Abstract

Background

Burn wounds cause high levels of morbidity and mortality worldwide. People with burns are particularly vulnerable to infections; over 75% of all burn deaths (after initial resuscitation) result from infection. Antiseptics are topical agents that act to prevent growth of micro‐organisms. A wide range are used with the intention of preventing infection and promoting healing of burn wounds.

Objectives

To assess the effects and safety of antiseptics for the treatment of burns in any care setting.

Search methods

In September 2016 we searched the Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations), Ovid Embase, and EBSCO CINAHL. We also searched three clinical trials registries and references of included studies and relevant systematic reviews. There were no restrictions based on language, date of publication or study setting.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that enrolled people with any burn wound and assessed the use of a topical treatment with antiseptic properties.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently performed study selection, risk of bias assessment and data extraction.

Main results

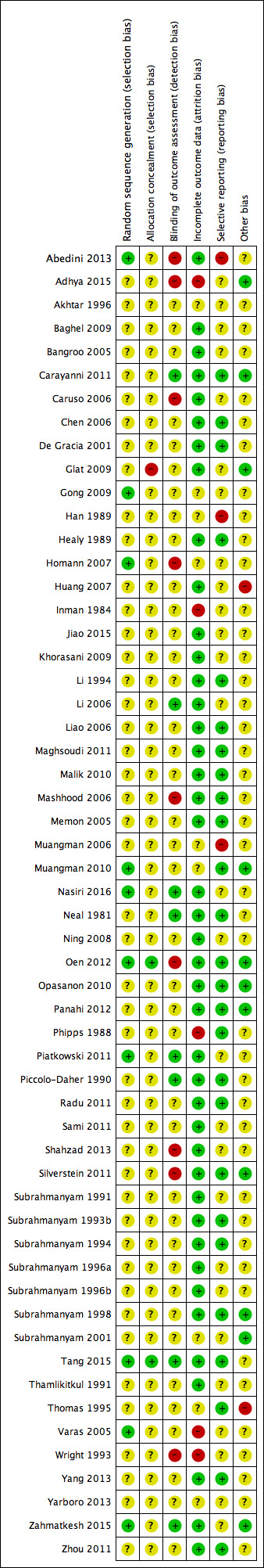

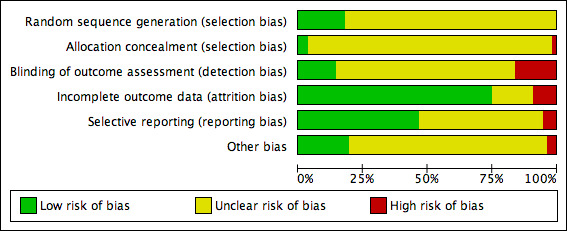

We included 56 RCTs with 5807 randomised participants. Almost all trials had poorly reported methodology, meaning that it is unclear whether they were at high risk of bias. In many cases the primary review outcomes, wound healing and infection, were not reported, or were reported incompletely.

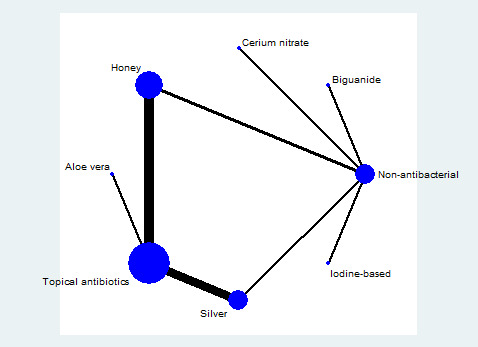

Most trials enrolled people with recent burns, described as second‐degree and less than 40% of total body surface area; most participants were adults. Antiseptic agents assessed were: silver‐based, honey, Aloe Vera, iodine‐based, chlorhexidine or polyhexanide (biguanides), sodium hypochlorite, merbromin, ethacridine lactate, cerium nitrate and Arnebia euchroma. Most studies compared antiseptic with a topical antibiotic, primarily silver sulfadiazine (SSD); others compared antiseptic with a non‐antibacterial treatment or another antiseptic. Most evidence was assessed as low or very low certainty, often because of imprecision resulting from few participants, low event rates, or both, often in single studies.

Antiseptics versus topical antibiotics

Compared with the topical antibiotic, SSD, there is low certainty evidence that, on average, there is no clear difference in the hazard of healing (chance of healing over time), between silver‐based antiseptics and SSD (HR 1.25, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.67; I2 = 0%; 3 studies; 259 participants); silver‐based antiseptics may, on average, increase the number of healing events over 21 or 28 days' follow‐up (RR 1.17 95% CI 1.00 to 1.37; I2 = 45%; 5 studies; 408 participants) and may, on average, reduce mean time to healing (difference in means ‐3.33 days; 95% CI ‐4.96 to ‐1.70; I2 = 87%; 10 studies; 979 participants).

There is moderate certainty evidence that, on average, burns treated with honey are probably more likely to heal over time compared with topical antibiotics (HR 2.45, 95% CI 1.71 to 3.52; I2 = 66%; 5 studies; 140 participants).

There is low certainty evidence from single trials that sodium hypochlorite may, on average, slightly reduce mean time to healing compared with SSD (difference in means ‐2.10 days, 95% CI ‐3.87 to ‐0.33, 10 participants (20 burns)) as may merbromin compared with zinc sulfadiazine (difference in means ‐3.48 days, 95% CI ‐6.85 to ‐0.11, 50 relevant participants). Other comparisons with low or very low certainty evidence did not find clear differences between groups.

Most comparisons did not report data on infection. Based on the available data we cannot be certain if antiseptic treatments increase or reduce the risk of infection compared with topical antibiotics (very low certainty evidence).

Antiseptics versus alternative antiseptics

There may be some reduction in mean time to healing for wounds treated with povidone iodine compared with chlorhexidine (MD ‐2.21 days, 95% CI 0.34 to 4.08). Other evidence showed no clear differences and is of low or very low certainty.

Antiseptics versus non‐antibacterial comparators

We found high certainty evidence that treating burns with honey, on average, reduced mean times to healing in comparison with non‐antibacterial treatments (difference in means ‐5.3 days, 95% CI ‐6.30 to ‐4.34; I2 = 71%; 4 studies; 1156 participants) but this comparison included some unconventional treatments such as amniotic membrane and potato peel. There is moderate certainty evidence that honey probably also increases the likelihood of wounds healing over time compared to unconventional anti‐bacterial treatments (HR 2.86, 95% C 1.60 to 5.11; I2 = 50%; 2 studies; 154 participants).

There is moderate certainty evidence that, on average, burns treated with nanocrystalline silver dressings probably have a slightly shorter mean time to healing than those treated with Vaseline gauze (difference in means ‐3.49 days, 95% CI ‐4.46 to ‐2.52; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 204 participants), but low certainty evidence that there may be little or no difference in numbers of healing events at 14 days between burns treated with silver xenograft or paraffin gauze (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.59 to 2.16 1 study; 32 participants). Other comparisons represented low or very low certainty evidence.

It is uncertain whether infection rates in burns treated with either silver‐based antiseptics or honey differ compared with non‐antimicrobial treatments (very low certainty evidence). There is probably no difference in infection rates between an iodine‐based treatment compared with moist exposed burn ointment (moderate certainty evidence). It is also uncertain whether infection rates differ for SSD plus cerium nitrate, compared with SSD alone (low certainty evidence).

Mortality was low where reported. Most comparisons provided low certainty evidence that there may be little or no difference between many treatments. There may be fewer deaths in groups treated with cerium nitrate plus SSD compared with SSD alone (RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.99; I2 = 0%, 2 studies, 214 participants) (low certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

It was often uncertain whether antiseptics were associated with any difference in healing, infections, or other outcomes. Where there is moderate or high certainty evidence, decision makers need to consider the applicability of the evidence from the comparison to their patients. Reporting was poor, to the extent that we are not confident that most trials are free from risk of bias.

