Abstract

Background

Cancer patients are 1.4 times more likely to be unemployed than healthy people. Therefore it is important to provide cancer patients with programmes to support the return‐to‐work (RTW) process. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2011.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at enhancing RTW in cancer patients compared to alternative programmes including usual care or no intervention.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, in the Cochrane Library Issue 3, 2014), MEDLINE (January 1966 to March 2014), EMBASE (January 1947 to March 2014), CINAHL (January 1983 to March, 2014), OSH‐ROM and OSH Update (January 1960 to March, 2014), PsycINFO (January 1806 to 25 March 2014), DARE (January 1995 to March, 2014), ClinicalTrials.gov, Trialregister.nl and Controlled‐trials.com up to 25 March 2014. We also examined the reference lists of included studies and selected reviews, and contacted authors of relevant studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of the effectiveness of psycho‐educational, vocational, physical, medical or multidisciplinary interventions enhancing RTW in cancer patients. The primary outcome was RTW measured as either RTW rate or sick leave duration measured at 12 months' follow‐up. The secondary outcome was quality of life.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion, assessed the risk of bias and extracted data. We pooled study results we judged to be clinically homogeneous in different comparisons reporting risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We assessed the overall quality of the evidence for each comparison using the GRADE approach.

Main results

Fifteen RCTs including 1835 cancer patients met the inclusion criteria and because of multiple arms studies we included 19 evaluations. We judged six studies to have a high risk of bias and nine to have a low risk of bias. All included studies were conducted in high income countries and most studies were aimed at breast cancer patients (seven trials) or prostate cancer patients (two trials).

Two studies involved psycho‐educational interventions including patient education and teaching self‐care behaviours. Results indicated low quality evidence of similar RTW rates for psycho‐educational interventions compared to care as usual (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.35, n = 260 patients) and low quality evidence that there is no difference in the effect of psycho‐educational interventions compared to care as usual on quality of life (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.2 to 0.3, n = 260 patients). We did not find any studies on vocational interventions. In one study breast cancer patients were offered a physical training programme. Low quality evidence suggested that physical training was not more effective than care as usual in improving RTW (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.32 to 4.54, n = 28 patients) or quality of life (SMD ‐0.37, 95% CI ‐0.99 to 0.25, n = 41 patients).

Seven RCTs assessed the effects of a medical intervention on RTW. In all studies a less radical or functioning conserving medical intervention was compared with a more radical treatment. We found low quality evidence that less radical, functioning conserving approaches had similar RTW rates as more radical treatments (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.09, n = 1097 patients) and moderate quality evidence of no differences in quality of life outcomes (SMD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.23, n = 1028 patients).

Five RCTs involved multidisciplinary interventions in which vocational counselling, patient education, patient counselling, biofeedback‐assisted behavioral training and/or physical exercises were combined. Moderate quality evidence showed that multidisciplinary interventions involving physical, psycho‐educational and/or vocational components led to higher RTW rates than care as usual (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.16, n = 450 patients). We found no differences in the effect of multidisciplinary interventions compared to care as usual on quality of life outcomes (SMD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.20 to 0.25, n = 316 patients).

Authors' conclusions

We found moderate quality evidence that multidisciplinary interventions enhance the RTW of patients with cancer.

Plain language summary

Interventions to enhance return‐to‐work for cancer patients

Research question

What is the best way to help cancer patients get back to work when compared to care as usual?

Background

Each year more and more people who get cancer manage to get through treatment alive. Many cancer survivors live well, although they can continue to experience long‐lasting problems such as fatigue, pain and depression. These long‐term effects can cause problems with cancer survivors' participation in working life. Therefore, cancer is a significant cause of absence from work, unemployment and early retirement. Cancer patients, their families and society at large all carry part of the burden. In this Cochrane review we evaluated how well cancer patients can be helped to return to work.

Study characteristics

The search date was 25 March 2014. Fifteen randomised controlled trials including 1835 cancer patients met the inclusion criteria. We found four types of interventions. In the first, psycho‐educational interventions, participants learned about physical side effects, stress and coping and they took part in group discussions. In the second type of physical intervention participants took part in exercises such as walking. In the third type of intervention, participants received medical interventions ranging from cancer drugs to surgery. The fourth kind concerned multidisciplinary interventions in which vocational counselling, patient education, patient counselling, biofeedback‐assisted behavioral training and/or physical exercises were combined.We did not find any studies on vocational interventions aimed at work‐related issues.

Key results

Results suggest that multidisciplinary interventions involving physical, psycho‐educational and/or vocational components led to more cancer patients returning to work than when they received care as usual. Quality of life was similar. When studies compared psycho‐educational, physical and medical interventions with care as usual they found that similar numbers of people returned to work in all groups.

Quality of the evidence

We found low quality evidence of similar return‐to‐work rates for psycho‐educational interventions compared to care as usual. We also found low quality evidence showing that physical training was not more effective than care as usual in improving return‐to‐work. We also found low quality evidence that less radical cancer treatments had similar return‐to‐work rates as more radical treatments. Moderate quality evidence showed multidisciplinary interventions involving physical, psycho‐educational and/or vocational components led to higher return‐to‐work rates than care as usual.

Summary of findings

Background

The number of people who survive cancer is increasing (American Cancer Society 2015; de Boer 2014; Hoffman 2005) due to the sustained improvements in strategies to detect cancer early and treat it effectively. Since the population is ageing in most countries and cancer survival is prolonged, the prevalence of cancer survivors is expected to rise further in the future (Aziz 2007). In the absence of other competing causes of death, 68% of adults now diagnosed with cancer can expect to be alive five years post‐diagnosis (American Cancer Society 2015).

Cancer diagnoses in working age people are becoming more common, with almost half of the adult cancer survivors aged less than 65 years (Short 2005; Verdecchia 2009). Each year an estimated 14.1 million new cases of cancer are diagnosed worldwide (American Cancer Society 2015) and thus approximately seven million working‐age people are diagnosed with cancer each year.

Many survivors do well in general terms, although a significant proportion of survivors continue to experience physical, emotional and social problems such as fatigue, pain, cognitive deficits, anxiety and depression, which may become chronic or persistent (Cooper 2013; Smith 2007). These long‐term medical and psychological effects of cancer or its treatment may cause impairments that diminish social functioning, including obtaining or retaining employment (Cooper 2013; Mehnert 2013; Taskila 2007a). Fortunately, many cancer patients are both willing and able to return‐to‐work (RTW) following treatment (Taskila 2007a) without residual disabilities (Steiner 2010).

Returning to work is important for both cancer patients themselves and society. From the viewpoint of society, it is economically imperative to encourage patients to RTW whenever possible (Verbeek 2007). From the individual point of view, employment is an important component of quality of life (QoL) (de Boer 2014). Work is invaluable as it can provide a sense of purpose, dignity and an income thus enabling people to support themselves and their families. There is strong evidence that good work is beneficial for physical and mental health, whereas unemployment and long‐term sickness absence have a harmful impact (Marmot 2012). This also applies to cancer patients who consider returning to work very important (Mehnert 2013; Verbeek 2007) because it is regarded as a marker of complete recovery (Spelten 2002) and regaining normality (Kennedy 2007). Moreover, returning to work can improve cancer patients' QoL and it can have a positive effect on self‐esteem and social or family roles (Verbeek 2007).

Since 1980, several studies have documented the impact of cancer on employment and they have reported approximately 60% (ranging from 30% to 93%) of the cancer patients returning to work after one to two years (Mehnert 2011; Spelten 2002; Taskila 2007a). However, cancer patients can experience problems getting back to work (Feuerstein 2007). Overall, cancer survivors are 1.4 times more likely to be unemployed than healthy controls although the rate differs depending on the diagnosis (de Boer 2009). Some studies have stated that cancer patients may experience impairments in mental and physical health as a result of their illness, and that these impairments sometimes lead to a decrease in their ability to work (Short 2005). More specifically, work ability of cancer patients who work at the time of their diagnosis is severely impaired in the first months of treatment but does improve in the months afterwards (de Boer 2008). Beyond the first months, a Finnish study found that 26% of the cancer patients reported deteriorated physical work ability and 19% deteriorated mental work ability, two to six years after diagnosis (Taskila 2007b).

