Abstract

Background

Intermittent catheterisation is a commonly recommended procedure for people with incomplete bladder emptying. There are now several designs of intermittent catheter (e.g. different lengths, 'ready to use' presentation) with different materials (e.g. PVC‐free) and coatings (e.g. hydrophilic). The most frequent complication of intermittent catheterisation is urinary tract infection (UTI), but satisfaction, preference and ease of use are also important to users. It is unclear which catheter designs, techniques or strategies affect the incidence of UTI, which are preferable to users and which are most cost effective.

Objectives

To compare one type of catheter design versus another, one type of catheter material versus another, aseptic catheterisation technique versus clean technique, single‐use (sterile) catheters versus multiple‐use (clean) catheters, self‐catheterisation versus catheterisation by others and any other strategies designed to reduce UTI and other complications or improve user‐reported outcomes (user satisfaction, preference, ease of use) and cost effectiveness in adults and children using intermittent catheterisation for incomplete bladder emptying.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register, which contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, MEDLINE in process, and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings (searched 30 September 2013), the reference lists of relevant articles and conference proceedings, and we attempted to contact other investigators for unpublished data or for clarification.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or randomised cross‐over trials comparing at least two different catheter designs, catheterisation techniques or strategies.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors assessed the methodological quality of trials and abstracted data. For dichotomous variables, risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals were derived for each outcome where possible. For continuous variables, mean differences and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each outcome. Because of trial heterogeneity, it was not always possible to combine data to give an overall estimate of treatment effect.

Main results

Thirty‐one trials met the inclusion criteria, including 13 RCTs and 18 cross‐over trials. Most were small (less than 60 participants completed), although five trials had more than 100 participants. There was considerable variation in length of follow‐up and definitions of UTI. Participant dropout was a problem for several trials, particularly where there was long‐term follow‐up to measure incidence of UTI. Fifteen trials were more than 10 years old and focused mainly on comparing different catheterisation techniques (e.g. single versus multiple‐use) on clinical outcomes whereas, several more recent trials have focused on comparing different types of catheter designs or materials, especially coatings, and user preference. It was not possible to combine data from some trials owing to variations in the catheters tested and in particular the catheter coatings. Where there were data, confidence intervals around estimates were wide and hence clinically important differences in UTI and other outcomes could neither be identified nor reliably ruled out. No study assessed cost‐effectiveness.

Authors' conclusions

Despite a total of 31 trials, there is still no convincing evidence that the incidence of UTI is affected by use of aseptic or clean technique, coated or uncoated catheters, single (sterile) or multiple‐use (clean) catheters, self‐catheterisation or catheterisation by others, or by any other strategy. Results from user‐reported outcomes varied. The current research evidence is weak and design issues are significant. More well‐designed trials are strongly recommended. Such trials should include analysis of cost‐effectiveness because there are likely to be substantial differences associated with the use of different catheter designs, catheterisation techniques and strategies.

Keywords: Adult, Child, Female, Humans, Male, Urinary Catheters, Urinary Catheters/adverse effects, Equipment Reuse, Patient Dropouts, Urinary Catheterization, Urinary Catheterization/adverse effects, Urinary Catheterization/instrumentation, Urinary Catheterization/methods, Urinary Retention, Urinary Retention/therapy, Urinary Tract Infections, Urinary Tract Infections/etiology, Urinary Tract Infections/prevention & control

Intermittent catheterisation for long‐term bladder management

Background

Intermittent catheterisation is a common treatment used by people who have bladder emptying problems. A hollow tube (catheter) is passed through the channel to the bladder (urethra) or through a surgically made channel to the skin surface to regularly empty the bladder, usually several times every day. This treatment is used by people who have difficulty emptying their bladders themselves. However, this treatment often causes urine infections resulting in school or work absences or even hospitalisations.

Review question

There are different catheter designs and techniques which may affect urine infection. In this review we focused on urine infection in people who used different catheterisation techniques; different designs of catheter (coated [pre‐lubricated] or uncoated [separate or no lubricant]); sterile (single‐use) catheters or clean (multiple‐use) catheters; self‐catheterisation or catheterisation by others (such as parents or carers); and other strategies designed to reduce urine infection, including different ways of catheter cleaning for multiple‐use. We also focused on user satisfaction, preference and ease of use.

Study characteristics

Studies on urine infection and intermittent catheterisation are difficult for researchers to undertake because participants need to take part for many months and tend to drop out. Many of the reviewed trials were too small and had problems with participants not wanting to continue in the trial. Definitions of urine infection also varied considerably. Thus well‐designed and long‐term trials are strongly recommended.

Key results and quality of the evidence

Thirty‐one trials were included in the review. Currently, the evidence is weak and it is not possible to state that any catheter design, technique or strategy is better than another. Future research should consider cost as it is likely that there are big differences between different catheter designs and techniques.

Background

Intermittent catheterisation (IC) is the act of passing a catheter into the bladder to drain urine via the urethra or other catheterisable channel such as a Mitrofanoff continent urinary diversion (surgically constructed passage connecting bladder with abdominal surface). The catheter is removed immediately after urine drainage is complete. It is widely advocated as an effective bladder management strategy for incomplete bladder emptying.

IC can be undertaken by people of all ages, including the very elderly and children as young as four years old with parental supervision. Carers can also be taught the procedure where this is acceptable both to the IC user and carer. Even some people with disabilities such as blindness, lack of perineal sensation, tremor, mental disability and paraplegia can learn how to master the technique (Cottenden 2013).

Individualised care plans should identify appropriate catheterisation frequency based on user goals, impact on quality of life, frequency‐volume charts, functional bladder capacity and post voiding residual urine. The number of catheterisations per day varies; a general rule for adults is to catheterise frequently enough to avoid a bladder urine volume greater than 500 mL but clinical decisions are also provided by urodynamic findings, detrusor pressures on filling, presence of reflux and renal function.

Advantages of IC over indwelling catheterisation include:

greater opportunity for self‐care and independence;

reduced risk of common indwelling catheter‐associated complications, such as damage to the urethra or bladder neck, creation of false passages, persistent symptomatic urinary tract infection, stones in the bladder;

reduced need for equipment and appliances e.g. drainage bag;

greater freedom for expression of sexuality;

potential for reduced urinary symptoms (frequency, urgency, incontinence) between catheterisations.

Reviewing the topic, Wyndaele 2002 provides a full discussion of the benefits as well as potential adverse effects of IC. Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the most frequent complication and catheterisation frequency and the avoidance of bladder over‐filling are recognised as important prevention measures. It is recognised that prostatitis is a risk in men, but epididymitis and urethritis are relatively rare. Trauma from catheterisation, measured by haematuria, is reported but lasting effects appear limited. Estimates of the prevalence of urethral strictures and false passages increase with longer use of IC or with traumatic catheterisation. In a follow‐up of children with spina bifida who had used IC with an uncoated PVC catheter and added lubricant for at least five years, the incidence of urethritis, false passage, or epididymitis was very low and adherence to the protocol was excellent (Campbell 2004). Wyndaele and colleagues concluded that the most important preventative measures were good education of all involved in IC, adherence to the catheterisation protocol, use of an appropriate catheter material and good catheterisation technique, although the level of evidence for these clinical opinions is weak.

Designs and characteristics of catheters used in IC vary considerably so evaluation and selection of products is complex. Plain uncoated catheters (typically clear plastic PVC) are packed singly in sterile packaging. As per industry standards, all disposable catheters are labelled for one time use but PVC catheters are frequently reused because of cost or concern about the environment. Most are used with separate lubricant, although this is a matter of personal choice, some IC users preferring not to use lubricant or just to use water. Cleansing of the catheter varies from being washed with soap and water, boiled, soaked in disinfectant, or microwaved. Cleaned catheters are air dried and then stored in a convenient container (often plastic containers or bags). Coated catheters are single‐use only (they may not be cleaned and reused) and are designed to improve catheter lubrication and ease of insertion,which may (according to manufacturers) reduce trauma and UTI. The most common coating is hydrophilic, which is either pre‐activated, or requires the addition of water at the time of use to form a lubricious layer. Some non‐hydrophilic catheter designs are pre‐lubricated (whereby the catheter is supplied pre‐packed with a coating of water‐soluble gel). There are also several pre‐lubricated products with an integrated collection bag (all‐in‐one) which gives flexibility for the user and is efficient for hospital use. Finally, the design of catheters also varies, for example, length of catheter (standard versus more compact).

