent vaginal wall perforation (“button‐holing”).

Urinary retention and need for catheterisation in the short or long term.

Nerve damage.

Other perioperative surgical complications.

Wound dehiscence.

Infection related to use of synthetic mesh.

Erosion to vagina.

Erosion to bladder or urethra.

Long‐term pain/discomfort including pain/discomfort when sitting.

Dyspareunia.

De novo urgency symptoms or urgency incontinence.

(New) detrusor overactivity (urodynamic diagnosis).

Repeat incontinence surgery.

New prolapse surgery.

Need for additional or repeat treatment for incontinence.

Other outcomes

Non‐prespecified outcomes judged important when the review was performed.

Search methods for identification of studies

We imposed no language or other limits on the searches.

Electronic searches

This review drew on the search strategy developed for the Cochrane Incontinence Group. We identified relevant trials from the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Trials Register. For more details on the search methods used to build the Specialised Register, please see the Group's module in The Cochrane Library. This register contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE and MEDLINE in process, and by handsearching of journals and conference proceedings. Most of the trials in the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register are also contained in CENTRAL. The date of the last search was 6 February 2013.

The terms used to search the Incontinence Group Specialised Register are given below.

(({DESIGN.CCT*} OR {DESIGN.RCT*}) AND {INTVENT.SURG.SLINGS.MINISLING*} AND {TOPIC.URINE.INCON*})

(All searches were of the keyword field of Reference Manager 2012.)

Other specific searches in a trials register and a trial portal were performed for this review.

ClinicalTrials.gov (searched 20 September 2012).

World Health Organization (WHO) Internatonal Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (searched 20 September 2012).

The search terms used are given in Appendix 1.

We performed additional searches for the Brief Economic Commentary (BECs). We conducted them in MEDLINE(1 January 1946 to March 2017), Embase (1 January 1980 to 2017 Week 12) and NHS EED (1st Quarter 2016). We ran all searches on 6 April 2017. Details of the searches run and the search terms used can be found in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of all relevant reviews and trial reports were searched to identify further relevant studies.

Data collection and analysis

All data abstraction, synthesis and analysis for this review were conducted in accordance with standard guidelines and criteria of The Cochrane Collaboration. Data abstraction was carried out independently by two review authors and was checked by a third. All three review authors contributed towards the analysis.

Selection of studies

Randomised and quasi‐randomised trials were identified using the above search strategy. Studies were excluded if they were not randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials for women with stress incontinence or stress‐predominant mixed incontinence. All eligible trials were evaluated for appropriateness for inclusion before the results were considered by the three review authors. Excluded studies are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, along with the reasons for their exclusion.

Data extraction and management

Trials were assessed independently by two review authors starting with the titles and gaining further clarity from the abstracts when necessary. Reports of potentially eligible trials were retrieved in full, assessed independently by two review authors and checked by a third. When data may have been collected but not reported, clarification was sought from the trialists when possible. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Data extraction was performed independently by all three review authors; this approach served as a robust cross‐check for errors.

We extracted data independently using a standard form containing prespecified outcomes. Included trial data were processed as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Differences of opinion related to study inclusion, methodological quality or data extraction were resolved by discussion among review authors and, when necessary, were referred to a third party for arbitration.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool was used to examine the following features: sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding and incomplete outcome data. Two review authors assessed risk of bias independently. These assessments are presented in the risk of bias tables, graphs and summary figures.

Measures of treatment effect

We used RevMan software version 5.2.3 to conduct a meta‐analysis when two or more eligible trials were identified. A combined estimate of treatment effect across trials was calculated for each specified outcome. For categorical outcomes, the numbers reporting an outcome were related to the numbers at risk in each group to derive a risk ratio (RR). For continuous variables, means and standard deviations were used to derive a mean difference (MD). When feasible, intention‐to‐treat data were used. If similar outcomes were reported on different scales, we calculated the standard mean difference (SMD). We reversed the direction of effect, if necessary, to ensure consistency across trials.

Data synthesis

We used a fixed‐effect approach to the analysis unless evidence of heterogeneity was noted across trials, in which case a random‐effects model was used.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Differences between trials were investigated when apparent from visual inspection of the results, or when statistically significant heterogeneity was demonstrated by using the Chi2 test at the 10% probability level or assessment of the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). When no obvious reason was noted for heterogeneity to exist (after consideration of populations, interventions, outcomes and settings of the individual trials), or when it persisted despite the removal of trials that were clearly different from the others, we used a random‐effects model.

No subgroup analyses were preplanned, but clinical factors such as symptoms of stress urinary incontinence, urodynamic stress incontinence, mixed urinary incontinence, diagnosis of intrinsic urethral sphincter deficiency or urethral hypermobility, obesity, previous incontinence surgery, presence or absence of prolapse, anaesthesia used or experience of the surgeon might all influence the outcomes of surgery and may be taken into account in future reviews.

Sensitivity analysis

Concomitant stress incontinence with prolapse is a common problem that is frequently corrected simultaneously at surgery; therefore we believed it was important to assess single‐incision slings in this clinically relevant scenario. When appropriate, sensitivity analyses have been conducted, with exclusion of trials in which concomitant surgery was performed.

Timing of outcome measures can vary between trials, and this can serve as a potential source of bias. When comparisons have been made between trials with significantly different mean duration of follow‐up, sensitivity analyses have been performed to assess whether this could be a source of bias.

Results

Description of studies

Trials included in this review have been named in such a way as to make identification and comparisons in tables more intuitive. Trials have been named in the format of <First author surname><Year of publication><Abbreviation of single‐incision sling(s) included in the study>. Abbreviations of single‐incision slings used in this review are as follows.

TVT‐Secur (SEC).

MiniArc (ARC).

Ajust (AJS).

Contasure Needleless (NDL).

Tissue Fixation System (TFS).

Ophira (OPH).

CureMesh (CUR).

For example, Abdelwahab 2010 SEC is a trial report published by Abdelwahab in 2010 including TVT‐Secur as the single‐incision sling intervention; Pardo 2010 SEC ARC included both TVT‐Secur and MiniArc as interventions. This naming system allows easy identification of the types of single‐incision slings used in each study for evaluation of the figures and tables in this review.

Characteristics of the different single‐incision slings

One of the important differences between the different types of single‐incision slings is whether a fixation system, or hook, holds them in place.

Slings that include a fixation system or hook are MiniArc (ARC), CureMesh (CUR), Ajust (AJS), Contasure Needleless (NDL) and Tissue Fixation System (TFS).

Slings that do not include a fixation system or hook are TVT‐Secur (SEC) and Ophira (OPH).

These divisions, however, are subject to further scrutiny because it is difficult to define what is meant by a good 'fixation system.' For example, the Contasure Needleless (NDL) system uses fascial pockets at both ends, in which normal artery forceps are placed to guide the ends of the sling to the obturator tunnel. Technically these pockets act as anchors once the forceps have been removed, but the strength and pull‐out forces could be quite different from those of the tissue fixation system (TFS), which anchors into the pubourethral ligament/muscle complex. Nevertheless, they are regarded as third‐generation sub‐urethral slings, as they do share several common characteristics. The review authors decided that for this iteration of the review, they would be assessed as one group, in line with the protocol.

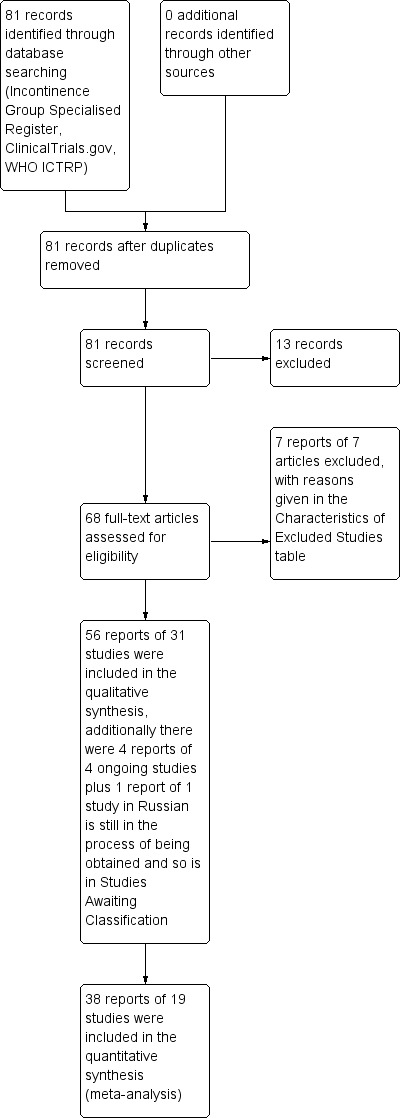

Results of the search

We identified 81 reports of studies from the literature search (Figure 1). We excluded 13, and ongoing studies will be taken into account for future updates (Characteristics of ongoing studies). As the result of overlap between abstracts and published papers, and through separation of single‐centre reports from multi‐centre trials, we finally identified 31 trials that met the inclusion criteria.

