Abstract

Introduction

Recent data suggest the urinary tract hosts a microbial community of varying composition, even in the absence of infection. Culture-independent methodologies, such as next-generation sequencing of conserved ribosomal DNA sequences, provide an expansive look at these communities, identifying both common commensals and fastidious organisms. A fundamental challenge has been the isolation of DNA representative of the entire resident microbial community, including fungi.

Materials and methods

We evaluated multiple modifications of commonly-used DNA extraction procedures using standardized male and female urine samples, comparing resulting overall, fungal and bacterial DNA yields by quantitative PCR. After identifying protocol modifications that increased DNA yields (lyticase/lysozyme digestion, bead beating, boil/freeze cycles, proteinase K treatment, and carrier DNA use), all modifications were combined for systematic confirmation of optimal protocol conditions. This optimized protocol was tested against commercially available methodologies to compare overall and microbial DNA yields, community representation and diversity by next-generation sequencing (NGS).

Results

Overall and fungal-specific DNA yields from standardized urine samples demonstrated that microbial abundances differed significantly among the eight methods used. Methodologies that included multiple disruption steps, including enzymatic, mechanical, and thermal disruption and proteinase digestion, particularly in combination with small volume processing and pooling steps, provided more comprehensive representation of the range of bacterial and fungal species. Concentration of larger volume urine specimens at low speed centrifugation proved highly effective, increasing resulting DNA levels and providing greater microbial representation and diversity.

Conclusions

Alterations in the methodology of urine storage, preparation, and DNA processing improve microbial community profiling using culture-independent sequencing methods. Our optimized protocol for DNA extraction from urine samples provided improved fungal community representation. Use of this technique resulted in equivalent representation of the bacterial populations as well, making this a useful technique for the concurrent evaluation of bacterial and fungal populations by NGS.

Introduction

Multiple organs, such as the gut, oral cavity, and vagina, have long been known to harbor communities of microbes that can protect against or contribute to disease under different circumstances. The urinary tract, however, was widely thought to be sterile until only recently, when extended culture techniques and the detection of microbial DNA definitively demonstrated microbial communities of great diversity within this site.[1–3] Currently, culture-independent microbial characterization using the sequencing of highly conserved DNA regions, such as the ribosomal RNA gene locus (rDNA), is widely-accepted as a useful, sensitive tool to explore microbial populations. These next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies are particularly useful in characterizing microbes that may be difficult to culture or that are present in low abundance (the “rare biosphere”).[4] Therefore, the composition and diversity of the urinary microbiome has likely been drastically understated, in part, due to dependence on culture methods to identify resident species.

With the development of affordable, rapid, and scalable culture-independent methods for the study of bacterial communities, the last decade has seen a massive expansion in studies aimed at profiling commensal communities in a multitude of organs not included in the large-scale Human Microbiome Project (HMP), such as the urinary tract. Using NGS methods, multiple studies have demonstrated that perturbations in the urinary microbiota appear to correlate with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS).[5–13] The clinical significance and utility of these alterations, however, remain unclear, primarily due to challenges that persist for the characterization of microbes from low biomass specimens, such as urine.

Due to these limitations, we still lack vital information about the content of normal urine and its relationship to dysbiosis and/or disease. Studies examining the urinary microbiome thus far demonstrate wide variation in their ability to consistently detect microbial species. In many studies, approximately half of patient samples do not have bacterial sequences of sufficient quality for analysis[2, 6, 14]; in other studies, this efficiency could be improved with the use of multiple amplification steps[11], but this may introduce new biases that could skew results. This low sequencing efficiency is likely due to the combination of low biomass and the unique qualities of urine, which include high variability in osmolality/salt content, high abundance of PCR inhibitors, and fluctuating levels of cellular material, all in all making urine a challenging biological fluid to study. The question remains as to whether these sequence-negative samples are truly negative for microbes or whether our detection methods are inadequate to fully characterize these specimens. Until this question can be answered, it remains a very real possibility that the subset of samples analyzed, the “sequence-positive” group, may represent a unique subgroup within the analyzed population with higher microbial loads, whose findings cannot be generalized to the larger sample population.

Even less is known about the composition of non-bacterial populations, such as fungi, viruses, archaea, and protozoa, in the genitourinary tract and other human organs, primarily from a lack of well-researched tools for their analysis. Despite these challenges, alterations in the fungal microbiota (the “mycobiome”) in the absence of frank infection have been demonstrated in multiple human diseases, such as hepatitis [15], atopic dermatitis [16], inflammatory bowel disease [17–19], cystic fibrosis [20], allergy/atopy [21], asthma [22], and psoriasis [23, 24]. As yet, only a few analyses have examined aspects of the urinary mycobiome. Candida spp. have been detectable in urinary samples by culture,[5–8] demonstrating their viability. Fungi were also detectable in urine from patients with urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPS) using the targeted Ibis T-5000 Universal Biosensor system.[25] Interestingly, fungi were detected more frequently in UCPPS patients during symptomatic flares, while no significant differences in the bacterial microbiota could be identified, implicating fungi as important players in lower urinary tract symptomatology. Even in this culture-independent study, however, fungi were detected in less than 10% of patients overall. Again, it is unclear if this low number is representative of the absence of fungi in the majority of subjects or represents severe limitations in our current technologies.

Further progress in identifying consistent microbial markers or understanding the pathophysiology of microbial interactions in the urinary tract requires methodologies that adequately and reliably characterize these populations, and which include fungi and other microbes in addition to bacteria. In this study, we sought to identify the most effective strategies for extracting and identifying microbial DNA from urine, with a focus on enhancing the detection of fungi. Using an iterative approach, we optimized urine sample processing at multiple steps to increase DNA yields and population representation to generate more consistent data from sequencing-based microbial population analyses.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Cedars-Sinai Institutional Review Board (Pro00033267) and written consent was obtained from all subjects.

DNA yield assessment

Overall DNA yields and quality (assessed by OD260/OD280 ratios) were measured on the NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Fungal DNA levels were assessed in duplicate by quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) analyses on a Mastercycler Realplex2 (Eppendorf) using the SYBR Green PCR kit as instructed by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems). Fungal levels were assessed using the Fungiquant primers (forward: 5′-GGRAAACTCACCAGGTCCAG-3′; reverse: 5′-GSWCTATCCCCAKCACGA-3′)[26] that recognize a highly-conserved segment of the fungal 18S rDNA region, while bacterial levels were assessed using 16S rDNA primers (forward: 5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGT-3’; reverse: 5’-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGGC-3’), a universal primer with broad specificity for bacteria. The qRT-PCR protocol employed an initial denaturation at 94°C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, and elongation at 72°C for 2 min, followed by an elongation step at 72°C for 30 min. Relative quantity of bacterial and fungal DNA yields, consistent from experiment to experiment, was calculated by the comparative CT method (2-ΔΔCT method)[27] and normalized to a DNA standard curve derived from a mixed bacterial and fungal culture that remained constant over all tests. Samples with greater than 3% variance between duplicates were reanalyzed in duplicate. An aliquot of 1 μl of the PCR product was evaluated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Evaluation of individual protocol enhancements

For the initial, iterative analyses, specimens were obtained from mid-stream urine collections from multiple male and female subjects, all of whom denied any urinary symptoms, after preparation of the external urethral meatus with chlorhexidine gluconate wipes. Urine specimens were mixed well, then divided into 1 ml samples and centrifuged at 5000 relative centrifugal force (rcf) to pellet cellular material prior to parallel processing to test the individual protocol variations described below.

Enzymatic disruption

Sample pellets were initially resuspended in 500 μl enzyme buffer containing a reducing agent (0.5 M Tris, 1mM EDTA, and 0.2% 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.5). We added 200 U/ml Lyticase (Sigma Aldrich), 20 mg/ml Lysozyme (Thermo Scientific), both enzymes, or buffer alone without enzyme. Samples were then incubated for 30 min. at 30°C, with inversion of the tubes every 5–10 min. Subsequently, samples were centrifuged at 1500 rcf for 5 min, the supernatant removed, and the pellet resuspended in 800 μl of Stool DNA Stabilizer (Stratec Biomedical).

Mechanical disruption

Physical disruption of cell walls was accomplished with bead beating. The 800 μl post-enzymatic digestion cell suspension was transferred to a 2 ml centrifuge tube containing 100 μl 0.1 mm and 300 ul 0.5 mm silica beads (Biospec Products, Inc.). Samples were agitated twice for 1 min each on a standard Vortex mixer using a Vortex Adapter for bead beating (MO BIO Laboratories Inc.). Samples were centrifuged for 15 s at 17000 rcf between bead beating periods.

Thermal disruption

Samples were heated to 95°C for 10 min, with a brief vortex to ensure adequate mixing 5 min into the incubation. After a second, brief vortexing step, samples were incubated on ice (0°C) for 5 min, then centrifuged for one min. at 17000 rcf after each boil/freeze cycle.