Definition of terms

1. Symptomatic UTI: a positive urine culture and the presence of symptoms, based on the UTI definition of the NIDRR 1992 (positive urine culture with pyuria and one or more systemic symptoms [fever, loin pain, dysuria, urgency, haematuria]). Some trials had varying definitions and we chose to accept symptomatic UTI as reported in the trials reviewed.

2. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: positive urine culture but absence of symptoms, again as reported in the trials.

3. Catheter design: different shapes, sizes, lengths and tips of catheter, different packaging

3a: Hydrophilic coated

i. Activated system, ready to use

ii. Activated closed system with integrated collection bag

iii. Not activated: sterile water provided in package for activation

iv. Not activated: water added by user

3b: Uncoated

i. Pre‐lubricated closed system with integrated collection bag

ii. Pre‐lubricated system with protective sleeve for no‐touch insertion

iii. Non‐lubricated: water‐soluble gel added by user.

4. Catheter materials: the base material of the catheter (e.g. PVC, PVC‐free, latex) and the presence or not of a bonded coating (e.g. hydrophilic).

5. Aseptic Technique (also referred to as ‘sterile’ technique in some older trials): sterile gloves, sterile single‐use catheter, sterile cleansing solution, sterile drainage tray and an aseptic technique for the catheterisation procedure.

6. Clean technique: clean gloves (or no gloves in the case of a user self‐catheterising), non‐sterile cleansing solution and a clean receptacle in which to drain urine. It should be noted that an aseptic technique always includes a sterile (single‐use) catheter whereas a clean technique may include a sterile catheter or a clean (multiple‐use) catheter.

7. Sterile catheters: catheters removed from sterile packaging and used once only. Coated catheters have a hydrophilic or other lubricated coating intended to replace the need for separate lubricant. Coated catheters are not intended for re‐use and are therefore defined as sterile.

8. Clean Catheters: Sterile catheters which are then re‐used after cleaning, typically with soap and water and air dried. The material is uncoated. Lubricant may be applied before insertion.

Objectives

To determine if certain designs of catheter, catheterisation technique, or other strategies (including re‐use) are better than others in terms of UTI, complications, user satisfaction, preference, ease of use and/or cost‐effectiveness for adults and/or children whose long‐term (with no predicted endpoint) bladder management is by IC.

The following specific comparisons were addressed.

Aseptic technique versus clean/other aseptic technique

Single‐use (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter

Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated)

One catheter length versus another catheter length

Any other techniques, strategies or designs that influence UTI, other complications or user‐reported outcomes

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised clinical trials, including cross‐over trials, comparing catheterisation designs, techniques and other strategies for long‐term bladder management by IC.

Types of participants

Adults or children requiring IC for long‐term bladder management.

Types of interventions

Comparisons of intermittent catheter designs, catheterisation techniques and catheterisation strategies.

Types of outcome measures

1. Catheter‐associated infection (definition of infection as used in trial reports)

Symptomatic UTI (primary outcome variable)

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

2. Other complications/adverse effects

Urethral trauma/bleeding

Creation of false passages

Haematuria

Stricture formation

3. Participant‐assessed outcomes

Comfort, including ease of insertion and removal

Satisfaction

Preferences

Quality of life measures

4. Economic outcomes

Catheter and equipment costs

Frequency of catheterisation

Resource implications (personnel and other costs to services)

Formal economic analysis (cost‐effectiveness, cost‐utility)

Days missed from employment/school

5. Other outcomes

Microbiological culture of catheter surfaces

Additional outcomes judged to be important when performing the review

Search methods for identification of studies

We did not impose any language or other limits on the searches.

Electronic searches

The review strategy was that developed for the Cochrane Incontinence Review Group. Relevant trials were identified from the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register of controlled trials which is described, along with the search strategy, under the Incontinence Group's module in The Cochrane Library. The Register contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, MEDLINE in process, and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings. The Incontinence Group Specialised Register was searched using the Group's own keyword system. Search terms were:

topic.urine.incon* AND ({design.cct*} OR {design.rct*}) AND intvent.mech.cath* (All searches were of the keyword field of Reference Manager 2012).

The date of the most recent search of the Register for this version of the review was 30 September 2013.

Extra specific searches were also performed by the review authors details of which are given in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of relevant articles and conference proceedings for other possible trials. We also contacted one investigator for clarification, which was provided (Cardenas 2011).

Data collection and analysis

Trial selection

To be comprehensive in the initial reviews, three review authors (JP, MF and KM) assessed each title and abstract of trials identified by the search strategy and a final list was agreed on. Full reports were obtained of all potentially relevant randomised controlled trials based on defined inclusion criteria.

The agreed list of eligible trials was then assessed independently by two of the review authors (JP and MF). Cochrane 'Risk of bias' forms were completed for all trials so that the quality of random allocation, concealment, description of dropouts and withdrawals, analysis by intention‐to‐treat, and blinding during intervention and at outcome assessment or any other potential biases were consistently addressed. Any disagreements between primary review authors (JP and MF) were also discussed with KM and CM and consensus reached.

Methodological quality assessment

The quality of eligible trials was assessed independently by two of the review authors (JP, MF) using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool, which includes quality of random allocation and concealment, blinding during intervention and at outcome assessment, dropouts and withdrawals, and source of funding. When trial quality was assessed any disagreements between review authors were discussed and consensus reached. 'Risk of bias' forms were completed for all trials.

Data abstraction

Relevant data regarding inclusion criteria (trial design, participants, interventions and outcomes), quality criteria (randomisation, blinding and control) and results were extracted independently by two review authors using a data abstraction form developed specifically for this review. Excluded trials and reasons for exclusion have been detailed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

In the original review (Moore 2007), we included 14 trials. For the current review an additional 33 were identified, of which 17 met the inclusion criteria. Two trials (Fader 2001; Pascoe 2001) excluded from the original review met the revised inclusion criteria. In all, 18 studies were excluded: one was a review, 17 did not meet the review inclusion criteria. The final number was 31 trials addressing some aspect of sterile or clean intermittent catheterisation and using a measure of catheter‐associated infection, other complication, or participant satisfaction.

Trial participants were mainly adults with spinal cord injuries, but also included other groups such as children with neurogenic bladders due to myelomeningocoele, men with prostatic obstruction and women with multiple sclerosis. Those trials that used infection as the primary outcome variable were generally of longer duration (three to 12 months) and those that focused on participant preference/ease of use were generally of shorter duration (eight weeks or less). There were variations in definitions of UTI. Attrition was a problem for several trials and most were underpowered. Fifteen trials were between 10 and 20 years old. The flow of literature through the assessment process is shown in the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA study flow diagram

Included Studies

Thirty‐one trials met the inclusion criteria (Biering‐Sorensen 2007; Cardenas 2009; Cardenas 2011; Chartier‐Kastler 2011; Chartier‐Kastler 2013; Costa 2013; Day 2003; Denys 2012; De Ridder 2005; Domurath 2011; Duffy 1995; Fader 2001; Fera 2002; Giannantoni 2001; King 1992; Leek 2013; Leriche 2006; Mauroy 2001; Moore 1993; Moore 2006; Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Pascoe 2001; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Quigley 1993; Sarica 2010; Schlager 2001; Sutherland 1996; Taweesangsuksalul 2005; Vapnek 2003; Witjes 2009).

Eight of the 31 trials did not provide data in a format that could be used in meta‐analysis (Denys 2012; Fader 2001; Fera 2002; Giannantoni 2001; Mauroy 2001; Pascoe 2001, Sarica 2010; Taweesangsuksalul 2005).

