Abstract

Background

Haloperidol used alone is recommended to help calm situations of aggression or agitation for people with psychosis. It is widely accessible and may be the only antipsychotic medication available in limited‐resource areas.

Objectives

To examine whether haloperidol alone is an effective treatment for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation, wherein clinicians are required to intervene to prevent harm to self and others.

Search methods

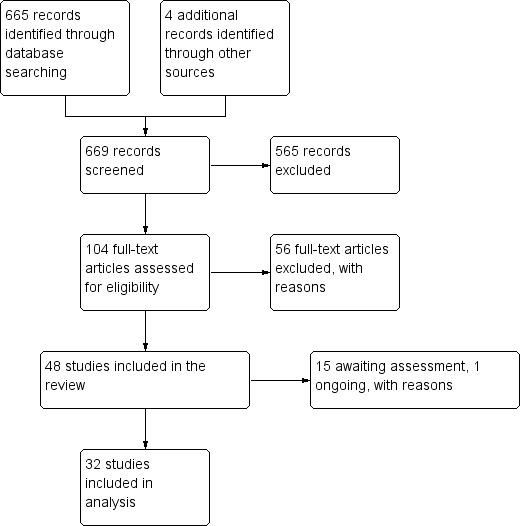

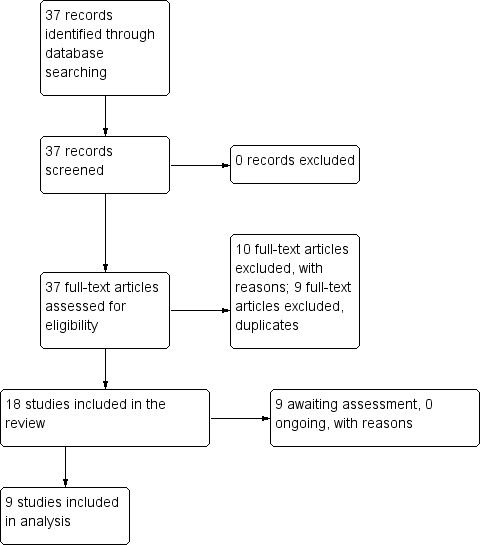

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Study‐Based Register of Trials (26th May 2016). This register is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (including AMED, BIOSIS CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and registries of clinical trials) and their monthly updates, handsearches, grey literature, and conference proceedings, with no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving people exhibiting aggression and/or agitation thought to be due to psychosis, allocated rapid use of haloperidol alone (by any route), compared with any other treatment. Outcomes of interest included tranquillisation or asleep by 30 minutes, repeated need for rapid tranquillisation within 24 hours, specific behaviours (threat or injury to others/self), adverse effects. We included trials meeting our selection criteria and providing useable data.

Data collection and analysis

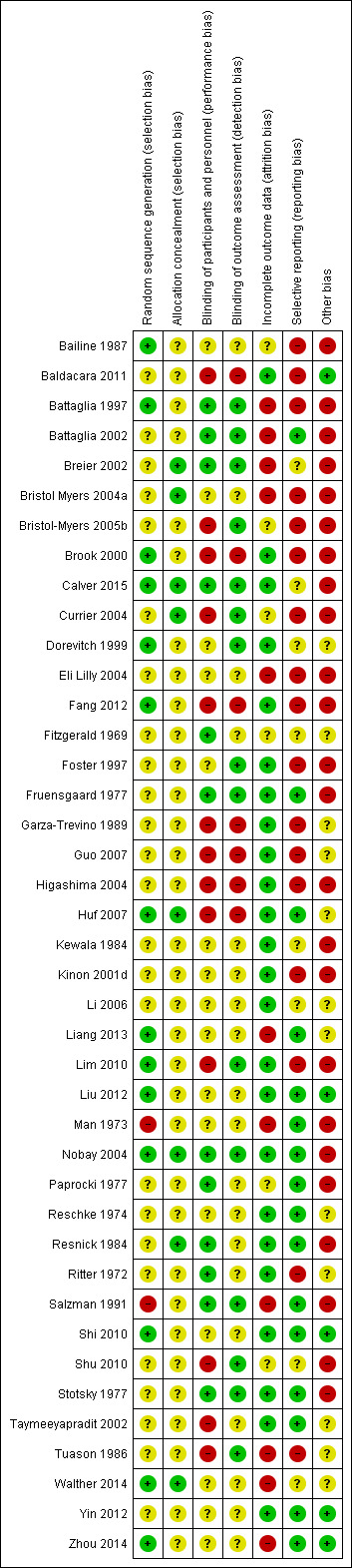

We independently inspected all citations from searches, identified relevant abstracts, and independently extracted data from all included studies. For binary data we calculated risk ratio (RR), for continuous data we calculated mean difference (MD), and for cognitive outcomes we derived standardised mean difference (SMD) effect sizes, all with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and using a fixed‐effect model. We assessed risk of bias for the included studies and used the GRADE approach to produce 'Summary of findings' tables which included our pre‐specified main outcomes of interest.

Main results

We found nine new RCTs from the 2016 update search, giving a total of 41 included studies and 24 comparisons. Few studies were undertaken in circumstances that reflect real‐world practice, and, with notable exceptions, most were small and carried considerable risk of bias. Due to the large number of comparisons, we can only present a summary of main results.

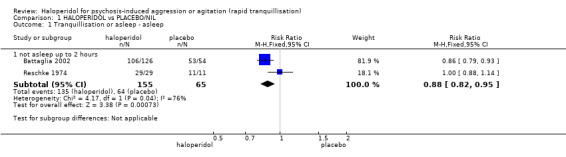

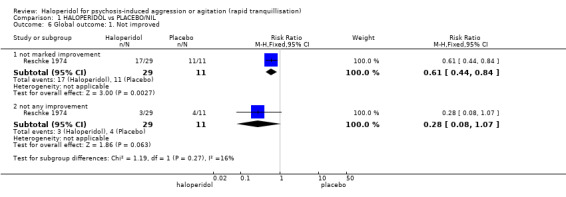

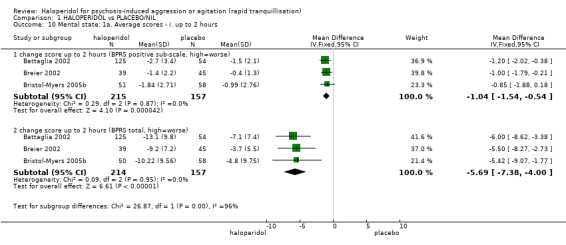

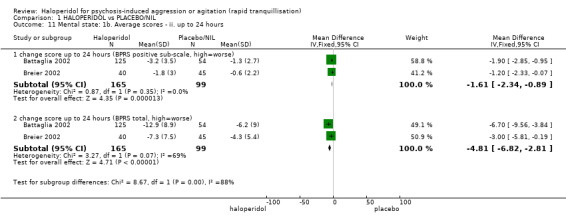

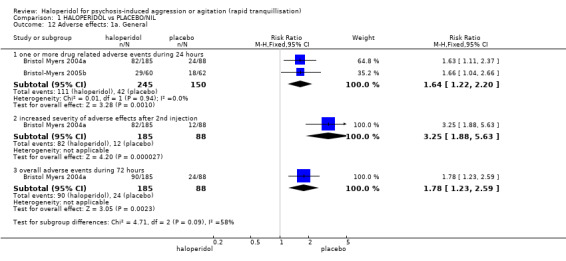

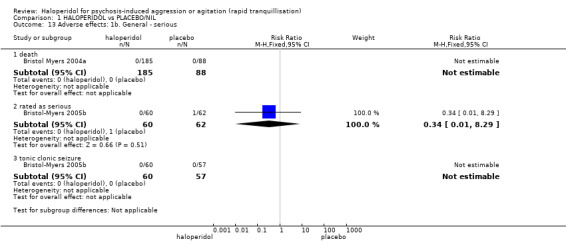

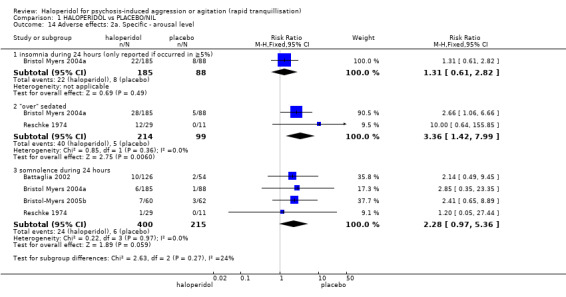

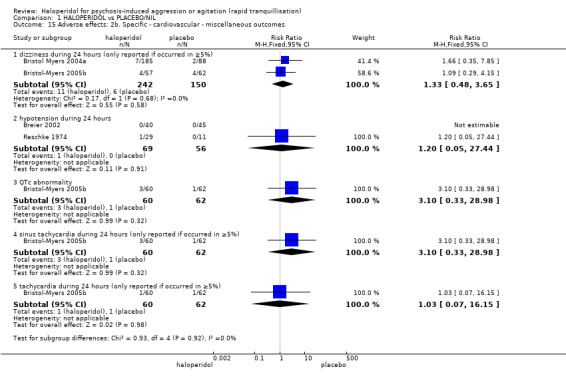

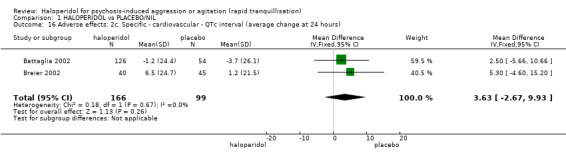

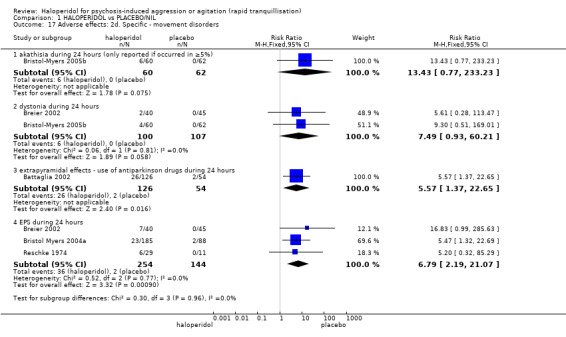

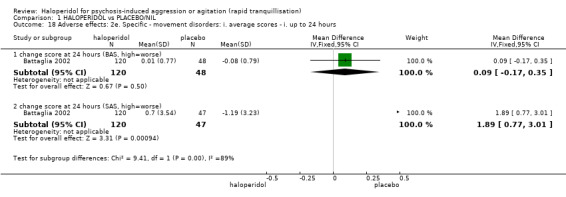

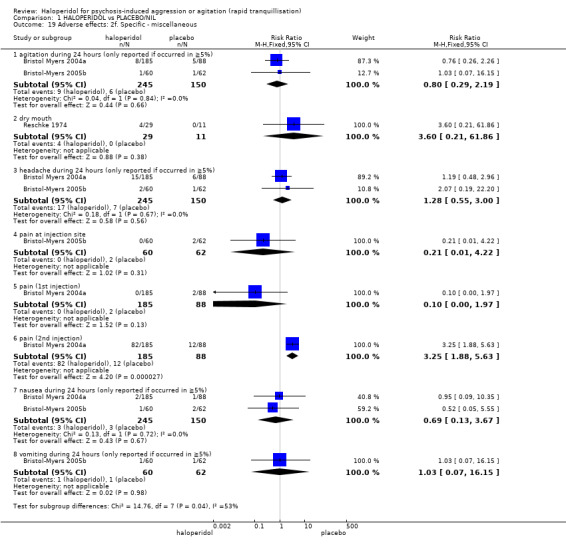

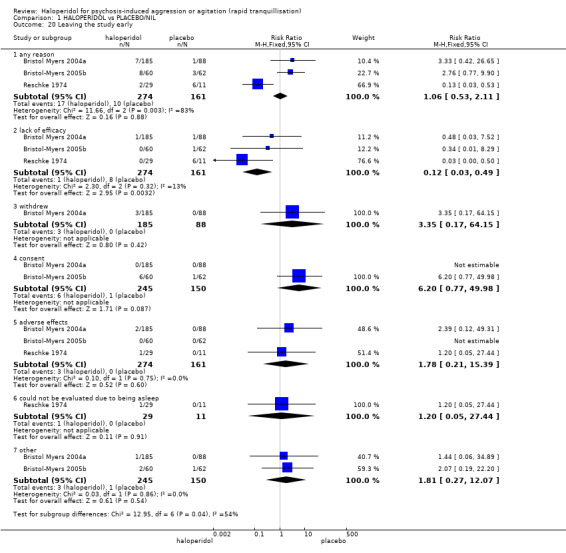

Compared with placebo, more people in the haloperidol group were asleep at two hours (2 RCTs, n=220, RR 0.88, 95%CI 0.82 to 0.95, very low‐quality evidence) and experienced dystonia (2 RCTs, n=207, RR 7.49, 95%CI 0.93 to 60.21, very low‐quality evidence).

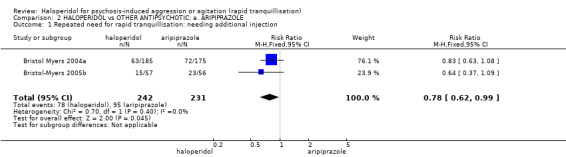

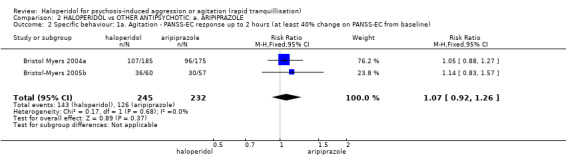

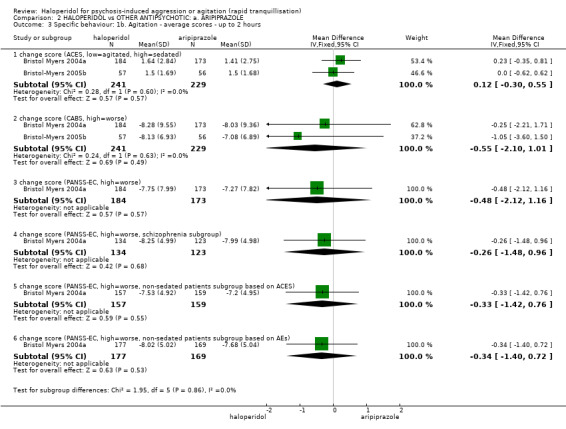

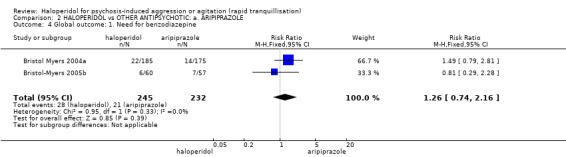

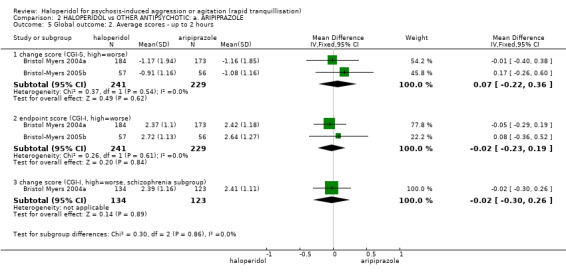

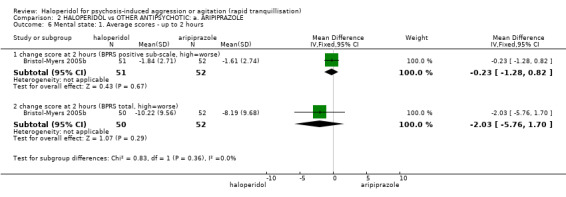

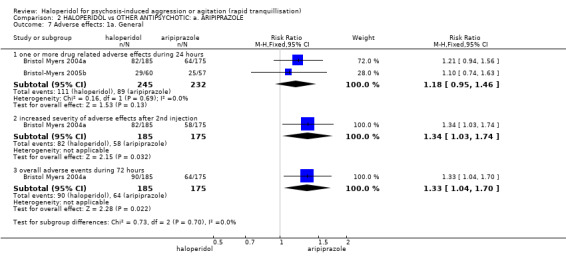

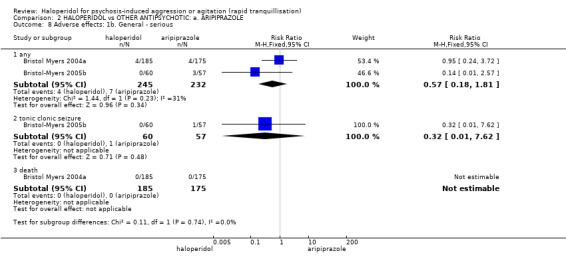

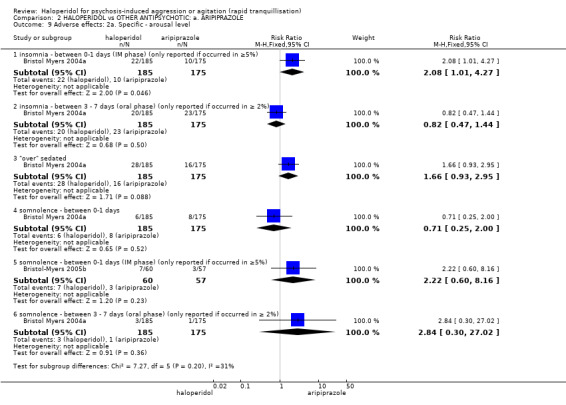

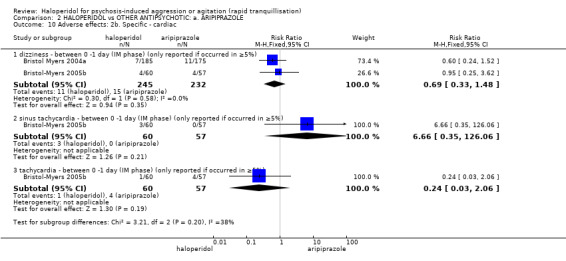

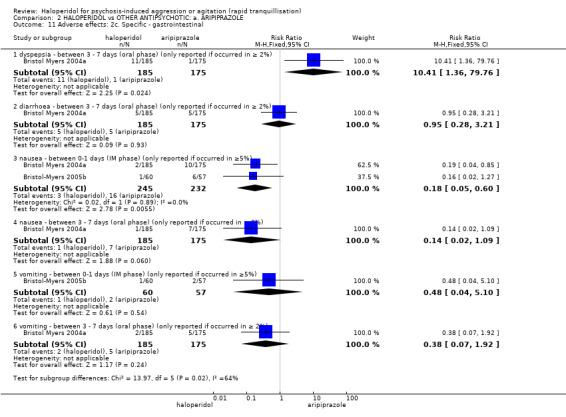

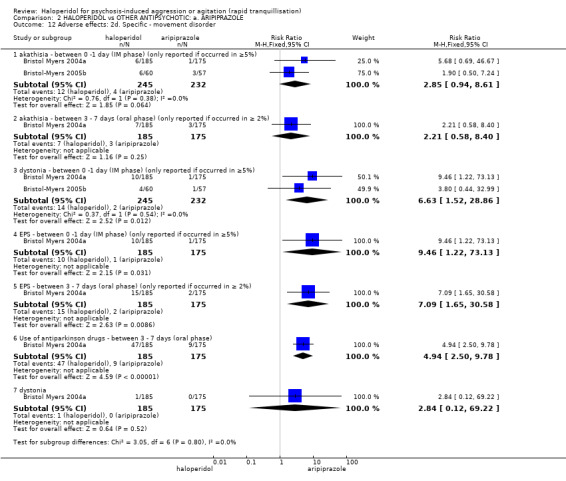

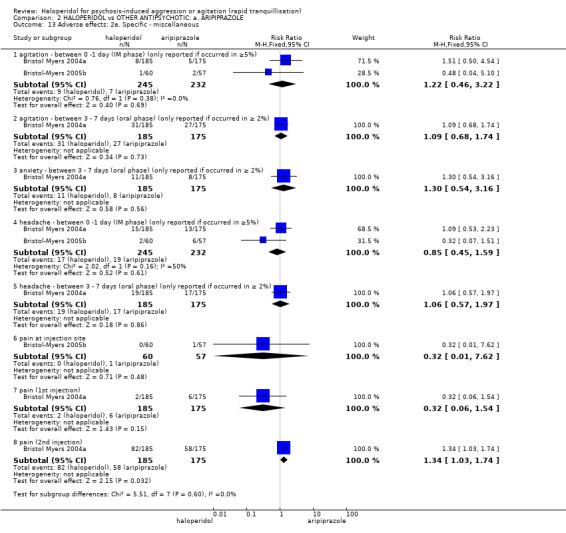

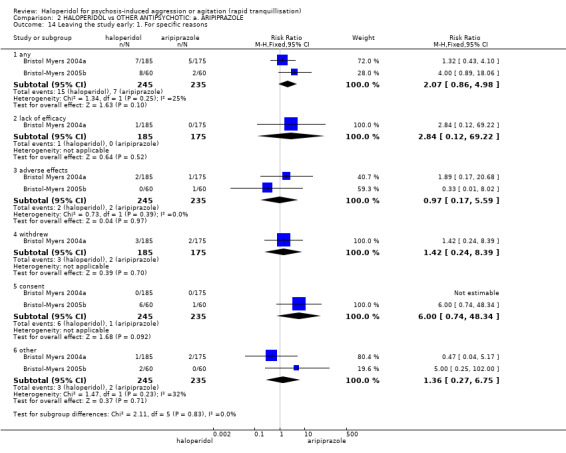

Compared with aripiprazole, people in the haloperidol group required fewer injections than those in the aripiprazole group (2 RCTs, n=473, RR 0.78, 95%CI 0.62 to 0.99, low‐quality evidence). More people in the haloperidol group experienced dystonia (2 RCTs, n=477, RR 6.63, 95%CI 1.52 to 28.86, very low‐quality evidence).

