Abstract

Background

Hypertension is an important risk factor for adverse cardiovascular events including stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure and renal failure. The main goal of treatment is to reduce these events. Systematic reviews have shown proven benefit of antihypertensive drug therapy in reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality but most of the evidence is in people 60 years of age and older. We wanted to know what the effects of therapy are in people 18 to 59 years of age.

Objectives

To quantify antihypertensive drug effects on all‐cause mortality in adults aged 18 to 59 years with mild to moderate primary hypertension. To quantify effects on cardiovascular mortality plus morbidity (including cerebrovascular and coronary heart disease mortality plus morbidity), withdrawal due adverse events and estimate magnitude of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) lowering at one year.

Search methods

The Cochrane Hypertension Information Specialist searched the following databases for randomized controlled trials up to January 2017: the Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (from 1946), Embase (from 1974), the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and ClinicalTrials.gov. We contacted authors of relevant papers regarding further published and unpublished work.

Selection criteria

Randomized trials of at least one year' duration comparing antihypertensive pharmacotherapy with a placebo or no treatment in adults aged 18 to 59 years with mild to moderate primary hypertension defined as SBP 140 mmHg or greater or DBP 90 mmHg or greater at baseline, or both.

Data collection and analysis

The outcomes assessed were all‐cause mortality, total cardiovascular (CVS) mortality plus morbidity, withdrawals due to adverse events, and decrease in SBP and DBP. For dichotomous outcomes, we used risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) and a fixed‐effect model to combine outcomes across trials. For continuous outcomes, we used mean difference (MD) with 95% CI and a random‐effects model as there was significant heterogeneity.

Main results

The population in the seven included studies (17,327 participants) were predominantly healthy adults with mild to moderate primary hypertension. The Medical Research Council Trial of Mild Hypertension contributed 14,541 (84%) of total randomized participants, with mean age of 50 years and mean baseline blood pressure of 160/98 mmHg and a mean duration of follow‐up of five years. Treatments used in this study were bendrofluazide 10 mg daily or propranolol 80 mg to 240 mg daily with addition of methyldopa if required. The risk of bias in the studies was high or unclear for a number of domains and led us to downgrade the quality of evidence for all outcomes.

Based on five studies, antihypertensive drug therapy as compared to placebo or untreated control may have little or no effect on all‐cause mortality (2.4% with control vs 2.3% with treatment; low quality evidence; RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.13). Based on 4 studies, the effects on coronary heart disease were uncertain due to low quality evidence (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.19). Low quality evidence from six studies showed that drug therapy may reduce total cardiovascular mortality and morbidity from 4.1% to 3.2% over five years (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.91) due to reduction in cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity (1.3% with control vs 0.6% with treatment; RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.64). Very low quality evidence from three studies showed that withdrawals due to adverse events were higher with drug therapy from 0.7% to 3.0% (RR 4.82, 95% CI 1.67 to 13.92). The effects on blood pressure varied between the studies and we are uncertain as to how much of a difference treatment makes on average.

Authors' conclusions

Antihypertensive drugs used to treat predominantly healthy adults aged 18 to 59 years with mild to moderate primary hypertension have a small absolute effect to reduce cardiovascular mortality and morbidity primarily due to reduction in cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity. All‐cause mortality and coronary heart disease were not reduced. There is lack of good evidence on withdrawal due to adverse events. Future trials in this age group should be at least 10 years in duration and should compare different first‐line drug classes and strategies.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Middle Aged, Young Adult, Antihypertensive Agents, Antihypertensive Agents/adverse effects, Antihypertensive Agents/therapeutic use, Bendroflumethiazide, Bendroflumethiazide/therapeutic use, Blood Pressure, Blood Pressure/drug effects, Cause of Death, Coronary Disease, Coronary Disease/mortality, Coronary Disease/prevention & control, Hypertension, Hypertension/drug therapy, Hypertension/mortality, Methyldopa, Methyldopa/therapeutic use, Myocardial Infarction, Myocardial Infarction/mortality, Myocardial Infarction/prevention & control, Patient Dropouts, Patient Dropouts/statistics & numerical data, Propranolol, Propranolol/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Stroke, Stroke/mortality, Stroke/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Treatment for hypertension in adults aged 18 to 59 years

Review question

We wanted to study the benefits and harms of using blood pressure lowering (antihypertensive) medicines in adults aged 18 to 59 years with raised blood pressure (hypertension).

We searched the available medical literature to find all the trials that had assessed this question. The data included in this review is up to date as of January 2017.

Background

Hypertension increases the risk of stroke, heart attacks and heart failure; therefore, the main goal of treatment with antihypertensive medicines is to reduce this risk. There is substantial evidence mostly in people older than 60 years that antihypertensive therapy reduces these outcomes.

Study characteristics

We found seven studies that randomly assigned 17,327 people aged 18 to 59 years with hypertension to either antihypertensive medicines or placebo (pretend treatment)/no treatment. The average duration of treatment was five years. Medicine classes studied in most people included medicines called thiazide diuretics or beta‐blockers.

Key results

Treatment may have little or no effect on death from any cause compared with placebo or no treatment (2.4% with placebo/no treatment versus 2.3% with treatment; low quality evidence) and it may reduce the number of people experiencing heart disease or death from heart disease from 4.1% to 3.2% (low quality evidence). It may reduce stroke by a small amount from 1.3% to 0.6% (low quality evidence). We are not certain about the effects of treatment on the number of people who had blocked arteries (low quality evidence). Withdrawal due to side effects increased from 0.7% to 3.0% although the quality of evidence for this result was very low. The effects of treatment on blood pressure varied between the studies and we are uncertain as to how much of a difference treatment makes on average.

Conclusions

Antihypertensive medicines for adults aged 18 to 59 years with raised blood pressure have a small beneficial effect to reduce stroke. However, death due to all‐causes and heart attack were not reduced and withdrawals due to side effects were increased.

Quality of evidence

The overall evidence was graded as low or very low quality.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antihypertensive drug therapy compared to control for hypertension in adults aged 18 to 59 years.

| Antihypertensive drug therapy compared to control for hypertension in adults aged 18 to 59 years | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults aged 18‐59 years with primary hypertension (mild to moderate systolic or diastolic hypertension) Setting: outpatient Intervention: antihypertensive drug therapy (mean duration: 5 years) Comparison: control (placebo or untreated) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with antihypertensive drug therapy | |||||

| All‐cause mortality | 24 per 1000 | 23 per 1000 (19 to 28) | RR 0.94 (0.77 to 1.13) | 16,776 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1,2 | ‐ |

| Total cardiovascular mortality + morbidity | 41 per 1000 | 32 per 1000 (27 to 37) | RR 0.78 (0.67 to 0.91) | 17,278 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1,3 | ARR 0.9%, NNTB = 112 |

| Cerebrovascular mortality + morbidity | 13 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (5 to 9) | RR 0.46 (0.34 to 0.64) | 17,278 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1,3 | ARR 0.7%, NNTB 143 |

| Coronary heart disease mortality + morbidity | 26 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (21 to 31) | RR 0.99 (0.82 to 1.19) | 16,241 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1,3 | ‐ |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events | 7 per 1000 | 32 per 1000 (11 to 93) | RR 4.82 (1.67 to 13.92) | 1,223 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1,2,4 | ARI 3.8%, NNTH 27 |

|

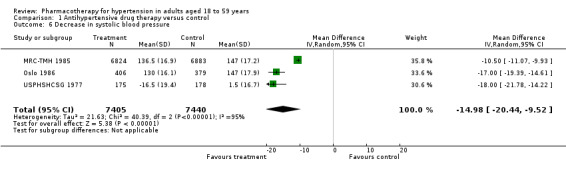

Decrease in SBP5 at end of 1 year |

The mean SBP was 0 | MD 14.98 lower (20.44 lower to 9.52 lower) | ‐ | 14,845 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1,3,7 | ‐ |

|

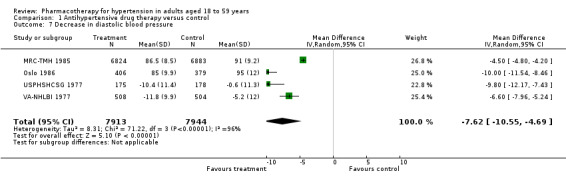

Decrease in DBP6 at end of 1 year |

The mean DBP was 0 | MD 7.62 lower (10.55 blower to 4.69 lower) | ‐ | 15,857 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1,3,7 | ‐ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ARI: absolute risk increase; ARR: absolute risk reduction; CI: confidence interval; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; MD: mean difference; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat to for an additional harmful outcome; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SBP: systolic blood pressure. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1Several additional trials met the inclusion criteria but did not report data in the 18‐ to 59‐year‐old subgroup of participants (which are listed under Characteristics of excluded studies table).