Design

There were 13 parallel group randomised controlled trials (Cardenas 2009; Cardenas 2011; Day 2003; De Ridder 2005; Duffy 1995; Fera 2002; King 1992; Moore 2006; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Quigley 1993; Sutherland 1996; Vapnek 2003; Witjes 2009).

The other 18 were cross‐over randomised controlled trials:

15 with two arms (Biering‐Sorensen 2007; Chartier‐Kastler 2013; Chartier‐Kastler 2011; Costa 2013; Denys 2012; Domurath 2011; Giannantoni 2001; Leek 2013; Leriche 2006; Moore 1993; Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Pascoe 2001; Schlager 2001; Taweesangsuksalul 2005);

two with three arms (Mauroy 2001; Sarica 2010); and

one with four arms (Fader 2001).

As the number of randomised trials was adequate for the review, it was not deemed necessary to include non‐randomised trials. The inherent risk of bias in a non‐randomised design makes the results difficult to apply to outcomes such as urinary tract infection. In particular, the studies reviewed had design limitations; non‐randomisation would have compounded the limitations. However, further consideration could be given to the use of both non‐randomised and qualitative studies to assess user opinion or cost‐effectiveness.

Sample sizes

A total of 1737 participants were enrolled in the 31 trials with 1388 (80%) of all participants completing data collection. However, in two studies involving a total of 224 participants, the completion rate was not stated and we have assumed that all participants completed.

In most trials the sample size was small. Only five of the 31 trials had a sample size of 100 or more (Cardenas 2011; Chartier‐Kastler 2013; De Ridder 2005; Denys 2012; Witjes 2009).

Twelve trials included statistical power calculations (Biering‐Sorensen 2007; Cardenas 2009; Cardenas 2011; Chartier‐Kastler 2011; Chartier‐Kastler 2013; De Ridder 2005; Domurath 2011; Fader 2001; Leek 2013; Moore 2006; Moore 2013; Witjes 2009) only one (Chartier‐Kastler 2013) was able to achieve its predicted sample size.

At trial endpoint, sample sizes ranged from 10 (Schlager 2001; Taweesangsuksalul 2005) to 114 (Cardenas 2011) participants in total.

Participants

Trials included various types of patients using IC:

spinal cord injury (Cardenas 2011; Day 2003; De Ridder 2005; Denys 2012; Domurath 2011; Giannantoni 2001; King 1992; Moore 2006; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Sarica 2010);

patents with spinal cord injury who had experienced more than one UTI (Cardenas 2009);

stroke (Quigley 1993);

spinal cord lesion (Biering‐Sorensen 2007; Chartier‐Kastler 2011);

prostatic obstruction from prostatic hyperplasia (Duffy 1995; Pachler 1999);

children with spina bifida (Moore 1993; Moore 2013; Schlager 2001);

spinal cord injury, Hinman syndrome, or spinal dysraphism (Sutherland 1996);

neurogenic bladder disorders (Costa 2013; Taweesangsuksalul 2005);

vesico‐sphincteric problem of neurological origin (Leriche 2006);

a variety of diagnoses (Chartier‐Kastler 2013; Fera 2002; Leek 2013; Mauroy 2001; Witjes 2009);

no stated aetiology of the bladder dysfunction (Fader 2001; Pascoe 2001; Vapnek 2003).

Age and gender also varied:

boys and girls with spina bifida (Moore 1993; Moore 2013; Schlager 2001);

boys with neurogenic bladders (Sutherland 1996);

adult men with prostatism (Duffy 1995; Pachler 1999);

adult men with a vesico‐sphincteric problem of neurological origin (Leriche 2006);

adult men and women with spinal cord injury or lesion (Biering‐Sorensen 2007; Cardenas 2009; Cardenas 2011; Chartier‐Kastler 2011; Chartier‐Kastler 2013; Day 2003; De Ridder 2005; Denys 2012,Domurath 2011; King 1992; Moore 2006, Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Sarica 2010);

adult males and females with non‐specified neurogenic bladder (Costa 2013; Leek 2013, Taweesangsuksalul 2005).

Twelve trials included only men as participants (Chartier‐Kastler 2011; Day 2003; De Ridder 2005; Domurath 2011; Duffy 1995; King 1992; Leriche 2006; Fader 2001; Pachler 1999; Sarica 2010; Sutherland 1996; Vapnek 2003); and one included women only (Biering‐Sorensen 2007). Age and gender were not stated in one (Quigley 1993), and gender was not stated in another (Pascoe 2001).

Setting

Settings ranged from:

acute care within an intensive care unit (Day 2003);

rehabilitation hospital (Biering‐Sorensen 2007; Giannantoni 2001; King 1992; Moore 2006; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Quigley 1993);

spinal cord injury unit with follow‐up in the community (Cardenas 2011);

hospital outpatient clinic (Chartier‐Kastler 2011; Fera 2002; Leek 2013; Leriche 2006; Martins 2009; Mauroy 2001; Sarica 2010);

continuing or long‐term care (Duffy 1995);

paediatric clinic (Moore 2013);

community (Cardenas 2009; De Ridder 2005; Fader 2001; Moore 1993; Pachler 1999; Pascoe 2001; Schlager 2001; Sutherland 1996; Vapnek 2003).

The setting was not described in six trials (Chartier‐Kastler 2013; Costa 2013; Denys 2012; Domurath 2011; Taweesangsuksalul 2005; Witjes 2009).

Types of interventions

Interventions were separated into five main categories but in each of these there were variations in technique, catheter design and multiple‐use versus single‐use. In most cases there was no clear distinction made between self and caregiver/healthcare professional catheterisation. There were various comparisons made:

aseptic versus clean or other aseptic technique (Day 2003, Duffy 1995; King 1992; Moore 2006; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Quigley 1993);

single‐use (sterile) catheters to multiple‐use (clean) catheters (Duffy 1995; King 1992; Leek 2013; Moore 1993; Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Schlager 2001; Sutherland 1996; Vapnek 2003);

hydrophilic‐coated catheters or pre‐lubricated catheters with standard (coated or uncoated) catheters (Cardenas 2009; Cardenas 2011; De Ridder 2005; Fader 2001; Leriche 2006; Mauroy 2001; Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Pascoe 2001; Sarica 2010; Sutherland 1996; Vapnek 2003; Witjes 2009);

uncoated catheter compared with a pre‐lubricated catheter (Giannantoni 2001);

one catheter length versus another length (Biering‐Sorensen 2007; Chartier‐Kastler 2011; Chartier‐Kastler 2013; Costa 2013; Domurath 2011);

one gel versus a standard gel (Fera 2002; Taweesangsuksalul 2005).

No trials were found comparing cleaning techniques or self‐catheterisation to catheterisation by others. The numbers add up to more than 31 since some trials fit into more than one category. Within these categories were various subcategories which are presented in detail in the Results section below.

Duration of intervention

In each arm of the cross‐over trials participants were catheterised for either one catheterisation (Taweesangsuksalul 2005); one to two days (Biering‐Sorensen 2007, Domurath 2011); one week (Fader 2001, Pascoe 2001); 12 to 14 days (Chartier‐Kastler 2011); three to four weeks (Pachler 1999, Denys 2012); six to seven weeks (Sarica 2010, Giannantoni 2001); 12 weeks (Chartier‐Kastler 2013), four months (Leek 2013, Schlager 2001); six months (Moore 1993), 48 weeks (Moore 2013); or for the time required to use 10 catheters (Costa 2013), 20 catheters (Leriche 2006), or 27 catheters (Mauroy 2001).

In the 13 parallel group trials, the duration of intervention varied:

24 hours (Day 2003);

four days (Quigley 1993);

one month (King 1992; Witjes 2009);

two months (Sutherland 1996);

three months (Duffy 1995);

four months (Fera 2002);

up to six months (Cardenas 2011);

up to 12 months (Cardenas 2009; De Ridder 2005; Moore 2006; Vapnek 2003);

or was of unclear duration (Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999).

