Abstract

Background

At birth, infants' lungs are fluid‐filled. For newborns to have a successful transition, this fluid must be replaced by air to enable effective breathing. Some infants are judged to have inadequate breathing at birth and are resuscitated with positive pressure ventilation (PPV). Giving prolonged (sustained) inflations at the start of PPV may help clear lung fluid and establish gas volume within the lungs.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of an initial sustained (> 1 second duration) lung inflation versus standard inflations (≤ 1 second) in newly born infants receiving resuscitation with intermittent PPV.

Search methods

We used the standard search strategy of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group to search the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 1), MEDLINE via PubMed (1966 to 17 February 2017), Embase (1980 to 17 February 2017), and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1982 to 17 February 2017). We also searched clinical trials databases, conference proceedings, and the reference lists of retrieved articles to identify randomised controlled trials and quasi‐randomised trials.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs comparing initial sustained lung inflation (SLI) versus standard inflations given to infants receiving resuscitation with PPV at birth.

Data collection and analysis

We assessed the methodological quality of included trials using Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC) criteria (assessing randomisation, blinding, loss to follow‐up, and handling of outcome data). We evaluated treatment effects using a fixed‐effect model with risk ratio (RR) for categorical data and mean, standard deviation (SD), and weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous data. We assessed the quality of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Main results

Eight trials enrolling 941 infants met our inclusion criteria. Investigators in seven trials (932 infants) administered sustained inflation with no chest compressions. Use of sustained inflation had no impact on the primary outcomes of this review ‐ mortality in the delivery room (typical RR 2.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.11 to 63.40; participants = 479; studies = 5; I² not applicable) and mortality during hospitalisation (typical RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.51; participants = 932; studies = 7; I² = 19%); the quality of the evidence was low for death in the delivery room (limitations in study design and imprecision of estimates) and was moderate for death before discharge (limitations in study design of most included trials). Amongst secondary outcomes, duration of mechanical ventilation was shorter in the SLI group (mean difference (MD) ‐5.37 days, 95% CI ‐6.31 to ‐4.43; participants = 524; studies = 5; I² = 95%; low‐quality evidence). Heterogeneity, statistical significance, and magnitude of effects of this outcome are largely influenced by a single study: When this study was removed from the analysis, the effect was largely reduced (MD ‐1.71 days, 95% CI ‐3.04 to ‐0.39, I² = 0%). Results revealed no differences in any of the other secondary outcomes (e.g. rate of endotracheal intubation outside the delivery room by 72 hours of age (typical RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.09; participants = 811; studies = 5; I² = 0%); need for surfactant administration during hospital admission (typical RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.10; participants = 932; studies = 7; I² = 0%); rate of chronic lung disease (typical RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.22; participants = 683; studies = 5; I² = 47%); pneumothorax (typical RR 1.44, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.72; studies = 6, 851 infants; I² = 26%); or rate of patent ductus arteriosus requiring pharmacological treatment (typical RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.30; studies = 6, 745 infants; I² = 36%). The quality of evidence for these secondary outcomes was moderate (limitations in study design of most included trials ‐ GRADE) except for pneumothorax (low quality: limitations in study design and imprecision of estimates ‐ GRADE).

Authors' conclusions

Sustained inflation was not better than intermittent ventilation for reducing mortality in the delivery room and during hospitalisation. The number of events across trials was limited, so differences cannot be excluded. When considering secondary outcomes, such as need for intubation, need for or duration of respiratory support, or bronchopulmonary dysplasia, we found no evidence of relevant benefit for sustained inflation over intermittent ventilation. The duration of mechanical ventilation was shortened in the SLI group. This result should be interpreted cautiously, as it can be influenced by study characteristics other than the intervention. Future RCTs should aim to enrol infants who are at higher risk of morbidity and mortality, should stratify participants by gestational age, and should provide more detailed monitoring of the procedure, including measurements of lung volume and presence of apnoea before or during the SLI.

Keywords: Humans; Infant, Newborn; Ductus Arteriosus, Patent; Ductus Arteriosus, Patent/epidemiology; Hospital Mortality; Intubation, Intratracheal; Intubation, Intratracheal/methods; Intubation, Intratracheal/mortality; Positive‐Pressure Respiration; Positive‐Pressure Respiration/methods; Positive‐Pressure Respiration/mortality; Pulmonary Surfactants; Pulmonary Surfactants/administration & dosage; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Respiration, Artificial; Respiration, Artificial/utilization; Resuscitation; Resuscitation/methods; Time Factors

Prolonged lung inflation for neonatal resuscitation

Review question

Does the use of prolonged (or sustained, > 1 second duration) lung inflation rather than standard inflations (≤ 1 second) improve survival and other important outcomes among newly born babies receiving resuscitation at birth?

Background

At birth, the lungs are filled with fluid, which must be replaced by air for babies to breathe properly. Some babies have difficulty establishing effective breathing at birth, and 1 in every 20 to 30 babies receives help to do so. A variety of devices are used to help babies begin normal breathing. Some of these devices allow caregivers to give long (or sustained) inflations. These sustained inflations may help inflate the lungs and may keep the lungs inflated better than if they are not used.

Study characteristics

We collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer the review question and found eight studies enrolling 941 infants. In all studies, babies were born before the due date (from 23 to 36 weeks of gestational age). The sustained inflation lasted between 15 and 20 seconds at pressure between 20 and 30 cmH2O. Most studies provided one or more additional sustained inflations in cases of poor clinical response, for example, persistent low heart rate. We analysed one study (which included only nine babies) separately because researchers combined use of sustained or standard inflations with chest compressions.

Key results

The included studies showed no important differences among babies who received sustained versus standard inflations in terms of mortality, need for intubation during the first three days of life, or chronic lung disease. Babies receiving sustained inflation at birth may spend fewer days on mechanical ventilation. Several ongoing studies might help us to clarify whether differences between the two techniques may occur, as now we cannot exclude that small to moderate differences exist.

Quality of evidence

The quality of evidence is low to moderate because overall only a small number of studies have looked at this intervention; few babies were included in these studies; and some studies could have been better designed.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

We searched for studies that had been published up to February 2017.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Use of initial sustained inflation compared with standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions during resuscitation

| Use of initial sustained inflation compared with standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions during resuscitation | ||||||

|

Patient or population: preterm infants resuscitated using PPV at birth Settings: delivery room in Europe (Austria, Germany, Italy), Canada, Egypt, Thailand Intervention: sustained inflation with no chest compressions Comparison: standard inflations with no chest compressions | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions | Use of initial sustained inflation | |||||

| Death ‐ death in the delivery room | Study population | RR 2.66 (0.11 to 63.4) | 479 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Death ‐ death before discharge | Study population | RR 1.01 (0.67 to 1.51) | 932 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ||

| 82 per 1000 | 83 per 1000 (55 to 124) | |||||

| Need for mechanical ventilation | Study population | RR 0.87 (0.74 to 1.03) | 484 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ||

| 487 per 1000 | 424 per 1000 (360 to 502) | |||||

| Chronic lung disease ‐ BPD any grade | Study population | RR 0.9 (0.69 to 1.19) | 220 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ||

| 483 per 1000 | 435 per 1000 (333 to 575) | |||||

| Chronic lung disease ‐ moderate to severe BPD | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.74 to 1.22) | 683 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ||

| 257 per 1000 | 244 per 1000 (190 to 314) | |||||

| Pneumothorax ‐ any time | Study population | RR 1.44 (0.76 to 2.72) | 851 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,c | ||

| 33 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 (25 to 90) | |||||

| Cranial ultrasound abnormalities ‐ intraventricular haemorrhage grade 3 to 4 | Study population | RR 0.89 (0.58 to 1.37) | 635 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ||

| 120 per 1000 | 107 per 1000 (70 to 164) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

Assumed risk is the risk of the control arm.

aLimitations in study design: all studies at high or unclear risk of bias in at least one domain bImprecision: few events cImprecision: wide confidence intervals

Summary of findings 2.