Plain language summary

Antiseptics for Burns

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about whether antiseptics are safe and effective for treating burn wounds.

Background

Burn wounds cause many injuries and deaths worldwide. People with burn wounds are especially vulnerable to infections. Antiseptics prevent the growth of micro‐organisms such as bacteria. They can be applied to burn wounds in dressings or washes, which may help to prevent infection and encourage wound healing. We wanted to find out if antiseptics are more effective than other types of treatment, or whether one antiseptic may be more effective than others, in reducing infection and speeding up healing.

Study characteristics

In September 2016 we searched for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving antiseptic treatments for burn wounds. We included 56 studies with 5807 participants. Most participants were adults with recent second‐degree burns taking up less than 40% of their total body surface area. The antiseptics used included: silver‐based, honey, iodine‐based, chlorhexidine or polyhexanide (biguanides). Most studies compared antiseptics with a topical antibiotic (applied to the skin). A smaller number of studies compared antiseptics with a non‐antibacterial treatment, or with another antiseptic.

Key results

The majority of studies compared antiseptic treatments with silver sulfadiazine (SSD), a topical antibiotic used commonly in the treatment of burns. There is low certainty evidence that some antiseptics may speed up average times to healing compared with SSD. There is also moderate certainty evidence that burns treated with honey probably heal more quickly compared with those treated with topical antibiotics. Most other comparisons did not show a clear difference between antiseptics and antibiotics.

There is evidence that burns treated with honey heal more quickly (high certainty evidence) and are more likely to heal (moderate certainty evidence) compared with those given a range of non‐antibacterial treatments, some of which were unconventional. Burns treated with antiseptics such as nanocrystalline silver or merbromin may heal more quickly on average than those treated with Vaseline gauze or other non‐antibacterial treatments (moderate or low certainty evidence). Comparisons of two different antiseptics were limited but average time to healing may be slightly quicker for wounds treated with povidone iodine compared with chlorhexidine (low certainty evidence). Few participants in the studies experienced serious side effects, but this was not always reported. The results do not allow us to be certain about differences in infection rates. Mortality was low where reported.

Quality of the evidence

Most studies were not well reported and this makes it difficult to be sure if they were at risk of bias. In many cases a single (often small) study provides all the evidence for the comparative effects of the different treatments; and some similar studies provided conflicting results. Where there is moderate or high certainty evidence clinicians will need to consider whether the evidence from the comparison is relevant to their patients.

This plain language summary is up to date as of September 2016.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Silver‐based antiseptics versus topical antibiotics.

| Silver‐based antiseptics versus topical antibiotics | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with burns Intervention: silver‐based antiseptics (primarily dressings) Comparison: topical antibiotics (SSD) Setting: hospitals and burn clinics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with SSD | Risk with silver dressings | |||||

| Wound healing: time to complete healing (time‐to‐event data) | 739 per 1000 | 813 per 1000 (717 to 894) | HR 1.25 (0.94 to 1.67) | 259 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | Only three studies provided sufficient data for an HR; this showed that, on average, there is no clear difference in the 'chance' of healing in burns treated with silver‐based antiseptic dressings compared with SSD. HR calculated using standard methods for two trials |

| Risk difference: 74 more burns healed per 1000 with silver dressings than with SSD (22 fewer to 155 more) | ||||||

| Wound healing (mean time to healing) | The mean time to wound healing was 11.92 days | The mean time to wound healing in the intervention group was 3.33 days shorter (4.96 fewer to 1.70 fewer) | MD ‐3.33 days (‐4.96 to ‐1.70) | 1085 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | Silver may, on average, slightly improve mean time to healing compared with SSD |

| Wound healing (number of healing events) | 784 per 1000 | 917 per 1000 (784 to 1000) | RR 1.17 (1.00 to 1.37) | 408 (5 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low3 | There may be little difference in the number of healing events over short‐term follow‐up (up to 28 days) compared with SSD |

| Risk difference: 133 more burns healed per 1000 with silver dressings than with SSD (0 more to 290 more) | ||||||

| Infection | 151 per 1000 | 127 per 1000 (72 to 222) | RR 0.84 (0.48 to 1.49) | 309 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low4 | It is uncertain whether silver‐containing antiseptics increase or reduce the risk of infection compared with use of SSD as evidence is very low certainty |

| Risk difference: 24 fewer participants with adverse events per 1000 with silver dressings than with SSD (78 fewer to 71 more) | ||||||

| Adverse events | 227 per 1000 | 195 per 1000 (141 to 263) | RR 0.86 (0.63 to 1.18) | 440 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low5 | There may be little or no difference in the number of adverse events in participants treated with silver dressings compared with SSD |

| Risk difference: 34 fewer participants with adverse events per 1000 with silver dressings than with SSD (86 fewer to 29 more). | ||||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio; SSD: silver sulfadiazine | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High: it is very likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research. Moderate: it is likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research, but there is a possibility that it will be substantially different. Low: it is likely that the effect will be substantially different from what was found in the research, but the research provides an indication of what might be expected. Very low: the anticipated effect is very uncertain and the research does not provide a reliable indication of what might be expected. | ||||||

1Not downgraded for risk of selection bias and detection bias because most participants were in a study at low risk of bias; downgraded twice for serious imprecision due to low numbers of participants and wide confidence intervals. 2Downgraded once for high risks of bias across varying domains (variously detection, selection, reporting and other sources of bias in 5 trials representing 31% of the analysis weight); downgraded once for inconsistency (I2 = 78%). A post‐hoc sensitivity analysis excluding studies with unit of analysis issues or intra‐individual designs did not materially effect result. 3Downgraded once due to risk of detection bias in two studies and selection bias in one study (representing in total 53% of the analysis weight); and once due to imprecision. 4Downgraded once for high risks of bias across varying domains (detection, selection and reporting bias affecting 51% of the analysis weight across 3 of 4 studies); downgraded once for indirectness from largest trial outcome (49% analysis weight), which related to inflammation and once due to imprecision. 5Downgraded once for high risks of detection bias affecting 2 studies contributing 93% of analysis weight; downgraded once for imprecision. Studies with intra‐individual design or unit of analysis issue contributed no weight to analysis due to zero events.

Summary of findings 2. Honey versus topical antibiotics.

| Honey versus topical antibiotics | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with burns Intervention: honey Comparison: topical antibiotics (SSD or mafenide acetate) Setting: hospitals and burn clinics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with topical antibiotics | Risk with honey | |||||

| Wound healing: time to complete healing (time‐to‐event data): honey versus SSD or mafenide acetate | 641 per 1000 | 919 per 1000 (827 to 973) | HR 2.45 (1.71 to 3.52) | 580 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | Burns treated with honey probably have a greater 'chance' of healing compared with SSD or mafenide acetate. HR calculated using standard methods for all trials |

| Risk difference: 278 more burns healed per 1000 with honey than with topical antibiotics (185 more to 332 more). | ||||||

| Wound healing (mean time to healing): honey versus SSD | The mean time to wound healing was 15.53 days | The mean time to wound healing was 3.79 days fewer (7.15 fewer to 0.43 fewer) | MD ‐3.79 (‐7.15 to ‐0.43) | 712 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low2 |