Proteinase digestion

After cell wall disruption, cell lysates were transferred to new tubes containing an equal volume of buffer AL (Qiagen) containing varying concentrations of Proteinase K (0, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, or 144 mAU/ml)(Qiagen), then incubated at 70°C for 10 min.

Addition of carrier DNA

When specified, polyadenylic acid carrier DNA (PolyA) (Roche Diagnostics) was added to the cell lysates at the time of proteinase K digestion.

Column DNA extraction

Following the specified disruption and digestion steps, 250 μl 100% Ethanol was added and briefly mixed by vortexing, prior to applying the cell lysates to Qiagen Mini DNA Spin columns (Qiagen). The columns were washed twice with a column volume of buffer AW (Qiagen) by centrifugation at 17000 rcf for 1 min and residual alcohol removed with a third spin without wash buffer. DNA was then eluted from the column in 60 μl warm Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer.

Confirmation of protocol components in aggregate analysis

For 4 subjects (2 male and 2 female), >60 ml of urine were obtained and divided into 1 ml samples within 1 h of sample collection. Twenty unique conditions were analyzed following centrifugation at one of three centrifugation conditions: 1) 1500 rcf for 15 min., 2) 5000 rcf for 20 min., or 3) 16000 rcf for 10 min. The resulting pellets were frozen and stored at -80°C. 20 unique combinations of the conditions explored in initial, iterative analysis were performed, with inclusion or exclusion of the individual enzymatic treatments, mechanical and thermal disruption steps, and proteinase digestion in almost all combinations. For this panel of conditions, carrier DNA was included in all samples to provide better discrimination of differences in these low volume samples.

Relative DNA yields for each condition were determined by fungal-specific qPCR as specified above; for each sample, yields were scaled to equal variance for all samples to allow plotting of the median yields for each condition as a heat map.

Determination of optimal sample volume

Large volume urine samples (>100 ml) from 3 male and 3 female subjects were mixed well and subdivided into 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 25, and 50 ml aliquots. Each sample was centrifuged at 1500 rcf and the supernatant decanted. After pelleting, all samples were identically processed using the optimized protocol detailed above. All aliquots for an individual subject were processed in batches to minimize batch-to-batch variation. The resulting fungal DNA concentrations were then quantitated by qRT-PCR. Taxal diversity was also examined by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Sample subdivision and pooling

To evaluate if processing lysates in smaller volumes provided increased DNA yields, samples were subdivided into smaller aliquots after mechanical disruption. Seven identical urine specimens were pelleted, digested with lysozyme and lyticase, then subjected to bead beating with a mixture of silica beads as detailed above. Sample quantities ranging from 100 μl to 400 μl (of an approximately 500 μl total lysate volume) at 50 μl intervals were aspirated off of the beads and subjected to thermal disruption, proteinase K digestion and DNA-column binding and elution.

To examine if total DNA yields could be increased by pooling these smaller aliquots, sample lysates were subdivided into two 250 μl aliquots after mechanical disruption, then subjected to thermal disruption and proteinase digestion separately. These two samples were then applied to either a single DNA-binding column in succession or to two separate columns, eluted and pooled after elution. Overall and fungal-specific DNA yields were then measured using NanoDrop DNA quantitation and fungiquant qRT-PCR.

Light microscopy

After centrifugation, cellular pellets from urine were resuspended in 5 ml PBS and mixed well with a pipette. A 10 μl aliquot was transferred to a 75 × 26-mm glass slide and covered with an 18 × 18-mm coverslip, ensuring that the sediment was uniformly distributed but not escaping from the edges of the coverslip. Using an inverted IX51 microscope (Olympus), images without staining were captured at ×400 (objective lens 40× in combination with wide field 10x eyepiece) to generate a field area of 0.196 mm2.

Comparison with commercial methods

We compared our optimized approach to three, commonly used commercial kits for DNA extraction: PSP Spin Stool DNA Plus Kit (Stratec Biomedical), PureLink Microbiome DNA Purification Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific), and QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen). Large volume urine specimens (>120 ml) from 9 subjects were divided into four 30 ml specimens and pelleted by centrifugation at 1500 rcf. Mid-vaginal swabs were obtained from female subjects using FloQSwabs (Copan Diagnostics). Swabs were gently agitated for 30 min in 500 μl enzyme buffer (0.5 M Tris, 1mM EDTA, and 0.2% 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.5), before removing the swab; the resulting cell suspension was then processed as for urine specimens. The identical urine samples and vaginal swabs were processed according to the manufacturers’ protocols for each kit or using our optimized protocol. Fungal and bacterial DNA yields in the eluents were then assessed by qPCR as specified above.

Microbial sequencing analysis

Library generation

DNA was isolated from urine using the specified protocols as described above. Fungal ITS1 and bacterial 16S regions amplicons were generated by PCR using the primers below (Table 1) modified to include Nextera XT v2 barcoded primers (Illumina) to uniquely index each sample. Mock samples run in parallel with urine samples lacking any starting cellular pellet as well as individual aliquots of all reagents and buffers were analyzed to ensure validity and rule out any systemic contamination.

Table 1. Next-generation sequencing primers.

| Amplicon | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| ITS1 | 5’-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3’ | 5’- GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3’ |

| 16S (8F&R357) | 5’-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3’ | 5’-CTGCTGCCTYCCGTA-3’ |

PCR reactions utilized Platinum SuperFi DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) according to the following protocol: initial denaturation at 94°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 48°C for 30 s, and elongation at 72°C for 2 min., followed by an elongation step at 72°C for 30 min.

Next-generation sequencing

Amplicons generated above were sequenced at 2x300 paired-end sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq sequencer, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Raw data processing and de-multiplexing was performed using on-instrument MiSeq Reporter Software v2.6 as per manufacture recommendations. Demultiplexed 16S sequence data were processed and analyzed as previously described including OTU assignment by alignment to the GreenGenes reference database (May 2013 release) at 97% identity.[28] For analysis of ITS1 sequence data, raw FASTQ data were filtered to enrich for high quality reads including removing the adapter sequence by Cutadapt v1.4.1,[29] truncating reads with average quality scores less than 20 over a 3-base pair sliding window and removing reads that do not contain the proximal primer sequence or that contain a single unknown base. Filtered pair-end reads were then merged with overlap into single reads using SeqPrep v1.1 wrapped by QIIME v1.9.1.[30] Processed high-quality reads were then aligned to previously observed host sequences (including rRNA and uncharacterized genes in human) to deplete potential contamination. Operational taxonomic units (OTU) were identified by alignment of filtered reads to the Targeted Host Fungi (THF) custom fungal ITS database (version 1.6), [31] using BLAST v2.2.22 in the QIIME v1.9.1 wrapper with an identity percentage ≥97%.

Diversity analysis

We performed rarefaction analysis. The original OTU table was randomly subsampled (rarefied) to create a series of subsampled OTU tables. Alpha diversity was calculated on each sample using the OTU table and a variety of metrics (chao1, observed species, etc.). The results of the alpha diversity were collated into a single file and the number of species identified for each sample versus the depth of subsampling was plotted. Shannon diversity indices were selected to show composite readout of microbial population evenness and richness.

Statistical analysis

Differences in DNA yields between groups were compared using a two-tailed, paired Student’s t test with a 95% confidence interval. Data are presented as means ± SEM, unless otherwise stated. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2016 (version 1803) or RStudio version 3 as appropriate.

Results

Sequential optimization of fungal DNA extraction

To optimize the procedure of isolating urinary microbial DNA, we began with a protocol described in the initial isolation of bacteria from urine specimens,[5, 32]. Small volumes of urine were initially centrifuged to concentrate cells and microorganisms, then subjected to DNA extraction using a standardized kit involving DNA binding and elution from an affinity column.

To concentrate the rare cellular material present in urine, samples were centrifuged under three conditions previously described for the isolation of fungi from low biomass fluids.[32–34] Samples prepared with an initial centrifugation speed of 1500 relative centrifugal force (rcf) for 20 min. yielded fungal DNA levels at least 1.5-fold higher than those prepared at 5000 rcf for 10 min., while yields from those centrifuged at 16000 rcf for 10 min. were substantially lower (Fig 1A). While a subset of individual samples demonstrated similar yields following centrifugation at 5000 rcf as that seen after centrifugation at 1500 rcf, the lower speed was never associated with a decrease in overall or microbial DNA yields (S1 Fig).

