Abstract

Background

Clinical practice does not always reflect best practice and evidence, partly because of unconscious acts of omission, information overload, or inaccessible information. Reminders may help clinicians overcome these problems by prompting them to recall information that they already know or would be expected to know and by providing information or guidance in a more accessible and relevant format, at a particularly appropriate time. This is an update of a previously published review.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of reminders automatically generated through a computerized system (computer‐generated) and delivered on paper to healthcare professionals on quality of care (outcomes related to healthcare professionals' practice) and patient outcomes (outcomes related to patients' health condition).

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, six other databases and two trials registers up to 21 September 2016 together with reference checking, citation searching and contact with study authors to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included individual‐ or cluster‐randomized and non‐randomized trials that evaluated the impact of computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals, alone (single‐component intervention) or in addition to one or more co‐interventions (multi‐component intervention), compared with usual care or the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component.

Data collection and analysis

Review authors working in pairs independently screened studies for eligibility and abstracted data. For each study, we extracted the primary outcome when it was defined or calculated the median effect size across all reported outcomes. We then calculated the median improvement and interquartile range (IQR) across included studies using the primary outcome or median outcome as representative outcome. We assessed the certainty of the evidence according to the GRADE approach.

Main results

We identified 35 studies (30 randomized trials and five non‐randomized trials) and analyzed 34 studies (40 comparisons). Twenty‐nine studies took place in the USA and six studies took place in Canada, France, Israel, and Kenya. All studies except two took place in outpatient care. Reminders were aimed at enhancing compliance with preventive guidelines (e.g. cancer screening tests, vaccination) in half the studies and at enhancing compliance with disease management guidelines for acute or chronic conditions (e.g. annual follow‐ups, laboratory tests, medication adjustment, counseling) in the other half.

Computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals, alone or in addition to co‐intervention(s), probably improves quality of care slightly compared with usual care or the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component (median improvement 6.8% (IQR: 3.8% to 17.5%); 34 studies (40 comparisons); moderate‐certainty evidence).

Computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals alone (single‐component intervention) probably improves quality of care compared with usual care (median improvement 11.0% (IQR 5.4% to 20.0%); 27 studies (27 comparisons); moderate‐certainty evidence). Adding computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals to one or more co‐interventions (multi‐component intervention) probably improves quality of care slightly compared with the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component (median improvement 4.0% (IQR 3.0% to 6.0%); 11 studies (13 comparisons); moderate‐certainty evidence).

We are uncertain whether reminders, alone or in addition to co‐intervention(s), improve patient outcomes as the certainty of the evidence is very low (n = 6 studies (seven comparisons)). None of the included studies reported outcomes related to harms or adverse effects of the intervention.

Authors' conclusions

There is moderate‐certainty evidence that computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals probably slightly improves quality of care, in terms of compliance with preventive guidelines and compliance with disease management guidelines. It is uncertain whether reminders improve patient outcomes because the certainty of the evidence is very low. The heterogeneity of the reminder interventions included in this review also suggests that reminders can probably improve quality of care in various settings under various conditions.

Plain language summary

The effect of automatically generated reminders delivered to providers on paper on quality of care and patient outcomes

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane review was to find out if reminders, automatically generated through a computer, but delivered on paper to doctors help them provide the best recommended care. Cochrane researchers identified 35 studies and analyzed 34 of these studies to answer this question.

Key messages

Providing reminders to doctors probably improves slightly the quality of care patients receive. However, because the certainty of the evidence is moderate, more high‐quality studies on the effectiveness of reminders are needed to confirm to findings of this review.

What was studied in the review?

Doctors do not always provide care that is recommended or that reflects the latest research, partly because of too much information or inaccessible information. Reminders may help doctors overcome these problems by reminding them about guidelines and research findings, or by providing advice, in a more accessible and relevant format, at a particularly appropriate time. For example, when a doctor sees a patient for an annual check‐up, the doctor would receive the patient's chart with a reminder section listing the screening tests due that year, such as colorectal cancer screening. In this review, we evaluated the effects of reminders on the quality of care delivered by physicians, on patient outcomes, and on adverse effects. These reminders were automatically generated through a computer system but delivered on paper.

What are the main results of the review?

Twenty‐nine studies were from the USA and six studies were from Canada, France, Israel and Kenya. The studies examined reminders to doctors to order screening tests, to provide vaccinations, to prescribe specific medications, or to discuss care with patients.

The review shows that:

‐ overall, reminders probably improve slightly quality of care by 6.8% (in 34 studies (40 comparisons), moderate‐certainty evidence);

‐ reminders alone (single‐component intervention) probably improve quality of care by 11.0% compared with usual care (in 27 studies (27 comparisons), moderate‐certainty evidence);

‐ adding reminders to one or more co‐interventions (multi‐component intervention) probably improve slightly quality of care by 4.0% compared with the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component (in 11 studies (13 comparisons), moderate‐certainty evidence);

‐ it is uncertain whether reminders improve patient outcomes because the certainty of the evidence is very low;

‐ none of the included studies reported outcomes related to harms or adverse effects.

How up to date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies that had been published up to 21 September 2016.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals, alone or in addition to co‐intervention(s), compared with usual care or the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component | ||||

|

Patient or population: Healthcare professionals Settings: Outpatient care in Canada, France, Israel, Kenya and USA Intervention: Reminders automatically generated through a computerized system (computer‐generated) and delivered on paper to healthcare professionals, alone or in addition to one or more co‐interventions, aimed at enhancing compliance with preventive guidelines (e.g. cancer screening tests, vaccination) or disease management guidelines for acute or chronic conditions (e.g. annual follow‐ups, laboratory tests, medication adjustment, counseling) Comparison: Usual care or co‐intervention(s) without reminder component | ||||

| Outcomes | Median improvement | Number of studies (comparisons) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Quality of care | Pooling data across the 40 comparisons, the median improvement in quality of care associated with the reminder intervention was 6.8% (IQR 3.8% to 17.5%). | 34 studies (40 comparisons) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | Quality of care was measured by various rates: e.g. test ordering rates, vaccination rates, follow‐up rates, prescription rates, overall compliance rate. |

| Patient outcomes | Not estimable | 6 studies (7 comparisons) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 | No measurable effect on i) blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin and cholesterol levels, ii) reaching blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin and cholesterol targets, and iii) mortality. |

| Adverse effects | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported outcomes related to harms or adverse effects of reminders. |

| IQR: interquartile range | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

1 We downgraded the level of certainty of the evidence from high to moderate because of methodological limitations in the included studies and possible publication bias. We did not find other serious limitations in the other factors (indirectness of evidence, inconsistency of results, and imprecision of results).

2 We downgraded the level of certainty of the evidence from high to very low because of methodological limitations in the included studies, imprecision of results (wide confidence intervals) and inconsistency of the results.

2.

| Computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals alone (single‐component intervention) compared with usual care | ||||

|

Patient or population: Healthcare professionals Settings: Outpatient care in Canada, France, Israel, Kenya and USA Intervention: Computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper alone (single‐component intervention) Comparison: Usual care | ||||

| Outcomes | Median improvement | Number of studies (comparisons) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Quality of care | Pooling data across the 27 comparisons, the median improvement in quality of care associated with the reminder intervention was 11.0% (IQR 5.4% to 20.0%) |

27 studies (27 comparisons) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | Quality of care was measured by various rates: e.g. test ordering rates, vaccination rates, follow‐up rates, prescription rates, overall compliance rate. |

| Patient outcomes | Not estimable | 4 studies (4 comparisons ) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 | No measurable effect on i) blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin and cholesterol levels, ii) reaching blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin and cholesterol targets, and iii) mortality. |

| Adverse effects | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported outcomes related to harms or adverse effects of reminders. |

| IQR: interquartile range | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

1 We downgraded the level of certainty of the evidence from high to moderate because of methodological limitations in the included studies and possible publication bias. We did not find other serious limitations in the other factors (indirectness of evidence, inconsistency of results, and imprecision of results).

2 We downgraded the level of certainty of the evidence from high to very low because of methodological limitations in the included studies, imprecision of results (wide confidence intervals) and inconsistency of the results.