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram.

19 full published papers (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC; Amat 2011 NDL; Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Barber 2012 SEC; Basu 2010 ARC; Enzelsberger 2010 ARC; Hinoul 2011 SEC; Hota 2012 SEC; Lee 2010 SEC; Liapis 2010 SEC; Martan 2012 ARC AJS; Masata 2012 SEC; Mostafa 2012 AJS; Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC; Palomba 2012 AJS ARC SEC; Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS; Sottner 2012 ARC AJS; Tommaselli 2010 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC).

One thesis (Mackintosh 2010 AJS).

11 abstracts (Bianchi 2012 SEC; Djehdian 2010 OPH; Friedman 2009 SEC; Kim 2010 SEC; Lee 2010 CUR/SEC; Lee 2012 ARC; Pardo 2010 SEC ARC; Schweitzer 2012 AJS; Seo 2011 SEC; Smith 2011 ARC; Yoon 2011 NDL).

Four ongoing trials were identified (Foote 2012; Maslow 2011; Robert 2012; Rosamilia 2012; Characteristics of ongoing studies). One paper, in Russian, that we are still trying to obtain is listed in Studies awaiting classification (Pushkar 2011).

Included studies

In all, 31 trials met the inclusion criteria. These include 19 fully published papers, one thesis and 11 abstracts. The characteristics of included trials varied considerably and have been described in detail in Characteristics of included studies. A brief descriptive summary follows.

No trials were identified that compared single‐incision slings versus no treatment, conservative treatment, colposuspension, laparoscopic procedures or traditional sub‐urethral slings.

Single‐incision slings versus retropubic mid‐urethral slings

Five trials were identified. These were further sub‐divided on the basis of comparisons with top‐to‐bottom or bottom‐to‐top approaches of retropubic slings; however no trials compared single‐incision slings versus top‐to‐bottom retropubic slings. All five trials were fully published papers and compared single‐incision slings versus bottom‐to‐top retropubic slings (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC; Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Barber 2012 SEC; Basu 2010 ARC; Wang 2011 SEC).

Women with prolapse

One study included women with concomitant prolapse (Barber 2012 SEC) but did not present separate data for participants who underwent sling surgery alone. Two trials were unclear about inclusion of women with associated prolapse (Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC). No other significant difference was noted between participant groups. Methodology was not well described in Abdelwahab 2010 SEC but was adequate in the four other trials.

Single‐incision slings versus transobturator mid‐urethral slings

These trials were further sub‐divided by type of trans‐obturator sling into inside‐out (TVT‐O) and outside‐in (TOT).

Inside‐out slings

Thirteen trials compared single‐incision slings versus inside‐out transobturator slings. Eight were fully published papers (Amat 2011 NDL; Hinoul 2011 SEC; Hota 2012 SEC; Masata 2012 SEC; Mostafa 2012 AJS; Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC; Tommaselli 2010 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC), four were abstracts (Bianchi 2012 SEC; Friedman 2009 SEC; Schweitzer 2012 AJS; Seo 2011 SEC) and one was a thesis (Mackintosh 2010 AJS). Reporting and adequacy of methodology were variable—methodological information in all abstracts was minimal, as it was in Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC, but in Amat 2011 NDL, the randomisation method used was considered inadequate. The other full papers described methodology well.

Women with prolapse

Amat 2011 NDL; Friedman 2009 SEC; and Hota 2012 SEC included participants with associated prolapse who may have had concomitant prolapse surgery. Bianchi 2012 SEC; Hinoul 2011 SEC; Masata 2012 SEC; Mostafa 2012 AJS; Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC; and Tommaselli 2010 SEC excluded patients with associated prolapse. Mackintosh 2010 AJS; Schweitzer 2012 AJS; and Seo 2011 SEC did not specify this in their exclusion criteria.

Outside‐in slings

Seven trials compared single‐incision slings versus outside‐in transobturator slings (TOTs). Only one is a fully published paper (Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS); the others were abstracts (Djehdian 2010 OPH; Enzelsberger 2010 ARC; Kim 2010 SEC; Lee 2012 ARC; Smith 2011 ARC; Yoon 2011 NDL). Enzelsberger 2010 ARC is a German paper that contains an English language abstract with minimal information. A full translation was not obtained, but we will try to request this for future updates. Methodological quality of these trials was variable. In Lee 2012 ARC; Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS; and Smith 2011 ARC,randomisation methods were adequately described, but allocation and blinding were not described. Randomisation was unequal, and the method was not described in Djehdian 2010 OPH, was inadequately performed in Yoon 2011 NDL, and was not clearly described in Kim 2010 SEC.

Prolapse and overactive bladder symptoms

Djehdian 2010 OPH excluded patients with significant genitourinary prolapse, and Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS excluded patients with predominant overactive bladder symptoms, but Enzelsberger 2010 ARC; Kim 2010 SEC; Lee 2012 ARC; Smith 2011 ARC; and Yoon 2011 NDL were unclear about inclusion/exclusion of these patient groups.

One type of single‐incision sling versus another

Nine trials were identified: five full papers (Lee 2010 SEC; Liapis 2010 SEC; Masata 2012 SEC; Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC; Palomba 2012 AJS ARC SEC) and four abstracts (Lee 2010 CUR/SEC; Martan 2012 ARC AJS; Pardo 2010 SEC ARC; Sottner 2012 ARC AJS). Methodological quality was variable even among fully published papers, ranging from inadequate randomisation methods used in Liapis 2010 SEC to overall very robust and well‐reported methodology used in Palomba 2012 AJS ARC SEC. Methodology as reported in the abstracts was generally unclear. Comparisons varied in these trials and have been grouped into three owing to the difference in fixation systems of the different types of single‐incision slings: TVT‐SECUR versus MiniArc, U‐type versus H‐type of TVT‐Secur and MiniArc versus Ajust. The Sottner 2012 ARC AJS paper was published in Czech with an English abstract, but no useful data were available, and no translation was obtained; however, this will be requested for future updates.

Excluded studies

Seven studies were excluded because they were not randomised control trials or because they did not include single‐incision slings as one of the comparators. Four trials were ongoing at the time of writing of this review and therefore were not included in the analysis but may be considered in future updates. One trial is awaiting classification because currently available information is lacking; however, it will be considered in future updates. The details of these studies are given under Characteristics of excluded studies.

Five other studies are awaiting assessment or are ongoing trials; details are given in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and Characteristics of ongoing studies sections.

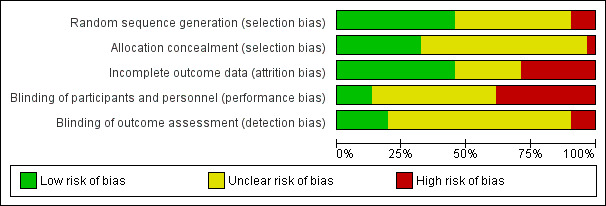

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in included trials was variable, with about half of the trials using adequate methods of randomisation and allocation concealment, while in the other half, methods used were inadequate or were not described. Attempts to double‐blind were even less rigorous, with only five trials carrying out some kind of blinding of participants. Although blinding can be notoriously difficult to achieve in surgical trials, it is nonetheless possible to a reasonable degree; therefore the review authors believed it was warranted to utilise this as a criterion in the risk of bias section. The findings of the risk of bias assessment are summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

The risk of bias was considered to be low for random sequence generation for 14 trials, in which the sequence was generated most often by using a computer (Barber 2012 SEC; Basu 2010 ARC; Hinoul 2011 SEC; Lee 2010 SEC; Lee 2012 ARC; Mackintosh 2010 AJS; Martan 2012 ARC AJS; Masata 2012 SEC; Mostafa 2012 AJS; Palomba 2012 AJS ARC SEC; Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS; Smith 2011 ARC; Tommaselli 2010 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC).

