Abstract

Background

Urinary incontinence is a common and potentially debilitating problem. Stress urinary, incontinence as the most common type of incontinence, imposes significant health and economic burdens on society and the women affected. Open retropubic colposuspension is a surgical treatment which involves lifting the tissues near the bladder neck and proximal urethra in the area behind the anterior pubic bones to correct deficient urethral closure to correct stress urinary incontinence.

Objectives

The review aimed to determine the effects of open retropubic colposuspension for the treatment of urinary incontinence in women. A secondary aim was to assess the safety of open retropubic colposuspension in terms of adverse events caused by the procedure.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register, which contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, MEDLINE in process, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings (searched 5 May 2015), and the reference lists of relevant articles. We contacted investigators to locate extra studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials in women with symptoms or urodynamic diagnoses of stress or mixed urinary incontinence that included open retropubic colposuspension surgery in at least one trial group.

Data collection and analysis

Studies were evaluated for methodological quality or susceptibility to bias and appropriateness for inclusion and data extracted by two of the review authors. Trial data were analysed by intervention. Where appropriate, a summary statistic was calculated.

Main results

This review included 55 trials involving a total of 5417 women.

Overall cure rates were 68.9% to 88.0% for open retropubic colposuspension. Two small studies suggested lower incontinence rates after open retropubic colposuspension compared with conservative treatment. Similarly, one trial suggested lower incontinence rates after open retropubic colposuspension compared to anticholinergic treatment. Evidence from six trials showed a lower incontinence rate after open retropubic colposuspension than after anterior colporrhaphy. Such benefit was maintained over time (risk ratio (RR) for incontinence 0.46; 95% CI 0.30 to 0.72 before the first year, RR 0.37; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.51 at one to five years, RR 0.49; 95% CI 0.32 to 0.75 in periods beyond five years).

Evidence from 22 trials in comparison with suburethral slings (traditional slings or trans‐vaginal tape or transobturator tape) found no overall significant difference in incontinence rates in all time periods evaluated (as assessed subjectively RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.69 to 1.18, within one year of treatment, RR 1.18; 95%CI 1.01 to 1.39 between one and five years, RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.27 at five years and more, and as assessed objectively RR 1.24; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.67 within one year of treatment, RR 1.12; 95% CI 0.82 to 1.54 for one to five years follow up, RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.30 to 1.64 at more than five years). However, subgroup analysis of studies comparing traditional slings and open colposuspension showed better effectiveness with traditional slings in the medium and long term (RR 1.35; 95% CI 1.11 to 1.64 from one to five years follow up, RR 1.19; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.37).

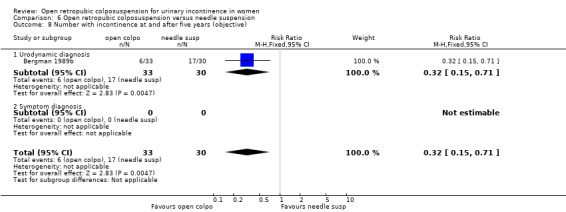

In comparison with needle suspension, there was a lower incontinence rate after colposuspension in the first year after surgery (RR 0.66; 95% CI 0.42 to 1.03), after the first year (RR 0.56; 95% CI 0.39 to 0.81), and beyond five years (RR 0.32; 95% CI 15 to 0.71).

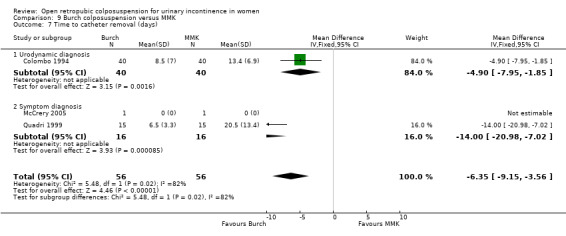

Patient‐reported incontinence rates at short, medium and long‐term follow‐up showed no significant differences between open and laparoscopic retropubic colposuspension, but with wide confidence intervals. In two trials incontinence was less common after the Burch (RR 0.38; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.76) than after the Marshall Marchetti Krantz procedure at one to five year follow‐up. There were few data at any other follow‐up times.

In general, the evidence available does not show a higher morbidity or complication rate with open retropubic colposuspension compared to the other open surgical techniques, although pelvic organ prolapse is more common than after anterior colporrhaphy and sling procedures. Voiding problems are also more common after sling procedures compared to open colposuspension.

Authors' conclusions

Open retropubic colposuspension is an effective treatment modality for stress urinary incontinence especially in the long term. Within the first year of treatment, the overall continence rate is approximately 85% to 90%. After five years, approximately 70% of women can expect to be dry. Newer minimal access sling procedures look promising in comparison with open colposuspension but their long‐term performance is limited and closer monitoring of their adverse event profile must be carried out. Open colposuspension is associated with a higher risk of pelvic organ prolapse compared to sling operations and anterior colporrhaphy, but with a lower risk of voiding dysfunction compared to traditional sling surgery. Laparoscopic colposuspension should allow speedier recovery but its relative safety and long‐term effectiveness is not yet known. A Brief Economic Commentary (BEC) identified five studies suggesting that tension‐free vaginal tape (TVT) and laparoscopic colposuspension may be more cost‐effective compared with open retropubic colposuspension.

Plain language summary

Open retropubic colposuspension for urinary incontinence in women

Importance of the Review / Background

Stress urinary incontinence is losing urine when coughing, laughing, sneezing or exercising. It can be caused by changes to muscles and ligaments holding up the bladder. Mixed urinary incontinence is also losing urine when there is an urge to void as well as when coughing and laughing. Muscle‐strengthening exercises can help, and there are surgical procedures to improve support or correct problems. A significant amount of a woman's and their family's income can be spent on management of stress urinary incontinence. Open retropubic colposuspension is an operation which involves lifting the tissues around the junction between the bladder and the urethra.

Main Findings

The review of trials found that this is an effective surgical technique for stress and mixed urinary incontinence in women, resulting in long‐term cure for most women. It provides better cure rates compared to anterior colporrhaphy a (suturing of the top wall of the vagina) and needle suspension surgery (passing a needle with sutures at the sides of the urethra to lift up the tissues beside it).New techniques, particularly sling operations (including the use of tapes to lift up the urethra)and keyhole (laparoscopic) colposuspension, look promising but need further research particularly on long‐term performance. Procedures involving surgery to insert a tape under the urethra showed better cure rates in the medium and long term, compared to open colposuspension. In terms of costs, a non‐systematic review of economic studies suggested that open retropubic colposuspension would be cheaper than laparoscopic colposuspension, but more expensive than tension‐free vaginal tape (TVT).

Adverse Events

Laparoscopic colposuspension allows for faster recovery compared to open colposuspension. Studies did not reveal a higher complication rate with open colposuspension compared with the other surgical techniques, although pelvic organ prolapse was found to be more common. Abnormal voiding was less common after open colposuspension compared to sling surgery.

Limitations

Limited information was available on the long term adverse events of open colposuspension and its effect on the quality of life.

Background

Description of the condition

Urinary incontinence has been identified by the World Health Organization as an important global health issue. It is a common and potentially debilitating problem. The overall prevalence of incontinence is reported to be between 10% to 40% of adult women, and is considered severe in about 3% to 17% (Hunskaar 2002). The wide range of prevalence estimates is due to variations in the definition of incontinence used, populations sampled, and study methods (Herzog 1990). It is believed that the true magnitude of the problem is still unknown due to under‐reporting.

Continence is achieved through an interplay of the normal anatomical and physiological properties of the bladder, urethra and sphincter, pelvic floor, and the nervous system co‐ordinating these organs. The active relaxation of the bladder, coupled by the ability of the urethra and sphincter to contain urine within the bladder by acting as a closure mechanism during filling, allow storage of urine until an appropriate time and place to void is reached. The role of the pelvic floor in providing support to the bladder and urethra, and allowing normal abdominal pressure transmission to the proximal urethra, is also considered essential in the maintenance of continence. Crucial to the healthy functioning of the bladder, urethra, sphincter and pelvic floor is co‐ordination between them, facilitated by an intact nervous system control.

Incontinence occurs when this normal relationship between the lower urinary tract components is disrupted, resulting from nerve damage or direct mechanical trauma to the pelvic organs. Advancing age, higher parity, vaginal delivery, obesity and menopause are associated with an increase in risk (Wilson 1996).