2Imprecision due to wide confidence interval.

3High risk of bias due to lack of blinding of physician and participants as well as incomplete outcome data reporting in the MRC‐TMH trial.

4Only 3 out of 7 included trials reported this outcome. The data from MRC‐TMH 1985 for this subgroup were not available. High risk of attrition bias and unclear risk of reporting bias of the USPHSHCSG 1977 study which contributes 100% weight to the effect size.

5The range of change in SBP in the control group ranged from increase by 1.5 mmHg to decrease from 9 to 14 mmHg.

6The range of decrease in DBP in the control group ranged from 0.6 mmHg to 7 mmHg.

7Significant heterogeneity (I2 > 95%).

Background

Description of the condition

Elevated blood pressure (BP), commonly called hypertension, is an important healthcare problem internationally. Hypertension has been defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of at least 140 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of at least 90 mmHg, or both. The worldwide prevalence of elevated BP is about 26% of the adult population, and the prevalence increases with age (Kearney 2005). Elevated blood pressure is a major contributor to adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular disease; CVD) and has been estimated to contribute 4.5% to the global disease burden (WHO 2003). People of younger age (less than 60 years) have a lower prevalence of hypertension than older people.

The main goal of antihypertensive treatment is to reduce strokes, myocardial infarctions (MI) and heart failure. Several systematic reviews have shown benefit of antihypertensive drug therapy in reducing cardiovascular mortality and morbidity primarily in people over 60 years of age (Collins 1990; Thijs 1992; Psaty 1997; Gueyffier 1999; Psaty 2003; Musini 2009; Wright 2009).

Does benefit due to antihypertensive therapy differ in different age groups? There are various claims made in the literature regarding the benefits of antihypertensive therapy in different age groups. One meta‐analysis of 31 trials with 190,606 participants by the Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration concluded that reduction of BP produces benefits in younger (aged less than 65 years) and older (aged greater than 65 years) adults, with no strong evidence that protection against major vascular events afforded by different drug classes varies substantially with age (BPLTTC 2008). In contrast, the results from the Prospective Studies Collaboration meta‐analysis by analyzing individual data of one million adults from 61 prospective observational studies of BP and mortality showed that at ages 40 to 69 years, each difference of 20 mmHg usual SBP (approximately 10 mmHg usual DBP) was associated with more than a two‐fold difference in the stroke death rate, and with two‐fold differences in the death rates from ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and other vascular causes. The annual absolute estimated differences in risk are greater in old age (Prospective Studies Collaboration 2002).

Although reduction in BP is believed to result in reduction in clinically important outcomes such as stroke or MIs, it a poor surrogate outcome measure for all‐cause mortality and morbidity. Similar or greater reduction in BP by different classes of antihypertensive drugs may not necessarily result in similar or greater magnitude of reduction in clinically relevant outcomes (Wright 2009).

Description of the intervention

High BP should be managed first by changing life style (eating a healthy diet with less salt, exercising regularly, quitting smoking and maintaining a healthy weight). When these lifestyle changes are not sufficient, treatment with antihypertensive drugs is recommended. Several different classes of medications are available to reduce BP (thiazide diuretics, beta‐blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), calcium channel blockers and alpha‐blockers) (NICE 2016).

How the intervention might work

Different classes of antihypertensive drugs have different mechanisms of action. The mechanism of action by which thiazide diuretics lower BP in the long term is not fully understood. After chronic use, thiazides lower peripheral resistance. The mechanism of these effects is uncertain as it may involve effects on 'whole body,' renal autoregulation or direct vasodilator actions (Hughes 2004; Longo 2012). Thiazides act on the kidney to inhibit reabsorption of sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl‐) ions from the distal convoluted tubules in the kidneys by blocking the thiazide‐sensitive Na+‐Cl‐ symporter (Duarte 2010). They also increase calcium reabsorption at the distal tubule and increase the reabsorption of calcium ions (Ca2+) by a mechanism involving the reabsorption of sodium and calcium in the proximal tubule in response to sodium depletion.

Alpha‐blockers (α1 adrenergic receptor blockers) inhibit the binding of norepinephrine (noradrenaline) to the α1 receptors causing vasodilation.

Beta‐blockers are competitive antagonists that block the receptor sites for epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine on adrenergic beta‐receptors. Some block activation of all types of beta‐adrenergic receptors (β1, β2 and β3) and others are selective for one of the three types of beta receptors (Frishman 2005).

Calcium channel blockers reduce BP through various mechanisms: by vasodilation, reduction in the force of contraction of the heart, by slowing the heart beat and by directly reducing aldosterone production.

ACE inhibitors block the conversion of angiotensin I (AI) to angiotensin II (AII). They thereby lower arteriolar resistance and increase venous capacity. They decrease cardiac output, cardiac index, stroke work and volume, and lower resistance in blood vessels in the kidneys. As a result of negative feedback of conversion of AI to AII, renin and AI increase in concentration in the blood. Bradykinin increases because of less inactivation by ACE.

ARBs block the activation of angiotensin II AT1 receptors. Blockage of AT1 receptors directly causes vasodilation, reduces secretion of vasopressin, and reduces production and secretion of aldosterone.

Why it is important to do this review

Clinical trials in adults with mild to moderate hypertension have included people over a wide age range from 18 to 104 years of age. There are two Cochrane Reviews evaluating the effectiveness of antihypertensive drug therapy in people with primary hypertension compared to placebo or no treatment: "First line drugs for hypertension" in adults aged 18 years or older (Wright 2009) and an updated review "Pharmacotherapy of hypertension in the elderly" (aged 60 years or older) with a subgroup meta‐analysis in very elderly people (aged 80 years or older) (Musini 2009).

Wright 2009 found that despite a similar magnitude of reduction in BP, a surrogate outcome measure, the clinical effectiveness in terms of all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality and morbidity was different for different drug classes. First‐line low‐dose thiazides reduced all morbidity and mortality outcomes. First‐line ACE inhibitors and calcium channel blockers may have been similarly effective but the evidence was less robust. First‐line high‐dose thiazides and first‐line beta‐blockers were inferior for some outcomes to first‐line low‐dose thiazides. However, the review did not provide data on clinical effectiveness of antihypertensive drug therapy in different age groups.

Musini 2009 concluded that all‐cause mortality as well as cardiovascular mortality and morbidity were modestly reduced in elderly people (aged 60 years or older). However, the decrease in all‐cause mortality was limited to people 60 to 79 years of age.

Therefore, it is important to know the relative and absolute magnitude of the effect of antihypertensive drugs in different age groups of people with primary hypertension. This systematic review aimed to find the relative and absolute magnitude of the reduction in all‐cause mortality as well as cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in adults aged 18 to 59 years with primary hypertension (mild to moderate systolic or diastolic hypertension).

Objectives

To quantify antihypertensive drug effects on all‐cause mortality in adults aged 18 to 59 years with mild to moderate primary hypertension. To quantify effects on cardiovascular mortality plus morbidity (including cerebrovascular and coronary heart disease mortality plus morbidity), withdrawal due adverse events and estimate magnitude of systolic and diastolic blood pressure lowering at one year.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCT) of at least one year' duration. Trials must have included a control group that either received a placebo or received no antihypertensive therapy.

We excluded trials using non‐randomized allocation methods such as alternate allocation, week of presentation or retrospective controls. Trials that compared two specific antihypertensive first‐line therapies without a placebo or untreated control were also excluded.

Types of participants

Trials included only people aged 18 to 59 years or separately report outcomes for people in this age group. To maximize data inclusion, if trials included at least 90% of participants in the specified age group (18 to 59 years) but did not report outcomes data separately for this specific age group, we included the overall data in all randomized participants provided in these trials.

Participants must have had primary hypertension with a SBP of at least 140 mmHg or a DBP of at least 90 mmHg, or both at baseline.