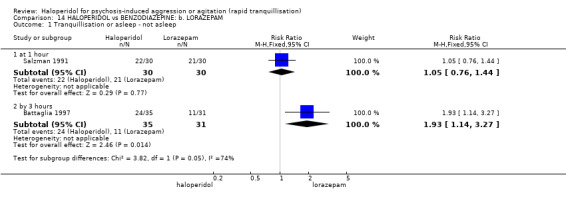

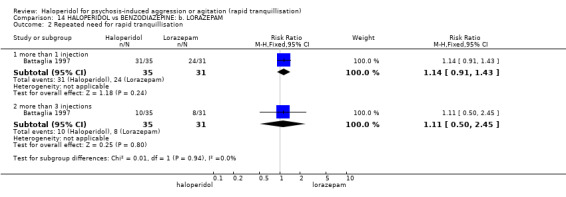

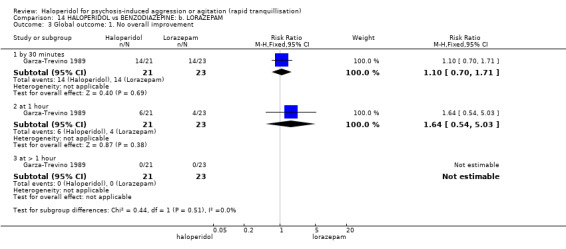

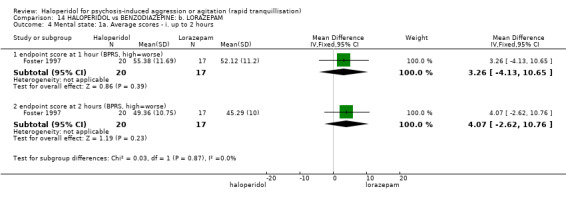

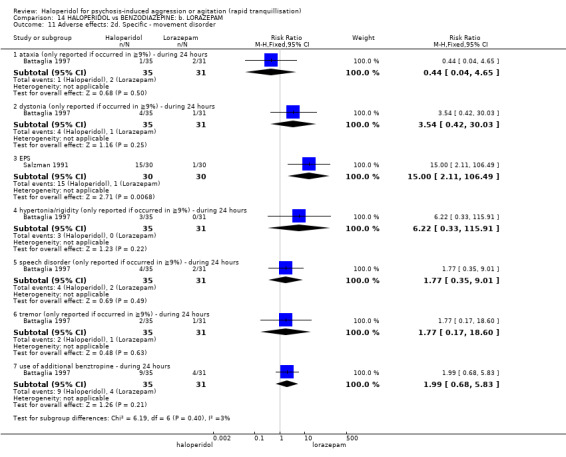

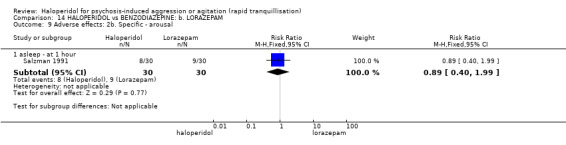

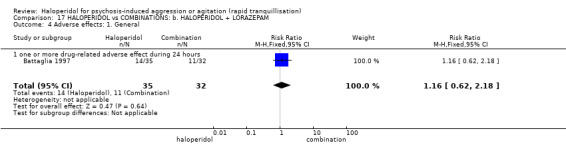

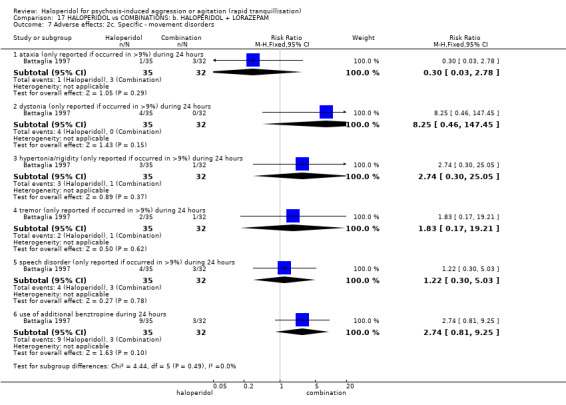

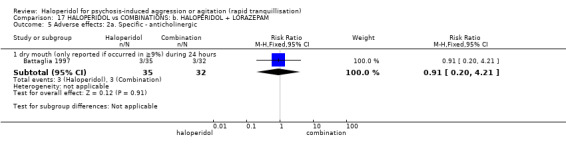

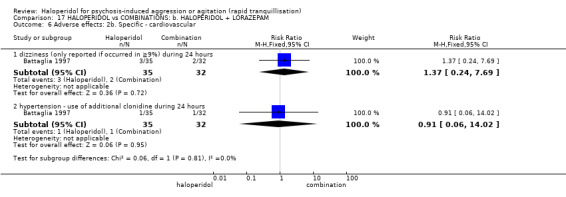

Four trials (n=207) compared haloperidol with lorazepam with no significant differences with regard to number of participants asleep at one hour (1 RCT, n=60, RR 1.05, 95%CI 0.76 to 1.44, very low‐quality of evidence) or those requiring additional injections (1 RCT, n=66, RR 1.14, 95%CI 0.91 to 1.43, very low‐quality of evidence).

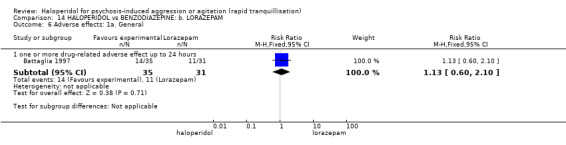

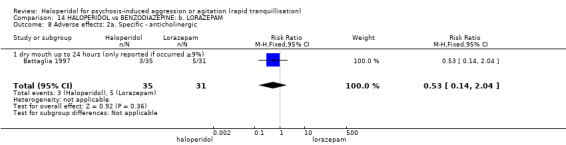

Haloperidol's adverse effects were not offset by addition of lorazepam (e.g. dystonia 1 RCT, n=67, RR 8.25, 95%CI 0.46 to 147.45, very low‐quality of evidence).

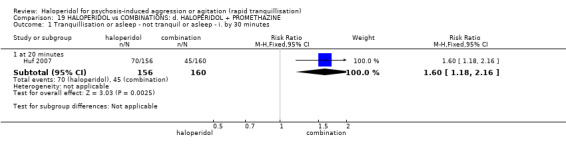

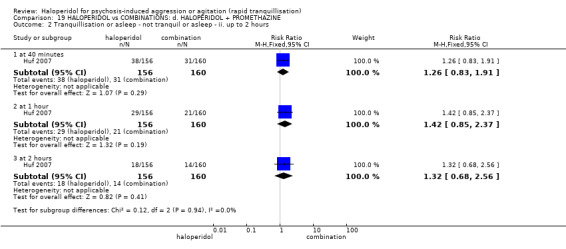

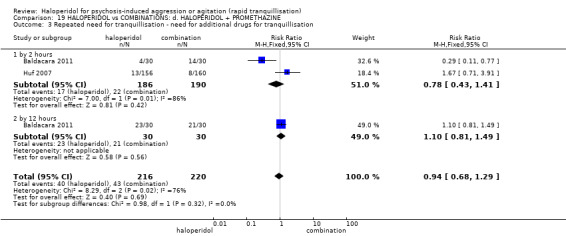

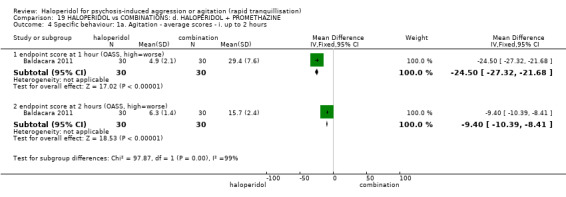

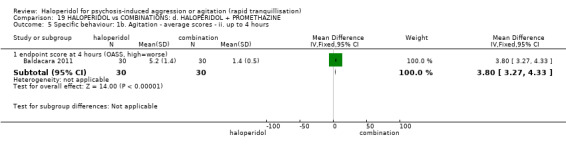

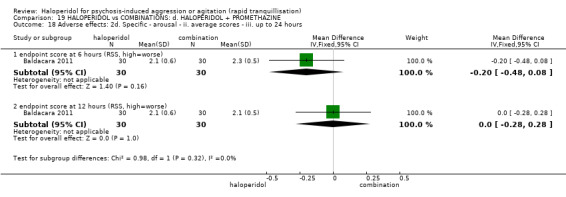

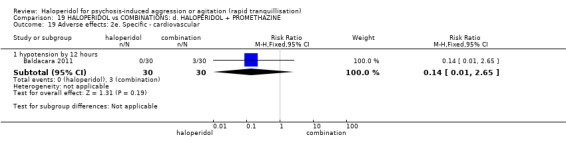

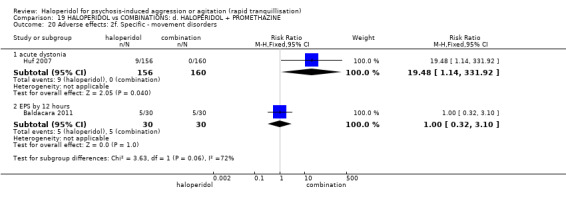

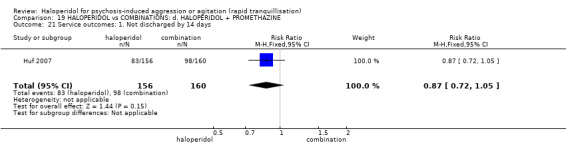

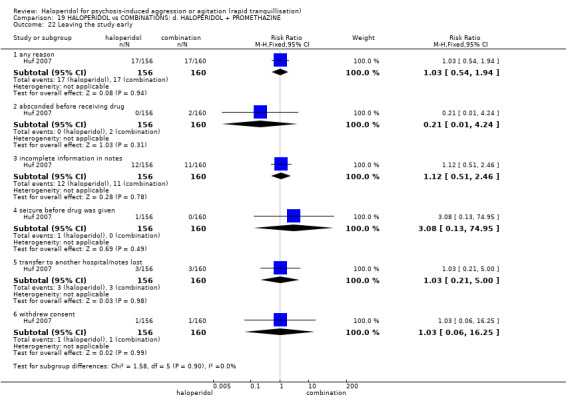

Addition of promethazine was investigated in two trials (n=376). More people in the haloperidol group were not tranquil or asleep by 20 minutes (1 RCT, n=316, RR 1.60, 95%CI 1.18 to 2.16, moderate‐quality evidence). Acute dystonia was too common in the haloperidol alone group for the trial to continue beyond the interim analysis (1 RCT, n=316, RR 19.48, 95%CI 1.14 to 331.92, low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Additional data from new studies does not alter previous conclusions of this review. If no other alternative exists, sole use of intramuscular haloperidol could be life‐saving. Where additional drugs are available, sole use of haloperidol for extreme emergency could be considered unethical. Addition of the sedating promethazine has support from better‐grade evidence from within randomised trials. Use of an alternative antipsychotic drug is only partially supported by fragmented and poor‐grade evidence. Adding a benzodiazepine to haloperidol does not have strong evidence of benefit and carries risk of additional harm.

After six decades of use for emergency rapid tranquillisation, this is still an area in need of good independent trials relevant to real‐world practice.

Plain language summary

Haloperidol as a means of calming people who are aggressive or agitated due to psychosis

Aim of review

This review looks at whether haloperidol is effective for treating people who are agitated and aggressive as a result of having psychosis.

Background

People with psychosis may experience hearing voices (hallucinations) or abnormal thoughts (delusions), which can make the person frightened, distressed and agitated (restless, excitable or irritable), leading sometimes to aggressive behaviour. This poses a significant challenge for mental health professionals, who have to quickly choose the best available treatment to prevent the risk of harm to both patient and/or others.

Haloperidol is a medication used for treating people with psychosis that can be taken by mouth or injected. As well as being an antipsychotic (preventing psychosis), it also calms people down or helps them to sleep.

Searches

In 2011 and 2016, the information specialist of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group searched their specialised register for randomised trials that looked at the effects of giving haloperidol compared with either placebo or other treatments to people who are aggressive or agitated because they were experiencing psychosis.

Results

Forty‐one studies are now included in the review but information in these is of low‐quality. Main results show that when compared with placebo or no treatment, more people having haloperidol were asleep after two hours. However, evidence is not strong. Results are made more complex by large variety of available treatments (24 comparisons).

Conclusions

The review authors conclude there is weak evidence that haloperidol calms people down and helps manage difficult situations. However, this is not based on good‐quality trails and therefore health professionals and people with mental health problems are left without clear evidence‐based guidance. In some situations, haloperidol may be the only choice, but this is far from ideal because although haloperidol is effective at calming people down it has side effects (e.g. restlessness, shaking of the head, hands and body, heart problems). These side effects can be just as distressing as psychosis and may act as a barrier that stops people coming back for future treatment. More research is needed to help people consider and understand which medication is better at calming people down; has fewer side effects; works quickly and rapidly; and can be used at lower dosages (or less frequent injections).

This plain language summary is based on a summary written by a consumer Ben Gray from Rethink.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. HALOPERIDOL compared to PLACEBO/NIL for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared with PLACEBO/NIL for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients; multi‐centre. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: PLACEBO/NIL | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| PLACEBO/NIL | HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep not asleep at 2 hours | Low1 | RR 0.88 (0.82 to 0.95) | 220 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 965 per 1000 | 849 per 1000 (791 to 917) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 980 per 1000 | 862 per 1000 (804 to 931) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 995 per 1000 | 876 per 1000 (816 to 945) | |||||

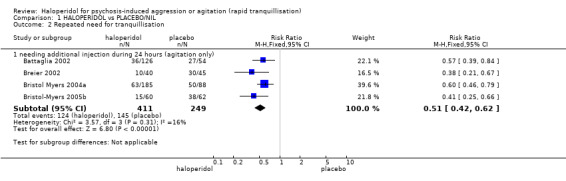

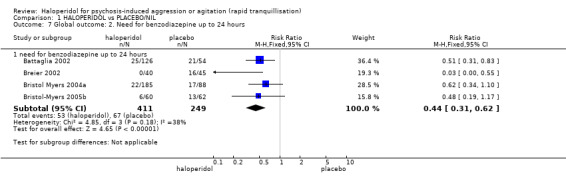

| Repeated need for tranquillisation needing additional injection within 24 hours | Low1 | RR 0.51 (0.42 to 0.62) | 660 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,4 | ||

| 400 per 1000 | 204 per 1000 (168 to 248) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 600 per 1000 | 306 per 1000 (252 to 372) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 800 per 1000 | 408 per 1000 (336 to 496) | |||||

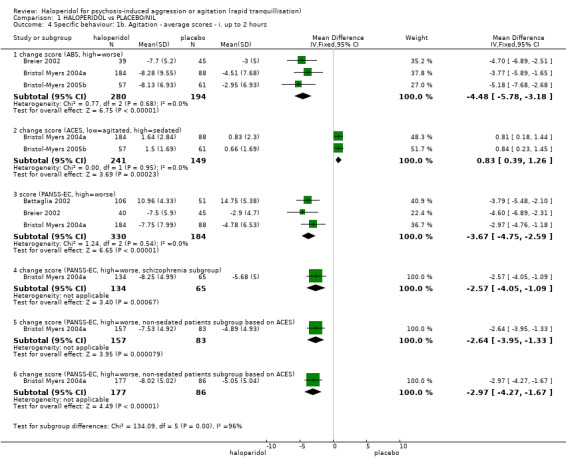

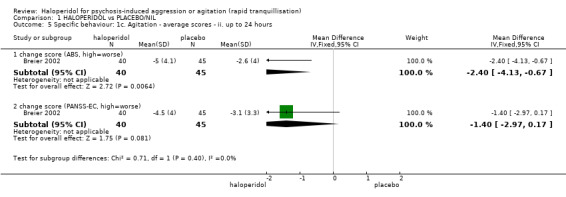

| Specific behaviour ‐ threat or injury to self or others average change score (ABS, high = worse) at 2 hours | The mean specific behaviour ‐ threat or injury to self or others in the intervention groups was 4.48 lower (5.78 to 3.18 lower) | 474 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,5 | |||

| Global outcome ‐ overall improvement (not any improvement) | Low1 | RR 0.28 (0.08 to 1.07) | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,6 | ||

| 200 per 1000 | 56 per 1000 (8 to 414) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 350 per 1000 | 98 per 1000 (14 to 724) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 500 per 1000 | 140 per 1000 (20 to 1000) | |||||

| Adverse effects: Specific ‐ dystonia within 24 hours | Moderate1 | RR 7.49 (0.93 to 60.21) | 207 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,6 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 10 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (9 to 602) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control risk ‐ moderate risk is roughly equal to that of the control group. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ method of randomisation not described, allocation concealment not stated, incomplete outcome data, sponsored by drug company. 3 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ no measure for tranquil or asleep at 30 minutes, therefore had to use not asleep at 2 hours. 4 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ sponsored by drug company. 5 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ not threat of injury to self or others, scale derived data. 6 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ 95% confidence interval is wide.

Summary of findings 2. HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: a. ARIPIPRAZOLE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared with OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS: a. ARIPIPRAZOLE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: multi‐centre. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS: a. ARIPIPRAZOLE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS: a. ARIPIPRAZOLE | HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

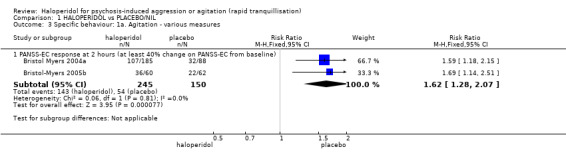

| Repeated need for rapid tranquillisation ‐ needing additional injection | Low1 | RR 0.78 (0.62 to 0.99) | 473 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| 200 per 1000 | 156 per 1000 (124 to 198) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 400 per 1000 | 312 per 1000 (248 to 396) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 650 per 1000 | 507 per 1000 (403 to 644) | |||||

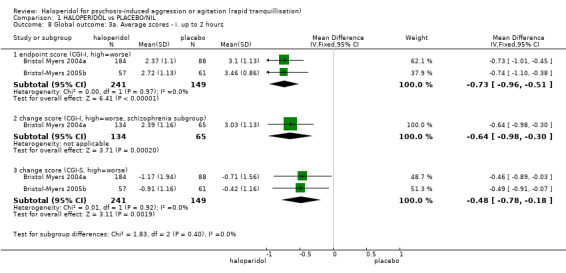

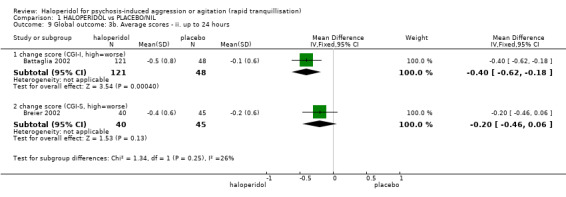

| Specific behaviours ‐ agitation: CABS average change score at 2 hours | The mean specific behaviours ‐ agitation: average change score at 2 hours in the intervention groups was 0.55 lower (2.10 lower to 1.01 higher) | 470 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,4 | |||

| Global outcomes: need for benzodiazepine 2 | Low1 | RR 1.26 (0.74 to 2.16) | 477 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,5 | ||

| 50 per 1000 | 63 per 1000 (37 to 108) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 126 per 1000 (74 to 216) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 252 per 1000 (148 to 432) | |||||

| Adverse effects: any serious, specific ‐ dystonia during 24 hours | Low6 | RR 6.63 (1.52 to 28.86) | 477 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,7,8 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Moderate6 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 332 per 1000 (76 to 1000) | |||||

| High6 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 663 per 1000 (152 to 1000) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Moderate risk roughly equates with that of the trial control group. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'severe' ‐ method of randomisation not described, possible that blinding was broken in Bristol Myers 2005, adverse effects only reported when reported by 5% of participants, sponsored by drug company. 3 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ sponsored by drug company. 4 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ scale‐derived data, not threat or injury to self or others as stated in protocol. 5 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ no measure for global outcome, overall improvement, therefore global improvement is inferred by need for benzodiazepine. 6 Low risk equates with that of trial control group. 7 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ method of randomisation not described, incomplete outcome data, adverse effects only reported when reported by at least 5% of participants, sponsored by drug company. 8 Imprecision: rated 'very serious' ‐ 95% confidence intervals are wide.