Therefore, it is important to provide employed cancer patients with programmes to support their RTW process. A recent Macmillan report has proposed that successful vocational rehabilitation can have a major impact on cancer patients' capability to RTW and remain in work life (Macmillan 2013). There has been increasing interest in improving RTW outcomes for people with cancer. Thus it is reasonable to expect that more studies of interventions with vocational aspects for cancer patients have been conducted since the publication of the first version of this review in 2011 (De Boer 2011).

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at enhancing RTW in cancer patients compared to alternative programmes including usual care or no intervention.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all eligible randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster‐RCTs.

Types of participants

We limited the population to adults (≧ 18 years old) who had been diagnosed with cancer and were in paid employment (employee or self‐employed) at the time of diagnosis. We included studies conducted with people who had any type of cancer diagnosis.

Types of interventions

We included any type of intervention aiming to enhance RTW. Interventions may have been carried out either with an individual or in a group and in a clinical setting or in the community. Interventions could primarily focus on different factors which influence RTW, such as coping (in psycho‐educational interventions), workplace adjustments (in vocational interventions), physical exercises (in physical interventions), minimal surgery (in medical interventions) or on a combination of those factors (in multidisciplinary interventions). Thereby we divided interventions into:

Psycho‐educational: interventions that included any type of psycho‐educational intervention such as counselling, education, training in coping skills, and problem solving therapy (PST), undertaken by any qualified professional (e.g. psychologist, social worker or oncology nurse).

Vocational: interventions that included any type of intervention focused on employment. Vocational interventions might be person‐directed or work‐directed. Person‐directed vocational interventions are aimed at the patient and incorporate programmes which aim to encourage RTW, vocational rehabilitation, or occupational rehabilitation. Work‐directed vocational interventions are aimed at the workplace and include workplace adjustments such as modified work hours, modified work tasks, or modified workplace and improved communication with or between managers, colleagues and health professionals.

Physical: interventions that included any type of physical training (such as walking), physical exercises (such as arm lifting) or training of bodily functions (such as vocal training).

Medical or pharmacological: interventions that incorporated any type of medical intervention (e.g. surgical) or medication (such as hormone treatment).

Multidisciplinary: any combination of psycho‐educational, vocational, physical and medical interventions.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Our primary outcome was RTW. RTW included return to either full‐ or part‐time employment, to the same or a reduced role and to either the previous job or any new employment. We extracted two types of RTW data:

RTW measured as event data such as RTW rates or (change in) disability pension rates.

RTW measured as time‐to‐event data, such as number of days between reporting sick and any work resumption or the number of days on sick leave during the follow‐up period.

We extracted outcome data from the follow‐up measurement. When study authors reported multiple follow‐up measurements, we extracted the 12‐month follow‐up data.

Secondary outcomes

QoL which included overall QoL, physical QoL and emotional QoL measured with validated and unvalidated questionnaires.

We extracted outcome data from the follow‐up measurement. When study authors reported multiple follow‐up measurements, we extracted the 12‐month follow‐up data.

Search methods for identification of studies

This is an update of the Cochrane review: Interventions to enhance return‐to‐work for cancer patients (De Boer 2011). We considered studies published in any language.

Electronic searches

First, we identified relevant trials from the following sources:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, in the Cochrane Library Issue 3, 2014).

MEDLINE (1966 to 25 March 2014).

EMBASE (1947 to 25 March 2014).

CINAHL (1983 to 25 March 2014).

OSH‐ROM and OSH Update (Occupational Safety and Health, 1960 to 25 March 2014).

PsycINFO (1806 to 25 March 2014).

Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE, 1995 to 25 March 2014).

ClinicalTrials.gov, accessed 25 March 2014.

Trialregister.nl, accessed 25 March 2014.

Controlled‐trials.com, accessed 25 March 2014.

We selected cancer‐related and work–related search terms from an earlier meta‐analysis on cancer and employment (de Boer 2006). We based all systematic searches in electronic databases on the MEDLINE search strategy (Appendix 1) using the revised Cochrane RCT filter (Robinson 2002) and the sensitive search of the Cochrane Occupational Safety and Health Group for retrieving studies of occupational health interventions. For future review updates we will only use the RCT filter. We adapted the search to fit the specifications for CENTRAL, EMBASE, CINAHL, OSH‐ROM, PsycINFO (Appendix 2) and DARE(Appendix 3) . Searches on cancer and employment tended to result in many studies on occupational exposure, occupational diseases and biological research. Therefore, we used a set of search terms to exclude those studies.

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of all studies that we retrieved as full papers and the reference lists of all retrieved systematic and narrative reviews in order to identify other potentially eligible studies. We wrote to the corresponding authors of all identified studies that fulfilled our inclusion criteria but provided insufficient data to request any additional published or unpublished study that may be relevant to this Cochrane review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (AdB, TT) independently screened all titles and abstracts of studies that we identified from the search strategy for inclusion and appropriateness based on the selection criteria. Review authors were not blinded to the name(s) of the author(s), institution(s) or publication source at any level. If the title and abstract provided sufficient information to decide that it did not satisfy the inclusion criteria, we excluded the study. When there was a difference of opinion, a third review author (JV) arbitrated. We documented the reasons for exclusion at this stage. Two review authors (AdB, TT) independently examined the full‐text articles of the included studies to determine which studies fulfilled all inclusion criteria. Where necessary, we contacted study authors for further information. Again, a third review author (JV) arbitrated in case of a difference of opinion. We documented the reasons for exclusion at this stage as well. We discussed reasons for inclusion and exclusion of studies of the two review authors and listed these reasons in the Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Data extraction and management

We constructed a data extraction form that enabled two review authors (AdB, TT) to independently extract the following data from the studies: study type, setting, country, recruitment, randomisation, blinding, funding, inclusion and exclusion criteria, number of patients, patient characteristics including diagnosis, medical treatment, sociodemographic data, and employment situation at baseline, intervention (content, duration, provider, discipline, context), co‐interventions, follow‐up time and follow‐up measurements, number of patients lost to follow‐up, RTW outcome measures used, statistical methods, and results for each RTW outcome measure at each follow‐up measurement point for each group. We summarised the diagnoses in diagnostic groups such that if at least 50% of the patients had a specific diagnosis then we included the study in that specific cancer diagnostic group; otherwise we designated it as mixed diagnoses. We discussed all the results of data extraction by the two independent review authors and we entered study data relevant to this review into RevMan 2014.

We entered the details of the interventions into an additional, Table 5, in RevMan 2014.

1. Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Country | Diagnosis | Design | Number | Intervention(s) | Control | Type |

| Ackerstaff 2009 | Netherlands | Head, neck | RCT | 34 versus 28 | Intra‐arterial chemoradiation | Intravenous chemoradiation | Medical |

| Berglund 1994 | Sweden | Breast | RCT | 81 versus 73 | Physical training, patient education and training of coping skills re RTW | Care as usual | Multidisciplinary |

| Burgio 2006 | USA | Prostate | RCT | 28 versus 29 | Biofeedback behavioral training | Care as usual | Multidisciplinary |

| Emmanouilidis 2009 | Germany | Thyroid | RCT | 7 versus 6 | L‐thyroxine after surgery | Later provision of L‐thyroxine | Medical |

| Friedrichs 2010 | Germany | Leukemia | RCT | 163 versus 166 | Peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation | Bone marrow transplantation | Medical |

| Hillman 1998 | USA | Laryngeal | RCT | 80 versus 63 | Chemotherapy | Laryngectomy | Medical |

| Hubbard 2013 | UK | Breast | RCT | 7 versus 11 | Physical, occupational, psycho‐educational support services, multi‐disciplinary | Booklet work and cancer | Multidisciplinary |

| Johnsson 2007 | Sweden | Breast | RCT | 53 versus 17 55 versus 17 64 versus 17 |

|

No endocrine therapy | Medical |

| Kornblith 2009 | USA | Endometrial | RCT | 164 versus 73 | Laparoscopy | Laparotomy | Medical |

| Lee 1992 | UK | Breast | RCT | 44 versus 47 | Breast conservation | Mastectomy | Medical |

| Lepore 2003 | USA | Prostate | RCT | 41 versus 20 43 versus 20 |

|

Care as usual | Psycho‐educational |

| Maguire 1983 | UK | Breast | RCT | 42 versus 46 | Physical training, individual counselling and encouragement of RTW. | Care as usual | Multidisciplinary |

| Purcell 2011 | Australia | Radiotherapy patients | RCT | 43 versus 48 21 versus 24 |

|

Flyer with generic information about fatigue. | Psycho‐educational |

| Rogers 2009 | USA | Breast | RCT | 14 versus 14 | Physical activity training | Care as usual | Physical |

| Tamminga 2013 | Netherlands | Breast | RCT | 65 versus 68 | Vocational support, counselling, education, multi‐disciplinary, RTW advice. | Care as usual | Multidisciplinary |

When an article reported more than one intervention and compared each intervention against a control group, we entered each intervention as a separate evaluation.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (AdB, TT) assessed the included studies' risk of bias independently according to the procedures described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed each included study within ten domains of risk of bias: adequacy of sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding, how incomplete outcome data (drop‐outs) were addressed, use of intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis, similarity of baseline characteristics, similarity or avoidance of co‐interventions, acceptability of compliance, similarity of the timing of outcome assessments, and evidence of selective outcome reporting.