Types of interventions

Acceptable antihypertensive drug therapies included: diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta‐blockers, combined alpha‐ and beta‐blockers, calcium‐channel blockers, alpha‐blockers, central sympatholytics, direct vasodilators or peripheral adrenergic antagonists. Drugs could have been administered alone or in combination, and in fixed or stepped care regimens. The control group must have received a placebo or no anti‐hypertensive therapy.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality (death from all causes).

Secondary outcomes

Cardiovascular mortality plus morbidity (included fatal and non‐fatal stroke, fatal and non‐fatal MI, sudden death, hospitalization or death from congestive heart failure and other significant vascular deaths such as ruptured aneurysms). It did not include angina, transient ischaemic attacks, surgical or other procedures, or accelerated hypertension.

Cerebrovascular mortality plus morbidity including fatal and non‐fatal stroke.

Coronary heart disease mortality plus morbidity including fatal and non‐fatal MI, and sudden or rapid cardiac death.

Withdrawal due to adverse events.

Decrease in SBP and DBP.

When the primary trial did not report on outcomes that fitted the above definitions, decisions were made based on maximizing the inclusion of the data as defined in each included study and maintaining concordance with how the data were classified in previous reviews (Musini 2009; Wright 2009).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Hypertension Information Specialist (DS) conducted systematic searches in the following databases for RCTs without language, publication year or publication status restrictions:

the Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS‐Web) (searched 23 January 2017);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS‐Web) (searched 23 January 2017);

MEDLINE Ovid (from 1946 onwards), MEDLINE Ovid Epub Ahead of Print and MEDLINE Ovid In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (searched 23 January 2017);

Embase Ovid (searched 23 January 2017);

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) (searched 23 January 2017);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/trialsearch) (searched 23 January 2017).

The search strategy used in this review was identical to the Cochrane Review on "First line drugs for hypertension" (Wright 2009) and "Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in elderly patients" (Musini 2009). The Cochrane Hypertension Information Specialist (DS) modelled subject strategies for databases on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE. Where appropriate, they were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying randomized controlled (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Box 6.4.b; Higgins 2011a). Search strategies for major databases are provided in Appendix 1. Search was not done for regulatory documents from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or European Medicine Agency (EMA).

There were no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We carefully checked the bibliographies of previously published meta‐analyses on the treatment of hypertension to help identify references to trials (Collins 1990; Thijs 1992; MacMahon 1993; Insua 1994; Mulrow 1994; Pearce 1995; Gueyffier 1996; Psaty 1997; Mulrow 1998; Gueyffier 1999; Quan 1999; Nikolaus 2000; Psaty 2003; Turnbull 2003; Kang 2004; BBLTTC 2005; BPLTTC 2008; Law 2009; Musini 2009; Wright 2009; Thomopoulos 2014; Sundström 2015; Zanchetti 2015; Parsons 2016; Tan 2016; Thomopoulos 2016; Kızılırmak 2017; Wiysonge 2017).

We contacted experts in the field to identify any other trials missed in our search. We checked reference lists of included studies and contacted relevant trialists for information about unpublished or ongoing studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (VM or LP or DS) screened the titles and abstracts of citations from the search. Articles were rejected on initial screen if they were not reports of an RCT or there was no possibility that the trial could fit the requirements of this review. Of the articles selected for further review, at least two review authors (VM, LP or JMW) independently assessed whether they met the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (VM and JMW) independently performed data abstraction, cross‐checked and compared whenever possible to data from previously published meta‐analyses. The data abstraction form included details of study design, randomization, blinding, duration of treatment, baseline characteristics, number of participants lost to follow‐up, outcomes, intervention, statistical analysis and reporting. Trial characteristics are detailed in the Characteristics of included studies table. One review author (FG) provided data in the 18‐ to 59‐year‐old subgroup from the INDANA (Gueyffier 1995) database for the MRC‐TMH 1985 trial.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (VM and JMW) independently assessed risk of bias of each included trial and resolved any disagreements by adjudication or discussion with a third review author (AT or LP or FG). Risk of bias assessment was done according to Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). We assessed seven domains: randomization and allocation concealment to assess selection bias; blinding of the participants and physicians to assess performance bias; blinding of outcome assessor to assess detection bias; incomplete outcome reporting to assess attrition bias; selective reporting of outcomes to assess selective reporting bias and other bias to assess whether the study was funded by a drug manufacturer (in which case it was assessed as high risk of bias).

'Summary of findings' table

We used GRADEpro software to present the 'Summary of findings' table (GRADEpro). We decided to include all clinically relevant primary and secondary outcomes such as all‐cause mortality, total cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity, coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity, withdrawal due to adverse events and magnitude of reduction in SBP and DBP.

The five factors considered in grading overall quality of evidence were: limitations in study design and implementation, indirectness of evidence, unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results, imprecision in results and high probability of publication bias. This approach specifies four levels of quality: high, moderate, low and very low quality evidence. The highest quality rating is for randomized trial evidence. Quality rating is downgraded by one level for each factor, up to a maximum of three levels for all factors. If there are severe problems for any one factor (when assessing limitations in study design and implementation, in concealment of allocation, loss of blinding or attrition over 50% of participants during follow‐up), randomized trial evidence may fall by two levels due to that factor alone.

Measures of treatment effect

We used Review Manager 5 for data synthesis and analyses (RevMan 2014). Quantitative analyses of outcomes were based on intention‐to‐treat results. We used risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) to combine outcomes across trials. If there was a significant difference in any outcome measure, we presented an absolute risk reduction (ARR) and number needed to treat for an additional beneficial (NNTB) or harmful (NNTH) outcome in the 'Summary of findings' table. For continuous outcomes (SBP and DBP), we calculated the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI to combine outcomes across studies.

Unit of analysis issues

For all outcomes measures reported, we used data from each trial at the end of the follow‐up period mentioned in each trial, which varied from two to 10 years.

Dealing with missing data

When participants were lost to follow‐up, we used data as reported for participants who were followed until end of the study in the analyses. Refer to how data was accounted for and included in each study under assessment of attrition bias in the Risk of bias in included studies section.

For example, in the MRC‐TMH 1985 study, events such as non‐fatal stroke or MI terminated participation in the study and follow‐up of such participants to the end of the study was not done. In such instances, data available up to the time point during which participants were followed were included in the analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested heterogeneity of treatment effect between the trials using a standard Chi² statistic for heterogeneity. We used the fixed‐effect model to obtain summary statistics of pooled trials, unless there was significant between‐study heterogeneity, in which case we used the random‐effects model to test statistical significance. When heterogeneity was estimated to be significant (I² greater than 50%), we explored the factors contributing to heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess publication bias if at least 10 studies met the inclusion criteria using a funnel plot. However, in this review, only seven studies met the inclusion criteria and provided data for quantitative analyses, so funnel plot analyses were not performed.

Data synthesis

We used Review Manager 5 to perform data synthesis and analyses (RevMan 2014). We presented dichotomous outcomes as RR with 95% CI using a fixed‐effect model and continuous outcomes (SBP and DBP) as MD with 95% CI.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Since most participants included in this review were subgroups of participants from four of the seven trials in adults aged 18 years or older, further dividing participants into various other subgroup and analysing outcomes would lead to an increase in alpha error. Multiple comparisons within further subgroups would increase the chances of finding significant differences and therefore was not done.

When heterogeneity was significant (I² greater than 50%), we attempted to identify trials that would contribute to heterogeneity and explore their population characteristics, baseline BP, blinded or open‐label study design, use of antihypertensive drugs as fixed dose or stepped up therapy or response to placebo that would possibly explain the reason for heterogeneity. As the decrease in SBP and DBP showed significant heterogeneity, we presented results as MD with 95% CI using a random‐effects model instead of a fixed‐effect model.

Sensitivity analysis

To test for robustness of results, we conducted the following sensitivity analyses:

placebo controlled trials versus untreated trials;

double blind trials versus open‐label or single‐blind trials;

trials using combined starting drugs as stepped up therapy versus fixed‐dose therapy.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Since the search strategy used in this review was identical to the Cochrane Review "First line drugs for hypertension" (Wright 2009) and "Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in elderly patients" (Musini 2009), we included search findings to 2008 from these reviews. The PRISMA diagram for search to 2008 is not shown.