It is uncertain what the effect of honey is on mean time to wound healing compared with SSD |

| Wound healing (number of healing events): honey versus SSD | 434 per 1000 | 946 per 1000 (499 to 1000) | RR 2.18 (1.15 to 4.13) | 318 (4 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low3 | There may, on average, be more healing events in burns treated with honey compared with SSD over short‐term follow‐up (maximum 21 days) |

| Risk difference: 512 more burns healed per 1000 with honey than with SSD (65 more to 1358 more) | ||||||

| Incident infection: honey versus SSD or mafenide acetate | 135 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (11 to 158) | RR 0.16 (0.08 to 0.34) | 480 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low4 |

It is uncertain if fewer burns treated with honey may become infected compared with those treated with SSD or mafenide acetate |

| Risk difference: 113 fewer infections (positive swabs in 3 RCTs) per 1000 with honey compared with topical antibiotics (124 fewer to 89 fewer) | ||||||

| Peristent infection: honey versus SSD | 964 per 1000 | 98 per 1000 (48 to 183) | RR 0.10 (0.05 to 0.19) | 170 (2 RCTs) |

||

| Risk difference: 867 fewer persistently positive swabs per 1000 with honey compared with topical antibiotics (961 to 781) | ||||||

| Adverse events: honey versus SSD | 16 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (0 to 64) | RR 0.20 (0.01 to 3.97) | 250 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low5 | It is uncertain whether fewer participants treated with honey experience adverse events compared with those treated with SSD |

| Risk difference: 13 fewer participants with adverse events per 1000 with honey compared with SSD (16 fewer to 48 more) | ||||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio; SSD: silver sulfadiazine | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High: it is very likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research. Moderate: it is likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research, but there is a possibility that it will be substantially different. Low: it is likely that the effect will be substantially different from what was found in the research, but the research provides an indication of what might be expected. Very low: the anticipated effect is very uncertain and the research does not provide a reliable indication of what might be expected. | ||||||

1Downgraded once for imprecision. A post‐hoc sensitivity analysis excluding a study with an intra‐individual design made no material difference to the analysis. 2Downgraded twice for imprecision and once for inconsistency; the downgrading for imprecision is based on the post‐hoc sensitivity analysis excluding a trial with an intra‐individual design. This is a conservative approach to the inclusion of this data. The result of the sensitivity analysis was to produce confidence intervals which included the possibility of both harm and benefit (MD ‐4.36; 95% CI ‐8.90 to 0.16). 3Downgraded once for imprecision and once for inconsistency. 4Downgraded twice for indirectness as the relationship between the surrogate outcome of positive swabs and clinical infection (used in all except one trial) is unclear, and once for imprecision due to low numbers of events. 5Downgraded once because of risks of detection bias in the trial which contributes all the weight in the analysis, and twice because of imprecision.

Summary of findings 3. Aloe vera versus topical antibiotics.

| Aloe Vera versus topical antibiotics | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with burns Intervention: Aloe Vera Comparison: topical antibiotics (SSD or framycetin) Setting: hospitals and burn clinics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with topical antibiotics | Risk with Aloe Vera | |||||

| Wound healing (number of healing events): Aloe Vera versus SSD | 389 per 1000 | 548 per 1000 (272 to 1000) | RR 1.41 (0.70 to 2.85) | 38 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | It is unclear whether Aloe Vera may alter the number of healing events compared with SSD; confidence intervals are wide, spanning both benefits and harms so clear differences between treatments are not apparent |

| Risk difference: 159 more burns healed per 1000 with Aloe Vera than with SSD (117 fewer to 719 more) | ||||||

| Wound healing (mean time to healing): Aloe Vera versus SSD or framycetin | The mean time to wound healing was 21.25 days | The mean time to wound healing was 7.79 days shorter (17.96 shorter to 2.38 longer) | MD ‐7.79 (‐17.96 to 2.38) | 210 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low2 | It is uncertain whether there is a difference in mean time to healing between Aloe Vera and SSD or framycetin. No data were contributed by the trial using framycetin |

| Infection: Aloe Vera versus SSD | 36 per 1000 | 34 per 1000 (9 to 121) | RR 0.93 (0.26 to 3.34) | 221 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3 | It is uncertain whether there is a difference in infection incidence between Aloe Vera and SSD |

| Risk difference: 3 fewer infections per 1000 with Aloe Vera than with SSD (27 fewer to 85 more) | ||||||

| Adverse events | No trial reported evaluable adverse event data for this comparison | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: Risk ratio; SSD: silver sulfadiazine | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High: it is very likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research. Moderate: it is likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research, but there is a possibility that it will be substantially different. Low: it is likely that the effect will be substantially different from what was found in the research, but the research provides an indication of what might be expected. Very low: the anticipated effect is very uncertain and the research does not provide a reliable indication of what might be expected. | ||||||

1Downgraded twice for very serious imprecision. 2Downgraded once for risk of detection bias in a trial accounting for 47% of the analysis weight; once for inconsistency (I2 = 94%) and twice for imprecision. A post‐hoc sensitivity analysis excluding the trial with the intra‐individual design did not materially affect the result of the analysis. 3Downgraded once for risk of detection bias in a trial accounting for 84% of the analysis weight, and twice for imprecision. A post‐hoc sensitivity analysis excluding the trial with the intra‐individual design did not materially affect the result of the analysis.

Summary of findings 4. Iodine versus topical antibiotics.

| Iodine versus topical antibiotics | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with burns Intervention: iodine‐based treatments Comparison: topical antibiotics (SSD) Setting: hospitals and burn clinics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with topical antibiotics | Risk with iodine‐based treatments | |||||

| Wound healing (mean time to healing) | The mean time to wound healing was 20.07 days | The mean time to wound healing in the intervention group was 0.47 days shorter (2.76 shorter to 1.83 longer) | MD ‐0.47 (‐2.76 to 1.83) | 148 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low1 | It is uncertain whether there is a difference in mean time to wound healing between iodine‐based antiseptic treatments and SSD |

| Infection | No study reported evaluable data for infection | |||||

| Adverse events | 350 per 1000 | 301 per 1000 (122 to 735) | RR 0.86 (0.35 to 2.10) | 40 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low2 | It is uncertain whether there is a difference in the proportion of participants with adverse events between iodine‐based antiseptic treatments and SSD |

| Risk difference: 48 fewer participants with adverse events per 1000 with iodine‐based treatments than with SSD (227 fewer to 385 more) | ||||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio; SSD: silver sulfadiazine | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High: it is very likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research. Moderate: it is likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research, but there is a possibility that it will be substantially different. Low: it is likely that the effect will be substantially different from what was found in the research, but the research provides an indication of what might be expected. Very low: the anticipated effect is very uncertain and the research does not provide a reliable indication of what might be expected. | ||||||

1Downgraded once for detection bias in one trial accounting for 61% of the analysis weight and twice for imprecision due to low participant numbers and confidence intervals that cross the line of no effect; one study also had an intra‐individual design, which may not have been accounted for in the analysis, this is taken account of in the double downgrading for imprecision. 2Downgraded once for detection bias in the single trial and twice for imprecision due to fragile confidence intervals, which cross the line of no effect.

