Abstract

Background

Bisphosphonates form part of standard therapy for hypercalcemia and the prevention of skeletal events in some cancers. However, the role of bisphosphonates in pain relief for bony metastases remains uncertain.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of bisphosphonates for the relief of pain from bone metastases.

Search methods

MEDLINE (1966 to 1999), EMBASE (1980 to 1999), CancerLit (1966 to 1999), T he Cochrane L ibrary (Issue 1, 2000) and the Oxford Pain Database were searched using the strategy devised by the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Group with additional terms 'diphosphonate', 'bisphosphonate', 'multiple myeloma' and 'bone neoplasms'. (Last search: January 2000).

Selection criteria

Randomized trials of bisphosphonates compared with open, blinded, or different doses/types of bisphosphonates in cancer patients were included where pain and/or analgesic consumption were outcome measures. Studies where pain was reported only by observers were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

Article eligibility, quality assessment and data extraction were undertaken by both review authors. The proportions of patients with pain relief at 4, 8 and 12 weeks were assessed. The proportion of patients with analgesic reduction, the mean pain score, mean analgesic consumption, adverse drug reactions, and quality of life data were compared as secondary outcomes.

Main results

Thirty randomized controlled studies (21 blinded, four open and five active control) with a total of 3682 subjects were included. For each outcome, there were few studies with available data. For the proportion of patients with pain relief (eight studies) pooled data showed benefits for the treatment group, with an NNT at 4 weeks of 11[95% CI 6‐36] and at 12 weeks of 7 [95% CI 5‐12]. In terms of adverse drug reactions, the NNH was 16 [95% CI 12‐27] for discontinuation of therapy. Nausea and vomiting were reported in 24 studies with a non‐significant trend for greater risk in the treatment group. One study showed a small improvement in quality of life for the treatment group at 4 weeks. The small number of studies in each subgroup with relevant data limited our ability to explore the most effective bisphosphonates and their relative effectiveness for different primary neoplasms.

Authors' conclusions

There is evidence to support the effectiveness of bisphosphonates in providing some pain relief for bone metastases. There is insufficient evidence to recommend bisphosphonates for immediate effect; as first line therapy; to define the most effective bisphosphonates or their relative effectiveness for different primary neoplasms. Bisphosphonates should be considered where analgesics and/or radiotherapy are inadequate for the management of painful bone metastases.

Plain language summary

Bisphosphonates for the relief of pain secondary to bone metastases

Bisphosphonates give some relief from pain caused by cancer that has invaded bones. Patients with cancer that has spread to the bone frequently have pain. Pain control is an important part of cancer management. Bisphosphonates are medicines that affect the way bone develops, and are proving useful in treating patients with cancer that has invaded the bone (metastasis). This review looked at the effect of bisphosphonates on pain caused by bone metastases. Bisphosphonates do have some effect but are not as useful as either strong analgesics (such as morphine) or radiotherapy. However, where other methods of pain relief are inadequate, the addition of bisphosphonates can be beneficial. Bisphosphonates can cause nausea and vomiting.

Background

Bisphosphonates are structural analogues of pyrophosphates, a naturally occurring component of bone crystal deposition. Different side chain modification of the basic pyrophosphate structure gives rise to the different generations of bisphosphonates, with different levels of activity. The mode of action of bisphosphonates are multiple. Predominantly, through strong affinity to bone, bisphosphonates provide physico‐chemical protection by absorbing calcium phosphate, suppressing the normal functioning of mature osteoclasts, and prevent osteoclast precursors maturing.

Bisphosphonates have been shown to be effective in the management of patients with hypercalcemia (Body 1996), securing their place as standard therapy for this condition. More recently, bisphosphonates have been shown to be effective in decreasing morbidity related to bony metastasis in patients with breast cancer (Lipton 1997; CCOPGI 1999) and multiple myeloma (Bloomfield 1998). The available evidence has significantly changed the management of these patients in recent years, with the incorporation into standard clinical practice the use of bisphosphonates in breast cancer patients with early bone metastasis and newly diagnosed myeloma patients aimed to minimize the morbidity related to bony metastasis. In addition to the long‐term effect of preventing tumor deposits into bone, bisphosphonates may also reduce pain arising from bone metastasis (Mannix 2000; Johnson 2001).

Pain is often a devastating symptom in the management of cancer patients. Analgesics have been indispensable in the management of cancer pain and are an integral part of cancer pain management. Despite the use of increasingly versatile and potent analgesics, co‐analgesics, and other means such as radiotherapy, there remain situations where the achievement of adequate pain control is limited. In these situations the use of bisphosphonates in relieving pain from bone metastases is gaining popularity, although remains a subject of debate.

Objectives

The primary objective of this review is to determine the effectiveness of bisphosphonates for pain relief in patients with painful bony metastases.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only studies using a randomized design published in full were included. (Abstracts were excluded). It was our intention to include all studies where the effect of bisphosphonate on cancer pain was assessed. We therefore interpreted this criterion broadly and accepted studies with any pain or analgesic outcome measures. Whether pain was an eligibility criterion or not would have an impact on the proportion of patients eligible to experience pain relief. Pain expressed by observers only (e.g., physicians) has well‐documented discordance with patient reported pain scores (Cleeland 1989; Sutherland 1988; Van der Does 1989). Only studies with subject (patient) reported pain were included. Studies where the source of the pain scores was not specified were included.

Sensitivity analyses were used to assess the impact of:

pain as an eligibility criterion in the primary studies

pain specified as being patient‐reported

Types of participants

Clinical trials including patients with bony metastases from any primary neoplasms were eligible for inclusion.

Types of interventions

Reports describing the use of bisphosphonates (oral or intravenous) were eligible for inclusion. The control arm could comprise placebo or open controls. Studies where different doses of bisphosphonates were compared (i.e., active controls) were also included but were analyzed separately. The use of antineoplastic therapy (chemotherapy, radiotherapy) did not constitute exclusion from the review provided these treatments were available uniformly to study participants in both treatment arms.

Types of outcome measures

The types of outcome measures compared between the study and control groups were:

Primary outcomes

Proportion of patients with pain relief.

Secondary outcomes

Mean or median pain score.

Adverse drug reactions.

Quality of life.

Other pain and analgesic outcome measures reported in the trials.

Search methods for identification of studies

Studies for inclusion in this review were identified from:

Electronic databases

MEDLINE (1966 to 1999)

EMBASE (1980 to 1999)

CancerLit (1966 to 1999)

The Cochrane Library (CCTR) (2000)

the Oxford Pain Database (1950 to 1994)

The search strategy devised by the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Group for identifying randomized trials was used, with the addition of the following terms:

diphosphonate*

bisphosphonate*

generic and trade names of bisphosphonates

multiple myeloma

bone neoplasms

The RCT filter developed by Dickersin et al (Dickersin 1994) was applied.

Reference lists Reference lists from published trial reports and reviews were searched for potential studies for inclusion in the review.

No language restriction was applied to the search strategy.

Data collection and analysis

Article selection

Articles identified through the search strategy were assessed independently by both authors. Review authors were not blinded to the source or author of the document for article selection, data extraction or quality assessment.

Classification of trials by type of control arm

Studies with blinded placebo control arms produce less bias than over open controls (Schulz 1996). Studies employing active controls were included in order to explore whether a dose response relationship existed. If a dose response relationship was found, this would provide additional evidence of treatment effectiveness. Studies employing active controls were analyzed separately to address the dose response relationship. The effect of blinded versus open controls on the analysis was explored through sensitivity analysis.

Special considerations for interpreting selected outcomes of interest

1. Proportion of patients with pain relief

This was chosen as the primary outcome for this review as it was most suited for quantitative systematic review analysis and allowed the calculation of odds ratios, the pooling of data, and was amenable to analyses based on the intention‐to‐treat principle. In adopting this dichotomous outcome approach, it should be noted that it is sensitive to how the pain response was defined.

2. Mean or median pain score between study arms post treatment and mean analgesic consumption

This is a summary statistic that is commonly used in the reporting of pain trials but needs careful interpretation. In studies where the sample sizes are large, differences may be statistically significant without being clinically significant. The level of pain experienced by patients prior to the commencement of the intervention is rarely identical between study arms. This parameter is not amenable to an intention‐to‐treat analysis when the primary trialists did not use this approach in their reporting. Standard deviations are rarely reported, limiting the ability to use this as the summary statistic for quantitative analysis.

3. Analgesic endpoints

Analgesia is an unavoidable confounder in trials of this kind. As secondary outcomes, we chose to extract data regarding:

the proportion of patients with analgesic reduction, and

mean or median analgesic consumption.

The methodological considerations for the interpretation of these parameters are similar to those discussed above in relation to pain.

4. Adverse drug reactions

Reporting of adverse drug reactions was variable across the trials. Where available, similar descriptors were pooled. In general, the time frame in which adverse reactions were experienced was not specified.

5. Quality of life

Qualitative comparisons of available data were used.

6. Other endpoints

Clinical outcomes reported in addition to those selected as secondary outcomes for this review are tabulated and described in Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4.