Outcome measures

Twenty trials reported either symptomatic UTI or asymptomatic bacteriuria as the primary outcome measure (Cardenas 2009; Cardenas 2011; Day 2003; De Ridder 2005; Duffy 1995; Fera 2002; Giannantoni 2001; King 1992; Leek 2013; Mauroy 2001; Moore 1993; Moore 2006; Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Quigley 1993; Sarica 2010; Schlager 2001; Sutherland 1996; Vapnek 2003).

The definition of symptomatic UTI varied between trials from 'clinical infection with symptoms of UTI and for which treatment was prescribed' to 10x5 CFU/mL (colony‐forming units/millilitre) plus at least one of the following symptoms of fever, pyuria, haematuria, chills, increased spasms or autonomic dysreflexia. (See the Characteristics of included studies table for a complete description provided in each report).

Six trials reported on either microscopic or macroscopic haematuria (De Ridder 2005; Mauroy 2001; Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Sutherland 1996; Vapnek 2003).

16 trials included user‐reported outcomes (Biering‐Sorensen 2007; Cardenas 2011; Chartier‐Kastler 2011; Chartier‐Kastler 2013; Costa 2013; Domurath 2011; Fader 2001; Giannantoni 2001; Leriche 2006; Mauroy 2001; Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Pascoe 2001; Sarica 2010; Taweesangsuksalul 2005; Witjes 2009). Some trials reported overall satisfaction, others reported mean satisfaction. These results could not be combined as they provided dichotomous and continuous data. Moreover, the tools used to measure user‐reported outcomes varied widely and only one trial used a validated tool (Chartier‐Kastler 2011).

Although some of the trials included calculations of the costs of one catheter versus another, none of the trials undertook a formal evaluation of cost‐effectiveness.

Excluded trials

Eighteen trials were excluded: one was a review, 17 did not meet the review inclusion criteria. (See the Characteristics of excluded studies table).

On‐going trials

None known.

Risk of bias in included studies

Details of the quality of each trial are given in the 'Risk of bias' tables in Characteristics of included studies. The findings are summarised in Figure 2; Figure 3.

Figure 2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

As with the review in 2007, the trials as a whole were methodologically weak. They were generally underpowered with variations in outcomes, particularly with respect to the definition of UTI and outcomes addressing participant preference. In the previous review, some studies included bacteriuria in the absence of symptoms (asymptomatic bacteriuria) as an outcome. The updated search of trials reflected current practice in which asymptomatic bacteriuria is not considered clinically relevant as a marker for UTI and only one trial included this measure (Leek 2013). Follow‐up ranged from 24 hours to 12 months; 15 of the 31 trials were more than 10 years old and were typically less rigorous in design and analysis. Attrition of participants was a particular problem (see below).

Allocation

The majority of the trial reports did not describe the method of allocation. In those that did, two (Moore 2006; Moore 2013) used opaque sealed envelopes opened by a third party who informed the research nurse of the assignment. De Ridder 2005 randomised participants in blocks of four and used opaque envelopes opened by the investigator but supplied from a central research office, and Quigley 1993 used 'blind selection of a marked piece of paper from a box'. Duffy 1995 did not describe method of randomisation but did indicate participants were stratified for research site or presence/absence of UTI. Eleven trials did not describe the method of randomisation, stating only that participants were 'randomised'.

Blinding

Mauroy 2001 masked all three test products. Other authors were unable to blind participants due to catheter packaging.

Data entry clerk and laboratory staff were blinded in six trials (Biering‐Sorensen 2007; Leek 2013; Moore 2006; Moore 2013; Sarica 2010; Witjes 2009).

Incomplete outcome data

In three studies (Cardenas 2011; De Ridder 2005; Moore 2013), attrition bias was assessed to be high risk. In each study the rate of dropout was higher in the hydrophilic‐coated arm compared to the uncoated arm.

In the De Ridder 2005 trial only 53% of the participants in the standard (uncoated) catheter group and 41% of the participants in the treatment (hydrophilic‐coated) catheter groups remained at the 12‐month study endpoint. Similar challenges were met by Cardenas 2011 with 60% of participants remaining in the standard (uncoated) arm and 43% in the treatment (hydrophilic‐coated) arm. Moore 2013 reported a completion rate of 75% in the standard (uncoated) arm and 62% in the treatment (coated) arm. Reasons for dropouts in all three trials included loss to follow‐up, preference for one study product, adverse events and withdrawing consent and improvement in voiding function as spinal cord injury healed. In the Cardenas 2011 and De Ridder 2005 trials, change in voiding status meant that some participants no longer required on‐going IC.

Other potential sources of bias

Intention‐to‐treat analysis

Three authors described intention‐to‐treat analysis (Chartier‐Kastler 2011; Moore 2006; Witjes 2009).

Source of funding

The source of funding was stated in 22 of the 31 studies, with 16 of those supported by industry (see 'Risk of bias' tables). In two of the 16 industry‐supported studies it was stated that only products were supplied for testing, whereas in the other 14 studies the extent of funding was unclear.

Effects of interventions

Comparison 01: Aseptic technique versus clean/other aseptic technique.

Six trials (Day 2003; Duffy 1995; King 1992; Moore 2006; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Quigley 1993) reported on types of catheterisation technique. Three trials (Day 2003; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Quigley 1993) compared an uncoated, pre‐lubricated catheter with an integrated bag versus an uncoated, non‐lubricated catheter to determine whether there was a difference in the incidence of UTI or asymptomatic bacteriuria. Whereas Day 2003 and Quigley 1993 used an aseptic technique in both arms, Prieto‐Fingerhut used aseptic technique with the pre‐lubricated catheter closed system and clean technique with the open system. Three trials (Duffy 1995; King 1992; Moore 2006) compared aseptic versus clean technique using uncoated, non‐lubricated catheters.

1.1 Asymptomatic bacteruria

Day 2003 and Moore 2006 both reported asymptomatic bacteriuria (Analysis 1.1). Day 2003 was a feasibility trial, which found that none of six participants in the closed system arm had asymptomatic bacteriuria compared to two out of five participants in the open system arm. For Moore 2006, the results were similar in the two groups (seven out of 16 for the aseptic arm versus nine out of 20 for the clean arm). The trials were too small to be reliable.

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Aseptic technique versus clean/other aseptic technique, Outcome 1 Number with asymptomatic bacteriuria.

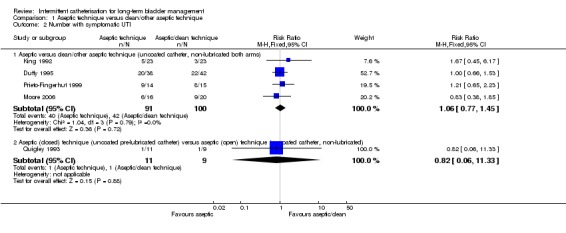

1.2 Symptomatic UTI

Five out of the six trials reported symptomatic UTI (Duffy 1995; King 1992; Moore 2006; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Quigley 1993) (Analysis 1.2). All had wide confidence intervals and there was no apparent trend favouring either technique.

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Aseptic technique versus clean/other aseptic technique, Outcome 2 Number with symptomatic UTI.

1.3 Weeks to onset of UTI

Three trials (Duffy 1995; King 1992; Moore 2006) measured mean time to onset of UTI. None showed statistically significant results favouring either technique (Analysis 1.3). Mean onset ranged from 4.3 weeks (aseptic group) and 4.6 weeks (clean group) (Moore 2006); 3.11 weeks (aseptic group) and 3.48 weeks (clean group (Duffy 1995); and 1.25 weeks (aseptic group) and 1.12 weeks (clean group) (King 1992).

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Aseptic technique versus clean/other aseptic technique, Outcome 3 Weeks to onset of symptomatic UTI.