Use of initial sustained inflation compared with standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions during resuscitation

| Use of initial sustained inflation compared with standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions during resuscitation | ||||||

|

Patient or population: preterm infants resuscitated by PPV at birth Settings: delivery room in Europe (Austria, Germany, Italy), Canada, Egypt, Thailand Intervention: sustained inflation with chest compressions Comparison: standard inflations with chest compressions | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions | Use of initial sustained inflation | |||||

| Death ‐ death before discharge | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 9 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | Only 1 trial included |

| Chronic lung disease ‐ moderate to severe BPD | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 7 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | Only 1 trial included |

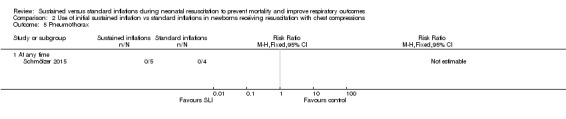

| Pneumothorax ‐ any time | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 9 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | Only 1 trial included |

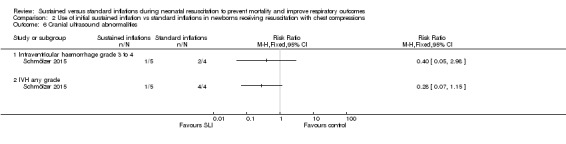

| Cranial ultrasound abnormalities ‐ intraventricular haemorrhage grade 3 to 4 | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 9 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | Only 1 trial included |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

Assumed risk is the risk of the control arm.

aLimitations in study design: included study at high or unclear risk of bias in four domains bImprecision (downgraded by two levels): extremely low sample size, few events

Background

Description of the condition

At birth, infants' lungs are filled with fluid, which must be cleared for effective respiration to occur. Most newly born infants achieve this spontaneously and may use considerable negative pressure (up to ‐50 cmH2O) for initial inspirations (Karlberg 1962; Milner 1977). However, it is estimated that 3% to 5% of newly born infants receive some help to breathe at delivery (Saugstad 1998). Adequate ventilation is the key to successful neonatal resuscitation and stabilisation (Wyckoff 2015). Positive pressure ventilation (PPV) is recommended for infants who have absent or inadequate respiratory efforts, bradycardia, or both, at birth (Wyckoff 2015). Use of manual ventilation devices ‐ self‐inflating bags, flow‐inflating (or anaesthetic) bags, and T‐piece devices ‐ with a face mask or endotracheal tube (ETT) is advised. Although it is not included in the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) guidelines, respiratory support of infants in the delivery room with a mechanical ventilator and a nasopharyngeal tube has been described (Lindner 1999).

Description of the intervention

Devices recommended for PPV in the delivery room differ in terms of physical characteristics and ability to deliver sustained lung inflation (SLI). The most commonly used self‐inflating bag (O'Donnell 2004a; O'Donnell 2004b) may be of insufficient size to support sustained inflation (> 1 second). Both flow‐inflating bags and T‐pieces may be used to consistently deliver inflations > 1 second. Although target inflation pressures and long inspiratory times are achieved more consistently in mechanical models when T‐piece devices rather than bags are used, no recommendation can be made as to which device is preferable (Wyckoff 2015; Wyllie 2015). Positive end‐expiratory pressure (PEEP) is very important for aerating the lungs and improving oxygenation; SLI consists of prolonged high‐level PEEP.

How the intervention might work

When airways are liquid‐filled, it might be unnecessary to interrupt inflation pressures to allow the lung to deflate and exhale CO2 (Hooper 2016). Boon 1979 described a study of 20 term infants delivered by Caesarean section under general anaesthesia who were resuscitated with a T‐piece via an ETT. Trial authors reported that gas continued to flow through the flow sensor placed between the T‐piece and the ETT toward the infant at the end of a standard inflation of 1 second on respiratory traces obtained (Boon 1979). On the basis of this observation, this group performed a non‐randomised trial of sustained inflations given via a T‐piece and an ETT to nine term infants during delivery room resuscitation. Investigators reported that initial inflation with a T‐piece lasting 5 seconds produced a two‐fold increase in inflation volume compared with standard resuscitation techniques (Vyas 1981). Citing these findings, a retrospective cohort study described the effects of a change in management strategy for extremely low birth weight infants in the delivery room (Lindner 1999). The new management strategy included the introduction of an initial sustained inflation of 15 seconds obtained with a mechanical ventilator via a nasopharyngeal tube. This change in strategy was associated with a reduction in the proportion of infants intubated for ongoing respiratory support without an apparent increase in adverse outcomes. Pulmonary morbidity in very low birth weight infants was reported to be related directly to mortality in 50% of cases of death (Drew 1982). Moreover, multiple SLIs in very preterm infants improved both heart rate and cerebral tissue oxygen saturation, in the absence of any detrimental effects (Fuchs 2011). An observational study showed that sustained inflation of 10 seconds at 25 cmH2O in 70 very preterm infants at birth was not effective for infants who were not breathing, possibly owing to active glottic adduction (van Vonderen 2014). Newly born infants frequently take a breath and then prolong expiration via glottic closure and diaphragmatic braking, giving themselves prolonged end‐expiratory pressure.

Why it is important to do this review

Recommendations regarding use of sustained inflation at birth have varied between international bodies. Although European Resuscitation Council guidelines suggest giving five inflation breaths if the newborn is gasping or is not breathing (Wyllie 2015), the American Heart Association states that evidence is insufficient to recommend an optimum inflation time (Wyckoff 2015). Differences between these guidelines and their algorithms are intriguing (Klingenberg 2016). A narrative review reported that sustained inflation may reduce the need for mechanical ventilation among preterm infants at risk for respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) (Lista 2010). The same review showed that respiratory outcomes among infants receiving sustained inflation (25 cmH2O for 15 seconds) were improved over those reported for an historical group (Lista 2011).

This review updates the existing review "Sustained versus standard inflations during neonatal resuscitation to prevent mortality and improve respiratory outcomes", which was published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews in 2015 (O'Donnell 2015).

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of an initial sustained (> 1 second duration) lung inflation (SLI) versus standard inflations (≤ 1 second) in newborn infants receiving resuscitation with intermittent PPV.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs. We excluded observational studies (case‐control studies, case series) and cluster‐RCTs.

Types of participants

Term and preterm infants resuscitated via PPV at birth.

Types of interventions

Interventions included resuscitation with initial sustained (> 1 second) inflation versus resuscitation with regular (≤ 1 second) inflations:

with no chest compressions as part of the initial resuscitation (primary comparison); or

with chest compressions as part of the initial resuscitation (secondary comparison).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Death in the delivery room

Death during hospitalisation

Death to latest follow‐up

Secondary outcomes

Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes

Heart rate at 5 minutes

Endotracheal intubation in the delivery room

Endotracheal intubation outside the delivery room during hospitalisation

Surfactant administration in the delivery room or during hospital admission

Need for mechanical ventilation

Duration in hours of respiratory support (i.e. nasal continuous airway pressure and ventilation via an ETT considered separately and in total)

Duration in days of supplemental oxygen requirement

Chronic lung disease: need for supplemental oxygen at 28 days of life; need for supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks of gestational age for infants born at or before 32 weeks of gestation

Air leaks (pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, pulmonary interstitial emphysema) reported individually or as a composite outcome

Cranial ultrasound abnormalities: any intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), grade 3 or 4 according to the Papile classification (Papile 1978), and cystic periventricular leukomalacia

Seizures including clinical and electroencephalographic

Hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy for term and late preterm infants (grade 1 to 3 (Sarnat 1976))

Long‐term neurodevelopmental outcomes (rates of cerebral palsy on physician assessment, developmental delay (i.e. intelligence quotient (IQ) 2 standard deviations (SDs) < mean on validated assessment tool (e.g. Bayley's Mental Developmental Index))

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) (all stages and ≥ stage 3)

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) (pharmacological treatment and surgical ligation)

Search methods for identification of studies

See Cochrane Neonatal Review Group (CNRG) search strategy.

Electronic searches

We used the criteria and standard methods of Cochrane and the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group (see the Cochrane Neonatal search strategy for specialized register).

We conducted a comprehensive search that included the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 1) in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE via PubMed (1966 to 17 February 2017); Embase (1980 to 17 February 2017); and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1982 to 17 February 2017), using the following search terms: (sustained inflation) OR (sustained AND inflation) OR (sustained AND (inflat* AND (lung OR pulmonary))), plus database‐specific limiters for RCTs and neonates (see Appendix 1 for full search strategy for each database). We did not apply language restrictions. We searched clinical trials registries for ongoing and recently completed trials (clinicaltrials.gov; the World Health Organization International Trials Registry and Platform ‐ www.whoint/ictrp/search/en/; and the ISRCTN Registry).

Searching other resources

We also searched abstracts of the Pediatric Academic Society (PAS) from 2000 to 2017, electronically through the PAS website (abstractsonline), using the following key words: "sustained inflation" AND "clinical trial".

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For this update, two review authors (MB, MGC) independently screened all titles and abstracts to determine which trials met the inclusion criteria. We retrieved full‐text copies of all papers that were potentially relevant. We resolved disagreements by discussion between review authors.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (MB, MGC) independently undertook data abstraction using a data extraction form developed ad hoc and integrated with a modified version of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC) data collection checklist (EPOC 2015).

We extracted the following characteristics from each included trial.

Administrative details: study author(s); published or unpublished; year of publication; year in which trial was conducted; details of other relevant papers cited.

Trial details: study design; type, duration, and completeness of follow‐up; country and location of study; informed consent; ethics approval.

Details of participants: birth weight; gestational age; number of participants.

Details of intervention: type of ventilation device used; type of interface; duration and level of pressure of sustained lung inflation (SLI).

