Abstract

Background

Many people with low back pain (LBP) become frequent users of healthcare services in their attempt to find treatments that minimise the severity of their symptoms. Back School consists of a therapeutic programme given to groups of people that includes both education and exercise. However, the content of Back School has changed over time and appears to vary widely today. This review is an update of a Cochrane review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effectiveness of Back School. We split the Cochrane review into two reviews, one focusing on acute and subacute LBP, and one on chronic LBP.

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review was to determine the effect of Back School on pain and disability for adults with chronic non‐specific LBP; we included adverse events as a secondary outcome. In trials that solely recruited workers, we also examined the effect on work status.

Search methods

We searched for trials in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, two other databases and two trials registers to 15 November 2016. We also searched the reference lists of eligible papers and consulted experts in the field of LBP management to identify any potentially relevant studies we may have missed. We placed no limitations on language or date of publication.

Selection criteria

We included only RCTs and quasi‐RCTs evaluating pain, disability, and/or work status as outcomes. The primary outcomes for this update were pain and disability, and the secondary outcomes were work status and adverse events.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently performed the 'Risk of bias' assessment of the included studies using the 'Risk of bias' assessment tool recommended by The Cochrane Collaboration. We summarised the results for the short‐, intermediate‐, and long‐term follow‐ups. We evaluated the overall quality of evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

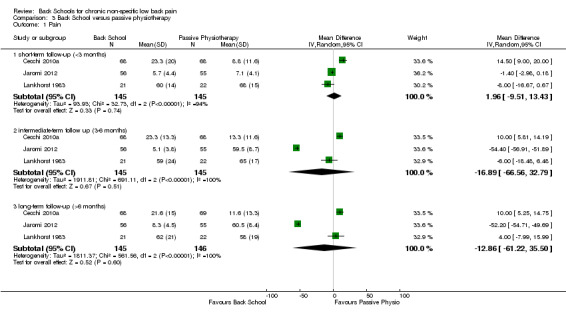

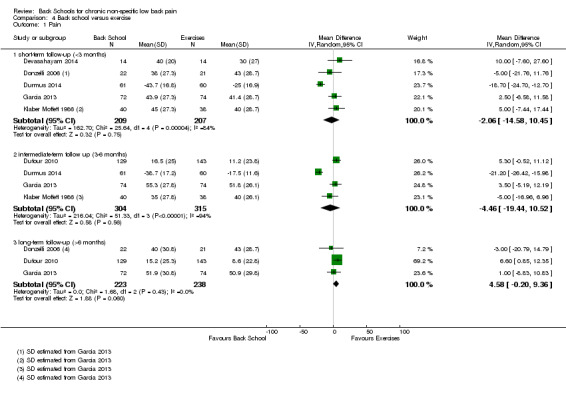

For the outcome pain, at short‐term follow‐up, we found very low‐quality evidence that Back School is more effective than no treatment (mean difference (MD) ‐6.10, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐10.18 to ‐2.01). However, we found very low‐quality evidence that there is no significant difference between Back School and no treatment at intermediate‐term (MD ‐4.34, 95% CI –14.37 to 5.68) or long‐term follow‐up (MD ‐12.16, 95% CI ‐29.14 to 4.83). There was very low‐quality evidence that Back School reduces pain at short‐term follow‐up compared to medical care (MD ‐10.16, 95% CI –19.11 to ‐1.22). Very low‐quality evidence showed there to be no significant difference between Back School and medical care at intermediate‐term (MD ‐9.65, 95% CI ‐22.46 to 3.15) or long‐term follow‐up (MD ‐5.71, 95% CI –20.27 to 8.84). We found very low‐quality evidence that Back School is no more effective than passive physiotherapy at short‐term (MD 1.96, 95% CI –9.51 to 13.43), intermediate‐term (MD ‐16.89, 95% CI ‐66.56 to 32.79), or long‐term follow‐up (MD ‐12.86, 95% CI –61.22 to 35.50). There was very low‐quality evidence that Back School is no better than exercise at short‐ term follow‐up (MD ‐2.06, 95% CI –14.58 to 10.45). There was low‐quality evidence that Back School is no better than exercise at intermediate‐term (MD ‐4.46, 95% CI –19.44 to 10.52) and long‐term follow‐up (MD 4.58, 95% CI –0.20 to 9.36).

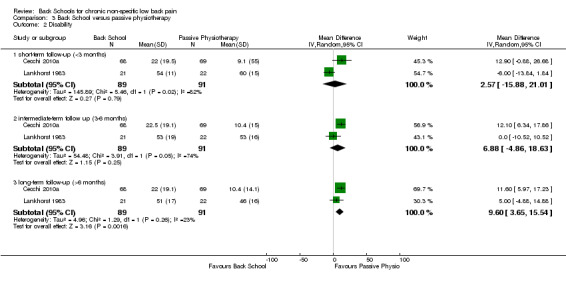

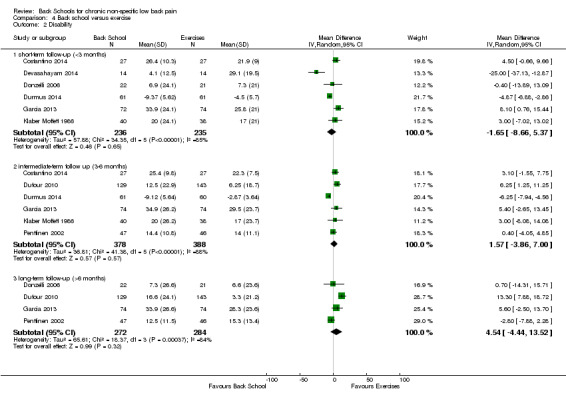

For the outcome disability, we found very low‐quality evidence that Back School is no more effective than no treatment at intermediate‐term (MD –5.92, 95% CI –12.08 to 0.23) and long‐term follow‐up (MD ‐7.36, 95% CI ‐22.05 to 7.34); medical care at short‐term (MD –1.19, 95% CI –7.02 to 4.64) and long‐term follow‐up (MD –0.40, 95% CI –7.33 to 6.53); passive physiotherapy at short‐term (MD 2.57, 95% CI –15.88 to 21.01) and intermediate‐term follow‐up (MD 6.88, 95% CI ‐4.86 to 18.63); and exercise at short‐term (MD ‐1.65, 95% CI –8.66 to 5.37), intermediate‐term (MD 1.57, 95% CI –3.86 to 7.00), and long‐term follow‐up (MD 4.54, 95% CI ‐4.44 to 13.52). We found very low‐quality evidence of a small difference between Back School and no treatment at short‐term follow‐up (MD –3.38, 95% CI –6.70 to –0.05) and medical care at intermediate‐term follow‐up (MD –6.34, 95% CI –10.89 to –1.79). Still, at long‐term follow‐up there was very low‐quality evidence that passive physiotherapy is better than Back School (MD 9.60, 95% CI 3.65 to 15.54).

Few studies measured adverse effects. The results were reported as means without standard deviations or group size was not reported. Due to this lack of information, we were unable to statistically pool the adverse events data. Work status was not reported.

Authors' conclusions

Due to the low‐ to very low‐quality of the evidence for all treatment comparisons, outcomes, and follow‐up periods investigated, it is uncertain if Back School is effective for chronic low back pain. Although the quality of the evidence was mostly very low, the results showed no difference or a trivial effect in favour of Back School. There are myriad potential variants on the Back School approach regarding the employment of different exercises and educational methods. While current evidence does not warrant their use, future variants on Back School may have different effects and will need to be studied in future RCTs and reviews.

Plain language summary

Back School for the treatment of chronic low back pain

Background

Many people with low back pain (LBP) seeking treatments that minimise the severity of their symptoms become frequent users of healthcare services. Back School consists of a therapeutic programme given to groups of people that includes both education and exercise. Since its introduction in 1969, the Swedish Back School has frequently been used in the treatment of LBP. However, the content of Back School has changed over time and appears to vary widely today.

Review question

We reviewed the evidence on the effects of Back School on pain and disability in adults with LBP with no specific cause lasting more than 12 weeks compared to no treatment, medical care, physiotherapist‐applied treatment, or exercise. We included adverse events as a secondary outcome. In trials that only recruited workers, we also examined the effect on work status.

Study characteristics

In this update we searched for trials, both published and unpublished, to 15 November 2016. We included 30 trials with 4105 participants comparing Back School to no treatment, medical care, passive physiotherapy (physiotherapist‐applied treatment), or exercise therapy. All studies included a similar population of people with chronic non‐specific LBP.

Key results

Regardless of the comparison used (as well as the outcomes investigated), the results of the meta‐analysis showed no difference or a trivial effect in favour of Back School. Due to a lack of information on adverse effects and work status, we were unable to statistically pool the data.