We judged studies to have a low overall risk of bias when we judged five or more of the domains to have a low risk of bias.

We used a sample of three included studies to test whether the two review authors (AdB, TT) applied the assessment criteria consistently. We followed any disagreement about the criteria by a discussion until we reached consensus. If we could not resolve the difference of opinion, we consulted a third review author (JV). We discussed all the results of the two independent review authors and reported one final assessment of risk of bias for each study.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, such as RTW rates, we used risk ratios (RRs) as the measure of treatment effect. For continuous variables, such as the number of days on sick leave during the follow‐up period, we used the mean difference (MD). For QoL outcomes, we calculated standardised mean difference (SMD) values. All estimates included a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Unit of analysis issues

For trials with multiple arms and if two or more interventions were compared with the same control group in one meta‐analysis, we divided the number of patients in the control group equally over the intervention studies, i.e. we halved the number of control patients if there were two intervention groups.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors of the following studies to obtain data that were missing in their report that we needed to assess eligibility of the studies or as input for meta‐analysis, or both: Ackerstaff 2009; Emmanouilidis 2013; Jones 2005; Rogers 2009; Tamminga 2013; and Wiggins 2009 . All of these study authors kindly provided the information we requested. If statistics were missing, such as standard deviations (SDs) we calculated them from other available statistics such as P values according to the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first decided whether or not studies were sufficiently homogeneous to be able to synthesize the results into one summary‐measure. We defined studies to be sufficiently homogeneous when they had similar designs, similar interventions and similar outcomes measured at the same follow‐up point.

We considered the following categories of interventions as sufficiently similar to be combined: psycho‐educational, vocational, physical, medical and multidisciplinary interventions.

We considered both RTW outcomes and sick leave duration outcomes as similar enough to be combined. We considered general QoL outcomes measured with different instruments similar enough to be merged. We combined different diagnoses within one analysis because we hypothesized that the mechanism of RTW interventions is similar over the different cancer diagnoses.

We also tested for statistical heterogeneity with the I² statistic. We considered studies to be statistically heterogeneous if the I² statistic was greater than 50%.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed publication bias with a funnel plot when more than five studies were available for a particular comparison.

Data synthesis

We pooled studies with sufficient data that we judged to be clinically homogeneous with RevMan 2014. We combined studies that were statistically heterogeneous with a random‐effects model; otherwise we used a fixed‐effect model.

For RTW outcomes, we aimed at combining rate of RTW, which is a dichotomous measure, and the number of days on sick leave, which is a continuous measure. Therefore, we calculated effect sizes in order to enter them in the same comparison. For studies with continuous outcomes, we calculated the SMD using RevMan 2014. We subsequently expressed SMDs as log odds ratios by multiplying them by 1.814 (Chinn 2000) as is the recommended method in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). For studies with dichotomous RTW rates, we recalculated the risk ratios (RRs) into odds ratios (ORs) and then into log odds ratios. Next, we calculated for both types of studies the standard errors (SE) of the log odds ratios from the 95% CI of the log odds ratios. We used the formula: SE = (upper limit log odds ratio ‐ lower limit log odds ratio)/3.92, as is the recommended method in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We then used these log odds ratios and their SEs as input into the meta‐analysis using the generic inverse variance method as implemented in RevMan 2014.

Since RTW rates in cancer patients are much higher than 10%, the ORs overestimate the treatment effect considerably. Therefore we recalculated the ORs back into risk ratios using the formula: RR = OR/((1‐P0)+(P0*OR)) as recommended by Zhang 1998. In this formula, OR refers to the pooled OR produced by RevMan 2014 and P0 to the incidence in the non‐exposed group. P0 was estimated from the studies reporting dichotomous RTW rates by selecting the median P0 of the non‐exposed group from these studies.

GRADE assessment

Finally, we used the GRADE approach to assess the quality of the evidence per comparison and per outcome, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Starting from an assumed level of high quality, we reduced the quality of the evidence by one or more levels if there were one or more limitations in the following domains: risk of bias, consistency, directness of the evidence, precision of the pooled estimate and the possibility of publication bias. Thus, we rated the level of evidence as either high, moderate, low or very low depending on the number of limitations. For the most important comparisons and outcomes, we used the programme GRADEpro GDT 2015 to generate 'Summary of findings' tables. We present the results of our GRADE assessment in Table 6.

2. Quality of the evidence (GRADE).

| Comparison/outcome | Number of studies | Study limitations | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Overall quality of evidence |

| Psycho‐educational versus Care as usual/ RTW |

2 RCTs | Yes: 1 high 1 low risk 1 level down |

No inconsistency | No | Wide CI 1 level down |

Only two studies | Low |

| Physical versus Care as usual/ RTW |

1 RCT | No: Low risk | No | No | Wide CI 2 levels down |

Only one study | Low |

| Medical function conserving versus Medical more radical/ RTW |

7 RCTs | No: 2/7 high risk studies contribute 25% | High: I² statistic = 51% | No | Wide CI 1 level down |

Not observed | Low |

| Multidisciplinary physical, psycho‐educational and/or vocational interventions versus Care as usual/ RTW |

5 RCTs | Yes: 3/5 high risk 1 level down |

No: I² statistic = 0% | No | Narrow CIs | Not observed | Moderate |

| Psycho‐educational versus Care as usual/QoL | 2 RCTs | Yes: 1 high, 1 low risk 1 level down |

No: I² statistic = 0% | No | Wide CI 1 level down |

Only two studies | Low |

| Physical versus Care as usual/ QoL |

1 RCT | No: Low risk | Not applicable | No | Wide CI 1 level down |

Only one study | Low |

| Medical function conserving versus Medical more radical/QoL | 2 RCTs | No: Low risk studies | No: I² statistic = 0% | No | Wide CI 1 level down |

Only two studies | Moderate |

| Multidisciplinary physical, psycho‐educational and/or vocational interventions versus Care as usual/QoL | 2 RCTs | Yes: 1 low, 1 high risk studies 1 level down |

No: I² statistic = 17% | No | Wide CI 1 level down |

Only two studies | Low |

Column headings (with explanations in parentheses): Study design (RCT = randomised controlled trial); study limitations (likelihood of reported results not being an accurate estimate of the truth); inconsistency (lack of similarity of estimates of treatment effects); indirectness (not representing PICO well); imprecision (insufficient number of patients or wide CIs) of results; and publication bias (probability of selective publication of trials and outcomes) across all studies that measured that particular outcome.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We intended to perform further subgroup analyses according to diagnosis. However, the number of studies in the subgroups was too low to perform such subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We intended to analyse how sensitive our results were to the risk of bias in the included studies. However, there was an insufficient number of studies available per comparison to do such an analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