Details of outcomes: death during hospitalisation or to latest follow‐up; heart rate at 5 minutes; duration in hours of respiratory support; duration in days of supplemental oxygen requirement; long‐term neurodevelopmental outcomes; any adverse events.

We resolved disagreements by discussion between review authors. When available, we described ongoing trials identified by detailing primary trial author, research question(s) posed, and methods and outcome measures applied, together with an estimate of the reporting date.

When queries arose or additional data were required, we contacted trial authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (MB, SZ) independently assessed risk of bias (low, high, or unclear) of all included trials using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool (Higgins 2011) for the following domains.

Sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Any other bias.

We resolved disagreements by discussion or via consultation with a third assessor. See Appendix 2 for a detailed description of risk of bias for each domain.

Selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment)

Random sequence generation

For each included trial, we categorised risk of bias regarding random sequence generation as follows.

Low risk ‐ adequate (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator).

High risk ‐ inadequate (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number).

Unclear risk ‐ no or unclear information provided.

Allocation concealment

For each included trial, we categorised risk of bias regarding allocation concealment as follows.

Low risk ‐ adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes).

High risk ‐ inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth).

Unclear risk ‐ no or unclear information provided.

Performance bias

Owing to the nature of the intervention, all trials were unblinded, leading to high risk of performance bias.

Detection bias

For each included trial, we categorised the methods used to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or different classes of outcomes.

Attrition bias

For each included trial and for each outcome, we described completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from analysis. We noted whether attrition and exclusions were reported, numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total number of randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion when reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes.

Reporting bias

For each included trial, we described how we investigated the risk of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found. We assessed methods as follows.

Low risk ‐ adequate (when it is clear that all of a trial's prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported).

High risk ‐ inadequate (when not all of a trial's prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so cannot be used; or the trial failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to be reported).

Unclear risk ‐ no or unclear information provided (study protocol was not available).

Other bias

For each included trial, we described any important concerns that we had about other possible sources of bias (e.g. whether a potential source of bias was related to the specific trial design, whether the trial was stopped early owing to some data‐dependent process). We assessed whether each trial was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias as follows.

Low risk ‐ no concerns of other bias raised.

High risk ‐ concerns raised about multiple looks at data with results made known to investigators, differences in numbers of participants enrolled in abstract, and final publications of the paper.

Unclear ‐ concerns raised about potential sources of bias that could not be verified by contacting trial authors.

We did not score blinding of the intervention because this was not applicable.

One review author entered data into RevMan 2014, and a second review author checked entered data for accuracy.

Measures of treatment effect

We conducted measures of treatment effect data analysis using RevMan 2014. We determined outcome measures for dichotomous data (e.g. death, endotracheal intubation in the delivery room, frequency of retinopathy) as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We calculated continuous data (e.g. duration of respiratory support, Apgar score) using mean differences (MDs) and SDs.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of randomisation was the intended unit of analysis (individual neonate).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted trial authors to request missing data when needed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

As a measure of consistency, we used the I² statistic and the Q (Chi²) test (Deeks 2011). We judged statistical significance of the Q (Chi²) statistic by P < 0.10 because of the low statistical power of the test. We used the following cut‐offs for heterogeneity: < 25% no (none) heterogeneity; 25% to 49% low heterogeneity; 50% to 74% moderate heterogeneity; and ≥ 75% high heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). We combined trial results using the fixed‐effect model, regardless of statistical evidence of heterogeneity effect sizes.

Assessment of reporting biases

See Appendix 2.

Data synthesis

We performed statistical analyses using RevMan 2014. We used the standard methods of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group. For categorical data, we used RRs, relative risk reductions, and absolute risk difference (RDs). We obtained means and SDs for continuous data and performed analyses using MDs and WMDs when appropriate. We calculated 95% CIs. We presented the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) and the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH), as appropriate. For each comparison reviewed, meta‐analysis could be feasible if we identified more than one eligible trial, and if homogeneity among trials was sufficient with respect to participants and interventions. We combined trials using the fixed‐effect model, regardless of statistical evidence of heterogeneity effect sizes. For estimates of RR and RD, we used the Mantel‐Haenszel method.

Quality of evidence

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the quality of evidence for the following (clinically relevant) outcomes: death in the delivery room or during hospitalisation; endotracheal intubation in the delivery room or outside the delivery room during hospitalisation; surfactant administration in the delivery room or during hospital admission; need for mechanical ventilation; chronic lung disease; air leaks; and cranial ultrasound abnormalities.

Two review authors independently assessed the quality of evidence for each of the outcomes above. We considered evidence from RCTs as high quality but downgraded evidence one level for serious (or two levels for very serious) limitations on the basis of the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of evidence, precision of estimates, and presence of publication bias. We used the GRADEpro GDT Guideline Development Tool to create a ‘Summary of findings’ table to report the quality of evidence.

The GRADE approach yields an assessment of the quality of a body of evidence according to one of four grades.

High: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform the following subgroup analyses of the safety and efficacy of sustained inflation during resuscitation in subgroups.

Term (≥ 37 weeks of gestation) and preterm (< 37 weeks of gestation) infants.

Type of ventilation device used (self‐inflating bag, flow‐inflating bag, T‐piece, mechanical ventilator).

Interface used (i.e. face mask, ETT, nasopharyngeal tube).

Duration of sustained lung inflation (i.e. > 1 second to 5 seconds, > 5 seconds).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to explore effects of the methodological quality of trials and checked to ascertain whether studies with high risk of bias overestimated treatment effects.

Results

Description of studies

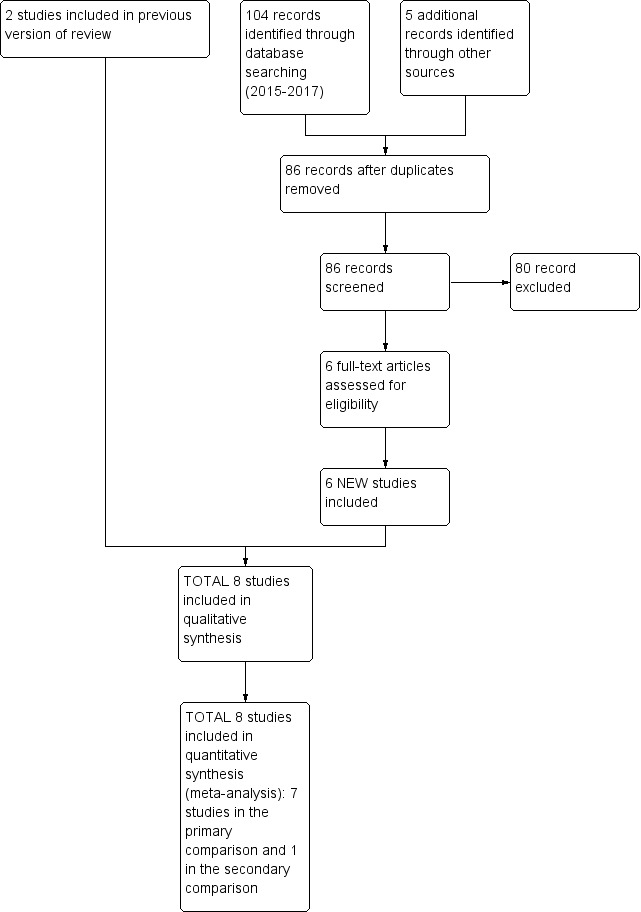

We have provided results of the search for this review update in the study flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram: review update.

See Characteristics of included studies,Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of ongoing studies sections for details.

Included studies

Eight trials recruiting 941 infants (473 in SLI groups, 468 in control groups) met the inclusion criteria (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schmölzer 2015; Schwaberger 2015). We pooled seven trials (with 932 infants) in the primary comparison (i.e. use of sustained inflation with no chest compressions) (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015). In contrast to other trials, Schwaberger 2015 sought to use near‐infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) to investigate whether SLI affected physiological changes in cerebral blood volume and oxygenation. We could not perform any meta‐analysis in the secondary comparison (intervention superimposed on uninterrupted chest compressions) because we included only one trial (a pilot study of nine preterm infants) (Schmölzer 2015).

We have listed characteristics of populations and interventions and comparisons of the eight trials under Characteristics of included studies and in Table 5.

Table 1.