There are different types of urinary incontinence. Stress incontinence is the symptom of involuntary loss of urine during situations of increased intra‐abdominal pressure, such as coughing or sneezing. The International Continence Society defines 'urodynamic stress incontinence' as the involuntary loss of urine with increased intra‐abdominal pressure during filling cystometry, in the absence of detrusor (bladder wall muscle) contraction (Abrams 2002). Thus, urodynamic evaluation is a prerequisite for the diagnosis of urodynamic stress incontinence. It is not clear, however, especially from the clinical management standpoint, whether urodynamic diagnosis is imperative for successful treatment of stress incontinence. Therefore, this review included women diagnosed with either stress urinary incontinence (symptom alone) or urodynamic stress incontinence.

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) constitutes a huge financial economic burden to society. In the USA, the annual total direct costs of urinary incontinence in both men and women is over USD 16 billion (1995 USD) (Chong 2011), with societal costs of USD 26.2 billion (Wagner 1998). Approximately, USD 13.12 billion of the total direct costs of urinary incontinence is spent on SUI (Chong 2011; Kunkle 2015).

About 70% of this USD 13.12 billion is borne by the patients, mainly through routine care (purchasing pads and disposable underwear (diapers), laundry and dry cleaning). This constitutes a significant individual financial burden. Of the remaining 30% of costs, 14% is spent on nursing home admission, 9% on treatment, 6% on addressing complications and 1% on diagnosis (Chong 2011).

A study in the USA reported that about 1% of the median annual household income (USD 50,000 to USD 59,999 in 2006) was spent by women on incontinence management. This study estimated that women spent an annual mean cost of USD 751 to USD 1277 (2006 USD) on incontinence. This cost increases with the severity of the symptoms (Subak 2008a). The indirect cost associated exerts a social and psychological burden which is unquantifiable. (Chong 2011; Kilonzo 2004). Nevertheless, Birnbaum 2004 estimated that the annual average direct medical costs of SUI for one year (1998 USD) was USD 5642 and USD 4208 for indirect workplace costs. The cost of management and treatment of SUI appears to have increased over time, due to increasing prevalence and increased desire for improved quality of life (QOL). This in turn has resulted from improved recognition of the condition, as well as increased use of surgical and non‐surgical managements.

Two types of stress incontinence are recognised, one from a hypermobile but otherwise healthy urethra and one from deficiency of the sphincter itself (Blaivas 1988). Urethral hypermobility is a manifestation of weakened support of the proximal urethra while sphincter deficiency is an indication of compromised ability of the urethra to act as a watertight outlet. Both types were considered together for this review for three reasons. Firstly, few studies have distinguished between them; secondly, a standardised test is not available to differentiate between them accurately; and lastly, there is increasing belief that both types are present most of the time although to differing degrees.

Urge incontinence is the symptom of involuntary loss of urine associated with a sudden, strong desire to void (urgency). It is usually a manifestation of uncontrolled bladder wall contraction (detrusor overactivity). Bladder overactivity may be suspected clinically from symptoms of frequency and urgency. When detected urodynamically, bladder overactivity is termed either as 'neurogenic detrusor overactivity' if there is an underlying neurologic pathology associated with it, or 'idiopathic detrusor overactivity' when there is none. Women with urge incontinence alone were not included in this review.

Mixed incontinence is the condition of urine leakage with features of both stress and urgency. Women with mixed incontinence were included in this review. They could either have stress incontinence with symptoms of frequency and urgency, stress and urge incontinence (either diagnosed by symptom alone or by urodynamics), or stress incontinence with detrusor overactivity, or urodynamic stress incontinence with detrusor overactivity.

Description of the intervention

Treatment for urinary incontinence includes 'conservative', pharmacological and surgical interventions. Conservative management includes physical therapies (for example pelvic floor muscle training, electrical stimulation, biofeedback and vaginal weighted cones), lifestyle modification (for example weight loss, regulation of fluid intake), behavioural interventions (for example bladder retraining, timed voiding) and mechanical devices (for example urethral plugs and inserts to prevent or reduce urine leakage). Drug therapies include alpha‐adrenergic agents and duloxetine (mainly for stress urinary incontinence), anticholinergics and antispasmodics (for urge incontinence) and estrogens. Conservative therapy, with or without the use of medications, is generally undertaken before resorting to surgery. These interventions are the subject of separate Cochrane reviews.

Surgical procedures to treat stress urinary incontinence generally aim to improve the support to the urethro‐vesical junction and correct deficient urethral closure. There is disagreement, however, regarding the precise mechanism by which continence is achieved with surgical manipulation. The surgeon's preference, co‐existing pelvic floor problems, and the anatomical features of the patient and her general health condition often influence the choice of procedure. Numerous surgical methods have been described but essentially they fall into seven categories, with one category subdivided into three.

Open retropubic colposuspension.

Vaginal anterior repair (anterior colporrhaphy) (Glazener 2001).

-

Suburethral sling procedures:

traditional suburethral sling procedure (Rehman 2011);

self‐fixing suburethral sling procedure (Ford 2015);

single incision sling procedure (Nambiar 2014).

Bladder neck needle suspension (Glazener 2014).

Laparoscopic retropubic colposuspension (Dean 2006).

Periurethral injections (Kirchin 2012).

Artificial urethral sphincters.

This review focused on the first of these. Other Cochrane reviews have or will focus on the other six categories (Dean 2006; Glazener 2001; Glazener 2014; Nambiar 2014; Kirchin 2012; Ford 2015; Rehman 2011). There is also a Cochrane review which looks at treatment of recurrent stress urinary incontinence after failed minimally invasive synthetic suburethral tape surgery in women (Bakali 2013). There is as yet no Cochrane review of artificial urethral sphincters.

How the intervention might work

Retropubic colposuspension is the surgical approach of lifting the tissues near the bladder neck and proximal urethra in the area of the pelvis behind the anterior pubic bones. When it is an 'open' procedure, the approach is through an incision over the lower abdomen. There are generally three variations of open retropubic colposuspension:

Burch;

Marshall‐Marchetti‐Krantz (MMK);

Paravaginal defect repair or vagina‐obturator shelf repair.

The Burch colposuspension is the elevation of the anterior vaginal wall and paravesical tissues towards the ileopectineal line of the pelvic side wall using two to four sutures on either side (Burch 1961). The Marshall‐Marchetti‐Krantz procedure is the suspension of the vesico‐urethral junction (bladder neck) onto the periosteum of the symphysis pubis (Mainprize 1988). The paravaginal defect repair, or the vagina‐obturator shelf repair, is a modification of the Burch with placement of the sutures extended laterally and anchored at the obturator shelf rather than the ileopectineal line (Richardson 1976). It aims to close the fascial defect rather than elevate the tissues at the paravesical area.

Why it is important to do this review

The wide variety of treatment options for stress incontinence indicates the lack of a clear consensus as to which procedure is the most effective. Several organisations have produced guidelines for provision of good healthcare service (Fantl 1996; Leach 1997). However, these reports were based on studies of mixed quality and consequently some recommendations were based on consensus rather than reliable evidence. The International Consultation on Incontinence (ICI), now in its fourth iteration, is another similar initiative which uses evidence of mixed quality (www.congress‐urology.org). Systematic and methodical analyses of well‐designed randomised controlled trials have also been performed (for example Black 1996; Jarvis 1994; Novara 2008) but each has its own limitations in terms of database, methodology and, more importantly, updating in the event of new evidence.

While stress urinary incontinence is now generally managed surgically with minimally invasive procedures, particularly with the use of mid‐urethral slings, such procedures are not readily available in many countries. This is partly because of the limitations of expertise but also, more importantly, because of the difficulty in acquiring the slings, either because of their unavailability or their prohibitive cost.

Objectives

The review aimed to determine the effects of open retropubic colposuspension for the treatment of urinary incontinence in women. A secondary aim was to assess the safety of open retropubic colposuspension in terms of adverse events caused by the procedure.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised or quasi‐randomised (using for example alternation) controlled trials which involved open retropubic colposuspension in at least one arm.

Types of participants

Adult women with urinary incontinence diagnosed as having:

urodynamic stress incontinence; or

stress incontinence (clinical diagnosis); or

mixed incontinence (stress incontinence plus other urinary symptoms, eg urgency, urge incontinence, frequency whether confirmed by urodynamics or based on symptoms alone).

Classification of diagnoses was accepted as defined by the trialists.

Participants with previous incontinence surgery or with other co‐morbid diseases (for example prolapse disease) were included in the review.

Types of interventions

At least one arm of a trial involved open retropubic colposuspension to treat stress or mixed incontinence.

Comparison interventions included conservative therapy, drug therapy and other surgical techniques.