Comparison 02: Single‐use (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter

Five parallel trials (Duffy 1995; King 1992; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Sutherland 1996; Vapnek 2003) and five two‐arm cross‐over trials (Leek 2013; Moore 1993; Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Schlager 2001) compared single‐use (sterile) catheters with multiple‐use (clean) catheters. Six used clean technique in both arms (Leek 2013; Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Schlager 2001; Sutherland 1996; Vapnek 2003) and four trials used aseptic technique with the single‐use catheter and clean technique with the multiple‐use catheter (Duffy 1995; King 1992; Moore 1993; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999). Six compared one uncoated catheter used once with another uncoated catheter used multiple times (Duffy 1995; King 1992; Leek 2013; Moore 1993; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Schlager 2001). In these trials the uncoated, non‐lubricated catheter used was the same in both arms, with the exception of Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999 who compared an uncoated, pre‐lubricated catheter with an integrated bag with an uncoated, non‐lubricated catheter. Four compared a hydrophilic‐coated (not activated) single‐use catheter with an uncoated, non‐lubricated (water added by user) multiple‐use catheter (Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Sutherland 1996; Vapnek 2003).

Trial time frames ranged from three weeks to 12 months. Cleaning methods varied as did the number of times the multiple‐use catheter was re‐used. Pachler 1999, King 1992 and Vapnek 2003 instructed participants to use the cleaned catheter for 24 hours; in the Duffy 1995 and Moore 2013 trials clean catheters were re‐used for one week; Sutherland 1996, Moore 1993, Schlager 2001 and Leek 2013 do not describe the number of re‐uses of the non‐coated catheter.

2.1 Number with asymptomatic bacteriuria

Four cross‐over trials reported on the prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria (Leek 2013; Moore 1993; Pachler 1999; Schlager 2001) (Analysis 2.1). None reported a significant difference between the two arms.

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 1 Number with asymptomatic bacteriuria.

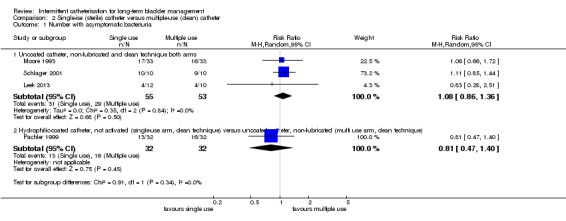

2.2 Number with symptomatic UTI

Eight studies reported on number of symptomatic UTI, four parallel trials (Duffy 1995; King 1992; Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999; Sutherland 1996) and four cross‐over studies (Leek 2013; Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Schlager 2001) (Analysis 2.2). All lay across the no‐difference line. We decided not to derive a summary estimate because of heterogeneity; however, there was no suggestion of a trend favouring either of the approaches.

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 2 Number with symptomatic UTI.

2.3 Weeks to onset of symptomatic UTI

Two trials (Duffy 1995; King 1992) addressed weeks to onset of UTI and found no statistically significant differences (Analysis 2.3).

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 3 Weeks to onset of symptomatic UTI.

2.4 Number with microscopic haematuria

One RCT (Sutherland 1996) reported no significant difference in microscopic haematuria between arms (Analysis 2.4).

Analysis 2.4.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 4 Number with microscopic haematuria.

2.5 Number with urethral trauma/bleeding/macroscopic bleeding

One cross‐over trial (Pachler 1999) reported on bleeding and no significant difference was found between arms (Analysis 2.5).

Analysis 2.5.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 5 Number with urethral trauma/bleeding/macroscopic haematuria.

2.6 Overall satisfaction

The only trial reporting overall satisfaction as an outcome was Moore 2013, who found a slightly higher number (42/48) of participants reporting satisfaction with the multiple‐use (uncoated) catheter compared to the single‐use (hydrophilic‐coated) catheter (35/48) (Analysis 2.6).

Analysis 2.6.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 6 Number reporting overall satisfaction.

2.7 Mean satisfaction

Sutherland 1996 reported on mean satisfaction level with no statistical difference found (Analysis 2.7).

Analysis 2.7.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 7 Mean satisfaction.

2.8 Ease of handling

The Pachler 1999 cross‐over trial found no significant difference between arms. The Moore 2013 cross‐over trial found in favour of the control arm (Analysis 2.8).

Analysis 2.8.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 8 Number reporting ease of handling.

2.9 Mean ease of handling

Sutherland 1996 reported a mean ease of handling with no statistical difference found (Analysis 2.9).

Analysis 2.9.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 9 Mean ease of handling.

2.10 Ease of insertion

Pachler 1999 found no significant difference between the two arms for ease of insertion (Analysis 2.10).

Analysis 2.10.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 10 Number reporting ease of insertion.

2.11 Mean ease of insertion

Sutherland 1996 found no significant difference in mean ease of insertion (Analysis 2.11).

Analysis 2.11.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 11 Mean ease of insertion.

2.12 Number reporting comfort

In the Moore 2013 trial there was no significant difference in reported comfort (Analysis 2.12).

Analysis 2.12.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 12 Number reporting comfort.

2.13 Convenience of product

No significant difference in reported convenience of use was found by Moore 2013 (Analysis 2.13).

Analysis 2.13.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 13 Number reporting convenience of product.

2.14 Mean convenience of product

Sutherland 1996 reported on mean convenience of product finding no significant difference between groups (Analysis 2.14).

Analysis 2.14.

Comparison 2 Single‐ise (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 14 Mean convenience of product.

Comparison 03: Hydrophilic‐coated or a pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated)

Fifteen trials compared a hydrophilic‐coated catheter (activated or not activated) or a pre‐lubricated catheter with one or more other catheters (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated) (Cardenas 2009; Cardenas 2011; De Ridder 2005; Denys 2012, Fader 2001; Giannantoni 2001; Leriche 2006; Mauroy 2001; Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Pascoe 2001; Sarica 2010; Sutherland 1996; Vapnek 2003; Witjes 2009). (See Characteristics of included studies table for full description of catheters used).

3.1 Asymptomatic bacteruria

Only one trial reported asymptomatic bacteriuria (Pachler 1999). No significant difference was found between the arms (Analysis 3.1).

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 1 Number with asymptomatic bacteriuria.

3.2 Number with symptomatic UTI

Six trials reported the number of symptomatic UTI (Cardenas 2009; De Ridder 2005; Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Sutherland 1996; Vapnek 2003) (Analysis 3.2). The estimates from four of these trials (Cardenas 2011; Moore 2013; Pachler 1999; Sutherland 1996) had wide confidence intervals that straddled the no‐difference line.

Analysis 3.2.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 2 Number with symptomatic UTI.

In one study (Vapnek 2003), the risk ratio was not estimable due to the way the data were reported.

In the largest trial (De Ridder 2005), the authors reported on the incidence of UTI of all enrolled participants (N = 123), although the total number of UTIs was not reported. Only 57 participants (33/62 in the PVC arm; 25/61 in the hydrophilic arm) remained in the trial at the endpoint of 12 months and dropout was greater in the hydrophilic‐coated catheter arm. There were fewer patients with one or more UTI in the hydrophilic‐coated catheter group (i.e. results were better for the hydrophilic‐coated catheters) and this was marginally statistically significant (39 out of 61 versus 51 out of 62; RR 0.78; 95% CI 0.62 to 0.97).

We chose not to derive a summary estimate because of the heterogeneity amongst the trials and the problem of attrition bias.

3.3 Number of UTIs per month of use

One trial Cardenas 2011 reported the number of UTIs per month of use, with the hydrophilic arm showing 41/207 and the uncoated arm 76/349, which was not statistically significant (Analysis 3.3).

Analysis 3.3.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 3 Number of UTIs per month of use.

3.4 Number with urethral trauma/bleeding/macroscopic haematuria

Four trials reported on urethral trauma or visible bleeding. Cardenas 2011 noted a higher incidence in the hydrophilic cohort (14/105 versus 6/114) as did De Ridder 2005 (38/55 versus 32/59). One cross‐over trial reported 0/29 events in the hydrophilic arm and 5/29 in the standard arm (Leriche 2006). Pachler 1999 found no difference between groups. The combined data provided a confidence interval that straddled the no‐difference line (Analysis 3.4).

Analysis 3.4.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 4 Number with urethral trauma/bleeding/macroscopic haematuria.

3.5 Number with microscopic haematuria

Sutherland 1996 reported fewer cases of microscopic haematuria in the coated group (6/16 versus 11/14) (Analysis 3.5).

Analysis 3.5.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 5 Number with microscopic haematuria.