Populations and interventions in included trials

|

Trial (no. infants) |

Antenatal steroids | Gestational age, weeks | Birth weight, grams | Device/Interface | Interventions/Controls | ||||

| SLI | Control | SLI | Control | SLI | Control | SLI and control | SLI | Control | |

| El‐Chimi 2017 (112) | 39% | 34.5% | mean 31.1 (SD 1.7) | mean 31.3 (SD 1.7) | mean 1561 (SD 326) | mean 1510 (SD 319) | Mask and T‐piece in SLI group Mask and self‐inflating bag with an oxygen reservoir in control group |

PIP of 20 cmH2O for 15 seconds, followed by PEEP of 5 cmH2O If needed: a second SLI of 15 seconds of 25 cmH2O for 15 seconds, followed by PEEP of 6 cmH2O; then a third SLI of 15 seconds of 30 cmH2O for 15 seconds, followed by PEEP of 7 cmH2O If still not satisfactory: intubated in delivery room |

PIP maximum 40 cmH2O, rate of 40 to 60 breaths/min for 30 seconds |

| Jiravisitkul 2017 (81) | 63% | 74% | 25 to 28 weeks: n = 17; 29 to 32 weeks: n = 26 |

25 to 28 weeks: n = 16; 29 to 32 weeks: n = 22 |

mean 1206 (SD 367) | mean 1160 (SD 411) | Mask and T‐piece | PIP of 25 cmH2O for 15 seconds If HR 60 to 100 beats/min and/or poor respiratory effort: a second SLI (25 cmH2O, 15 seconds) |

PIP 15 to 20 cmH2O, PEEP 5 cmH2O for 30 seconds, followed by resuscitation according to AHA guidelines |

| Lindner 2005 (61) | 81% | 80% | median 27.0 (IQR 25.0 to 28.9) | median 26.7 (IQR 25.0 to 28.9) | median 870 (IQR 410 to 1320) | median 830 (IQR 370 to 1370) | Nasopharyngeal tube (fixed at 4 to 5 cm) and mechanical ventilator | PIP of 20 cmH2O for 15 seconds If response was not satisfactory: 2 further SLIs of 15 seconds (25 and 30 cmH2O). Then PEEP at 4 to 6 cmH2O |

PIP 20 cmH2O, PEEP 4 to 6 cmH2O; inflation time 0.5 seconds; inflation rate 60 per min. Then, PEEP at 4 to 6 cmH2O |

| Lista 2015 (301) | 87% | 91% | mean 26.8 (SD 1.2); 25 to 26 weeks: n = 55 27 to 28 weeks: n = 88 |

mean 26.8 (SD 1.1); 25 to 26 weeks: n = 52; 27 to 28 weeks: n = 96 |

mean 894 (SD 247) | mean 893 (SD 241) | Mask and T‐piece | PIP 25 cmH2O for 15 seconds. Then reduced to PEEP of 5 cmH2O | PEEP 5 cmH2O, followed by resuscitation according to AHA guidelines |

| Mercadante 2016 (185) | 40% | 32% | mean 35.2 (SD 0.8) | mean 35.2 (SD 0.8) | mean 2345 (SD 397) | mean 2346 (SD 359) | Mask and T‐piece | PIP 25 cmH2O for 15 seconds, followed by PEEP of 5 cmH2O. In case of persistent heart failure (HR < 100 bpm): SLI repeated | PEEP 5 cmH2O, followed by resuscitation according to AAP guidelines |

| Ngan 2017 (162) | 78% | 70% | mean 28 (SD 2.5) | mean 28 (SD 2.5) | mean 1154 (SD 426) | mean 1140 (SD 406) | Mask and T‐piece | Two PIPs of 24 cmH2O. Duration of first SLI was 20 seconds. Duration of second SLI was 20 or 10 seconds, guided by ECO2 values. After SLIs, CPAP if breathing spontaneously or, if found to have apnoea or laboured breathing, mask IPPV at a rate of 40 to 60 bpm | IPPV, rate of 40 to 60 inflations/min until spontaneous breathing, at which time CPAP will be provided |

| Schmölzer 2015 (9) | 80%a | 100%a | mean 24.6 (SD 1.3)a | mean 25.6 (SD 2.3)a | mean 707 (SD 208)a | mean 808 (SD 192)a | Mask and T‐piecea | PIP for 20 + 20 secondsa during chest compressions | 3:1 compression:ventilation ratio according to resuscitation guidelines |

| Schwaberger 2015 (40) | not reported | not reported | mean 32.1 (SD 1.4) | mean 32.1 (SD 1.6) | mean 1692 (SD 297) | mean 1722 (SD 604) | Mask and T‐piece | PIP 30 cmH2O for 15 seconds, to be repeated once or twice with HR remaining < 100 bpm. Infants with HR > 100 bpm: PPV at 30 cmH2O PIP or CPAP at PEEP level of 5 cmH2O depending on respiratory rate | Resuscitation according to AHA guidelines PEEP 5 cmH2O if respiratory rate > 30 and signs of respiratory distress PPV at 30 cmH2O PIP if insufficient breathing efforts |

aInformation provided by study authors

Settings and populations

Researchers conducted the included studies on four different continents: two in Italy (Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016), two in Canada by the same contact author (Ngan 2017; Schmölzer 2015), one in Germany (Lindner 2005), one in Austria (Schwaberger 2015), one in Egypt (El‐Chimi 2017), and one in Thailand (Jiravisitkul 2017). Only one study was conducted at multiple centres (Lista 2015). Five of the six trials identified for this update included infants with mean birth weight > 1 kg (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015), whereas the two previously included studies (Lindner 2005; Lista 2015) and the pilot trial (Schmölzer 2015) enrolled extremely low birth weight infants. Mercadante 2016 was the only trial conducted in late preterm infants. No trials enrolled full‐term infants. Table 5 shows additional information on populations.

Interventions

Trials pooled in the primary comparison (i.e. without chest compressions) reported that peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) was sustained for 15 seconds in six trials (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Schwaberger 2015) and for 20 seconds in Ngan 2017. However, levels of PIP ranged from 20 cmH2O (El‐Chimi 2017; Lindner 2005) to 24 (Ngan 2017), 25 (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016), and 30 cmH2O (Schwaberger 2015). Investigators provided additional SLIs in cases of poor response, with the same (Jiravisitkul 2017; Mercadante 2016; Schwaberger 2015) or higher PIP (El‐Chimi 2017; Lindner 2005); researchers in Ngan 2017 based the duration of the second SLI on exhaled CO2 values. As regards interface and ventilation devices, most included trials used mask and T‐piece. However, Lindner 2005 used nasopharyngeal tube and ventilator, and El‐Chimi 2017 introduced a relevant bias into the study design by using a T‐piece ventilator in the SLI group and a self‐inflating bag in the control group (mask in both SLI and control groups). No trials reported whether prespecified levels of pressure for the SLI were actually delivered according to the protocol. Study authors did not monitor leaks at the mask and lung volumes during the manoeuvre. Whether the infant breathed before or during the SLI was not recorded: Apnoeic newborns at birth are known to show less gain in lung volume during an SLI than actively breathing infants (Lista 2017).

For the secondary comparison, in which infants in both SLI and control groups were resuscitated with chest compressions, duration of SLI was 20 + 20 seconds (Schmölzer 2015).

Table 5 shows additional information on interventions.

Excluded studies

We have summarised the reasons for exclusion of potentially eligible trials (Bouziri 2011; Harling 2005; te Pas 2007) in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

In particular, we excluded te Pas 2007 because sustained inflation was only one element of the intervention, and because it is not possible to determine the relative contributions of various elements of this intervention to differences observed between groups. We excluded Harling 2005, as investigators randomised infants in this trial to receive inflation for 2 seconds or 5 seconds at initiation of PPV. All infants thus received sustained (> 1 second) inflations as defined in our protocol (O'Donnell 2004).

For the 2017 update, we excluded no eligible studies.

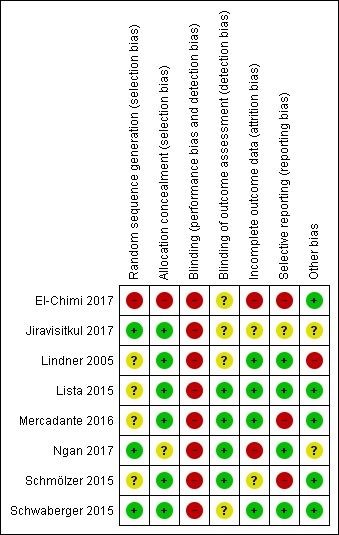

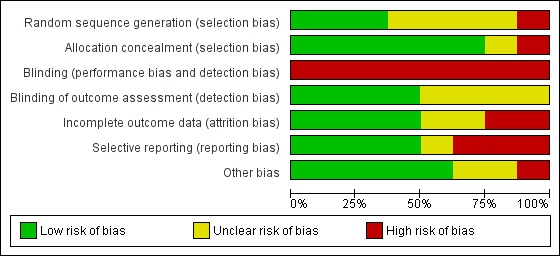

Risk of bias in included studies

We have presented a summary of the 'Risk of bias' assessment in Figure 2 and Figure 3. We have provided details of the methodological quality of included trials in the Characteristics of included studies section.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included trial.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included trials.