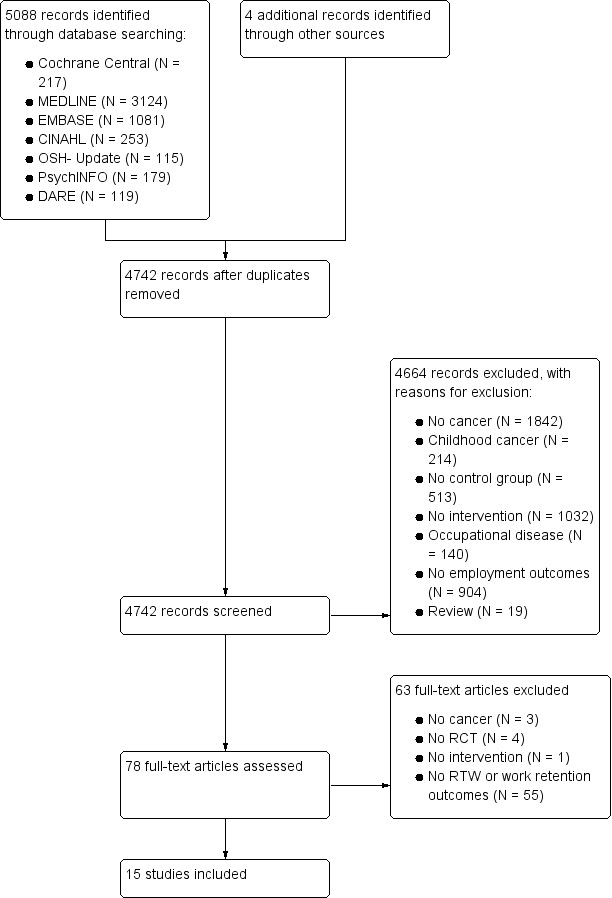

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA study flow diagram of included and excluded studies. Through a comprehensive literature search of electronic databases, we identified a total of 5088 potentially relevant records with most (61%) retrieved by MEDLINE. After removing duplicates, we screened a total of 4742 potentially relevant references for eligibility. We excluded a total of 4664 references based on the title and abstract, with the most frequent reasons for exclusion being: 1) study not aimed at cancer patients (39%); 2) study does not assess the effectiveness of an intervention (22%); and 3) no RTW outcomes reported (19%). Other reasons were: no control group (11%); study involved survivors of childhood cancer (5%); study was aimed at cancer as an occupational disease (3%); or study is a review (0.5%).

1.

PRISMA flow diagram of reference selection and study inclusion.

From our search of the websites ClinicalTrials.gov, Trialregister.nl and Controlled‐trials.com we identified three ongoing RCT studies (NCT00639210; NCT01799031; NTR2138) which are listed in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

We also checked the reference lists of 19 retrieved systematic and narrative reviews (Beck 2003; De Backer 2009; Egan 2013; Fors 2011; Haaf 2005; Harvey 1982; Hersch 2009; Hoving 2009; Irwin 2004; Kirshblum 2001; Kirshbaum 2007; Liu 2009; McNeely 2006; Oldervoll 2004; Scott 2013; Silver 2013; Stanton 2006; Steiner 2010; van der Molen 2009) to identify additional potentially eligible studies. We found four additional titles of potentially eligible studies.

We contacted the corresponding authors of six studies that fulfilled our inclusion criteria but did not provide sufficient data to request any additional relevant published or unpublished study data. Based on the information kindly provided by the trial authors, we included three studies (Ackerstaff 2009; Rogers 2009; Tamminga 2013) and excluded three studies (Emmanouilidis 2013; Gordon 2005; Wiggins 2009). We also checked the reference lists of all studies that we retrieved as full papers in order to identify further potentially eligible studies but did not identify any additional studies.

Included studies

Characteristics of studies and participants

We included 15 studies describing RCTs. Of these, three had multiple study arms and thus we included 19 evaluations of interventions, which we entered as separate evaluations in RevMan 2014. These studies included a total of 1835 participants. Table 5 gives an overview of the main characteristics of the 15 studies and 19 evaluations. All included studies were conducted in high income countries, with most describing research from the United States of America (USA) (N = 5) while another nine studies were conducted in Europe (UK (N = 3); Sweden (N = 2); the Netherlands (N = 2); Germany (N = 2)) and Australia (N = 1). Seven studies aimed interventions at breast cancer patients (Berglund 1994; Hubbard 2013; Johnsson 2007; Lee 1992; Maguire 1983; Rogers 2009; Tamminga 2013). Two studies involved prostate cancer patients (Burgio 2006; Lepore 2003) and one study each showed results for thyroid cancer patients (Emmanouilidis 2009), gynaecological patients (Kornblith 2009), head and neck cancer patients (Ackerstaff 2009), laryngeal cancer patients (Hillman 1998), leukaemia patients (Friedrichs 2010) and mixed cancer diagnoses patients (Purcell 2011).

Funding sources were charities (Berglund 1994; Hubbard 2013; Johnsson 2007; Lee 1992; Maguire 1983; Rogers 2009), national institutes (Burgio 2006; Hillman 1998; Kornblith 2009; Lepore 2003; Purcell 2011; Tamminga 2013), were not received (Emmanouilidis 2009; Friedrichs 2010) or not reported (Ackerstaff 2009). For further details regarding the study populations and settings see the Characteristics of included studies table.

Type of RTW interventions

This Cochrane Review reports on the results of two psycho‐educational interventions, one physical intervention, seven medical interventions and five multidisciplinary interventions which were a combination of psycho‐educational, vocational and/or physical interventions. We did not find any vocational interventions nor multidisciplinary interventions that included a medical intervention.

Psycho‐educational interventions

The psycho‐educational intervention study by Lepore 2003 included one study arm on patient education alone and one on combination of patient education and group discussion. The intervention that only included patient education involved lectures delivered by an expert on things such as physical side effects, stress and coping which was compared with care as usual. In a second intervention group, group discussions to improve coping were added to the patient education and also compared to care as usual. The article by Purcell 2011 describes education aimed at teaching patients self‐care behaviours to reduce cancer‐related fatigue. Pre‐radiotherapy programme was delivered one week prior to radiotherapy planning and the post‐radiotherapy programme was delivered one to two weeks after radiotherapy completion.

Physical interventions

The physical intervention in Rogers 2009 included a moderate walking programme. This training programme included an individually supervised exercise session, face‐to‐face counselling sessions with an exercise specialist, and home‐based exercises.

Medical interventions

The seven medical interventions were diverse and were aimed at intra‐arterial chemoradiation (Ackerstaff 2009), thyroid stimulating hormones after surgery (Emmanouilidis 2009), chemotherapy (Hillman 1998), adjuvant endocrine therapy (Johnsson 2007), laparoscopy (Kornblith 2009), breast conservation (Lee 1992), and peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation (Friedrichs 2010). Ackerstaff 2009 compared a group of head and neck patients receiving intra‐arterial cisplatin infusion versus a group receiving the standard intravenous chemoradiation. Another RCT evaluated the effect of the use of recombinant human TSH directly after thyroidectomy, hence avoiding hypothyroidism compared to the use of recombinant human TSH after a period of withholding thyroid hormones (Emmanouilidis 2009). Three RCTs studied the effect of an intervention using minimal surgery compared to more radical surgery with RTW as one of the outcomes. Hillman 1998 compared chemotherapy and surgery and Kornblith 2009 compared laparoscopy and laparotomy whereas Lee 1992 compared conservation surgery to mastectomy in breast cancer patients. Johnsson 2007 compared minimal adjuvant treatment (no medication) with the administration of three different types of adjuvant endocrine therapy on RTW in breast cancer patients. Friedrichs 2010 compared the effects of peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation with bone‐marrow transplantation in leukaemia patients.

Multidisciplinary interventions

The five included multidisciplinary interventions involved vocational counselling, patient education, patient counselling, biofeedback‐assisted behavioral training and/or physical exercises. In Maguire 1983 a nurse advised breast cancer patients on exercise, examined arm movements, checked exercises, and encouraged RTW and becoming socially active. The Berglund 1994 study combined training of coping skills regarding RTW with psychical activity exercises while the Burgio 2006 study combined physical exercise with behavioural biofeedback. In the Hubbard 2013 study a case manager working in a multidisciplinary team referred cancer patients to physical, occupational or psychological support services. Patients in the Tamminga 2013 study were supported by an oncology nurse or medical social worker working in a multidisciplinary team who provided them with vocational support, counselling, education and RTW advice.

Setting, design and outcomes

Thirteen studies were conducted in a hospital, one study was set in the community (Rogers 2009) and in one study the setting was not reported (Berglund 1994). All fifteen studies employed a RCT design.

RTW was measured as event rates, such as RTW rates in 11 studies (Ackerstaff 2009; Berglund 1994; Burgio 2006; Friedrichs 2010; Hillman 1998; Johnsson 2007; Lee 1992; Lepore 2003; Maguire 1983; Purcell 2011; Tamminga 2013). Four studies reported time‐to‐event data, such as number of days between reporting sick and any work resumption or the number of days on sick leave during the follow‐up period (Emmanouilidis 2009; Hubbard 2013; Kornblith 2009; Rogers 2009). QoL was measured as a secondary outcome in eight RCTs (Ackerstaff 2009; Berglund 1994; Burgio 2006; Kornblith 2009; Lepore 2003; Purcell 2011; Rogers 2009; Tamminga 2013). Seven of these measured QoL with validated questionnaires: EORTC (Ackerstaff 2009), SF‐36 (Burgio 2006, Kornblith 2009; Lepore 2003; Tamminga 2013), EQ‐5D (Purcell 2011), and FACT‐B (Rogers 2009) and one used an unvalidated questionnaire (Berglund 1994).