3.

| Computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals in addition to one or more co‐interventions (multi‐component intervention) compared with the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component | ||||

|

Patient or population: Healthcare professionals Settings: Outpatient care in Canada and USA Intervention: Computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper in addition to one or more co‐interventions (multi‐component intervention) Comparison: Co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component | ||||

| Outcomes |

Median improvement (interquartile range) |

Number of studies (comparisons) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Quality of care | Pooling data across the 13 comparisons, the median improvement in quality of care associated with the reminder intervention was 4.0% (3.0% to 6.0%) | 11 studies (13 comparisons) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | Quality of care was measured by various rates: e.g. test ordering rates, vaccination rates, follow‐up rates, prescription rates, overall compliance rate. |

| Patient outcomes | Not estimable | 2 studies (3 comparisons) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 | No measurable effect on i) blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin and cholesterol levels, ii) reaching blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin and cholesterol targets, and iii) mortality. |

| Adverse effects | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported outcomes related to harms or adverse effects of reminders. |

| IQR: interquartile range | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

1 We downgraded the level of certainty of the evidence from high to moderate because of methodological limitations in the included studies and possible publication bias. We did not find other serious limitations in the other factors (indirectness of evidence, inconsistency of results, and imprecision of results).

2 We downgraded the level of certainty of the evidence from high to very low because of methodological limitations in the included studies and imprecision of results (wide confidence intervals).

Background

Description of the condition

Clinical practice does not always reflect best evidence, partly because of unconscious acts of omission, information overload or inaccessible information (McDonald 1976). A number of recent studies suggest that fragmented and inaccessible clinical information adversely affects both the cost and quality of health care as well as compromising patient safety (e.g. Anderson 2007). Healthcare professionals are constantly confronted with multiple clinical decisions to be made about diagnosing, treating, and counseling, in various settings. In addition, physicians are increasingly expected to perform tasks related to health maintenance and preventive care that are not directly related to the patient's acute problem, such as cancer screening and chronic disease management. Because the vast amount of information that is needed to achieve appropriate decisions, various support systems have been developed to convey the proper information at the right place and time. A number of interventions have been designed to reduce omissions and the gap between best practice and routine care: educational interventions (directed at clinicians or patients), clinical practice guidelines, reminders (directed at clinicians or patients), audit and feedback of clinical performance, financial incentives, local opinion leaders, information and communication technologies (e‐health) and organizational changes. Previous reviews have shown that such interventions may have the potential to foster better knowledge translation; however the effects are most often modest on average, have shown large variations in practice and are most frequently based on weak quality of evidence (e.g. Baker, 2015; Fiander 2015; Flodgren 2011; Forsetlund 2009; Gagnon 2009; Giguère 2012; Grimshaw 2004; Ivers 2012; Morris 2002; Shojania 2009; Thomas 1999).

Description of the intervention

According to the US National Library of Medicine, "reminder systems" are approaches, techniques or procedures "used to prompt or aid the memory" of healthcare professionals. "The systems can be computerized reminders, colour coding, telephone calls, or devices such as letters and postcards." (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) Reminders have been used for many years and in many different forms. Reminders can be generated electronically or manually, and can be delivered on the computer screen, via email or fax, or in patient paper charts. They also vary in format (e.g. flow chart, electronic message, checklist, sticker) and content (e.g. suggested test date, reference to literature, preventive care suggestions). They can be completely automated and computerized, such as an alert system embedded into computerized provider order entry systems, or completely paper‐based without any involvement of a computer, such as simple notes attached by nursing personnel to the front of charts. A third type of reminder, computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper, combines the two previous approaches. These are automatically generated through a computerized system, but are delivered on paper to the healthcare professional, usually along with the paper‐based medical record, but potentially as a letter they receive outside the consultation.

How the intervention might work

Reminder systems help clinicians overcome barriers to knowledge transfer, remind them to perform tests or interventions that should be performed regularly, e.g. regular foot examination in diabetic patients or yearly influenza vaccine in elderly patients. Indeed, reminders systems prompt clinicians to recall information that they already know or would be expected to know and by providing information or guidance in a more accessible and relevant format, at a particularly appropriate time. Studies and systematic reviews have indicated that reminders to healthcare professionals can be effective in promoting change in healthcare professional practice across a variety of clinical areas and settings (Balas 2000; Buntinx 1993; Kawamoto 2005; Mandelblatt 1995; Shea 1996; Wensing 1994). Reminder systems have been used to target provider behavior across a range of clinical circumstances including preventive, acute and chronic care and to target various behaviors, such as test ordering, vaccination, drug selection, dosing and prescribing, and improving general disease management.

Why it is important to do this review

Previous comprehensive and systematic reviews have covered reminders as one of a wide range of interventions aimed at improving professional practice (Davis 1992; Davis 1995; Garg 2005; Grimshaw 2004; Hunt 1998; Johnston 1994;Oxman 1995), or have focused on computerized reminders (Schedlbauer 2009) or the effectiveness of reminders for a specific behavior, such as preventive care (Balas 2000; Dexheimer 2008; Shea 1996), cancer screening (Baron 2010), vaccination (Ndiaye 2005), diabetes care (Balas 2004), or prescribing practices (Bennett 2003; Pearson 2009). In addition, factors that may modify the effectiveness of reminders have not been systematically considered. For example, specific suggestions or advice have been used by several reviews (Axt‐Adam 1993; Buntinx 1993; Haynes 1987) to distinguish between types of reminder, but few conclusions have been drawn about their impact on the effectiveness of reminders. This may reflect the difficulty of distinguishing explicit advice from implicit advice in many reports of reminder studies. In our view and based on the literature, the effectiveness of reminders may be influenced by their content: whether they provide generic or patient‐specific information; whether they require the healthcare professional to record a response; whether they provide a recommendation for care and not just an assessment; whether they include an explanation or justification of the decision support; whether they are explicitly from, or justified by reference to an influential source; and whether reminders are available at point‐of‐care (Kawamoto 2005; Litzelman 1993). Another potential effect modifier may be the type of targeted behavior. Finally, reminders may also prove useful in low‐ and middle‐income countries; due to a shortage of healthcare workers, support and reminder systems may help volunteer or community health workers to contribute to appropriate care delivery (Mahmud 2010; Tierney 2007). Moreover, a systematic review aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of interventions targeting the transfer of evidence‐based information into practice in developing countries did not find conclusive evidence (Siddiqi 2005).

This review is one of a series covering three major categories of reminder and a fourth that will compare all of these. As well as carrying major resource implications, these categories may influence reminder effectiveness.

Manual paper reminders: no computer is involved in the production or delivery of the reminder, nor in selecting target patients (Pantoja 2014).

Computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper: a computer is used either to generate paper reminders or to identify patients for whom clinicians should receive a paper reminder.

On‐screen reminders: reminders are delivered to clinicians on computer screen (Shojania 2009).

The primary objective of the series is to guide the development and use of clinical reminder systems. When implementing a reminder system, the decision to use manual methods or a computer to produce or deliver reminders has major resource implications as well as usability implications. Although more and more providers adopt electronic medical records (EMR), their comprehensiveness varies and their widespread use is still limited. In 2001 only 29% of primary care physicians in the European Union had implemented electronic medical records, while in the USA less than 17% of primary care physicians routinely use EMRs in their practices (Anderson 2007). Another recent study found that, depending on the definition used, between 8% and 12% of U.S. hospitals have a basic electronic‐records system (Jha 2009). Using a computer to carry out case finding and to generate paper reminders combines the benefits of the speed and accuracy of computers, compared with manual selection of cases by a person, and the low technology paper delivery method that continues to dominate much clinical practice worldwide.

Objectives

In this review, we examined the effects of reminders automatically generated through a computerized system (computer‐generated) and delivered on paper to healthcare professionals on quality of care (outcomes related to healthcare professionals' practice) and patient outcomes (outcomes related to patients' health condition). We addressed the following primary question and subsidiary questions.

Are computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals effective in improving quality of care and patient outcomes?

Are computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals alone (single‐component intervention) more effective than usual care?

Are computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals in addition to one or more co‐interventions (multi‐component intervention) more effective than the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component?

We also addressed the following secondary questions, to identify factors that may systematically modify the effectiveness of reminders, based on features that have been suggested to be effect modifiers in the literature (Baron 2010; Dexheimer 2008; Kawamoto 2005; Litzelman 1993; Mollon 2009; Shiffman 1999).

Content of reminder

Are reminders that include some individual patient‐specific information more effective than generic reminders (i.e. same message for all patients)?

Are reminders that include space for a response from the clinician more effective than reminders that do not include this?

Are reminders that offer specific advice on patient management (i.e. recommendation for care) more effective than reminders that offer general information only (e.g. prevalence of a disease)?

Are reminders that include an explanation of their content or advice (e.g. background information, risk definition) more effective than reminders that do not include this?