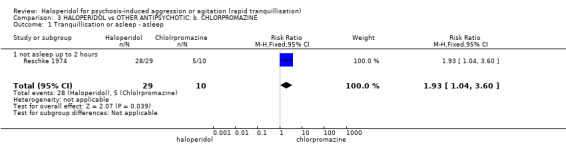

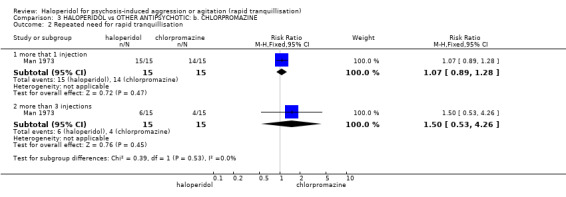

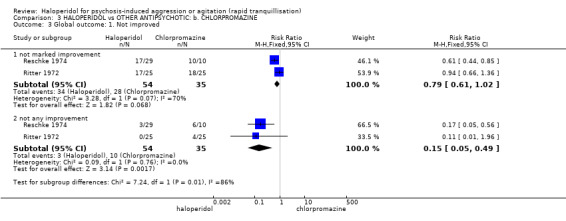

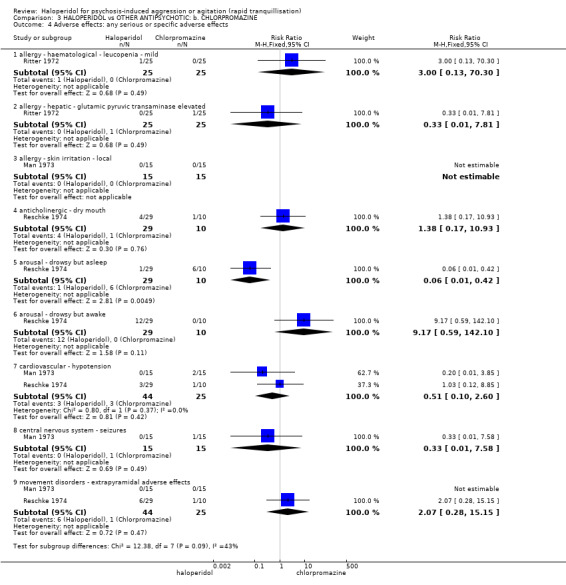

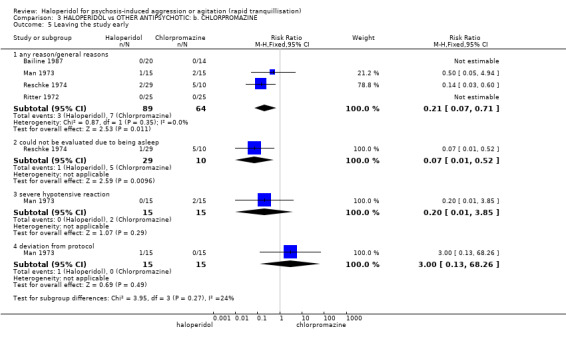

Summary of findings 3. HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: b. CHLORPROMAZINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared with OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: b. CHLORPROMAZINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: b. CHLORPROMAZINE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: b. CHLORPROMAZINE | HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep Not tranquil or asleep | Low1 | RR 1.93 (1.04 to 3.60) | 39 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 200 per 1000 | 386 per 1000 (208 to 720) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 500 per 1000 | 965 per 1000 (520 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 700 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (728 to 1000) | |||||

| Repeated need for rapid tranquillisation ‐ more that 1 injection | Low1 | RR 1.07 (0.89 to 1.28) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 800 per 1000 | 856 per 1000 (712 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 900 per 1000 | 963 per 1000 (801 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 990 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (881 to 1000) | |||||

| Specific behaviour ‐ threat or injury of harm to self or others ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Global outcome ‐ not any improvement | Low1 | RR 0.15 (0.05 to 0.49) | 89 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3 | ||

| 1000 per 1000 | 150 per 1000 (50 to 490) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 300 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (15 to 147) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 500 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (25 to 245) | |||||

| Adverse effects: specific ‐ cardiovascular ‐ hypotension | Low1 | RR 0.51 (0.01 to 2.60) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 50 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (0 to 192) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 150 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 (1 to 577) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 250 per 1000 | 50 per 1000 (2 to 962) | |||||

| Adverse effects: specific ‐ central nervous system ‐ seizures | Low1 | RR 0.33 (0.01 to 7.58) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (0 to 76) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (0 to 379) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 150 per 1000 | 50 per 1000 (1 to 1000) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control risk ‐ moderate risk roughly equates to that of the control group 2 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ not explicitly described as randomised, missing data was not imputed using appropriate methods such as LOCF, small study. 3 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ small study. 4 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ small study (15 participants per group).

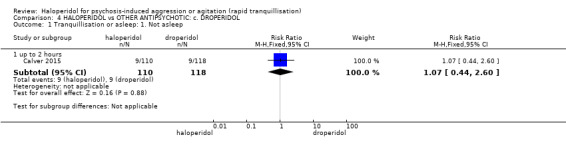

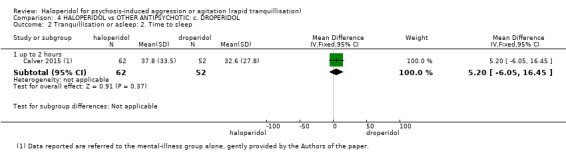

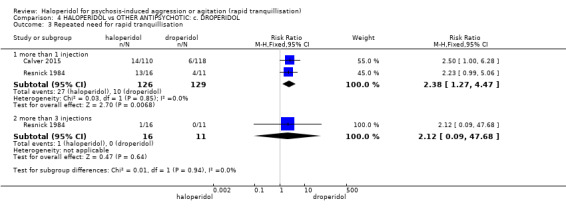

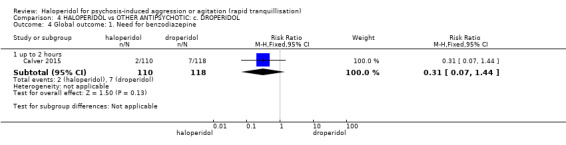

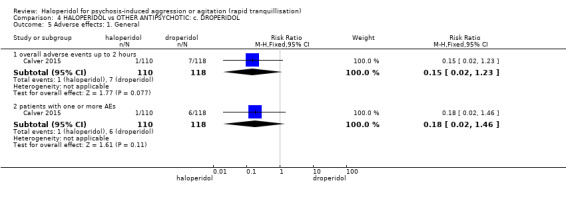

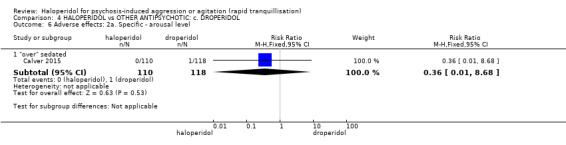

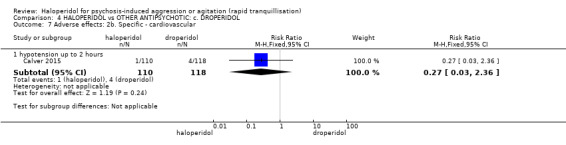

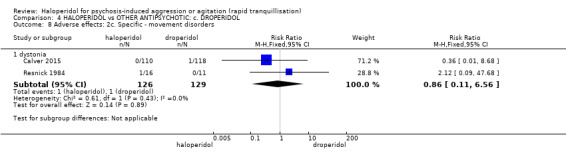

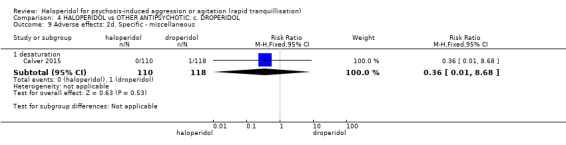

Summary of findings 4. HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: c. DROPERIDOL for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: c. DROPERIDOL for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients; emergency room. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: c. DROPERIDOL | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: c. DROPERIDOL | Risk with HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ not asleep up to 2 hours | Study population | RR 1.07 (0.44 to 2.60) | 228 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 82 per 1.000 | 88 per 1.000 (36 to 213) | |||||

| Repeated need for rapid tranquillisation ‐ more than 1 injection | Low | RR 2.38 (1.27 to 4.47) | 255 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ||

| 50 per 1.000 | 119 per 1.000 (64 to 224) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 70 per 1.000 | 167 per 1.000 (89 to 313) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 360 per 1.000 | 857 per 1.000 (457 to 1.000) | |||||

| Specific behaviour ‐ threat or injury to self or others ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome. |

| Global outcome ‐ need for benzodiazepine | Study population | RR 0.31 (0.07 to 1.44) | 228 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 59 per 1.000 | 18 per 1.000 (4 to 85) | |||||

| Adverse effects: specific ‐ dystonia | Study population | RR 0.86 (0.11 to 6.56) | 255 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 | ||

| 8 per 1.000 | 7 per 1.000 (1 to 51) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 CI include no effect

2 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ method of randomisation not reported, described as double blind but no further information given regarding rater blinding, small short study.

3 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ small study.

4 Moderate risk roughly equates with that of the trial control group,

5 Adverse effects ‐ imprecision ‐ 95% confidence interval.

6 Adverse effects ‐ publication bias ‐ small study.

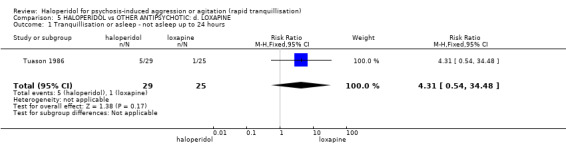

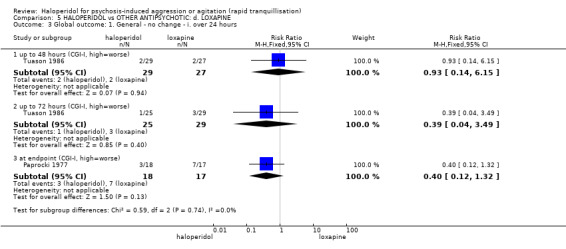

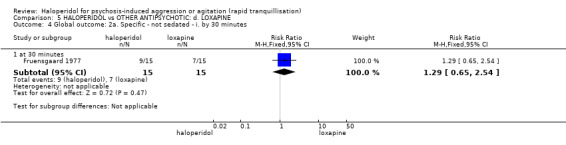

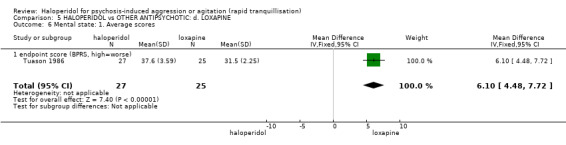

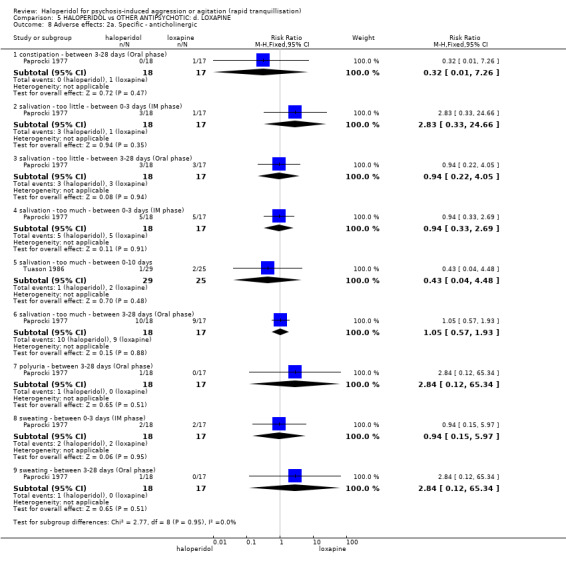

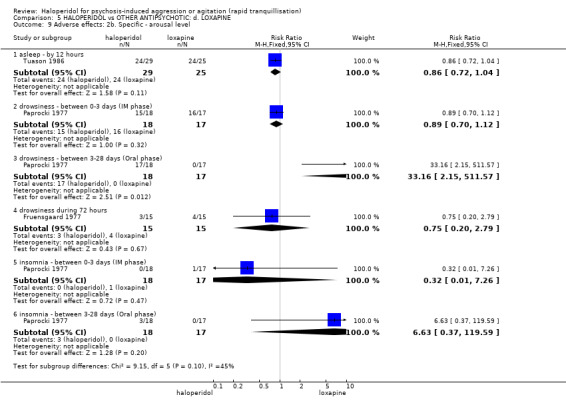

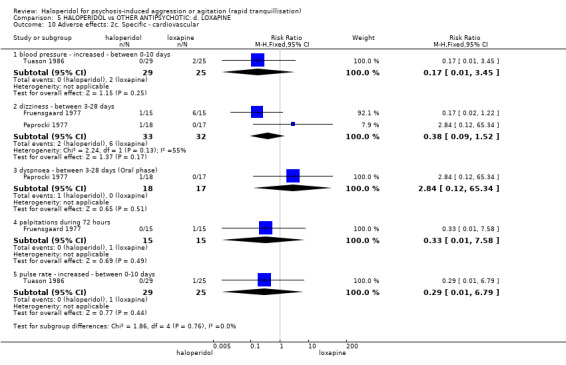

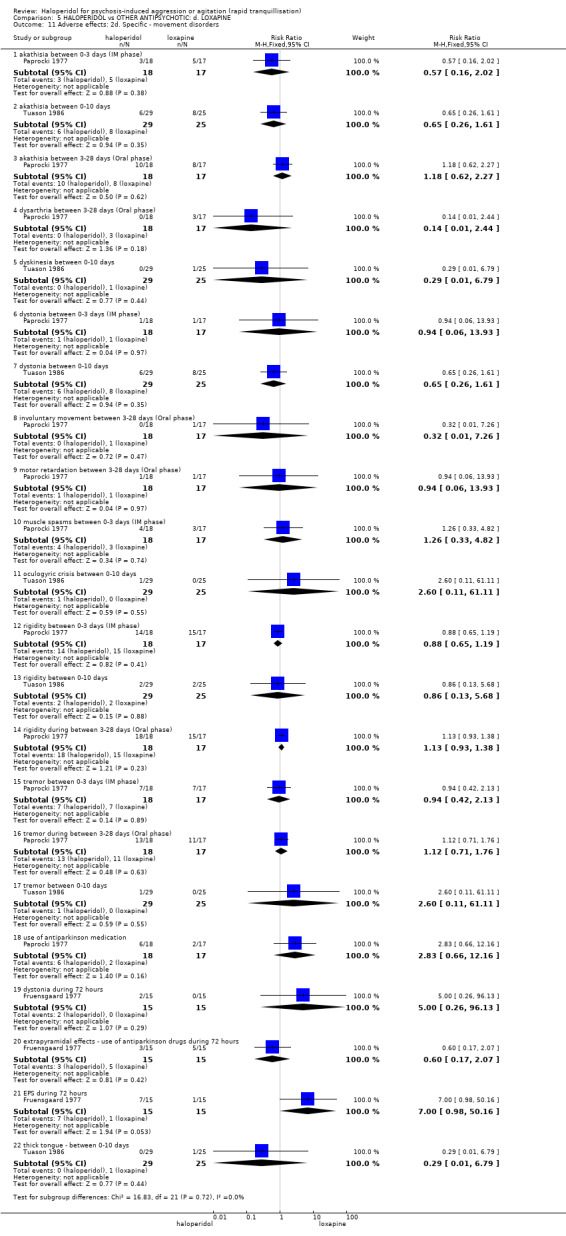

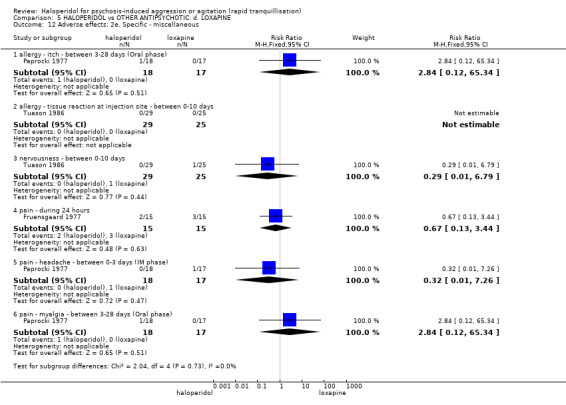

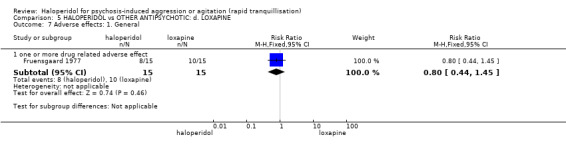

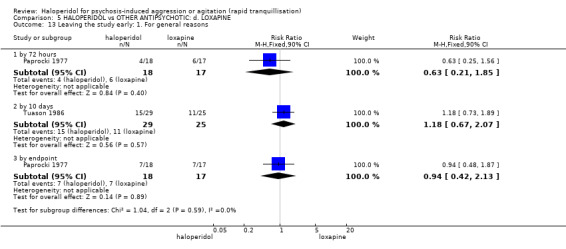

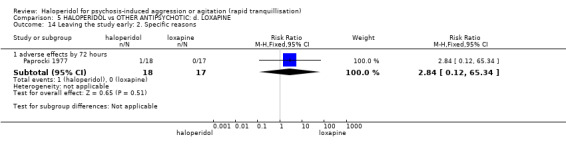

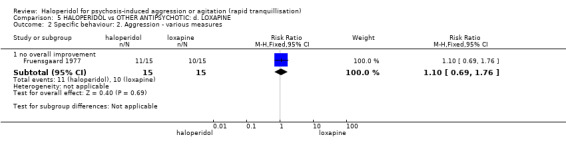

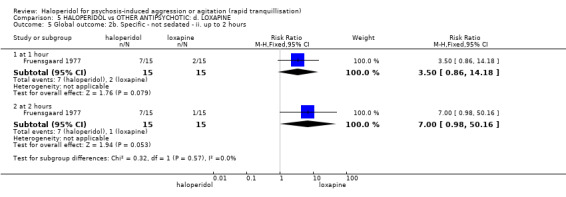

Summary of findings 5. HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: d. LOXAPINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared with OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS: d. LOXAPINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients to psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients; emergency room. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS: d. LOXAPINE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS: d. LOXAPINE | HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ not asleep by 12 hours | Low1 | RR 4.31 (0.54 to 34.48) | 54 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 43 per 1000 (5 to 345) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 215 per 1000 (27 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 431 per 1000 (54 to 1000) | |||||

| Global outcome: specific Not sedated at 60 minutes * | Low1 | RR 3.50 (0.86 to 14.18) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,5,6 | * data for prespecified outcome Repeated need for rapid tranquillisation were not reported | |

| 10 per 1000 | 57 per 1000 (9 to 345) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 569 per 1000 (94 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (188 to 1000) | |||||

| Specific behaviour ‐ aggression ‐ no overall improvement | Low1 | RR 1.10 (0.69 to 1.76) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,6,7 | ||

| 500 per 1000 | 550 per 1000 (345 to 880) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 650 per 1000 | 715 per 1000 (448 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 800 per 1000 | 880 per 1000 (552 to 1000) | |||||

| Global outcome: no change at 48 hours CGI | Low1 | RR 0.93 (0.14 to 6.15) | 56 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,4 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (1 to 62) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 70 per 1000 | 65 per 1000 (10 to 431) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 140 per 1000 | 130 per 1000 (20 to 861) | |||||

| Adverse effects: Specific ‐ dystonia between 0‐3 days (IM phase) | Low1 | RR 0.94 (0.06 to 13.93) | 35 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (1 to 139) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 47 per 1000 (3 to 697) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 94 per 1000 (6 to 1000) | |||||

| Adverse effects: Specific ‐ rigidity between 0‐3 days (IM phase) | Low1 | RR 0.88 (0.65 to 1.19) | 35 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,6 | ||

| 750 per 1000 | 660 per 1000 (487 to 893) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 850 per 1000 | 748 per 1000 (552 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 950 per 1000 | 836 per 1000 (617 to 1000) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Moderate risk is roughly equal to that of the control group. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ method of randomisation not described, allocation concealment not stated, staff administering medication were not blind to the intervention, the number of participants reported as leaving the study at certain time points is inconsistent. 3 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ reported at 12 hours rather than 30 minutes as stated in protocol. 4 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ 95% confidence interval is wide. 5 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ no data on repeated need for rapid tranquillisation, therefore inferred from the data 'not sedated at 60 minutes'. 6 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ small study. 7 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ not able to use threat or injury to self or others as stated in the protocol because this was not reported.