The Wright 2009 review search from 1946 to 2008 resulted the identification of 6232 citations. Of these, 5985 articles were rejected on initial screen as they were not reports of an RCT or there was no possibility that the trial could fit the requirements of this review. A total of 247 citations were retrieved for detailed evaluation by two review authors (JMW and VM) of which 13 were review articles. Of the remaining 234 citations, 59 were excluded upon detailed reading as they did not meet minimum inclusion criteria. A total of 175 reports of 57 potentially first‐line trials were evaluated. Forty‐eight reports of 33 trials were excluded and were listed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table in the Wright 2009 review. Finally, 127 reports of 24 trials were included in the Wright 2009 review. Not all trials included in the Wright 2009 review pertained to the age group 18 to 59 years old therefore we excluded 17 of the 24 studies included in the Wright 2009 review. These are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

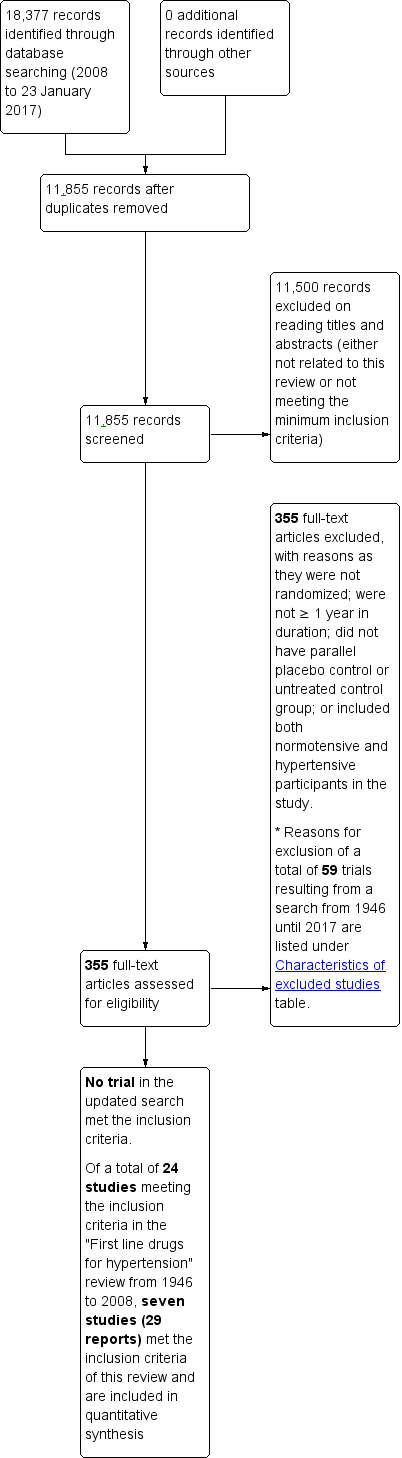

The search strategy from 2008 to January 2017 resulted in 11,855 citations after removing duplicates. We screened the titles and abstracts and excluded 11,500 citations. Articles were rejected on this initial screen if the article was not a report of a RCT or there was no possibility that the trial could fit the requirements of this review. At leat two review authors (LP, VM or JMW) assessed the remaining articles to determine if they met the inclusion criteria. Three hundred and fifty‐five full‐text articles were retrieved of which all 355 articles were excluded on detailed reading as they did not meet the minimum inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

1.

This is a partial study flow diagram and shows search findings from 2008 until 2017. The search done from 1946 to 2008 was identical to the "First line drugs for hypertension" review in which 24 trials met the inclusion criteria of which 17 had to be excluded and only seven studies provided data for quantitative synthesis in 18‐ to 59‐year‐old participants.

A total of seven studies (in 27 reports) identified previously in the "First line drugs for hypertension" review (Wright 2009) met the inclusion criteria and provide information in 18‐ to 59‐year‐old participants and were therefore included in the quantitative analyses.

Please note that 59 trials including 17 trials from the "First line drugs for hypertension" review (Wright 2009) resulting from literature search from 1946 until 2017 were excluded and reasons for exclusion were listed under the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Included studies

Seven trials met the inclusion criteria (Carter 1970; VA‐II 1970; HSCSG 1974; USPHSHCSG 1977; VA‐NHLBI 1977; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986).

This review included 17,327 (88%) participants aged 18 to 59 years from a total of 19,684 randomized participants from the seven included studies in adults with hypertension. In the MRC‐TMH 1985 trial, we were able to include only the people aged 18 to 59 years. The MRC‐TMH study contributed 14,541 (84%) of the total randomized participants with a mean age of 50 years and mean baseline BP of 160/98 mmHg and a mean duration of follow‐up of five years. Treatment used in this study was bendrofluazide 10 mg daily or propranolol 80 mg to 240 mg daily and with methyldopa added if required.

Refer to the Characteristics of included studies table and Table 2 for details regarding baseline characteristics for all included participants. No data regarding baseline characteristics was available for the specific 18‐ to 59‐year‐old subgroup of participants in four trials (Carter 1970; VA‐II 1970; HSCSG 1974; MRC‐TMH 1985). Three trials included only 18‐ to 59‐year‐old participants (USPHSHCSG 1977; VA‐NHLBI 1977; Oslo 1986). VA‐II 1970 did not provide the age range of included participants. The mean age of participants included in these four trials was 41.3 years.

1. Baseline characteristics of included studies in all randomized participants aged 18 years or older.

|

Study Study design |

Number of 18‐ to 59‐year‐old participants/total randomized participants (%) Characteristics of all randomized participants in each study |

Mean baseline SBP/DBP (mmHg) |

Mean age (range) | Control group | Treatment used | Outcomes reported in 18‐ to 59‐year‐old participants |

|

Carter 1970 Open label |

49/97 (50.5%); included all hypertensive survivors aged < 80 years of ischaemic type major strokes admitted to Ashford Hospital. Men: 57% |

165/101 | Not reported (40 to 79 years) |

Untreated | Stepped‐up therapy Bendrofluazide (93%), methyldopa and debrisoquine FU 4.0 years |

All‐cause mortality |

|

HSCSG 1974 Double blind |

252/452 (55.7%). 80% of participants had completed stroke in year before randomization; 16% completed stroke + TIA and 4% TIA only. Severe neurological disability in 9.9% of treated group and 5% of control group. Black: 80% Men: 60% |

167/100 77% of the drug treated and 74% of the placebo treated participants had SBP < 180 mmHg |

59 years (< 75 years) |

Placebo | Fixed‐dose therapy Deserpidine 1 mg + methyclothiazide 10 mg FU 3.0 years |

Cardiovascular mortality + morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality + morbidity CHD mortality + morbidity |

|

MRC‐TMH 1985 Single blind |

14,541/17,354 (83.8%). Men: 52%. Primary prevention participants. Refer to exclusion criteria listed in Characteristics of included studies table. |

161/98. | 52 years (35‐64 years) |

Placebo 288/12,375 (0.02%) participants randomly assigned to observation taking no tablets and merged with placebo |

Stepped‐up therapy Bendrofluazide 10 mg daily (71% monotherapy), propranolol 80‐240 mg daily (78% monotherapy), methyldopa added if required FU 4.9 years |

All‐cause mortality Cardiovascular mortality + morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality + morbidity CHD mortality + morbidity SBP DBP |

|

Oslo 1986 Open label |

785/785 (100%) Men: 100% Primary prevention participants. Refer to exclusion criteria listed in Characteristics of included studies table |

156/97 | 45 years (40‐49 years) |

Untreated | Stepped‐up therapy Hydrochlorothiazide (95%), methyldopa and propranolol (26%). At 5‐year follow‐up, 36.7% were on hydrochlorothiazide alone, 26% were on hydrochlorothiazide + propranolol, 20% were on hydrochlorothiazide + methyldopa and 18% participants were on other drugs. FU 5.5 years |

All‐cause mortality Cardiovascular mortality + morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality + morbidity CHD mortality + morbidity SBP DBP |

|

USPHSHCSG 1977 Double blind |

389/389 (100%) Men: 80% Primary prevention participants. Refer to exclusion criteria listed in Characteristics of included studies table |

147/99 | 44 years (21‐55 years) |

Placebo | Fixed‐dose therapy Chlorothiazide 500 mg twice daily + Rauwolfia serpentina 100 mg twice daily FU 7.0 years |