Are reminders that are explicitly from, or justified by reference to an influential source more effective than anonymous reminders or those from another source? An influential source can be a systematic review, a practice guideline, a bibliographic citation, or a person or body likely to be perceived as credible by the target clinician.

Delivery of reminder

Are reminders available at point‐of‐care (i.e. at patient's visit) more effective than reminders available at another time (e.g. mailed reminders received after patient's visit)?

Behavior targeted by reminder

Do reminders vary in effectiveness according to the targeted behavior (e.g. test ordering, prescription)?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included trials where individuals (patients or providers) or other units (e.g. practice, hospital) were definitely or possibly assigned prospectively by the investigators to one of two (or more) alternative forms of health care using random allocation (randomized trial) or non‐random method of allocation (non‐randomized trial) such as alternation, date of birth or medical record number, according to EPOC guidance on study designs (EPOC 2015b). We included non‐randomized trials because in complex interventions that are evaluated in routine practice, conducting a randomized trial may be neither feasible nor acceptable. Non‐randomized trial designs can be better suited for real‐life situations and may better reflect the effectiveness of the intervention.

Types of participants

Any qualified healthcare professional, or a population where qualified healthcare professionals form the majority of the study population.

Types of interventions

Reminders are patient‐ or encounter‐specific information, which are designed or intended to prompt a healthcare professional to recall information usually encountered through their general medical education, in the medical records or through interaction with peers, and to remind them to perform or avoid some action to aid individual patient care. Reminders differ from feedback interventions in terms of content: feedback consists of a summary of clinical performance over a specified period of time, and typically aggregates information on multiple patients. Reminders also must not contain any new information about the patient such as a laboratory result that is not in the case notes or a score derived from a clinical prediction rule that was previously unknown to the clinician.

This review considered computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper. A computer had to be involved in producing the reminder for eligible patients or in selecting the patients about whom the clinician received a reminder, or both. If a computer was merely used as a medium to print the reminder without any other function, the reminder was not considered as computer‐generated. We also included applications of computerized algorithms to identify eligible patients, for whom the prompt is printed out and placed in the chart. Information was usually obtained from computerized medical records or a computerized database. Once generated, the reminder had to be delivered on paper (fax included), and not on a computer screen or via email or text message.

To be included in the review, the reminder had to target a healthcare professional who delivered the care directly to patients, not an intermediary (e.g. clinic receptionist, clinician manager). Expert systems for facilitating diagnosis or estimating prognosis were not considered as reminders, even if their output was printed out. A document listing all the drugs a patient was currently taking (e.g. drug profile) or a document summarizing the medical records, with no rules applied in the computer, were not considered as reminders, but as an organizational intervention (i.e. changes in the medical records systems). New clinical information collected directly from patients on a computer and given to the provider as a prompt was not considered as a reminder intervention, but as a patient‐mediated intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Quality of care is the primary outcome of this review as the main purpose of reminders is to change healthcare professional practice and affect a quality of care endpoint, such as ordering a test or initiating a treatment. This targeted practice change should, in turn, improve patient outcomes, based on evidence. Thus, if the reminder is aimed at modifying a drug prescription for a simpler or cheaper treatment, the latter prescription should have been shown as having at least similar effectiveness as the current treatment (indirect evidence). Studies of reminders rarely target changes in patient outcomes directly. Moreover, the targeted modification may not be linked to an actual change in patient outcome, for instance when replacing a proprietary drug by a generic equivalent.

Primary outcomes

Quality of care

Dichotomous outcomes related to healthcare professionals' practice: the percentage of patients receiving a target process of care (e.g. ordering of a test, prescription for a medication) or whose care was in compliance with an overall guideline (e.g. percentage of women up‐to‐date with a breast cancer screening recommendation). Instead of patients in the denominator, this could be patient encounters or reminders (e.g. number of recommendations followed over the number of recommendations due during an encounter).

Continuous outcomes related to healthcare professionals' practice: any continuous measure of how providers delivered care (e.g. duration of therapy, time to event).

Secondary outcomes

Patient outcomes

Dichotomous outcomes related to patients' health condition: the percentage of clinical endpoints (e.g. death, development of a disease such as pneumonia, stroke, heart attack, etc.) or the percentage of surrogate or intermediate endpoints, such as a continuous measures of disease control that have been dichotomized and reported as percentage of patients with sufficient or insufficient control (e.g. percentage of diabetics reaching the glycated hemoglobin target (< 7%), percentage of patients reaching systolic blood pressure target (< 140 mmHg)).

Continuous outcomes related to patients' health condition: various markers of disease or health status (e.g. blood pressure, body mass index, glycated hemoglobin levels) that were captured and analyzed as continuous variables.

Adverse effects outcomes: any adverse effects described in the study, such as redundant testing or overdiagnosis.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Information Specialist for the EPOC Group conducted the searches on 21 September 2016; exact search dates, search terms, syntax and number of results are provided for each database and may be found in Appendix 1. Previous searches can be found in the previous version of the review (Arditi 2012).

We searched the following databases.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 8) in the Cochrane Library

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; 2016, Issue 9) in the Cochrane Library

Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA; 2016, Issue 3) in the Cochrane Library

Database of Abstract of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE; 2015, Issue 2) in the Cochrane Library

NHS Economic Evaluations Database (NHSEED; 2015, Issue 2) in the Cochrane Library

MEDLINE via OVID (from 1946)

Embase via OVID (from 1974)

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) via Ebscohost (from 1980)

INSPEC via Web of Science(from 1969)

Searching other resources

In addition to database searching, we examined reference lists of key articles and relevant reviews, handsearched the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/), the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Trials Registry (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) and contacted authors of relevant reviews and studies regarding any further published or unpublished work.

Data collection and analysis

For this update, we used the same data collection tool defined in the protocol and used in the previous version of this systematic review (Arditi 2012).

Selection of studies

Two assessors (JW, SY), working independently, screened titles and abstracts of references located by the literature search for potential relevance. We retrieved full‐text copies of all potentially relevant studies for full‐text assessment. Many studies were rated as potentially relevant in the first selection process, as it was often unclear whether computerized reminders were provided to the healthcare professional on paper or on a computer screen, and whether the reminders were computer‐generated. Two assessors, again working in pairs (CA, SY), independently assessed studies for inclusion. Studies that appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but on closer examination failed to, are detailed in the table of excluded studies.

Data extraction and management

Two assessors independently carried out data extraction (SY, CA), using the EPOC Data Collection Checklist modified to capture more detailed information in some areas (e.g. content of the reminder). Any discrepancies between assessors arising from the inclusion assessment or from the data extraction process were resolved by discussion and the involvement of a third review author. Decisions that could not be resolved easily were referred to the EPOC contact editor.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias for all included studies was independently assessed in pairs (SY, CA) using the nine suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews (EPOC 2015a).

Measures of treatment effect

For each study we reported the main results in natural units in a results table. Where baseline results were available, pre‐intervention proportions and means were also reported for both study and control groups. The unadjusted and adjusted (for baseline imbalance) differences (in proportion or mean) between study and control groups at endpoint were calculated for the outcomes. The direction of the effect size was standardized so that a positive difference between post‐intervention percentages or means indicated a positive outcome.

Unit of analysis issues

We anticipated that cluster‐randomized trials would be common, which is often the case in interventions aimed at healthcare professionals. There is a high risk of contamination when patients are randomized rather than professionals since clinicians’ experience of applying the intervention to patients receiving the experimental management may contaminate the way they treat control patients (Biau 2008; Kahan 2013). We also expected that such trials would rarely take into account the cluster effect in the analysis (i.e. unit of analysis error resulting in artificially extreme P values and over narrow confidence intervals (Ukoumunne 1999). Performing a meta‐analysis involving both trials randomizing patients and clusters would require us to make assumptions about unknown parameters, such as intra‐class correlation coefficients and the distribution of patients across clusters, to avoid spurious precision in 95% confidence intervals. In addition, we expected a large variety of interventions, outcomes and response scales, as well as a very wide contextual and clinical heterogeneity in existing studies’ reports. We thus decided to report the median improvement and interquartile range (IQR) across the included studies in order to avoid unit of analysis issues when combining results from cluster‐ and patient‐randomized trials.

Dealing with missing data

No data were missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We explored heterogeneity visually by preparing box plots displaying median effects and IQRs (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity for further details).

Assessment of reporting biases

We explored the possibility of publication bias by plotting the number of patients and professionals included in the studies against the median effect size.