Allocation

One trial had high risk of selection bias: This quasi‐randomised trial (odd‐numbered sheets indicated allocation to the SLI group, and even‐numbered sheets to the control group) did not use opaque envelopes (information provided by study authors) (El‐Chimi 2017). In Jiravisitkul 2017 and Schwaberger 2015, risk of selection bias was low as regards random sequence generation and allocation concealment (opaque, numbered envelopes). In Ngan 2017, risk of selection bias was low as regards random sequence generation and was unclear for allocation concealment: Timing of randomisation resulted in many post‐randomisation exclusions, as results showed more post‐randomisation exclusions in the SLI group than in the control group. In the other four trials, risk of selection bias was unclear as regards random sequence generation and was low as regards allocation concealment (opaque, numbered envelopes) (Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Schmölzer 2015).

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the intervention, all trials were unblinded, leading to high risk of performance bias. However, four trials blinded researchers assessing trial endpoints to the nature of study treatments (Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schmölzer 2015).

Incomplete outcome data

El‐Chimi 2017 referred almost half of enrolled infants to other NICUs; we excluded these studies from analysis owing to failure of follow‐up, although the primary outcome of the study (treatment failure/success within 72 hours) could have been determined and reported for these infants. In Ngan 2017, post‐randomisation exclusion (27%) resulted in fewer included infants in the SLI group. Most trials accounted for all outcomes (Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Schwaberger 2015).

Selective reporting

Four trials provided complete results for all reported outcomes (Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015).

Other potential sources of bias

El‐Chimi 2017 and Schwaberger 2015 did not report sample size calculations. For Schwaberger 2015, investigators registered the protocol after study initiation. Jiravisitkul 2017 planned sample sizes of 40 infants for each group but allocated only 38 to the control group. Lindner 2005 was stopped after the interim analysis. It was unclear why study authors made this decision. Ngan 2017 did not achieve the planned sample size; in addition, the incidence of the primary outcome in the control group was less than that assumed for the sample size calculation, leading to lack of power to detect the chosen effect size. The other trials appear free of other bias.

We were unable to explore possible bias through generation of funnel plots because fewer than ten trials met the inclusion criteria of this Cochrane review.

Effects of interventions

Primary comparison: use of initial sustained inflation versus standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions

Primary outcomes

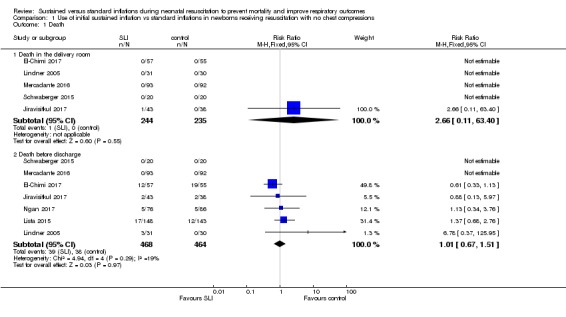

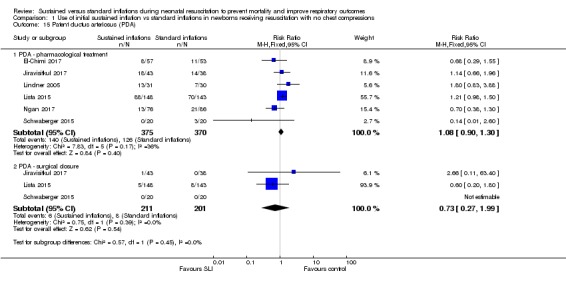

Death (Outcome 1.1)

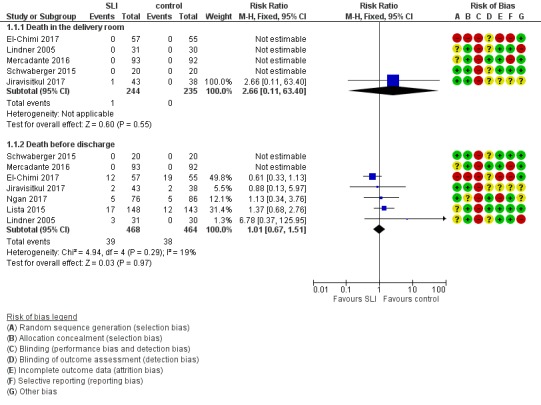

Death in the delivery room (Outcome 1.1.1)

Five trials (N = 479) reported this outcome (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016; Schwaberger 2015); one event occurred in the SLI group in Jiravisitkul 2017 (death in delivery room at 15 to 20 minutes of life, severe birth asphyxia as the result of a prolapsed cord), and none in the other four trials (typical RR 2.66, 95% CI 0.11 to 63.40; typical RD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.02; participants = 479; studies = 5; I² not applicable for RR and I² = 0% for RD; Analysis 1.1 and Figure 4). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005).

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 1 Death.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, outcome: 1.1 Death.

Death during hospitalisation (Outcome 1.2.1)

All trials included in the primary comparison (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015) reported mortality during hospitalisation (typical RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.51; typical RD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.03; participants = 932; studies = 7; I² = 19% for RR and I² = 0% for RD; Analysis 1.1 and Figure 4).

We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005).

In El‐Chimi 2017, 12 and 19 infants in SLI and control groups, respectively, died. In Jiravisitkul 2017, two infants in each group died: In the SLI group, one died of severe birth asphyxia as the result of a prolapsed cord, and the other died at 3 hours of life of suspected umbilical catheter migration with haemothorax; in the control group, one died of severe respiratory distress syndrome at 2 hours of life, and the other of septic shock at 168 days of life. In Lindner 2005, three deaths occurred in the sustained inflation group: at day 1 (respiratory failure), at day 36 (necrotising enterocolitis), and at day 107 (liver fibrosis of unknown origin). In Lista 2015, 12 infants in the control group and 17 in the sustained inflations group died during the trial. Mercadante 2016 and Schwaberger 2015 reported no events.

Secondary outcomes

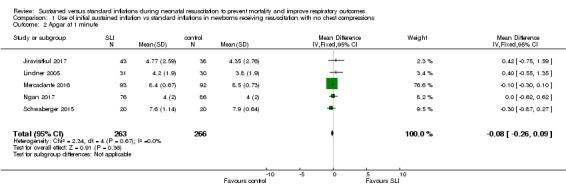

Apgar score at one minute (Outcome 1.2)

Five trials (N = 529) (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015) reported this outcome (MD ‐0.08, 95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.09; participants = 529; studies = 5; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.2). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015).

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 2 Apgar at 1 minute.

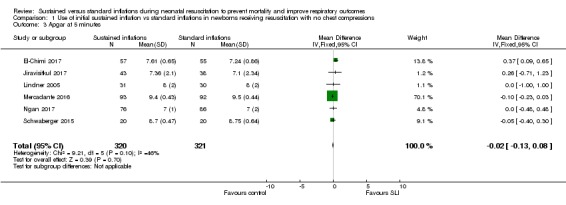

Apgar score at five minutes (Outcome 1.3)

Six trials (N = 641) (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015) reported this outcome (MD ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.08; participants = 641; studies = 6; I² = 46%; Analysis 1.3). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015).

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 3 Apgar at 5 minutes.

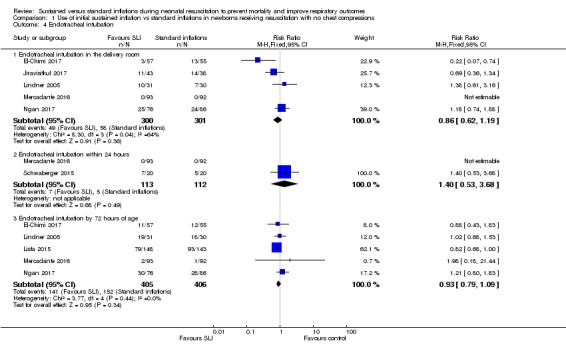

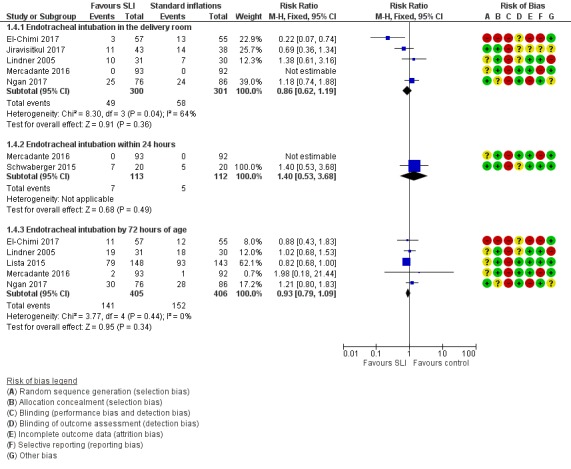

Endotracheal intubation (Outcome 1.4)

Endotracheal intubation in the delivery room (Outcome 1.4.1)

Five trials (N = 601) (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.19; typical RD ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.03; participants = 601; studies = 5; I² = 64% for RR and I² = 74% for RD; Analysis 1.4; Figure 5). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Mercadante 2016).