1. Included studies by primary disease site.

| STUDY | BREAST | PROSTATE | MULTIPLE MYELOMA | LUNG | ANY PRIMARY |

| BLINDED STUDIES | |||||

| Theriault 1999 | x | ||||

| Brinkler 1998 | x | ||||

| Piga 1998 | x | ||||

| Vinholes 1997a | x | ||||

| Strang 1997 | x | ||||

| Kylmala 1997 | x | x | |||

| Ernst 1997* | x | ||||

| Hultborn 1996 | x | ||||

| Hortobagyi 1996 | x | ||||

| Berenson 1996 | x | ||||

| Robertson 1995 | x | ||||

| O'Rourke 1995* | x | ||||

| Daragon 1993 | x | ||||

| Lahtinen 1992 | x | ||||

| Elomaa 1992 | x | ||||

| Ernst 1992 | x | ||||

| Martoni 1991 | x | ||||

| Belch 1991 | x | ||||

| Smith 1989* | x | ||||

| Siris 1983 | x | ||||

| Demas 1982 | x | ||||

| OPEN CONTROL | |||||

| Arican 1999* | x | ||||

| Heim 1995 | x | ||||

| Conte 1994 | x | ||||

| Van Holten 1993 | x | ||||

| ACTIVE CONTROL | |||||

| Koeberle 1999 | x | ||||

| Cascinu 1998 | x | ||||

| Moiseyenko 1998 | x | ||||

| Coleman 1998 | x | ||||

| Glover 1994 | x | ||||

| * studies with >1 active arms |

2. Studies by intervention (clodronate).

| Study | placebo control | open control | 400mg/d PO | 800mg/d PO | 1600mg/d PO | 2400mg/d PO | 3200mg/d PO | Others |

| Arican 1999 | + | + | + | |||||

| Delmas 1982a | + | + | ||||||

| Elomaa 1992 | + | 3.2g/dPO x1m then 1.6g/d PO x5m | ||||||

| Ernst 1992 | + | 600mg IV x1 dose | ||||||

| Ernst 1997 | + | 600mg IV x 1 dose vs 1500mg IV x1 dose | ||||||

| Heim 1995 | + | + | ||||||

| Kylmala 1997 | + | 300mg/d IV x5d, then 1.6g/d PO | ||||||

| Lahtinen 1992 | + | + | ||||||

| Martoni 1991 | + | 300mg/d IV x7d, 100mg/d IM x3w, 100mg alt d IM x2m | ||||||

| Moisenyenko 1998 | 300mgIV x5d vs 1.5gIV x1 dose then placebo x4 d | |||||||

| O'Rourke 1995 | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Piga 1998 | + | + | ||||||

| Robertson 1995 | + | + | ||||||

| Siris 1983 | + | + | ||||||

| Strang 1997 | + | 300mg/d IV x3d, 600mg bid x4w PO |

3. Studies by intervention (Pamidronate IV).

| study | Placebo control | Open control | 40mg q3w IV | 45mg q3w IV | 60mg q3w IV | 60mg q4w IV | 90mg q3w IV | 90mg q4w IV | others |

| Bereneson 1996 | + | + | |||||||

| Cascinu 1998 | + | + | + | ||||||

| Conte 1994 | + | + | |||||||

| Glover 1994 | + | + | 30 mg q2w vs 60 mg q2w | ||||||

| Hortobagyi 1996 | + | + | |||||||

| Hultborn 1996 | + | + | |||||||

| Koeberle 1999 | + | + | |||||||

| Theriault 1999 | + | + | |||||||

| Vinholes 1997a | + | 120 mg x 1dose |

4. Studies by intervention (Pamidronate PO).

| Study | Placebo control | Open control | 150 mg/d | 300 mg/d |

| Brinkler 1998 | + | + | ||

| Coleman 1998 | + | + | ||

| Van Holten 1993 | + | + |

Time frame of interest

To have significant clinical relevance, any pain relief intervention should have a measurable effect an immediate or intermediate time frame. We therefore selected our time frame of interest as within 12 weeks of the commencement of the intervention, and data were collected at 4 weeks, 8 weeks and 12 weeks.

Data extraction

Data extraction sheets were designed a priori and completed independently by the two authors. Where discrepancies arose, these were discussed and a consensus reached. Details of the information sought are given in Table 5.

5. Items sought for inclusion in 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

| Methods | Participants | Intervention | Outcomes | Notes |

| Number of study arms | Primary site (prostate vs breast vs multiple myeloma vs lung vs combination) | For each of intervention arm/active control arm: name of bisphosphonate (etidronate, clodronate, pamidronate, others) | Which of the following pain measure outcome can be extracted from the study: | Oxford Quality Scale score (Jadad) |

| Study design (blind/ open/active controls) | Whether patients have to have bone metastases or not at the time of enrolment (bone mets vs bone mets not required) | Route of administration | Mean pain score pre and post treatment | Number and reason of dropouts |

| If crossover study, duration of washout period | Whether patients have to have pain prior to study enrolment (pain or pain not required) | Dose schedule | Proportion of patients with pain reduction | Other notes |

| Pain measurement tool used | Other interventions in study arm (chemotherapy / hormonal therapy/ others) | Duration of therapy | P value only for a pain measure | |

| Pain score expressed by : patient /physician/ unknown | Performance status measure (life expectancy / others) | Not reported as an endpoint | ||

| Criteria of response for pain. This is only applicable if proportion of patients reponding is an outcome measure. Not specified infers that this is an outcome measure by definition not provided, not applicable infers that this is not an outcome measure used. | Other specifications for inclusion/exclusion | Which of the following analgesics change can be extracted from the data: | ||

| Analgesic measurement tool used | proportion with analgesic reduction | |||

| Criteria of response for analgesic | Others | |||

| Adverse effects for control, and study arm |

Pooling of data

Homogeneity of outcome measures were assessed using Chi square statistics. Where results were considered homogeneous, data were pooled to provide a summary statistic. For dichotomous outcomes, odds ratios were used to compare pooled data. The number‐needed‐to‐treat (NNT) for treatment effect was calculated where appropriate. For continuous data (e.g., standardized pain and analgesic scores) the weighted mean difference was used as the summary statistic.

In presenting the results in the MetaView tables, where more than two active arms are compared, the highest and lowest dose arms only are presented.

Sensitivity analysis/potential sources of heterogeneity

Sensitivity analyses were planned to examine the robustness of the primary conclusions in relation to the following parameters: 1. Nature of control arm (blinded versus open controls) 2. Pain as a study entry criterion (yes versus no) 3. Pain specified as patient reported (specified versus not specified) 4. Blinded controls, pain as study entry criterion and pain specified as patient reported 5. Route/type of bisphosphonates (first versus second versus third generation, intravenous versus oral route) 6. Primary disease site (prostate versus breast versus others) 7. Quality of study (Oxford Quality Scale) (Jadad 1996)

In order to conduct the sensitivity analyses, an outcome parameter that best represented the effectiveness of bisphosphonates in pain relief, and where the maximum number of studies were represented was desirable. We used, "the best response for the proportion of patients with pain relief within 12 weeks". This parameter was chosen retrospectively, due to the limited amount of data available at each time point of interest.

Results

Description of studies

Search results

Eighty‐five publications (full papers and abstracts) were identified, reporting on 51 randomized studies of the use of bisphosphonates in cancer. Twenty‐one studies were excluded; the reasons for exclusion are described in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. A total of 30 studies met the inclusion criteria for this review.

Twenty‐one reports of placebo controlled double blind studies, four open control studies and five studies with active controls were eligible for inclusion (Table 1). These described 3582 participants, with 2096 receiving active treatments and 1586 placebo. In addition to the five studies with active controls, three of the blinded studies (Ernst 1997; O'Rourke 1995; Smith 1989), and one of the open control studies had more than one active arm (Arican 1999).

In summary, the results from 25 studies were available to address the primary objective of the review, and nine studies provided the basis to evaluate whether a dose response relationship existed. None of the active control studies compared different types of bisphosphonates.

Within the double‐blind randomized studies, three were crossover studies (Siris 1983; Ernst 1992; Ernst 1997). Only results from the first randomization phase were included in our analyses since the washout periods were judged to be too short (two, two and zero weeks respectively).

Primary disease sites

The primary disease sites addressed were tabulated in Table 1. Nine studies addressed breast cancer, four prostate cancer, seven multiple myeloma, and ten studies included patients with any primary cancers. For studies which included patients with 'any primary site', the patients generally had more advanced disease.

Pain requirement as an entry criteria

Fourteen of the 30 studies required pain at entry into the study (Siris 1983; Smith 1989; Ernst 1992; Lahtinen 1992; Glover 1994; Robertson 1995; Ernst 1997; Strang 1997; Vinholes 1997a; Cascinu 1998; Coleman 1998; Moiseyenko 1998; Arican 1999).

Pain as the primary endpoint

Of the 30 included studies, only five studies were designed with pain relief as a primary endpoint (Conte 1994; Glover 1994; Koeberle 1999; Vinholes 1997a; Cascinu 1998). Of the remainder, seven studies were designed to describe differences in skeletal events, (Belch 1991; van Holten 1993; Berenson 1996; Hortobagyi 1996a; Hultborn 1996; Brinker 1998; Theriault 1999), two studies were designed to describe differences in radiological progression Lahtinen 1992; Coleman 1998), and one in urinary calcium excretion (O'Rourke 1995).

Types of biphosphonates studied

(Table 2, Table 3, Table 4) Etidronate was used in three studies (Smith 1989; Belch 1991; Daragon 1993), pamidronate in 12 studies and clodronate in 15 studies.

Etidronate was administered orally in two studies (Belch 1991; Daragon 1993) and an initial intravenous route followed by oral maintenance in a study by Smith 1989. The dosing schedules used were as follows:

5 mg/kg/day for 28 days every other 28 days (Belch 1991)

10 mg/kg/day (Daragon 1993),

Three dosing schedules were compared in one study:

‐ 7.5 mg/kg/day for 3 days, then 200 mg twice daily, orally, for one month; ‐ 7.5 mg/kg/day for 3 days then placebo; ‐ placebo for 3 days then 200 mg twice daily, orally, for one month; versus placebo (Smith 1989).

Clodronate was used in 15 trials, administered

orally in nine studies,

intravenously in three studies, and

a mixture of intravenous, oral and intramuscular routes in three studies.

Pamidronate was used in 12 studies, administered:

orally in three studies,

intravenously in nine studies.

Additional details of the dose schedule are provided in Table 2; Table 3; Table 3.