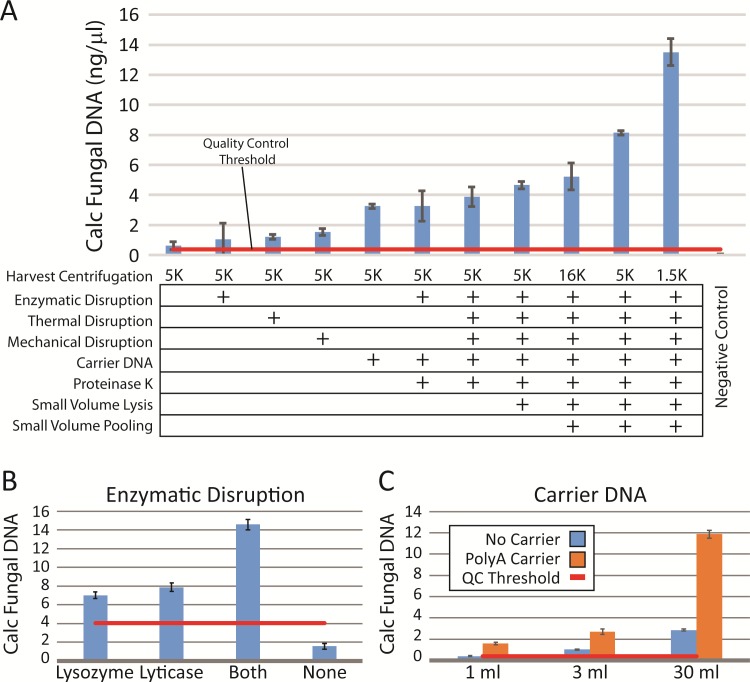

Fig 1. Optimization of microbial dna extraction requires multiple disruption steps.

(A) Eight variations in the protocol (at left) were noted to increase yields as determined by quantitative PCR. Relative fungal DNA yields were calculated from quantitative PCR using the Fungiquant pan-fungal PCR primer pair and normalized to a mixed fungal DNA standard. The negative control samples were processed in parallel, but did not have any input cellular material. Multiple protocol variations, such as enzymatic pre-digestion (B) or carrier DNA use during DNA column binding (C), were tested individually in triplicate for multiple subjects (minimum n = 4), both male and female, before incorporating.

Fungi and some bacteria have cell walls, which can be resistant to digestion, leading to their absence or underrepresentation in culture-independent analyses. To optimize the isolation of organisms with robust cell walls, we examined the utility of an initial enzymatic digestion step to aid in cell wall dissolution.[35] Lysozyme, a glycolytic hydrolase that catalyzes the breakdown of peptidoglycan in gram-positive bacterial cell walls, is known to enhance gram-positive bacterial detection.[36] Lyticase, which hydrolyzes the poly-β(1→3)-glucose present in yeast cell wall glycans, has been widely used in yeast DNA extraction, including PCR-based clinical assays.[34, 37] These enzymes were tested alone and in combination in comparison to omission of this step. Consistently, the combination of the two enzymes resulted in improved yields of both total DNA (data not shown) and relative fungal DNA levels calculated by qPCR (Fig 1B).

Particularly for fungi, physical disruption techniques, such as the thermal and mechanical steps described above, significantly improve fungal DNA purification,[38–40] again by further breaking down tough cell walls. Bead beating, which we performed using multiple sizes of silica beads, can be particularly useful in isolation of fungi such as Aspergillus, which is known to play a role in multiple human diseases.[41, 42] An additional thermal disruption step, with two freeze-boil (0°C/95°C) cycles, was also evaluated. Both methods used in isolation enhanced DNA extraction efficiency 2-3-fold over baseline (Fig 1A).

These disruption steps were followed by an additional digestion step with Proteinase K, a broad-spectrum serine protease, to remove any protein contamination and inactivate any remaining DNAase activity prior to cell and nuclear lysis. We tested a range of proteinase concentrations; while inclusion of the enzyme was important in enhancing DNA extraction efficiency, varying the proteinase concentration had much less effect. While a concentration of 24 mAU/ml (0.8 μg/ml) tended to provide the best results, a range of concentrations from 12–144 mAU/ml (4.8 μg/ml) did not differ significantly in their enhancement of DNA recovery (data not shown).

To maximize DNA recovery, we also evaluated the addition of carrier DNA. Because naturally occurring carriers, such as salmon sperm DNA, contain rDNA sequences with partial homology to other eukaryotic DNA, we chose a synthetic carrier, polyadenylic acid, which has shown efficacy in enhancing recovery of low abundance DNA from human biological samples.[43] Supplementation of carrier DNA increased both overall (data not shown) and fungal-specific DNA yields 2–4 fold across all samples (Fig 1C). The best combination of all techniques tested resulted in an almost 14-fold increase in fungal DNA yields, comprising an optimal protocol utilizing low-speed centrifugation, enzymatic, mechanical, and thermal cell wall disruption, inclusion of carrier DNA, and proteinase K digestion in combination.

Confirmation of protocol on standardized samples

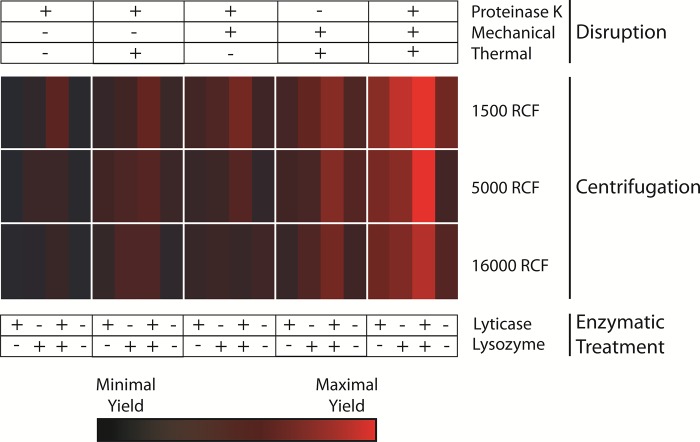

Each of the individual conditions noted to increase DNA yields was tested in aggregate on a panel of urine specimens from both male and female patients. Large volume (>75 ml) urine specimens from 4 subjects (2 male and 2 female) were divided into small equal aliquots (1 ml), and then processed in parallel to confirm the enhancement of DNA purification with the modifications observed in the individual experiments detailed above. This larger-scale optimization panel assessed the variations in cell wall disruption methods (thermal and mechanical), enzymatic pre-treatment methods (lysozyme and lyticase), proteinase K digestion, and centrifugation speed in almost all combinations (Fig 2). Calculation of the relative fungal DNA yields from these 60 variations in isolation methodology revealed a clear pattern, with improved yields resulting from the optimized protocol defined above with multiple disruption methods, combined enzymatic digestion, and lower centrifugation speeds.

Fig 2. Large-scale confirmation of optimization of microbial DNA purification.

The individual conditions noted to increase yields were tested in aggregate in a larger-scale optimization panel. DNA was concurrently isolated from 60 identical 1 ml urine samples from each of 4 subjects with variations in cell wall disruption methods (as indicated at the top), enzymatic pre-treatment methods (bottom), and centrifugation speeds (rows indicated at right adjacent to heat map). Fungal DNA yields from these 60 variations in isolation methodology were calculated from Fungiquant qPCR as described in Fig 1, then scaled across all samples. Values are expressed as a heat map, with bright red signifying the highest yields and black the lowest yields across all samples.

Effect of sample volume on community profiling

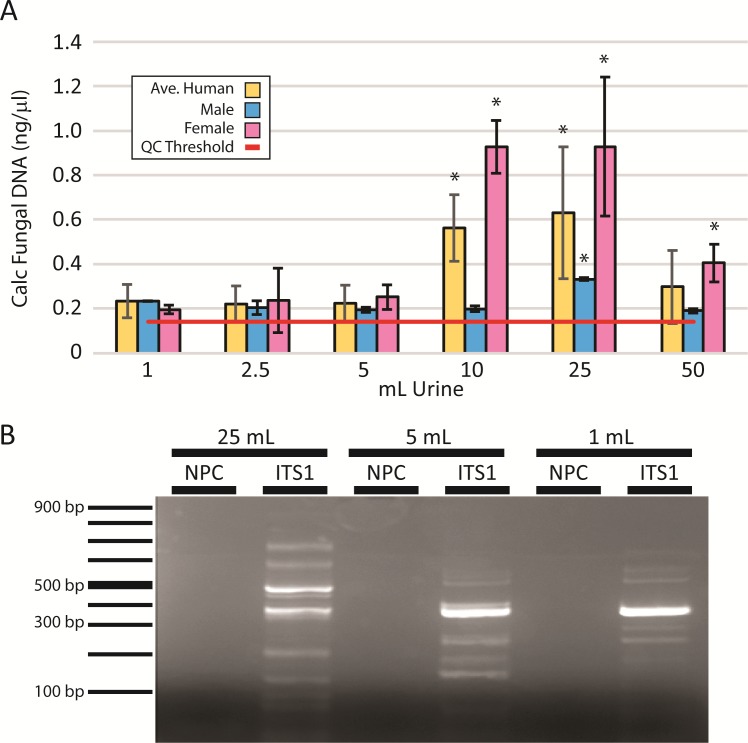

Specimen volume is thought to influence the representation of microbial complexity determined by NGS, particularly in low biomass specimens, such as urine[44], which was also suggested by our preliminary results (Fig 1C). To determine the magnitude of the effect of sample volume on microbial yields and community depth and diversity, we examined microbial profiles across a range of urine sample volumes. Large volume urine specimens from individual subjects were divided into 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 25, and 50 ml aliquots and processed in parallel according to our optimized protocol described above. Fungal yields (Fig 3A) were greatest with larger urine volumes. However, the optimal volume of initial urine was 25 ml, with 10 and 25 ml samples yielding substantially greater DNA concentrations than smaller or larger amounts. Average yields across all specimens decreased in 50 ml samples.