3.6 Mean microscopic haematuria

Moore 2013 reported on mean number of events of microscopic haematuria, finding no significant difference (Analysis 3.6).

Analysis 3.6.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 6 Mean microscopic haematuria.

3.7 Number with stricture formation

One event occurred in the coated group of the De Ridder trial (De Ridder 2005) (Analysis 3.7).

Analysis 3.7.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 7 Number with stricture formation.

3.8 Overall satisfaction

Three trials addressed overall satisfaction with a hydrophilic product compared with another (De Ridder 2005; Moore 2013; Witjes 2009) (Analysis 3.8). One study (De Ridder 2005) reported higher satisfaction with the hydrophilic catheter; whereas another (Moore 2013) reported slightly higher satisfaction with the uncoated catheter. One study (Witjes 2009) compared two hydrophilic products, one PVC‐based the other PVC‐free and found that satisfaction was higher (statistically significant P = 0.02) with the PVC‐based product.

Analysis 3.8.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 8 Number reporting overall satisfaction.

3.9 Mean overall satisfaction

Cardenas 2011 and Sutherland 1996 reported statistically significant differences for users of the hydrophilic product over the uncoated catheter; Leriche 2006 also reported statistically significant differences in favour of hydrophilic catheter over uncoated, pre‐lubricated catheter (Analysis 3.9). However, there was an imbalance in attrition in the Cardenas 2011 study, which meant that fewer patients have reported on preference in the hydrophilic arm. Those who did not remain in the study may have been less satisfied with the hydrophilic catheter than those who completed the study.

Analysis 3.9.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 9 Mean Overall satisfaction.

3.10 Number reporting preference

Three trials (De Ridder 2005; Leriche 2006; Pachler 1999) indicated that the hydrophilic product was preferred over the uncoated catheter. These differences were not statistically significant (Analysis 3.10).

Analysis 3.10.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 10 Number reporting preference.

3.11 Number reporting convenience of product

One cross‐over trial (Moore 2013) found no significant difference between the two arms (Analysis 3.11).

Analysis 3.11.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 11 Number reporting convenience of product.

3.12 Mean convenience of product

Sutherland 1996 reported on mean convenience of product, which did not vary significantly between products (Analysis 3.12).

Analysis 3.12.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 12 Mean convenience of product.

3.13 Number reporting ease of handling

Thirty‐one out of 32 participants in the Pachler 1999 two‐arm cross‐over trial reported handling the catheter to be either easy or tolerable in both arms (Analysis 3.13). In Moore 2013, ease of handling was acceptable in both groups with a trend favouring the uncoated catheter (29/49 hydrophilic group and 46/48 in the uncoated arm).

Analysis 3.13.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 13 Number reporting ease of handling.

3.14 Mean ease of handling

Sutherland 1996 reported no significant difference in mean ease of handling (Analysis 3.14).

Analysis 3.14.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 14 Mean ease of handling.

3.15 Number reporting ease of insertion

One RCT (Witjes 2009) and two cross‐over trials (Leriche 2006; Pachler 1999) reported on ease of insertion. No significant difference was found (Analysis 3.15).

Analysis 3.15.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 15 Number reporting ease of insertion.

3.16 Mean ease of insertion

Cardenas 2011 and Sutherland 1996 reported on mean ease of insertion; no significant difference was found (Analysis 3.16).

Analysis 3.16.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 16 Mean ease of insertion.

3.17 Mean ease of removal

Cardenas 2011 found that mean ease of removal did not vary significantly between groups (Analysis 3.17).

Analysis 3.17.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 17 Number reporting comfort.

3.18 Number reporting comfort

Moore 2013 found no significant difference in numbers reporting product comfort (Analysis 3.18).

Analysis 3.18.

Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or other pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated), Outcome 18 Mean ease of removal.

Studies without data added

Six cross‐over trials (Fader 2001, Mauroy 2001, Pascoe 2001, Sarica 2010, Denys 2012, Giannantoni 2001) compared one hydrophilic‐coated catheter with one or more catheters (coated or uncoated), but did not provide data in a format that could be included in the data tables.

A key finding in Fader 2001, involving 61 participants, was that there were significant differences between four hydrophilic products (not activated, water added by user) with respect to user‐reported severity of sticking and discomfort on withdrawal, user‐reported satisfaction and ease of use.

Mauroy 2001 reported on infection, haematuria, user‐reported satisfaction and ease of use among 27 participants, but did not find any significant differences between the three hydrophilic (not activated, water added by user) products tested.

Pascoe 2001 randomised 27 participants to test two hydrophilic‐coated catheters, one activated and one not activated (water added by user), and found no significant differences in performance, but users expressed a preference for the activated catheter.

Sarica 2010 compared the use of three catheters, one uncoated (not lubricated), one pre‐lubricated with integrated bag and one hydrophilic‐coated (water added by user), and reported an advantage in the pre‐lubricated catheter for reduction in microscopic haematuria and improved comfort and handling. Only 10 of the 25 participants randomised completed the trial.

In Denys 2012, 97 participants completed a comparison of a new hydrophilic‐coated catheter (not activated, sterile water supplied) versus a hydrophilic catheter (water added by user). Although a cross‐over trial was undertaken, data on the control catheter were reported at baseline, but no further data on this group were reported.

Giannantoni 2001, a cross‐over trial with 18 participants, compared a pre‐lubricated catheter with protective sleeve versus an uncoated, non‐lubricated catheter (water added by user). The outcomes were UTI, asymptomatic bacteriuria and participant preference; however as UTI and asymptomatic bacteriuria findings were reported per sample not per participant, it was not possible to include the data. The pre‐lubricated catheter scored significantly better for comfort and ease of use.

Comparison 4. One catheter length versus another catheter length

Five two‐arm cross‐over trials compared a shorter catheter length with a standard catheter (Biering‐Sorensen 2007; Chartier‐Kastler 2011; Chartier‐Kastler 2013; Costa 2013; Domurath 2011). Chartier‐Kastler 2011 and Domurath 2011 compared hydrophilic‐coated catheters (activated) in both arms. In Biering‐Sorensen 2007 and Chartier‐Kastler 2013 the shorter catheter was hydrophilic‐coated (activated) and the standard catheters were various designs. Costa 2013 evaluated uncoated, pre‐lubricated catheters (closed system with integrated collection bag) in both arms, the only difference being standard (40 cm) versus shorter (30 cm) length. All but one trial tested the catheters on male participants, Biering‐Sorensen 2007 had female only participants. Participants in Biering‐Sorensen 2007, Chartier‐Kastler 2011; Chartier‐Kastler 2013 and Domurath 2011 had either spinal cord injuries or lesions, and those in Costa 2013 were paraplegics requiring wheelchairs for mobility.

One study (Chartier‐Kastler 2013) used a validated tool, the Intermittent Self‐Catheterisation Questionnaire (ISC‐Q) (Pinder 2012), reporting that more participants favoured the shorter catheter, however, only the difference in the total ISC‐Q scores was reported, not each of the four domain scores (see Discussion section).

4.1 Number reporting ease of handling

Chartier‐Kastler 2011, Costa 2013 and Domurath 2011 reported on ease of handling (Analysis 4.1). Results were mixed, with Chartier‐Kastler 2011 and Domurath 2011 reporting a preference for the shorter catheter, whereas participants in the Costa 2013 trial favoured the standard length catheter.

Analysis 4.1.

Comparison 4 Standard catheter versus shorter catheter length, Outcome 1 Number reporting ease of handling.

4.2 Number reporting ease of insertion

Both Chartier‐Kastler 2011 and Domurath 2011 found more participants reported either positively or neutrally for ease of insertion for the shorter catheter compared to the standard catheter (28 out of 30 versus 22 out of 30 and 33 out of 36 versus 30 out of 36 respectively) and that a higher number of participants rated the shorter catheter as discrete or neutral compared to the standard catheter (34 out of 36 compared to 28 out of 36 and 28 out of 30 compared to 17 out of 30 respectively) (Analysis 4.2).

Analysis 4.2.

Comparison 4 Standard catheter versus shorter catheter length, Outcome 2 Number reporting ease of insertion.