Co‐intervention

Co‐interventions, either in the form of hormone therapy or chemotherapy, were administered in 22 of the 30 studies. Eight studies did not appear to use a co‐intervention and, of these, seven recruited patients with any primary disease site, typically having failed systemic therapy (Arican 1999; Cascinu 1998; Ernst 1992; Ernst 1997; Koeberle 1999; Moiseyenko 1998; Piga 1998) and one recruited patients with prostate cancer (Strang 1997).

Life expectancy/performance status criteria

The studies included patients at different stages of their illness, ranging from early to late stages of metastatic disease. Twenty studies provided criteria to define the general condition of patients invited into the trials.

'Life expectancy' was used in 17 studies (time criteria ranging from more than one month to more than one year).

performance status (WHO </ = 2, poor physical activity, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status </ = 2, ECOG </ = 3, >/ = 50%, Karnofsky performance status (KPS) 50‐80) in six studies.

Eleven studies did not provide any information.

Pain and analgesic measurement tools

A wide variety of pain measurement tools were used. Similarly, the reporting of analgesic intake varied between studies.

One study integrated pain, analgesia and performance status to define treatment response (Vinholes 1997a).

Six studies did not specify the pain measurement tools used (Siris 1983; Belch 1991; Elomaa 1992; van Holten 1993; Hortobagyi 1996a; Harvey 1996; Ernst 1997).

The remaining 24 studies used the following:

1. Visual analogue scales (11 studies) (Ernst 1992; Smith 1989; Martoni 1991; Daragon 1993; O'Rourke 1995; Robertson 1995; Hultborn 1996; Strang 1997; Moiseyenko 1998; Piga 1998; Arican 1999)

2. Ordinal scales with: ‐ 0‐3 point scale (Heim 1995), ‐ 0‐4 point scale (Lahtinen 1992), ‐ 0‐5 point scale (Brinker 1998; Conte 1994; Coleman 1998).

3. The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) pain scale (0‐9 point scale based on the product of pain intensity (0‐3) and severity (0‐3)) was used in five studies (Delmas 1982a; Glover 1994; Berenson 1996; Vinholes 1997a; Theriault 1999).

4. Combination of pain measurement tools Kylmala 1997 used both a visual analogue and a 0‐4‐point scale Koeberle 1999 employed the visual analogue scale and present pain index. Cascinu 1998 employed a quality of life questionnaire which focused on pain

Physician versus patient reporting

Subject/patient reported pain scores were specified in 18 studies. Of these 18 studies, physician reported scores were also collected in three studies (Delmas 1982a, Kylmala 1997, Smith 1989). A further thirteen studies did not specify whether pain was patient or physician reported.

Pain response criteria

The definition of pain response is important when interpreting 'proportion of patients with pain reduction' as an outcome measure.

Eight of the blinded or open control studies presented data on the proportion of patients with pain reduction. The criteria used included:

‐ proportion with no pain (Siris 1983;Elomaa 1992; Kylmala 1997) ‐ major pain reduction, not otherwise specified (Smith 1989) ‐ more than or equal to a 20% reduction in pain score (Vinholes 1997a) ‐ no pain or no need for treatments (Heim 1995) ‐ more than or equal to two category reductions in pain score over at least two consecutive reports (Conte 1994) ‐ definition not specified (Arican 1999).

For studies with active controls, the criteria used included ‐ more than 10 mm decrease in pain (Moiseyenko 1998) ‐ major response, not otherwise specified (Coleman 1998) ‐ did not provide a criterion although the pain scale used was an ordinal scale and it is reasonable to assume that any reduction of more than or equal to 1 point reduction was used (Cascinu 1998). ‐ definition not specified (Smith 1989; Arican 1999) ‐ provided a definition but no data on proportion of patients responding (Koeberle 1999)

Risk of bias in included studies

The quality of the 30 included studies was assessed using the Oxford Quality Scale (Jadad 1996). The Oxford Quality Scale scores achieved were not used to weight the results but used for sensitivity analyses to address the impact of quality on the primary conclusion.

Effects of interventions

No clinical or statistical heterogeneity was observed across the outcomes of interest permitting pooling of the data to provide summary statistics.

Proportion of patients with pain relief

(See Table of Comparisons: Comparison 01: 01‐03) Six placebo controlled trials (Siris 1983; Smith 1989; Elomaa 1992; Kylmala 1997; Vinholes 1997a; Arican 1999) and two open controlled studies (Conte 1994; Heim 1995) (i.e. eight of the 25 placebo or open control studies) provided data for this endpoint within the 12 ‐week time frame. Data were reported for different time points: five studies reported at four weeks, one study at eight weeks, and five studies at twelve weeks.

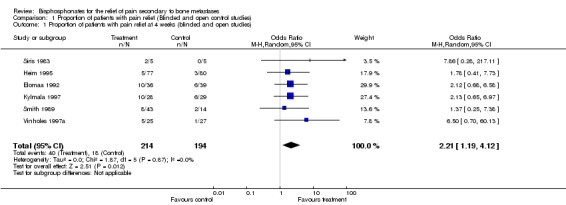

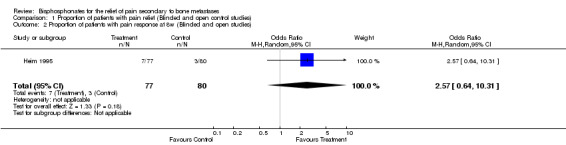

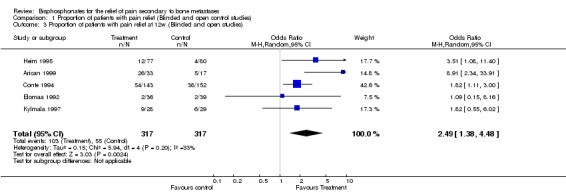

At week 4: OR 2.21 [95% CI 1.19 to 4.12], NNT 11 [95% CI 6 to 36] At week 8: only one study provided these data so pooling for this time point was not meaningful At week 12: OR 2.49 [95% CI 1.38 to 4.48], NNT 7 [95% CI 5 to 12]

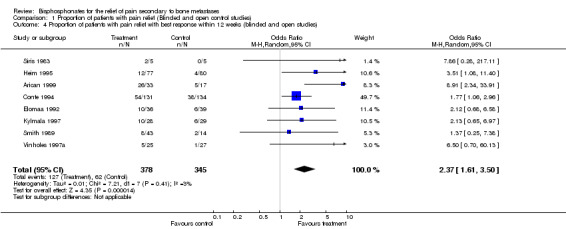

Both week 4 and week 12 results showed a significant benefit for patients receiving bisphosphonates. Given the limited number of studies in which data were available, the results for 'best pain response within 12 weeks' were synthesized as follows: OR 2.37 [95% CI 1.61 to 3.5] , NNT 6 [95% CI 5 to 11] in favor of the treatment group. (This approach was adopted retrospectively, after the data extraction process revealed the limited data available).

Four of the remaining 17 studies with placebo or open controls (Martoni 1991; O'Rourke 1995; Strang 1997; Brinker 1998) did not provide usable data, but reported on the lack of difference between the pain response for treatment and control groups. A total of 619 patients were involved in these four studies, compared with 771 patients in the eight double blind and open control studies in which data for the proportion of patients with response were available (Siris 1983; Smith 1989; Elomaa 1992; Conte 1994; Heim 1995; Kylmala 1997; Vinholes 1997a; Arican 1999). Fourteen of the 26 placebo or open control studies had no data on the proportion of patients with pain relief during the time frame of interest.

The analyses also provided some insight into the time to, and durability of, the response. The responses observed between 4 and 12 weeks appear to be similar. The response pattern at less than 4 weeks could not be assessed due to the lack of data.

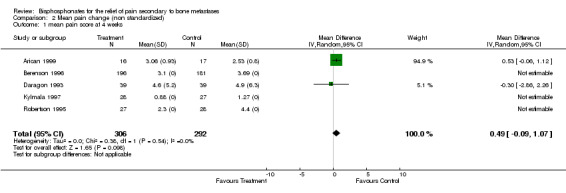

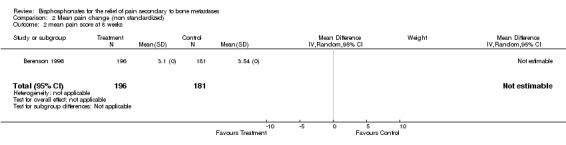

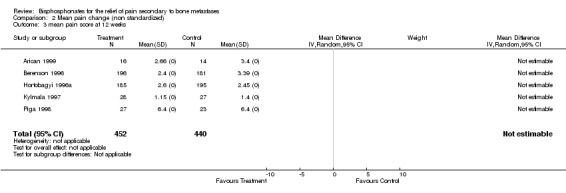

Mean/median pain score

(See Table of Comparisons: Comparison 02: 01‐03) Data were available from seven of the 25 studies (Daragon 1993; Robertson 1995; Berenson 1996; Hortobagyi 1996a; Kylmala 1997; Piga 1998; Arican 1999). However, a quantitative analysis was not possible because:

in the majority of these studies there were differences in the baseline mean pain score,

with the exception of two studies (Daragon 1993; Arican 1999), the standard deviations were not provided and therefore results could not be pooled.

In addition, an 'intention‐to‐treat analysis' could not be undertaken because the trialist did not use this approach.

Of the seven studies, five employed visual analogue scales (VAS) to assess pain levels (Daragon 1993; Robertson 1995; Kylmala 1997; Piga 1998; Arican 1999) and two studies used a 0‐9 point scale (Berenson 1996; Hortobagyi 1996a). Standardization of the pain scores was not attempted. The mean pain scores for the study and control arms reported in the original papers are presented in the meta‐analysis. Whilst there was a general trend showing the mean pain score was lower for the treatment arm, the magnitude of difference between the treatment and control arms ranged from ‐0.53 to 2.1 at week 4, and ‐0.37 to 1 at week 12.