Quality of evidence

Due to the low‐ to very low‐quality evidence for all treatment comparisons, outcomes, and follow‐up periods investigated, it is uncertain if Back School is effective for chronic low back pain.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Back School compared with no treatment for low back pain.

| Back School compared with no treatment for low back pain | |||||

|

Patient or population: people with low back pain Intervention: Back School Comparison: no treatment | |||||

| Outcomes | lIIustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk* | ||||

| No treatment | Back School | ||||

|

Pain: short‐term follow‐up (< 3 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse pain) |

The mean pain at short‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 31.8 to 68 points. | The mean pain (short term) in the intervention groups was 6.10 lower (10.18 lower to 2.01 lower). | MD ‐6.10 (‐10.18 to ‐2.01) | 647 participants (6 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 |

|

Pain: intermediate‐term follow‐up (3 to 6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse pain) |

The mean pain at intermediate‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 26 to 65 points. | The mean pain (intermediate term) in the intervention groups was 4.34 lower (14.37 lower to 5.68 higher). | MD ‐4.34 (‐14.37 to 5.68) | 257 participants (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4 |

|

Pain: long‐term follow‐up (> 6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse pain) |

The mean pain at long‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 38 to 58 points. | The mean pain (long term) in the intervention groups was 12.16 lower (29.14 lower to 4.83 higher). | MD ‐12.16 (‐29.14 to 4.38) | 244 participants (3 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4 |

|

Disability: short‐term follow‐up (< 3 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse disability) |

The mean disability at short‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 29.3 to 60 points. | The mean disability (short term) in the intervention groups was 3.83 lower (6.70 lower to 0.05 lower). | MD ‐3.38 (‐6.70 to ‐0.05) | 426 participants (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 |

|

Disability: intermediate‐term follow‐up (3 to 6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse disability) |

The mean disability at intermediate‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 39 to 53 points. | The mean disability (intermediate term) in the intervention groups was 5.92 lower (12.80 lower to 0.23 higher). | MD ‐5.92 (‐12.08 to 0.23) | 181 participants (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4 |

|

Disability: long‐term follow‐up (> 6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse disability) |

The mean disability long‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 48 to 51 points. | The mean disability (long term) in the intervention groups was 7.36 lower (22.05 lower to 7.34 higher). | MD ‐7.36 (‐22.05 to 7.34) | 124 participants (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4 |

| Adverse events Not reported | |||||

| Work status Not reported | |||||

| The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐quality evidence: There are consistent findings among at least 75% of randomised controlled trials with low risk of bias; consistent, direct, and precise data; and no known or suspected publication biases. Further research is unlikely to change either the estimate or our confidence in the results. Moderate‐quality evidence: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low‐quality evidence: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low‐quality evidence: We are very uncertain about the results. No evidence: We identified no randomised controlled trials that addressed this outcome. | |||||

1Downgraded one level due to imprecision (fewer than 400 participants in total). 2Downgraded one level due to risk of bias (> 25% of the participants were from studies with a high risk of bias). 3Downgraded one level due to clear inconsistency of results. 4Downgraded one level due to publication bias.

Summary of findings 2. Back School compared with medical care for low back pain.

| Back School compared with medical care for low back pain | |||||

|

Patient or population: people with low back pain Intervention: Back School Comparison: medical care | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk* | ||||

| Medical care | Back School | ||||

|

Pain: short‐term follow‐up (< 3 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse pain) |

The mean pain at short‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 17 to 73 points. | The mean pain (short term) in the intervention groups was 10.16 lower (19.11 lower to 1.22 lower). | MD ‐10.16 (‐19.11 to ‐1.22) | 249 participants (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4 |

|

Pain: intermediate‐term follow‐up (3 to 6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse pain) |

The mean pain at intermediate‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 12 to 76 points. | The mean pain (intermediate term) in the intervention groups was 9.65 lower (22.46 lower to 3.15 higher). | MD ‐9.65 (‐22.46 to 3.15) | 545 participants (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 |

|

Pain: long‐term follow‐up (> 6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse pain) |

The mean pain at long‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 12 to 65 points. | The mean pain (long term) in the intervention groups was 5.71 lower (20.27 lower to 8.84 higher). | MD ‐5.71 (‐20.27 to 8.84) | 406 participants (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 |

|

Disability: short‐term follow‐up (< 3 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse disability) |

The mean disability at short‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 24.8 to 41.2 points. | The mean disability at short‐term follow‐up in the intervention groups was 1.19 lower (7.02 lower to 4.64 higher). | MD ‐1.19 (‐7.02 to 4.64) | 130 participants (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4 |

|

Disability: intermediate‐term follow‐up (3 to 6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse disability) |

The mean disability at intermediate‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 25.8 to 43.3 points. | The mean disability at intermediate‐term follow‐up in the intervention groups was 6.34 lower (10.89 lower to 1.79 lower). | MD ‐6.34 (‐10.89 to ‐1.79) | 331 participants (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4 |

|

Disability: long‐term follow‐up (> 6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse disability) |

The mean disability at long‐term follow‐up was 32.9 points. | The mean disability at long‐term follow‐up in the intervention groups was 0.40 lower (7.33 lower to 6.53 higher). | MD ‐0.40 (‐7.33 to 6.53) | 201 participants (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4 |

| Adverse events Two workers in the Back School group (n=98) reported a strong increase in low back pain (Heymans 2006). | |||||

| Work status Not reported | |||||

| The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐quality evidence: There are consistent findings among at least 75% of randomised controlled trials with low risk of bias; consistent, direct, and precise data; and no known or suspected publication biases. Further research is unlikely to change either the estimate or our confidence in the results. Moderate‐quality evidence: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low‐quality evidence: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low‐quality evidence: We are very uncertain about the results. No evidence: We identified no randomised controlled trials that addressed this outcome. | |||||

1Downgraded one level due to imprecision (fewer than 400 participants in total). 2Downgraded one level due to risk of bias (> 25% of the participants were from studies with a high risk of bias). 3Downgraded one level due to clear inconsistency of results. 4Downgraded one level due to publication bias.

Summary of findings 3. Back School compared with passive physiotherapy for low back pain.

| Back School compared with passive physiotherapy for low back pain | |||||

|

Patient or population: people with low back pain. Intervention: Back School Comparison: passive physiotherapy | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk* | ||||

| Passive physiotherapy | Back School | ||||

| pain: short‐term follow‐up (< 3 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse pain) | The mean pain at short‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 7.1 to 88 points. | The mean pain (short‐ term) in the intervention groups was 1.96 higher (9.51 lower to 13.43 higher). | MD 1.96 (‐9.51 to 13.43) | 290 participants (3 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4 |

|

pain ‐ intermediate‐term follow up (3‐6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse pain) |

The mean pain at intermediate‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 13.3 to 65 points. | The mean pain (intermediate‐term) in the intervention groups was 16.89 lower (66.56 lower to 32.79 higher). | MD ‐16.89 (‐66.56 to 32.79) | 290 participants (3 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4 |

|

pain ‐ long‐term follow‐up (>6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse pain) |

The mean pain at long‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 11.6 to 60.5 points. | The mean pain (long‐ term) in the intervention groups was 12.86 lower (61.22 lower to 35.50 higher). | MD ‐12.86 (‐61.22 to 35.50) | 291 participants (3 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4 |

|

Disability ‐ short‐term follow‐up (<3 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse disability) |

The mean disability at short‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 9.1 to 60 points. | The mean disability at short‐term follow‐up in the intervention groups was 2.57 higher (15.88 lower to 21.01 higher). | MD 2.57 (‐15.88 to 21.01) | 180 participants (2 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4 |

|

Disability ‐ intermediate‐term follow up (3‐6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse disability) |

The mean disability at intermediate‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 10.4 to 53 points. | The mean disability at short‐term follow‐up in the intervention groups was 6.88 higher (‐4.86 lower to 18.63 higher). | MD 6.88 (‐4.86 to 18.63). | 180 participants (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4 |

|

Disability ‐ long‐term follow‐up (>6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse disability) |

The mean disability at long‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 10.4 to 46 points. | The mean disability at long‐term follow‐up in the intervention groups was 9.60 higher (3.65 higher to 15.54 higher). | MD 9.60 (3.65 to 15.54) | 180 participants (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4 |

| Adverse events Not reported | |||||

| Work status Not reported | |||||

| The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐quality evidence: There are consistent findings among at least 75% of randomised controlled trials with low risk of bias; consistent, direct, and precise data; and no known or suspected publication biases. Further research is unlikely to change either the estimate or our confidence in the results. Moderate‐quality evidence: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low‐quality evidence: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low‐quality evidence: We are very uncertain about the results. No evidence: We identified no randomised controlled trials that addressed this outcome. | |||||

1 Downgraded one level due to imprecision (fewer than 400 participants, in total). 2 Downgraded one level due to risk of bias (> 25% of the participants were from studies with a high risk of bias). 3 Downgraded one level due to clear inconsistency of results. 4 Downgraded one level due to publication bias.