4.3 Number reporting product discretion

Chartier‐Kastler 2011 and Domurath 2011 reported on product discretion reporting that significantly more participants found the shorter product more discrete (Analysis 4.3).

Analysis 4.3.

Comparison 4 Standard catheter versus shorter catheter length, Outcome 3 Number reporting product discretion.

4.4 Number reporting preference

Domurath 2011, Costa 2013, Chartier‐Kastler 2013 and Biering‐Sorensen 2007 reported on user preference. Domurath 2011, Chartier‐Kastler 2013 and Biering‐Sorensen 2007 found in favour of the shorter catheter, but confidence intervals crossed the no‐difference line. However, Costa 2013 found that very few participants preferred the shorter catheter (seven out of 81) (Analysis 4.4).

Analysis 4.4.

Comparison 4 Standard catheter versus shorter catheter length, Outcome 4 Number reporting preference.

Comparison 5. Any other techniques, strategies or designs that influence UTI, other complications or satisfaction in adults and children using intermittent catheterisation for incomplete bladder emptying.

No randomised clinical trials that tested different cleaning methods and reported catheter‐associated infection were found.

One RCT (Fera 2002) and one cross‐over trial (Taweesangsuksalul 2005) were found which compared different gels used for lubricating catheters before insertion.

Fera 2002 compared gentamycin gel (0.1%) versus lidocaine gel (2%). There were 10 participants per arm and each used their allocated gel for four months. Urine analysis took place once every three weeks during the trial (a total of five samples for each participant). No significant difference was found in either the number of symptomatic UTIs or in occurrence of asymptomatic bacteriuria. Findings were potentially confounded due to four participants allocated to the lidocaine gel group receiving prophylactic antibiotics during the trial. Furthermore, two participants in the lidocaine group and one participant in the gentamycin group were treated for UTI during the trial and were taken out of the trial and returned following treatment.

Taweesangsuksalul 2005 compared participant satisfaction with Aloe vera gel versus an aqueous gel for lubricating the catheter before insertion. Ten participants used both lubricants and no significant difference was reported. It was not possible to include data as the satisfaction scale used was not reported.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The purpose of the current review was to compare catheter designs, materials, technique and any other strategies to reduce UTI in long‐term intermittent catheterisation (IC) users. A secondary aim was to compare user‐reported outcomes (user satisfaction, preference, ease of use) associated with various catheter designs, techniques, and materials. Despite an additional 17 trials added to the database for a current total of 31 trials, there remains an absence of robust evidence to support one product or technique over another with respect to control of clinical symptoms, particularly symptomatic UTI. There is some statistical support for user preference of hydrophilic catheters but the confidence intervals are wide and there is a risk of bias due to higher dropout in the intervention arms. Thus the available data do not provide sufficient guidance to prescribing clinicians or users on which technique (aseptic/clean); catheter type (coated/uncoated); method (single/multiple‐use); person catheterising (self/other); or any other strategy is better than another. Clinicians will need to base their decisions on clinical judgement in conjunction with users. Differential costs of catheters/techniques may also inform decision‐making.

Updates since the last review

The previous review (Moore 2007) found no convincing evidence that any specific technique, catheter design, method, person, or strategy was better than any other to minimise risk of UTI and other complications. The focus of that review was incidence of UTI related to IC. Our focus for the 2014 review expanded to include user‐reported outcome data. This meant that two studies that had user preference as an outcome and that did not meet the inclusion criteria for the 2007 review were added to this review. Moreover, in the 2007 review, data reported in three cross‐over trials were not included in the meta‐analysis. In the current review we have been able to include data from cross‐over trials, resulting in 12 additional trials (nine new and three from the previous review). However, data from the three cross‐over trials with more than two arms has been discussed in the narrative, not added to the meta‐analysis. Despite this number, there remains a lack of evidence that one catheter design or technique is superior to another in terms of control of symptomatic UTI.

Overall completeness and applicability

The number of potential permutations and combinations of techniques and catheters has led to problems with confounding, with several trials combining catheters and techniques such that it would not be possible to state the cause of any differences found. Large RCTs are needed to provide answers to each separate question (aseptic or clean technique; coated or uncoated catheter; single or multiple use, catheterisation by self or others). But because these trials are difficult to conduct and some combinations are much more commonly used than others, prioritisation is important. For example, aseptic versus clean technique question is of relatively low importance because in community settings (where most IC takes place) an aseptic technique is not practical. In hospital settings infection control policies indicate that an aseptic technique would be needed for safety.

A key clinical question remains the influence of catheters on UTI. The difficulty of establishing robust outcome measures of UTI remains problematic. Bacteriuria/positive culture is not clinically relevant unless accompanied by symptoms but the symptoms themselves may present in vague and imprecise ways, especially in adults with spinal cord injury where symptoms may be masked or unclear. However, despite these limitations symptomatic UTI remains the most clinically important primary outcome variable.

Men and women were not equally represented, limiting generalisability of results. Of the 29 trials that reported gender, there was a higher proportion of males (60%) enrolling in the trial, the majority of whom had spinal cord injury. Thirteen trials enrolled only men, whereas one trial enrolled only women.

In community settings there are two important questions: single versus multiple‐use; and coated versus uncoated catheter. In practice the most commonly used single‐use catheter is a coated catheter which would need to be compared with a single‐use uncoated catheter, to test if the coating is of importance. If coated catheters are not found to be superior then multiple‐use uncoated catheters need to be compared with single‐use uncoated catheters (to test if the sterility or single‐use of the catheter is of importance). The latter question is of highest importance because it has the most substantial cost implications. Although coated catheters are more expensive than uncoated catheters, it is the single‐use of the catheters (coated or uncoated) which makes this method of higher cost to individuals and health services.

There have been no RCTs comparing catheterisation by self compared with others. Moore (Moore 1993) presented descriptive data suggesting that there was no difference between the child self‐catheterising versus the parent. This question is of relatively low priority because catheterisation by others usually only takes place when the individual is not able to carry out the procedure themselves.

No RCTs comparing different methods of catheter cleaning were found when undertaking this review. We found a number of laboratory trials testing the sterility of catheters using different methods (cleaning with soap and water, chemical disinfection and microwave). Although most trials showed that pathogenic organisms were removed by cleaning, one trial testing the microwave method and one (incidentally) the soap and water method found residual pathogenic organisms. The clinical significance of these findings is unknown. The microwave method may be less practical than other methods due to the risk of catheter melting. No randomised controlled clinical trials of cleaning methods have been published and the comparative effectiveness of cleaning methods is therefore unknown.

Potential biases

1. Attrition: In three of the five larger trials of long duration (Cardenas 2011; De Ridder 2005; Moore 2013) dropouts occurred early and were more frequent in the treatment arm, thus resulting in an imbalance and a potential bias in favour of the treatment catheter because there were fewer long‐term data. In De Ridder 2005, only 53% of the standard (uncoated) catheter participants and 41% of the treatment (hydrophilic‐coated) catheter participants remained at the 12‐month study endpoint. Similar challenges were met by Cardenas 2011 with 60% of participants remaining in the standard (uncoated) arm and 43% in the treatment (hydrophilic‐coated) arm. Moore 2013 also reported a completion rate of 75% in the standard (uncoated) arm and 62% in the treatment (coated) arm. Reasons for dropouts in all three trials included loss to follow‐up, preference for one study product, adverse events and withdrawing consent and improvement in voiding function as spinal cord injury healed. In Cardenas 2011 and De Ridder 2005, change in voiding status meant that some participants no longer required on‐going IC.

It should be noted that in all three trials, the uncoated group had a higher proportion of participant completions at the final analysis. Future trialists will require funds to support long‐term and multicentre ventures that take into account the attrition challenges and the populations to be studied. Newly injured spinal cord individuals are attractive participants as their bladders are 'naive' to the long‐term consequences of catheterisation. However, their bladder/voiding status can be unpredictable and may change to spontaneous voiding as healing occurs. Community dwelling users of ICs such as those with myelomeningocoele or multiple sclerosis are an alternative population as their conditions are relatively stable but their catheterisation habits are less easy to control and follow‐up can be an issue.