This review serves to highlight the limitation of using mean or median pain scores as an endpoint to evaluate pain relief, especially when trying to interpret the results within a quantitative systematic review.

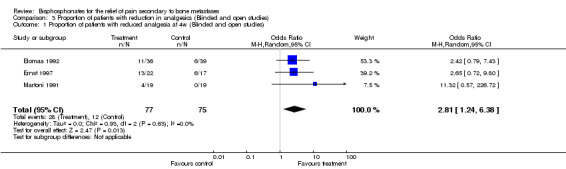

Proportion of patients with reduction in analgesics

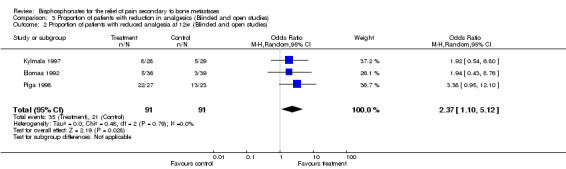

(See Table of Comparisons: Comparison 03: 01‐02) Data for the proportion of patients with reduction of analgesics were available in five of the 26 trials (Martoni 1991; Elomaa 1992; Ernst 1997; Kylmala 1997; Piga 1998). Data were reported at different time frames (three trials had results at week 4 and three trials had results at week 12). Only one study provided data at 8 weeks (Elomaa 1992).

Pooled results gave an OR in favor of the treatment groups as follows:

week 4: OR 2.81 [95% CI: 1.24 to 6.38]

week 12: OR 2.37 [95% CI: 1.1 to 5.12]

Mean analgesic consumption

Three of the 25 studies reported on mean analgesic consumption (Ernst 1992; Robertson 1995; Ernst 1997). An additional three studies provided some description of the lack of difference in analgesic consumption (O'Rourke 1995; Hultborn 1996; Brinker 1998). There was insufficient information to allow a quantitative summary of the data.

Data from three studies that provided data were summarized here as reported from the original studies: • Ernst 1997 describes an average change in morphine equivalent (mg) of ‐6.4 (standard error: S.E. 2.9) for the treatment arm and +24.6 (S.E. 14.9) for the placebo arm (P = 0.03) • A similar study (Ernst 1992) reported an average change in morphine equivalent (mg) of + 10 (S.E. 8.1) for the treatment arm and + 62 (S.E. 29.6) for the placebo arm (P = 0.096) • Robertson 1995 reported on the percentage increase in morphine equivalent (mg). At 4 weeks, this was 59% and 64% for treatment and control arm respectively.

These results should be interpreted in the context of the three studies that reported no difference in the analgesic use:

Hultborn 1996 reports that the use of analgesics was insignificantly lower in the pamidronate group during follow up.

Brinker 1998 compares the amount of analgesics taken during the trial, and reports no difference between the treatment and control arms (p=0.26).

For both of these studies, the time frames for analgesic comparison were not stated but, based on the study duration, it is likely that a longer time period than that of interest in this review (within 3 months) was allowed.

O'Rourke 1995 reports that after 4 weeks' treatment, the overall analgesic requirement remained the same.

The problems relating to the interpretation of this endpoint are similar to those discussed for mean change in pain score.

Other analgesic endpoints reported

Four studies used other analgesic endpoints. The small number of studies that employed other endpoints limited the power of inference.

Daragon 1993 reports on the number of patients taking codeine or morphine between the treatment arms

Elomaa 1992 and Heim 1995 report on the proportion of patients with no analgesics

Piga 1998 reports on the proportion of patients with no increase in analgesics

No analgesic information is provided for 12 of the 25 blinded, placebo controlled trials and two open control studies.

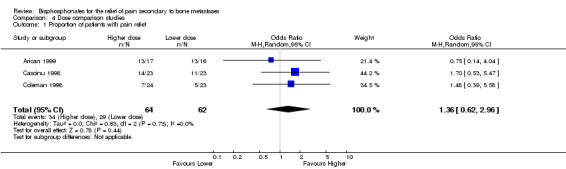

Implications from studies with active controls

(See Table of Comparisons: Comparison 04: 01) Where more than two arms were available, the results for the highest and lowest dose arms only were presented in the MetaView tables. The results of these studies were best suited to address the effect of dose intensity. Within the context that the implications from the blinded placebo controlled trials support the effectiveness of the intervention, the presence of a dose response relationship would strengthen the primary conclusion that there was a treatment effect.

Of the nine studies with active controls, two studies cannot be used to assess dose response relationship. Moiseyenko 1998 examines the same total dose given on day one versus over five days; and Smith 1989 compares a regimen of 'loading and maintenance' with 'loading dose with placebo maintenance', and 'placebo loading with maintenance dose'.

Three studies present data on the proportion of patients with pain relief (Cascinu 1998; Coleman 1998); Arican 1999). However, the results are not statistically significant and no conclusions on a dose response can be drawn.

Four of the seven studies use other outcome measures, not amenable to quantitative analysis, including:

the percentage reduction of pain score (Ernst 1997; Koeberle 1999)

the median change in pain score (Glover 1994)

an insignificant p‐value (O'Rourke 1995)

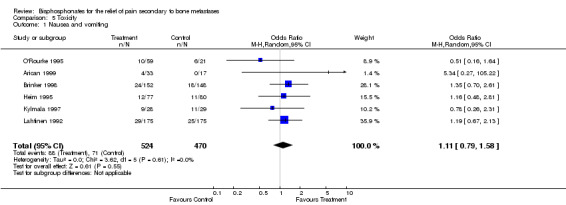

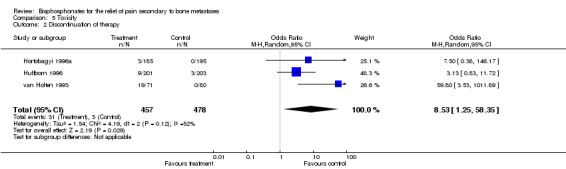

Adverse drug reaction

(See Table of Comparisons: Comparison 05: 01‐02) Fourteen of 20 blinded studies, four of four open control studies, and five of six active control studies present information on adverse drug reactions. Of these, three studies employ the WHO toxicity classification criteria (WHO 1979), and four studies report on the number of patients where adverse drug reaction led to discontinuation of therapy. Details are provided in the 'Characteristics of Included Studies' Table. Nausea and vomiting is reported in 24 studies: OR 1.11 [95% CI 0.79 to 1.58] and indicates a non‐significant trend for increased nausea and vomiting.

Discontinuation of therapy due to adverse effects (reported in three studies) ‐ an outcome reflecting their severity ‐ gave an OR of 8.53 [95% CI 1.25 to 58], NNH 16 [95% CI 12 to 27].

Other types of reactions are described, including abdominal pain, allergic reactions, and hypocalcemia. Insufficient data are provided to permit any conclusions to be drawn.

Quality of life

Quality of life comparisons are presented in four of the 26 studies (Berenson 1996; Harvey 1996; Hortobagyi 1996a; Vinholes 1997a). Of these, three presented quality of life comparisons at a time point beyond our time frame of interest (three months). Berenson 1996 reports no difference in quality of life at baseline and nine months. Harvey 1996 reports that, at nine months, quality of life had decreased significantly less with bisphosphonates than with placebo. Hortobagyi 1996a states that fewer patients in the pamidronate group than in the placebo group had a decrease in quality of life scores at last measurement (this study involved a treatment period of 12 months).

Only one study (Vinholes 1997a) provided a quality of life comparison within the time frame of interest. This study described a small but non‐significant improvement in quality of life compared with baseline in the pamidronate arm at four weeks; quality of life worsened in the placebo arm.

Sensitivity analysis

In interpreting our sensitivity analyses, the small number of studies with usable quantitative data should be noted, which limits the strength of the conclusions that can be drawn. We used the parameter, "proportion of patients with pain relief using best response within 12 weeks", to conduct our sensitivity analyses because this measure has some clinical significance for the primary objective of this review, and permits the inclusion of data from the greatest number of studies.

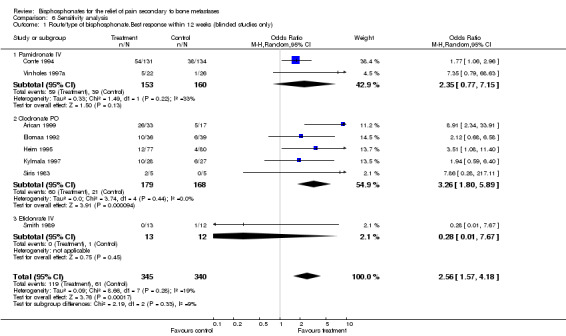

1. Type/and route of bisphosphonates

(See Table of Comparisons: Comparison 06: 01) No formal sensitivity analysis was possible for etidronate since only one study addressed the outcome of interest (Smith 1989). Five studies provided data for oral clodronate and gave an OR of 3.26 [95% CI 1.8 to 5.89]. For intravenous pamidronate, two studies provided data (Conte 1994; Vinholes 1997a), and gave an OR of 2.35 [0.77 to 7.15].

The small numbers of studies meant conclusions could not be made regarding the relative effectiveness of bisphosphonates on patients with different dose preparations.