The following comparisons were made:

open retropubic colposuspension versus no treatment or sham operation for the management of urodynamic stress incontinence and for symptoms of stress or mixed incontinence (clinical diagnosis);

open retropubic colposuspension versus conservative interventions (pelvic floor muscle training, electrical stimulation, biofeedback) for the management of urodynamic stress incontinence and for symptoms of stress or mixed incontinence (clinical diagnosis);

open retropubic colposuspension versus drug therapy for the management of urodynamic stress incontinence and for symptoms of stress or mixed incontinence (clinical diagnosis);

open retropubic colposuspension versus vaginal anterior repair (anterior colporrhaphy) for the management of urodynamic stress incontinence and for symptoms of stress or mixed incontinence (clinical diagnosis);

-

open retropubic colposuspension versus sling procedures (abdominal and vaginal approach, including self‐fixing slings) for the management of urodynamic stress incontinence and for symptoms of stress or mixed incontinence (clinical diagnosis);

open retropubic colposuspension versus traditional sling procedures (abdominal and vaginal approach) for the management of urodynamic stress incontinence and for symptoms of stress or mixed incontinence (clinical diagnosis);

open retropubic colposuspension versus self‐fixing sling procedures (tension‐free vaginal tape (TVT), transobturator tape (TOT)) for the management of urodynamic stress incontinence and for symptoms of stress or mixed incontinence (clinical diagnosis);

open retropubic colposuspension versus single‐incision sling procedures for the management of urodynamic stress incontinence and for symptoms of stress or mixed incontinence (clinical diagnosis);

open retropubic colposuspension versus bladder neck needle suspension for the management of urodynamic stress incontinence and for symptoms of stress or mixed incontinence (clinical diagnosis);

open retropubic colposuspension versus laparoscopic retropubic colposuspension for the management of urodynamic stress incontinence and for symptoms of stress or mixed incontinence (clinical diagnosis);

open retropubic colposuspension versus periurethral injection procedures for the management of urodynamic stress incontinence and for symptoms of stress or mixed incontinence (clinical diagnosis);

-

methods of open retropubic colposuspension versus other methods of open retropubic colposuspension for the management of urodynamic stress incontinence and for symptoms of stress or mixed incontinence (clinical diagnosis):

Burch colposuspension versus Marshall‐Marchetti‐Krantz procedure,

Burch colposuspension versus paravaginal defect repair or vaginal obturator shelf repair,

Marshall‐Marchetti‐Krantz procedure versus paravaginal defect repair or vaginal obturator shelf repair.

Types of outcome measures

This review adopted the recommendations by the Standardisation Committee of the International Continence Society on the outcome domains of research investigating the effect of therapeutic interventions for women with urinary incontinence. These outcome domains include: the woman's observation (symptoms), quantification of symptoms, the clinician's observations (anatomical and functional) and quality of life measures (Lose 1998).

A crucial consideration in the choice of surgical intervention for benign disease is the attendant complications and consequences of the different procedures. Thus, this review included adverse events as outcome measures.

Women's observations

1. Number not cured (worse, unchanged or improved versus cured) within first year (self‐reported, subjective) 2. Number not cured (worse, unchanged or improved versus cured) after first year (self‐reported, subjective) 3. Number not cured (worse, unchanged or improved versus cured) after five years (self‐reported, subjective) 4. Number not improved (worse or unchanged versus improved or cured) within first year (self‐reported, subjective) 5. Number not improved (worse or unchanged versus improved or cured) after first year (self‐reported, subjective) 6. Number not improved (worse or unchanged versus improved or cured) after five years (self‐reported, subjective)

Quantification of symptoms

7. Number of pad changes over 24 hours (from self‐reported number of pads used) 8. Number of incontinent episodes over 24 hours (from self‐completed urinary diary) 9. Mean volume or weight of urine loss on pad tests

Clinicians' observations

10. Number not cured (worse, unchanged or improved versus cured) within first year (objective test) 11. Number not cured (worse, unchanged or improved versus cured) after first year (objective test) 12. Number not cured (worse, unchanged or improved versus cured) after five years (objective test)

Quality of life

13. General health status measures e.g. Short Form‐36 (Ware 1993) 14. Condition‐specific health measures (specific instruments designed to assess incontinence)

Surgical outcome measures

15. Length of operating time 16. Length of inpatient hospital stay 17. Time to return to normal activity level 18. Time to catheter removal

Adverse events

19. Number with perioperative surgical complications (e.g. infection, haemorrhage, etc) 20. Number with de novo urge symptoms or urge incontinence (clinical diagnosis without urodynamics) 21. Number with de novo detrusor overactivity (urodynamic diagnosis) 22. Number with voiding dysfunction or voiding difficulty (with or without urodynamic confirmation) 23. Number with recurrent or new prolapse (enterocoele, rectocoele, vaginal prolapse, uterine prolapse) 24. Number undergoing repeat incontinence surgery 25. Number with other complications inherent to the procedure (e.g. osteitis for Marshall‐Marchetti‐Krantz procedure) 26. Number with bladder perforation

Other outcomes

Non pre‐specified outcomes judged important when performing the review

The surgical outcome measures were not considered in the comparisons made between open retropubic colposuspension and conservative management or drug treatment.

For this review, the following were considered to be the primary outcomes.

Numbers not cured at one year (symptomatic)

Number not cured at one year (objective)

Number not improved at one year (symptomatic)

Number not cured at five years (symptomatic)

Condition‐specific health measures

Search methods for identification of studies

We did not impose any language or other restrictions on any of the searches.

Electronic searches

This review has drawn on the search strategy developed for the Incontinence Review Group. Relevant trials were identified from the Group's Specialised Register of controlled trials, which is described under the Incontinence Group's module in the Cochrane Library. The Register contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, MEDLINE in process, ClinicalTrials.gov, and WHO ICTRP and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings. The date of the most recent search was: 5 May 2015.

Most of the trials in the Incontinence Group Specialised Register are also contained in CENTRAL.

We searched the Incontinence Group Specialised Register using the Group's own keyword system, the search terms used are given in Appendix 1.

We performed additional searches for the Brief Economic Commentary (BEC). We conducted them in MEDLINE(1 January 1946 to March 2017), Embase (1 January 1980 to 2017 Week 12) and NHS EED (1st Quarter 2016). We ran all searches on 6 April 2017. Details of the searches run and the search terms used can be found in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of relevant articles for other possible relevant trials.

We contacted investigators to ask for other possible relevant trials, published or unpublished.

For earlier versions of this review we handsearched conference proceedings as described in Appendix 3.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors appraised the titles and, where possible, the abstracts of all studies identified by the searches to ascertain those likely to be assessments of the effectiveness of open retropubic colposuspension. We retrieved reports of potentially eligible trials in full. The review authors, without prior consideration of the results, evaluated the full reports of all possibly eligible studies for methodological quality and appropriateness for inclusion.

If studies were not randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials for incontinent women, or if they made comparisons other than those pre‐specified, we excluded them from the review. Excluded studies are listed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table with the reasons for their exclusion.

Data extraction and management

Both review authors independently undertook data extraction using a standard form containing pre‐specified outcomes. Where data may have been collected but not reported, we sought clarification from the investigators.

Subjective cure and objective cure were as study authors defined them. However if more than one form of the result was available, we used the women's report of having or not having the symptom of leakage as the measure of subjective cure and the result of the stress test or the pad test, depending on which test was used by the majority of the trials in the comparison, as the measure of objective cure. Number with voiding dysfunction included those having urinary retention and voiding difficulty, those needing a bladder drainage procedure such as intermittent or indwelling catheterisation. Time to catheter removal was considered equivalent to time to normal or spontaneous voiding, as defined by the trialists.

When more than one result for an outcome was reported due to multiple determinations at different time intervals within the trial, the latest available data set was used and entered into the table of comparisons.

We resolved any differences of opinion related to study inclusion, methodological quality or data extraction by discussion amongst the review authors and, when necessary, by referral to a third party for arbitration.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Each review author independently undertook the assessment of risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration's risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011). We based the system for classifying risk of bias of controlled trials on an assessment of the three principal potential sources of bias. These are: selection bias from insecure random allocation of treatments; attrition bias from dropouts or losses to follow‐up, particularly if there was a differential dropout rate between groups; and biased ascertainment (detection bias) of outcome where knowledge of the allocation might have influenced the measurement of outcome. In addition, we examined the calculation of sample size and definition of used terms.