Data synthesis

We combined cluster‐ and patient‐randomized trials using the median improvement and IQR. This approach was first developed in a large review of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies (Grimshaw 2004) and used in the systematic review on the effects of on‐screen, point‐of‐care reminders (Shojania 2009). Briefly, each study is represented by a single representative outcome and the median effect size and IQR are calculated across the included studies. By using the median rather than the mean, the summary estimate is less likely to be influenced by outlying results (e.g. large effects from methodologically poor studies). In contrast to conventional meta‐analysis, where each study is given a weight based on the precision of the results, here each study is given equal weight. The impact of study size and various methodological features were investigated in pre‐specified subgroup analyses.

The representative outcome of studies reporting more than one outcome was the primary outcome measure when it was defined as such by the authors of the study. If authors did not specify the primary outcome but provided an aggregated outcome (e.g. overall physician compliance), we selected that aggregated outcome as a representative outcome. If a primary outcome was not available, we calculated the median effect size across all reported outcomes. For example, if the study reported five dichotomous quality of care outcomes and none of them were denoted the primary outcome, we ranked the effect sizes for the five quality of care outcomes and took the median value. If there was an even number of outcomes, we calculated the average of the two middle outcomes.

Summary of findings

We summarized the findings in three 'Summary of findings' tables to draw conclusions about the certainty of the evidence. Two review authors (BB, CA) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence (high, moderate, low, and very low) using the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) (Guyatt 2011). We used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), the EPOC worksheets (EPOC 2015c), and by using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT 2015). We resolved disagreements on certainty ratings by discussion and provided justification for decisions to down‐ or up‐grade the ratings using footnotes in the tables and made comments to aid readers' understanding of the review where necessary. We used plain language statements to report these findings throughout the review.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We compared the median improvement across studies according to the following potential effect modifiers, pre‐defined in the protocol and based on features that have been suggested to be effect modifiers in the literature (Baron 2010; Dexheimer 2008; Kawamoto 2005; Litzelman 1993; Mollon 2009; Shiffman 1999):

patient‐specific: whether the reminder provided generic knowledge or advice with no patient data or patient‐specific advice (i.e. same message or advice for all patients) or patient‐specific knowledge or advice;

space for response: whether the reminder provided space for the healthcare professional to record a response/comment (e.g. a box to tick or line to write on) or not;

specific advice: whether the reminder provided advice on patient management or recommendation for care (e.g. consider reducing dosage of drug) or not (e.g. prevalence of disease);

explanation: whether the reminder was supported by an explanation (e.g. background information, definitions, risks, rationale) or not (e.g. last pap smear test date);

reference: reminders were explicitly from or justified by reference to an influential source (e.g. clear reference to a systematic review or national guidelines) or not;

at point‐of‐care: whether the reminder was delivered to healthcare professional when providing care to the patient (at point‐of‐care) or not (e.g. reminder sent by mail after patient's visit).

We also compared the median improvement across studies according to the type of behavior targeted by the reminder (e.g. prescription, test ordering) and the following features of the study: study design, allocation method, sample size (patients and professionals), setting, country, duration of intervention, and publication year. We also investigated the median improvement in disadvantaged populations, in terms of economic status, place of residence and ethnicity.

We used the non‐parametric Wilcoxon rank‐sum test (also known as the Mann‐Whitney two‐sample statistic) for two‐levels variables and the Kruskal‐Wallis test for variables with more than two levels. We performed all statistical analyses using Stata version 10 (Stata 2007).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses based on study design criteria deemed important in the context of this review (only including studies with allocation concealment and complete outcome data) and data availability (excluding trials where data were estimated from graphs). We also re‐analyzed the data using three alternative methods for representing the outcome from each study: using the median outcome as representative outcome, even for studies reporting a primary outcome; using the reported outcome showing the largest improvement (largest outcome); and using the reported outcome showing the smallest improvement (smallest outcome).

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

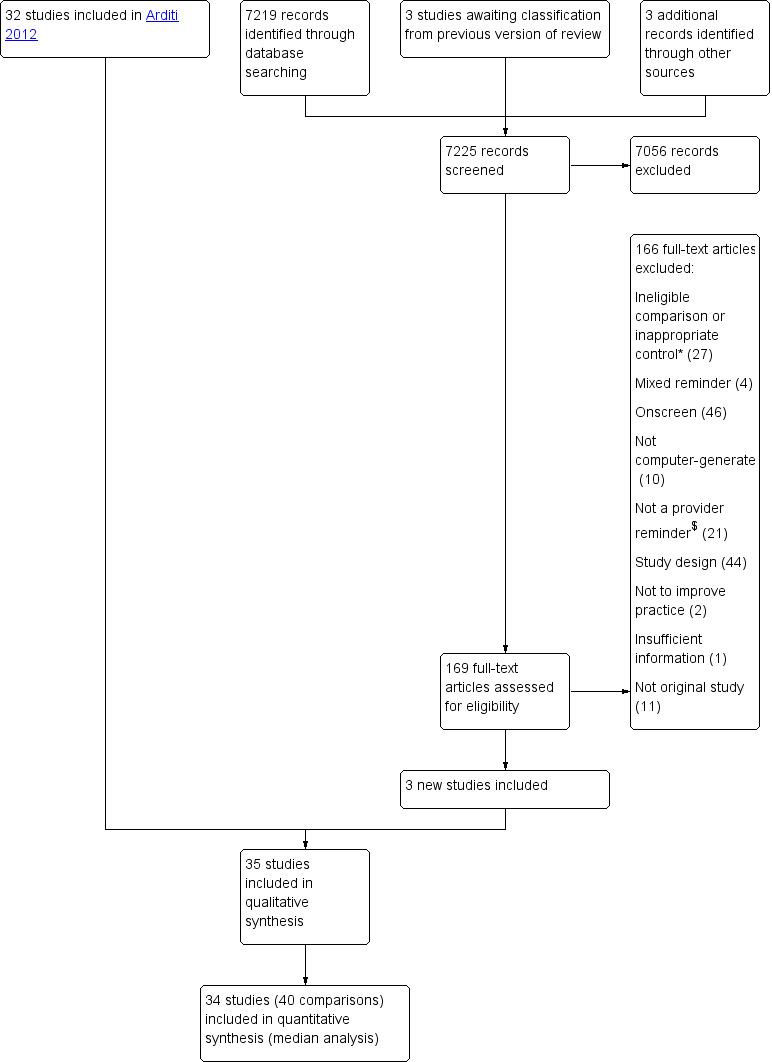

See: Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram

*Ineligible comparison or inappropriate control: e.g. physician reminder combined with another intervention vs usual care, physician reminder with a specific feature vs physician reminder without it, physician reminder vs another intervention

$Not a provider reminder: e.g. audit and feedback, changes in medical records system, expert system for estimating diagnosis/risk/dosage, patient‐mediated intervention

We identified 7225 records (including three studies awaiting classification in the original review and three studies identified via handsearching), of which 7056 were excluded after screening the title and abstract. After assessing full‐texts for the remaining 169 records, we retained three new studies (Gilutz 2009; Le Breton 2016; Were 2013). In total, we included 35 studies in the qualitative synthesis and 34 studies in the quantitative synthesis (one study did not report usable outcome data). Six studies (Burack 1996; Burack 1998; McPhee 1989; Ornstein 1991; Tierney 1986; Ziemer 2006) contained four study groups (i.e. reminders alone, reminders with co‐intervention(s), co‐intervention(s) without reminder component, usual care), resulting in 40 eligible comparisons in the quantitative analyses.

Included studies

Design

Thirty studies were randomized trials, including one cross‐over trial (McDonald 1980), and five studies were non‐randomized trials (Mazzuca 1990; McDonald 1976a; Morgan 1978; Oniki 2003; Turner 1989), including one cross‐over trial (McDonald 1976a). Among the 35 included studies, 15 allocated patients to study groups (Barnett 1983; Becker 1989; Binstock 1997; Burack 1996; Burack 1998; Chambers 1989; Heidenreich 2005; Heidenreich 2007; Javitt 2005; McDonald 1976b; Morgan 1978; Oniki 2003; Thomas 1983; Were 2013; White 1984), while the other studies used cluster‐allocation methods. The unit of allocation was the health professional in 10 studies (Chambers 1991; Le Breton 2016; Lobach 1997; Majumdar 2007; McAlister 2009; McDonald 1976a; McDonald 1980; McPhee 1989; Nilasena 1995; Rossi 1997), the clinic, clinic session or health professional team in nine studies (Dexter 1998; Gilutz 2009; Heiman 2004; Mazzuca 1990; McDonald 1984; Ornstein 1991; Tierney 1986; Turner 1989; Ziemer 2006), and the family in one study (Rosser 1991).