Excluded studies

Of the 4742 potentially relevant records, we retrieved 78 studies for more detailed evaluation. Of these 78 full‐text studies, we excluded 63 because the intervention was not aimed at cancer patients (N = 3), the study design was not RCT (N = 4) or the article did not describe an intervention (N = 1). We excluded 55 studies because they did not report any RTW outcomes. Of these 55 studies, six trials used the vocational environment scale instead of RTW and three studies used the outcome return to normal activity including household tasks, social and family roles. We excluded one study of a contacted author (Emmanouilidis 2013) because it was based on the same data as an earlier, included study (Emmanouilidis 2009). For a detailed description of the reasons for exclusion see the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

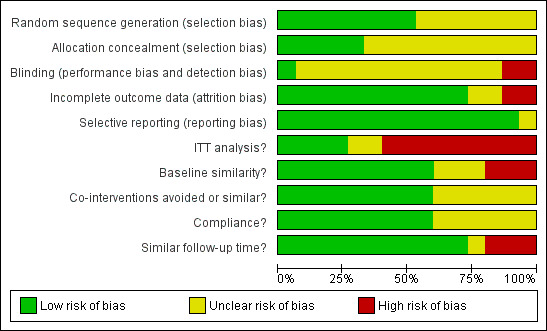

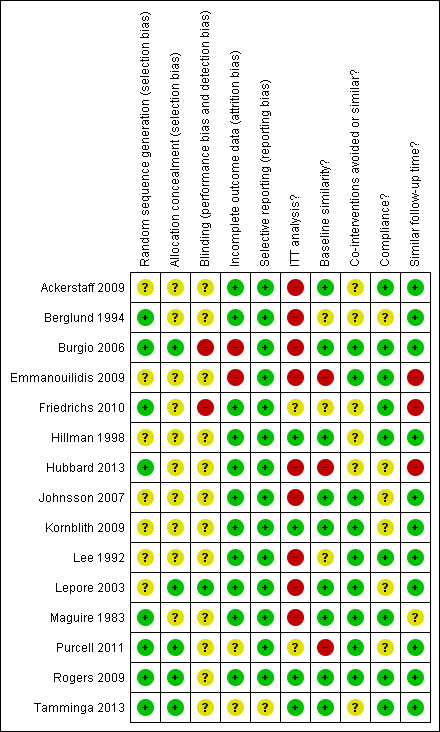

Risk of bias in included studies

For results of 'Risk of bias' assessment of RCTs, see the Characteristics of included studies table. The results are summarised in the 'Risk of bias' graph (Figure 2) which is an overview of the review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. Figure 3 shows the 'Risk of bias' summary of each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study.

Allocation

Of the 15 included studies describing a RCT, eight studies reported adequate random sequence generation or adequate allocation concealment, or both (Berglund 1994; Burgio 2006; Friedrichs 2010; Hubbard 2013; Maguire 1983; Purcell 2011; Rogers 2009; Tamminga 2013). The trial authors reported having used random numbers generated by a computer or random number tables. According to our judgment, allocation was adequately concealed in all of these studies because a research nurse or an independent interviewer performed the randomisation.

Blinding

Twelve of the 15 RCTs did not report any information on blinding of either the patients, the people performing the intervention or the assessors of the outcomes. Lepore 2003 reported blinding the interviewer assessing the outcomes and blinding the patients for the hypothesis. Two studies explicitly reported that patients and intervention providers were not blinded (Burgio 2006; Friedrichs 2010).

Incomplete outcome data

Thirteen studies reported reasons for drop‐out of the patients and thus addressed the issue of incomplete outcome data. Burgio 2006 did not provide any information about patients with missing data whereas Emmanouilidis 2009 reported not having any drop‐outs. There was no adequate adjustment for confounding in the analyses because 11 studies did not perform ITT analyses. Three studies performed ITT analyses between the two randomised groups even if the patients changed over to the other group (Hillman 1998; Rogers 2009; Tamminga 2013), and in one study 21% of the patients changed over to the control group but the trial authors still performed ITT analyses (Kornblith 2009).

Selective reporting

We judged all included RCT studies to be free of selective reporting of the outcomes because the trial authors reported all outcomes described in the methods.

Other potential sources of bias

Baseline characteristics of the patients were similar in 12 studies, except for Emmanouilidis 2009, Hubbard 2013 and Purcell 2011. However, five studies included a heterogeneous group of patients but obviously could only perform the analyses on employment outcomes in patients employed at baseline. Separate data on the similarity of baseline characteristics on these groups of employed patients were not given (Burgio 2006; Hillman 1998; Kornblith 2009; Lepore 2003; Rogers 2009). Two studies stated that baseline characteristics were similar but did not report the actual data (Lee 1992; Maguire 1983). One study provided no baseline characteristics (Berglund 1994) and in one study the baseline characteristics were significantly different (Emmanouilidis 2009).

Co‐interventions were avoided or similar in both groups in all included studies. Compliance with the intervention was not always reported but was satisfactory in those studies that did report it (Ackerstaff 2009; Burgio 2006; Emmanouilidis 2009; Friedrichs 2010; Hillman 1998; Lee 1992; Rogers 2009; Tamminga 2013). Follow‐up time was similar in all studies except for Emmanouilidis 2009, Friedrichs 2010 and Hubbard 2013 and unclear in Maguire 1983.

Overall risk of bias in studies

We rated nine studies as having a low overall risk of bias (Ackerstaff 2009; Hillman 1998; Johnsson 2007; Kornblith 2009; Lee 1992; Lepore 2003; Maguire 1983; Rogers 2009; Tamminga 2013). We rated six studies (Berglund 1994; Burgio 2006; Emmanouilidis 2009; Friedrichs 2010; Hubbard 2013; Purcell 2011) as having a high overall risk of bias because they had less than five domains at low risk of bias (Table 6; Figure 3).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Multidisciplinary physical, psycho‐educational and/or vocational interventions versus Care as usual for cancer.

| Multidisciplinary physical, psycho‐educational and/or vocational interventions versus Care as usual for cancer | |||||

| Patient or population: Patients with cancer Settings: Hospital Intervention: Multidisciplinary physical, psycho‐educational and/or vocational interventions versus Care as usual | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Control | Multidisciplinary physical, psycho‐educationaland/or vocational interventions versus Care as usual | ||||

| RTW Follow‐up: median 12 months | 786 per 10001 | 872 per 1000 (810 to 912) | RR 1.11 (1.03 to 1.16) | 450 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 |

| QoL Follow‐up: mean 12 months | ‐ | The mean QoL in the intervention groups was 0.03 standard deviations higher (0.20 lower to 0.25 higher) | ‐ | 316 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio;RTW: return‐to‐work; QoL: quality of life. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1Median RTW rate in control groups. 2Three out of five trials with high risk of bias, downgraded one level. 3Wide CIs, downgraded one level. 4One study with high and one with low risk of bias, downgraded one level.

Summary of findings 2. Psycho‐educational care versus Care as usual for return to work in cancer patients.

| Psycho‐educational care versus Care as usual for return to work in cancer patients | |||||

| Patient or population: Patients with cancer Settings: Hospital Intervention: Psycho‐educational care Comparison: Care as usual | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Care as usual | Psycho‐educationalcare | ||||

| Return to work (RTW) Follow‐up: 1.5 to 12 months | 491 per 10001 | 535 per 1000 (432 to 663) | RR 1.09 (0.88 to 1.35) | 260 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 |

| Quality of life (QoL) Various scales Follow‐up: 1.5 to 12 months | ‐ | The mean QoL in the intervention groups was 0.05 standard deviations higher (0.2 lower to 0.3 higher) | ‐ | 260 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,4 |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; RTW: return‐to‐work; QoL: quality of life. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1Average of control groups' RTW rates. 2One study with high and one with low risk of bias, downgraded one level. 3Wide CIs overlapping with 1, downgraded one level. 4Wide CI including 0 and small effect size, downgraded one level.