Fig 3. Fungal community representation is influenced by specimen volume.

(A) DNA was isolated from a range of urinary volumes in male and female subjects (n = 3 each) and assessed by qPCR for fungal DNA. Calculated fungal DNA concentrations were calculated by normalization to a fungal standard. The optimal concentrations were achieved using 25 ml urine specimens. *: P<0.05 in comparison to 1 mL yields. (B) Following fungal DNA amplification by qPCR using broad-spectrum fungal primers, products from 25, 5 and 1 ml samples were assessed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Standards indicating the PCR product size are shown on the left. Each band represents unique taxa within the urinary fungal population. NPC: no primer control.

While increasing the quantity of urine processed may increase the cellular material, it also increases urinary salts. We hypothesized that these increased salt loads interfered with DNA isolation when utilizing a DNA-binding column. We emulated this situation by adding increasing urinary phosphate salts to standardized urine specimens to emulate the salt burden of larger samples. As typical urinary phosphate salt concentrations are 1–30 mg/dl, an additional 20 ml of urine would provide an additional 2–60 mg of salt per sample. Addition of this amount of sodium phosphate salts was clearly associated with lower microbial DNA yields, particularly for bacteria (S2 Fig).

We also assessed community complexity by gel electrophoresis following PCR-based amplification of the fungal ITS1 rDNA region in which different sized products represent unique fungal taxa (Fig 3B). In comparison to sample sizes of 5 ml or less, 25 ml provided a more comprehensive representation of the range of fungal species with an increased number of bands of varying sizes representing unique taxa for larger initial sample sizes. Across all volumes, urine from male subjects consistently demonstrated lower yields. Only at the 25 ml volume were fungal DNA yields consistently above quality control thresholds.

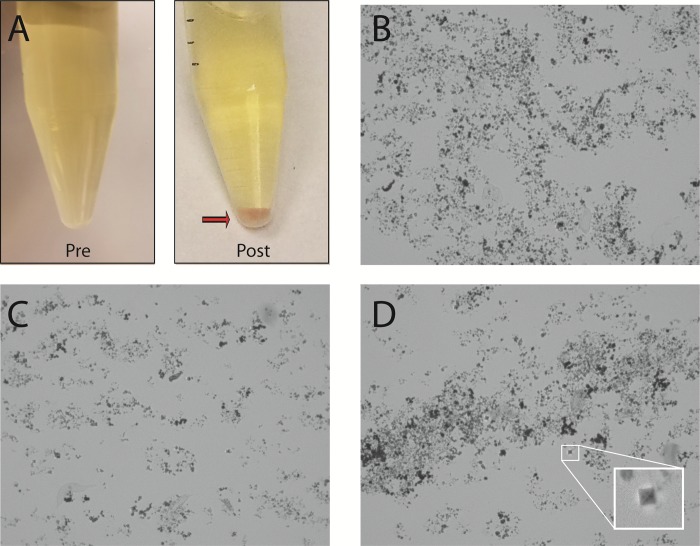

Effect of urine storage and centrifugation conditions on DNA extraction efficiency

In handling urine, we sporadically observed after centrifugation a substantial, sand-like pellet of varying colors. The appearance of this non-cellular pellet material was observed with refrigeration (>2 hours) of urine samples prior to processing and with high-speed centrifugation (16,000 rcf). Post-centrifugation pellets from larger urine volumes (>50 ml) also would frequently contain this material, even when pelleted at lower speeds (1500–5000 rcf) and processed at room temperature. Microscopic examination of these samples revealed a range of crystalline forms, typically amorphous urates or phosphates, depending on urinary pH. When these microcrystal salts appeared, DNA quality, as assessed by OD260/OD280 ratios, was significantly lower. Relative microbial DNA yields were also consistently lower, suggesting that larger crystal burden interfered with DNA purification (S1 Fig). One such post-centrifugation specimen (shown in Fig 4A) demonstrates a red-orange, sandy pellet, the “brick-layer’s dust” characteristic of amorphous urates. Confirmation of crystal composition was supported by microscopic analysis (Fig 4B) as well as chemical properties; these pellets could be dissolved by either heating to a temperature >60°C or adding sodium hydroxide. In a smaller subset of alkaline urine specimens, refrigeration or high-speed prolonged centrifugation resulted in a light-colored sandy pellet, which could be identified as amorphous phosphates by microscopy (Fig 4C). Chemical composition was confirmed by solubility in glacial acetic acid and resistance to dissolution with heating[45]. Other crystal forms were occasionally noted, such as the “envelope”-type crystals characteristic of calcium oxalate (Fig 4D inset), but these did not typically constitute any sizable portion of the crystalline material. We were able to minimize the appearance of crystalline salts through a combination of expedient processing (within 4 hours of sample acquisition), the avoidance of refrigeration, and optimization of sample size and centrifugation speed.

Fig 4. Urine storage and centrifugation conditions impact DNA extraction efficiency.

In a subset of urine samples, both refrigeration and high-speed centrifugation were associated with precipitation of varying crystals that interfered with DNA purification. (A) A single urine specimen before and after refrigeration and centrifugation at 5000 rcf. In the post-centrifugation specimen, a red-orange, sandy pellet was observed after centrifugation consistent with the “brick-layer’s dust” characteristic of amorphous urates. (B) The pellet seen in A was examined by light microscopy (x400 magnification), revealing disorganized amorphous urate crystals. (C) Amorphous phosphates from alkaline urine. (D) The “envelope”-type crystals characteristic of calcium oxalate could also be identified in urine (magnified in the inset picture), but did not constitute the majority of the crystalline material.

As amorphous urates and phosphates can inhibit individual steps in DNA purification and PCR amplification, we next sought to determine if varying processing volumes could minimize any impact of these salt contaminants on DNA purification and subsequent PCR amplification. In addition, we hypothesized that smaller sample volumes might be more effectively heated for thermal disruption. After combined enzymatic treatment and mechanical cell wall disruption, we subdivided samples into varying aliquot sizes for the two boil/freeze cycles, proteinase K digestion, and DNA isolation using a DNA-binding column. Volumes ranging from 25% to 80% (100–400 μl in 50 μl increments) of the total sample lysate were applied to the spin columns before washing and DNA elution. Small sequential increases in DNA yields were seen up to 250 μl, but then plateaued, without additional increase in DNA yields with larger volumes (S3A Fig).

These data suggested that a portion of the DNA in our samples was not either effectively digested or binding to the extraction column. We therefore attempted pooling of subdivided samples; sample lysates were divided into equal halves (~250 μl) and processed in parallel before column binding. Lysates were then either pooled onto a single column in two subsequent binding steps and eluted in a single elution or bound and eluted from separate columns and pooled after elution. Pooling of two 200–250 μl aliquots on a single DNA column provided the best DNA yields (S3B Fig).

Our optimized method outperforms previously described and commercial DNA isolation methods