Measures of treatment effect

We used the standard Cochrane software Review Manager (RevMan) to conduct this review (RevMan 2014) and processed included trial data as described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Deeks 2011). When we identified more than one eligible study, we carried out quantitative synthesis. Where appropriate, we calculated a combined estimate of treatment effect across similar studies for each pre‐specified outcome. For categorical (dichotomous) outcomes we related the numbers reporting an outcome to the numbers at risk in each group to derive a risk ratio (RR). For continuous variables, we used means and standard deviations to derive a mean difference (MD), and generated 95% confidence intervals (CI), where possible.

Where statistical synthesis of data from more than one study was not possible or not considered appropriate, we undertook a narrative review of eligible studies. We sought data on the number of women with each outcome event by allocated treatment group, irrespective of compliance and whether or not the participant was later thought to be ineligible or otherwise excluded from treatment or follow‐up, to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis when possible. For trials with missing data, we based the primary analysis upon the observed data, as reported, without imputation for missing data. We carried out sensitivity analyses using different assumptions about missing data.

When appropriate, we separated trial data into those performed for primary incontinence and those for recurrent incontinence from failed previous surgery; and those performed as a single procedure or in combination with another surgical procedure (for example hysterectomy or repair of prolapse).

Data synthesis

We used a fixed‐effect model approach to the analysis unless there was evidence of heterogeneity across studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We grouped trial data by type of incontinence, either urodynamic stress incontinence or stress or mixed incontinence, based upon a symptom classification.

When appropriate, we separated trial data into those performed for primary incontinence and those for recurrent incontinence from failed previous surgery; and those performed as a single procedure or in combination with another surgical procedure (for example hysterectomy or repair of prolapse).

We investigated differences between trials when apparent from either visual inspection of the results or when statistically significant heterogeneity was demonstrated by using the Chi2 test at the 10% probability level or assessment of the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). If there was no obvious reason for the heterogeneity (after consideration of populations, interventions, outcomes and settings of the individual trials) or it persisted despite the removal of outlying trials, we used a random‐effects model.

Results

Description of studies

The reader is directed to the Characteristics of included studies table for a more detailed account.

Search results

We screened 428 records produced by the literature search. Altogether, we have reviewed 231 full‐text articles for eligibility, of which 152 reports of 55 studies were included in the review. One trial report is still awaiting classification (Helmy 2012), pending verification if it is a new trial or a report of an already included study (Albo 2007). Of the trials that were excluded, the majority were either not randomised trials or had participants that were not incontinent at the beginning of the trial. Two references were studies comparing one sling technique with another (Debodinance 1993; Debodinance 1994). One trial (Baessler 1998) was excluded because it compared one technique of open retropubic colposuspension (Burch) with the same technique in combination with another (paravaginal repair) and another trial (Costantini 2007b) because it compared a type of prolapse repair with Burch colposuspension and the same repair without the Burch.

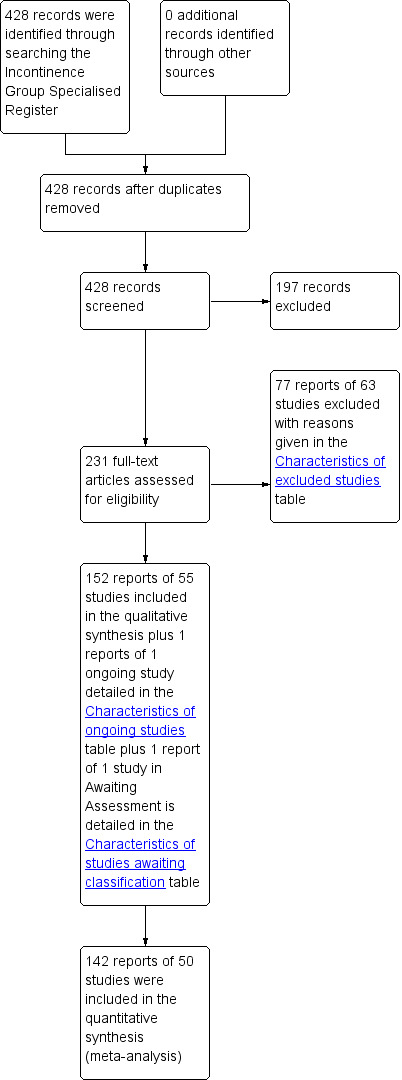

Two new trials (El‐Din Shawki 2012; Trabuco 2014), and a new report from a previously included trial (Albo 2007), were identified for inclusion in this review update (2015). The PRISMA diagram showing the flow of literature through the assessment process is given in Figure 1 (Liberati 2009).

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram.

Publication types

The primary reference for the 55 included trials were: 36 full text, published journal articles; 18 abstracts from conference proceedings; and data from one unpublished full paper (Holmes 1985) published as abstracts in three conference proceedings. We received additional information for five trials (Colombo 2000; Gilja 1998; Palma 1985; Su 1997; Ward 2002) as a result of correspondence with the trialists. One report was published in German (Enzelsberger 1996). Information and data were extracted from an English translation performed by a medical practitioner not involved in the review. One report was published in Turkish (Tuygun 2006). The information used in this review from that report was limited to that contained in the English abstract, pending translation of the full text.

Sample characteristics

The 55 trials included a total of 5417 women randomised into the different treatment groups. Outcomes from 5198 women were available for analysis (at the time of the latest assessment).

Follow up

Two trials reported complete follow‐up while 25 reported dropouts (mostly lost to follow‐up) ranging from 1.3% to 28.4% of the study population. No information regarding completeness of the follow‐up was available in the other trials.

Primary or recurrent incontinence

Twenty‐five trials included women presenting with primary urinary incontinence alone, nine included both primary and recurrent cases and one trial included only recurrent cases. Twenty trials failed to indicate whether the women studied had either primary or recurrent urinary incontinence, or had both.

Diagnosis of incontinence

For the subgroup analysis, we divided the trials into those that studied women diagnosed with urodynamically‐confirmed stress urinary incontinence and those that included women diagnosed by symptoms alone. Most of the trials included women with urodynamically‐confirmed stress urinary incontinence. Four trials (Albo 2007; Enzelsberger 1996; Kitchener 2006, Trabuco 2014) used the symptom diagnosis of stress urinary incontinence. It could not be determined whether urodynamics was used to confirm the diagnosis in five trials (Drahoradova 2004; El‐Din Shawki 2012; Palma 1985; Quadri 1999; Tuygun 2006).

The majority of the trials (36 out of 55) included women with stress urinary incontinence alone; two of these trials limited inclusion to women with low maximum urethral closing pressure (MUCP) or intrinsic sphincter deficiency (Quadri 1999; Sand 2000). Ten trials specifically mentioned exclusion of women with low maximum urethral closing pressure or other evidence of intrinsic sphincter deficiency (Bai 2005; Colombo 1994; Colombo 1996; El Barky 2005; Fatthy 2001; Kammerer‐Doak 1999; Liapis 2002; Mak 2000; McCrery 2005; Stangel‐Wojcikiewicz 2008). Three trials included women with stress urinary incontinence who had symptoms of detrusor overactivity or detrusor instability on urodynamics. Six trials included women with stress incontinence and some with mixed incontinence. One trial only had women with mixed incontinence (Osman 2003). Nine trials failed to indicate whether the population included women with mixed incontinence or mixed symptoms.

Setting

The majority of the trials were conducted in Europe (29 out of 55), of which seven were carried out in the UK. Nine were done in the United States, seven in Asia, two in Australia, one in Canada, one in South America, and five in the Middle East. Nearly all trials were carried out in university‐based hospitals, 27 of which were under the department of obstetrics and gynaecology, five in urology, 11 in centres specialising in incontinence management (urogynaecology, incontinence centres, urodynamic centres), and one in three departments (urology, gynaecology and radiology) (Klarskov 1986). One trial was performed by the minimal access unit of the department of obstetrics and gynaecology (Fatthy 2001). Five were multi‐centre trials (Albo 2007; Corcos 2001; El Barky 2005; Kitchener 2006; Ward 2002). Ward 2002 included district hospitals as trial centres. For three trials it was not clear what type of centre they were conducted in.

Intervention comparisons

The following comparators were included.

No trial was identified comparing open retropubic colposuspension with no treatment or a sham procedure.

Two trials compared open retropubic colposuspension with conservative treatment, both using physical therapy (Klarskov 1986; Tapp 1989).

One trial compared open retropubic colposuspension with anticholinergic therapy as part of a three‐armed study (Osman 2003).

Nine trials compared open retropubic colposuspension with anterior colporrhaphy, including four that included three arms in the trial (Bergman 1989a; Bergman 1989b; El‐Din Shawki 2012; Liapis 1996).