The risk of bias was considered high for three trials, in which allocation was based on medical record number (Amat 2011 NDL), participants were allocated alternately (Liapis 2010 SEC) or the method of randomisation was inadequately described (Pardo 2010 SEC ARC).

The risk of bias was considered unclear in the remaining 14 trials, in which no description was given in the report (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC; Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Bianchi 2012 SEC; Djehdian 2010 OPH; Enzelsberger 2010 ARC; Friedman 2009 SEC; Hota 2012 SEC; Kim 2010 SEC; Kim 2010 SEC; Lee 2010 CUR/SEC; Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC; Schweitzer 2012 AJS; Seo 2011 SEC; Sottner 2012 ARC AJS; Yoon 2011 NDL).

Allocation concealment

Eleven trials used an adequate allocation concealment method (most often opaque envelopes) (Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Barber 2012 SEC; Basu 2010 ARC; Hota 2012 SEC; Lee 2012 ARC; Mackintosh 2010 AJS; Martan 2012 ARC AJS; Masata 2012 SEC; Mostafa 2012 AJS; Palomba 2012 AJS ARC SEC; Wang 2011 SEC).

The other 20 trials failed to describe any method of allocation concealment.

Blinding

Blinding of participants or personnel

Only five trials carried out some kind of blinding of participants. The Barber trial (Barber 2012 SEC) used sham incisions in the mini‐sling arm to facilitate blinding. In the Basu trial (Basu 2010 ARC), participants were blinded but researchers could not be blinded because of differences in devices. The Palomba trial (Palomba 2012 AJS ARC SEC) stated that participants and data assessors were masked to the procedure. The Schweitzer trial (Schweitzer 2012 AJS) reported that women were blinded to the type of procedure by use of a sham incision in the Ajust group. Tommaselli et al (Tommaselli 2010 SEC) reported that participants "were left blinded to the devices used until the end of the procedure." The other trials made no mention of blinding or stated that it was not possible.

Blinding of outcome assessors

Six trials mentioned methods of reducing risk of bias through blinded outcome assessment (Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Barber 2012 SEC; Mackintosh 2010 AJS; Mostafa 2012 AJS; Palomba 2012 AJS ARC SEC; Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS). Three were considered to be at high risk of bias owing to unblinded outcome assessment or inadequate information for assessment (Pardo 2010 SEC ARC; Schweitzer 2012 AJS; Smith 2011 ARC).

Incomplete outcome data

The risk of bias was considered high for eight trials (Amat 2011 NDL; Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Hinoul 2011 SEC; Hota 2012 SEC; Liapis 2010 SEC; Schweitzer 2012 AJS; Smith 2011 ARC; Tommaselli 2010 SEC) as the result of high dropout rates. Of these, differential dropout rates were observed in Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC and Hinoul 2011 SEC. Hota 2012 SEC failed to recruit the required number of participants and was stopped at interim analysis.

Effects of interventions

Single‐incision slings versus no treatment

No trials that compared single‐incision slings versus no treatment were found.

Single‐incision slings versus conservative treatment

No trials that compared single‐incision slings versus conservative treatment were found.

Single‐incision slings versus colposuspension

No trials that compared single‐incision slings versus colposuspension were found.

Single‐incision slings versus laparoscopic procedures

No trials that compared single‐incision slings versus laparoscopic procedures were found.

Single‐incision slings versus traditional sub‐urethral slings

No trials that compared single‐incision slings versus traditional sub‐urethral slings were found.

Single‐incision slings versus retropubic minimally invasive slings (subgrouped: 'bottom‐up' and 'top‐down' approach)

Five trials met the inclusion criteria (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC; Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Barber 2012 SEC; Basu 2010 ARC; Wang 2011 SEC). All single‐incision slings were compared with 'bottom‐up' retropubic minimally invasive slings. All but one trial (Basu 2010 ARC) involved one type of mini‐sling: TVT‐Secur. The study authors note that the Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC study was stopped at interim analysis (two months) because of poor efficacy and complication rates with the TVT‐Secur.

No trials that compared a single‐incision sling versus a 'top‐down' retropubic sling were identified. These types of slings are no longer used in clinical practice, but if we had identified such trials, they would have been included for completeness.

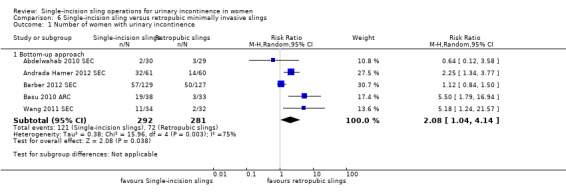

Number of women with urinary incontinence (primary outcome)

All five trials were included in this meta‐analysis. The overall result showed that more women had persistent urinary incontinence after the single‐incision surgery (121/292, 41% vs 72/281, 26%; RR 2.08, 95% CI 1.04 to 4.14; Analysis 6.1), and this was statistically significant in favour of retropubic slings. One trial (Basu 2010 ARC) compared the MiniArc sling against TVT; the other four compared TVT‐Secur against TVT.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 1 Number of women with urinary incontinence.

Statistical heterogeneity is apparent in this meta‐analysis, possibly as a result of the inconclusive results of the small Abdelwahab trial and the larger Barber trial. Clinical heterogeneity may also be a factor: One trial (Barber 2012 SEC) did include women with concomitant prolapse, and almost half of the study population underwent some form of concomitant surgery. Two of the other trials (Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC) were not clear about whether women with concomitant prolapse were included. However, the result remained statistically significant in favour of retropubic tape when a more conservative random‐effects model was used.

Follow‐up ranged from nine months (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC) to three years (Basu 2010 ARC) but was one year for the other three trials (Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Barber 2012 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC). Most trials used a composite measure of cure consisting of subjective and objective measures of incontinence. Although one‐year follow‐up data are reported for the Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC study, it must be noted that only half of the planned number of subjects were recruited because the trial was stopped at interim analysis. Nevertheless, the review authors believed that the reported data should be included in the meta‐analysis.

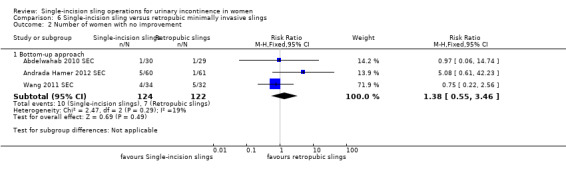

Number of women with no improvement

Three trials were included in the meta‐analysis (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC; Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC). The overall result showed that almost all women had improved, but no statistically significant difference was observed between the two treatments, and the confidence interval was wide (Analysis 6.2).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 2 Number of women with no improvement.

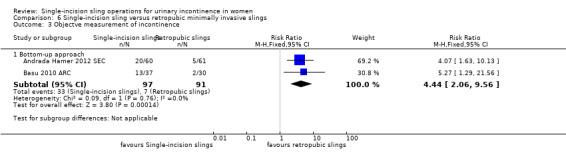

Objective measurement of incontinence

Two trials were included in the meta‐analysis (Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Basu 2010 ARC). The Andrada Hamer trial compared TVT‐Secur against TVT with follow‐up at one year. Investigators performed both cough test and pad test for objective measurement of SUI; we have used the results of the cough test in this analysis. The Basu trial compared the MiniArc against TVT with follow‐up of three years; however urodynamic evaluation of incontinence (the objective measurement criterion used in the trial) was done at six‐month follow‐up, and these data were used in this comparison. The overall result reflected the individual results of the separate trials and was statistically significant favouring retropubic slings (RR 4.44, 95% CI 2.06 to 9.56) (Analysis 6.3).

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 3 Objectve measurement of incontinence.