Summary of findings 4. Back School compared with exercise for low back pain.

| Back School compared with exercise for low back pain | |||||

|

Patient or population: people with low back pain Intervention: Back School Comparison: exercise | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk* | ||||

| Exercise | Back School | ||||

|

Pain: short‐term follow‐up (< 3 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse pain) |

The mean pain at short‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 25 to 40 points. | The mean pain (short term) in the intervention groups was 2.06 lower (14.58 lower to 10.45 higher). | MD ‐2.06 (‐14.58 to 10.45) | 416 participants (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 |

|

Pain: intermediate‐term follow‐up (3 to 6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse pain) |

The mean pain at intermediate‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 11.2 to 40 points. | The mean pain (intermediate term) in the intervention groups was 4.46 lower (19.44 lower to 10.52 higher). | MD ‐4.46 (‐19.44 to 10.52) | 619 participants (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 |

|

Pain: long‐term follow‐up (> 6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse pain) |

The mean pain at long‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 8.6 to 50.9 points. | The mean pain (long term) in the intervention groups was 4.58 higher (0.20 lower to 9.36 higher). | MD 4.58 (‐0.20 to 9.36) | 461 participants (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 |

|

Disability: short‐term follow‐up (< 3 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse disability) |

The mean disability at short‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 4.5 to 29.1 points. | The mean disability at short‐term follow‐up in the intervention groups was 1.65 lower (8.66 lower to 5.37 higher). | MD ‐1.65 (‐8.66 to 5.37) | 471 participants (6 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 |

|

Disability: intermediate‐term follow‐up (3 to 6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse disability) |

The mean disability at intermediate‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 2.87 to 29.5 points. | The mean disability at intermediate‐term follow‐up in the intervention groups was 1.57 higher (3.86 lower to 7.00 higher). | MD 1.57 (‐3.86 to 7.00) | 766 participants (6 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 |

|

Disability: long‐term follow‐up (> 6 months) Multiple scales: scale from 0 to 100 (worse disability |

The mean disability at long‐term follow‐up ranged across control groups from 3.3 to 28.3 points. | The mean disability at long‐term follow‐up in the intervention groups was 4.54 higher (4.44 lower to 13.52 higher). | MD 4.54 (‐4.44 to 13.52) | 556 participants (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 |

| Adverse events One participant in the Back School group reported a temporary exacerbation of pain (Garcia 2013) and 5 patients in exercise group experienced worsening of leg pain (Dufour 2010) | |||||

| Work status Not reported | |||||

| The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐quality evidence: There are consistent findings among at least 75% of randomised controlled trials with low risk of bias; consistent, direct, and precise data; and no known or suspected publication biases. Further research is unlikely to change either the estimate or our confidence in the results. Moderate‐quality evidence: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low‐quality evidence: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low‐quality evidence: We are very uncertain about the results. No evidence: We identified no randomised controlled trials that addressed this outcome. | |||||

1Downgraded one level due to imprecision (fewer than 400 participants in total). 2Downgraded one level due to risk of bias (> 25% of the participants were from studies with a high risk of bias). 3Downgraded one level due to clear inconsistency of results. 4Downgraded one level due to publication bias.

Background

See glossary of terms in Appendix 1.

Description of the condition

Low back pain (LBP) is a major problem worldwide, and the associated disability is responsible for a significant personal burden (van Tulder 2006). The Global Burden of Disease Study suggests that LBP is one of the 10 leading causes of disease burden globally (Murray 2013; Vos 2010). Many people with LBP become frequent users of healthcare services in their attempt to find treatments that minimise the severity of their symptoms.

Exercise therapy is commonly advised for people with LBP, and it is recommended in clinical practice guidelines as an effective treatment for chronic LBP (European Guidelines 2006). A Cochrane systematic review on this topic also concluded that exercise therapy is effective in decreasing pain and improving function in adults with chronic LBP (Hayden 2005). Education has been recommended in clinical practice guidelines for chronic LBP (European Guidelines 2006). Supervised exercise therapy associated with an educational component has been considered to be one of the most effective interventions in reducing pain and disability in people with chronic LBP (Airaksinen 2006; van Tulder 2006).

Back School is one treatment that provides both exercise and education for the treatment of people with chronic LBP. The original Swedish Back School was introduced by Zachrisson‐Forssell in 1969. It was designed to reduce pain and prevent recurrences of LBP episodes (Forssell 1980; Forssell 1981). Back School was a therapeutic programme including information on the anatomy of the back, biomechanics, optimal posture, ergonomics, and back exercises. Since the introduction of the Swedish Back School, the content and length of the method have changed and appear to vary widely today.

This review is an update of a previously conducted Cochrane review of the effectiveness of Back School for chronic non‐specific LBP. The previous Cochrane review was published in 2004 and concluded that Back School seemed to be more effective than other treatments, placebo, or waiting‐list controls for improving pain, functional status, and return to work (Heymans 2004). Since the completion of this review, new trials about Back School have been published (Andrade 2008; Cecchi 2010a; Costantino 2014; Devasahayam 2014; Donzelli 2006; Dufour 2010; Durmus 2014; Garcia 2013; Heymans 2006; Jaromi 2012; Meng 2009; Morone 2011; Morone 2012; Nentwig 1990; Paolucci 2012a; Paolucci 2012b; Ribeiro 2008; Sahin 2011; Tavafian 2007). Given this substantial amount of new data, and developments in systematic review methods, a revision of the 2004 Cochrane review was needed to provide clinicians and patients up‐to‐date information about the effects of this intervention. Our aim was therefore to perform an update on this topic in order to provide accurate and robust information on the effectiveness of the Back School approach for chronic non‐specific LBP, as compared to no treatment, medical care, passive physiotherapy, or exercise therapy.

Description of the intervention

The original Swedish Back School was introduced by Zachrisson‐Forssell in 1969. It was meant to reduce pain and prevent recurrences of episodes of LBP (Forssell 1980; Forssell 1981). Back School was a therapeutic programme including information on the anatomy of the back, biomechanics, optimal posture, ergonomics, and back exercises and was given to groups of patients. The aim was to reduce back pain and teach people to care for their own backs and back pain in an active way should back pain recur.

How the intervention might work

Back School is a combination of exercises and education, where lessons are given to groups of patients, supervised by a physical therapist or medical specialist. According to the European guidelines (Airaksinen 2006), the combination of exercise programmes and education seems to be the most promising approach for the management of chronic non‐specific LBP. Theoretical information could help patients understand their condition and learn how to modify their behaviour with regard to LBP. People with chronic non‐specific LBP often have maladaptive thoughts, feelings, and beliefs, which have an important role in their experience of LBP (Parsons 2007). Exercise therapy is probably the most commonly used intervention for the treatment of people with chronic non‐specific LBP. It is reported in the literature as effective in decreasing pain and improving function (Hayden 2005). Treatment that combines both interventions has the potential to improve pain and disability in people with chronic non‐specific LBP.

Why it is important to do this review

This review is an update of a previously conducted Cochrane review of randomised controlled trials on the effectiveness of Back School (Heymans 2004). We split this review into two reviews, one focusing on acute and subacute LBP, and one on chronic LBP. This review evaluated the effectiveness of Back School for chronic non‐specific LBP. In previous reviews it was not possible to statistically pool the data because of the heterogeneity of the included studies. Conclusions were generated on the basis of the methodological quality scores of the studies, assessed using a generally accepted criteria list, in combination with a best‐evidence synthesis (van Tulder 2003). Since 2011, a number of new RCTs have been published evaluating the effectiveness of Back School. Method guidelines for Cochrane reviews have also been published by The Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2011) and in the field of back pain (Furlan 2015). These were also implemented in the current updated review.

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review was to determine the effect of Back School on pain and disability for adults with chronic non‐specific LBP; we included adverse events as a secondary outcome. In trials that solely recruited workers, we also examined the effect on work status.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs.

Types of participants

We included studies evaluating people with chronic (more than 12 weeks' duration) non‐specific LBP, aged 18 to 70 years. Low back pain is defined as pain localised below the scapulae and above the cleft of the buttocks; non‐specific indicates that no specific cause was detected, such as infection, neoplasm, metastasis, osteoporosis, fracture, or inflammatory arthritis. We did not include trials enrolling participants with pregnancy‐related LBP.

Types of interventions

We included studies in which one of the treatments consisted of a Back School‐type of intervention. We included trials that used a clear contrast for the Back School intervention, such as usual care, waiting list, or other interventions (e.g. exercise therapy or manipulation). Additional interventions were allowed. However, if the Back School was part of a larger multidisciplinary treatment programme, we only included the study if a contrast existed for the Back School. For example, a study that compared Back School plus a fitness programme against a fitness programme was included, but a study that compared Back School plus fitness programme against a waiting list was not. Trials that studied the effectiveness of Back School in workers or non‐workers without low back pain at study onset were not included because they concerned primary prevention of LBP.