Participants, setting and publication date

All studies included at least 100 patients in the analyses (median 751, mean 2275); the number of patients was not reported in two studies (Javitt 2005; McDonald 1980). The healthcare professionals were primarily physicians, although some studies also included other professionals such as nurse practitioners. One study included only nurses (Oniki 2003). Healthcare professionals' level of training varied across studies. In the cluster‐randomized studies, the number of professionals, for whom outcome data were obtained, varied between nine and 600 (median 57, mean 104).

Most included studies were based in North America (29 in the USA, three in Canada). The three remaining studies were based in France (Le Breton 2016), Israel (Gilutz 2009), and Kenya (Were 2013). Most studies took place in outpatient settings, while two took place in inpatient settings (Oniki 2003; White 1984) and three in mixed settings (Heidenreich 2005; Heidenreich 2007; Javitt 2005).

About 70% of the studies were published between 1980 and 2000.

Interventions

Physician reminders alone (single‐component intervention) were compared with usual care in 28 studies (Barnett 1983; Becker 1989; Binstock 1997; Burack 1996; Burack 1998; Chambers 1989; Chambers 1991; Dexter 1998; Gilutz 2009; Heidenreich 2005; Heidenreich 2007; Heiman 2004; Javitt 2005; Le Breton 2016; Lobach 1997; McDonald 1976a; McDonald 1976b; McDonald 1980; McDonald 1984; McPhee 1989; Morgan 1978; Oniki 2003; Rosser 1991; Rossi 1997; Thomas 1983; Tierney 1986; Were 2013; White 1984). Physician reminders in addition to one or more co‐interventions (multi‐component intervention) were compared with the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component in 11 studies. There was one co‐intervention in seven studies (Burack 1996; Burack 1998; Majumdar 2007; Mazzuca 1990; McAlister 2009; Nilasena 1995; Tierney 1986), two co‐interventions in four studies (McPhee 1989; Ornstein 1991; Turner 1989; Ziemer 2006), and three co‐interventions in study groups of two studies (Ornstein 1991; Ziemer 2006). The most common co‐interventions were patient reminder, educational meeting for healthcare professionals, and audit and feedback.

The same reminder was provided for all eligible patients (e.g. order a pap smear test) in 15 comparisons. Between two and 10 different reminders could be provided for patients in 19 studies, while over 10 different reminders could be provided for eligible patients in the remaining seven comparisons (McDonald 1980; McDonald 1984; Nilasena 1995; Thomas 1983; Tierney 1986; Tierney 1986; Were 2013).

The categorization of reminders for each included study is provided in the Characteristics of included studies tables. Reminders in all comparisons except one (Chambers 1991) were patient‐specific. The use of the computer to select patients allowed the reminders to be sent to eligible patient records only and thus be patient‐specific. Reminders in 19 comparisons included space for the provider to respond to the reminder (e.g. a check box to order a mammogram). Reminders offered specific advice on patient management (i.e. recommendation for care) in 35 comparisons and included an explanation of their content or advice (e.g. background information, risk definition) in 13 comparisons. Reminders were explicitly from or justified by reference to an influential source (e.g. systematic review, bibliographic citation) in 11 comparisons. Reminders were provided to physicians at the point‐of‐care (i.e. during the patient's visit) in all comparisons except five, where reminders were sent after patients' visits directly to physicians.

The median duration of the reminder intervention was 11 months (range two to 56 months); the duration was not reported in two studies (Binstock 1997; Dexter 1998).

Clinical domain and targeted behavior

Reminders were aimed at prompting the physicians to provide preventive care services in half of the comparisons. In these studies, the most common objective was to enhance compliance with cancer screening tests (e.g. mammography, Papanicolaou smear, rectal examination) or vaccination. In the remaining comparisons, reminders were provided to physicians seeing patients with an acute or chronic condition, such as diabetes, HIV and cardiovascular disease, to enhance compliance with disease management guidelines (e.g. foot examination in diabetes patients, blood pressure check in hypertensive patients, prescribing angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors in patients with cardiovascular problems).

In 23 comparisons, reminders targeted one type of behavior. The behavior was test ordering (e.g. mammography, glycated hemoglobin) in 10 comparisons, vaccination in one comparison, prescribing in seven comparisons, professional‐patient communication in two comparisons, and general management in three comparisons. In the remaining 17 comparisons, reminders targeted multiple behaviors: two types of behaviors in nine comparisons and three or four types of behaviors in the other eight comparisons. In one comparison, the number of behaviors was unclear.

Outcome measures

There were large variations in the kind of outcome measure, and many studies reported multiple outcomes, especially studies on compliance with more than one guideline. Most trials measured quality of care outcomes, such as prescribing or test ordering rates. Six studies also reported patient outcomes such as blood pressure or cholesterol levels (Barnett 1983; Gilutz 2009; Heidenreich 2005; McAlister 2009; Rossi 1997; Ziemer 2006). All studies except one (Oniki 2003) reported at least one dichotomous quality of care outcome.

Excluded studies

We excluded 166 studies in this update, in addition to the 297 studies excluded in the original review. Twenty‐seven studies were excluded because of ineligible comparison or inappropriate control (e.g. physician reminder combined with another intervention versus usual care, physician reminder with a specific feature versus physician reminder without it, physician reminder versus another intervention). Four studies were excluded because reminders were presented to physicians on paper and onscreen at the same time, thus not allowing us to determine the effect of the paper reminder alone. When we retrieved full‐texts, we found that reminders in 46 studies were presented to physicians on a computer screen or sent by email. Computers were not involved in generating the reminder in 10 studies. In 21 studies, interventions were not provider reminders (e.g. audit and feedback, changes in medical records system, expert system for estimating diagnosis/risk/dosage, patient‐mediated intervention). Fourty‐four studies were excluded because of study design and 11 because the publication was not an original study. We excluded two studies because their objective was not to improve professional practice and one study did not provide sufficient information to determine its eligibility. We listed 52 of the 166 excluded studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies that may appear to meet the eligibility criteria to readers.

Risk of bias in included studies

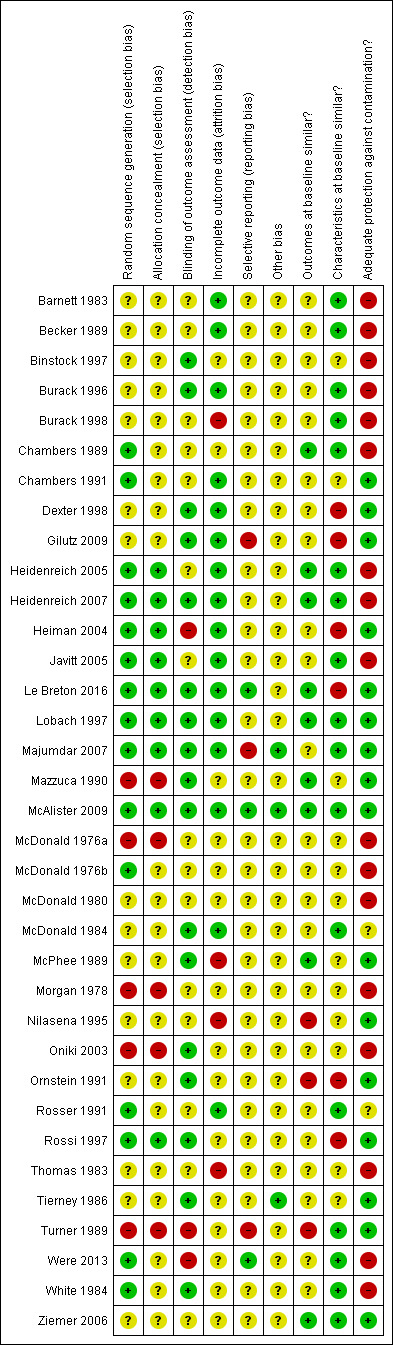

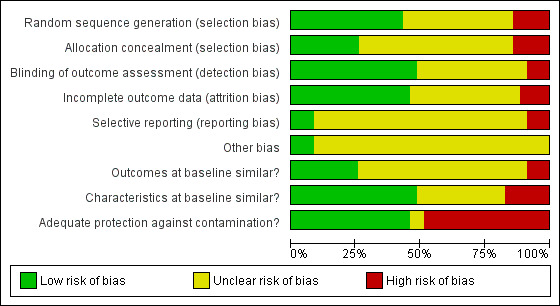

See Figure 2; Figure 3 for summaries of risk of bias, and the Characteristics of included studies for details of risk of bias in each study.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

3.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Among the 30 randomized trials, the 15 studies that described the sequence generation by referring to a computerized randomization program or a random number table (Chambers 1989; Chambers 1991; Heidenreich 2005; Heidenreich 2007; Heiman 2004; Javitt 2005; Le Breton 2016; Lobach 1997; Majumdar 2007; McAlister 2009; McDonald 1976b; Rosser 1991; Rossi 1997; Were 2013; White 1984) were at low risk of bias. The process of sequence generation was unclear for the other 15 randomized trials, which merely stated that the study groups were randomly allocated (Barnett 1983; Becker 1989; Binstock 1997; Burack 1996; Burack 1998; Dexter 1998; Gilutz 2009; McDonald 1980; McDonald 1984; McPhee 1989; Nilasena 1995; Ornstein 1991; Thomas 1983; Tierney 1986; Ziemer 2006). Allocation concealment occurred in nine randomized trials, while it was unclear in the remaining randomized trials.