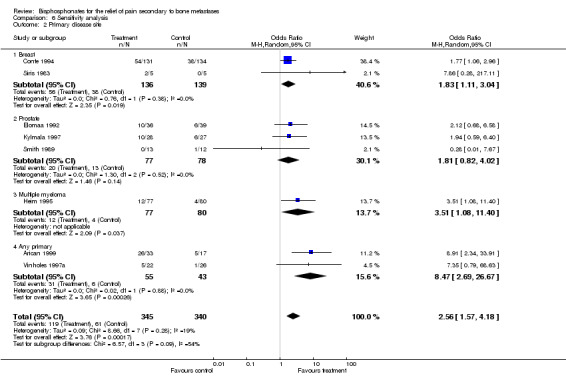

2. Primary disease site

(See Table of Comparisons: Comparison 06: 02) Studies were grouped according to primary disease site using best response for proportion of patients with pain relief within 12 weeks. The results were as follows:

breast cancer, OR 1.83 [95% CI 1.11 to 3.04]

prostate cancer, OR 1.81 [95% CI 0.82 to 4.02]

any primary cancer site, 8.47 [95% CI 2.69 to 27]

one study included multiple myeloma patients with an OR of 3.51 [95% CI 1.08 to 11.4].

The small numbers of studies meant conclusions could not be made regarding the relative effectiveness of bisphosphonates on patients with different primary disease sites.

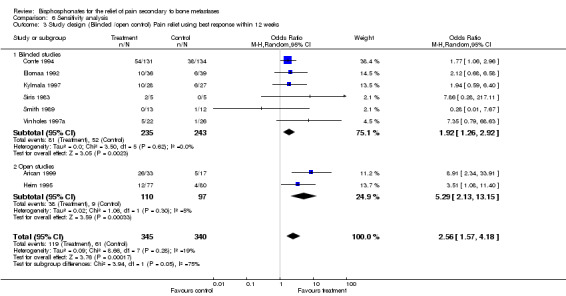

3. Nature of control: Blinded versus open

(See Table of Comparisons: Comparison 06: 03) The exclusion of studies with open controls increased the homogeneity of the results from P = 0.28 for blinded and open studies to P = 0.62 for blinded studies only. The corresponding pooled estimates were 2.56 [95% CI: 1.57 to 4.18] and 1.92 [95% CI: 1.26 to 2.92] respectively, indicating that, while the pooled results remained statistically significant in favor of the use of bisphosphonates, the magnitude of the effect was smaller. The NNT was 6 for all studies and 8 for blinded studies only.

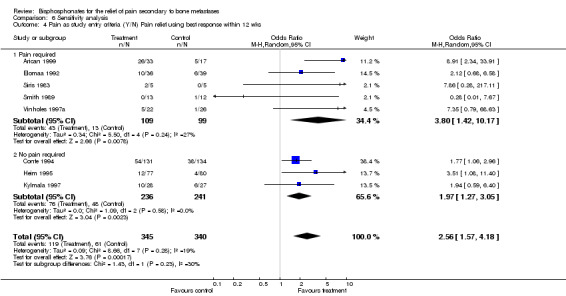

4. Pain as a study entry criteria

(See Table of Comparisons: Comparison 06: 04) Exclusion of studies where pain was not an entry criterion gave an OR of 3.8 [95% CI 1.42 to 10.17] suggesting a stronger pain relief effect in studies where the presence of pain was an eligibility requirement.

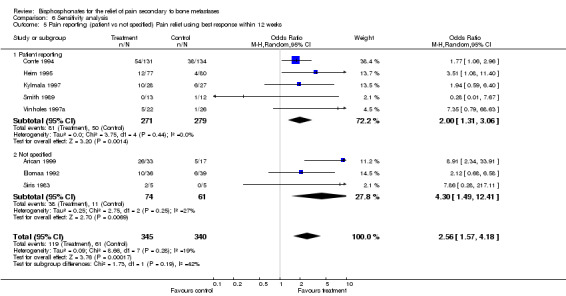

5. Pain specified as patient reported

(See Table of Comparisons: Comparison 06: 05) Five studies specified that pain outcomes were patient reported, and gave an OR of 2 [95% CI 1.31 to 3.06]. This supports the primary conclusion (proportion of patients with pain relief) although the magnitude was slightly smaller than when all studies are included.

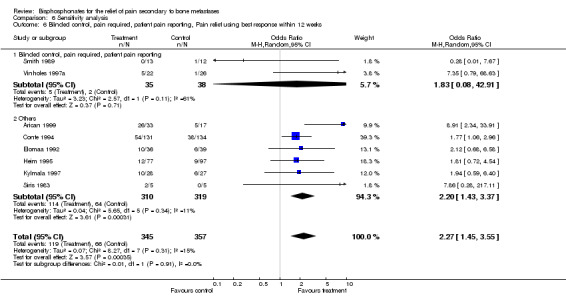

6. Blinded studies; pain as eligibility requirement; and pain reported by patients

(See Table of Comparisons: Comparison 06: 06) As discussed in the 'Types of studies' section, the most robust data upon which to evaluate our primary outcome would come from the inclusion of studies that fulfil all three criteria. However, only two studies meet these criteria (Vinholes 1997a; Smith 1989). In addition to the small number of studies eligible, the results were clinically heterogeneous making pooling of data illogical. The results are presented in the Table of Comparisons: Comparison 06: 04 for completeness only.

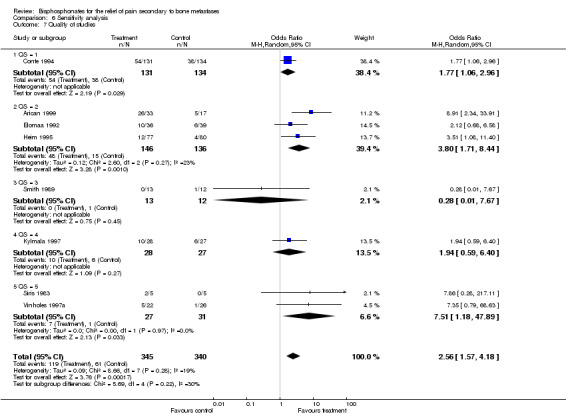

7. Quality of the studies

(See Table of Comparisons: Comparison 06: 07) The quality of the studies is reported in the 'Characteristics of Included Studies' Table. The Oxford Quality Scale scores ranged from 1 to 5 with a median of 3. Sensitivity analysis based on the quality of studies using, 'the proportion of patients with best response at 12 weeks', given the limitation of the small number of studies in each group, showed no quality effect.

Discussion

It is unfortunate that, despite the identification of over 50 randomized studies in this topic area, with 21 of these being blinded placebo controlled trials, the data available to facilitate a meta‐analysis of the effectiveness of bisphosphonate in providing pain relief are so limited that no robust conclusions can be reached. The multiple methods used by trialists, and lack of consensus on which pain endpoints should be included in the reporting of pain response, represent the major limiting factors. These are problems, not only within bisphosphonate trials, that are observed in other areas where pain measurement is a key outcome. Clinicians and researchers planning analgesic trials should seek advice at the planning stage from experts in pain trials.

The most important and clinically relevant endpoint for inclusion in quantitative reviews is the proportion of patients with pain relief, described for each arm of the trial. Even when no significant differences are observed, the relevant data must be reported to allow appraisal. Mean pain scores are not helpful in calculating effectiveness. Other endpoints, such as adverse effects (based on standardized toxicity classification criteria) and quality of life assessment would provide useful data and should be integrated into future trials.

The following conclusions regarding the effectiveness of bisphosphonates for pain relief should be interpreted with consideration for the small number of eligible studies.

There is some evidence to suggest a significant benefit in favor of the use of bisphosphonates, OR 2.37 [95% CI: 1.61 to 3.5], NNT of 6 [95% CI 5 to 11] for the outcome, 'best response within 12 weeks';

When the three most stringent criteria are applied (blinded control, pain as an eligibility criteria, and patient reported pain), only two studies can be included, precluding meaningful pooling of the results, and the amount of pain relief achieved from bisphosphonates appears to be small;

In terms of the pattern of response over time, the magnitude of benefit from bisphosphonates at 4 weeks is similar to that observed at 12 weeks.

Despite the methodological limitations, the evidence suggests that bisphosphonates provide modest pain relief for patients with painful bony metastases.

Adverse drug reactions were generally mild. We calculated a number needed to harm (NNH) of 16 [95% CI 12 to 27] for adverse drug reactions requiring discontinuation of therapy. There is a trend towards increased incidence of nausea and vomiting although this does not reach statistical significance.

There were insufficient data to evaluate the impact of drug type; route of administration; and variation of response between different primary disease sites.

Analgesics have and will continue to be an important part of the management of painful bony metastases. In addition, where clinically appropriate, radiotherapy has been shown to be an important modality. In a review conducted by McQuay 1997, the NNT for the effectiveness of radiotherapy in pain relief was 3.6 [95% CI 3.2 to 3.9] for at least 50% pain relief, with a median duration of pain relief of 12 weeks.

For patients with diffuse, painful metastases, especially where analgesics, with or without radiotherapy, do not provide adequate pain relief, or are accompanied by unacceptable adverse drug reactions, the use of bisphosphonates for pain reduction is justifiable. Our review focused on answering the question whether patients in need of therapy for pain relief in the shorter term would benefit from bisphosphonate therapy, as in the example of patients with more advanced disease and limited life expectancies. The use of bisphosphonates with other longer term objectives such as reduction in skeletal event rates was not an objective of this review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This review provides an estimate of one patient benefiting with "some pain relief" for each six patients being treated. There are insufficient data to recommend its use to provide immediate effect, and the maximum response is likely to be observed by four weeks. Adverse drug reactions were severe enough to cause discontinuation of therapy in one out of every eleven patients treated.

Given these conclusions, there is insufficient evidence to recommend bisphosphonates for the management of painful bony metastases as first line therapy. Bisphosphonates should be considered in addition to analgesics and/or radiotherapy when these modalities alone are inadequate for the management of painful bony metastases. There is insufficient evidence to allow a recommendation to be made on the most effective bisphosphonates for this purpose. There is also insufficient evidence to recommend the selection of patients for this treatment strategy based on primary histologies.

Implications for research.

This review shows that a significant body of research (30 studies) has failed to produce a clear answer, mainly because proven methods for assessing pain, and best practice in trial design, were not incorporated. This represents a terrible waste of research resources.