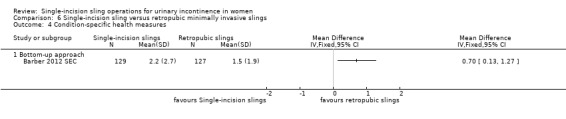

Quality of life

The Barber trial (Barber 2012 SEC) measured condition‐specific quality of life at one year using the Incontinence Severity Index score. Quality of life was statistically significantly better in the retropubic group (Analysis 6.4).

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 4 Condition‐specific health measures.

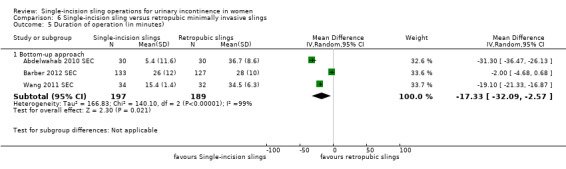

Surgical outcome measures

Duration of operation

Three trials were included in the meta‐analysis (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC; Barber 2012 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC). Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC also provided data for mean duration of operation, but the standard deviation was not given; therefore it could not be included in the meta‐analysis. The duration of the operation was significantly shorter for the single‐incision sling (17 minutes, 95% CI 3 to 32 minutes) (Analysis 6.5). However, statistical heterogeneity may be explained clinically by differences in the definition of what constitutes "duration of operation." Statistical significance persisted when the more conservative random‐effects model was used, and all three trials favoured the single‐incision arm.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 5 Duration of operation (in minutes).

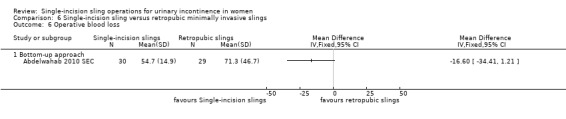

Operative blood loss

Only one study was included in this analysis (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC), but lower blood loss with a single‐incision sling was not statistically significant (Analysis 6.6).

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 6 Operative blood loss.

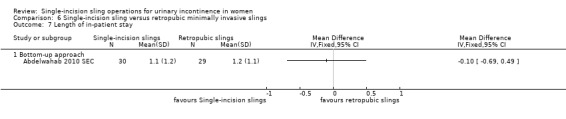

Length of in‐patient stay

One study was included in the analysis (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC), but the results were not statistically significant and the confidence interval was wide (Analysis 6.7).

6.7. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 7 Length of in‐patient stay.

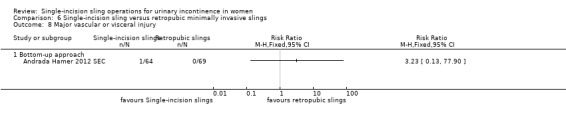

Adverse events

Major vascular or visceral injury; vaginal wall perforation

The small Andrada Hamer trial (Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC) reported that one woman had major vascular or visceral injury (Analysis 6.8), and one in each group had vaginal wall perforation (Analysis 6.9); however, the results were not statistically significant because wide confidence intervals implied lack of evidence in favour of either procedure.

6.8. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 8 Major vascular or visceral injury.

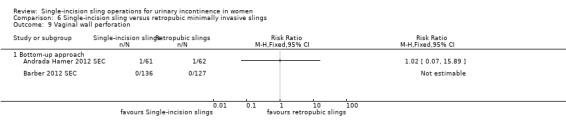

6.9. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 9 Vaginal wall perforation.

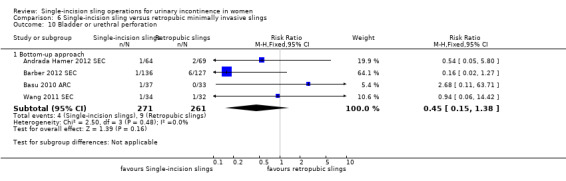

Bladder or urethral perforation

Bladder or urethral perforation was reported in four trials (Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Barber 2012 SEC; Basu 2010 ARC; Wang 2011 SEC) and was not common (<4%). The overall result was not statistically significant and the confidence interval was wide (Analysis 6.10). Apart from the Basu trial (Basu 2010 ARC), which compared the MiniArc with TVT, all other trials used TVT‐Secur as the experimental intervention, but no statistical heterogeneity was evident.

6.10. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 10 Bladder or urethral perforation.

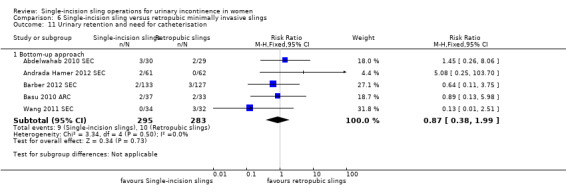

Urinary retention and the need for catheterisation

Five trials reported on this outcome (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC; Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Barber 2012 SEC; Basu 2010 ARC; Wang 2011 SEC). Less than 4% of women experienced difficulty voiding; the difference between groups was not statistically significant and the confidence interval was wide (Analysis 6.11).

6.11. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 11 Urinary retention and need for catheterisation.

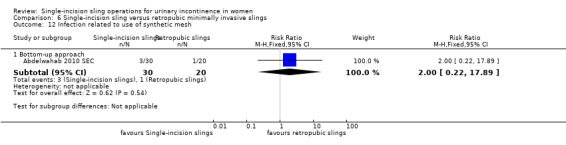

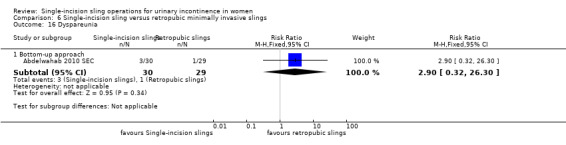

Infection due to synthetic mesh; dyspareunia

Infection related to the use of synthetic mesh and dyspareunia were reported in one small study (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC), but no evidence showed a difference between the procedures (Analysis 6.12; Analysis 6.16).

6.12. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 12 Infection related to use of synthetic mesh.

6.16. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 16 Dyspareunia.

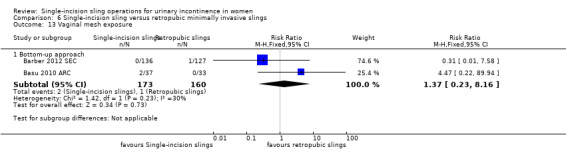

Vaginal mesh exposure

Vaginal exposure (erosion) of mesh was reported in three women in two trials (Barber 2012 SEC; Basu 2010 ARC); this result was not statistically significant and the confidence interval was wide (Analysis 6.13).

6.13. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 13 Vaginal mesh exposure.

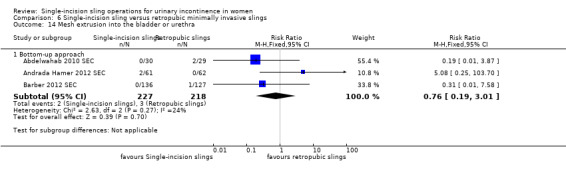

Mesh extrusion into bladder or urethra

Mesh extrusion into the bladder or urethra was reported in five women in three trials (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC; Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Barber 2012 SEC); the combined result showed no evidence of a difference between the two procedures and the confidence interval was wide (Analysis 6.14).

6.14. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 14 Mesh extrusion into the bladder or urethra.

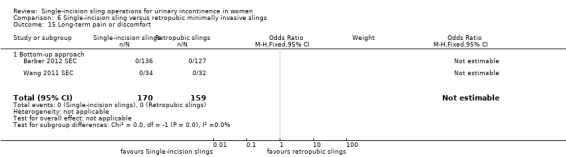

Long‐term pain or discomfort

Two trials reported this outcome (Barber 2012 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC). None of the 329 women reported this adverse effect.

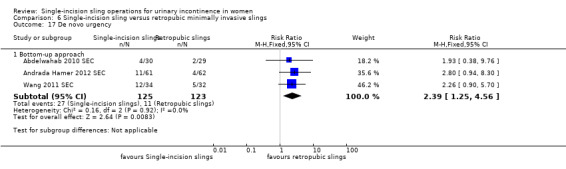

De novo urgency; new‐onset detrusor overactivity

De novo urgency was reported in three trials (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC; Andrada Hamer 2012 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC), all of which compared TVT‐Secur versus TVT. It was more common in the single‐incision group, and the meta analysis showed a statistically significant difference favouring the retropubic TVT procedure (27/125, 22% vs 11/123, 9% after TVT; RR 2.39, 95% CI 1.25 to 4.56) (Analysis 6.17).