Comparisons between colposuspension and a sling procedure were investigated in 22 trials, 12 of which included the TVT procedure (Bai 2005; Drahoradova 2004; El Barky 2005; Elshawaf 2009; Halaska 2001; Han 2001; Koelbl 2002; Liapis 2002; O'Sullivan 2000; Tellez Martinez‐Fornes 2009; Wang 2003; Ward 2002) and four investigated the TOT procedure (Bandarian 2011; El‐Din Shawki 2012; Elshawaf 2009; Sivaslioglu 2007).

Comparison between open retropubic colposuspension and needle suspension procedures was performed in six trials, including two with three arms (Bergman 1989a; Bergman 1989b).

Open colposuspension was compared with laparoscopic colposuspension in 12 trials (Ankardal 2001; Burton 1994; Carey 2000; Fatthy 2001; Kitchener 2006; Mak 2000; Morris 2001; Stangel‐Wojcikiewicz 2008; Su 1997; Summitt 2000; Tuygun 2006; Ustun 2005).

One trial compared Burch colposuspension and collagen periurethral injection (Corcos 2001).

Four trials compared one technique of colposuspension with another. Four evaluated the Burch against the Marshall‐Marchetti‐Krantz procedure (Colombo 1994; Liapis 1996; McCrery 2005; Quadri 1999), one trial compared Burch colposuspension with two types of sling surgery, TVT and TOT (Elshawaf 2009) and one compared the Burch colposuspension with paravaginal repair (Colombo 1996).

The majority of the full text references either described the details of the technique in each intervention used or provided a citation, allowing verification of type of operation in ambiguous cases. This proved to be important in Gilja 1998, in which we assessed the third arm of the trial (termed as trans‐vaginal Burch or Gilja operation) to actually be a needle bladder neck suspension procedure, and hence analysed it as such. We used the name of the operation reported by the trialists to categorise a technique when a technical description of the intervention was absent, for example in trials where the only published report was an abstract. Ankardal 2001 was a three‐armed trial with two arms using laparoscopic colposuspension; one using mesh and staples and one using sutures. For this review, these two arms were combined as a comparison against open colposuspension

Outcomes

Three trials (Burton 1994; Halaska 2001; O'Sullivan 2000) did not report any outcome data that could be used in the meta‐analysis.

Definition of cure

The most consistently reported outcome among the trials was cure or success rate. In the majority, cure was defined both subjectively and objectively while subjective cure alone was reported for two studies (Demirci 2001; German 1994) and objective cure alone for four trials (Athanassopoulos 1996; Henriksson 1978; Liapis 2002; Trabuco 2014). In one study (Quadri 1985) cure was not defined. Five studies did not report cure rates (Athanasopoulos 1999; Burton 1994; Halaska 2001; Han 2001; O'Sullivan 2000). Objective cure was commonly defined by a negative stress test although others used a pad test and urodynamic parameters, either solely or as additional criteria.

Adverse effects

Twenty‐eight trials reported data on adverse events and 10 on recurrence or occurrence of prolapse, or surgery for prolapse.

Quality of life and impact of incontinence

Six studies (Corcos 2001; Fischer 2001; Kammerer‐Doak 1999; Osman 2003; Trabuco 2014; Ward 2002) included a condition‐specific outcome measure. Fischer 2001 and Kammerer‐Doak 1999 used the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ) scoring while Osman 2003 and Ward 2002 utilised the Stress‐related leakage, Emptying ability, Anatomy, Protection, Inhibition (SEAPI) and Bristol‐Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptom (B‐FLUTS) scoring systems, respectively. Fischer 2001 also used the Urinary Distress Index (UDI) scoring.. Trabuco 2014 used the SUI sub‐scale of the Medical, Epidemiological, Social Aging Questionnaire. Corcos 2001 did not specify which scoring system was used. Fifteen trials used several urodynamic parameters as outcomes.

Quality of life measures were reported in five trials (Carey 2000; Corcos 2001; Kitchener 2006; Mak 2000; Ward 2002). Ankardal 2001 used a questionnaire with VAS to assess the impact of incontinence on the quality of life.Patient satisfaction was reported in two trials (Albo 2007; Trabuco 2014).

Length of follow up

Participant follow‐up was less than one year in 13 trials. Long‐term (at least five years) follow‐up was performed in three trials, while the rest had follow‐up between one and five years.

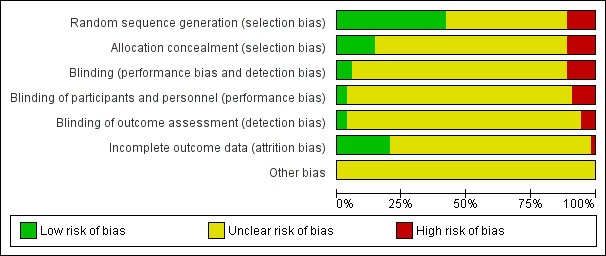

Risk of bias in included studies

Assessment of risk of bias of the included studies was difficult, in general, due to the insufficient detail provided by the authors, particularly on random allocation concealment and blinding. Whilst this might be expected in the abstracts, such was the case even in full reports. The information is summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

There were five quasi‐randomised trials where allocation was by a method of alternation (Demirci 2001; Henriksson 1978; Liapis 2002; Mundy 1983) or by date of birth (Athanassopoulos 1996).

Three trials had combined allocation methods wherein randomisation was performed in assigning the women to the major intervention arms but assignment to a specific technique depended on particular clinical characteristics (Corcos 2001; Klarskov 1986; Osman 2003):

Corcos 2001 randomly allocated women to either collagen injection therapy or surgery. Those assigned to the surgical arm were given the option of undergoing the Burch colposuspension, bladder neck suspension, or the sling procedure.

Klarskov 1986 randomly allocated women to either the conservative management or the surgical treatment arm. Within the surgical treatment arm, women were assigned to the Burch colposuspension arm or the anterior colporrhaphy arm based on the type of pelvic organ prolapse.

Osman 2003 randomly allocated women to either the drug therapy arm or the surgical arm. Women were assigned to the Burch colposuspension arm or the pubovaginal sling arm based on the Valsalva leak point pressure (VLPP) result.

In 15 trials, random sequence generation was through a random number list or computer‐generated list. One trial used tossing of a coin for randomisation (McCrery 2005). No description of the randomisation method was provided in the other trials.

Two trials (Colombo 2000; Gilja 1998) used an open list, suggesting a lack of allocation concealment. Only five trials (Ankardal 2001; Fatthy 2001; Mak 2000; Summitt 2000; Ustun 2005) specifically mentioned the use of sealed or opaque envelopes to ensure adequate concealment of allocation. One trial specifically mentioned the absence of opaque envelopes in the trial (Colombo 1996). The rest of the trials did not provide information regarding allocation concealment.

Blinding

Blinding was not mentioned in any trial except two (Carey 2000; Palma 1985,) wherein the patient, ward staff and the assessor were all blinded to the intervention, one (McCrery 2005) wherein the women were blinded to the treatment they received, and one (Trabuco 2014) where the stress test on follow up was performed by a masked observer. Liapis 2002 stated that it was a "blind study with respect to the surgeon", although it was not clear how this was implemented in the trial. Four trials (Albo 2007; Ankardal 2001; Drahoradova 2004; Kitchener 2006) stated that no blinding was attempted.

Incomplete outcome data

Thirty‐two trials did not mention if there were any withdrawals; that is, the number of participants stated as those entered into the study matched the number with outcomes at the time of assessment, without explicitly stating that there were no dropouts during the study. Five studies had 'trialist‐determined' dropouts or exclusions (Bergman 1989a; Corcos 2001; Fischer 2001; Gilja 1998; Wang 2003). SIx reported only the number and failed to indicate the reason for the withdrawals (Albo 2007; Burton 1994; Demirci 2001; Fatthy 2001; Trabuco 2014; Ward 2002). The rest cited loss to follow‐up or non‐attendance as the reason for the dropout.

Among those reporting withdrawals, 12 trials had a dropout rate of less than 10% (Bergman 1989a; Bergman 1989b; Carey 2000,Colombo 2000; Fatthy 2001; Holmes 1985; Kitchener 2006; Liapis 1996; Sand 2000; Tellez Martinez‐Fornes 2009; Trabuco 2014; Ward 2002). The rest had a dropout rate ranging from 12.9% (Bergman 1989a) to 28.4% (Gilja 1998). Of those that reported separate dropout rates according to treatment group, five trials (Corcos 2001; Fischer 2001; Morris 2001; Wang 2003; Ward 2002) had significantly different rates between the groups with more dropouts or withdrawals in the colposuspension group. In one trial (McCrery 2005) there were more women lost to follow up in the Marshall‐Marchetti‐Krantz procedure group compared to the Burch colposuspension group.