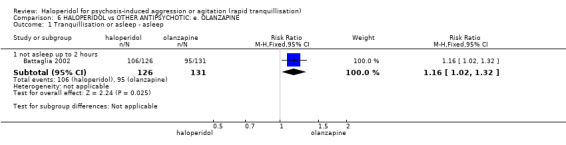

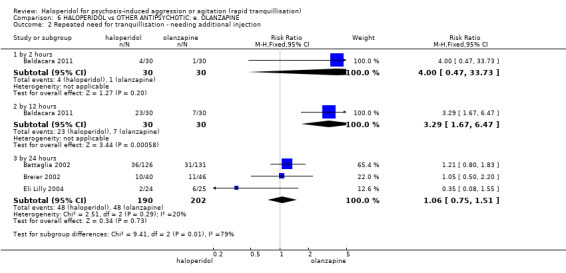

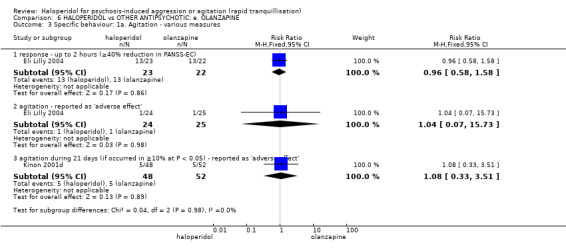

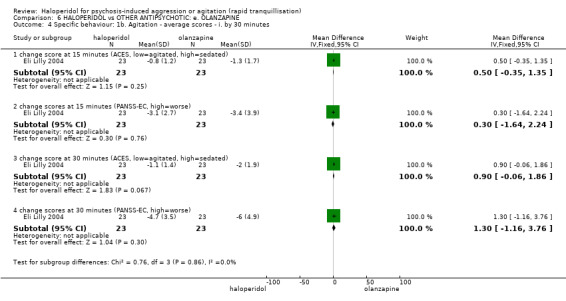

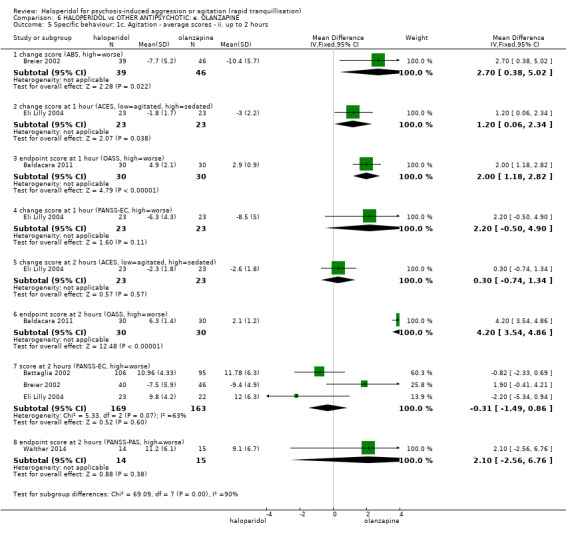

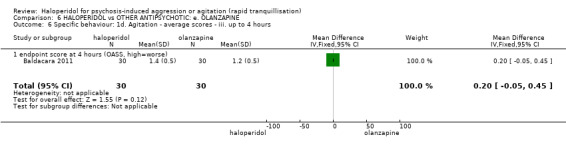

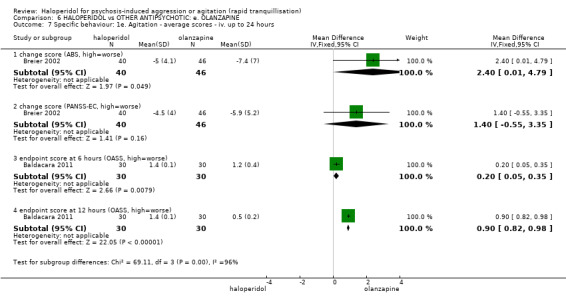

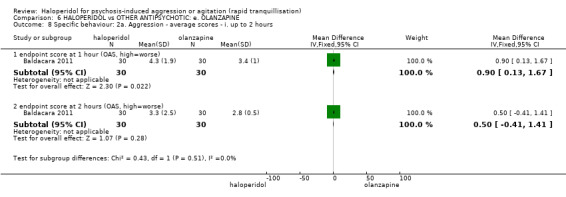

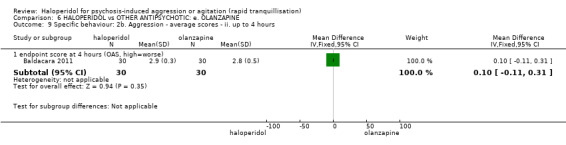

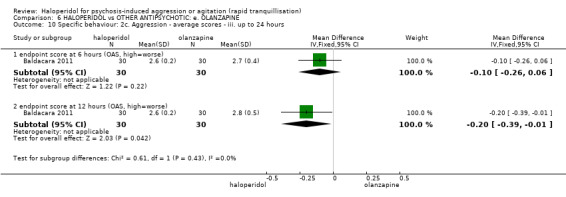

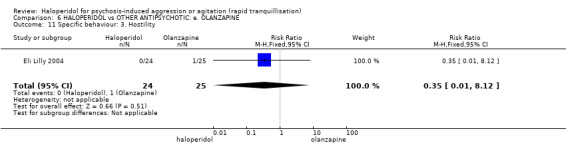

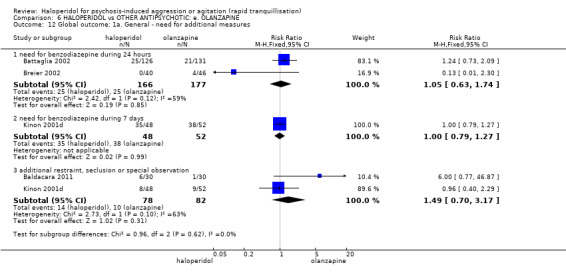

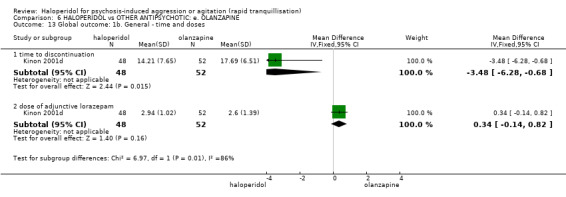

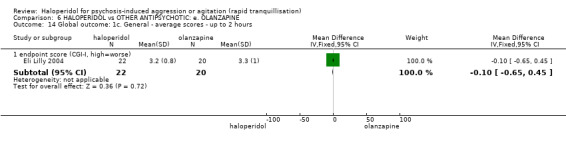

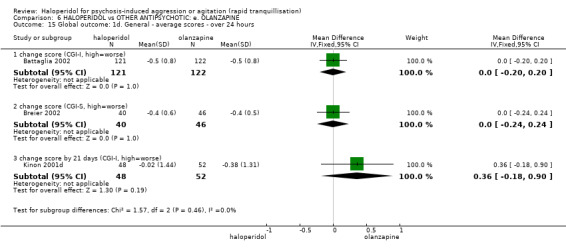

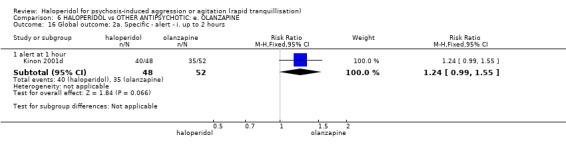

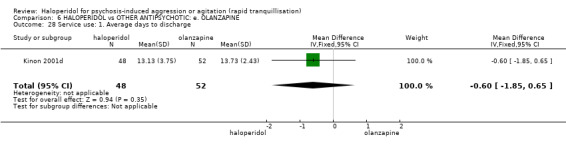

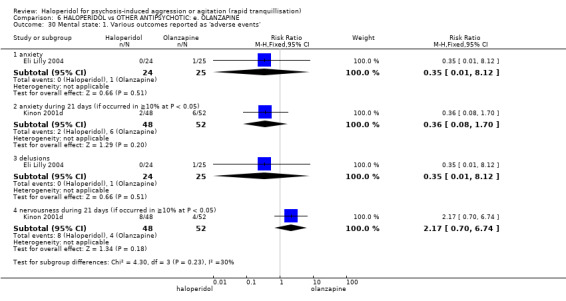

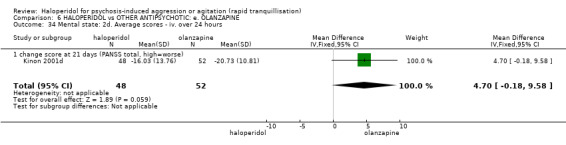

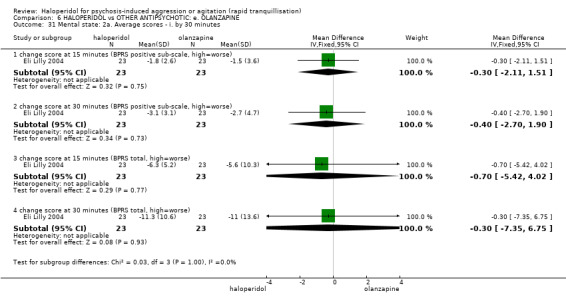

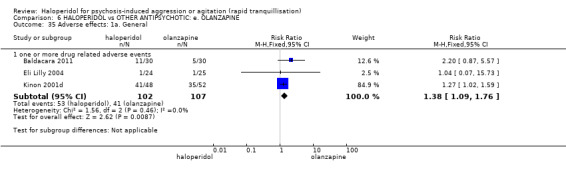

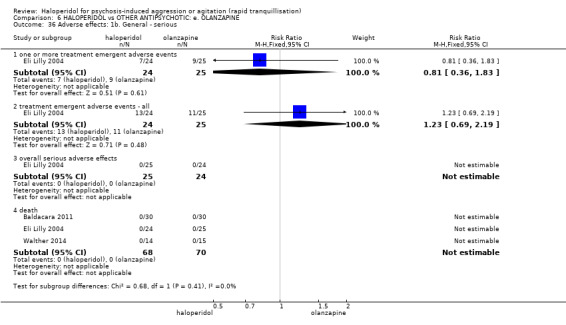

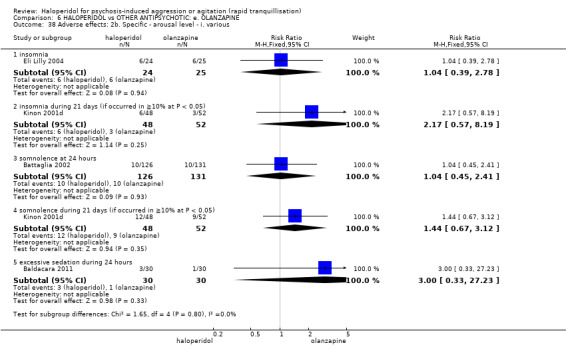

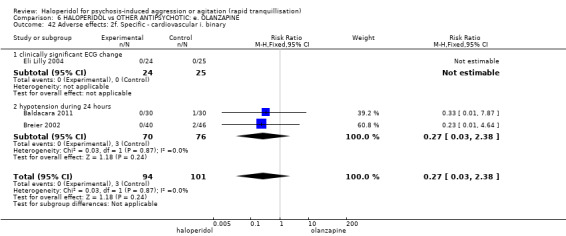

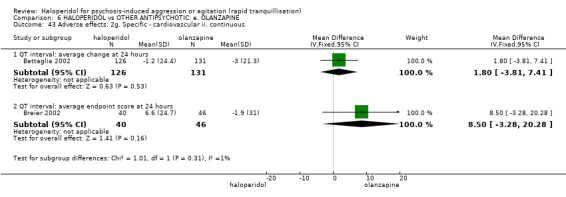

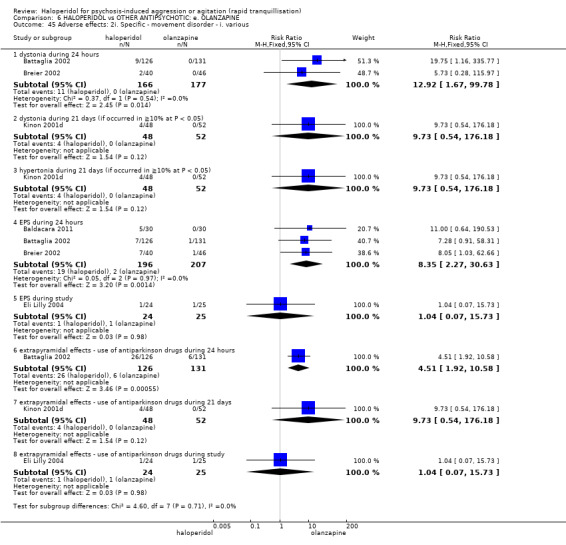

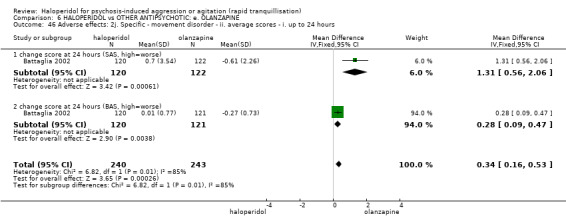

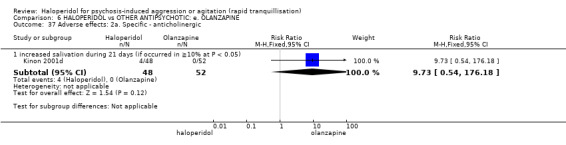

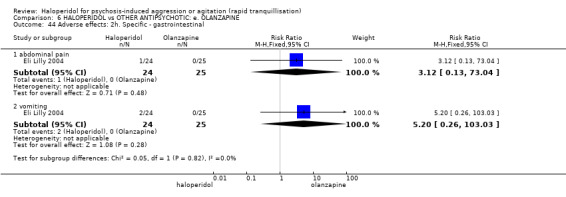

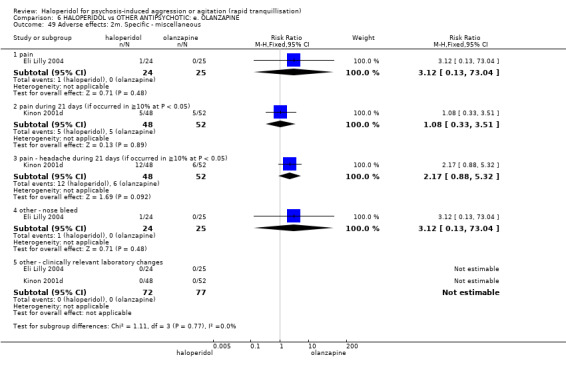

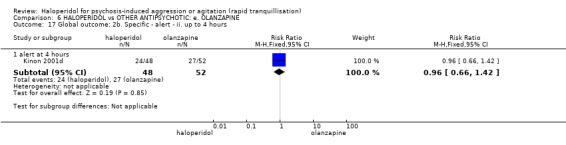

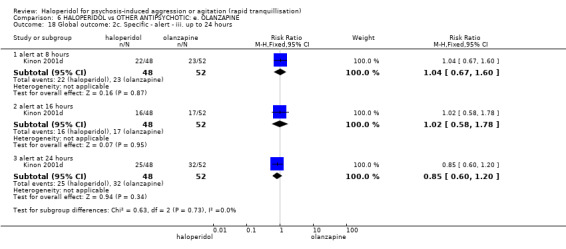

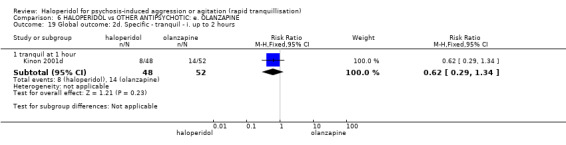

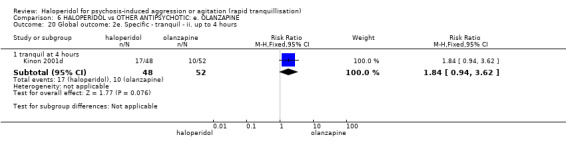

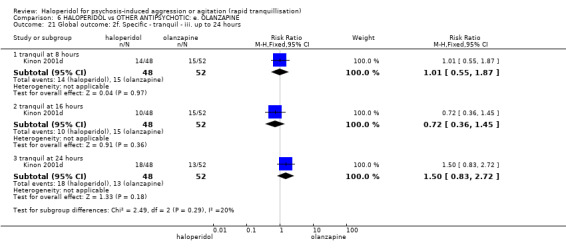

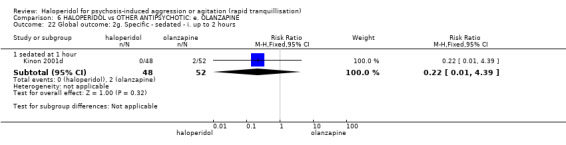

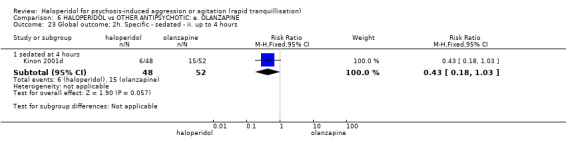

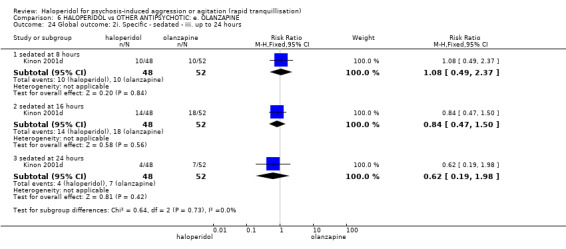

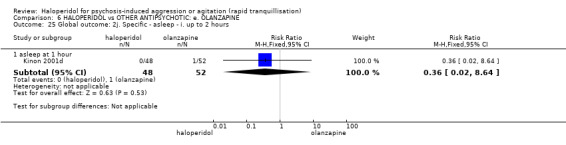

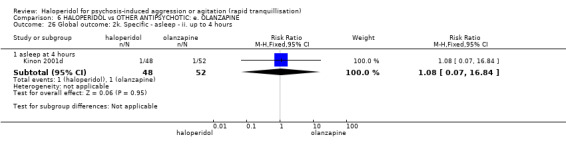

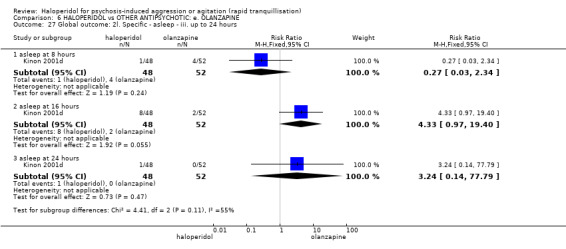

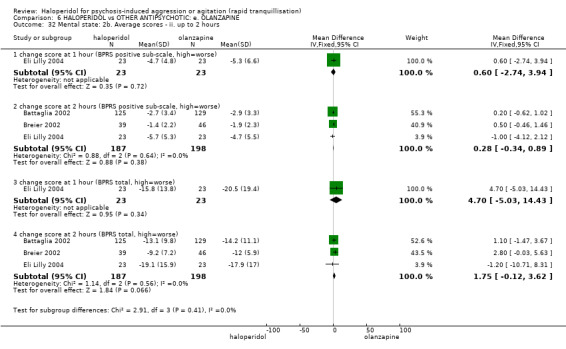

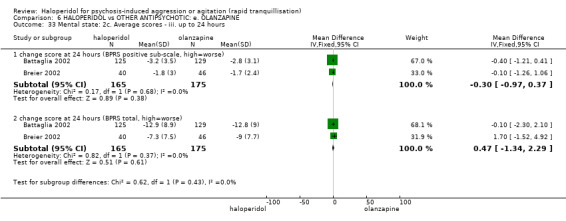

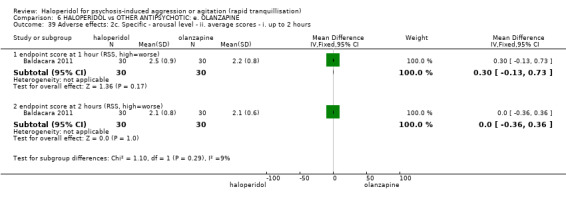

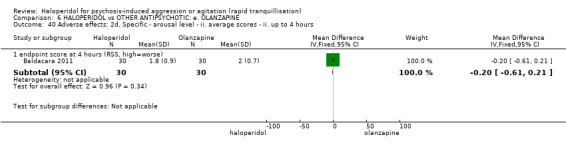

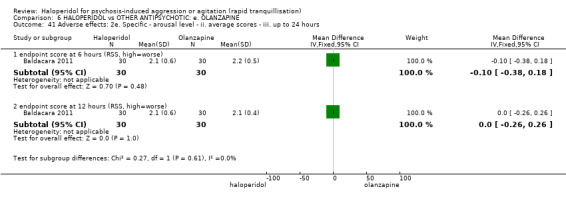

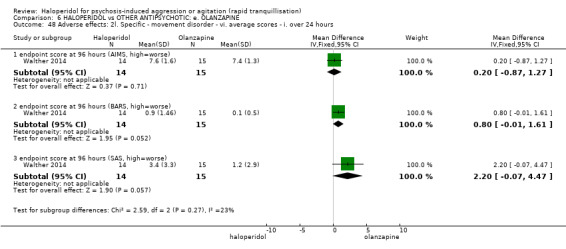

Summary of findings 6. HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: e. OLANZAPINE for psychosis induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: e. OLANZAPINE for psychosis induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: psychosis induced aggression or agitation Setting: Emergency room; multi‐centre. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: e. OLANZAPINE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: e. OLANZAPINE | Risk with HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquilisation or asleep assessed with: not asleep up to 2 hours | Low | RR 1.16 (1.02 to 1.32) | 257 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 3 | ||