Technique (index dose):

We classified the intensity of the technique as follows.

Intensive: when the length of the session was greater than or equal to 20 hours (intervention time)

Non‐intensive: when the length of the session was less than 20 hours (intervention time)

Not specified

Types of outcome measures

We included trials that reported outcomes for short‐term (less than three months), intermediate‐term (three to six months), and long‐term (more than six months) follow‐up.

Primary outcomes

Pain (e.g. measured by visual analogue scale or numerical rating scale)

Disability (e.g. measured by Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) or Roland‐Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ))

Secondary outcomes

Work status in trials that solely recruited workers (e.g. days of sick leave)

Adverse events (reported by the physiotherapists on standardised forms)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We used the search methods developed by the Cochrane Back and Neck Review Group and Chapter 6 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Furlan 2015; Higgins 2011). The strategies were developed and updated by the Information Specialist of the Back and Neck Review Group.

We searched for trials in the following databases to 15 November 2016:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, which also includes the Back and Neck Group Trials Register) (the Cochrane Library, Issue 10, 2016);

MEDLINE (OvidSP; Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R); 1946 to 15 November 2016);

Embase (Ovid SP, 1980 to 2016 Week 46);

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCO, 1981 to 15 November 2016);

PsycINFO (Ovid SP, 2002 to November Week 1 2016);

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/);

PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

We added CINAHL and PsycINFO to the search in 2007 and the clinical trials registries in 2011; we searched these from inception to current. We added MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations in 2015. We searched PubMed in August 2015 to capture any studies published within the previous year using the strategy recommended by Duffy 2014. In 2016, we searched MEDLINE (Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R)), which allows multiple sets of MEDLINE databases to be searched at one time.

The search strategies can be found in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We screened reference lists of relevant reviews and included studies, and consulted experts in the field of LBP management to identify any potentially relevant studies we may have missed.

Data collection and analysis

For each of the steps, two review authors (PP and NP) independently selected new studies, assessed risk of bias, and extracted data (using a standardised form). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or by bringing in a third review author if disagreements persisted (CM).

Selection of studies

For this update, we first reassessed the included studies from the original review to ensure that they met our revised inclusion criteria. Following the same process as in the original review and previous update, two review authors (PP and NP) first screened the titles and abstracts of the new studies. The full texts of all potentially relevant studies were then retrieved for the final selection of eligible studies.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (PP and NP) independently extracted the data using standardised data extraction forms. We collected the following information:

participant characteristics (patient source or setting, study inclusion criteria, duration of LBP episode);

intervention characteristics (description and types of Back School, duration and number of treatment sessions, intervention delivery type, and co‐interventions); and

outcome data (pain intensity, disability, work status, adverse events);

When several time points fell within the same category, we used the time point closest to six weeks for the short term, four months for the intermediate term, and 12 months for the long term.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (PP and NP) independently assessed the risk of bias in included studies. We employed a consensus method to resolve disagreements, consulting a third review author (CM) if disagreement persisted. We used the Cochrane Back and Neck 'risk of bias' criteria (Table 5 and Table 6) (Furlan 2015).

1. Sources of risk of bias.

| Bias domain | Source of bias | Possible answers |

| Selection | (1) Was the method of randomization adequate? | Yes/no/unsure |

| Selection | (2) Was the treatment allocation concealed? | Yes/no/unsure |

| Performance | (3) Was the patient blinded to the intervention? | Yes/no/unsure |

| Performance | (4) Was the care provider blinded to the intervention? | Yes/no/unsure |

| Detection | (5) Was the outcome assessor blinded to the intervention? | Yes/no/unsure |

| Attrition | (6) Was the drop‐out rate described and acceptable? | Yes/no/unsure |

| Attrition | (7) Were all randomized participants analyzed in the group to which they were allocated? | Yes/no/unsure |

| Reporting | (8) Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? | Yes/no/unsure |

| Selection | (9) Were the groups similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators? | Yes/no/unsure |

| Performance | (10) Were co‐interventions avoided or similar? | Yes/no/unsure |

| Performance | (11) Was the compliance acceptable in all groups? | Yes/no/unsure |

| Detection | (12) Was the timing of the outcome assessment similar in all groups? | Yes/no/unsure |

| Other | (13) Are other sources of potential bias unlikely? | Yes/no/unsure |

2. Criteria for a judgment of ‘‘yes’’ for the sources of risk of bias.

| 1 | A random (unpredictable) assignment sequence. Examples of adequate methods are coin toss (for studies with 2 groups), rolling a dice (for studies with 2 or more groups), drawing of balls of different colours, drawing of ballots with the study group labels from a dark bag, computer‐generated random sequence, preordered sealed envelopes, sequentially‐ordered vials, telephone call to a central office, and preordered list of treatment assignments. Examples of inadequate methods are: alternation, birth date, social insurance/security number, date in which they are invited to participate in the study, and hospital registration number. |

| 2 | Assignment generated by an independent person not responsible for determining the eligibility of the patients. This person has no information about the persons included in the trial and has no influence on the assignment sequence or on the decision about eligibility of the patient. |

| 3 | Index and control groups are indistinguishable for the patients or if the success of blinding was tested among the patients and it was successful. |

| 4 | Index and control groups are indistinguishable for the care providers or if the success of blinding was tested among the care providers and it was successful. |

| 5 | Adequacy of blinding should be assessed for each primary outcome separately. This item should be scored ‘‘yes’’ if the success of blinding was tested among the outcome assessors and it was successful or:

|

| 6 | The number of participants who were included in the study but did not complete the observation period or were not included in the analysis must be described and reasons given. If the percentage of withdrawals and drop‐outs does not exceed 20% for short‐term follow‐up and 30% for long‐term follow‐up and does not lead to substantial bias a ‘‘yes’’ is scored. (N.B. these percentages are arbitrary, not supported by literature). |

| 7 | All randomized patients are reported/analyzed in the group they were allocated to by randomization for the most important moments of effect measurement (minus missing values) irrespective of noncompliance and co‐interventions. |

| 8 | All the results from all prespecified outcomes have been adequately reported in the published report of the trial. This information is either obtained by comparing the protocol and the report, or in the absence of the protocol, assessing that the published report includes enough information to make this judgment. |

| 9 | Groups have to be similar at baseline regarding demographic factors, duration and severity of complaints, percentage of patients with neurological symptoms, and value of main outcome measure(s). |

| 10 | If there were no co‐interventions or they were similar between the index and control groups. |

| 11 | The reviewer determines if the compliance with the interventions is acceptable, based on the reported intensity, duration, number and frequency of sessions for both the index intervention and control intervention(s). For example, physiotherapy treatment is usually administered for several sessions; therefore it is necessary to assess how many sessions each patient attended. For single‐session interventions (e.g., surgery), this item is irrelevant. |

| 12 | Timing of outcome assessment should be identical for all intervention groups and for all primary outcome measures. |

| 13 | Other types of biases. For example:

|

Measures of treatment effect

The primary outcome measures were continuous (pain and disability); the secondary outcome measures (work status and adverse events) were mainly dichotomous. For all continuous outcomes, we quantified the treatment effects with the mean difference (MD). To accommodate the different scales used for these outcomes, we converted outcomes to a common 0‐to‐100 scale. We also expected to encounter dichotomous outcomes such as return to work; in such cases we calculated risk ratios (RR) of experiencing the positive outcome. We used effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals (CI) as a measure of treatment effect.

Unit of analysis issues

If trials were sufficiently homogenous, we conducted a meta‐analysis for these follow‐up time points: short (within three months after randomisation), intermediate (at least three months but within 12 months after randomisation), and long term (12 months or longer after randomisation). When multiple time points fell within the same category, we used the one that was closer to the end of treatment, 6 months or 12 months.

Dealing with missing data

We emailed the authors of each study requesting any necessary data that were not comprehensively reported in the manuscript. We also estimated data from graphs in cases where this information was not presented in tables or text. If the standard deviation was not reported, we calculated it from confidence intervals or standard errors (if available). If no measure of variability was presented anywhere in the text, we estimated the standard deviation from the most similar trial in the review, taking the risk of bias of individual studies into consideration.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We based the assessment of heterogeneity on visual inspections of the forest plots (e.g. overlapping confidence intervals) and more formally by the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

To avoid potential language bias, we applied no language restriction to the searches.