Summary of findings 5. Silver versus non‐antibacterial.

| Silver versus non‐antibacterial | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with burns Intervention: silver‐based interventions (dressings) Comparison: non‐antibacterial treatments (dressings and topical treatments) Setting: hospitals and burn clinics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐antibacterial dressing | Risk with silver dressing | |||||

| Wound healing (number of healing events): silver xenograft vs petroleum gauze | 500 per 1000 | 565 per 1000 (295 to 1000) | RR 1.13 (0.59 to 2.16) | 32 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | There may be little or no difference between silver xenograft and petroleum gauze |

| Risk difference: 65 more burns healed per 1000 with silver xenograft compared with petroleum gauze (205 fewer to 580 more) | ||||||

| Wound healing (mean time to healing): silver nanoparticle vs Vaseline gauze | The mean time to wound healing was 15.87 days | The mean time to wound healing in the silver nanoparticle group was 3.49 days shorter (4.46 shorter to 2.52 shorter) compared with gauze | MD ‐3.49 (‐4.46 to ‐2.52) | 204 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 | The mean time to wound healing is probably slightly shorter in the group treated with silver nanoparticle dressing compared with Vaseline gauze |

| Infection | No study reported evaluable data for this comparison | |||||

| Adverse events | No study reported evaluable data for this comparison | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High: it is very likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research. Moderate: it is likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research, but there is a possibility that it will be substantially different. Low: it is likely that the effect will be substantially different from what was found in the research, but the research provides an indication of what might be expected. Very low: the anticipated effect is very uncertain and the research does not provide a reliable indication of what might be expected. | ||||||

1Downgraded twice for imprecision as fragile confidence intervals cross the line of no effect. 2Downgraded once for imprecision due to low numbers of participants.

Summary of findings 6. Honey versus non‐antibacterial.

| Honey versus non‐antibacterial | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with burns Intervention: honey Comparison: non‐antibacterial treatments (dressings and topical treatments) Setting: hospitals and burn clinics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐antibacterial dressing | Risk with honey | |||||

| Wound healing: time to complete healing (time‐to‐event data) | 1000 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (1000 to 1000) | HR 2.86 (1.60 to 5.11) | 164 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | The 'chance' of healing is probably somewhat greater in participants treated with honey compared with unconventional non‐antibacterial treatments |

| Risk difference: 0 difference burns healed per 1000 with honey compared with non‐antibacterial treatments (0 to 0) | ||||||

| Wound healing (mean time to healing) | The mean time to wound healing was 14.05 days | The mean time to wound healing in the intervention group was 5.32 days shorter (6.30 shorter to 4.34 shorter) | MD ‐5.32 (‐6.30 to ‐4.34) | 1156 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Participants treated with honey, on average, have a shorter mean time to healing compared with those treated with a range of treatments without antibacterial properties, including unconventional treatments |

| Infection (incident) | 370 per 1000 | 174 per 1000 (55 to 371) | RR 0.47 (0.23 to 0.98) | 92 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low2 | It is uncertain whether there is a difference in the incidence or persistence of wound infection in participants treated with honey compared with a range of treatments without antimicrobial properties |

| Risk difference: 196 fewer incident infections (persistently positive swabs) per 1000 with honey compared with non‐antibacterial treatments (285 fewer to 7 fewer) | ||||||

| Infection (persistent) | 768 per 1000 | 115 per 1000 | RR 0.15 (0.06 to 0.40) | 147 of 164 randomised (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low2 | |

| Risk difference: 653 fewer persistent infections (persistently positive swabs) per 1000 with honey compared with non‐antibacterial treatments (722 fewer to 461 fewer) | ||||||

| Adverse events | One study reported that there were no events in either intervention group; other studies did not report data that clearly related to the number of participants who experienced adverse events in each group | 239 (3 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3 | It is uncertain whether there is a difference in the incidence of adverse effects between participants treated with honey and those treated with a range of alternative non‐antimicrobial therapies | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High: it is very likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research. Moderate: it is likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research, but there is a possibility that it will be substantially different. Low: it is likely that the effect will be substantially different from what was found in the research, but the research provides an indication of what might be expected. Very low: the anticipated effect is very uncertain and the research does not provide a reliable indication of what might be expected. | ||||||

1Downgraded once for imprecision due to low numbers of participants. 2Downgraded twice for indirectness as swabs are a very surrogate measure of clinical infection and once for imprecision due to low numbers of participants 3Downgraded twice for imprecision and once for indirectness due to low numbers of events and participants and poor reporting of data with uncertainty around applicability to inclusion criteria.

Summary of findings 7. Chlorhexidine versus non‐antibacterial.

| Chlorhexidine versus non‐antibacterial | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with burns Intervention: chlorhexidine Comparison: non‐antibacterial treatments (dressings) Setting: hospitals and burn clinics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐antibacterial dressing | Risk with biguanides | |||||

| Wound healing: time to complete healing (time‐to‐event data): chlorhexidine versus polyurethane | 1000 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (1000 to 1000) | HR 0.71 (0.39 to 1.29) | 51 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | There may be some difference in the 'chance' of healing for chlorhexidine compared with polyurethane but CIs span benefit and harm so a clear difference between treatments is not apparent |

| Risk Difference: 0 difference per 1000 for chlorhexidine compared with polyurethane (0 to 0) | ||||||

| Wound healing (mean time to healing): chlorhexidine versus non‐antibacterial | The mean time to wound healing ‐ chlorhexidine versus polyurethane was 10 days | The mean time to wound healing ‐ chlorhexidine versus polyurethane in the intervention group was 4.08 days longer (0.73 longer to 7.43 longer) | MD 4.08 (0.73 to 7.43) | 51

(1 RCT) 153 participants in 2 RCTs did not have evaluable data |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | The mean time to wound healing may be slightly longer in burns treated with chlorhexidine compared with polyurethane; data from 2 additional RCTs comparing chlorhexidine with hydrocolloid lacked measures of variance |

| Infection: chlorhexidine versus no antimicrobial/no additional antimicrobial | 179 per 1000 | 184 per 1000 (86 to 396) | RR 1.11 (0.54 to 2.27) | 172 (2 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3 | It is uncertain whether there is a difference in the incidence of infection between participants treated with chlorhexidine either alone or in addition to SSD and participants treated with no antimicrobial or SSD alone |

| Risk Difference: 15 more infections per 1000 with chlorhexidine compared with non‐antibacterial treatments (64 fewer to 178 more) | ||||||

| Adverse events: chlorhexidine versus hydrocolloid | 102 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (2 to 168) | RR 0.20 (0.02 to 1.65) | 98 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low4 | It is uncertain whether there is a difference in the number of participants with adverse effects between chlorhexidine and a hydrocolloid dressing |

| Risk Difference: 82 fewer participants with adverse events with chlorhexidine compared with hydrocolloid (100 fewer to 66 more) | ||||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High: It is very likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research. Moderate: It is likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research, but there is a possibility that it will be substantially different. Low: It is likely that the effect will be substantially different from what was found in the research, but the research provides an indication of what might be expected. Very low: The anticipated effect is very uncertain and the research does not provide a reliable indication of what might be expected. | ||||||

1Downgraded twice for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals, which cross the line of no effect, and fragility due to small numbers of participants. 2Downgraded twice for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals, which cross the line of no effect, and fragility due to small numbers of participants. The study with unit of analysis issues did not contribute to the analysis. 3Downgraded once due to risk of detection bias and once due to attrition bias in a trial with 90% of the analysis weight and twice due to imprecision. 4Downgraded once due to risk of detection bias and once due to attrition bias in the single trial; downgraded once for imprecision as confidence intervals cross line of no effect.