6.17. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 17 De novo urgency.

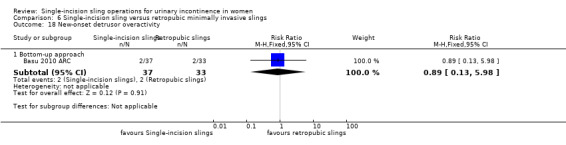

One small trial (Basu 2010 ARC) reported that two women in each group developed new‐onset detrusor overactivity (Analysis 6.18).

6.18. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 18 New‐onset detrusor overactivity.

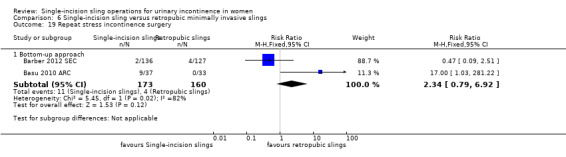

Repeat stress incontinence surgery

Repeat stress incontinence surgery was reported in only two trials (Barber 2012 SEC; Basu 2010 ARC), which used different single‐incision slings. In the Basu trial (Basu 2010 ARC), nine women required further incontinence surgery after a single‐incision sling compared with none in the retropubic sling group—a result that was statistically significant in favour of retropubic slings versus the MiniArc. Although the Barber trial (Barber 2012 SEC) showed no statistically significant difference in the comparison between retropubic slings versus TVT‐Secur, only six women required further surgery and the confidence interval was wide (Analysis 6.19).

6.19. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 19 Repeat stress incontinence surgery.

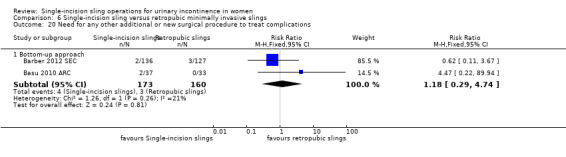

Need for any other additional or new surgical procedure to treat complications

This outcome was reported in Barber 2012 SEC and Basu 2010 ARC. No significant difference was noted in the number of women who required additional procedures to treat complications of the index surgery (Analysis 6.20).

6.20. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Single‐incision sling versus retropubic minimally invasive slings, Outcome 20 Need for any other additional or new surgical procedure to treat complications.

Single‐incision slings versus obturator minimally invasive slings (subgrouped: medial‐to‐lateral 'inside out' approach and lateral‐to‐medial 'outside‐in' approach)

Twenty trials met the inclusion criteria.

Thirteen trials compared single‐incision slings versus inside‐out transobturator slings (Amat 2011 NDL; Bianchi 2012 SEC; Friedman 2009 SEC; Hinoul 2011 SEC; Hota 2012 SEC; Mackintosh 2010 AJS; Masata 2012 SEC; Mostafa 2012 AJS; Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC; Schweitzer 2012 AJS; Seo 2011 SEC; Tommaselli 2010 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC).

Seven trials compared single‐incision slings versus outside‐in transobturator slings (Djehdian 2010 OPH; Enzelsberger 2010 ARC; Kim 2010 SEC; Lee 2012 ARC; Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS; Smith 2011 ARC; Yoon 2011 NDL).

The combined overall results for single‐incision slings versus any types of transobturator slings are stated when available.

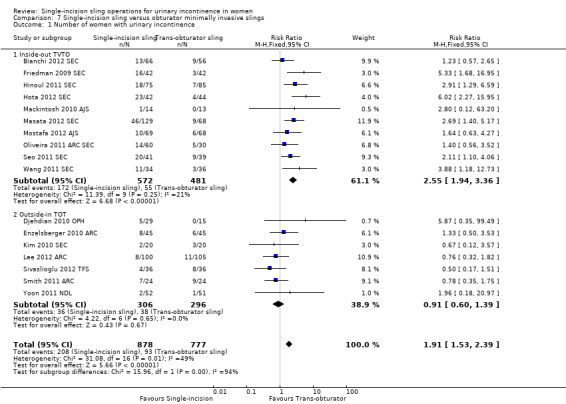

Number of women with urinary incontinence (primary outcome)

Ten trials that compared a single‐incision sling (eight TVT‐Secur, two AJS and one ARC) against inside‐out transobturator slings were included in the meta‐analysis (Bianchi 2012 SEC; Friedman 2009 SEC; Hinoul 2011 SEC; Hota 2012 SEC; Mackintosh 2010 AJS; Masata 2012 SEC; Mostafa 2012 AJS; Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC; Seo 2011 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC). Both Masata 2012 SEC and Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC were three‐arm trials with two types of single‐incision devices. For purposes of this analysis, the data from the single‐incision arms have been combined for each trial. More women had urinary incontinence in the single‐incision sling arms (172/572, 30%), and the overall result was statistically significant in favour of inside‐out transobturator slings (incontinence in 55/481, 11% of women; RR 2.55, 95% CI 1.94 to 3.36) (Analysis 7.1.1). A sensitivity analysis excluding the two trials that did not use TVT‐Secur (Mackintosh 2010 AJS; Mostafa 2012 AJS) made no difference in the results (RR 2.65, 95% CI 1.98 to 3.54) (Analysis 7.1.1). This device has been withdrawn from clinical use.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 1 Number of women with urinary incontinence.

Follow‐up for all trials was 12 months, apart from Bianchi 2012 SEC; Friedman 2009 SEC; and Masata 2012 SEC, which reported two‐year follow‐up, and Mackintosh 2010 AJS, which reported three‐month follow‐up. Exclusion of the Mackintosh 2010 AJS study made no difference in the results.

Seven trials compared five different types of single‐incision slings against outside‐in transobturator slings (Djehdian 2010 OPH; Enzelsberger 2010 ARC; Kim 2010 SEC; Lee 2012 ARC; Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS; Smith 2011 ARC; Yoon 2011 NDL). The overall result was not statistically significant (36/306, 12% vs 38/296, 13%; RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.39; Analysis 7.1), nor was individual comparison by subtype of single‐incision sling. Considerable variation in the range of follow‐up was seen, from four weeks (Yoon 2011 NDL) to five years (Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS). Djehdian 2010 OPH is an ongoing trial with unequal randomisation reported at six‐month follow‐up.

When results for transobturator slings were combined as a single group, the result was still statistically significant in favour of transobturator slings (RR 1.91, 95% CI 1.53 to 2.39) (Analysis 7.1), but this introduces a degree of heterogeneity, with an I2 statistic of 49%.

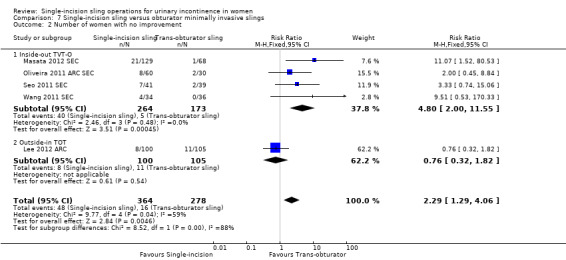

Number of women with no improvement

Four trials that compared TVT‐Secur against inside‐out transobturator slings were included in the meta‐analysis (Masata 2012 SEC; Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC; Seo 2011 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC). Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC was a three‐arm trial; for purposes of analysis, the two single‐incision arms were combined, but a sensitivity analysis showed that this had little impact on the combined result. Masata 2012 SEC had the longest follow‐up, at two years. Similar to the analysis of participant‐reported incontinence rates, the overall result was statistically significant in favour of inside‐out transobturator slings (RR 4.80, 95% CI 2.00 to 11.55; Analysis 7.2).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 2 Number of women with no improvement.

One small trial (Lee 2012 ARC) compared MiniArc against an outside‐in transobturator tape, but the result was not statistically significant.

The combined result was still statistically significant in favour of transobturator slings (RR 2.29, 95% CI 1.29 to 4.06) but with a degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 59%).