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 4 Endotracheal intubation.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, outcome: 1.4 Endotracheal intubation.

Endotracheal intubation outside the delivery room within 24 hours (Outcome 1.4.2)

Two trials (N = 225) (Mercadante 2016; Schwaberger 2015) reported this outcome (RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.53 to 3.68; RD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.07; participants = 225; studies = 2). The test for heterogeneity was not applicable because only one trial (Lindner 2005) reported events (Analysis 1.4; Figure 5). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Mercadante 2016).

Endotracheal intubation outside the delivery room by 72 hours (Outcome 1.4.3)

Five included trials (N = 811) (El‐Chimi 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.09; typical RD ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.03; participants = 811; studies = 5; I² = 0% for RR and I² = 53% for RD) (Analysis 1.4;Figure 5). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Mercadante 2016).

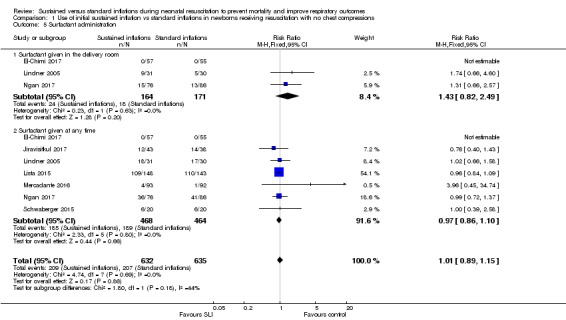

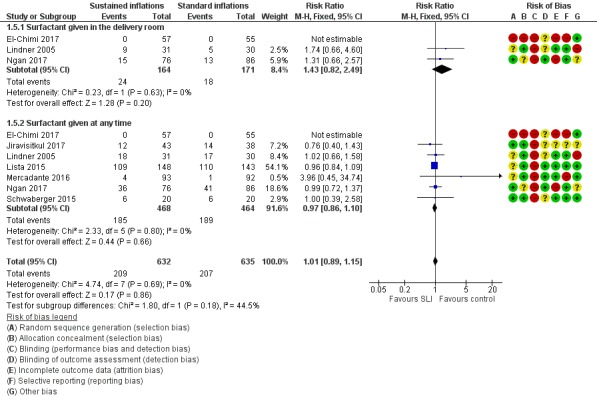

Surfactant administration (Outcome 1.5)

Surfactant administration in the delivery room (Outcome 1.5.1)

Three trials (N = 335) (El‐Chimi 2017; Lindner 2005; Ngan 2017) reported this outcome (typical RR 1.43, 95% CI 0.82 to 2.49; typical RD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.11; participants = 335; studies = 3; I² = 0% for RR and I² = 72% for RD; Analysis 1.5;Figure 6). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (El‐Chimi 2017).

Analysis 1.5.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 5 Surfactant administration.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, outcome: 1.5 Surfactant administration.

Surfactant administration during hospital admission (Outcome 1.5.2)

All trials included in the primary comparison (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015) (N = 932) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.10; typical RD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.04; participants = 932; studies = 7; I² = 0% for RR and I² = 0% for RD; Analysis 1.5;Figure 6). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (El‐Chimi 2017; Lindner 2005;Mercadante 2016).

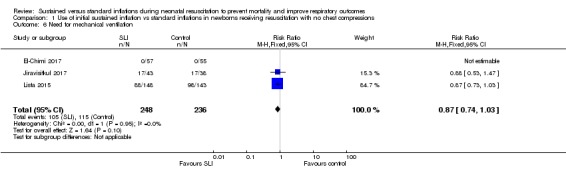

Need for mechanical ventilation (Outcome 1.6)

Three trials (N = 484) reported this outcome (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lista 2015) (typical RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.03; typical RD ‐0.06, 95% CI ‐0.14 to 0.01; participants = 484; studies = 3; I² = 0% for RR and I² = 85% for RD) (Analysis 1.6). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (El‐Chimi 2017).

Analysis 1.6.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 6 Need for mechanical ventilation.

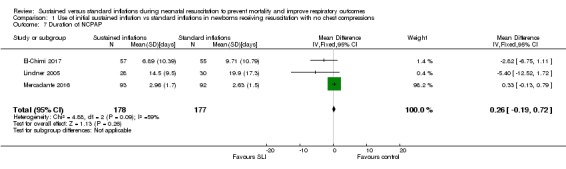

Duration of nasal continuous airway pressure (Outcome 1.7)

Three trials (N = 355) reported this outcome (El‐Chimi 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016) (MD 0.26 days, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.72; participants = 355; studies = 3; I² = 59%) (Analysis 1.7). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors; data for this outcome refer to survivors at time of assessment (El‐Chimi 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016).

Analysis 1.7.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 7 Duration of NCPAP.

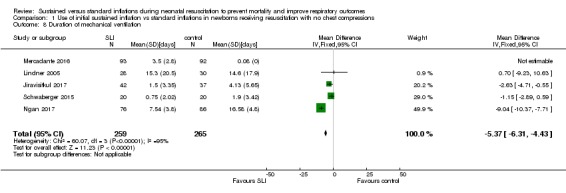

Duration of ventilation via an ETT (Outcome 1.8)

Five trials (N = 524) reported this outcome (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015) (MD ‐5.37 days, 95% CI ‐6.31 to ‐4.43; participants = 524; studies = 5; I² = 95%; Analysis 1.8). Data for this outcome refer to survivors at time of assessment (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Jiravisitkul 2017; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015). Heterogeneity, statistical significance, and magnitude of effects of this outcome are largely influenced by a single study (Ngan 2017): when this study was removed from the analysis, the effect was largely reduced (MD ‐1.71 days, 95% CI ‐3.04 to ‐0.39, I² = 0%).

Analysis 1.8.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 8 Duration of mechanical ventilation.

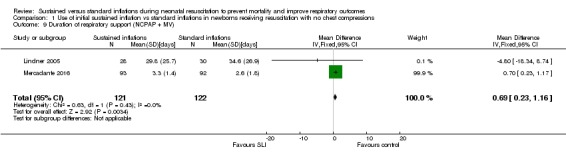

Duration of respiratory support (nasal continuous airway pressure and ventilation via an ETT, considered in total) (Outcome 1.9)

Two trials (N = 243) reported this outcome (Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016) (MD 0.69 days, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.16; participants = 243; studies = 2; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.9). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors; data refer to survivors at time of assessment (Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016).

Analysis 1.9.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 9 Duration of respiratory support (NCPAP + MV).

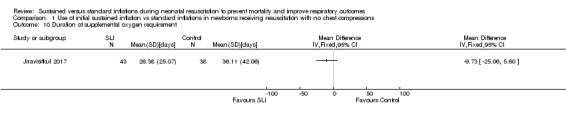

Duration of supplemental oxygen requirement (days) (Outcome 1.10)

One trial (N = 81) reported this outcome (Jiravisitkul 2017) (MD ‐9.73, 95% CI ‐25.06 to 5.60; participants = 81; studies = 1; Analysis 1.10). The test for heterogeneity was not applicable. We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Jiravisitkul 2017).

Analysis 1.10.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 10 Duration of supplemental oxygen requirement.

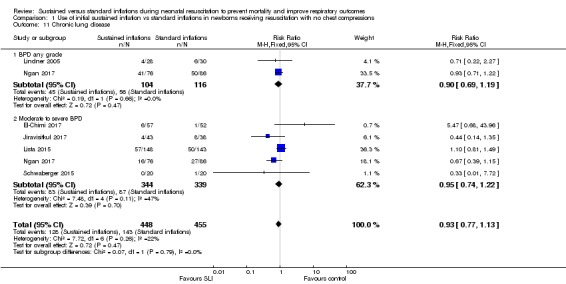

Chronic lung disease (i.e. need for supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks of gestational age for infants born at or before 32 weeks of gestation) (Outcome 1.11)

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) any grade (Outcome 1.11.1)

Two trials (N = 220) reported this outcome (Lindner 2005; Ngan 2017) (typical RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.19; typical RD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.08; participants = 220; studies = 2; I² = 0% for RR and I² = 0% for RD). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors; data refer to survivors at time of assessment (Lindner 2005; Analysis 1.11).

Analysis 1.11.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 11 Chronic lung disease.

Moderate to severe BDP (Outcome 1.11.2)

Five included trials (N = 683) (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lista 2015; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.22; typical RD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.05; participants = 683; studies = 5; I² = 47% for RR and I² = 57% for RD; Analysis 1.11).