One trial (Albo 2007) reported its five year follow up data as a long‐term observational study wherein not all women initially enrolled in the trial were included. In this extension study, incontinent participants were more likely to be enrolled (85.5% vs 52.2%, P <0.0001).

Other bias

Intention‐to‐treat analysis

A form of intention‐to‐treat analysis was done in one trial (Ward 2002) wherein different assumptions and scenarios were described and corresponding results calculated. We opted to report the actual data, making no assumptions about these women. One trial (Morris 2001) stated that analysis of data was done on an intention‐to‐treat basis although the particulars were not provided. One trial deliberately did not perform an intention‐to‐treat analysis (Sand 2000). The rest of the trials did not explicitly state if intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed or if an attempt was made to do so. Details on how women crossing over between treatment groups were handled, and if outcomes among the withdrawals and dropouts were sought, were either not provided or were insufficient to allow the review authors to execute an intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Sample size

Sand 2000 and Ward 2002 did not attain the projected sample size judged necessary to detect a pre‐determined difference in the primary outcome. The sample size of Wang 2003 was based on detecting a difference in the obstructive effect of the two interventions studied rather than cure rates. One trial (Liapis 2002) attempted to perform a back calculation of the study sample's power, suggesting a marginally underpowered trial.

In general, the trial sample sizes were small, with each arm usually having a population of less than 40. The largest trial was a two‐armed trial on open colposuspension versus a sling procedure, enrolling more than 200 women per treatment arm (Albo 2007). Five larger studies (sample size more than 100) were three‐armed trials (Ankardal 2001; Bergman 1989a; Bergman 1989b; Gilja 1998; Liapis 1996). However, we had to convert three of these (Ankardal 2001; Gilja 1998; Liapis 1996) into two‐armed trials since the review authors assessed two of the three interventions to be of the same category. In Gilja 1998 the data of the Raz procedure and the trans‐vaginal Burch and Gilja groups were combined, since the latter was assessed to be a needle procedure as well. The Burch and Marshall‐Marchetti groups in Liapis 1996 were combined as the open colposuspension group in comparison with the anterior colporrhaphy group. In Arkandal 2001, the two laparoscopic colposuspension arms were combined as one comparator group against open colposuspension.

There were seven moderately‐sized two‐armed trials Carey 2000; Drahoradova 2004; Kitchener 2006; Koelbl 2002; McCrery 2005; Quadri 1985; Ward 2002).

Effects of interventions

Comparison 1: open retropubic colposuspension versus no treatment

There were no trials identified comparing open retropubic colposuspension with no treatment or sham operation.

Comparison 2: open retropubic colposuspension versus conservative treatment

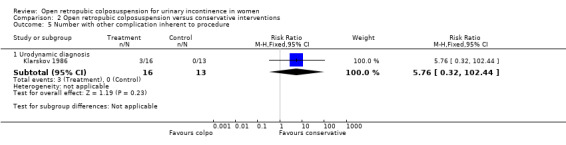

Two small studies (Klarskov 1986; Tapp 1989) compared open retropubic colposuspension with conservative treatment and involved a total of 97 women, 40 of whom underwent the surgical intervention. Klarskov 1986 compared Burch colposuspension with pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) in a subset of its study population with defective posterior bladder support. Tapp 1989 compared women undergoing colposuspension with either PFMT alone or PFMT with electrical stimulation. The methodological quality of both studies was poor. There were inconsistencies in the results reported in the two versions of Tapp 1989, primarily in the stated total number of women enrolled in the study.

The studies showed consistency of results favouring surgery for open colposuspension versus PFMT in the short term:

in subjective incontinence (Klarskov 1986), 3/16 versus 10/13 (RR 0.24; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.71, Analysis 2.1); and

objective incontinence (Tapp 1989), 6/24 versus 42/44 (RR 0.26; 95% CI 0.13 to 0.53, Analysis 2.3).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Open retropubic colposuspension versus conservative interventions, Outcome 1 Number with incontinence within first year (subjective).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Open retropubic colposuspension versus conservative interventions, Outcome 3 Number with incontinence within the first year (objective).

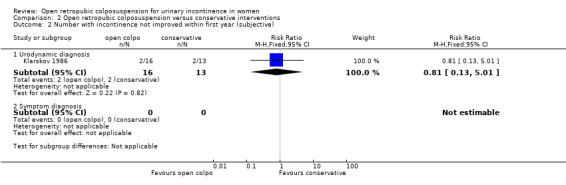

In Klarskov 1986, incontinence did improve in the majority of women, but the numbers were too small to test the difference between surgery and conservative treatment (number of women failing to improve 2/16 versus 2/13 (RR 0.81; 95% CI 0.13 to 5.01, Analysis 2.2)). Long‐term results (up to eight years) were available for Klarskov 1986 but the data could not be used as the results in the surgery group were not reported separately according to type of surgical procedure (Burch or anterior repair or both procedures).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Open retropubic colposuspension versus conservative interventions, Outcome 2 Number with incontinence not improved within first year (subjective).

Klarskov 1986 noted the occurrence of adverse events in the form of retropubic pain (1/16, 6%) and detrusor overactivity (1/16, 6%), persistent pelvic pain (1/16, 6%), and persistent dyspareunia with loss of libido (1/16, 6%) in the colposuspension group compared to no adverse events in the conservative therapy group. The very small numbers limited the significance of such results.

No formal comparisons were made between the two treatment groups in terms of surgical parameters or quality of life.

Comparison 3: open retropubic colposuspension versus drug therapy

One small trial (Osman 2003) compared open retropubic colposuspension with anticholinergic treatment in a subset of 44 women, of whom 21 received oxybutynin 5 mg twice daily with titration and 23 underwent Burch colposuspension (the remaining 24 women of the total study population underwent a pubovaginal sling procedure). The methodological quality of the trial was poor. A mixed surgical approach was taken and although the two groups were originally randomised, participants were then selected for colposuspension or sling procedure on the basis of the Valsalva leak point pressure. The estimation of effect size for this study may have been biased in favour of the drug therapy because those who failed to complete the anticholinergic treatment were excluded from the analysis.

The only useable outcome measures for this review were the subjective cure rates and a quantitative symptom scoring system as means of assessing improvement. One hundred per cent failed subjectively after drug therapy compared with three out of 23 after colposuspension (Analysis 3.1). The subjective symptom scores showed improvement in both treatment groups, with the colposuspension group having a greater degree of improvement compared to the drug therapy group (P < 0.05). Post‐treatment subjective and objective symptom scores after open retropubic colposuspension showed significantly lower (better) scores compared with oxybutynin treatment. Women undergoing colposuspension scored a mean 3.3 points lower (95% CI ‐3.96 to ‐2.64) and a mean 3.8 points lower (95% CI ‐4.59 to ‐3.01, Analysis 3.2) on subjective and objective scoring, respectively, than those scores of women receiving oxybutynin.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Open retropubic colposuspension versus drug therapy, Outcome 1 Number with incontinence within first year (subjective).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Open retropubic colposuspension versus drug therapy, Outcome 2 Condition specific health measure.

Objective cure rates were not reported. Quality of life measures and adverse events were not evaluated.

Comparison 4: open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhaphy (repair)

A total of nine trials (Berglund 1996; Bergman 1989a; Bergman 1989b; Colombo 2000; El‐Din Shawki 2012; Holmes 1985; Kammerer‐Doak 1999; Liapis 1996; Quadri 1985) compared open retropubic colposuspension with anterior colporrhaphy. These trials involved 627 women with 353 randomised to undergo retropubic colposuspension (note: these totals do not include the women from El‐Din Shawki 2012 because the distribution of the study population into the treatment groups was not reported). Two trials (Bergman 1989a; Liapis 1996) had moderate rather than small sample sizes (200 and 155 participants, respectively) although both were three‐armed trials.

The methodological quality of the studies was generally satisfactory. However, there was a lack of detail on blinding and concealment of allocation. Most trials had co‐interventions (mostly addressing prolapse when present) and there was some variation in the study populations across the trials in terms of inclusion of recurrent cases and presence of significant prolapse at study entry. Two out of the nine trials included recurrent incontinence cases (Kammerer‐Doak 1999; Quadri 1985). Six trials included women with prolapse (Bergman 1989a; Colombo 2000; Holmes 1985; Kammerer‐Doak 1999; Liapis 1996; Quadri 1985). Estimates of effect derived from these six were similar to those derived from the two trials that excluded women with prolapse.