Data synthesis

Regardless of whether there were sufficient data available to use quantitative analyses to summarise the data, we assessed the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome. We used the GRADE approach, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), and adapted in the updated Cochrane Back and Neck Review Group method guidelines (Furlan 2015). The GRADE approach to evidence synthesis can be found in Appendix 3.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We stratified the analyses based upon the duration of follow‐up reported for each outcome (i.e. short term, intermediate term, and long term).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned sensitivity analyses to see if the overall results on effectiveness between comparison groups changed when in the studies of high risk of bias, defined as fulfilling five or more criteria out of the 13.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

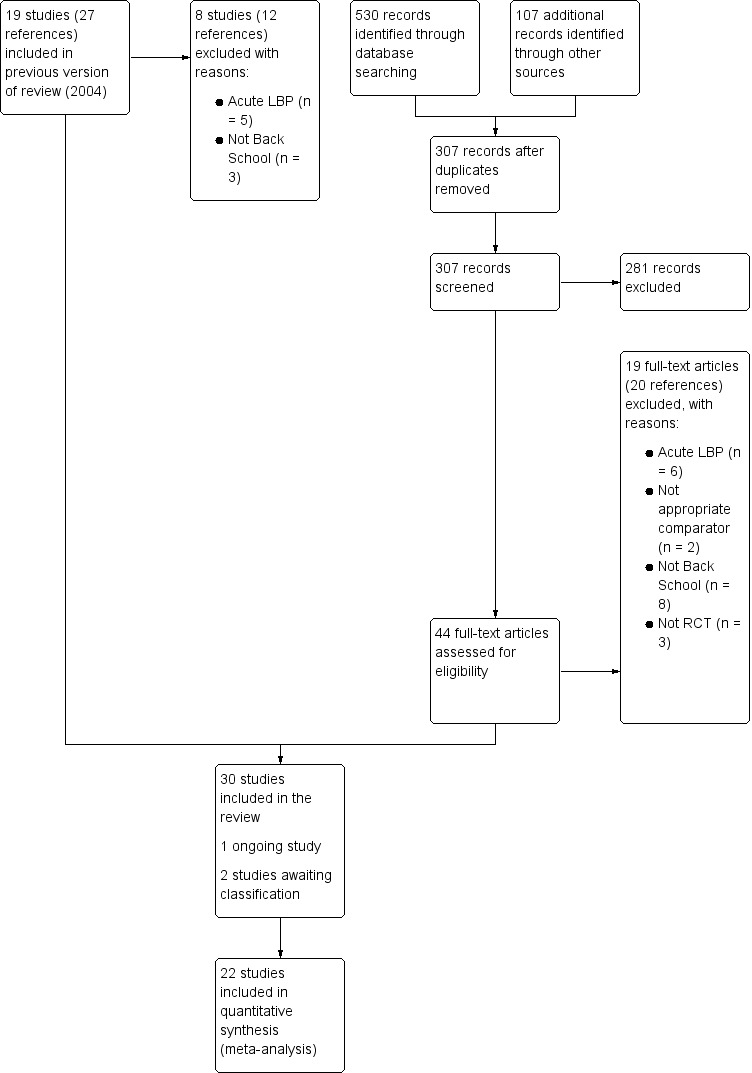

The search retrieved 307 trials after duplicates were removed (Figure 1). After the selection and discussion step, based on title, keyword, abstract, and full text screening, both review authors agreed that 19 studies (20 references) met the inclusion criteria (Andrade 2008; Cecchi 2010a; Costantino 2014; Devasahayam 2014; Donzelli 2006; Dufour 2010; Durmus 2014; Garcia 2013; Heymans 2006; Jaromi 2012; Meng 2009; Morone 2011; Morone 2012; Nentwig 1990; Paolucci 2012a; Paolucci 2012b; Ribeiro 2008; Sahin 2011; Tavafian 2007). We found one study that was a protocol for an included study (Garcia 2013). We included 11 studies (15 references) from the previous review (Berwick 1989; Dalichau 1999; Donchin 1990; Hurri 1989; Keijsers 1989; Keijsers 1990; Klaber Moffett 1986; Lankhorst 1983; Lønn 1999; Penttinen 2002; Postacchini 1988). We included a total of 30 studies (35 references) in this update. An additional search for ongoing or registered trials in ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO ICTRP retrieved one record (IRCT201010184251N2). We consulted experts in the field of LBP research but did not identify any new studies. The most recent search performed on 15 November 2016 retrieved two studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Garcia 2016; Paolucci 2016), and we added them to the 'awaiting classification' section to be incorporated in the next review update.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 30 studies with a total of 4105 participants. The study sample sizes ranged from 37 to 360 participants (mean = 128). Ten studies were not included in the meta‐analysis because they lacked necessary data (Dalichau 1999; Donchin 1990; Dufour 2010; Hurri 1989; Keijsers 1990; Morone 2011; Morone 2012; Nentwig 1990; Paolucci 2012a; Postacchini 1988).

Design

Of the 30 studies included in this review, only one study was a quasi‐RCT (Donzelli 2006).

Types of studies

We identified the following comparisons in this review.

Ten trials compared Back School with no treatment (Andrade 2008; Dalichau 1999; Donchin 1990; Hurri 1989; Keijsers 1989; Keijsers 1990; Lønn 1999; Meng 2009; Nentwig 1990; Postacchini 1988).

Seven trials compared Back School with medical care (Berwick 1989; Morone 2011; Morone 2012; Paolucci 2012a; Paolucci 2012b; Ribeiro 2008; Tavafian 2007).

Four trials compared Back School with passive physiotherapy (Cecchi 2010a; Jaromi 2012; Lankhorst 1983; Postacchini 1988).

Eleven trials compared Back School with exercises (Costantino 2014; Devasahayam 2014; Donchin 1990; Donzelli 2006; Dufour 2010; Durmus 2014; Garcia 2013; Heymans 2006; Klaber Moffett 1986; Penttinen 2002; Sahin 2011).

Two trials had three treatment arms (Donchin 1990; Postacchini 1988), and we included both treatment contrasts.

Study population

Eleven studies included a homogeneous population of LBP patients without radiation (Andrade 2008; Berwick 1989; Cecchi 2010a; Costantino 2014; Devasahayam 2014; Donzelli 2006; Durmus 2014; Garcia 2013; Lankhorst 1983; Meng 2009; Sahin 2011), while 17 studies did not specify if participants had radiating symptoms or not, and five studies included a mixed population of patients with and without radiating symptoms (Dufour 2010; Heymans 2006; Jaromi 2012; Morone 2011; Tavafian 2007). Eight studies reported no data on the sex or age of the groups evaluated (Andrade 2008; Devasahayam 2014; Donzelli 2006; Keijsers 1990; Meng 2009; Nentwig 1990; Paolucci 2012a; Postacchini 1988); three studies included women only (Durmus 2014; Hurri 1989; Linton 1989); and one study included men only (Dalichau 1999). All trials included participants with chronic symptoms (LBP persisting for 12 weeks or more) exclusively.

Primary outcomes

Pain intensity

Seventeen studies measured pain intensity with a visual analogue scale or a numerical rating scale from 0 to 10 (Andrade 2008; Devasahayam 2014; Donzelli 2006; Dufour 2010; Durmus 2014; Garcia 2013; Heymans 2006; Jaromi 2012; Keijsers 1989; Klaber Moffett 1986; Meng 2009; Morone 2011; Morone 2012; Paolucci 2012a; Postacchini 1988; Ribeiro 2008; Sahin 2011). The other instruments were: pain rating (Cecchi 2010a; Dalichau 1999), pain index (Hurri 1989; Keijsers 1990; Morone 2011), McGill Pain Scale, pain severity subscale (Paolucci 2012b), subscale of 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36) (Tavafian 2007), and mean pain (Lankhorst 1983). One study created their own instrument (Nentwig 1990). All scales were converted to a 0‐to‐100 scale.

Disability

Nineteen studies measured disability (Andrade 2008; Cecchi 2010a; Costantino 2014; Devasahayam 2014; Donchin 1990; Donzelli 2006; Dufour 2010; Durmus 2014; Garcia 2013; Heymans 2006; Hurri 1989; Klaber Moffett 1986; Lønn 1999; Meng 2009; Morone 2011; Morone 2012; Penttinen 2002; Ribeiro 2008; Sahin 2011). Seven studies measured disability with the Roland‐Morris Disability Questionnaire (Andrade 2008; Cecchi 2010a; Costantino 2014; Devasahayam 2014; Dufour 2010; Garcia 2013; Heymans 2006). Nine studies measured disability using the Oswestry Disability Index (Donchin 1990; Donzelli 2006; Durmus 2014; Hurri 1989; Klaber Moffett 1986; Morone 2011; Morone 2012; Penttinen 2002; Sahin 2011); one study used the Low Back Disability Scale (Lønn 1999); and one study used the Hannover Functional Ability Questionnaire (Meng 2009). All scales were converted to a 0‐to‐100 scale.

Secondary outcomes

Return to work

Three studies measured return to work (Dalichau 1999; Heymans 2006; Keijsers 1990). Due to insufficient information, we were unable to statistically pool the data.

Adverse events

Three studies measured adverse effects (Dufour 2010; Garcia 2013; Heymans 2006). All studies either reported means without standard deviations or did not report group size; we were therefore unable to statistically pool the data.