Summary of findings 8. Iodine versus non‐antibacterial.

| Iodine‐based treatments versus non‐antibacterial | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with burns Intervention: iodine‐based treatments Comparison: non‐antibacterial treatments (dressings and topical treatments) Setting: hospitals and burn clinics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐antibacterial treatments | Risk with iodine‐based treatments | |||||

| Wound healing (number of healing events): iodophor versus hydrogel | 700 per 1000 | 119 per 1000 (56 to 238) | RR 0.17 (0.08 to 0.34) | 120 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | There may be a smaller number of healing events at 26 days in participants treated with iodophor compared with those treated with hydrogel |

| Risk difference: 581 fewer wounds healed per 1000 at 14 days with iodophor treatment compared with hydrogel (644 fewer to 462 fewer) | ||||||

| Wound healing (mean time to healing): iodine gauze versus carbon fibre | The mean time to wound healing) ‐ iodine gauze versus carbon fibre was 15.29 days | The mean time to wound healing) ‐ iodine gauze versus carbon fibre in the intervention group was 5.38 days longer (3.09 longer to 7.67 longer) | MD 5.38 (3.09 to 7.67) | 277 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low2 | The clinical heterogeneity between these studies, both in terms of interventions and comparators, combined with the wide divergence in effects meant that they could not meaningfully be pooled. It is very uncertain what the effect of iodine compared with non‐antibacterial dressings/topical treatments is on mean time to wound healing |

| Wound healing (mean time to healing): iodophor versus MEBO | The mean time to wound healing) ‐ iodophor versus MEBO was 57 days | The mean time to wound healing) ‐ iodophor versus MEBO in the intervention group was 26 days shorter (30.48 shorter to 21.52 shorter) | MD ‐26.00 (‐30.48 to ‐21.52) | 55 (1 RCT) | ||

| Infection: iodine gauze versus MEBO | 58 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (27 to 208) | RR 1.30 (0.47 to 3.61) | 211 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low3 | There may be little or no difference in the incidence of infection in participants treated with iodine gauze compared with those treated with MEBO |

| Risk difference: 17 more infections per 1000 with iodine gauze compared with MEBO (31 fewer to 151 more) | ||||||

| Adverse effects: iodine gauze versus MEBO | 106 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (32 to 179) | RR 0.71 (0.30 to 1.69) | 211 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low3 | There may be little or no difference in the incidence of adverse effects in participants treated with iodine gauze compared with those treated with MEBO |

| Risk difference: 31 fewer participants with adverse events with iodine gauze compared with MEBO (74 fewer to 73 more) | ||||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; MEBO: moist exposed burn ointment; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High: it is very likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research. Moderate: it is likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research, but there is a possibility that it will be substantially different. Low: it is likely that the effect will be substantially different from what was found in the research, but the research provides an indication of what might be expected. Very low: the anticipated effect is very uncertain and the research does not provide a reliable indication of what might be expected | ||||||

1Downgraded twice for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals and fragility due to small numbers of participants and uncertainty about the analysis of an intra‐individual design. 2Downgraded twice for inconsistency and once for imprecision; there were different directions of effect in the two trials, which it is unclear can be reliably attributed to differences between the treatments although these were present; small numbers of participants in each trial also resulted in imprecision for individual estimates. 3Downgraded twice for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals, which include the possibility of both benefit and harm for the intervention.

Background

Description of the condition

A burn can be defined as an injury to the skin or other organic tissue caused by thermal trauma (Hendon 2002). Burns are caused by heat (including contact with flames, high temperature solids (contact burns) and liquids (scalds)), chemicals, electricity, friction or abrasion, and radiation (including sunburn and radioactivity). Respiratory damage, as a consequence of smoke inhalation, is also considered a type of burn (Hendon 2002).

Incidence and impact

Burn injuries are a considerable source of morbidity and mortality (Mock 2008). As outlined by the World Health Organization (WHO), the burden of injury falls predominantly on people living in low‐ and middle‐income countries; over 95% of the 300,000 annual deaths from fires occur in these countries (Mock 2008). Total burn mortality is inversely correlated with both national income and income inequality (Peck 2013). The much greater number of injuries resulting in disability and disfigurement are also disproportionately concentrated in low‐ and middle‐ income countries (Mock 2008). Fire‐related burns have been estimated to account for 10 million lost disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) every year (WHO 2002), a figure that does not include the social and personal impact of non‐disabling disfigurement.

Additional mortality and morbidity are caused by other types of burns including scalding, and electrical and chemical burns (American Burn Association 2013). Globally, children and young people, and women are disproportionately affected by burn injuries, while the types and causes of injury in children differ somewhat from those seen in adults (Peck 2012).

Although, both incidence of burns and associated morbidity and mortality are much lower in high‐income countries, they are nevertheless significant. Annually in the UK around 250,000 people suffer a burn; 175,000 attend a hospital emergency department with a burn and, of these, approximately 13,000 are admitted to hospital and 300 die (National Burn Care Review 2001). In the USA, the figures for those receiving medical treatment were 450,000 with 40,000 hospitalisations and 3400 deaths (American Burn Association 2013). These data indicated that, in contrast to the global pattern, a majority of people with burns were male (69%), and while children aged under five years accounted for 20% of all cases, 12% were people aged 60 years or older (American Burn Association 2013).

Burn severity and extent

The severity of burns is categorised by the depth of the tissues affected; in the case of burns to the skin, this is the layers of cells in the skin (Demling 2005). Epidermal burns (sometimes known as first‐degree burns) are confined to the epidermis (outer surface of the skin), are not usually significant injuries, and heal rapidly and spontaneously. Partial‐thickness burns (sometimes known as second‐degree burns) involve varying amounts of the dermis (skin) and may become deeper and heal with varying amounts of scarring, which will be determined partly by the depth of the burn. Partial‐thickness burns are divided into superficial and deep partial‐thickness wounds: superficial partial‐thickness burns extend into the papillary or superficial upper layer of the dermis, whilst deep partial‐thickness burns extend downward into the reticular (lower) layer of the dermis. Full‐thickness burns (sometimes known as third‐degree burns) extend through all the layers of the skin. Where full‐thickness burns extend beneath the skin layers, into underlying structures (fat, muscle, bone); they are sometimes called full‐thickness and/or fourth‐degree burns) (Demling 2005; European Practice Guidelines 2002).

The age of people with burns affects their prognosis, with infants and older people having poorer outcomes (Alp 2012; DeSanti 2005). The area of a burn will also be key to the time taken to heal, and also to the risk of infection (Alp 2012). Burn size is determined by the percentage of the total body surface area that is burned; estimating this can be difficult, particularly in children; the most accurate method uses the Lund and Browder chart (Hettiaratchy 2004).

The depth of burn and its location may be predictors of psychological, social, and physical functioning following treatment (Baker 1996). Most extensive burns are a mixture of different depths, and burn depth can change and increase in the acute phase after the initial injury; the extent to which this occurs will depend on the effectiveness of the initial treatment (resuscitation) (Hettiaratchy 2004).

Burn wound infection

Infections are a potentially serious complication in people with burns. US data indicated that over a 10‐year period more than 19,000 complications in people with burns were reported. While 31% of these were recorded as pulmonary complications, 17% were wound infections, or cellulitis, or both, and 15% were recorded as septicaemia (a serious, life‐threatening illness caused by bacteria in the bloodstream) or other infectious complications (Latenser 2007). We were unable to locate other large‐scale international data for infection‐related complication rates.

Up to 75% of all burn deaths following initial resuscitation are a consequence of infection rather than more proximal causes such as osmotic shock and hypovolaemia (types of changes in the concentration of fluids in the body) (Bang 2002; Fitzwater 2003). Although this figure includes other types of hospital/healthcare‐acquired infections such as pneumonia, a substantial proportion follow an infection which would meet accepted criteria for infections of burn wounds (Alp 2012; Peck 1998). Burn wound infections also contribute to morbidity, lengthening recovery times, and increasing the extent of scarring (Church 2006; Oncul 2009), as well as the pain experienced by people with burns (Tengvall 2006).

All open wounds offer an ideal environment for microbial colonisation. Most wounds will contain some micro‐organisms but this will not necessarily lead to adverse events (AWMA 2011). Recently the view has developed that it is infection with sufficient or specific types of pathogenic micro‐organisms, or both, and possibly resulting biofilms (Percival 2004; Wolcott 2008) that may lead to negative outcomes and, potentially, delayed healing (Bowler 2003; Davies 2007; Madsen 1996; Trengove 1996). Biofilms are formed by bacteria that grow on a surface to form a film of cells. Growing in this way can make them more resistant to bactericidal agents. Previously it was thought that the critical factor was a threshold concentration of microbes (bioburden) (Robson 1968). However, the impact of microbial colonisation on wound healing is not independent of the host response. The ability of the host to provide adequate immune response is likely to be as critical, if not more so, in determining whether a wound becomes infected as the specifics of the flora in the wound.