| 200 per 1.000 | 232 per 1.000 (204 to 264) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 700 per 1.000 | 812 per 1.000 (714 to 924) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 900 per 1.000 | 1000 per 1.000 (918 to 1.000) | |||||

| Repeated need for tranquillisation assessed with: needing an additional injection by 24 hours | Low | RR 1.06 (0.75 to 1.51) | 392 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 | ||

| 50 per 1.000 | 53 per 1.000 (38 to 76) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 200 per 1.000 | 212 per 1.000 (150 to 302) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 350 per 1.000 | 371 per 1.000 (262 to 529) | |||||

| Specific behaviour ‐ threat or injury to self or others assessed with: less than 40% reduction in PANSS‐EC rated at 2 hours | Low | RR 0.96 (0.58 to 1.58) | 45 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 5 | ||

| 200 per 1.000 | 192 per 1.000 (116 to 316) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 400 per 1.000 | 384 per 1.000 (232 to 632) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 600 per 1.000 | 576 per 1.000 (348 to 948) | |||||

| Global outcome ‐ need for benzodiazepine during 24 hours | Low | RR 1.05 (0.63 to 1.74) | 343 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 6 7 | ||

| 50 per 1.000 | 53 per 1.000 (32 to 87) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 150 per 1.000 | 158 per 1.000 (95 to 261) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 250 per 1.000 | 263 per 1.000 (158 to 435) | |||||

| Adverse effects: Specific ‐ dystonia during 24 hours | Low | RR 12.92 (1.67 to 99.78) | 343 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 6 7 | ||

| 0 per 1.000 | 0 per 1.000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1.000 | 0 per 1.000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 5 per 1.000 | 65 per 1.000 (8 to 499) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies reported this outcome. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Moderate risk is roughly equal to that of the control group.

2 Risk of bias: rated 'very serious' ‐ method of randomisation not reported, allocation concealment not stated, described as double blind but no further details are given regarding blinding, selective reporting, sponsored by drug company.

3 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ tranquil at 30 minutes is not measured, therefore used not asleep at 2 hour.

4 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ sponsored by drug company.

5 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ not threat or injury to self or others as stated in protocol, therefore inferred further aggressive behaviour by less than a 40% reduction in PANSS‐EC score.

6 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ method of randomisation is not reported, allocation concealment not stated, described as double blind but no further information given, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, sponsored by drug company.

7 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ 95% confidence interval is wide.

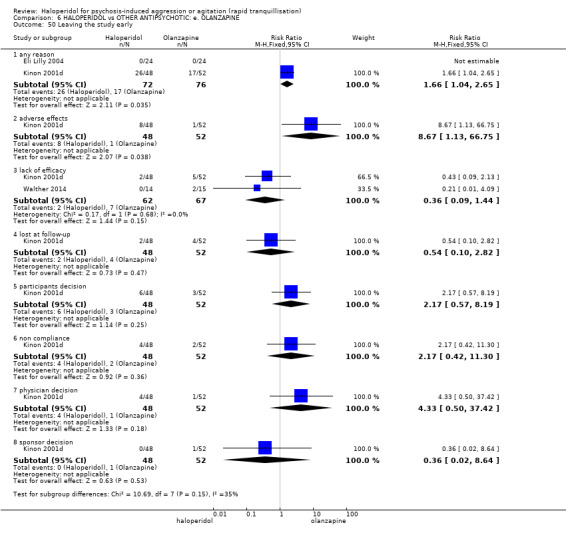

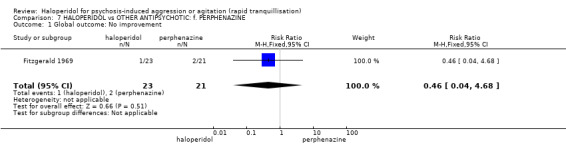

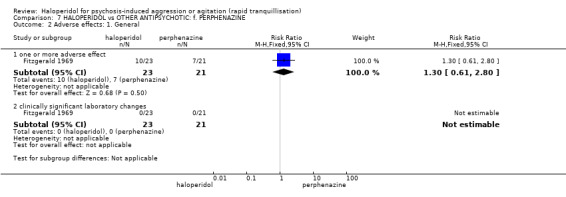

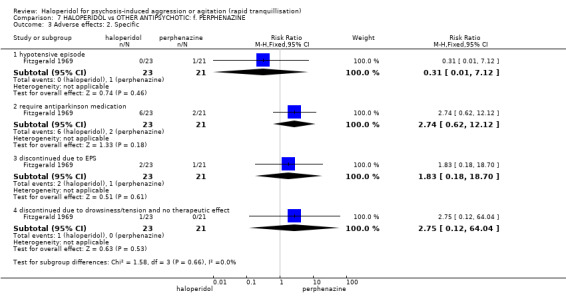

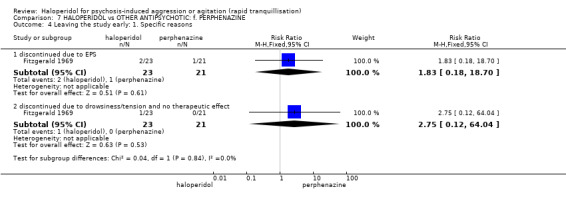

Summary of findings 7. HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: f. PERPHENAZINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared with OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: f. PERPHENAZINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: f. PERPHENAZINE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: f. PERPHENAZINE | HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Repeated need for rapid tranquillisation ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Specific behaviour ‐ injury or threat of self to others ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Global outcome: general ‐ no improvement | Low1 | RR 0.46 (0.04 to 4.68) | 44 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (0 to 47) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (4 to 468) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 92 per 1000 (8 to 936) | |||||

| Adverse effect: Specific ‐ hypotensive episode | Low1 | RR 0.31 (0.01 to 7.12) | 44 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (0 to 71) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (0 to 356) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 31 per 1000 (1 to 712) | |||||

| Adverse effect ‐ discontinued due to EPS | Low1 | RR 1.83 (0.18 to 18.7) | 44 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,5 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (2 to 187) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 92 per 1000 (9 to 935) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 183 per 1000 (18 to 1000) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Moderate risk is roughly equal to that of the trial control group. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ method or randomisation not described, allocation concealment not stated, described as double‐blind but no further details given regarding rater blinding, author suspects that only the adverse effects severe enough to warrant discontinuation were reported. 3 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ small study. 4 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ 95% confidence interval is wide, small study. 5 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ not specific adverse effect ‐ only have data for the number of people discontinued due to EPS, not the number of people who had EPS in general.

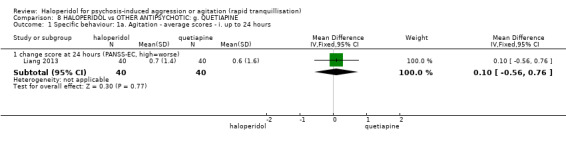

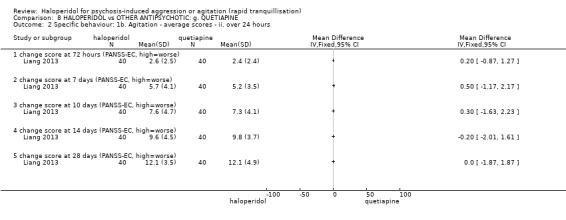

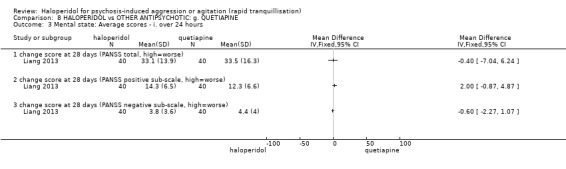

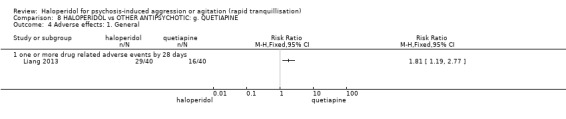

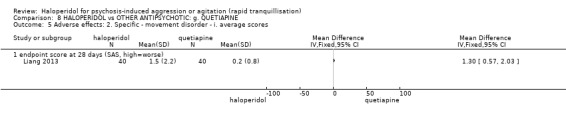

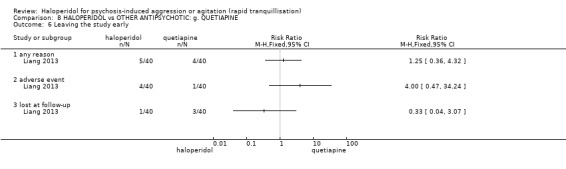

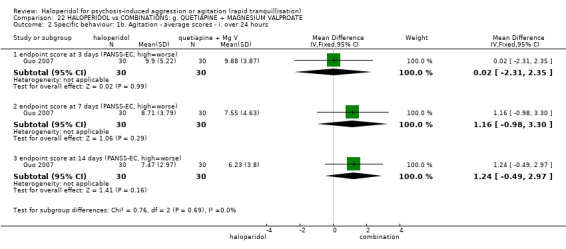

Summary of findings 8. HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS: g. QUETIAPINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS: g. QUETIAPINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS: g. QUETIAPINE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS: g. QUETIAPINE | Risk with HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome. |

| Repeated need for tranquillisation ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome. |

| Specific behaviour ‐ agitation assessed with: change score at 24 hours on the PANSS‐EC | MD 0.10 higher (0.56 lower to 0.76 higher) | ‐ | 80 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ||

| Global outcome ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome. |

| Adverse effects assessed with: one or more drug‐related adverse events | Low | RR 1.81 (1.19 to 2.77) | 80 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ||

| 200 per 1.000 | 362 per 1.000 (238 to 554) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 400 per 1.000 | 724 per 1.000 (476 to 1.000) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 600 per 1.000 | 1000 per 1.000 (714 to 1.000) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Imprecision: rated 'very serious' ‐ small study, 95% CI are wide.