Summary of findings 3. Physical exercise versus Care as usual for RTW in cancer.

| Physical exercise versus Care as usual for return to work in cancer | |||||

| Patient or population: Patients with cancer Settings: Community Intervention: Physical exercise Comparison: Care as usual | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Care as usual | Physical exercise | ||||

| RTW | 357 per 10001 | 429 per 1000 (114 to 1000) | RR 1.2 (0.32 to 4.54) | 28 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 |

| QoL Various scales Follow‐up: 12 months | ‐ | The mean QoL in the intervention groups was 0.37 standard deviations lower (0.99 lower to 0.25 higher) | ‐ | 41 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; RTW: return‐to‐work; QoL: quality of life. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1RTW rate in the control group. 2Wide CIs, only one included study, downgraded with two levels.

Summary of findings 4. Medical function conserving treatment versus Medical more radical treatment for cancer.

| Medical function conserving treatment versus Medical more radical treatment for cancer | |||||

| Patient or population: Patients with cancer Settings: Hospital Intervention: Medical function conserving treatment Comparison: Medical more radical treatment | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Medical more radical treatment | Medical function conserving treatment | ||||

| RTW Follow‐up: median 18 months | 850 per 10001 | 884 per 1000 (816 to 926) | RR 1.04 (0.96 to 1.09) | 1097 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 |

| QoL Various instruments Follow‐up: mean 9 months | ‐ | The mean QoL in the intervention groups was 0.10 standard deviations higher (0.04 lower to 0.23 higher) | ‐ | 1028 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; RTW: return‐to‐work; QoL: quality of life. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1 Median RTW rate in control groups of this comparison. 2 I² statistic = 51%, downgraded one level. 3 CIs overlap with one, downgraded one level.

The 15 included studies evaluated the effects of four types of interventions in cancer patients: psycho‐educational interventions, physical interventions, medical interventions and combinations of psycho‐educational, vocational and/or physical interventions.

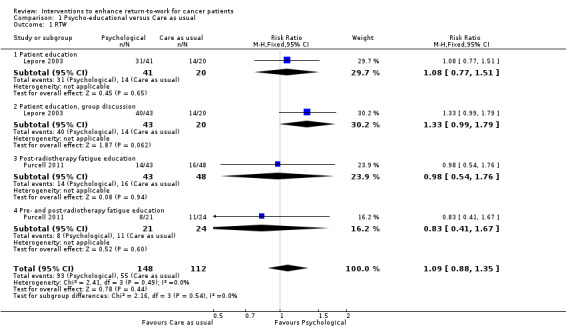

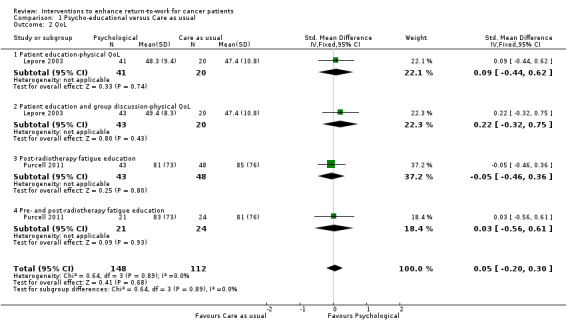

Psycho‐educational interventions

The studies assessing psycho‐educational interventions included a total of 260 patients with 148 patients in intervention groups and 112 in control groups. Two arms of one RCT reported in the same article (Lepore 2003) compared the effect of a psycho‐educational intervention or a psycho‐educational intervention combined with group discussion to care as usual. Similarly, two arms of another RCT compared the effects of either post‐ or pre‐and post radiotherapy fatigue education to care as usual (Purcell 2011). The combined results of these four evaluations from two RCTs indicated that there is low quality evidence of no considerable difference in the effect of psycho‐educational interventions compared to care as usual on RTW (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.35, n=260 patients; Table 2; Analysis 1.1.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psycho‐educational versus Care as usual, Outcome 1 RTW.

The results for the secondary outcome QoL of both studies (Lepore 2003; Purcell 2011) showed that there is low quality evidence of no difference in the effect of psycho‐educational interventions compared to care as usual (SMD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.2 to 0.3, n=260 patients; Table 2; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psycho‐educational versus Care as usual, Outcome 2 QoL.

Vocational interventions

We did not find any studies that assessed the effectiveness of vocational interventions.

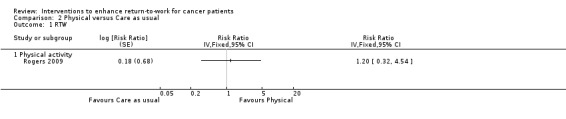

Physical interventions

Rogers 2009 reported an RCT in which breast cancer patients were offered a physical training programme. Results showed that there is low quality evidence that the physical training programme (N = 14) was not more effective than care as usual (N = 14) in improving RTW (RR = 1.20, 95% CI 0.32 to 4.54, n = 28 patients) or QoL (SMD = ‐0.37, 95% CI ‐0.99 to 0.25; n = 28 patients Table 3; Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Physical versus Care as usual, Outcome 1 RTW.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Physical versus Care as usual, Outcome 2 QoL.

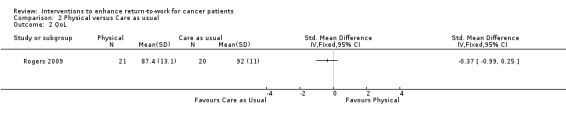

Medical interventions

Seven RCTs conducted with 1097 patients assessed the effects of a medical intervention on RTW (Ackerstaff 2009; Emmanouilidis 2009; Friedrichs 2010; Hillman 1998; Johnsson 2007; Kornblith 2009; Lee 1992). In all studies a less radical or function‐conserving medical intervention was compared with a more radical treatment, with the hypothesis that a function‐conserving medical treatment would improve RTW in cancer patients.

When we pooled the results of the seven individual studies in meta‐analysis we found low quality evidence that function conserving approaches yielded similar RTW rates as more radical treatments (calculated RR = 1.04, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.09 (median P0 of six dichotomous studies was 0.85), n = 1097 patients; Table 4; Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Medical function conserving versus Medical more radical, Outcome 1 RTW.

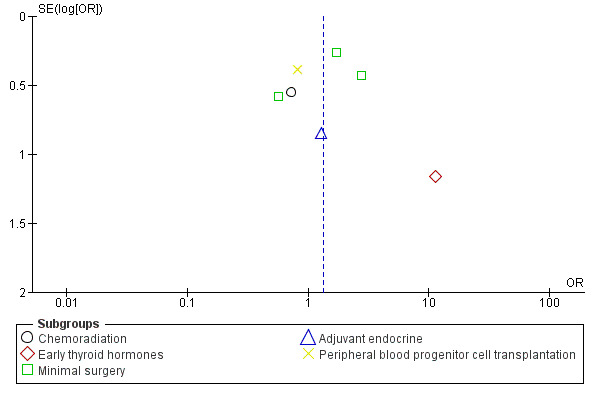

We assessed possible publication bias associated with the eight included RCT studies assessing the effect of a less radical medical treatment on RTW. The funnel plot (Figure 4) shows that there might be publication bias and that small studies reported non‐significant results.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 4 Medical function conserving versus Medical more radical‐RCTs, outcome: 4.1 RTW.

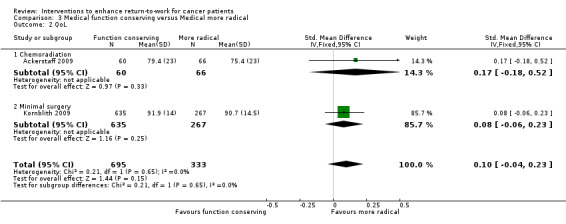

We also found two studies showing moderate quality evidence of no differences in the effect of function conserving medical interventions compared to more radical treatment on QoL outcomes (SMD = 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.23, n = 1028 patients; Table 4; Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Medical function conserving versus Medical more radical, Outcome 2 QoL.