Excluded studies

We excluded 19 studies (20 references) in the full –text assessment for eligibility. Of the 19 excluded full‐text articles, six studies did not consider Back School as the intervention (Demoulin 2006; Härkäpää 1989; Härkäpää 1990; Linton 1989; Tavafian 2008; Yang 2010). In one study the results were for a single group (Sadeghi‐Abdollahi 2012). In another study each group was assessed once (the control group at the beginning of the programme, the Back School group at the end) (Morrison 1988). In three studies, the Back School intervention consisted of education only, without exercises (Cecchi 2010b; Indahl 1998; Maul 2005; Mele 2006). In one study the Back School intervention was not a clear contrast for the control group (Meng 2011). In six studies, the average time of symptoms in the inclusion criteria was characterised as acute LBP (Bergquist 1977; Herzog 1991; Hsieh 2002; Indahl 1995; Leclaire 1996; Lindequist 1984).

Risk of bias in included studies

The results from the 'Risk of bias’ assessment for the individual studies are summarised in Figure 2. We considered 10% of the studies to have a low risk of bias. Due to the small number of studies with low risk of bias, it was not possible to run a sensitivity analysis as planned.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Eleven studies described an appropriate method of randomisation (Andrade 2008; Costantino 2014; Donchin 1990; Dufour 2010; Durmus 2014; Garcia 2013; Heymans 2006; Klaber Moffett 1986; Lønn 1999; Paolucci 2012a; Ribeiro 2008). Only seven studies were at low risk of bias for allocation concealment (Dufour 2010; Durmus 2014; Heymans 2006; Klaber Moffett 1986; Paolucci 2012a; Ribeiro 2008; Sahin 2011).

Blinding

Due to the nature of the intervention, none of the included studies blinded participants or care providers. Nine of the included studies blinded outcome assessment (Andrade 2008; Cecchi 2010a; Devasahayam 2014; Dufour 2010; Garcia 2013; Heymans 2006; Jaromi 2012; Ribeiro 2008; Sahin 2011).

Incomplete outcome data

Most of the included studies (86%) had a good rate of follow‐up, with less than 20% withdrawals and dropouts.

Selective reporting

One of the included studies had a published protocol (Garcia 2013). We scored all studies as at unclear risk of reporting bias, as we could not compare prespecified outcomes with reported ones.

Other potential sources of bias

We considered all studies as having a low risk of other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

See: Summary of main results, Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Effectiveness of Back School

Comparison 1: Back School versus no treatment

Ten trials compared Back School with no treatment for chronic LBP (Andrade 2008; Dalichau 1999; Donchin 1990; Hurri 1989; Keijsers 1989; Keijsers 1990; Lønn 1999; Meng 2009; Nentwig 1990; Postacchini 1988). Four trials provided insufficient information and were therefore not included in the analysis (Donchin 1990; Hurri 1989; Nentwig 1990; Postacchini 1988).

In the meta‐analysis for the outcome pain, based on six trials (Andrade 2008; Dalichau 1999; Keijsers 1989; Keijsers 1990; Lankhorst 1983; Meng 2009), there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to risk of bias, inconsistency, and publication bias) that Back School reduces pain compared with no treatment at short‐term follow‐up (MD ‐6.10, 95% CI –10.18 to ‐2.01; I2 = 19%). At intermediate‐term follow‐up, four trials provided very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision, risk of bias, and publication bias) that there was no substantial difference between Back School and no treatment (MD ‐4.34, 95% CI –14.37 to 5.68; I2 = 71%) (Andrade 2008; Keijsers 1990; Lankhorst 1983; Lønn 1999). Based on three trials (Dalichau 1999; Lankhorst 1983; Lønn 1999), there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision, risk of bias, inconsistency, and publication bias) that Back School was no better than no treatment at long‐term follow‐up (MD ‐12.16, 95% CI ‐29.14 to 4.83; I2 = 84%) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Back School versus no treatment, Outcome 1 Pain.

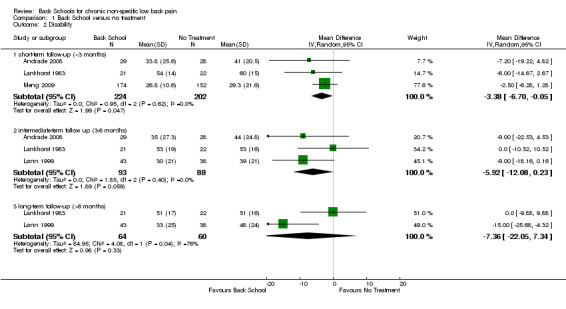

In the meta‐analysis for the outcome disability, based on three trials (Andrade 2008; Lankhorst 1983; Meng 2009), there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to risk of bias, inconsistency, and publication bias) at short‐term follow‐up that Back School was slightly better than no treatment (MD –3.38, 95% CI –6.70 to –0.05; I2 = 0%). At intermediate‐term follow‐up, based on three trials (Andrade 2008; Lankhorst 1983; Lønn 1999), there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision, risk of bias, and publication bias) that Back School was no better than no treatment (MD –5.92, 95% CI –12.08 to 0.23; I2 = 0%). At long‐term follow‐up, based on two trials (Lankhorst 1983; Lønn 1999), there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision, risk of bias, and publication bias) that there was no important difference between Back School and no treatment (MD ‐7.36, 95% CI ‐22.05 to 7.34; I2 = 76%) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Back School versus no treatment, Outcome 2 Disability.

None of the included studies reported adverse events or work status.

Comparison 2: Back School versus medical care

Five trials evaluated the effectiveness of Back School compared to medical care for chronic LBP (Berwick 1989; Heymans 2006; Morone 2011; Ribeiro 2008; Tavafian 2007).

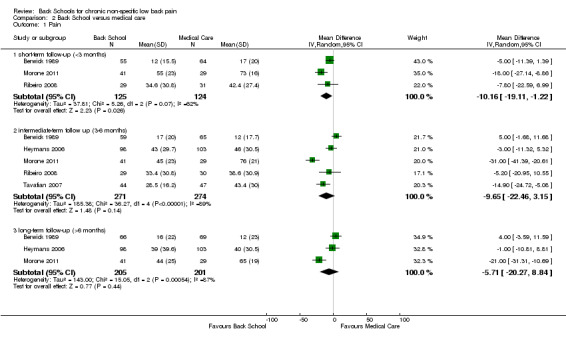

In the meta‐analysis for the outcome pain, based on three trials (Berwick 1989; Morone 2011; Ribeiro 2008), there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision, risk of bias, and publication bias) that Back School reduces pain intensity compared with medical care at short‐term follow‐up (MD ‐10.16, 95% CI –19.11 to ‐1.22; I2 = 62%). At intermediate‐term follow‐up, based on five trials (Berwick 1989; Heymans 2006; Morone 2011; Ribeiro 2008; Tavafian 2007), there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to risk of bias, inconsistency, and publication bias) that there was no important difference between Back School and medical care (MD ‐9.65, 95% CI ‐22.46 to 3.15; I2 = 89%). Based on three trials (Berwick 1989; Heymans 2006; Morone 2011), there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to risk of bias, inconsistency, and publication bias) that Back School was no better than medical care at long‐term follow‐up (MD ‐5.71, 95% CI –20.27 to 8.84; I2 = 87%) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Back School versus medical care, Outcome 1 Pain.

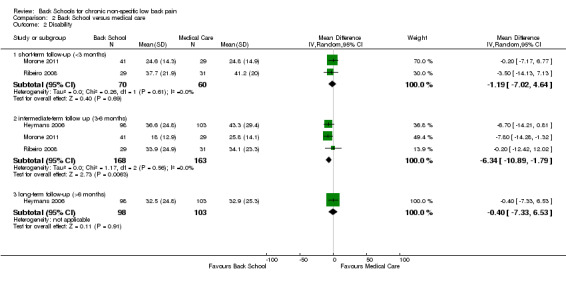

For the outcome disability, based on two trials (Morone 2011; Ribeiro 2008), there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision, risk of bias, and publication bias) that Back School was no better than medical care at short‐term follow‐up (MD –1.19, 95% CI –7.02 to 4.64; I2 = 0%). At intermediate‐term follow‐up, three trials provided very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision, risk of bias, and publication bias) that Back School was better than medical care (MD –6.34, 95% CI –10.89 to –1.79; I2 = 0%) (Heymans 2006; Morone 2011; Ribeiro 2008). At long‐term follow‐up, one trial, Heymans 2006, provided inconclusive evidence that Back School improves disability compared with medical care (MD –0.40, 95% CI –7.33 to 6.53; I2 = not applicable) (very low quality evidence; downgraded due to imprecision, risk of bias and publication bias) (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Back School versus medical care, Outcome 2 Disability.