Future investigators should agree common criteria for the reporting of pain response in order to provide usable data in trials where pain as an outcome. The authors recommend the use of the proportion of patients with pain relief with predefined definitions for response. Ideally, this may involve an integrated pain and analgesic response criterion in order to take into account the potential confounding effect of other analgesics. The use of mean pain and/or analgesic scores as secondary endpoints is not recommended. If it is necessary to use this as an outcome, the inclusion of the standard deviation in the reporting of results is mandatory.

Studies focusing on subgroups who are most likely to benefit from bisphosphonates for pain relief, such as those with pain refractory to conventional analgesics, would be useful in order to better define the role of bisphosphonates for pain relief in patients with painful bony metastases.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 November 2013 | Amended | See Published notes. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2000 Review first published: Issue 2, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 August 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 13 May 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 11 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Notes

This review is out of date, and the original authors are no longer available to update it. The contents of this review should be accepted for historical interest only as they may be misleading for current practice.

Acknowledgements

The review authors would like to thank Dr Svetlana Rutter for her assistance in translating a Russian trial report.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Proportion of patients with pain relief (Blinded and open control studies).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion of patients with pain relief at 4 weeks (blinded and open studies) | 6 | 408 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.21 [1.19, 4.12] |

| 2 Proportion of patients with pain response at 8w (Blinded and open studies) | 1 | 157 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.57 [0.64, 10.31] |

| 3 Proportion of patients with pain relief at 12w (Blinded and open studies) | 5 | 634 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.49 [1.38, 4.48] |

| 4 Proportion of patients with pain relief with best response within 12 weeks (blinded and open studies) | 8 | 723 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.37 [1.61, 3.50] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Proportion of patients with pain relief (Blinded and open control studies), Outcome 1 Proportion of patients with pain relief at 4 weeks (blinded and open studies).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Proportion of patients with pain relief (Blinded and open control studies), Outcome 2 Proportion of patients with pain response at 8w (Blinded and open studies).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Proportion of patients with pain relief (Blinded and open control studies), Outcome 3 Proportion of patients with pain relief at 12w (Blinded and open studies).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Proportion of patients with pain relief (Blinded and open control studies), Outcome 4 Proportion of patients with pain relief with best response within 12 weeks (blinded and open studies).

Comparison 2. Mean pain change (non standardized).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mean pain score at 4 weeks | 5 | 598 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.49 [‐0.09, 1.07] |

| 2 mean pain score at 8 weeks | 1 | 377 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 mean pain score at 12 weeks | 5 | 892 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Mean pain change (non standardized), Outcome 1 mean pain score at 4 weeks.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Mean pain change (non standardized), Outcome 2 mean pain score at 8 weeks.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Mean pain change (non standardized), Outcome 3 mean pain score at 12 weeks.

Comparison 3. Proportion of patients with reduction in analgesics (Blinded and open studies).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion of patients with reduced analgesia at 4w (Blinded and open studies) | 3 | 152 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.81 [1.24, 6.38] |

| 2 Proportion of patients with reduced analgesia at 12w (Blinded and open studies) | 3 | 182 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.37 [1.10, 5.12] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Proportion of patients with reduction in analgesics (Blinded and open studies), Outcome 1 Proportion of patients with reduced analgesia at 4w (Blinded and open studies).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Proportion of patients with reduction in analgesics (Blinded and open studies), Outcome 2 Proportion of patients with reduced analgesia at 12w (Blinded and open studies).

Comparison 4. Dose comparison studies.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion of patients with pain relief | 3 | 126 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.36 [0.62, 2.96] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Dose comparison studies, Outcome 1 Proportion of patients with pain relief.

Comparison 5. Toxicity.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Nausea and vomiting | 6 | 994 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.79, 1.58] |

| 2 Discontinuation of therapy | 3 | 935 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 8.53 [1.25, 58.35] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Toxicity, Outcome 1 Nausea and vomiting.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Toxicity, Outcome 2 Discontinuation of therapy.

Comparison 6. Sensitivity analysis.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Route/type of bisphosphonate.Best response within 12 weeks (blinded studies only) | 8 | 685 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.56 [1.57, 4.18] |

| 1.1 Pamidronate IV | 2 | 313 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.35 [0.77, 7.15] |

| 1.2 Clodronate PO | 5 | 347 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.26 [1.80, 5.89] |

| 1.3 Etidonrate IV | 1 | 25 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.28 [0.01, 7.67] |

| 2 Primary disease site | 8 | 685 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.56 [1.57, 4.18] |

| 2.1 Breast | 2 | 275 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.83 [1.11, 3.04] |

| 2.2 Prostate | 3 | 155 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.81 [0.82, 4.02] |

| 2.3 Multiple myeloma | 1 | 157 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.51 [1.08, 11.40] |

| 2.4 Any primary | 2 | 98 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 8.47 [2.69, 26.67] |

| 3 Study design (Blinded /open control) Pain relief using best response within 12 weeks | 8 | 685 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.56 [1.57, 4.18] |

| 3.1 Blinded studies | 6 | 478 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.92 [1.26, 2.92] |

| 3.2 Open studies | 2 | 207 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 5.29 [2.13, 13.15] |

| 4 Pain as study entry criteria (Y/N) Pain relief using best response within 12 wks | 8 | 685 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.56 [1.57, 4.18] |

| 4.1 Pain required | 5 | 208 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.80 [1.42, 10.17] |

| 4.2 No pain required | 3 | 477 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.97 [1.27, 3.05] |

| 5 Pain reporting (patient vs not specified) Pain relief using best response within 12 weeks | 8 | 685 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.56 [1.57, 4.18] |

| 5.1 Patient reporting | 5 | 550 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.00 [1.31, 3.06] |

| 5.2 Not specified | 3 | 135 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 4.30 [1.49, 12.41] |

| 6 Blinded control, pain required, patient pain reporting, Pain relief using best response within 12 weeks | 8 | 702 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.27 [1.45, 3.55] |

| 6.1 Blinded control, pain required, patient pain reporting | 2 | 73 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.83 [0.08, 42.91] |

| 6.2 Others | 6 | 629 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.20 [1.43, 3.37] |

| 7 Quality of studies | 8 | 685 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.56 [1.57, 4.18] |

| 7.1 QS = 1 | 1 | 265 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.77 [1.06, 2.96] |

| 7.2 QS = 2 | 3 | 282 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.80 [1.71, 8.44] |

| 7.3 QS = 3 | 1 | 25 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.28 [0.01, 7.67] |

| 7.4 QS = 4 | 1 | 55 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.94 [0.59, 6.40] |

| 7.5 QS = 5 | 2 | 58 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 7.51 [1.18, 47.89] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis, Outcome 1 Route/type of bisphosphonate.Best response within 12 weeks (blinded studies only).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis, Outcome 2 Primary disease site.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis, Outcome 3 Study design (Blinded /open control) Pain relief using best response within 12 weeks.

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis, Outcome 4 Pain as study entry criteria (Y/N) Pain relief using best response within 12 wks.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis, Outcome 5 Pain reporting (patient vs not specified) Pain relief using best response within 12 weeks.

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis, Outcome 6 Blinded control, pain required, patient pain reporting, Pain relief using best response within 12 weeks.

6.7. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analysis, Outcome 7 Quality of studies.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Arican 1999.

| Methods | 2 active arms, 1 control Pain measurement tool: 10 cm VAS Definition of pain response: not specified Analgesic scale: 0: no narcotics, 1: 30 mg morphine, 2: 60 mg morphine, 3: 90 mg morphine Toxicity criteria: WHO classification |

|

| Participants | Any primary Bone metastases required Pain present Cointervention: none described Life expectancy > 3 months Other criteria: exclude bisphosphonates or radiotherapy within </ = 4 wks, hypercalcemia, renal dysfunction, Pagets disease, vitamin D deficiency |

|

| Interventions | Active arm 1:

Clodronate Oral 800 mg/day

x 3 months 16 pts Active arm 2: Clodronate Oral 1600 mg/day x 3 months 17 pts Control: No treatment 17 pts |

|

| Outcomes | Pain:

a. Mean change

b. Proportion of pts with pain reduction Analgesic: a. Proportion of pts. with analgesia reduction Others: a. Changes in urinary calcium, b. Urinary hydroxyproline, c. Serum ICTP (type 1 collagen degradation product). Withdrawals: Active arm 1: 0/16 Active arm 2: 0/17 Control: 3/17 Adverse effects: Active arm 1: Nausea and vomiting: 2/16 Abdominal pain: 1/16 Hypocalcemia:1/16 Active arm 2: Nausea and vomiting: 2/17 Diarrhea: 1/17 Abdominal pain: 1/17 Hypocalcemia: 2/17 Control arm: none described |

|

| Notes | QS = 2 | |

Belch 1991.

| Methods | Active arm vs placebo control Pain measurement tool: not specified |

|

| Participants | Multiple myeloma 80% of patients has at least 1 lytic lesion, bony involvement not required Pain not required Co‐intervention: melphalan and prednisone Performance status criteria: no specifications Other criteria: exclude serious concurrent illness, chronic renal failure |

|

| Interventions | 1. Active arm:

Etidronate

Oral

5 mg/kg/day/ x28 days every other 28 days

indefinitely

98 pts 2. Control arm: Placebo 78 pts All patients received melphalan and prednisone |

|

| Outcomes | Pain:

a. P value shows no significant difference in pain Others: a. Episodes of hypercalcemia b. Pathological fractures c. Vertebral index Withdrawals: Active arm: 6/98 Control arm: 3/78 Adverse effects not reported |

|

| Notes | QS = 4 Study started with 3 arms with 2 active arms (an additional arm of etidronate 20 mg/kg/d). This arm was dropped because of reports of demineralization in another trial. |

|

Berenson 1996.