All‐cause mortality Cardiovascular mortality + morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality + morbidity CHD mortality + morbidity SBP DBP |

|

VA‐II 1970 Double blind |

299/380 (78.7%) Men: 100% Primary prevention participants. Refer to exclusion criteria listed in Characteristics of included studies table |

176/103 | 51 years (range not reported) |

Placebo | Stepped‐up therapy First line: hydrochlorothiazide 100 mg + reserpine 0.2 mg Second line: hydralazine 75‐150 mg FU 3.3 years |

Cardiovascular mortality + morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality + morbidity CHD mortality + morbidity |

|

VA‐NHLBI 1977 Double blind |

1012/1012 (100%) Men: 100% Primary prevention participants. Refer to exclusion criteria listed in Characteristics of included studies table |

SBP not reported/93 | 38 years (range 21‐50 years) |

Placebo | Stepped‐up therapy Chlorthalidone 50 mg, 100 mg (53% chlorthalidone alone) Reserpine 0.25 mg FU 1.5 years |

All‐cause mortality Cardiovascular mortality + morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality + morbidity CHD mortality + morbidity DBP |

| Total of 7 studies published from 1970 to 1986 | 17,327/19,684 (88% of total randomized participants in the 7 studies were 18‐59 years of age) of which only 301/1,7327 (0.02%) participants were secondary prevention | SBP 147‐176/DBP 99‐103 mmHg | Mean age 37.5‐45 years | 5 RCTs were placebo controlled and 2 RCTS had untreated group as control |

Mostly high‐dose thiazide and beta‐blockers Mean follow‐up 1.5‐7 years. |

5/7 RCTs report on all clinically important outcomes |

CHD: coronary heart disease; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; FU: follow‐up; SBP: systolic blood pressure; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

All seven trials used first‐line high‐dose thiazide drugs for lowering BP. Two trials evaluated beta‐blockers versus placebo (MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986). Three of the seven trials used methyldopa (Carter 1970; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986). Two trials used reserpine (VA‐II 1970; VA‐NHLBI 1977). Five trials used a stepped approach to antihypertensive drug administration (Carter 1970; VA‐II 1970; VA‐NHLBI 1977; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986). The remaining two trials used a standard fixed dose of drug in the intervention arm.

Two trials included only men (Oslo 1986; VA‐II 1970; Oslo 1986). Three trials did not report ethnicity (Carter 1970; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986). The four remaining trials reported ethnicity for all included participants. African‐Americans comprised the following percentages in these trials: HSCSG 1974 80%; VA‐II 1970 42%; VA‐NHLBI 1977 25%; and USPHSHCSG 1977 28%. Three trials based entry on DBP (VA‐II 1970; USPHSHCSG 1977; VA‐NHLBI 1977). Four trials based entry on either SBP or DBP (Carter 1970; HSCSG 1974; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986).

Definition of stroke differed across trials. In more recent trials, it was defined as the presence of neurological deficit lasting more than 24 hours. Older trials (such as HSCSG 1974) defined stroke as a neurological deficit lasting more than 24 hours or a marked increase in transient ischaemic attacks (twice the weekly prerandomization level of occurrence, more than four per week or deterioration of more than 8 points in neurological score). VA‐NHLBI 1977 defined stroke as typical weakness or paralysis. Some trials did not define stroke. In our opinion combining all strokes (including reversible ischaemic neurological deficit (RIND)), into one outcome is not optimal. More clinically relevant interpretations could be made if strokes were subdivided into three groups: strokes with no disability, strokes with mild disability and strokes with severe disability. The definition of MI and sudden death was consistent across most trials. MI was defined as typical chest pain with ECG changes or increased cardiac enzymes; sudden death was defined as death within 24 hours of first evidence of acute CVD or unrelated to other known pre‐existing diseases.

It was possible in most trials to determine which participants were treated for primary or secondary prevention. All trials excluded people with angina and congestive heart failure, as these conditions would require use of antihypertensive drugs for reasons independent of their antihypertensive action. Some trials allowed people with prior MI or stroke if they were not recent (e.g. within the previous three months). Thus, by determining the baseline prevalence of stroke and MI it was possible to calculate the percentage that represented secondary prevention. In six trials, the study population consisted of predominantly ambulatory participants recruited from the community, primary care centres or hospital‐based clinics (VA‐II 1970; HSCSG 1974; USPHSHCSG 1977; VA‐NHLBI 1977; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986). Two trials were secondary prevention and included stroke survivors who were ambulatory and contributed 301 (0.02%) of total randomized participants(Carter 1970; HSCSG 1974). One trial did not report prevalence of stroke or MI (VA‐II 1970). Three trials were 100% primary prevention (USPHSHCSG 1977; VA‐NHLBI 1977; Oslo 1986).

One trial reported baseline prevalence of diabetes as 0% (USPHSHCSG 1977). Three trials reported baseline prevalence of smoking (USPHSHCSG 1977 46.7%; MRC‐TMH 1985 29.7%; Oslo 1986 41.7%;).

Mean baseline BP for all the trials ranged from 147 mmHg to 176 mmHg for SBP and from 99 mmHg to 103 mmHg for DBP. One trial did not report baseline SBP level (VA‐NHLBI 1977). For complete description of the BP inclusion criteria for each study see the Characteristics of included studies table. One trial that contributed the most weight to effect size in this review included mostly people receiving primary prevention followed up for a mean duration of five years with mean baseline BP of 160/98 mmHg (MRC‐TMH 1985). The mean duration of follow‐up across the seven included studies ranged from two to 10 years.

Excluded studies

Fifty‐nine trials resulting from the search from 1946 to 2017 were excluded from this review and reasons for exclusion are provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Twenty‐four trials met the inclusion criteria in the "First line drugs for hypertension" review by Wright 2009 and "Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in the elderly review" by Musini 2009, but 17 were excluded from this review. The reasons for excluding them were mostly because they did not report outcomes separately for the 18 to 59 years age group or were conducted in people 60 years or older.

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias for each included study using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool for RCTs as described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). Potential parameters of methodological quality listed in the 'Risk of bias' table include: method used to randomize participants, whether randomization was completed in an appropriate and blinded manner; whether participants, providers, outcome assessors, or a combination of these were blinded to assigned therapy; whether the control group received a placebo or no treatment; percent of participants who did not complete follow‐up (dropouts); percent of participants not on assigned active or placebo therapy at study completion; selective reporting of outcomes and other bias in terms of funding of the trial by the manufacturer.

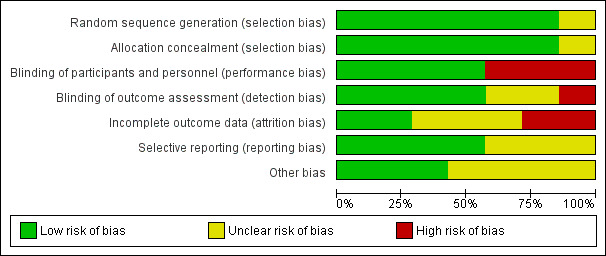

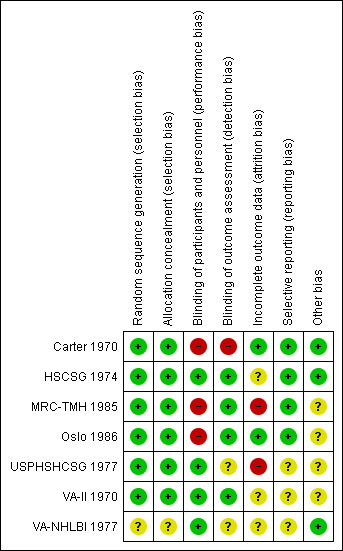

Refer to Figure 2 for the 'Risk of bias' graph which provides review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. Refer to Figure 3 for the 'Risk of bias' summary which provides review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Randomization was at low risk of bias in six trials (Carter 1970; VA‐II 1970; HSCSG 1974; USPHSHCSG 1977; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986). It was judged as unclear in VA‐NHLBI 1977.

Allocation concealment was at low risk of bias in six trials (Carter 1970; VA‐II 1970; HSCSG 1974; USPHSHCSG 1977; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986), and unclear in VA‐NHLBI 1977.