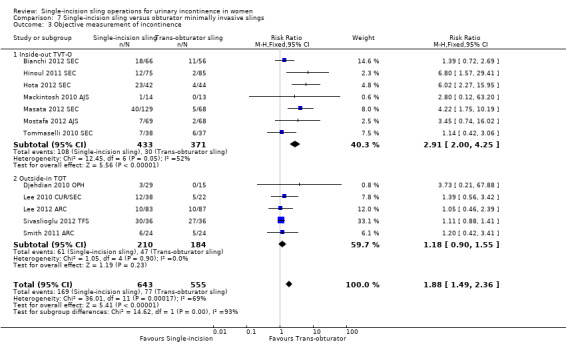

Objective measurement of incontinence

Seven trials that compared TVT‐Secur against inside‐out transobturator slings were included in the meta‐analysis (Bianchi 2012 SEC; Hinoul 2011 SEC; Hota 2012 SEC; Mackintosh 2010 AJS; Masata 2012 SEC; Mostafa 2012 AJS; Tommaselli 2010 SEC). Women were nearly three times more likely to be incontinent with a single‐incision sling, and the overall result was statistically significant in favour of inside‐out transobturator slings (RR 2.91, 95% CI 2.00 to 4.25) (Analysis 7.3.1). Evidence of some statistical heterogeneity was seen in this result, but the direction of effect was the same in all trials.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 3 Objective measurement of incontinence.

Five trials that compared different types of single‐incision slings against outside‐in transobturator slings were included in the meta‐analysis (Djehdian 2010 OPH; Lee 2010 CUR/SEC; Lee 2012 ARC; Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS; Smith 2011 ARC). The result was not statistically significant, but confidence intervals were too wide to ensure no differences between the groups.

Overall, the results obtained when both types of transobturator tapes were combined still favoured the latter (RR 1.88, 95% CI 1.49 to 2.36) (Analysis 7.3).

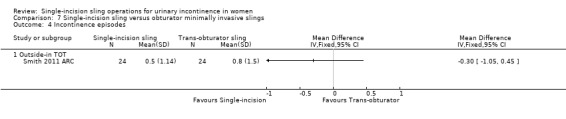

Incontinence episodes

One study (Smith 2011 ARC) compared MiniArc against outside‐in transobturator slings but was too small to show a difference in the number of incontinence episodes at a mean follow up of 33 months (Analysis 7.4).

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 4 Incontinence episodes.

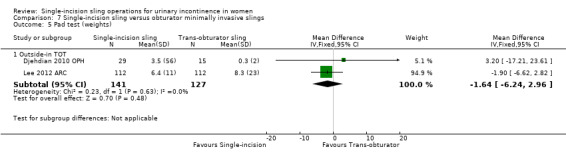

Pad test (weight of urine lost)

Two trials (Djehdian 2010 OPH; Lee 2012 ARC) performed pad tests at six months. However, it must be noted that Djehdian 2010 OPH reported one‐hour pad weights and Lee reported 24‐hour pad weights. Although no statistically significant difference was observed between the groups, the confidence interval was wide (Analysis 7.5).

7.5. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 5 Pad test (weights).

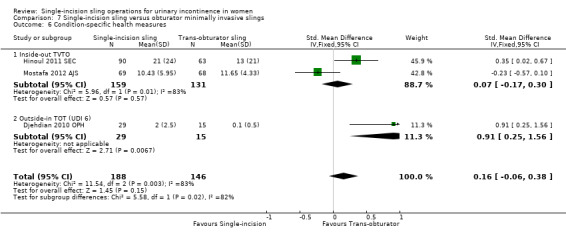

Quality of life

Two trials (Hinoul 2011 SEC; Mostafa 2012 AJS) of single‐incision versus inside‐out transobturator slings are included in this meta‐analysis. Different condition‐specific health questionnaires were used (Urinary Distress Inventory (UDI)‐6 and International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire, Short Form (ICIQ‐SF)); therefore results were combined by using standardised mean differences. The result was not statistically significant (Analysis 7.6.1) and the confidence interval was wide.

7.6. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 6 Condition‐specific health measures.

One small trial compared a single‐incision sling versus an outside‐in transobturator sling (Djehdian 2010 OPH) and favoured the TOT, but a large discrepancy was noted in recruitment for this study, with the single‐incision group almost double the TOT group; therefore the results must be interpreted with caution (Analysis 7.6.2).

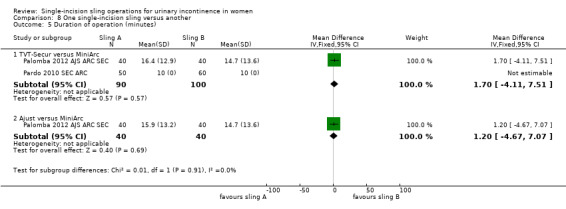

Surgical outcome measures

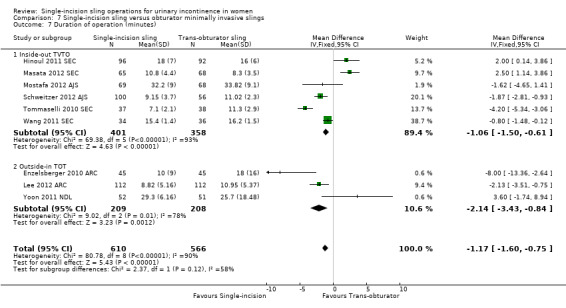

Duration of operation

Six trials (Hinoul 2011 SEC; Masata 2012 SEC; Mostafa 2012 AJS; Schweitzer 2012 AJS; Tommaselli 2010 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC) compared single‐incision slings versus inside‐out transobturator slings, and three trials (Enzelsberger 2010 ARC; Lee 2012 ARC; Yoon 2011 NDL) compared single‐incision slings versus outside‐in transobturator slings.

The overall duration of the operation was one minute less for single‐incision slings (MD ‐1.17 minutes, 95% CI ‐1.60 to ‐0.75) (Analysis 7.7), but the clinical and economic advantages of a one‐minute reduction in theatre time are likely to be negligible. Significant statistical heterogeneity may be explained by differences in the definition of what constitutes "duration of operation."

7.7. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 7 Duration of operation (minutes).

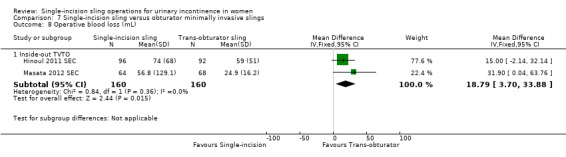

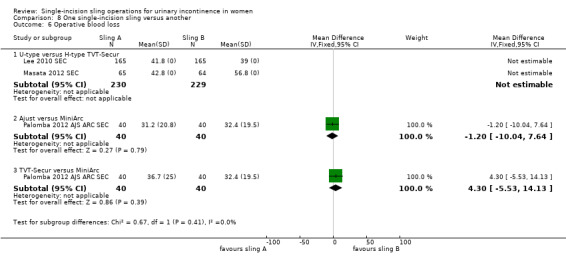

Operative blood loss

Two trials (Hinoul 2011 SEC; Masata 2012 SEC) comparing TVT‐Secur against inside‐out TVT‐O showed that women lost 19 mL less blood with the TVT‐O; this is a statistically significant result favouring TVT‐O (MD 19, 95% CI 4 to 34 mL; Analysis 7.8.1).

7.8. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 8 Operative blood loss (mL).

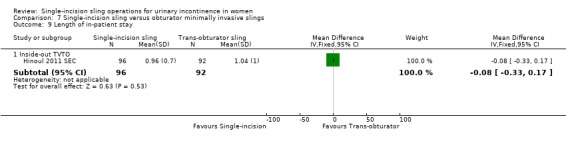

Length of in‐patient stay

One study (Hinoul 2011 SEC) reported this outcome, but the result was not statistically significant.

Adverse events

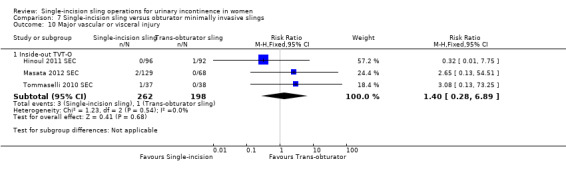

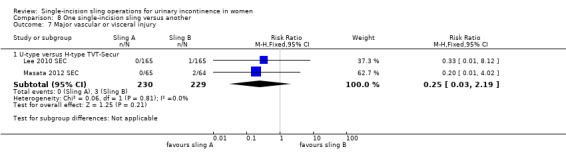

Major vascular or visceral injury

This outcome was reported in three trials (Hinoul 2011 SEC; Masata 2012 SEC; Tommaselli 2010 SEC), all of which compared TVT‐Secur against inside‐out transobturator slings. Very few events were reported, and no evidence suggested superiority of either procedure (Analysis 7.10.1)

7.10. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 10 Major vascular or visceral injury.