For this section, the results for Marshall‐Marchetti‐Krantz (MMK) were considered with those for Burch colposuspension. Berglund 1996 described the technique used for open colposuspension, termed in the report as "retropubic urethropexy" as that of the MMK while Liapis 1996 had three treatment arms, wherein one arm underwent the Burch procedure, another had the MMK procedure, and anterior repair was performed on the third group. When the results of the Burch and the MMK groups were considered together in Liapis 1996, the estimates of effects were consistent with those from the other trials which performed only the Burch procedure, and no statistical heterogeneity was noted during the meta‐analysis.

However, there was evidence of statistical heterogeneity in the results of the studies for the three different outcomes examined, that is, long‐term objective cure rate, length of hospital stay and occurrence of new prolapse, which appeared to reflect Berglund 1996. We performed sensitivity analysis excluding Berglund 1996 from the meta‐analysis, and another excluding the MMK arm in Liapis 1996, to explore any difference in the results for outcomes which included data from these trials. We also carried out a subgroup analysis reporting the results from these two different operations separately (Burch versus anterior repair and MMK versus anterior repair)(Analysis 4.19, Analysis 4.20).

4.19. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 19 Number not cured within first year (subjective) Burch vs MMK.

4.20. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 20 Number not cured after first year but before five years (subjective) Burch vs MMK.

Women's observations (outcomes 4.1 to 4.3)

Evidence from seven trials evaluating a total of 695 women (with assessments available at different time periods) showed a lower incontinence rate for subjective cure after open retropubic colposuspension than after anterior colporrhaphy. Such benefit was maintained over time:

incontinence rates 9% versus 19% (RR 0.46; 95% CI 0.30 to 0.72) before the first year (Analysis 4.1);

14% versus 36% (RR 0.37; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.51) at one to five years (Analysis 4.2); and

28% versus 53% (RR 0.49; 95% CI 0.32 to 0.75) in periods beyond five years (Analysis 4.3).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 1 Number with incontinence within first year (subjective).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 2 Number with incontinence after first year but before five years (subjective).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 3 Number with incontinence after five years (subjective).

A sensitivity analysis excluding Berglund 1996 (because the operation tested was MMK rather than Burch) removed the heterogeneity and strengthened the long‐term result in favour of the Burch procedure (RR 0.29; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.52).

Quantification of symptoms (outcome 4.12)

Data from one small trial (Berglund 1996) showed no difference in the two‐hour pad test results but with a wide confidence interval (MD 1.1 gm; 95% CI ‐4.41 to 6.61, Analysis 4.7).

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 7 Volume/weight of urine loss in 2 hour pad test.

Clinician's observations (outcomes 4.9 to 4.11)

Consistent with the results for subjective cure, there was also evidence that open retropubic colposuspension was more effective than anterior colporrhaphy for objective cure rates. The benefit was maintained over time:

incontinence rates 9% versus 25% (RR 0.36; 95% CI 95% 0.22 to 0.58) within one year (Analysis 4.4);

16% versus 44% (RR 0.34; 95% CI 0.25 to 0.47) at one year but before five years (Analysis 4.5); and

26% versus 54% (RR 0.48; 95% CI 0.31 to 0.73) after five years (Analysis 4.6).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 4 Number with incontinence within the first year (objective).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 5 Number with incontinence after first and before five years (objective).

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 6 Number with incontinence at and after five years (objective).

As would be expected, sensitivity analyses excluding Berglund 1996 removed the heterogeneity. There was some indirect evidence that the Burch procedure was more effective than the MMK procedure (Analysis 4.19).

Overall, the risk of failing to cure urinary incontinence through open retropubic colposuspension was only half that of anterior repair, with an estimated absolute risk difference (ARR) of around 20% (ARR 0.21; 95% CI 0.15 to 0.27). To put this another way, for every five women treated, one extra was cured after open retropubic colposuspension.

Quality of life measures (outcome 4.14)

There was only one small trial (Kammerer‐Doak 1999) that investigated the impact of both types of surgery on the quality of life through an incontinence rating score. Scores improved in both treatment groups. There was a small (less than 1 point) but statistically significantly better improvement in the quality of life scores in the open retropubic colposuspension group compared to the anterior colporrhaphy group (MD ‐0.59; 95% CI ‐1.11 to ‐0.07, Analysis 4.8).

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 8 Condition specific health measure.

Surgical outcome measures (outcomes 4.16 to 4.19)

Data from one small trial (Holmes 1985) showed a longer operating time for colposuspension (MD 14.40 minutes, 95% CI 5.43 to 23.37, Analysis 4.9).

4.9. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 9 Operative time (minutes).

The pattern of results for length of hospital stay differed between the two trials with data. In one (Berglund 1996), women had an average three fewer days in hospital after open retropubic colposuspension compared with anterior repair, whereas the other trial (Colombo 2000) showed no difference. Because of the heterogeneity no attempt was made to derive an estimate from combined data (Analysis 4.10).

4.10. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 10 Length of hospital stay (days).

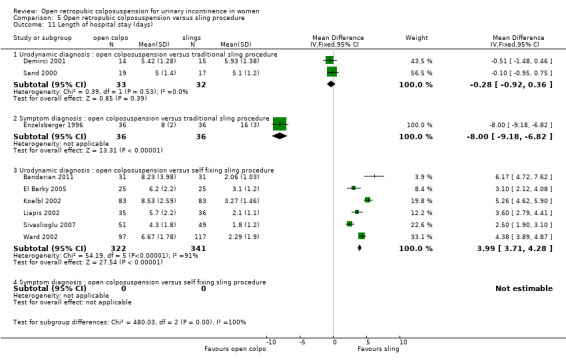

The estimates for the time to catheter removal post‐operatively, available from three trials (outcome 4.19) (Bergman 1989a; Bergman 1989b; Holmes 1985) were not statistically significantly different (MD ‐0.28 days, 95% CI ‐0.83 to 0.27, Analysis 4.11).

4.11. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 11 Time to catheter removal (days).

Adverse events (outcomes 4.20 to 4.26)

The included trials reported adverse events in different ways, with only one or two providing data for a particular event. Thus, there were limited data to draw conclusions confidently for each adverse event. Based on two trials with data, the number of perioperative complications was significantly lower with open retropubic colposuspension (outcome 4.20: RR 0.39; 95% CI 0.19 to 0.83, Analysis 4.12). Holmes 1985 and Berglund 1996 reported more wound infections in the retropubic colposuspension group, but more haemorrhage (Holmes 1985) and more positive urine cultures (Berglund 1996) in the anterior repair group. Bergman 1989a reported no difference in post‐operative complications between the treatment groups, although specific data were not provided.

4.12. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 12 Number of perioperative surgical complications.

Estimates of the risk for de novo urge symptoms and urge incontinence, and risk for detrusor were inconclusive as the data were not statistically significant and had wide confidence intervals (Colombo 2000; Holmes 1985; Kammerer‐Doak 1999; Liapis 1996). In three trials with data, there were fewer women with de novo urge symptoms or incontinence after open retropubic colposuspension but the difference was not statistically significant (RR 0.53; 95% CI 0.25 to 1.14, Analysis 4.13). In four small trials with data there was no statistically significant difference in the risk for developing urodynamically demonstrable de novo detrusor overactivity post‐operatively (event rates: 8% versus 6% (RR 1.26; 95% CI 0.54 to 2.94, Analysis 4.14)).

4.13. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 13 Number with de novo urge symptoms and urge incontinence.

4.14. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 14 Number with de novo detrusor instability.

Four trials evaluated the risk for voiding difficulty after open retropubic colposuspension and anterior repair. Across the four trials there were only three events of voiding difficulty, all occurring in the open colposuspension group (Analysis 4.15). For this reason no combined estimate was derived.

4.15. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 15 Number with voiding difficulty.

Data on the risk of recurrent or new prolapse were available from five trials (Bergman 1989b; Colombo 2000; Holmes 1985; Liapis 1996; Quadri 1985). It is of note that all trials had an adequate mean follow up of at least one year at the time of assessment of the prolapse. However, there was significant heterogeneity in the results between the trials and the groups were statistically different in only two trials (Colombo 2000; Quadri 1985). Although there were more women with prolapse in the open colposuspension groups (16% versus 5%), this did not reach statistical significance when a random‐effects model was used (RR 2.51; 95% CI 0.62 to 10.10, Analysis 4.16). Examination of study design and population characteristics across the trials did not reveal any possible source of difference that could explain the heterogeneity. The largest difference in post‐operative prolapse rates was demonstrated in Colombo 2000, which had a very long follow‐up of at least eight years and showed a risk difference of over 50% in favour of anterior repair.