People with burns have a particular vulnerability to infection, as a result of the loss of the physical barrier to infection, and the reduction in immunity mediated by the lost cells (Ninnemann 1982; Winkelstein 1984). Infections commonly occur in the acute period following the burn (Church 2006).

The spectrum of infective agents that can be present in the burn wounds varies. Nowadays, Gram‐positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), and Gram‐negative bacteria such as Pseudomona aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) are the predominant pathogens (Wibbenmeyer 2006), although other micro‐organisms such as fungi, yeasts, and viruses can also be present (Church 2006; Polavarapu 2008). Multidrug‐resistant micro‐organisms, such as methicillin‐resistant S. aureus (MRSA), are frequently and increasingly identified in burns (Church 2006; DeSanti 2005; Keen 2010).

Description of the intervention

Standard care

The care for burn wounds is determined in part by their severity (depth), area, and location (National Network for Burn Care 2012). For significant injuries involving the lower layers of skin, standard care may involve a range of dressings or skin substitutes, or both, (Wasiak 2013) and more complex interventions such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy and negative pressure wound therapy (Dumville 2012; Villanueva 2004). The nature and extent of the burn wound, together with the type and amount of colonising micro‐organisms can also influence the risk of invasive infection (Bang 2002; Fitzwater 2003).

Antiseptics

Antiseptics are topical antimicrobial agents which are thought to prevent the growth of pathogenic micro‐organisms without damaging living tissue (Macpherson 2004). Applications broadly fall into two categories: lotions used for wound irrigation or cleaning, or both, with a brief contact time (unless used as a pack/soak), and products that are in prolonged contact with the wound such as creams, ointments, and impregnated dressings (BNF 2016).

Agents used primarily for wound irrigation/cleaning across wound types are commonly based on povidone‐iodine, chlorhexidine and peroxide agents. Less commonly used are traditional agents such as gentian violet and hypochlorites. Longer contact creams and ointments include fusidic acid, mupirocin, neomycin sulphate and iodine (often as cadexomer iodine). Some of these are rarely used in clinical practice. Silver‐based products such as silver sulfadiazine and silver‐impregnated dressings are increasingly used, as are honey‐based products. Aloe Vera is also sometimes used as an antiseptic although there is currently no available sterile source.

The British National Formulary (BNF) categorises antimicrobial dressings under honey‐based, iodine‐based, silver‐based, and other, which includes dressings impregnated with agents such as chlorhexidine or peroxides (BNF 2016). The choice of dressing for a burn wound is based on a number of factors including the need to accommodate movement, the minimisation of adherence to the wound surface, the prevention of infection, the ability to absorb wound fluid and maintain humidity, and the active promotion of healing (Wasiak 2013).

Antibiotics are substances that destroy or inhibit the growth of bacteria (Macpherson 2004) (normally by inhibiting deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), protein synthesis or by disrupting the bacterial cell wall). Routine prophylaxis against infection with systemic antibiotics is not currently recommended. While it may reduce burn wound infections, or colonisation, or both, it does not decrease mortality, and may in fact increase the risk of selecting resistant micro‐organisms such as MRSA (Avni 2010; Barajas‐Nava 2013)

In contrast, antiseptics (the focus of this review) can be bactericidal (in that they kill micro‐organisms) or they can work by slowing the growth of organisms (bacteriostatic) (Macpherson 2004), but they usually work without damaging living tissue. Antiseptics can reduce the presence of other micro‐organisms such as viruses and fungi, as well as bacteria, and often work by damaging the surface of microbes (Macpherson 2004). According to the BNF (BNF 2016) antiseptics are used to reduce the presence of micro‐organisms on living tissue.

How the intervention might work

This review considers the use of antiseptics for both clinically infected and non‐infected burn wounds. The rationale for treating clinically infected wounds with antiseptic agents is to kill or slow the growth of the pathogenic micro‐organisms, thus preventing an infection from worsening and spreading (Kingsley 2004). In the case of burns, the prevention of infections, and systemic infections in particular, is especially important, as people with burns can have lowered immunity as a consequence of their injury (Church 2006). Improved healing may also result, although evidence on the association between wound healing and infection is limited (Jull 2015; O'Meara 2001; Storm‐Versloot 2010).

There is a widely held view that wounds that do not have clear signs of clinical infection, but that have characteristics such as retarded healing, may also benefit from a reduction in bacterial load (bioburden). Again, evidence for this is limited (AWMA 2011; Howell‐Jones 2005).

Why it is important to do this review

Burn wounds are a source of substantial morbidity and mortality; much of this results from the original wound becoming infected (Latenser 2007). While infections pose real risks to people with burns, the problem of antibiotic and multi‐drug resistance in bacteria continues to grow (Church 2006; DeSanti 2005; Keen 2010); alternatives to routine use of antibiotics for the minimisation of infection can be a key element of care.

There is a current published Cochrane review of antibiotics for the prevention (prophylaxis) of burn wound infection (Barajas‐Nava 2013), while a second Cochrane review of antibiotics for the treatment of infected burn wounds is now underway (Lu 2016). This review of antiseptics complements these reviews and will complete the assessment of evidence for agents with antimicrobial properties in the care of all burn wounds, whether infected or not. There will be some overlap between this review and other Cochrane and non‐Cochrane reviews of dressings for partial‐thickness burns (Wasiak 2013), and of individual agents with antiseptic properties for all types of wounds (Aziz 2012; Jull 2015; Storm‐Versloot 2010). However, this review will provide a single synthesis of the randomised evidence relating to all antiseptics for any type of burn wound.

Objectives

To assess the effects and safety of antiseptics for the treatment of burns in any care setting.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included published and unpublished randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐RCTs, irrespective of language of report. We planned to only include crossover trials if they reported outcome data at the end of the first treatment period, prior to crossover. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies.

Types of participants

We included studies enrolling participants of any age with burn wounds. We included burns of any type, severity, extent or current infection status, managed in any care setting. We accepted authors' definitions of the category of burn represented in included trials. We included trials of participants with burns, alongside people with other types of wounds where the participants with burns constituted at least 75% of the trial population.

Types of interventions

The interventions of interest were topical antiseptic agents. We included any RCT in which the use of a specific topical antiseptic was the only systematic difference between treatment groups; where the antiseptic agent was an integral part of the dressing we allowed for this. Control regimens could have included placebo, an alternative antiseptic, another therapy such as antibiotics or isolation of the patient, standard care or no treatment. We included studies that evaluated intervention schedules, including other therapies, provided that these treatments were delivered in a standardised way across the trial arms. We excluded trials in which the presence or absence of a specific antiseptic was not the only systematic difference. We also excluded evaluations of antiseptics used to prepare for the surgical treatment of burns (i.e. where antisepsis is part of the perioperative procedure).

We anticipated that likely comparisons would include use of different antiseptic agents, in particular, the use of different types of dressings impregnated with antiseptic agents; comparisons of impregnated dressings or other antiseptic preparations with standard care; and comparison of antiseptics with topical or systemic antibiotics. We anticipated that other elements of standard care may have been co‐interventions across trial arms.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary effectiveness outcome for this review was wound healing. Trialists use a range of different methods of measuring and reporting this outcome. We considered that RCTs that reported one or more of the following provided the most relevant and rigorous measures of wound healing:

time to complete wound healing (correctly analysed using survival, time‐to‐event approaches). Ideally the outcome would be adjusted for appropriate covariates e.g. baseline wound area/degree/duration;

proportion of wounds completely healed during follow‐up (frequency of complete healing).