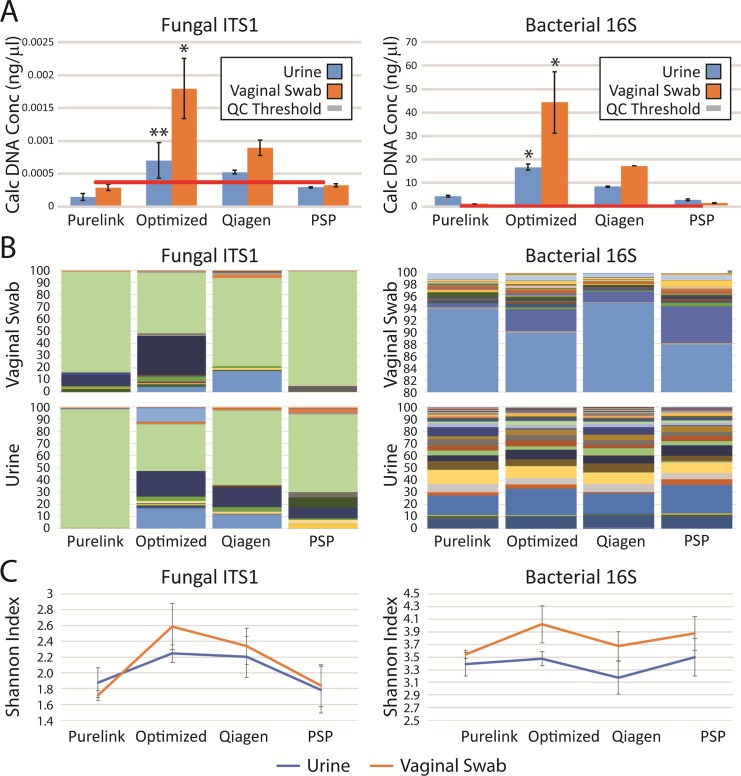

We then evaluated our method in comparison to several commercial DNA kits commonly used for microbial analysis. This optimized protocol yielded higher concentrations of DNA and greater species diversity for fungal DNA than identical samples processed with the PSP Spin Stool DNA Plus Kit, PureLink Microbiome DNA Purification Kit, and QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Fig 4). As the ideal goal of this method would be the simultaneous examination of both fungal and bacterial populations, we also assessed the utility of the optimized protocol in the isolation of bacterial DNA. Our protocol consistently outperformed commercial methods for the purification of fungal as well as bacterial DNA (Fig 5A). To assess the applicability of this protocol to other human commensal microbial communities, we analyzed a panel of vaginal swabs as well. Our protocol enhanced fungal and bacterial recovery from vaginal swabs significantly. While the method previously described for urine samples[5, 32] using Qiagen DNA isolation kits (Qiagen) was already better than the commercial kits tested, the optimized protocol increased the yield of fungal DNA approximately 200% (p<0.001) for vaginal swabs and 130% (p<0.005) for 30 ml urine samples. Bacterial yields differed even more profoundly, increasing yields approximately 240% for vaginal swabs and 200% for urine over levels seen with the best of previously described methods (p<0.001).

Fig 5. Our optimized DNA extraction method outperforms commercial methods.

We compared fungal (left) and bacterial (right) extraction and characterization after our optimized protocol in comparison to three commercial DNA preparation kits using standardized urine and vaginal swab samples. (A) Individual urine specimens were divided into equal aliquots of 30 ml each. DNA was isolated from each aliquot using the specified methods; this process was repeated in quadruplicate. Samples were assessed by qPCR for fungal (left) and bacterial (right) DNA. Calculated DNA concentrations were determined by normalization to a mixed fungal and bacterial standard with a known DNA concentration. *: P<0.001, **: P<0.005. (B, C) Samples were sequenced in quadruplicate by next generation sequencing for the ITS1 (left) and 16S (right) primers. (B) The stacked bar plots represent the mean relative abundances for the fungal (left) and bacterial (right) populations in individual sequencing runs. (C) Shannon diversity indices were calculated from the microbial populations resulting from NGS for each purification method.

The improved yields translated to an improved representation of urinary microbial community diversity as assessed by NGS. Qualitatively, a community of greater richness and evenness, as measured using the Shannon Diversity Index (Fig 5C), was seen; multiple taxa were absent or underrepresented in other purification methods (Fig 5B). The optimized method consistently resulted in the highest diversity of all methods. While these differences were not statistically significant, our optimized technique provides equivalent or improved bacterial and fungal community representation across multiple biological sample types.

Discussion

Extraction of DNA from fungal cells in urine has proven challenging for multiple reasons. Fungi are thought to be low abundance in most body sites and are structurally more robust and difficult to lyse. Multiple challenges in the identification and characterization of fungal species, such as incomplete annotation in common databases, inconsistent taxonomic classification, and variable conservation of the ribosomal locus across divisions of the fungal kingdom[46], complicate studies of fungi in any biologic niche. The combination of these problems with the technical difficulties of working with urine specimens has left previous explorations of the urinary fungal microbiota inadequate to examine anything more than a few, well-characterized species.[25] Given the experiences of others attempting fungal isolation in low biomass specimens, such as blood, we anticipated that substantial modifications of typical protocols used for the isolation of bacteria from urine would be necessary to assess adequately the fungal populations present. As optimal depth of sequencing requires the highest concentrations of DNA possible, we hypothesized that successful fungal DNA extraction for sequencing would require concentration of cellular material from larger volumes of urine, multiple disruption steps to break down fungal cell walls, and inactivation of the abundant PCR inhibitors present in urine. An iterative approach to the optimization of fungal DNA extraction confirmed these suspicions, with multiple modifications from commonly-used standard DNA extraction methods needed to provide consistent, good quality fungal DNA for sequencing-based assessments.

Sample size was very important. Approximately 40% of low volume specimens (e.g. 1 ml urine) did not provide adequate sequencing depth for analysis (<1000 reads per sample), while samples >10 ml consistently provided excellent depth of coverage in ~95% of samples. While this volume threshold had previously been suggested[44], our data provides objective confirmation that such a threshold is important for microbial analyses. Unexpected was the discovery that the best results were not associated with the largest, initial sample size, with an optimal sample size of 25–30 ml. We believe that this is due to an increase in urinary salts with larger sample volumes beyond a critical point that begins to interfere with DNA isolation. In this study, we utilized urine from asymptomatic subjects; patients with lower urinary tract symptoms tend to restrict fluids as a method to control their symptoms, resulting in urinary salt concentrations that are typically higher. Use of larger sample volumes of 50 ml or greater could unintentionally bias results, artifactually decreasing yields and diversity in patients with urinary symptoms. We selected the 25–30 ml volume to avoid this bias for routine use across study populations in the exploration of urinary symptom pathogenesis.

Interestingly, centrifugation speed made a substantial difference, with slower speeds yielding better results. While this result may seem counter-intuitive, our data suggest that this decrease in fungal DNA seen with higher centrifugation speeds and larger sample volumes is due to the accumulation of amorphous crystals common in urine that interfere with DNA extraction and amplification by PCR. While centrifugation at higher speeds may provide better pelleting of cellular matter, the lowest speed appears sufficient for this purpose; this is the speed routinely used to pellet eukaryotic cells. While lower concentration samples tended to demonstrate similar yields with centrifugation at 5000 rcf, the 1500 rcf centrifugation speed was more reliable across the population and was not associated with any significant loss of material in any samples tested. In addition, the lower speed reduces pelleting of microscopic crystals and de novo crystal formation seen at ultracentrifugation speeds. As we wanted to create a standardized protocol for all samples, we chose this lower speed. In addition, centrifugation at these speeds is readably achievable with most clinical centrifuges that can be found in outpatient centers, which may make rapid processing of samples in the clinical setting feasible. While it is possible that other methodologic variations, such as filter-based concentration methods or magnetic bead separations, could provide improved results, our initial attempts using these methods did not appear promising.

As anticipated, multiple cell wall disruption methods (thermal, mechanical, and enzymatic) provided much improved fungal DNA yields. An additional digestion with proteinase K was helpful at improving DNA quality as well, although the precise amount of enzyme was less important. The use of carrier DNA to enhance DNA column binding efficiency was crucial. Parallel processing of cell lysates in smaller batches with serial application of these samples to a single DNA binding column also improved yields. The individual improvements in fungal DNA extraction for each of these steps justified their inclusion into the optimized protocol.

The final optimized protocol (available at protocols.io) includes limited storage at room temperature prior to centrifugation of a 25–30 ml urine sample at 1500 rcf to pellet cellular material, followed by an initial enzymatic digestion in lyticase and lysozyme. Subsequent mechanical disruption using silica beads and thermal digestion at 95°C was followed by division of the sample into 2 smaller batches to allow an effective secondary digestion with proteinase K to inactivate any contaminating DNases. After addition of synthetic carrier DNA to each batch, sample DNA was subsequently isolated by binding to a commercial DNA-binding column. We attempted multiple other variations on our protocol that are not described in this paper, such as preheating the DNA elution buffer to 37°C or performing a second elution from the DNA-binding column in a small volume, as none of these possibilities made significant differences in the resulting DNA concentrations. Our results without these additional steps were sufficient for genomic sequencing.

One drawback to these additional steps is that this protocol takes significantly more time than the available commercial kits, 150–180 min in contrast to 75–90 min. The substantial improvement in the quality and quantity of isolated microbial DNA, however, is clear, consistently providing reliable DNA for NGS analyses of microbial populations.

The samples utilized as test specimens throughout this paper were voided. Contamination from nearby sites, such as skin, urethra, and vagina (in women), can contribute heavily to the microbial content of voided samples[44]. When compared directly (Fig 3), fungal levels in samples from women were 2-3- fold higher than those seen for men. While this could reflect a difference in the urinary fungal content between genders that may be a product of the differing anatomy of the lower urinary tract between genders, it may also merely reflect differences in contamination from nearby urogenital sites. As a result, this paper does not seek to make conclusions about the composition of the urinary mycobiome, but instead sought to explore the solutions needed to characterize microbial content from urine specimens. Larger scale studies, which are currently underway, using a multitude of samples will be needed to explore the urinary mycobiome. However, while the samples used in this study were voided in origin, we have since confirmed that this enhanced protocol is successful at producing sufficient quality fungal DNA to obtain good depth of sequencing from a limited number of catheterized urine samples and those obtained by suprapubic aspirate.