Multidisciplinary interventions

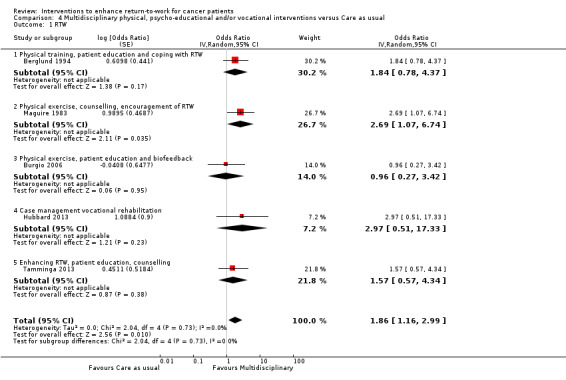

Five RCTs conducted with 450 patients assessed the effect of multidisciplinary interventions on RTW (Berglund 1994; Burgio 2006; Hubbard 2013; Maguire 1983; Tamminga 2013). Meta‐analysis produced moderate quality evidence that multidisciplinary interventions in which vocational counselling, patient education, patient counselling, biofeedback‐assisted behavioral training and/or physical exercises were combined led to higher RTW rates than care as usual (calculated RR = 1.11, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.16 (median P0 of four dichotomous studies was 0.79), n = 450 patients; Table 1; Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Multidisciplinary physical, psycho‐educational and/or vocational interventions versus Care as usual, Outcome 1 RTW.

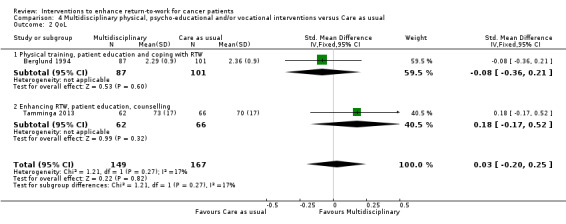

We also found two studies yielding low quality evidence of no differences in the effect of multidisciplinary interventions compared to care as usual on QoL outcomes (SMD = 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.20 to 0.25;, n = 316 patients Table 1; Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Multidisciplinary physical, psycho‐educational and/or vocational interventions versus Care as usual, Outcome 2 QoL.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Fifteen studies met the inclusion criteria of this Cochrane Review with a total of 1835 included participants. There was moderate quality evidence from two RCTs with multiple study arms that psycho‐educational interventions do not improve RTW (Lepore 2003; Purcell 2011). We did not find any studies that had assessed the effectiveness of vocational interventions. One trial compared physical training with care as usual and produced low quality evidence of no significant differences on RTW (Rogers 2009).

Seven RCTs yielded low quality evidence of no differences between function conserving versus more radical medical interventions on RTW outcomes (Ackerstaff 2009; Emmanouilidis 2009; Friedrichs 2010; Hillman 1998; Kornblith 2009; Lee 1992; Johnsson 2007). There was moderate quality evidence from five RCTs that multidisciplinary interventions that combine vocational counselling, patient education, patient counselling, biofeedback‐assisted behavioral training and/or physical exercises, produced a higher RTW rate than care as usual (Berglund 1994; Burgio 2006; Hubbard 2013; Maguire 1983; Tamminga 2013).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The included studies were conducted over a 40‐year time span. While one study was conducted in the 1970s and reported in the 1980s (Maguire 1983), we could not find any studies that were performed in the 1980s and only three studies that were conducted in the 1990s (Berglund 1994; Hillman 1998; Lee 1992). Thereby 11 included studies were performed after the year 2000 (Ackerstaff 2009; Burgio 2006; Emmanouilidis 2009; Friedrichs 2010; Hubbard 2013; Johnsson 2007; Kornblith 2009; Lepore 2003; Purcell 2011; Rogers 2009; Tamminga 2013). In these 40 years, medical treatment for cancer has changed enormously. For this reason, older medical studies (Hillman 1998; Lee 1992) may describe medical treatments that are not used anymore. Also the way in which psycho‐educational and multidisciplinary interventions are performed today differs considerably from what is described in the older included studies. Nowadays, interventions are more evidence‐based, more cognitive behavioural therapy‐oriented, briefer, more targeted and more effective than 20 to 30 years ago.

This Cochrane review considers patients from the USA and Europe. Social security systems and labour markets differ widely between countries and thus the effects of cancer survivorship on employment vary. However, in all included studies the effect of the interventions were compared in the same country and with an RCT study design and therefore the influence of a social security system was equal within studies. However, when generalising the results from one country to another, the potential effect of a particular country's social security system should still be considered. For the generalisation of the results of this review to countries outside Europe or the USA, cultural differences regarding employment and cancer disclosure should be taken into account.

Patients with breast cancer were the most studied diagnosis group (Berglund 1994; Hubbard 2013; Johnsson 2007; Lee 1992; Maguire 1983; Rogers 2009; Tamminga 2013) while other studies were aimed at patients with prostate cancer (Burgio 2006; Lepore 2003), thyroid cancer (Emmanouilidis 2009), gynaecological cancer (Kornblith 2009), head and neck cancer (Ackerstaff 2009), laryngeal cancer (Hillman 1998), mixed cancer diagnosis patients (Purcell 2011) and leukaemia patients (Friedrichs 2010). Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer diagnosis within the working population followed by blood and lymph cancers, prostate cancer, thyroid cancer and colorectal cancer (Short 2005). We did not find any studies that were aimed at patients with colorectal cancer (despite being common in cancer survivors of working age) nor aimed at less prevalent cancer diagnoses including brain cancer, bone cancer and other gastro‐intestinal cancers. We think that the mechanisms of the psycho‐educational, physical training and multidisciplinary RTW interventions are similar regardless of cancer diagnosis and thus patients with colorectal or other types of cancer will experience the same benefits from any of these interventions aimed at improving RTW. However, long‐term and late effects of specific treatments for specific cancers, such as solid versus non‐solid tumours, may differ and play a role in the RTW process. Ultimately, we do not know this because of the lack of evidence. The mechanism behind the effect on RTW of medical interventions should be interpreted with caution, because many of the interventions of the included studies were specific for certain types of cancer and there were inconsistent results. With regard to multidisciplinary interventions we found that multidisciplinary interventions in which vocational counselling, patient education, patient counselling, biofeedback‐assisted behavioral training and/or physical exercises were combined, were effective in improving RTW. These studies were conducted in patients with breast cancer (Berglund 1994; Hubbard 2013; Maguire 1983; Tamminga 2013) or prostate cancer (Burgio 2006) so it is not proven that patients with any other diagnoses will benefit from multidisciplinary interventions.

Although most multidisciplinary interventions did have a vocational component, we did not find any studies assessing vocational interventions focusing on employment issues. This is remarkable because one would expect interventions aimed at RTW to consist of work‐related components, such as work adjustments or involvement of the supervisor. Earlier research in young cancer survivors concluded that vocational rehabilitation interventions, such as vocational training, job search assistance, job placement services, on‐the job support and maintenance services, were all associated with increased odds for employment (Strauser 2010). This latter study was, however, aimed at unemployed cancer patients and the results might therefore not be easily generalised to employed cancer patients. Since our findings showed multidisciplinary interventions containing vocational counselling or coping with employment issues to be effective, more specific or more targeted vocational interventions should be developed and evaluated.

Quality of the evidence

Eleven of the 15 included studies did not report having performed ITT analyses. Moreover, the included studies did not, in most cases, implement blinding of providers, patients or outcome assessors or the blinding was unclear. It can be argued that blinding is not feasible in this type of study and that lack of blinding should not be considered a weakness, but the absence of blinding can be associated with bias even though blinding is not feasible. However, blinding of the outcome assessors and blinding of the patients to the hypothesis of the study are possible. The possibility for bias should therefore be taken into account. Unfortunately it was not discussed in most of the reports. We judged most included studies to have an unclear risk of bias due to sequence generation and allocation concealment, which may indicate further selection bias.

In this Cochrane review we analysed a total of 15 RCTs involving a considerable number of cancer patients (1835 participants). However, the number of patients analysed in the individual studies was generally low, with nine studies providing less than 50 patients in each group thus limiting the power of the studies. In addition, we assessed altogether four different types of interventions, each of which contained several subtypes of interventions. As a result the subtypes of interventions only described one to seven studies. Therefore, it was not possible to perform subgroup analyses according to diagnosis or study risk of bias.

For multidisciplinary interventions compared to care as usual, we included five studies with 450 patients, and concluded that there is moderate quality evidence that multidisciplinary interventions improve RTW more than care as usual RTW. However, for most other comparisons and outcomes, we downgraded the quality of the evidence due to few available studies, risk of bias, indirect results and imprecise effect estimates. GRADE assessments are partly based on subjective judgements and are not definite. Nevertheless GRADE does provide a transparent and consistent classification of the quality of evidence for relevant comparisons and outcomes.