We used and reported the study authors’ definitions of complete wound healing where this was available. We reported outcome measures at the latest time point available (assumed to be length of follow‐up if not specified) and the time point specified in the methods as being of primary interest (if this was different from latest time point available).

Where both the outcomes above were reported, we presented all data in a summary outcome table for reference, but focused on reporting time to healing. When time to healing was analysed as a continuous measure, but it was not clear whether all wounds healed, we documented the use of the outcome in the study, but we did not extract, summarise or use the data in any meta‐analysis.

The primary safety outcome for the review was change in wound infection status (as defined by the study authors). In the case of wounds that were considered to be clinically infected at baseline, we assessed resolution of infections. In the case of wounds that were not considered to be clinically infected at baseline, we assessed the incidence of new infections. We also assessed the incidence of septicaemia, where data permitted. We did not extract data on microbiological assays not clearly linked to a diagnosis of infection.

Secondary outcomes

We included the following secondary outcomes:

-

Adverse events

Where reported, we extracted data on all serious adverse events and all non‐serious adverse events. We did not report individual types of adverse events other than pain (see below) or infection (see Primary outcomes).

-

Health‐related quality of life

We included quality of life where it was reported, using a validated scale such as the SF‐36 or EQ‐5D, or a validated disease‐specific questionnaire. Ideally, reported data were adjusted for the baseline score.

-

Pain (including pain at dressing change)

We included pain only where mean scores with a standard deviation were reported using a scale validated for the assessment of pain levels, such as a visual analogue scale (VAS).

-

Resource use (when presented as a mean with standard deviation)

We included measures of resource use such as number of dressing changes, number of nurse visits, length of hospital stay, and need for other interventions.

Costs associated with resource use (including estimates of cost‐effectiveness)

Mortality (overall and infection‐related).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases to identify relevant RCTs:

the Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register (searched 26 September 2016);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library, 2016, Issue 8, searched 26 September 2016);

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to 26 September 2016);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations) (searched 26 September 2016);

Ovid Embase (1974 to 26 September 2016);

EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1982 to 28 September 2016)

The search strategies are shown in Appendix 1.

We combined the Ovid MEDLINE search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximising version (2008 revision) (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the Embase search with the Ovid Embase filter developed by the UK Cochrane Centre (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the CINAHL searches with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN 2015). There were no restrictions with respect to language, date of publication or study setting.

We also searched the following clinical trials registries.

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov/).

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx).

EU Clinical Trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/).

Searching other resources

We tried to identify other potentially eligible trials or ancillary publications by searching the reference lists of retrieved included trials, as well as relevant systematic reviews, meta‐analyses and health technology assessment reports.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

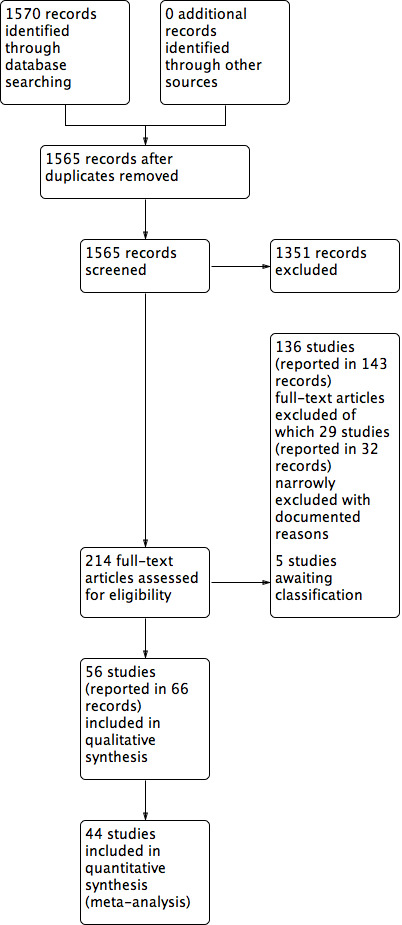

Two review authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the citations retrieved by the searches for relevance. After this initial assessment, we obtained full‐text copies of all studies considered to be potentially relevant. Two review authors independently checked the full papers for eligibility; we resolved disagreements by discussion and, where required, the input of a third review author. We obtained translation support, where necessary, for non‐English language reports. Where the eligibility of a study was unclear, we attempted to contact study authors. We recorded all reasons for exclusion of studies for which we had obtained full copies. We completed a PRISMA flowchart to summarise this process (Liberati 2009).

Where studies were reported in multiple publications/reports, we attempted to obtain all publications. Whilst we included each study only once in the review, we extracted data from all reports to ensure that we obtained all available relevant data.

Data extraction and management

We extracted and summarised details of the eligible studies. Where possible we extracted data by treatment group for the prespecified interventions and outcomes in this review. Two review authors independently extracted data; discrepancies were resolved through discussion or by consultation with a third reviewer. Where data were missing from reports, we attempted to contact the study authors and request this information.

Where we included a study with more than two intervention arms, we only extracted data from intervention and control groups that met the eligibility criteria. Where the reported baseline data related to all participants, rather than to those in relevant treatment arms, we extracted the data for the whole trial and noted this. We collected outcome data for relevant time points as described in the Types of outcome measures.

Where possible, we extracted the following data:

bibliographic data, including date of completion/publication;

country of origin;

unit of randomisation (participant/wound);

unit of analysis;

trial design e.g. parallel, cluster;

care setting;

number of participants randomised to each trial arm and number included in final analysis;

eligibility criteria and key baseline participant data including cause, depth, extent (area/proportion of total body surface area (TBSA)) and location of burns; ages of participants, and whether they had a diagnosis of infection at baseline;

details of treatment regimen received by each group;

duration of treatment;

details of any co‐interventions;

primary and secondary outcome(s) (with definitions and, where applicable, time points);

outcome data for primary and secondary outcomes (by group);

duration of follow‐up;

number of withdrawals (by group) and number of withdrawals (by group) due to adverse events;

publication status of study;

source of funding for trial.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed included studies using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011a). This tool addresses specific domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete data, selective outcome reporting and other issues. In this review we recorded issues with unit of analysis, for example where a cluster trial has been undertaken but analysed at the individual level in the study report.

We assessed blinding of outcome assessment and completeness of outcome data for each of the review outcomes separately. We presented our assessment of risk of bias using two 'Risk of bias' summary figures; one is a summary of bias for each item across all studies, and a second shows a cross‐tabulation of each trial by all of the risk of bias items.

We summarised a study’s risk of selection bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and other bias. In many of the comparisons included in this review, we anticipated that blinding of participants and personnel may not be possible. For this reason the assessment of the risk of detection bias focused on whether blinded outcome assessment was reported (because wound healing can be a subjective outcome, it can be at high risk of measurement bias when outcome assessment is not blinded). For trials using cluster randomisation, we also planned to consider risk of bias for recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, loss of clusters, incorrect analysis and comparability with individually‐randomised trials (Higgins 2011b) (Appendix 3).

Measures of treatment effect

We reported time‐to‐event data (e.g. time‐to‐complete wound healing) as hazard ratios (HRs) when possible, in accordance with the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011). If studies reporting time‐to‐event data (e.g. time to healing) did not report an HR, then, when feasible, we estimated this using other reported outcomes, such as numbers of events, through the application of available statistical methods (Parmar 1998; Tierney 2007). This included deriving an HR from data reported for multiple time points, where at least three time points were reported. Where no HR could be calculated, we reported dichotomous data at the latest time point. For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous outcome data, we used the difference in means (MD) with 95% CIs for trials that used the same assessment scale. When trials used different assessment scales, we used the standardised difference in means (SMD) with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

Where studies were randomised at the participant level and outcomes measured at the wound level, for example for wound healing, we treated the participant as the unit of analysis when the number of wounds assessed appeared to be equal to the number of participants (e.g. one wound per person).