For microbial populations of low abundance, as presumed for the urinary tract, maximizing the quantity of template DNA for analysis is extremely important. When DNA quantities are barely in the range of detection, small variations in sample quantity or quality or even minor fluctuations in physiologic conditions may result in large misleading population shifts. If certain benign urologic conditions are associated with changes in the overall abundance of fungi in urine, as has been suggested for UCPPS,[25] then methods that fail to adequately represent the population at the lower, baseline levels will underrepresent the populations present in these circumstances. It is likely in that situation that culture-independent microbial analyses will incorrectly identify the upregulation or novel appearance of particular taxa, providing misleading conclusions about disease pathophysiology. These problems are compounded by the fact that urine composition and concentration is highly variable, even within a single individual. Certain disease conditions are associated with systematically smaller void volumes, which might also significantly bias such results. The increased DNA concentration and quality achieved using this optimized approach seek to minimize these biases and provide the most accurate results in the use of sequencing-based methods to define the urinary mycobiome.

It has been widely recognized for bacterial DNA extraction that different sample preparation and DNA extraction protocols can produce dramatically different results.[47–50] Protocols utilizing mechanical and enzymatic disruption steps have consistently given the best representations of bacterial community structure, but in no case have the obtained results provided completely accurate representations of standardized samples.[50] In fungal studies,[51] optimal conditions vary for individual fungal species; therefore, while standardized methods are generally useful for fungal and bacterial DNA extraction from biologic specimens, every method will have some bias in extraction efficiency. No single extraction method is reliable and optimal for all species in all specimens. While our results from a range of subjects and specimens confirmed the efficacy of this optimized protocol in aggregate, there were individual variations in fungal community patterns. Our optimized protocol as defined was not always the most effective for every subject assessed. The greatest variations occurred with centrifugation conditions; it is likely that for subjects for whom there is a lower urinary salt content there would be improved results with higher centrifugation speeds. Such biases are inevitable for all stages in the process of culture-independent sequencing-based identification of microorganisms. It remains important to keep these biases in mind when interpreting results, as well as to confirm results through multiple methodologies.

In conclusion, we present a method for microbial DNA isolation that results in a better representation of the overall fungal and bacterial populations, both in terms of the population diversity as well as identification of low abundance taxa that are lost with less sensitive methods. All of these benefits appear to occur without a significant loss in bacterial community representation, making this the best available method for microbial analyses of urine samples.

Conclusion

Studies examining urinary fungal populations have been limited by the inability to consistently isolate the microbial DNA from low biomass urinary samples. This report describes an optimized protocol for the analysis of urinary fungi that is also highly effective for the concurrent analysis of urinary bacterial populations. The simultaneous and efficient extraction of fungal and bacterial DNA from urine for use in culture-independent microbial analyses is thus possible with this refined technique, providing more reliable methods for the detection and exploration of multiple microbial kingdoms from a single specimen.

Supporting information

In individual subjects, lower centrifugation speeds are associated with increased total and fungal DNA yields from urine samples. Urine samples from eight subjects, four male (in blue) and four female (in pink), were divided into three 30 ml samples and subjected to centrifugation at the indicated speeds. (A) Total DNA yields from each condition were measured using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer and expressed at a fold increase over the levels seen in the 16000 rcf sample. (B) Fungal DNA yields from these variations in centrifugation speed were calculated by quantitative PCR using primers specific for the 18S ribosomal DNA locus, then scaled across all samples. Values are expressed as a heat map, with bright red signifying the highest yields and black the lowest yields across all samples.

(TIF)

Large volume urine samples were divided into eight 30 ml samples. After adding the indicated amount of sodium phosphate to each sample, each specimen was processed according to the optimal DNA isolation protocol. (A) Fungal and (B) bacterial DNA yields from these samples were calculated by quantitative PCR in triplicate. Profound decreases in microbial DNA yields, despite equal starting DNA quantities, occur with increasing phosphate concentrations. This decrease is directly dependent on phosphate concentration, as seen in plots of the log of the phosphate concentration against the log of the fungal (C) and bacterial (D) DNA yields.

(TIF)

Standardized urine samples from 4 subjects were pelleted and processed using the optimized purification protocol for enzymatic treatment and cell wall disruption. (A) Prior to the addition of proteinase K, varying quantities of the total sample lysate were transferred to new tubes for digestion and DNA column binding. Lysate quantities ≥250 μl provided equivalent yields. (B) Prior to the addition of proteinase K, sample lysates were divided into 250 μl aliquots. Processing of a single 250 μl aliquot (No pooling) was compared to the results if the lysate was split into two aliquots and processed in parallel, then later pooled on either a single DNA-binding column and eluted as a single sample (1 column) or purified separately on two columns, eluted independently and then pooled (2 columns). Control samples were processed in parallel and did not have any input cellular material.

(TIF)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

MAPP I and II Research Network Study Group

MAPP Network Executive Committee

J. Quentin Clemens, MD, FACS, MSci, Network Chair, 2013-

Philip Hanno, MD

Ziya Kirkali, MD

John W. Kusek, PhD

J. Richard Landis, PhD

M. Scott Lucia, MD

Robert M. Moldwin, MD

Chris Mullins, PhD

Michel A. Pontari, MD

University of Colorado Denver Tissue Analysis & Technology Core

M. Scott Lucia, MD, Core Dir.

Adrie van Bokhoven, PhD, Co-Dir.

Andrea A. Osypuk, BS

Robert Dayton, Jr

Chelsea S. Triolo, BS

Karen R. Jonscher, PhD

Holly T. Sullivan, BS

R. Storey Wilson, MS

Zachary D. Grasmick, BS

National Institutes of Diabetes & Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Chris Mullins, PhD

John W. Kusek, PhD

Ziya Kirkali, MD

Tamara G. Bavendam, MD

University of Pennsylvania Data Coordinating Core

J. Richard Landis, PhD, Core Dir.

Ted Barrell, BA

Ro-Pauline Doe, BA

John T. Farrar, MD, MSCE, PhD

Melissa Fernando, MPH

Laura Gallagher, MPH, CCRP

Philip Hanno, MD

Xiaoling Hou, MS

Tamara Howard, MPH

Thomas Jemielita, MS

Natalie Kuzla, MA

Robert M. Moldwin, MD

Craig Newcomb, MS

Michel A. Pontari, MD

Nancy Robinson-Garvin, PhD

Sandra Smith, AS

Alisa Stephens-Shields, PhD

Yanli Wang, MS

Xingmei Wang, MS

DISCOVERY SITES

Northwestern University

David J. Klumpp, PhD, Co-Dir. Anthony J. Schaeffer, MD, Co-Dir.

Apkar (Vania) Apkarian, PhD

Christina Arroyo

Michael Bass, PhD

David Cella, PhD

Melissa A. Farmer, PhD

Colleen Fitzgerald, MD

Richard Gershon, PhD

James W. Griffith, PhD

Charles J. Heckman II, PhD

Mingchen Jiang, PhD

Laurie Keefer, PhD

Robert Lloyd, PhD

Darlene S. Marko, RN, BSN, CCRC

Jean Michniewicz

Richard Miller, PhD

Todd Parrish, PhD

Frank Tu, MD, MPH

Ryan Yaggi

University of California, LA PAIN Neuroimaging Core

Emeran A. Mayer, MD, Co-Dir.

Larissa V. Rodríguez, MD, Co-Dir.

Jeffry Alger, PhD

Cody P. Ashe-McNalley

Ben Ellingson, PhD

Nuwanthi Heendeniya

Lisa Kilpatrick, PhD

Cara, Kulbacki

Jason Kutch, PhD

Jennifer S. Labus, PhD

Bruce D. Naliboff, PhD

Fornessa Randal

Suzanne R. Smith, RN, NP

University of Iowa

Karl J. Kreder, MD, MBA, Dir.

Catherine S. Bradley, MD, MSCE

Mary Eno, RN, RA

Kris Greiner, BA

Yi Luo, PhD, MD

Susan K. Lutgendorf, PhD

Michael A. O’Donnell, MD

Barbara Ziegler, BA

Andrew Schrepf, PhD

Isabelle Hardy, MBA

Vince Magnotta, PhD

Brad Erickson, MD

University of Michigan

Daniel J. Clauw, MD, Co-Dir.; Network Chair, 2008–2013

J. Quentin Clemens, MD, FACS, MSci, Co-Dir.; Network Chair, 2013-

Suzie As-Sanie, MD

Sandra Berry, MA

Clara Grayhack,

Megan E. Halvorson, BS, CCRP

Richard Harris, PhD

Steve Harte, PhD

Eric Ichesco, BS

Ann Oldendorf, MD

Katherine A. Scott, RN, BSN

David A. Williams, PhD

University of Washington, Seattle

Dedra Buchwald, MD, Dir.