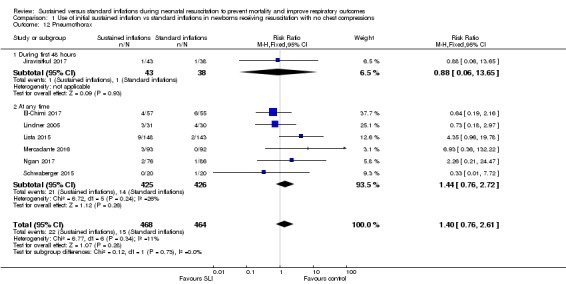

Air leaks (pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, pulmonary interstitial emphysema) reported individually or as a composite outcome (Outcome 1.12)

Pneumothorax in first 48 hours of life (Outcome 1.12.1)

One trial (N = 81) (Jiravisitkul 2017) reported this outcome (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.06 to 13.65; RD ‐0.00, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.06). The test for heterogeneity was not applicable (Analysis 1.12).

Analysis 1.12.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 12 Pneumothorax.

Pneumothorax at any time (Outcome 1.12.2)

Six included studies (N = 851) (El‐Chimi 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015) reported this outcome (typical RR 1.44, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.72; typical RD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.04; studies = 6; 851 infants; I² = 26% for RR and I² = 2% for RD; Analysis 1.12).

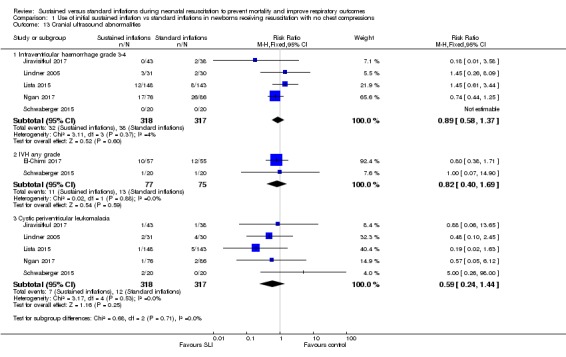

Cranial ultrasound abnormalities (Outcome 1.13)

Intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), grade 3 or 4 according to the Papile classification (Papile 1978) (Outcome 1.13.1)

Five included trials (N = 635) (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.37; typical RD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.03; studies = 5; 635 infants; I2 = 4% for RR and I2 = 0% for RD; Analysis 1.13).

Analysis 1.13.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 13 Cranial ultrasound abnormalities.

IVH any grade (Outcome 1.13.2)

Two included trials (N = 152) (El‐Chimi 2017; Schwaberger 2015) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.69; typical RD ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.08; studies = 3; 152 infants; I² = 0% for RR and I² = 0% for RD; Analysis 1.13).

Cystic periventricular leukomalacia (Outcome 1.13.3)

Five included trials (N = 635) (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.24 to 1.44; typical RD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.01; studies = 5; 635 infants; I² = 0% for RR and I² = 0% for RD; Analysis 1.13).

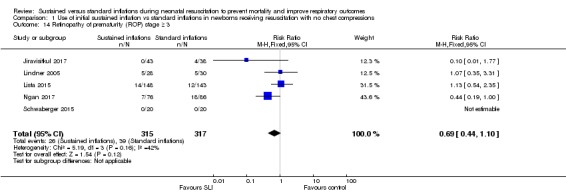

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) ≥ stage 3 (Outcome 1.14)

Five trials (N = 632) (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.10; typical RD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.01; studies = 5; 632 infants; I² = 42% for RR and I² = 40% for RD; Analysis 1.14). For Lindner 2005, data refer to survivors at time of assessment (Analysis 1.14).

Analysis 1.14.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 14 Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) stage ≥ 3.

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) (Outcome 1.15)

Rate of PDA ‐ pharmacological treatment (Outcome 1.15.1)

Six included trials (N = 745) (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015) reported this outcome (typical RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.30; typical RD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.09; studies = 6; 745 infants; I² = 36% for RR and I² = 58% for RD; Analysis 1.15). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schwaberger 2015).

Analysis 1.15.

Comparison 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions, Outcome 15 Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA).

Rate of PDA ‐ surgical closure (Outcome 1.15.2)

Three trials (N = 412) (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lista 2015; Schwaberger 2015) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.99; typical RD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.03; studies = 3; 412 infants; I² = 0% for RR and I² = 26% for RD; Analysis 1.15). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schwaberger 2015).

The data refer to all randomised infants, unless otherwise specified.

No data were reported for the following outcomes: heart rate; need for supplemental oxygen at 28 days of life; seizures including clinical and electroencephalographic; hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy in term and late preterm infants (grade 1 to 3; Sarnat 1976); and long‐term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Death to latest follow‐up: No data were provided in addition to those already presented for death during hospitalisation (Analysis 1.1).

Subgroup analysis for the primary comparison

For the primary comparison, we were unable to conduct any of the four prespecified subgroup analyses because:

no term infants were included;

for ventilation devices, all trials used a T‐piece except Lindner 2005 (mechanical ventilator): We did not perform a separate analysis because of the very small sample size and the presence of high or unclear risk of bias in most GRADE domains. Moreover, El‐Chimi 2017 used a T‐piece ventilator in the SLI group and a self‐inflating bag in the control group; thus we could not include this as a subgroup;

for interface, all trials used a face mask, except Lindner 2005 (nasopharyngeal tube): As for ventilation devices, we did not perform a separate analysis for Lindner 2005; and

no trials used SLI < 5 seconds.

Secondary comparison: use of initial sustained inflation versus standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions

Primary outcomes

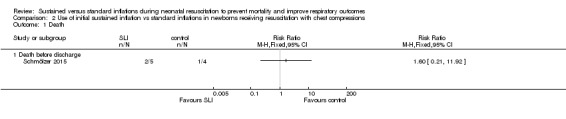

Death (Outcome 2.1)

Death in the delivery room (Outcome 2.1.1)

The included trial (N = 9) did not report this outcome (Schmölzer 2015).

Death during hospitalisation (Outcome 2.1.2)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 1.60, 95% CI 0.21 to 11.92; RD 0.15, 95% CI ‐0.45 to 0.75); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2015; Analysis 2.1). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schmölzer 2015).

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions, Outcome 1 Death.

Secondary outcomes

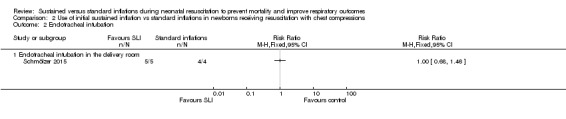

Endotracheal intubation in the delivery room (Outcome 2.2)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.46; RD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.34 to 0.34); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2015;Analysis 2.2). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schmölzer 2015).

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions, Outcome 2 Endotracheal intubation.

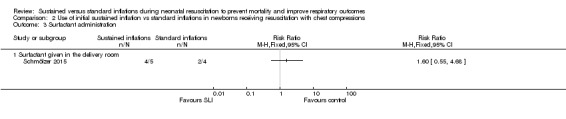

Surfactant administration in the delivery room (Outcome 2.3)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 1.60, 95% CI 0.55 to 4.68; RD 0.30, 95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.90); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2015; Analysis 2.3). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schmölzer 2015).

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions, Outcome 3 Surfactant administration.

Chronic lung disease (2.4, 2.5, 2.6)

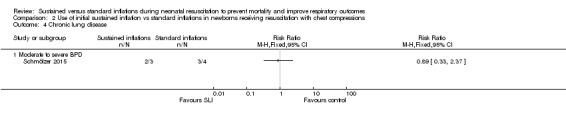

Moderate to severe BDP (Outcome 2.4)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.33 to 2.37; RD ‐0.08, 95% CI ‐0.76 to 0.60); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2015; Analysis 2.3). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schmölzer 2015).

Pneumothorax at any time (Outcome 2.5)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome: No events occurred (Analysis 2.5). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schmölzer 2015).

Analysis 2.5.

Comparison 2 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions, Outcome 5 Pneumothorax.

Cranial ultrasound abnormalities (Outcome 2.6)

Intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), grade 3 or 4 according to the Papile classification (Papile 1978) (Outcome 2.6.1)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.05 to 2.98; RD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐0.90 to 0.30); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2015; Analysis 2.6). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schmölzer 2015).

Analysis 2.6.

Comparison 2 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions, Outcome 6 Cranial ultrasound abnormalities.

IVH any grade (Outcome 2.6.2)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.07 to 1.15; RD ‐0.80, 95% CI ‐1.23 to ‐0.37); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2015; Analysis 2.6). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schmölzer 2015).

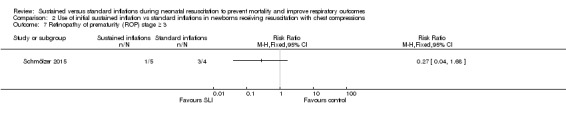

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) ≥ stage 3 (Outcome 2.7)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 0.27, 95% CI 0.04 to 1.68; RD ‐0.55, 95% CI ‐1.10 to 0.00); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2015; Analysis 2.7). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schmölzer 2015).

Analysis 2.7.

Comparison 2 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions, Outcome 7 Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) stage ≥ 3.