One methodological consideration is the lack of information on baseline characteristics for the patients analysed in this review. In ten of 15 included studies the trial authors analysed data on RTW only for the patients who provided these data, i.e. the employed cancer patients in the study (Ackerstaff 2009; Burgio 2006; Emmanouilidis 2009; Friedrichs 2010; Hillman 1998; Kornblith 2009; Lee 1992; Lepore 2003; Maguire 1983; Rogers 2009). However, the authors reported baseline characteristics only for the total group of cancer patients in these studies including the retired patients and homemakers. Therefore we could not extract and report the baseline characteristics of the employed cancer patients that we included in our analyses. As these baseline characteristics have not been reported we could not check if both groups within the studies had equal distributions of age, sex, and education which could have influenced the effects of the intervention on RTW. However, because allstudies were randomised we assume that the distributions of age, sex and education in both groups of employed patients in each study were similar.

Potential biases in the review process

We sought to conduct a comprehensive and transparent review. We performed the entire process of study search, study selection, data extraction and management, and two review authors independently assessed risk of bias of included studies and we discussed all results until we reached consensus.

The reader can see from the 'Risk of bias' tables attached to the Characteristics of included studies tables that we scored some domains as 'unclear'. This implies that the primary publications did not supply enough details to assess this point. Ideally the number of domains assessed as 'unclear' should be reduced by obtaining supplementary information from the trial authors. For the sake of simplicity we chose to complete our 'Risk of bias' assessment based solely on the information printed in the primary papers.

We searched for eligible studies in ten electronic databases using 130 keywords or combinations of keywords whilst imposing no restrictions on language or publication date. We supplemented our systematic search process with checking the reference lists of included studies and selected reviews. We documented in duplicate and discussed all reasons for exclusion and inclusion of all 4742 potentially relevant studies. Two review authors independently extracted data and performed 'Risk of bias' assessment using an eight‐page form with each included study. We combined the contents of these forms in one consensus form, and a third review author gave advice in case of uncertainties. In case of any missing data or doubt on the correctness of data, we contacted the original trial authors. All six contacted trial authors replied and provided the requested data. Therefore, we think we have done our best to minimise the risk of bias due to the review process. Even though our search strategy was comprehensive and not restricted by language, there is always the risk that relevant citations may have been lost in the review process.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

In this Cochrane review we conclude that multidisciplinary physical, psycho‐educational and/or vocational interventions enhance RTW for cancer patients. Another Cochrane review has assessed the effectiveness of vocational rehabilitation programmes compared to care as usual on RTW of people with multiple sclerosis (MS) (Khan 2009). Results of the studies included in Khan 2009 showed that there was inconclusive evidence to support vocational rehabilitation for people with MS because one study aimed at job retention did not find any positive effect while the other study geared towards RTW reported a significant positive effect. This is in line with this review, because the effective studies in this review, two of which contain a vocational rehabilitation component, were also aimed at RTW and not at work retention. Another recent Cochrane review on patients with depression also found that multidisciplinary interventions combing a work‐directed intervention to a clinical intervention reduced the number of days on sick leave compared to a clinical intervention alone (Nieuwenhuijsen 2014). This is similar to the results of our review in which the multidisciplinary interventions were conducted within a hospital setting.

A systematic review including meta‐analysis on the efficacy of multidisciplinary interventions on RTW for people on sick leave due to low‐back pain indicated that multidisciplinary interventions, including behaviour‐oriented physiotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, behavioural medicine, light mobilisation, rehabilitation problem‐solving therapy, and behavioural graded activity or personal information, more effectively improve RTW than the alternatives (Norlund 2009). This result is also in agreement with our meta‐analysis which showed that multidisciplinary interventions are more effective than alternative programmes in improving RTW in cancer patients.

The studies we found in our literature search were all person‐directed interventions aimed at the patients. We did not find any work‐directed vocational interventions that were aimed at the workplace and included workplace adjustments, such as modified work hours, modified work tasks, or modified workplaces or improved communication with or between managers, colleagues and health professionals. An earlier systematic review on workplace‐based RTW interventions found strong evidence that work disability duration is significantly reduced by work accommodation offers and contact between healthcare provider and workplace (Franche 2005). The same review also found moderate evidence that work disability duration is reduced by interventions that include early contact with affected workers by their workplaces, ergonomic work site visits and presence of a RTW coordinator (Franche 2005). Although we found that multidisciplinary interventions enhance RTW for cancer patients, this effect might be increased by adding work‐directed vocational components to the interventions.

In this Cochrane review we found low quality evidence that psychosocial interventions are as effective as care as usual in enhancing RTW in cancer patients. The evidence being of low quality is caused by heterogeneity in the RCTs from which the effect was assessed. An earlier meta‐analysis found that cognitive behaviour training (CBT) has a positive effect on QoL, depression and anxiety in adult cancer survivors but that patient education (PE) does not (Osborn 2006). Results from our review show that interventions with patient education do have a positive effect in RTW of cancer patients, especially when they are part of a multidisciplinary intervention.

This review is an update of De Boer 2011. Compared to the earlier version of the review, we have now included four new studies (Friedrichs 2010; Hubbard 2013; Purcell 2011; Tamminga 2013). Furthermore, we have excluded non‐randomised studies in this update because it became clear that randomised studies are feasible and have been conducted. This resulted in the exclusion of three non‐randomised studies (Borget 2007; Capone 1980; Gordon 1980). In this update we have entered each intervention as a separate evaluation when an article reported more than one intervention (multiple study arms) and compared each intervention against a control group. In the earlier version of this review, we entered these evaluations (study arms) as different studies (De Boer 2011). The inclusion of the four new studies, exclusion of the three non‐randomised studies and reorganisation of the study arms into different evaluations rather than different studies did not change the conclusions of this review update compared to the first version of this review (De Boer 2011).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is moderate quality evidence that multidisciplinary interventions combining physical training, psycho‐educational and/or vocational elements improve the RTW of cancer patients. The most apparent setting for this intervention would be the hospital because all multidisciplinary providers are located there and it is the main focal point for the patients. Interventions conducted in a hospital setting are feasible for recently diagnosed cancer patients who are engaged in curative treatment and who are expected to have sufficient recovery to RTW. Other possible settings for RTW interventions for cancer patients would be multidisciplinary rehabilitation outpatient services in community or reintegration teams at large workplaces or multinational corporations. Furthermore, we need to provide effective guidelines to employers needing to deal with a cancer patient returning to work. Thus, it is possible to find ways to improve RTW for people who survive cancer.

There is low quality evidence that psycho‐educational, physical interventions and function‐conserving medical interventions yield similar RTW rates compared to care as usual.

Implications for research.

Multidisciplinary interventions enhance RTW for cancer patients. Most research so far has been conducted in breast cancer patients and prostate cancer patients. Research should additionally focus on patients with other prevalent diagnoses of cancer in the working population, such as colorectal cancer and blood or lymph cancers. Other important patient characteristics, such as age, education and ethnicity, should also be measured. Future research on enhancing RTW in cancer patients should involve multidisciplinary interventions with a physical, psycho‐educational and vocational component. The vocational component should not be just patient‐oriented but should also be directed at the work environment (including work adjustments and supervisors). With regard to psycho‐educational interventions it is unclear whether patient education or patient counselling is most effective. Both interventions should be compared against each other and care as usual.

We did not find any studies assessing vocational interventions aimed at enhancing RTW in cancer patients for this review although one would expect the largest impact on RTW from this kind of intervention. Future research should focus on vocational interventions that include any type of intervention focused on employment. Vocational interventions might be person‐directed, that is, aimed at the patient to encourage RTW, meaning vocational rehabilitation or occupational rehabilitation, or they might be work‐directed, that is, aimed at the workplace by means of workplace adjustments such as modified work hours, modified work tasks, or modified workplaces and improved communication with or between managers, colleagues and health professionals.

So far, not all studies comparing the effect of an intervention on RTW with care as usual or an alternative intervention have been conducted using a RCT design. Consequently there is uncertainty about effectiveness and we need more high‐quality RCTs. Therefore, all studies evaluating the effect of an intervention on RTW should employ a RCT design although this might be sometimes difficult in daily practice. These RCTs should perform ITT analysis. In some cases, a cluster‐RCT design might have to be chosen in which the providers of the intervention or the settings are randomised and not the patients. In addition, the studies described in this review were all relatively small and thus we need RCTs with a much greater number of recruited patients.