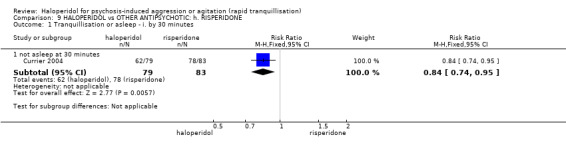

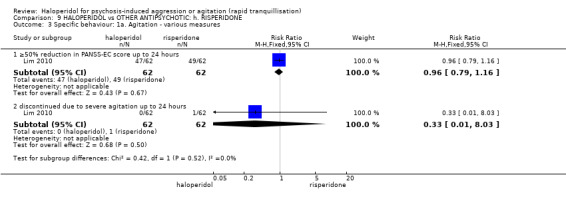

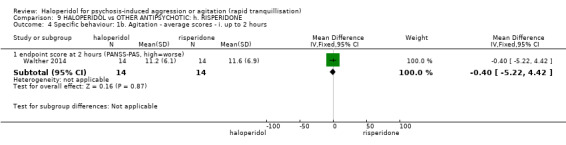

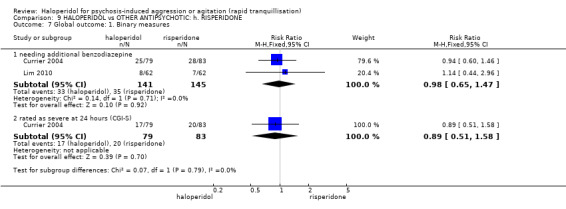

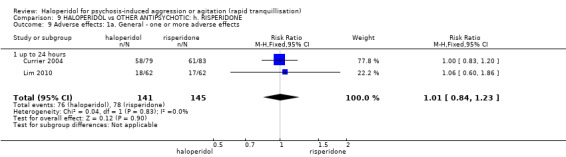

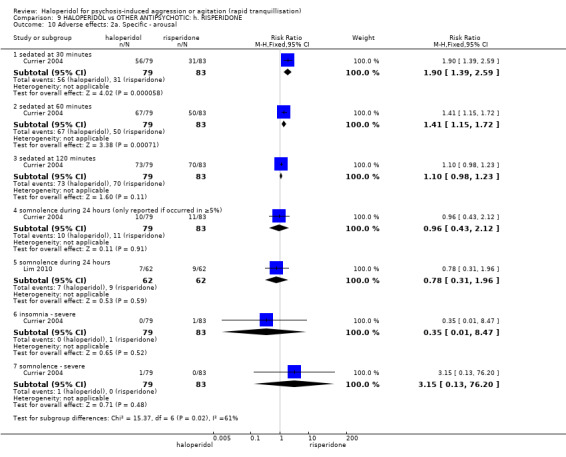

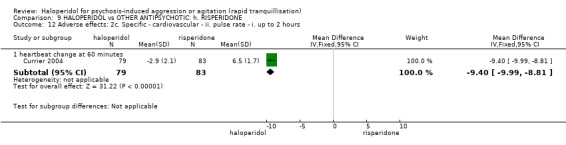

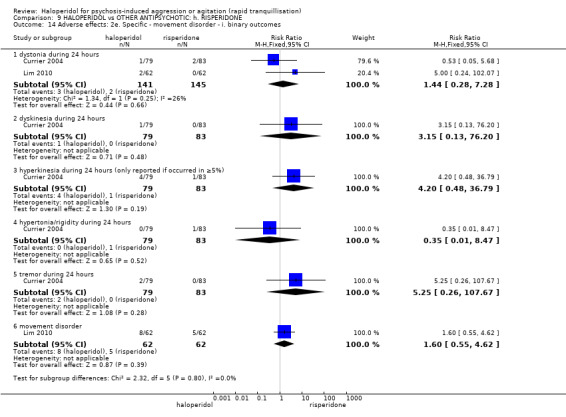

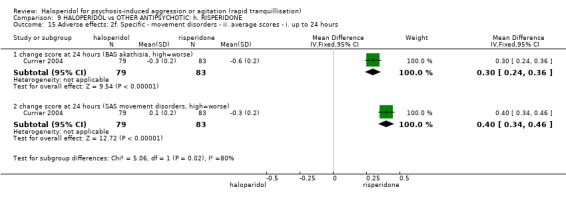

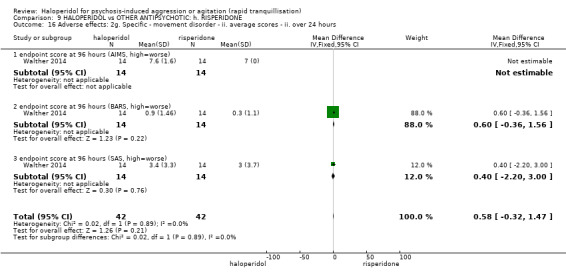

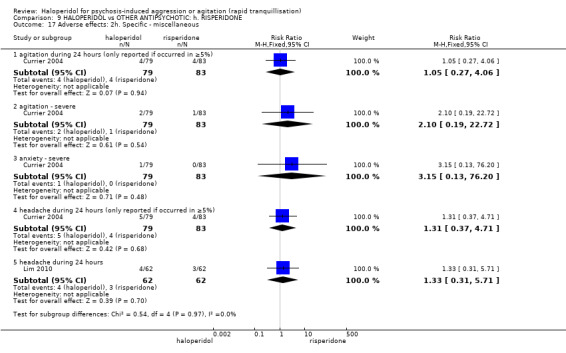

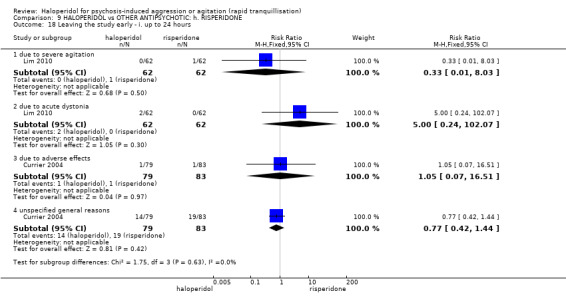

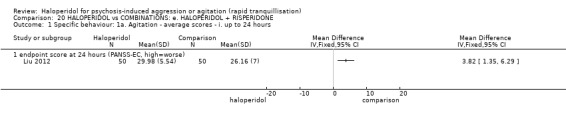

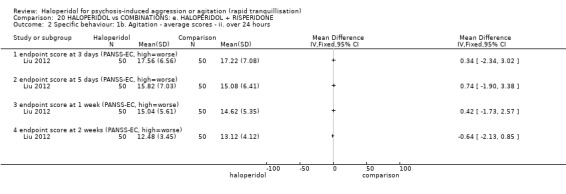

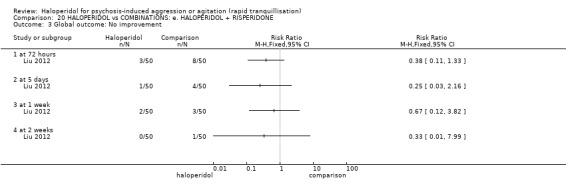

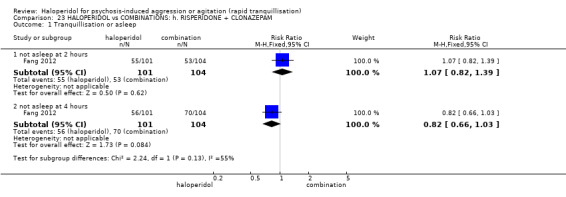

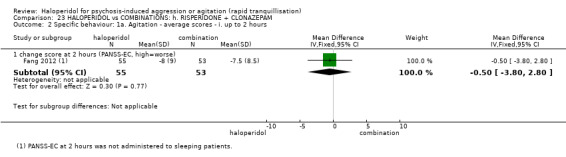

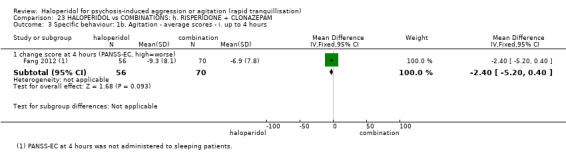

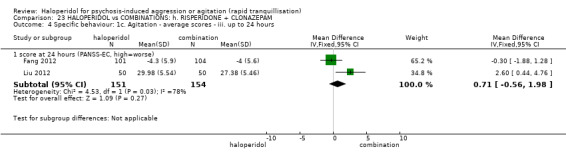

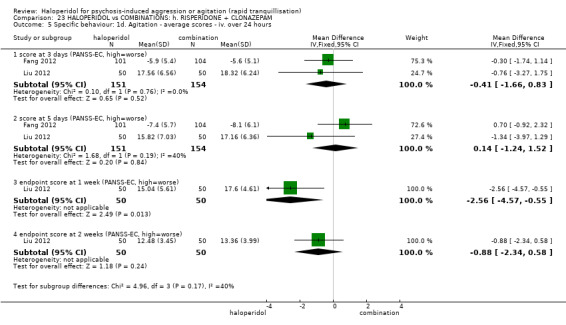

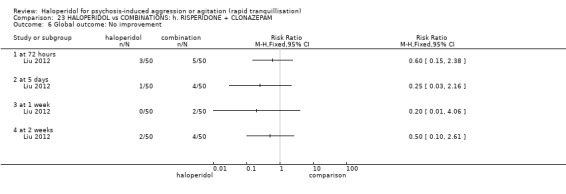

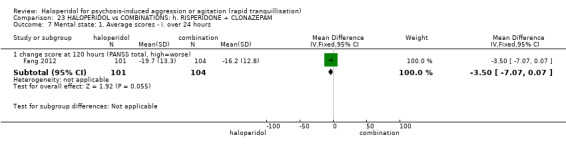

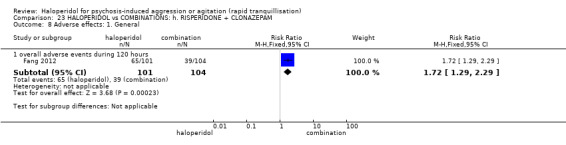

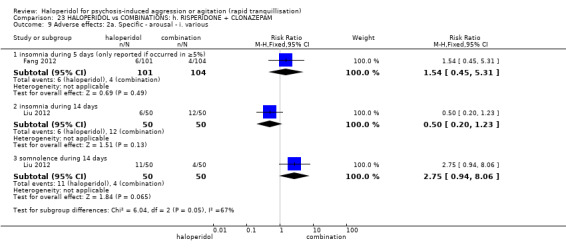

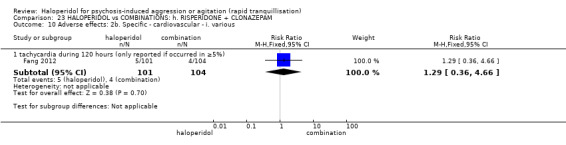

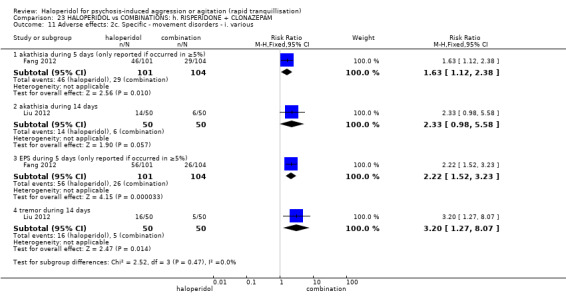

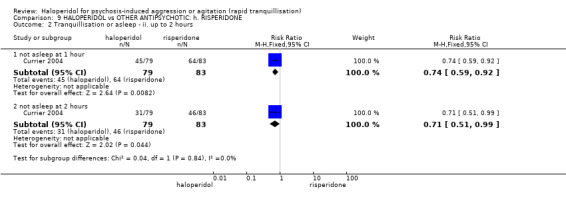

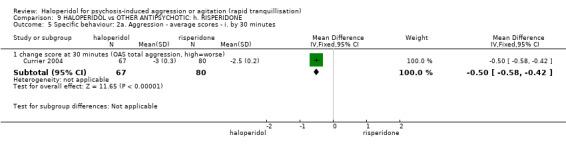

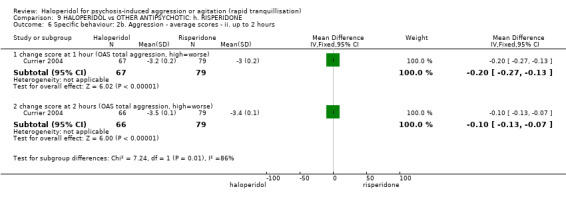

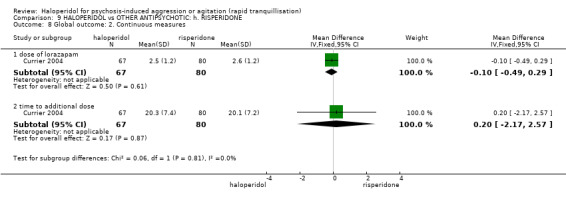

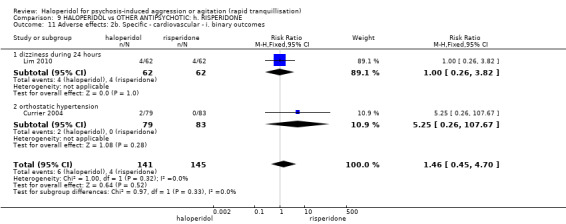

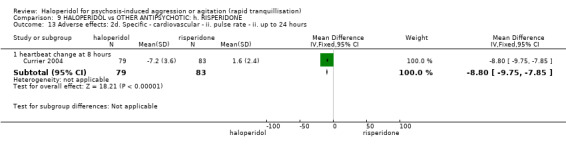

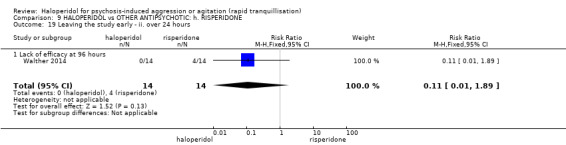

Summary of findings 9. HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: h. RISPERIDONE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared with OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: g. RISPERIDONE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients; emergency room; multi‐centre. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: g. RISPERIDONE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: g. RISPERIDONE | HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ not asleep | Low1 | RR 0.84 (0.74 to 0.95) | 162 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ||

| 700 per 1000 | 588 per 1000 (518 to 665) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 900 per 1000 | 756 per 1000 (666 to 855) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 1000 per 1000 | 840 per 1000 (740 to 950) | |||||

| Repeated need for rapid tranquillisation ‐ needing additional benzodiazepine | Low | RR 0.98 (0.65 to 1.47) | 286 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| 100 per 1000 | 98 per 1000 (65 to 147) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 196 per 1000 (130 to 294) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 300 per 1000 | 294 per 1000 (195 to 441) | |||||

| Specific behaviours ‐ agitation >50% reduction in PANSS‐EC score Follow‐up: 1 days | Low1 | RR 1.15 (0.6 to 2.22) | 124 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,4 | ||

| 50 per 1000 | 58 per 1000 (30 to 111) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 230 per 1000 (120 to 444) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 350 per 1000 | 402 per 1000 (210 to 777) | |||||

|

Global outcome ‐ rated as severe ‐ CGI‐S Follow‐up: 1 days |

Low1 | RR 0.89 (0.51 to 1.58) | 162 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 100 per 1000 | 89 per 1000 (51 to 158) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 178 per 1000 (102 to 316) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 300 per 1000 | 267 per 1000 (153 to 474) | |||||

| Adverse effects: Specific ‐ EPS during 24 hours | Low1 | RR 1.6 (0.55 to 4.62) | 124 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,4 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (6 to 46) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 160 per 1000 (55 to 462) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 320 per 1000 (110 to 924) | |||||

| Adverse effects: Specific ‐ acute dystonia during 24 hours | Low1 | RR 5 (0.24 to 102.07) | 286 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 50 per 1000 (2 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 20 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (5 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 30 per 1000 | 150 per 1000 (7 to 1000) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Moderate risk is roughly equal to that of the trial control group. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ method of randomisation not described, single blind, sponsored by drug company. 3 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ few data and confidence intervals wide. 4 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected ‐ sponsored by drug company.

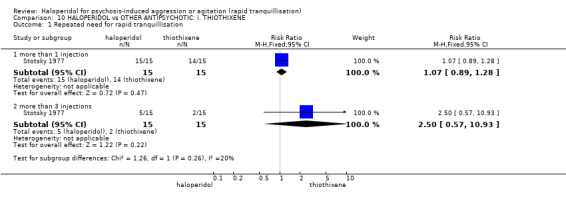

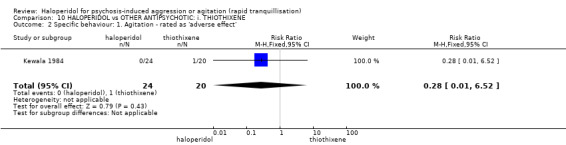

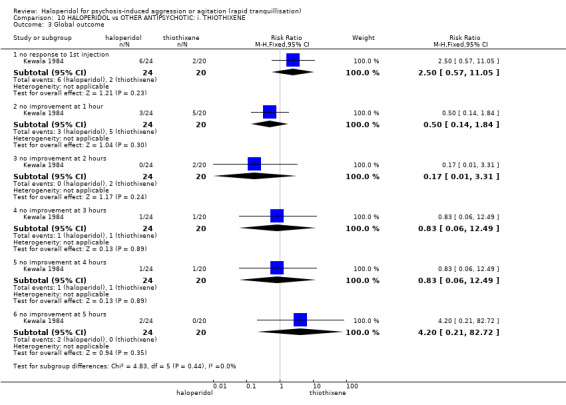

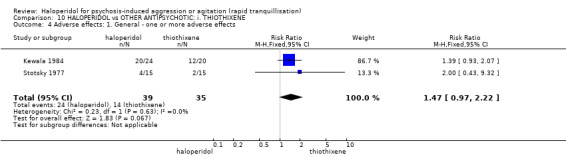

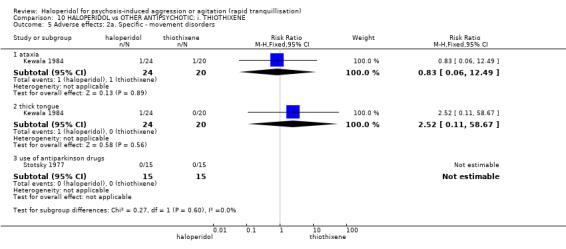

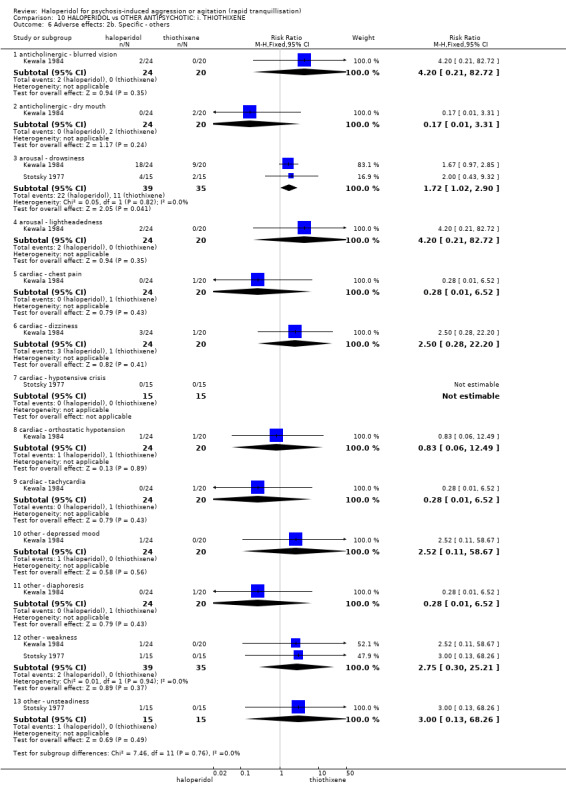

Summary of findings 10. HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: i. THIOTHIXENE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: h. THIOTHIXENE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients; emergency room. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: h. THIOTHIXENE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: h. THIOTHIXENE | HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Repeated need for rapid tranquillisation | Low1 | RR 1.07 (0.89 to 1.28) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3 | ||

| 850 per 1000 | 910 per 1000 (756 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 900 per 1000 | 963 per 1000 (801 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 950 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (845 to 1000) | |||||

| Specific behaviour ‐ threat or injury to self or others ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Global outcome No improvement at 1 hour | Low1 | RR 0.50 (0.14 to 1.84) | 44 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 50 per 1000 | 25 per 1000 (7 to 92) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 250 per 1000 | 125 per 1000 (35 to 460) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 450 per 1000 | 225 per 1000 (63 to 828) | |||||

| Adverse effects: specific ‐ hypotensive episode | Low | Not estimable | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Adverse effects: specific ‐ tachycardia | Low1 | RR 0.28 (0.01 to 6.52) | 44 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (0 to 65) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (0 to 326) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 28 per 1000 (1 to 652) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control risk ‐ moderate risk roughly equates to that of the trial control group. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ method of sequence generation not clear, allocation concealment not reported, small study, sponsored by drug company. 3 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ small study, sponsored by drug company. 4 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ small study, wide confidence intervals.