Niloofar Afari, PhD, UCSD

Tamara Bacus, BS

Todd Edwards, PhD

John Krieger, MD

Kenneth Maravilla, MD

Jane Miller, MD

Donald Patrick, PhD

Xiaoyan Qin, PhD

Stephanie Richey, BS

Rosana Risques, PhD

Kelly Robertson, BS

Susan O. Ross, RN, MN

Roberta Spiro, MS

Eric Strachan, PhD

TJ Sundsvold, MPH

Suzette Sutherland, MD

Claire C. Yang, MD

Washington University, St. Louis

Gerald L. Andriole, MD, Co-Dir., PI

H. Henry Lai, MD, Co-Dir., PI

Rebecca L. Bristol, BA, BS

Robert W. Gereau IV, PhD,

Barry A. Hong, PhD, FAACP

Aleksandra P. Klim, RN, MHS, CCRC

Siobhan Sutcliffe, PhD, ScM, MHS

Joel Vetter

David G. Song

Melissa Milbrandt

Simon Haroutounian, PhD

Pooja Vijairania

Kaveri Parker (Chaturvedi)

Tran Hung

Graham Colditz, MD, PH

Vivien C. Gardner, RN, BSN

Jeffrey P Henderson, MD, PhD

Theresa M. Spitznagle, PT, DPT, WCS

Ratna Pakpahan, MHA

Aimee James PhD, MPH

Yan Yan

Marvin Epolian Langston

Barry Hong, PhD

Susan Mueller

Jan Crowley

Sherri Vogt

Scott Hultgren, PhD

Nang Nguyen, PhD

Gabriel Blasche

Chang Shen Qiu, PhD

Lori Cupps

Song Bok

Thomas M. Hooten, MD [U. Miami]

Lucy Grullon [U Miami]

Nadege Atis [U Miami]

Timothy J. Ness, MD, PhD [UAB]

Georg Deutsch, PhD [UAB]

Jan Den Hollander, PhD [UAB]

Beverly D. Corbitt, RN [UAB]

Laurence Bradley, PhD [UAB]

Carol S. North, MD, MPE, [UTSW]

Dana Downs, MA [UTSW]

NON-RECRUITING DISCOVERY SITES

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

Jennifer Anger, MD, MPH

James Ackerman, MA

A. Lenore Ackerman, MD, PhD

Jeena Cha, BS, CCRP

Karyn Eilber, MD

Michael Freeman, PhD

Vincent Funari, PhD

Jayoung Kim, PhD

Jennifer Van Eyk, PhD

Wei Yang, PhD

Harvard Medical School/Boston Children’s Hospital

Marsha A. Moses, PhD, Dir.

Andrew C. Briscoe

David Briscoe, MD

Adam Curatolo, BA

John Froehlich, PhD

Richard S. Lee, MD

Monisha Sachdev, BS

Keith R. Solomon, PhD

Hanno Steen, PhD

Stanford University

Sean Mackey, MD, PhD, Dir.

Epifanio Bagarinao, PhD

Lauren C. Foster, BA

Emily Hubbard, BA

Kevin A. Johnson, PhD, RN

Katherine T. Martucci, PhD

Rebecca L. McCue, BA

Rachel R. Moericke, MA

Aneesha Nilakantan, BA

Noorulain Noor, BS

Queens University

J. Curtis Nickel, MD, FRCSC, Dir.

Garth D. Ehrlich, PhD, [Drexel COM]