The five non‐randomized trials were at high risk of bias for sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Unit of allocation issues

Of the 20 studies with a cluster design, only seven analyzed results at the level of the cluster (Lobach 1997; Mazzuca 1990; McPhee 1989; Nilasena 1995; Tierney 1986; Turner 1989; Ziemer 2006), while the other studies analyzed results at the patient level (Chambers 1991; Dexter 1998; Gilutz 2009; Heiman 2004; Le Breton 2016; Majumdar 2007; McAlister 2009; McDonald 1984; Ornstein 1991; Rosser 1991, Rossi 1997) or the reminder level (McDonald 1976a; McDonald 1980). Such unit of analysis errors artificially increase the precision of statistical tests and may lead to inappropriate conclusions. Five of these studies re‐analyzed the data taking into account the clustering effect (Dexter 1998; Heiman 2004; Le Breton 2016; McAlister 2009; Rossi 1997). One study (Majumdar 2007) minimized the unit of analysis error by not allowing physicians to contribute more than five patients.

Blinding

Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding was only assessed with regards to the outcome assessment method. Five studies reported that outcome assessors were blinded (Dexter 1998; Le Breton 2016; Majumdar 2007; McAlister 2009; White 1984) and two studies performed an audit of outcome assessments (Lobach 1997; McPhee 1989). Ten further studies reported that outcomes were derived from a computerized medical records system, minimizing risk of bias (Binstock 1997; Burack 1996; Gilutz 2009; Heidenreich 2007; Mazzuca 1990; McDonald 1984; Oniki 2003; Ornstein 1991; Rossi 1997; Tierney 1986). While two studies reported that outcomes were not assessed blindly (Heiman 2004; Turner 1989); the other studies did not report on blinding procedures.

Incomplete outcome data

Outcome data were considered complete when 80% or more of the patients randomized were included in the analyses or when reasons for attrition were similar across groups. These were reported in 16 studies (Barnett 1983; Becker 1989; Burack 1996; Chambers 1991; Dexter 1998; Gilutz 2009; Heidenreich 2005; Heidenreich 2007; Heiman 2004; Javitt 2005; Le Breton 2016; Lobach 1997; Majumdar 2007; McAlister 2009; McDonald 1984; Rosser 1991). Outcome data were considered incomplete in four studies, where the percentage of patients analyzed was less than 80% of patients randomized and no reason was given for the missing data (Burack 1998; McPhee 1989; Nilasena 1995; Thomas 1983). In the remaining studies, the number of patients lost to follow‐up was unclear.

Other potential sources of bias

Baseline measurement of the outcome of interest was reported in 13 studies. Among these studies, 10 reported that study groups were comparable at baseline (Chambers 1989; Heidenreich 2005; Heidenreich 2007; Heiman 2004; Le Breton 2016; Lobach 1997; Mazzuca 1990; McAlister 2009; McPhee 1989; Ziemer 2006), while three reported significant differences (Nilasena 1995; Ornstein 1991; Turner 1989). Across studies reporting a baseline measurement of outcome, the median difference between intervention and control groups at baseline was 1%.

Two thirds of the studies reported patient characteristics at baseline that permitted assessment of baseline heterogeneity in characteristics between study groups. Six studies reported significant differences (Dexter 1998; Gilutz 2009; Heiman 2004; Le Breton 2016; Ornstein 1991; Rossi 1997).

Lack of protection against contamination is a potential source of bias in interventions targeting healthcare professionals. Indeed, there is a risk that physicians who receive reminders for some patients but no reminders for other patients may improve their behavior in both groups, thus reducing the chance of measuring a difference between the study groups. Sixteen studies prevented contamination by allocating physicians or practices to study groups, eliminating the risk of physicians receiving reminders for some patients and no reminders for others.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

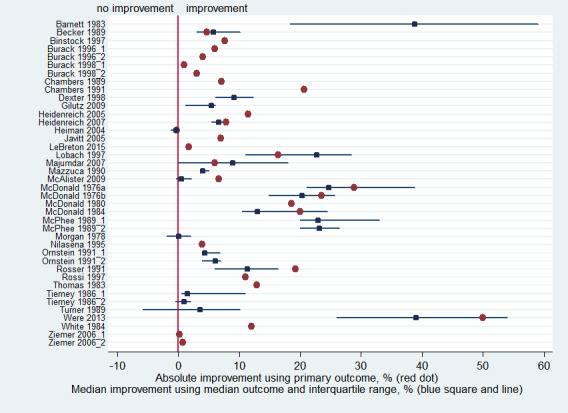

The outcomes considered for each study included in the analyses are described in detail in Table 4. The absolute improvement in quality of care for studies reporting a primary outcome and the median improvement and interquartile range (IQR) for studies reporting more than one eligible outcome are displayed in Figure 4.

1. Improvement rates of quality of care, by study.

| Study ID | Primary outcome | Other outcomes (n) | Absolute improvement ‐ using primary outcome | Median absolute improvement ‐ using other outcomes (interquartile range) |

| Barnett 1983 | percentage of eligible patients with: blood pressure values on record, follow‐up (2) | 38.8% (18.4% to 59.1%) | ||

| Becker 1989 | overall compliance rate with preventive care recommendations | percentage of eligible patients with: dental check, ocular pressure check, FOBT, flu vacc, pneumo vacc, tetanus vacc, mammography, pap smear (8) | 4.7% | 5.8% (3.0% to 10.2%) |

| Binstock 1997 | percentage of eligible patients with pap smear | 7.6% | ||

| Burack 1996_1 | percentage of eligible patients with mammography | 6.0% | ||

| Burack 1996_2 | percentage of eligible patients with mammography | 4.0% | ||

| Burack 1998_1 | percentage of eligible patients with pap smear | 1.0% | ||

| Burack 1998_2 | percentage of eligible patients with pap smear | 3.0% | ||

| Chambers 1989 | percentage of eligible patients with mammography | 7.1% | ||

| Chambers 1991 | percentage of eligible patients with flu vacc | 20.7% | ||

| Dexter 1998 | percentage of eligible patients with: discussion of directives, completion of directives (2) | 9.2% (6.1% to 12.3%) | ||

| Gilutz 2009 | percentage of patients with adequate monitoring, percentage of eligible patients with initiation or up‐titration of statin therapy, percentage of eligible patients with up‐titration (3) | 5.4% (1.2% to 6.1%) | ||

| Heidenreich 2005 | percentage of eligible patients with ACE inhibitor prescription | 11.5% | ||

| Heidenreich 2007 | percentage of eligible patients with any β‐blocker prescription | percentage of eligible patients with recommended β‐blocker prescription | 7.9% | 6.7% (5.4% to 7.9%) |

| Heiman 2004 | percentage of eligible patients with advance directives | percentage of eligible patients with: discussion or completion of directives, completion of healthcare proxy, completion of living will (3) | ‐0.2% | ‐0.3% (‐0.9% to ‐0.2%) |

| Javitt 2005 | compliance rate with prescription reminders (start a new drug) (denominator: reminders) | 7.0% | ||

| Le Breton 2016 | adherence to colorectal cancer screening | 1.7% | ||

| Lobach 1997 | overall physician compliance rate | physician compliance rate with: foot exam, physical exam, glycated hemoglobin, urine protein determination, cholesterol level, eye exam, flu vacc, pneumo vacc (8) | 16.4% | 22.7% (11.0% to 28.4%) |

| Majumdar 2007 | overall compliance rate with prescription reminders | percentage of eligible patients with: ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy prescription, statins prescription | 6.0% | 9.0% (0.0% to 18.0%) |