Bladder or urethral perforation

This rare outcome (four women in all) was reported in five trials (Amat 2011 NDL; Hinoul 2011 SEC; Masata 2012 SEC; Schweitzer 2012 AJS; Wang 2011 SEC) that compared single‐incision slings versus inside‐out transobturator slings, and in four versus outside‐in TOT (Djehdian 2010 OPH; Enzelsberger 2010 ARC; Lee 2010 CUR/SEC; Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS). The overall results were not statistically significant (Analysis 7.11), but the confidence intervals were wide.

7.11. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 11 Bladder or urethral perforation.

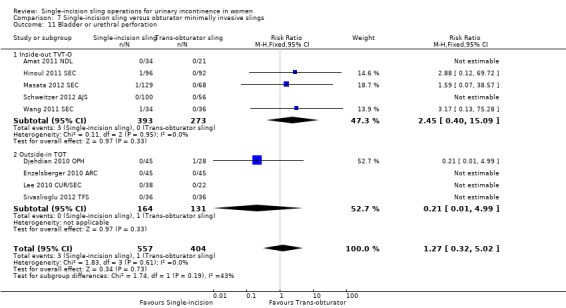

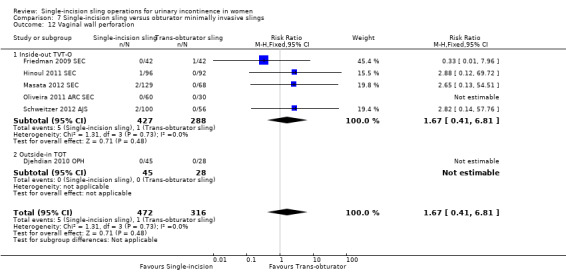

Vaginal wall perforation

Six women had vaginal wall perforation, as reported in five trials (Friedman 2009 SEC; Hinoul 2011 SEC; Masata 2012 SEC; Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC; Schweitzer 2012 AJS) that compared single‐incision slings against inside‐out transobturator slings, and in one trial versus an outside‐in transobturator sling (Djehdian 2010 OPH). The overall result was not statistically significant, and the confidence interval was wide (Analysis 7.12).

7.12. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 12 Vaginal wall perforation.

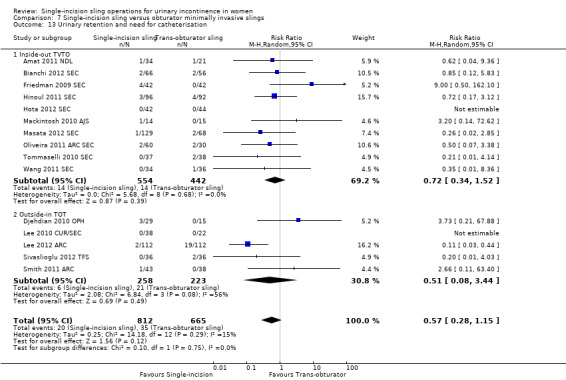

Urinary retention and the need for catheterisation

Ten trials reported this outcome by comparing single‐incision slings against inside‐out transobturator slings (Amat 2011 NDL; Bianchi 2012 SEC; Friedman 2009 SEC; Hinoul 2011 SEC; Hota 2012 SEC; Mackintosh 2010 AJS; Masata 2012 SEC; Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC; Tommaselli 2010 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC). Few women had this complication (2% to 3%), and the overall result was not statistically significant, with a wide confidence interval (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.52) (Analysis 7.13.1).

7.13. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 13 Urinary retention and need for catheterisation.

Five trials compared single‐incision slings against outside‐in transobturator slings (Djehdian 2010 OPH; Lee 2010 CUR/SEC; Lee 2012 ARC; Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS; Smith 2011 ARC). Three times as many women required catheterisation after an outside‐in transobturator sling as after a single‐incision sling (2.5%) or an inside‐out transobturator sling (3.2%); this is difficult to explain. The overall result was statistically significant in favour of single‐incision slings, but the trials were not consistent in this respect. This result was driven mainly by the larger Lee 2012 ARC study, which was given the highest weight in the meta‐analysis. Statistical heterogeneity was apparent, and when a random‐effects model was used, the overall result was no longer statistically significant (Analysis 7.13.2).

The combined result was not statistically significant either and had a wide confidence interval, implying that evidence was insufficient to suggest any difference (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.15) (Analysis 7.13).

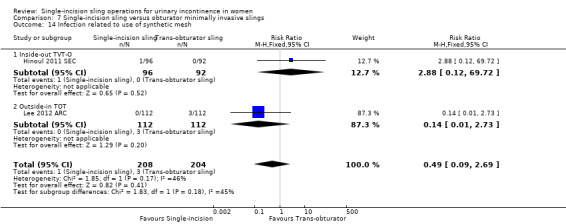

Infection related to the use of synthetic mesh

One study reported this outcome in comparing single‐incision slings against inside‐out transobturator slings (Hinoul 2011 SEC), but the overall result was not statistically significant and the confidence interval was wide (Analysis 7.14.1).

7.14. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 14 Infection related to use of synthetic mesh.

Another study also reported this outcome in comparing single‐incision slings against outside‐in transobturator slings (Lee 2012 ARC), but again the overall result was not statistically significant and the confidence interval was wide (Analysis 7.14.2).

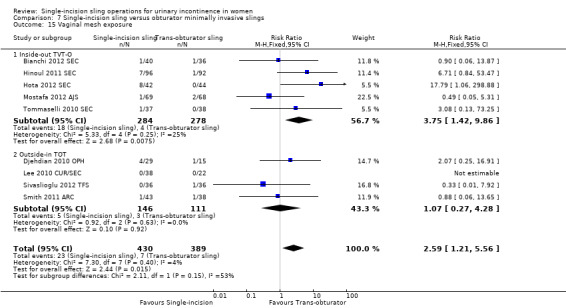

Vaginal exposure of mesh

Vaginal exposure (erosion) of mesh was reported in five trials (Bianchi 2012 SEC; Hinoul 2011 SEC; Hota 2012 SEC; Mostafa 2012 AJS; Tommaselli 2010 SEC) that compared single‐incision slings (all TVT‐Secur) against inside‐out transobturator slings. More women in the single‐incision groups had exposure (18/284, 6% vs 4/278, 1%), and the overall result was statistically significant, favouring inside‐out transobturator slings (RR 3.75, 95% CI 1.42 to 9.86) (Analysis 7.15.1). Four trials (Djehdian 2010 OPH; Lee 2010 CUR/SEC; Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS; Smith 2011 ARC) compared single‐incision slings against outside‐in transobturator slings. The number of cases was fewer, and the overall result was not statistically significant, with a wide confidence interval (Analysis 7.15.1).

7.15. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 15 Vaginal mesh exposure.

The combined overall result was still significant in favour of transobturator slings (RR 2.59, 95% CI 1.21 to 5.56) (Analysis 7.15).

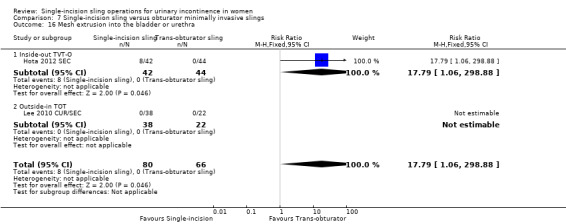

Mesh extrusion into bladder or urethra

Only two small trials reported on this outcome (Hota 2012 SEC; Lee 2010 CUR/SEC). Only eight women were reported to have this complication, all in the single‐incision sling group in one of the trials: A statistically significant result favouring transobturator slings was of dubious reliability because of the small numbers (Analysis 7.16).

7.16. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 16 Mesh extrusion into the bladder or urethra.