Blinding

Blinding of participant and personnel was at low risk of bias in four trials (VA‐II 1970; HSCSG 1974; USPHSHCSG 1977; VA‐NHLBI 1977). It was at high risk of bias in three trials; two as treating physicians were aware of the treatment being prescribed (Carter 1970; MRC‐TMH 1985), and one as both participants and treating physicians were aware of the treatment being prescribed (Oslo 1986).

Blinding of outcome assessors was at low risk of bias in four trials (VA‐II 1970; HSCSG 1974; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986). It was at unclear risk of bias in two trials (USPHSHCSG 1977; VA‐NHLBI 1977), and at high risk of bias in one trial as study did not mention blinding of physician or outcome assessor (Carter 1970).

Incomplete outcome data

Incomplete outcome data was at low risk of bias in two trials (Carter 1970; Oslo 1986), at unclear risk of bias in three trials (VA‐II 1970; HSCSG 1974; VA‐NHLBI 1977), and at high risk of bias in two trials (USPHSHCSG 1977; MRC‐TMH 1985). In the MRC‐TMH 1985 trial, participant participation was terminated in the event of non‐fatal stroke or MI. In the USPHSHCSG 1977 trial, attrition rate was high due to dropouts or occurrence of morbid events. Vital statistics information was unknown in 26 participants who dropped out.

Selective reporting

Selective reporting was at low risk of bias in four trials (Carter 1970; HSCSG 1974; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986), and at unclear risk of bias in three trials (VA‐II 1970; USPHSHCSG 1977; VA‐NHLBI 1977).

Other potential sources of bias

Other potential bias in terms of funding by the manufacturer was at low risk of bias in three trials (Carter 1970; HSCSG 1974; VA‐NHLBI 1977), and at unclear risk of bias in four trials (VA‐II 1970; USPHSHCSG 1977; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See Table 1.

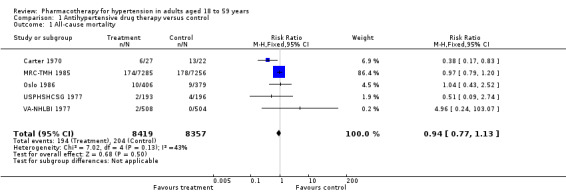

All‐cause mortality

Antihypertensive drug therapy as compared to placebo or untreated control had no effect on all‐cause mortality (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.13; participants = 16,776; studies = 5; I² = 43% Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy versus control, Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality.

Data from two studies (VA‐II 1970; HSCSG 1974) were not provided in the original Mulrow 1998 review for the 18‐ to 59‐year‐old subgroup. These two studies contributed 551 (3.2%) of total randomized participants included.

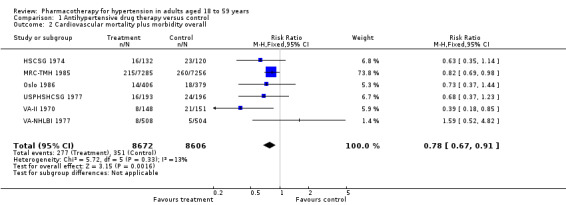

Cardiovascular mortality plus morbidity

Antihypertensive drug therapy as compared to placebo or untreated control reduced cardiovascular mortality plus morbidity (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.91; participants = 17,278; studies = 6; I² = 13%; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy versus control, Outcome 2 Cardiovascular mortality plus morbidity overall.

The original Mulrow 1998 review and the Carter 1970 study did not provide total cardiovascular mortality plus morbidity data in 29 (0.2%) of total randomized participants.

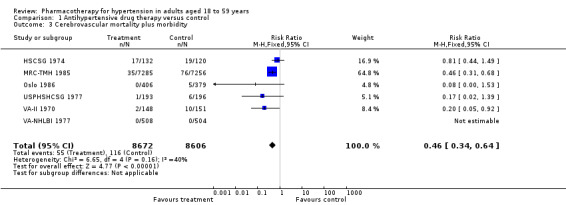

Cerebrovascular mortality plus morbidity

Antihypertensive drug therapy as compared to placebo or untreated control reduced stroke (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.64; participants = 17,278; studies = 6; I² = 40%; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy versus control, Outcome 3 Cerebrovascular mortality plus morbidity.

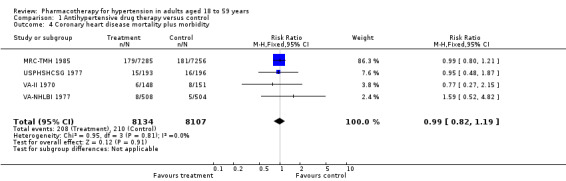

Coronary heart disease mortality plus morbidity

Antihypertensive drug therapy as compared to placebo or untreated control did not reduce coronary heart disease (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.19; participants = 16,241; studies = 4; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy versus control, Outcome 4 Coronary heart disease mortality plus morbidity.

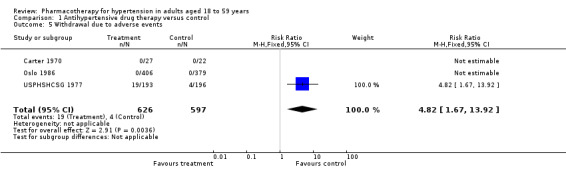

Withdrawal due to adverse events

Data for withdrawal due to adverse events in the 18‐ to 59‐year‐old subgroup were not available in four trials (VA‐II 1970; HSCSG 1974; VA‐NHLBI 1977; MRC‐TMH 1985). Three trials report this outcome (Carter 1970; USPHSHCSG 1977; Oslo 1986). However, two trials reported no adverse events in either the treatment and the control groups (Carter 1970; Oslo 1986). The RR was based on one study (RR 4.82, 95% CI 1.67 to 13.92; participants = 1223; study = 1; Analysis 1.5) (USPHSHCSG 1977).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy versus control, Outcome 5 Withdrawal due to adverse events.

Withdrawal due to adverse events was not available in the 18‐ to 59‐year‐old subgroup in one trial (MRC‐TMH 1985).

Decrease in systolic and diastolic blood pressure

Four trials reported data for DBP in 18‐ to 59‐year‐old subgroup of participants at end of 1 year (USPHSHCSG 1977; VA‐NHLBI 1977; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986), and three studies reported data for SBP (USPHSHCSG 1977; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986). Therefore, we added this outcome to the list of secondary outcomes in the review.

Antihypertensive drug therapy significantly lowered both SBP and DBP as compared to the control group. Since heterogeneity was significant for BP data results were presented using a random‐effects model (SBP: MD ‐14.98, 95% CI ‐20.44 to ‐9.52; participants = 14,845; studies = 3; I² = 95%; Analysis 1.6; DBP: MD ‐7.62, 95% CI ‐10.55 to ‐4.69; participants = 15,857; studies = 4; I² = 96%; Analysis 1.7).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy versus control, Outcome 6 Decrease in systolic blood pressure.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy versus control, Outcome 7 Decrease in diastolic blood pressure.

Sensitivity analysis

In a sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the overall treatment effect size, we deselected trials based on placebo controlled versus untreated group; double‐blind versus open‐label or single‐blind trials; trials using combined starting drugs as stepped up therapy versus fixed dose therapy; and secondary prevention versus mostly primary prevention. In all these instances, there were no clinically important changes in the treatment effect.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review summarizes the effects of antihypertensive drug therapy for elevated BP in adults aged 18 to 59 years. The pooled data showed that using antihypertensive drug therapy (mostly high‐dose thiazide diuretics) reduced cardiovascular mortality and morbidity primarily due to a reduction in cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity, but had no effect on all‐cause mortality or coronary heart disease. Withdrawals due to adverse events were increased with drug therapy. The mean decrease in SBP/DBP at end of 1 year was 15/8 mmHg.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The subgroup of people 18 to 59 years of age from the MRC‐TMH 1985 study represented 84% of total randomized participants and thus contributed the most to the treatment effect size for all mortality and morbidity outcomes. Therefore, the evidence from this review is most applicable to people who were eligible for this study. The mean age of participants was 50 years and the mean baseline BP was 160/98 mmHg. This means that about half of the participants would be in the mild hypertension range and half would be in the moderate hypertension range. Most of the participants (97.8%) were being treated for primary prevention. The mean duration of follow‐up was five years. Treatment used in this study was first‐line bendrofluazide 10 mg daily or first‐line propranolol 80 mg to 240 mg daily and methyldopa was added if required.