| Mazzuca 1990 | physician compliance rate with: glycated hemoglobin, fasting blood glucose, home‐monitored blood glucose, diet clinic referral, oral hypoglycemic agents (5) | 4.0% (4.0% to 5.0%) | ||

| McAlister 2009 | overall compliance rate with prescription reminders | percentage of eligible patients with: statins, standardized statin dose, another lipid‐lowering drug, acetylsalicylic acid, acetylsalicylic acid or thienopyridine, ACE inhibitor, ACE inhibitor or ARB, β‐blocker, triple therapy (8) | 6.6% | 0.5% (‐0.4% to 2.2%) |

| McDonald 1976a | overall compliance rate with prescription reminders (denominator: reminders) | compliance with: observing a physical finding or inquiring about a symptom, ordering a diagnostic study, changing or initiating a therapeutic regimen (3) | 28.9% | 24.7% (21.1% to 38.8%) |

| McDonald 1976b | overall compliance rate with reminders (denominator: reminders) | percentage of patients with: test order, therapeutic change (2) | 23.5% | 20.3% (14.9% to 25.7%) |

| McDonald 1980 | overall compliance rate with reminders (denominator: reminders) | 18.6% | ||

| McDonald 1984 | overall compliance rate with reminders | percentage of patients with: FOBT, pap smear, chest roentgenogram, pneumo vacc, tuberculosis skin test, serum potassium, mammogram, flu vacc, diet, digitalis, antacids, β‐blockers (12) | 20.0% | 13.0% (10.5% to 24.5%) |

| McPhee 1989_1 | physician compliance rate with: FOBT, rectal exam, sigmoidoscopy, pap smear, pelvic exam, breast exam, mammography (7) | 23.0% (20.0% to 33.0%) | ||

| McPhee 1989_2 | physician compliance rate with: breast exam, mammography (2) | 23.2% (20.0% to 26.5%) | ||

| Morgan 1978 | percentage of patients with: blood group and type, syphilis serology, prenatal counseling, pregnancy diet counseling, sickle cell preparation (5) | 0.1% (‐1.9% to 2.0%) | ||

| Nilasena 1995 | overall physician compliance rate with reminders | 3.9% | ||

| Ornstein 1991_1 | percentage of eligible patients with: FOBT, mammography, tetanus vacc, cholesterol, pap smear (5) | 4.4% (3.9% to 6.9%) | ||

| Ornstein 1991_2 | percentage of eligible patients with: FOBT, mammography, tetanus vacc, cholesterol, pap smear (5) | 6.1% (3.9% to 7.0%) | ||

| Rosser 1991 | overall compliance rate | percentage of eligible patients with: flu vacc, tetanus vacc, BP reading, pap smear (4) | 19.2% | 11.4% (6.0% to 16.4%) |

| Rossi 1997 | percentage of eligible patients with prescription change | 11.0% | ||

| Thomas 1983 | compliance rate with reminders | 12.9% | ||

| Tierney 1986_1 | physician compliance rate with: FOBT, pneumo vacc, antacids, TB skin testing, β‐blockers, nitrates, anti‐depressants, calcium supplements, pap smear, mammography, metronidazole, digitalis, salicylates (13) | 1.5% (0.5% to 11.0%) | ||

| Tierney 1986_2 | physician compliance rate with: FOBT, pneumo vacc, antacids, TB skin testing, β‐blockers, nitrates, anti‐depressants, calcium supplements, pap smear, mammography, metronidazole, digitalis, salicylates (13) | 1.0% (‐0.5% to 2.0%) | ||

| Turner 1989 | physician compliance rate with: FOBT, rectal exam, pap smear, breast exam, mammography (5) | 3.6% (‐5.8% to 10.1%) | ||

| Were 2013 | completion of overdue clinical tasks (denominator: reminders) | completion of overdue clinical task for: ordering chest x‐ray, ordering 18‐mo human immunodeficiency virus enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay, ordering other laboratory tests, beginning antiretroviral therapy, referring to nutritional support (5) | 50.0% | 39.0% (26.0% to 54.0%) |

| White 1984 | compliance rate with reminders (denominator: reminders) | 12.0% | ||

| Ziemer 2006_1 | physician compliance rate | 0.2% | ||

| Ziemer 2006_2 | physician compliance rate | 0.7% |

ACE: angiotensin‐converting enzyme, ARB: angiotensin II receptor blockers, BP: blood pressure, flu: influenza, FOBT: fecal occult blood test, pneumo: pneumococcal, TB: tuberculosis, Vacc: vaccination

4.

Absolute improvement of quality of care by study, using the primary outcome defined by authors (represented by a red dot), and median improvement by study, using the median outcome of all reported quality of care outcomes (represented by a blue square (the median) and blue line (interquartile range))

Quality of care

Computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals, alone (single‐component intervention) or in addition to co‐intervention(s) (multi‐component intervention), probably improve slightly quality of care compared with usual care or the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component (median improvement 6.8% (IQR: 3.8% to 17.5%); 34 studies (40 comparisons); moderate‐certainty evidence) (see Table 1).

Computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals alone (single‐component intervention) probably improves quality of care compared with usual care (median improvement 11.0% (IQR 5.4% to 20.0%); 27 studies (27 comparisons); moderate‐certainty evidence) (see Table 2). Adding computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals to one or more co‐interventions (multi‐component intervention) probably improves quality of care slightly compared with the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component (median improvement 4.0% (IQR 3.0% to 6.0%); 11 studies (13 comparisons); moderate‐certainty evidence) (see Table 3).

A possible explanation for the different magnitude of effect according to the presence of co‐intervention(s) would be that co‐interventions delivered to both groups leave little room for reminders to demonstrate additional improvement. Indeed, the median post‐intervention quality of care rate in the additional intervention(s) alone control groups was higher than the rate in the usual care groups (median: 27.4% versus 21.8%).

Of the 40 comparisons, 14 reported baseline quality of care rates for study groups. For these comparisons, the median marginal improvement in the intervention group (i.e. the improvement in the intervention group minus the improvement in the control group) was 3.9% (IQR 0.5% to 7%).

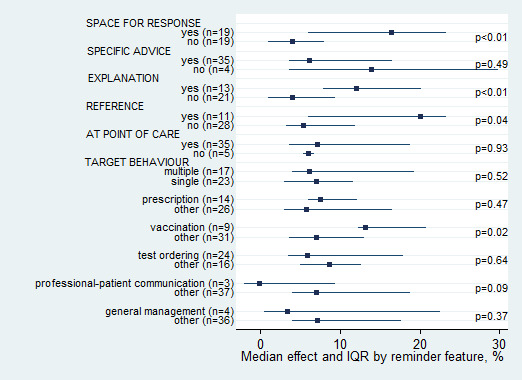

Subgroup analyses: impact of reminder features on quality of care effect size

We examined the impact of a number of characteristics of the reminders on the magnitude of effect (Figure 5). Effect size was associated with three features: the availability of space for healthcare professionals to enter a response (median 13.7% versus 4.3% for no space, P = 0.01), reminders including an explanation of their content or advice (median 12.0% versus 4.2% for no explanation, P = 0.02), and reminders explicitly from or justified by reference to an influential source (median 20.0% versus 5.4% for no reference, P = 0.04). The following reminder features were not associated: specific advice included in the reminder (median 6.1% versus 13.9%, P = 0.49), and reminders available at point‐of‐care (median 7.1% versus 6.0%, P = 0.93). The impact of whether the reminder was patient‐specific or generic was not assessed, as only one study examined generic reminders.

5.

Median effect and interquartile range (IQR) across comparisons by reminder feature (P values reflect Mann–Whitney test)

The median improvement in quality of care associated with reminders differed according to the targeted behavior but not the number of targeted behaviors. The largest improvement seen was in vaccination, with a median improvement of 13.1% (IQR 12.2% to 20.7%), while the smallest improvement seen was for professional‐patient communication, with a median reduction of ‐0.2% (IQR ‐2% to 9.2%).

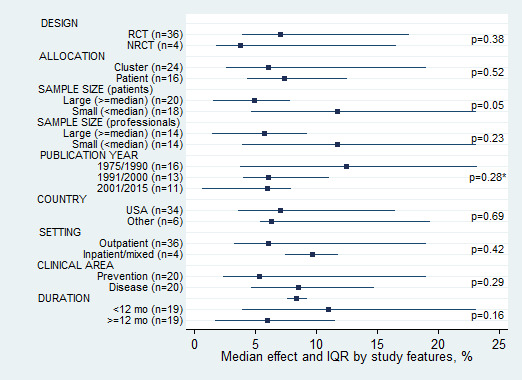

Subgroup analyses: impact of study features on quality of care effect size

There were sufficient comparisons to permit analyses of potential associations between various study features and the magnitude of effect (Figure 6). No association was found between effect size and study features, except for patient sample size. Studies with a small patient sample size achieved larger improvements than studies with a large patient sample size (median 11.8% versus 4.9%, P = 0.05).