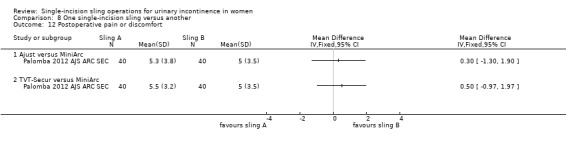

Post‐operative pain or discomfort

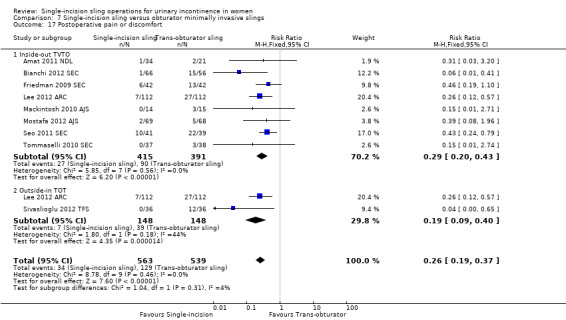

Pain was reported in eight trials (Amat 2011 NDL; Bianchi 2012 SEC; Friedman 2009 SEC; Lee 2012 ARC; Mackintosh 2010 AJS; Mostafa 2012 AJS; Seo 2011 SEC; Tommaselli 2010 SEC). The overall result was statistically significant favouring single‐incision slings: Fewer women (27/415, 7%) had pain versus 90/391 (23%) after an inside‐out transobturator sling (RR 0.29, 95% 0.20 to 0.43) (Analysis 7.17.1). Most of the trials used TVT‐Secur as the experimental intervention, apart from Amat 2011 NDL; Lee 2012 ARC; and Mackintosh 2010 AJS, but a sensitivity analysis excluding these trials made little difference in the results for individual single‐incision sling subtypes. Two trials (Lee 2012 ARC; Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS) compared single‐incision slings against outside‐in transobturator slings, and the result was similar, with statistical significance in favour of single‐incision slings (Analysis 7.17.2).

7.17. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 17 Postoperative pain or discomfort.

The combined overall result showed that women had less short‐term pain or discomfort after a single‐incision sling (34/563, 6% vs 129/539, 23.9% after a TOT; RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.37) (Analysis 7.17), but the relevance of this difference may not be clinically important to women.

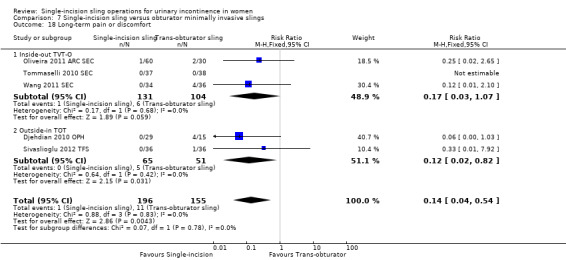

Long‐term pain or discomfort

This was rare and was reported in only three trials comparing TVT‐Secur against inside‐out transobturator slings (Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC; Tommaselli 2010 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC) and in two trials comparing single‐incision slings against outside‐in transobturator slings (Djehdian 2010 OPH; Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS). A statistically significant difference favoured single‐incision slings in the latter case only (RR 0.12, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.82) (Analysis 7.18.2).

7.18. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 18 Long‐term pain or discomfort.

Although uncommon, women were significantly less likely to have long‐term pain after a single‐incision sling than after a transobturator sling, and the overall result favoured single‐incision slings (1/196, 0.5% vs 11/155, 7.1%; RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.54) (Analysis 7.18).

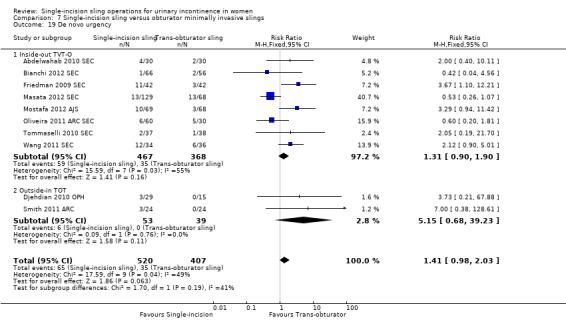

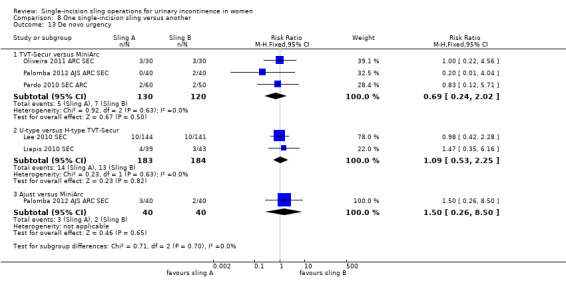

De novo urgency

Eight trials were included in the meta‐analysis comparing TVT‐Secur versus inside‐out transobturator tapes (Abdelwahab 2010 SEC; Bianchi 2012 SEC; Friedman 2009 SEC; Masata 2012 SEC; Mostafa 2012 AJS; Oliveira 2011 ARC SEC; Tommaselli 2010 SEC; Wang 2011 SEC). Overall no statistically significant difference between the groups was observed (Analysis 7.19.1). Two trials compared single‐incision slings versus outside‐in transobturator tapes (Djehdian 2010 OPH; Smith 2011 ARC) and again found no statistically significant difference between the groups (Analysis 7.19.2).

7.19. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 19 De novo urgency.

Around 10% of women reported this symptom. The overall result was not quite statistically significant in favour of transobturator slings but the confidence intervals were wide (RR 1.41, 95% CI 0.98 to 2.03) (Analysis 7.19).

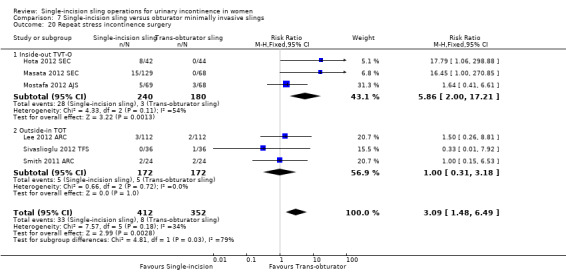

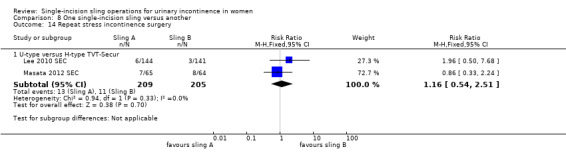

Repeat stress incontinence surgery

Three trials compared TVT‐Secur against inside‐out transobturator slings (Hota 2012 SEC; Masata 2012 SEC; Mostafa 2012 AJS); the pooled analysis showed that women were nearly six times more likely to need further stress incontinence surgery after a single‐incision sling—a significant difference in favour of transobturator slings (28/240, 12% vs 3/180, 2%; RR 5.86, 95% CI 2.0 to 17.21) (Analysis 7.20.1). Two trials compared MiniArc versus outside‐in transobturator tapes (Lee 2012 ARC; Smith 2011 ARC) but found no difference between the groups, as did one study (Sivaslioglu 2012 TFS) that compared the tissue fixation system single‐incision sling (TFS) versus outside‐in transobturator tapes (Analysis 7.20.2).

7.20. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Single‐incision sling versus obturator minimally invasive slings, Outcome 20 Repeat stress incontinence surgery.

The overall result was still statistically significant in favour of transobturator slings: Women are three times more likely to need repeat incontinence surgery after a single‐incision sling (33/412, 8.0% vs 8/352, 2.3%; RR 3.09, 95% CI 1.48 to 6.49) (Analysis 7.20). However, this result was driven by the two trials that used TVT‐Secur (Hota 2012 SEC; Masata 2012 SEC). Without these two trials, no significant difference in repeat surgery rates would be reported.

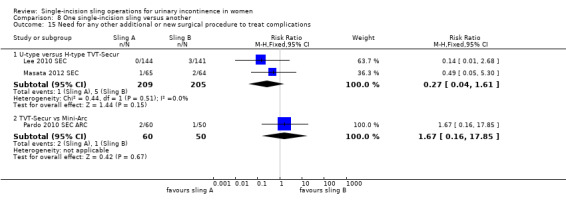

Need for any other additional or new surgical procedure to treat complications