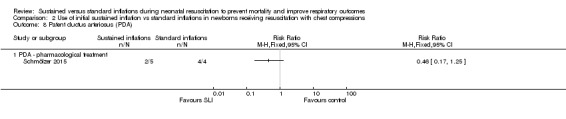

Rate of PDA ‐ pharmacological treatment (Outcome 2.8)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.25; RD ‐0.60, 95% CI ‐1.07 to ‐0.13); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2015; Analysis 2.8). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schmölzer 2015).

Analysis 2.8.

Comparison 2 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions, Outcome 8 Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA).

For the secondary comparison, investigators provided no data on other prespecified outcomes.

Subgroup analysis for the secondary comparison

For the secondary comparison, we were unable to conduct any subgroup analysis, as we included only one trial.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We evaluated the merits of sustained lung inflation (SLI) versus intermittent ventilation in infants requiring resuscitation and stabilisation at birth. Eight trials enrolling 941 preterm infants met review inclusion criteria (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schmölzer 2015; Schwaberger 2015). Whereas the two trials included in the previous version of this review enrolled infants at 25+0 to 28+6 weeks (Lindner 2005; Lista 2015), the five more recent trials enrolled larger infants (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015). One of the trials included in this update was not pooled with the other studies for analysis because investigators superimposed the intervention on chest compressions (Schmölzer 2015).

Sustained lung inflation was not better than intermittent ventilation for reducing mortality ‐ the primary outcome of this review. We rated the quality of evidence as moderate (GRADE) for death before discharge (limitations in study design of most included trials) and as low (GRADE) for death in the delivery room (limitations in study design and imprecision of estimates). When considering secondary outcomes, such as need for intubation, need for or duration of respiratory support, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, or pneumothorax, we found no benefit of SLI over intermittent ventilation. The quality of evidence for secondary outcomes was moderate (limitations in study design of most included trials ‐ GRADE), except for pneumothorax (low quality: limitations in study design and imprecision of estimates ‐ GRADE). Duration of mechanical ventilation was shorter in the SLI group (low quality: limitations in study design and imprecision of estimates ‐ GRADE). The first version of this review reported an increased rate of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) in the sustained lung inflation group. However, this effect was not seen when the most recent trials were added to the analysis. We identified six ongoing trials.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

To date, seven trials comparing sustained versus standard inflations for initial resuscitation have enrolled 941 newborns. Available data were insufficient for assessment of clinically important outcomes, which were identified a priori. Study authors did not report outcomes such as duration of supplemental oxygen requirement and long‐term neurodevelopmental outcomes and did not enrol term infants. We could not perform an a priori subgroup analysis (gestational age, ventilation device, interface, duration of sustained inflation) to detect differential effects because of the paucity of included trials. Relevant questions such as the following remain unanswered: What is the optimal duration for an SLI? Which level of positive end‐expiratory pressure (PEEP) should follow? Which is the optimal interface/device? (McCall 2016) We were able to summarise available evidence in a comprehensive way, as we obtained additional information about study design and outcome data from all included trials (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schmölzer 2015; Schwaberger 2015) and from two excluded trials (Harling 2005; te Pas 2007). The five ongoing trials that we identified reported important differences in choice of gestational age (NCT02139800; NCT02493920; NCT02846597; NCT02858583; NCT02887924). NCT02139800 enrols infants at 23 to 26 weeks, NCT02493920 at 25 to 36 weeks, NCT02887924 at 26 to 29 weeks, and NCT02846597 at < 33 weeks, whereas NCT02858583 enrols term and preterm infants. These differences among study populations might prove to be important, as trials have reported that sustained inflation was more effective in infants at 28 to 30 weeks than at < 28 or > 30 weeks of gestation (te Pas 2007).

Quality of the evidence

According to the GRADE approach, we rated the overall quality of evidence for clinically relevant outcomes as low to moderate (see Table 1). We downgraded the overall quality of evidence for critical outcomes because of limitations in study design (i.e. selection bias due to lack of allocation concealment) and imprecision of results (few events for death in the delivery room and wide confidence intervals for pneumothorax). In addition, two trials did not report sample size calculations (El‐Chimi 2017; Schwaberger 2015), and the other three did not achieve them (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005;Ngan 2017). Results of smaller studies are subject to greater sampling variation, and hence are less precise. Indeed, imprecision is reflected in the confidence interval around the intervention effect estimate from each study and in the weight given to the results of each study included in the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2011).

Potential biases in the review process

A major limitation of this Cochrane review is the definition of sustained lung inflation, as trials used different pressures, which may have impacted study results. No trials were blinded owing to the nature of the intervention. We excluded a potentially relevant trial (te Pas 2007) because sustained inflation was only one element of the intervention, and it is not possible to determine the relative contributions of various elements of this intervention to differences observed between groups. We excluded Harling 2005 because the control group received 2 seconds of inflation (5 seconds for the intervention group), whereas we defined sustained as > 1 second. For this update, we made a post hoc decision to add a comparison based on the presence of chest compressions during resuscitation.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Several systematic reviews of SLI have been recently published. Schmölzer 2014 conducted a systematic review of randomised clinical trials comparing SLI versus intermittent positive‐pressure ventilation (IPPV) as the primary respiratory intervention during respiratory support in preterm individuals at < 33 weeks of gestational age in the delivery room. This review included four trials, including two that we excluded from our systematic review (Harling 2005; te Pas 2007). Schmölzer 2014 reported a significant reduction in the need for mechanical ventilation within 72 hours after birth (typical risk ratio (RR) 0.87, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.74 to 1.03). As in our analysis, significantly more infants treated with SLI received treatment for PDA (RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.54). Results showed no differences in bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), death at latest follow‐up, or the combined outcome of death or BPD among survivors between groups. The findings of Schmölzer 2014 differ from the findings of this Cochrane review because of differences in the definition of duration of the intervention, and therefore in determination of included trials. A narrative review (Foglia 2016) including five trials (Harling 2005; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; te Pas 2007) concluded that at present, data are insufficient to support the use of SLI in clinical practice. An observational analytical cross‐sectional case–control study of 78 preterm infants showed that SLI resulted in lower rates of intubation in the delivery room, lower rates of invasive mechanical ventilation, and higher rates of intraventricular haemorrhage (Grasso 2015).

Authors' conclusions

Sustained lung inflation was not better than intermittent ventilation for reducing mortality in the delivery room (low‐quality evidence ‐ GRADE) and during hospitalisation (moderate‐quality evidence ‐ GRADE) ‐ primary outcomes of this review. When considering secondary outcomes, such as need for intubation, need for or duration of respiratory support, or bronchopulmonary dysplasia, we found no benefit of sustained inflation over intermittent ventilation (moderate‐quality evidence ‐ GRADE). Duration of mechanical ventilation was shortened in the SLI group (low‐quality evidence ‐ GRADE); however, this result should be interpreted cautiously, as it might have been influenced by study characteristics other than the intervention.

Additional studies of SLI for infants receiving respiratory support at birth should provide more detailed monitoring of the procedure, such as measurements of lung volume and presence of apnoea before or during SLI. Future randomised controlled trials should aim to enrol infants who are at higher risk of morbidity and mortality, and should stratify participants by gestational age. Researchers should also measure long‐term neurodevelopmental outcomes (e.g. Bayley Scales of Infant Development administered at two years of corrected age).

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Lindner, te Pas, Harling, El‐Farghali (for El‐Chimi 2017), Mercadante, Nuntnarumit (Jiravisitkul 2017), Schmolzer (for Ngan 2017 and Schmölzer 2015), and Schwaberger for their gracious assistance in providing extra data.

We acknowledge the help of Ms. Jennifer Spano and Ms. Colleen Ovelman in conducting literature searches for this update of the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Standard search method

PubMed: ((infant, newborn[MeSH] OR newborn OR neonate OR neonatal OR premature OR low birth weight OR VLBW OR LBW or infan* or neonat*) AND (randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized [tiab] OR placebo [tiab] OR drug therapy [sh] OR randomly [tiab] OR trial [tiab] OR groups [tiab]) NOT (animals [mh] NOT humans [mh]))

Embase: (infant, newborn or newborn or neonate or neonatal or premature or very low birth weight or low birth weight or VLBW or LBW or Newborn or infan* or neonat*) AND (human not animal) AND (randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial or randomized or placebo or clinical trials as topic or randomly or trial or clinical trial)

CINAHL: (infant, newborn OR newborn OR neonate OR neonatal OR premature OR low birth weight OR VLBW OR LBW or Newborn or infan* or neonat*) AND (randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial OR randomized OR placebo OR clinical trials as topic OR randomly OR trial OR PT clinical trial)

Cochrane Library: (infant or newborn or neonate or neonatal or premature or preterm or very low birth weight or low birth weight or VLBW or LBW)

Appendix 2. Risk of bias tool