| Methods | Active vs placebo control study, stratified by first or second line chemotherapy at study entry Pain measurement tool: 0‐9 point scale [pain severity (0‐3) x pain intensity (0‐3)] Analgesic scale: 0‐9 point scale |

|

| Participants | Multiple myeloma SIII

with lytic lesions Pain not required Co‐intervention: chemotherapy Performance status criteria: life expectancy: > 9 months Other criteria: exclude skeletal event within 2 wks of enrolment, renal dysfunction, liver dysfunction, abnormal ECG, previous bisphosphonates, calcitonin, corticosteroid |

|

| Interventions | 1. Active arm:

Pamidronate IV

90 mg/every 4 weeks

Total of 36 weeks

203 pts 2. Control arm: Placebo 189 pts All patients received chemotherapy as was clinically indicated |

|

| Outcomes | Pain:

a. Mean pain score in each group Analgesic: States no change, no details Others: a. Any skeletal events b. Performance status c. Quality of life d. Survival e. Radiological changes f. Serum paraproteins, beta 2 microglobulin, Urinary Bence Jones proteins Withdrawals: Active arm: 7/203 Control arm: 8/189 7. Adverse effects a. Active arm: Allergic reaction: 1/203 Hypocalcemia: 1/203 b. Control arm: none described |

|

| Notes | QS = 4 | |

Brinker 1998.

| Methods | Active vs placebo control study, stratified by status on simultaneous study: on interferon, not on interferon trial, and not eligible for interferon trial Pain measurement tool: 6‐point scale Pain score expressed by patient Analgesic scale: amount consumed in the last 24 hours |

|

| Participants | Multiple myeloma Lytic lesions not a requirement Pain not required Co‐intervention: melphalan and prednisone+/‐ interferon Performance status criteria: life expectancy > 3 months Other criteria: exclude peptic ulcer, renal dysfunction |

|

| Interventions | 1. Active arm:

Pamidronate

Oral

75 mg twice daily

Indefinitely

152 pts 2. Control arm: Placebo 148 pts All pts receive melphalan and prednisone +/‐interferon |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Pain:

Pamidronate 126/152 episodes severe pain

Placebo 180/148 episodes severe pain Others: a. Skeletal related morbidity b. Survival c. Frequency of hypercalcemia Withdrawals a. Active arm: 16/152 b. Control arm: 14/148 Adverse effects a. Active arm: Nausea 18 Vomiting 7 Abdominal pain 3 Diarrhea 8 Dysphagia 10 GI hemorrhage 4 Esophageal ulcer 2 Gastric ulcer 4 b. Control arm: Nausea 12 Vomiting 6 Abdominal pain 6 Diarrhea 9 Dysphagia 6 GI hemorrhage 2 Esophageal ulcer 0 Gastric ulcer 2 |

|

| Notes | QS = 4 | |

Cascinu 1998.

| Methods | 3 active arms Pain and mobility measurement tool: use QoL questionnaire with focus on pain and mobility. Patient reported Analgesic scale: total (mg) consumed in 24 hours |

|

| Participants | Any primary, failed hormones/ chemotherapy Bone metastases present Pain required Co‐intervention: none described Performance status criteria: life expectancy >/ = 3 months Other criteria: exclude hypercalcemia, brain metastases, previous bisphosphonates, and ongoing chemotherapy |

|

| Interventions | Active arm 1:

Pamidronate

Intravenous

45 mg every 3 weeks

for 12 weeks

23 pts Active arm 2: Pamidronate Intravenous 60 mg every 3 weeks for 12 weeks 24 pts Active arm 3: Pamidronate Intravenous 90 mg every 3 weeks for 12 weeks 23 pts |

|

| Outcomes | Pain:

a. Proportion with pain and mobility reduction Analgesic: reduction seen in all three groups Withdrawal None 7. Adverse effects Active arm 1: Fever and myalgia: 1/23 Active arm 2: 0/24 Active arm 3: Fever and myalgia: 1/23 |

|

| Notes | QS = 1 | |

Coleman 1998.

| Methods | 2 active arms Pain measurement tool: 6‐point scale, and the Oswestry back pain questionnaire: patient reported Definition of pain response: any two of the following criteria: major response, any two of the lesser criteria in brackets: minor response a: reduction in pain by at least 2 category at 2 consecutive 4 weekly visits b: 20% (10%) improvement in the score of the pain and mobility questionnaire at two consecutive 4 weekly visits c: 50% (25%) reduction for at least 2 months in the dose of the most powerful analgesic taken Analgesic scale: 7‐point analgesic scale based on total amount consumed in 24 hours |

|

| Participants | Breast cancer, failed at least 1 systemic therapy Bone metastases required (At least 2 lesions) Pain required Co‐intervention: hormonal therapy that has been on going, no chemotherapy allowed Performance status criteria: life expectancy >/= 3 months, WHO performance status </=2 Other criteria: exclude peptic ulcer, bisphosphonates within last 6 months, hypercalcemia |

|

| Interventions | Active arm 1:

Pamidronate Oral 150 mg twice a day indefinitely

24 pts Active arm 2: Pamidronate Oral 150 mg every morning and placebo every morning 23 pts |

|

| Outcomes | Pain:

a. Proportion of patients with pain reduction Analgesic: Not an endpoint Others: Urinary calcium as a measure of bone resorption Adverse effects Active arm 1: 0/24 Active arm 2: (Grade 3) Nausea and vomiting: 3 Diarrhea: 2 Abdominal pain: 1 |

|

| Notes | QS = 2 | |

Conte 1994.

| Methods | Active vs control Pain measurement tool: 6‐point scale. Patient reported Definition of pain response: a. Some improvement: improvement by 1 point over 2 consecutive reports or by 2 points in 1 report b. Marked improvement: improvement by 2 points over at least 2 consecutive reports |

|

| Participants | Breast cancer, no previous chemotherapy Bone metastases required Pain not required. Co‐intervention: chemotherapy Performance status criteria: no specifications Other criteria: none | |

| Interventions | 1. Active arm:

Pamidronate

Intravenous

45 mg every 3 weeks

Indefinitely until toxicity or progressive bone disease

143 pts 2. Control arm: No additional intervention 152 pts All patients received chemotherapy, standardized for each participating institution |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Pain:

a. Proportion of patients with reduced pain

No pain: 80/131 pamidronate

70/134 control

Marked improvement:

54/131 pamidronate

38/134 control 2. Analgesic: stated is a secondary endpoint but no data /outcome reported Withdrawals Active arm: 6/143 Control arm: 6/152 Adverse reactions Active arm: Local reaction: 13 Fever: 8 Rigors: 2 Headache: 4 Musculoskeletal pain: 6 Hypocalcemia: 23 Control arm: Local reaction: 7 Fever 4 Rigors 0 Headache: 5 Musculoskeletal pain: 22 Hypocalcemia: 9 |

|

| Notes | QS = 1 | |

Daragon 1993.

| Methods | Active vs placebo control study, stratified by whether bone biopsy obtained Pain measurement tools: a. Visual analogue scale b. 3‐point categorical scale Analgesic scale: analgesics consumed classified as: a. Paracetamol b. Codeine c. Morphine |

|

| Participants | Multiple myeloma (SII, III) Bone lesion not specified No pain requirement Co‐intervention: chemotherapy Performance status criteria: poor physical activity Other criteria: exclude renal dysfunction, severe bone marrow insufficient, age >80, cardiac failure, diabetes, gastric or duodenal ulcer, prior chemotherapy, multiple myeloma diagnosed >3 months. |

|

| Interventions | 1. Active arm:

Etidronate

Oral

10 mg/kg/day

4 months

49 pts 2. Control arm: Placebo 45 pts All patients receive cyclophosphamide and prednisone |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Pain:

a. Change in mean pain score of the group 2. Analgesic: a. Proportion of patients taking codeine/morphine Others: a. Karnofsky performance status change b. Incidence of new extraspinal mets c. Incidence of fractures d. Survival e. Change in Vertebral index f. Bone resorption as measured by urine hydroxyproline/ calcium/ creatinine levels Withdrawals Active arm: 10/49 Control arm: 6/45 Adverse effects Active arm: Skin allergy: 1 Control arm: Pancreatitis: 1 |

|

| Notes | QS = 3 | |

Delmas 1982a.

| Methods | Active vs placebo control Pain measurement tool: 0‐9 point scale based on severity and duration Pain score expressed by: patient and physician |

|

| Participants | 1. Multiple myeloma 2. Bone involvement not specified 3. Pain not required 4. Co‐intervention: chemotherapy 5. Performance status criteria: no specifications 6. Other criteria: exclude patients previously treated with >10 cycles of chemotherapy, renal dysfunction | |

| Interventions | 1. Active arm:

Clodronate Oral

800 mg twice a day for

2 years 7 pts 2. Control arm: Placebo 6 pts All patients received melphalan and prednisone |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Pain:

No pain data within 12 weeks of enrollment Others: a. Mean pain score change at 6 months b. Proportion with radiological progression at 1 year c. Comments on serum calcium, urinary calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, and bone histomorphology for subgroup of patients. No withdrawals Adverse effects not reported |

|

| Notes | QS = 4 | |

Elomaa 1992.

| Methods | Active vs placebo control Definition of pain response: proportion with no pain Analgesic response definition: proportion with no analgesic |

|

| Participants | Prostate cancer (failed 1 hormone) Bone metastases required Pain required Co‐intervention: chemotherapy/hormonal therapy Performance status criteria: life expectancy >/=3 months Other criteria: exclude radiotherapy within 2 weeks |

|

| Interventions | 1. Active arm:

Clodronate Oral

3.2 g per day for one month, then 1.6 g per day for 5 months

For 6 months

36 pts 2. Control arm: Placebo 39 pts All patients received Estramustine |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Pain:

a. Proportion of patients with no pain 2. Analgesic: Analgesic consumption reduced in 15/17 Clodronate 3/17 placebo Others: a. Serum calcium b. Survival Evaluable data: 12 pts receiving Clodronate and 10 pts from the placebo group died within the first year of the study No adverse effects reported. |

|

| Notes | QS = 2 | |

Ernst 1992.

| Methods | Active vs placebo Crossover study

washout period: 2 weeks Pain measurement: 10 cm VAS, patient reported Analgesic scale: morphine equivalent for amount consumed in 24 hours |

|

| Participants | Any primary Bone metastases required Pain required Other criteria: exclude radiotherapy, or change in chemotherapy or hormonal therapy within 4 weeks, heart failure, and abnormal renal function tests |

|

| Interventions | 1. Active arm:

Clodronate

Intravenous

600 mg x1 dose 2. Control arm: Placebo Crossover after 4 weeks 24 pts |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Pain:

a. Mean pain score change 2. Analgesic: a. Mean morphine equivalent change Others: a. Patient and physician preference b. Activity score Withdrawals: 3 for both arms, number excluded for each arm not described No adverse effects reported |

|

| Notes | QS = 5 | |

Ernst 1997.

| Methods | 2 active arms, 1 placebo control

Crossover study: washout period: 2 weeks Pain measurement tool: 15 cm VAS, patient reported Analgesic scale: morphine equivalent for amount consumed in 24 hours |

|

| Participants | Any primary Bone metastases required Pain required Co‐intervention: systemic therapy as part of standard practice Performance status criteria: no specifications Other criteria: exclude radiotherapy, chemotherapy within 4 weeks, cardiac failure, and renal failure. |

|

| Interventions | 1. Active arm 1:

Clodronate

Intravenous

600mg

x1 dose 2. Active arm 2: Clodronate Intravenous 1500 mg x1 dose 3. Control arm: Placebo Crossover after 2 weeks Patients on chemotherapy or hormonal therapy as part of standard care 60 pts |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Pain:

a. Mean change in pain score 2. Analgesic: a. Mean change in morphine equivalent Others: a. Patient preference 26/60 preferred pamidronate 12/60 preferred placebo 8/60 no preference No adverse effects reported Withdrawals: 9 pts |

|

| Notes | QS = 4 | |

Glover 1994.

| Methods | 4 active arms Pain measurement tool: a. 0‐9 point scale [pain severity (0‐3) x pain frequency (0‐3)] severity: 0=none, 1 = mild, 2= moderate, 3= severe frequency: 0=none, 1 = occasionally, 2= >or =1/day, 3 = constant No relief: pain score >/= baseline Definition of pain response (Pain relief score): Complete relief: pain score of 0 Partial relief: pain score <4 Minimal relief: pain score less than baseline but >/=4 Analgesic scale: 0‐9 point scale [ type of medication (0‐3) x frequency (0‐3)] type: 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = mild narcotics, 3= strong narcotics frequency: 0= none, 1 = <daily, 2=once per day, 3= >1per day |

|

| Participants | Breast cancer Bone metastases required Pain required: Pain score >4 (i.e. at least moderate and intermittent) Co‐intervention: May be on chemotherapy or hormonal therapy as part of standard clinical care Performance status criteria: life expectancy >3m Other criteria: exclude changes in chemotherapy/ hormones within 60 days, prior bisphosphonate, treatment for hypercalcemia within 90 days, radiotherapy within 2 weeks, history of hypercalcemia, pathological fractures, cord compression, renal, bone marrow dysfunction, ascites |

|

| Interventions | 1. Active arm 1:

Pamidronate

Intravenous

30 mg every 2 weeks for 3 months

14 pts 2. Active arm 2: Pamidronate Intravenous 60 mg every 4 weeks 17 pts 3. Active arm 3: Pamidronate Intravenous 60 mg every 2 weeks 14 pts 4. Active arm 4: Pamidronate Intravenous 90 mg every 4 weeks 16 pts Chemo/hormonal therapy as part of standard clinical care unchanged at least 60 days |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Pain:

a. Change in mean pain score 2. Analgesic: a. Change in mean pain score Others: a. Urinary calcium/creatinine and hydroxyproline/creatinine ratios, serum osteocalcin and bone alkaline phosphatase b. Bone radiological response Withdrawals: Active arm 1: 5/14 Active arm 2: 2/17 Active arm 3: 1/14 Active arm 4: 2/16 Adverse effects (n = 51 evaluable) Described for all patients in study Fever: 6 Myalgia: 3 Increase pain: 5 |

|

| Notes | QS = 2 | |

Heim 1995.

| Methods | 2 arm study, stratified by stage II vs III, bone involvement vs no bone involvement, high enrolment centers vs low enrolment centers 1 active arm, 1 open control Pain measurement tool: WHO criteria (0‐3), patient reported Analgesic scale: analgesic consumed |

|

| Participants | Multiple myeloma (SII, SIII, and SI pretreated patients) No bone involvement required No pain requirement Co‐intervention: chemotherapy Performance status criteria: life expectancy > 1 year, ECOG 0‐2 Other criteria: exclude no bisphosphonates, no renal dysfunction |

|

| Interventions | 1.Active arm:

Clodronate Oral

1600 mg /day for 1 year

77 pts 2. Control arm: No treatment 80 pts All patients received melphalan and prednisone |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Pain:

at 3 months

85% no pain in Clodronate group

62% no pain in control group 2. Analgesic: a. Proportion with no analgesics Other: a. Bone response b. Incidence of hypercalcemia c. Bone resorption index d. Change in performance status e. Change in serum calcium levels f. Tumor response 13 pts withdrew from the study prior to treatment Adverse effects (WHO criteria) Grade 3‐4 Active: Hemorrhage: 2 Fever: 1 Skin changes: 2 Anorexia: 14 Nausea: 7 Vomiting: 5 Dyspnea: 8 Infection: 6 Diarrhea: 3 Constipation: 2 Heart failure: 8 Cardiac arrhythmia: 2 Control: Hemorrhage: 3 Hematuria: 1 Skin changes: 1 Anorexia: 16 Nausea: 10 Vomiting: 1 Dyspnea: 8 Infection: 7 Diarrhea: 1 Constipation: 1 Allergy: 1 Heart failure: 8 Cardiac arrhythmia: 1 |

|

| Notes | QS = 2 | |

Hortobagyi 1996a.

| Methods | Active vs placebo control stratified by ECOG PS 0,1 vs 2,3 Pain measurement tool: 0‐9 point scale [pain severity (0‐3) x pain intensity (0‐3)] Analgesic scale: 0‐9 point scale |

|

| Participants | Breast cancer Bone metastases required Pain required Co‐intervention: chemotherapy as indicated clinically Performance status criteria: life expectancy > 9 months, ECOG PS </ = 3 Other criteria: exclude previous skeletal complications, hypercalcemia, ascites, renal, liver, cardiac dysfunction, bisphosphonate/radiotherapy within 60 days, calcitonin within 2 weeks. |

|

| Interventions | 1. Active arm:

Pamidronate

Intravenous

90 mg monthly

for 1 year

185 pts 2. Control arm: Placebo 197 pts Chemotherapy as is indicated clinically |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Pain:

a. Change in mean pain score 2. Analgesic: Not an endpoint Others: a. Time to first skeletal complication b. Proportion of patients with skeletal complication c. Performance status d. Change in Spitzer QoL score e. Radiological response f. Changes in urinary and serum markers for bone resorption e. CEA level Withdrawals: Active: 0/185 Control: 2/197 Adverse effects: Active: (withdrawn from study) Weakness: 1 Fatigue: 1 Hypocalcemia: 1 Control: None described |

|

| Notes | QS = 4 Update of these results in Hortobagyi 1998 |

|

Hultborn 1996.

| Methods | Active vs placebo, stratified by center Pain measurement tool: VAS, patient reported |

|

| Participants | Breast cancer Bone metastases required Pain not required Co‐intervention: as clinically indicated Performance status criteria: life expectancy >3 months Other criteria: exclude previous bisphosphonates, hypercalcemia |

|

| Interventions | 1. Active arm:

Pamidronate

Intravenous

60 mg every 4 weeks, up to 2 yrs

201 pts 2. Control arm: Placebo 203 pts |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Pain:

No significant difference between groups Others: a. Skeletal event free survival b. Cumulative incidence of skeletal events c. Hypercalcemia event free time d. Incidence of therapeutic activities for skeletal progression, change of antitumoral treatment e. Pain progression free survival f. Proportion of patients taking opioids Adverse effects (withdrawal from therapy) Active group: 9/201 Control group: 3/203 |

|

| Notes | QS = 2 | |

Koeberle 1999.

| Methods | 2 active arms, stratified by diagnosis (breast vs myeloma), baseline pain intensity (</=40mm Vs >40 mm) Pain measurement tool: a. 10 cm VAS b. PPA (0: no pain, 1: mild, 2: moderate, 3: severe, 4: intractable) (WHO definitions) Pain patient reported Definition of pain response: >/=20% reduction in pain intensity or PPA on 2 consecutive visits Analgesic scale: 0‐5 point scale (WHO) 0: none, 1: mild analgesic, 2: non steroidal anti‐inflammatory 3: opioids 4: opiates Analgesic response criteria: 1 point change in score in 2 consecutive visits or >/=2 point change |

|

| Participants | Any primary Bone metastases required Pain required (>/ = 2), and analgesic score >/ = 2 Co‐intervention: none described Performance status criteria: no specification Other criteria: exclude prior bisphosphonates |

|

| Interventions | 1. Active arm 1 :

Pamidronate

Intravenous

60 mg every 3 weeks

x 6 doses over 18 weeks

35 pts 2. Active arm 2: Pamidronate Intravenous 90 mg every 3 weeks x6 doses over 18 weeks 35 pts |