In this review, in five trials, about 40% of the participants did not achieve the DBP goal of less than 90 mmHg although three trials used stepped care therapy (VA‐II 1970; MRC‐TMH 1985; Oslo 1986), and two trials used fixed‐dose combination therapy (HSCSG 1974; USPHSHCSG 1977). This observation is important to note because it implies that in routine practice a substantial proportion of people with elevated BP are unlikely to be able to achieve BP targets. This does not mean these people will not benefit as BP reduction is only partly responsible for the risk reduction of antihypertensive treatment (Boissel 2005).

The data on withdrawals due to adverse events was incomplete as only three out of seven trials reported this outcome, with two trials (total participants = 834) reporting zero events in both arms. MRC‐TMH 1985 was not included in the withdrawals due to adverse events outcome as that outcome was not available separately for the 18‐ to 59‐year age group. However, withdrawals due to adverse events were increased by drug treatment in the full MRC‐TMH 1985 trial (RR 4.81, 95% CI 4.15 to 5.58; absolute risk increase 8.9%). This is very similar to the estimate from the present review (RR 4.82; absolute risk increase 3.8%), which primarily represents the results of the USPHSHCSG 1977 trial (participants = 389). Even though we have graded this outcome as very low quality evidence, it is likely a reasonably robust estimate.

The thiazide arm of the MRC‐TMH 1985 trial was classified as high‐dose thiazide in the "First line drugs for hypertension" review (Wright 2009). That review concluded that using low‐dose thiazide was beneficial in terms of reducing all‐cause mortality, total cardiovascular events, coronary heart disease and stroke. This benefit for coronary heart disease and all‐cause mortality was not observed in first‐line high‐dose thiazide trials. Thus, first‐line low‐dose thiazides are preferred, even though we do not have any evidence for low‐dose thiazides in the age group studied here.

We calculated the absolute risk reduction (ARR) and NNTB for clinical outcomes that were significantly reduced with antihypertensive therapy compared to placebo or untreated control groups. For cardiovascular mortality plus morbidity, the relative risk reduction was 22%, ARR was 0.9% and NNTB was 112. For cerebrovascular events (fatal and non‐fatal stroke) the relative risk reduction was 64%, ARR was 0.7%, and NNTB was 143. This means that approximately 112 people need to be treated for about five years to prevent one adverse cardiovascular event and most of this benefit comes from a reduction in stroke (cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity).

Sensitivity analyses did not show any clinically important changes in the treatment effect.

MRC‐TMH 1985 also contributed more than 90% of the weight to the estimate of BP reduction in this review. Therefore, the mean BP reduction found in this review was close to that seen in the MRC‐TMH 1985 trial. The BP lowering effect was greater in the other trials, which resulted in high heterogeneity. This is likely because the design and number of drugs used in the trials differed.

Quality of the evidence

The overall quality of the evidence was graded using online GRADEpro software (GRADEpro). The 'Summary of findings' table provided the grading of the quality of evidence for each clinically important outcome. All‐cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality plus morbidity, cerebrovascular mortality plus morbidity and coronary heart disease mortality plus morbidity were downgraded to low quality evidence because of high risk of performance and attrition bias as well as lack of reporting of data from several trials that had to be excluded (Table 1). Low quality evidence means our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Withdrawal due to adverse events was downgraded to very low quality evidence as it was only reported in three of the seven trials meeting the inclusion criteria. Very low quality evidence means we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Since one study with high risk of performance and attrition bias provided most of the data to the estimated effect size, it is likely to be an overestimate of the true effect (MRC‐TMH 1985).

Potential biases in the review process

Reporting bias is possible as eight studies ( met the inclusion criteria but did not report data in the 18‐ to 59‐year‐old subgroup of participants separately and thus were excluded from this review (HOPE HYP 2000; TEST 1995; UKPDS 1998; VA‐I 1962; Wolff 1966; Anon 1973; ATTMH 1984; PATS 1995). Availability of data for all clinically relevant outcomes from all randomized studies meeting the inclusion criteria in this age group is needed.

Three trials combined a reserpine derivative with thiazide as first‐line drug therapy (VA‐II 1970; HSCSG 1974; USPHSHCSG 1977). The MRC‐TMH 1985 trial, which contributed the most weight in this review, added methyldopa if needed to first‐line high‐dose thiazide or beta‐blocker therapy. Therefore, results of this review are mostly applicable to those treatment approaches.

Since all seven included studies used high‐dose thiazides, at present we do not have evidence for low‐dose antihypertensive drug therapy as compared to placebo or untreated control in adults aged 18‐ to 59‐years with primary hypertension. Given the findings and conclusions of the first‐line drug review regarding all‐cause mortality and morbidity benefits of using low‐dose thiazide (Wright 2009), we recommend future RCTs compare first‐line low‐dose thiazide with other first‐line classes of antihypertensive drugs in young adults aged 18 to 59 years.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This is the first systematic review of drug therapy in adults aged 18 to 59 years with elevated BP. The ARR in adults aged 18‐ to 59‐years in this review for cardiovascular mortality and morbidity was small (0.9%) with an NNTB of 112 over five years. It is important for clinicians and participants to know the approximate magnitude of benefit in this setting. For people aged 60‐ to 79‐years the absolute reductions over five years were greater, total cardiovascular events, ARR 3.8% with an NNTB 26 over five years (Musini 2009).

Several guidelines to treat people with hypertension have been published. The eighth revision of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC) mainly based their recommendations on evidence from RCTs. However, five out of 10 recommendations are based on expert opinion (James 2014).

They recommended the following:

thiazide‐type diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs and calcium channel blockers as the initial therapy of choice. Although all these drug classes have comparable outcome benefits they concluded that thiazide‐type diuretics are superior to the other three classes in terms of heart failure;

specific recommendation in people aged less than 60 years, treatment goal is SBP less than 140 mmHg (expert opinion ‐ grade E evidence);

in the general population aged less than 60 years, the target should be DBP less than 90 mmHg and treatment should be initiated above this value (for ages 30 to 59 years, strong recommendation grade A; for ages 18 to 29 years, expert opinion ‐ grade E);

in the general population excluding black people (including people with diabetes), initial antihypertensive treatment should include a thiazide‐type diuretic, calcium channel blocker, ACE inhibitor or ARB (general population moderate recommendation ‐ grade B and for black people with diabetes weak recommendation ‐ grade C);

beta blockers are no longer considered as an initial therapy option.

The European Society of hypertension (ESH) 2013 guidelines recommend diuretics, beta‐blockers, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors and ARBs are included as viable options for initial hypertension therapy. Goal BP in people with diabetes mellitus is less than 140/85 mmHg. Recommendation for specific age group less than 60 years is SBP/DBP less than 140/90 mmHg (Mancia 2013).

The American Society of Hypertension/International Society of Hypertension (ASH/ISH) recommend ACE inhibitors or ARB as initial therapy in non‐black people under 60 years of age; a calcium channel blocker or thiazide diuretic is recommended for black people (Weber 2014).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Antihypertensive drugs used to treat predominantly healthy adults aged 18 to 59 years with mild to moderate primary hypertension have a small absolute effect to reduce cardiovascular mortality and morbidity (0.9% over a five‐year period) primarily due to reduction in cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity (0.7%). All‐cause mortality and coronary heart disease were not reduced. There is lack of good evidence on withdrawal due to adverse events.

Implications for research.