One unit of analysis issue that we anticipated was that randomisation may have been carried out at the participant level, with the allocated treatment used on multiple wounds per participant (or perhaps only on some participants), but data were presented and analysed per wound (clustered data).

In cases where included studies contained some or all clustered data, we reported this, noting whether data had been (incorrectly) treated as independent. We recorded this as part of the 'Risk of bias' assessment.

We also included studies with the split‐body design where either people with two similar burn wounds were enrolled and each burn wound was randomised to one of the interventions, or where one half of a wound was randomised to one treatment and the other half to a different treatment. These approaches are similar to the 'split‐mouth' approach (Lesaffre 2009). These studies should be analysed using paired data which reflects the reduced variation in evaluating different treatments on the same person. However, it was often not clear whether such analysis had been undertaken. This lack of clarity is noted in the 'Risk of bias' assessment and in the notes in the Characteristics of included studies table

We adopted a pragmatic but conservative post‐hoc approach to analyses including clustered and paired data. We included such studies in meta‐analyses where possible (where unadjusted clustered data would produce too‐narrow CIs and unadjusted paired data too‐wide CIs). We undertook a post‐hoc sensitivity analysis to explore the impact of including data that had been inappropriately unadjusted. Where the sensitivity analysis produced a materially different result to the primary analysis, we used this as the basis for the GRADE assessment and the 'Summary of findings' table. Where we pooled studies with paired data with one other trial, we also reported the results of both trials individually, and where a paired data study was the sole trial reporting outcome data, we noted the issues related to its design. We also noted where these trials were included in meta‐analyses but did not contribute weight to the analyses due to zero events or lack of measures of variance.

Dealing with missing data

It is common to have data missing from trial reports. Excluding participants from the analysis post randomisation, or ignoring participants who are lost to follow‐up compromises the randomisation and potentially introduces bias into the trial. If it was thought that study authors might be able to provide some missing data, we attempted to contact them; however, data are often missing because of loss to follow‐up. In individual studies, when data on the proportion of burns healed were presented, we assumed that randomly‐assigned participants not included in an analysis had an unhealed wound at the end of the follow‐up period (i.e. they were considered in the denominator but not in the numerator). When a trial did not specify participant group numbers before dropout, we presented only complete case data. For time‐to‐healing analysis using survival analysis methods, dropouts should be accounted for as censored data. Hence all participants will be contributing to the analysis. We acknowledge that such analysis assumes that dropouts are missing at random and there is no pattern of missingness. We presented data for all secondary outcomes as a complete case analysis.

For continuous variables (e.g. length of hospital stay) and for all secondary outcomes, we presented available data from the study reports/study authors and did not impute missing data. Where measures of variance were missing, we calculated these, wherever possible (Higgins 2011a). If calculation was not possible, we contacted the study authors. Where these measures of variation remained unavailable and we could not calculate them, we excluded the study from any relevant meta‐analyses that we conducted.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Assessment of heterogeneity can be a complex, multi‐faceted process. Firstly, we considered clinical and methodological heterogeneity; that is the degree to which the included studies varied in terms of participants, interventions, outcomes, and characteristics such as length of follow‐up. We supplemented this assessment of clinical and methodological heterogeneity by information regarding statistical heterogeneity ‐ assessed using the Chi² test (we considered a significance level of P < 0.10 to indicate statistically significant heterogeneity) in conjunction with the I² statistic (Higgins 2003). I² examines the percentage of total variation across RCTs that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins 2003). Very broadly, we considered that I² values of 25%, or less, may mean a low level of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003), and values of 75% or more, indicated very high heterogeneity (Deeks 2011). Where there was evidence of high heterogeneity, we attempted to explore this further (see Data synthesis).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. Publication bias is one of a number of possible causes of 'small study effects', that is, a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller RCTs. Funnel plots allow a visual assessment of whether small study effects may be present in a meta‐analysis. A funnel plot is a simple scatter plot of the intervention effect estimates from individual RCTs against some measure of each trial’s size or precision (Sterne 2011). Funnel plots are only informative when there are a substantial number of studies included in an analysis; we had planned to present funnel plots for meta‐analyses that included at least 10 RCTs using Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) (RevMan 2014) but there were no analyses with sufficient studies.

Data synthesis

We combined details of included studies in narrative review according to the comparison between intervention and comparator, the population and the time point of the outcome measurement. We considered clinical and methodological heterogeneity and undertook pooling when studies appeared appropriately similar in terms of burn type and severity, intervention type and antibacterial agent, duration of treatment and outcome assessment.

In terms of a meta‐analytical approach, in the presence of clinical heterogeneity (review author judgement), or evidence of statistical heterogeneity, or both, we used a random‐effects model. We planned to only use a fixed‐effect approach when clinical heterogeneity was thought to be minimal and statistical heterogeneity was estimated as non‐statistically significant for the Chi2 value and 0% for the I2 assessment (Kontopantelis 2013). We adopted this approach as it is recognised that statistical assessments can miss potentially important between‐study heterogeneity in small samples, hence the preference for the more conservative random‐effects model (Kontopantelis 2012). Where clinical heterogeneity was thought to be acceptable, or of interest, we considered conducting meta‐analysis even when statistical heterogeneity was high, but attempted to interpret the causes behind this heterogeneity and considered using meta‐regression for that purpose, if possible (Thompson 1999; Thompson 2002).

We presented data using forest plots, where possible. For dichotomous outcomes we presented the summary estimate as a RR with 95% CIs. Where continuous outcomes were measured in the same way across studies, we planned to present a pooled MD with 95% CIs; we pooled SMD estimates where studies measured the same outcome using different methods. For time‐to‐event data, we plotted (and, where appropriate, pooled) estimates of HRs and 95% CIs, as presented in the study reports, using the generic inverse variance method in RevMan 5 (RevMan 2014). Where time to healing was analysed as a continuous measure, but it was not clear if all wounds healed, we documented use of the outcome in the study, but did not summarise the data or use the data in any meta‐analysis.

'Summary of findings' tables

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined and the sum of available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach defines the 'certainty' of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The certainty of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2011b). We presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables:

time‐to‐complete wound healing, when analysed using appropriate survival analysis methods;

proportion of wounds completely healing during the trial period;

mean time to healing when all wounds healed;

changes in clinical infection status;

adverse events.

Where comparisons had limited available data for specified outcomes we did not generate a 'Summary of findings' table for this comparison. Instead we decided to present these data together with GRADE judgements in an additional table, in order to keep the 'Summary of findings' tables section of the review manageable and improve readability.

In terms of the GRADE assessment, when making decisions for the risk of bias domain we downgraded only when studies had been classed at high risk of bias for one or more domains. We did not downgrade for unclear risk of bias assessments. In assessing the precision of effect estimates we assessed the size of confidence intervals, downgrading twice for imprecision when there were very few events and CIs around effects included both appreciable benefit and appreciable harm. We considered CI to be especially fragile where there were fewer than 50 participants; event rates were also considered in determining fragility.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When possible, we planned to perform subgroup analyses to explore the effect of interventions in children under the age of 18, in adults, and in older adults (aged over 65 years). When possible, we also planned to use subgroup analyses to assess the influence of burn size and depth on effect size. If there had been sufficient data these analyses would have assessed whether there were differences in effect sizes for burns of different depths.