Only one study (Heymans 2006) measured adverse effects and reported that two workers in the Back School group (n=98), reported a strong increase in low back pain. However, the result reported means without standard deviations or did not report group size; we were therefore unable to statistically pool the data. None of the included studies reported work status.

Comparison 3: Back School versus passive physiotherapy

Four trials evaluated the effectiveness of Back School compared to passive physiotherapy for chronic LBP (Cecchi 2010a; Jaromi 2012; Lankhorst 1983; Postacchini 1988). One trial did not report any usable information (Postacchini 1988).

In the meta‐analysis for the outcome pain, based on three trials (Cecchi 2010a; Jaromi 2012; Lankhorst 1983), there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision, risk of bias, inconsistency, and publication bias) that Back School is no better than passive physiotherapy at short‐term follow‐up (MD 1.96, 95% CI –9.51 to 13.43; I2 = 94%). Based on three trials (Cecchi 2010a; Jaromi 2012; Lankhorst 1983), it is uncertain that there is any difference between back school and passive physiotherapy at intermediate term (MD ‐16.89, 95% CI ‐66.56 to 32.79; I2 = 100%) and long‐term follow‐up (MD ‐12.86, 95% CI –61.22 to 35.50; I2 = 100%)(very low quality evidence; downgraded due to imprecision, risk of bias, inconsistency, and publication bias) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Back School versus passive physiotherapy, Outcome 1 Pain.

In the meta‐analysis for the outcome disability, based on two trials (Cecchi 2010a; Lankhorst 1983), there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision, risk of bias, inconsistency, and publication bias) that Back School was no better than passive physiotherapy (MD 2.57, 95% CI –15.88 to 21.01; I2 = 82%) at short‐term follow‐up. At intermediate‐term follow‐up, two trials provided very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision, risk of bias, and publication bias) that there was no important difference between Back School and passive physiotherapy (MD 6.88, 95% CI ‐4.86 to 18.63; I2 = 74%) (Cecchi 2010a; Lankhorst 1983). At long‐term follow‐up, two trials, Cecchi 2010a and Lankhorst 1983, provided very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision, risk of bias, and publication bias) that passive physiotherapy was better than Back School (MD 9.60, 95% CI 3.65 to 15.54; I2 = 23%) (Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Back School versus passive physiotherapy, Outcome 2 Disability.

None of the included studies reported adverse events or work status.

Comparison 4: Back School versus exercise

Eight trials evaluated the effectiveness of Back School compared to exercise for chronic LBP (Costantino 2014; Devasahayam 2014; Donzelli 2006; Dufour 2010; Durmus 2014; Garcia 2013; Klaber Moffett 1986; Penttinen 2002).

In the meta‐analysis for the outcome pain, based on five trials (Devasahayam 2014; Donzelli 2006; Durmus 2014; Garcia 2013; Klaber Moffett 1986), there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to risk of bias, inconsistency, and publication bias) that Back School is no better than exercise at short‐term follow‐up (MD ‐2.06, 95% CI –14.58 to 10.45; I2 = 84%). There was low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to inconsistency and publication bias) that there was no important difference between Back School and exercise at intermediate‐term follow‐up (MD ‐4.46, 95% CI –19.44 to 10.52; I2 = 94%) based on four trials (Dufour 2010; Durmus 2014; Garcia 2013; Klaber Moffett 1986). At long‐term follow‐up, three trials provided low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to inconsistency and publication bias) that exercise was no better than Back School in reducing pain (MD 4.58, 95% CI –0.20 to 9.36; I2 = 0%) (Analysis 4.1) (Donzelli 2006; Dufour 2010; Garcia 2013).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Back school versus exercise, Outcome 1 Pain.

In the meta‐analysis for the outcome disability, there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to risk of bias, inconsistency, and publication bias) that there was no important difference between Back School and exercise at short‐term follow‐up (MD ‐1.65, 95% CI –8.66 to 5.37; I2 = 85%) based on six trials (Costantino 2014; Devasahayam 2014; Donzelli 2006; Durmus 2014; Garcia 2013; Klaber Moffett 1986). At intermediate‐term follow‐up, six trials provided very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to risk of bias, inconsistency, and publication bias) that Back School was no better than exercise (MD 1.57, 95% CI –3.86 to 7.00; I2 = 88%) (Costantino 2014; Devasahayam 2014; Dufour 2010; Garcia 2013; Klaber Moffett 1986; Penttinen 2002). Based on four trials (Donzelli 2006; Dufour 2010; Garcia 2013; Penttinen 2002), there was very low‐quality evidence (downgraded due to risk of bias, inconsistency, and publication bias) that there was no significant difference between Back School and exercise at long‐term follow‐up (MD 4.54, 95% CI ‐4.44 to 13.52; I2 = 80%) (Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Back school versus exercise, Outcome 2 Disability.

Two studies (Dufour 2010; Garcia 2013) measured adverse effects. One participant in the Back School group reported a temporary exacerbation of pain (Garcia 2013) and 5 patients in exercise group experienced worsening of leg pain (Dufour 2010). However, the results reported means without standard deviations or did not report group size; we were therefore unable to statistically pool the data. None of the included studies reported work status.

Discussion

Summary of main results

It is uncertain if Back School is effective for chronic non‐specific LBP, as we only located very low‐ to low‐quality evidence. The pooled effect sizes were typically small and/or not statistically significant.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Based on the low number of available studies and limited comparison treatments, the overall evidence is incomplete and the comparative effectiveness of Back School versus other contemporary treatments for chronic LBP is unknown. The Back School interventions varied from intensive (36 sessions during 12 weeks in Dufour 2010) to non‐intensive (4 sessions during 4 weeks in Garcia 2013). This difference in treatment programmes could affect the generalisability of the evidence. Most included trials did not provide information about the care provider, hindering the generalisability of our findings to other settings.

Quality of the evidence

Based on the GRADE approach, the quality of the evidence varied from very low to low, the main problems being inconsistency, risk of bias, and publication bias. The most commonly identified methodological deficiencies were lack of blinding of participants and care providers (scored as high risk of bias in all 30 RCTs); lack of blinding of assessors (scored as high risk of bias or unclear in 18 RCTs); inappropriate method of randomisation (scored as high risk of bias or unclear in 18 RCTs); inadequate concealment of treatment allocation (scored as high risk of bias or unclear in 18 RCTs); and selective reporting (scored as high risk of bias or unclear in 23 RCTs). It is very difficult to blind this type of treatment, and because of the use of self reported outcomes (at least in terms of pain and disability), very difficult to blind the assessor.

Potential biases in the review process

In this systematic review, we aimed to perform a meta‐analysis for some comparisons to provide quantitative estimates of treatment effects. However, some of the trials did not report sufficient information (e.g. means, standard deviations, or group size), which prevented us from providing a quantitative summary of the data from these trials. Furthermore, a limited number of studies reported return‐to‐work outcomes and adverse effects. Due to this lack of information, we were unable to statistically pool the data and consequently performed a best‐evidence synthesis. Of particular note was the heterogeneity among studies for the content of Back School and type of control interventions. Due to a high statistical heterogeneity of some comparisons, we used a random‐effects model to perform the meta‐analysis. An additional limitation was that for most comparisons it was not possible to search for evidence of publication bias using funnel plots as too few studies were included.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

In general, the results of this review are reasonably consistent with the previous Cochrane review regarding pain and disability outcomes (Heymans 2004). In the current review, Back School was minimally more effective than no treatment for pain and disability outcomes at short term, but not at intermediate‐ or long‐term follow‐up. This result is consistent with that from the previous review, which found conflicting evidence on the effectiveness of Back School compared to waiting‐list controls or placebo interventions for all outcomes.

The previous review found moderate evidence that Back School is more effective than other treatments for the outcomes pain and functional status at short‐ and intermediate‐term follow‐ups, but not at long‐term follow‐up. In this review, we stratified ‘other treatments’ into medical care, passive physiotherapy, and exercise because we considered these treatments to be sufficiently different that they should be evaluated separately. For all of these control treatments, our results were inconsistent or we did not find any significant differences in effectiveness when compared to Back School for pain and disability outcomes for all time periods.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found only low‐ or very low‐quality evidence for all comparisons, outcomes, and follow‐up periods investigated. Regardless of the comparison treatment used (as well as the outcomes investigated), the results of the meta‐analysis showed no difference or a trivial effect in favour of Back School. There does not seem to be sufficient justification for using Back School in clinical practice.

Implications for research.