Long‐term randomized controlled trials of at least 10 years' duration are needed to investigate which first‐line drug is best in people in this age group as they will potentially be taking these drugs over a long duration. Future randomized controlled head to head studies should compare first‐line low‐dose thiazides versus other first‐line classes and measure all‐cause mortality, total serious adverse events and total cardiovascular serious adverse events. Long‐term high‐quality observational studies may also provide valuable additional information.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the editorial team of the Cochrane Hypertension Group. We would like to thank Stephen Adams for retrieving references.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy used in various databases

1 MEDLINE search strategy

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to Present with Daily Update Search Date: 23 January 2017 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp thiazides/ (15913) 2 exp sodium chloride symporter inhibitors/ (14603) 3 exp sodium potassium chloride symporter inhibitors/ (14205) 4 ((ceiling or loop) adj diuretic?).tw. (2564) 5 (amiloride or benzothiadiazine or bendroflumethiazide or bumetanide or chlorothiazide or cyclopenthiazide or furosemide or hydrochlorothiazide or hydroflumethiazide or methyclothiazide or metolazone or polythiazide or trichlormethiazide or veratide or thiazide?).tw. (34947) 6 (chlorthalidone or chlortalidone or phthalamudine or chlorphthalidolone or oxodoline or thalitone or hygroton or indapamide or metindamide).tw. (2353) 7 or/1‐6 [THZ] (50922) 8 exp angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors/ (44001) 9 angiotensin converting enzyme inhibit$.tw. (18514) 10 (ace adj2 inhibit$).tw. (18317) 11 acei.tw. (2857) 12 (alacepril or altiopril or ancovenin or benazepril or captopril or ceranapril or ceronapril or cilazapril or deacetylalacepril or delapril or derapril or enalapril or enalaprilat or epicaptopril or fasidotril or fosinopril or foroxymithine or gemopatrilat or idapril or imidapril or indolapril or libenzapril or lisinopril or moexipril or moveltipril or omapatrilat or pentopril$ or perindopril$ or pivopril or quinapril$ or ramipril$ or rentiapril or saralasin or s nitrosocaptopril or spirapril$ or temocapril$ or teprotide or trandolapril$ or utibapril$ or zabicipril$ or zofenopril$ or Aceon or Accupril or Altace or Capoten or Lotensin or Mavik or Monopril or Prinivil or Univas or Vasotec or Zestril).tw. (27811) 13 or/8‐12 [ACEI] (59794) 14 exp Angiotensin Receptor Antagonists/ (22055) 15 (angiotensin adj3 (receptor antagon$ or receptor block$)).tw. (11889) 16 arb?.tw. (5159) 17 (abitesartan or azilsartan or candesartan or elisartan or embusartan or eprosartan or forasartan or irbesartan or losartan or milfasartan or olmesartan or saprisartan or tasosartan or telmisartan or valsartan or zolasartan or Atacand or Avapro or Benicar or Cozaar or Diovan or Micardis or Teveten).tw. (15972) 18 or/14‐17 [ARB] (31152) 19 exp calcium channel blockers/ (83029) 20 (amlodipine or aranidipine or barnidipine or bencyclane or benidipine or bepridil or cilnidipine or cinnarizine or clentiazem or darodipine or diltiazem or efonidipine or elgodipine or etafenone or fantofarone or felodipine or fendiline or flunarizine or gallopamil or isradipine or lacidipine or lercanidipine or lidoflazine or lomerizine or manidipine or mibefradil or nicardipine or nifedipine or niguldipine or nilvadipine or nimodipine or nisoldipine or nitrendipine or perhexiline or prenylamine or semotiadil or terodiline or tiapamil or verapamil or Cardizem CD or Dilacor XR or Tiazac or Cardizem Calan or Isoptin or Calan SR or Isoptin SR Coer or Covera HS or Verelan PM).tw. (62158) 21 (calcium adj2 (antagonist? or block$ or inhibit$)).tw. (39065) 22 or/19‐21 [CCB] (111557) 23 (methyldopa or alphamethyldopa or amodopa or dopamet or dopegyt or dopegit or dopegite or emdopa or hyperpax or hyperpaxa or methylpropionic acid or dopergit or meldopa or methyldopate or medopa or medomet or sembrina or aldomet or aldometil or aldomin or hydopa or methyldihydroxyphenylalanine or methyl dopa or mulfasin or presinol or presolisin or sedometil or sembrina or taquinil or dihydroxyphenylalanine or methylphenylalanine or methylalanine or alpha methyl dopa).mp. (16154) 24 (reserpine or serpentina or rauwolfia or serpasil).mp. (20757) 25 (clonidine or adesipress or arkamin or caprysin or catapres$ or catasan or chlofazolin or chlophazolin or clinidine or clofelin$ or clofenil or clomidine or clondine or clonistada or clonnirit or clophelin$ or dichlorophenylaminoimidazoline or dixarit or duraclon or gemiton or haemiton or hemiton or imidazoline or isoglaucon or klofelin or klofenil or m‐5041t or normopresan or paracefan or st‐155 or st 155 or tesno timelets).mp. (19858) 26 exp hydralazine/ (4964) 27 (hydralazin$ or hydrallazin$ or hydralizine or hydrazinophtalazine or hydrazinophthalazine or hydrazinophtalizine or dralzine or hydralacin or hydrolazine or hypophthalin or hypoftalin or hydrazinophthalazine or idralazina or 1‐hydrazinophthalazine or apressin or nepresol or apressoline or apresoline or apresolin or alphapress or alazine or idralazina or lopress or plethorit or praeparat).tw. (4648) 28 or/23‐27 [CNS] (59745) 29 exp adrenergic beta‐antagonists/ (84772) 30 (acebutolol or adimolol or afurolol or alprenolol or amosulalol or arotinolol or atenolol or befunolol or betaxolol or bevantolol or bisoprolol or bopindolol or bornaprolol or brefonalol or bucindolol or bucumolol or bufetolol or bufuralol or bunitrolol or bunolol or bupranolol or butofilolol or butoxamine or carazolol or carteolol or carvedilol or celiprolol or cetamolol or chlortalidone cloranolol or cyanoiodopindolol or cyanopindolol or deacetylmetipranolol or diacetolol or dihydroalprenolol or dilevalol or epanolol or esmolol or exaprolol or falintolol or flestolol or flusoxolol or hydroxybenzylpinodolol or hydroxycarteolol or hydroxymetoprolol or indenolol or iodocyanopindolol or iodopindolol or iprocrolol or isoxaprolol or labetalol or landiolol or levobunolol or levomoprolol or medroxalol or mepindolol or methylthiopropranolol or metipranolol or metoprolol or moprolol or nadolol or oxprenolol or penbutolol or pindolol or nadolol or nebivolol or nifenalol or nipradilol or oxprenolol or pafenolol or pamatolol or penbutolol or pindolol or practolol or primidolol or prizidilol or procinolol or pronetalol or propranolol or proxodolol or ridazolol or salcardolol or soquinolol or sotalol or spirendolol or talinolol or tertatolol or tienoxolol or tilisolol or timolol or tolamolol or toliprolol or tribendilol or xibenolol).tw. (62363) 31 (beta adj2 (adrenergic? or antagonist? or block$ or receptor?)).tw. (101145) 32 or/29‐31 [BB] (159886) 33 exp adrenergic alpha antagonists/ (51279) 34 (alfuzosin or bunazosin or doxazosin or metazosin or neldazosin or prazosin or silodosin or tamsulosin or terazosin or tiodazosin or trimazosin).tw. (14099) 35 (adrenergic adj2 (alpha or antagonist?)).tw. (20625) 36 ((adrenergic or alpha or receptor?) adj2 block$).tw. (58854) 37 or/33‐36 [AB] (116499) 38 hypertension/ (236571) 39 hypertens$.tw. (375255) 40 ((high or elevat$ or rais$) adj2 blood pressure).tw. (26803) 41 or/38‐40 (441992) 42 randomized controlled trial.pt. (484850) 43 controlled clinical trial.pt. (97360) 44 randomized.ab. (371359) 45 placebo.ab. (182081) 46 clinical trials as topic/ (194591) 47 randomly.ab. (255305) 48 trial.ti. (167150) 49 or/42‐48 (1091343) 50 animals/ not (humans/ and animals/) (4782114) 51 Pregnancy/ or Hypertension, Pregnancy‐Induced/ or Pregnancy Complications, Cardiovascular/ or exp Ocular Hypertension/ (908496) 52 (pregnancy‐induced or ocular hypertens$ or preeclampsia or pre‐eclampsia).ti. (14675) 53 49 not (50 or 51 or 52) (963798) 54 (7 or 13 or 18 or 22 or 28 or 32 or 37) and 41 and 53 (16902) 55 54 and (2016$ or 2017$).ed. (350) 56 remove duplicates from 55 (262)

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

Database: Cochrane Hypertension Register Segment via Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS‐Web) Search Date: 23 January 2017 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ #1 hypertension AND antihypertensive* AND (Meta‐analysis OR Review):MISC2 AND INSEGMENT (481)

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