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files. These are listed at the end of the manuscript. The protocol has been posted to protocols.io and all other relevant data are included in the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by: Urology Care Foundation Grant (ALA), https://www.urologyhealth.org/; Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain (MAPP) Network (1U01DK103260; JK, JTA, MRF), www.mappnetwork.org. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Siddiqui H, Nederbragt AJ, Lagesen K, Jeansson SL, Jakobsen KS. Assessing diversity of the female urine microbiota by high throughput sequencing of 16S rDNA amplicons. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:244 10.1186/1471-2180-11-244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearce MM, Zilliox MJ, Rosenfeld AB, Thomas-White KJ, Richter HE, Nager CW, et al. The female urinary microbiome in urgency urinary incontinence. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2015;213(3):347 e1-11. Epub 2015/07/27. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe AJ, Brubaker L. "Sterile Urine" and the Presence of Bacteria. Eur Urol. 2015;68(2):173–4. Epub 2015/03/17. 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.02.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sogin ML, Morrison HG, Huber JA, Mark Welch D, Huse SM, Neal PR, et al. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored "rare biosphere". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(32):12115–20. Epub 2006/08/02. 10.1073/pnas.0605127103 PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1524930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearce MM, Hilt EE, Rosenfeld AB, Zilliox MJ, Thomas-White K, Fok C, et al. The female urinary microbiome: a comparison of women with and without urgency urinary incontinence. MBio. 2014;5(4):e01283–14. Epub 2014/07/10. 10.1128/mBio.01283-14 PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4161260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas-White KJ, Hilt EE, Fok C, Pearce MM, Mueller ER, Kliethermes S, et al. Incontinence medication response relates to the female urinary microbiota. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(5):723–33. Epub 2015/10/02. 10.1007/s00192-015-2847-x PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5119460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilt EE, McKinley K, Pearce MM, Rosenfeld AB, Zilliox MJ, Mueller ER, et al. Urine is not sterile: use of enhanced urine culture techniques to detect resident bacterial flora in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(3):871–6. Epub 2013/12/29. 10.1128/JCM.02876-13 PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3957746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khasriya R, Sathiananthamoorthy S, Ismail S, Kelsey M, Wilson M, Rohn JL, et al. Spectrum of bacterial colonization associated with urothelial cells from patients with chronic lower urinary tract symptoms. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(7):2054–62. Epub 2013/04/19. 10.1128/JCM.03314-12 PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3697662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fouts DE, Pieper R, Szpakowski S, Pohl H, Knoblach S, Suh MJ, et al. Integrated next-generation sequencing of 16S rDNA and metaproteomics differentiate the healthy urine microbiome from asymptomatic bacteriuria in neuropathic bladder associated with spinal cord injury. J Transl Med. 2012;10:174 Epub 2012/08/30. 10.1186/1479-5876-10-174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groah SL, Perez-Losada M, Caldovic L, Ljungberg IH, Sprague BM, Castro-Nallar E, et al. Redefining Healthy Urine: A Cross-Sectional Exploratory Metagenomic Study of People With and Without Bladder Dysfunction. J Urol. 2016;196(2):579–87. Epub 2016/01/26. 10.1016/j.juro.2016.01.088 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas-White KJ, Kliethermes S, Rickey L, Lukacz ES, Richter HE, Moalli P, et al. Evaluation of the urinary microbiota of women with uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2017;216(1):55 e1- e16. Epub 2016/08/09. 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.07.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siddiqui H, Lagesen K, Nederbragt AJ, Jeansson SL, Jakobsen KS. Alterations of microbiota in urine from women with interstitial cystitis. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:205 Epub 2012/09/15. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson DE, Van Der Pol B, Dong Q, Revanna KV, Fan B, Easwaran S, et al. Characteristic male urine microbiomes associate with asymptomatic sexually transmitted infection. PloS one. 2010;5(11):e14116 Epub 2010/12/03. 10.1371/journal.pone.0014116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fok CS, Gao X, Lin H, Thomas-White KJ, Mueller ER, Wolfe AJ, et al. Urinary symptoms are associated with certain urinary microbes in urogynecologic surgical patients. Int Urogynecol J. 2018. Epub 2018/08/18. 10.1007/s00192-018-3732-1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Chen Z, Guo R, Chen N, Lu H, Huang S, et al. Correlation between gastrointestinal fungi and varying degrees of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;70(4):492–8. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.04.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang E, Tanaka T, Tajima M, Tsuboi R, Nishikawa A, Sugita T. Characterization of the skin fungal microbiota in patients with atopic dermatitis and in healthy subjects. Microbiol Immunol. 2011;55(9):625–32. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2011.00364.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sokol H, Leducq V, Aschard H, Pham HP, Jegou S, Landman C, et al. Fungal microbiota dysbiosis in IBD. Gut. 2016. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310746 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoarau G, Mukherjee PK, Gower-Rousseau C, Hager C, Chandra J, Retuerto MA, et al. Bacteriome and Mycobiome Interactions Underscore Microbial Dysbiosis in Familial Crohn's Disease. MBio. 2016;7(5). 10.1128/mBio.01250-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chehoud C, Albenberg LG, Judge C, Hoffmann C, Grunberg S, Bittinger K, et al. Fungal Signature in the Gut Microbiota of Pediatric Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(8):1948–56. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delhaes L, Monchy S, Frealle E, Hubans C, Salleron J, Leroy S, et al. The airway microbiota in cystic fibrosis: a complex fungal and bacterial community—implications for therapeutic management. PloS one. 2012;7(4):e36313 10.1371/journal.pone.0036313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sellart-Altisent M, Torres-Rodriguez JM, Gomez de Ana S, Alvarado-Ramirez E. [Nasal fungal microbiota in allergic and healthy subjects]. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2007;24(2):125–30. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knutsen AP, Bush RK, Demain JG, Denning DW, Dixit A, Fairs A, et al. Fungi and allergic lower respiratory tract diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(2):280–91; quiz 92–3. 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.970 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paulino LC, Tseng CH, Blaser MJ. Analysis of Malassezia microbiota in healthy superficial human skin and in psoriatic lesions by multiplex real-time PCR. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008;8(3):460–71. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2008.00359.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Koning HD, Rodijk-Olthuis D, van Vlijmen-Willems IM, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Schalkwijk J, et al. A comprehensive analysis of pattern recognition receptors in normal and inflamed human epidermis: upregulation of dectin-1 in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(11):2611–20. 10.1038/jid.2010.196 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nickel JC, Stephens A, Landis JR, Mullins C, van Bokhoven A, Lucia MS, et al. Assessment of the Lower Urinary Tract Microbiota during Symptom Flare in Women with Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: A MAPP Network Study. J Urol. 2016;195(2):356–62. Epub 2015/09/28. 10.1016/j.juro.2015.09.075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu CM, Kachur S, Dwan MG, Abraham AG, Aziz M, Hsueh PR, et al. FungiQuant: a broad-coverage fungal quantitative real-time PCR assay. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:255 Epub 2012/11/10. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–8. Epub 2008/06/13. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McHardy IH, Goudarzi M, Tong M, Ruegger PM, Schwager E, Weger JR, et al. Integrative analysis of the microbiome and metabolome of the human intestinal mucosal surface reveals exquisite inter-relationships. Microbiome. 2013;1(1):17 Epub 2014/01/24. 10.1186/2049-2618-1-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnetjournal. 2011;17(1):10–2. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7(5):335–6. Epub 2010/04/13. 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang J, Iliev ID, Brown J, Underhill DM, Funari VA. Mycobiome: Approaches to analysis of intestinal fungi. J Immunol Methods. 2015;421:112–21. Epub 2015/04/22. 10.1016/j.jim.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfe AJ, Toh E, Shibata N, Rong R, Kenton K, Fitzgerald M, et al. Evidence of uncultivated bacteria in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(4):1376–83. Epub 2012/01/27. 10.1128/JCM.05852-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinsey GC, Paterson RR, Kelley J. Methods for the determination of filamentous fungi in treated and untreated waters. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;85 Suppl 1:214S–24S. Epub 1998/12/01. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1998.tb05301.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Deventer AJ, Goessens WH, van Belkum A, van Vliet HJ, van Etten EW, Verbrugh HA. Improved detection of Candida albicans by PCR in blood of neutropenic mice with systemic candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(3):625–8. Epub 1995/03/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldschmidt P, Degorge S, Merabet L, Chaumeil C. Enzymatic treatment of specimens before DNA extraction directly influences molecular detection of infectious agents. PloS one. 2014;9(6):e94886 Epub 2014/06/18. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gill C, van de Wijgert JH, Blow F, Darby AC. Evaluation of Lysis Methods for the Extraction of Bacterial DNA for Analysis of the Vaginal Microbiota. PloS one. 2016;11(9):e0163148 Epub 2016/09/20. 10.1371/journal.pone.0163148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williamson EC, Leeming JP, Palmer HM, Steward CG, Warnock D, Marks DI, et al. Diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in bone marrow transplant recipients by polymerase chain reaction. Br J Haematol. 2000;108(1):132–9. Epub 2000/01/29. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haugland RA, Heckman JL, Wymer LJ. Evaluation of different methods for the extraction of DNA from fungal conidia by quantitative competitive PCR analysis. J Microbiol Methods. 1999;37(2):165–76. Epub 1999/08/13. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lech T, Sygula-Cholewinska J, Szostak-Kot J. An economical and combined method for rapid and efficient isolation of fungal DNA. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13(4):10779–86. Epub 2014/12/20. 10.4238/2014.December.18.19 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Burik JA, Schreckhise RW, White TC, Bowden RA, Myerson D. Comparison of six extraction techniques for isolation of DNA from filamentous fungi. Med Mycol. 1998;36(5):299–303. Epub 1999/03/13. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffiths LJ, Anyim M, Doffman SR, Wilks M, Millar MR, Agrawal SG. Comparison of DNA extraction methods for Aspergillus fumigatus using real-time PCR. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55(Pt 9):1187–91. Epub 2006/08/18. 10.1099/jmm.0.46510-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fredricks DN, Smith C, Meier A. Comparison of six DNA extraction methods for recovery of fungal DNA as assessed by quantitative PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(10):5122–8. Epub 2005/10/07. 10.1128/JCM.43.10.5122-5128.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beranek M, Sirak I, Vosmik M, Petera J, Drastikova M, Palicka V. Carrier molecules and extraction of circulating tumor DNA for next generation sequencing in colorectal cancer. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove). 2016;59(2):54–8. Epub 2016/08/16. 10.14712/18059694.2016.54 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bao Y, Al KF, Chanyi RM, Whiteside S, Dewar M, Razvi H, et al. Questions and challenges associated with studying the microbiome of the urinary tract. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(2):33 Epub 2017/02/22. 10.21037/atm.2016.12.14 PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5300849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hallson PC, Rose GA. Measurement of calcium phosphate crystalluria: influence of pH and osmolality and invariable presence of oxalate. Br J Urol. 1989;64(5):458–62. Epub 1989/11/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ackerman AL, Underhill DM. The mycobiome of the human urinary tract: potential roles for fungi in urology. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(2):31 Epub 2017/02/22. 10.21037/atm.2016.12.69 PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5300854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghannoum MA, Jurevic RJ, Mukherjee PK, Cui F, Sikaroodi M, Naqvi A, et al. Characterization of the oral fungal microbiome (mycobiome) in healthy individuals. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(1):e1000713 Epub 2010/01/15. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000713 PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2795202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eisner ER. Transcoronal approach to the palatal root of the maxillary fourth premolar in the dog. J Vet Dent. 1990;7(2):14–5. Epub 1990/04/01. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dollive S, Peterfreund GL, Sherrill-Mix S, Bittinger K, Sinha R, Hoffmann C, et al. A tool kit for quantifying eukaryotic rRNA gene sequences from human microbiome samples. Genome Biol. 2012;13(7):R60 Epub 2012/07/05. 10.1186/gb-2012-13-7-r60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan S, Cohen DB, Ravel J, Abdo Z, Forney LJ. Evaluation of methods for the extraction and purification of DNA from the human microbiome. PloS one. 2012;7(3):e33865 Epub 2012/03/30. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rittenour WR, Park JH, Cox-Ganser JM, Beezhold DH, Green BJ. Comparison of DNA extraction methodologies used for assessing fungal diversity via ITS sequencing. J Environ Monit. 2012;14(3):766–74. Epub 2012/01/11. 10.1039/c2em10779a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

In individual subjects, lower centrifugation speeds are associated with increased total and fungal DNA yields from urine samples. Urine samples from eight subjects, four male (in blue) and four female (in pink), were divided into three 30 ml samples and subjected to centrifugation at the indicated speeds. (A) Total DNA yields from each condition were measured using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer and expressed at a fold increase over the levels seen in the 16000 rcf sample. (B) Fungal DNA yields from these variations in centrifugation speed were calculated by quantitative PCR using primers specific for the 18S ribosomal DNA locus, then scaled across all samples. Values are expressed as a heat map, with bright red signifying the highest yields and black the lowest yields across all samples.

(TIF)

Large volume urine samples were divided into eight 30 ml samples. After adding the indicated amount of sodium phosphate to each sample, each specimen was processed according to the optimal DNA isolation protocol. (A) Fungal and (B) bacterial DNA yields from these samples were calculated by quantitative PCR in triplicate. Profound decreases in microbial DNA yields, despite equal starting DNA quantities, occur with increasing phosphate concentrations. This decrease is directly dependent on phosphate concentration, as seen in plots of the log of the phosphate concentration against the log of the fungal (C) and bacterial (D) DNA yields.

(TIF)

Standardized urine samples from 4 subjects were pelleted and processed using the optimized purification protocol for enzymatic treatment and cell wall disruption. (A) Prior to the addition of proteinase K, varying quantities of the total sample lysate were transferred to new tubes for digestion and DNA column binding. Lysate quantities ≥250 μl provided equivalent yields. (B) Prior to the addition of proteinase K, sample lysates were divided into 250 μl aliquots. Processing of a single 250 μl aliquot (No pooling) was compared to the results if the lysate was split into two aliquots and processed in parallel, then later pooled on either a single DNA-binding column and eluted as a single sample (1 column) or purified separately on two columns, eluted independently and then pooled (2 columns). Control samples were processed in parallel and did not have any input cellular material.

(TIF)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files. These are listed at the end of the manuscript. The protocol has been posted to protocols.io and all other relevant data are included in the manuscript.