2. Intention to treat (ITT): ITT analysis was declared by only two parallel arm trials (Moore 2006 and Witjes 2009).

3. Assessment of user‐reported outcomes: 15 trials had user‐reported outcomes, 14 of which used questions that had not undergone standard psychometric testing and validation. Chartier‐Kastler 2013 was the first trial to apply a newly developed and validated 24‐item Intermittent Self‐Catheterisation Questionnaire (ISC‐Q), which evaluates aspects of quality of life specific to the needs of individuals performing ISC (Pinder 2012). The tool has four domains (ease of use, discreetness, convenience and psychological well‐being) and a total score, although Chartier‐Kastler 2013 only reported the total score.

In this review the most frequently reported outcome measures related to ease of use, with nine studies reporting ease of insertion and seven reporting ease of handling. Fewer studies reported outcomes relating to discreetness and convenience. Future studies would benefit from adopting a more consistent approach to the measurement of user‐reported outcomes in assessing the benefit of one IC product over another.

4. There is a theoretical bias in cross‐over trials where individuals will score the first product more favourably than the second. Chartier‐Kastler 2013 was the only trial statistically addressing treatment sequence and reported no significant difference in scores.

Reporting standards

Reporting standards varied and not all trials followed the Consort guidelines, making it difficult to extract data. In those that followed good reporting standards, adverse events such as haematuria were clearly attributed to one of the trial arms.

Agreement or disagreement with other reviews

Two reviews have been published on the occurrence of UTI in IC users (Bermingham 2013; Li 2013). Bermingham et al created a Markov model to predict cost utility and QALY (quality‐adjusted life year), using data from the randomised trials on IC. The authors conclude that multiple use is the most cost‐effective type of IC. The authors also concluded, as we have, that there was limited evidence to support one catheter product over another with respect to symptomatic UTI. Of note is their conclusion that patients should be offered a choice between gel reservoir or hydrophilic catheters. Our review found no evidence to support this statement but we do agree with Bermingham et al that there is inadequate evidence to state that incidence of symptomatic UTI is affected by any one catheter design. The second review (Li 2013) also sought to examine the benefit of one catheter design (hydrophilic versus non‐hydrophilic) in the occurrence of UTI and haematuria. The authors concluded that both UTI and haematuria occurred less frequently with the use of hydrophilic‐coated catheters. The authors’ findings are not supported by our review. We suggest this may be related to the authors' errors of data extraction and interpretation including mistaking proportions for raw data in a forest plot, mixing laboratory trials (Stensballe 2005) with clinical trials, incorrect reporting of attrition leading to misleading conclusions, and finally, not reporting bleeding occurrences as well as microhaematuria which is worse in hydrophilic‐coated arms where reported. Thus we disagree with the findings of the Li et al review that hydrophilic catheters reduce symptomatic urinary tract infections and reduce haematuria.

Authors' conclusions

There is still no convincing evidence that incidence of UTI is affected by use of aseptic or clean technique, coated or uncoated catheters, single (sterile) or multiple‐use (clean) catheters or by any other strategy and user‐reported outcomes varied. The question of whether healthcare providers should cover the cost of single‐use products requires debate if no benefit over multiple‐use products can be demonstrated. The variability in user‐reported outcomes suggests patient choice could be important and there may be a benefit in combining single‐ and multiple‐use for an individual.

There is lack of evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of any particular catheter design, technique or strategy. Variations in clinical practice and growth in the use of single‐use catheters (particularly coated catheters) with associated increased costs mean that large well‐designed parallel group RCTs are needed. RCTs are difficult in this area and prioritisation is necessary.

The most important pragmatic question (both for clinical and cost‐effective reasons) is: Are multiple‐use catheters equivalent to single‐use catheters?

We recommend that the NIDRR 1992 definition of UTI is used as the primary outcome variable (positive urine culture with pyuria and one or more systemic symptoms (fever, loin pain, dysuria, urgency, haematuria). However, there is a need to validate these symptoms on IC users.

We recommend that a validated tool (e.g. Pinder 2012) is used to measure user acceptability.

Given the large differential costs for the methods, cost‐effectiveness will need to be assessed rigorously.

To assist cost‐effectiveness assessment, we recommend that user‐reported outcomes and health state utility are measured for different situations (e.g. home/out) as a secondary outcome variable. A validated outcome tool is required to allow comparisons across trials.

Feedback

Feedback from Professor Dr Andrei Krassioukov and colleagues, 8 August 2017

Summary

Our team that includes clinicians and scientists from Belgium, Canada, United States and Switzerland involved in rehabilitation and medical management of individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) would like to ask your opinion and help to address the following issue.During the last few years, the international community engaged in strong debates on issues related to urinary tract infection and re‐use of catheters during the management of neurogenic bladder among individuals with SCI.

In this respect, this review became one of the leading documents that captured mind and attention of clinicians around the world. Although numerous countries completely switched to single‐use catheters as guidelines for management of individuals with SCI, the opinion that was expressed in the above‐mentioned review has the potential to make a significant negative impact on the future management of individuals with SCI.

Upon closer inspection of this review we have become concerned about data that has been presented as well as conclusions drawn by the authors. We are reaching out to you to make you aware of our findings and interpretation of the studies that authors of the ‘Intermittent catheterisation for long‐term bladder management” Prieto et al 2014 included and discussed in their review. We are seeking your advice and guidance on how we can proceed with this information.

We have identified three main concerns with this Cochrane review that was conducted by Prieto and co‐investigators (Prieto 2014):

First, upon close inspection it appears that there are discrepancies in data extraction. For example, in ‘Analysis 2.2 Comparison 2 Single‐use (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 2 Number with symptomatic UTI’ of eight data sets, six (Sutherland 1996, Leek 2013, Moore 2013, Duffy 1995, King 1992 and Prieto‐Fingerhut 1999) are inconsistent with data reported by original authors. Similar discrepancies are noted throughout analyses in the review. At times, it appears data has simply been displaced (for example King 1992: data for single‐use catheter and data for multiple‐use catheter must be swapped) and at times it appears data has been extracted differently than we would expect (for example Leek 2013: one arm of the cross over trial was reported instead of both arms). Additionally, an abstract referenced (Moore 2013) provided data in a form that could not be extracted (person‐weeks).

Secondly, although the review was published in 2014, the definition of symptomatic UTI was taken from the NIDRR 1992 statement in ‘The Prevention and Management of Urinary Tract Infections Among People with Spinal Cord Injuries’. At that time, there were other more current definitions available such as the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) 2009 Guidelines which comprehensively covers definitions of catheter associated urinary tract infections and is significantly different from the NIDRR 1992 definition. In addition, the authors of this Cochrane review chose to accept each study’s definition of symptomatic UTI, despite none of the studies using a definition consistent with current standards. As a result, heterogeneous and inappropriate definitions of symptomatic UTI were included in analysis.

Finally, we feel clarification regarding the Analyses 1.1 through 4.4 (30 in total) may be required. 20 of the 39 analyses consist of only 1 study, which is inconsistent with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 which states “Meta‐analysis is the statistical combination of results from two or more separate studies”. There are also inconsistencies with providing subtotals and totals for a number of analyses. An example of such can be seen for ’Analysis 3.2 Comparison 3 Hydrophilic‐coated or a pre‐lubricated catheter versus other catheter (pre‐lubricated, coated or uncoated)’. The authors “chose not derive a summary of estimate because of heterogeneity amongst the trials and the problem of attrition bias” despite having similar issues in other analyses and continuing to derive a summary in those instances. Alternatively, for ‘Analysis 2.2 Comparison 2 Single‐use (sterile) catheter versus multiple‐use (clean) catheter, Outcome 2 Number with symptomatic UTI’ the authors state “We decided not to derive a summary estimate because of heterogeneity; however, there was no suggestion of a trend favoring either of the approaches.” (p. 13). They in fact derived both subtotal and total summaries and provided them (p 73‐74). A number of other analyses that do not include subtotals or totals do not provide a reason why they were not completed.