4.16. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 16 Number with new or recurrent prolapse.

Consistent with the findings on cure, fewer women in the colposuspension group had repeat anti‐incontinence surgery (6.3% versus 23.4% (RR 0.11; 95% CI 0.04 to 0.30, Analysis 4.17); estimated absolute difference 21% from the three trials with data).

4.17. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Open retropubic colposuspension versus anterior colporrhapy, Outcome 17 Number with repeat anti‐incontinence surgery.

Comparison 5: open retropubic colposuspension versus sling procedures (traditional and self‐fixing slings)

Twenty‐two trials (Albo 2007; Bai 2005; Bandarian 2011; Demirci 2001; Drahoradova 2004; El Barky 2005; El‐Din Shawki 2012; Elshawaf 2009; Enzelsberger 1996; Fischer 2001; Halaska 2001; Han 2001; Henriksson 1978; Koelbl 2002; Liapis 2002; O'Sullivan 2000; Sand 2000; Sivaslioglu 2007; Tellez Martinez‐Fornes 2009; Trabuco 2014; Wang 2003; Ward 2002) compared open retropubic colposuspension with sling procedures. These involved 2343 randomised women, at least 1089 of whom underwent colposuspension. One trial (El‐Din Shawki 2012) involving 60 participants did not specify the numbers allocated to the three treatment groups.

Traditional slings

Six trials involved traditional suburethral sling procedures. Two trials involved the pubovaginal sling technique using autologous rectus muscle fascia (Albo 2007; Demirci 2001). Enzelsberger 1996 used the lyodura sling, Henriksson 1978 used the Zoedler sling, and Sand 2000 used the Gortex type synthetic material. Fischer 2001 did not specify the sling material.

Midurethral tapes

Twelve trials (Bai 2005; Drahoradova 2004; El Barky 2005; Elshawaf 2009; Halaska 2001; Han 2001; Koelbl 2002; Liapis 2002; O'Sullivan 2000; Tellez Martinez‐Fornes 2009; Wang 2003; Ward 2002) used the tension‐free vaginal tape (TVT) as the sling procedure. One of these trials was a three‐armed study which compared open Burch colposuspension, the transobturator tape procedure (TOT), and the TVT (Elshawaf 2009). Three trial used TOT as the sling procedure (Bandarian 2011; El‐Din Shawki 2012; Sivaslioglu 2007).

One trial did not specify whether TVT or TOT procedure was the approach taken (Trabuco 2014). In one trial (Trabuco 2014), women in both treatment groups underwent abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse, in addition to the incontinence procedure.

Data issues

We distributed data on the subjective cure rates of the Burch colposuspension group from Bai 2005 between the subcategories of open colposuspension versus traditional sling procedures and open colposuspension versus self‐fixing sling procedures to avoid double counting for the meta‐analysis. For Elshawaf 2009, we planned to combine the data for the TOT and TVT groups. However, we could not extract any usable data from the report as the results were limited to a narrative description.

We could not enter data from Halaska 2001 into RevMan (RevMan 2014) as the results of a visual analogue scale were presented in a graph and it was not clear how the figures were derived. A conference abstract on a subset of women from that trial reported that the results in two‐ and six‐month follow‐up revealed no difference in the clinical outcomes between TVT and Burch. It was also reported that TVT was superior to the Burch procedure in terms of restoring normal sexual activity. One study (Henriksson 1978) reported equivalent results in both treatment groups but no data were provided. Outcomes studied in O'Sullivan 2000, which were based on tissue collagen analysis results, were not used in this review. We used data from the longest follow‐up from trials which reported the event rates at different time periods In the analysis of the risk for prolapse.

Albo 2007 used various criteria to define success. We selected symptoms as the criterion to define subjective cure (using self‐reported incontinence using a questionnaire) and the pad test results to define objective cure because the other trials in this comparison used these parameters to define subjective and objective cure.

Only three trials (Albo 2007; Sand 2000; Ward 2002) had long‐term results (at and after five years). However, the extension study of Albo 2007 only included a proportion of the initially enrolled study population (482/665) and incontinent women were more likely to enrol in the follow up study (P <0.0001). The numbers used in the analysis for the number of incontinent women, based on self‐reported incontinence questionnaires, were difficult to determine, as the paper stated the number of women who completed the study at five years but data for more women were available for different outcomes. Hence, the denominators for the continence rates used in this review were only derived values based on reported percentages and counts in the paper. The inclusion of this long‐term outcomes data, being part of an observational study, rather than part of the randomized trial, was subjected to sensitivity analysis.

While El‐Din Shawki 2012 reported outcomes, we were not able to include the data in the review because it did not specify how the participants were allocated across the three treatment groups.

Women's observations (outcomes 5.1 to 5.6)

Short‐term cure

Evidence from eight trials including traditional and self‐fixing slings (Bai 2005; Demirci 2001; Drahoradova 2004; El Barky 2005; Sand 2000; Sivaslioglu 2007; Tellez Martinez‐Fornes 2009; Ward 2002) showed no statistically significant difference between the two treatment groups in the risk for incontinence as assessed subjectively (RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.69 to 1.18, Analysis 5.1) within one year of treatment. The confidence interval was wide, however, and from the data we cannot rule out a difference favouring open colposuspension or slings.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Open retropubic colposuspension versus sling procedure, Outcome 1 Number with incontinence within first year (subjective).

Subgroup analysis of those trials including traditional slings only showed no statistical difference between open colposuspension and traditional slings but the confidence interval was wide and again we cannot rule out favouring either open colposuspension or traditional slings (RR 1.92; 95% CI 0.57 to 6.50, Analysis 5.1).

The meta‐analysis of five trials (Bai 2005; El Barky 2005; Sivaslioglu 2007; Tellez Martinez‐Fornes 2009; Ward 2002) using the TVT procedure (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.67 to 1.16, Analysis 5.1) demonstrated a narrower confidence interval but not narrow enough to say there was no difference between the procedures.

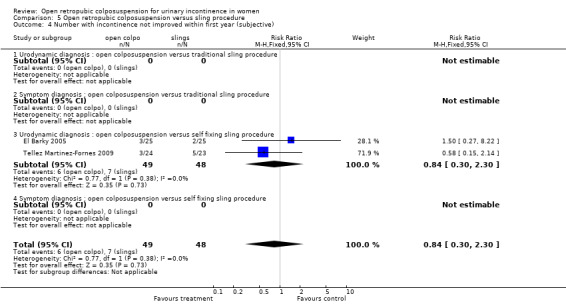

One small trial (El Barky 2005) was too small to provide evidence of any difference in subjective improvement rates within one year between open colposuspension and sling procedures (Analysis 5.4).

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Open retropubic colposuspension versus sling procedure, Outcome 4 Number with incontinence not improved within first year (subjective).

Medium‐term cure

Data for incontinence rates at one‐ to five‐year follow‐up were available from six trials (Albo 2007; Enzelsberger 1996; Sivaslioglu 2007; Tellez Martinez‐Fornes 2009; Wang 2003; Ward 2002). The summary statistic, combining traditional slings and self‐fixing slings, showed a lower incontinence rate in women who had sling procedures (RR 1.18; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.39, Analysis 5.2), which was primarily due to the results of the Albo 2007 trial which used the traditional sling procedure. Data from studies using traditional slings alone showed lower incontinence rates with traditional slings (RR 1.35; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.37). Data from the TVT trials alone showed no clear difference in medium‐term subjective incontinence rate (Analysis 5.2) or improvement rate (Analysis 5.5) between open colposuspension and the TVT procedure.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Open retropubic colposuspension versus sling procedure, Outcome 2 Number with incontinence after first year but before five years (subjective).

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Open retropubic colposuspension versus sling procedure, Outcome 5 Number with incontinence not improved after first year but before five years (subjective).

Long‐term cure

Data beyond five years was provided by three trials (Albo 2007; Sand 2000; Ward 2002), demonstrating no overall significant difference in effects (RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.27, Analysis 5.3). However, traditional slings continued to be more effective than open colposuspension at long term follow up in one trial (RR1.19; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.37) (Albo 2007).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Open retropubic colposuspension versus sling procedure, Outcome 3 Number with incontinence after five years (subjective).

Clinician's observations (outcomes 5.9 to 5.11)

Consistent with the results in the subjective assessment of cure, in objective incontinence rates there were no statistically significant differences within any time periods:

RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.75 within one year of treatment, Analysis 5.6;

RR 1.12; 95% CI 0.82 to 1.54 for one to five years follow up, Analysis 5.7; and

RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.30 to 1.64 at more than five years, Analysis 5.8.

5.6. Analysis.