6.

Median effect and interquartile range (IQR) across comparisons by study feature (*Kruskall–Wallis test; other P values reflect Mann–Whitney test)

Studies published up to 1990 showed larger improvements than those published after 1990 (median 12.4% for up to 1990, 6.1% for 1991 to 2000 and 6.0% for 2001 to 2015, P = 0.28). To determine whether this reflected temporal changes in baseline rates, we examined the baseline quality of care rates in the control and intervention groups in the 14 comparisons reporting baseline data; there was no temporal trend in either group. Baseline adherence rates were actually higher in the studies published before 1990 reporting baseline rates than in those published after 1990. We also looked at the post‐intervention quality of care rates in the control and intervention groups in all 40 comparisons, which were similar across the years.

Only the two cross‐over studies (McDonald 1976a; McDonald 1980) examined quality of care after the end of the reminder delivery. Neither study showed a statistical carry‐over effect of experimental effect into control periods.

Subgroup analyses: disadvantaged populations

The effect of provider reminders in settings serving disadvantaged and minority populations has been specifically evaluated in 10 studies. Eight studies took place in inner‐cities in the USA, with high rates of African‐American, economically disadvantaged, medicaid eligible and uninsured populations, aiming to improve preventive care rates (Becker 1989; Burack 1996; Burack 1998; Chambers 1989; Chambers 1991; Ornstein 1991; Turner 1989) or to improve diabetes care (Ziemer 2006). In addition, the French study (Le Breton 2016) aimed to improve screening rates in a population where a quarter lived in socio‐economically deprived areas and the Kenyan study (Were 2013) aimed to improve pediatric HIV care in a resource‐limited setting. The improvement of quality of care achieved with reminders in these studies with disadvantaged populations (median 4.2%, IQR 1.7% to 6.1%, 14 comparisons) was lower than the median improvement in studies not focusing on disadvantaged populations (median 10.3%, IQR 5.4% to 19.2%, 26 comparisons), and the overall median improvement (median 6.8%, IQR 3.8% to 17.5%, 40 comparisons). Also, the baseline quality of care rates in the studies in disadvantaged population (19.5% in the control group and 21.8% in the intervention group, seven comparisons with baseline data) was lower than the baseline quality of care rates in the studies in general population (34.6% in the control group and 38.0% in the intervention group, seven comparisons with baseline data).

Sensitivity analyses

Similar median improvement of quality of care was observed when only studies with allocation concealment and complete outcome data were considered (median improvement: 6.8%, IQR 3.9% to 9.7%) and when excluding the six studies with estimated data (median improvement: 5.0%, IQR: 1.5% to 23.0%).

Table 5 shows the results obtained when we re‐analyzed the median improvement of quality of care using the outcome with the largest improvement and the outcome with the smallest improvement for the representative outcome for each study, respectively. As expected, median improvement was larger when using the largest outcome and smaller when using the smallest outcome for all three comparisons. The IQR range included 0 in one comparison: when using the smallest outcome in the reminder with co‐intervention comparison.

2. Median improvement of quality of care across all comparisons and according to the presence of co‐interventions.

| Median improvement (interquartile range) | |||

| Using primary (or median) outcome | Using largest outcome | Using smallest outcome | |

| All (n = 40) | 6.8% (3.8% to 17.5%) |

12.0% (6.1% to 20.2%) |

4.0% (0.5% to 11.3%) |

| Reminders alone (n = 27) | 11.0% (5.4% to 20.0%) |

12.3% (7.0% to 33.5%) |

6.1% (1.2% to 12.9%) |

| Reminders with co‐intervention(s) (n = 13) | 4.0% (3.0% to 6.0%) |

9.8% (3.9% to 12.5%) |

0.7% (‐1.9% to 3.6%) |

We also re‐analyzed the impact of reminder and study features on effect size using the largest and smallest outcome for the representative outcome for each study. None of these analyses yielded substantially different findings compared with the findings using the primary (or median) outcome. The direction of the impact of the reminder and study features remained the same.

Patient outcomes

Six studies reported patient outcomes (see Table 6), but we were unable to pool them because of heterogeneity: they measured different clinical outcomes in different populations. In these studies, reminders had no measurable effect on i) blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin and cholesterol levels, ii) reaching blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin and cholesterol targets, and iii) mortality.

3. Improvement of patient outcomes, by study.

| Study ID | Patient outcome: percentage difference between groups at follow‐up | Patient outcome: mean difference between groups at follow‐up |

| Barnett 1983 | Percentage of patients with BP<100 or receiving treatment at 12 mo: 18.1% | |

| Gilutz 2009 | Event‐free survival: ‐2.1% | LDL level: ‐2.4 mg/dL |

| Heidenreich 2005 | Mortality: hazard ratio: 0.98 (95% CI: 0.78 to 1.23) | Diastolic BP: 0 Systolic BP: 0 |

| McAlister 2009 | Mortality: 1% | |

| Rossi 1997 | Diastolic BP: ‐4 Systolic BP: 0 |

|

| Ziemer 2006_1 | Percentage of patients with Hba1c<7.0%: OR: 0.98 (95% CI: 0.86 to 1.12) Percentage of patients with systolic BP<130: OR: 1.04 (95% CI: 0.94 to 1.16) Percentage of patients with LDL<100: OR 0.92 (95% CI: 0.79 to 1.08) |

Hba1c: 0.1 Systolic BP: ‐1.2 LDL level: 2.5 mg/dL |

| Ziemer 2006_2 | Percentage of patients with Hba1c<7.0%: OR: 0.99 (95% CI: 0.82 to 1.19) Percentage of patients with systolic BP<130: OR: 0.92 (95% CI: 0.79 to 1.06) Percentage of patients with LDL<100: OR 1.05 (95% CI: 0.84 to 1.31) |

Hba1c: 0.4 Systolic BP: 0.8 LDL level: 3.0 mg/dL |

BP: blood pressure, Hba1c: glycated hemoglobin, LDL: low‐density lipoprotein, mo: months

We are thus uncertain whether reminders, alone (single‐component intervention) or in addition to co‐intervention(s) (multi‐component intervention), improve patient outcomes compared with usual care or the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component as the certainty of the evidence is very low (n = 6 studies (seven comparisons)) (see Table 1).

We are uncertain whether reminders alone improve patient outcomes compared with usual care (n = 4 studies (four comparisons), very low‐certainty evidence) (see Table 2). We are also uncertain whether adding reminders to one or more co‐interventions improve patient outcomes compared with the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component (n = 2 studies (three comparisons), very low‐certainty evidence) (see Table 3).

Adverse effects

None of the included studies reported outcomes related to harms or adverse effects of the intervention.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals, alone or in addition to co‐intervention(s), probably improve slightly quality of care compared with usual care or the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component (median improvement 6.8% (interquartile range (IQR): 3.8% to 17.5%); 34 studies (40 comparisons); moderate‐certainty evidence) (see Table 1).

Computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals alone (single‐component intervention) probably improve quality of care compared with usual care (median improvement 11.0% (IQR 5.4% to 20.0%); 27 studies (27 comparisons); moderate‐certainty evidence) (see Table 2). Adding computer‐generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals to one or more co‐interventions (multi‐component intervention) probably improve slightly quality of care compared with the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component (median improvement 4.0% (IQR 3.0% to 6.0%); 11 studies (13 comparisons); moderate‐certainty evidence) (see Table 3).

We are uncertain whether reminders, alone or in addition to co‐intervention(s), improve patient outcomes compared with usual care or the co‐intervention(s) without the reminder component because the certainty of the evidence is very low. None of the included studies reported outcomes related to harms or adverse effects of the intervention, such as redundant testing or overdiagnosis.

As the authors of the on‐screen reminders have suggested (Shojania 2009), the lower improvement rate in multi‐component interventions could be due to the improved quality of care achieved by the other components of the multi‐component intervention, leaving less room for improvement by the reminder. Our analyses support this explanation as post‐intervention compliance rates were higher in the multi‐component intervention control group than the rate in the usual care group. An additional explanation offered by Shojania and colleagues might be that investigators chose to incorporate reminders in multi‐component interventions when attempting to change more complex (and therefore difficult to change) behaviors than those addressed by reminders alone.