Given the scarcity and low quality of evidence in this area, a large, well‐designed randomised controlled trial is very likely to change our conclusions on the effectiveness of Back School for chronic non‐specific low back pain. However, Back School is not endorsed by guidelines. Further research into this area may not be necessary.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 November 2016 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | In this update, we identified 19 additional studies for a total of 30 included studies. The conclusions of this review are not in agreement with the previous Cochrane review (Heymans 2004). In the previous Cochrane review, the authors concluded that there was moderate evidence suggesting that Back Schools, in an occupational setting, reduced pain and improved function and return‐to‐work status, in the short and intermediate term, compared to exercises, manipulation, myofascial therapy, advice, placebo, or waiting‐list controls, for people with chronic and recurrent low back pain. In this update, we found low‐ to very low‐quality evidence for all treatment comparisons, outcomes, and follow‐up periods investigated. |

| 10 September 2015 | New search has been performed | Four authors joined the review team (P Parreira, N Poquet, C Maher, and C Lin), and one of the original authors is no longer involved (C Bombardier). We made the following methodological changes: We included quasi‐randomised controlled trials as well as randomised controlled trials. The primary outcomes were pain and disability. The secondary outcomes were work status and adverse events. Finally, we stratified ‘other treatments’ into medical care, passive physiotherapy, and exercise because we considered these treatments to be sufficiently different that they should be evaluated separately. |

Acknowledgements

Patricia Parreira is supported by CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior), Brazil. Chris Maher is supported by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Glossary of terms

Bias: a systematic error, or deviation from the truth, in results or inferences. Biases can operate in either direction: different biases can lead to underestimation or overestimation of the true intervention effect. Control of bias in randomised controlled trials is necessary to reduce the risk of making incorrect conclusions about treatment effects.

Biomechanics: the study of muscular activity.

Ergonomics: the arranging of things people use in a way that makes their use safe and less painful.

Medical care: pain medication, physician counselling.

Meta‐analysis: the statistical combination of results from two or more separate studies.

Metastasis: the spreading of cancer.

Neoplasm: tumour.

Osteoporosis: the thinning and weakening of bones which can lead to fractures.

Publication bias: the publication or non‐publication of research findings, depending on the nature and direction of the results.

Scapulae: shoulder blade.

Appendix 2. Search strategies

CENTRAL

Last searched 15 November 2016. The strategy was revised in 2011. Back pain was added to line 3 in 2015.

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Back Pain] explode all trees

#2 dorsalgia

#3 backache or back pain

#4 (lumbar near pain) or (coccyx) or (coccydynia) or (sciatica) or (spondylosis)

#5 MeSH descriptor: [Sciatica] explode all trees

#6 MeSH descriptor: [Spine] explode all trees

#7 MeSH descriptor: [Spinal Diseases] explode all trees

#8 (lumbago) or (discitis) or (disc near herniat*)

#9 spinal fusion

#10 facet near joint*

#11 MeSH descriptor: [Intervertebral Disc] explode all trees

#12 postlaminectomy

#13 arachnoiditis

#14 failed near back

#15 MeSH descriptor: [Cauda Equina] explode all trees

#16 lumbar near vertebra*

#17 spinal near stenosis

#18 slipped near (disc* or disk*)

#19 degenerat* near (disc* or disk*)

#20 stenosis near (spine or root or spinal)

#21 displace* near (disc* or disk*)

#22 prolap* near (disc* or disk*)

#23 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22)

#24 "back school"

#25 (#23 and #24)

#26 #25 in Trials

#27 #26 Publication Year from 2015 to 2016

January 2009 strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Back explode all trees

#2 MeSH descriptor Buttocks, this term only

#3 MeSH descriptor Leg, this term only

#4 MeSH descriptor Back Pain explode tree 1

#5 MeSH descriptor Back Injuries explode all trees

#6 MeSH descriptor Low Back Pain, this term only

#7 MeSH descriptor Sciatica, this term only

#8 (low next back next pain)

#9 (lbp)

#10 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9)

#11 (back school):ti,ab,kw

#12 (#10 AND #11), from 2007 to 2009

MEDLINE

Last searched 15 November 2016. Back pain was added to line 17 in 2015. Lines 5, 22, 25 and 26 were added in 2014.

1 randomized controlled trial.pt.

2 controlled clinical trial.pt.

3 comparative study.pt.

4 clinical trial.pt.

5 pragmatic clinical trial.pt.

6 randomized.ab.

7 placebo.ab,ti.

8 drug therapy.fs.

9 randomly.ab,ti.

10 trial.ab,ti.

11 groups.ab,ti.

12 or/1‐11

13 (animals not (humans and animals)).sh.

14 12 not 13

15 dorsalgia.ti,ab.

16 exp Back Pain/

17 (backache or back pain).ti,ab.

18 (lumbar adj pain).ti,ab.

19 coccyx.ti,ab.

20 coccydynia.ti,ab.

21 sciatica.ti,ab.

22 exp sciatic neuropathy/

23 spondylosis.ti,ab.

24 lumbago.ti,ab.

25 back disorder$.ti,ab.

26 exp Back Muscles/

27 or/15‐26

28 back school.mp.

29 14 and 27 and 28

30 limit 29 to yr=2015‐2016

31 limit 29 to ed=20150804‐20161115

32 30 or 31

The June 2011 search for MEDLINE used a different entry date filter to current strategy:

randomized controlled trial.pt.

controlled clinical trial.pt.

randomized.ab.

placebo.ab,ti.

drug therapy.fs.

randomly.ab,ti.

trial.ab,ti.

groups.ab,ti.

or/1‐8

(animals not (humans and animals)).sh.

9 not 10

dorsalgia.ti,ab.

exp Back Pain/

backache.ti,ab.

exp Low Back Pain/

(lumbar adj pain).ti,ab.

coccyx.ti,ab.

coccydynia.ti,ab.

sciatica.ti,ab.

sciatica/

spondylosis.ti,ab.

lumbago.ti,ab.

or/12‐22

back school.mp.

11 and 24 and 23

limit 25 to yr="2009 ‐ 2011"

2009$.ed.

2010$.ed.

2011$.ed.

27 or 28 or 29

25 and 30

26 or 31

The April 2007 strategy for MEDLINE used a different study design filter to current strategy

exp "Clinical Trial [Publication Type]"/

randomized.ab,ti.

placebo.ab,ti.

dt.fs.

randomly.ab,ti.

trial.ab,ti.

groups.ab,ti.

or/1‐7

Animals/

Humans/

9 not (9 and 10)

8 not 11

dorsalgia.ti,ab.

exp Back Pain/

backache.ti,ab.

(lumbar adj pain).ti,ab.

coccyx.ti,ab.

coccydynia.ti,ab.

sciatica.ti,ab.

sciatica/

spondylosis.ti,ab.

lumbago.ti,ab.

exp low back pain/

or/13‐23

back school.mp.

12 and 24 and 25

limit 26 to yr="2004 ‐ 2007"

EMBASE

Last searched 15 November 2016. In March 2014, line 31 was changed from 14 and 30 to 14 or 30, line 47 was added, and the animal study filter (lines 32 to 36) was revised from the June 2011 strategy

Clinical Article/

exp Clinical Study/

Clinical Trial/

Controlled Study/

Randomized Controlled Trial/

Major Clinical Study/

Double Blind Procedure/

Multicenter Study/

Single Blind Procedure/

Phase 3 Clinical Trial/

Phase 4 Clinical Trial/

crossover procedure/

placebo/

or/1‐13

allocat$.mp.

assign$.mp.

blind$.mp.

(clinic$ adj25 (study or trial)).mp.

compar$.mp.

control$.mp.

cross?over.mp.

factorial$.mp.

follow?up.mp.

placebo$.mp.

prospectiv$.mp.

random$.mp.

((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).mp.

trial.mp.

(versus or vs).mp.

or/15‐29

14 or 30

exp animals/ or exp invertebrate/ or animal experiment/ or animal model/ or animal tissue/ or animal cell/ or nonhuman/

human/ or normal human/ or human cell/

32 and 33

32 not 34

31 not 35

dorsalgia.mp.

back pain.mp.

exp BACKACHE/

(lumbar adj pain).mp.

coccyx.mp.

coccydynia.mp.

sciatica.mp.

ischialgia/

spondylosis.mp.

lumbago.mp.

back disorder$.ti,ab.

or/37‐47

back school.mp.

36 and 48 and 49

limit 50 to yr=2015‐2016

limit 50 to dd=20150804‐20161115

51 or 52

The June 2011 strategy used a different animal study and entry date filter:

Clinical Article/

exp Clinical Study/

Clinical Trial/

Controlled Study/

Randomized Controlled Trial/

Major Clinical Study/

Double Blind Procedure/

Multicenter Study/

Single Blind Procedure/

Phase 3 Clinical Trial/

Phase 4 Clinical Trial/

crossover procedure/

placebo/

or/1‐13

allocat$.mp.

assign$.mp.

blind$.mp.

(clinic$ adj25 (study or trial)).mp.

compar$.mp.

control$.mp.

cross?over.mp.

factorial$.mp.

follow?up.mp.

placebo$.mp.

prospectiv$.mp.

random$.mp.

((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).mp.

trial.mp.

(versus or vs).mp.

or/15‐29

14 and 30

human/

Nonhuman/

exp ANIMAL/