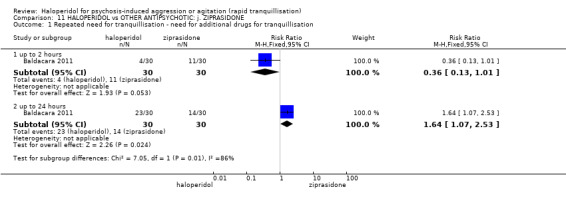

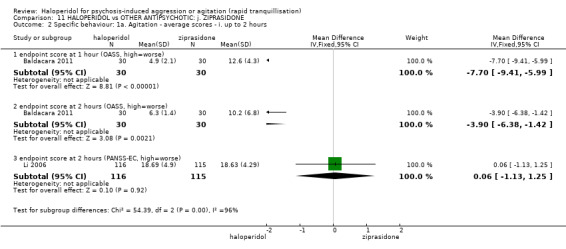

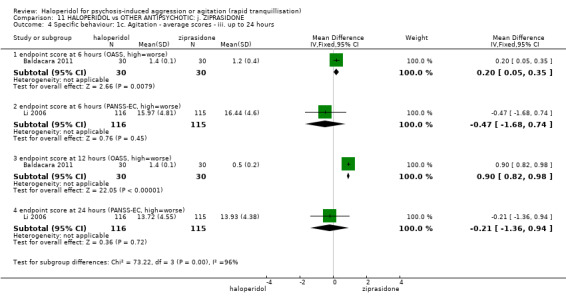

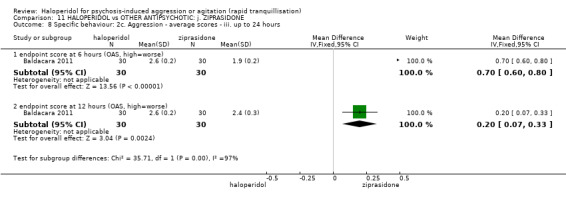

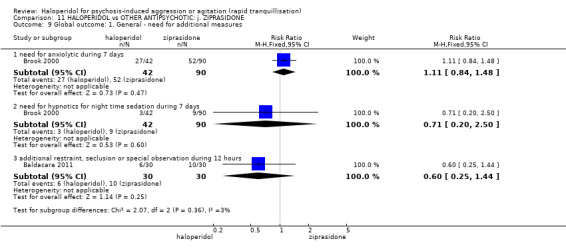

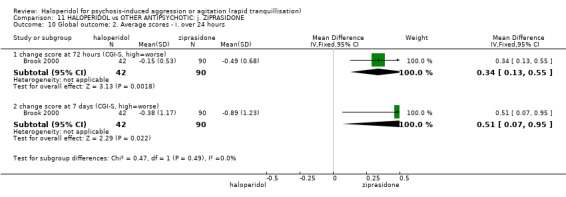

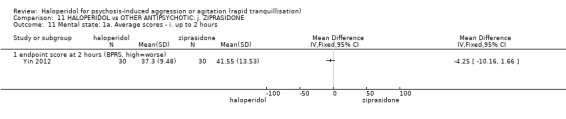

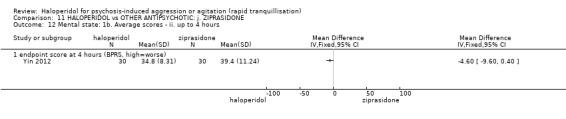

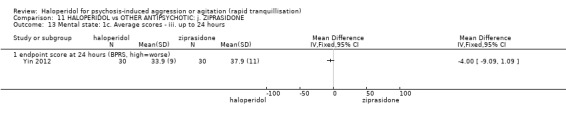

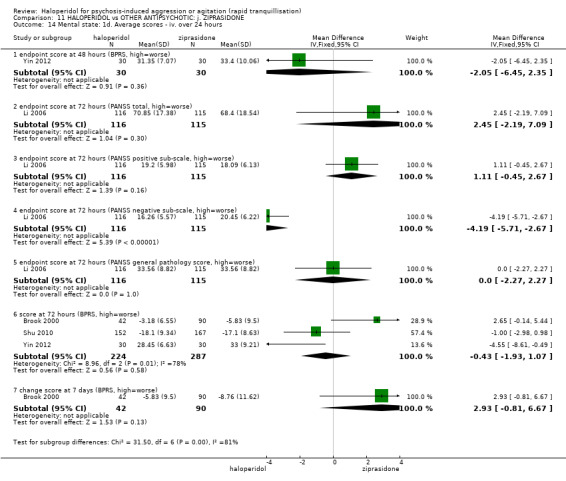

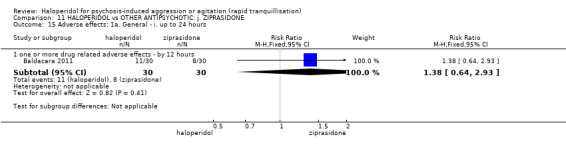

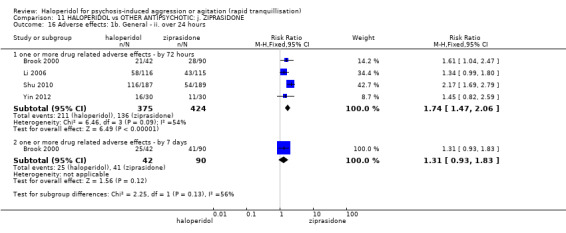

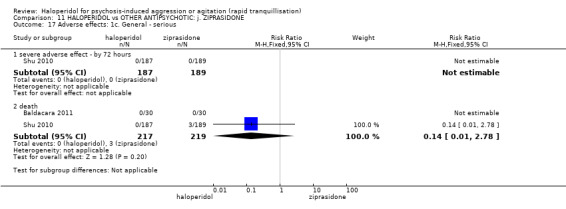

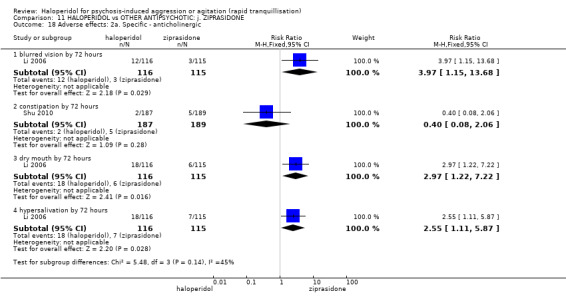

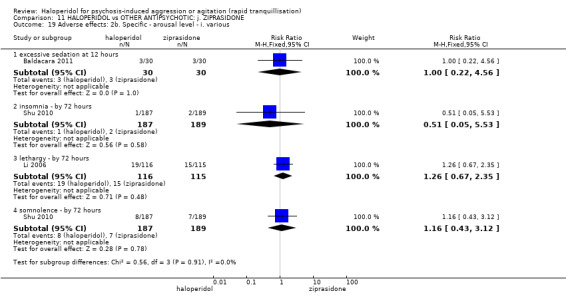

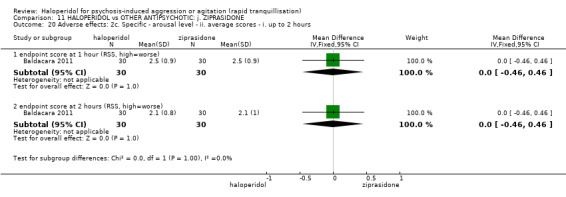

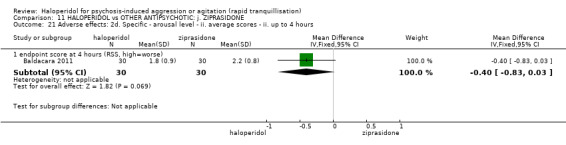

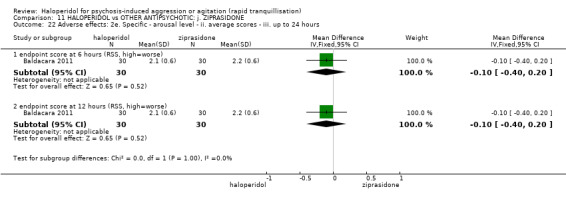

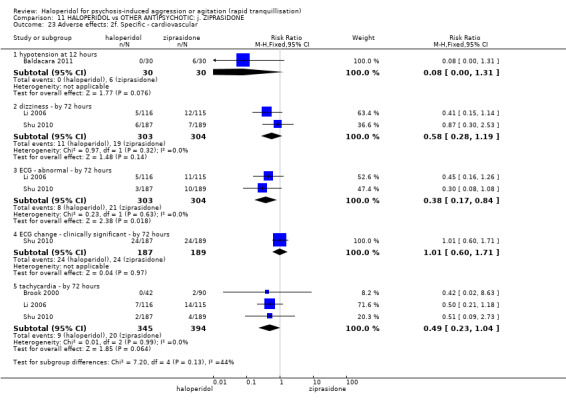

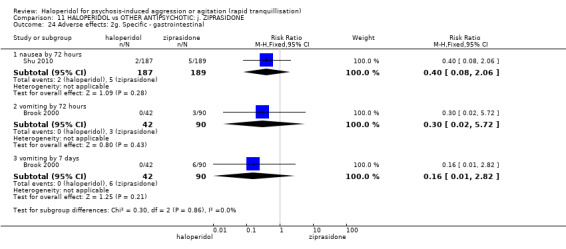

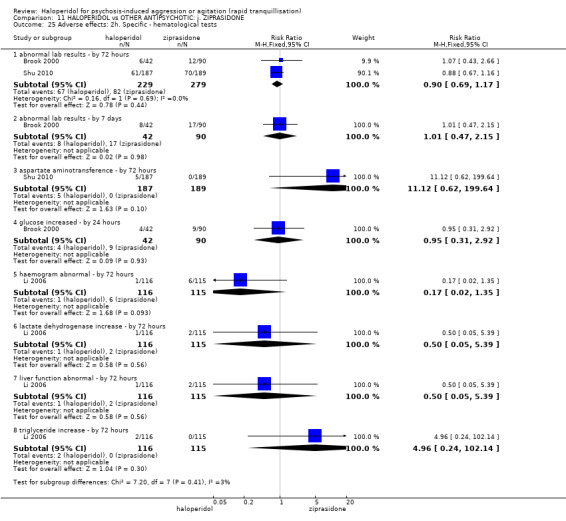

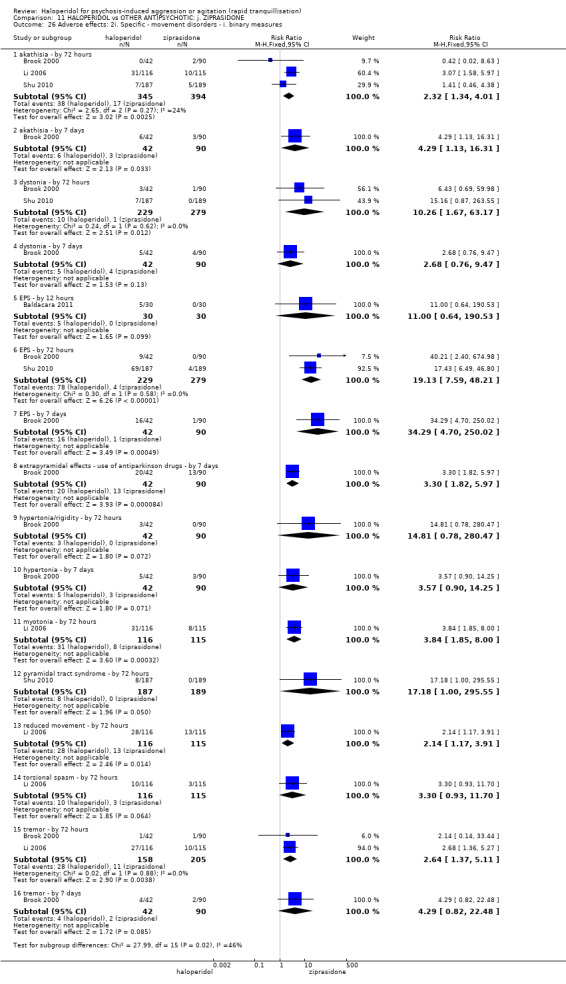

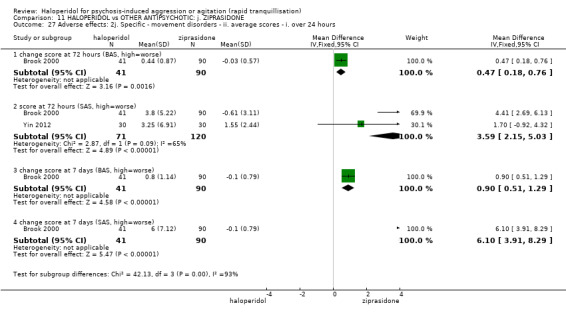

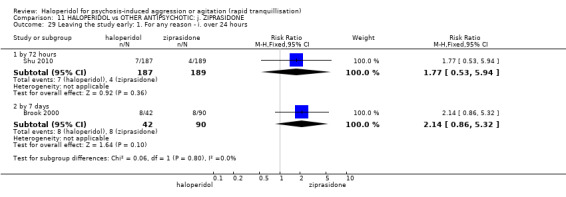

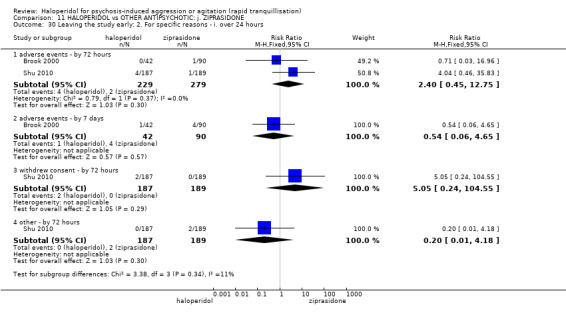

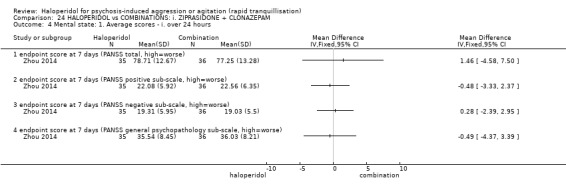

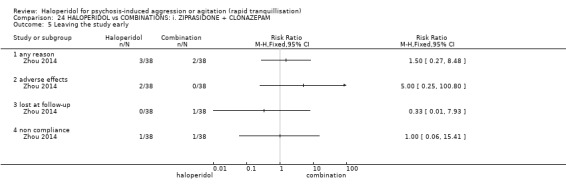

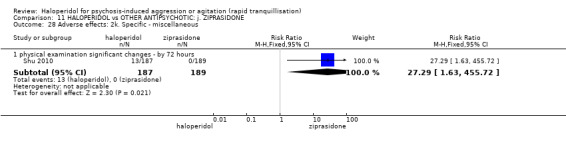

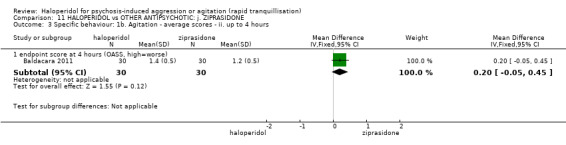

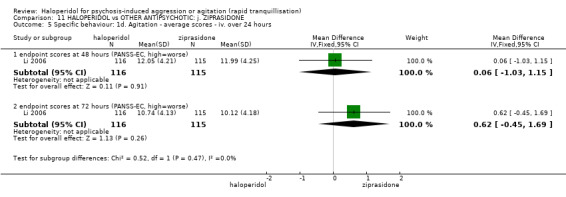

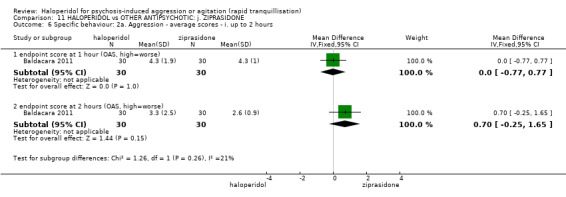

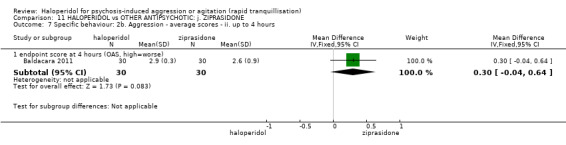

Summary of findings 11. HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: j. ZIPRASIDONE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: i. ZIPRASIDONE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients; emergency room; multi‐centre. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: i. ZIPRASIDONE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: i. ZIPRASIDONE | Risk with HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquilisation or asleep ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No trial reported this outcome. |

| Repeated need for tranquilisation assessed with: need for additional drugs for tranquillisation up to 24 hours | Study population | RR 1.64 (1.07 to 2.53) | 60 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 2 | ||

| 467 per 1.000 | 765 per 1.000 (499 to 1.000) | |||||

| Specific behaviour ‐ agitation assessed with: average endpoint scores at 2 hours on the PANSS‐EC follow up: 72 hours | MD 0.06 higher (1.13 lower to 1.25 higher) | ‐ | 231 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 4 | ||

| Global outcome assessed with: CGI‐S ‐ average change score at 72 hours. | MD 0.34 higher (0.13 higher to 0.55 higher) | ‐ | 132 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5 | ||

| Adverse effects: Specific ‐ dystonia during 72 hours | Low | RR 10.26 (1.67 to 63.17) | 508 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5 7 | ||

| 2 per 1.000 | 21 per 1.000 (3 to 126) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 4 per 1.000 | 41 per 1.000 (7 to 253) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 10 per 1.000 | 103 per 1.000 (17 to 632) | |||||

| Adverse effects: Specific ‐ clinically significant abnormal ECG during 72 hours | Study population | RR 1.01 (0.60 to 1.71) | 376 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3 9 | ||

| 127 per 1.000 | 128 per 1.000 (76 to 217) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No trial reported this outcome. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ method of allocation concealment not stated, blinding of participants uneffective

2 Imprecision: rated 'very serious' ‐ less than 100 patients, 95% CI extends beyond the no effect point

3 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ method of randomisation is not described, allocation concealment is not stated, single‐blind.

4 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ not threat or injury to self or others, therefore had to use scale derived data for agitation.

5 Risk of bias: rated 'very serious' ‐ allocation of concealment not stated, open trial, adverse effects only reported where they occurred in ≥10% of people, sponsored by drug company.

6 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ sponsored by drug company.

7 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ 95% confidence intervals are wide.

8 Moderate risk roughly is roughly equal to that of the control group.

9 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ abnormal ECG ‐ not necessarily a serious adverse effect.

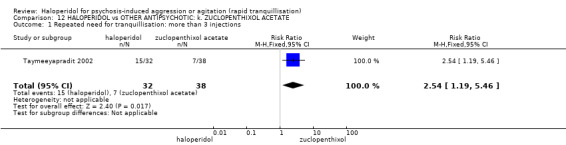

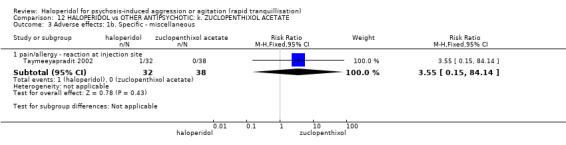

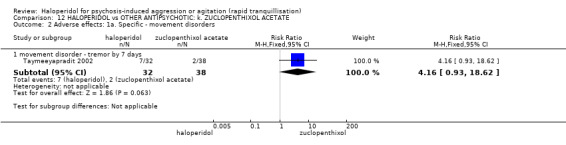

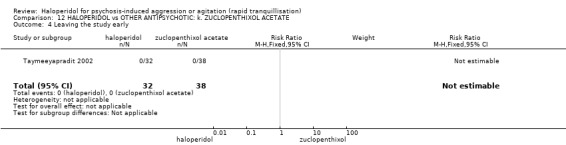

Summary of findings 12. HALOPERIDOL compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: k. ZUCLOPENTHIXOL ACETATE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared with OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS: j. ZUCLOPENTHIXOL ACETATE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS: j. ZUCLOPENTHIXOL ACETATE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS: j. ZUCLOPENTHIXOL ACETATE | HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Repeated need for rapid tranquillisation ‐ more than 3 injections | Low1 | RR 2.54 (1.19 to 5.46) | 70 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 50 per 1000 | 127 per 1000 (60 to 273) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 508 per 1000 (238 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 350 per 1000 | 889 per 1000 (417 to 1000) | |||||

| Specific behaviour ‐ threat or injury to self or others ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Global outcome ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Adverse effects: specific ‐ tremor by 7 days | Low1 | RR 4.16 (0.93 to 18.62) | 70 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,5 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 42 per 1000 (9 to 186) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 208 per 1000 (47 to 931) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 416 per 1000 (93 to 1000) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Moderate risk is roughly equal to that of the control group. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ method of randomisation not reported, open label, author suspects that rater was only blind for some outcomes. 3 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ measures more than 3 injections, not just more than 1 injection. 4 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ small study. 5 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ no serious specific adverse effect, therefore used tremor.

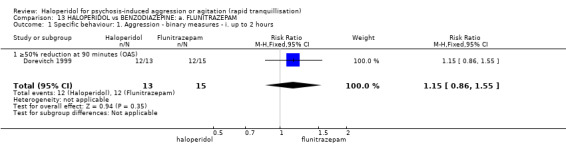

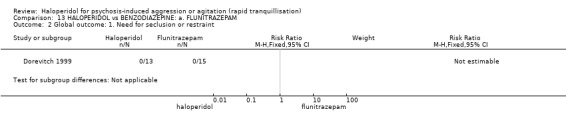

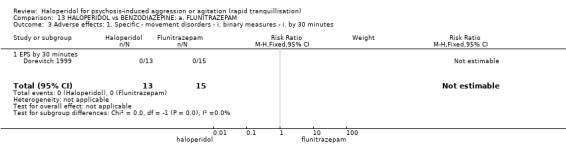

Summary of findings 13. HALOPERIDOL compared to BENZODIAZEPINE: a. FLUNITRAZEPAM for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared with BENZODIAZEPINE: a. FLUNITRAZEPAM for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: BENZODIAZEPINE: a. FLUNITRAZEPAM | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| BENZODIAZEPINE: a. FLUNITRAZEPAM | HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Repeated need for tranquillisation within 24 hours ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Specific behaviours ‐ aggression 50% reduction in OAS score at 90 minutes | Low1 | RR 1.15 (0.86 to 1.55) | 28 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 650 per 1000 | 747 per 1000 (559 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 800 per 1000 | 920 per 1000 (688 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 950 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (817 to 1000) | |||||

| Global outcome ‐ need for restraint or seclusion | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 28 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,5,6 | No events in either group. |

| Adverse effects: specific ‐ EPS | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 28 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,6,7 | No events in either group. |

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Moderate risk is roughly equal to that of the control group. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ allocation concealment not stated, described as double‐blind, however the blinding of participants and personnel are not reported, it is not clear whether all side effects are reported, small short study. 3 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ not threat or injury to self or others, inferred from OAS rating scale. 4 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ small study. 5 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ there is no measure for overall improvement, therefore inferred no overall improvement by need for restraints. 6 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ small study. 7 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ EPS can refer to a number of different symptoms rather than one specific side effect.

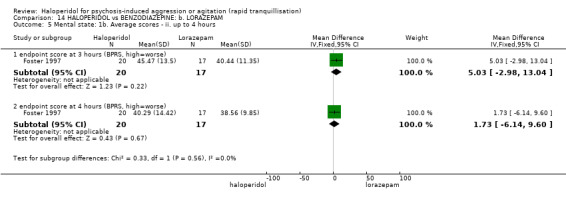

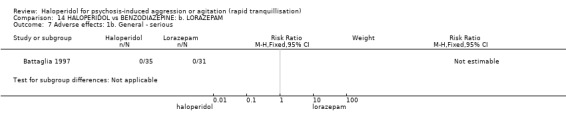

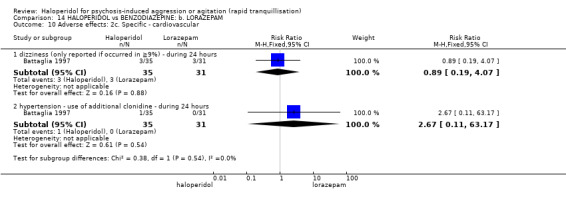

Summary of findings 14. HALOPERIDOL compared to BENZODIAZEPINE: b. LORAZEPAM for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared with BENZODIAZEPINE: b. LORAZEPAM for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients; emergency room. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: BENZODIAZEPINE: b. LORAZEPAM | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| BENZODIAZEPINE: b. LORAZEPAM | HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep not asleep at 60 minutes | Low1 | RR 1.05 (0.76 to 1.44) | 60 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4,5 | ||

| 500 per 1000 | 525 per 1000 (380 to 720) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 700 per 1000 | 735 per 1000 (532 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 900 per 1000 | 945 per 1000 (684 to 1000) | |||||

| Repeated need for rapid tranquillisation more than 1 injection | Low1 | RR 1.14 (0.91 to 1.43) | 66 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,5,6 | ||

| 500 per 1000 | 570 per 1000 (455 to 715) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 750 per 1000 | 855 per 1000 (683 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 900 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (819 to 1000) | |||||

| Specific behaviour ‐ threat or injury to self or others within 24 hours ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Global outcome: no overall improvement ‐ at 60 minutes | Low1 | RR 1.64 (0.54 to 5.03) | 44 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4 | ||

| 50 per 1000 | 82 per 1000 (27 to 252) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 150 per 1000 | 246 per 1000 (81 to 755) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 164 per 1000 (54 to 503) | |||||

| Adverse effects: specific ‐ dystonia (only reported if occurred in ≥9% during 24 hours) | Low1 | RR 3.54 (0.42 to 30.03) | 66 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,5,6 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 35 per 1000 (4 to 300) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 30 per 1000 | 106 per 1000 (13 to 901) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 177 per 1000 (21 to 1000) | |||||

| Adverse effects: specific ‐ hypertonia/rigidity (only reported if occurred in ≥9%) during 24 hours | Low7 | RR 6.22 (0.33 to 115.91) | 66 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,5,6 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Moderate7 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 311 per 1000 (17 to 1000) | |||||

| High7 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 622 per 1000 (33 to 1000) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Moderate risk is roughly equal to that of the trial control group. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'very serious' ‐ not explicitly described as randomised, allocation concealment not stated, incomplete outcome data, sponsored by drug company. 3 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ no measure for tranquillisation or asleep at 30 minutes, therefore had to use 60 minutes. 4 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ small study. 5 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ small study, sponsored by drug company. 6 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ allocation concealment is not stated, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, sponsored by drug company. 7 Low risk is roughly equal to that of the trial control group.

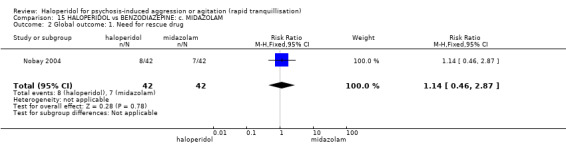

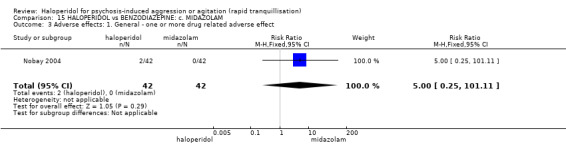

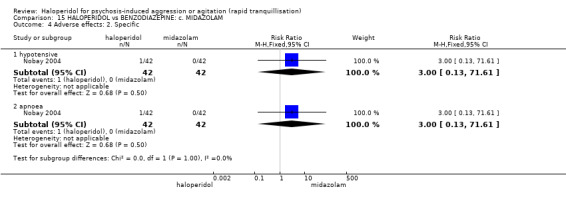

Summary of findings 15. HALOPERIDOL compared to BENZODIAZEPINE: c. MIDAZOLAM for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared with BENZODIAZEPINE: c. MIDAZOLAM for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: emergency room. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: BENZODIAZEPINE: c. MIDAZOLAM | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| BENZODIAZEPINE: c. MIDAZOLAM | HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Repeated need for rapid tranquillisation ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Specific behaviour ‐ threat or injury to self or others ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Global outcome Need for rescue drug | Low1 | RR 1.14 (0.46 to 2.87) | 84 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| 50 per 1000 | 57 per 1000 (23 to 143) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 150 per 1000 | 171 per 1000 (69 to 430) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 250 per 1000 | 285 per 1000 (115 to 717) | |||||

| Adverse effects ‐ general ‐ one or more drug‐related adverse effect | Low4 | RR 5.00 (0.25 to 101.11) | 84 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,5 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Moderate4 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 250 per 1000 (12 to 1000) | |||||

| High4 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 500 per 1000 (25 to 1000) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Medium risk is roughly equal to that of the trial control group. 2 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ no measure for overall improvement, no overall improvement inferred from need for rescue drug. 3 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ 95% confidence interval is wide. 4 Low risk is roughly equal to that of the trial control group. 5 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ no serious adverse effect, therefore used one or more adverse effects.

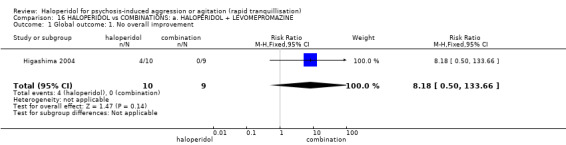

Summary of findings 16. HALOPERIDOL compared to COMBINATIONS: a. HALOPERIDOL + LEVOMEPROMAZINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared with 1. COMBINATIONS ‐ HALOPERIDOL + LEVOMEPROMAZINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: COMBINATIONS: a. HALOPERIDOL + LEVOMEPROMAZINE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| COMBINATIONS: a. HALOPERIDOL + LEVOMEPROMAZINE | HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Repeated need for tranquillisation ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Specific behaviours ‐ threat or injury to self or others ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Global outcome: general ‐ no overall improvement | Low1 | RR 8.18 (0.5 to 133.66) | 19 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (100 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 400 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (200 to 1000) | |||||

| Adverse effect: any serious, specific ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| Economic outcome ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Low risk is roughly equal to that of the trial control group. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'very serious' ‐ method of randomisation not described, allocation concealment not stated, open trial, no reporting of the presence or absence of adverse effects in the results, small study. 3 Imprecision: rated 'very serious' ‐ very small study (n = 19), 95% confidence interval is wide. 4 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ small study.

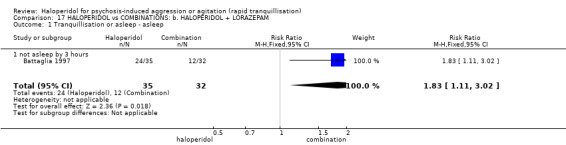

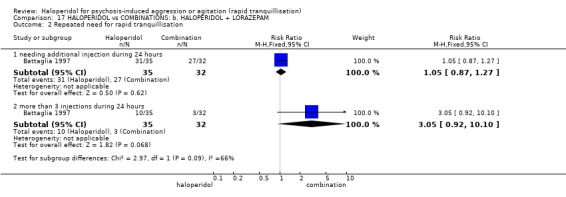

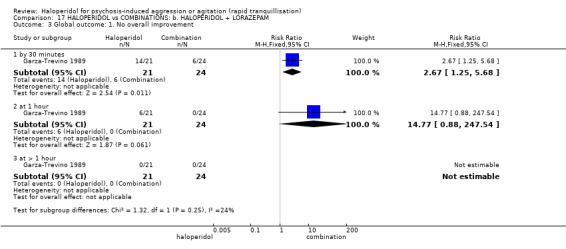

Summary of findings 17. HALOPERIDOL compared to COMBINATIONS: b. HALOPERIDOL + LORAZEPAM for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared with COMBINATIONS: b. HALOPERIDOL + LORAZEPAM for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: inpatients; emergency room. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: COMBINATIONS: b. HALOPERIDOL + LORAZEPAM | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| COMBINATIONS: b. HALOPERIDOL + LORAZEPAM | HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ not asleep by 3 hours | Low1 | RR 1.83 (1.11 to 3.02) | 67 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4,5 | ||

| 200 per 1000 | 366 per 1000 (222 to 604) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 400 per 1000 | 732 per 1000 (444 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 600 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (666 to 1000) | |||||

| Repeated need for rapid tranquillisation ‐ needing additional injection during 24 hours | Low1 | RR 1.05 (0.87 to 1.27) | 67 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,5 | ||

| 750 per 1000 | 788 per 1000 (653 to 952) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 850 per 1000 | 892 per 1000 (740 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 950 per 1000 | 997 per 1000 (827 to 1000) | |||||

| Specific behaviour ‐ threat or injury to self or others ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | |

| Global outcome: no overall improvement ‐ at 30 minutes | Low1 | RR 2.67 (1.25 to 5.68) | 45 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,6 | ||

| 50 per 1000 | 134 per 1000 (62 to 284) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 250 per 1000 | 668 per 1000 (312 to 1000) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 450 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (562 to 1000) | |||||

| Adverse effects: Specific ‐ dystonia (only reported if occurred in ≥9%) during 24 hours | Low7 | RR 8.25 (0.46 to 147.45) | 67 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,5,8 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Moderate7 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 412 per 1000 (23 to 1000) | |||||

| High7 | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 825 per 1000 (46 to 1000) | |||||

| Adverse effects: Specific ‐ hypertonia/rigidity (only reported if occurred in ≥9%) during 24 hours | Low1 | RR 2.74 (0.30 to 25.05) | 67 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,5,8 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (3 to 250) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 30 per 1000 | 82 per 1000 (9 to 751) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 137 per 1000 (15 to 1000) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Moderate risk is roughly equal to that of the control group. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ allocation concealment not stated, 2 people excluded from the efficacy analysis following randomisation, adverse effects only reported if they occurred in ≥9% of participants, sponsored by drug company. 3 Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ there are no data for 30 minutes, only 3 hours. 4 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ relatively small number of participants in each treatment arm. 5 Publication bias: rated 'strongly suspected' ‐ sponsored by drug company. 6 Risk of bias: rated 'very serious' ‐ method of randomisation not described, allocation concealment not described, open trial, no reporting regarding the presence or absence of adverse effects, duration of the study is not reported. 7 Low risk is roughly equal to that of the control group. 8 Indirectness: rated 'severe' ‐ not reported as 'severe' in this study.

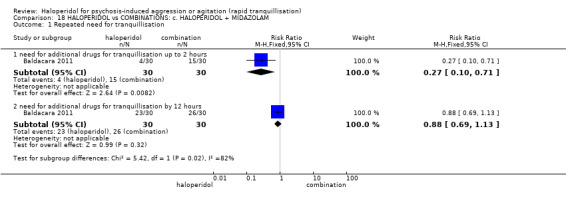

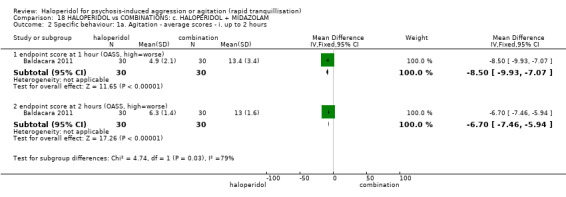

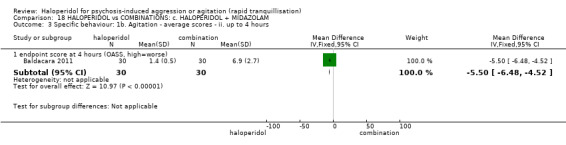

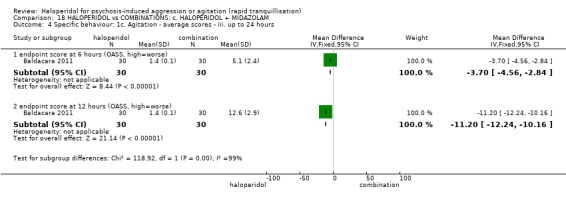

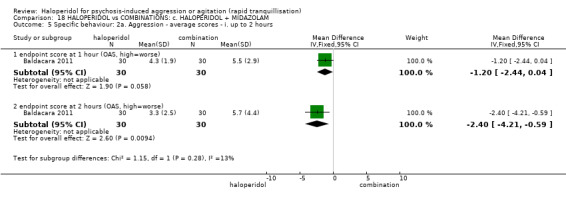

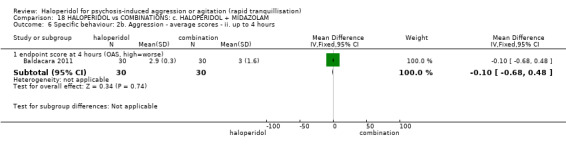

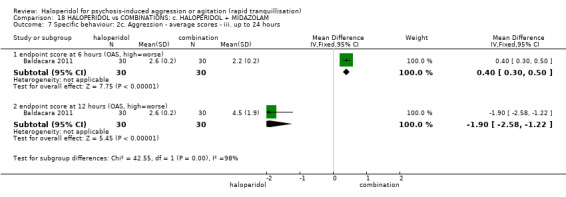

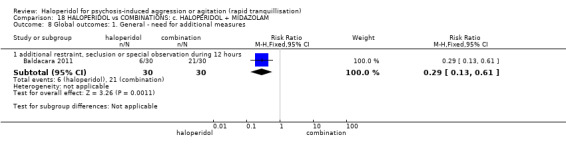

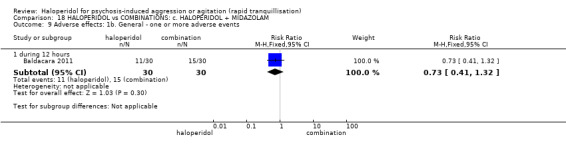

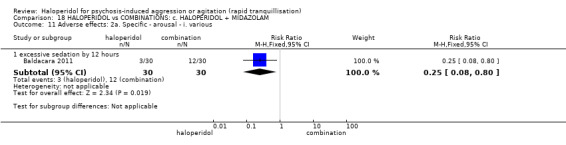

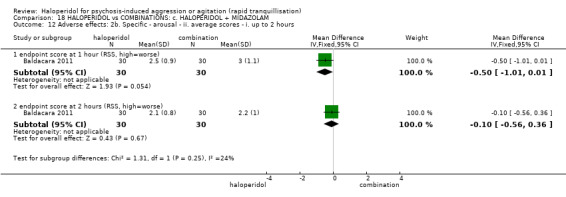

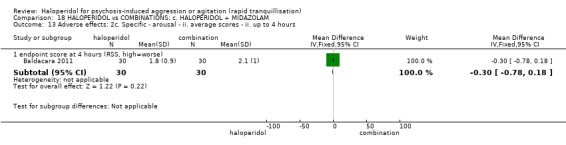

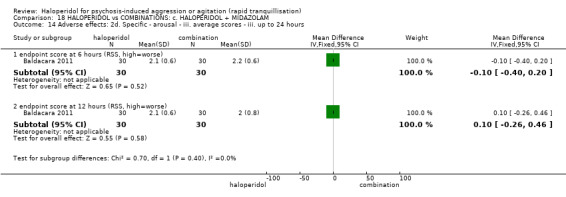

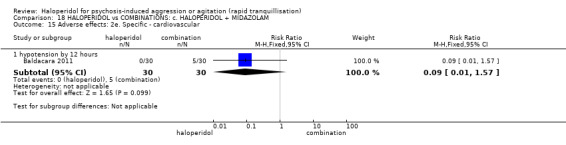

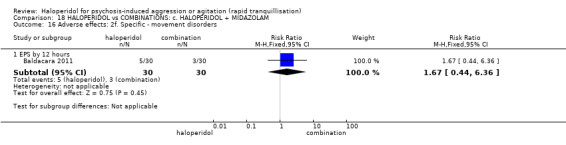

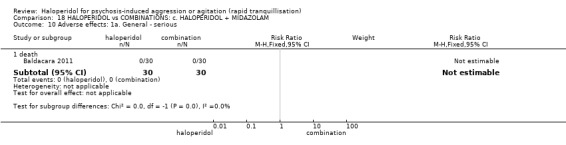

Summary of findings 18. HALOPERIDOL compared to COMBINATIONS: c. HALOPERIDOL + MIDAZOLAM for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared to COMBINATIONS: c. HALOPERIDOL + MIDAZOLAM for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: emergency room. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: COMBINATIONS: c. HALOPERIDOL + MIDAZOLAM | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with COMBINATIONS: c. HALOPERIDOL + MIDAZOLAM | Risk with HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome. |

| Repeated need for tranquillisation assessed with: need for additional drugs for tranquilisation by 12 hours | Study population | RR 0.88 (0.69 to 1.13) | 60 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 2 | ||

| 867 per 1.000 | 763 per 1.000 (598 to 979) | |||||

| Specific behaviour ‐ agitation assessed with: average endpoint scores at 12 hours on OASS | MD 11.20 lower (12.24 lower to 10.16 lower) | ‐ | 60 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 2 | ||

| Global outcome assessed with: additional restraint, seclusion or special observation during 12 hours | Low | RR 0.29 (0.13 to 0.61) | 60 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 2 | ||

| 350 per 1.000 | 102 per 1.000 (46 to 214) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 700 per 1.000 | 203 per 1.000 (91 to 427) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 950 per 1.000 | 275 per 1.000 (124 to 580) | |||||

| Adverse effects assessed with: EPS by 12 hours | Study population | RR 1.67 (0.44 to 6.36) | 60 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 2 | ||

| 100 per 1.000 | 167 per 1.000 (44 to 636) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated 'very serious' ‐ method of allocation not stated, patients instructed to not reveal their allocation although the trial is described as double blind, selective reporting, small study.

2 Imprecision: rated 'very serious' ‐ small study, 95% CI cross the no effect line.

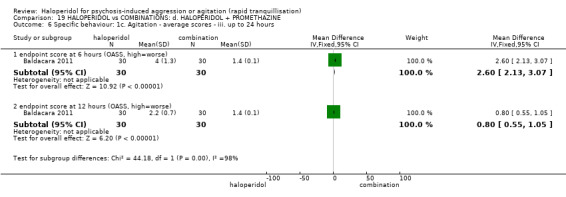

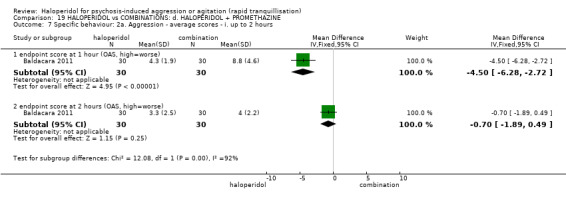

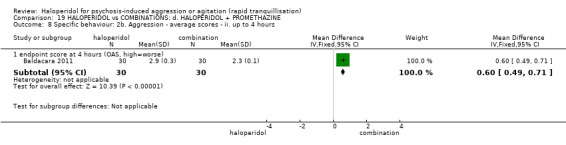

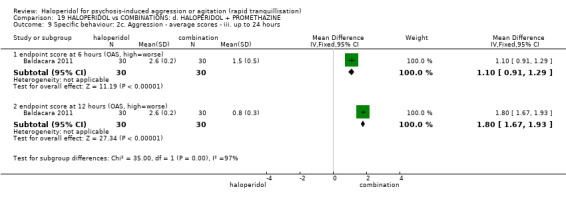

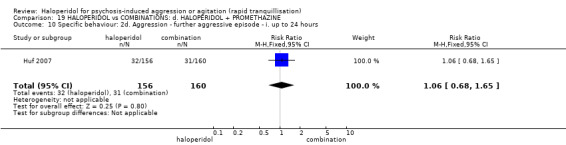

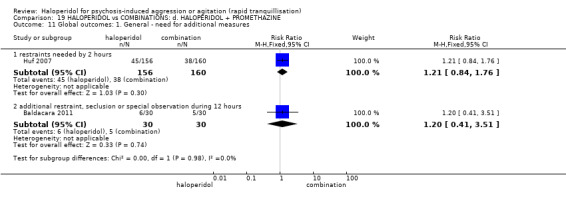

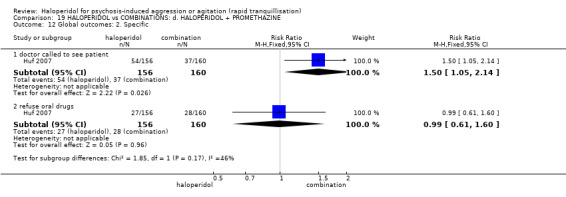

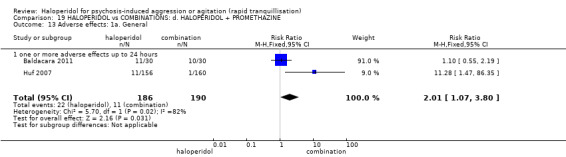

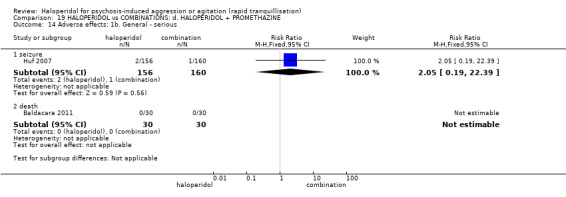

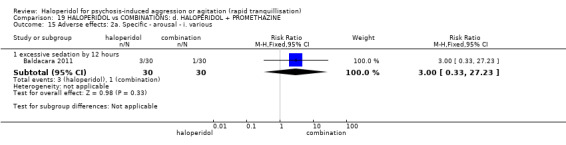

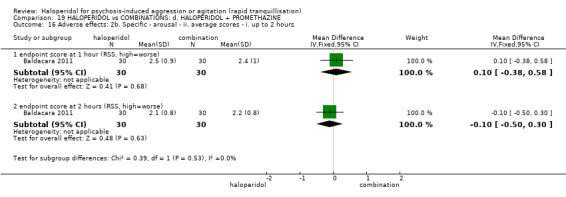

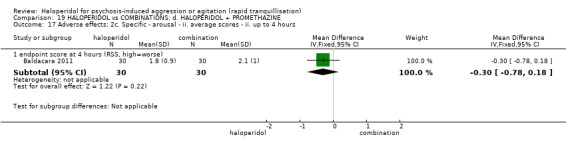

Summary of findings 19. HALOPERIDOL compared to COMBINATIONS: d. HALOPERIDOL + PROMETHAZINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation.

| HALOPERIDOL compared to COMBINATIONS: d. HALOPERIDOL + PROMETHAZINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | ||||||

| Patient or population: psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation Setting: emergency room. Intervention: HALOPERIDOL Comparison: COMBINATIONS: d. HALOPERIDOL + PROMETHAZINE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with COMBINATIONS: d. HALOPERIDOL + PROMETHAZINE | Risk with HALOPERIDOL | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep assessed with: Not tranquil or asleep at 20 minutes | Study population | RR 1.60 (1.18 to 2.16) | 316 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 281 per 1.000 | 450 per 1.000 (332 to 608) | |||||

| Repeated need for tranquillisation assessed with: need for additional drugs for tranquillisation by 2 hours | Low | RR 0.78 (0.43 to 1.41) | 376 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 3 4 | ||

| 50 per 1.000 | 39 per 1.000 (22 to 71) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 120 per 1.000 | 94 per 1.000 (52 to 169) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 450 per 1.000 | 351 per 1.000 (194 to 635) | |||||

| Specific behaviours ‐ aggression assessed with: Further aggressive episode within 24 hours | Study population | RR 1.06 (0.68 to 1.65) | 316 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 194 per 1.000 | 205 per 1.000 (132 to 320) | |||||

| Global outcomes assessed with: restraints needed by 120 minutes | Study population | RR 1.21 (0.84 to 1.76) | 316 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 5 | ||

| 238 per 1.000 | 287 per 1.000 (199 to 418) | |||||

| Adverse effects: specific ‐ acute dystonia | Low | RR 19.48 (1.14 to 331.92) | 316 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 6 | ||

| 0 per 1.000 | 0 per 1.000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 50 per 1.000 | 974 per 1.000 (57 to 1.000) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 100 per 1.000 | 1000 per 1.000 (114 to 1.000) | |||||

| Adverse effects: specific ‐ seizure | Study population | RR 2.05 (0.19 to 22.39) | 316 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 6 | ||

| 6 per 1.000 | 13 per 1.000 (1 to 140) | |||||

| Economic outcome ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No trial reported this outcome. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ open trial.